#gregg toland

Text

SUBLIME CINEMA #673 - THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES

Criminally difficult to find a good transfer of this film - Criterion has ignored It, and it's unusual for a movie that once took home eight Oscars to have been so forgotten. But this is a profound, understated masterpiece, with some incredible cinematography by Citizen Kane's Gregg Toland.

#cinema#film#films#cinematography#movies#movie#filmmaker#william wyler#the best years of our lives#Gregg toland#harold russell#cinephile#40's#academy awards#black and white#black and white cinematography#great film#classic film#american films#war film#ww2#world war 2#veteran

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

scenery + details appreciation

CITIZEN KANE (1941) | dir. Orson Welles

cinematography by Gregg Toland

#citizen kane#citizenkaneedit#orson welles#gregg toland#filmedit#filmgifs#cinematography#cinematographyedit#black and white film#scenery#sceneryedit#classicfilmedit#classicfilmblr#classicfilmsource#classicfilmcentral#films#filmtv#tvandfilm#fyeahmovies#moviesource#my gifs#my stuff#flashing gif#flashing cw

867 notes

·

View notes

Text

On set of WE LIVE AGAIN (1934) are Fredric March, Anna Sten, director Rouben Mamoulian and cinematographer Gregg Toland.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

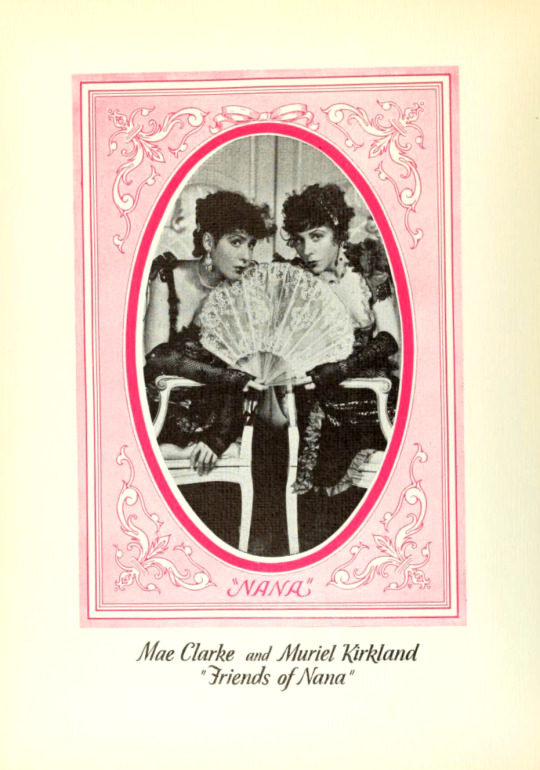

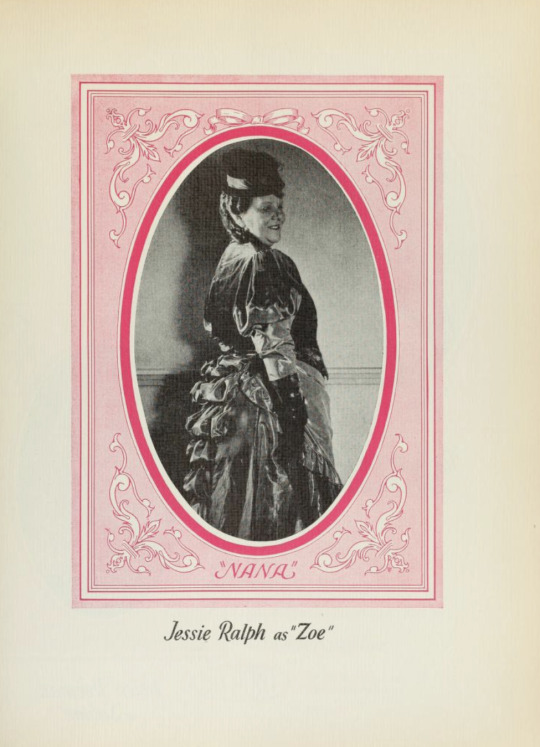

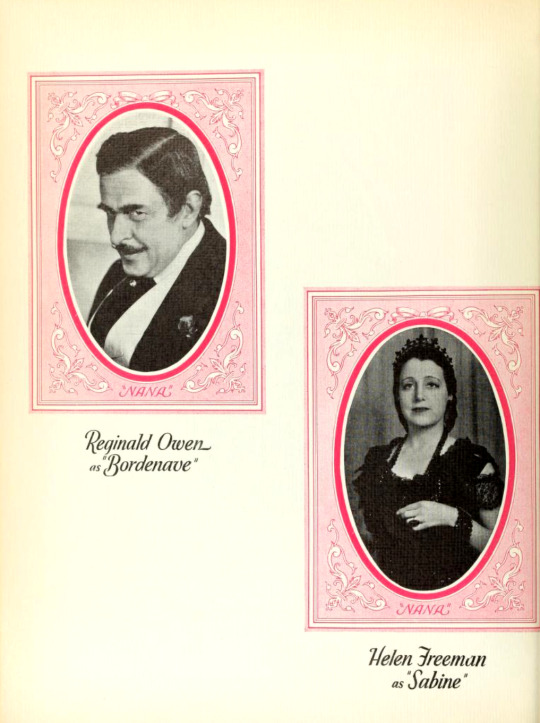

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, January 30, 1934

#movie ad#vintage advertising#vintage advertisement#1930s#1934#anna sten#lionel atwill#mae clarke#Reginald owen#Gregg Toland#nana#samuel goldwyn

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

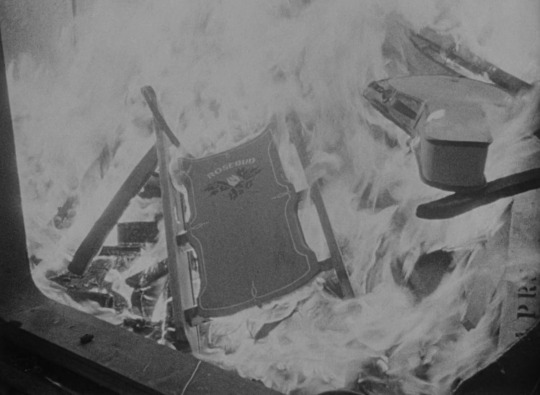

Citizen Kane (1941)

#film#movie#citizen kane#quarto potere#orson welles#herman mankiewicz#gregg toland#Joseph Cotten#Dorothy Comingore#memory#memoria#human race#razza umana#curses

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

the grapes of wrath (john ford, 1940)

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Citizen Kane (1941, dir. Orson Welles)

#Citizen Kane#Orson Welles#director#filmmaker#actor#master#Herman J. Mankiewicz#John Houseman#Robert Wise#Gregg Toland#Joseph Cotten#Everett Sloane#drama#scene#masterpiece#perfect#movie#40s#1941#cinema

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Long Voyage Home (John Ford, 1940).

#john wayne#john ford#the long voyage home#gregg toland#sherman todd#james basevi#julia heron#the long voyage home (1940)

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Lantern#Media History Digital Library#Orson Wells#Citizen Kane#1941#Noir#Cinematography#Gregg Toland

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teresa Wright and Richard Carlson in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes, 1941.

#teresa wright#happy birthday!#richard carlson#the little foxes#1941#william wyler#lillian hellman#gregg toland#bette davis

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

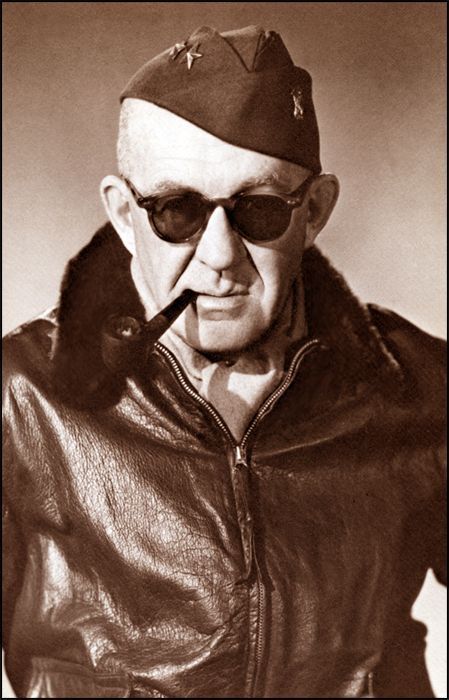

Gregg Toland, May 29, 1904 – September 28, 1948.

At Goldwyn Studios in 1948, Toland explains the workings of a Mitchell camera to a high school student.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

December 7th (1943) was directed by Gregg Toland and John Ford. Gregg directed the original 82 minute version including scenes with Walter Huston as Uncle Sam. This was master cinematographer Toland's only director credit. Ford re-edited it down to 32 minutes, winning an Oscar as Best Documentary Short.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

opening sequence scenery + details appreciation

CITIZEN KANE (1941) | dir. Orson Welles

cinematography by Gregg Toland

#citizen kane#filmedit#filmgifs#classicfilmedit#classicfilmblr#classicfilmsource#classic films#tvandfilm#dailytvandfilm#filmandtv#moviesource#cinematographyedit#cinematography#sceneryedit#scenery#citizenkaneedit#orson welles#gregg toland#my stuff#my gifs#scheduled post

578 notes

·

View notes

Text

Influential cinematographer Gregg Toland (May 29, 1904 – September 28, 1948)

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Scapular (1968, Mexico)

Also known by its original title, El escapulario, Servando González’s The Scapular is one of the finest examples of classic Mexican horror filmmaking. For those versed in modern horror, adjust your expectations. Atmospheric from its opening moments and making full use of its sparse environments, this movie does not depend on bloody set pieces or instant frights. Instead, The Scapular prefers gradual storytelling through flashbacks, all while it refuses to answer how any of its unlikely events might be possible. The screenplay by González, Jorge Durán Chávez, and Rafael García Travesi navigates questions of Catholic faith, political preferences during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), and love amid more grotesque moments one comes to expect in a horror film. Those horror elements – of spirits staying true to their word – are most prominent at the very beginning and second half of the film, and absent for almost all the first half. A major contribution from cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa – regarded by some to be the greatest Mexican cinematographer of all time – and his Hollywood-influenced lighting elevates the movie, bathing the screen in intoxicating black-and-white.

Something during or after the Mexican Revolution, Father Andrés (Enrique Aguilar) pulls into town on a late train, following an unseen individual to the residence of Doña María (Ofelia Guilmáin). While the padre and the unseen person – the camera nods “yes” in response to a few questions from the padre – amble through town, two bandits follow close behind. They have been stalking Father Andrés since he disembarked the train, hoping to pilfer his gold watch. They decide to wait until after he administers his sacraments to Doña María. Inside, Doña María – whom the padre knows almost nothing about – hands the padre a scapular (a primarily Catholic garment of piety), which she claims to have saved the lives of her two eldest sons. El escapulario, for most of its remaining runtime, flashes back to the stories of those two sons, Julián (Carlos Cardán) and Pedro (Enrique Lizalde).

Once a soldier for the Mexican government, Julián defects and joins the rebels in their fight against Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship. For Pedro, he is working for his uncle at a saddle shop, but has his eyes on the village chief’s niece, Rosario (Alicia Bonet) – in his attraction, class tensions come to a head.

Servando González, Jorge Durán Chávez, and Rafael García Travesi’s screenplay does the best it can with an unwieldy story structure. Though El escapulario is a breezy eighty-five minutes, the flashbacks for Julián and Pedro both feel slightly too long while the audience is itching for a macabre payoff. Nevertheless, the screenplay juggles numerous themes without ever feeling forced. Discussion about the Mexican Revolution is mostly confined to Julián’s story. At times, the dialectic between Mexico’s then-contemporary military dictatorship and peasant-led revolution sounds too much like propaganda. But given that Doña María is responsible for imparting this story to the padre (and, by extension, the audience), one can expect some over-romanticizing the revolutionary cause. El escapulario firmly sympathizes with the revolutionaries – following how popular historical memory is in Mexico today. In Julián’s story, this ideological conflict takes place entirely within a military and revolutionary backdrop. Civilian perspectives are not present for this part, but there are mentions of a groundswell of support for the revolutionaries. Acknowledging these partisan emotions and political interpretations, viewers who have not seen the entirety of The Scapular should accept the bare facts of Doña María’s recounting of Julián and Pedro’s stories as truthful – even though she was not present for any of the moments she describes. To say more risks spoiling the entire film.

Pedro’s chapter of El escapulario is less explicitly political than his elder brother’s, but related tensions persist. Pedro, firmly in the working class but not poor, inspires the wrath of Don Augustín (Jorge Russek, who played Major Zamorra in 1969’s The Wild Bunch) by even looking longingly at his niece, Rosario. Don Augustín is no moustache-twirling villain, but his disregard for his fellow villagers and overinflated opinion of himself make clear his sympathies for the Porfiristas against the revolutionaries and peasantry. Director Servando González keeps the focus on the brothers in both flashbacks, rooting the film through the perceptions of those with little to benefit under the Porfirio Díaz regime. It is in Pedro’s story that the first bits of horror filmmaking appear since the film’s opening minutes. Occult, perhaps darkly religious, forces influence developments as Pedro disregards Don Augustín’s advice to avert his wandering glance from his niece. These moments hinge on the scapular, as Don Augustín enlists others to intimidate – by force, if necessary – Pedro and Rosario from even thinking about each other.

In those moments, cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa’s work truly shines. Figueroa, who, in 1935, lived in the United States for a year to formally study his craft under Gregg Toland (1940’s The Grapes of Wrath, 1941’s Citizen Kane), certainly learned much from the man he considered his teacher. Even after returning home to Mexico in 1936, Figueroa continued to analyze Toland’s work closely – from chiaroscuro techniques to deep focus cinematography. But even before leaving for America, Figueroa’s work as a still photographer exemplified someone with a keen eye for composition. And long after his time under Toland, Figueroa would shadow some of Hollywood’s best cinematographers on his trips to Southern California; Toland himself, when visiting Mexico, would make suggestions and critique his old student’s work. Figueroa also enjoyed the privilege of friendships with Mexican artists Diego Rivera (who counseled him on how to use color – a story for another time, as El escapulario is a black-and-white film) and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Siqueiros provided Figueroa advice on escorzo or, in English, foreshortening. Foreshortening is an artistic technique on perspective that allows an artist to portray something that appears to be closer or shallower than it is.

Foreshortening becomes crucial in El escapulario’s second half, as the narrative descends in into the grisly and ghostly. A nocturnal horse ride during Pedro’s chapter stumbles upon a horrific sight, aided by foreshortening, sharp but still-horizontal angles, and quick cuts as the horse begins to buck wildly – spooked by unnatural forces that animals in movies just seem to pick up on faster than any human. The lighting’s influence on this scene’s mood is impossible to replicate if this was a color film. El escapulario’s final two scenes – by chicanery, candlelight, and cobwebs – are the culmination of what Gabriel Figueroa picked up from the likes of Toland and Siqueiros. Even when traversing an empty street at the witching hour or in a desolate room, there always seems to be a presence watching and waiting. Early morning mist appears to curl around the characters, like wispy hands. I am uncertain how this effect was achieved, and it might be seen as campy in most other contexts. Here, it is as if unknown forces are toying with the characters’ souls. It is spectacular camerawork from Figueroa, in his only collaboration with Servando González in a career spanning more than two hundred movies.

Viewers could also approach The Scapular from a religious context. The lines between life and death, faith and the absence of it, are tenuous. Catholicism and Catholic metaphysics are present from the prologue, impacting the dialogue and behaviors of all of the characters from their moments of introduction. Those more familiar with Catholicism in Mexico – the 2020 Mexican census says 77.7% of Mexicans practiced Roman Catholicism – can hopefully make more educated and nuanced contributions to religiously-inflected analyses of The Scapular than I possibly could.

The Golden Age of Mexican cinema, in some ways mirroring, but distinct from, a similar Golden Age for the nation’s northern neighbors, had been concluded for a decade when Servando González’s El escapulario premiered in theaters in 1968. Though some Mexican horror movies flourished before the end of that Golden Age, the films that fueled – and continue to inspire – Mexican horror cinema followed the footsteps of Fernando Méndez’s El vampiro (The Vampire; 1957), a late Golden Age film that broke through in a filmmaking and moviegoing environment heavy on melodramas and Westerns. The writing of this chapter of Mexican film history continues, still hampered by the 1982 Cineteca Nacional fire that destroyed several thousand Mexican films, screenplays, and books and an anecdotal domestic disinterest in Mexico’s cinematic heritage.

With thanks to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles and guest programmer Abraham Castillo Flores (also Head Programmer at Morbido Fest, based in Mexico City), the reclamation of that history is underway. Yours truly was able to see a restored print of El escapulario with complete English subtitles, although some audio hitches – especially in regards to the film’s score – remain. The technical mastery is apparent across El escapulario, and Servando González’s directorial vision and Gabriel Figueroa’s visual flourishes are worth the watch even for those unaccustomed to non-contemporary horror filmmaking. El escapulario is a visual treat, a chilling entry into the canon of classic Mexican horror.

My rating: 7.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#El escapulario#The Scapular#Servando González#Enrique Lizalde#Enrique Aguilar#Carlos Cardán#Federico Falcón#Alicia Bonet#Ofelia Guilmáin#Eleazar García#Jorge Durán Chávez#Rafael García Travesi#Gabriel Figueroa#Gregg Toland#My Movie Odyssey

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Citizen Kane (1941)

#film#movie#citizen kane#quarto potere#orson welles#herman mankiewicz#gregg toland#Joseph Cotten#Dorothy Comingore

57 notes

·

View notes