#guerilla historian

Video

DPS from the sky. by stevenbley

#abandoned#decay#urbex#urban exploration#barbed wire#torn pants#pennsylvania#philadelphia#power station#electric#low tide#high tide#fences#coal chute#rust#sunrise#guerilla historian#asbestos#industrial#dead body#police#dji#mavic pro#flickr

0 notes

Text

Episode 49th – After the Russian Civil War: The Last Days of the Basmachi

Recovering from Enver Pasha: the 1923-1926 Campaign

When we last left the Basmachi, Enver Pasha was being Enver Pasha and led his followers into a disastrous series of frontal assaults that shattered their forces. He was then hunted down and killed by Red Army forces. Three Basmachi commanders survived Enver Pasha: Salim Pasha, Enver’s successor, Junaid Khan in the Kara-Kum Desert in Turkmenistan, and Ibrahim Bek in Tajikistan.

Salim Pasha and Ibrahim continued fighting for the Bukharan Emir, who was now in Afghanistan, and many Basmachi fighters survived by retreating into the mountainous rural terrain, like Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, or ride to and fro from Afghanistan. Salim Pasha, in 1922, rode to Afghanistan and received the Emir’s blessing for a large scale attack against Eastern Bukhara. He united several smaller Basmachi units into an army of 5,000 and targeted not only Soviet garrisons but Revkom members and local party workers. However, like Enver Pasha, Salim Pasha thought in a scale larger than his forces could manage and was surprised by the Soviet’s improved tactics and abilities.

Enver Pasha

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a man standing at an angle, looking into the camera. he has a thick mustache that is twisted upwards. He is wearing a dark fex and a dark military tunic with gold epaulettes. His arms are folded across his chest]

His unified force survived from December 1922 to March 1923, when the Soviets shattered his units. He fled to Afghanistan and was later killed far from Central Asia by Kemalist secret police. While Haji Sami and Ibrahim Bek recovered from Enver Pasha’s death, Junaid Khan in Turkmenistan took the city of Khiva.

In October 1923, the Khorezm Soviet Republic made a huge mistake and declared the separation of church and state. They deprived the clergies of their responsibilities, and called for the nationalization of waqf land. The Khivans merchants and cleric begged Junaid Khan to rescue them and defend Islam. He and his Basmachi took control of the city of Khiva for a month. The Soviet’s sent a garrison to retake the city and drove his forces back into the Kara-Kum desert where Junaid Khan would remain until he fled to Iran in 1927.

Soviet Military Response

The Soviets took advantage of their victory by launching their own campaign in March. This campaign was led by Red Army commander and a hero of the Russian Civil War, Pavel Andreevich Pavlov. Pavlov had three objectives which proved devastating to the Basmachi:

Focus all attacks on the Basmachi base of operations instead of chasing them around the region. These three bases were: the mountainous stronghold of Matcha, the Lokai and Gissar Valleys in the south, and mountainous Garm in the east. These three areas would be attacked simultaneously so the Basmachi couldn’t flee into each other’s territories either for safety or to assist each other.

Increase his forces until they are strong enough to meet the task. Moscow granted his request for more support and by 1923 he had 5,832 men with 222 machine-guns and artillery pieces in Eastern Bukhara.

Severe the cord tying the cavalry to the infantry. Normally cavalry was used to protect the infantry and ride forward just enough to find the Basmachi or lead them into an ambush. Pavlov freed the cavalry so they could operate again as an independent force, allowing them greater independence and freedom of movement.

Pavlov’s methods proved successful in March 1923 when they took Matcha, a previously impossible objective for the Soviets. He succeeded because he ensured that all supplies were available when needed. His machine guns and artillery were assigned to pack trains and supplies were stockpiled on the Samarkand-Pendzhikent line in advance, far away enough to be protected, by close enough for supplies to be sent where they were needed. He also utilized local volunteers to serve as scouts, interpreters, and engineer labor.

Garm fell shortly afterwards on July 29th after a twelve-hour battle. Fuzail Maksum, the Basmachi in charge of the forces around Garm, fled to Afghanistan with a slight wound on August 12th.

The Gissar-Lokai valley continued to prove difficult to subdue, but as long as Salim Pasha remained in the region, the Soviets were able to exploit the rivalry between him and Ibrahim Bek, to the detriment of both of their forces.

The Soviet Political, Economic, and Social Response

By 1923, the Soviets realized they couldn’t break the Basmachi with military might alone. They needed to respond on the political, economic, and social front as well. To that end, the Soviets flooded the rural areas with Cheka or OGPU agents to flush out collaborators and convert supporters of the Basmachi to their cause. These conversions or alliances were heavily publicized affairs and often took place in open air demonstrations where Soviets and local actors alike gave big speeches in front of a large gathering, publicly professing their new alliance and friendship with one another. These speeches can’t be taken at face value and even one Soviet claimed:

“Of course, one could not trust the sincerity of the bais who welcomed the Soviet power and land reform. Still, their speeches showed that bais realized their powerlessness.” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 21

One particularly painful conversion was of Ibrahim Bek’s own people the Lokai in December 1923. To add more salt to the wound, the Soviets also recruited a 60-man cavalry detachment of Lokai people to hunt Ibrahim.

The assimilation of local leaders also extended to the Basmachi leaders themselves. A perfect example of this behavior is Ishniiaz Iunusov. Iunusov fought against the Red Army as a Basmachi leader but was later hired as the head of Soviet Muslim voluntary detachment to fight against the Basmachi. During the Basmachi campaigns he won two Red Banner medals and eventually became a member of the Communist party. He was then named head of the Administration Department and commander of the Voluntary Detachment. A Soviet report about his abilities read:

“His authority was based on his Soviet position and his Soviet distinctions. As the head of the Administration Department and Voluntary Detachment, he thought of himself as the absolute master. He formed his detachment as he wished, from his close people and from 30 members of his detachment; six of them were bais and kulaks… “Not a single arrest of a disenfranchised or bai in the region evaded him. In all cases he took the arrested out on bail and tried to help him. He even participated in illegal searches, arrests, and extrajudicial shootings” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 31-33

Economically, the Soviets implemented the food for cotton plan, which forbade farmers from planting anything but cotton in exchange for food. This meant that the Basmachi could no longer raid fields and had to extort food from their own supporters. Tajikistan was already experiencing mass starvation and hoarding food was seen as anti-Soviet behavior. Soviets, fearful that if food was being reserved it was for the Basmachi, often confiscated desperately needed food, leaving the locals at the mercy of their neighbors and whatever social programs the Tajik government was able to implement. While people feared the Basmachi, they also blamed the Soviets for the lack of food. One Tajik citizen complained:

“The government knows that Ura-Tiube region is full of Basmachi and that we suffer [first] from their treatment of us; second, we suffer from high prices; third, from expense for the Red Army soldiers who are defending us from Basmachi…People run away to the mountains when they see the Red Army soldiers. If grain costs five rubles on the market, the Red Army pays only 1 ruble 40 kopeks. There are many deficiencies here; if some commissions would come and investigate things thoroughly, they would find a lot of material “- Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 35

The lack of food not only put a strain on the Basmachi’s relationship with the locals, but also put pressure on Basmachi commanders to prevent their soldiers from deserting because of starvation and dwindling prospects of success. The Soviets took advance of this tension by issuing promises of amnesty.

On March 15th, 1925, the Tajikistan government promised to free all sentenced people who were imprisoned for under two years or had already completed at least half of their sentence. They also promised to shorten current incarceration periods by 1/3. They offer full amnesty and immunity to existing fighters if they surrendered between March 15th and June 15th, 1925. They proclaimed:

“On this great day for Tajikistan…the Revolutionary Committee aims to return to peaceful work those workers and peasants who committed crimes due to their darkness and ignorance, under the influence of emir and tsarist officials. We wish to give them a chance to redeem their guilt before the rule of workers and peasants." - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 23

Of course, the Basmachi had to surrender their arms, rat out their collaborators, and publicly denounce their crimes. While the Soviets believed that if the state pardoned you, you wouldn’t forget it and would feel beholden to the state, there were more practical reasons to grant mass amnesty. The Soviet state wasn’t strong enough in Tajikistan to hold everyone in prisons. Some prisons were already holding 300% percent over their mass capacity. They didn’t have enough guards or food to feed the prison population.

Despite their promises the first few years of Tajikistan’s existence were filled with more executions of Basmachis than amnesties. Again, this is because of limited state capacity in Tajikistan. The high court didn’t exist outside of a couple of tables, which traveled with the judge, revolutionary committee members, and political police under red army guard.

Because they didn’t have the resources, manpower, or institutional support, many judges realized that the best way to handle the Basmachi was with quick show trials and executions. It also worked as a semi-military strategy in the Soviet’s battle over the territory. One judge wrote:

“Basmachi resistance demanded quick show trials and strict justice…delay of an execution, not to mention the revision of capital punishment, would undermine all our efforts in the fight against the Basmachi…During this month we heard 70 cases, 45 of whose defendants were sentenced to death.” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 25

Not all Basmachi were lucky enough to have a show trial. Many were killed in gunfights or extrajudicial killings. Between 1925 and 1926 the OGPU shot 208 Basmachi supporters. From March 1925 to September 1925, the Red Army killed 48 Basmachi leaders and 1,423 Basmachi soldiers.

However, the Soviet’s ability to kill its enemies depended on cooperation from local leaders and this wasn’t always forth coming. Many officials prevented trials or executions by not supplying translators, juries, or public defenders. However, this came at great risk to the people who delayed the trials. Many were executed as well.

The violence alienated people and the amnesties lost their appeal when it became clear that those who surrendered were left hungry, homeless, and destitute. Add clan disputes and personal rivalries and there were many reasons for Basmachi to switch sides. Abdukarim explained why he collaborated with the Soviets and then abandoned them as follows:

“At the beginning I was a Basmachi, and from your side many good words were said, so we surrendered and gave up our guns and sat calmly in our houses. But all your talk turned out to be a lie since we did not know what your rule was about, [your rule] actually made us Basmachi. The reason is that among us there are many bad people and each of us has many enemies, and so these bastards give you information that one or another person has weapons. You arrest these people only on the basis of their words without asking people themselves. This is the only reason we became Basmachi again” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 34

He complained to a Soviet commander that:

“Mirza Abul Khan worked for your rule so hard, but he did not receive any salary for eleven months. But today, Imam Ali Mukhat, the messenger who is unrighteous – does not accept Shariat—informed us that he has two three-line rifles, two sabers, one Berdan rifle, and one revolver.” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 35

He wrote:

“If [Soviet rule was just] in reality, it would not intervene in every person’s business for the past two or three years; I mean Basmachi resistance would have ceased to exist in the past two or three years…We have nothing but Allah and the Prophet. We have no guns, no finances, no soldiers to wage war, but because of fear for our lives, we run around without having any relation to your workers nor to your business… I swear by Allah and his Prophet that your rule made us Basmachi” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 37

If the Soviets thought it was impossible to find loyal cadre in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, Tajikistan made them want to tear their hair out. Il’iutko, a Soviet representative in Tajikistan, wrote:

“The Shurabad Revolutionary Committee was formed from the following people: the chair – Abdul Rashid, a bai from the tribe Isan Hoja; his deputy was Abdul Kaim, a bai from the Badra Ogly tribe; kazis [judges] from Isan Hoja; one representative from the Badra Ogly tribe; and a representative from the Red Army. Abdul Rashid bai was appointed as chair with the following reasoning; the leading organs of East Bukhara thought this appointment would appeal to Abdul Rashid’s self-esteem, as he had fought against Ibrahim Bek for a long time and would encourage him to fight against Basmachi with full energy and responsibility. But our hopes were not borne out; he supported the Basmachi” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 29

The Soviets ran into issues trying to punish the leaders they were collaborating with. Many times, Tajik citizens would try to defend their local leaders one Soviet commander wrote:

“If a leader was arrested, people went to great lengths to get him out of jail, certifying their work against the Basmachi” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 31

Yet not all local leaders supported the Basmachi. Many found a way to fit within the Soviet order. Maksum Abdullaev, a Soviet Muslim, wrote:

“When in 1924 Ibragim Bek wrote me that if I joined him he would make me bek of Kuliab, I answered that Soviet rule had already made me a bek. Soviet rule is strong, but you are an outlaw” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 41

Ibrahim Bek’s Counter-Offensive

By September 1923, Ibrahim Bek was the last Basmachi commander standing in Eastern Bukhara, and he retained enough strength to launch a counter-attack. Ibrahim Bek attacked a garrison at Naryn at the moment of Soviet recruitment turnover – assuming this meant that the number of inexperience soldiers would be high. However, the recruits held until reinforcements could arrive and they drove Ibrahim Bek back, Soviets claiming they killed 117 Basmachi commanders and 1565 soldiers.

Ibrahim Bek

[Image Description: A dark skinned man with a scraggy beard. He is wearing a grey turban and a black and white long shirt. A black robe with embroidered flowers rests on his shoulders.]

The Soviets sent forces to occupy the land of Urta-Tugai on the Soviet-Afghan border making it harder for the Basmachi to slip to and fro. Pavlov worked hard to rip the roots of support out from underneath the Basmachi, effectively hurting their supplies and support.

In 1926, the Soviets achieved what they thought was the final victory against the Basmachi. In March 1926, Red Army commander Semen Mikhailovich Budenny led an all-out assault against Ibrahim’s remaining forces. Relying on Frunze’s tactics of flying columns and implementation of garrisons in key locations to cut Basmachi forces off from their supports, Budenny planned to beat Ibrahim Bek into submission. Because of Budenny’s tactics, Ibrahim Bek’s forces faced the choice of starving to death in the mountains while being hunted down by the Soviet flying columns or die making a last stand against the Red Army within the Gissar and Lokai valleys. An interesting development was the introduction of heliograph stations and a permanent mobile field staff in the region. Radio wasn’t available in 1926, but by using strategically placed heliograph stations, Soviet forces to warn units of approaching Basmachi, robbing the guerrilla soldiers of the element of surprise.

Ibrahim Bek held on until the Soviets took 1,500 sheep belonging to Ibrahim. Without this desperately needed food source, Ibrahim was forced to flee into Afghanistan, ending the Basmachi threaten in Eastern Bukhara.

Political Turmoil in Afghanistan and Tajikistan

One of the reasons the Soviets were able to defeat the Basmachi was the ability to win over the support of the local peoples via increased access to food and land, alleviating any fears that Communism would sweep away long held traditions and Islam, and forcing the Basmachi to hurt their own supporters while looking for supplies. However, by 1927, the Soviets had shot themselves in the foot by implementing increasingly unpopular measures such as the hujum, the unveiling and liberation of women, the ending of the Islamic courts, the further reduction of waqf lands, and the increased secularization of education (much of which was facilitated by the creation of nation-states, which we discussed last episode). Worse, maybe, was the forced collectivization and the forced settlement of the nomadic populations. The campaign started in 1929 and inspired a new wave of anti-religious fervor amongst the Soviets. When the Soviets weren’t forcing nomadic people to settle, they were closing mosques and madrasas and arresting clerics. Collectivization nationalized all land and forcefully resettled nomadic and semi-nomadic and rural populations as the Soviets saw fit. It would have tragic consequences in Kazakhstan and in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan it provided the spark for one last hurrah for the Basmachi.

After pushing the Basmachi into Afghanistan, the Soviets had a hard time keeping them in Afghanistan. In 1927, one OGPU officer wrote:

“The border is not secured; we have no guns or people to guard it; the militia is drunken and amoral. It is impossible to guard the border; it is impossible to stop Basmachi groups [and] to prevent damage to agricultural campaigns” - Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 55

It is easy to overstate the threat Bukharan Emir Muhammad Alim Khan presented to the Soviet Union. He had been staying in Afghanistan since his ouster in 1921 and so much had happened in the region since he fled. Even if people wanted him to return at one point, that desire had disappeared a while ago except for the most diehard of emirists. Still, he was able to provide some support to Ibrahim Bek and the Basmachi who fled to Afghanistan. Ibrahim used the time in Afghanistan to extort money from the Bukharan refugees who had settled in Afghanistan and to restructure his command. He centralized his command granting him a better understanding of what his supplies looked like and how many men he actually had. He also improved communications between his men in the field and himself and himself and the emir.

Despite signing a treaty of neutrality and non-aggression in 1921, the Afghan government had always tolerated the Basmachi. This became a problem in 1924 when northern Afghanistan underwent a power struggle. Ibrahim took advantage and made camp in Urta-Tugai island. The Soviets were so freaked out, they invaded Afghan territory in 1925. Now Urta-Tugai had an Afghan garrison that had mostly turned a blind eye to the Basmachi. When the Soviets invaded, they actually disarmed and occupied the Afghan garrison.

This scared the Afghan government, prompting them to sign another treaty of neutrality and non-aggression. A year later a popular uprising would make the treaty void and end any attempts to push the Basmachi out of northern Afghanistan.

The Basmachi would take advantage of the political turmoil in Afghanistan and in spring 1929, the Bukharan Emir called together the remaining Basmachi to him. He issued a decree placing leadership of the remaining forces under Ibrahim Bek’s command with the intention of invading Tajikistan and reclaiming it from the Soviets.

The Resurrection: the 1929 Campaign

In spring 1929, the Basmachi tested the units stationed on the Soviet-Afghan border and in April, Fuzail Maksum of Garm slipped across the border with fifteen men to connect with supporters in Eastern Tajikistan. His purpose was to raise local support and recruit and prepare for the arrival of Ibrahim Bek with the main Basmachi force. Maksum raised two hundred men and led several attacks against Garm, achieving several minor victories.

The overall Soviet Commander in Central Asia, General P. E. Dybenko, issued several emergency measures to address the growing threat. He ordered the raising of local self-defense units in Eastern Tajikistan and increased the local political work. He even tried to manipulate the local antagonisms within the population to defeat the movement, believing that the many cattle-breeders of the region would hate the Basmachi for their requisitioning efforts. Despite these efforts to engage with the local actors, the main Soviet strategy was still military in nature. The Russians countered Basmachi hit-and-run tactics by establishing militarized zones and used artillery and air raids to destroy villages suspected of collaborating with the Basmachi. The Cheka arrested and deported 270,000 Turkestanis suspected of collaborating with the Basmachi. During the Red Army’s occupation, they burnt Dushanbe, Andijan, and Namangan to the ground and damaged several other villages. In total 1200 villages were burnt to the ground.

Fuzail Maksum’s force of now 800 men led an attack against the city of Garm and then the neighboring airfield. The Soviets defended the airfield with 16 men waiting for reinforcements that would arrive by air and a seventy-five men cavalry regiment. Five airplanes arrived at 6:00 am on April 23rd, 1929, unloading 40 men, carrying machine-guns and ammunition. Fuzail Maksum’s forces fled, abandoning Garm. On May 3rd, badly wounded Maksum returned to Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s Problem

The Soviet’s retaliated against the Garm region hard and fast. They set up special OGPU campaigns to ferret out the people who supported Maksum, holding special tribunals and several people were executed. Despite these setbacks, Ibrahim Bek’s forces were able to cross the Afghan-Soviet border with ease.

The Soviets grew so concerned over these incursions that they seriously considered an invasion of Afghanistan to place a puppet government on the throne. They even sent a force of 800-1200 Red Army soldiers dressed as Afghans in support of one of the Afghans vying for leadership, but had to retreat when they were stopped by the Afghan army and their candidate abdicated. The situation in Afghanistan stabilized and the new government under Nadir Khan left the Basmachi alone. However, the Soviets gave up on diplomacy and started to chase the Basmachi across Afghanistan’s border, sometimes crossing 40 miles into the country before withdrawing. Nadir Khan was forced to act, and he dispatched Sardar Shah Mahmud the Afghan army’s commander-in-chief to deal with the Basmachi problem. He also started negotiations with the Soviets to renew the 1926 treaty of neutrality and non-aggression.

General Mahmud demanded the Basmachi disband, and Ibrahim Bek replied by saying he was going to unite with the Uzbeks and Tajiks in northern Afghanistan and create a nationalistic Uzbek-Tajik government independent of Afghan Control. In December 1930, Mahmud entered the northern territory. Through the spring of 1931, he led a large-scale campaign against Ibrahim Bek and reclaimed several major cities but could never capture Ibrahim Bek himself. Instead, on March 1931, they offered Ibrahim Bek to incorporate his forces into the Afghan army. He refused and in April 1931, he led 800 men into Tajikistan for a final invasion. In total, he had a command of 2000 men.

He swept into Tajikistan armed with reliable intelligence and the momentum of a sudden invasion. He executed pro-Soviet officials and locals, blew up several warehouses, state farms, and railway lines. The people of Tajikistan initially supported his uprising but grew disenchanted with his discounted political and ideological ideas. Trying to rally people around an Emir that had been deposed for about a decade and the return of feudalism held little appeal to most people. Too much had changed to go back to the old ways and Ibrahim Bek had been too disconnected from his people to fully understand what they wanted.

Anyone who tried to join him from Afghanistan ran into Soviet patrols and suffered severe losses. The Soviets created a special unit of OGPU, local volunteers, and Komsomol members to hunt Ibrahim Bek down. In May, the Red Army offered amnesty to any Basmachi members who surrendered causing 12 leaders and 653 men to abandon the Basmachi ranks. Ibrahim Bek was left with only fifteen men in the foothills of Baba-Tag avoiding assassination attempts and betrayals. On June 23, 1931, while attempting to cross the Kafirnigan river, he was betrayed by locals, and captured by Soviet forces. He was sent to Tashkent and executed, officially ending the Basmachi guerilla movement.

References

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Despite Cultures: Early Soviet Rule in Tajikistan by Botakoz Kassymbekova

“Frunze and the development of Soviet counter-insurgency in Central Asia” by Alexander Marshall in Central Asia: Aspects of Transition by Tom Everett-Heath

“The Final Phase of Liquidation of the Anti-Soviet Resistance in Tadzhikistan: Ibrahim Bek and the Basmachi, 1924-1931” by William S. Ritter

“The Basmachi or Freeman’s Revolt in Turkestan 1918-1924” by Martha B. Olcott

Russian-Soviet Unconventional Wars in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Afghanistan by Robert F. Baumann

#queer historian#history blog#central asia#queer podcaster#central asian history#spotify#basmachi#ibrahim bek#guerilla warfare#afghanistan#soviet union#russian colonialism#soviet empire#Spotify

0 notes

Text

From the Firmament

I never, ever expected to write anything longer than 2000 words in this fandom or any other. Now this is apparently happening.

It's an Arranged Marriage AU set in a world reminiscent of the Ancient Roman Republic and its frontiers, with steppe nomad/guerilla war hero Ed, amateur polymath/accidental statesman Stede, and asides from future historians speculating on their relationship as a watershed moment in history.

#oh my god this is happening#I finally reached that point where I couldn't look at it anymore#which is the time to hit publish in my experience#I can't believe it's finally real#let's goooooo#ofmd#our flag means death#ofmd fanfic#fic writing#writing process#ofmd au#arranged marriage au#edward teach#stede bonnet#gentlebeard#blackbonnet#baby's second longfic#chapter 1

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

As "John Ferrier Talks with the Prophet" in Letters from Watson, I'm sucked down the rabbit hole of Mormon Escapee Narratives.

There were several that were wildly popular in the years between the LDS settlement of Utah and the time when Doyle was writing. The one I can find an online copy of is Fanny Stenhouse's memoir, which appears to have had a couple versions under variant titles. The one I've paged through is Tell It All: The Story of a Life's Experience in Mormonism (1879, with foreword by Harriet Beecher Stowe). There's also an 1872 version titled Exposé of Polygamy in Utah: A Lady’s Life among the Mormons.

Fanny Stenhouse's existence is documented, and she went on the lecture circuit in the 1870s as an opponent to polygamy.

Her story matches Doyle's description of conspiracy theories, secret organizations, and atrocities in Salt Lake City so closely that it's likely he got his ideas from Stenhouse or similar materials. Newspaper coverage of happenings in remote Utah would, whether in London or Edinburgh, have been scanty and sensationalist -- although there is one historic event that might have excited interest, and its absence from the story muddles the timeline.

In spring 1857, President Buchanan sent the U.S. Army to the Utah Territory. The LDS residents feared renewed persecution, turned plowshares into swords, and fought a guerilla war of annoyance against the army. In September 1857, a group of Mormon militia slaughtered an entire wagon train of settlers bound for California (the Mountain Meadows Massacre). The wikipedia entry linked is worth a read, as it captures the "what really happened? who lied about what? was this an LDS policy or a group that acted recklessly on its own?" questions that swirl around efforts to make sense of the history of this era.

The "Utah War" wasn't the first incident of violence between LDS and "gentiles." Back in 1838 in Missouri, harassment and violence toward LDS settlers was met with the formation of the Danites (aha! Doyle mentions them!), a vigilante secret society that retaliated violently. The 1838 Mormon War is an appalling read on so many levels.

Whether the Danites were still operating in the 1850s in Utah is a question that historians today dispute. Their reputation in the 1830s was that they were determined to remove dissent within their own people, so the idea that forces within the LDS community would silence a man for disagreeing has some historical basis.

What's seriously missing in Doyle's account is that in 1858, Brigham Young's plan for thwarting U.S. troops was to evacuate Salt Lake City -- so thousands of LDS faithful boarded up their homes, gathered their goods, and marched off into the mountains. (There was talk of burning the city, but that apparently didn't happen.) Obviously, people came back, but that's a big thing for John Ferrier to have lived through without remarking upon. A year of widespread want from culling herds and missing portions of the planting season, combined with military occupation, seems like a big deal.

If we assume none of that had happened yet, then it's early 1857 and only 10 years since Ferrier and Lucy were rescued -- making his twelfth year of wealth in the future, the discovery of silver in Nevada also in the future, and Lucy just fifteen. The latter is still plausible for her being pressured to marry, alas. I think the timeline's just a bit muddled, though -- even with today's online resources, researching 30-year-old events in a far-away place can get messy.

Ferrier's unwelcome visitor is none other than Brigham Young, charismatic leader of the LDS community, and governor of the Utah Territory from 1850 to 1858. He was also a Freemason (remember the Masonic ring, weeks ago?).

Polygamy doesn't come up! What?!? We're in a generic sort of romance plot, where the innocent flower is to be given to a less noble and honest man than her preferred suitor. We know that the Drebber son is going to turn out to be a terrible man, but there's nothing especially indicative of it in Brigham Young's proposal. Since there's no mention of young Drebber or young Stangerson having pre-existing wives, it's likely Lucy is being offered the position of the legally married first wife.

Ferrier's plan is to flee. Since Doyle's readers are in the future, they may have a tingle of fear related to the doctrine of "blood atonement" (which was discussed in Stenhouse's book as well as in newspaper accounts) and the 1866 murder of Dr. Robinson.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

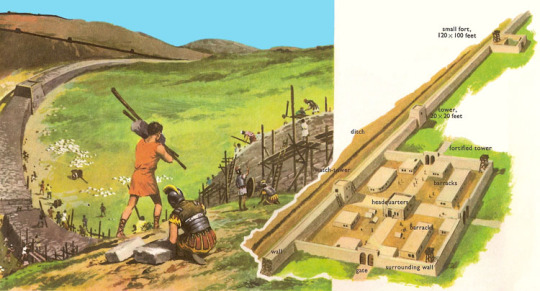

January 24th, 76AD, is the probable date of birth of Publius Aelius Hadrianus, who built Hadrian’s Wall.

Right let’s start with the myth, a lot of people believe it marks the border between Scotland and England, and never has. In fact, the wall predates both kingdoms, while substantial sections of modern-day Northumberland and Cumbria – both of which are located south of the border – are bisected by it.

This post is a lot longer than I would normally do, Hadrian himself ruled for over 30 years , and the Roman Empire were in Britain for over 350 years. I've taken this post from the Smithsonian web site as I'm tied up trying to do other things this morning

Stretching 80 miles from the Irish Sea in the west to the North Sea in the east, Hadrian’s Wall in northern England is one of the United Kingdom’s most famous structures. But the fortification was designed to protect the Roman province of Britannia from a threat few people remember today—the Picts, Britannia’s “barbarian” neighbours from Caledonia, now known as Scotland.

By the end of the first century, the Romans had successfully brought most of modern England into the imperial fold. The Empire still faced challenges in the north, though, and one provincial governor, Agricola, had already made some military headway in that area. According to his son-in-law and primary chronicler, Tacitus, the highlight of his northern campaign was a victory in 83 or 84 A.D. at the Battle of Mons Graupius, which probably took place in southern Scotland. Agricola established several northern forts, where he posted garrisons to secure the lands he’d conquered. But this attempt to subdue the northerners eventually failed, and Emperor Domitian recalled him a few years later.

It wasn’t until the 120s that northern England got another taste of Rome’s iron-fisted rule. Emperor Hadrian “devoted his attention to maintaining peace throughout the world,” according to the Life of Hadrian in the Historia Augusta. Hadrian reformed his armies and earned their respect by living like an ordinary soldier and walking 20 miles a day in full military kit. Backed by the military he had reformed, he quelled armed resistance from rebellious tribes all over Europe.

But though Hadrian had the love of his own troops, he had political enemies—and was afraid of being assassinated in Rome. Driven from home by his fear, he visited nearly every province in his empire in person. The hands-on emperor settled disputes, spread Roman goodwill, and put a face to the imperial name. His destinations included northern Britain, where he decided to build a wall and a permanent militarized zone between “enemy” and Roman territory.

Primary sources on Hadrian’s Wall are widespread. They include everything from preserved letters to Roman historians to inscriptions on the wall itself. Historians have also used archaeological evidence like discarded pots and clothing to date the construction of different portions of the wall and reconstruct what daily life must have been like. But the documents that survive focus more on the Romans than the foes the wall was designed to conquer.

Before this period, the Romans had already fought enemies in northern England and southern Scotland for several decades, Rob Collins, author of Hadrian's Wall and the End of Empire, says via email. One problem? They didn’t have enough men to maintain permanent control over the area. Hadrian’s Wall served as a line of defense, helping a small number of Roman soldiers shore up their forces against foes with much larger numbers.

Hadrian viewed the inhabitants of southern Scotland—the “Picti,” or Picts—as a menace. Meaning “the painted ones” in Latin, the moniker referred to the group’s culturally significant body tattoos. The Romans used the name to refer collectively to a confederation of diverse tribes, says Hudson.

To Hadrian and his men, the Picts were legitimate threats. They frequently raided Roman territories, engaging in what Collins calls “guerilla warfare” that included stealing cattle and capturing slaves. Starting in the fourth century, constant raids began to take their toll on one of Rome’s westernmost provinces.

Hadrian’s Wall wasn’t just built to keep the Picts out. It likely served another important function—generating revenue for the empire. Historians think it established a customs barrier where Romans could tax anyone who entered. Similar barriers were discovered at other Roman frontier walls, like that at Porolissum in Dacia.

The wall may also have helped control the flow of people between north and south, making it easier for a few Romans to fight off a lot of Picts. “A handful of men could hold off a much larger force by using Hadrian’s Wall as a shield,” Benjamin Hudson, a professor of history at Pennsylvania State University and author of The Picts, says via email. “Delaying an attack for even a day or two would enable other troops to come to that area.” Because the Wall had limited checkpoints and gates, Collins notes, it would be difficult for mounted raiders to get too close. And because would-be invaders couldn’t take their horses over the Wall with them, a successful getaway would be that much harder.

The Romans had already controlled the area around their new wall for a generation, so its construction didn’t precipitate much cultural change. However, they would have had to confiscate massive tracts of land.

Most building materials, like stone and turf, were probably obtained locally. Special materials, like lead, were likely privately purchased, but paid for by the provincial governor. And no one had to worry about hiring extra men—either they would be Roman soldiers, who received regular wages, or conscripted, unpaid local men.

“Building the Wall would not have been ‘cheap,’ but the Romans probably did it as inexpensively as could be expected,” says Hudson. “Most of the funds would have come from tax revenues in Britain, although the indirect costs (such as the salaries for the garrisons) would have been part of operating expenses,” he adds.

There is no archaeological or written record of any local resistance to the wall’s construction. Since written Roman records focus on large-scale conflicts, rather than localized kerfuffles, they may have overlooked local hostility toward the wall. “Over the decades and centuries, hostility may still have been present, but it was probably not quite as local to the Wall itself,” says Collins. And future generations couldn’t even remember a time before its existence.

But for centuries, the Picts continued to raid. Shortly after the wall was built, they successfully raided the area around it, and as the rebellion wore on, Hadrian’s successors headed west to fight. In the 180s, the Picts even overtook the wall briefly. Throughout the centuries, Britain and other provinces rebelled against the Romans several times and occasionally seceded, the troops choosing different emperors before being brought back under the imperial thumb again.

Locals gained materially, thanks to military intervention and increased trade, but native Britons would have lost land and men. But it’s hard to tell just how hard they were hit by these skirmishes due to scattered, untranslatable Pict records.

The Picts persisted. In the late third century, they invaded Roman lands beyond York, but Emperor Constantine Chlorus eventually quelled the rebellion. In 367-8, the Scotti—the Picts’ Irish allies—formed an alliance with the Picts, the Saxons, the Franks, and the Attacotti. In “The Barbarian Conspiracy,” they pillaged Roman outposts and murdered two high-ranking Roman military officials. Tensions continued to simmer and occasionally erupt over the next several decades.

Only in the fifth century did Roman influence in Britain gradually dwindle. Rome’s already tenuous control on northern England slipped due to turmoil within the politically fragmented empire and threats from other foes like the Visigoths and Vandals. Between 409 and 411 A.D., Britain officially left the empire.

The Romans may be long gone, but Hadrian’s Wall remains. Like modern walls, its most important effect might not have been tangible. As Costica Bradatan wrote in a 2011 New York Times op-ed about the proposed border wall between the U.S. and Mexico, walls “are built not for security, but for a sense of security.”

Hadrian’s Wall was ostensibly built to defend Romans. But its true purpose was to assuage the fears of those it supposedly guarded, England’s Roman conquerors and the Britons they subdued. Even if the Picts had never invaded, the wall would have been a symbol of Roman might—and the fact that they did only feeds into the legend of a barrier that’s long since become obsolete.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stelyuzia is best known of it's army, and rightfully so, while nowhere near undefeated in the way it's propaganda portrays, the Stelyuzian Ground Forces have long been rightfully feared by any peer adversary. This is primarily thanks too an extremely effective combined arms doctrine that places heavy emphasis on overwhelming fire superiority, working in tandem with a cohesive and well organized military structure.

Stelyuzian offensive campaigns typically work in stages, but in simplest terms air forces provide support to heavy artillery barrage, followed up by armored assaults being closely followed behind by infantry. There's a great deal more complexity to it than that but historically, this has been what has won Stelyuzia the day in peer conflicts. Guerilla warfare and COIN operations are another matter, but that's not our focus today.

By comparison, Stelyuzias primary historical peers have all lacked something. The White League of Pharose, technically a military coalition of the various Pharosian national military's, has come the closest to outright trouncing the Stelyuzian military in open war. Lessons learned from the Pharosian War make up the basis of even modern Stelyuzian military theory. The White Leagues strategy was sound, their tactics excellent, and their manpower ample and committed. The difference was, unfortunately, technology and political infighting as the war dragged on. Pharose had worked hard to close the technological gap after opening it's borders and entering the interstellar stage, but was still lacking in even things as basic as modern small arms.

The Grand Armée of the Republique of Tov is a competent fighting force that more than matches, and often surpasses, Stelyuzian technology! But it is hampered by it's haphazard and disorganized structure that breeds infighting among leadership and disorder on the field and creates total chaos in the logistics system with incompatible parts and munitions between it's constituent organizations. That's without touching chronically poor morale among enlisted troops and conscripts and the rampant corruption among senior ranks.

The Enduran Independence Coalition had uncontested technological superiority in it's day. By it's height, it even fielded fully sealed combat helmets with Heads Up Displays alongside basic exosuits to even it's most basic infantry! But it was never able to match the sheer manpower or material resources of Stelyuzia, leading too an over reliance on it's special forces that simply could not make up the difference. That's without going into the high cost and over-engineered nature of it's vehicles and gear making repairs costly and downtime lengthy.

I lay all this out, because it makes an interesting contrast to the Stelyuzian Navy. While the Ground Forces adapted and learned from the Pharosian War, the Navy has managed to maintain such a strict adherence to tradition that it is effectively unchanged from it's initial formation.

Stelyuzian Naval Doctrine is fundamentally that the Navy's sole function is to support the Ground War. Everything it does is in support of this, all it's offensive tools and defenses exist only too allow it to continue providing supplies and reinforcements to the ground side. This has lead to an extremely static and long range battle order, with a heavy over reliance on Battleships and Siegeships. Every other variant of ship in a fleet is either purely logistics or only exists to protect the battleships and Siegeships. Even Carriers, the heart of basically every other navy, are small and only launch their Void fighters to intercept hostile fighters moving in range of the fleet.

It is not to say that the Stelyuzian Navy is in anyway useless, far from it, but historically even it's proudest victories were pyrrhic. The famed Winter Offensive that ended the Pharosian War decisively had an attrition rate of 3 Stelyuzian ships for every 1 Pharosian ship. Some particularly brave historians even suggest that the Winter Offensive only succeeded because of the direct support of the Tovi navy to make up for the Stelyuzians inflexibility.

In many ways, had the Winter Offensive failed, it's likely that both the war would have ended in a peace treaty instead of the glassing of Pharose and that the Stelyuzian Navy would have been forced to reform. Though, given the history of post war Stelyuzia under the Immortal Council, the latter may be wishful thinking.

Interestingly, the Navy of the Republique has always existed in stark contrast to the Grand Armée. Where the Army is essentially a collection of six competing paramilitaries in a trench coat, the navy is and always has been a single organization. With no battleships and only one Siegeship to a fleet, the Republique navy instead focuses on a highly mobile order of battle centered around its' massive carriers. Republique Void Fighters are critical to any engagement and most other ships utilize speed or stealth to get in range to deliver devastating missile barrages.

#setting: følslava#world building#this is sorta rambly but i wanted to type it out#barely proof read

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday Firesides: Iron Hearts in Wooden Ships

During the Civil War, the Confederacy’s greatest hope for its defense of New Orleans, and the Union’s greatest fear in securing its capture, were the former’s fleet of ironclad ships.

As it turned out, the ironclads proved ineffectual, and the Confederacy’s overall defense, hampered by disorganization and what one historian called the “cowardice of untrained officers,” fell apart. The Union Navy handily muscled its way up the Mississippi to capture the South’s largest city.

Theodorus Bailey, the Union’s second-in-command on the operation, summed up the lopsided victory this way:

“It was a contest of iron hearts in wooden ships, against iron-clads with iron beaks—and the iron hearts won.”

A half-century later, during WWI, German officer Ernst Jünger reflected on Bailey’s words in criticizing orders to dig more, and more elaborate, trenches, to the exhaustion and demoralization of his men. “Trenches are not the first thing, but the courage and freshness of the men behind them. ‘Battles are won by iron hearts in wooden ships.’”

Certainly, superiority in technology — and resources — has been the difference-maker in many conflicts. But just as often, an under-resourced and technologically less advanced force, bands of “primitive” but ferociously devoted guerillas, have successfully held off far more formidable foes.

It’s easy to think that a lack of some technology or resource is the only thing holding us back from success in our non-martial endeavors — that some app or funding will be the thing that finally allows us to lose weight or launch a thriving business.

At best, such things can aid existing efforts. At worst, they can be a distraction from the more fundamental linchpins of success: will, leadership, persistence.

Victory in any battle depends less on the quality of the vessel in which you fight, and more on the quality of the man who stands at its wheel.

Help support independent publishing. Make a donation to The Art of Manliness! Thanks for the support! http://dlvr.it/T4BPVy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was Once A Princess

My concept art of Zamfir before Dracula’s attack on Târgoviște. (A little bit more Germanic clothing than it should be and it's the wrong time period...) I used Anne of Cleves as inspiration for the top left one.

Awhile back, I made a post about Zamfir, specifically speculating on Sypha’s line of asking if she was the ‘last person of noble birth left alive’ when everything went to hell. Due to her...devotion, I guess, to the royals, I like to play with the idea she was the daughter of the dead Prince. This would explain how she found herself at the head of the capital's guerilla resistance force.

What I imagine happened was after Dracula's castle landed in the heart of the city and the place became overrun with demons, the court fractured into a least two groups: Zamfir's underground faction and a faction that gave up Târgoviște as lost, fled south, and established a new court in Bucharest. (Historically, Wallachia's capital did move from Târgoviște to Bucharest around this time.) For a little bit of context, the Wallachian throne had been contested by the Dănești and Drăculești branches of the ruling family since 1420, some 56 years before Castlevania takes place. So if the reigning monarch were to die, the boyar lords would not have hesitated to flock to the next viable option. Zamfir, on the other hand, seemed to have the people of the Underground Court pretty convinced the royals were alive and well, so they may have been doggedly believing her promises and clinging to the old regime.

Due to the hostile environment of the court, Zamfir was probably already deeply disturbed before Dracula's attack. If she was the Prince's daughter, she's living a world where her father could be at any time deposed, either by his own people or by an outside force, or even betrayed and murdered by his own family members. As a woman, she wouldn't be able to present herself as a claimant to the throne and so would not be in danger of being murdered as a political rival, but the sudden loss of her father would still threaten her already tenuous place of safety. Her madness didn't start with Dracula; he probably just finished what the Wallachian political scene started.

...

As to the identity of dead prince himself, he can only be Vlad III Dracula or Basarab Laiotă and at the same time, it's impossible for him to be either. It's unlikely the prince has the same name as the vampire and Basarab Laiotă doesn't die until 1480.

To reconcile this, I'm calling the reigning prince Dan III because Dan III did not exist and is often confused by historians with Vladislav II, who may have simply used the name as an alias. (Ever misunderstand something so bad that you accidentally invent a whole-ass dude?)

...

Another thing of note is Zamfir is a Romanian surname that denotes a jeweler, not a given name. With this information, she's neither a Dănești or a Drăculești, but she could be an illegitimate child of the prince. Illegitimate children in Wallachia didn’t have the same status as they did in the west. Any one of a man’s sons had the opportunity to inherit. The daughters were another story, but the Prince still could technically acknowledge her as his if he chose.

#castlevania#zamfir#dracula#targoviste#castlevania headcanons#castlevania fanart#castlevania netflix#historical context#medieval wallachia#medieval romania#medieval history#medieval europe

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Regarding your most recent ask—why do you think Alexander got so violent during the last leg of his campaign? I get he and his men were tired, that he was pissed at them too, but as you pointed out, his behavior in India was so bloodthirsty I can’t even fathom. I just can’t put my head around what could’ve possibly flipped that switch inside of him when, previously, his violence seemed to have served a purpose (understandable, and calculated, not pardonable though of course). In the last years of his life the level of violence was just crazy for no good reason.

Why Alexander became increasingly vicious, especially in India, has been asked by a lot of historians. Unsurprisingly, there are several general categories of answers:

1) He’d come to think of himself as a god and/or suffered increasing megalomania to the point that resistance in any form was met with offended outrage and violence.

1a) He’d proven himself so many times in combat, why were these stupid Indians still resisting? Why couldn’t they just surrender already?

2) He’d been through increasingly brutal guerilla warfare in Baktria and Sogdiana for three years, so when he faced similar resistance in India, he had a very short fuse.

2a) Years of combat and exposure to violence had numbed his sense of compassion, or his ability to see “the enemy” as human. E.g., non-stop war turned him cruel.

3) Indians were sufficiently different that he didn’t regard them with the same sympathy he had granted more familiar populations. If not necessarily full-on Aristotelian racism, it fell into the category of, “It’s harder to feel compassion for people who don’t look like you.’

Our big problem answering is that this question delves into motivation, which is psychological. We can’t plop him on a couch to psychoanalyze. The best we can do is consider what attitudes his culture might have most predisposed him towards.

I don’t give much credence to #1 as I don’t think he believed himself a “living god,” only a hero (Herakles 2.0) who might expect deification upon death—but not while alive. As for “megalomania,” it’s beyond our capacity to diagnose, and perhaps altogether anachronistic.

I do think #1a, #2, #2a, and #3 were all at work to varying degrees.

Alexander was enormously competitive. He wanted a challenge. That’s why he treated Poros so well after the Battle of the Hydaspes. Poros hadn’t run away, and he’d fought a good battle. A pitched battle with a decisive outcome. Alexander didn’t really like sieges. They were long and messy and typically ended badly, even if he won. But a set-piece or pitched battle took less than a day, and it was over. This one in particular ticked all his boxes: talented, brave opponent, clear victory, and his opponent surrendered (didn’t escape).

It wasn’t combat in itself that put him off. It seems to have been the sheer stubbornness of the Indian resistance. If we recall, he was extremely unsympathetic to Gaza and Batis when that city still opposed him despite his victory after a 7-month siege of Tyre. His behavior at Gaza had a clear intimation of: “Dammit! I just took the ‘untakable’ city, why are you resisiting?”

If Alexander liked a challenge, he didn’t like “repeating himself,” so to speak. He had to repeat himself a lot in India, ergo, both #1a and #2 are in effect.

As for #2a and #3, it can be uncomfortable for those fascinated by Alexander to accept he had a vicious side. We want to justify it. “He was brutal to ___ because….” I find myself doing it too. But after a number of conversations with students in my classes on Alexander or Greek warfare, themselves war vets, Alexander the soldier is a reality we can’t ignore.

These vets talked about their process of training—indoctrination—that conditioned new recruits to become part of “the group,” but also to dehumanize “the enemy.” It’s one difference between “soldiers” and “warriors.” There is, I think, a tendency to look down a bit on warrior societies as more “primitive.” Yet in warrior societies, the focus is more on the individual warrior’s bravery and honor. They don’t develop as much same group-think that leads to a smoothly operating war machine…but can also lead to war crimes. Do what you’re told; don’t think about it. The enemy is less-than-human and deserves death and torture.

That’s a broad generalization I don’t want to push too far; some warrior societies were quite insular and violent. But if the training/indoctrination involved in turning out soldiers certainly professionalizes an army—like the Macedonians—it also allows them to engage in a level of atrocity that’s mind-boggling to those outside the system. The longer one fights, the more violence one sees, and that requires a certain disassociation in order to remain sane. One of my former students who left the military and became very left-leaning was unambiguous about the process of numbing soldiers to the need to kill or engage in violence—“even for the guy down in the mailroom.” And of course, part of military separation involves teaching these now-former soldiers to become part of civil society again.

The upshot is that is we can’t dismiss the impact of near-continual violence on Alexander. He’d been in charge of military operations from at least the age of 16, and had probably killed in battle some time before that. In Dancing with the Lion: Becoming, he’s 14; that’s not unreasonable.

Not only did he engage in violence intrinsic to a war machine, but death and violence was intrinsic to daily life in everything from food preparation to religious sacrifice. It’s not that our world is less violent, but that violence these days is segregated, largely by wealth, in a way it just wasn’t then. I go to the grocery and buy my pre-packaged deboned chicken breast, whereas both my grandmothers walked out into the chicken yard, grabbed a chicken, wrung it’s neck, plucked feathers, and only then could get down to the business of cooking it for dinner.

Furthermore, human slavery was endemic. Alexander’s teacher, Aristotle, spoke of slaves as “human animals.” The problem for ancient people was how to explain why some became slaves when others were masters. Simple chance was recognized by some, but far more tried to explain it as the disfavor of the gods, or as some sort of “natural” inferiority (as Aristotle did). It wasn’t the racial slavery of the Atlantic slave trade, but it certainly sowed the seeds.

Thanks to the long shadow of W.W. Tarn, a popular perception persists of Alexander as a proponent of One World politics (Brotherhood of Mankind). Yet Brian Bosworth has shown rather convincingly via officer and political appointments in his latter years, that Alexander grew more cynical about foreign peoples. That doesn’t mean he got more racist exactly, but he grew progressively more distrustful. It might be better to think of him as naïve when he started out, but experience rubbed off that innocence.

As he was un-learning trust, he was also encountering cultures—and landscapes—increasingly alien. I don’t think he ever lost his curiosity, or his basic “approach” attitude to difference. He liked learning about new things and people. But plenty of psychological studies have shown that most of us display increased sympathy towards those who look like us. It’s not that we can’t be sympathetic towards others, but we’re apparently hardwired to care more about people we perceive as “like us.” It’s no doubt linked to survival: protect the family, the tribe. The flip side, of course, is that it’s easier to walk by someone in distress, or to actively harm them, if they’re “not like us.” Alexander’s friendship with Poros shows that he remained able to see The Other as human. But I suspect the cultural and physical differences also made it easier for him to disregard not just Indian suffering, but Baktrian and Sogdian and Persian, as well.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander in India#the violence of Alexander the Great#soldier indoctrination#increasing tolerance for violence among soldiers#violence in the ancient world#Classics#tagamemnon#violence in ancient warfare#violence in daily life in the ancient world

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victoria 2 game

The map of Europe after the Silesian Wars. After the Austrian Republic unified all the Germanies in the 1860s, many thought it would be a great superpower in the center of Europe, however the prediction that the Austrians would be able to finally tame this tumultuous part of Europe was sorely mistaken. After the unification of Austria with its various other German states, the Hungarian congress decided to attempt to push the cause of independence. However before any discussions of a peaceful separation could go through was the first of many coups and the long string of dictatorships that would haunt the small republic. The first dictator would institute a few reforms like splitting up the republic into autonomous republics, these being Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Dalmatia, the Croatian Military Frontier, Western Ukraine, and Bukovina. Slovenia would also eventually be added to this list as well as the independence of Poznan. Each head of state was personally picked by the dictator of Germany at the time which would cause issues down the line when the second dictator came to power a few years later from a coup. the 2nd dictator would come to fight with the heads of state and name himself as the protector of all German minorities in these states. Though he threatened to replace and re-annex much of these republics, he only succeeded at re-annexing the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia and a partition of Poznan with the Russian Empire before also meeting his fate in the gallows of Vienna only 3 years after his inauguration

The 3rd dictator came to power not from a coup, but a popular uprising in the capital. He was a small time bureaucrat who was able to capitalize on the resentment of various German nationalists on two decades ago loss of territory to the Republic of France. The territory France had taken were the at the time independent principalities of Baden and Pfalz. However the war would come to a complication as Germany’s number one ally at the time was the United States who was also allies with France. So when Germany began the invasion of France to retake territories and also claim the land of Elsass-Lothringen from France, the United States would declare neutrality with under-the-table financial support towards Germany. Many believe the implicit support of the United States was due to the ongoing colonial race in Western Africa between it and France, but historians are unsure why it truly happened

The war lasted a short month as Germany surprised and easily outmanned the French as the border was mostly undefended. Thus our 3rd dictator was declared a hero for the conquests, but it only took 3 years for this honeymoon period to sour. As Germany would be plunged into a failed coup turned civil war. As the Republic of Prussia was declared in the country’s East and the Rhine. Though the Rhine region of the war would collapse in only 7 months, the entire war would last 7 years and have two Germanies vying for power in Europe with the Prussian dictatorship beating out the eyes of the German dictatorship. International brigades from the United States and Italian Republic would attempt to help their respective sides by trying to take out rebel hideouts in Germany and Prussia, the rebels proved far more powerful than anticipated and both left the country in shame

Though the direct war between Germany and Prussia would stop, the effective cold war and build up of troops as well as the near constant guerilla armies would continue. Silesia would prove the most volatile and unstable part of this conflict as it made much of Germany entirely ungovernable

At the start of 1887, various rebel groups from Silesia would contact the government of the United States and the French Republic. Telling of tales of the massacres done by the Prussian government and the squalid refugee camps of the German government. The two made an agreement to support the Silesian rebels in their fight against the Prussian government and attempt to mend the situation in Germany once and for all. The two were able to get Italy to agree to the situation by promising a concession of the Italian portion of South Tirol to Italy as well as generous concessions at the end of the war. As Italy was the premiere land military power of Europe after Prussia. However Prussia was able to agree to help to convince the Russian Empire and Spanish Empire to support its cause with the promise of French colonial concessions and the return of the previously lost Alyaska Oblast from the Americans. And so began the war

The German Republic was technically neutral in this war, however was the battleground for much of the war due to its turmoil as well as being the only area being able to host the American navy. Though even then, armies traveling through Germany had an extremely hard time even getting to the front without getting assailed by the various rebel armies and also Russian patrols. The American army was first to the scene and was able to capture Prussian Stettin, the capital of Prussia, but was unable to make any in-roads into Silesia proper. The Pyrenees Front was however going much better as the French made quick headways into Catalonia and Basque Country. Though both fronts would become hypercharged when the Italian double-headed offensive was able to break through two stalemates simultaneously. Both being able to fight off the Prussians and Russians on the Eastern Front and being able to fight off the Spanish on the Western Front

The hardest hit fighting was on the Spanish front as the Spanish line would collapse rather quickly as the entire country fell to the French-Italian threat. Spain would attempt some Hail Mary plays such as invading the United States by island hopping through Alaska only for the expeditions to die to the cold. The American Pacific Fleet would also capture the Marianas, Caroline, and Philippine Islands

The Eastern Front was more slow-going as the amount of troops would require much more careful planning. Though the armies were able to eventually push past Pomerania and Silesia into Russian Poland

With the conquest of Poland, the imperial powers would surrender at the Congress of Strasbourg. The United States mandated the creation of Poland and the creation of an independent Ukraine that goes all the way to the Dnipro River. Romania would also gain the territory of Bukovina and Bessarabia from Germany and Russia respectively. America would also mandate the turning over of all of Western Sahara to the Kingdom of Morocco from Spain as well as the colonies of the Spanish Pacific being handed over to the Americans. America would also mandate that Portugal be given Galicia to follow more ethnic lines of Iberia. America would also come to mandate that Georgia be given all the territory of Russian Tiflis. America would go against French demands for Alsace and negotiate with France to create the Republic of Alsace as a buffer-state between Germany and France that was under French influence.

France would mandate the creation of an independent Basque Country from Spain as well as annexing Spanish Catalonia. France would also demand the colonies of Spanish Western Africa. France would also demand concessions from Germany to give over the territory of Vorarlperg and Liechtenstein be handed over to Switzerland and the German territory of Cleve being given over to the Netherlands. France would also replace the government of Germany with a provisional French authority as well as re-unifying Germany and Prussia. Germany would keep the territory of Bohemia, Hungary, and Slovenia as autonomous regions of Germany.

Italy would demand concession of Dalmatia, Istria, Italian populated South Tirol, as well as the separation of Czechia and Slovakia. With Slovakia being governed by the Italian authority til further notice.

Though despite the fact that the Russian Empire was fighting on the opposite side, Russia would also gain some concessions. Russia’s diplomats to Serbia were able to convince the treaty organizers to create the nation of Yugoslavia with the king of Serbia as the head of state, so the Kingdom of Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia were merged into Yugoslavia. The king of Serbia then declared his fealty to the Russian Tsar which made Yugoslavia a satellite of the Russian Empire. So Russia both lost and gained territory

#Cursedmaps#victoria#victoria 2#victoria 3#map#alt history#lore#lore dump#1889#united states#germany#great war#prussia#france#spain#spanish empire#czechia#bohemia#portugal#america#poland#yugoslavia#alsace#ukraine#italy#serbia#russia#romania

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 39 The Basmachi Organize in the Ferghana 1918-1920

The Basmachi, who are often thought of as the great bogeyman of Turkestan, spent most of 1918 and 1919 organizing themselves, mostly in the Ferghana, but there were a few units in the Khiva and Bukhara Emirates as well. The Basmachi originated in the aftermath of the 1916 Central Asian Revolt, but don’t really form the concept of the Basmachi until the fall of Kokand in 1918. By the end of 1918, there were 40 plus self-organized Basmachi units with three men emerging as effective enough leaders to unite the different groups: Irgush of Kokand, Madamin Bey whose family originated from Kokand royalty, and Ibrahim Bek who was organizing in Bukhara and was loyal to the Bukharan Emir. For this episode, we’ll focus on Irgush and Madamin in the Ferghana and save Ibrahim’s story for the greater story of the Bukharan Emirate

Irgush, who was the chief of Kokand’s militia, and Madamin both fled to Ferghana after the fall of the Kokand Autonomy and organized different branches of Basmachi. Irgush led the first attack against the Russians and by the end of 1918, he had raised an estimated 4,000 fighters (Olcott’s article). Madamin Bey enjoyed the support of the ulama, merchants, and moderate members of the Basmachi and the Ferghana Valley. By the end of 1918, both men had built minor fiefdoms for themselves, and it was clear that either they learned how to work together or risked destroying their own movement by fighting with each.

The Situation in Turkestan in 1919

In 1919, the Basmachi were facing three main problems: famine, the Bolshevik forces and the Jadids, and competition amongst each other.

As we’ve talked in our previous episodes, the Russian Civil War disrupted Turkestan’s food supplies, plunging the region into mass starvation while the Russians used armed groups to forcibly requisition food from the poor indigenous and Russian farmers. According to Jeff Sahadeo, an estimate 30% of the Ferghana population died in the famine, which is one of the reasons why it became a Basmachi stronghold. The more the Russians stole from the people, the more they fled into the Basmachi’s ranks. Some of these new recruits included Bashkir, Tatar, and Jadid reformers as well as ulama and conservative merchants. To try and counter this, the Russians switched the focus of their requisition efforts from the indigenous peasants to the Russian peasants while waiting for Red Army reinforcements.

For their part, the Basmachi focused on raiding military supply depots, burning warehouses and ginning factories, as well as attacking mines and oil wells. While the Russians tried to enforce mass arrests, they could never penetrate the Basmachi’s territory in the Ferghana. Instead, their efforts seemed to only help the Basmachi recruitment efforts. Yet, while the Basmachi and Russians were enemies, which didn’t prevent local units from making agreements with each other and it seems like deals were frequently made and broken. During the winter, when food was scarcer than it was already, the Basmachi would reach out to local Russian garrisons to share food and supplies. Once winter was over, the Basmachi would resume attacking Russian units and supplies.

While the Basmachi raided and fought with the Russians, their true enemy were the Jadids and other Muslim reformers. Given the Basmachi’s conservatism and belief in traditional Islam, they thought the Jadids were the greatest enemies of Turkestan. Ibrahim Bek, the leader of the Bukharan Basmachi, once wrote to a Red Army commander:

“Comrades, we thank you for fighting with the Jadids. I, Ibrohim-bek, praise you for this and shake your hand, as friend and comrade, and open to you the path to all four sides. I am also able to give you forage. We have nothing against you, we will beat the Jadids, who overthrew our power.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan pg. 88

Ibrahim’s hatred of the Jadids seems to have matched the Emir’s own views. One of his officials once wrote,

“Irgush-Bek of Kokand and Muhammad Amin of Margealn with their courage and fortitude have for some time been…exposing and killing Jadids and Bolsheviks” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 88

It seems he was still sore the Bukharan Jadids used Kerensky’s Provisional Government to curb his power.

Despite the Basmachi’s antagonism to all indigenous people who threatened traditionalism and conservatism, Turar Risqulov, the leader of the Musburo, actually reached out to Madamin Bey to negotiate an uneasy peace so they could address the raging famine. Madamin was open to negotiations and in the end, they agreed that Madamin’s forces would keep their arms and organization but would become local units of the Red Army. The local Russians allowed this until Frunze arrived and broke the agreement, killed Madamin, and focused on breaking the Basmachi as an alternative form of government in the Ferghana.

Finally, the Basmachi, who were really modern-day warlords, realized they needed to organize their forces and split up their territories before they ended up fighting with each other.

How Does One Organize a Guerilla Force?

The Basmachi were neither coordinated nor centralized and as more and more groups popped up and more and more people joined their ranks, Irgush and Madamin realized they needed to get properly organized. So, in March 1919, Irgush called a meeting of 40 Basmachi leaders to talk about a unified command. By the end of the meeting, Irgush was nominated as the Supreme Commander with two deputies: Kurshirmat, a well-known ally of Irgush, and Madamin. Each of the 40 leaders present received control over a separate territory to protect and administer with support from the ulama as their religious-political advisors.

This structure lasted until the summer of 1919 when Madamin went his own way. At some point in 1919, Madamin met the Russian commander, Konstantin Monstrov, commander of the (Russian) People’s Army in Turkestan. He was just one of the many armed organizations in the region at the time. They united their forces, Madamin’s guerilla unit transformed into the Muslim People’s Army, and together they created the Ferghana Provisional Government which would outlive both of its founders by a few months.

Madamin and Monstrov created a constituent assembly and drew up an eight-point platform to ensure freedom of speech, press, and education for the people. They called for an elected assembly and a five-member cabinet, although it’s doubtful if they ever held elections. Like the Kokand government, it failed to execute any meaningful policy, but gained political recognition and aid from abroad. This would lead to claims that this government was an evil British plot to take Turkestan away from the Russians, nullifying any independent action on the basis of Madamin and Monstrov. While it seems that the British were aware of Madamin and his work, sent him financial support, and even sent agents to negotiate with him, it’s doubtful they masterminded the creation of the Ferghana Provisional Government. The Soviets would make similar claims about the Turkestan Military Organization, a unit consisting of former Tsarist officials and generals. You can learn more about them and the Soviet’s claim by joining our Patreon and gaining access to our exclusive episode on Osipov’s Uprising.

Monstrov and Madamin knew they would not survive long if they did not defeat the Bolshevik forces in the region. Together, they took the city of Osh in September 1919 and were involved in the siege of Andijan where they encountered Frunze’s Red forces. He pushed them to the modern-day Kyrgyzstan-Xinjiang border. Frunze captured and executed Monstrov in January 1920 and Madamin surrendered his forces and formally joined the Bolsheviks in March 1920. He would die later that summer.

By the end of 1919, the Basmachi of the Ferghana attempted to organize their forces to improve their effectiveness. They recruited 20,000 fighters, organized a Provisional Government with a Russian army also aligned against the Bolsheviks, and were impeding the Bolshevik’s efforts to gather supplies and establish their hold on the Ferghana. Even though Madamin would die in 1920, he left behind an organized guerilla force under the command of men like Irgush, Ibrahim Bek, and others who would prove, not only to be a thorn in the side of Frunze and the Red Army, but also entice a certain former Ottoman general to join their cause and attempt to regain lost glory.

References

“The Basmachi or Freemen’s Revolt in Turkestan 1918-1924 by Martha B. Olcott

“Revolution in the Borderlands: The Case of Central Asia in a Comparative Perspective” by Marco Buttino

“Some Aspects of the Basmachi Movement and the Role of Enver Pasha in Turkestan” by Mehmet Shahingoz and Amina Akhantaeva

Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent 1865-1923 by Jeff Sahadeo

The “Russian Civil Wars 1916-1926 by Jonathan D. Smele

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Central Asia: Aspects of Transition by Tom Everett-Heath

#queer historian#central asia#history blog#central asian history#queer podcaster#spotify#basmachi#ibrahim bek#madamin bey#guerilla warfare#Spotify

0 notes

Text

Fanfic Friday

Once again I am asking you to consider reading the first chapter of From the Firmament, my arranged marriage au set in a world inspired by Ancient Rome and its environs.

Stede is a blue-blooded patrician from A Society That Isn't Rome and Ed is a guerilla war hero from a nomadic steppe tribe confederation. Their two societies have been at war off and on for over a century, and the hope is that this marriage will allow for peace once and for all. Asides/quotes from future historians in this world elaborate on how successful this was, and what ripple effects their connection had on the world around them (some big, some small, some lost to time).