#henry iv of france

Photo

→ history + the war of the three henrys (1587-1589)

requested by anonymous

The edict proscribing Protestantism led to war - the war known as the War of the Three Henries; Henry III, Henry Duke of Guise, and Henry of Navarre. During its course Henry of Navarre gave an indication of the fine military qualities he possesed by winning a brilliant victory in a pitched battle. But the war dragged on. More and more it became evident that the King was an unwilling partner and that he and his mother were doing their rather futile best to bring about peace, while more and more Guise and his adherents showed their contempt for the person and authority of the King and their determination to pursue their own ends in defiance of him. – J. E. Neale, The Age of Catherine de Medici

#historyedit#henry iii of france#henry iv of france#henry i duke of guise#war of the three henrys#16th century#french history#early modern history#*mine#*history#*requests#cw: blood#not my best but eh

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

me: *learns about charismatic male historical figure*

me: wow this person seems so fascinating, I have to learn more about him

him: *corrupt creep who preyed on 14 year old kids*

#and there's worse dear god#this shit keep fucking happening#wtf#history#napoleon bonaparte#hadrian#fidel castro#che guevara#augustus#charles II#louis xv#henry iv of france#elvis#elvis presley#text

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henri IV caracolant devant une dame à son balcon

by Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

#henry iv of france#henri iv#nicolas antoine taunay#france#navarre#king of navarre#king of france#history#art#painting#europe#european#château de pau

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henri de Navarre looks shiny and handsome. Baron de Rosny`s looking at him in astonishment

#Henri de Navarre#Henri IV#Maximilien de Bethune#Duc de Sully#Baron de Rosny#french history#16th century#Henry IV of France#Duke of Sully

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ナントの勅令

1598年 - フランス国王アンリ4世が「ナントの勅令」を発布。

0 notes

Photo

↳ family trees + House of Medici (14th - 16th century)

#this has been in my drafts for one year#I wanted to change the font but now cbf#house de medici#lorenzo de medici#giuliano de medici#marie de medici#catherine de medici#henry iv of france#henry ii of france#clarice orsini#contessina de bardi#lucrezia tornabuoni#historyedit#familytrees*#my gifs#creations*

639 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Silk Cloak, 1580-1600, French.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#menswear#16th century#red#silk#cloak#extant garments#v&a museum#France#French#1580#1580s#1590s#1580s cloak#1590s cloak#1580s France#1590s France#16th century france#reign: Henri IV#reign: henri iii

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Napoleon and Henri IV” Chess Pieces

Early 19th century

Artist/maker unknown, French

In the early nineteenth century French emperor Napoléon Bonaparte (1769–1821) was a popular subject for chess sets, appearing opposite a variety of historical figures. Here, the king and queen are represented on one side by Napoléon (in his familiar tricorne) and his wife Joséphine, and on the opposing side by the earlier French ruler King Henri IV (1553–1610) and his wife Marie de’ Medici. As is often the case in French sets, the bishop is replaced by a jester.

(Philadelphia Museum of Art)

#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Henri IV#chess#chess pieces#napoleonic era#napoleonic#19th century#1800s#games#first french empire#french empire#history#french revolution#la révolution française#france#art#19th century art

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

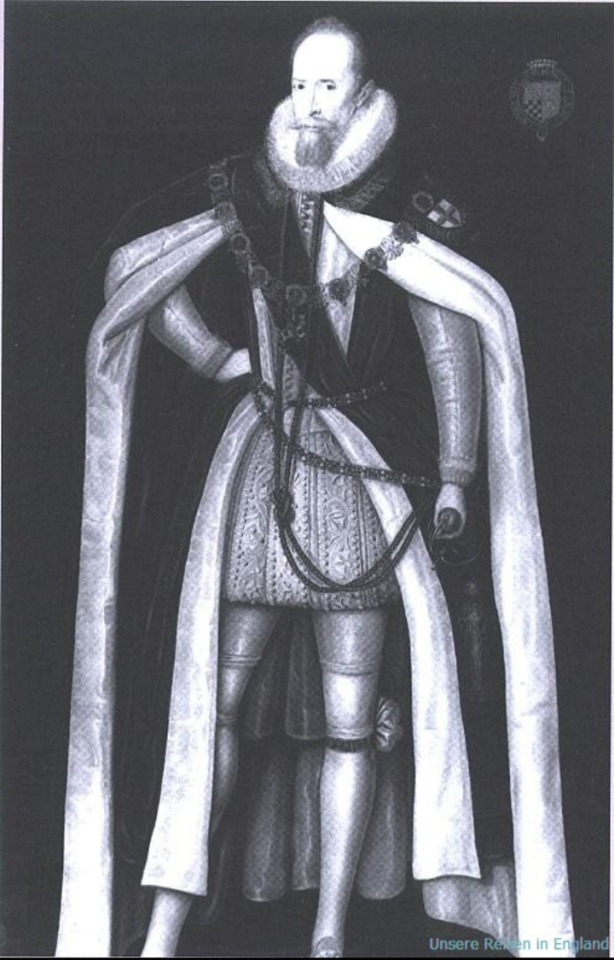

King Henry IV of France. By Frans Pourbus the Younger.

#frans pourbus#frans pourbus the younger#royaume de france#henri iv#roi de france#henri iii#roy de navarre#roi de france et de navarre#vive le roi#maison de bourbon#vert galant#kingdom of france#house of bourbon

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chenonceau

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there,

I noticed you've been following me for awhile thanks. I saw some of your posts on the Howards and noticed that you mentioned somewhere that the Duke of Norfolk might have played a part in Cromwell's downfall in 1540 in order to get revenge for Anne Boleyn's execution.

That's a very interesting theory and I like it. Is there much evidence for any affection Norfolk or the other Howards had for Anne? I've always seen Norfolk as an evil villain who treated his family badly but maybe there was more to him than that?

Hello.

Sorry it's taken such a time to respond, but as you'll see it's VERY long, so I wouldn't start reading this on the bus.

Part One

As a child I used to be very annoyed by 20th-century writers treating historical figures like ice-cold robots welded to lifeless 'logic', and incapable of doing anything rash or ridiculous.

Oh why would Richard kill the Princes when it'd make him look bad?!

See? It must've been a plot by Margaret Beaufort all along.

(I know it's improved since then, but that first impression stuck.)

Reading history, I've always assumed family members instinctively cared for one another, unless their words and actions proved otherwise, and yet the above mentality pushed the exact opposite: that it was 'irresponsible' to even suggest any sort of natural bond between relatives unless they actually wrote it down, which is an absurd standard.

To me it's as silly as saying 'we don't know' if they breathed air as no one put it in a diary.

What does it matter how long ago they lived? They're still people.

I've even seen the extremely smug attitude that caring about one's own children is entirely a 'modern' invention, and the Mediæval and Tudor age wouldn't have understood such a concept.

Wouldn't have understood love!

Since then I've been interested in emotional bonds between friends and family, given how much closer they were than now, particularly rebelling against the idea Elizabeth didn't care about Anne.

And the Boleyns / Howards are my favourites, so their clannish level of kinship fascinates me the most.

Let's go through some of them:

Catherine Howard, Countess of Bridgewater

Catherine's first husband was Rhys ap Gruffydd, heir of a powerful Welsh family.

Problem was when his grandfather died Rhys got passed over (I expect because he was seventeen) in favour of Walter Devereux (the 10th Baron Ferrers), and Rhys wasn't 'avin that.

Devereux arrested him for disturbing the peace, which sent Catherine bananas as she'd convinced herself they were all out to get her husband.

In response she stirred up the local gentry and marched on Carmarthen Castle, threatening to burn the door down and bust on in there if Rhys wasn't freed.

Well after that unease and bitter factionalism bubbled up to denonation point, with servants killed on either side and Catherine attacking and destroying Devereux's property, meaning he sent word to England descibing BOTH of them as leaders of a 'rebellion and insurrection'.

Rhys sounds like a knob to me. You could say Henry caused this mess in the first place, but Rhys ought to have known where all this was leading.

His Wiki page lays it on that he was some noble folk hero martyred to the Reformation, but adding 'FitzUrien' to his name, thereby playing on ancient Welsh myths and thus (supposedly) announcing himself as Prince of Wales, was pushing his luck to say the least.

That's a worse blunder than Henry Howard made and no one ever feels sorry for him.

I shouldn't think he had conspired with James V, but going by this quote from the chronicler Elis Gruffudd (a very interesting fella in his own right) he wasn't universally mourned:

Rhys was beheaded in 1531, but Catherine was in the soup herself after all she'd been up to assisting him.

As Gareth Russell says:

'While we may never know exactly how much his own actions brought about Rhys's death, we can be certain of the devastating effect it had on his widow. She had been intimately involved in her husband's quarrel, and so the possibility that she would be accused of complicity in his alleged treason was tangible.

Left to forge prospects for their three young children — Anne, Thomas and Gruffydd — and fearful for herself, Lady Katherine followed in the footsteps of her elder brother Edmund and flung herself on the mercy of their niece, Anne Boleyn. Once again, the family's dark-eyed golden girl did not disappoint.'

It notable how often you see Anne, and later Elizabeth, willingly pull relatives out of sticky situations, which suggests at least some previous attachment on both sides, as I shouldn't imagine either would be too happy doing it for the more hostile characters.

Compare Katherine's reliance on Anne, a half-niece, to Elizabeth Seymour writing to Cromwell for help, not Jane, her own sister.

'She may even have tried to limit the damage for her aunt and young cousins shortly before Rhys's execution.'

Which was good of Anne considering Rhys had slagged her off, with both of those links having the nerve to imply his death was somehow her doing.

Had he lived, I do wonder if his opposition, compared to Catherine, who, familiarity or not, no doubt wanted to benefit from the connection, would've provoked a certain marital discord.

'Rhys had been attainted at the time of his conviction, meaning that the Crown could seize his goods and property, but his Act of Attainder specifically and unusally made provisions for his widow, who was left with an annual income of about £196.

If Anne could not save Rhys, she worked hard to salvage his family's situation.'

Meaning she got Henry to surrender some of his ill-gotten gains solely to avoid her aunt's destitution, where plenty of other widows and orphans were left to fend for themselves.

Anne also got Catherine a new husband in old-timer Henry Daubeney, but they bloody hated each other and split up soon enough.

According to Eric Ives:

'Over the winter of 1535-6, Katherine Howard, Anne's aunt, was trying to secure a separation from her second husband, Henry, Lord Daubeney. She told Cromwell that the only assistance she was receiving was from the Queen herself, and this despite the strenuous efforts which were being made to destroy her standing with Anne.

The help may have been very practical indeed; Lord Daubeney, who was certainly pleading financial hardship at one stage, reached an amicable agreement with his wife after Anne's father had made available £400.'

Even though this post about Catherine insists neither Anne nor Norfolk gave a toss about her personal woes, from the looks a things Anne was trying to solve this problem too.

'I have none to do me help except the Queen, to whom I am much bound, and with whom much effort is made to draw her favour from me.

My lord my husband has paid well to make friends against me, but I trust that the truth of what I suffer will be known...'

One wonders how all these paid agitators ended up gathered 'round Anne, nagging or distracting her from Catherine's cause, but evidently she wasn't put off.

Plus, according to that last link, Catherine never learnt her lesson and took part in the Pilgrimage of Grace an' all, raising 3,000 men against Henry!

By the sounds of it, this isn't a sudden burst of furious piety at work, rather there's almost an absence of religion in Catherine's life.

The obvious explanation would be yet again wreaking vengeance in Rhys's memory, and that's evident given her long-standing vendetta against his disloyal servants.

But would it be too much to think she was motivated to a certain extent by the death of her niece and nephew, being 'much bound' to the former?

And as she avoided all punishment, the remaining Howards (i.e. Norfolk) had to have covered up for her.

William Howard, 1st Baron Howard of Effingham

In 1529 there was much scrapping over the wardship of the Broughton sisters.

Wolsey ended up with the younger, Katherine, but upon his fall it seems Anne got the girl transferred to the care of Agnes Tilney, who then married her to William, so Anne was responsible for his first marriage.

(Not that it prevented Katherine Broughton from acting, as Ives puts it, as 'ringleader', in a demo for Mary six years later, and getting herself locked up in the Tower as a result, but there you go.)

Given the amount of important roles he enjoyed during Anne's queenship, all whilst barely out of his teens, she must have liked him:

• 1531: Ambassador to Scotland.

• 1532: Travelled to Calais with Anne to meet Francis.

• 1533: Served as Earl Marshal during Anne's coronation, in place of Norfolk.

• 1533: Held the canopy at Elizabeth's christening.

• 1535: Visited Scotland to award the Order of the Garter to James.

• 1536: Went again to Scotland to arrange a meeting between Henry and James.

Besides, Chapuys said of him:

'People are astonished at the despatch of so stupid and indiscreet a man.'

So he had to be Anne's friend.

Once he hears of her arrest, William curses it as 'heavy news', demanding to know the truth from Cromwell and resenting all the Scottish clergy as 'capital enemies' for rejoicing in her fall.

Mainly I'm mentioning him to discuss his own character, and where his evident loyalty to other family might give us a further suggestion of his relationship to Anne, and how he kept to that sense of honour even when it led him into dangerous territory.

Consider, for example, how he named his son Charles after his brother, and called his daughter Douglas in honour Margaret Douglas, Charles's wife, thus commemorating their doomed romance.

You'd also be surprised how often he turns up in Young and Damned and Fair, as he appears to have been Katherine's closest uncle, for all that she's usually connected to Norfolk.

Indeed, so deep was he in it Agnes had to be advised not to warn him off coming home, meaning he arrived from France and found himself immediately clapped in the Tower, whereupon he craftily claimed all his best plate was washed overboard so Henry couldn't get at it, which worked.

Later, his connection with Henry Howard ensured he missed out on being Admiral, and when he did get it, Mary took it off him to punish his partiality to Elizabeth.

There's a section here detailing his bond with Elizabeth, where he's credited with saving her life, if you ignore the obvious errors:

I especially like the idea everyone feared William would kidnap Philip!

However, there's a very odd paragraph in his son's Wiki page:

'In 1552, he was sent to France to become well-educated in the French language, but was soon brought back to England at the request of his father because of questionable or unexpected treatment.'

Am I mad or does this imply Charles Howard endured sexual abuse in his teens?

Were it only poor lodgings or sub-standard teaching, he could've moved elsewhere.

Were it excessive beating, you'd expect it to be made plain, not using all this cagey, obfuscating language.

But the thought did lead me to ponder their father-son bond, where Charles, whatever shame he suffered, knew he was loved enough that writing to his father would make it stop.

And William, reading it, rescued him immediately, proving the boy right.

This is a mere fancy of mine, but when it's just after Elizabeth's ordeal, whom he obviously cared so much about, and knowing she could easily have died like Katherine, which happened in part because he never stopped Dereham, one wonders if his moral failing then pushed him to protect Charles and Elizabeth later.

Thomas Howard, 1st Viscount Howard of Bindon

I'm hard-pressed to unearth much information on this lad, but everyone leaves him out so I won't.

There's gotta be some reason Elizabeth ennobled him, and so early on (in 1559) before he'd had the chance to serve her.

It can't just be she looked round the court, noticed he was the last of Norfolk's children, and awarded him for that.

I wish we knew more about Elizabeth's childhood, as in who she met and associated with at court, because you can be certain she met the Howards then.

I also want to add a little about his eldest son, the 2nd Viscount, who was...odd, to say the least:

• Being a pirate;

• Dressing as a tramp;

• Beating everyone including his wife.

This gave me the the idea that perhaps his and Norfolk's reputation had somehow been rolled up together over the centuries, where this Henry Howard, although unknown today, was probably infamous in his time, and maybe his behaviour in a sense lended credibility to the accusations of spousal abuse against Norfolk, where people felt Henry 'got it from somewhere'.

When Elizabeth learnt what he was up to, she sent Hercules Meautys (what a name) to rescue his sister, and took Frances in, with her husband dubbing her 'a filthy and porky whore', which was rich coming from him.

And his other son, the 3rd Viscount, killed his own father-in-law and had a long-running feud with Walter Raleigh.

He also spent years trying to have his brother's granddaughter Ambrosia declared a bastard to grab all her land, so Elizabeth locked him up!

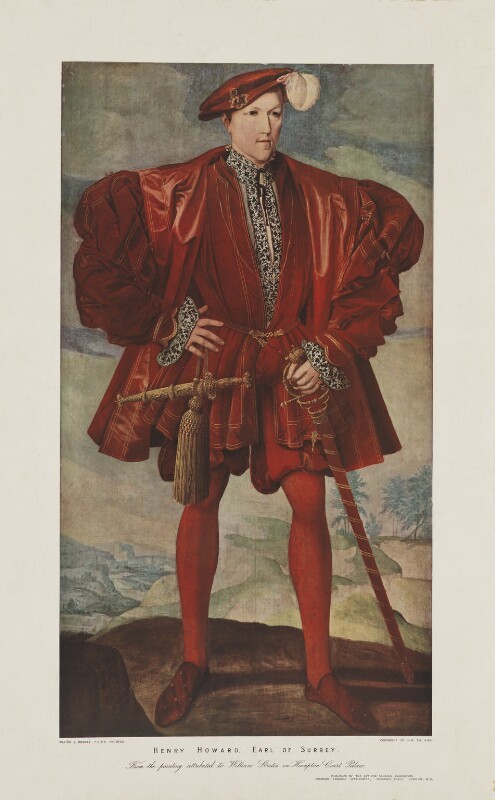

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey

Anne found Surrey a wife and took him with her to France, where he and FitzRoy remained as honoured guests until the next autumn.

He was then obliged to serve as Earl Marshal as Anne and George were sentenced to death.

Four years later, according to Gareth Russell, Surrey not only watched Cromwell's execution, but gloated about it afterwards:

'Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, stood at the forefront of the crowd and watched the scene without pity. He was missing his cousin's wedding to be here to see his family's bête noire finished off.

Later that day, he could not conceal his good mood. It felt to him like a settling of scores:

"Now is the false churl dead, so ambitious of others' blood."'

What does this mean?

Who's blood has Cromwell lusted after?

Who did he kill four years ago?

Surrey can't be referring to himself when Cromwell had actually protected him from punishment not long before, which in itself suggests a few interesting things:

• Cromwell was not yet aware of just how much the Howards despised him, as in, up til then his relationship with them was at least civil, cordial even, so the old line about Norfolk begrudging the 'new men' just because they're new men doesn't quite wash.

• This would've the perfect opportunity to bring down a mighty rival, but instead Cromwell felt bizarrely generous and intervened on Surrey's behalf, meaning he saw no harm in preserving the family, and instead thought it useful to get them on side.

• Why does he feel the need to favour the family?

Has he done something to antagonise them?

• The Howards are collectively putting on an Oscar-worthy acting routine of feigned friendliness, or at least indifference to said actions, so Cromwell, whilst he might suspect he's given slight offence, assumes it'll soon be forgotten if he pats them on the head here and there.

• Except whatever Cromwell did, saving Surrey wasn't enough to warrant forgiveness.

And let's examine this quote in detail:

Surrey is at 'the forefront' of spectators, keen to behold Cromwell dying in all its gory brutality, besides opting to watch such a horrendous deed over attending Katherine's wedding.

Instead of a happy celebration of his family's success, something he could've easily enjoyed in the knowledge of Cromwell being dealt with out of the way, he insisted on serving as a witness, as if it wouldn't be over until he'd seen it done, almost to be sure that it had.

For this would 'settle the score', shedding his blood in payback for... what exactly?

Thetford Priory?

Is that all?

Or for the blood Cromwell himself so coveted?

And even the sight of such suffering left Surrey unmoved, ridiculing the dead man not only as a 'churl', but a 'false' one.

False to whom?

'False' as in affecting loyalty to his Queen whilst working to bring her down?

Because is that extreme level of hatred really just supposed to be nothing deeper than empty class prejudice?

Usually, Cromwell's fractious history with the Howards is portrayed as Norfolk's one-man defamation campaign of all-encompassing lordly outrage verging on eye-popping insanity, except Surrey clearly loathed him too.

Perhaps from that we can conclude that Cromwell had become unpopular with the whole family, hence the 'bete noir' reference above.

When Surrey's resentment is remembered, it's conveniently boxed up and filed away as the same-old 'snobbery' of his father, which a very neat, uncomplicated excuse that prevents us looking into it properly.

I daresay Surrey was proud and class-conscious, but wouldn't everyone be like that, to a greater or lesser extent?

Why then is this 'haughtiness' only ever attributed to characters we're supposed to dislike, namely Anne, Norfolk, and occasionally George and Surrey, with the 'good' people somehow immune to such 'base' emotions?

Indeed, I'm starting to wonder how much real evidence there is for this common supposition of arrogance.

As if Surrey's known at all, it's for the manner of his death, namely he 'got himself killed' by 'stupidly' quartering the royal arms with his own, which, whilst a gross oversimplification, nevertheless defines him, where history views his character through this lens and reads his entire life backwards, as if there's no explanation for his behaviour other than he was just born to be a cocksure moron.

It plays upon modern bigotry against aristocrats, where they're all stuck-up, slow-witted inbreds fixated with the pecking order and archiac symbolism, keeping the honest worker down to prove they're better than everyone else, which is a laugh because they're all REALLY shallow, superfluous chuckleheads and deserve what they get.

Since the idea Surrey died for something so 'silly' as what badge went where slots so well into the stereotype, then it's cheapened his reputation overall.

Rather than being highly esteemed as a pioneer of English literature and the forerunner of Shakespeare, he's treated as nothing but a hot-headed toff tripped up by his own idiotic pretensions, with an end offered as a 'fitting' denouement, almost a lesson in morality; about where not 'knowing your place' or 'getting ideas above your station' leads... after vilifying Surrey and Norfolk for apparently demanding people know their place and not get ideas above their station.

Something hypocritical there.

There's also a reflexive judgementalism within this fandom and the lower end of publishing (i.e. novels and pop. history) where it's assumed if Anne or any of her family are executed, then even if they're technically innocent, they must've deserved it really, else 'the universe' wouldn't let it happen.

Therefore, known evidence is read with the most bad-faith interpretation, with any declared slip leapt upon and blown out of proportion, solely to prove their own bias correct.

You're right to think that, you are.

Hating them makes you A Good Person.

Again, this ONLY applies to Anne and her supporters, not her enemies.

No, no. They were martyrs to the Cause.

But I wouldn't say Surrey's usage of royal arms spoke to any pathological sense of superiority, certainly not to the extent it should define his memory.

Heraldry and ancestry is the lifeblood of nobility: everyone he knew fought for whatever their birth and court careers entitled them, so why shouldn't he?

Look at his sister protesting again and again and again for her rights as FitzRoy's widow: does this make her a 'snob' because she never gave up fighting?

In fact, dubbing Cromwell a 'churl' doesn't mean too much either.

The average person objects to someone because they're a thief, cheat, liar, etc. but calling them as much is a toothless insult, as they'd require a sense of honour to feel the sting.

And if they had that, they would've have committed the offence it in the first place.

So, you pick on something they probably are sensitive about, such as status or physical appearance, to get your own back.

Calling Henry VIII, for example, a fat bastard, doesn't mean you oppose him for having a weight problem, or that you dislike fat men generally.

It's that you're hitting 'below the belt' to inflict the worst punishment you can.

Oh yeah, it's petty, but the aggrieved often are.

Surrey's real crime, if we deem it one, was apparently rash language of what vengeance he'd wreak on his foes once the King was gone, meaning the Seymours.

So is it mere coincidence that the main targets of this infamous 'snobbery' are those who caused or benefited from Anne's fall?

Are we to believe his only complaint, right down to twice vetoing Mary Howard's marriage, is nothing better than looking down his nose at humble Seymour origins, for they've done nothing whatsoever to draw his ire?

For all the time I've been reading history, the way the court of 1536 splits between the Boleyns and those pushing Jane Seymour, and then, once the Boleyns are wiped out, it greatest rivalry becomes Howard versus Seymour, one lasting for the remainder of Henry's reign, has always struck me as both telling and appropriate.

The idea the Howards took over hating the Seymours because of their slain family is to me to most obvious explanation; the driving force pushing the enmity beyond a decade, and blaming it all on snooty la-di-da attitudes baffles me.

It's so pat and offhand, as if it was thrown into historical research centuries ago and never questioned, passed down to us as unassailable received wisdom, rendered true from repetition, as no one likes Surrey or Norfolk enough to bother reassessing their motivations.

But could such prolonged open hostility run on no greater impulse than keeping the gentry in check?

Is THAT all?

And do note how leading this narrative is, where, if we accept the Howards despised the Seymours as upstarts, then the fault for all bad blood is immediately shoved onto them and them alone, when those poor Seymour lads, rosy-cheeked and pure of heart, are just doing their best in life, working hard and loving everyone.

But oh! Those nasty Howards bullies are So Mean!

Not once is it reversed, proposing that the Seymours envied the Howards' breeding and birth, vowing to bring them down out of spite.

Instead they're absolved of all guilt in the conflict and justified in everything they do as a self-defence measure, even when they brought about Surrey's death and tried it on ten years previously.

So why on earth should he like them?

How I wish this painting still existed.

Starkey describes Henry Howard thus:

'Surrey inherited all Buckingham's grand pride in blood and aristocracy, and all his determination that noblemen should once more come into their own.

Perhaps it was from his mother's side too that he got his most dangerous trait: a rashness and a violence that bordered on madness.

Add to all this an intelligence that was both penetrating and fast and the result was one of the most remarkable men of the age.'

And yet I don't know of any aggressive outbursts prior to 1536, being then known for 'soberness and good learning'.

We tend to class poets of later eras as on the sensitive side, so far from being 'always like that', it may well be that the deaths of George, Anne, FitzRoy and putting down the Pilgrimage of Grace knocked him off the rails, a process then driven beyond all remedy by watching Katherine die and the suicidal shame he endured over his military failures.

Although I do like the sound of him as the hero of High Fantasy.

Whilst I'm here, let's look at this very awkward scenario of Surrey attending the triple Neville wedding, being the children of his mother's intended and her sister.

Considering how desperate so many are to clear Henry VIII of Anne's death, protesting how he Genuinely Believed and that makes it alright then, he's cheerful enough fannying about as a Turk less than two months later.

Finally, writing this I read several of Surrey's poems, and must include this truly endearing piece commemorating his wife's love for him:

Such a poet, and still no one credits him with any tender emotions.

Anyway, don't mind me but I've hit the picture limit.

I'm not sure when Part Two will be done, but I'll let you know, come the time.

#Henry Howard#Catherine Howard Countess of Bridgewater#William Howard#Thomas Howard 1st Viscount Howard of Bindon#Anne Boleyn#Elizabeth I#Henry Howard 2nd Viscount Howard of Bindon#Thomas Howard 3rd Viscount Howard of Bindon#Frances Meautys#Rhys ap Gruffyd#Thomas Cromwell#Young and Damned and Fair#Gareth Russell#The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn#Eric Ives#David Starkey#Quotes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

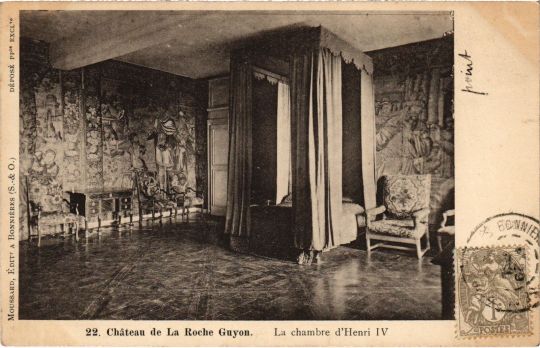

Henri IV's room in the Château de La Roche-Guyon, Vexin region of France

French vintage postcard

#historic#chteau#guyon#photo#briefkaart#vintage#region#sepia#iv#photography#carte postale#the château de la roche-guyon#postcard#henri iv's#postkarte#henri#france#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#french#old#ephemera#de#postkaart#vexin#la#room#roche

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

How come Catherine de Medici loved Henri so much even though he (cheated and) significantly favoured Diane de portiers, and also slighted her at time like with the castle she wanted and he didn’t give it to her?

It is the accepted narrative that Catherine de’ Medici was obsessively in love with her husband King Henri II, despite the fact that--or perhaps because, depending on who you’re reading--he was clearly in love with Diane de Poitiers. It’s not terribly different from the stories told about Juana of Castile, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella and heiress to Castile. She was married to Philip IV Hapsburg, duke of Burgundy, who was reportedly both very handsome and a womanizer. The stories claim that Juana was so wildly in love with her husband that, after he died from illness, she carried his corpse with him wherever she travelled, and renounced the throne of Castile out of grief and madness. In fact, she is popularly known as Juana la Loca or Juana the Mad.

This is almost certainly propaganda spread both during Juana’s lifetime and after her death. Whatever her feelings were for her husband, he repaid them by conspiring with her father King Ferdinand to dethrone Juana in favour of her young son Charles so they could collectively rule on his behalf. Similarly, much of what we know of Catherine de’ Medici’s feelings for her unfaithful husband comes from the same sources that tell us she was a poisoner and the centre of webs of intrigue and murder.

We know Catherine never remarried or showed any interest in remarrying after Henri’s shocking death in 1559, but there are plenty of reasons for that. She and Henri were married when both of them were 14 years old, and for the first ten years, Catherine was blamed for the couple’s inabiilty to conceive any children. Henri took multiple mistresses at first, but finally settled on Diane de Poitiers, who he treated with far greater respect and affection than his wife. In January 1544, after nearly eleven years of marriage, Catherine finally gave birth to the long-awaited heir to the throne. After him, she had nine more children who survived infancy, and nearly died giving birth to two more.

We also know that she adopted the image of a broken lance and the motto “lacrymae hinc, hinc dolor“ (”from this come my sorrow and tears”) after his death in a jousting accident. But it’s worth remembering that her position as Regent of France on behalf of three of her sons over the next half-century at least partly depended on her keeping up an obvious connection to the previous Valois king. How much of Catherine’s grief was real and how much was politically motivated, we honestly can’t say. But she was an extremely clever woman who spent years flying under the radar before ending up all but ruling France, so she was certainly adept at playing dangerous games.

#history#catherine de' medici#16th century#france#henri ii#diane de poitiers#juana of castile#philip iv hapsburg

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henri IV with his Mistress by Louis-Nicolas Lemasle

#henri iv#art#louis nicolas lemasle#henry iv#king#france#french#henry of navarre#captured#flags#flag#standard#battle of coutras#troubadour#europe#european#history#diane d'andoins#countess of gramont#comtesse de gramont#architecture#countess de gramount#henry iii#navarre#henri iii#french religious wars#royal#huguenots#huguenot#royalty

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry IV of France | Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully

Henri 4 (2010)

La Guerre des trônes, la véritable histoire de l'Europe: S3, Ep1 (2019)

Vive Henri IV, vive l'amour! (1961)

La caméra explore le temps: Qui a tué Henri IV ? ou L'Énigme Ravaillac

Ce jour-là, tout a changé: L'Assassinat d'Henri IV (2009)

#henry iv of france#henri iv#henry of navarre#henri de bourbon#duc de sully#duke of sully#maximilien de bethune#sorry for the quality#making gifs is still so difficult to me#but i really love these guys#sadly there is not much content about them#history of france#french history

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Loyal brothers

The Capetian kings found their brothers no more difficult than their sons. The exceptions were the brothers of Henri I, Robert and Eudes, but thereafter the younger Capetians developed a tradition of loyalty to their elders. Robert of Dreux, the brother of Louis VII, who was the focus of a feudal revolt in 1149, was only a partial exception, for at that date the king was still in the East, and the real object of the hostility was the regent Suger. By contrast, Hugh of Vermandois was described by contemporaries as the coadjutor of his brother, Philip I. St Louis's brothers, Robert of Artois, Alphonse of Poitiers, and Charles of Anjou, never caused him any difficulties, and the same can be said of Peter of Alençon and Robert of Clermont in the reign of their brother Philip III. Even the disturbing Charles of Valois, with his designs on the crowns of Aragon and Constantinople, was always a faithful servant to his brother Philip the Fair, and to the latter's sons. The declaration which he made when on the point of invading Italy in the service of the Pope is revealing:

"As we propose to go to the aid of the Church of Rome and of our dear lord, the mighty prince Charles, by the grace of God King of Sicily, be it known to all men that, as soon as the necessities of the same Church and King shall be, with God's help, in such state that we may with safety leave them, we shall then return to our most dear lord and brother Philip, by the grace of God King of France, should he have need of us. And we promise loyally and in all good faith that we shall not undertake any expedition to Constantinople, unless it be at the desire and with the advice of our dear lord and brother. And should it happen that our dear lord and brother should go to war, or that he should have need of us for the service of his kingdom, we promise that we shall came to him, at his command, as speedily as may be possible, and in all fitting state, to do his will. In witness of which we have given these letters under our seal. Written at Saint-Ouen lès Saint-Denis, in the year of Grace one thousand and three hundred, on the Wednesday after Candlemas."

This absence of such sombre family tragedies as Shakespeare immortalised had a real importance. In a society always prone to anarchy the monarchy stood for a principle of order, even whilst its material and moral resources were still only slowly developing. Respectability and order in the royal family were prerequisites, if the dynasty was to establish itself securely.

Robert Fawtier - The Capetian Kings of France

#xii#xiii#xiv#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#henri i#robert i de bourgogne#louis vii#robert i de dreux#abbé suger#philippe i#hugues de vermandois#louis ix#robert i d'artois#alphonse de poitiers#charles i d'anjou#philippe iii#pierre d'alençon#robert de clermont#philippe iv#charles de valois

7 notes

·

View notes