#hiru is always on that grind

Photo

Evening the Score, page 319

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appendix: the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Part 26: (1591) Intercalated First Month, Third Day, Midday.

86) The Same, Midday of the Third Day¹.

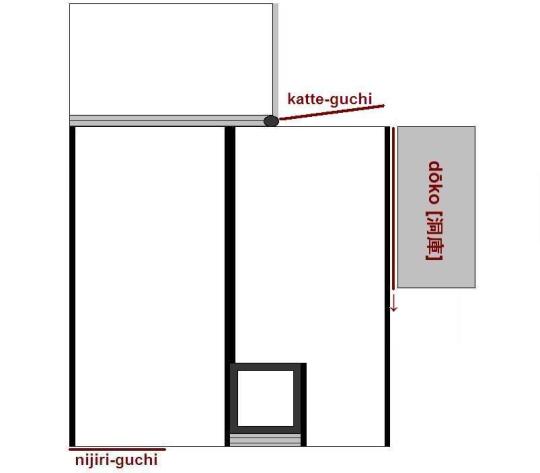

○ Two-mat room².

○ Itami-ya ・ Jōmu [伊丹屋・紹無]³, Kome-ya ・ Yojūrō [米屋・與十郎]⁴, the same ・ Dōtsū [同・道通]⁵, Mozu-ya ・ Sōan [もずや・宗安]⁶.

○ Chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小なつめ]⁷;

◦ Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ]⁸;

◦ Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡]⁹.

○ After tea was finished¹⁰:

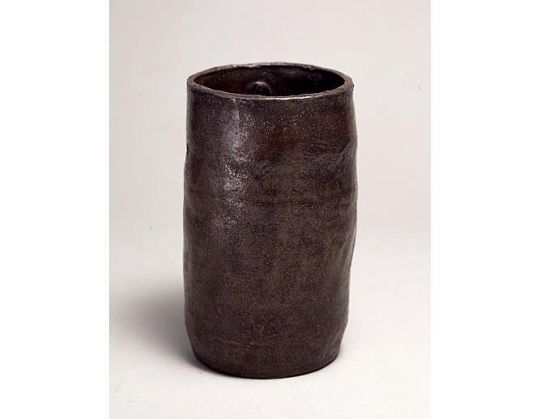

◦ Kōrai-zutsu [かうらい筒], [with] plum blossoms [arranged] in it¹¹.

○ The feast was served in the large room¹².

○ Ko-tori senba-iri [小鳥せんば入]¹³;

◦ konowata [このわた]¹⁴;

◦ fukuto-jiru [ふくと汁]¹⁵;

◦ meshi [めし]¹⁶.

○ Kashi [菓子]:

◦ fu-no-yaki [ふのやき]¹⁷;

◦ yaki-mochi [やき餅]¹⁸.

_________________________

¹Onaji mikka no hiru [同三日之晝].

Onaji [同] refers to the month -- it is still the Intercalated First Month of Tenshō 19.

²Nijō shiki [二疊敷].

³Itami-ya ・ Jōmu [伊丹屋・紹無].

Itami-ya Jōmu [伊丹屋・紹無], who was also known as Shin-ho-an Jōmu [心甫庵 紹無], was a chajin from Sakai.

The Itami-ya [伊丹屋] house later became prominent after the rise of kabuki [歌舞伎] in the Edo period -- though it is possible that they were already associated with the performing arts (perhaps Nō [能]*, in which Hideyoshi also had a great interest) during this period.

___________

*Since the Ashikaga period, Nō [能] interpretations had frequently been more energetic than what came to be preferred later (in the Edo period). In a very real sense, Kabuki arose out of this more active form of the performance art, while leaving the classical (and sedate) themes to the -- by then -- archaic Nō.

That other famed nō actor of this period, Miyaō Saburō Sannyū [宮王三郎三入; ? ~ 1582] -- who fathered the line that became the "officially recognized" Sen family not long before Hideyoshi's own death -- was also an intimate of Hideyoshi (and, indeed, it was Sannyū's self-sacrifice at the battle of Yamazaki, where he literally intercepeted a bullet that had been aimed at Hideyoshi, which earned him and his son the undying thanks that permitted Hideyoshi to reinstate the Sen family name, under Sannyū's son Shōan, several years after Rikyū's death in ignominy).

⁴Kome-ya ・ Yojūrō [米屋・與十郎].

A wealthy machi-shū based in Kyōto* (the Kome-ya firm was involved in the rice trade – which apparently included the exchange of the samurai’s rice stipends for cash), the details of whose life have been lost.

Yojūrō was mentioned earlier in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, as a guest at the ato-mi that followed Rikyū's morning chakai on the 11th day of the Twelfth Month of Tenshō 18.

___________

*Apparently in the Shimo-gyō [下京] part of the city near Shichi-jō [七条] (Seventh Avenue).

The block where the firm was located is still known as Komeya-machi [米屋町].

⁵Onaji ・ Dōtsū [同・道通].

Onaji [同] here refers to the yagō [屋號]: in other words, Dōtsū was also a member of the Kome-ya house -- perhaps Yojūrō's brother or cousin; but nothing is actually known about him*.

___________

*There was a man from a military family who lived during this period named Inaba Michitō [稲葉道通; 1570 ~ 1608] (Michitō [道通] is another way to read the name Dōtsū [道通]). He was a daimyō and nobleman (junior grade of the Fifth Rank), who served as an imperial chamberlain of the left division (sakon no kurōdo [左近蔵人]). But given the person's position during the chakai (third guest), and the status of his fellow guests (all machi-shū), it does not seem that this individual can be identified with Michitō.

⁶Mozu-ya ・ Sōan [もずや・宗安].

Mozu-ya Sōan [萬代屋・宗安; ? ~ 1594] was one of Rikyū’s lifelong friends (they were perhaps of a similar age, though the details of Sōan's early life seem to have been lost), as well as the husband of one of Rikyū’s daughters. He was also numbered among the tea masters from Sakai who was employed in an official capacity in the tea department at Juraku-tei, and enjoyed a good reputation in chanoyu among his contemporaries.

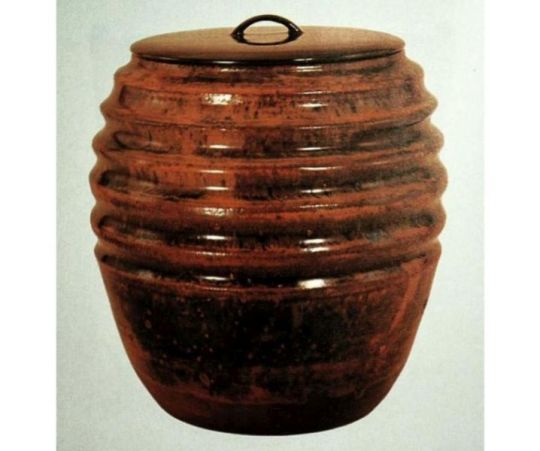

⁷Chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小なつめ].

The use of this tea container “says” that the tea served during this chakai was ground specifically for this gathering* (rather than being left over from the morning chakai).

The natsume would have been tied in a shifuku.

Rikyū appears to have abbreviated his record of this chakai†, since other utensils would have been needed to serve tea to his guests. Surely, the rest of the tori-awase would have been the same things that he used at the morning gathering that preceded this one:

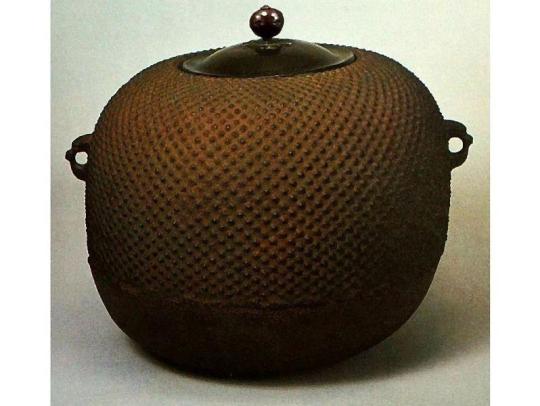

◦ arare-gama [霰釜];

◦ Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水指];

◦ Ko-mamori chawan [木守茶碗];

◦ ori-tame [折撓];

◦ take-wa [竹輪];

◦ hirai Shigaraki mizu-koboshi [平い信樂水飜]‡.

__________

*In other words, Rikyū ground the tea after the first chakai was over, the ko-natsume indicating that this was all the tea he was able to grind in the time between the end of the morning gathering and the end of the naka-dachi for the midday gathering.

†Suggesting that he was pressed for time. Perhaps this group of machi-shū had some reason to confer with Rikyū (certainly as the date for Hideyoshi’s upcoming invasion of the continent approached, the business community -- which provided much of the financing for the venture -- would have been concerned about updates) would have, and asked to meet him on the spur of the moment. Rikyū would have been one of the main intermediaries between the Sakai- and Kyōto-based machi-shū and Hideyoshi’s court at Juraku-tei.

‡It is also possible that he used a mentsū [面桶] as the koboshi, in the interests of purity.

⁸Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ].

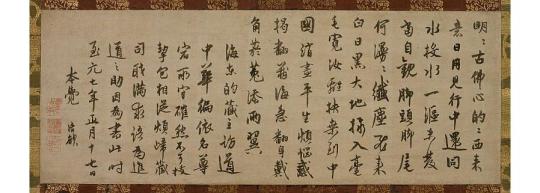

⁹Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡].

¹⁰Cha sugite [茶すぎて].

Cha sugite [茶過ぎて] means “after the [service of] tea had been concluded.”

Precisely why Rikyū may have opted to wait to arrange the flowers until a point near the end of the chakai is not clear. Perhaps the sentence is a mistake? (In other words, perhaps Rikyū intended to indicate that the hanaire was added to the scroll -- suspended on the outer-wall-side pillar, and either miswrote or his words were not transcribed accurately. See footnote 12, below, for another indication that there may have been problems with this entry.)

¹¹Kōrai-zutsu ・ baika ireru [かうらい筒・梅花入].

The Kōrai-zutsu [高麗筒] was a kake-hanaire [掛け花入]. It seems that Rikyū may have suspended it on the pillar, while leaving the scroll hanging as it was.

Contrary to modern practices, if a kake-hanaire was not suspended on the wall at the back of the toko, it was hung on the minor pillar in the outer wall side of the toko (whether hung on the pillar, or on the bokuseki-mado as Furuta Sōshitsu did*, the idea was to suggest that the flower was growing outside in the garden, and simply leaning into the room: the flower always should arch toward the temae-za, regardless of where it is found).

Hanging the hanaire on the toko-bashira is a mistaken interpretation of the purpose of the hook that was sometimes (usually temporarily) nailed into that pillar at night gatherings: this hook was used to hang an oil lamp in the old days, the purpose of which was to illuminate the signature and name-seal(s) on the kake-mono (according to the classical teachings, the toko-bashira should always be located on the side of the scroll where the signature/seals appear). This hook was never used for the flower vase; and, indeed, it was usually removed completely after the gathering (since its position depended on the scroll -- if the host hung a different scroll at a subsequent night gathering, the location of the flame would have to be adjusted higher or lower accordingly). Unfortunately, the machi-shū did not understand this point, and, fearful of doing something wrong, they left the hook where the previous tea master had nailed it; and then conflated this hook with the other temporary hook that was sometimes nailed into the minor pillar (for the hanaire). The result is that, if the flowers are hung on the toko-bashira, it is impossible for them to have the correct orientation (leaning toward the temae-za).

___________

*Rikyū’s bokuseki-mado was usually located outside of the toko, behind the shōkyaku’s seat, making it impossible for him to hang the hanaire there. Suspending it on the minor pillar was equivalent to Oribe’s use of the bokuseki-mado for this purpose.

¹²Furu-mai hiroma ni te [振舞廣間にて].

Furu-mai [振舞] means a “feast” (i.e., a rather elaborate meal, served with some ceremony).

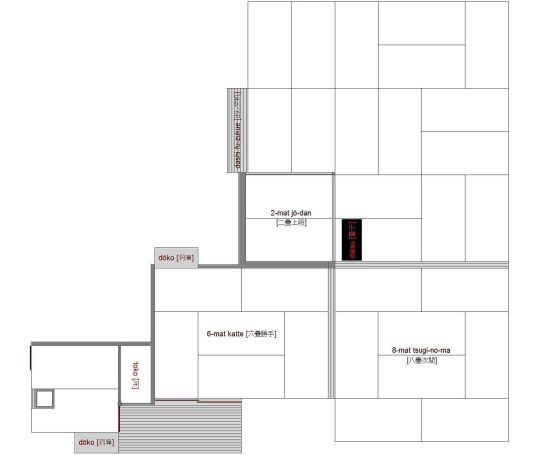

“In the large room” refers to Rikyū's 18-mat “Colored Shoin” -- which adjoined the 2-mat room through the 6-mat katte and 8-mat tsugi-no-ma [次の間] (as shown in the above sketch.

This statement, the language of which is rather odd (and atypical of Rikyū’s known usages) is not found in the Hisada family’s version of the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki. Since it was not usual for people making copies to add anything to the text, this suggests that this section of Rikyū‘s manuscript may have been in a poor state of preservation, or else Rikyū wrote something and then scratched it out (and the statement furu-mai hiroma ni te was someone’s guess at what had been written). Perhaps Rikyū was writing this entry quickly and his dyslexia was interfering with his concentration.

¹³Ko-tori senba-iri [小鳥せんば入].

Ko-tori [小鳥] is a general name for the sparrows and small finches that were commonly taken by the hawkers during the winter months.

Senba-iri [船場煎り] is a style of cooking that was popularized by the food stalls that lined the wharves of Sakai: small birds (fowl that, because of their size, can be cooked relatively quickly) prepared for roasting were tied to skewers and suspended above a wooden fire while being basted with a mixture of sesame oil, soy sauce, sake, mirin, and crushed garlic.

¹⁴Konowata [このわた].

The salted entrails (primarily the gonads and their contents) of the sea cucumber -- a relative of the starfish and sea urchins.

¹⁵Fukuto-jiru [ふくと汁].

A clear soup (almost a stew) made from the fugu [河豚] -- in English, puffer fish (also known as the blowfish, or globefish). The prepared fish were chopped into pieces and boiled with pieces of daikon and crushed garlic. Freshly chopped leeks were sprinkled on top of the soup before it was served.

Modern-day fugu chiri-nabe [河豚ちり鍋] (also simply called fugu chiri [河豚ちり]) is very similar to what Rikyū here calls fukuto-jiru [河豚頭汁].

¹⁶Meshi [めし].

Steamed rice.

¹⁷Fu-no-yaki [ふのやき].

Rikyū’s wheat-flour crêpes, spread with sweet white miso (or “miso-an” [味噌餡] -- white bean-paste flavored and sweetened with white miso rather than sugar or honey) before being folded into bite-sized pieces.

¹⁸Yaki-mochi [やき餅].

Mochi [餅] (a dried paste made by beating sticky-rice in a wooden morter until smooth, and the forming this into cakes that are dried; the cakes are sliced into small pieces before being served) that has been toasted on bamboo skewers over a charcoal fire (to soften it). While this dish was commonly wrapped in nori [海苔] (paper-thin sheets of dried laver) during the Edo period, it seems that during Rikyū’s period it was simply served on the skewer (to facilitate handling of the potentially sticky piece of mochi).

It is important to note that the Hisada-bon has yaki-guri [やきくり] here, rather than yaki-mochi., which suggests that the entry was written in haste, and perhaps carelessly. Yaki-guri [焼栗] is roasted chestnuts -- another of the kashi frequently offered to his guests by Rikyū, and the one most often paired with his fu-no-yaki [麩の焼].

0 notes

Text

Appendix: the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Part 4: (1590) Ninth Month, Thirteenth Day, Midday.

6) [The Same; Midday [同・晝]¹.]

○ Ue-sama [上樣]²; [Yaku-in [藥院]³].

○ Two-mat room⁴.

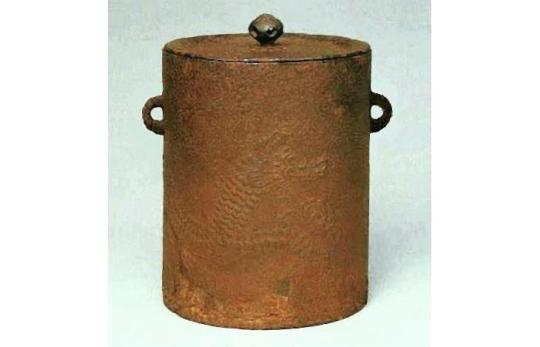

○ Unryū-gama [雲龍釜]⁵;

◦ wake-mono mizusashi [はけ物水さし]⁶;

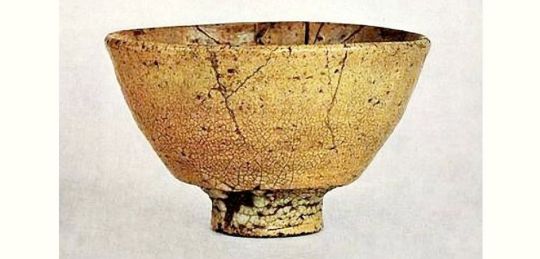

◦ Tsutsui no ido chawan [つついのいど茶碗]⁷;

◦ chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小ナツメ]⁸;

◦ ori-tame [をりため]⁹.

○ The Same; Midday [同・晝]¹⁰ -- in the Large Room [廣間にて]¹¹:

◦ kushi-awabi [くしあはび]¹²;

◦ o-yu-tsuke [御湯つけ]¹³.

○ In a [spouted] vessel¹⁴ [decorated] with gold [foil]¹⁵: yaki-miso [やきみそ]¹⁶;

◦ kō-no-mono [かうの物]¹⁷;

◦ mizu-ae [水あへ]¹⁸;

◦ atsume-shiru [あつめ汁]¹⁹.

○ Kashi [菓子]:

◦ senbei [せんべい]²⁰;

◦ usukawa [うすかは]²¹;

◦ koneri-gaki [こねりがき]²²;

◦ kan [かん]²³;

◦ fu [ふ]²⁴.

_________________________

¹Onaji・hiru [同・晝].

This statement, indicating the time when the gathering was held, was actually noted in the kaiki later, just before the menu for the kaiseki. This suggests that Rikyū entered this gathering in the kaiki in a state of some confusion.

In fact, it appears that the original gathering (for which the tori-awase was assembled) was moved from midday to morning (probably due to Hideyoshi’s personal request, perhaps only received early the same morning: this would account for the relative simplicity of the food offered during the first chakai, as well as for why only a single variety of koicha was ready at that time*). Then, because he liked the tea†, he asked Rikyū to allow him to try the second kind as well; and since grinding additional matcha would take time (a fact of which Hideyoshi would have been completely aware, and which he would have accepted as fitting), he said would like to return later in the day and try the other variety that was packed in the Hashi-date cha-tsubo. This is the best explanation for why Rikyū hosted a second gathering for Hideyoshi in his other room (at which he served the more elaborate kaiseki that had been planned for this special kuchi-kiri no chakai).

Since five of Hideyoshi's courtiers were received for an atomi no chakai following the morning session‡, it would have been impossible for Rikyū to serve them tea (even just usucha) in the 4.5-mat room while also attending to Hideyoshi in the 2-mat room and shoin. (And if, for example, his son Dōan had served the courtiers, Rikyū typically would have made a notation to that effect in the kaiki.)

Therefore, the most likely scenario is that (as suggested previously) after the morning gathering Hideyoshi retired to his own residence (to rest while the second variety of koicha was being ground), while Rikyū received the courtiers in the 4.5 mat room (during which time Dōan would have seen to the grinding of the new kind of matcha) -- and then, after their departure, readied the 2-mat room and shoin for Hideyoshi's imminent return.

When word was received of Hideyoshi's departure for Rikyū's residence, Rikyū would have concluded whatever he was doing and stationed himself in the 2-mat room, to wait for his guest. And, after performing the sumi-temae, he would have invited Hideyoshi into the shoin for the meal (where he would have eaten the kaiseki, accompanied by Yakuin Zen-sō), after which they would have returned to the 2-mat room for koicha (followed by usucha served from the tea remaining in the natsume).

Thus, this entire second chakai would have commenced when Hideyoshi returned, probably around the middle of the day.

This material (which was combined with the previous chakai) was discussed in the post entitled Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, Book 6 (Part 4): Rikyū’s Hyaku-kai Ki, (1590) Ninth Month, 13th Day, Morning; the Kuchi-kiri Chakai. The URL for that post is:

http://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/167440639703/riky%C5%AB-chanoyu-sho-book-6-part-4-riky%C5%ABs

(Please note that this is the same URL quoted in the previous post -- because the two chakai were conflated into one in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho.)

___________

*It was usually the case (and this practice dates back at least to the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa -- though since the form where up to three kinds of tea were served during a single temae was learned from Nōami, this suggests that the idea traced its origins back to chanoyu on the continent) -- and this remains the custom even today -- that the host serves both kinds of koicha at the kuchi-kiri no chaji, so the question remains as to why Rikyū had prepared only one of the varieties for this gathering. The simplest explanation -- since tea was ground in the early morning -- is that Hideyoshi suddenly moved the time of the chakai forward, from midday to the time of the mid-morning meal. (As mentioned above, this would also account for the rather homely kaiseki that Rikyū served during that gathering).

This also would account for the recess (during which Rikyū hosted the atomi for Hideyoshi’s courtiers, while his son oversaw the grinding of the second variety of tea in the mizuya).

Nevertheless, by serving the two kinds of tea at different chakai, Rikyū could insure that cross-contamination of the second koicha by traces of the first would not occur. And by waiting to grind the second variety of tea until after the first chakai was concluded, Rikyū could also be sure that the tea served at the midday gathering would be exactly as fresh as the first had been in its time, thus allowing a close comparison between the two.

†Cha-tsubo were generally filled with three kinds of tea: Hatsu-no-mukashi koicha [初の昔濃茶] and the corresponding Ato-no-mukashi koicha [後の昔濃茶] (from the same garden or gardens), the paper packets of which were surrounded by inferior-quality leaves (used as packing material, to prevent any dampness seeping into the jar from damaging the high-quality leaves) that could be used for usucha. The Hatsu-no-mukashi and Ato-no-mukashi leaves would have been of exactly the same quality. Thus Hideyoshi, enjoying the first, had probably said that he would like to taste the second, which resulted in the rather impromptu second gathering.

‡The intention would, in part, have been to use up the rest of the freshly ground matcha remaining from the first gathering, before it began to loose its flavor.

Whether Rikyū served both koicha and usucha, or only usucha, would have depended on the amount of tea that remained.

²Ue-sama [上樣].

Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

³Yaku-in [藥院].

In the majority of the manuscripts*, Hideyoshi appears to have attended this chakai alone. However, the Hisada family's version (which copy seems to have been made shortly after Rikyū's death) indicates that Yakuin Zen-sō also accompanied Hideyoshi to this second chakai -- which would have been appropriate (according to the customs of the day, where important persons were never left unattended†).

__________

*Which seem to be either second-generation copies, or copies made at the beginning of the Edo period (after Rikyū's original had begun to deteriorate).

†It was not always necessary to mention this fact, and the attendants (if not important individuals in their own right) were often not named in the kaiki -- though this does not mean that they were not present.

Especially when a meal was served, during which the host would be out of the room for potentially extended periods of time, it would have been extremely rude to leave an important guest sitting alone -- if only because he would have nobody to talk to (and nobody to help him if he suddenly needed something -- it being very bad manners to raise ones voice to call out to people in the next room for assistance).

Hideyoshi would have been seated on the 2-mat jō-dan [上段], while Zensō would have taken a seat at the foot of the jō-dan immediately below, perhaps in front of the dashi-fu-zukue [出し文机] (this would allow him to help serve Hideyoshi, by pouring the hot water for him and helping him in other ways, when Rikyū was absent).

⁴Nijō shiki [二疊敷].

The guests entered this room at the beginning of the sho-za, for the sumi-temae.

When Rikyū was done, he would have invited the guests to move into the shoin (by passing through the katte-guchi -- the host's entrance --, the 6-mat katte, and the 8-mat tsugi-no-ma).

⁵Unryū-gama [雲龍釜].

The details of the arrangement and use of the small unryū-gama in the ro are covered in footnote 17 in the post mentioned under footnote 1 (Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, Book 6 (Part 4): Rikyū’s Hyaku-kai Ki, (1590) Ninth Month, 13th Day, Morning; the Kuchi-kiri Chakai). The URL for which is:

http://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/167440639703/riky%C5%AB-chanoyu-sho-book-6-part-4-riky%C5%ABs

The kama was suspended over the ro on a bamboo ji-zai, using Rikyū‘s bronze kan [鐶] and tsuru [弦], which are shown above.

⁶Wake-mono mizusashi [はけ物水さし].

While the name was transcribed with the hiragana “ha” [は] (for the sound “wa”), specimens from the Hisada manuscript show that the word was actually written “〇け物水さし,” at least in that (early version of the) kaiki.

⁷Tsutsui no ido chawan [つついのいど茶碗].

This is the same chawan that is now known as the Tsutsu-i-zutsu [筒井筒]*. At the time of this chakai, the chawan had not yet been damaged (which was the provocation for the change in name).

The earlier name† refers to the daimyō‡ from whom Hideyoshi received this chawan.

__________

*The modified name derives from a kyōka [狂歌] (a comic verse) by Hosokawa Yūsai [細川幽斎, 1534 ~ 1610], who was present when the bowl was broken, who recited it in an effort to defuse Hideyoshi's anger over the damage to his chawan: tsutsu-i-zutsu izutsu ni wareshi ido-chawan, toga wo baware ni oi shike rashi na [筒井筒五つにわれし井戶茶碗とがをばわれに負ひしけらしな]: “the ‘Tsutsu-i-zutsu,’ an ido-chawan that has been broken into five pieces -- yet if I take the blame for [breaking] it on myself, doesn’t that mean that I’ll be the one who gets kicked?”

Though many modern commentators state that Yūsai's poem was derived from a verse in the Ise Monogarari [伊勢物語], in point of fact it was based on a more recent effort (by Fujiwara no Suetsune [藤原季経, 1131 ~ 1221], recited during the famous Roppyaku-ban Uta-awase [六百番歌合], “the Poetry Competition in Six Hundred Innings,” which was held around the year 1193): tsutsu-i-zutsu i-zutsu ni kakeshi-take yori mo sugi-nu ya kayō kokoro fukasa ha [筒井筒井筒にかけしたけよりも過ぎぬや通ふ心深さは]: “the enclosure around the well-curb: because of the banister one can not pass [to throw himself into the well]; [so] I am left to wander back and forth, lost in dark thoughts."

It was Suetsune's poem that can be better said to be related to the poem (ascribed to Ariwara no Narihira) found in episode 23 of the Ise Monogatari: tsutsu-i-tsuno i-zutsu ni kakeshi maro ga take sugi ni kerashi mo imo mi-zaruma ni [つゝゐつのゐづゝにかけしまろがたけすぎにけらしもいもみざるまに], which Helen C. McCullogh has rendered as “since I last saw you, it seems to have grown until I am the taller - my height, that we two measured against the curb of the well” in her 1963 translation of the Ise Monogatari.

†This chawan had originally belonged to Shukō. However, after several changes in ownership, it came into the possession of the samurai Tsutsui Junshō [筒井順昭, 1523 ~ 1550], a contemporary (and student of) Jōō.

‡Toyotomi Hideyoshi received this chawan from Junsho's son Tsutsui Junkei [筒井順慶, 1549 ~ 1584], who presented the bowl to Toyotomi Hideyoshi together with an apology for originally having sided with Akechi Mitsuhide.

⁸Chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小ナツメ].

This container held matcha that had been ground between the end of the first gathering and this (meaning that the amount of tea was limited). A ko-natsume was used because this would allow the tea to fill it completely (leaving no more empty space than necessary, so the flavoring elements would not volatilize and escape, thus keeping the tea as fresh as possible).

Though this is purely conjecture, since cha-tsubo were traditionally filled two kinds of koicha (hatsu no mukashi [初の昔], the tea picked during the first ten days of the harvest season; and ato no mukashi [後の昔], the tea picked during the last ten days of the season -- both teas being of the same grade), perhaps Rikyū served hatsu no mukashi during the morning gathering, and ato no mukashi during this present chakai. Since this seems to have been the first opportunity to taste the new tea, perhaps Rikyū and Hideyoshi did things this way so that both kinds of tea could be appreciated to their fullest, without any chance of the first contaminating the second.

⁹Ori-tame [をりため].

In addition, Rikyū would have used a take-wa [竹輪] as the futaoki, and a mentsū [面桶] as the mizu-koboshi.

These two were the things almost always used for these purposes in the small room, hence there was no reason for Rikyū to specify them in the kaiki.

¹⁰Onaji ・ hiru [同・晝].

As mentioned above (under footnote 1), this actually defines the time for the entire chakai, not just the kaiseki.

¹¹Hiroma ni te [同・晝 廣間にて].

The important point is that the meal was served in the hiroma (i.e., Rikyū's 18-mat Colored Shoin, with its 2-mat jō-dan), rather than in the 6-mat katte, as was usually done when entertaining more ordinary guests in his 2-mat room.

¹²Kushi-awabi [くしあはび].

Skewer-dried abalone that has been rehydrated by boiling it in broth. The flesh is sliced into bite-sized pieces before being served.

¹³O-yu-tsuke [御湯つけ].

This means adding hot water to rice, to make a sort of gruel.

The hot water was replaced with steeped tea in the Edo period, leading to what we now know as o-cha-tsuke today.

¹⁴Oke ni [桶に].

Perhaps a shallow metal nabe with a handle and a spout, in which soup was sometimes served.

It was brought out on a long tray, and would have been accompanied by a bowl of pickled vegetables (see footnote 17, below).

The miso-shiru was served in this container, along with a shallow ladle with which the yaki-tōfu and daikon was served

¹⁵Kane ni tamu [金にたむ].

This is an interlineal comment, referring to (and apparently describing) the nabe. According to the editors of the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集], this means that the nabe was decorated with gold foil (kinpaku [金箔]) -- perhaps gilded all-over, so that it resembled a serving pot made of gold.

¹⁶Yaki-miso [やきみそ].

This is miso-shiru containing a large piece of scorched momen-tōfu [木綿豆腐] and finely chopped daikon.

¹⁷Kō-no-mono [かうの物].

Vegetables pickled in brine for several days. The pickling gives them a crunch, which seems to have been much appreciated in Rikyū’s day.

¹⁸Mizu-ae [水あへ].

According to the commentary published in the Sadō Ko-ten Zenshu [茶道古典全集], mizu-ae [水和え] refers to a dish made of various kinds of dried foods (the commentary includes a list of various kinds of small fish, eel, squid, melons, mushrooms, and so forth -- though without any certainty of which of these Rikyū may have used for the mizu-ae dish served on this occasion) soaked in water, and then sliced and dressed with a mixture of iri-zake* and rice-vinegar.

__________

*Iri-zake [煎り酒] is (old) sake that has been boiled down with kelp, katsuo-bushi, and ume-boshi (pickled "plums" -- the fruit of the early-spring-flowering ume).

Iri-zake was a popular condiment in Rikyū's day (in addition to being used to flavor various dishes, it was also used as a dipping sauce), and allowed the host to make a use of sake that was no longer fit to be served as a beverage.

¹⁹Atsume-shiru [あつめ汁].

This means a soup made by boiling the various other things that had been served during the meal together in a clear broth (including the things used when making the mizu-ae, and the miso-shiru).

²⁰Senbei [せんべい].

Senbei [煎餅] are Japanese rice "crackers," originally inspired by the burned rice that forms on the bottom of the rice pot as it is cooking.

²¹Usukawa [うすかは].

Usukawa [薄皮] are a kind of manjū [饅頭] (a steamed kashi) with a very thin wheat-flour skin, filled with bean-paste. This was probably procured from a specialty shop.

²²Koneri-gaki [こねりがき].

Koneri-kake [木練柿] are persimmons that has ripened on the tree. They become extremely sweet and soft after the first frosts (though they are spoiled by the heavy frosts that follow), and it is only at this time of year that they are available.

²³Kan [かん].

The Sadō Ko-ten Zenshu [茶道古典全集] states that this word refers to atsumono [羹], which is a hot soup (made by boiling pieces of fish or fowl -- such as previously roasted ko-tori [小鳥]* -- in broth, along with a selection of seasonal vegetables).

It seems this was included with the kashi (this dish is not mentioned in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho account of this chakai) to allow the guests to eat more, if they still felt hungry after the rather minimal food offerings that made up the kaiseki†.

__________

*Ko-tori [小鳥] is a general word for the various small sparrows and finches commonly taken by hawks. After removing the feathers and innards, these birds were roasted whole on a spit over a fire. The roasted birds, in this case, would have been cut into pieces, which were then added to the soup.

†As has been remarked upon before in this blog, during Rikyū's period people generally ate only two times each day -- in mid-morning, and in the evening.

At the earlier gathering, Rikyū served Hideyoshi and the other guests a rather normal breakfast, which theoretically should have kept them sated until evening. This being the case, and not knowing if Hideyoshi would have wanted to eat more, he seems to have taken this way of offering more food -- which could be accepted or rejected, as the guests saw fit.

²⁴Fu [ふ].

Fu [麩] is wheat gluten.

Perhaps this refers to pieces or strips of fu that were boiled in broth. They were usually tied in a flat knot (to make them easier to eat) before being served.

Fu could also be formed into balls that were deep-fried in oil.

It is unclear how the fu was prepared on this occasion.

0 notes