#household casebearer

Text

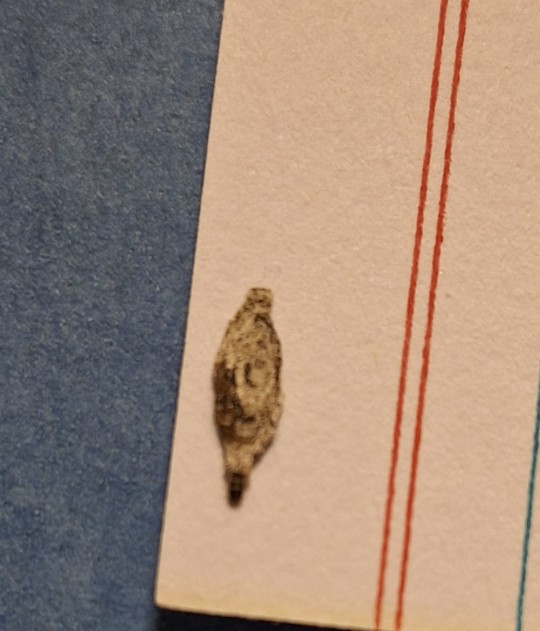

@terryblycute submitted: do you happen to know who this little fella is? it hangs on my wall, casing seems to be made out of fabric/lint & cat hair :D

(found in austria)

Yes, it’s a household casebearer moth caterpillar. As you noticed, they make their case from fibers they find in our houses. If there are a lot of them, they can cause quite a lot of damage, but one here and there doesn’t hurt :)

#animals#insects#bugs#submission#moth#caterpillar#larva#household casebearer#household casebearer moth

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

The quality isn't very good but here's a caseworm moth catterpillar I found in my house

The dark part at the bottom is his head :)

Hi! So sorry for the late reply

Fascinating! I tried to look up the caseworm moth to share some facts, but I only found the household casebearer moth. I’m curious: are they different names for the same moth or different moths? Please let me know if you can :]

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

household casebearer.

phereoeca allutella.

plaster bagworm.

kamitetep.

0 notes

Text

a prof de natureza passou um trabalho q era pra tirar foto de seis seres vivos e dpois classificar eles etc. eu to na aula online em casa e só tirei foto de aranha. e uma traça. abdjslabdnjslk

vo botar as fotos dpois.

.

the nature teacher gave a project that was to take pictures of six living beings and then classify them etc. I'm in online class at home and I just took pictures of spiders. and a moth (ok, apparently MOTH isnt the best word to call it, uhh Phereoeca uterella?? household casebearer????). ahfjsdonllafk

i'll put the photos later

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

One’s Debris, Another’s Home: Thinking with Household Casebearers (Phereoeca uterella)

by TAN ZI HAO

I

Holding on to the edge of ceilings like droplets of grey, clinging on to the most obscure corners like tiny yarns of pale strings, their bland existence seldom strikes our attention.

Minuscule and monochrome, they have all the properties to sustain our indifference. The Household casebearers (Phereoeca uterella) are a species of moth whose cocoons are made out of household debris. For taxonomic convenience, entomologists have imposed on them more abstract names befitting their characters. But the more generic “casebearers” or “bagworms” supplies a more interesting anecdote of the cocoon, for reconsidering the ontological foundation of what constitutes a house, and eventually, home.

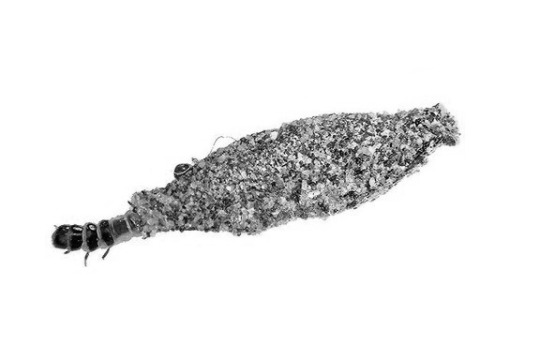

The casebearers are frequent dwellers of man-made houses in the tropics. Most abundantly bred in bathrooms and unventilated enclosures, they are accustomed to spaces with high atmospheric moisture. The moment a larva leaves its egg, it begins to construct a protective cocoon case for itself. Each case resembles the shape of a seed with an aperture at both ends. But unlike our typical house with an explicit, directional, entrance and exit, the two apertures are to the larva both entrance and exit, both front and back. Where the larva chooses to move forward is where the outlet faces the front. The head and thorax would emerge beyond the cocoon so as to reveal its thoracic legs, and slowly and jerkily, it would inch forward while dragging along its “house”. The “house”—the seed-like cocoon case—is as flat as a cardboard with the texture of a compressed felt. The centre is slightly convex to permit an oval tunnel for easier manoeuvring. Within this confinement, the larva hides itself from external threats, feeds upon spider webs, animal hairs, or dead skins it pulls from without, and therein, too, it defecates, molts, pupates.[1]

The uniqueness of the casebearer is inseparable from its case being a bricolage of scraps. What we swipe off as dust is reclaimed as building blocks. To weave a cocoon about double its length and triple its width, the larva generates silk filaments to string together soil and sand particles, insect droppings, and dusts of random stuff. With judicious precision, the methods it employs ensure silk material on the inside and hard particles on the outside.[2] The case is thus protected by a crust while the soft interior is rendered homely for its life function. The colour of the crust appears organic since it depends on whatever detritus available in its surrounding. Similar kin such as the Evergreen bagworm (Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis), who stays outdoor, dangling on pine trees, would have a darker colouration due to dead plant materials and other organic detritus it affixes to its cocoon. This orientation of bagworms and casebearers, inevitably, provides a natural camouflage effect,[3] for their cases could blend into their surrounding visual landscape without difficulty.

II

Enslaved by an instinct that feeds on and builds with (our) detritus, the casebearers present to us an opening for interspecies contemplation. What constitutes homeliness to the casebearer is to us the exteriority of the home. Their bricks, our debris; their food, our discards; their existence, our “pest”. Here we are not encumbered by the relativism of homeliness, neither are we interested to discern the boundary where one’s home begins and another’s ends. Rather, in thinking across Homo sapiens, Phereoeca uterella, Phereoeca allutella, Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis, and other bagworms and casebearers, we seek to understand the political implications of home-making, and hence, to a degree, home-wrecking, amid planetary conditionalities.

If a casebearer thrives on the anthropocentric culture of disposal, its existence, its presence is predicated on the absenting of ours, by what we disposed of. A history of detritus is unimaginable, until one imagines it as a residue that serves to validate an erstwhile presence. Viewed in this light, one understands why postcolonial studies of subalternity and marginality are always belated. They are left over by the march of History, Philosophy, Science, that propels the discourse of human knowledge with a multitude of domineering presences. Wars and violence, massacres, destructions, happenings, celebrations, victories, failures, for example, are events that present themselves to us, they punctuate the seamless milieu of our planetary history. The detritus of history is almost a non-history. For salience is pre-determined by civilisational discourse, rationality, presence, by happenings, by the proof of existence. In contrast, the absence or the inconspicuous detritus of history, never truly belongs. The gaps between presences are only investigated as a potential consolidation of our salience. As a thought experiment: if, there existed a species or a community that had lived and survived based on a culture of disposal, how would (our) History, Philosophy, Sciences, address it? If the species or the community demonstrates appreciation and salience only by the act of disposing, and keeps whatever that is insignificant, how would our existing modalities of knowledge be able to free us from the limitation of our epistemology, to the extent that, we cease to take presence as explicit evidence, and absence as a lack of data? What if presence signals the opposite of salience, and absence, something to them?

The ontology of presence single-handedly shapes the determinism of knowledge, and in consequence, the policies of many regimes. Clean knowledge without detritus for feeding ends with a hunt for a “pest” to be eliminated, for our sciences hold an unrelenting bias towards presence, be it the written, the documented, the historic.

III

To grasp the genuine philosophy of thinking with, and ultimately to share residence with Household casebearers, is to confront the realities of existence: [4] the ennui of living, surviving, and dying. The monochromatic case of the larva—made out of materials discarded and left behind by the janitor of the house—captures a planetary intersection between the living and dying, between preservation and disposal. The distinction of these terms, nonetheless, is still based on a prescriptive notion of what constitutes “life”, and implicitly, what is worthy of preservation, or, who deserves to live, whose house to build (and whose homes to wreck so to give space to others). The perception of life needs to be rid of our judgement of liveliness; whereas the perception of home needs to be rid of our judgement of homeliness. The casebearers demonstrate to humans that the overused remains pristine to its case-construction. Our residue brings to them the possibility of life; their home-making technology makes evident to us that the aged is not scraps, that detritus are no leftovers. But neither is the aged a distant gem to be prized or museumised within the nicety of a modern vitrine. The aged is an accumulation of memories to be reused and passed forward.

The casebearers know us better than we know ourselves. Their monochromatic appearance is a subtle reminder of what we have used, exploited, thrown away, ignored. The ebb and flow of life are all laid bare in their ashen grey – the colour that renders all vulnerable to time. Grey is the colour of the faded, the aged, the used. It is the murky zone where motley hues collide in equal measure. Grey teaches us the irreversibility of time and instills in us a sensibility for naked materiality. Definitely, for a colour this cunning and quiet, the grey is not all romantic. From pollution to haze to concrete jungles, and even the Capitalocene, has a penchant for grey. In recalling to us the vulnerability of life and the transience of living, grey arouses, from within us, perhaps, a care for the vulnerable, for the aged, and for those as tiny as casebearers. Grey softens, calms, absorbs, listens, forewarns, complicates. A close association of the refuse, grey is also the fading shadow, the indelible trace; herein the casebearers have intimate relation with our living and dying: their grey is symptomatic of ours; their birthing is symptomatic of our decaying; their grey is the trace of our living.

The casebearers ask for no rapt attention of ours, but lives on silently in our vicinity. Cloaked in grey, pale by comparison, and yet, their legacy contests and fertilises our certitude of home-making. The casebearers display an aesthetic of the aged, and have, from the very start, lifted itself from the façade of any schematic interior design that seeks to falsify the natural appearance of the material. As we renovate our houses and paint our walls anew, we give in to a desire to undo time. “Anti-aging” technology as such hardly impresses the casebearers, who long comprehend the impossibility of eternal youth. Cosmetics and paints are a denial of material vulnerability. The casebearers esteem the passing of time and the aging of materials. Just as they hide themselves in grey, cocooning themselves in the assemblage of our household detritus, they demonstrate to us the reality of living vulnerably, they display for us, in their mournful grey, the crucible of decay and the possibility of dying. They prophesy a moth-eaten future: not always hopeful, not always happy. And as they metamorphose into moths, they leave their cases hanging on our dusted walls. The debris-laden cases turn into waste, and sooner or later, into dust balls entangled with old spider webs, as is only fitting.

===

Notes:

[1] Annette Aiello, “Life History and Behavior of the Case-Bearer Phereoeca Allutella (Lepidoptera: Tineidae)”, Psyche 86, 2–3 (1979): 125–136.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The casebearers are not alone as a debris-carrying larva with an intent to camouflage their body with exogenous materials. See: Catherine A. Tauber, Maurice J. Tauber, & Gilberto S. Albuquerque, “Debris-Carrying in Larval Chrysopidae: Unraveling Its Evolutionary History”, Annals of the Entomological Society of America 107, 2(2014): 295–314; Miriam Brandt & Dieter Mahsberg, “Bugs with a backpack: the function of nymphal camouflage in the West African assassin bugs Paredocla and Acanthaspis”, Animal Behavious 63, 2(2002): 277–284.

[4] Lorraine Daston & Gregg Mitman, “The How and Why of Thinking with Animals”, in Lorraine Daston & Gregg Mitman (eds.), Thinking with Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), pp. 1–14.

0 notes

Photo

@gaiawonderland submitted: Hi! I found this fella in my sink a few days ago and I was hoping for an ID because I've never seen a creature quite like it before. It either had two heads (?) or could pop out back and forth from either side of it's little casing/shell very quickly. And it moved around by means of its mouth, kind of resembling an inch worms movement. I live in central florida! Thanks in advance! :)

Hello! It's a household casebearer moth caterpillar. Would be cool if they had two heads! But no, they have an opening at each end of their case and space inside to turn around easily. Their case is made from their own silk and debris from their environment. The caterpillars eat spider and other bug silk, human hair and dander, and wool, so they can potentially be damaging to fabrics in your house. Adults look like this:

Precious :)))) Photo by simondenis142857

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

@wiseheartedloki submitted: These little guys keep showing up in my house! I think they miiight be a moth caterpillar since we also have a lot of moths around, but I’m curious if it can be narrowed down a bit more? The pics aren’t the best, so I might as well describe them? Their cocoons are kinda gray, and they look sort of cream/yellow colored, with a black tip. I can’t tell if it’s at the top, bottom, or both, but it’s most likely both, since I’ve seen them pop out of both ends of the cocoon. If it helps, I live in CA, and I’ve seen these guys pretty much year round? Aaa sorry if that’s a lot. Either way… Bug pics!

It looks to me like a household case-bearing moth larva. They construct cases out of fibers they find in their environment - so in your house that could be from clothes or carpets or even human and pet hair. Their cases can be different colors depending on what kind of fibers they’re collecting for it. They can also be quite destructive as they feed on and make cases from a variety of things around your house, including the examples above and a ton of other things as well. You can certainly google if you’re more interested in learning what could be a potential food item for them.

The dark end is their head but they do have openings at both ends of the case and can turn around inside it. Here’s one in its case!

Adults are very small and nondescript - about 1cm or so long and generally just a beige color:

Gif by catchang and photo by simondenis142857

#animals#insects#bugs#submission#both#caterpillar#larva#household casebearer#household case bearing moth#moth#clothes moth#case bearing clothes moth

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you happen to know what these squirmy fellows are? I found tons of them in my balcony, they seem to be some sort of moth larva? They have these v tiny cocoon-thingies and they climb walls while wearing them. Found in Buenos Aires Argentina

Yes, it’s a plaster bagworm moth caterpillar. They’re sometimes called household casebearers which is more correct since it’s not technically a bagworm (in the Psychidae family). They make their cases out of silk and coat them with environmental debris for camouflage. They’re open at both ends and the middle is wider so they have room to turn around inside and poke their head out either end. They like to eat silk of other bugs and also shed human hairs and wool and other various animal fibers. Yum!

38 notes

·

View notes