#i think its interesting to compare the difference between concepts derived from the idea of a fallen angel

Text

Rumination Week 12

This week in class we discussed and reviewed chapter 8 in the textbook surrounding “Postmodernism,” which can be compared with “Modernism.” Postmodernism can be defined as the characterization of the “post-modern” worldview. With the world exiting the postindustrial age and entering the newly characterized modern period surrounding ideas that “have become the conditions in postmodernity alongside and in relation to virtual technologies with the flows of capital, information, and media in the era of globalization.” (S&C pg. 302) I was slightly confused when first introduced to this topic in comparison to “modernism”. Reading from the book we learned about some scholars who first took up these concepts from French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard in the 1980s. These changing conditions in the “postmodern” age led to heavy skepticism of human knowledge and subjectivity surrounding enlightened thoughts, universal ideas of self, positivist science, and foundationalism derived previously from the “modern” age. According to the text “In Lyotard’s view, the problem was not that modernity’s truths could be proven false. Rather, he criticized the very quest for truth” (S&C pg. 303). Postmodernism focuses on describing and grasping the concepts which follow the contingencies of an ever-changing world, one with no bounds or limitations, and through irrational thinking has become increasingly transformative with the growing multiplicity of beliefs and experiences within the world. I find this to be my favorite aspect surrounding post-modernism. Though it’s noted there is no precise rupture between the two, “postmodernism” is characterized to be more skeptical of the views of foundationalism, science, and technology. This was a characteristic generated following the aftermath surrounding the horrors of the Holocaust and the nuclear bombing of Japan. “Postmodernity” names itself this period after World War II through its ideas it became especially prevalent during the late 1960s. Because postmodernism has an increasingly transformative nature, it allows for a magnitude of different human experiences to be expressed no matter how abstract and to also be recognized and distributed through the different mediums of knowledge and culture. This shapes what “Postmodernist practitioners emphasize (as the) mediation and structural instability, that question(s) the idea that there is a singular modern subject or essence of humanity.” (S&C pg. 304) This allows for all types of expression to flourish through many mediums that allow them to find others who share similar ideas/interests. That unique expression surrounding postmodernism I believe is what allows humanity to continue to change and glow uniquely and is responsible for this week's p2p on Remixing to be a fun one.

Sturken, M., & Cartwright, L. (2018). Practices of looking: An introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford University Press.

0 notes

Note

OK so I'm trying to learn about AoS and I just found out there's like a cult of good people who get destroyed by skaven but before that it says they believed their founder was Daemon that "set aside it's heinous ways to seek purity."

Can you imagine? Paarthurnax daemon

every day i wonder more what the actual fuck daemons even are. wdym it set its ways aside, like what does that imply about daemons?? about the daemonic mind?? i'm so deeply confused

#ask#alzraed#i dont think daemons can be like super equiv to peepaw Partysnax#just bc tes dragons are explicitly on the Person side of the divide#rather than the Force of nature/Not a person side#or the weird inbetween 40k daemons are in#but i do think comparing them is interesting#(''what do you think it would look like if we mixed among us and naruto'' aside)#bc theyre both concepts that draw a lot from religion#and from concepts that at least in christianity (im not sure other religions but if yk pls lmk) are very closely tied#ICYMI elder scroll dragons are functionally Akatosh's Angels#abridging a bunch of lore here. it's sick#not to say a nice thing about mickey kinkbride but alduin fucks as a concept#Dragon Lucifer#i think its interesting to compare the difference between concepts derived from the idea of a fallen angel#vs derived from the general idea of demons#bc the aftereffect is super different#gameplay aside the narrative of skyrim treats the dragons way more respectfully than 40k treats daemons#and obviously the tones are very different#but it's still a very fun thing to think about#it also says a lot about how 40k vs elder scrolls treat their gods#i think tes having an actual concept of good and loving authority is actually to its detriment#compared to 40k#bc in 40k when the gods do fucked up shit its a feature not a bug#but in elder scrolls Akatosh is kinda just straight up a war criminal#but hes on the humans' side so i guess hes good#theres just not really enough questioning of the cyrodiilic empire in elder scrolls#i have the same criticism twrds 40k and the imperium of man but its different#because in 40k the imperium is called into question by its very concept#like it's a dystopia on purpose

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Imagine that the US was competing in a space race with some third world country, say Zambia, for whatever reason. Americans of course would have orders of magnitude more money to throw at the problem, and the most respected aerospace engineers in the world, with degrees from the best universities and publications in the top journals. Zambia would have none of this. What should our reaction be if, after a decade, Zambia had made more progress?

Obviously, it would call into question the entire field of aerospace engineering. What good were all those Google Scholar pages filled with thousands of citations, all the knowledge gained from our labs and universities, if Western science gets outcompeted by the third world?

For all that has been said about Afghanistan, no one has noticed that this is precisely what just happened to political science. The American-led coalition had countless experts with backgrounds pertaining to every part of the mission on their side: people who had done their dissertations on topics like state building, terrorism, military-civilian relations, and gender in the military. General David Petraeus, who helped sell Obama on the troop surge that made everything in Afghanistan worse, earned a PhD from Princeton and was supposedly an expert in “counterinsurgency theory.” Ashraf Ghani, the just deposed president of the country, has a PhD in anthropology from Columbia and is the co-author of a book literally called Fixing Failed States. This was his territory. It’s as if Wernher von Braun had been given all the resources in the world to run a space program and had been beaten to the moon by an African witch doctor.

…

Phil Tetlock’s work on experts is one of those things that gets a lot of attention, but still manages to be underrated. In his 2005 Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, he found that the forecasting abilities of subject-matter experts were no better than educated laymen when it came to predicting geopolitical events and economic outcomes. As Bryan Caplan points out, we shouldn’t exaggerate the results here and provide too much fodder for populists; the questions asked were chosen for their difficulty, and the experts were being compared to laymen who nonetheless had met some threshold of education and competence.

At the same time, we shouldn’t put too little emphasis on the results either. They show that “expertise” as we understand it is largely fake. Should you listen to epidemiologists or economists when it comes to COVID-19? Conventional wisdom says “trust the experts.” The lesson of Tetlock (and the Afghanistan War), is that while you certainly shouldn’t be getting all your information from your uncle’s Facebook Wall, there is no reason to start with a strong prior that people with medical degrees know more than any intelligent person who honestly looks at the available data.

…

I think one of the most interesting articles of the COVID era was a piece called “Beware of Facts Man” by Annie Lowrey, published in The Atlantic.

…

The reaction to this piece was something along the lines of “ha ha, look at this liberal who hates facts.” But there’s a serious argument under the snark, and it’s that you should trust credentials over Facts Man and his amateurish takes. In recent days, a 2019 paper on “Epistemic Trespassing” has been making the rounds on Twitter. The theory that specialization is important is not on its face absurd, and probably strikes most people as natural. In the hard sciences and other places where social desirability bias and partisanship have less of a role to play, it’s probably a safe assumption. In fact, academia is in many ways premised on the idea, as we have experts in “labor economics,” “state capacity,” “epidemiology,” etc. instead of just having a world where we select the smartest people and tell them to work on the most important questions.

But what Tetlock did was test this hypothesis directly in the social sciences, and he found that subject-matter experts and Facts Man basically tied.

…

Interestingly, one of the best defenses of “Facts Man” during the COVID era was written by Annie Lowrey’s husband, Ezra Klein. His April 2021 piece in The New York Times showed how economist Alex Tabarrok had consistently disagreed with the medical establishment throughout the pandemic, and was always right. You have the “Credentials vs. Facts Man” debate within one elite media couple. If this was a movie they would’ve switched the genders, but since this is real life, stereotypes are confirmed and the husband and wife take the positions you would expect.

…

In the end, I don’t think my dissertation contributed much to human knowledge, making it no different than the vast majority of dissertations that have been written throughout history. The main reason is that most of the time public opinion doesn’t really matter in foreign policy. People generally aren’t paying attention, and the vast majority of decisions are made out of public sight. How many Americans know or care that North Macedonia and Montenegro joined NATO in the last few years? Most of the time, elites do what they want, influenced by their own ideological commitments and powerful lobby groups. In times of crisis, when people do pay attention, they can be manipulated pretty easily by the media or other partisan sources.

If public opinion doesn’t matter in foreign policy, why is there so much study of public opinion and foreign policy? There’s a saying in academia that “instead of measuring what we value, we value what we can measure.” It’s easy to do public opinion polls and survey experiments, as you can derive a hypothesis, get an answer, and make it look sciency in charts and graphs. To show that your results have relevance to the real world, you cite some papers that supposedly find that public opinion matters, maybe including one based on a regression showing that under very specific conditions foreign policy determined the results of an election, and maybe it’s well done and maybe not, but again, as long as you put the words together and the citations in the right format nobody has time to check any of this. The people conducting peer review on your work will be those who have already decided to study the topic, so you couldn’t find a more biased referee if you tried.

Thus, to be an IR scholar, the two main options are you can either use statistical methods that don’t work, or actually find answers to questions, but those questions are so narrow that they have no real world impact or relevance. A smaller portion of academics in the field just produce postmodern-generator style garbage, hence “feminist theories of IR.” You can also build game theoretic models that, like the statistical work in the field, are based on a thousand assumptions that are probably false and no one will ever check. The older tradition of Kennan and Mearsheimer is better and more accessible than what has come lately, but the field is moving away from that and, like a lot of things, towards scientism and identity politics.

…

At some point, I decided that if I wanted to study and understand important questions, and do so in a way that was accessible to others, I’d have a better chance outside of the academy. Sometimes people thinking about an academic career reach out to me, and ask for advice. For people who want to go into the social sciences, I always tell them not to do it. If you have something to say, take it to Substack, or CSPI, or whatever. If it’s actually important and interesting enough to get anyone’s attention, you’ll be able to find funding.

If you think your topic of interest is too esoteric to find an audience, know that my friend Razib Khan, who writes about the Mongol empire, Y-chromosomes and haplotypes and such, makes a living doing this. If you want to be an experimental physicist, this advice probably doesn’t apply, and you need lab mates, major funding sources, etc. If you just want to collect and analyze data in a way that can be done without institutional support, run away from the university system.

The main problem with academia is not just the political bias, although that’s another reason to do something else with your life. It’s the entire concept of specialization, which holds that you need some secret tools or methods to understand what we call “political science” or “sociology,” and that these fields have boundaries between them that should be respected in the first place. Quantitative methods are helpful and can be applied widely, but in learning stats there are steep diminishing returns.

…

Outside of political science, are there other fields that have their own equivalents of “African witch doctor beats von Braun to the moon” or “the Taliban beats the State Department and the Pentagon” facts to explain? Yes, and here are just a few examples.

Consider criminology. More people are studying how to keep us safe from other humans than at any other point in history. But here’s the US murder rate between 1960 and 2018, not including the large uptick since then.

So basically, after a rough couple of decades, we’re back to where we were in 1960. But we’re actually much worse, because improvements in medical technology are keeping a lot of people that would’ve died 60 years ago alive. One paper from 2002 says that the murder rate would be 5 times higher if not for medical developments since 1960. I don’t know how much to trust this, but it’s surely true that we’ve made some medical progress since that time, and doctors have been getting a lot of experience from all the shooting victims they have treated over the decades. Moreover, we’re much richer than we were in 1960, and I’m sure spending on public safety has increased. With all that, we are now about tied with where we were almost three-quarters of a century ago, a massive failure.

What about psychology? As of 2016, there were 106,000 licensed psychologists in the US. I wish I could find data to compare to previous eras, but I don’t think anyone will argue against the idea that we have more mental health professionals and research psychologists than ever before. Are we getting mentally healthier? Here’s suicides in the US from 1981 to 2016

…

What about education? I’ll just defer to Freddie deBoer’s recent post on the topic, and Scott Alexander on how absurd the whole thing is.

Maybe there have been larger cultural and economic forces that it would be unfair to blame criminology, psychology, and education for. Despite no evidence we’re getting better at fighting crime, curing mental problems, or educating children, maybe other things have happened that have outweighed our gains in knowledge. Perhaps the experts are holding up the world on their shoulders, and if we hadn’t produced so many specialists over the years, thrown so much money at them, and gotten them to produce so many peer reviews papers, we’d see Middle Ages-levels of violence all across the country and no longer even be able to teach children to read. Like an Ayn Rand novel, if you just replaced the business tycoons with those whose work has withstood peer review.

Or you can just assume that expertise in these fields is fake. Even if there are some people doing good work, either they are outnumbered by those adding nothing or even subtracting from what we know, or our newly gained understanding is not being translated into better policies. Considering the extent to which government relies on experts, if the experts with power are doing things that are not defensible given the consensus in their fields, the larger community should make this known and shun those who are getting the policy questions so wrong. As in the case of the Afghanistan War, this has not happened, and those who fail in the policy world are still well regarded in their larger intellectual community.

…

Those opposed to cancel culture have taken up the mantle of “intellectual diversity” as a heuristic, but there’s nothing valuable about the concept itself. When I look at the people I’ve come to trust, they are diverse on some measures, but extremely homogenous on others. IQ and sensitivity to cost-benefit considerations seem to me to be unambiguous goods in figuring out what is true or what should be done in a policy area. You don’t add much to your understanding of the world by finding those with low IQs who can’t do cost-benefit analysis and adding them to the conversation.

One of the clearest examples of bias in academia and how intellectual diversity can make the conversation better is the work of Lee Jussim on stereotypes. Basically, a bunch of liberal academics went around saying “Conservatives believe in differences between groups, isn’t that terrible!” Lee Jussim, as someone who is relatively moderate, came along and said “Hey, let’s check to see whether they’re true!” This story is now used to make the case for intellectual diversity in the social sciences.

Yet it seems to me that isn’t the real lesson here. Imagine if, instead of Jussim coming forward and asking whether stereotypes are accurate, Osama bin Laden had decided to become a psychologist. He’d say “The problem with your research on stereotypes is that you do not praise Allah the all merciful at the beginning of all your papers.” If you added more feminist voices, they’d say something like “This research is problematic because it’s all done by men.” Neither of these perspectives contributes all that much. You’ve made the conversation more diverse, but dumber. The problem with psychology was a very specific one, in that liberals are particularly bad at recognizing obvious facts about race and sex. So yes, in that case the field could use more conservatives, not “more intellectual diversity,” which could just as easily make the field worse as make it better. And just because political psychology could use more conservative representation when discussing stereotypes doesn’t mean those on the right always add to the discussion rather than subtract from it. As many religious Republicans oppose the idea of evolution, we don’t need the “conservative” position to come and help add a new perspective to biology.

The upshot is intellectual diversity is a red herring, usually a thinly-veiled plea for more conservatives. Nobody is arguing for more Islamists, Nazis, or flat earthers in academia, and for good reason. People should just be honest about the ways in which liberals are wrong and leave it at that.

…

The failure in Afghanistan was mind-boggling. Perhaps never in the history of warfare had there been such a resource disparity between two sides, and the US-backed government couldn’t even last through the end of the American withdrawal. One can choose to understand this failure through a broad or narrow lens. Does it only tell us something about one particular war or is it a larger indictment of American foreign policy?

The main argument of this essay is we’re not thinking big enough. The American loss should be seen as a complete discrediting of the academic understanding of “expertise,” with its reliance on narrowly focused peer reviewed publications and subject matter knowledge as the way to understand the world. Although I don’t develop the argument here, I think I could make the case that expertise isn’t just fake, it actually makes you worse off because it gives you a higher level of certainty in your own wishful thinking. The Taliban probably did better by focusing their intellectual energies on interpreting the Holy Quran and taking a pragmatic approach to how they fought the war rather than proceeding with a prepackaged theory of how to engage in nation building, which for the West conveniently involved importing its own institutions.

A discussion of the practical implications of all this, or how we move from a world of specialization to one with better elites, is also for another day. For now, I’ll just emphasize that for those thinking of choosing an academic career to make universities or the peer review system function better, my advice is don’t. The conversation is much more interesting, meaningful, and oriented towards finding truth here on the outside.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

how do you see andrastianism being portrayed in northern thedas, especially in tevinter with its entirely separate chantry? is it going to be noticeably different than in past games do you think? looking back, the southern chantry and its templars, specifically, have played an Enormous role in the plots of the past DA games. it’s going to be interesting having a game without them, in a way...

Hello! Great question. This became long so it’s under a cut.

Hopefully true to the established lore and different in the ways and where it’s meant to be.

I think the most considerable or notable differences will be less in Andrastianism - as in, individual peoples’ personal faiths, their interactions with and conceptions of it, and how they relate to it and it to the world around them - and more in the institutional, organizational differences in the structures of the Imperial Chantry, and how that subsequently shapes Tevinter society and culture.

The former naturally varies between individuals already, as with southern Andrastians and many religions in our world. Our most visible examples of Tevinter Andrastians so far are Fenris (see his banters with Sebastian) and Dorian (see early conversation at Haven). From the little insight we get into their feelings on their faith and their opinions on it, we can see a bit of that variance, and it’s naturally colored by their respective life experiences in Tevinter. Fenris’ faith was never strong; he says it’s difficult for a slave to have faith in someone who abandoned them. Danarius, like a lot of Magisters who own slaves I assume, didn’t allow his slaves religious teaching or access to formal aspects of the faith, in order to deny them a sense of self-worth. Early on, Fenris feels that the Maker didn’t help him and doesn’t care for him or indeed anyone, and struggles somewhat to reconcile that and to square away the Maker’s existence with the ills of the world. Eventually, by Act 3, Sebastian comments that he noticed Fenris in the Chantry one day, praying.

Dorian identifies as Andrastian, but doesn’t “believe in the Chantry”. He thinks both the Imperial Chantry and the southern Chantry are outdated relics desperately clinging to relevance. He acknowledges that this opinion doesn’t make him popular - from that we can infer how his Tevinter peers from his social strata tend to feel about the Chantry, at least publicly. He doesn’t like the... not sure how to phrase it or what this is called, but like the piety-type religious practise aspects? It makes sense, given his personality and story arc in DAI, that he’s someone who would chafe under being told what to do and how to live his life. You can also see where such sentiments would in part originate considering his background (having once essentially been shipped off by his father to an expensive school in Minrathous known for its adherence to strict Andrastian discipline). At the same time he knows that he doesn’t know everything, has feelings of being small in the grand scheme of things (this stuff is an interesting layer to his character, as he usually presents as quite self-assured, sometimes larger than life, and is inclined to refer to his skill and intellectual prowess), and believes in something bigger than him existing, because the idea of there being nothing scares him.

The latter most obviously shows up in how Tevinter societal structure is flipped, with the elite mages at the top running things. It’s evident in things like how men and mages are allowed to be part of the priesthood as well as in Tevinter social mores - more tolerant views of magic, magical ability as a valued trait, blood magic’s pretty okay, magic widely-practised in society, etc. The Imperial Chantry holds some different beliefs, such as that blood magic was learned by humanity from ancient elves from Elvhenan, as opposed to from the Old Gods, and that the lies of the Old Gods are what was ultimately responsible for the actions of the ancient Magisters that led to the Blights, as opposed to mortal pride. They believe that Andraste was only a mortal prophet, albeit a mage, and even forbid worship of her. And they fundamentally reeeally diametrically disagree with the southern Chantry on the meaning of “magic exists to serve man, and never to rule over him”. Instead of ‘mages should be controlled, they’re nefarious’ it’s ‘magic’s great, it should be used for the good of mankind and we’ll do that by having mages rule’. Some of this stuff diverges quite a lot from the southern Chantry, but Dorian does comment that most of the Imperial Chantry’s teachings are the same as in the south “...despite some finicky bits about magic”.

I’m looking forwards to Tevinter as a setting, in part because of these kinds of differences that it has (speaking here of these aspects of its society, not others). It’s different. It’s fresh. I’m kinda weary of the south, and definitely of the southern Chantry. I’m interested to see these things that are established and referred to ‘in person’, as it were. As you say, the southern Chantry and things associated with it have been at the forefront so far due to its prevalence in the south - it’s time for something new! Beats like “mages vs templars” are well-trodden by now. The interplay between mages and templars in Tevinter isn’t comparable. The role of magic and the lot of many mages in Tevinter is totally different to what we’ve been dealing with so far. I guess my main point in answer to the question of Andrastianism’s portrayal in the north is a bit broad; like, I’m heeere for the new stuff, that interesting setting, and I hope they do the noted differences justice.

Even more minor stuff like: How Dorian had never heard of the Seekers of Truth as they don’t exist in Tevinter (he questioned Cassandra about what they are and wondered if they were some kind of “super Templar”, lol). How there are a lot of Tranquil in Tevinter, but there it’s a sentence handed down by the Magisterium for “abuse of magic” which conveniently has “many interpretations” (the inference being it’s a handy way among the scheming elite to get rid of political rivals). That the Magisters still make sacrificial offerings in rituals, ostensibly nowadays pretending that such things are for Andraste and the Maker rather than the Old Gods. The harsher and more direct political workings of the Imperial Chantry compared to the southern one - like, it sounds like it’s totally normal for the Black Divine to openly slaughter all his enemies after he ascends. Do the templars in Tevinter get chips on their shoulder because they’re basically cityguard Magister-goons and have no real power? Imagine Magisters being confronted by a southern templar NPC’s powers. Imagine the arcane knowledge and mysteries in the libraries of the Tevinter Circles, or going to an Imperial Chantry service and seeing the magic that’s performed at those. What an intense backdrop and sandbox to be exploring. I wanna meet the Black Divine.

There isn’t much currently known about Andrastianism/the Chantry as it is in Antiva that’s specific to there or that ‘jumps’ out, so it would be nice to learn a bit more on that front. Rivain of course is mostly not Andrastian. I don’t know if we’ll visit there in this game (locales like Tevinter, Nevarra and so on feel more likely) but would certainly reeeally love to do so and explore their pantheism and belief in the Natural Order. There’s a lot of really interesting stuff there like their seers, the long-established local traditions, even the Qun. The Anders are super pious - I’m sure if we visit Weisshaupt for example we’ll encounter Andrastians who are more devoted and more dour even than their southern counterparts. Nevarra is where again it gets quite different, and in a ‘potentially quite pertinent since it feels like we’ll go there’-kinda way. Their mages have almost as much power as Magisters do in the Imperium, and the populace has those hyper-specific and fascinating beliefs on death. The political intrigue there, their niche unparalleled knowledge of the dead, their influence on King Markus... more awesome, interesting new shit for a setting.

Not sure if this really answers your question. 😅 Basically I’m really excited to go north because some aspects of it are so different, even in fixtures of the setting like the Chantry and in Andrastian belief. I’d like to see some of the differences ‘northern Andrastianism’ has in action outside of Codexes and “back in my homeland” dialogue, especially in external stuff like societal structure and culture. I’m ready for mage-rule opposite-land for a change (not because it’s good or bad but because it’s different), and for new dynamics and different spins on old worn plotbeats. I can see the Imperial Chantry being prominent in the story and I welcome the fact that the domineering rhetoric around us will be somewhat changed up after three games in the south. Obviously the Magisters dominate the Imperium and they derive that right to rule from the Imperial Chantry’s beliefs/teachings. I’d guess we will be mostly leaving southern Chantry stuff mostly behind, as that allows the writers to keep the diverging ‘the new Divine’s way of doing things’ stuff off-screen. Time for different groups to play big roles, like the Magisters, the Qunari, the Crows. And some revelation about the faith of some description, like that Andraste was secretly a ghast in disguise, wouldn’t go amiss either.

#dragon age 4#the dread wolf rises#dragon age#bioware#mj replies#vir-abelasan#video games#fenris#the Fenaissance#cassandra pentaghast#my lady paladin#heck yeah Tevinter as an RPG setting#goodbye southern chantry#BioWare hit me with an Imperial Chantry loredump pls#I wonder if we'll get a chance to depose the current Black Divine and influence the selection of the new one (eventually)#intrigue intrigue intrigue#political machinations#a totally different societal setup#and reversal of the way roles are now#the Imperial Chantry and by extension the Magisterium feels like the machinations we took part in#in the Bhelen or Harrowmont arc but like.. cubed

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abandon Ideology

In Jordan Peterson’s second foray into self-help, he writes his VI’th rule for life: ‘Abandon Ideology.’ As an ardent follower of Jordan’s, on first reading of this, I took this rules’s implications at face value; that is, the implication that an ideology is something that is held by a group of people, but that the individual, striving for what is true and pure, should rid themselves of all ideology, in the interest of progressing new and helpful ideas to the culture at large. Recently, particularly after having watched this YouTube video by Philosophy Tube, a question which I wrestled with subtly after reading Jordan’s recent work has made its way to the forefront of my mind: Are we so sure that it is even possible to abandon ideology? and I don’t mean once you already ‘have one’, so to speak (though this is a valid question also, albeit requiring a few more prior assumptions), but rather, is it even possible for an individual to not have an ideology? (Paraphrased,) Philosophy Tube makes this point explicitly, comparing ideology to a**holes: everyone has them, they use them everyday, but nobody tends to take a good look at their own unless something has gone wrong. So who is right?

Interestingly, both philosophers consider ideology to be something that actually exists - which, to me, is by no means a foregone conclusion. Jordan assumes that it is a sort of group-think parasite that infests the mind, while Philosophy Tube believes that ideology is an inevitable function within the individual. Anecdotally, I’ve noticed that the latter tends to be a more common belief among those with left political leaning, while Jordan’s point tends to be expressed by individuals who are more popular with those with right political leaning*. As we know that political leaning seems to be a result of a temperamental difference between individuals, it could be that this is just another form of what one could theorize as the fundamental question between the extremes of such differentiations, which is the question of whether the individual is fundamentally formed through nature or nurture. I have personally arrived at the conclusion, as have others, that the answer to this question is clearly both; however, the question of whether or not ideology is fundamentally group-oriented or individual-orientated doesn’t quite fit neatly into the dimensions of this theory. This is because, in no small part, that the roles of thought in regards to ideology in this case are antithetical to the typical hypothesis presented by the theory: in this case, the left leaning individuals are the one’s more likely to believe that ideology is an innate characteristic (nature), where as the right leaning individuals are more likely to believe that ideology is a product of culture (nurture). While it may not be a perfect comparison, this is the reverse of what an individual who agrees with this line of logic would likely guess. Is there a reason for this?

Perhaps it is the more fundamental tenant of conservatism, which tends to prize its own culture’s tradition, that demands from its right-wing thinker a bias in believing that their own way of interpreting the world is the ‘correct’ way to do so, based on the interpretation of the facts of ‘objective reality,’ which is free of ideology, because that is the way it is has always been; or perhaps it is liberalism’s inclination towards progression - its greatest strength and weakness simultaneously - that forces it to be open to all possibilities, and therefore implying that there is no single way of being, there is no objective reality, because reality could be anything based on the individual’s own subjective experience, based on their own ideology, which must therefore be present in all of us; or, perhaps, (and this is in no way to imply a comprehensively exclusive list) there is the consideration which I mentioned above, which questions the existence of ideology as an objective truth altogether.

[Aside: for sh*ts and giggles, let’s explore this last idea. So ‘ideology’, stems from the french word idéologie, where idéo- or ideo- is “idea”, and -logie or -logy is “the (scientific) study of the subject field represented by the stem.” (From Merriam-Webster.com). Also from Merriam-Webster: “Though ideology originated as a serious philosophical term, within a few decades it took on connotations of impracticality thanks to Napoleon, who used it in a derisive manner. Today, the word most often refers to ‘a systematic body of concepts,’especially those of a particular group or political party.” So according to this definition, ideology is more of a strictly philosophical or scientific term referring to the study of ideas. Well, everyone has ideas. But somehow this definition doesn’t quite seem to fit the bill. It seems as though both sides of the political spectrum seem to regard ideology as something deeper than the this definition gives it credit. It seems as though according to the political (to use a loose term to define the parameters of this debate) debate, believes that ideology is either a type of group-oriented idea that can inhabit a large swath of people, or it is the fundamental subjective framework that the individual uses to interpret the world. Of course, I doubt many serious thinkers on the right would deny that everyone needs a framework for which to use to interpret the world (Jordan Peterson certainly doesn’t). Instead, they would argue that framework is not the same as ideology, but simply a tenant of being human, as a combination of both an individual’s objective and subjective experience (and of course one could argue about whether objective experience actually exists also, but that’ll have to be another topic for another day; today we will assume that both objective and subjective experiences are real). But this also begs the question, why is it that some people can have an ideology while others can be free from it? This brings the argument illustrated nicely by Gad Saad into play; namely, that ideology is the equivalent of an idea pathogen, echoed by the complimentary position presented by Jordan’s work which contends with the idea that although not everyone need be infected by an idea parasite, everyone must have a narrative framework to operate in the world. This in and of itself, of course, asks us to contend with the question of whether or not there is even a difference between this “narrative framework” and ideology, to which we may get different answers based on the political leaning of the person whom we ask. As my inherent bias seems to lean to the right in most cases, my intuition tells me that there is a difference, that narrative framework is superordinate to ideology, but again, its difficult to assess whether or not that is my tendency towards conservatism and its respect of (let’s say the west’s) cultural background getting in the way of objectivity, sustaining that objectivity is real in the first place. But to play devil’s advocate to the side opposite to my intuition in a different way, I would say that it’s possible that the real problem is that we do not have our definitions straight: what is ideology to one may be narrative framework to another; and in this sense, I might also add that it is entirely possible that ideology itself does not exist past what may also be considered a narrative framework, since what one would call an ideology another may say they are only acting in according to their own narrative framework (or, “yes, I do have an ideology, but - of course - so do you). The obvious argument to refute this would likely refer to the nature in which an individual with an accused ideology would hold beliefs which mirror that of another individual with the same ideology, therefore rendering the ideas non-unique. And this is indeed a powerful argument. It’s also an argument which, hitherto, I never second guessed. But thinking now, of course it isn’t the case that two individuals narrative frameworks cannot be influenced by similar subjective experiences. This gets more complicated when you compound uncountable numbers of people who have “the same ideology,” and therefore expressing similar subjective experiences that derived their narrative frameworks; after all, could that many people really have had such identical experiences that they are brought to such similar beliefs independent from and “idea parasite” or ideology? Maybe not, but also, maybe the subjective experiences and narrative framework (or ideology), of the accuser has led them to a sort of confirmation bias, where one signal of similarity leads them to the expectation of uniformity; where the sight of a leaf of a certain type or color leads to certainty that that leaf must belong to a specific breed of tree, rather than perhaps a tree of only similar lineage. In this regard, with special consideration given to the possibility of miscommunication of words and their definitions, it is possible that the deeper form of “ideology” within the context of our current culture, does not even exist. It’s certainly a possibility which I will be keeping my eyes and ears on, anyways. End Aside.]

A conclusion about who is right certainly won’t be reached in a blog post by me today. What I can conclude from this thought experiment, however, is yet another example of why your intuition - based from your temperament and experience - can lead you astray when considering complex questions. Or even seemingly non-complex issues, for that matter. The perspective that Jordan Peterson provides may very well be the correct one. But the perspective that Philosophy Tube highlights as well feels as though it could be superior. Then there is the possibility that they are both wrong - or both right (it is such a strange world we live in, after all, where paradoxes are known to exist). One thing is for certain: both of these people are much smarter than I, so, as per usual, there is much left to consider and ponder. And to gather erratically.

One day I will start to write blog posts that focus more on my reader than my inner ramblings. But for now, I still need to sort myself out, and I hear writing can be incredibly useful for that. This is ErraticWoolGathering, after all.

Best,

- Alex

*An example of this that I can bring to mind is exemplified by Gad Saad, author of The Parasitic Mind, who similarly claims - as I understand it - that ideology is a matter of group-think, or in his words, that an ideology is no different than a type of “idea pathogen.” Now, whether Gad claims to be of right political leaning or not (as far as I know, he does not), his book and his ideas clearly seem to be more popular with the the right-wing of our culture than they are with our left-wing.

0 notes

Text

Bird Brains: Better than We Thought

Alternative Neural Architectures for Consciousness

The issue of Science for 25 September 2020 features a crow on its cover with the headline “Avian Awareness: Carrion crows display sensory consciousness.” There are three articles in the journal on this theme, “A neural correlate of sensory consciousness in a corvid bird” by Andreas Nieder, Lysann Wagener, and Paul Rinnert, “A cortex-like canonical circuit in the avian forebrain” by Martin Stacho, Christina Herold, Noemi Rook, Hermann Wagner, Markus Axer, Katrin Amunts, and Onur Güntürkün, and “Birds do have a brain cortex—and think” by Suzana Herculano-Houzel.

Everyone who has watched crows carefully knows that they are intelligent birds. A friend once told me that if he went outside and pretended to target crows with a broom handle as though it were a gun, the birds would not move, but if he went outside with an actual gun, the birds would scatter. There is a video of a crow repeatedly sliding down a snowy roof, as well as another video of two crows sliding and rolling on a snow-covered car, which looks like the kind of intentional play behavior we associate with mammals (there are many similar videos of crows playing). I’m sure everyone has their own anecdotal account of avian intelligence.

Now we have something more than anecdotal evidence for corvid intelligence. The articles in Science report, respectively, an experiment that implies sensory consciousness and anatomical features of the corvid brain that are analogous, but not identical, to the mammalian brain. Herculano-Houzel notes that it has long been said that birds have no cerebral cortex, but she goes on to explain that the avian pallium derives from the same embryonic developmental structures from which the mammalian cerebral cortex derives. (She cites “A developmental ontology for the mammalian brain based on the prosomeric model” by Luis Puelles, Megan Harrison, George Paxinos, and Charles Watson, in which the authors argue, “Because genomic control of neural morphogenesis is remarkably conservative, this ontology should prove essentially valid for all vertebrates…” which would include both birds and mammals.)

Similarly, the conventional view has been that the limbic system is unique to mammals, but there may be structures in the avian brain that are homologous to the limbic system. A re-assessment of the avian brain is evident from papers such as Avian brains and a new understanding of vertebrate brain evolution by The Avian Brain Nomenclature Consortium, and Cell-type homologies and the origins of the neocortex by Jennifer Dugas-Ford, Joanna J. Rowell, and Clifton W. Ragsdale, and this re-assessment has been carried back to common ancestors of mammals and birds, as we find in the paper The Limbic System of Tetrapods: A Comparative Analysis of Cortical and Amygdalar Populations by Laura L. Bruce and Timothy J. Neary. All of this points to the increasing complexity and detailed articulation of evo-devo conceptions and the idea of deep homology, such that highly conserved genes produce similar structures—eyes, brains, and perhaps consciousness too—across many different species, even when there isn’t a direct line of descent; we should take this as a memo to similarly examine behavioral evolution from an evo-devo standpoint, but leave that aside for now.

Given the earlier research in the papers cited above, we would not be surprised to learn of further homologies being recognized to hold between avian and mammalian brains, but while there may be unrecognized neural homologies between birds and mammals, the bird brain is quite different from a mammalian brain. The Stacho, et al., paper addresses these different neuronal structures, but they conclude, “Our study reveals a hitherto unknown neuroarchitecture of the avian sensory forebrain that is composed of iteratively organized canonical circuits within tangentially organized lamina-like and orthogonally positioned column-like entities.” In other words, the avian pallium exhibits an architecture of layered neurons, and columns connecting the layers, which is a structure than has long been understood to characterize the mammalian cerebral cortex. The two structures are distinct in detail, but display overall similarities in the way in which iterated and interconnected neural circuits are arranged.

The Nieder, et al., paper approaches avian intelligence through behavioral research rather than through anatomy, although the stimulus response experiments are traced to a single neuron, so that there is an anatomical component to this research as well. The authors write:

“We trained two carrion crows (Corvus corone) to report the presence or absence of visual stimuli around perceptual threshold in a rule-based delayed detection task. At perceptual threshold, the internal state of the crows determined whether stimuli of identical intensity would be seen or not perceived. After a delay, a rule cue informed the crow about which motor action was required to report its percept. Thus, the crows could not prepare motor responses prior to the rule cues, which enabled the investigation of neuronal activity related to subjective sensory experience and its lasting accessibility.”

Nieder, et al., recognize the philosophical problems involved here by citing the famous paper by Thomas Nagel, “What is it like to be a bat?” They add, “…whether pure subjective experience itself (“phenomenal consciousness”) can and should be dissociated from its report (“access consciousness”) remains intensely debated.” And so it is.

The Nieder, et al., paper, though it appears in the same issue of Science as the Stacho, et al., paper, is entirely independent of the Stacho, et al., paper, and the former repeats many of the traditional assumptions about the absence of a cerebral cortext in the avian brain. However, knowing what is now shown in the Stacho, et al., paper, and its earlier anticipations, we should not be at all surprised to find both empirical evidence of consciousness and mechanisms of sensory consciousness in birds that are apparently parallel to those of mammals. Our common terrestrial ancestry, and the DNA all life in the terrestrial biosphere shares, seems to count quite significantly toward cognitive similarity, and points to the possibility of an evo-devo cognitive science.

Both Nieder, et al, and Herculano-Houzel discuss the phylogenesis of consciousness: since mammals and birds have a common ancestor about 320 million years ago, this raises the question of whether the common ancestor to both birds and mammals had some rudimentary form of consciousness, or whether consciousness appeared later, independently emerging in both birds and mammals. (I just discussed what I call the phylogenesis of mind in my newsletter 101.)

On the one hand, accounting for consciousness by the deep homology of highly conserved genes closely ties consciousness to the terrestrial biosphere and its contingent processes; on the other hand, multiple distinct biological mechanisms that realize consciousness suggest that consciousness as an emergent complexity is not exclusively reliant upon the specific biological mechanisms and neuronal architecture of highly developed mammal brains, which is the way in which we ourselves are familiar with consciousness. This in turn suggests that other intelligence in the universe could also be conscious intelligence something like we know from our own experience, and a mind constrained by the reality of consciousness as we know it would be at least partially understandable by us—and we would be at least partially understandable by an alien conscious intelligence—in virtue of shared consciousness, even if the biological underpinnings of consciousness were distinct in each case.

We cannot communicate via (grammatically structured) language with other forms of life on Earth, but we can and do communicate with them in terms of conscious interaction with other conscious beings. Even a biological relationship as adversarial as predation, for example, is mediated by consciousness—both beings seeking to survive, while one listens and watches in order to detect a threat, while the other waits and watches for a moment to pounce. (I earlier made a similar point in A Sentience-Rich Biosphere.) This ecological relationship is mediated by a conscious relationship between predator and prey, i.e., the shared consciousness of both predator and prey. Similarly, communicative relationships between ourselves and other beings that evolved in other biospheres, such as is posulated as the basis of SETI, could have a similar communicative structure based in shared consciousness that mediates an ecological relationship (with “ecological” here understood in a cosmological sense), even if it should turn out to be the case that human and alien minds are incommensurable and communication in the sense of shared information content is not possible (i.e., if what Freeman Dyson criticized as the “philosophical discourse dogma” is, in fact, an unsupported dogma).

These findings regarding avian consciousness should also be of great interest to artificial intelligence researchers, in so far as artificial intelligence can be conceived (even if it is not always conceived) as machine consciousness. Machine intelligence that is not conscious would be alien from human intelligence in a fundamental way (in the same way that an extraterrestrial intelligence what was not conscious would be more alien to us than a conscious mind). Artificial intelligence that was the result of machine consciousness, like an alien consciousness, would have at least something in common with us, increasing the possibility of our having aligned interests (i.e., the constructed AI more likely to be friendly AI).

Knowing that consciousness in both avian and mammalian brains may be associated with layered neural structures, engineers of computer hardware involved in artificial intelligence might consider constructing an iterated architecture of layered neural pathways—that is to say, layered neural networks—connected every so often by columns, and so producing a different kind of hardware more specifically suited to the emergence of consciousness.

The economic motive for artificial intelligence research is simply to extend automation beyond what automation has accomplished to date, and this is certainly where the most significant economic gains are likely to be found; this research will pay for itself. But the epochal breakthrough in computer science will not appear from the incremental improvement of increasingly “intelligent” expert systems, but from the appearance of machine consciousness, which is something entirely different from what is today understood by “artificial intelligence.” Since artificial intelligence researchers seem to be mostly content writing and re-writing software that runs on more or less the same hardware, artificial consciousness is not likely to emerge from these efforts; machine consciousness will probably require distinctive hardware that imitates the neuronal architecture of biological brains from which consciousness is an emergent.

But suppose that we can isolate the neuronal circuits of consciousness, and reproduce them in hardware form: once we can do this, we can do this at a larger and at a more complex scale than exists in any biological brain. If consciousness is an emergent from iterated layers and columns of neurons, hardware mimicking layers and columns of neurons could be constructed that also serves as an emergent basis for consciousness, and a consciousness that could be far more sophisticated than any biological consciousness, insofar as the technological basis of consciousness could be rapidly streamlined and miniaturized. From such a research program an optimized consciousness could emerge. And not only optimized consciousness, but it might also be possible to engineer qualitatively distinct forms of consciousness that are variously optimized for specific tasks.

Schematic drawings of a rat brain (left) and a pigeon brain (right) depict their overall pallial organization. The mammalian dorsal pallium harbors the six-layered neocortex with a granular input layer IV (purple) and supra- and infragranular layers II/III and V/VI, respectively (blue). The avian pallium comprises the Wulst and the DVR, which both, at first glance, display a nuclear organization. Their primary sensory input zones are shown in purple, comparable to layer IV. According to this study, both mammals and birds show an orthogonal fiber architecture constituted by radially (dark blue) and tangentially (white) oriented fibers. Tangential fibers associate distant pallial territories. Whereas this pattern dominates the whole mammalian neocortex, in birds, only the sensory DVR and the Wulst (light green) display such an architecture, and the associative and motor areas (dark green), as in the caudal DVR, are devoid of this cortex-like fiber architecture. NC, caudal nidopallium.

#birds#mammals#intelligence#SETI#evo-devo#neuroscience#consciousness#philosophy of mind#artificial intelligence#machine consciousness

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Piketty’s Capital and Ideology

This book is a political-economic analysis of several, quite sweepingly broad (from the middle ages up to the present period of hyper-capitalism) historical regimes of inequality, mainly in the West although there are interesting comparative forays to India and Brazil. Piketty uses a very broad brush to depict a tripartite schema of inequality regimes ranging from medieval estates to the ownership/propertarian (aristocratic to haut-bourgeois) regime of the 18-19th centuries, then he goes on to the era of hypercapitalsim (with a significant interregnum of state redistribution- welfarism in the middle of the 20th century.) I said the sweep is broad, but it is also bold, not just in historical terms but also in its highly convincing use of data sets from key states, principally European and the United States, but also significant data from India and Brazil. The study thus gives a convincing statistical analysis of the economic bases of the inequality regimes and relates the regimes to their contemporary state ideologies, tax, revenue and welfare policies.

The point of the book is to relate, therefore, capital (although Piketty does use the term hyper- capitalism, the focus is, as the title states, on capital rather than capitalism in its more Marxist sense – I think on the whole Piketty’s position is Weberian) and the ideologies (as insidious belief systems that have a type of defining power on the dominant forms of policy thinking) coincident with the main inequality regimes.

To my mind this book is somewhat theoretically weak in the area of its second key word – ideology. In many respects the book’s highly economistic analysis would surely have had the better title ‘Capital and fiscal inequality regimes’. Ideology, if it is to be of use theoretically, cannot just be tagged on to economic analysis in the manner of pointing to the historical coincidence of legitimatory ideas – although this is important. But any ideological analysis worthy of the name requires a much more cultural form of approach – ideology has to be seen as a force in its own right with its own forms of ‘data’, concepts, ideas, images, just as economic analysis requires clusters of concepts of finance, fiscal policy etc. Too often in this book ideology is seen as simply a legitimatory and reactive political phenomenon riding the back of economic inequality, in this sense it sometimes has a hint of crude 30’s Marxist understandings of ideology.

This is not, of course, to say that this book is not a great, important, crucially timely work that is a resource for all who need substantive factual backing for their arguments against contemporary trends in states in thraldom to populism, identitiarian (nationalism), tax and ‘fiscal dumping’ policies, what Piketty summarizes as the ‘drive to the bottom’ logics of global capitalism. Some of the strongest sections of the book are in fact on the propetarian regimes of the 19th to early 20th century in which Piketty shows how sacrosanct ideologies of ownership had the effect of stifling more progressive state and social policies. He gives as an example the UK in the 19th century where a propertarian ideology blinkered state policy to the extent that the principals of debts arising from the Napoleonic wars were repaid right through until the first world war to the detriment of national economic development.

Piketty contrasts this to the accelerated German and French debt reductions after the second world war when ‘Debts of 200-2000% of national income in 1945-50 were reduced to almost nothing’ (444-5)

Piketty often uses what at first appear quite hackneyed historical examples, the Democratic Party’s support for slavery, the social-welfarist state in Sweden, the rise of Russian Oligarchs, all quite time-worn now. But he develops these by revealing the facts of their economic underpinnings. And the book is also studded with less well-known examples, such as the extradition of Mexican immigrants from Roosevelt’s United States in the 1930s (228). But nearly always for Piketty the key actor and focus is less social classes than states and it is no coincidence that he gives a primary role for state and federal agencies in his hopes in the final pages of the book for revolutionary reform of the social, welfare and taxation systems of contemporary societies. Piketty, in this vein, often has a nostalgic view of the post- war social democratic reformist states of the UK and European states, particularly France, Germany and Sweden (not, also, forgetting the highly progressive tax policies of the USA in the 1960s):

The significant reduction in inequality that took place in the mid-twentieth-century was made possible by the construction of a social state based on relative educational equality and a number of radical innovations, such as co-management in the /Germanic and Nordic countries and progressive taxation in the United States and United Kingdom. The conservative revolution of the 1980s and the fall of communism interrupted this movement; the world entered a new era of self-regulated markets and quasi-sacrilization of property. (1036-7)

However, he grafts much that is new onto this generally acknowledged view, such as ideas of temporary property ownership, the need to foster progressive taxation at the federal level, the need for deliberative democratic principles as the basis for developing dynamic fiscal rules, particularly required at the regional and global levels of governance (such as the EU) in order to counter hypercapitaist accumulation and competitive ‘drives to the bottom’.

But there are also subtle and confusing lapses or contradictions in Piketty’s analysis. There are minor ones, deriving I think from the unacknowledged but nevertheless clearly Weberian-pluralist political bases of his argument. For example his notes the ‘conflictual socio-political trajectories in which different social groups and people of different sensibilities within each society attempt to develop coherent ideas of social justice’ (454). But then he has, sometimes conscious, but certainly underlying, a Durkheimian ideal of the possibility of an organic social order at the basis of his ideas for reform. This latter ideal might be the basis for new forms of social solidarity to counter old identitarian ideas again on the rise (racism and anti-immigration). But I cannot see how this contradiction between the motive forces of capital and society, of human nature and ideals, can be easily resolved. I am not certain it is something that will easily yield to the deliberative model of governance-technocratic management Piketty essentially adopts.

Other minor flaws in the argument come from the book’s unreflectively liberal view of what he deems ‘secondary’ market transactions. In this Piketty contrasts primary goods and services, such as education, which should not be marketized, and secondary sectors by which he means areas like clothing where:

there is a legitimate diversity of individual aspirations and preferences – for instance, in the supply of clothing or food – then decentralization, competition, and regulated ownership of the means of production are justified. (595)

But the major problem with this book is its lack of a more complex understanding of the concept of ideology. At the start, Piketty signals that he was going to use cultural examples, such as extracts from novels, in order to illustrate the defusing of the ideas underlying inequality regimes into everyday life. But these examples, mainly from novels (an essentially 18th century cultural form) are brief, limited, often footnoted, rather than being intrinsic to the analysis. Piketty needed to have some understanding of the role of the media and state intellectuals (i.e. from cultural Marxists like Gramsci), if the reader was to make the link between capital and ideology. What is needed is a more informed understanding of ideology, ideology as a force in its own right. Too often Piketty sees ideology as arising in a type of ‘logic’ riding on the back of the inequality regimes they coincide with:

We learned that most premodern societies, in Europe as well as in Asia, in Africa as well as in America, were organized around a trifunctional logic. Power at the local level was structured around, on the one hand, clerical and religious elites charged with the spiritual leadership of society and, on the other hand, warriors and military elites responsible for maintaining order in various evolving political-ideological configurations. Between 1500 and 1900, the formation of the centralized state went hand-in-hand with a radical transformation of the political-ideological devices that served to justify and structure social inequalities. (410)

At other times, particularly in the analysis of the cultural influence of the Brahamic domination of ancient India, seen by Piketty in the Manusmriti texts which:

...the authors plainly believed that the time had come to promote their preferred model of society...(313)

Similarly, in criticising the ‘philanthropic illusion’ arising around contemporary billionaires like Bill Gates he fails to relate how elite figures must be seen in terms of the broader ideological currents of the time – in this case, for example, Band Aid.

Nevertheless, Piketty’s book is massively generous in its scope and the depth of its economic analysis of the variations in polices that accompany the historical inequality regimes. His calls for policy reforms in areas such as progressive taxation, basic income, the socialization of ideas of property and inheritance, participatory democracy in the economy, redistributive financing of educational opportunity which are presented on the firm back of substantive economic analysis. It is this, the capital-side of the analysis, in which the reader experiences the book’s most powerful rhetoric – hidden behind Piketty’s restrained, almost prosaic text - the statistical tables and graphs that relentless flow facts after facts recording our historical and contemporary shame.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Big Fucking D&D 4E Rant

Or, ‘That Time Wizards of the Coast Fucked Up D&D’s Lore’

At the risk of raising the spectre of edition war again, I feel like it’s worth going back and exploring that time that Wizards of the Coast fucked over basically all of their lore to chase a trend that wasn’t there. Admittedly this comes with the (begrudged) acknowledgement that quite a bit of of this is likely to be out of date now that fifth edition has been out for a good several years now, but that edition has its own problems and while I’m not really going to touch upon it now, my problems with it are many and numerous.

It should be noted from the outset that this is going to talk about fourth edition in a negative and critical context, but I’m not going to be talking about the rules of the actual game as a game. This is entirely centred on story, worldbuilding and lore, and how those were handled in fourth edition as compared to what came before. That being said, if you like fourth edition, and especially if you like its lore, I would not suggest reading further.

I’m going to go far beyond being critical in this; I’m going to get outright mean.

A shout out must go to Susanna McKenzie (@cydonian-mystery) for input and feedback on this.

I suppose the most important place to start is, in many ways, the beginning, by which I mean my own introduction to Dungeons & Dragons. Mostly because it’s directly linked to the main reasons why I consider the lore to have been ruined, but before I even start off with that, I’m going to have to tell you where the lore was before I can really adequately explain its downfall.

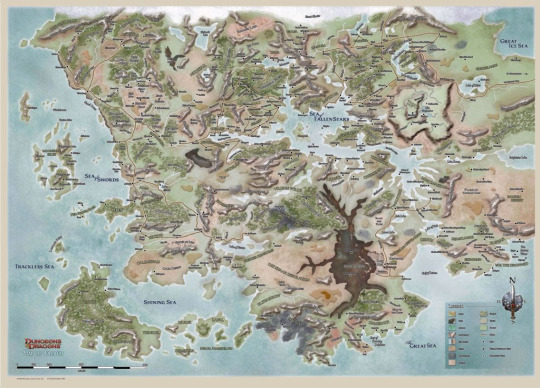

In Realms Forgotten...

Like many people of my generation, I got into Dungeons & Dragons first through the computer based role-playing games. Specifically I started off with various titles by Black Isle and BioWare in the late-90s and early-00s, with stand-outs including Baldur’s Gate, Icewind Dale, Neverwinter Nights, and their sequels. What all of these had in common beyond being Dungeons & Dragons adaptations is the fact that they took place in the Forgotten Realms, one of the more famous settings thereof, and the lore of that world intrigued me far more than the rules alone.

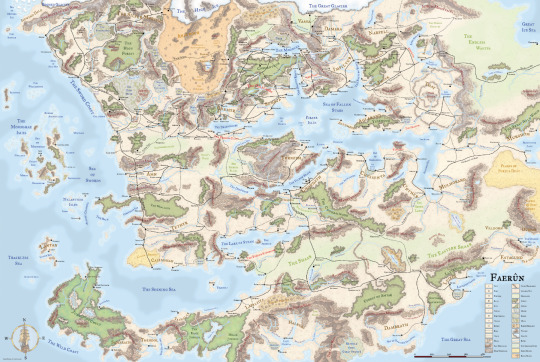

This might not sound like much, of course, to a newer fan for whom the Forgotten Realms, and its central setting of Faerûn, likely feels just like that generic world that D&D just happens to take place in nowadays. But back in the day, it was far more than that.

At the time I was getting into it, local libraries and bookstores carried bestselling novels set in the worlds in question, so I could pick up a novel based around various characters who appeared in the games, like the drow ranger Drizzt Do’Urden or the powerful wizard Elminster. There was also this huge encyclopedic book of geography and deities and the history of the world, with a big fold-out map which is still stuck up on my bedroom wall even after moving house three times. It was perfect fodder for my young nerdy fangirl self to develop full-on special interests in this stuff.

And the level of detail and lore and nuance in the world and its peoples was immense, with even the tiny and obscure bits of the setting earning massive amounts of unique lore. The result was a world that felt like it was alive, vibrant, and lived-in. Like real people could live there, with colourful heroes and villains to encounter.

This, I think, was the unwitting downfall of the Forgotten Realms, but I’m getting ahead of myself because this is really only step one, and Realms are really only one part of it. There are in total three of them, and I’ll be going through the baselines of each of them before we move on.

Out to Planescape

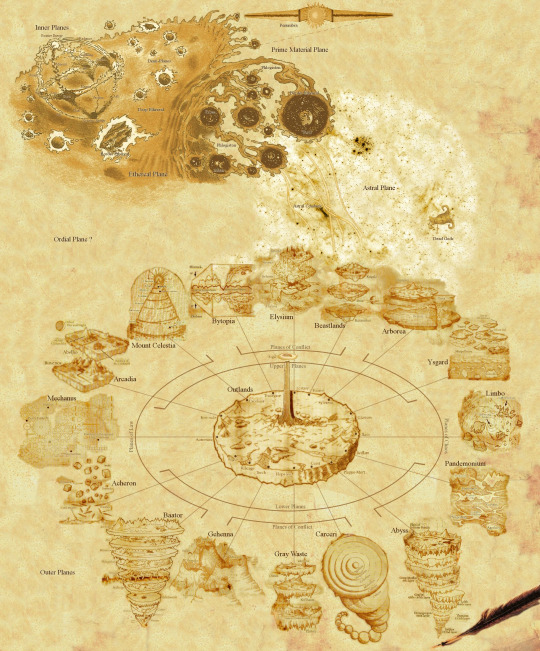

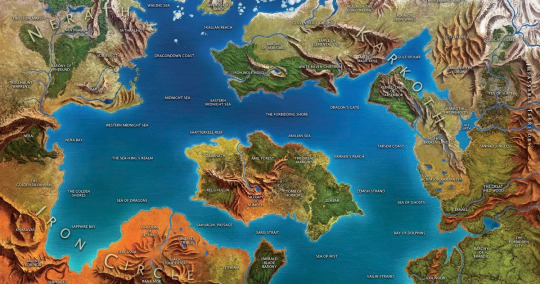

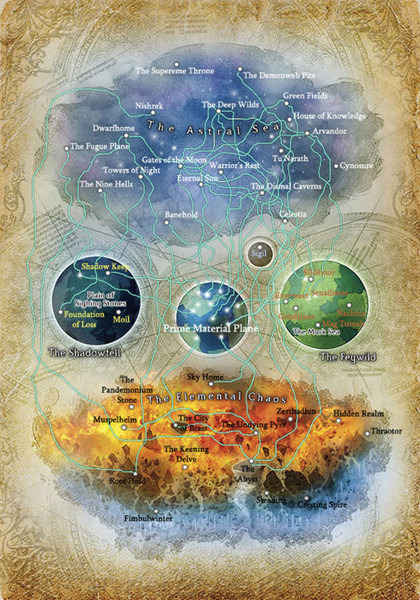

If you’ve read through the core books for fifth edition, there’s a chance you already have some degree of knowledge of Planescape and what it is. Or more precisely you know about the core structure of the Dungeons & Dragons multiverse; the Great Wheel. A series of elemental inner planes and transitive planes, with a ring of sixteen aligned outer planes representing various combinations derived from the axes of law versus chaos, and good versus evil, centred around a neutrally-aligned central plane.

At the centre of this central plane is an infinitely tall spire, atop which lies the famous torus-shaped city of Sigil, the city at the centre of the multiverse. There are a few more bits to it than that, and there are actually differences between how it once was and how it now is. For instance back in the day, there was no such thing as the Feywild or Shadowfell, and neither one was present in the original structure as laid out in 1987’s Manual of the Planes for AD&D.

Once again, to say that this is barely scratching the surface of the planar cosmology and its general meaning to Dungeons & Dragons lore would be a gross understatement. It wasn’t long after the publication of the above book that there was a new campaign setting created called Planescape, which would centre entirely upon this cosmology and build it into the lore. This is where the city of Sigil was introduced, a place of weird concordance where demons, angels, and creatures far, far stranger than either rubbed shoulders in the street, and only the watchful eye of the mysterious and powerful Lady of Pain kept things from erupting into all-out war.

It was a world of disputes, where a myriad of factions representing various philosophical concepts went toe-to-toe with one another. All wrapped up in a tone not unlike a strange mix of China Miéville and Charles Dickens, with the local dialect and thieves cant giving a unique flavour that no major campaign world outside of Planescape can really manage.

Perhaps the most famous and lasting contribution that this setting has was the tieflings, aasimar, and genasi, referred to collectively as the planetouched. These were born from a mix of planar interaction with human bloodlines, in particular through the very old fashioned way that any hybrid is created, which is perhaps why tieflings were the more common. They carried the blood of fiends, and most commonly demons by way of ancestors who reproduced with succubi and incubi, though no two tieflings looked especially alike, with variable and strange features.

I’ll be getting back to these later, but suffice it to say that Planescape was an interesting outlier setting, far stranger and more creative than almost anything else in anyone’s catalogue. And it forms the second part of our list of ruined lore.

And back down to Greyhawk

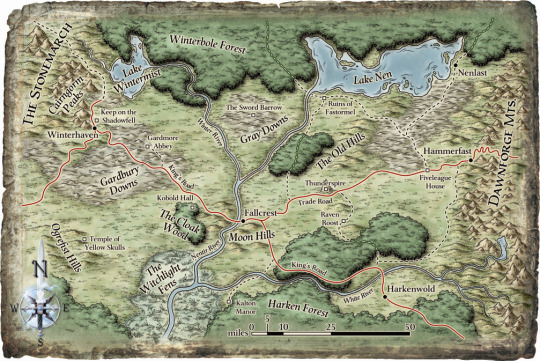

There’s a very good chance that your knowledge of Greyhawk is pretty limited, because while one could make good arguments for the above only just being ruined when fourth edition came around, there’s a lot to be said about how Greyhawk’s been the forgotten cousin for a while now, though to the credit of the current staff at Wizards of the Coast, they did just release a full-on Greyhawk adventure with Ghosts of Saltmarsh.

Introduced in the late seventies and early eighties, the World of Greyhawk, taking place on the fictional planet of Oerth and in particular on the subcontinent of the Flanaess, was the personally created campaign setting of Gary Gygax himself. While not as detailed as the Forgotten Realms, nor as interestingly out-there as Planescape, it is nonetheless a pretty cool world overall with a fun pulpy atmosphere that gives it its own sense of weight and nuance.

However, after Gary Gygax left TSR back in the 1980s, some later creators took it upon themselves to more or less mock his legacy overall. Nonetheless it remains a popular location for fans and creators, and towards the late third edition there was a lot of good work done in reviving it, such as with a series of adventure paths published in Dungeon Magazine in the form of Shackled City, Age of Worms, and Savage Tide, and following that a big adventure module in the form of Expedition to the Ruins of Greyhawk.

Since it’s the most basic element, let’s start with how they treated Greyhawk...

Strip-Mining the Free City

To say that Wizards of the Coast ruined Greyhawk would actually be inaccurate because, to a degree, they didn’t actually use Greyhawk. At least, not fully.

What they did instead was create a ‘new’ campaign setting, sometimes called the Nentir Vale, that used a few scavenged and cherry-picked Greyhawk deities and also a whole selection of adventures and locations previously specific to Greyhawk. Notable examples of such on the larger worldmap seen in the boardgame Conquest of Nerath included the Tomb of Horrors, the Vault of the Drow, and the Temple of Elemental Evil.

The resulting setting wasn’t Greyhawk, but had enough pieces that it felt like an insult to it. Often having those elements be modified in such a way that they felt like mockeries rather than the original concepts. A big part of why that felt like mockery is of course that Nentir Vale, or the Points of Light setting as it was sometimes referred to as, didn’t really exist as its own fully-fledged world. There wasn’t really a campaign setting book, or much detail on anything outside of a few small locations.

This is a relatively small part of what Dungeons & Dragons 4th edition did wrong, but it’s a small taste of what’s to come. However as seen with the Greyhawk conversion guidelines for many adventures, and even the release of the recent Ghosts of Saltmarsh, Greyhawk itself seems to have survived while the Nentir Vale remains almost entirely forgotten except for mentions of the Dawn War pantheon on one page of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

It seems like Wizards of the Coast realised it was a bad idea.

‘The Great Wheel is Dead!’

As we go back out to Planescape, we notice that — much like Greyhawk — it also isn’t there, as the entire cosmology and its thematic importance has been replaced with something so radically different that it’s practically a complete replacement. Just about the only part of Planescape that was kept was Sigil itself, but as shown repeatedly in the fourth edition version of Manual of the Planes, they obviously didn’t understand either Sigil or the Great Wheel in any real way.

I’m not going to talk about the World Axis much in direct terms, but instead more the mindset that was taken with regards to Planescape’s Great Wheel. Now this requires something of a diversion into an old pre-fourth edition preview document, and how it handled the Great Wheel and old materials.

The Great Wheel is dead.

One of my mantras throughout the design of 4th Edition has been, “Down with needless symmetry!” The cosmology that has defined the planes of the D&D multiverse for thirty years is a good example of symmetry that ultimately creates more problems than it solves. Not only is there a plane for every alignment, there’s a plane between each alignment — seventeen Outer Planes that are supposed to reflect the characteristics of fine shades of alignment. There’s not only a plane for each of the four classic elements, there’s a Positive Energy Plane, a Negative Energy Plane, and a plane where each other plane meets — an unfortunate circumstance that has resulted in creatures such as ooze mephits.

The planes were there, so we had to invent creatures to fill them. Worse than the needless symmetry of it all, though, is the fact that many of those planes are virtually impossible to adventure in. Traversing a plane that’s supposed to be an infinite three-dimensional space completely filled with elemental fire takes a lot of magical protection and fundamentally just doesn’t sound fun. How do you reconcile that with the idea of the City of Brass, legendary home of the efreet? Why is there air in that city?

So our goals in defining a new cosmology were pretty straightforward.

• Don’t bow to needless symmetry!

• Make the planes fun for adventure!

The ‘impossible to adventure in’ mindset towards the Great Wheel is entirely bullshit, which I think is best highlighted in the passage on the City of Brass. How can a plane of pure unchanging fire without variation also have a city-state? Maybe, just maybe, it wasn’t without variation and they’re making shit up to justify their own nonsense.

The arrogance here is nothing short of infuriating. It typifies everything about the approach that Wizards of the Coast was taking towards Dungeons & Dragons at the time, and can only really be described as destructive.

There was nothing but an arrogance and often gleeful disdain for previous editions. Along with declarations of how it was so much better now, with the old version being bad for some reason despite that version having generated a huge fanbase, and a critically beloved computer role-playing game in the form of Planescape: Torment. And as with Greyhawk, they’ve done what they can to reverse that. The only elements of the new cosmology that remain are the Elemental Chaos as an in-between for the Elemental Planes, the Feywild, and the Shadowfell.

Wizards of the Coast once again seemed to realise where they were going wrong, and this is basically a recurring element of fifth edition.

Unfortunately, the World Axis and Nentir Vale aren’t really where the majority of my frustrations lie.

The Shattered Realms