#ineffable secretaries

Text

So I uh… *throws this here and runs*

#good omens#my art#edit#the little Mermaid#Disney#ineffable administrators#angelfish#ineffable secretaries#archangel michael#Dagon#fanart

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just to see

I'm like them both just want to see what people think

#good omens dagon#good omens rp#fileflies#ineffable secretaries#ineffable administrators#michael x dagon#dagon x beelzebub#good omens beelzebub#good omens michael

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

@rareomens

Day 1: Michael x Lucifer

I headcanon that Lucifer designed the secretary bird after Michael. She loves it <3

#good omens#lucifer good omens#michael good omens#ineffable rivals#michifer#rare omens#rareomens2024#good omens fanart#secretary bird#v2 Luci

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Aziraphale would be a dove’ FALSE Aziraphale would be a secretary bird because they are snakes natural enemies and also they slay

#good omens#please google a picture of a secretary bird and then imagine it saying#‘oh dear’#Aziraphale#ineffable husbands

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey this might be kinda weird but i just got out of the psych ward and i’m really not doing great post discharge and need something to cope

i was wondering if you knew of any psych ward/mental health hospitalization au ineffable husbands fics?

thank you for these lovely fics you share <3

Here are a few fics along these lines, but please mind the tags on most of these!...

Asylum AU by ZiraD (M)

Crowley was closed in this asylum for ages after his parents sold him in a need of money with a mad doctor who did experiments on humans. This asylum wasn't like the normal ones...this was an old abandoned building. Big enough to get lost in it if you didn't pay attention and memorize your way around. One day Crowley managed to run away from his room and from that day on he's been hiding from the doctor and killing anyone who dared coming closer to him.

One day a new boy was added to doctors collection which Crowley didn't know about he had a beautiful blue eyes and a pale skin with cherubic features...he looked like an angel...but one day the doctor wanted his beautiful eyes... wanted to take them out and keep them in a jar for himself and maybe use them later.

But what will happen next? Is there a way for them to survive? We shall find out and see

Doubtful Hysteria by Lord_O_Googoo (T)

Is madness a divine punishment? Is wanting the vote as mad as Victorian doctors would have you believe? Aziraphale becomes invested in these questions, especially as they pertain to her new friend, Emily. Meanwhile, Crowley attempts to tempt Aziraphale to leave the wretched place behind.

I Want To Break Free by TakeItEezy (M)

Anthony Crowley, a drug addict, doesn’t like being put in a box, especially if that box included doctors and psychologists. However, Solomon Aziraphale makes him realize that this could be his chance to break free from the life he had before. But, will Aziraphale be stuck in his old life forever? Would he ever allow himself to get better?

The Protector and The Prophet by ranguvar82 (M)

Ever since he can remember, Anthony Crowley has been plagued by horrific nightmares of the world ending. His twin Anathema tries to help him, but when they are sixteen, their fanatically religious parents have him committed. Sixteen years later, a severely traumatized Crowley returns home with Ana, still plagued by the nightmare. Then a man shows up, claiming to be an angel, and Crowley's life will never be the same.

Aziraphale had a deal with Heaven. Leave him alone unless it's important, and well, a True Prophet is important. The angel's not fully sure what to expect, but the brilliant, beautiful, and traumatized Crowley is definitely not it.

Damn these pesky feelings.

The Secretary by tuddles (E)

Fresh out of a phycological institution, a tormented Anthony Crowley tries to deal with his issues of self abuse as he looks for his place in the world.

Things take an interesting turn when he sees a vacant job opportunity to be a secretary for a local bookstore.

- Mod D

#good omens#ineffable husbands#ineffable wives#mental health#mental institution#major archive warning#mind the tags#mod d

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unnamed Duke of the Hell, part 2

My thinking about The Infernal Lady is getting a sequel unexpectedly. After comment of @embracing-the-ineffable I had checked whether Lady participated in demon invasion. And she did.

She and her unnamed colleague from the Dark Council (so he is definitely not Ligur) are staying on either side of Eric.

Top view. What a luxurious ginger braid. And it looks like her duke compaion has black and grey split hair. Does anyone have an idea about what animal is he associated?

@yronnia gave me a good idea that her look might be a reference to unknown deity or spirit because of the unusual crown. Her long braid coupled with crown that looks like kokoshnik suggest slavic goddess as a variant. I can also suggest reference to mexican Calavera with a wreath. But in both cases her black strip on the forehead seems to stand out from the image.

Also the Lady has a little hat pin on her halo.

And at last they both will be discorporated. Even Hastur has done it with more style in a burning car.

What an inglorious and strange fail for dukes, isn't it? I am still convinced that they are not ordinary demons or secretaries. You will not call secretaries as "their maleficences". Dukes' presence on Earth can be explained by the fact that they both were witnesses of Furfur's endeavors and now they are verifying that Furfur was right. Though they could have realize that 4 years ago..... But Dukes of the Hell totally don't need to attack themselves.

...unless they were demoted. What if Hell wipes memory of guilty demons as the Heaven does? And a bottom of the barrel demon equals to 38th degree Angel scrivener. I will not imagine any reason of demoting - it might be literally everything - and I am writing it just as a possible version. On the other hand they would change their clothes after demotion, but this doesn't happen. Anyway i really don't want my Lady to be excluded from the Dark Council, she is soooo beautiful.

#good omens#good omens 2#good omens demons#dark council#good omens hell#good omens meta#go2#go2 meta#good omens headcanon#demon#demons#good omens theories#good omens theory

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOOK AT THEEEEM😭 (I wonder what this ship can be called...maybe ineffable secretaries? ineffable directorate? idk, any variation?)

#good omens#good omens 2#good omens fanart#good omens spoilers#shax good omens#furfur good omens#shax#furfur#furfur x shax#shax x furfur#fanart

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

“April 9th, 1995

Was reported in the Modesto Bee today that McNamara said that the war in Vietnam was a “mistake”.

Will some paper report on April 9, 2025 that 3 strikes was a mistake? That hopelessly incarcerating drug addicts was a mistake? That a war on the poor was a mistake? That turning our heads from their plight and blaming them was a mistake?

The rich in this country violate the social contract we have with each other..that, when you are down, I will hold you up.

Because my house is your house. 100 guns won’t keep you out. But, 100 acts of benevolence and of kindness might. And, ‘might" is worth the risk.

Tomorrow, I will receive an English lesson. Larry (my 3 strikes client) and Governor Pete Wilson, et, al., team up to teach me the true “mean”ing (I underscore “mean” spirited) of the words arbitrary, ironic, exclusionary, outrageous, blind follower, McCarthism, Hitler, Anger and disbelief.

I’m getting a strange feeling tonight that some miracle has happened in the case—

Whatever it is, it’s good and uplifting.

I can feel it moving up and through me. It’s ineffable.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

April 10th, 1995. A Monday.

(Apparently, the day Larry was to be sentenced to serve 25 to Life. note: 1/29/2023)

Well, Larry, my client, leg bailed. Bench warrant $50,000. What a fucking farce. (His sentencing hearing) 25 to life for four grams of meth.

Sickening little political games.

And, I hope Larry runs far and runs fast and gets away forever and never returns to this hellhole.

And, I counseled a man in the jail today who, in the act of pouring coffee, was ripped down his face by a fellow inmate using a tooth brush imbedded with a double razor. The attacking inmate was trying to make a name for himself pre prison by brutalizing a fellow prisoner . Shocking.

Like Pete Wilson trying to make a name for himself with 3 strikes. He rips the soul.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

4/18/1995

A public defender secretary said today that she read 3 strike lawyers go through a mourning process.

How true.

And, it was such a relief to finally find someone who acknowledges it.

End of entries.

Note:

"Leg Bail" means that Mr. Barrick did not show up for his court date. It is a common termed used both in court and by law enforcement.

#journaling#journal#criminal defense#3 strikes#4/9/1995#leg bail#25 to life for four grams of methamphetamine

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

OT+: #2 + Lucia x Crowley x Aziraphil?

Pairing: The Ineffable Three (Luci Evans + Crowley + Aziraphale).

Prompt: A coming home to the sight of B & C asleep in each other's arms on the couch, and it warms their heart from OT+ Prompts.

Warnings: Kissing, mentions of food and eating, mention of past misogyny.

(A/N: Thank you so much for this, Hannah, and I hope you enjoy this!!)

LUCI COULDN'T REMEMBER THE LAST time her workday had felt as long as this one had. Typically, she loved her job; it paid well, she wasn't expected to talk to her coworkers (not that they made much of an effort to speak to her, either, as people tended not to notice secretaries), and she usually finished all her tasks early, which left plenty of time for reading or absently scrolling online, doing research on various historical events her boyfriends claimed to have been a part of.

But today had been a day. To start off, her bloody alarm hadn’t gone off and she’d wound up being late as a result of it; only by about ten minutes, but it was rather hard for the company she worked at to function properly when the woman who was expected to run their front desk didn’t show up. Besides that, the cab she’d taken had splashed her with dirty water from the rainstorm yesterday when it had stopped to pick her up, and she knew for a fact that the cabbie had overcharged her but she’d been running too late to call him out on it and had been forced to simply pay what he’d asked for.

And the people - oh, the people she’d had to deal with that day. Were she not afraid to do so after the things she’d experienced, Luci would have sworn to God that the company’s executives had gone out of their collective way to be extra stuck-up and rude to her today. They had done nothing but belittle her and make her feel guilty for not finishing work she hadn’t had time to get done with her significant workload, and one of them, a financial director with a weak chin whom she’d always disliked, had even had the nerve to ask her if this was her “time of the month,” what with how frazzled and frustrated she seemed to be.

Given all of that, Luci didn’t even consider going back to her own flat after she was finally allowed to leave. She was more than happy to trudge into Aziraphale’s bookshop as the autumn sun dipped close to the horizon, newly-bought skirt stained with dirty water around the hem and looking like she was completely done with the world.

Thankfully, the warm atmosphere and smell of old books that hit Luci as soon as she entered the bookshop was enough to put her more at ease. Closing her eyes and allowing a small smile to grace her lips for the first time that day, Luci felt her tense shoulders relax as she listened to her angel’s familiar footsteps bustling toward her from the back of the shop.

“Hello! Welcome to A.Z. Fell and-” Aziraphale began, but cut himself off as he recognized one of his lovers. “Oh, hello, darling. How was work today?”

Peeling her eyes open, Luci fixed the angel with an arch look, gesturing wordlessly to the stains on her skirt and her clearly tired expression as an answer.

“Oh,” the angel said in a soft, sympathetic voice, tilting his head at her. “Not so good, then?”

“That’s one way to put it,” Luci grumbled, shuffling toward her boyfriend and unceremoniously leaning her body into his. Without hesitation, the angel wrapped his soft arms around Luci, moving to rub small circles onto her back.

“I’m terribly sorry, my darling,” he murmured into her ear, and Luci relaxed even further at the sound of his deep, sweet voice. “Would you like me to fix that stain on your skirt?”

Luci was ready to open her mouth and remind Aziraphale how she felt about him or Crowley using their miracles on her belongings if it wasn’t to transport them, but she was interrupted by her other, demonic lover sashaying up to them from the back of the shop.

“Oh, hi, dove, what’s going-” he began, but stopped when she saw her expression and adopted a sympathetic wince. “Bad day?”

“The worst,” Luci replied into Aziraphale’s shoulder, thankfully knowing that Crowley could hear her anyway. “Nothing went right. Kinda over everything right now.”

“Well, I dare say we can fix that,” Aziraphale declared emphatically. Gently nudging Luci off of him, the angel moved his girlfriend into the arms of his other lover, who wrapped his own longer arms around her shoulders without even blinking and pulled her into his chest.

“You want me to tempt anyone for you, dove?” Crowley asked quietly as Luci listened to the sounds of Aziraphale closing up shop behind her. “Make some wankers do something embarrassing?”

“No, that’s fine,” Luci spoke into the fabric of his black t-shirt, taking another second to enjoy the comfort of the demon’s arms before reluctantly pulling away. Frowning, she rubbed firmly at her eyes, something that inexplicably usually made her feel better. “I just kind of want to relax and forget about how awful everything was today.”

“Which is exactly what I plan to assist you in doing!” Aziraphale chirped happily, bustling back from the front of the shop. “Alright, if the two of you could just go and sit on the sofa in the back, that would be lovely.”

Luci, not entirely sure what her angel was doing but not about to pass up the opportunity to sit down after the day she’d had, grabbed Crowley’s hand and led her demon to the soft brown sofa in the back of the bookshop. Crowley followed willingly, flopping his long-limbed self down onto the sofa cushions and holding out his arms so that Luci could cuddle up to him.

“Right then,” Aziraphale said determinedly as Luci snuggled into her demon lover’s long, comforting arms. “Now, I am going to go and collect some takeaway from that Thai place you’re so fond of, darling, but before I do… would you allow one of us to miracle you into some sleepwear?”

Half sitting up from Crowley’s embrace, Luci furrowed her brows and began to protest Aziraphale’s offer, but the angel cut her off with a gently raised hand.

“I know your objections to miracles being used on your possessions if it isn’t for transportation,” he said gently. “And I respect your boundaries, I swear that I do. But given that this would technically be transportation of your clothing, and that it might help you feel more comfortable than you would in those work clothes… would you be opposed to making an exception this one time?”

After a moment of debating silence, Luci let out an exaggerated huff and fell back onto Crowley’s chest. “Alright. This one time, and only because I don’t have the energy to go back to my flat and it’s going to be very hard for me to relax in a blouse and pencil skirt.”

“That’s the spirit, dove,” Crowley said cheerfully, then waved a long-fingered hand in the air over Luci’s body. There was that familiar moment of feeling a small change in the fabric of the universe, and the next second Luci felt much softer fabric on her skin than had been there a moment ago. She looked down to find herself clothed in her favorite lavender pyjamas, the tank top and capris-length pants pleasant against her skin.

“Splendid,” Aziraphale chirped happily. “Now, I’ll head out and see if I can’t scrounge up some Thai delicacies, and Crowley, you keep our dear Luci company, won’t you?”

“‘Course I will,” Crowley replied as Aziraphale swept his coat off the back of an armchair. The angel slid the old coat over his shoulders with the usual flourish, shuffling over to the couch to exchange a peck on the lips with Crowley and place a kiss on the top of Luci’s head before heading out of the shop.

After Aziraphale had left and the ringing of the bell over the shop’s door had faded into the air, Luci allowed herself to revel in the peaceful silence of the moment, cuddling closer into Crowley. She hadn’t thought she was tired when she’d left work, just frustrated and worn out, but now, surrounded by the cozy atmosphere of the shop and her demon’s comforting arms, she could feel her eyelids begging to be shut, the blissful darkness of dreamland beckoning her with every centimetre the lids drifted together.

Crowley’s gentle fingers began to card through her hair, and she let out a contented hum, sleep drawing her even further down as she enjoyed the relaxing action.

“You take a little nap if you want, dove,” the demon murmured, ceasing the movement of his fingers only long enough to press his lips against her hair. “Seems like you need it. I’ll wake you up when Aziraphale gets back, alright?”

“‘M fine,” Luci mumbled, even as her eyes finally gave in and closed all the way. “‘M not that tired.”

But the next moment, she had fully entered into the comforting darkness of sleep’s realm, so she supposed that was a big fat lie.

♡♡♡

Almost exactly a half an hour since Aziraphale had left the bookshop, he returned to it, several takeaway bags in hand and ready to enjoy a nice, leisurely supper with his two loves. He found them both asleep instead.

The demon and the human were both still curled up together on the sofa, their peaceful features illuminated by the soft golden light coming from the shop’s various lamps, but now they were both very clearly resting, faces slack with the utter peace of rest and chests rising with deep, rhythmic breaths. Crowley’s arms were still wrapped securely around Luci’s waist, but somehow she had maneuvered so that her chest was half pressed against the demon’s, one of her own arms draped across his thin torso. Her face was squished sideways against his shoulder, in a way that Aziraphale was positive would leave indents on her cheek when she awoke.

Smiling softly at the sight of his two lovers curled up and peaceful together, Aziraphale shuffled upstairs to the small flat above the bookshop, taking care to be as quiet as possible and not wake his loves. Moving into the flat’s tiny kitchen, the angel opened the old oven and slid the bags of Thai takeaway into it; they could be saved until Luci and Crowley were finished with their little nap.

After that task was completed, Aziraphale moved quietly back down to the reading area at the back of the shop. Luci and Crowley were still peacefully asleep on the sofa, so the angel merely picked up a random book from a nearby pile and settled down into the armchair to read.

He may have had no desire to sleep himself, but that did not mean he couldn’t relax, let his two lovers have their rest, and revel quietly in the fact that the three of them were content to be cozy together, in the soft golden glow of bookshop lamps.

General Taglist: @hiddenqveendom, @auxiliarydetective, @foxesandmagic, @artemisocs, @reyofluke-ocs, @endless-oc-creations, @stanshollaand, @ginevrastilinski, @luucypevensie, @arrthurpendragon, @fakedatings, @impales, @claryxjackson, @dancingsunflowers-ocs, @ocappreciationtag.

#my ocs#oc drabbles#ot3: on our own side#ch: luci evans#oc: luci evans#ocapp#ocappreciation#ochub#allaboutocs#fyeahgoodomensocs#good omens oc#queerocs#fyeahocsofcolor#ship: the ineffable three

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“He was in hiding, until suddenly he wasn’t”

Nate frowned at the letter, written in uniform and nearly inhuman script. Waste of a favor, really. Jon’s Secretaries were ineffable and, from Nate’s repeated ill-advised experience, undefeatable. Even if he’d phrased his question in minute detail they would’ve probably returned an extensive essay with net-zero information.

This office was temporary, hollowed out of a storage room. It didn’t have anything close to an address which wouldn’t stop Nevermore from contacting him. The suited young man (jacketless, loosened black tie, red shirt) stared at the letter on his desk. The best he could glean was that someone had been trying to track down Jon and, according with the gift that appeared on his desk, Jon had hidden out in the Arctic and did mineral surveys while on the move.

Fine. He took his Sidearm, the heavy wrench, and grabbed a pair of vacuum tubes to put on top of the stack of mineral deposit documentation. Wires ran from the tubes to bits of tech, eventually hooked to a polished mirror.

Cellphone signal wasn’t working, so he’d do this the hard way.

@jonvandernoorde

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Originally drew the first one for Father’s Day but couldn’t leave the Moms out so here you go. Cringe on Main.

#good omens#my art#digital art#ineffable husbands#ineffable bureaucracy#ineffable administrators#ineffable secretaries#ineffable parents#ineffable children#good omens oc#good omens fanchild#Aziraphale#Crowley#Archangel Gabriel#Beelzebub#Dagon#Archangel Michael#Joan of arc#Catherine of Alexandria#Margaret of Antioch#Marina of Antioch#fankids#good omens fanart#Aziraphale x Crowley#Beelzebub x Gabriel#dagon x michael

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

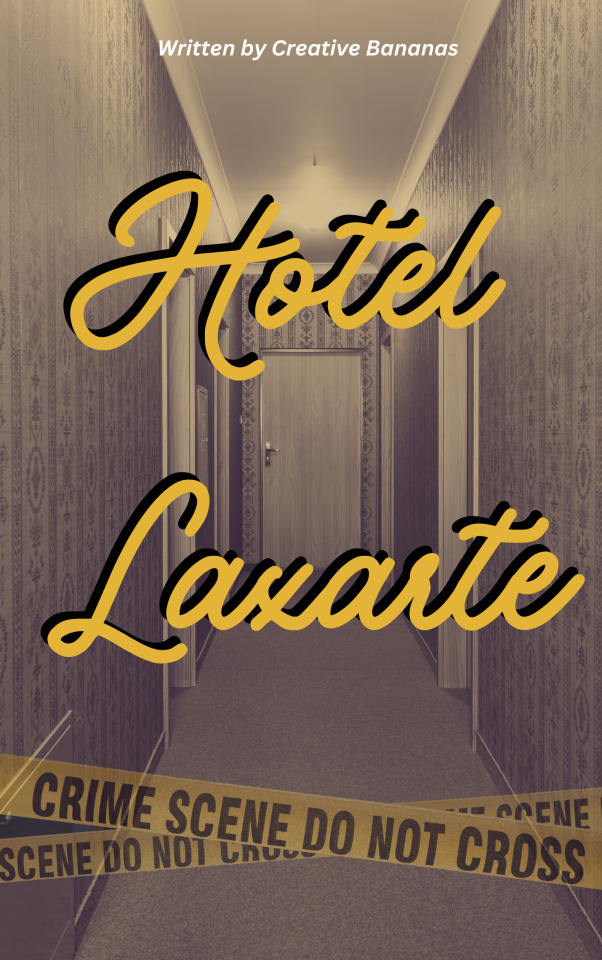

HOTEL LAXARTE

Synopsis

The story takes place in a remote hotel where our protagonist is taking a vacation after his retirement. This is supposed to be a sweet and relaxing vacation but suddenly a horrifying accident happened! A famous good-natured business tycoon is found brutally chopped into pieces with multiple bruises around his body. Who is the killer and what is the motive for his brutish death?

Character Profile :

Benjamin "Ben" White - A good-natured business tycoon who loves interacting with people. He mouses his skills in talking so that he can gain more friends to play and talk to. He is also a womanizer. He is found brutally chopped in his bathroom.

Cathy Zegarra - A beautiful blonde woman who is Benjamin’s secretary. She is very sophisticated and many men are fighting to claim her for themselves. She has an unknown background.

Gwaine Tyrell - A very loud and extroverted 17-year old boy who loves crime books. He is considered as one of the types of people that will make you happy and laugh when you see him. Thomas is kind of fond of him because of his stories especially about murders. He is the first person who sees the body when he goes to Benjamin's room because the man promised that he will give him one of the limited edition Sherlock Holmes books.

Wade Shepherd - One of Benjamin's competitors. He despised Benjamin because he knew what was happening behind the man's toothy grins. One of the major suspects.

Dr. Corlys Lannister - Benjamin's doctor. He is a timid person. He is always standing behind Benjamin because he thinks that anytime something bad will happen to his patient.

Setting

Hotel Laxarte is located in Berlin, Germany. It was built in 1925 where it was a difficult and unstable time for Germany. As well as having to come to terms with the Treaty of Versailles' punishments, it was a time of invasion, economic decline, rebellions but also a huge growth in cultural freedoms and political rights. Despite the economic decline, Hotel Laxarte is one of the most famous hotel for all aristocrats in that time. Many tourists are still fascinated by the country and use the hotel as their temporary staying place.

The hotel has almost 500 rooms, and all of them have a bathroom where the guests can shower themselves. It has a lobby, recreational room, restaurant, swimming pool and many more facilities where the guests can relax themselves. The hotel was deemed as a grand hotel until in the late 80s. The Berlin wall fell and many grand hotels opened. The great Hotel Laxarte had been deserted and almost all of its patrons left it. The bustling crowd before became quiet. Our main character, Thomas Callahan, decided to celebrate his retirement in this once grand hotel. But something unexpected happened.

Time

Year 1990

January

Morning

Scene 1 :

(the sound of heavy and fast footsteps)

[Gwaine is running, panicking about what he just saw earlier]

GWAINE: (knocks heavily) Mr. Thomas! Mr. Thomas!

[Mr. Thomas on the other side just woke up because of the noise; Gwaine’s knocking and calling can still be heard in the background]

MR. THOMAS: Ugh, It’s still early in the morning and I didn't order any service! What is that noise all about? (says angrily)

[Mr. Thomas opens the door; reveals Gwaine]

MR. THOMAS: You’re Gwaine Tyrell, right? What brings your ineffable enthusiasm here, early in the morning? My ears are all yours for your new ideas. I admit that I enjoyed our topic the other day, but I think that this is too early for that conversation.

GWAINE: Now is not the perfect timing, Mr. Thomas. I know you’re already retired, but I saw Mr. Benjamin White in his room, dead. (says in a slow voice yet with conviction)

[The two hurriedly went to Benjamin’s room]

MR. THOMAS: You saw the body?

GWAINE: Yes, I was going to meet with Mr. Benjamin as he promised to give me a Sherlock Holmes Boo—

(loud scream from the hotel staff)

[Mr. Thomas and Gwaine entered the room, the neighboring rooms also heard the scream and gets out]

CATHY: Oh my god~ (while bawling and covering her mouth)

[Cathy is crying]

(The room was filled with crying and the sound of murmurs; and puking in disgust)

WADE: This is so brutal. They whipped and chopped his body? I can’t take this. (immediately goes to the door to left the room, while gagging)

CATHY: Whoever did this is a demon. A normal person cannot do this brutality. Can someone please cover this body? I do not want to see it again. I don’t think I can have a good sleep after seeing a mutilated body. What if something like this happens to us too? (shaking) I want to go home. (sobbing)

[Dr, Lannister goes to Cathy’s side and hugs her tightly to comfort her.]

Dr. LANNISTER: We should catch this criminal. We can’t let him get loose or else we are the ones who are going to suffer. I remember you Mr. Wade having an argument with Mr. Benjamin last night. Maybe it was you who did this murder?

[They are all looking at Wade with skepticism]

WADE: That is a high accusation good sir, I have you know that I could sue you for that, I'm a man of high class, I know not of this brutality.

DR.LANNISTER: Who knows?

[Dr, Lannister supported Cathy to walk and turn away from them. A subtle smirk can be seen while he is walking out of the room.]

Scene 2 :

[Mr. Thomas get his phone from his pocket to call police and 112]

112: Hello!! 112 speaking! What's your emergency?

Thomas: Hello 112, This is Thomas Callahan, retired police officer, There is a murder happened here at Hotel Laxarte. Can you give us an ambulance here as soon as possible?

112: Don't worry sir! I have noted your emergency, but I do not think that our team will be there soon because the snow is blocking the road!!

Thomas: That is so unfortunate to hear. Don’t you think there is another way to get here as soon as possible? People are panicking and scared of what might happen.

112 : I am sorry sir but there is no chance of escaping this snow especially when a snowstorm is going on. We are doing our best to get there as soon as possible but while we are not there, please put the body in another room and lock it. I will contact you immediately if the snow blocking the road is lifted.

Thomas: Thank you and please contact me quickly before something terrible happens again. (ended the call and put his cellphone on his pants’ pocket)

[Mr. Thomas don't have a choice but to sit there and ask the people around the victim]

Thomas: Alright everyone! I am going to interrogate you one by one. Mr. Wade, I will question you first. Let’s go to my room.

[Both of them entered the room. Thomas closed the door and invited Mr. Wade sat in the chair. He poured coffee in a mug and offered it to the man. Mr. Wade gladly accepted the coffee.

Thomas: So Mr. Wade, first of all can you tell me what are you doing in this hotel and what’s your connection with the victim?

Wade: I visited this hotel because I loved visiting famous places and one of my employees told me about this place where I can relax and one of the famous hotels back then. You see Mr. Thomas, places like this have history . For example, this hotel is one of the grand places where all aristocrats stayed. It survived World War 1 and 2. This building is rich in history and I loved listening and learning about them. I just did not expect that old prick Benjamin would be here also. That person is my competitor and the one who stole one of my companies that is very special to me. That company has a sentimental value to me because that is my first business where I poured my blood, sweat and tears and that prick will just steal it from me like it was nothing. (his voice is shaky because of anger and he keeps on rubbing his hands like he is washing it)

Thomas: I understand Mr. Wade. Dr. Lannister mentioned a while ago that you and the victim had an argument last night? Can you tell me what was the reason for this argument?

Wade: Benjamin talked shit about my company, saying that it is just a waste of money and it doesn’t worth a thing. That made me angry and I lost control. I punched him and that’s all. (the rubbing of his hands is getting stronger and Thomas noticed it)

Thomas: Are you sure that’s the only thing you did? Can you tell me your alibi and who can prove it? And you are rubbing your hands strongly, why is that?

Wade: Oh this? (look at his hands and stop rubbing) This is nothing. Just my habit and Yes, I am his competitor and yes, I wanted to kill him so badly, but it doesn't mean that I would do that to him, I still have morals and dignity, unlike him. He is a sadistic person who kills people for amusement. I was just in my room the whole time. The door is locked so no one can prove it.

Thomas: Can you please tell me about the “killing for amusement” you have said about Mr, Benjamin?

Wade: This is just a rumor but some people in his company said that he saw Benjamin shoot a woman naked in the garage of his company. That woman is a daughter of a small company owner. They said that Benjamin did it because the parents of the woman don’t want to sell the company to Benjamin. It is all messed up and I do not want to talk about it. Are we done here? This is getting too long. I have to contact my investors.

Thomas: Okay, you can go now Mr. Wade.

[Wade left the room smiling bitterly]

Scene 3 :

[Thomas goes to the lobby and calls Cathy. Cathy is shocked and nervous but Dr. Lannister comforts her. Cathy and Thomas went to the previous room and commenced the interrogation again.]

[While Thomas and Cathy are in the interrogation room, a fight breaks out between Dr. Lannister and Wade]

Dr. Lannister: THERE IS NO WAY IN HELL, WE ARE GOING TO BELIEVE ON SUCH STATEMENT! You must be the one who brutally killed Mr. Benjamin. We all witnessed how hard you punch him last night

Wade: Oh really? You are brave to accuse someone like me! Don’t act like you do not have a motive to kill that man. I know all the things he has done to you!

Dr. Lannister: You—

[Thomas left the room and interferes]

Thomas: Both of you calm your horses down, we can't just accuse each other of being a murderer without any concrete evidence that proves they killed Benjamin or whatsoever, the thing we could do for now is find the real culprit of this mess before this goes out of hand, and to do that we are continuing the interrogation on each of you so we could move forward.

[Dr. Lannister and Wade just stare at each other angrily and seated again on the chair]

Thomas: Now, if you can excuse me, I have an ongoing interview with Ms. Cathy so please shut your mouths.

[Thomas goes back to the room]

Thomas: Sorry for that Ms. Cathy. Where did we leave again?

Cathy: It’s alright, Mr. Thomas. We left on what am I doing in this hotel and what is my connection to Benjamin.

Thomas: Alright, please continue.

Cathy: Okay. Just like what I have said before, I am Mr. Benjamin’s secretary and I came with him here in the hotel to do my duties as his secretary.

Thomas: Good. Did Mr. Benjamin did something unspeakable to you or did he offend you in some ways? And I want to know where are you last night while the murder is taking place.

Cathy: No, he did not do anything to offend me. (shifts uncomfortably and starts to clung on her skirt) I was laying on my bed in my room and I didn't hear anything suspicious. The only thing that I heard is the bell ringing, saying that it's already 3am.

[Thomas noticed the change in her attitude but he doesn't want to press further because he already guessed what happened between them]

Thomas: It is fine now Ms. Cathy, you can leave now.

Cathy: Can I ask you a question Mr. Thomas?

Thomas: Yes, it is fine with me.

Cathy: How about you Mr. Thomas care to share your own statement before the accident occurred?

[Thomas is mildly shocked with the question because he didn’t expect someone will ask him this question in his entire life]

Thomas: Well, I was in my room the entire time and the room doesn't have extra doors nor a window for doing shady things like being involved in this mess, I was just here to relax to celebrate my retirement and suddenly I was brought up here because of this accident. Also, I can testify that I haven’t known Mr. Benjamin throughout my life.

[Cathy seems satisfied with his answer and left the room]

[Thomas looked at the door and slouched on the couch while drinking coffee. He doesn’t expect that he will be mixed up with a terrible event that will affect his long-awaited retirement]

Scene 4 :

[Thomas got out of the room and asked for Dr. Lannister but Wade interrupted him]

Wade: Well what about that Gwaine? Doesn't he sound suspicious at all?

[Gwaine is shocked that his name got tangled in the mess and tried to stand up for himself]

Gwaine: My good sir, I can assure you that I have not been involved in this gruesome murder. I am only 17 years old and a body like mine can not have the strength to chop off someone, especially with Mr. Benjamin’s size.

[The others agreed with him and looked ridiculously at Wade]

Wade: What? There are serial killers who are younger than him. Everything was possible. (slightly embarrassed with his ridiculous idea)

Cathy; Alright Gwaine’s out but don't butt in too much Gwaine this is for the adults to handle.

Gwaine: I can’t promise you that madam because I'm still going to do my best to help solve this case.

Thomas: So the one left here is only you, Dr. Lannister. Please go to my room so that we can start the interrogation.

Scene 5 :

[The two entered the room]

THOMAS : So, Dr. Lannister, why are you here in the hotel and what is your connection with the victim?

DR.LANNISTER: I am Benjamin’s personal doctor and I came along with him in this hotel to assure that he will take his medicines just like what I have said.

THOMAS: All right Dr. Lannister. So my next question is what did you do last night?

DR. LANNISTER : I am in Benjamin's room because I forgot to tell him about the opium that should be taken after he eats. I think it is already 1 in the morning. Then I left and went to my room to sleep. But I can’t sleep so I just go to my balcony to smoke. Then I went back to my bedroom and fell asleep. I just woke up when I heard Cathy’s screams and hurried to look at the scene. (he fixed the button in his shirt)

[Thomas saw a glimpse of a large scar on Dr. Lannister’s chest]

THOMAS: Dr. Lannister please take off your shirt.

DR. LANNISTER: Excuse me?

THOMAS: I just saw a large scar in your chest and I want to check it.

[Dr. Lannister is shocked at what he hears and immediately looks down in his chest. He tried to hide it again but Thomas’ stern gaze made him nervous and uncomfortable so he took off his shirt.

THOMAS: Where did you get this scar? It looks like a recent wound.

DR.LANNISTER: (winced lightly) The truth is Mr. Benjamin is not the good guy that everyone talks about and admires. I got this wound yesterday from a whip that Mr. Benjamin used to hit me. He did it because I forgot to give him the medicines he wanted. But most times, he only uses it to make fun of me and punish me even though I haven’t done anything wrong. That asshole deserves what happened to him. I bet everyone is secretly relieved that he is finally dead. (angrily shouting)

[Thomas looked at the man pitifully because of his sorry state. His thin body full of scars by getting whipped without a reason angered him. But he reminds himself but murder is not the answer for things like this]

THOMAS: I am very sorry to hear what happened to you Dr. Lannister. But we should remember that murder is still bad, whatever the reasons are. You can now leave.

[Dr. Lannister left the room]

Scene 6 :

[Thomas goes to the lobby]

Mr. Thomas: I think that’s enough for now. Everybody should stay in their own rooms for now, before anything bad happens again.

[Mr. Thomas walking to his room]

[Gwaine following him]

Gwaine: Mr. Thomas! [Mr. Thomas turns around]. Please let me know if I could be of help. I really want to take part in solving this case.

In Mr. Thomas’ mind: This kid’s ability is not a joke, though he’s been annoying and nosy, I think he could really help solve this mystery.

Mr. Thomas: Sure, Gwaine. This case is not an easy one; you and your great mind can be a really great help. Let’s go back to Mr. White’s room to gather more evidence.

[Thomas and Gwaine looked at Mr. Benjamin’s room. The body is now covered with blanket but the smell of the rotting body doubled. The two can’t take the smell and put handkerchiefs in their noses.]

In Mr. Thomas’ mind: The whip marks of Dr. Lannister are similar to the ones in Mr. White’s body. But that is not possible at all because that means that the person who whipped Benjamin and Dr. Lannister are the same. But Dr. Lannister said that Benjamin is the one who whipped him. Something is not right. Dr. Lannister was on the balcony, smoking. Considering the time duration and the weather, staying out on the balcony for a long time will not be possible since it's very cold outside, especially last night because of the snow storm. This case is getting weirder. It feels like many people are involved in this case.

[Thomas shoved his hand in his pocket and lighted his cigarette while thinking]

Scene 7 :

GAWAINE: Uh wait! (put his pointing finger to the temple of his forehead while remembering something)

THOMAS: What? (raised his left eyebrow)

GWAINE: Cathy told me that not all rooms have a bell, and even if there is a bell, it’s too far away to be heard by anybody unless you’re staying near the bell.

THOMAS: What is the sense of having a bell? (a moment of pause) Wait— (a face of enlightenment can be seen in Thomas’ face)

GWAINE: Mr. Thomas, the rooms are all soundproof in this hotel because war and rebellion is often happening in the era when they built this. So we can conclude that Cathy’s alibi is a lie and she is in Mr. Benjamin’s room because you can see and hear the church bell in his window.

THOMAS: That is absolutely brilliant Gwaine! (claps loudly) I am glad that you are here to help. (tapping Gwaine’s shoulders happily) Dr. Lannister and Cathy’s alibis have holes in it so we can assume that they are part of this murder. Alright, let’s go, we'll search the weapon the killer used to chop up Ben’s body.

GWAINE: I think the killer uses an ax knife to chop the body because the way Mr. Benjamin is chopped is similar to the way animals are chopped.

THOMAS: Oh? And how did you know that? (looks at Gwaine suspiciously)

GWAINE: I grew up on a farm, Mr. Thomas. My whole life I have been surrounded by animals and butchers. So I know the pattern between knives and everything they cut into.

THOMAS: Hmm is that so? Okay I understand but I don’t think the ax knife is used here. Where do you think the killer obtained it, if that is what they used?

GWAINE: Maybe that weapon was buried under the heaps of snow?

THOMAS: (deeply thinking) Crap! I remember something.

[Thomas is rapidly heading to the basement and Gwaine runs next to him]

THOMAS: Aha! I am not wrong, it's here.

GWAINE: (looking around and figuring out what Thomas is talking about) What are you talking about?

THOMAS: [Pointed the ax knife below the table]

GWAINE: H-how did this happen? (visibly shocked that he started to shake)

THOMAS: Happened, what? (doubting to Gwaine’s reaction)

GWAINE: I mean, how did you know that there’s an ax here?

THOMAS: Of course, I made a tour by myself the day that I arrived here and saw two axes when I went here in the basement.

GWAINE: Oh, I see. (walks towards the drawer and opens the first layer) so glad that there are gloves here.

THOMAS: Give me one pair, I’ll bring the ax with me. (Gwaine gave him a pair of glove)

GWAINE: So, in conclusion, the killer used an ax knife since you said that there were two axes here, but obviously we just found one ax right now.

THOMAS: Very well said. (Thomas put on his gloves and began to leave the basement together with the ax)

GWAINE: What will you do with the ax?

THOMAS: I will use it as bait to our killers. The game is afoot Mr. Tyrell.

Scene 8

Thomas: Everyone I got news to tell, let's gather at the lobby, because I've figured out who's the one responsible for all of this. (Serious)

[Indistinct chatter]

Hotel staff: Come on!! Tell us who's the one responsible for all of this!!

[All the people at the lobby agreed to one of the hotel staff]

Thomas: We've identified the object that the killer used to kill Mr. Benjamin (Everyone was shocked and Gwaine stepped in with an axe inside a plastic) we've recovered this evidence from the heaps of the snow.

[Indistinct chatter]

Thomas: Dr. Lannister and Cathy!! I've examined both of your testament regarding where were you when this act of crime happened.

Dr. Lannister: What was it Mr. Thomas? (he starts fidgeting and cracking his knuckles)

Cathy: Is everything alright Mr. Thomas? (nervous and tiny tone)

Thomas: Once again I would like the both of you to clarify your statements regarding your whereabouts when the gruesome act of murder took place.

[The both tremble in fear]

Dr. Lannister: Is there anything wrong with my statement Mr. Thomas (his pacing starts getting fast)

Cathay: There must be something wrong right? I mean how could you suspect us even after knowing our statements (starts biting her nails)

Thomas: Calm down the both of you. I am not even saying anything yet, but with that kind of reaction it seems that somehow you both are related to this, and we are about to unfold whether your claims are of truth or not.

[Cathy suddenly collapses on the ground and Dr. Lannister immediately catch her]

Dr. Lannister: Honey! (goes to her immediately and starts to tap her cheeks lightly. Cathy starts to cry loudly)

Cathy: Ah-I didn't want t-to do this (starts gripping her hair) That man told us that everything will go perfect (gripping her hair strongly and starts to flail around) Ah-I was just ordered by man to chop Benjamin's body. He said that he deserves to be chopped because of what he did to me, to us. I didn’t do anything wrong (starts laughing like a maniac)

[Dr. Lannister just looked at the woman that he loved the most with soulless eyes. He wants to cry because of the miserable things they have gone through.]

Dr.Lannister : I do not regret chopping his body. I even tried to feed his body to the wolves but the snow prevented my plan. That man didn’t deserve to live. He will die and burn in hell to eternity.

[Dr. Lannister suddenly laughed like a crazy madman. At the same time, the policeman and the ambulance that Mr. Thomas called just arrived]

[Police and ambulance siren]

[Dr. Lannister and Cathy was taken by the police while others just looked at them with shock and pity]

Scene 9 :

THOMAS : I want to thank you Gwaine for your outstanding performance. Without you, this case will drag for so long. Your wit is a very big help to me. (he extended his hands to shake it with Gwaine)

GWAINE : Oh it was nothing Mr. Thomas. I am just glad that I could use my mind to help you. (shakes Thomas’ hand)

[Thomas saw Gwaine's right hand had what seemed to be a recent whip wound.]

THOMAS : What happened to your hand? Where did you get it? That looks like a (pause; a concerning look) whip mark (in a small voice)

[Gwaine is surprised and while answering, he immediately covered it]

GWAINE : Before heading to the hotel, I was wounded. It is not a whip mark (laughing) I don't even know how to handle it.

THOMAS : Oh okay! I understand (Thomas left)

[Thomas suddenly starts doubting the 17-year-old teenager. He goes back to the crime scene and he was shocked that the limited-edition Sherlock Holmes book that Gwaine wants to borrow doesn’t exist]

THOMAS : I remembered Cathy saying that some man ordered them to chop Benjamin’s body. I thought that she was just using this as an excuse but after examining what happened here. I can assume that Gwaine, a young man who possessed a brilliant mind, can be the only person who directed this brutal murder case. But what is his reason? Why did he kill Benjamin? I cannot believe that some teenager just fooled me. Guessing the whip marks on his hand are the result from the whip, I can deduce that he is the one who whipped Benjamin but because of his inexperience, he is also wounded.

[The door opened and closed quietly. Gwaine is now looking at Mr. Thomas with dark cold eyes that looks like a predator who is ready to kill his victim]

GWAINE : That is an amazing deduction Mr. Thomas (slowly claps) I cannot believe that someone like you is in the police force. All people there are either stupid or doesn’t have any guts to do their job properly.

[Thomas is surprised by the sudden voice of Gwaine echoing in the room. He looked immediately at him and got goosebumps on how cold he looked. It is really different from the young man who smiles brightly at him from the day he arrived at this hotel]

THOMAS : I need an explanation from you about why you do all of this. I trusted you.

[Gwaine laughed in a very scary but broken way and started to tell his backstory.]

Scene 10 :

Gwaine : (laughs maniacally) Well Mr. Thomas, I guess you should not trust strangers so easily, especially from an innocent looking young boy. You know, the thing about betrayal is that it never comes from your enemies. Anyways, you asked why did I constructed a plan to execute a murder of Benjamin White?

It’s just simple. He deserved to die after what he did to my precious older sister. That man ruined my entire life by killing the only person in this world who cares about me. After learning that asshole raped and shoot my sister, I was enraged. I was blinded by anger and guilt because I am not there to protect her. My parents committed suicide after learning that their favorite daughter and heir is killed, not caring about their other son who will be left and live as an orphan for the rest of his life.

[Gwaine inhales sharply and sits on the bed cross-legged. He look so pained after remembering the events that he badly wanted to bury in his mind]

I proceeded to spy and learn everything about him, including his victims. After a lot of research, I decided to convince Cathy Zegarra, the woman who is forced to be his secretary because her family is taken hostage by his people and Dr. Corlys Lannister, the abused doctor of Benjamin and the secret husband of Cathy, to help him kill the man.

[Gwaine dramatically sighs but a single tear glistened in his cheeks]

So what did you think Mr. Thomas? Is it tragic? Do you think I deserved what happened to me? Do you still think that Benjamin should be alive after what happened? Are you one of those people who says that justice is fair and everything must be punished? WHERE WERE ALL OF YOU WHEN MY SISTER IS SUFFERING UNDER THE CLAWS OF THAT MONSTER? WHERE WERE YOU WHEN ALL OF BENJAMIN'S VICTIMS ARE SUFFERING IN SILENCE BECAUSE THEY CAN'T DO ANYTHING ABOUT IT BECAUSE THE AUTHORITIES WILL JUST SIDE THE MAN WHO IS ABLE TO GIVE THEM LARGE AMOUNT OF BRIBE TO KEEP THEIR MOUTH SHUT?

Justice is not always served especially to the people who didn't have the ability to pay handsome bribes for the authorities that should be the one protecting them.

Thomas : (struggling to speak) Uhm…I must say, I am speechless and I am giving my heartfelt condolences for what your family and the other victims of Benjamin experienced but still, why didn't you tell me sooner? If you told me, maybe I can get some of my close contacts to investigate and arrest him.

Gwaine : (laughs dryly) Are you really that naive Mr. Thomas? You've worked as a police officer for 20 years and you still didn't know how the police system works? I am sure that they will just brush you off or maybe they will just try to silence you, either by bribing or killing you. No one can go against this monster, and only by killing him will end this plague.

[Thomas can't think of anything to say and just stayed quiet because deep inside he knew that Gwaine was right. No one can go against a rich and famous business man even do he did many evil deeds that no one can count)]

Gwaine: If you haven't anything to say, I will just leave here immediately. My revenge is done and I hope that monster's soul will slowly burn in hell.

Thomas : Wait Gwaine, do not leave! You still have to face the consequences of your actions! Everything will be alright, just come with me.

Gwaine : No! I know you really are a kind man and have respectable values but that isn't enough for me. I don't see the need to face the consequences of what I have done when what I just did is to get rid of an evil being in this world. I am glad to have met and worked with you Mr. Thomas. Till the next day we meet again!

[Gwaine jumped from the window, hoping to escape but instead of a soft snow, he landed on steel fences where his entire body got impaled. Thomas looked at the boy’s body pitifully and he suddenly noticed a small smile on the boy’s face.]

Thomas : So that’s what he is aiming for huh? He confessed what he did and jumped to his death. He doesn’t want to face the consequences for something he believes is right. I guess that he really just wanted to avenge her precious older sister.

[Thomas just looked at the black sky and lighted his cigarette, realizing how his most awaited vacation turned into a nightmare that he will never forget]

THE END.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angel Mates

Angel Mates

by Taxi_Cab_To_Slowtown

Dean doesn’t say yes right away when Castiel proposes. He thinks that the angel will be throwing away the possibility to find another angel to be with. He goes to Sam who shakes some sense into the hunter. After Dean says “yes,” the preparations for a wedding begin.

But what exactly happens when you have a wedding between the prince of hell, second highest Archangel in heaven, and a human hunter?

Sequel to “Castiel” although this should be mostly understandable even if you haven’t read it.

Words: 3888, Chapters: 1/5, Language: English

Series: Part 2 of Ineffable Family

Fandoms: Supernatural (TV 2005), Good Omens - Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett, Good Omens (TV)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: F/M, M/M, Other

Characters: Castiel (Supernatural), Dean Winchester, Sam Winchester, Bobby Singer, Crowley (Good Omens), Aziraphale (Good Omens), Gabriel (Supernatural), Samandriel (Supernatural), Rowena MacLeod, Adam Young (Good Omens), Balthazar (Supernatural), Rufus Turner, Jo Harvelle, Ellen Harvelle, Garth Fitzgerald IV, Benny Lafitte, Beelzebub (Good Omens), Gabriel (Good Omens), Pepper (Good Omens), Original Children of Pepper/Adam Young, Crowley (Supernatural), Dagon (Good Omens), Eric | Disposable Demon (Good Omens), Asmodeus (Supernatural), Meg Masters, Sandalphon (Good Omens), Ishim (Supernatural), Anna Milton, Metatron (Supernatural), Benjamin (Supernatural: Lily Sunder Has Some Regrets), Hannah (Supernatural), Tessa (Supernatural), Belphegor (Supernatural), Jody Mills, Anathema Device, Newton Pulsifer, Original Child(ren) of Anathema Device and Newton Pulsifer, Queen Djinn (Episode: s13e16 Scoobynatural)

Relationships: Castiel/Dean Winchester, Aziraphale/Crowley (Good Omens), Rowena MacLeod/Sam Winchester, Beelzebub/Gabriel (Good Omens), Pepper/Adam Young (Good Omens), Crowley (Supernatural)/Bobby Singer, Anathema Device/Newton Pulsifer

Additional Tags: Wedding Proposal, Angel Mating, Dean/Castiel wedding, Gabriel king of Heaven, Crowley (Good Omens) king of Hell, Married Crowley/Aziraphale, Rowena works for heaven, Samandriel is Gabriel’s secretary, Dean Winchester is scared of commitment, Fluff, Adam young is Crowley/Aziraphale’s godson, Knight of Hell Dean Winchester (but only in name), Aziraphale and Crowley (Good Omens) are the Parents of Castiel (Supernatural)

From https://ift.tt/jnAf6ku

https://archiveofourown.org/works/41704560

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gaza and the End of Western Hypocrisy

There is something surprising in the way Western democracies have reacted to events in Israel since the start of the military operation in Gaza. I call it the end of hypocrisy. Take President Joe Biden. On two occasions he has publicly said that Israel is conducting “indiscriminate bombings” in Gaza, a war crime under international law. Lawyers have even argued his statements amount to a confession of aiding and abetting war crimes, no small matter.

Why would Biden do this? Why not simply proclaim a number of high principles and then proceed to ignore them in practice? The late Henry Kissinger seemed to know better and to be concerned with the role of hypocrisy in world affairs, a balancing act between the need for norms and the equally important need to occasionally break them.

Biden, by contrast, says the quiet part out loud. His team, from Sullivan to Blinken and the ineffable John Kirby, has followed his example. They have consistently refused to even mention international law or universal principles, preferring to point out that Israel is a “close partner.” To a partner, much or all is allowed, including the deliberate destruction of hospitals and schools. When Russia did it in Ukraine, Blinken and Kirby called it barbaric. “Hitting playgrounds, schools, hospitals,” said Kirby, “is utter depravity.” He was talking about Russia, not Israel.

When asked what the Biden Administration would do if Israel continued to commit war crimes, his answer was disarmingly sincere: “We will continue to support it.” At the same fundraiser where he claimed Israel was conducting indiscriminate bombings in Gaza, Biden added for good measure: “We are not going to do a damn thing other than protect Israel. Not a single thing.”

No one could accuse the U.S. of double standards. What it is vulnerable to is the accusation that it no longer has any standards at all.

But standards have their uses and not only for the sentimental. They give form to world politics and drive other states to follow rules decided and enforced by a higher power. With the right level of hypocrisy, they allow you to subject others to your rules while remaining somewhat above them. The challenge is to explain why the U.S. would be so willing to renounce the advantages of hypocrisy and its role as rule-maker. In the way it has addressed the political and humanitarian crisis in the Middle East, we see what it would mean for the existing world order to unravel, as American power gives up on the mission of every hegemon: to shape world politics according to its own plan and, as always happens, its own standards.

The reason for America’s capitulation is that rules are always a hindrance to free action. Even for those in charge of creating and enforcing them, or especially for them, since ordering the world is hard work and gets in the way of enjoying it. No great power has ever been founded on the subjectivity of desire or impulse, but those temptations are just as present in the life of nations as in the life of individuals.

Once upon a time, Washington still aspired to bring some kind of order to the Middle East. The task required discipline. It required at least the pretence of impartiality between all the different sides. At no point was this discipline better seen than in 1991 in Madrid, with the last genuine effort by Washington to bring the Israelis and the Palestinians together. Secretary of State James Baker understood the Middle East, which must entail having empathy for the different worldviews to be found in the region. “Those of us who met Baker,” Rashid Khalidi has written, “sensed that he had sympathy for the predicament of Palestinians under occupation and understood our frustration at the absurd restraints imposed by the Shamir government.”

In 1992 James Baker decided to condition $10 billion in aid to Israel on its halting settlement construction. Bill Clinton, running in the Democratic primaries, accused him of making antisemitism “acceptable,” a herald of things to come.

Ten years earlier, Baker was the White House Chief of Staff when President Reagan called Prime Minister Menachem Begin to force him to stop the leveling of Beirut during the 1982 Lebanon War. As recorded in his diaries, Reagan told him he had to stop it at once or “our entire future relationship was endangered. I used the word holocaust deliberately and said the symbol of this was becoming the picture of a 7 month old baby with its arms blown off.” Twenty minutes later Begin called back to say he had ordered an end to the barrage.

James Baker was, of course, able to do only so much, but today the role he attempted to play has been entirely jettisoned and if America cares about anything, it is less to create an idea of order than to pursue its private visions and to build a virtual playground where they can be pursued and fulfilled. What gets in the way of surplus enjoyment is less a problem to be addressed than an obstacle to be eliminated. Can anyone take seriously the traditional American aspiration to play the role of a mediator when President Joe Biden sat with Israel’s war cabinet while it decided on the best way to attack Gaza, an attack whose consequences are now all too clear?

In these private fantasies, the Palestinians are little more than disposable props, often forced to play certain roles that bear little resemblance to their real existence. As Barnett Rubin points out, the narrative now hegemonic in the West is a simple, linear one: the establishment of the state of Israel from the ashes of the Holocaust and the struggle of the Arab and Muslim worlds against it are extensions of the victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany. And it helps, as Edward Said liked to note, that Palestine is also a privileged site of origin and return for Western civilisation: from the Crusades to Dante, Shakespeare and Lawrence. Both Netanyahu and Israeli President Isaac Herzog have argued that the war in Gaza is a war for Western civilisation. It would be worth asking why so many wars for Western civilisation must happen in the Middle East. What strange psychological projection is hidden here?

Never mind that the history of the Arab world shares nothing with these narratives or that Jews lived peacefully with Muslims in Palestine under the Ottomans, with “no more friction than is commonly found amongst neighbours” (as Mahmoud Yazbak writes in his Haifa in the Late Ottoman Period). Palestinians must be assimilated under our favourite categories. For Germany, its commitment to Israel is offered as a test of whether the country has overcome its Nazi past. This is politics as psychology or, better, put, psychoanalysis. There are no limits of prudence or public reason. Reality is of no consequence, what matters is redemption. As Daniel Marwecki argues in his Germany and Israel, Israel serves “as displacement object onto which different ideas of German national identity can be articulated.” It serves as “a form of reconciliation that seeks to cleanse Germany of antisemitism, which time and again seems to creep back into view.” This catechism, as Dirk Moses calls it, implies a redemptive story in which the sacrifice of Jews in the Holocaust becomes the myth of origin for a new Germany: “Having undergone the most thorough working through of history in history, Germany can once again stand proud among the nations as the beacon of civilization, vouched by approving pats on the head from American, British and Israeli elites.” Modern Germany needs to believe that Israel's creation was a "happy ending" to the horrors of the gas chambers.

Within the dreamscape of German return and redemption, and by extension much of the West, the Israeli dreamscape is like a smaller concentric circle, its fantasies speaking of final control over a sacred land. As Daniella Weiss, one of the leaders of the Israeli settler movement, put it recently, “the settlers need to see the sea. That is a logical and romantic demand.” An Israeli estate agent advertised beachfront villas digitally superimposed upon a destroyed Gaza with a message reading “Wake up, a house on the beach is not a dream.”

The Western narrative, valid and true in its context, becomes a ruinous myth when it replaces other stories and experiences. No single narrative can encompass the whole of human history. Those charged with building order must strive for a full picture.

In the debate over the past few months we have witnessed staggering levels of fabulation. One television presenter said on air that no Palestinian Christians exist. One Israeli official added that there are no Christian churches in Gaza. When the Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer was killed in an Israeli airstrike, an organised effort started online to portray him as a terrorist. Anything else would be a narrative violation.

One of the biggest and most influential newspapers in Germany claimed, incredibly, that “Free Palestine is the new Heil Hitler.”

The systematic destruction of almost every hospital and school in Gaza is presented as necessary to defeat Hamas. The silence around the killing of so many civilians is not imposed but accepted by those for whom every opposing fact would divert from the full enjoyment of fantasies where the West is once again fighting evil, and this time evil has no armed divisions with which to fight back. There have been protests in some Western capitals, to be sure, but this time they have been kept separate from the political and intellectual establishment, and their influence is highly doubtful. Since the children of Gaza fit uneasily with the stories we like to tell ourselves, they have become almost invisible.

In fantasies or dreams, other people have no real existence. They are just projections of the dreaming self, and the goal is to create a world where desires find no outside resistance. There is great danger in this temptation, which in Israel has already found expression in proposals to transfer two million Palestinians from Gaza to the Sinai. The Israeli government now finds it impossible to convince people to go back to their homes in Southern Israel because it has promised total defeat of Hamas. On November 11, Agriculture Minister Avi Dichter told a television channel that the war would be the Gaza Nakba, using the Arabic word applied to describe the 1948 displacement of roughly 700,000 Palestinians. On December 25, Christmas Day, during a Likud faction meeting, Netanyahu told his colleagues he was working on a plan to move Palestinians from Gaza to other countries and called it a “strategic goal.” According to several reports, confirmed by my own sources, the Israeli Prime Minister had already tried to convince a number of European leaders to help him with the plan. In recordings from Netanyahu's meeting with the families of the Israeli hostages that took place on January 3, the prime minister was heard saying that a "scenario of surrender and deportation" in the Gaza Strip is being considered. Also on January 3 Zman Yisrael reported that Israeli officials have held clandestine talks with the African nation of Congo and several others for the potential acceptance of Palestinians from Gaza. There seem to be no rules left, and no desire to create new ones.

We used to have fantasies; now we live them out. The effect is intoxicating. But in Gaza there is a reckoning, or a double reckoning. First, we now realise that a life of fantasy can easily become the source of the deepest horrors. Fantasy dehumanises. As Gilles Deleuze once observed, there is nothing more terrible and more terrifying than to be captured by the dreams of others. And indeed, to be captured in so many concentric dreams has become the Palestinian inescapable nightmare. Second, if those with power spend their time entertaining private fantasies, then the task of building order must in time devolve to someone else.

In Gaza we are witnessing the pathologies of a quickly declining America, its role no longer that of an ordering power but of a demiurge building a world of private enjoyment.

#the US is complicit in genocide#the US is complicit in mass murder#the US is complicit in war crimes#genocide joe#israel is committing genocide#genocide#israel is an apartheid state#apartheid#ethnic cleansing#collective punishment#illegal occupation#this was never about hamas#israeli lies#israeli war crimes#propaganda kills#israel isnt above the law#israel is a terrorist state#israel is not the victim#accountability isnt anti semitism#stop the killing#stand with palestine#stand up for humanity#save palestine#free Palestine 🇵🇸#fuck bill clinton#not in my name#ashamed of the US#military industrial complex#the US has the blood of millions of innocents on its hands#the decline of Western civilization

1 note

·

View note

Text

Out of Kansas: Revisiting “The Wizard of Oz.”

By Salman Rushdie

May 4, 1992

I wrote my first story in Bombay at the age of ten; its title was “Over the Rainbow.” It amounted to a dozen or so pages, dutifully typed up by my father’s secretary on flimsy paper, and eventually it was lost somewhere on my family’s mazy journeyings between India, England, and Pakistan. Shortly before my father’s death, in 1987, he claimed to have found a copy moldering in an old file, but, despite my pleadings, he never produced it, and nobody else ever laid eyes on the thing. I’ve often wondered about this incident. Maybe he didn’t really find the story, in which case he had succumbed to the lure of fantasy, and this was the last of the many fairy tales he told me; or else he did find it, and hugged it to himself as a talisman and a reminder of simpler times, thinking of it as his treasure, not mine—his pot of nostalgic parental gold.

I don’t remember much about the story. It was about a ten-year-old Bombay boy who one day happens upon a rainbow’s beginning, a place as elusive as any pot-of-gold end zone, and as rich in promises. The rainbow is broad, as wide as the sidewalk, and is constructed like a grand staircase. The boy, naturally, begins to climb. I have forgotten almost everything about his adventures, except for an encounter with a talking pianola, whose personality is an improbable hybrid of Judy Garland, Elvis Presley, and the “playback singers” of Hindi movies, many of which made “The Wizard of Oz” look like kitchen-sink realism. My bad memory—what my mother would call a “forgettery”—is probably just as well. I remember what matters. I remember that “The Wizard of Oz”—the film, not the book, which I didn’t read as a child—was my very first literary influence. More than that: I remember that when the possibility of my going to school in England was mentioned it felt as exciting as any voyage beyond the rainbow. It may be hard to believe, but England seemed as wonderful a prospect as Oz.

The Wizard, however, was right there in Bombay. My father, Anis Ahmed Rushdie, was a magical parent of young children, but he was prone to explosions, thunderous rages, bolts of emotional lightning, puffs of dragon smoke, and other menaces of the type also practiced by Oz, the Great and Powerful, the first Wizard De-luxe. And when the curtain fell away and his growing offspring discovered, like Dorothy, the truth about adult humbug, it was easy for me to think, as she did, that my Wizard must be a very bad man indeed. It took me half a lifetime to work out that the Great Oz’s apologia pro vita sua fitted my father equally well—that he, too, was a good man but a very bad Wizard.

I have begun with these personal reminiscences because “The Wizard of Oz” is a film whose driving force is the inadequacy of adults, even of good adults; a film that shows us how the weakness of grownups forces children to take control of their own destinies, and so, ironically, grow up themselves. The journey from Kansas to Oz is a rite of passage from a world in which Dorothy’s parent substitutes, Auntie Em and Uncle Henry, are powerless to help her save her dog, Toto, from the marauding Miss Gulch into a world where the people are her own size and she is never, ever treated as a child but as a heroine. She gains this status by accident, it’s true, having played no part in her house’s decision to squash the Wicked Witch of the East; but, by her adventure’s end, she has certainly grown to fill those shoes—or, rather, those ruby slippers. “Who would have thought a good little girl like you could destroy my beautiful wickedness,” laments the Wicked Witch of the West as she melts—an adult becoming smaller than, and giving way to, a child. As the Wicked Witch of the West “grows down,” so Dorothy is seen to have grown up. This, in my view, is a much more satisfactory reason for her newfound power over the ruby slippers than the sentimental reasons offered by the ineffably loopy Good Witch Glinda, and then by Dorothy herself, in a cloying ending that seems to me fundamentally untrue to the film’s anarchic spirit.

The weakness of Auntie Em and Uncle Henry in the face of Miss Gulch’s desire to annihilate Toto leads Dorothy to think, childishly, of running away from home—of escape. And that’s why, when the tornado hits, she isn’t with the others in the storm shelter and, as a result, is whirled away to an escape beyond her wildest dreams. Later, however, when she is confronted by the weakness of the Wizard of Oz, she doesn’t run away but goes into battle—first against the Wicked Witch and then against the Wizard himself. The Wizard’s ineffectuality is one of the film’s many symmetries, rhyming with the feebleness of Dorothy’s folks; but the different way Dorothy reacts is the point.

The ten-year-old who watched “The Wizard of Oz” at Bombay’s Metro Cinema knew very little about foreign parts, and even less about growing up. He did, however, know a great deal more about the cinema of the fantastic than any Western child of the same age. In the West, the film was an oddball, an attempt to make a sort of live-action version of a Disney cartoon feature despite the industry’s received wisdom that fantasy movies usually flopped. (Indeed, the movie never really made money until it became a television standard, years after its original theatrical release; it should be said in mitigation, though, that coming out two weeks before the start of the Second World War can’t have helped its chances.) In India, however, it fitted into what was then, and remains today, one of the mainstreams of production in the place that Indians, conflating Bombay and Tinseltown, affectionately call Bollywood.

It’s easy to satirize the Hindi movies. In James Ivory’s film “Bombay Talkie,” a novelist (the touching Jennifer Kendal, who died in 1984) visits a studio soundstage and watches an amazing dance number featuring scantily clad nautch girls prancing on the keys of a giant typewriter. The director explains that the keys of the typewriter represent “the Keys of Life,” and we are all dancing out “the story of our Fate upon that great machine.” “It’s very symbolic,” Kendal suggests. The director, simpering, replies, “Thank you.” Typewriters of Life, sex goddesses in wet saris (the Indian equivalent of wet T-shirts), gods descending from the heavens to meddle in human affairs, superheroes, demonic villains, and so on, have always been the staple diet of the Indian filmgoer. Blond Glinda arriving at Munchkinland in her magic bubble might cause Dorothy to comment on the high speed and oddity of the local transport operating in Oz, but to an Indian audience Glinda was arriving exactly as a god should arrive: ex machina, out of her own machine. The Wicked Witch of the West’s orange smoke puffs were equally appropriate to her super-bad status.

It is clear, however, that despite all the similarities, there were important differences between the Bombay cinema and a film like “The Wizard of Oz.” Good fairies and bad witches might superficially resemble the deities and demons of the Hindu pantheon, but in reality one of the most striking aspects of the world view of “The Wizard of Oz” is its joyful and almost total secularism. Religion is mentioned only once in the film: Auntie Em, spluttering with anger at gruesome Miss Gulch, declares that she’s waited years to tell her what she thinks of her, “and now, well, being a Christian woman, I can’t say it.” Apart from this moment in which Christian charity prevents some good old-fashioned plain speaking, the film is breezily godless. There’s not a trace of religion in Oz itself—bad witches are feared and good ones liked, but none are sanctified—and, while the Wizard of Oz is thought to be something very close to all-powerful, nobody thinks to worship him. This absence of higher values greatly increases the film’s charm, and is an important aspect of its success in creating a world in which nothing is deemed more important than the loves, cares, and needs of human beings (and, of course, tin beings, straw beings, lions, and dogs).

The other major difference is harder to define, because it is finally a matter of quality. Most Hindi movies were then and are now what can only be called trashy. The pleasure to be had from such films (and some of them are extremely enjoyable) is something like the fun of eating junk food. The classic Bombay talkie uses a script of appalling corniness, looks by turns tawdry and vulgar, or else both at once, and relies on the mass appeal of its stars and its musical numbers to provide a little zing. “The Wizard of Oz” has stars and musical numbers, but it is also very definitely a Good Film. It takes the fantasy of Bombay and adds high production values and something more—something not often found in any cinema. Call it imaginative truth. Call it (reach for your revolvers now) art.