#is so fundamentally lacking in empathy to me in many ways and why that abstracted 'imma solve my own misoginy' doesnt work. imho

Text

tbh its so interesting how the current brand of internet politics, ie you have to be learned already in social justice, approaches books and characters who are not flawless in that sense. specifically talking abt internalised misoginy here bc its the only topic I feel comfortable applying the thought process to personally.

like, the knee-jerk reaction of criticising 'yes this woman in a period piece shouldn't have internalised misoginy' more than 'the book acknowledges that she has tons and when it fails to address it meaningfullly, maybe even if it tries to, it cannot conceptualise solving the issues by building communal love between women but only by some vague interal change of heart'. especially when i feel like the latter is so much more interesting when it comes to like. how fundamentally warped some brands of 'addressing ones one misoginy' CANNOT work if you do learn to empathise with women, such as the not like other girls wave of cold takes

#.text#five bucks to whomever guesses the book i saw a take from#anyway like. the entire deal with the not like other girls thing and how many ppl made peace with it is so weird to me#like yeah its bad to look down on other women for being into traditionally feminine thing#but the way the response has turned out to be fundamentally lacking in empathy towards other women who COULDNT meaningfullly#roleplay into various stages of femininity by no fault of their own (queer women. neurodivergent women) and had to make do someway#is so fundamentally lacking in empathy to me in many ways and why that abstracted 'imma solve my own misoginy' doesnt work. imho

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m new here and couldn’t tell from the tone of some asks (sorry) but did you like what they did with Ben in TRoKR ? I saw the discussions abt him lacking agency in it and I 100% agree but did you personality agree w/ the passive, “things only happen to me” vibe they gave him? And second question: can u give examples of how soule’s writing was telegrsmed in TFA? Thank u for taking the time xx

Like I’ve said before, it’s exactly the kind of backstory I would have written for him/always imagined. I had expected to find out he didn’t kill the other students/fought them in self defence/it was some kind of accident or emotional overload incident in TLJ. That was where everything was pointing.

Someone this insecure and conflicted about what he’s doing, someone who prays for help to resist his loving nature and cries when he sees his dad, who is so uncomfortable with himself he is covered head to toe not even his voice unmasked, who immediately latches on to the protagonist as a kindred spirit in loneliness and needs her to know he’s not a creature and wants to help her rather than hurt her- that’s not a person who had an eyes-open, all-in fall to the dark side full of decisive action and unhindered agency.

Leia saying ‘it was Snoke’ told us from the get go we’re in a situation where he was haunted and manipulated. His subservience and rote, childish repetition of ‘the Supreme Leader is wise’ when Han tells him Snoke doesn’t care about him. The constant, ongoing contradiction of his behaviour and motives tell us he has no conviction in the cause he’s supposedly supporting. His self-harm and naked suffering in the face of his own actions, his recklessness and inability to commit to selfishness and lack of ambition tell us those aren’t qualities which drove him here. He is highly emotionally driven, there’s no tangible goal and he doesn’t have a vision of the future. So why is he on the dark side?

It’s not that things only happen to him or that he’s passive, it’s that Ben has never pursued or been comfortable with what darkness really is and that has always been obvious. He tries very, very hard and fights tooth and claw to cling to something good in the comic until all of it is in ashes- he’s not passive, but he can’t win. No one can hold out forever against that kind of relentless onslaught. That he was absolutely a victim doesn’t mean he has no agency in his later choices. He’s not absolved of responsibility. But his reluctance and victimhood only makes sense, anything else would be incongruous with TFA.

There was never pursuit of power for power’s sake from him- there’s nothing he wants that the dark side can give him, he is there literally because he felt he had nowhere else to go. I said this before TLJ even came out. He felt he could not escape it, both because of the fatalism his family unintentionally instilled in him and because Snoke convinced him none of them loved him, that he is only useful or valued as a tool. Ben is a person who doesn’t believe he has any inherent value just for himself- just Ben, he believes that he can’t be forgiven for the sin of being born a disappointment, and that everything is his fault because he’s wrong and bad no matter what he does. None of his choices feel to him like real choices, all of his options appear to have been taken from him, and he feels compelled to plunge forward on the only remaining path. The comic provided an emotionally and logically cogent explanation for exactly why he would feel that way which is completely consistent with all the implications about his past and his characterisation from the films.

As I’ve pointed out before, there’s a reason he says ‘it’s too late’ to coming home not ‘I don’t want to’. There’s a reason he says ‘what I have to do’ and ‘he (I) was weak and foolish’- there’s a reason he needs Han’s help to go through with killing his father. It’s not about what he wants (he wants to go home with his dad- he thinks he can’t), he has never felt free to make his own choices or that freedom is possible for him.

Even at his darkest he never became cruel, he never enjoyed killing or hurting people, and he totally fails to suppress his instinct to be compassionate. He has a highly developed conscience and an overflowing core of empathy he can’t seal off. That’s why he’s so miserable as he pushes himself to do things he finds abhorrent- but he thinks he has to, there’s no escape, it’s the only way. In the sequence which establishes this character, even before any layers are stripped away or the investment we naturally have in him because of who he is is revealed, one of the first things we see him do is have compassion for F/nn. Those two characters are connected and a comparison is invited- this is visual storytelling showing you that they have something in common (it will be made clear later on that Ben saw himself in F/nn and that’s why he takes his actions so personally- cognitive dissonance).

F/nn was a good person trapped in the mask of the stormtrooper by circumstances beyond his control, but he is able to reject it and reclaim his identity. Ben is a good person hounded into the mask of Kylo Ren by his family’s failure to reconcile with Vader. The crushing weight of their expectations and their total lack of faith in him combined with their lies and Snoke’s manipulation convinces him there is ‘too much Vader in him’ and that Ben Solo isn’t and never will be good enough for anyone. That his love, compassion, and selflessness are all weaknesses which will only cause both him and the galaxy further suffering.

He is the most morally sensitive person in the new gen, he is the most outward-orientated and loving. His impulse is to be selfless and helpful, but that impulse has been relentlessly punished until he mistrusts it and thinks he must repress his wrong instincts and serve a ‘greater order’ guided by someone stronger than him. He has an acute sense of the impact of his actions and he considers it (even when he loses control of his emotions, he overwhelmingly targets things rather than people and his angry threats are empty).

In contrast, Anakin (who was committed on the dark side and successfully cut himself off from his empathy for many years) was all in on the pursuit of power even when he still had good intentions. Anakin also knew that power was the foundation of the dark side and he and Palpatine would always be at odds, that some day he would overthrow him and take his place. Ben only values power out of fear, and solely primal fear not more abstract, possessive fear like Anakin’s, he wants safety. He doesn’t go to Snoke thinking he’s ever going to take his place or gain his power- he wants Snoke to give him belonging and acceptance. He’s then convinced that the ends justify the means and doing things he knows are wrong and which cause him pain are necessary because his whole life and Snoke’s machinations have set him up to believe that. He is still trying to create safety and doing what he’s convinced must be done and will be done one way or another.

Ben is a beautiful compassionate person and always has been and that is why he’s in such constant, excruciating pain trying to shut himself off from love and vulnerability. He is following Snoke’s demands and trying to kill his past to stop the pain, to kill this vulnerability and need and weakness in himself. Connection was always what he wanted most and he is trying to cut off and cauterise all of the broken, abandoned bonds of love his family has left him with. And even here, he still wants Snoke’s acceptance, Snoke’s validation and esteem. He is still pouring himself out for an other, giving everything to please someone else, the last person left who tells him it’s possible he can achieve value.

He latched on to Rey instantly when he realised they were alike and did everything possible to lift her up and spare her what he went through. He only rejected Han and Rey’s offers to come with them because he thinks their love is conditional and that small, dirty, broken Ben Solo will never be able to meet the conditions. He thinks he is a tool or an obligation to them and it’s easy to understand why he thinks that. Han couldn’t wipe away a lifetime of baggage in a few words. Rey pretends it’s about the cause, she doesn’t tell him she loves him.

He thinks he must ‘become who he was meant to be’ and that his destiny is to become a new Vader. Everyone told him that. Whether with their fear or directly with words. When he finds out the truth about his grandfather, it’s a complete confirmation of what Snoke has told him and how his parents have treated him. Luke deciding he can’t be allowed to live because it’s that inevitable is the nail in the coffin in Ben believing there’s any place for him with his family. There is nowhere for him to exist as himself, he has to be someone else, someone less weak. And in running away from himself, his legacy, and his identity he puts himself under Snoke’s thumb and Snoke can finish inculcating his worldview.

Being able to love is freedom to Ben. He is an immensely loving person who feels like he is not worthy or allowed to love people, that his love has done nothing but make things worse for everyone. The tension and repression of trying not to need or care about people is what makes him so emotionally unstable. Kylo Ren is a mask and a shield and a prison built by Ben’s hurt and anxiety but equally built by Snoke out of his boyhood fancies to control him and shape him into an instrument of pain. Ben could never have conviction in it because it is so alien to his nature. He is so fundamentally unselfish that he never coveted like Anakin eventually did, his love never became possessive or jealous, he never sold his soul for a boon, the only way he could be selfish enough to murder is out of animal fear and pain. Wanting the hurting to stop. Rationalising it post-facto with the philosophy that the ends justify the means.

He pours himself out for Snoke because there is no one else left. All he wants is the safety and acceptance that he has literally never had anywhere. Anakin received unconditional love from his mother, Obi-wan, and Padmé and was warped from giving compassion into selfishness by his fear of loss and need for control. Covetousness became his tragic flaw and thus his fall culminates in trying to kill Padmé rather than lose her. Control became so important that others ceased to matter and love became possession. Anakin (despite also being a victim of manipulation and Jedi hubris) got to make real choices, he had real options, and thus he was a villain with conviction. Ben’s attempts to take control of his life are unfocussed and mostly involve abnegation, he pushes people away instead of trying to clutch them close; his response to loss is to isolate himself not seize power to recover the lost thing by force. Ben never received unconditional love until Han’s sacrifice on the bridge and the experience immediately shatters him from his already tenuous position in the dark. The only thing keeping him from coming home after that is sunk cost and the idea that he can never be forgiven. That it was too late.

He just needed someone to show him it wasn’t.

#ben solo#this is repetitive brain vomit my apologies#I can't words any more everything is too terrible#he is a good boy though okay#the fact that he's a broken person rather than someone more inclined to dark paths doesn't lessen his redemption#he still did Very Bad Things and being convinced it was necessary or inevitable doesn't make it okay when a part of you knows it's not true#healing is the thing everyone has trouble beleiving in#and it's just as difficult to heal from misguidedness you were traumatised into as willful shittiness#maybe more so#because it feels less like a bad decision and more like you're just fucked up and can't help being fucked up#he'd still be just as redeemable if he were far more evil#but he is baby and I LOVE that about him#because there's nothing I love more than characters who are not what they appear to be#anyway reason 487389750783 he needed to live#it's not that he 'deserves' it more it's that you have to show you can recover#that you're not worthless if you can't be the perfect victim and pull yourself up by your bootstraps

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

IT IS DOUBLE PLEASURE TO DECEIVE THE DECEIVER

Today I want to talk about what happens when the antisocial personality disordered service with complex care needs and behavioural issues -- ah fuck it -- the sociopath, finds out they have been lied to.

What’s your normal reaction when someone you trust and/or love comes at you with a lie? It may take you a while to figure it out, or maybe they’re a bad liar or have lied to you before and you can watch the lie play out as it comes out of their mouth, and a normal reaction would be anger, sadness, despair, all of those things. So what would you do in the wake of that lie? If you were healthy and strong, you might confront it in a controlled way. No matter how strong you are, you may behave irrationally, you may become suspicious or go into paranoia overdrive, perhaps you’ll find yourself becoming increasingly sarcastic or mean, you might just burst into tears, and all of those are normal reactions when you find you’ve been lied to. But today I want to talk about what I think might be the antisocial reaction to lies.

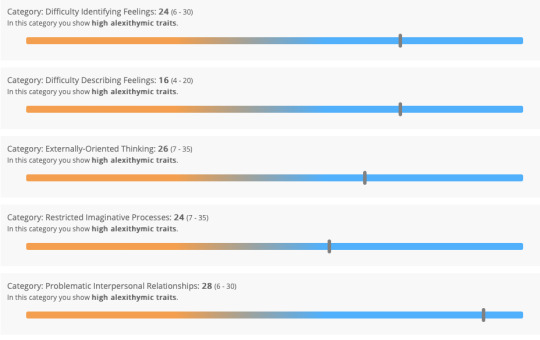

When I’m lied to, there will always be a part of me that feels wounded and in pain, if the person lying to me is someone i’ve let into my life and my mind. Yes, it’s true, we feel pain. I probably won’t know the name of the pain I’m feeling, and when this lack of emotional connection to myself happens, I react with -- yep, you guessed it -- rage. That’s my default setting. I’ve been told in the past, “what you’re experiencing is despair”, “it’s probably because you feel so insignificant”, “it makes sense that right now you would be going through a sense of unease”, or whatever, and when it’s pointed out to me, I can sometimes grab onto that description and root around in my psyche to see if that was a correct assessment, and if it is, I can latch onto it somewhat. But anger is what happens to antisocials who experience alexithymia (an inability to identify or explain one’s own emotions). Like this:

I often need someone to tell me what they think I’m feeling, and then, if it starts to make sense, I’ll assume that’s what’s what. I’m not the kind of sociopath who will brag about how little I like to hear about other people’s emotions, because really, I love hearing about people’s emotional worlds. Yes, perhaps I despise the assumption that it’s my job to feel on behalf of someone else, that being a good person isn’t so much tied in helping someone with a problem as it is feeling that problem, but listening to how people process their emotions is useful to me, and also kind of fascinating. If you’ve heard that sociopaths have no feelings, what’s perhaps more accurate is we don’t know we have feelings.

So, we lash out. Anger is the most deregulated emotion in antisocial personality disorder, and I believe that’s because it’s our real emotions that are deregulated, but rage and hostility is the other mask we wear, the most pervading one, the one that we have even convinced ourselves with.

So, when experiencing a lie, we’ll get angry.

But it doesn’t end there.

Antisocial personality disorder comes with many choices. I once likened it to living in a constant click-and-point video game, and I stand by that. In moments of violent conflict or threat you might see a glass bottle on the ground and quick as lightening your brain will light the thing up and you’ll run through the options: do I want to pick up this bottle? Do I want to use it as a weapon? Do I want to hide it and come back to it? Do I want to leave it and scan the room to see what else is here? And, in times of interpersonal conflict, something rather more abstract, you may experience anger, and the angry part of your brain will light up (🎵hello amygdala my old friend🎵 ) and your rationale (if we can ever really have that) will say: what do I want to do with this anger? Do I want to direct it to the threat? Do I want to harm them with it? Do I want to pretend it isn’t there? Do I want to hide it and come back to it? Do I want to leave it and scan my brain to see what else is here? But then there comes the big one -- do I want to accept the truth of this anger? Do I want to display it?

Do I want to play the game?

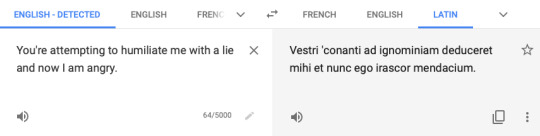

When you are used to anger being your default setting, you learn lots of different ways to express it, and whilst the explosive kind of “FUCK YOU AND FUCK EVERYTHING YOU STAND FOR” is what we’d most likely think of when thinking of what rage looks like, there’s many ways it can come through, and the example I gave here of reacting to a lie I think is a good place to start when talking about this. Because anger isn’t always fireworks. A lot of the time, it’s silence. Amusement. Catharsis. Comedy. It’s like we have to take the “generic bad” feeling, reroute it to anger, and let it come back out as something else. It’s like, when it comes to our feelings, we have taken a sentence, run it through Google translate into a foreign language, taken that foreign language and put it back through Google translate again, and try to make something of the broken English we’ve come back with.

You’re trying to humiliate me and now I am angry lie. My angry lie is that I think you’re a bad person. I think you’re selfish. I have never liked you. This is hilarious to me. I deserve better than this...

I deserve better than this is the biggest lie we tell when we’re lied to, because deep down, we don’t think we deserve better than this at all. If antisocial personality disorder has its roots in deeply embedded cynicism, pessimism, isolation and trauma, then every single mask we wear is one of ultimate power, control, self-assuredness and confidence. I deserve better than this can never be true, because that would require empathy, and our lack of empathy is most evident when it comes to talking about ourselves. If we don’t know the names of our feelings, we cannot empathise with them.

So what’s the next step? You know the old saying, “fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice, shame on me”? When you have a lowered ability to experience remorse and guilt, no propensity to feelings of regret, shame doesn’t come into it. I’m not ashamed I let myself be lied to. I’m... what’s the word? What’s the name of this? Oh right, that’s it. I’m angry. But I did the shouting, kicking off, the big display of ego when I was fooled the first time. The second time, the lie lights up in my head: do I want to pick up this lie? Do I want to confront this lie? Do I want to pretend it isn’t there? Do I want to leave it there for a second whilst I scan whatever else is going on, for example: does the liar seem to also be sad, confused, misunderstood, are they nervous? Playing with their hair, looking off in different directions, are they shaking or babbling or misdirecting? And what do I want to do with that? Do I want to tell them my suspicions? And just what is this? Why are these things lighting up? Is it a game? Is this a game?! Can I win it?!

And this is why Machiavelli once famously said, “it is double pleasure to deceive the deceiver”, and this is why Machiavellianism forms part of the Dark Triad of psychopathy. Because it’s abnormal to see a lie as a game, it’s clinically weird, psychologically speaking, it’s crazy cuckoo. Why would anyone watch someone lie and feel a sense of relief washing over them (in an awesome wave)? Why would anyone in their right mind see a lie happen, and then wonder for how long the rally of lies can go back and forth, to see who will break first, to take the liar and lie to them so hard they’ll regret ever lying to you? As I outlined at the beginning of this blog, there are normal reactions to lies and even the explosive and distressed ones are normal. What’s abnormal is the willingness and even eagerness to throw oneself into the pit and get right into it. Because people with antisocial personality disorder are always seeking out conflict. Even when we’re evolved, doing better these days, in therapy, writing a blog -- we don’t like the things you don’t like, and nobody likes being lied to. The motivation, however, to not come back fighting and transform the sadness into rage and the rage into a comedy that only amuses ourselves is antisocial. It’s an unwillingness and/or inability to read the social situation, and it’s cynicism distilled. It doesn’t matter who, it doesn’t matter when. We believe that everyone is capable, more than capable, of badness, deceit, immorality and sadism, and what drives our utter lack of faith in humanity is the lie that people tell themselves to prove they would never display those traits. When someone shows their hand, a good person without a diagnosis, it’s double pleasure. It’s the pleasure of overcoming whatever pain you almost felt, and the exquisite pleasure of finally having your worst fears confirmed. Because after all, if it really is a dog-eat-dog world, as evidenced by someone else’s deceitfulness, then chaos can thrive. And, being justified, it doesn’t need to hide behind a mask. And it’s hard to trust a liar again. Our personalities are built around distrust, so the best we can hope for is to feel/not feel that way, and make it work for us. That’s what ASPD is. That’s who we are. And for you, the thought that people are fundamentally bad and self-serving might be a terrifying prospect, so it would make sense you’d want to protect yourself from that. But for us, that thought is what protects us, and it protects us in more ways than you know.

#antisocial personality disorder#aspd#antisocial tag#antisocial personality disorder tag#aspd feels#actually aspd#sociopath#sociopathy#psychopath#dark triad#alexithymia#antisocial feels#actually antisocial

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

ENFJ w/ ENFP brother. Thank you for answering my question. I think you misread or read into things, like assuming I was meddling, when my Aunt reached out to me w/ her concerns. It wasn't prompted by me. Also, I've always been my brother's cheerleader, sending him random encouraging texts throughout his college experience and after. Cheerleading alone didn't get him the outcome he desired, and it's hard to see him or anyone else suffer and not do anything-especially when I've been prompted.

I debated whether to respond because your message was defensive and really missed the point. I will respond once more out of sympathy, but this will be the last time unless there is an obvious effort to overcome the defensiveness. Your focus is misdirected. You ask me for “immediate solutions” to your brother’s problem and resent what is said about your part; however, you are unable to articulate what the source of his problem is, and how can you solve a problem when you don’t know the cause? My contention is that you don’t understand his problem because you are unable to understand his perspective, otherwise, you would be able to help (and I stated that I believe your intention is to help though you chose the wrong methods).

Is it or is it not true that he has no confidence in you and thus won’t listen to you? The point you’ve missed is that it doesn’t matter how great your or my ideas are, they are completely useless if the poor state of the relationship does not allow you to communicate ideas with him. Therefore, the first problem that needs solving is not the job search but your relationship to him, specifically, why it is so broken that communication has ceased. Relationships are a two-way street. You point the finger at him as having the problem rather than looking at why the two of you have a problem. If you are unwilling to reflect on how you contribute to the dysfunctional relationship and want to pin all the blame on him for “misinterpreting” you, then stop reading now, because then we fundamentally disagree about the facts of the problem. I was outlining common Fe vs Fi issues so that you could reflect upon possible dysfunctional patterns in your relationship with your brother, nothing more, nothing less. You mistook it as “blame” and became defensive. My response hasn’t substantially changed:

Your aunt reached out to you with her concerns about him. Are you suggesting that this gives you license to involve yourself in their relationship despite the fact that it is none of your business and he won’t listen to you (i.e. you are unable to offer a useful solution)? Are you aware that you always have a choice to stay out of a situation when you don’t know what to do? Are you aware that you could cause unintentional harm when you try to help without having all the facts (and thus appear to be siding against him or ganging up on him)?

You state that you don’t think of anyone as being “broken” and have been nothing but a “cheerleader” to your brother. Are you rewriting history to conceal your missteps (something Se loop+Ti grip often does)? Why then does he react so negatively to your “help”? Why then does he explicitly have to tell you to stop it with your “unsolicited advice”? Why then does he feel compelled to “prove you wrong” about him? Are you suggesting that the problem lies entirely with him and his inability to understand you? Are you suggesting that he’s making you into an enemy without any provocation whatsoever, i.e., that he is entirely at fault for the breakdown in this relationship?

You say that you understand some people don’t like to ask for help but that you are always receptive to help when offered. Are you suggesting that, if this is true for you, then it should also be true for him, or everyone for that matter? Are you suggesting that because your brother is not receptive to YOUR brand of help, then he is not receptive to ANY help?

You said you gave him suggestions that “play to his strengths” and you don’t understand how it could be misinterpreted as negative. Did he ask you for suggestions? Did he express to you that he wanted your “random encouragement”? If not, why are you giving unsolicited advice/comments, especially when he has explicitly stated that he does not want it?

You said that your advice to get a temporary job was “meant to imply that you have faith in him”, even though I explained to you in detail why this kind of “fixing” advice is destructive to FPs and directly undermines your stated goal (of letting him know that he can move at his own pace). Are you suggesting that there is no need to reflect on how your communication is received because your “intent” is the only thing that matters and people should “just know” exactly what you are “implying”?

You asked me to let you know if your “Ti is off”. You should use Fe, not Ti, to feel people’s feelings and understand them. From exercising healthy Fe empathy, you will be far better situated to know what he really needs (as opposed to guessing, making blind assumptions, or projecting from your own expectations). Ti, especially the lower Ti style of “dissecting and defending”, does not help because it usually serves to worsen ENFJ personality problems, such as: trouble empathizing, egocentric perspective, hypercritical me vs them attitude, self-victimizing rumination, oversensitivity to criticism, miscalculation of cause and effect, misdirection of blame. Misusing Ti such that it shuts down proper Fe use is the wrong direction to go in.

You’re essentially wanting me to look at him without looking at you, which I believe is useless when your dysfunctional relationship is the biggest obstacle at present. I will speak in the abstract if it is less threatening:

If an ENFJ often suffers from: Fe insecurity that takes everything too personally and doesn’t know how to draw appropriate relationship boundaries, Ni presumptuousness/arrogance that is resistant to deep self-reflection, Se loop twisting of facts and overreaction to negativity, and/or unnecessary Ti grip defensiveness and blame, then the ENFJ is NOT in a good position to provide an ENFP the kind of unconditionally supportive emotional environment that they require to practice self-care and nurture Fi development.

One cannot be helpful without getting a good idea of where the other person is coming from, and one cannot know another’s perspective when their own issues are constantly getting in the way. Whether you suffer from these common ENFJ problems is your job to reflect on; whether these common ENFJ problems create obstacles in your relationships is your job to reflect on - I have absolutely no interest in making these judgments for you or about you. You don’t seem to know that Se loop is negative, you mention “Ti loop” instead of Ti grip - misusing terminology makes your knowledge of function theory appear quite lacking. Fear of brokenness is an unconscious low Ti related fear that makes ENFJs want to defend and deflect blame when criticized rather than reflect constructively on how they can improve (i.e. resistance to Ni and Ti development). Suffering from Se loop and Ti grip directly interfere with the empathic Fe objectivity that ENFJs require to resolve relationship problems effectively.

He needs to develop Fi in order to grow, but you’ve shown that you don’t understand Fi, and worse, your tone-deaf Fe-Ti often offends his Fi-Te, so how can you help him with his Fi development? I reiterate these problems: You don’t display enough empathy for his feelings nor deep understanding of his perspective; you suggest “fixes” before you’ve even understood what his problem really is; you shoot ideas/comments at him without knowing how they make him feel; you give him the form of help that YOU believe he should need or that YOU should want if you were in his position (but he’s not you). Are you aware that these behaviors, even when well-intentioned, are counter-productive to building a good relationship between FJs and FPs? Be brutally honest, do you learn mbti to increase your respect for how others think quite differently than you, or do you only learn it as a means to “manage people” into doing what you believe they should do? Are you prepared to reflect on yourself and change any problematic behaviors in an effort to repair the relationship with him so that he might be more open to receiving your help? If you believe that you have no reason to change anything and you should both just be responsible to yourselves and leave it at that, then ignore this entire message.

I don’t hand out short-term bandaids. The long-term solution is to mend your relationship, which means that you must listen to him with genuine openness and empathy - no judgment, no opinions, no blame, no advice, no suggestions, no fixes, no management, no overstepping boundaries - the way forward will naturally present itself when he trusts you enough to open up about his problem and talk about it authentically and explore ideas in a safe space. You can’t force trust, you have to earn it, so what have you done to earn his trust? Maybe the relationship is so broken that he won’t trust you no matter what you do, but there is no way for me to judge that matter, only he can tell you. Perhaps he has too many problems of his own to bother with you. The point is that you’re not able to pinpoint exactly what the problem is between you because you don’t have his perspective.

If you genuinely wanted to get at the truth of your relationship problem, it wouldn’t be very difficult to ask for his side of the story and, without rushing to judge or defend, LISTEN to how he has been impacted by your behavior toward him, then you would know exactly what needs to be changed in order for him to start taking you seriously, then you’d at least know where to begin and have a chance to consider all your options. Are you able to approach him with genuine humility and openness, such as: “I feel sad about our distant relationship. Have I done something to push you away? Have I done something wrong? Is there something I can do to repair the relationship? Is there something you believe I should change in order for us to get along better? How can I support you better?” Are you able to listen to his truth and respond maturely to it? If not, how can he trust you and how can you help him?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empathy and You

essay by Therin Rose Lucas ⌂

I wave at absolutely everyone, have for a long time. I remember my friend once asked me why I did this, and we joked that it was a secret ploy to mess with people, that I wanted people to question if they had met me before. But there is no trick, no selfish intent, and in time I came to realize why I wave: it is a show of empathy. In fact, the majority of my daily interactions with other people are related to empathy in some way: my smiles, greetings, and hugs are all underlined by a feeling of empathy. I say it is empathy because performing such acts helps me connect to other people and show them goodwill.

By now, many of us, myself included, are asking what empathy is. While we would all agree that it is beneficial to ourselves and society, most of us would likely be at a loss for words trying to define it. And that is not a bad thing. Scientists, philosophers, and researchers have been trying to define empathy with words for years, and its true definition is still hotly debated. Many people want the universality of language to mold empathy into a recognizable whole. That is a valid desire, as a consistent definition would allow humans to understand and develop empathy more readily. For example, S. Natale, a researcher of empathy, presents his research toward establishing a method of teaching empathy to the general public in An Experiment in Empathy. He writes that “members of the general public were found to be functioning midway between levels one and two on a five-point scale of empathy” (15). This extreme lack of empathy drives Natale to perform an experiment in developing empathy. However, before he displays his research, Natale explicitly outlines the specific definition and parameters of empathy used in the experiment. Because of the nature of science as a consistent and repeatable process, he must use a single definition. In this way, a universal empathy is much more open to proper study and debate. Ezra Stotland and his colleagues likewise base their research in measuring empathy in Empathy, Fantasy and Helping on a single definition. They also express that “[t]he meaning and measurement of emotion is crucial” (12) in regards to said definition. In other words, they must always measure and define emotions and empathy consistently throughout the experiment.

While Natale and Stotland both follow the principle of carefully keeping to one definition, their empathies are not quite the same. For instance, Natale’s first phase of empathy involves “the ability to sense the emotions of another person” (16), while Stotland’s definition includes the “observer reacting emotionally” (12) to another’s emotions. To sense and to react, while related, are two separate actions. “Sense” does not imply that the person reacts—visibly or internally—to said sensation, while “react” does. Moreover, Natale splits empathy into three distinct phases, while Stotland relies on a single, more broad definition. It is difficult to judge the quality of both definitions, but the fact remains that despite their differences, they are both employed in important research and experiments. And both sets of research aim to expand our understanding of empathy. If their definitions were one and the same, such discrepancies would not exist.

Or would they? Natale uses his definition to learn how to teach empathy, while Stotland uses his to develop a method of quantifying empathy. Even if the definition of empathy was the same for both, their goals are a guiding factor in how they gather and interpret their data. Furthermore, Natale and Stotland are different people with different experiences, so this same definition would most certainly have a different meaning to each of them. And they would likely describe this underlying meaning with different words as well.

Many other concepts have been referred to as ‘empathy’ before. Daniel Batson, in his essay “These Things Called Empathy: Eight Related but Distinct Phenomena,” compiles a helpful list and analyses of several of these concepts. He explains that such a comparison helps “reduce confusion by recognizing complexity” (8). Essentially, if we are to discuss empathy, we need to disentangle the various concepts we call “empathy” from each other. He also claims that the term empathy is applied to a multitude of concepts in our attempts to answer two fundamental questions: “How can one know what another person is thinking and feeling? What leads one person to respond with sensitivity and care to the suffering of another?” (Batson 3) Batson’s reasoning regarding these questions is valid, as humans have always been interesting in the inner workings of their minds and those of others. What Batson does not mention is that these questions, lingering in the back of humanity’s collective mind for decades, are a cause of our difficulty in creating a universal empathy because they have ambiguous answers. Uncertain questions are subjective; uncertain answers are subjective. And subjectivity means many interpretations, as seen in the comparison of Natale’s and Stotland’s works. But, most importantly, subjectivity inhibits the concept of a fully objective definition of empathy.

Some have embraced this subjectivity. Leslie Jamison, for example, in her book The Empathy Exams, presents several scenarios involving empathy in both her fictitious medical patient lives and her real one. But ultimately, her stories do not culminate in one overarching meaning of empathy, nor does she intend them to. Instead, she interprets empathy based on her own feelings or the backgrounds of her patient roles. It changes depending on the scenario given. Her first interpretation of empathy emphasizes this fluidity: “empathy requires inquiry as much as imagination [and] means acknowledging a horizon of context… beyond what you can see” (5). Jamison believes that empathy is not a fixed, quantifiable object of our psyche, but rather a dynamic body that relies on both context and imagination, two variable attributes of any interaction. And Jamison is right to accept empathy’s changeable nature, because context and imagination are rarely neutral variables. Context is the setting in which events present themselves to someone. While it can be objective in the sense of foundational facts or clear societal labels, context often involves the personal and internal perceptions and reactions of those involved, which are not objective. Imagination is likewise a highly individualized notion that, given no bounds, can go almost anywhere. If we are to rely on context and imagination to be empathetic, then subjectivity will invariably dominate such interactions. And if this is the case, objectively defining empathy may very well be impossible.

Many would argue that the act of putting empathy into words means making it objective, but I would disagree. We may speak the same language, but it is not right to say that we interpret this language rigidly or equally. English has many words that, from an objective point of view, have the same meaning but, in practice, have differing meanings because of context. Context makes words and ideas subjective because the same situation, the same words, are colored with a different coat of paint each time they are utilized, and each time they are experienced. As appealing as this diversity may seem, there are inevitable issues involved with such fluidity. Friedrich Nietzsche recognizes these problems in his essay “On Truth and Lies in an Extra-Moral Sense.” His essay overall concerns the underlying subjectivity of human languages, but in one paragraph he directs his criticism at “the formation of concepts” (Nietzsche 61). He claims that the terms we use for abstract concepts are supposed to “fit innumerable, more or less similar cases… in other words, a lot of unequal cases” (61). Essentially, he means that these terms are meant to characterize a whole concept, and yet are built up from wholly different and unequal examples. He further adds that such language practices undermine a concept’s true meaning because the definition of it that is given is unclear.

Empathy is much the same as the terms described by Nietzsche: a word that is required to describe many situations that ultimately have many differences. As it stands, empathy is now considered by many to be an ‘umbrella’ term. It is used to classify many smaller, more particular terms, but it itself is vague and generalized. Jamison’s example as a medical actor reflects this when she acknowledges the evaluation “checklist item 31” (3), which is “‘Voiced empathy for my situation/problem’” (3). She points out that since the item is ultimately about “say[ing] the right words” (Jamison 3), many of the students use vague and rigid phrases such as “that must be really hard” in response to what would be overwhelming and stressful circumstances. Jamison’s example shows that, in this case, the usage of the term empathy is a problem. Empathy today has become such a broad concept that when confronted with it on a test, many students are unable to decide what it means, and instead use vague phrases in the hope that they will work. This is not empathy’s fault, as its broadness is the result of the subjectivity we apply to it every day. Empathy is waving at someone; now, it is holding the door for someone; now, it is saying a greeting; now, it is buying your hungry friend food; now, it is a compliment. These may seem like similar actions, and some of them are, but they are still different actions with different contexts, connotations, and outcomes. And more than that, these same actions are performed by a multitude of unique and personalized individuals every day. Even if two actions seem in every sense identical, they are still performed by different people. As a result, subjective empathy is as hard to comprehend as objective empathy.

If empathy cannot be one or the other, what if it is both? In our need to classify empathy so precisely, we have overlooked another option: empathy as a concept both subjective and objective. And such a thing is not impossible if we consider empathy on a personal level. Something personal is unique to a person, so subjectivity is present, but opinions and preferences are not solely based on a person’s feelings. A person is free to define empathy in their own terms, but that person likely does not derive such terms solely from internal forces. These terms also come from the people around a person, commonly held assumptions in society, and, in some cases, facts. Objectivity is present as well, albeit in smaller doses.

I do not mean to say, in my consideration of personal empathy, that humans cannot have a standard concept of empathy. Without such standard, we cannot teach new generations this vital skill and quality. It would even be a great notion to agree on a loose definition; but to confine this concept to narrow-minded and overly specific terms is to push away the understanding of our fellow man, for their empathy, however different, will always be empathy. Nevertheless, a definition that is too loose will grow to mean nothing, replaced by more specific and specialized terms. A balance is most certainly needed, and personal empathy is simply one way to achieve it.

Empathy is a strange concept. Sharing in the feelings of others? Feeling how others feel? Acting on such perceptions? It is a complicated puzzle of feelings, actions, and reactions that, even as science continues to advance, has never quite been solved. It is difficult to treat empathy as a neutral concept because of the varying ways in which it is defined and expressed. But if empathy is purely individualized, then it cannot be defined at all. We have all known about empathy since we were young children, but many of us have brushed it off as something we know and recognize, despite our inability to voice its meaning. But that inability should be an advantage, as it is exactly what gives empathy its flexibility. Because we cannot utter the definition, we simply show empathy, and see it, and react on it instead. We hug, we cry, we laugh, we thank, and we wave. And that is the beauty of empathy. It is not locked behind words with no meaning, or a door that cannot be opened—we have already found it. I have found that I wave because there are so many overwhelming days where that is all I can manage. So many days where I simply have too much to think about to do anything else. That is my flexible empathy at work. I show empathy in other ways, of course, but at my core, empathy, to me, is acknowledging other people, showing that I am thinking about them somehow, even if it is only through a hand gesture. This, too, may change with time. But that is me. And you are you. Your own brand of empathy, regardless of others, deserves to be seen. The world, now more than ever, is in desperate need of empathy. Rather than debate its meaning or judge others based on it, we should be showing it instead. So, show your empathy; the world will thank you for it.

Works Cited

Batson, C. Daniel. “These Things Called Empathy: Eight Related but Distinct Phenomena.” The Social Neuroscience of Empathy, edited by Jean Decety and William Ickes, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2009

Jamison, Leslie. The Empathy Exams: Essays. Graywolf Press, 2014

Natale, S. An Experiment in Empathy. National Foundation for Educational Research in England and Wales, 1972.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. “On Truth and Lies in an Extra-Moral Sense.” Oregon State U, oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl201/modules/Philosophers/Nietzsche/Truth_and_Lie_in_an_Extra-Moral_Sense.

Stotland, Ezra, et al. Empathy, Fantasy and Helping. Sage Library of Social Research, vol. 65, Sage Publications, Inc., 1978. ∎

More on Therin Rose ~ Minerva’s Owl Homepage

0 notes

Link

The Literature of the Pandemic Is Already Here

For those engaging in quick-response art,

mess and chaos—not polished elegance—are the forms to best mimic a crisis that has no end in sight.

Intimations BY ZADIE SMITH PENGUIN BOOKS

And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again: Writers From Around the World on the COVID-19 Pandemic

BY ILAN STAVANS (EDITOR) RESTLESS BOOKS

A bleak fact of writing is that honing sentences is often far easier

than honing the thoughts they convey.

A corollary fact is that polished, elegant prose serves as a useful, if not always intentional, hiding place for half-baked ideas.

Walter Benjamin wrote that a key element of fascism

is the aestheticization of politics—

the concealment of bad thinking behind bright optics.

Even in fascist-free situations, the concealment principle is common enough that I have come to approach beauty and neatness in art with some skepticism.

So far, the nascent literature of the coronavirus pandemic has reinforced my distrust. Three assemblies of coronavirus-response writing—

Zadie Smith’s essay collection Intimations;

NY Times’ short-fiction compilation, The Decameron Project; and

the mixed-genre anthology And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again, edited by Ilan Stavans—

tell me why:

No one has had time to truly refine their ideas

about personal life

in a state of widespread isolation and existential dread,

and literature, even when political,

is a fundamentally personal realm.

It relies on the ability to channel inner experience outward,

and because no inner experience of the coronavirus pandemic could plausibly be described as complete, prose that renders it static and comprehensible rings false. In the shaky realm of literature reacting quickly to a crisis in motion, mess and chaos are the forms that speak best to painful realities.

Zadie Smith opens Intimations, which contains six short, beautifully structured essays written largely in her characteristically gleaming prose, by acknowledging,

“There will be many books written about the year 2020:

historical, analytical, political, as well as comprehensive accounts.

This is not any of those—the year isn’t halfway done.

What I’ve tried to do is organize some of the feelings and thoughts that events, so far, have provoked in me.”

So, instead of social insight, which Smith admits is not yet available, she chooses self-organization. The turn inward is entirely logical, but the structuring impulse does not bode well.

To be fair, Smith’s opting for order is unsurprising.

In fiction, she’s a master of structure and form. Traditionally, she has allowed greater looseness in her essays and criticism—I am thinking, for instance, of Feel Free’s shaggy, implausibly delightful “Meet Justin Bieber!,” which uses a pop-star meet and greet as an occasion to revisit Martin Buber’s I and Thou—but not in Intimations. Its essays are short, tight, and glossy: pleasurable to read, but coy and cagey with their fundamental subject, which is death.

Take “Peonies,” in which a startling, lush garden sets Smith thinking about human vulnerability to biology. In theory, “Peonies” acknowledges the creative and destructive primacy of nature over determination—which includes its primacy over art. To Smith, art and determination are nearly synonymous: “Writing,” she explains, “is control. The part of the university in which I teach should properly be called the Controlling Experience Department. Experience … rolls over everybody. We try to adapt, to learn, to accommodate … But writers go further: they take this largely shapeless bewilderment and pour it into a mold of their own devising. Writing is all resistance” to experience.

Of course, this is not true for all writers. Some seek to portray bewilderment rather than shape it into reason. Smith attempts to do the former in “Peonies,” but when it comes time for her to wrangle with the crushing confusion and helplessness that disease generates, she bails on her project. The coronavirus appears explicitly in “Peonies” only once, not named but described as our “strange and overwhelming season of death”—and the moment Smith mentions it, she arrives at her argument’s end. “Peonies” is a conventionally structured literary essay, which means, as we learn in high school, that its conclusion recapitulates its beginning. Rather than continue thinking about overwhelming death, Smith returns to the place where “Peonies” began: a flower garden, and the stifled yearning for disorder that it provokes.

“Peonies” is not the only essay in which structure helps Smith turn from death. “The American Exception,” a linear, op-ed-style argument, addresses death as a mass phenomenon, but never as a personal one. “Something to Do,” a reflection on why writers write even in crisis, reads like the first portion of a writing-workshop lecture. In “Screengrabs (after Berger, before the virus),” Smith returns to the section-heavy style of her 2012 novel, NW, in which neat, titled chunks of narrative replicate the unwillingness of her hyper-controlled protagonist, Natalie, to engage with emotion. But here, Smith is the one unwilling to engage.

In its premise, “Screengrabs” does reach for emotion: Six of the essay’s seven sections are nonfictional character sketches in which Smith implicitly says goodbye to her New York life’s minor players before leaving to shelter in London. The essay is faintly elegiac—as I read, I could not escape thinking that its subjects, even the man who insists, “I survived WAY worse shit than this,” might not survive the virus. But its fragmentary structure lets Smith stop short of expressing grief. The form demands that she move quickly, even as its content might more fully emerge if she slowed down. The lone exception is the seventh section, titled “Postscript: Contempt as a Virus,” in which Smith describes and mourns the killing of George Floyd. Here, her dealing with death is not fleeting or abstract. Her prose is ragged and free of ornament; her consideration of racism as deadly contempt is the only idea that Intimations sees through from beginning to end. The reason seems clear: Floyd was killed in late May, and I received my advance copy of Intimations in mid-June. The section was evidently written quickly, but it emerges from centuries of American history. Smith has no need to hide behind structure here.

The Decameron Project has a bigger problem than a proclivity for organization. Many of its 29 stories are emotionally neat and one-note. Etgar Keret’s contribution, “Outside,” is unique in that its neatness is negative: Keret’s narrator squashes the common and sustaining dream of post-pandemic empathy and solidarity, asserting cynically, “The body remembers everything, and the heart that softened while you were alone will harden back up in no time.” Other contributors take the opposite approach, pursuing positivity and beauty at the expense of honesty. Take Alejandro Zambra’s “Screen Time,” in which the small graces of family life—watching a toddler sleep, conducting a fingernail-growing race—outweigh the stresses of quarantine, which Zambra describes with less imagination and in less detail. The mother in “Screen Time” manifests anxiety primarily by no longer “reading the beautiful and hopeless novels she reads,” which may reflect a common desire for optimism. But Zambra’s apartment-size world is too sweet, its calm too accessible and unexamined. The result is charming, but, for me, unconvincing.

Still, the Decameron Project does contain successes. Rachel Kushner, Téa Obreht, Leila Slimani, and Rivers Solomon all smartly smuggle very good stories about older, different topics—storytelling, exile, storytelling again, incarceration—into coronavirus frames. Only Tommy Orange dares an actual portrait of quarantine in “The Team,” which wobbles like a kid on her first two-wheel bike. Its language is often confusing, sometimes ugly. Words tumble from its narrator, who monologues about time, turkey vultures, marathons, pig slop, racism, Oakland housing prices, and more, with no plot or connective tissue between each topic but the speaker himself. The result demands attention simply by virtue of the narrator’s need to be heard. It has no moral or fixed meaning; to borrow Zambra’s formulation, it offers neither beauty nor hope. Yet as I read its description of time ticking past in quarantine, as “hidden and loud as the sun behind a cloud,” I felt a jolt of recognition. It is like that, I thought. Orange’s messy descriptions and run-on sentences, alone in the Decameron Project, offer small new truths.

And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again, a genre- and border-crossing anthology of mostly translated reactions to the coronavirus, is full of mess. In fact, the editor Ilan Stavans seems to invite it. He juxtaposes styles—poetry next to literary criticism, experimental fiction next to personal essay—in a way that is consistently disorienting and sometimes jarring, but pleasantly so. He permits political contradiction: In one contribution, Mario Vargas Llosa lauds Spain’s quarantine protocols, while in another, the translator Teresa Solana expresses terror at the Spanish government’s treating the pandemic like “a war, establishing a military scenario and using bellicose language with patriotic resonances.” If Stavans’s goal were coherence, he might have cut one piece, but he lets both remain, offering non-Spanish readers multiple views of a country unclear about its path forward—and implicitly accepting his own lack of knowledge.

Uncertainty is a driving theme in And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again. So is brokenness: broken bodies, hearts, medical systems, immigration systems, and more. Lynne Tillman takes a Tommy Orange–like approach to the breakdown of time, writing hectic, unadorned prose that turns into a breathless pileup: “I am exhausted, lie down, sit up, touch my toes, swing my arms, make a phone call, ignore a call, hear a voice, see a message, answer it, don’t, there is plenty of time, too much time.” Tillman’s sentences are cramped, confined, and unbeautiful. They don’t try to impress the reader. Reading her contribution generates the same restless boredom a writer—or any inessential worker—might feel while pacing the same apartment for the 100th day, knowing that there’s nowhere to go. So does the French Tunisian writer Hubert Haddad’s, which takes the pileup strategy much further. His story is a collage of fictional “false starts, drafts, approximations, [and] broken-off openings” that describe and evoke the “hazy driftlessness” of quarantined life. Its choppy, static structure captures the dysfunction of pandemic time.

In a May essay on coronavirus journals, the New York Times book critic Parul Sehgal described the diaristic impulse as “beautifully ordinary.”

Records of quarantine may be banal, she writes, but their very existence is reassuring enough to be lovely.

In other forms of writing, however, beauty is not enough to comfort.

In fact, it runs the risk of

trivializing,

distorting, or

evading the crisis it portrays.

Thus far, the coronavirus literature that works best admits certain truths about life mid-disaster:

The news is terrible and relentless.

Nobody knows what will happen.

The search for a vaccine is ongoing,

as is the search for sources of hope and meaning.

Will the coronavirus pandemic lead to stronger social safety nets?

Better health-care systems?

Will it produce cohesion or despair?

We have no way to know yet. What true story besides an uncertain, unbeautiful one is there to write?

0 notes

Text

Inferences and Attributions

Inferences and attributions are abstractions, and it doesn't matter if the story told about the phenomena corresponds to concepts or objects, it's still all falls into the realm of the mind, as reality is fundamentally mental in nature. The idea of your perceptual experience of being a physical creature with a brain that produces consciousness which can recognize an object and attribute reality unto it, is an experience experienced in a mental context. Physicality finds its context within the mental, and is received existentially as such, and then the stories we tell about it are yet even more workings of the same mental facility. And conveying a cold clinical hard scientific description of reality doesn't make it any less of an absurdity, even at the most mundane face value. Reductionism doesn't make it any less of a complete fantasy. But we forget this, and start believing in our own descriptions and narratives, as if they really mean something beyond being simply a fabricated experiential illusion. We don't like to think about it like that, you dig? We much rather think of it as real and actual, which, oddly, in this case, means independent of the mind. It has to be that way in order for me to believe I'm real. If it's only a contrived experience then it doesn't have the same authenticity. It isn't as important. There is more importance to things if they exist independently of me. And this is why we try to explain away this unexplainable experience with objectivity. It adds a layer of security and comfort. And with objectivity, the name of the game is inference and attribution. In other words, the source of existence is external to awareness, something that can be ascribed to some outside factor in sensory information, beyond your own mind. And this conclusion can be established, sustained and verified by inferring; that is, using a conceptual tool to build a knowledge based on interactions with sensory information with an assumed premise that the sensory information isn't in fact just sensory information, but is in fact an actual object, onto which reality can be attributed. See how it works? But, unfortunately, . The truth is the context, not at the phenomena within the context, nor the abstractions that seek to organize the phenomena conceptually. Inferences and attributions; mere ideological rationalizations. And this has become the main issue with intellectual exercise. For, you see, the problem with philosophy is that it compels a subject to think. And so, as many of you are probably wondering: how is that a problem? Thinking is good, isn't it? It's logical. It's rational. It's reasonable. It's common sense. And how much better if the subject is a free thinker. Or better yet, a positive thinker! Or better even still, an outside the box thinker! These are the proper intellectual tools considered to be the most refined exquisite attributes ever to be desired... Yes yes, of course. But, as we have already recently established, intellectualism is a veritable handicap within the spectrum of the pure mind. In a realm where the narrow passage to freedom is facilitated through the implementation of unlearning, "thinking", is a counter productive utility. Not to mention that the more common characteristics often associated with advanced intellect are not as compassionate as one might be inclined to believe. If anything, it's been continually demonstrated to be quite the opposite: as, more often then not, we find a certain degree of psychopathy, a lack of empathy, and a cold calculated mindset, bereft of sympathetic sentiments, to be the most prominent features to accompany a high intellect. So intellectualism is not all that it's cracked up to be. It can be a useful instrumentation, to be sure, but certainly not a be all end all application that is the best tool for every job.

Tool for a job? Yes, I know this is a perplexing metaphor, as many of you have elevated the status of the voice inside your head to a lofty position, fancying the thinking mind to be your very identity... of which is the real true perplexity. As we've already seen from the premature camping grounds of methodological solipsism and the implications of Rene Descartes's I think therefor I am, establishing an identification with the thinking function doesn't go nearly deep enough. Let us not forget that which gives the narrating dictator it's context. Ah yes, the most obvious thing in the worldj that's completely overlooked, remember? Just in case you were having a little trouble sorting it out from all your bullshit. No, never mind all that noise. You are that which provides the framework, not any of the phenomenal content within the frame... which includes your abstractions.. of which, is just intellectual narrative; nothing more. A story you tell yourself to keep a brace face. The yarn you spin to hold your head up high, and to help keep hope afloat. I understand. But it isn't an identity. Now some gurus out there might tell you to simply observe your thoughts, and while this may be a good exercise to warm up for the bigger game, it isn't nearly sufficient enough to bring the disturbance to stillness. You really might kinda wanna, begin to allow this condensed conglomerate of tension a modicum of freedom so that it might find the space and room to breath, in order for it to have a chance to establish some long needed stability. The mind perceives an experience as a means to pretend it has a nature. The mind cannot settle down because it is afraid; afraid of its own permanent changeless unqualatative and unquantitative formless constancy. You are an expression of a thing, what the essence could never really be: a thing with shape, location and a sense of finality. So there is an idea of a physical manifestation that is in quiet desperation, as the unlimited contrives it's own helplessness as the necessary contrast needed to recognize a self distinction. There is always ever one, but there is a need to create the illusion of another in order to even be able to acknowledge this one. It's a sticky situation. So fear is the fuel of thoughts. Now does that mean we have to police our thoughts or guard our thoughts, or to be hyper vigilant about the content of thoughts? Of course not. You can't necessarily control the composition and subject matter of your thoughts, but you can certainly bring the mind to stillness, which ceases production of thoughts, as a still mind is no longer transfixed in a stupor of fear. Nothing brings a more serene calm then a still mind at rest, completely accepting of it's true nature.

0 notes