#it’s SO rare and good to see such significant representation in dramas here

Text

on racial representation in entertainment casting

Film and television production companies of both the old and new types have been working hard in the last ten years or so to create more equality of racial representation in their output, and this is on the whole a good thing. No liberal and substantially multiethnic society can afford to have an entertainment culture in which, to paraphrase the remark of a critic of the 2015 Academy Awards, members of a society's different races do not see themselves importantly reflected in mainstream entertainment culture, and in more than a niche or token way. (In other words, a tradition of comedies revolving around black culture -- much less long-ago trends like blaxploitation films, or an obligatory Asian cast member in every buddy movie and so on -- does not suffice.) Productions striving to make this adjustment mostly fall into several types ... of which the last presents a creative/reception puzzle of a sort.

(1) Historical productions, or films with any point to make about social issues, will show historically accurate racial distributions (eg, films about American slavery or Vietnam, or a film like Fruitvale Station) -- though these productions may also sometimes seek to upend historical expectations about those distributions (highlighting, for example, the role of African immigrants in Victorian England).

(2) Some productions seeking outright to confound conventional racial casting/character expectations will make clear choices -- eg, Hamilton, the "colorblind casting" of Bridgerton,* or Daniel Oyelowo in Lear.

(3) Productions set in the present day with no particular racial point to make -- a romantic comedy, a political thriller, etc -- will generally show a racially distributed cast, given a multiethnic setting (London, New York, etc), attempting -- with mixed results -- to push the tokenism of the nineties into more substantial territory.

But the puzzling case is (4) - science fiction or fantasy productions. These will generally try to show the same racial distribution as (3) -- central characters who are black, Asian, Latino/a, as well as white (usually, of course, with a complementary distribution of gender and perhaps age). The reason this distribution is significant here is that it is present no matter the other fictional facts about the society portrayed. Whatever the social problems of Earth in some distant future, whatever the ethnic tensions of a medieval fantasy kingdom, the casting overlays on these a harmonious, backgrounded, and fictionally insignificant distribution of race - which is nevertheless meant to carry the requisite political significance, creating a basis of real-world acceptability for the production.

In other words, there will never be a race-based conflict between a white and a black character in such a production. Unless, of course, there is a 'historical' point to make -- usually in a science fictional future, such as that of Blade Runner -- or in a production meant as a parable of real life race relations now, and such productions are rare: few creators seem to want to contemplate a future in which actual racial problems remain unsolved, even if conflicts between imaginary races are used as parables of the present day. (Though, interestingly, producers of shows such as that made after Atwood's The Handmaiden's Tale are willing to contemplate a future still predicated on gender inequity.)

The reason that this distribution produces an odd effect is that very often, and naturally enough from a creative perspective, some strife or other between fictional races, ethnicities or classes is depicted in such productions - the stuff of wide-angle drama. And yet each faction involved -- a working class on Mars, say, versus an Earth aristocracy in The Expanse or other productions, or tension between the races of Elves and Men in the new Tolkien serial -- shows a generally diverse real-life racial distribution among the actors cast. In other words, the actual race of actors is played in the fiction as a nonentity, and so real-life race is never used to show the fictional divisions. (Cases where this has happened, as when Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films very nearly fell into the trap of Tolkien's midcentury racial stereotyping of certain Middle Earth peoples, or with George Lucas' disastrous Phantom Menace-era use of human racial types to characterize various alien peoples, can be regarded as important lessons, and dead ends.)

The oddness of viewing these programs is that perfect racial harmony, diversity, assimilation, and equity seem to be assumed as both foundational and irrelevant to whatever else is going on. Eg, perhaps Men and Elves are again headed for war in The Rings of Power, but there are real-life skin colors and racial traits of all types to be found in both camps, working side by side as fictionally appropriate -- so we get to enjoy the drama of the fictional conflict while also enjoying a fictional resolution of the real-life ones. It is the latter half of that formula, of course, that may present difficulty, but certainly it is currently hard to imagine an alternative.

*Bridgerton presents an interesting and increasingly typical case: the casting, its champions say, draws attention to the underacknowledged role of black people in Regency England (a variety of the (1) type above) -- and this is completely plausible. What is less plausible is the claim of which many supporters stop barely short, that what is shown is actually historically accurate. The production exaggerates to make a point, nor does it require a whole series (set in a country where slavery was never territorially legal) to make the point that "black people weren't only slaves," and that does seem to be some people's justification for the production.

(In one way, such a justification is analogous to the sleight of hand in the fantasy / sci fi shows, where one says, let's take on the important issue of fantasy racial conflicts, in a medium undergirded by real racial harmony ...)

Why the historical veracity claim should be important to the politics at stake is a mystery - a fictionalization of history in order to turn the prism on race is completely valid, and needs none of the memory-holing of actual history to be important and urgent.

0 notes

Text

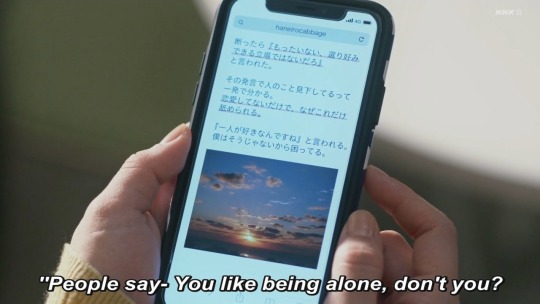

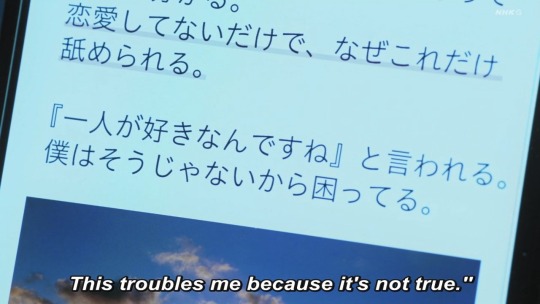

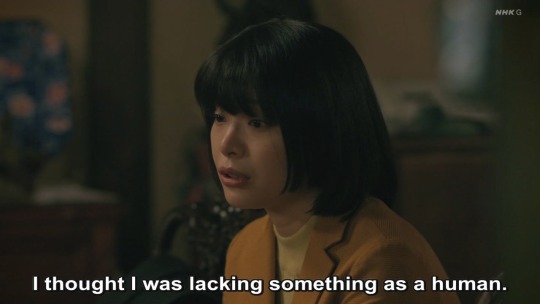

if you have time, please watch the japanese drama 恋せぬふたり (koisenu futari; the two people who can’t fall in love) which focuses on two aroace characters

Sakuko finds it difficult to live in a society which operates under the assumption that people will fall in love with each other. She meets supermarket employee Takahashi when she goes to support a "fall-in-love" campaign by her junior at work. She is startled when she hears him say that there are people who don't fall in love. As Sakuko's mother keeps hurrying her to get married, she decides to move out and rent an apartment with her friend but her friend backs out at the last minute after reconciling with her ex-boyfriend. Just when Sakuko is about to give up, she ends up living with Takahashi under one roof because of their similar values towards romance.

(how to watch)

#it’s SO rare and good to see such significant representation in dramas here#koisenu futari#jdrama#asexual#aroace#lgbt#lgbtqia#activism#pride#happy pride#pride month#aromantic#lgbtq#international asexuality day#adding the how to watch it part for those asking

27K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life Detained.

The Mauritanian director Kevin Macdonald talks with Jack Moulton about researching Guantanamo Bay’s top secrets, Tahar Rahim’s method-acting techniques, the ingenuity of humanity during the pandemic, and his favorite Scottish films.

“You’ve got to understand that for a Muslim man like Tahar, this role has a much greater significance than it does for you or me.” —Kevin Macdonald

It’s not uncommon for a director to release two films in one year, but Academy-Award winning—for his 1999 documentary One Day in September—director Kevin Macdonald is guilty of this achievement multiple times. Ten years ago, he released his first crowd-sourced documentary Life in a Day and the period epic The Eagle within months of each other. A decade on, he’s done it again.

The Scottish director (and grandson of legendary filmmaker Emeric Pressburger) released both his Life in a Day follow-up and the legal drama The Mauritanian this month. The latter tells the story of Guantanamo Bay detainee Mohamedou Ould Slahi (sometimes written as Salahi), who was held and tortured in the notorious US detention center for fourteen years without a charge. The film, adapted from Slahi’s 2015 memoir Guantánamo Diary, features Jodie Foster and Shailene Woodley as his defense attorneys Nancy Hollander and Teri Duncan, with Benedict Cumberbatch, who also signed on as the film’s producer, playing prosecutor Lt. Stuart Couch.

Benedict Cumberbatch as prosecutor Lt. Stuart Couch in ‘The Mauritanian’.

The Mauritanian also introduces French star Tahar Rahim to a global audience, in the role of Slahi. “The ensemble is excellent across the board,” writes Zach Gilbert, “while Tahar Rahim is best in show overall, bringing honorable heart and humanity to his role [of] the titular mistreated prisoner.”

Much of the story is filmed as an office-based legal thriller involving thick files, intense conversations, and Jodie Foster’s very bright lipstick. Macdonald expertly employs aspect ratio to signify narrative shifts into scenes recreating Slahi’s vivid recollections of torture and his achingly brief conversations with unseen fellow detainees.

Qualifying for this year’s awards season due to extended deadlines, The Mauritanian has already earned Golden Globe nominations for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress for Rahim and Foster respectively. Slahi remains unable to travel due to no-fly lists, but he was a valuable resource to the production, providing an accurate and rare depiction of a sympathetic Muslim character in an American film.

It was the eve of Life in a Day 2020’s Sundance Film Festival premiere when we Zoomed with Macdonald. Behind him, we spied a full set of the Italian posters for Michelangelo Antonioni’s classic Blow-Up. As it turns out, he’s not a fan of the film—only the posters—so we got him talking about his desert-island top ten after a few questions about his new film.

The attention to detail on Guantanamo Bay in The Mauritanian is impressive. There are procedures depicted that you rarely see on-screen. How did you conduct your research?

Obviously Guantanamo Bay is a place which the American government spends a great deal of effort keeping secret. It was important to Mohamedou and me that we depicted the reality of the procedures as accurately as we possibly could. That research came primarily from Mohamedou who has an incredible memory. He drew sketches and made videos of himself lying down in spaces and showing how he could stretch half his arm out [in his cell]. There are a lot of photographs on the internet of Guantanamo Bay which are [fake] and others are from a later period because the place developed a lot over the years since it started in 2002 and Mohamedou was able to [identify] which photos were rooms, courtyards and medical centers he had been in.

Director Kevin Macdonald on set with Jodie Foster.

How did you approach creating an honest representation of the graphic torture scenes, without putting the audience through it as well?

Whenever films about this period are [made] they’re always from the point of view of the Americans and this time we’re with Mohamedou. You can’t underestimate the fact that there have really been no mainstream American cinematic portrayals of Muslims at all, so in portraying a sympathetic Muslim character who’s also accused of terrorism, you’re pushing some hot buttons with people. It was important that those people who are uncomfortable with him understand why he confessed to what he confessed.

Everything you see in the film is what happened; the only difference is that they weren’t wearing masks of cats and Shrek-like creatures, they wore Star Wars masks of Yoda and Luke Skywalker in this very perverse fucked-up version of American pop culture. Obviously, we couldn’t get the rights to those. Actually, I don’t feel that it is graphic. There is more violence in your average Marvel movie. It’s psychologically disturbing because you’re experiencing this disorientating lighting, the [heavy-metal] music, and he’s being told his mother’s going to be raped and he’s flashing back to his childhood. To be empathizing with this character and then to see them to be so cruelly treated is so deeply disturbing.

How did you prepare Tahar Rahim for his convincing portrayal of such intense pain and suffering?

Tahar went through a great deal of discomfort in order to achieve it. He felt that to give a performance that had any chance of being truthful, he needed to experience a little bit of what Mohamedou had suffered, so throughout the movie he would insist on wearing real shackles which made his leg bleed and give him blisters. I would plead with him to put on rubber ones and he would say “no, I have to do this so I’m not just play-acting”.

He starved himself for about three weeks leading up to a torture sequence—he had lost an awful amount of weight and he was really unsteady on his legs. I was very worried about it and I got him nutritionists and doctors but he was determined to stick with that. You’ve got to understand that for a Muslim man like Tahar, this role has a much greater significance than it does for you or me. He felt a great weight of responsibility to do this correctly, not just for Mohamedou, but he was speaking for the whole Muslim world in a way.

Jodie Foster and Shailene Woodley as defense attorneys in ‘The Mauritanian’.

What compels you to study this period in time?

Mohamedou was released a couple of weeks before Trump came to power in 2016, so the story is still ongoing for him. He’s still being harassed by the American government and he’s not allowed to travel because he’s on these no-fly lists. I didn’t want to make a movie that was saying “George W. Bush is terrible”. We’ve been there, we’ve done that. This is looking back with a little bit of distance and saying “here’s the principles that we can learn from when you sidestep the rule of law”—what it takes to stand up like Lt. Stuart Couch did when everyone else around you is going along with something that’s really terrible.

You see that around Trump with the choices within the Republican Party to stand up and say they’re going to sacrifice their careers to do the right thing. It is a hard thing when there’s this mass hysteria in the air. The basic principles that the lawyer [characters] are representing is not about analyzing and replaying what happened after 9/11, they’re directly related in a bigger way to the world we all inhabit.

Did anything surprise you in how your subjects for Life in a Day 2020 addressed the pandemic?

One of the most affecting characters in the film is an American who lost his home and business because of the pandemic, so he’s living in his car. He seems very depressed when you meet him for the first time, then later he’s telling us there’s something that’s giving him joy in his life. He brings out all these drones with these cameras on them and puts on this VR headset and loses himself by flying through the trees. I thought that was such a great metaphor for the way that human ingenuity has enabled us to survive and thrive during the pandemic.

I get the feeling of resilience from [the film]. This is a more thoughtful film than the original one. I see this as a movie of [us] being beware of our susceptibility to disease and ultimately to death and mortality, [and] how we’ve found these consolations as human beings. To me, it’s a really profound thing. It also speaks to the main theme of the film which is how we’re all so similar, same as The Mauritanian. It’s confronting you with all these people and saying we fundamentally all share the basic things that underpin our lives and the differences between us are much less important than the things we have in common.

Let’s go from Life in a Day to your life in film. What’s a Scottish film that you love but you feel is very overlooked or underrated?

That’s really hard because there aren’t many Scottish films and there aren’t many good ones. Gregory’s Girl is the greatest Scottish film ever made—it’s the bible for life for me. That’s very well-known, so I would have to say Bill Forsyth’s previous film That Sinking Feeling, which was self-funded and made on 16mm black-and-white. It has some of the same actors and characters as Gregory’s Girl in it. Or my grandfather Emeric Pressberger’s film I Know Where I’m Going! which is a rare romantic comedy set in Scotland.

John Gordon Sinclair and Dee Hepburn in Bill Forsyth’s ‘Gregory’s Girl’ (1980).

Which film made you want to become a filmmaker?

I think it was Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line, which is one of the top five documentaries ever made and in my top ten desert-island movies.

What else is in your desert-island top ten?

Oh god, don’t! I knew you were going to ask me that. I’ll give a few. I would say there would have to be something by Preston Sturges—maybe The Lady Eve or The Palm Beach Story. There would have to be a film written by my grandfather, so probably The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, which is the best British film ever made. There would have to be Singin’ in the Rain, which is the most purely joyful film I’ve ever seen. There would probably be The Battle of Algiers, which I rewatched recently and was an inspiration on The Mauritanian. Citizen Kane I also rewatched in anticipation of watching Mank, of which I was very disappointed. I thought it completely missed the point and was kind of boring.

Which was the best film released in 2020 for you?

I thought the Russian film Dear Comrades! was really stunning. It was made by a director [Andrei Konchalovsky] in his 80s who first worked with Andrei Tarkovsky back in the late 1950s. He co-scripted Ivan’s Childhood. I would love to make my masterpiece when I’m 86 too!

Related content

Films with Muslim characters

Movies that pass the Riz test

Scottish Cinema—a regularly updated list

Follow Jack on Letterboxd

‘The Mauritanian’ is in select US cinemas and virtual theaters now, and on SVOD from March 2. ‘Life in a Day 2020’ is available to stream free on YouTube, as is the original.

#kevin macdonald#michelangelo antonioni#scottish film#scottish director#emeric pressburger#the mauritanian#jodie foster#tahir rahim#tahar rahim#french actor#guantanamo bay#muslim representation#muslims on film#benedict cumberbatch#guantanamo diary#life in one day#life in one day 2020#life in one day film#letterboxd

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Essay on POC and Fics

[ORIGINALLY A WRITER ASK GAME]: Ramble about any fic-related thing you want!

(AKA me explaining in long-form why June is white, complete with some drama and a lot of rambling. Do not feel obligated to read).

.

I’ve never talked about this extensively, but I want to discuss ethnic minority OFCs in fics. Specifically, SiA. I originally was going to make June partially nonwhite. And I ran into problems.

I really found myself worrying about relatability. If a character is POC, I thought it would ruin immersion for people who are looking for an OFC fic to lose themselves in. It’s no secret that I’m Asian-American, and I was originally all for making the character part Asian. It’s ironic that I was worried about immersion when outside of fic spaces, I argue unendingly for Asians to be cast as leads and stereotype-defying roles. Because any POC is also just a person who can be as “relatable” as any white character, theoretically. I feel a little hypocritical, but at the same time it’s true.

When I watched The Walking Dead, Glenn was my absolute favorite. Because he was Korean-American. And for the first time, I watched a major (Asian!) character in a show become hailed as a man defined not by his race, but for his achievements and his personality. If Glenn was white, he still would’ve been one of my favorites. But seeing Asians portrayed as... normal people shouldn’t be this rare. However, it is, at least in mainstream America.

The issue with creating POC characters is racism. That’s always the issue, isn’t it? Racism has been ingrained into every system and cultural dynamic, globally. The remnants of colonialism are alive and well, and the treatment of POC people, generally, is far from sterling.

Thus it became almost impossible for me to justify creating an Asian-American (or, for that matter, any other POC) OFC. They would be defined by race, because back in the 40s, any American ethnic minority had no choice but to be characterized by their appearance. It still happens today. And I wanted the focus to be on humanity, war, bonds, and gender. Not race, because race is unpleasant to talk about. It wouldn’t be fun for me to be researching 1940s race discrimination to create a character who must overcome that too. I’m not looking to undergo an identity crisis in the pursuit of a fic aimed at social justice. I just want to write something fun.

Fic is created, many times, by minority groups, including POC. However, like any institution, it’s white-centric. And I don’t fault it for that. Most media in the mainstream is white-centric and thus it makes perfect sense for the works created based on the material to be also that way. But I felt like I was betraying myself by writing fic and not taking a chance to diversify the narrative.

Because if a significant part of my irl advocacy is attempting to champion race diversity, and I don’t take that chance in the fandom space, am I a hypocrite?

The fault of this culture, and this struggle, is not with me. It’s with the centuries and ages of oppression and typecasting and discrimination in the pages of world history. It’s unavoidable.

However, to be kind of frank, it sucks to have to consider these things when all I wanna do is write a self-indulgent narrative about WWII boyfriends. I want to just be myself and imagine a fun time with my favorite characters. But I know, deep down, that anyone who is not white would not have been accepted into the group. I decided to just circumvent all these problems by writing a white character.

And it’s not true to the narrative if I wrote a POC OFC and then bent all the other characters OOC and forced them to be non-problematic. Because I know, regrettably, that the norm back then (and still in some areas) is casual racism. It was only 1948 when the American Army officially desegregated. You can watch The Pacific for yourself and find out what the Americans called Japanese people. The racial slurs, I’ll admit, made me uncomfortable despite how much I love the series. Army culture in the 40s towards a woman who is also a racial minority would have been egregious. And that’s not fun to write about in a fic.

I can’t not think about race -- not forever, at least. I don’t have that luxury. I do acknowledge that I, as an Asian-Amerian, benefit from a white-centric culture that has designated us (condescendingly) as a “model minority” and as an exception race. Systemic racism is less impactful towards Asians. This is, however, not to discount the terrible history of Asian-American discrimination that is not immediately apparent (I have been told that not everyone is educated of the existence of the Japanese-American internment or other examples of irrefutable discrimination). There is history in my family of experiencing both ends of the Asian-American experience: as a “model” and also discriminated against as a perceived threat (or a scapegoat, if you will, for the Vietnam war and other matters).

I went through a phase (as many American POC do) of wanting to be white when I was very young. I don’t know exactly why. Is it because the American identity is so deeply rooted in the striking visual of the white settler, despite the deep history of the continent in indigenous people? Is it because diversity is (or was) not common in the mainstream -- when we didn’t have people like Glenn at the forefront of media representation but instead had stereotyped caricatures like Mr. Yunioshi? I didn’t know what it meant to be beautiful back then unless the portrait was of caucasian features. I have a distinct memory of complaining to my mother when I was about five or six years old that I didn’t like my black hair, and I think my way of thinking unconsciously had to do more with my Asian heritage than the actual color. I cannot tell you honestly what specifically caused this type of thinking, but it’s more widespread than you’d think among POC children.

So this is why I am a POC and yet I choose to write a white protagonist. Historical fiction always contains complexities: decisions that must be made with the wisest discernment that I don’t feel like I can always make. History is a burden upon us all. The present will never be free of the past, and it’s our job as writers to navigate the gray patches between interpretation and accurate portrayal. Sometimes it seems like an insurmountable task, and sometimes it’s as if I can forget about my POC-ness altogether and lose myself in my OFC without thinking about heritage or discrimination.

But here we are, writing fanfiction of WWII heroes who come from a different time and a different era.

It had to have felt different back then, don’t you think? When I think of the forties, I think of patriotism and B-24s and victory; I think of a feeling of hope tinged with despair. I think of radios and dance halls and tragic heroes and the glory of soldiers dropping from the sky, backlit like angels and tasked with democracy and hope and things that are right and true. I think of a time where Americans united for good.

But this is a glamorized version of history. It’s the enjoyable version, we all know. And it genuinely consisted partially of these snippets of greatness, but there was a larger part that lay, vast, underneath the golden panorama that sometimes we forget about. And I think the WWII fic-writing community is keenly conscious of this aspect. I see it in the writing that we all so lovingly produce: a lot of us understand, at least on a surface level, that war is not glamorous and that the times were still as turbulent as they are today.

It’s something we all must grapple with.

And this, in a slightly dramatic fashion, is my personal conflict of being a person of color, and choosing to write a white character for the sake of joy and fun.

.

Thank you for reading if you got to the end! I love you all :)

.

(Partially inspired by this post by @rhovanian, but mostly my own ruminations based on the brief time I have existed on this earth).

.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fuckening: Modern YA Fantasy Misunderstands Feminism and Effective Plot Structure

Alright, mother fuckers, buckle up. Like most book lovers, I read many books and I’m always searching for the next one that will make me develop a hyper-fixation. Nothing beats the rush of finding media so good that time loses all meaning and you’d sell your soul for the next hit of content. The amazingness directly results from being rare. So in between the moments of stuffing your face full of your favorite characters, the other books are read. The ones that could have been good but aren’t successful. The ones with the lying, beautiful covers used to lure readers into forking over crumpled cash while hugging the hopefully precious gem. Then, all the words are read and the covers are closed, and there’s only the silence of disappointment and mediocrity.

Anyway, I read a book. Shocking, I know. It had so much promise and as I delved into the first fifty pages; I thought I found a winner. Then it started to sink in a massive Titanic kind of way. This book was Wicked Saints by Emily A. Duncan (this essay/rant will have spoilers and will discuss the ending). I’m prefacing this rant with a disclaimer, not because I’m trying to side-step backlash, but because I feel it’s worth mentioning. This is all my opinion and if you loved this book with all your heart, that’s awesome! I understand why someone would spend time reading, writing, and engaging with it. It’s possible to recognize the weaknesses of a piece of media and still like it; I just happen to not like it because of those weaknesses. Returning to my point, the pitfalls, mistakes, and blandness of this book are rampant throughout Young Adult literature, particularly in Fantasy. As a writer myself, I’m not immune to committing the same sins, but I think it’s valuable to examine why and how these unfortunate tropes keep appearing. I have several points I want to explore in this essay, but the main two are the pretend feminist values and poor writing craft.

Part One: YA Book Feminism and Bland Female Characters

Wicked Saints is marketed as a book about a girl who can communicate with gods and draw power from them. Her magic is rare in a world full of blood magic users and as the war between her country, Kalayazin, and the opposing force, Tranavia, clashes on her front porch, readers are led to believe that she’s an integral part of how this war will end. I was here for this. I was so ready to scream about this book to anyone who will listen. Now, I’m screaming about it for a different reason.

Nadya, our human incarnation of the god’s Walkie-Talkie, is not like other girls. She’s special and powerful and exceptional. At first, I bought this lie, much like I did with every other book like this one. I thought, finally, here’s a badass heroine who will take charge of her life and wield her powers to create a lasting peace or at least kill everyone. When the readers meet Nadya, she’s living in a monastery to hide from Tranavians since her magic is so rare and powerful, they’re sure to seek her destruction. Then, they find her, or rather Tranavia’s prince, Serefin, (a boy-general, because adults don’t exist in YA) does. Serefin tries to kill Nadya, but she escapes with help of Forgettable Best Friend.

Lately, I’m reading a trend of books that build a “strong” female narrator by giving her some sass, adding a rare but useless magic, and having her not die. Then they slap words like empowering, feminist, or well-crafted into the marketing campaign and call it good representation. This isn’t quite what happened with Wicked Saints, but I had the impression that Nadya would be more than what she actually was in the book. The hardback cover has the words “Let them fear her,” engraved into it for gods’ sake. I thought she was going to at least do something.

Okay, there was one time she did something. While on the run from Serefin and the other Tranavians, Nadya and Forgettable Best Friend find a group of misfits being attacked. Nadya, in the confusion of who’s an enemy and who’s an ally, asks the gods for help. One responds by vanishing all light for like ten minutes or something. This scene is one reason I bought the lie that Nadya was going to be a Bad Ass Mother Fucker, but this is the only time I remember her using any kind of significant power. In fact, once the plot gets going, Nadya is cut off from her powers almost entirely. I’ll get to that later. Back to the group of misfits, which includes a broody, yet totally handsome Tranavian, Malachiasz, and bam, we’ve found the love interest. Malachiasz is a Vulture which I understood as a privatized military group that’s ruthless, skilled, and detached from the world (no family or friends). So, Nadya hates him on site, but Malachiasz has defected and has like emotion now. They argue a bunch and exchange heated glances.

Now that we’ve introduced our male characters (Serefin, Malachiasz, and some other dude in the misfit group), our plot gets going. There’s nothing wrong with introducing characters to start a plot, that’s how story-telling works. What I’m finding frustrating in this book and many others like it, is that the male characters make most of the decisions. They show the most autonomy and participate in the drama/action. Serefin is leading an army, making command decisions, and drinking copious amounts of alcohol (I don’t have time to get into the drinking to drown your feelings is Not Good argument, but know that this book doesn’t call out his addict behavior). Malachiasz and his band of friends are planning to assassinate the king. The female characters have run away, observed, and turned out the lights. Where is the girl who’s inspiring fear in the gods themselves? Where is the girl who’s fighting for justice and her future? Granted we’re only a hundred pages in at this point, so I’ll excuse it for now.

In the meantime, the king calls Serefin back to the palace for Rawalyk, an event where noble women compete against each other to win the prince’s hand in marriage. Nadya and crew travel to Tranavia and disguise themselves as people participating in the event. I forgot to mention that the Tranavians only use blood magic and hate the gods, and in an effort to keep them out, the king put a barrier around the country, which keeps Nadya from using her powers. Convenient. And so very disappointing. As per their plan, Nadya has to get close enough to the king to kill him, so she uses Rawalyk to gain access. Nadya offends one of the other suitors and the suitor challenges her to an Agni Kai—sorry, different story, a duel, rather. Nadya has to pretend to use blood magic, so she can hide her true identity. Near the point of winning the duel, Nadya realizes it’s to the death, but she doesn’t want to kill the girl, so she tells her she’ll spare her. Then, Malachiasz uses his magic to end the girl’s life. Again, there are male characters forcing the plot forward while the female character’s agency is stripped.

We’re now over two hundred pages in and Nadya hasn’t done shit except for worry about her crush and follow other people. Our narrator is a “powerful” girl, but the most interesting characters are boys and only male characters move the plot forward. I guess, who needs a personality or autonomy when you can have a love interest? To make matters worse, in the middle of all this crap, she’s thinking about her male best friend who died, but is coming back in book two, and not even Forgettable Best Friend who is actively trying to help them. Nadia thinks to herself “Kostya. You’re doing this for Kostya, she reminded herself,” (Duncan 256). Kostya was in this book for like five pages, who the fuck is this bitch? Why does anyone care? Why can’t she be going on this quest for herself, for her country, for her supposedly beloved gods?

YA Fantasies keep prioritizing and valuing the actions of male characters over female ones. There are exceptions, but they only prove the rule. I’ve seen this repeatedly in books like City of Bones, Caraval, Shadow & Bone, Harry Potter, and now Wicked Saints. Some of those books are my favorite books, but if I never critique them, I’ll never want better or search for books that do more. I want to see more YA fantasies treat female characters like their male ones. I want female characters who participate in the narrative, make mistakes, experience success, and, I don’t know, have some ambition and goals. They should use their talents and be integral to the plot, because Wicked Saints’ plot still could have happened without Nadya.

Part Two: Character Development and Effective Plot Structure

Let’s get into this dumpster fire of an ending. While staying at the palace and pretending to be a suitor to the prince, Nadya uncovers parts of Malachiasz’s past and finds out he’s the leader of the Vultures who’s disappeared for reasons unknown. Nayda gets captured and tortured and learns that her gods may not be who she thinks they are, and she has her own power that she can always use. And does she use it? Not really. She questions everything, but not Malachiasz. Him, she makes out with. Nadya’s group and Serefin’s converge and they trust each other because they both want the same thing: the king dead. Serefin knows his father is trying to kill him and uses the help of the misfits, including, plot twist, his cousin, Malachiasz.

Serefin doesn’t understand why his father wants to marry him off and plotting to kill him at the same time, and eventually, Malachiasz talks about his past. He became the leader of the Vultures and was researching the gods when he figured out, in theory, how to become one. He gave this information to the king and you can imagine how a narcissistic king will feel about that. Malachiasz regrets his actions and runs away. Part of the process of becoming a god involves ingesting the blood of powerful magic users, hence the Rawalyk event and Nadya’s torture; they were collecting blood from the suitors. The king also has to sacrifice the prince to complete his goals. Together, they come up with a plan to corner the king while he’s attempting to perform the ceremony to become a god and kill him.

It all goes spectacularly wrong. Serefin gets captured and killed by his father, but he doesn’t die? I don’t know; there were a lot of moths involved and I was very confused. Malachiasz and Nadya go after the king and there’s a mediocre fight scene. Nadya kills the king but not after like three pages of her debating why Malachiasz is just chilling on the throne and watching this all happen. Malachiasz betrays the group, taking the power for himself. Nadya has the nerve to be surprised and heartbroken. He turns into a bird-like thing and flies out the window into the darkness.

The only time Nadya uses her own magic to do something it turns out to be in service to a male character’s goals. I’m tired and I hope you are too. Anyway, this section’s purpose is to look at effective plot structure. Wicked Saints meanders for three hundred pages trying to tie together a book about war, marriage competition, and religion. When the plot points all converge for the last eighty pages, we ultimately learn nothing more than we did at page 200. If this is a book about villains than why are minimally bad things happening? Why did no one die except for the throw away character at the book’s beginning? Why aren’t there more consequences for the character’s actions? My questions are answered by pointing at the poor plot structure and terrible character development. This book is run by boring characters whose actions don’t amount to anything, and that’s when they actually do something. Characters should evolve or devolve depending on the narrative. They should enact the plot, not have the plot happen to them. The few times we get characters changing, it’s followed by the most basic plot twists. Looking at Malachiasz in particular, we meet him while he’s plotting to kill the king with his new acquaintances, then he meets Nadya. She calls him a monster a million times, and he doesn’t deny it. They plot to kill the king again. By the end, we find out he’s only in this for himself and surprise, he’s not a good guy! Did not see that coming.

Continuing my rant on Malachiasz, Wicked Saints has one of the poorest representations of anxiety that I have seen in a long time. (Note: right after this I read Truly Devious and boy, the whip lash I had from that transition. From one the worst to one of the absolute best). Before I rip into this terrible character development, let me discuss two things: one, I don’t know if the author suffers from anxiety. It’s possible that Duncan experiences it very differently than me, and this may be good rep for someone else (I have my doubts about this since I can shred it like wet tissue paper, but I’m willing to mention this possibility). Two, considering Malachiasz’s turn to The Dark Side, it may have been purposeful bad representation. Essentially, he never had anxiety, just needed Nadya to trust him. Okay, with that out of the way, let me scream this: ANXIETY IS NOT CUTE. IT’S NOT A FUN, QUIRKY CHARACTER TRAIT. PLEASE FOR LOVE OF MEDUSA, STOP USING MENTAL ILLNESS AS A CRUTCH FOR YOUR INABILITY TO WRITE COMPLEX CHARACTERS.

The only thing we know about his anxiety is that he bites his nails. Sigh. I’m sorry it’s just that the more I think about it, the angrier I get. Wicked Saints came in an OwlCrate box and in the letter from the author to the reader she describes Malachiasz as “a boy whose earnest anxiety hides monstrous secrets.” Except anxiety doesn’t hide what you’re feeling, in fact it often puts your deepest fears on display for other people to see and usually at the worst moment. Anxiety has a million symptoms, many of which can be observed from the outside and thus easily incorporated from the point of view of a non-anxious character. Here’s a list: panic attacks, hyperventilating, shaking, hypervigilance, irritability, restlessness, sweating, tense muscles, difficulty sleeping, and fatigue. Sometimes Malachiasz displays fatigue and irritability, but it’s when the other characters are in the same headspace, so it doesn’t count, because it can easily be chocked up to circumstance, not mental illness.

If we ignore the author’s implication that his anxiety is earnest and assume that he faked it to gain Nadya’s trust, we get to a problem. The book never explores how he lied or parses through where he’s genuine, so, I have to assume that he was supposed to have anxiety. He’s called a monster so many times I got irritated. Aside the fact that it’s offensive to make the only mentally ill character a “monster,” it’s downright annoying to read a million times. Malachiaz is an attempt at a morally gray character. He makes decisions that only benefit himself, but sometimes he saves lives or kisses a girl, so some parts of him are still good. I’m okay with that, what I’m not okay with is piss poor characterization. People with anxiety can be bad! But if you make your villain anxious, it should be for a better reason than he needed a personality.

After I finished this book, I looked through some Good Reads reviews and many of the users pointed out something I hadn’t noticed. To use the blood magic, characters had to cut themselves, and reviewers found they didn’t like how this glorified self-harm. Many suggested that a trigger warning for self-harm should be placed at the beginning or the magic system should have been handled with more sensitivity. As someone who does not have personal experience with self-harm, I won’t elaborate and instead let other people make of it what they will.

There were two parts of the book’s description that sold me on it: one, the girl talks to gods, and two, a star-crossed romance. We already know how disappointed I was about that first plot point, now let’s talk about the other disappointment of the day. A fantastic rule going around on the internet goes “if they have to kiss for you to know they’re in love, it’s not good romance.”

I will say something that may offend many people, but hopefully you’ll stick with me. Young Adult Fantasy books have bad romances. They’re underdeveloped, poorly crafted, and overused. Romance is my favorite genre, and I love seeing it in other types of books, but many times YA fantasies have the worst romances. Despite being constantly undervalued, romance sells and adding it to books usually helps pique people’s interest. But you don’t just “add” it to your book, because romance is hard to write. Hold on, I need that in capital letters. ROMANCE IS HARD TO WRITE. Good romance comes from nuance, established trust, chemistry, and gradual character developments. If a writer doesn’t do those things, you get insta-love, which isn’t satisfying or believable.

Wicked Saints tries to do an enemies-to-lovers trope. Nadya and Malachiasz don’t spend enough time together to develop a proper friendship much less a romance. They have legitimate reasons to hate each other and neither of them seem to change enough for it to be justified that their feelings have evolved. Nadya loses contact with the gods, but that should serve as a crisis of her own faith, not an automatic belief in something else. Her willingness to ignore Malachiasz’s obvious red flags is beyond frustrating and I can’t believe the book wanted me to be surprised that he betrayed the group at the end. Anyway, it’s time to make some conclusions, otherwise this essay/rant will never end.

Part Three: How Did We Get Here?

Wicked Saints is not the first to do these exact mistakes, and it’s here because of its predecessors. What other books do we know that have a Russian culture theme, a useless female narrator, and a love interest who’s bad? That’s right. I’m about to bring up the internet’s infamous Grisha trilogy. Throughout my entire reading experience, I was struck by the similarities of these books to the point where I was sure I was reading a fanfiction AU of Shadow and Bone. These books are so similar it had me wondering about plagiarism (I’m mostly kidding about that). The Grisha trilogy and Wicked Saints use the same tired tropes and rely on the readers need to self-insert to make up for the narrator’s lack of personality.

How do we get books that shout about feminism but don’t incorporate it? Books are written by humans and humans live in a flawed world. Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum and so many of the things we create are flawed. Sometimes, what we meant to write isn’t what is written. An author may have every intention of creating strong, complex female characters, but through the difficulty of writing, poor planning, and a host of other reasons, the result is a bland, useless character. Many times, these characters are touted for having magnificent powers, but they never seem to use them or if they do its only in small ways. This happens, in part, because if the character is all-powerful then there’d be no plot, so to create tension the author takes the power away, scales it back, or adds an obstacle in the way of using said power. This is all well and great, but it often leaves readers feeling like the book duped them into believing this character is special. People don’t like to feel as though they’ve been lied to. In my opinion, “Gotcha” plots and character developments result from bad writing. With Wicked Saints there weren’t “Gotcha” moments so much as there were “please stop being a dumb bitch” moments. Nadya wanted to fall in love Malachiasz and the whole time I kept asking myself why. He’s a saltine with pretty eyes and fucked up nails. Then there’s Serefin who instead of dealing with his problems, he gets drunk. His big plot point is that he doesn’t die and turns into a swarm of moths for a while which would have been cool if they explained it in any kind of manner.

Stopping the proceeding rant, I should make conclusions and end this before it gets more out of hand. YA fantasies aren’t progressing the way they should, and you could point to several books that do incredible things, but they’re in the minority. YA authors need to make their narrators complex and fully formed instead of literal sawdust. We need authors to create better female and non-binary characters who have the same agency as their male counterparts. They should stop including romance in the first book. Let the characters grow and breathe for a hot second. Gradual bonds made through several books are always more satisfying and well-crafted than a rushed romance in book one. Also, people in the publishing industry, please, please, please use sensitivity readers. Or maybe search for books written by Own Voice authors. I know for a fact there are incredible writers creating amazing works out there. I’ve interacted with them. Someone publish their books before my head explodes.

Tag list: @weathershade @queenoffloweryhell @raywritesblog @saistudies @vesaeris-writes

#writeblr#books#book review#wicked saints#rant#long post#essay#ya fiction#ya fantasy#mentions self harm#problems in ya#writing is hard#i'm tired#lit essay#ranting about literature

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

let’s talk about tropes

here’s a little (little?!) post on tropes, as promised!

some tropes i hate and why i hate them

love triangles: this one’s pretty simple and obvious. love triangles are unrealistic and toxic. they romanticize emotional cheating, and they cause nasty ship wars in fandoms, especially when two of the points in the triangle are women. often, the “losing” point of the triangle is a one-dimensional throwaway character who either gets killed off or accepts their fate and steps back for the “winner” to take over. this dynamic can get especially problematic when the “loser” is a woc and the “winner” is white, when the “loser” is an lgbtq+ character, and/or when the “loser” has no purpose other than to create drama for two other fleshed out characters. the character often ends up being hated for bad writing and “getting in the way” of the endgame ship. yikes. the only valid resolution to love triangles, imo, is a polyamorous relationship!!!

girl hate: it’s rare to see nice friendships and romances between women, and often this trope is used to drive an unnecessary wedge between two female characters who would have otherwise been great friends. i don’t mind when two women/girls are in conflict with one another for an interesting reason, but i absolutely hate when the conflict is based on something stereotypical and boring. the “girl hate” conflict is always based on something misogynistic, unrealistic, and/or stupid--like a man, looks, sexual practices, or a contrived competition. this is especially gross when the men in the story act as the voices of reason in the conflict, patronizing the women and teaching them how to be nice and use logic.

“strong female characters”: many writers mistake “strong” characters for characters who employ violence, sassiness, and masculine attributes to get what they want. I’m so over it. all I want is nuanced representation of women that doesn’t reduce them to a love interest or a sex object who looks down on other women. strength comes in many forms, and everyone defines it and identifies with it differently.

miscommunication: this has to be one of the laziest forms of prolonging drama, when two characters are fighting because of something that could easily be solved if they were locked in a room together for five minutes.

incest/incest-adjacent romances: this should go without saying, but we’re for some god-awful reason going through a period where incestuous relationships/fake-outs (ie, you’re in love with him? too bad he’s your brother. oh wait, it’s revealed that he’s not!/you two are blood related but you either never met or you went through a period of separation, so that means you can fall in love) are heavily romanticized or used to create extra drama, and it’s just unnecessary and not cute. i think authors use this to add some sort of edge or uniqueness to their writing, but it’s just so toxic and a complete turn-off for me.

aesthetic oppression: (term inspired by and similar to “aesthetic conflict,” thanks kat) when an author throws in some sort of oppression that is experienced by people in real life, but they either don’t address the oppression thoroughly or they only use it to add some sort of edge to their story and further a character’s romance, death, redemption arc, etc. for example, the homophobia in GOT season 6, which reduced loras to a walking stereotype of a gay man before he was subjugated by the church sept and blown up, and the patriarchy in ACOTAR that only exists to show how feminist rhysand is.

boys/men fighting, having tantrums, or expressing themselves through violence: it’s fine for male characters to fight every once in a while, but i just hate that this seems to be exclusively employed with male characters and it is used as a solution or reaction to problems when realistically, men are much more nuanced. men cry. they might be alone or in front of others. they might cry into their pillow or on a friend’s shoulder. fictional men add violence and anger to their sadness because the authors don’t want to emasculate them, but that’s a stupid goal and crying doesn’t affect someone’s gender. smashing your belongings when you are upset is unhealthy and potentially dangerous, and so is physically fighting others over trivial or patriarchal issues (ie a woman) when conversation could be/is probably much more compelling and effective. it’s important to show men that anger isn’t always the first emotion to feel under duress and that they don’t have to express their feelings by punching walls or throwing their belongings across the room. (also?! practically? YOU’RE RUINING YOUR OWN FUCKING STUFF AND/OR YOUR ROOMMATE/FRIEND/PARTNER’S STUFF, YOU ASSHOLE.)

sexy immortals: immortality can be used in clever and entertaining ways, but i feel like a lot of the immortals i’ve been seeing lately run in the same vein as the twilight vampires, which is to say: unearthly beautiful (aka conventionally attractive), overly sexy (aka stalking a love interest for the sake of “attraction”), apparently 16-25 years old (aka accessible to grown women who read/write ya).

uninvolved parents or non-existent guardian figures: sometimes young characters don’t have parents and that’s fine; some of my favorite books are about characters with one parent or no parents. but i still feel like we’re coming out of a period where it was very popular to kill off the parents (especially moms) at the beginning or before the story starts. i really want to see more exploration of characters with parents, or at least see the characters without parents make significant relationships with adults or react appropriately to the loss of their parents.

one-off character deaths: when a character enters one chapter or episode of a book/show just to immediately die for cheap emotional manipulation. this character is also sooooo often a marginalized person, and it’s super predictable and tired. try harder, author/screenwriter!

some tropes i love and why i love them

special snowflake/chosen one: I can’t explain it. I know it’s so cliche and one of the most hated ones out there, but I love when this trope is done right. I’m not a big fan of the chosen ones who have a special destiny, especially if the mc is a white boy, because that’s been done a million times before. but I’m a sucker for that one character who comes upon an unexpected special ability/object/creature or connection to a force of good/evil/nature and has to contend with that. They’ve been Chosen and they’re completely unprepared, and it’s gonna change their life trajectory and relationships and maybe even political climate.

woobies!!!: I feel like this trope is so underrated and it’s one of my favorites of all time. I absolutely love rooting for that one character who’s too good for any of the shit they’ve been through and Deserves Better^TM, but they manage to survive and grow against all odds.

found family: i love that authors are expanding the concept of family and unconventional narratives about love. the found family trope is so charming and relatable to many readers, and it’s great to see seemingly contrary characters come together to find a loving home together that isn’t necessarily romantic.

soft characters: it’s rare (though increasingly less rare, fortunately) to find soft boys, aka male characters who are compassionate, funny, kind, pensive, and/or quiet instead of brash, loud, violent, and angry. i know so many boys and men who fall all along the spectrum of masculinity, and it would be great to see more characters who represent that, especially because male characters are typically forced to express their masculinity in one way. i also absolutely love seeing women being equally as soft and kind--with the exception of ASOIAF!sansa, i feel like this kind of character has been cast aside for the sassy, rebellious, empowered^TM female character who isn’t like other girls and wields a bunch of weapons. i’d really like to see more female characters whose strengths come from empathy, intelligence, and emotion.

unique relationships within a friend group/ensemble: this one is marginally related to my love of found families. not only do i really like tight, strong friend groups, but i also like when each of the friends within that group has a different and compelling dynamic (hostile, romantic, friendly, tragic, whatever may have you) that can carry a scene or an arc. unique relationships between all the characters in an ensemble adds so much dimensionality to a story.

complex guardian figures: this mostly applies to ya, but i think it can also be said for many adult books and tv shows. adult characters often get flattened or sidelined for romance or action plots when in reality almost everyone has parent/guardian relationships, and these relationships are the source of so much complexity. that complexity may mean love, found family, anger, patronization, manipulation, and more, and all these things will be expressed differently based on the characters in question. for example, look at the difference between eleven and hopper from stranger things and harry and dumbledore from harry potter. hopper and dumbledore are so different and each of them carry darkness and baggage that comes out on the kids for better and worse. bonus points if the guardian is a woman, because these types of relationships between girls and women are relatively rare to the ones between boys and men.

anti-heroes/anti-villains: i think this is another one that goes without explaining. we’re all the hero of our own story, after all. if an author can successfully convince me to root for a character who i know is wrong but believes they’re in the right, or for a character who does the wrong things for the right reasons, there’s a good chance that i think very highly of that author.

stoic, bitter, angry characters: if there’s one character in the ensemble who has any of these traits, there’s a good chance they’ll be my favorite, especially if that character is a woman. usually this character’s journey is about what makes them vulnerable and how they become close with the most unlikely companions or form a special relationship with a foil character. it makes the audience feel like we’re being let in on a secret, specifically about that character.

and that’s about it! my inbox is always open to talk more in depth about any of these and more, so let me know. thanks so much for 700, you all are great :D

283 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are some under used marvel female characters youd love to see in the rpc?

HMMMOkay, so I’m trying to think OBJECTIVELY here and not just rattle off the female characters that I personally like, and more “I’m surprised that there’s not more blogs for this character, whether or not I personally am a fan” ....because I missed the “you’d love to see in the RPC” bit because I’m dumb, and then I wrote this whole list without regards for that part. So this came out as less “female characters I personally want” (who would all be stupidly obscure and irrelevant anyway) and more “female characters I think the RPC should give some more love to, whether I personally am into them or not”:Definitely ALL the girls in the New Mutants and Generation X! I see a fair few blogs for Magik and Jubilee, but I really don’t see any for the others. I get why Magik is going to be more popular---she’s in more stuff, she’s currently much more relevant in the comics, and her backstory is so goddamn compelling---but that doesn’t mean the others shouldn’t have ANY blogs out there. Wolfsbane, Magma, Karma, and Moonstar are all extremely complex and compelling characters with their own struggles and triumphs too, and I think they deserve just as much love. Likewise, I get why Jubilee will naturally get more blogs than Husk, Monet, and Penance (depending if you count Penny as a separate character or not...) due to her being in more stuff, having bigger arcs, etc. But it still surprises there’s NO blogs around for those ladies! I know there was that Monet blog awhile ago, and @badmusesdoitwell had an Amara that’s now part of their multimuse, as well as a Rahne, but that’s still nowhere near enough love in the RPC for these Junior X-Ladies, in my opinion. Speaking of Generation X, I’m also a bit surprised no one has picked Cordelia Frost up, given that we’ve got plenty of background canon for her via Emma’s history yet Cordelia herself has LOTS of room to go nuts with headcanons, like it’s just the perfect opportunity! And I’m sure lots of Emma blogs, of which there are MANY, would love their little sister around for some family threads. Fuck, I would pick her up myself if I were more into Emma and the Frost family as a whole. She’s hardly the most relevant, recent, or even interesting character around, she’s done very little and shown up very briefly, but the fact she’s related to Emma Frost makes me think SOMEONE would have an interest in her.Madelyne Pryor, for sure. Like, I love Maddy, but it’s not just my favoritism talking here. I think she’s pretty decently well-known in the comics fandom, and she’s a tragic villain, which usually pulls people in big-time. She’s got a grudge against the good guys, and it’s actually more legitimate than most, which I’d think would also attract people, since a lot of villains fans like to blame the good guys no matter what and THEY’D ACTUALLY HAVE A GOOD ARGUMENT HERE? Plus she has very strong connections to other, more popular canons, with a ton of fodder for angst and drama threads, which people just LOVE. I have seen a few Maddy blogs pop up in the past, and I always get so excited, but they never seem to last very long :CDr. Moira MacTaggert deserves ALL the love and respect in the world/fandom! She’s been a staunch supporter of mutants since day one, she’s a total badass, she’s super smart, she calls Xavier out on his shit ALL THE TIME, she’s the survivor of an abusive husband, she had to make terrible choices about her son that no mother should ever have to and then live with the consequences of those choices, and SHE GOES AFTER A KELPIE WITH A GODDAMN MACHINE GUN! She’s been a part of the X-Men comics for such a long time, and is very significant in them, it really surprises me that I’ve never seen a blog for her besides just ONE and it was for the XMCU sexy American CIA agent Moira, who is NOT Moira in my book and NEVER WILL BE. Speaking of, Moira will ALWAYS be human to me, I think making her a mutant all along REALLY undermines a big part of her character as just an unyielding mutant ally. Though I think her being human, combined with being an older female who isn’t anyone’s love interest (unless she’s, gasp, getting in the way of CHERIK aka the ultimate fandom sin how dare she the harlot -.-), is probably WHY she’s so damn ignored -.-Frenzy hasn’t been in THE most recent stuff, but she’s still been relevant recent enough that I think one or two blogs around would have happened if she weren’t black. Yeah, I hate to be THIS person, but any black character who isn’t Storm doesn’t get love, for all that the RPC likes to yell about being diverse and progressive. Remember all the Captain America and Iron Man and Hulk and Quicksilver blogs that popped up after their movies? Yeah I saw like ONE T’challa blog after Black Panther came out. Then again, I’ve yet to see blogs for Pixie or Firestar either, who are white, and I feel like they both were fairly interesting and well-known in fandom? Same for the Academy X girls like Sofia Mantega, Mercury, and Wallflower. Luna Maximoff FOR SURE. It SHOCKS me I haven’t see more than a couple short-lived blogs around for her, just given her family connections. Now, I don’t think a character deserves love just because of who they’re related to---in fact it annoys me when a characters gets a ton of attention and it’s very obviously just for that---but Luna has SO MUCH going on? The problems between her parents, her mother being absent so much, her father exposing her to the Mists, dealing with her powers, being a child of two very different worlds and cultures, it just goes on and on. Luna has had to grow up so fast, she’s such a strange and stoic child as a result, and though her situation is very fantastical, having to be the mature one at an early age because all the adults in your life won’t be is something a lot of people have to cope with and I think would find relatable; I especially love how she lives in this world where there’s no bad guys, like neither Crystal nor Pietro were the villains in her situation, just hurting messed up people, which she also recognized in Magneto and maybe also even Maximus . And there’s so much that could be explored with her too that hasn’t been in canon yet---for instance, her choice to identify with her Inhuman heritage and why that is, and the journey of identifying with your heritage but also looking at the horrible things in their history, I think that’s a story that a LOT of people from MANY backgrounds can relate to. It surprises and frustrates me that both writers and fandom don’t really seem to care about her or remember she exists; one the only two blogs I ever saw for her seriously got someone asking them “why would you make such a weird OC” like SERIOUSLY! Luna needs more love, big time. Any female Avenger that’s not Wanda or Natasha. I don’t read Avengers, I’m just an X-Men fan, but I know they exist and they shouldn’t have to be in a movie to get love. Ditto for She-Hulk, I’m not a Hulk reader but I know she’s a prominent character who has been around a long time and has a very developed personality and stories of her own, yet I’ve only ever seen her on @getreadytosmash‘s multi. I’ve also never really read Alpha Flight, but its main ladies ---Snowbird, Aurora, Vindicator---all seem awesome in their own different ways. Alpha Flight isn’t very popular to begin with, of course, so I don’t expect them to have as many blogs as, say, major X-ladies, but I think one apiece or so would be very justified.KWANNON!! I actually get why we didn’t have any blogs for her BEFORE now, because we knew NOTHING about her, she was just a very tragic prop for Betsty’s body-swap plot and a way to give her insta-ninja-skills, but now she’s come back and has HER OWN NEW SERIES in which we’re finally learning who she is and her background, I hope to see a blog or two around for her eventually!Destiny aka Irene Adler. Like. Do I even need to explain WHY? I think people just don’t want to play an OLD woman, especially one whose primary/only ship is going to be with another woman.Maaaaybe Clea Strange? I don’t know shit about her, never read Dr. Strange, but like, people make blogs for Sigyn literally just because she’s Loki’s wife, and Clea at least seems to like...DO stuff? IDK, not sure on this on, but figured I’d make an honorable mention.Siryn, Boom Boom, and Dr. Cecilia Reyes are all X-Ladies that I really don’t know much about. Like I know basic things like their powers but I don’t know their story arcs and such. But as with Clea and the Avengers ladies and She-Hulk, I just have a HUNCH there’s a lot there getting ignored by fans.Silhouette Chord is a longtime member of The New Warriors, and, like Alpha Flight, New Warriors doesn’t really have a fanbase on Tumblr to speak of, so it’s not surprising to me she’s not got any love here. And even within the pages of her own comics, she’s generally pushed aside, underused, and underdeveloped compared to the other characters, generally more a prop for her boyfriend’s stories than anything else. But she DOES have a personality, a REALLY cool backstory, and she’s like...look, the RPC claims to love diversity and representation and all that, right? Silhouette is a mixed-race WOC (half Black, half Cambodian, and I have NEVER seen another Marvel character of Cambodian heritage who wasn’t connected to her) who is also very visibly physically disabled, her legs are completely paralyzed and she is never without her braces/crutches, yet she still fights PHYSICALLY (something very rare for physically disabled characters, they usually are more like Oracle or Prof X) and is depicted in a sexual relationship, and there’s never any kind of fuss or angst about it or anything treating her as delicate or less than or anything like that. She’s just completely adjusted to it in a way that’s very rare in media. And like I said, she’s not a flat character, I’m not saying she should be more popular just for ticking off the diversity boxes, she manages to be really intriguing to me despite how little focus the writers give her, and I think that she and the other New Warrior girls (Firestar and Namorita) have a lot to offer the RPC. But I have to give a special shoutout to Sil since she’s my fave, as the neglected ones alway are.Meggan Puceanu is probably most familiar to folks here as Kurt’s love interest in Age of X, but she’s been around since the 80s. She’s a longtime member of Excalibur, and she’s just...fascinating. She’s a Romanichal mutant (though often hinted to have magical/mystical heritage too, perhaps fairy like Pixie) who has empathic, elemental, and shapeshifting capabilities. However, her empathic and shapeshifting tend to overlap, so she changes her form (and her mind) according to the feelings, fears, and desires of others. So for instance, there’s this one time where a group of men are checking her out, and she feels that “They love me...I want...to love them in return!” and she morphs into this sexxed-up version of hersef on the spot. This isn’t played for kinkiness or laughs either; Meggan’s identity struggles are a HUGE part of her character. She has no idea who she is because her powers make her reflect and respond to the feelings of others around her, internally and externally. She doesn’t even know what she actually really LOOKS like because of this; her powers were present since birth, causing her to grow fur instantly as an infant due to it being winter. This caused her parents to keep her locked up in the camper trailer, where she was raised alone with the TV (she’s also illiterate, which causes her to feel dumb a lot) and as more and more people around her spread rumors about the monstrous child inside, she psychically absorbed those beliefs and her physical form changed to reflect them, making her more and more monstrous as she got older. She didn’t know she was a shapeshifter, she just really thought she was a hideous monster. And even when she found out the truth, she STILL didn’t know what she really looked like, as the beautiful form she took on (basically Pamela Anderson with elf ears) was to please her boyfriend Captain Britain (whom she is really unhealthily dependent on starting out because of her situation)Meggan is insecure, she doesn’t know who she is, she has to cling to a man in order to have anything because no one else has ever loved her, she easily becomes jealous of other women near him, she gets made fun of for being a bimbo and she often feels she is because she can’t read or understand “clever words” due to her isolated upbringing...and she gets through this! She develops! She becomes STRONGER and she becomes SECURE and she gains CONTROL of her powers and SHE KICKS ASS and she FORMS AN IDENTITY! And then Meggan SACRIFICED HER LIFE to buy time for Captain Britain, Psylocke, and Rachel Summers to repair the tear in reality caused by House of M. She ends up lost between dimensions and TRAPPED IN HELL, where she uses her empathy to rally the lesser demons against THE LORDS OF HELL ITSELF and wages a war IN HELL for which her demon followers dub her “Gloriana” and she forms a sanctuary there called “Elysium” where souls can escape torment! AND THEN SHE FINDS HER WAY HOME!THIS WOMAN KICKED ASS IN HELL AND WON!! Like she just goes through SUCH an arc, and I admit I have not read it myself yet, she’s on my list of characters to read EVERYTHING on and I’m still only familiar with her very insecure Excalibur days (which I love a lot, I just feel so much for Meggan and her struggles, I think she’s very much a reflection of a LOT of real-world issues, ranging from mental illnesses to just EXISTING as a woman) but I already have a ton of feelings about her and I think she’s more than prominent and accomplished enough to merit more attention in the RPC. And this is less of an “actually has reasons the RPC should love her” character, because really there’s no reason they should, she’s not prominent or relevant or or anything, but more an interesting “did you know”---did you know there was a “young female Wolverine clone” in the comics BEFORE Laura Kinney? Avery Connor! She pre-dates Laura by a year and has a VERY similar story, yet she never took off in popularity and very few people know her. You can read about her HERE on my Marvel blog. Again, would not say there’s actually any reason she’s earned love from the RPC like, say, Meggan or Luna, but I just thought I’d toss that in as a tidbit for the Logan family fans, as I know there are many.(Also, cheating because these are dudes, but: I’m not a Banshee fan but I am surprised I’ve never seen a blog for him, nor for Sunfire. Or for 616 Pyro. Or...)

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Well Cairn, going off established precedent, you have to start by slowly accruing some highly symbolic gemstone prosthetics. Just pretend that this is part seven of jojo and start competing with Phos to see who can obtain the most religiously significant body parts. Whoever has the most by the time the seventh meteor hits wins!

So about this chapter…

The part of this chapter that really merits discussion is one I kind of have trouble parsing—so much so I ended up rewriting this essay a couple times. Neither Cairngorm nor Aechmea are very forthright characters, which means you have to chase after subtext in order to guess at what’s really being communicated, and this chapter seems to really lean into that approach to dialogue. Which is to say, I’m kind of unsure of my interpretation of this chapter. But if I just throw in the towel now out of fear of misinterpreting my favorite problematic rock, then Ichikawa wins, and I can’t let her and her vaguely menacing self-portrait get the better of me.

At the start of the second half of the chapter, Cairn seems quite content, but the longer the (rather one-sided) conversation goes on, the more distressed they become. While it’s not made explicit what’s upsetting them, my take is that Aechmea’s attitude in this scene makes it harder for Cairngorm to manage their cognitive dissonance toward him. I’ve mentioned several times before that a number of things Cairngorm says and does indicate that they realize that Aechmea is shady and perhaps not operating in their best interest, but they don’t want to admit that to themselves. As long as Aechmea remains ambiguous, they can pretend that everything’s fine. I think that Cairn’s steadily increasing dismay over the course of the chapter is because pretty much everything Aechmea says here threatens to clarify those ambiguities, and said ambiguities resolve themselves in a way that Cairn isn’t terribly pleased with. Let’s take it from the top.

First, let’s address the initial stretch of the conversation. Aechmea implies that he doesn’t actually see any value in the gender roles he’s been encouraging Cairn to adopt, seeing them instead as simplistic tools to keep the other Lunarians occupied—mere bread and circuses. But while Cairn may not understand the implications of said gender roles, the fact that they made Cairn feel special and loved was enough to make them invested in the whole concept. So, for Aechmea to imply that it was all an act designed to provide fleeting, cheap entertainment for the other Lunarians probably feels like a slap in the face to Cairn.

In the same breath, he gently tells Cairn that he plans on isolating them in a compound on the most remote of the six moons, and that that’s his idea of granting Cairn freedom. This makes it completely clear that what Cairn said to him in chapter 71 went in one ear and out the other: Cairn wants to finally have agency and can’t abide doing nothing while everyone else is struggling, and Aechmea responds by making a drastic decision about their life without their input, one which will cut them off from the conflict they want to help resolve. As one might expect, Cairn doesn’t seem happy to hear this.

This next section of the conversation in which Aechmea tells them he’s loved them before they came to the moon also follows the pattern of being full of understated subtext that I apparently require two weeks to untangle and draw a conclusion from. It’s seems clear from their distraught expression, trembling, and the fact that they incredulously bring it up again a few minutes later that what Aechmea is saying upsets them. If I had to wager a guess, it’s because the implications are concerning regardless of whether or not Aechmea’s words are true. His claim is ludicrous and Cairn doesn’t want to believe that he’d try to feed them a bald-faced lie, but if he’s not lying then the implications are equally unsettling. I think Cairngorm is most comfortable believing that their meeting with Aechmea was a happy accident, because the alternative is that he was romancing them all while hiding ulterior motives. (Not that it really needs to be reiterated at this point, but these pages make my skin crawl, especially when you look back on Phos’s first day on the moon—with Aechmea trying to butter them up by them by telling them how special they are.)

Anyway, let’s assume for the sake of argument that Aechmea’s statement wasn’t complete bullshit, and that he had some sort of interest in Cairngorm before meeting them. The fact that he kept their old arm indicates that there’s something to what he said, as does the fact that he feels the need to distract Cairn with creepy makeouts when they try and press him for answers on this topic a few pages later. There are a couple of ways I could see it going, so I’m going to go on a tangent for a minute, and try to speculate on what might have piqued Aechmea’s interest in Cairn. I don’t feel that predicting future plot-events is really my forte, but sometimes I can’t resist trying to decipher a good puzzle.