#jacquetta of luxembourg

Text

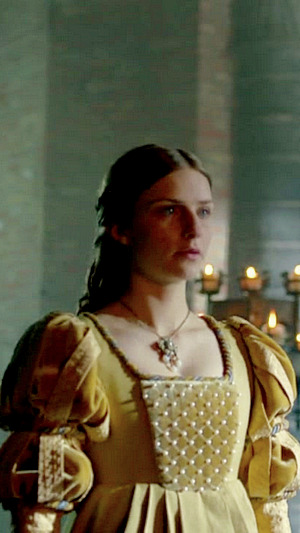

The White Queen 1.01: In Love with the King + Hair Moments

#The White Queen#TheWhiteQueenEdit#Elizabeth Woodville#Jacquetta of Luxembourg#Jacquetta Woodville#weloveperioddrama#perioddramaedit#period drama#historical drama#In Love with the King#costumeedit#costumes#costume drama#Awkward-Sultana

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WHITE QUEEN 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY WEEK | Day 3 (August 16): Most Underrated Character → Jacquetta of Luxembourg

If a witch is capable of the darkest and most evil deeds. If a witch will do anything to see their own needs met, regardless of the pain and suffering that they cause others. Then, indeed, there is a witch in this room, Lord Warwick. But it is not me.

#the white queen#twqedit#perioddramaedit#twq10#Jacquetta of Luxembourg#jacquetta woodville#Janet McTeer#S1E03 The Storm#S`1E01 In Love With The King#S1E02 The Price of Power#S1E04 The Bad Queen#S1E06 Love and Marriage#my edits

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WHITE QUEEN 10-YEAR ANNIVERSARY WEEK

Day Six - Favourite Family Dynamic: Elizabeth Woodville and Jacquetta of Luxembourg

#the white queen#twq10#twqedit#elizabeth woodville#jacquetta of luxembourg#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#weloveperioddrama#perioddramagif#femalegifsource#adaptationsdaily#cinematv#filmtvcentral#smallscreensource#femalecharacters#rebecca ferguson#janet mcteer#my edit

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick

&

Jacquetta of Luxembourg

#the wars of the roses#15th century#medieval#middle ages#british history#medieval fashion#historical#character design#digital art#artists on tumblr#my art#edward iv#elizabeth woodville#elizabeth of york#jacquetta of luxembourg#richard neville#isabel neville#henry vi#richard iii#the white queen#the white princess#plantagenets#royals

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

❁ THE WHITE QUEEN 10-YEAR ANNIVERSARY WEEK ❁

Day Seven - Free Day >> Favourite Costumes, designed by Nic Ede

#the white queen#twqedit#perioddramaedit#twq10#janet mcteer#veerle baetens#rebecca ferguson#faye marsay#eleanor tomlinson#amanda hale#freya mavor#my edits#jacquetta of luxembourg#margaret of anjou#elizabeth woodville#anne neville#isabelle neville#margaret beaufort#elizabeth of york

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

the white queen 10 year anniversary: most underrated characters -

[ J A C Q U E T T A • O F • L U X E M B O U R G | M A R G A R E T • B E A U F O R T | I S A B E L • N E V I L L E | C E C I L Y • O F • Y O R K ]

dowager duchess of bedford | countess rivers | mother of a queen | not a witch • mother to a king | duchess of suffolk | countess of richmond | lady stafford | countess of derby | my lady, the king's mother | patient | pious | venerable | survivor | the red queen • kingmaker's daughter | duchess of clarence | house of york | the forgotten sister | lady warwick • viscountes welles | daughter to a queen | sister to a queen | lady kyme |

#jacquetta of luxembourg#margaret beaufort#isabel neville#cecily of york#amanda hale#eleanor tomlinson#elinor crawley#the white queen#thewhitequeenedit#historicalwomendaily#historical women#wars of the roses#usergaby#the white queen 10 year anniversary#twq10#twqedit#myedit*#mine*

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

How is the relationship between Margaret of Anjou and Jacqueta of Luxembourg? (Jacquetta was one of the three people who convinced her not to enter London, which made me fantasize about their relationship.)

We simply don't know a lot about their relationship. Jacquetta does seem to be prominent at court during Margaret's time as queen consort but we don't know if this indicates - or led to - any personal closeness between the women. We know the Woodvilles had a close affiliation with the House of Lancaster and Jacquetta was the widow of Henry VI's uncle, John, Duke of Bedford and the dowager Duchess of Bedford so that may well have been the reason for her prominence. Jacquetta could also claim a familial connection with Margaret herself: her sister, Isabel, had married Margaret's uncle, Charles of Anjou, Count of Maine. The idea that Jacquetta and Margaret were especially close seems to have been popularised by Philippa Gregory in her novel, The Lady of the Rivers, and her biography of Jacquetta in The Women of the Cousins' War but historians are more cautious.

Jacquetta and her husband were part of Margaret's escort to England in 1445. According to B. M. Cron, Jacquetta attended Margaret's coronation banquet and was seated on Margaret's right - this is far more likely to be due to her being the first lady in the land after Margaret than an indication of their closeness; Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester was seated on Margaret's left and the idea of Gloucester being a close friend of Margaret is not credible. Cron also claims that Richard Woodville was Margaret's champion in the jousting festivities that followed. Lynda J. Pidgeon claims it is "significant" that Richard Woodville was not created a baron until after Henry VI's marriage to Margaret, but credits it more to Henry's desire to "create a royal family around him" than to any relationship between Margaret and her escort.

Jacquetta's servants were regularly given gifts by Margaret in the New Years celebrations. In 1446, her servants received 53s. 4d. and in 1447, 1449 and 1452, Jacquetta's servants received 66s. 8d. This is on a par with other gifts to ducal servants - in 1446, this was the same amount given to the servants of the Duke of York and Duchesses of Buckingham and Exeter, while in 1447, the same amount was given to the servants of the Duke of Gloucester, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Duchess of Buckingham. Jacquetta herself was only given gifts by Margaret in 1447 and 1452 according to Pidgeon but I'm not sure what the source is for that and neither Helen Maurer nor A. R. Myers mention it when discussing Margaret's accounts. Not all of Margaret's accounts survive so we don't have the full picture.

Jacquetta attended Margaret's churching after the birth of Edward of Lancaster in 1453. Jacquetta and her husband were part of Margaret's court during her extended stay in the midlands beginning in 1456, though, according to Pidgeon, they are only rarely mentioned as being present. This is may have been due to the frequency of Jacquetta's pregnancies keeping her away from court.

And yes, Jacquetta was one of three women (the others being Lady Scales and Anne, the dowager Duchess of Buckingham) who accompanied a delegation of London aldermen who convinced Margaret to send her army away. As Helen Maurer says:

Both Jacquetta, the dowager duchess of Bedford, and Ismania, Lady Scales, had been among the women who had escorted Margaret from France, and Lady Scales had remained in her household as a personal attendant. All three ladies had been recipients of New Year's gifts at various times, and Anne, duchess of Buckingham had stood godmother to Prince Edward. Though the personal relationships that existed between Margaret and these women are difficult to assess, it is apparent that the mayor and aldermen believed that they would be received with trust and favor.

Jacquetta's prominence at the Lancastrian court may explain the tradition that her daughter, Elizabeth Woodville, was a lady-in-waiting to Margaret. There is, however, no evidence of that Elizabeth served Margaret and historians have generally poured doubt on the idea. One exception is Susan Higginbotham who suggested that it is still possible that Elizabeth was one of Margaret's damsels, saying if that Elizabeth did serve Margaret , it's "more likely that she did so in the late 1450s, a period for which Margaret's household records do not survive".

There is no evidence to tell us what Margaret thought of the marriage of Elizabeth Woodville and Edward IV or the Woodvilles' defection to the House of York. There is no evidence Jacquetta and Elizabeth feared Margaret especially during the Readeption - it would be very, very surprising if they feared her more than Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (after all, it was in Warwick's attempt to depose Edward IV in favour of George, Duke of Clarence that had seen Jacquetta's husband and son executed, presumably without trial).

Nor do we know if, in the aftermath of the Lancastrian defeat at the Battle of Tewkesbury and Margaret's capture by Yorkist forces, whether Jacquetta met with or attempted to advocate for Margaret before her own death in 1472. We do not know if anyone advocated for Margaret's imprisonment to made more bearable, who decided her jailer would be Alice Chaucer, dowager Duchess of Suffolk and an old friend. If anyone did, I suspect it would be Jacquetta or Elizabeth Woodville (possibly in memory of her mother's friendship). It is tempting to speculate that Margaret's entry into the London Skinners’ Fraternity of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in c. 1475 came about due to Elizabeth's influence (Elizabeth had entered the fraternity in c. 1472) but there's simply no evidence of it. It makes for a nice story, though.

In contrast to Maurer, Pidgeon is fairly doubtful of the idea that Jacquetta and Margaret were friendly, citing first the lack of mention of their attendance on Margaret and the lack of New Year's years gifts given to Jacquetta, saying:

Margaret’s apparent lack of friendship for Jacquetta might also be explained by Jacquetta’s Burgundian connections. Jacquetta’s father had been responsible for the capture of Margaret’s father at the Battle of Bulgnéville in 1431, following which René had been held prisoner by the Duke of Burgundy for some years until his ransom was paid. Margaret was also concerned to promote French interests to Henry and any reminder of a previous Burgundian policy might have been frowned upon. It was widely believed that it was through Margaret’s prompting that Henry had agreed to surrender Maine to René of Anjou in 1445.

However, Pidgeon bases some of this on the claim that Margaret "probably detested" the English, which we don't know and seems to be drawn from Yorkist and Tudor stereotypes of Margaret. As for the claim that Margaret pushed for Henry VI to surrender Maine to her father, it is true that she was blamed for it but what role, if any, she actually played is unknown. It is more likely that the surrender of both Maine and Anjou was an unofficial promise made by the English delegation in the negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Tours (1444). Given Margaret was a 14-year-old girl at the time, it is incredibly unlikely she was responsible for that promise. She was urged to intercede with Henry to ensure the fulfilment of that promise but we simply don't know if she did or even what she thought about it. As I say here, she was still in her teens when the handover occurred and we must be wary of the misogyny embedded in the narrative that a teenage girl was responsible for the actions of an adult man - who, after all, was surrounded by experienced and mature advisors.

In short, the answer is that we don't know what the relationship between Margaret and Jacquetta was like. We see Jacquetta given favour in keeping with her status as a duchess and in keeping with her family connections to both Margaret and Henry. If any special relationship grew up between Jacquetta and Margaret, if they became close friends, there is little evidence to show it.

The Woodvilles were loyal to the Lancastrians throughout the resumption of the Hundred Years War until the Lancastrian defeat at the Battle of Towton. How much of that can be credited to the Woodvilles' traditional loyalties or Jacquetta's personal ties to Henry VI (who, after all, was her nephew by marriage) versus a (hypothetical) close relationship between Margaret and Jacquetta is unknown.

Philippa Gregory made much of this limited evidence, while Maurer more cautiously suggests that Margaret looked on Jacquetta as someone she could trust. Pidgeon, on the other hand, argues that there was no friendship between the women. I have my suspicions about why Pidgeon argues that (I haven't read her whole book so I can't say for sure).

Personally, I've tended to imagine a connection that dimmed over time due to diverging lives - Jacquetta's frequent pregnancies kept her away from court, Margaret's life became absorbed by the political struggles of the Lancastrian court. The simple fact is that we don't know - there isn't anywhere enough evidence to judge - and you're free to imagine what you like.

Sources

B. M. Cron, Margaret of Anjou and the Men Around Her (History and Heritage Publishing 2021)

Philippa Gregory, David Baldwin and Michael Jones, The Women of the Cousins' War: The Duchess, the Queen, and the King's Mother (Atria Books 2011)

Susan Higginbotham, The Woodvilles (The History Press 2013)

Helen Maurer, Margaret of Anjou: Queenship and Power in Late Medieval England (Boydell Press 2003)

A. R. Myers, "The Jewels of Queen Margaret of Anjou", Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, vol. 42, no. 1 (1959)

Lynda J. Pigdeon, Brought Up Of Nought: A History of the Woodville Family (Fonthill 2019)

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

After reading your article, marriages like Eleanor and Humphrey, Katherine and John, Henry VIII and Ambeline are described as women seducing men, and men being victims... But marriages like Owen Tudor and Catherine, Richard Woodville and Jacqueta in Luxembourg, will have completely ignored the subjective initiative of women, and the description of men seducing women should be class/gender discrimination?

Hi anon, I think you're asking about what kind of narratives there were around the marriages between men and women of significantly higher status, the inverse of the type of relationships I was talking about in this blogpost I made on my sideblog that focused on Eleanor Cobham, where women married men of much higher status than themselves.

There seems to be comparatively little scholarship in this area and it would be fascinating to see what commonalities and links a study would produce. The marriage of men to women of significantly higher status than themselves does appear to have been fairly common but does not seem to have generated the same amount of commentary and infamy as the relationships between women who married men of significantly higher status. I don't mean that they didn't contract comment but that there was little sustained comment - who remembers Alice de Lacey and Eubulus le Strange? Katherine Woodville and Sir Richard Wingfield? The only high profile case I can think of is Joan of Kent and Thomas Holland.

From what I could find, there does not seem to be the equivalent narrative of the man of lesser status seducing or bewitching the high-status woman into marriage. Instead, what seems to be the common theme is, as Katherine J. Lewis says, "a standard medieval antifeminist notion: that women were naturally inclined to lust and rendered irrational to it."

Lewis was talking specifically about the case of Catherine de Valois. One contemporary chronicler remarked that she was "unable to fully control her fleshly passions" when she married Owen Tudor and even chastises her for keeping the marriage secret "so she did not claim honourable title [of marriage] during her lifetime". Tudor was described by another chronicle as "no man of birthe nother of lyflode", implying his unworthiness. But there seems to have been little rancour or blame directed at Tudor.

It's not until the 16th century where the image of Catherine as governed by her lust became the dominant narrative around her remarriage, perhaps because the rise of the Tudor dynasty and Henry VIII's marital life lent itself to it. One notable example is Edward Hall, who in 1548 described Catherine as:

beyng young and lust, folowyng more awne appetite, then frendely counsaill and regardyng more her priuate affecion then her open honour

He describes Tudor, on the other hand, as a "goodly gentilman & a beautyful person, garnished with many Godly gyftes, both of nature & of grace" - so the issue here is not that Tudor is a social-climber but that Catherine is at the mercy of her sexual desires. Probably the most extreme example of this is Nicholas Fox's claim that Catherine "bey[ed] like a very dronkyn whore" in bed with Tudor - a factoid often gleefully repeated by historians and commentators to proclaim Tudor's sexual prowess despite the fact that Fox made the claim in 1541 and is far from a reliable source. The fact that it has been almost universally used to celebrate Tudor by demeaning Catherine shows how long-lasting this type of narrative is. Polydore Vergil similarly describes Catherine dismissively as "yonge in yeres, and thereby of lesse discretion to judge what was decent for estates" and then focuses on Tudor's lineage and good qualities. Kavita Mudan Finn notes that he "succeeds in suppressing what on the surface to appears to be her agency - a second marriage of her own free will - by literally changing the subject to Owen, and by extension, Henry, Tudor". This same suppression of Catherine's agency appears again in Michael Drayton's Englands Heroicall Epistles where Catherine appears to be acting on her own initiative, wanting Tudor for herself, but Drayton has Tudor displace Catherine's agency by citing destiny as the impulse behind their union. Catherine "is reimagined as a 'a Royall Prize' for Tudor to claim", per Finn. In short, Catherine appears to be cast as oversexed and/or uncontrollable while Tudor's individual qualities and descent are celebrated and their union is seen as governed by destiny and fate.

Joan of Kent has fared similarly to Catherine in that she is primarily remembered as governed by her lust. Famously described as Froissart as "a woman more beautiful and amorous than any in the realm" and by Adam of Usk as a "woman given to slippery ways", Joan had married Thomas Holland clandestinely, then been convinced by her family to marry William Montagu (the son of the Earl of Salisbury). Around eight years later, Holland then petitioned the papacy to return Joan to him, resulting in a public scandal. When Holland died in 1360, Joan made another shocking match, this time marrying Edward of Woodstock, Edward III's eldest son and heir known to history as "the Black Prince". Joan was sometimes referred to the "Fair Maid of Kent" or "the Virgin of Kent", probably sarcastically. Thomas Austin's wife was alleged to claim that Joan's son with the Prince, Richard II, was "nevere the prynses son and ... his moder [i.e. Joan] was nevere but a strong hore". Froissart recorded a conversation between Richard and his usurper, Henry IV, where Henry alleged that a bastard gotten in adultery. W. Mark Ormrod also suggested that various narratives about Joan in the Peasants Revolt built on her carnal reputation and may have reflected even more salacious tales floating around. Thomas Walsingham emphasises Joan's other alleged, inordinate appetites around the time of her death - gluttony ("hardly able to move about because she was so fat") and a love of luxury.

It is, however, very difficult to determine how much of Joan's reputation was shaped to her marriage to a man of significantly lower status or how much it was shaped by her marriage to the man, at the time, was to be the next king of England and to whom her marriage was both scandalous and unconventional. Likely, her reputation was formed by both marriages, both feeding the other. The deposition of her son also meant that her reputation was used as a way of slandering him. Thomas Holland, on the other hand, barely seems to be mentioned, let alone criticised - even if he was in his mid-20s when he married the 12 year old Joan. In fact, Henry Knighton's chronicle positions Holland as seduced by her, crediting Holland's "desire for her" as the cause that she had been divorced from her second husband, Montagu.

Jacquetta and Richard Woodville do not seem to have drawn the same level of commentary. Lynda J. Pidgeon notes that "the marriage ... aroused no comment from English chroniclers until after the couple’s daughter, Elizabeth, married King Edward IV in 1464". though it was recorded in by continental chronicles, such as Enguerrand de Monstrelet, who recorded recorded:

In this year [1436], the duchess of Bedford, sister to the count de St. Pol, married, from inclination, an English knight called sir Richard Woodville, a young man, very handsome and well made, but, in regard to birth, inferior to her first husband, the regent, and to herself…

This has similar echoes to Hall's and Vergil's comments about the marriage of Catherine and Owen Tudor - Jacquetta marries from "inclination" a man inferior to herself but who is otherwise "very handsome and well-made". Hall includes the story of their marriage immediately after his account of Catherine and Tudor, which, as Finn says, "hints at a growing interest - and indeed, anxiety - about women's desires". Like Catherine, Jacquetta is described as marrying Woodville "rather for pleasure then for honour" and "without coū∣sayl of her frendes". Her family is said to disapprove but can do nothing - sentiments also found in Monstrelat and Jean de Wavrin. Rather than dwelling on Woodville's qualities as he does with Tudor's, Hall describes Woodville "lusty" and notes that he was made Baron Rivers, which may indicate . He does, however, mention the marriage of their daughter, Elizabeth, to the future Edward IV, a subject which he promises to return to.

The continuation of Monstrelet's chronicle links Jacquetta and Woodville's marriage to that of their daughter, Elizabeth Woodville's marriage to Edward IV, "thus linking these two unorthodox women together", per Finn. Here's what this continuation says:

After the death of the duke, his widow following her own inclinations, which were contrary to the wishes of her family, particularly to those of her uncle, the cardinal of Rouen, married the said lord Rivers, reputed the handsomest man that could be seen, who shortly after carried her to England, and never after could return to France for fear of the relatives of this lady.

It is likely that Jacquetta's unconventional second marriage helped render Jacquetta's reputation suspect and tempting to speculate that that it rendered her vulnerable to the accusations that she had used witchcraft to make Edward IV marry her daughter, Elizabeth Woodville. The unpopularity in France and Burgundy of her first marriage to John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford and Regent of France may have also played into this view. Ricardians have certainly framed her as her as a seductress and her family as scheming, power-hungry social climbers in that regard - while also treating her as driven by her lust for Woodville. However, there is no evidence that this was the view of Jacquetta at the time, either in England or in France.

Richard Woodville is unique amongst the three men I've mentioned in that he seems to have been reviled as a man "brought up from nought", along with the rest of his and Jacquetta's prodigious offspring. This view has been spurred on by Ricardian historians that have reviled Elizabeth Woodville, where the entire family is depicted as a brood of grasping social climbers. An invasive species, if you will. I think it is likely that Jacquetta and Richard Woodville's marriage has helped furnish this view, particularly for Woodville himself. However, this particular image of Woodville and his children only seems to emerge with Elizabeth's marriage to Edward IV and the tensions between Edward, Woodville, George, Duke of Clarence and Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick ('the Kingmaker'), rather than Woodville's marriage to Jacquetta.

In short: the tendency seems to be depict the high-status woman as indulging in her own sexual desires and acting on her own will, disregarding reason, counsel and sense, while the man of lesser-status is considered handsome but bears little or no responsibility for seducing the woman. He is of less interest to contemporary chroniclers. Woodville seems to be an exception, rather than the norm, in being seen as guilty of social climbing and there it is the marriage of his daughter, not his own marriage, that gave that reputation. Owen Tudor, as the patriarchal originator of the Tudor dynasty, was celebrated by Tudor-era writers for his qualities and Welsh lineage - it would be easy to conclude that had he not been the grandfather of Henry VII, he would be entirely forgotten.

There do not seem to be any contemporary claims than Tudor, Holland or Woodville seduced, bewitched or raped their wives, whatever historical fiction novelists or pop historians claim. However, it should be noted that there are many cases where other high-status women could be abducted and forced into marriage. One example is Alice de Lacey, Countess of Lancaster. For those cases, I suggest reading Caroline Dunn's Stolen Women. It is far too long and complicated subject to summarise in a tumblr post.

Sources:

Caroline Dunn, Stolen Women in Medieval England: Rape, Abduction, and Adultery, 1100–1500 (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

David Green “‘A woman given to slippery ways’? The reputation of Joan, the Fair Maid of Kent”, People, Power and Identity in the Late Middle Ages: Essays in Memory of W. Mark Ormrod (Routledge, 2021, eds. Gwilym Dodd, Helen Lacey, Anthony Musson)

Katherine J. Lewis, “Katherine of Valois: The Vicissitudes of Reputation”, Later Plantagenet and the Wars of the Roses Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty (eds. J. L. Laynesmith and Elena Woodacre, Palgrave 2023)

Kavita Mudan Finn, The Last Plantagenet Consorts: Gender, Genre, and Historiography, 1440-1627 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

W. Mark Ormrod, "In Bed With Joan of Kent: The King's Mother and the Peasants Revolt", Medieval Women: Texts and Contexts in Late Medieval Britain (ed. Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, Rosalynn Voaden, Arlyn Diamond, Ann Hutchison, Carol Meale, and Lesley Johnson, Brepols 2000)

Lynda J. Pigdeon, Brought Up Of Nought: A History of the Woodville Family (Fonthill 2019)

#god i hope this makes sense as i'm tired and i've been working on this for too long#also i don't know a lot about the woodvilles so most of my discussion of them is drawn from a quick research session so#jacquetta of luxembourg#richard woodville#joan of kent#thomas holland#catherine de valois#owen tudor#asks#anonymous#text posts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWQ 10th Anniversary

THE WHITE QUEEN 10-Year Anniversary Week

->Favorite Villain

In the midst of playing fast and loose with known historical facts, its wild costuming decisions, and some deeply questionable narrative choices, the one thing that stood out in The White Queen was the portrayal of its central cast of characters, all women, cast in various shades of grey, caught somewhere between damsel in distress and femme fatale. Not especially heroic, they were nevertheless complex and layered. In protecting what was important to them (their children), they strayed far from what tradition requires of heroines: to be pure, good-natured, ethical. Indeed, their behavior often called into question what it means to be a heroine. They were all villains!

Or were they? What if they were just victims of this story's ultimate and invincible villain, Fortune's Wheel?

“Fortune's wheel takes you very high and then throws you very low, and there is nothing you can do but face the turn of it with courage.”

#twq10#the white queen#of mothers and daughters#historical shenanigans#jacquetta of luxembourg#elizabeth woodville#nan beauchamp#margaret beaufort#margaret of anjou#cecily neville#isabel neville#anne neville

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 12 July 1467, before the battle of Edgecote, Warwick and the duke of Clarence released a manifesto attached to a petition by Kent rebels. In it, they spoke against the:

disceyvabille covetous rule and gydynge of certeyne ceducious persones; that is to say, the Lord Ryvers, the Duchess of Bedford his wyf, ... Ser John Wydevile and his brethren, Ser John Fogge, and other of theyre myschievous rule opinion and assent, wheche have cause oure seid sovereyn Lord and his seid realme to falle in grete poverte of myserie, disturbynge the mynystracion of the lawes, only entendyng to thaire owen promocion and enriching.

Jacquetta was the only woman named in the manifesto, among important knights and influential men at court, all men of war, and the fact that she was mentioned shows that she was regarded as politically important in her own right, and not merely as Rivers' wife. The manifesto was meant as propaganda for the general public and written to appeal to the masses. Perhaps this is why Warwick and Clarence felt the need to clarify that the duchess of Bedford was Rivers' wife. There do not seem to be many other occasions during this period in which a woman was particularly singled out in this way. The duchess of York, for example, was not implicated in her husband's many quarrels with Henry VI and his councillors. Jacquetta's inclusion shows, at the very least, that Warwick and Clarence considered her powerful and influential in court and had a very personal hatred against her.

Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Duchess of Bedford and Lady Rivers (c. 1416 - 1472), Lucia Diaz Pascual

#she 😌#jacquetta of luxembourg#jacquetta woodville#the wars of the roses#history#english history#mine*#quotes

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the white queen really made jacquetta of luxembourg the 15th century kris jenner

#this is why she was the most entertaining character on the show#tough to be fair wotr really was just a particularly wild season keeping up with the plantagenets#jacquetta of luxembourg#the white queen#the lady has spoken

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Almost) Every Costume Per Episode + Jacquetta Woodville's light blue gown in 1x02

#The White Queen#TheWhiteQueenEdit#weloveperioddrama#perioddramaedit#period drama#historical drama#Jacquetta Woodville#Jacquetta of Luxembourg#TWP 1x02#The Price of Power#costumeedit#costumes#costume drama#Almost Every Costume Per Episode#Awkward-Sultana

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WHITE QUEEN 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY WEEK | Day 1 (August 14): Favorite Episode → 1.01 In Love With the King

You are a girl from the house of Lancaster, and you live in a country that is divided. You may not fall in love with a York king, unless there is some profit in it for you. Your life will not be easy because you wish it to be so. You will have to wade through blood and you will know loss, you must be stronger.

#the white queen#twqedit#perioddramaedit#twq10#elizabeth woodville#edward iv of england#jacquetta of luxembourg#S1E01 In Love With the King#my edits

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WHITE QUEEN 10-YEAR ANNIVERSARY WEEK

Day Three - Most Underrated Character: Richard Woodville, 1st Earl of Rivers

#the white queen#twq#twqedit#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#weloveperioddrama#perioddramagif#twq10#filmtvcentral#smallscreensource#cinematv#showedit#tvedit#richard woodville#earl of rivers#robert pugh#rebecca ferguson#janet mcteer#elizabeth woodville#jacquetta of luxembourg#my edit

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me and my other personalities are having such a great day.

Me: Don't tell me you want to insert all these Bible verses into the manuscript!

Also me: Only a heretic would say such a thing! Get her! You shall burn at the stake for this, witch!

#15th century#wars of the roses#medieval england#medieval#writting#author#book writing#cecily neville#richard of york#house of york#henry vi#margaret of anjou#humphrey duke of gloucester#jacquetta of luxembourg#richard woodville#my writing#proud cis

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 notes

·

View notes