#jess zimmerman

Text

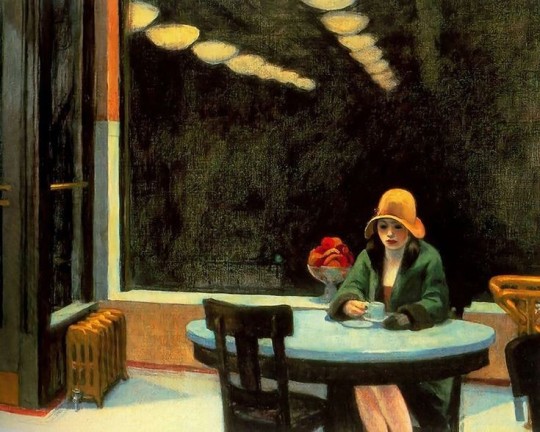

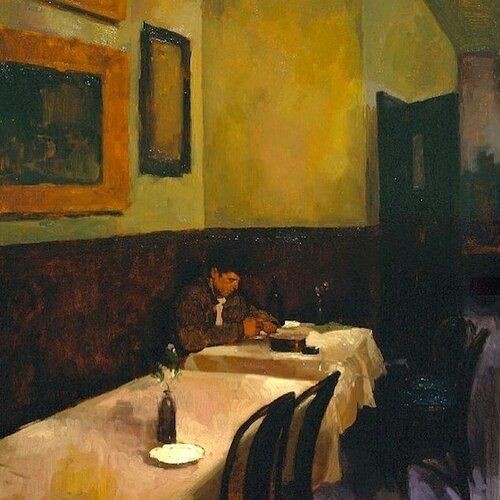

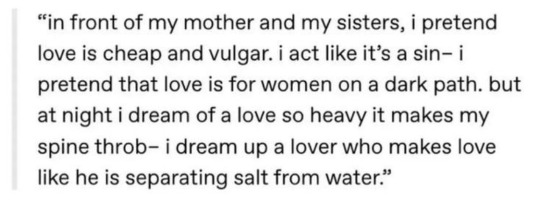

#web weaving#salma deera#jenny slate#words words words#jess zimmerman#on love and shame and hunger#edward hopper#joseph lorusso#Dmitry Lisichenko#putting nobody by mitski in it would be too predictable

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

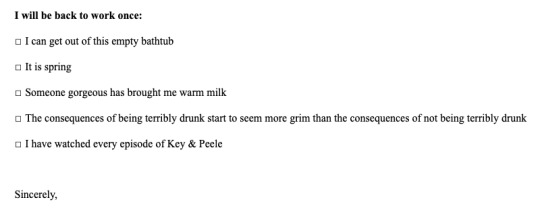

Jess Zimmerman, "Why I Am Not Coming In To Work Today" (The Toast, December 2013)

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

excerpts from "Hunger Makes Me" by Jess Zimmerman

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being a teenage girl is dramatic in part because it’s your first, chilliest dunking in the certain knowledge that your body is your worth. I’d been a chubby kid, and so the idea that my body was a source of shame wasn’t new to me, but previously I’d only been a disappointment to my family. Now, I was understanding that an unbeautiful woman is an unfulfilled promise to the world.

I realize now that some of this is illusion—that those promises were made on my behalf, without my input, by people who didn’t have my best interests at heart.

Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology by Jess Zimmerman

#jo's birthday takeover#book quote#women and other monsters#jess zimmerman#nonfiction#mythology#feminism#quote#quotes#booklr#bookblr

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

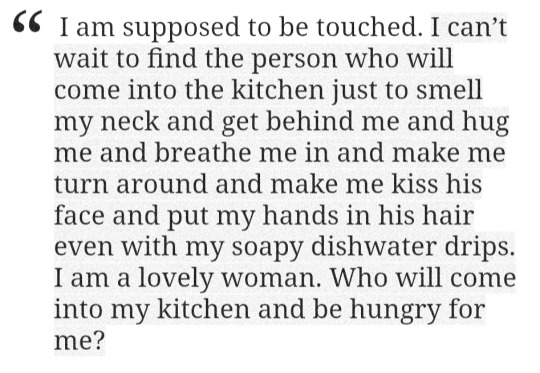

Hunger makes me

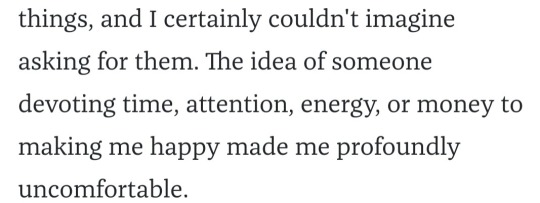

To desire effort from a man, we are taught, is to transgress in several ways. (This is true even if you’ve never had or wanted a romantic relationship with a man.) First, it means acknowledging that there are things you want beyond what he’s already provided — a blow to his self-concept. This is called “expecting him to read your mind,” and we’re often scolded for it; better, we learn, to pretend that whatever he’s willing to give us is what we were after anyway.

Second, and greater, it means acknowledging that there are things you want. For a woman who has learned to make herself physically and emotionally small, to live literally and figuratively on scraps, admitting that you have an appetite is a source of cavernous fear. Women are often on a diet of the body, but we are always on a diet of the heart.

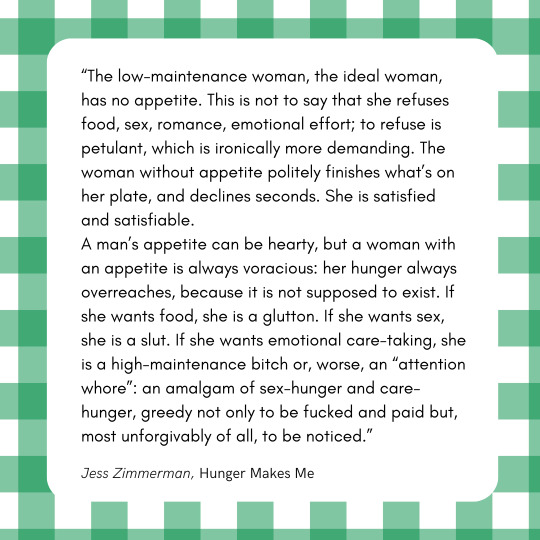

The low-maintenance woman, the ideal woman, has no appetite. This is not to say that she refuses food, sex, romance, emotional effort; to refuse is petulant, which is ironically more demanding. The woman without appetite politely finishes what’s on her plate, and declines seconds. She is satisfied and satisfiable.

The secret to satiation, to satisfaction, was not to meet or even acknowledge your needs, but to curtail them. We learn the same lesson about our emotional hunger: Want less, and you will always have enough.

A man’s appetite can be hearty, but a woman with an appetite is always voracious: her hunger always overreaches, because it is not supposed to exist. If she wants food, she is a glutton. If she wants sex, she is a slut. If she wants emotional care-taking, she is a high-maintenance bitch or, worse, an “attention whore”: an amalgam of sex-hunger and care-hunger, greedy not only to be fucked and paid but, most unforgivably of all, to be noticed. […]

The attention whore is every low-maintenance woman’s dark mirror: the void of hunger we fear is hiding beneath our calculated restraint. It doesn’t take much to be considered an attention whore; any manifestation of that deeply natural need to be noticed and attended to is enough. You don’t have to be secretly needy to worry. You just have to be secretly human. […]

When I said “I don’t like romance,” it was the equivalent of a dieter insisting she just doesn’t want dessert. I did want it—I just thought I wasn’t allowed.

People frequently claim that eating disorders, like anything common to adolescent girls, are just “a cry for attention.” As someone who was once an adolescent girl, I suspect they are at least partially the opposite: a cry against hunger and need, an attempt to kick away that profoundly human desire to be paid mind. To shut the door on the void.

Fearing hunger, fearing the loss of control that tips hunger into voraciousness, means fearing asking for anything: nourishment, attention, kindness, consideration, respect. Love, of course, and the manifestations of love. It means being so unwilling to seem “high-maintenance” that we pretend we do not need to be maintained. And eventually, it means losing the ability to recognize what it takes to maintain a self, a heart, a life. […]

Women talk ourselves into needing less, because we’re not supposed to want more—or because we know we won’t get more, and we don’t want to feel unsatisfied. We reduce our needs for food, for space, for respect, for help, for love and affection, for being noticed, according to what we think we’re allowed to have. Sometimes we tell ourselves that we can live without it, even that we don’t want it. But it’s not that we don’t want more. It’s that we don’t want to be seen asking for it. And when it comes to romance, women always, always need to ask.

There’s a YouTube video I’m fond of that shows a baby named Madison being given cake for the first time. The maniacal shine in her eyes when she first tastes chocolate icing is transcendent, a combination of “where has this been all my life” and “how dare you keep this from me?” Jaw still dropped in shock, she slowly tips the cake up towards her face and plunges in mouth-first. Periodically, as she comes up for air, she shoots the camera a look that is almost anguished. Can you believe this exists? her face says. Why can’t I get it all in my mouth at once?

This video makes me laugh uproariously, but it’s that throat-full-of-needles laugh that, on a more hormonal day, might be a sob. The raw, unashamed carnality of this baby going to town on a cake is like a glimpse into a better, hungrier world. This may be one of the last times Madison is allowed to express that kind of appetite, that kind of greed. She’s still young enough for it to be cute.

This is Madison’s first birthday. By the time she’s 10, there’s an 80 percent chance she’ll have been on a diet. By high school, she’s likely to have shied away from expressing public opinions; she’ll speak up less in class, bite back objections and frustrations, shrug more, stay silent, look at the ground. She’ll worry about seeming “good”—which means not too pushy, not too demanding, not too loud. (Only bitches want better. Only sluts want more.) Boys will treat her shoddily, and she will find ways to shrink herself into the cracks they leave for her. She will learn to assert less, to demand less, to desire less. She won’t grab for anything with both hands; she won’t tip anything towards her face and plunge in. And that transcendent anguish, that stark gluttony … well, at least we’ll have it caught on video.

What would it take to feel safe being voracious? What would it take to realize that your desires are not monstrous, but human?

Imagine being Madison, grown up but undimmed. Imagine being the woman who is unabashed about needing food to survive and pleasure to be fulfilled and care to be happy. Imagine prying open the Pandora’s box where you hide your voraciousness, and letting it consume indiscriminately, and realizing that the world is not destroyed. Imagine saddling up the seven-headed beast of your hunger and riding it to Babylon.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most cultures have a female monster who preys on pregnant women, fetuses, newborns, and children. It's a near-universal nightmare: the creature who rips babies from the womb or steals them from the cradle. her name is Abyzou, Penanggalan, Lamashtu, La Llorona. Her purpose is sometimes to scare children into compliance, but it's often to scare women into compliance as well. Only monsters stand in the way of the natural order: women as incubators, as conduits for birth.

In ancient Greece, the baby stealer's name was Lamia. The myths agree on her name, and her role as a murderer of children, and that's about it. Her backstory and her appearance vary almost psychedelically from story to story. In some, she is a sea monster; her name is the ancient Greek for a rogue shark. In others, she is half-woman, half-snake -- or, as in Keats's poem "Lamia," a multicolored snake with a woman's mouth. In some, she is even plural: the Lamiae, a swarm of vampiric demons. She also appears in a seventeenth-century bestiary with a woman's face and breasts, a four-legged body, front paws, back hooves, scales, and a penis and testicles. Unlike so many of her sister monsters -- snake-haired Medusa, lion-bodied Sphinx -- the important feature of Lamia is not what she looks like, but what she does. The fear of the monstrous mother can have many faces, many forms.

Zimmerman, Jess. Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology. Beacon Press, 2021.

#jess zimmerman#women and other monsters#women and other monsters: building a new mythology#on female monsters#excerpts#prose#nonfiction#*

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

hii love your blog

was wondering if you have any book recs for those interested in learning about myths ?!

genuinely 99% of my myth-learning recommendations are gonna be podcasts or youtube videos cause i’m of the weird opinion that we should be preserving the oral tradition its way more fun to listen to myths as stories.

that being said!

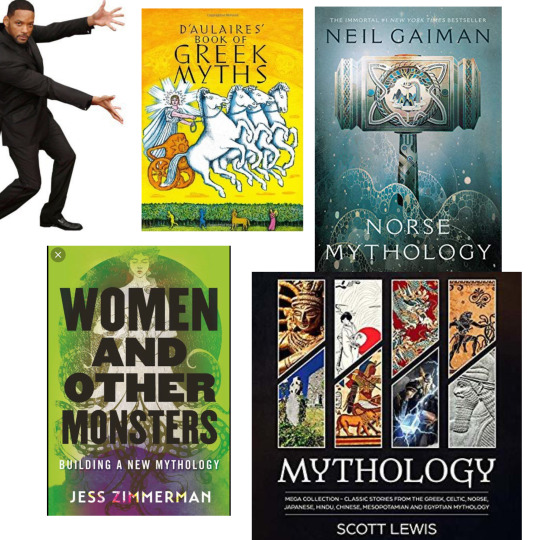

my interest is piqued by 1) a pared down stick-to-the-facts version (mythology by scott lewis) 2) cool art (d’aulaires) 3) ‘this is just straight up a well written story’ (norse mythology) 4) people rubbing their dirty SJW paws all over classic myths (women and other monsters).

ofc if you’re looking for the BEST way to learn about mythology, that would be listening to The Unfair Folk Podcast

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary: This collection of essays explores the experience of women through the lens of female monsters from Greek Mythology.

Quote: "Not every monster devours, but the drive to consume—to gobble up children, or swallow the sun, or eat young women’s hearts—is considered a monstrous trait. Outsize hunger is the province of the monster, and for women, all hungers are outsize.”

My rating: 3.5/5.0 Goodreads: 3.79/5.0

Review: In some ways this feels like internet feminism. Zimmerman draws broad conclusions from her own personal life, the Greek myths sometimes no more than an aesthetic prop for the point she’s making. They’re very well-written broad conclusions, though, and Zimmerman’s willingness to be vulnerable about her personal life lends them poignancy. If you go in accepting these more as personal essays than anything deeply engaging with Greek myth, they can be quite moving.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What was it like for the sirens on their lonely rock, watching everyone who tried to love them drown?"

Jess Zimmerman, Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

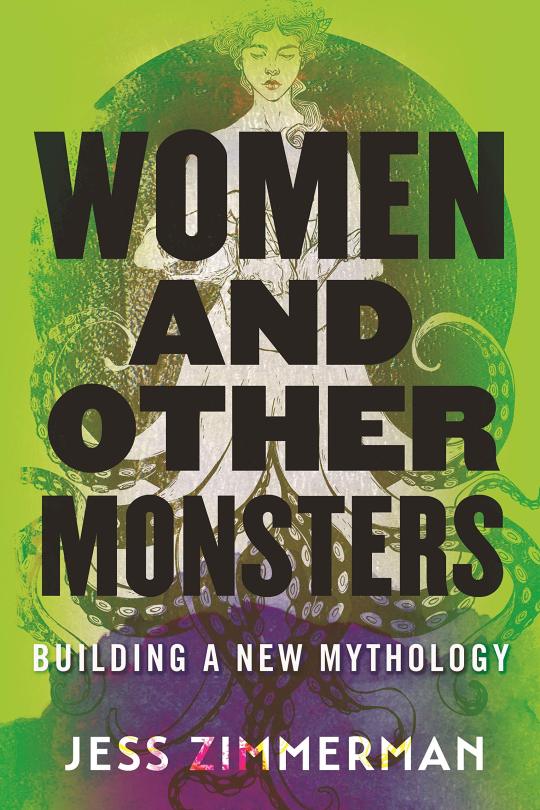

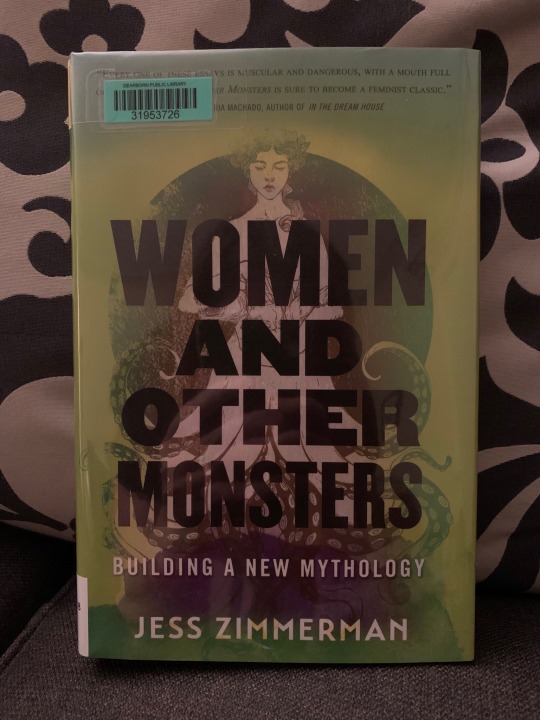

Title: Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology

Author: Jess Zimmerman

Series or standalone: standalone

Publication year: 2021

Genres: nonfiction, feminism, mythology, history, memoir

Blurb: The folklore that has shaped our dominant culture teems with frightening female creatures. In our language, in our stories (many written by men), we underline the idea that women who step out of bounds - who are angry or greedy or ambitious, who are overtly sexual or not sexy enough - aren’t just outside the norm...they’re unnatural, monstrous. But maybe the traits we’ve been told make us dangerous and undesirable are actually our greatest strengths. Through fresh analysis of eleven female monsters - including Medusa, the Harpies, the Furies, and the Sphinx - Jess Zimmerman takes us on an illuminating feminist journey through mythology. She guides women and others to reexamine their relationships with traits like hunger, anger, ugliness, and ambition, teaching readers to embrace a new image of the female hero: one that looks a lot like a monster, with the agency and power to match. Often, women try to avoid the feeling of monstrousness, of being grotesquely alien, by tamping down those qualities that we’re told fall outside the bounds of natural femininity...but monsters also get to do what other female characters - damsels, love interests, and even most heroines - do not. Monsters get to be complete, unrestrained, and larger than life. Today, women are becoming increasingly aware of the ways rules and socially constructed expectations have diminished us. After seeing where compliance got us - harassed, shut out, and ruled by predators - women have never been more ready to become repellent, fearsome, and ravenous.

#women and other monsters#women and other monsters building a new mythology#jess zimmerman#standalone#2021#nonfiction#feminism#mythology#history#memoir

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jess Zimmerman, Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology.

#women and other monsters#book quotes#book excerpts#jess zimmerman#dark academia aesthetic#dark academia quotes

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

So when I said, 'I don't like romance,' it was the equivalent of a dieter insisting she just doesn't want dessert. I did want it–I just thought I wasn't allowed.

Jess Zimmerman

0 notes

Text

Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology by Jess Zimmerman

1 note

·

View note

Text

People look through your face, or past it, when there’s nothing there they want. They’re not afraid to meet your eyes—they just don’t see the point.

Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology by Jess Zimmerman

#book quote#women and other monsters#jess zimmerman#nonfiction#mythology#feminism#quote#quotes#booklr#bookblr

10 notes

·

View notes