#jewish cemetery berlin

Text

#couplesmatching#couple#jewish cemetery#weissensee#stefandraschan#photography#contemporaryart#berlin

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The concept of the new antisemitism was popularized in The New Anti-Semitism, which was published by the Anti-Defamation League in 1974, was given some modest intellectual heft by the Orientalist Bernard Lewis in his 1986 book Semites and Anti-Semites, and has since been mainstreamed in some “working definitions” of antisemitism, from that deployed by the European Union Military Committee to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s highly controversial definition.

The thrust of the new antisemitism thesis is that Israeli military aggression was really self-defense and that solidarity toward Palestinians was really antisemitism. Thus the French essayist Alain Finkielkraut could describe 2002, when many people protested against Israel’s ravaging of the West Bank during Operation Defensive Shield, as a “Kristallyear”; four years later, Lewis compared the atmosphere resulting from Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 2006 to that of 1938.

Those statements are functionally antisemitic. Most definitions of antisemitism, “working” or otherwise, agree that it is antisemitic to fail to distinguish between the state of Israel and Jews. It follows as surely as night follows day, that it is antisemitic to fail to distinguish between opposition to the state of Israel on internationalist, anti-colonial, and anti-racist grounds and hostility to the Jews as such. But Israel apologia depends precisely on obliterating the distinction between itself and Jews. Israel must represent itself, no matter how many Jewish people reject its embrace or protest against it, as “the state of the Jews,” the “Jew of nations,” the national self-defense of a people who could only exist elsewhere as a “foreign” element.

That is what conservative politicians around the world are doing when they criminalize Palestine solidarity on the spurious basis of opposing antisemitism; that is what Britiain’s prime minister, Rishi Sunak, is doing when he talks as if all Jews support Israel; that is what authorities in Berlin and France are doing when they ban Palestine protests. They may not be desecrating cemeteries or synagogues, but their logic is the same as that of some of those who do.

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Meditation In Berlin

To Bostjan and Martin Holding on to love

Neue Wache, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

In the summer of 2023, I came looking for the sacred in Berlin. Curious of the fact that the German capital was the site of the future House of One, a shared ground of worship for the three main monotheistic religions, I wanted to investigate how faith intertwined with the fabric of the city. What forms of sacred practices had developed in formal and informal ways in the rich interwoven cultures of this European crossroad? What could we learn from their spatial expression? I was busy preparing my research itinerary, when, a couple of days before my arrival, I received news that the husband of the friend inviting me to Berlin had tragically passed.

The shock of sudden death brought back memories of loss and pain. It altered the way I could, and needed to engage with the city. I looked at the map. My eyes held onto the shape of old scars, onto the names of memorials and cemeteries. I was drawn into the sacred nature of places of remembrance.

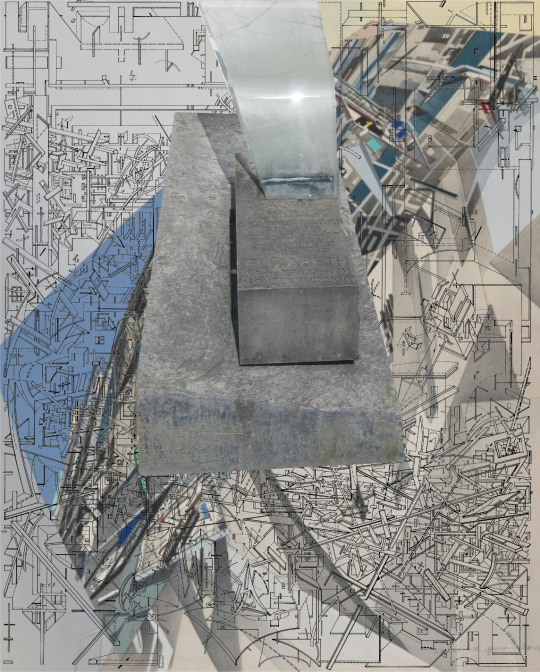

Holocaust Memorial, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

As I arrived in Berlin, I went straight to the Holocaust Memorial. Peter Eisenman and Buro Happold’s design was vivid in my mind, a powerful display that had caught my attention back when I was an architecture student. The sun was shining bright on the day of my visit, throwing stark lights and shadows on the concrete blocks. Being familiar with the architects’ design - their decision to offer uneven ground and varying block heights in order to invite reflection and unease - did not prepare me with the eerie sense of dread and sadness that I would experience. One of the main and unexpected factors of unease was the number of tourists walking the grounds alongside me. Dozens of people were talking loudly, screaming, laughing. I came across a child running, dashing through the blocks, then immediately vanishing away. Later, I saw a couple of instagramers taking selfies. The glaring sun made it hard to see properly ahead. Constantly running into strangers made me uneasy. As I went deeper and deeper into the labyrinth of stylized tombs, towering high above my own height, I was aware of a growing sensation of danger. Loud male voices echoed, and tall men would emerge suddenly, laughing, then disappear again. I left, feeling deprived of the meditation I had hoped for, from grounds that suddenly felt hostile.

Holocaust Memorial, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

At its core, sacredness is hard to define. It is something more easily felt than described. Thinking that maybe I needed some quiet, I walked towards the Brandenburger Tor. Right in the epicenter of Berlin’s most famous tourist location, the Room of Silence (Raum der Stille) has been built to allow for a space of rest for all, for “relaxation, prayer, remembrance, meditation and contemplation”. It embodies a functionalist approach to the sacred, like the oecumenic chapels one might find in hospitals or airports. The specificity of the German language gives it a special twist, “Stille” meaning both silence and immobility. I settled on a chair inside the white room and waited. A couple was present, but left after a few minutes. I sighed and tried to relax, looking around at the furniture, and the abstract painting on the wall. Yet all I could hear was the loud jackhammers from a nearby construction site, an ongoing drum that would not stop. In the room of silence, I found no silence and no rest. Maybe I would find it elsewhere.

Raum Der Stille, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

On my way to the old Jewish Cemetery, I called my best friend and got lost. The cemetery I found instead was the St. Elisabeth-Friedhof. It is set in an open field, full of healthy trees and open lawns, with uncovered tombs, covered in grass, that made the place look like a Muslim cemetery. Mothers were walking around with babies in strollers and younger children, wandering calmly in the shade. Traces of love were scattered around, in the fresh flowers, in the decorative candles, in the words engraved in stone. I thought of the grief of my friend, and wondered what words of love he would choose. Later, I learned that the Berlin Wall once ran along the cemetery wall. The Wall did, in fact, follow the borders of cemeteries whenever it could, as my friend Fabian Saul, a long-time city expert, would later point out. Cemeteries offered open grounds, with limited demolition needed in order to erect the separation wall. The graves bore the brunt of the assault, with many being dug up, displaced or simply erased to make way for the fortified border. Upon hearing this story, I reflected on the people that had been shot on top of desecrated graves, layers upon layers of death. It sat at odds with the quiet beauty, with the children in strollers, with the apparent peace.

St.Elisabeth-Friedhof, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

Alter Garnison Friedhof, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

Exiting the St.Elisabeth-Friedhof through the north,I found myself walking through fields of hay, gently swaying in the breeze, shimmering in the setting sun. A massive metal cross was half buried in the ground, as if freshly fallen from the sky. I had stumbled upon the Chapel of Reconciliation, built in 1999 on the grounds of an ancient church, demolished by the East German Government only four years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, which ran right by its doors. The building was blown up, the cross on the tower fell, and it was hidden by church members until the reconstruction. Berlin architects Rudolf Reitermann and Peter Sassenroth collaborated with clay specialist Martin Rauch to design the first rammed earth church in Germany. The Chapel of Reconciliation emerges from the landscape as a natural extension, in wood and clay, as if ushering the reconnection of humans to fellow humans, and humans to the land.

Chapel of reconciliation, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

When I told Fabian Saul, editor of Flaneur, about my quest for sacred spaces and remembrance, he took me to Koppenplatz, a small square that is host to one of the very first Holocaust memorials erected in Berlin. The memorial stands on top of a hidden burial ground, unmarked and nearly forgotten. In the 18th century, it was open to the poor, the orphans and suicides of the popular and jewish Scheunenviertel neighborhood. Today, the metal sculpture of an eerily familiar scene stands vigil in the square: the “Deserted Room” represents a table with two chairs on a stylized parquet. One of the chairs lays on the ground, as if recently fallen, a powerful evocation of the forced displacements and deportations that emptied the neighborhood of its jewish population. As we strolled through the quaint square, reflecting on its history, walking on hidden graves, Fabian described how some of his friends would always avoid this place, describing a feeling of unease that they cannot quite understand. I pondered at the intertwined layers of remembrance, at the tree roots digging in the graves of the nameless departed.

Koppenplatz, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

Große Hamburger Straße memorials, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

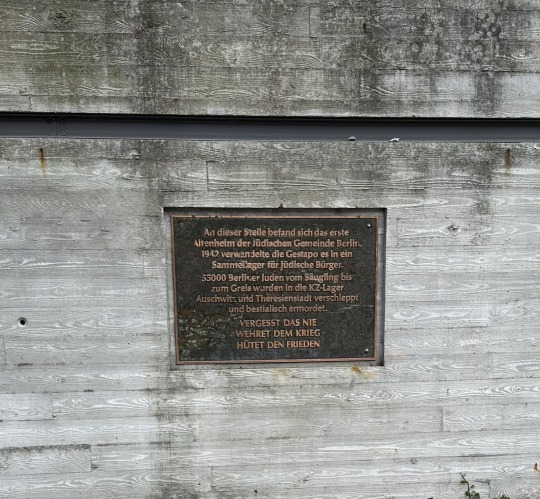

Walking with grief, I had seen so many places of death and destruction in Berlin, and of eerie beauty. Yet somehow, the one that struck me the most was the Memorial of the Old Jewish Cemetery in the Mitte district. It used to be the city's oldest jewish cemetery, before being destroyed in 1943 by the Gestapo. Tombstones and human remains were forcibly removed. A zigzag trench was dug through the graveyard, the bones of the dead were pulled out of the ground and the gravestones were smashed. The deliberate effort to erase the very presence of the dead from the ground, to make the earth forget, to utterly and completely obliterate the memory of the departed, was chilling. Now, the cemetery had become a memorial park, and there were no more tombstones, and apart from a few famous ones, the names were lost. I stood at the gates for a long time. For the very first time in my life, I was seeing a cemetery for a cemetery.

Old Jewish Cemetery Memorial, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

My exploration of Berlin had mainly been solitary, and it was time for community. I left for the House of the Cultures of the World - (Haus der Kulturen der Welt), where I would meet my grieving friend, and fellow researchers from the LINA program. I arrived at the Water Basin,next to the temporary pavilion built by Raumlabor, with fringes that shimmered in the setting sun. In an unexpected turn of events, that very evening happened to be the re-opening of the Cultural center. Crowds of artists from Berlin and the Global South were convening under the invitation of new director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. The program read as “Acts of Opening Again. A Choreography of Conviviality”. Music, laughter and conversations were everywhere. Feeling both disconnected and energized by the crowd, I witnessed the rebirth of a long sleeping dream.

Raumlabor Pavilion, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

I found my friends by the water. We did not share a religion. But we held hands, and for the first time in my life, I led Salât El-Janaza, the prayer of the Dead.

إنّا لله و إنّا إليه راجعون

Skulpturen gegen Krieg und Gewalt, 2023 © Meriem Chabani

Meriem Chabani | Photo © Kaname Onoyama

-

by Meriem Chabani (New South) - Digital Architectuul Fellow of LINA

Read also Architectuul' Digest HERE

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

It depends what you count as Eastern Europe but my Jewish (father's) ancestry has one line from Krotoshin, which at the time was Kingdom of Prussia, and another from - we think - Lithuania. There is also another line from Berlin and another from somewhere else in Germany/Prussia. All had migrated to Melbourne, Australia, by the beginning of the 20th century. My father was born there but eventually settled in Perth, Australia, where I was born. I would love to know more about Jews in the region that shifted between Polish and Prussian rule. The Krotoshin line spoke German and culturally identified as German/Prussian, but the region was once part of Poland and now is again. By the way, I've wanted to say that I love this blog!

Thank you for your story and your nice words! The community of Krotoshin is actually a very old one. It was established in the 14th century, and by virtue of an ancient privilege allowing the Jews to trade, engage in crafts, and build houses, the community prospered. The wealthier Jews (most of them traders of grain and seed) had close commercial connections to Breslau, Leipzig, and Frankfurt on the Oder and Krotoschin also became a center of Hebrew and Yiddish publishing in Prussia. In the course of the wars which ravaged Poland in the 17th century, the Jews suffered severely. Polish troops headed by the hetman Czarniecky murdered 350 Jewish families out of 400 in 1656 during the war against the Swedes. A fire in 1774 destroyed the Jewish quarter, including the 16th-century synagogue, the bet midrash, and the library. At the time the Jews numbered 1,384 (37.5% of the total population).

During the period leading up to the early 20th century Krotoschin's Jewish population began to decline significantly. The Prussian wars of the late 19th century and World War I contributed to this decline; many Jews fled to Germany and South America. During the inter-war period, when Krotoschin was returned to Poland, the Jewish community had dwindled to 50 members. As of 12 September 1939, only 17 Jews remained, and after the outbreak of World War II they fled to Łódz, where they were presumably killed during the German occupation.

The Jewish cemetery, founded in 1638 also served Jews from the nearby localities of Leszna, Kobylina, Kępna, Zdun, Ostrowa Wielkopolskiego and Wroclaw. Buried there are Rabbi Menachem Mendel Ben Krotoszyński Auerbach (d. 1689); Jewish martyr Moses Karpeles from Prague (d. 1729) and the famous rabbi of Wroclaw, Chajjim Jon. During WWII, the Nazis damaged the cemetery's gravestones and used them as building blocks in many places of the town. On a part of the cemetery, residential buildings were erected during the communist period. The former mortuary house is now a library. The only visible gravestone from the cemetery is exhibited in the Regional Museum of Krotoschin, that of Jakub, who died in February 21, 1722.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Matzevah's Echo: Threads of Life in Architecture's Embrace"

In the echoes of ancient Hebrew tongue,

Matzevah stands, a ballad unsung.

A sacred pillar, a standing stone,

Inscribed in tales, in history's own.

From Genesis' verses, a whisper profound,

Jacob's stone, a pact unbound.

"I set this for a pillar," he declared,

God's house in stone, a vow ensnared.

Through time's embrace, the term extends,

To Canaanites, Nabataeans, it transcends.

Archaeologists weave its ancient thread,

A symbol profound, of the silent dead.

In modern realms, a Matzevah anew,

A headstone, a marker, for those we once knew.

Rooted in 'standing,' a name and a vow,

A legacy etched, a sacred bow.

As an architectural student, a tale unfolds,

Under Boyarsky's reign, where innovation molds.

Zaha Hadid and Libeskind's stars ascend,

In a dance with death, an education to transcend.

Libeskind, a Jew, Hadid, a Muslim's grace,

In architectural realms, a harmonious space.

Their designs converge, a balance refined,

In the dance of cultures, beautifully twined.

Boyarsky, the visionary, met his fate,

A Matzevah stands at the cemetery's gate.

Designed by Bunschoten and Chiaradia's hand,

A tribute profound to architecture's stand.

In Berlin's embrace, architecture blooms,

A narrative woven in contemporary looms.

Timely whispers in Israel's conflicted gaze,

Matzevot stand, a culture's praise.

The ongoing dance, conflict's cruel plight,

Matzevot witness, in day and night.

Symbols profound, in Jewish and Islamic sung,

A bridge between realms, where lives and faiths are strung.

Berlin's structures rise, a testament grand,

In echoes of Matzevahs, a cultural stand.

Symbols immortal, in architecture's embrace,

A reminder of life, in every sacred space.

#MatzevahMelody#ArchitecturalHarmony#CulturalBalance#LibeskindHadidDance#JudaismIslamDesign#SymbolicBridges#ArchitecturalNarratives#BerlinEchoes#CulturalHarmony#faithfulspaces

0 notes

Note

Book or movie recommendations?

book recs: solitaire by alice oseman, radio silence by alice oseman, wilder girls by rory power, any and all tales and poems that edgar allan poe wrote, the land of stories series by chris colfer, a tale of magic by chris colfer, a tale of witchcraft by chris colfer, the perks of being a wallflower by stephen chbosky, the book wanderers series by anna james, anne of green gables by l. m. montgomery, cemetery boys by aiden thomas, a bookshop in berlin by françoise frenkel (a memoir of her escape from the n*zis), h*tler, my neighbo- memories of a jewish childhood, 1929-1939 by edgar feuchtwanger with bertil scali (memoir of a jewish boy who grew up across the street from adolf), girl in the blue coat by monica hesse (historical fiction, h*locaust), night by elie wiesel (memoir on his time in a c*ncentration c*mp)

movie recs: portrait of a lady on fire, the virgin suicides, everything everywhere all at once, level 16, call me by your name, mean girls, clueless, girl interrupted, confessions of a teenage drama queen, the giver, coraline, 10 things i hate about you

1 note

·

View note

Text

Władysław Szpilman - The real Pianist rests in Warsaw

A Polish pianist and classical composer of Jewish descent. Szpilman is widely known as the central figure in the 2002 Roman Polanski film The Pianist, which was based on Szpilman’s autobiographical account of how he survived the German occupation of Warsaw and the Holocaust.

Władysław Szpilman’s grave in Powązki Military Cemetery in Warsaw / Image source

Szpilman studied piano in Berlin and…

View On WordPress

#composer#film#grave#pianist#Piano#Powązki Military Cemetery#Roman Polanski#The Pianist#World War II#Władysław Szpilman

0 notes

Text

Tourism PR starts at the front door!

Berlin is a city steeped in history, which has preserved many traces of the past. From the medieval merchant city to the Prussian residence to the divided and reunited capital of Germany, Berlin has undergone many transformations. Some of the places that tell the story of Berlin are Gendarmenmarkt, Weissensee Jewish Cemetery, Tempelhof Airport and the Berlin Wall.

The Berlin Wall was a symbol of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Today is Tuesday, December 13; a travel day by train to Dresden which is several hours southeast of Berlin near the Czech border. A city with a tragic history from World War II, I am anxious to see how a city that endured massive firebombing and killed 25,000 people toward the latter days of the war has become the Dresden of today.

As usual I am far behind in writing but we are in Berlin until noon today. I must say that I am absolutely freezing, the temperatures keep falling and snow is in the forecast. Dresden will be even colder, low teens. Anyone that knows me will chuckle at the thought of me enduring this cold. My reptilian need for direct heat is impossible to find:(. I keep thinking how balmy 60 degrees will feel in Lisbon once we get there on the 20th December.

Yesterday, Monday, the 12th December, we took the opportunity to again, walk around a very old area in former East Berlin that has become a bohemian “hip” area in which to live. Before Berlin was again united in 1989, the area was mostly drab, unpainted and unkept; thus the usual commentary of the east being completely gray and the west lively and colorful.

There was one poignant and sad moment when we passed a former Jewish cemetery, the oldest in Berlin dating back to the mid 17th century that was completely destroyed in 1943. Several thousand Jews were taken out of the surrounding apartments and houses and many sent to death camps. Others were shot on site. It is impossible to even imagine and even more disturbing that it was only eighty years ago. One of the buildings which is pictured below still has the bullet holes from this massacre. And all along the sidewalks are the bronze plaques with the name of the person, birth and death dates and where they died.

We continued our walk around the area; there are now many shops and restaurants, one would never realize the past; thus why we must never forget. Berlin in ways is very sad as one begins to discover the sheer terror that took place during the Nazi regime but it also has become a vibrant, youthful city that seems to be straddling that huge divide. I’m not certain how one comes to terms with a past so violent and evil except to see it, acknowledgment it and never forget it. Berlin has done a remarkable job with all three.

My other impression of Berlin, which I eluded to earlier is the “missing” history since it was virtually destroyed during the war. The greater German Reich and a monumental Berlin which Hitler dreamed about has been replaced by a democratic and admirable country with a capital that has incredible modern architectural wonders and a feeling that the German people have created their own future future.

0 notes

Photo

Jüdischer Friedhof Weißensee

Kodak Gold 200

#35mm#film photography#photographers on tumblr#kodak gold 200#cemetery#weißensee#Jüdischer Friedhof Weißensee#jewish cemetery weißensee#weißensee cemetery#graveyard#berlin

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

jewish cemetery berlin

#brick#photography#light#sunshine#architecture#summer#depth#weissensee cemetery#jewish cemetery berlin#berlin#My Photo Blog#queued as can be

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

memorial jewish cemetery, berlin, 09/07/2019

this cemetery was so beautiful and eerie. it carried a sadness that engulfed my whole body

#dark academia#light academia#study#mine#studyblr#writblr#writeblr#jewish cemetery#jewish memorial#berlin#germany#art#painting#light academia aesthetic#dark academia aesthetic

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, Germany, 1998-2005

VS

Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery, Jerusalem, 1st millennium BC - today

#peter eisenman#berlin#memorial to the murdered jews of europe#germany#architecture#modern architecture#contemporary architecture#jews#cemetery#jerusalem#mount of olives#jewish#cube

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Let the world be the world, let the dream unfurl”.

Jüdischer Friedhof, Berlin-Weissensee

2017

#photography#photographers on tumblr#Jewish Cemetery#magen david#Star of David#jewish#Jüdischer Friedhof#berlin#dark#grey#gold#branches#nature#tree#architecture#Cemetery#no filter

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 9, the fateful day of the Germans

In several years on November 9, significant historical events happened in Germany, which shaped the future of the country. In detail, these are:

1848: Pro democracy revolutionist Robert Blum is executed in Vienna after being convicted for inflammatory speech. His death caused a radicalization of the pro-democracy movement, and he became a prominent identification figure for the early workers’ movement in Germany.

1918: Social Democrat politician Philipp Scheidemann proclaims the German Republic from a window of the Reichstag building in Berlin. A few hours later, Karl Liebknecht, leader of the communist movement, proclaims the Free Socialist Republic of Germany, meant to become a soviet state. During the following violent conflict, which took on civil war-like intensity in some places, the proponents of the pluralistic-democratic model prevail over the campaigners for a soviet republic.

1923: Adolf Hitler and former General Erich Ludendorff initiate the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich in a failed attempt to topple the yound republic. National Socialism makes international headlines for the first time. Hitler uses the following trial to promote himself as the leading figure of the German ethno-nationalist movement. Despite being convicted for five years in prison, he is released after 9 months for good conduct. He writes his infamous book “Mein Kampf” while in prison. November 9 becomes a memorial day during the Third Reich.

1938: The Night of Broken Glass marks the height of the November pogroms against the Jewish population in Germany. More then 1400 synagogues are destroyed, alongside with several thousand shops and homes owned by Jews. Jewish cemeteries are also devastated. About 30,000 Jews are sent to concentration camps where hundreds are killed and thousands die due to the circumstances of incarceration.

1967: During the inaugurational celebrations of the headmaster of the university of Hamburg, students show a poster saying “Unter den Talaren der Muff von 1000 Jahren” (”Under the gowns there is the must of 1000 years”), referring to the self-designation of Nazi Germany as the “1000 year-long empire”. The sentence became the symbol of the the 1968 student revolts in West Germany.

1969: The extreme-left terror organization Tupamaros West-Berlin plants a bomb in the Jewish Community Hall of West Berlin, which does not explode, but would have cause a huge bloodbath among the participants of a memorial service to commemorate November 9, 1938.

1974: Holger Meins, member of the extreme-left terror organization Red Army Fraction (RAF) dies after 58 days of hunger strike, causing a further radicalization of the group and the recruitment of a second generation of RAF terrorists.

1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall: The opening of the border between the two halves of Berlin and subsequently the two German states demonstrates the success of the peaceful revolution in East Germany, which ultimately leads to the reunification of Germany. The first border crossings were opened when huge crowds gathered at the eastern side after an ill-informed spokesman of the new East-German government erroneously told the public that the borders were open “now, with immediate effect”. Unable to reach any superior for receiving orders, the responsible commander of the checkpoint at Bornholmer Straße took the lone decision to open the barriers, feeling unable to disperse the crowd without violence and fearing a stampede in which innocent people would be crushed to death.

November 9 was considered as the national holiday of reunited Germany, but this idea was skipped due to the horrible events connected to national socialism. In the end, the day when the reunification came into effect, October 3, 1990, became the national holiday of Germany.

1K notes

·

View notes