#josephine tey

Photo

Mark Smith’s illustrations for Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time.

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

“She would fritter it away, of course, in small unimportances; so that in the end she would not know what she had done with it; but perhaps a series of small satisfactions scattered like sequins over the texture of everyday life was of greater worth than the academic satisfaction of owning a collection of fine objects at the back of a drawer.”

Josephine Tey, The Daughter of Time

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

i've been rereading josephine tey (i like to do a bi-yearly reread of brat farrar to shore up the scaffold of my mental health) and i was wondering if you had any thoughts on to love and be wise? it strikes me as a sort of matched pair to brat, but in the opposite direction: a quiet, slightly unsettling young man comes to a nice quiet part of the english countryside and shakes the local equilibrium, but this time for more mysterious and ultimately ulterior motives (and of course we are not let inside leslie serle's head like we are with brat)

This is such an interesting reading, Anon! I hadn't previously thought about To Love and Be Wise and Brat Farrar as paired narratives, but I absolutely agree with you about the parallels! In fact, I'm not sure I would argue for as strong a difference as you seem to suggest.

One of the most interesting things in Brat Farrar, to me (and one of the reasons it's a favorite of mine as well) is how much not just questions of guilt, but questions of identity, come down to the judgment of the community. [This commentary will remain spoiler-free in hopes of luring more people into reading Tey.] Also, as in To Love and Be Wise, we get a late-chapter reveal of backstory; though of course we know much more about Brat at the beginning through his conversations with Alec. I am fascinated by this reading you bring up, because I think it opens interesting questions about how we might query responses to Brat and Leslie. Marta calls Leslie "something very wicked in ancient Greece" after meeting him briefly, as a rather shy but beautiful young man at a party. Brat--also a rather shy but beautiful young man--seems to be accepted as a Nice Boy by most people, despite a past as peripatetic and obscure as Leslie's. I am obsessed with this, thank you.

#josephine tey#to love and be wise#brat farrar#my detection obsession#asks and answers#everyone read brat farrar and then demand a bbc limited series along with me

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

As [Inspector Alan Grant] drew his foot from the painty clasp of his assistant, he said, 'I might tell you that you are conniving at a felony. This is house-breaking and entirely illegal.'

'It is the happiest moment of my life,' the artist said. 'I have always wanted to break the law, but a way has never been vouchsafed me. And now to do it in the company of a policeman is joy that I did not anticipate my life would ever provide.'

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

May Book Reviews: Miss Pym Disposes by Josephine Tey

Back again reading through Josephine Tey's backlist. Middle-aged Lucy Pym is invited back to her old school to give a talk on Psychology. She's enjoying being the feted guest and immersing herself in the petty drama and rivalries of a girls' school when a sudden tragedy strikes...

This is a book that's posing as a golden age mystery novel, but it isn't really. The inciting tragedy only happens near the end of the book, and Tey is much more interested in exploring the psychology and social dynamics of the school than setting up a mystery. A study in human nature and the purpose of justice, beautifully executed. Unfortunately, Tey is one of the more distastefully bigoted of the Golden Age writers, and it shows particularly here. She seems determined to collect all the -isms. Notable for some especially disgusting comments about the Irish.

If you're a particular fan of older mystery novels or books written in-period, you may want to check this book out. Otherwise, I think the casual reader would probably want to steer a wide berth around this one.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

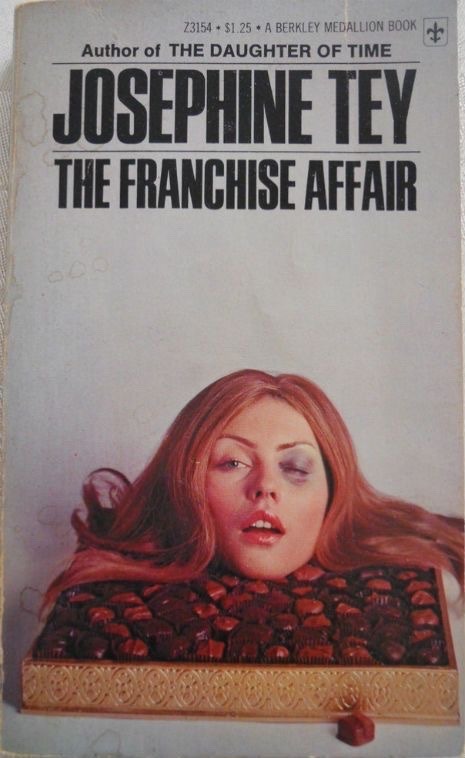

The Franchise Affair by Josephine Tey

Rating: ❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm reading my first Josephine Tey novel, A Shilling for Candles, and I have a whole list of things to do today that are not getting done because I can't put the damn thing down.

@oldshrewsburyian, I blame you for this entirely. Thank you.

#book recommendations#Josephine Tey#mystery novels#am I going to binge read everything Tey has ever written?#yes

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life Lessons From Josephine Tey

A. Painters infallibly capture the character of their subjects.

B. Slate-blue eyes mean you're a slut.

C. Being born in Ireland can turn even a fetus of solid English stock into a chronic fuckup.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“My admiration for both of these eminent writers developed in isolation of one another — but I have always unconsciously identified them as the same sort of writer, and indeed, the same sort of person. There are various superficial similarities: the TB diagnosis that prevented both of them from joining the armed forces, the foreign birth, the rampant womanising, the shared hatred of fascism and suspicion of communism. Much more importantly, they seemed to share the same outlook. Both of these writers took the view that truthfulness was more important than ideological allegiance and metaphysics, that the facts should be derived from the real world, rather than the world of ideas. They were similar stylistically too: both wrote candidly, clearly and prolifically.

(…)

Both Camus and Orwell are rightly credited with being “antitotalitarian” writers. And yet their reasons for being so are not wholly political. They were antitotalitarian not just because they opposed totalitarian regimes, but because they both understood that the totalitarian mindset requires you accept that truth comes from ideology. If the ideas say something is true, it becomes true, and is true. For Fascists and Communists, ideology is not merely a set of values or beliefs, but a cohesive explanation of the past, present and future of mankind. This is what Camus referred to in The Rebel as the desire “to make the earth a kingdom where man is God”. Orwell and Camus both understood the dangers of such thinking, and sought to repudiate it in their work.

Ironically enough, neither Orwell nor Camus really believed in objective truth. Orwell, despite being a champion of free expression and the speaking of truth to power, acknowledged that “objective truth” itself was an “illusion”, albeit a beneficial and “powerful” one. Equally, Orwell remarked that totalitarian ideology “demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth”. The key word here is “disbelief”. For Orwell, truth was more of a commitment to reality than a philosophical framework for deciding true from false. Indeed, perhaps this is why in Nineteen Eighty-Four, all Winston’s attempts to formulate a definition of truth ultimately fail. But this is precisely the point. Orwell understood that truth was a mentality, not a formula.

For Camus, the story was the same. In his Nobel Prize banquet speech, he said the following:

Truth is mysterious, elusive, always to be conquered. Liberty is dangerous, as hard to live with as it is elating. We must march toward these two goals, painfully but resolutely, certain in advance of our failings on so long a road.

His conception of truth was the same as Orwell’s. For Camus, truth was an unreachable summit, but one worth climbing for. Truth, for Orwell and Camus, was a destination towards which it was better to travel hopefully than to arrive.

(…)

It seems that this anxiety Orwell and Camus had about the truth is as prescient today as it was in 1945. But it raises an important question: how can an individual think truthfully in a world dominated by untruthful narratives?

Towards the end of his novel La Chute, Camus’ narrator ponders this question:

Don’t lies eventually lead to the truth? […] Sometimes it is easier to see clearly into the liar than into the man who tells the truth. Truth, like light, blinds. Falsehood on the contrary, is a beautiful twilight that enhances every object.

Here Camus struck a critical distinction, not just between truth and untruth, but between ways of thinking about the problem. While he embraced the fact that truth can never be fully or directly known, Camus conceptualised truth as an internal struggle, against the need for the absolute certainty provided by the “beautiful twilight” of falsehood. Ironically enough, then, Camus’ idea of real truthfulness lay in uncertainty, and in diligently maintaining an awareness of that fact. In other words, truthfulness means thinking in good faith, in honest suspicion of even the most appealing of narratives.

Orwell’s work seems to proffer a similar conclusion. In Nineteen Eighty-Four Winston takes solace in the idea of an internal self-awareness.

He was a lonely ghost uttering a truth that nobody would ever hear. But so long as he uttered it, in some obscure way the continuity was not broken. It was not by making yourself heard but by staying sane that you carried on the human heritage.

Orwell – ever the protestant humanist – placed a great deal of faith in the idea of the sceptical conscience. In the world of the novel, “staying sane” meant remaining critical, even if only in secret. It isn’t Winston’s ability to say two and two make four that allows him to rebel: it’s because despite the universally believed falsehoods purveyed by the state, Winston continues to think diligently and honestly.

For both of these writers, the truth was less a metaphysical question than an attitude. Their novels revolve around the quotidian, everyday experience of the world, in things rather than in ideas. They were both much more concerned with the facts that could be taken from experience than those that could be thought up through ideology. This was the attitude that sustained them throughout their intellectual lives, and united them as figures. And it’s for this reason that I like to think of them as friends, although their paths never crossed.”

“If you have enough power, you can make people believe things which are not true. And your lies may last for centuries, or even forever.

Yet it need not be so. One dark winter’s afternoon, long ago, in the age of steam trains and suet puddings, one of my prep-school teachers (I think it must have been the fearsome Mr Witherington, withering by nature as well as by name) pressed into my hand a small green book which would turn my whole world upside down.

‘Read this,’ he said. ‘It will teach you to understand history as it really is.’

The book is called The Daughter Of Time by Josephine Tey, herself a rather mysterious woman about whom we know astonishingly little.

The title is a reference to Sir Francis Bacon’s remark that ‘Truth is the daughter of time, not of authority’, which should be better known.

It is in a way the single greatest detective story ever written. Those who know of it belong to a considerable secret society, which is still far too small, of lucky people. Those who have not yet read it have a great treat, and a great shock, in store.

(…)

I won’t repeat the piece-by-piece demolition of the case against Richard, and the growing mountain of evidence against his sly successor, Henry VII, which piles up as the case proceeds. I am rather hoping that some of you will get hold of The Daughter Of Time and read it yourselves, and do not want to spoil it for you.

For there is a much deeper point to all this. We all take far too much on trust.

(…)

And once you know all this, you feel, at least I feel, the unending urge to question any commonly accepted idea about the past or the present.

Whether it is the Covid panic (wildly out of proportion), who really won the American War of Independence (the French), the true nature of the ‘Good Friday’ Agreement (a vast surrender to terror under American pressure) or the current conflict in Ukraine (some other time), I now always remember the defamation of Richard III, and rebel against any view which is held by everybody.

Sometimes, it is true, everyone is right.

(…)

But look deep into most of the other things you believe and you will find that it was not quite like that, and in some cases was wholly unlike what you have been led, all your life, to believe.

(…)

You see, it never stops, and it never will, so the rest of us must never stop questioning what we are told.

Thank you, Mr Witherington.”

“Regular readers here will know of my great liking for the detective stories of Josephine Tey, and above all for her masterpiece ‘The Daughter of Time’. I’m always amazed that so many people have never heard of Josephine Tey or of this extraordinary, life-changing book. So it seemed to be a good choice for a programme where two guests, and the presenter Harriett Gilbert (herself a member of a distinguished literary family) try to persuade each other of the virtues of books they like.

I found myself describing ‘The Daughter of Time’ as ‘one of the most important books ever written’. The words came unbidden to my tongue, but I don’t, on reflection retreat from them. Josephine Tey’s clarity of mind, and her loathing of fakes and of propaganda, are like pure, cold spring water in a weary land. Her story-telling ability is apparently effortless (and therefore you may be sure it was the fruit of great hard work. (As Ernest Hemingway said ‘if it reads easy, that is because it was writ hard’). But what she loves above all is to show that things are very often not what they seem to be, that we are too easily fooled, that ready acceptance of conventional wisdom is not just dangerous, but a result of laziness, incuriosity and of a resistance to reason.

The other two books, well, I’ll leave you to listen, though I would say that ‘A Landing on the Sun’ was to me a very sad and distressing book, and I’d like to know a lot more about how it came to be written. In fact, I suspect that serious biography of Michael Frayn would be very well worth reading. As for ‘What’s my Motivation?’, I didn’t want or expect to enjoy it, yet I did, and I would never have opened it (the awful cover is enough to put most people off) had it not been Harriett Gilbert’s choice.”

#orwell#george orwell#camus#albert camus#hitchens#peter hitchens#josephine tey#daughter of time#truth#belief#ideology#totalitarianism#rebel#1984#liberty#inspector alan grant#a landing on the sun#frayn#michael frayn

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Several miles before Garnie, Grant smelt the sea—that seaweedy smell of the sea on an indented coast. It was strange to smell it so unpreparedly in such unsealike surroundings. It was still more strange to come on it suddenly as a small green pool among the hills. Only the brown surge of the weed along the rocks proclaimed the fact that it was ocean and not moor loch. But as the mail-car swept into Garnie with all the éclat of the most important thing in twenty-four hours, the long line of Garnie sands lay bare in the evening light, a violet sea creaming gently on their silver placidity. The car decanted him at the flagged doorway of his hostelry, but, hungry as he was, he lingered in the door to watch the light die beyond the flat purple outline of the islands to the west. The stillness was full of the clear, far-away sounds of the evening. The air smelt of peat smoke and the sea. The first lights of the village shone daffodil-clear here and there. The sea grew lavender, and the sands became a pale shimmer in the dusk.

Josephine Tey, The Man in the Queue

#Scotland#coast#sunset#my favorite bit of the writing#this one didn't have any morally upsetting issues but still wasn't satisfied with the ending#it wasn't something the reader could have solved#Josephine Tey#quote#i liked the descriptive parts once Grant goes out to Scotland but overall this one is just okay

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mark Smith’s illustrations for Josephine Tey’sThe Singing Sands.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can’t believe Josephine Tey cancelled Thomas More in 1951

#this is so funny I’m sorry#thomas more#josephine tey#the daughter of time#history#(sorta)#bern speaks

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Daughter of Time by Josephine Tey

The Mentalist: "My Blue Heaven"

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shroud Of Darkness

A review of Shroud of Darkness by E C R Lorac – 240318

The fortieth in Lorac’s long-running Robert Macdonald series, originally published in 1954, is as much a thriller as a murder mystery with a tale that involves the settling of scores that have lingered on from the Second World War. Sarah Dillon is travelling by train from Exeter to Paddington and is enjoying the company of a young man,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Title: The Man in the Queue | Author: Josephine Tey | Publisher: Touchstone (2013)

1 note

·

View note