#land rights

Link

“When the Brazilian state of Amazonas put the responsibility of protecting one of the world’s largest freshwater fish in the hands of the indigenous inhabitants, it saved the beast from an inevitable extinction.

The giant arapaima, a piranha-proof river monster capable of growing to 10-feet in length and weighing 440 pounds, was almost wiped out by illegal fishing in the 1990s, but two decades of conservation means the ‘Terminator of the River’ is back...

Regardless of their danger, they are also known by the name ‘Cod of the Amazon’, and disregarding a ban on arapaima fishing, their numbers have been plummeting due to the demand for the firm white meat with few bones.

The arapaima disappeared from much of its historic range, and at the dawn of the new millennium, fewer than 3,000 were estimated to exist.

Taking a different model to most conservation methods in the Amazon, João Campos-Silva, an ecologist at the Institutio Juruá, decided to work with local communities to preserve arapaima fishing, and to help people realize the kind of money they could make by protecting the environment.

“Conservation should mean a better life for locals,” Campos-Silva told CNN. “So in this case conservation started to make sense. Now local people say ‘we need to protect the environment, we need to protect nature, because more biodiversity means a better life...'”

According to Campos-Silva, there are now 330,000 arapaima living in 1,358 lakes in 35 managed areas, with over 400 communities involved in managing them. The income generated from fishing rights is pouring into those communities, who are using it to fund medical infrastructure, schools, and more.” -via Good News Network, 10/26/21

#amazon#brazil#indigenous#indigenous people#land rights#fishing#commercial fishing#arapaima#conservation#good news#hope

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

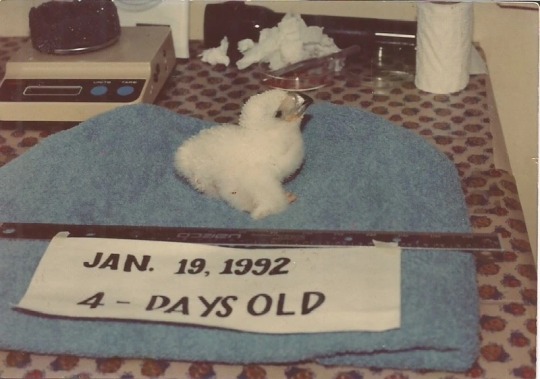

Pag-asa, the famed Philippine eagle, at four days old in 1992 (left) and his daughter, Mabuhay, at five days old in 2013 (right).

Both eagles were born into captivity in Davao City, Mindanao under the care of the Philippine Eagle Foundation. The Philippine eagle is a critically endangered species of eagle endemic to the Philippines with an estimated only 400 breeding pairs left in the wild. Multiple industries leading to the deforestation and destruction of the environment such as large-scale mining and logging have persisted in Mindanao for decades, affecting not only the ancestral lands of the people living in such areas but also its native animals.

In 2022, the Philippines was recognized as “still” being the deadliest country in Asia for environmentalists and land activists.

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invasion Day, Naarm/Melbourne 2024

31 notes

·

View notes

Link

More than five centuries after it was formulated in a series of papal decrees, the Vatican issued a formal announcement on March 30 repudiating the Euro-supremacist “Doctrine of Discovery.” In essence, the “doctrine” said that all lands not occupied by “Christians” passed into the hands of the European conquerors as soon as they were “discovered,” and their inhabitants enslaved.

Composed of decrees issued between 1452 and 1497, it served as the quasi-legal justification for the expropriation of entire continents in the name of spreading the Catholic faith. The repudiation by the Pope is the culmination of decades of struggle by Indigenous peoples in the United States, Canada and around the world demanding its withdrawal.

But while the Pope has now renounced it, the U.S. Supreme Court has not. The high court continues to treat the “doctrine” as an integral basis of U.S. law, particularly in regard to the rights — or lack thereof — of Native peoples.

Most notable in recent times was a 2005 decision authored by the late liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg which invoked the “Doctrine of Discovery” in her majority ruling against the Oneida Indian Nation. The Oneidas were seeking to recover lands and rights in central New York State guaranteed to them under the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua treaty with the U.S., signed by George Washington, then president.

The Oneidas, one of the six nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy were awarded 300,000 acres “in perpetuity” by the treaty. By the 20th century, nearly all of that land had been taken over. In the 1970s, the Oneidas began buying small parcels on what had been their reservation land, including in the small city of Sherill, New York. They objected to the demand by the city that they pay property taxes on the basis that they were a sovereign nation. While the Oneidas won in lower federal courts, the Supreme Court ruled against them 8-1, with Ginsburg authoring the decision:

“Under the Doctrine of Discovery, title to the land occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign – first the discovering European nation and later the original states and the United States . . .

“Given the longstanding non-Indian character of the area and its inhabitants, the regulatory authority constantly exercised by New York State and its counties and towns, and the Oneidas’ long delay in seeking judicial relief against parties other than the United States, we hold that the tribe cannot unilaterally revive its ancient sovereignty, in whole or in part, over the parcels at issue.”

In 2020, the Supreme Court by a 5-4 vote upheld the right of Native nations to reservations that would have included nearly half of Oklahoma. While this was a victory for a coalition of Native nations, right-wing justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion upholding the government’s power to deny the right of self-determination to Indian peoples.

“Once a reservation is established, it retains that status until Congress explicitly indicates otherwise,” wrote Gorsuch. “Only Congress can alter the terms of an Indian treaty by diminishing a reservation, and its intent to do so must be clear and plain.”

How did a loathsome “doctrine” authored in feudal times come to have what liberal and conservative Supreme Court justices alike consider a legitimate basis in U.S. law?

It was the Supreme Court itself that incorporated the “doctrine” into U.S. law, which became foundational in dealing with Native nations, in a key 1823 case, Johnson v. McIntosh.

The decision by Chief Justice John Marshall, declared that, in keeping with the “Doctrine of Discovery,” Native people had only the “right to occupancy” of land and not the right to title or ownership. Only the federal government, Marshall ruled, could own and sell Native lands and that “the principle of discovery gave European nations an absolute right to New World lands”

Following the Vatican’s repudiation, the struggle will intensify for the U.S. government to do the same.

#indigenous peoples struggles#Doctrine of Discovery#Ruth Bader Ginsburg#us supreme court#the vatican#indigenous#genocide#land rights#article#imperialism#us imperialism#colonization#colonialism#age of discovery#history

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nuchatlaht First Nation: How a Legal Battle Could Change Land Rights for Good

Indigenous groups have been fighting for land for decades, often with disappointing results

The Nuchatlaht Nation is seeking declaration of Aboriginal title over a roughly 200 square-kilometre area that includes part of Nootka Island. In 2017, Walter Michael, the late Nuchatlaht Tyee Ha’wilth, or head chief, began the nation’s lawsuit for title and rights recognition at the BC Supreme Court. In a public statement, he relayed a familiar story of how the nation has spent many frustrating years in treaty discussions and other processes, in hopes of protecting its land and people. Michael noted that “successive governments have failed to give Nuchatlaht serious iisaak (respect) for their Rights and Title.” The Nuchatlaht have seen their territory marred by resource extraction that has “adversely impacted Nuchatlaht sacred land and food sources.”

Read more at thewalrus.ca.

Illustration by bailey macabre / Cedar Sage Skoden (cedarsageskoden.com)

#Indigenous#Justice#Land rights#BC#Illustration#March/April 2023#Troy Sebastian#Nupqu ʔa·kǂ am̓#bailey macabre#Cedar Sage Skoden

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

On This Day In History

July 12th, 1971: The Australian Aboriginal Flag is flown for the first time.

#this is a great flag just from a design perspective#history#flag#vexillology#australia#australian history#aboriginal history#land rights

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello, thanks for checking out my blog ^^

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bearing witness to acts of genocide carries certain responsibilities, as does bearing witness to acts of ethnic cleansing. One requires that you not look away, despite the horrors. The other requires you to keep looking — and look deeper — for as long as it takes, because the careful work of ethnic cleansing isn’t always so obvious. It is carried out through laws, bureaucratic as well as physical obstacles meant to keep people from their homes, and sustained violence and dehumanization over a long period of time. Both are part of the Israeli settler colonial project in Palestine, facilitated in full force by the United States government, military and mainstream media.

#palestine#west bank#occupied palestine#colonialism#genocide#ethnic cleansing#settler colonialism#ryah aqel#in these times#r/#land back#settler violence#land rights#masafer yatta#nakba#eyes on Palestine

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

nice fun normal way of saying that rural landowners could murder land activists

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Kenya's government has been ordered by a human rights tribunal to make reparations to the Ogiek, an indigenous, forest-dwelling people who they tried to evict from their lands, marking a huge win for indigenous rights, on a continent where wins are few and normally far between...

These traditional people have been forced in self-defense to enter into a 13-year legal conflict with the Kenyan government, who have engaged in several varied attempts to oust the community entirely from their ancestral lands through eviction notices, physical attacks, forced evictions, and home demolishing.

In court documents uploaded to the internet, the bench unanimously dismissed all the arguments offered by the Kenyan government claiming it was implementing [a previous] 2017 judgment. Then it slapped a reparations fee of just under $500,000 for material damages, and just under $850,000 for moral damages.

In addition, the ruling underlines that the Kenyan government must take all necessary measures, in consultation with the Ogiek community and its representatives, to identify, delimit and grant collective land title to the community and, by law, assure them of unhindered use and enjoyment of their land.

The bench furthermore ordered the Kenyan government to recognize, respect, protect and consult the Ogiek in accordance with their traditions and customs, on all matters concerning development, conservation or investment on their lands.” -via World at Large, 7/4/22

#kenya#ogiek#land rights#reparations#indigenous#indigenous peoples#indigenous sovereignty#africa#conservation#legal action#good news#hope

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazil supreme court rules in favor of Indigenous land rights in historic win

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Oxford Real Farming Conference 2024 (ORFC24)

I have a sort of love-hate relationship with conferences. On the one hand, I always get swept away by the initial rush of excitement: a gathering of people, coming to exchange knowledge around a field we are all passionate about. On the other hand, for someone like me, the reality of conferences tends to be strange, isolating experiences dominated by academic, white, middle-class, cis people who speak a different language, with different values, and operate in a different world to me. Though I enter them full of excitement and curiosity, I usually leave feeling somewhat untethered, overwhelmed by theory and findings but bereft of community and thirsting for actionable, solutions-based approaches. I was delighted, therefore, when ORFC24 opened with a plenary of 10 speakers, all of them landworkers, from around the world, all of whom were extolling - in their own words and ways - action; solidarity; active hope; and calls for food, land, and sea sovereignty. It was clear from the outset this wasn’t going to be the ‘usual’ kind of conference (an abstract exploration of ideas and record of projects past) but a gathering of an international, multilingual, grassroots movement, rooted in an ethics of care and equality; working directly with the land on fairer systems of food and farming.

During the opening Plenary, Charlotte Dufour from Conscious Food Systems Alliance (CoFSA) invited us all - speakers, volunteers, and delegates, in Oxford and online - to take a moment to connect with the land, with one another, and to set an intention for the conference mindfully. In a busy programme of 45 sessions, featuring over 150 speakers and a busy stream of projects, opportunities, and conversations inundating social media, this invitation felt like a precious opportunity to gather focus, mitigate overwhelm, and ground ourselves. Sat at my kitchen table, some 330 miles away from Oxford, I set my intention: to seek out and learn from those at the frontlines of the struggle for Land, Food, and Environmental Justice. It didn’t take long for my intentions to be realised…

In the Thursday lunchtime session Colonised and Coloniser Transforming Relationships through Food and Land Stories Loa Niumeitolu, a displaced Indigenous Tongan, now living and working on Lisjan Ohlone Territory, California and Jessica Milgroom, a descendant of settler families, who grew up on Ojibwe reservation land in Northern Minnesota, held a conversation that aimed to “...break down hierarchies…to ask how we relate… how can we walk forwards together healing the wound of colonisation through food...” (JM). The conversation was one of honouring, compassion and bearing witness. As a white person living in the UK, for me it was also one of humility and unlearning: of coming to understand how our Western food systems are designed, founded and run on the violent displacement of indigenous people; the erasure of indigenous food systems; the severing of indigenous identity and everybody’s connections to the land. In some of her closing remarks Loa Niumeitolu invited the attendees to think differently about our identities and interconnectedness: “The sacred site IS the land… the land is an extension of our bodies… and we are all from indigenous people… we all have great great great grandparents who cared for, and stewarded, and loved the lands that we’re on…”. The session left me thinking about how it is people like myself can find our way back to our indigenous selves, to our ecological identities, and to the essential interbeing with the lands we live on. This conversation, conducted across the divide of coloniser and colonised, offered hope for how stories, conversations, and gatherings may start to unravel the systems of oppression and exploitation that industrial agriculture (aka the food arm of imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy) extends around the world.

On the Friday morning session Building a Global Peasants Movement: 10 Years of Land Workers’ Alliance (LWA) and 30 Years of La Via Campesina (LVC) we heard from Jyoti Fernandes, Morgan Ody, Chukki Nanjundaswamy, and Paula Gioia themselves all land workers, farmers, peasants and indigenous peoples from around the world working both at the grassroots and international levels to oppose the neoliberal programme of WTO whilst also building international food sovereignty and land justice movements. It was a moving and eye-opening session led by women who - though it was never named - are all doing the vital repair work of rematriation.

Chukki Nanjundaswamy (Executive Chairperson of the Karnataka State Farmers Movement and co-coordinator of the All India Coordination Committee of Farmers Movements) traced the history of La Via Campesina (aka “Our Way” in Spanish) from its origins to the movement today which branches almost 100 countries and hundreds of local and national organizations “...fighting all kinds of imperialist and capitalist forces… for the right to food sovereignty”. She described how LVC is organised from the bottom up, constantly learning and evolving from the experiences of its members and other allies including the decision to ensure men and women were represented equally and at all levels of the movement. “LVC is not just about denouncing what we don’t want but also about building hope…across all sectors of society”.

Jyoti Fernandes (Campaigns and Policy Coordinator for the Landworkers’ Alliance) described “the family” of LWA, itself a member of LVC, and her reasons for co-founding LWA in the context of the UK where inequality and access to land have been yolked since the time of the enclosures. She explored the organic origins of the movement from pro-nature, anti-GM protests; to creative expressions of hope, solidarity and resistance; a shared belief in rights for natural home building, self and community sufficiency, and a collective realisation that “...there was this huge network of unorganised people… the neo peasantry returning to the land… and smallholder farmers… all facing evictions … and struggling to survive in the face of the neo-liberal paradigm the UK government was pushing onto farming…”. She described, with infectious joy, how LWA now regularly consult with DEFRA who recognise that LWA’s impetus of “Matching food production with biodiversity and looking after the climate…” is in everybody’s interests.

Paula Gioia (Facilitator of the Smallholder Farmers Constituency in the Civil Society and Indigenous Peoples Mechanism - CSIPM) talked about the intersectional work members of LVC had to undertake to develop a movement of radical change “… to fight against Capitalism and to fight against Patriarchy…this begins with self-reflection: how we reproduce Patriarchy in our daily lives… and this self-reflection begins with space… ” They described the women’s strike at of 1996 in Tlaxcala, Mexico during the 2nd International Conference of LVC in, which challenged the dominance of men, patriarchal ideas and attitudes in the movement whilst demanding; acknowledgement of the role women play in agriculture, farming, and society; 50 - 50 representation of men and women at all levels of LVC; a campaign highlighting and fighting violence against women and; the creation of spaces - now women’s assemblies - necessary for women’s ideas and voices to be supported by, and come forth through the movement.

Morgan Ody (General Coordinator of La Via Campesina, member of Confédération Paysanne and of the coordinating committee of ECVC) wearing the Palestinian keffiyeh around her shoulders spoke with clarity and passion about LVC's global accomplishments:

“… it is still illegal to crop GM crops in Europe, we fought for that… In Columbia, LVC is one of the main guarantors of the Peace Agreement… We have been the first to call for food sovereignty and now everybody is calling for food sovereignty…We have been pioneers of peasant feminism and now peasant feminism is growing everywhere… We have been able to negotiate the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and other people working in rural areas (UNDROP)...” But Morgan’s talk didn’t end in the past, she spoke about how, in the face of multiple overlapping global crises, LVC offers alternative ways of being, of hope, of solidarity now and going forward “...Peasants…and all who are taking care of Mother Earth are the future...”.

She expressed grief and horror at the genocide happening in Palestine and the complicity of governments: “This is not acceptable and as La Via Campesina, we stand against this barbary, we stand for human values, we stand for human dignities, of whoever, of women, of non-binary people, of people whatever their religion or the colour of their skin. We are equal and we are equal in dignity...” This was a powerful reminder that land and environmental justice are inextricably intertwined with social justice and that we are all responsible for decolonising ourselves, for calling out and resisting imperial violence and oppression, wherever it happens in the world. But this session also spoke to how we are all responsible, not just for fighting the old, but also for cultivating the new: through solidarity, active hope, compassion, and creativity. As Morgan said in her closing comments “We are all responsible...for building a culture based on human rights and equality, intentionality, solidarity, and cooperation.”

The session was bookended with calls of “Viva La Via Campesina! Viva!”

In reflecting on these sessions of ORFC24, I started to think that healing is not the same as forgetting, but equally, it is not about flagellating ourselves or one another with past and current traumas - healing comes when we slow down, take time to sit with the pain and discomfort, to listen, learn, notice, and accept. This applies to ourselves, to those we have harmed, and to everyone (humans, land and more than humans alike). What both these sessions taught me is that when we share space and stories, when we listen deeply to one another and bear witness with compassion and empathy, we slowly start to arrive at a new understanding and to do the slow, gentle work of cultivating regenerative cultures based on reciprocity, healing and solidarity.

What I didn’t expect to happen as a consequence of volunteering at ORFC24 was that I would go away from the conference knowing more about myself…As someone who grew up in the English countryside but with no rights to access (we were a poor/working-class family living on a former miner’s terrace, surrounded by Grouse Moors and a large, tenanted estate) my relationship with the land was schismatic: though I felt a deep connection with the fells, moors, and rivers, I was also - according to the farmers, landowners and agents - an outsider. Worse, I was an illegal trespasser. I was surrounded by land which felt like home, like an extension of myself, only greater, deeper, older, more complex, more loving than I could comprehend. And yet, if caught swimming in the tarn, making dens on the fells, walking on the moors, or trudging through the heather, I would - at the very least - be shouted at and oftentimes, be warned away by the crack of shotgun fire. What ORFC24 and the incredible speakers made me realise is something that has taken me 30 years of unlearning to only start to understand: the necessary return to the land, the rediscovery of land-based life, something that I always yearned for but could never allow myself to imagine is not just a fantasy, it is a right. Listening to speakers on colonized lands, to those displaced by colonization and capitalism, to the LWA and LVC, I started to understand the violent inequality at the heart of our UK land and food systems. These speakers helped me see that I have the right to be on and with the land. Because there is no separation between us. I have always known, since I was a child, that myself and the land are one and the same, it was just educated out of me by our systems of inequality, land ownership and education. What the speakers at ORFC have helped me see is that my healing, and the healing of the land, are not separate but wholly, inextricably intertwined.

So now, to begin again, with gratitude and humility… The work of reconnecting and healing all our wounds…

Viva La Via Campesina!

Viva!

Iris Aspinall Priest, Tyne Valley

10.01.23

Word Count: 1985

#equality#solidarity#food sovereignty#LVC#LWA#land rights#indigenous rights#healing#animism#Qi#Nature#Resistance#Dignity#Human rights#traumarecovery#trauma#colonialism#capitalism#right to roam#irispriest

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is an edited and shortened version of an essay I wrote for my Conservation Science & Community class; I decided to post a version publicly because I thought it was interesting and I liked writing it:

The tribes forced west by the conflict with the United States in the early 1800s included the Potawatomi, who would then be established on territory west of the Mississippi (Loerzel, 2021). However, the loss of land would not be forgotten. In the past several years, the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation (this is not the only group of Potawatomi peoples, as there were several different groups within the larger tribe) has been rallying to have land returned (Loerzel, 2021). The Illinois House of Representatives ruled in 2021 that the auctioning off of Chief Shab-eh-nay’s land in 1849 was illegal and supported the Nation’s efforts to regain land, although it seems that receiving federal support is still an ongoing issue (Whitepigeon, 2021a). Approximately 128 acres of land was repurchased by the Nation, which is undergoing federal review to be placed into a trust, under the National Environmental Policy Act (Shabehnay, n.d.). There are no public statements I could find on what would be done with the land; Whitepigeon (2021b) describes the situation as “unclear.” However, the fact that the current lands owned by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation are going under NEPA review suggests a positive direction to me.

What could a tribal park look like in Illinois? Chicago may have a large population of Native Americans, but there are no reservations here. Instead of preserving a traditional, continuous way of life and integrating environmental stewardship, environmental justice for midwestern, urban Native tribes may have to include repatriation of land and teaching traditional ecological knowledge (Turner & Spalding, 2013). Tribal parks differ in some ways from Euro-American views of national parks, with an acceptance of some level of renewable resource extraction, such as power generation or plant gathering (Carroll, 2014). They are similar in that they also champion restoration and conservation, acknowledging humans’ reliance on nature and the necessity of stewardship (Carroll, 2014). Both can also benefit as places for eco-tourism for recreational and educational purposes, although they may have differing levels of access depending on the preferences of the tribe (Carroll, 2014). If tribal land is returned in Illinois, it seems likely that a tribal national park would be established in order to foster education but also to emphasize tribal presence and the wish to remain involved in the stewardship of their former land.

Native Americans did not believe in the European structure of land ownership but were stripped of their sovereignty despite trying to work within the colonizers’ system (Carroll, 2014). In 1849, Chief Shab-eh-nay’s land was illegally auctioned off, against the United States’ own established laws. The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation have been working for 174 years to get this land returned. This is a case where the legality of ownership has been established as rightfully with the Potawatomi, but there are many more tribes from the Chicago region. For many of these tribes, even if land rights were signed away "legally," it is worth considering whether the tribes were under duress and whether Native land repatriation should be more widely considered.

Chief Shab-eh-nay is the namesake of the town of Shabonna, Illinois, where he rode to warn settlers of an attack by the Sauk tribe, as well as Chief Shabbona Forest Preserve and Shabbona Lake State Park (Village of Shabbona, n.d.). This is what the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (2023) says about the history of Shabbona Lake State Park:

“Originally home to tribes of Native Americans, the park derives its name from Chief Shabbona. Pioneer settlement of the area began in the 1830s. From Shabbona Grove, in the southeast corner of the park, homesteaders spread over the region and began farming the rich soil.” (para. 1)

Sources below cut; this includes other source from the sections I removed from the original post, which was posted on my private class webpage.

Carroll, C. (2014). Native enclosures: Tribal national parks and the progressive politics of environmental stewardship in Indian Country. Geoforum, 53, 31-40.

Illinois Department of Natural Resources. (2023). About Shabbona Lake State Recreation Area. https://dnr.illinois.gov/parks/about/park.shabbonalake.html

Kim, J. (2022). Photos: The 69th annual Chicago Powwow. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/visuals/ct-viz-powwow-indigenous-native-firstnations-photo-20221009-p6jyeagqhvaolefgis3xbwqynm-photogallery.html

Loerzel, R. (2021). Why aren’t there any federal Indian reservations in Illinois? WBEZ Chicago. https://www.wbez.org/stories/why-doesnt-illinois-have-any-indian-reservations/a0fe743f-9283-441e-810f-f13fe0dc5344

Mitchell Museum of the American Indian. (2021). Land Acknowledgement. https://mitchellmuseum.org/land-acknowledgement/

Shabehnay. (n.d.). Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. https://www.pbpindiantribe.com/shabehnay/

Turner, N., & Spalding, P. R. (2013). “We might go back to this”; drawing on the past to meet the future in northwestern North American Indigenous communities. Ecology and Society, 18(4).

Village of Shabbona. (n.d.) History of Shabbona. http://shabbona-il.com/history-of-shabbona

Whitepigeon, M. (2021a). Illinois House Resolution Supports the Return of Lands to Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. Native News Online. https://nativenewsonline.net/sovereignty/proposed-to-return-of-illinois-lands-to-prairie-band-potawatomi-nation

Whitepigeon, M. (2021b). Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Seeks Further Support in Reclaiming Illinois Lands. Native News Online. https://nativenewsonline.net/sovereignty/prairie-band-potawatomi-nation-seeks-further-support-in-reclaiming-illinois-lands

#Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation#land rights#environmental justice#to be clear i am not Native; this was for a class#discussing Native groups in our area#the Native groups in Illinois were forced West in the 1800s#i thought that this story was interesting specifically

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Tribal communities face marginalisation and oppression on multiple fronts — in terms of their lands, their forests, their access to basic services, and overall discrimination. However, government policy has not treated any of these as priorities. In the case of forest and land rights, it has been actively undermining the rights of these communities. This needs to stop if genuine development or empowerment is to take place.

Shankar Gopalkrishnan, manager at the tribal interest group Campaign for Survival and Dignity

#Campaign for Survival and Dignity#Shankar Gopalkrishnan#Tribal communities#marginalisation#oppression#discrimination#government policy#land rights#India

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Have Not Signed a Treaty with the United States Government // Chrystos

nor has my father nor his father

nor any grandmothers

We don’t recognize these names on old sorry paper.

Therefore we declare the United States a crazy person

nightmare lousy food ugly clothes bad meat

nobody we know

No one wants to go there. This US is theory illusion

terrible ceremony The United States can’t dance can’t cook

has no children no elders no relatives

They build funny houses no one lives in but

Everything the United States does to everybody is bad

No this US is not a good idea We declare you terminated

You’ve had your fun now go home we’re tired We signed

no treaty WHAT are you still doing here Go somewhere else and

build a McDonald’s We’re going to tear all this ugly mess

down now We revoke your papers

your soap suds your stories are no good

your colors hurt our feet our eyes are sore

our bellies are tied in sour knots Go Away Now

You must be some ghost in the wrong place wrong time

Pack up your toys garbage lies

We who are alive now

Have signed no treaties

Burn down your stuck houses you’re sitting

in a nowhere gray glow Your spell is dead

Go so far away we won’t remember you ever came here

Take these words back with you

#poetry#Chrystos#Indigenous poetry#Menominee poetry#poems of protest#poems of rage#Manifest Destiny#funny#McDonald's#American culture#American poetry#broken treaties#treaties#incantation#Land Rights

3 notes

·

View notes