#language revitalisation

Text

While talk of a new golden age of Celtic cinema might be premature, there’s no mistaking an eclectic new wave of projects making an impact elsewhere: cinemas, television and streaming platforms. Lee Haven Jones’ Welsh-language horror movie The Feast (Gwledd, 2021), shortlisted for the Sutherland Award at the 2021 BFI London Film Festival, was released in US cinemas last year. The first Breton-language drama series, Fin Ar Bed (2017-), was a major hit with French audiences. And Alastair Cole’s acclaimed Boat Song (Iorram, 2021), a lyrical portrait of the Gaelic-speaking fishing community in the Outer Hebrides, is the first cinema documentary entirely in Scots Gaelic.

#langblr#multilingualism#language#languages#multilingual#language reclamation#language revitalisation#language revival#minority languages#endangered languages#indigenous languages#irish language#welsh language#Cornish language#breton language#Scottish Gaelic#c

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

わかはる っちゅんちゃーぬ くゎい HIGA Summit 2023 Part 5♪若者のための会「HIGA Summit 2023」Part 5♩

うちなーぐちぐゆみ6月27日(うらんだぐゆみ2023年8月13日

Part 1🌝 Part 2🌝 Part 3🌝 Part 4🌝

はい!ちゅーや、SNSちかてぃ 言語復興ひちょーる しんかんちゃーが 発表ひち くぃみそーちゃん。

—

はい!今日は、SNSを使って言語継承している参加者が発表してくれました。

👄メキシコぬ なーかぬ くとぅば(なーや ぬーがやたら わしたん😢)

っちゅえー、メキシコぬ どぅーぬ くとぅばさーに オンラインとぅか かび媒体ぬ 雑誌 かちょーんり。

—

👄メキシコにある言語(何と言う言語だったか忘れた😢)

一人は、メキシコにある言語で、オンライン雑誌・紙媒体の雑誌を書いているって。

👄メキシコぬ なーかぬ ナワトルぐち

どぅーぬ くとぅばぬ ならーするたみなかい、動画ちゅくてぃ YouTuberひちょーんり。

—

👄メキシコにあるナワトル語

ナワトル語を教えるために動画を作って、YouTuberをしているって。

👄オクシタンぐちぬ ニサールぐち

くぬ っちょーん YouTuberひちょーんり。

オクシタヌん しまじまとーてぃ しまくとぅば まんどーんり。やくとぅ、しまくとぅば てーしにさんでーならん。かんなじ 標準化すしやか、しまくとぅばん りっぱんぐゎー ちてーてぃ いきわるやるり はなし ひちょーん。どぅーぬ YouTubeとーてぃ、ないる うっぴ 地域差に ちーてぃん 紹介ひちょーんり。

わんにん、あんり うむいびーん。うちなーとーてぃん かんなじ 「まじぇー 標準語 かんげーてぃ・ちゅくてぃ いかんでーならん。」とぅかぬ はなし あいびーしが、うれー いっぺー もったいないり うむいびーん。

うりしーねー、わん ��まりじまぬ くとぅばー ちゃー ないびーが。また 少数言語ぬ なーか とーてぃ、うりがるまし・ありがるましるる ハイラキー ちゅくいる くとぅ ないびらんがやーり しわ ひちょーびーん。

うりやか、ならーするとぅきん ありくり 紹介さーに、びんちょーひちょーる っちゅが どぅーぬ しーぶーはる くとぅば いらびらりーがる ましり うむいびーん。。。

—

👄オクシタン語に属するニサール語

この方もYouTuberだそう。

オクシタンの地域では、地域によってたくさんの異なる言葉がはなされているそう。なので、地域差も大切にしないといけない。必ずしも標準化するというよりは、地域差もきちんと伝えていくべきだと話していた。自身のYouTubeでは、できるだけ地域差も紹介しているそう。

私もそう思います。沖縄でも必ず「まずは標準語を考えようとか、作っていかないといけない。」みたいな話があるけど、もったいないと思う。

そうすると、私の出身地の言葉はどうなるのかね。また少数言語の中で、それがいい・あれが良いみたいな言葉のハイラキーが作られるんじゃないか心配している。

それよりも、教えるときにあれこれ紹介して、学習者が自分で習ってみたい言葉を選択できるようにすることが大切じゃないかなと思う。

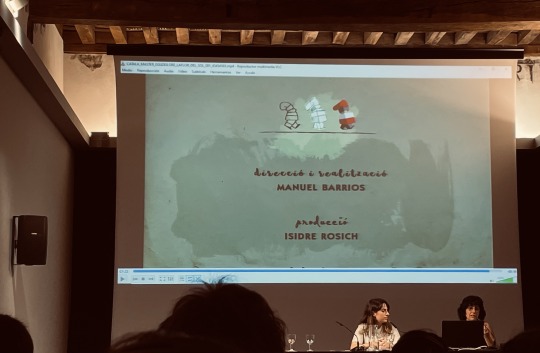

アニメーションとぅ ちかてぃ ちゅくとーる 教材に ちーてぃ 説明し くぃみそーちゃん。UNESCOとぅ かかわいぬ ある 大学ぬ しんしー やいびーんり。

すーみ あいねー、くまから んーだりーびーんどー!

El sol i la lluna

—

アニメーションを使った教材の作り方について説明してくれました。UNESCOと関わりのある大学教授だそうです。

興味がある方は、こちらから見れますよー!

El sol i la lluna

HIGAサミットが はじまる めーに、宿題 たーち わたさってぃ、民話 どぅーぬ くとぅばんけー のーさんでーならんたん。

あんさーに、うぬ 民話 レコーディングスタジオとーてぃ どぅーぬ くとぅばさーに 録音 さびたん。

—

HIGAサミットが始まる前に、宿題が2つ出されて、民話を自分の言語に翻訳するものでした。

翻訳した民話をレコーディングスタジオで録音しました。

くれー わん グループ やいびーん。

わったーや ゆったい やいびーたん。しんかー、アンギカぐちぬ っちゅ、ブレイスぐちぬ っちゅ、タマジクトぐちぬ っちゅ やたん。

あちゃ わんが グループ 代表とぅさーに 発表さんでー ならんくとぅ、ちむわさわさー ひちょーん💦

—

これは私のグループです。

私たちは4人でした。アンギカ語話者、ブレイス語話者、タマジクト話者でした。

明日私が発表しないとグループ代表で発表しないといけなかったので、そわそわ緊張しています💦

くゎっちー さびら!

—

いただきます!

くぬっちゅたーや フェミニスト やんり。やしが、過激派あらんよーく うむっさる てーふぁー フェミニスト やんり いちょーたん😆

--

この人たちはフェミニストだそうです。でも、過激派ではなく、面白いフェミニストだよと言っていました😆

うわてぃん、 んなさーに パブ ぅんじ ちゃー ぬだい ゆんたくさいぬ くりけーしげーし やいびーたん。うむっさいびーしが、んな 寝不足なとーびーん💦

—

終わってからも、みんなでパブに行って、飲んだりおしゃべりしたりを繰り返しました。楽しいですが、みんな寝不足に💦

#うちなーぐち#Uchinaaguchi#HIGA Summit 2023#Basque Country#Vitoria-Gasteiz#Language revitalisation#言語復興#言語継承#しまくとぅば#うちなーぐち復興#少数言語#ゆんたく

1 note

·

View note

Text

they should invent a gaeltacht that is easy and convenient for a disabled non-driver to travel to

#contemplating travel to donegal again and wishing i had a goddamn charioteer#also remembering how wildly inaccessible most gaeltacht courses seem to be#bc apparently none of them were set up for people with mobility impairments#let alone dietary restrictions and the inability to drive#:'(#i mean revitalise irish and grow the gaeltachts and support the urban language#and this will fall into place naturally#but in the short term WHOMST will drive me to donegal

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm making my opposition to the proposal to severely reduce language provision at the University of Aberdeen known - Scottish Gaelic, an endangered Celtic langauge, is one of the languages at risk of being cut. This would do immense damage to the language revitalisation effort. @uniofaberdeen must reverse this decision and commit to protecting Gaelic and other languages in their institution.

If you feel the same way, you're encouraged to make more posts and stories about the issue to show the University of Aberdeen just how much this decision is frowned upon. Use the hashtag #saveuoalanguages in your posts to get the word out about this.

I'll be travelling tomorrow and wish I could do more right now. But together we can make it known just how unpopular this decision is.

#university of Aberdeen#saveuoalanguages#scottish gaelic#gaidhlig#endangered languages#celtic languages#celtic#gaelic#scotland#scottish#language revitalization#cymblr#celtic studies

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

It became an odd habit.

“Will you accompany me, Harry?”

Harry was well past the point of complaining. Whenever Riddle appeared out of nowhere and knocked on his door, there was little he could say or do to get him to leave.

“Oh, do I have a choice this time?”

He didn’t laugh, per se, but the slight tilt of Riddle’s head and the suspicious gleam in his eyes were as loud as one. He held out his hand, palm up, in answer.

Harry refused the offer with a shake of his head and sighed, “Lead the way, I guess.”

They never apparated to the same place twice. Their surroundings were always unfamiliar and remote and never inspired much confidence in the possibility of Harry returning home safely. But he always did. Riddle made sure of that.

Sometimes Harry wondered if this was his weird way of letting off steam, as though their time together somehow relaxed and revitalised him. It was an insane thought, but the fact remained that Riddle would show up tense and barely controlled and one careless word away from a fight, and he would leave loose-limbed and satisfied. Usually at the expense of Harry.

This time was no different. Riddle’s fist was white-knuckle tight, and the location was a drab and dreary abandoned manor of some kind. Walls of crumbling stone and floorboards rotted nearly through, making each step taken a delicate dance. The dust in the air was enough to make Harry cough once or twice; the building had clearly been neglected for a long while.

“What is it today,” Harry asked. “Another potion? More rune work? If you try to teach me a dead language again, I will kick you in the shin and finally make good on my threats of moving to a different country.”

Riddle glanced back over his shoulder and raised a single brow. “Do you truly think distance will stop me?” He asked.

No. Harry didn’t even think being universes apart would stop Riddle.

Still, he scoffed and said, “Creep.”

Riddle simply smiled. “I will not subject myself to that again. You are surprisingly ungrateful for having the honour to learn from a being as powerful as I.”

Harry wanted to roll his eyes, “Yeah. So sorry for not appreciating everything you do for me. Oh, wait—I never asked.”

Riddle hummed, not agreeingly. Never agreeingly. “We will be attempting a discipline you’ve shown great promise in but one we’ve never indulged upon.”

For the life of him, Harry couldn’t think of a single thing in which he showed great promise. He also couldn’t think of a time when Riddle didn’t indulge whenever he damn well pleased. “As vague as ever today,” Harry prodded. “Don’t hold back; share with the class.”

Riddle stopped so suddenly that Harry almost ran straight into him. With a careless wave of his hand, the double doors to their left opened.

And inside was a pristine duelling arena.

Harry’s mouth parted, but he couldn’t find the words. This was damn impressive.

The stone walls were just as decrepit here as they were throughout the manor, but their ruin spoke of wide-cast spellfire and magic dark enough to leave its mark. Of a frazzled mind with enough wherewithal to make it to the duelling room but not enough to cast a protective barrier. It had ample light from shattered windows, but not a single shard of glass could be found across the decorative tiled floor, its pattern still polished to a dull shine.

They walked in - or, rather, Riddle walked in, and Harry followed behind him, content in his rapture. He wouldn’t truly ever get used to wizarding homes and their larger-than-life rooms. Harry would have been none the wiser passing by those double doors; they didn’t look nearly grand enough to hide such a gorgeous arena. But that was magic, he supposed.

It was clear they’d stopped. Harry wasn’t sure how long it had been with as taken as he was by the stage next, admiring its long dark floorboards that came together in a sort of v pattern that repeated. Harry was so hung up on trying to remember the name of it (Houndstooth? Plaid? No, it was something with a C-) that he hadn’t realised just how close Riddle had gotten.

He felt a chill travel up his throat before he processed the movement. Riddle’s hand was just beneath his chin, ice-cold fingers a hair’s breadth away from Harry’s skin. With a muted gasp, he froze and locked eyes with him, which wasn’t very hard to do. Riddle’s were already fixated on him.

Their silence was thick enough to suffocate.

Riddle curled his fingers into his palm slowly and brought his hand to hover just before the round of Harry’s face. He could sense that creeping cold reaching out again with the phantom feeling of Riddle’s knuckles pulling a slow line down his cheek, stopping at the corner of his lips. Riddle moved back then and gestured at them, “Close your mouth, or you’ll catch flies, Harry.”

His teeth made an audible click, the sound making Harry wince when it echoed in the hollow space. To save himself from further embarrassment, he grimaced and blessed Riddle with one of his rarely used meaner smiles, “Come that close to me again, and I’ll bite that finger off.”

Riddle pulled back even slower and tilted his head to the side. He raked his gaze over Harry’s face, down his body, and on his pass back up, he shrugged and said, “Now, now. That’s no way to handle your disputes, is it?”

Like a static shock, Harry finally realised what was happening.

All that anger brewing like a potion in his gut dissipated. His shoulders fell - he wasn’t sure when they’d hiked so far up in the first place - and he huffed out a laugh. “I know what you’re doing,” Harry said.

Riddle looked at him with all the innocence of a Nundu. “Oh? Am I doing something, Harry?” He asked.

Harry breathed through the kindling trying to catch a new spark. “You know what you’re doing,” he started backing away. Riddle’s eyes followed him keenly as his steps took him up the middle of the duelling stage and back down to the other side. He wasn’t running away, just trying to get some distance. “You always know what you’re doing. And I am not falling for it—you won’t manipulate me into this.”

“Surely I’ve no understanding of what you’re implying.” Riddle’s polished shoes tap-tap-tapped their way right after Harry, but he stopped on the stage. He looked down on him from above. “But if I did,” Riddle continued, “I’d tell you you’re only prolonging the inevitable.”

Harry shook his head, this man… “You can’t be serious?”

Riddle folded his hands behind his back. His smile was sharp. “When have I ever been anything but?” He asked, and Harry scoffed.

He wavered for a moment, maybe two, and finally climbed back up the steps to the duelling stage. Riddle, the asshole, looked far too pleased. He turned to face Harry, and they were so close that he only had to look down ever so slightly.

They hadn’t been this close in a long, long time. It was just Harry’s luck that it was happening twice in one day. Fourth Year came to mind as the last time Harry was forced into this proximity. Forced because, unlike now, he hadn’t ever chosen to be in Riddle’s space. Or company. Or attention.

They stood in silence. Riddle’s grin grew teeth with each passing second. Harry knew what he wanted, but he hoped he wouldn’t have to instigate it—invite it any more than he already was.

Then, Harry heard an echo of words, a lost encounter in the back of his memories. It pulled a smile on his lips, smaller than Riddle’s but no less there. “A wizard’s duel, then?” Harry teased. “Wands only — no contact?”

At the sight of Harry’s smile and the sound of his teasing, Riddle’s face fell flat. His eyes narrowed. “Your focus should be here, Harry.” He paused and said, “We wouldn’t want you to get hurt because of some minor distraction. Would we?”

Harry smiled a little wider, “Jealous? How very like you.”

Riddle sneered, “Do not speak of me as though I am predictable.”

Now Harry gave in to the temptation to roll his eyes. They, unfortunately, knew each other very well. Riddle was the most predictable person Harry had ever met, and he knew it—if only because Harry was the most predictable person he had ever met.

“Fine,” Harry conceded. “Ten paces, right?” He turned to begin his count, but Riddle stopped him by the scruff of his shirt.

Non too gently, he yanked Harry back. Cold breath puffed against his ear in semblance of a laugh. “And we bow, Harry,” Riddle murmured, causing a wave of shivers down Harry’s spine.

Harry glared over his shoulder and spat, “Make me.”

#tomarry#tomarrymort#harrymort#my fic#pov: harry#1.5k words#unfinished#i've been writing this for ages and honestly i just want it out of my sight#if anyone likes it please tell me because i'm about to go to the little folder in my brain for it and toss it in the bin

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Accidents Happen.

Pairings: Bucky Barnes x Pregnant!Reader

Warnings: Accidental Pregnancy, Underage sex mention, strong language. abortion mention.

Author's Note: soooooo old. Will eventually redraft :)

Pregnancy, something that Y/N never saw herself having to endure. She knew a lot about it, and the countless classes that becoming an OB-GYN required, had taught her was enough to scare the poor 16-year-old shitless. However, not only the fact that her boobs would fall to her stomach, and her vagina would stretch to accommodate the size of a small watermelon scared Y/N, but also the father of the baby. James Buchanan Barnes, the one Y/N loved to hate.

The two were the best of friends until the year previous when popularity started to come for Bucky. He quickly started trading the many hours they would spend together for underage drinking, and packs of cigarettes. Y/N and their Trio’s third, Steve, were left behind in the dust. Although it was still apparent that Bucky maintained a relationship with one of the two. Y/N suspected that it was her former best friend's new bit on the side that threw a spanner in their works, and how she hated her.

The night before Bucky’s departure. She’d heard of it from Steve. The 107th Infantry Regiment was to recruit a new child soldier the following morning. Y/N gave out her distaste for the war often. Of course, she was worried. Worried for his safety. Despite all that happened, she still desperately cared for the Barnes boy.

It wasn’t until her grandfather’s clock chimed 11pm, and a sharp knock at the door awoke Y/N’s slumber. She wrapped herself in her dressing-gown and ran downstairs. Her parents were out, dancing she presumed, though she wondered why they would want to leave the house whilst it was raining as hard as it was. The visitor knocked again.

It was awkward for him when she opened the door. His teary eyes were hidden by the rain. His clothes stuck to him. He was sure there was a metaphor for his embarrassment somewhere in that. Y/N ushered him inside. Running for a towel to dry him off some. Bucky remembered why he had come. He had come because he knew that when there was nowhere to turn, he would still have her.

It was times like these that he regretted most, losing his best friend.

“Hey Dollface”

The pair spoke until the early hours of the morning. Y/N didn’t forgive Bucky for ditching her for popularity, but she understood why it happened. Puberty was hard on everyone but worse on him. It took him a solid half-hour to explain that.

The grandfather clock in the living room softly chimed 4am, when Bucky and Y/N found themselves in one another’s embrace. On the 3rd little bell, Bucky pulled the girl into a kiss. A long sweaty night of ‘I love you, I’ve always loved you’ ensued, and the two teens found themselves whilst enjoying one another for the first time.

That night became a taboo subject, and although there were confessed feelings on Bucky's part and an all too willing kiss on Y/N’s, the two decided that friendship would be the best way to start their revitalised relationship. Besides, Bucky was to leave the following morning. And so, they carried on about their days as acquaintances, friends at best.

Yet, here she was. Sitting on her living room couch, the very same one they had done the deed on a few months earlier. The brunet sat patiently, confused as to why Y/N had interrupted his story, the one she had practically begged him to tell. Y/N chewed the inside of her cheek

“You gonna tell me or wha-”

“I’m pregnant.” she blurted, a fully brainstormed paragraph was what she’d meant to say, but what just came out was. “It’s yours.”

What felt like hours passed, but in reality was 2 and a half minutes.

The room fell silent, the slight tick of the alarm clock and a chorus of laboured breathing, were the only things heard other than the blood rushing through Bucky’s ears.

“What?” he asked, not entirely sure if he had hallucinated what he had heard.

“I’m pregnant”

“Oh.”

There was nothing else to be said on Y/N’s part, all she wanted to know was how he would react.

“Are you keeping it?”

“I don’t know- I mean- I do. Want to keep it, that is, but. But, if you don’t want me to, I can get an abo-”

“No, You’re not gonna do that.” he interrupted. “Unless you wanted to, I just-”

A tear rolled down Y/N’s cheek, she wiped it away before finally looking at the boy next to her. Bucky was also crying, it wasn’t the first time she had seen him cry but it was different. Salty tears fell from blue eyes onto slightly stubbled skin as he ran a hand through his hair.

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I just want to tell you that the road sign with an out of office message came up in my class. I'm taking a linguistics course about the world's languages, so welsh came up and my professor used the picture of the sign as a fun example of how welsh is doing pretty well (as in it has protective and revitalising language politics) but that lots of people still don't know it. Just thought that you might appreciate to know that the council's mistake made it into academia. (I also had to dig up the post you wrote about it, so have the link)

I have passed this along to my husband and he is DELIGHTED, thank you

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 86: Revival, reggaeton, and rejecting unicorns - Basque interview with Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Revival, reggaeton, and rejecting unicorns - Basque interview with Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez'. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Gretchen McCulloch. I’m here with Dr. Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez who’s an Assistant Professor at California State University, Long Beach, USA, and a native speaker of Basque and Spanish. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about new speakers and language revitalisation. But first, some announcements. Thank you to everyone who helped share Lingthusiasm with a friend or on social media for our seventh anniversary. We still have a few days left to fill out our Lingthusiasm listener’s survey for the year, so follow the link in the description to tell us more about what you’d like to see on the show and do some fun linguistics experiments. This month’s bonus episode was a special anniversary advice episode in which we answered some of your pressing linguistics questions including helping friends become less uptight about language, keeping up with interesting linguistics work from outside the structure of academia, and interacting with youth slang when you’re no longer as much of a youth. Go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm to get access to this bonus advice episode, many more bonus episodes, and to help keep the show running.

[Music]

Gretchen: Hello, Itxaso, welcome to the show!

Itxaso: Hi! It’s so good to be here. I feel so honoured because we use so many of your episodes in our linguistic courses. For me, being here is exciting.

Gretchen: Hello to Itxaso and also to Itxaso’s students who may be listening to this episode.

Itxaso: I dunno if I want them to find this episode, though. [Laughter]

Gretchen: They’re gonna find it. Let’s start with the question that we ask all of our guests, which is, “How did you get interested in linguistics?”

Itxaso: I feel like, for me, it was a little bit accidental – or at least, that’s how you felt at that time. I grew up in a household that we spoke Basque, but my grandparents didn’t speak Basque. My parents spoke it as non-native speakers. They were new speakers. They learnt it in adulthood, and they made me native. But I was told all my life, “You speak weird. You are different. You’re using this and that.” Later on, I was told that, “Oh, you’re so good at English. You should become an English teacher because you can make a lot of money.” And I thought, “Oh, yeah, well, that doesn’t sound bad.” When I went to undergrad, I started taking linguistic courses, and then I went on undergraduate study abroad thanks to a professor that we had at the university, Jon Franco. That’s where I realised, “Wait a minute. All of these things that I’ve been feeling about inadequate, they have an explanation.”

Gretchen: So, people were telling you that your Basque wasn’t good.

Itxaso: Yeah.

Gretchen: Even though you’re the hope and the fruition of all of this Basque language revitalisation. Your parents went to all this effort to learn Basque and teach you Basque, and yet someone’s telling you your Basque is bad.

Itxaso: Absolutely. You know, people wouldn’t tell you straight to your face, “Your Basque is really bad,” but there was all these very subtle ways of feeling about it, or they would correct you, and you were like, “Hmm, why do they correct it when the person next to me is using the same structure, but they don’t get corrected.” As a kid, I was sensitive to that, and then I realised, “Wow, there’re theories about this.”

Gretchen: That’s so exciting. It’s so nice to have “Other people have experienced this thing, and they’ve come up with a name and a label for what’s going on.”

Itxaso: It’s also interesting that as a kid I did also feel a little bit ashamed of my parents, who’re actually doing what language revitalisation wants to be done. You want to become active participants. But I remember when my parents would speak Basque to me, they had a different accent. They had a Spanish accent. I was like, “Ugh, whatever.” Sometimes it would cringe my ears; I have to admit that. As a kid, I was in these two worlds of, okay, I am proud and ashamed at the same time of what is happening.

Gretchen: And the other kids, when you were growing up, they were speaking Basque, too?

Itxaso: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. I grew up in Gernika, right, and we have our own regional variety. I remember on the playground sometimes they would tell me, “Oh, you sound like the kids in the cartoons.”

Gretchen: So, you’re speaking this formal, standard Basque that your parents had learned as second language learners, and the other kids are still speaking the regional variety of Basque but hadn’t gone through the standardisation process and become the one that’s in the media.

Itxaso: Correct. My first variety was actually this standardised variety that nobody spoke when it was created in the ’60s. My parents learnt this in their 20s, and then that’s the variety that I was exposed to at home. But then you go in the street, and they’re like, “Oh, you sound like Doraemon,” because that’s what we watched.

Gretchen: The character in the cartoon, yeah.

Itxaso: Yeah, in the cartoon. It was like, “Oh, okay, do I? All right.” Then I started picking up the regional variety.

Gretchen: Right. You pick up the regional variety as well from the kids. Then what did your parents think of that if they think they’re speaking the fancy one?

Itxaso: Oh, my goodness. It was absolutely hilarious because my mom, she always thought that the Standard Basque is the correct way because that’s the one that you learnt in the school, so she did have this idea that literacy makes this language important. You know, for Basque revitalisation, that’s important. But I remember we were at home, and she would correct me because, for instance, as any spoken language, you would also shorten certain words. She would always say, “Oh, that’s not how you say it. You’re supposed to say this full word. You have to pronounce the entire word.” Then I said, “But Mom, everybody else uses this other variation,” especially with verbs, which are a little bit complicated, right. Then she would say, “Oh, Itxaso, you know what? I gave you this beautiful Basque, and then you went out to the school, and they ruined it all for you.” Then in order to come back, I would tell her, “Mom, but I am the native speaker here.” So, these tensions of who is right.

Gretchen: Who is the real Basque speaker, who is the best Basque speaker, and in this context where, in theory, your goals should be aligned because you’re all trying to revitalise Basque, and in theory, you all have the same goal, and yet, you’re getting criticism from different sides, and people are criticising different groups in this – but in theory, you have the same goals.

Itxaso: I think growing up in this paradox of I’m also criticising my mother, who actually, thanks to her, I get this language. In the revitalisation process, I think this negotiation is fascinating that you’re constantly being exposed to.

Gretchen: Constantly being exposed to all these different language ideologies around what is good, what is not good. You went to university, and you started encountering linguistic words for these experiences that you had. What were some of those words?

Itxaso: Some of these words I remember was this “standard language ideology,” that the idea or, in a way, that the standards are constructs that don’t exist. And I was thinking, “Wait a minute, in my language, we have a very clear standard.” We actually have a name for it. We call it “Unified Basque,” or “Euskara Batua.”

Gretchen: “Batua.”

Itxaso: “Batua” means “unified.” It’s associated with a kind of speaker. These are speakers that, like my parents, learned Basque through the schooling system, which today is actually the majority of the Basque-speaking population, at least on the Spanish side. “Standard language ideology” – I was thinking, “What is that? Oh, okay, it’s the thought that we have that these standards exist. How do I make sense of that?” I remember when I was in college, the term “heritage speaker” was thrown a lot.

Gretchen: “Heritage speaker” of Basque. Are you a “heritage speaker” of Basque?

Itxaso: I don’t consider myself a heritage speaker of Basque because – so I have Basque heritage, yes, and no. My dad’s side of the family is from Spain as well, but they also grew up in the Basque Country. This comes also with the last name. Do I have Basque heritage? Yes. But I think our connections with language are a little bit more complicated than the ethnicity per se. It’s like, we have this saying that says that it is Basque who speaks Basque. That was this poet, Joxean Artze, that we used to hear a lot during the revitalisation process. The question is, “What kind of Basque?”

Gretchen: Yeah, like, “Who is Basque enough to speak Basque?” And your parents speak Basque, but your grandparents didn’t speak Basque anymore, but if you go far enough back in your ancestry, somebody spoke Basque. But who counts –

Itxaso: But – yeah. My grandparents didn’t speak Basque. Their parents – maybe they had some knowledge. I dunno how far along. What we do know is that the region where my grandparents grew up in, Basque was already in the very advanced stages of language shift. Also, my grandparents were born in the civil war, so speaking Basque was probably not – it could get you killed.

Gretchen: Yeah. Which is a great reason to say, “Hey, you know what.”

Itxaso: Right. Then later on, this paradox is coming into play. As a 5-year-old kid, you’re not aware that your grandpa, you know, could have been killed if they spoke our language, but at the same time, my dad’s side of the family also was going through some kind of shame because he learnt the language as an adult, and he became in love with the language. This idea of heritage – do you need to be a heritage to be part of the language? It was a little more complicated than that. When I asked my mom, “Why do you learn the language?”, for her, she was always, “Because my identity now is complete.” But for my dad, it wasn’t the same reason.

Gretchen: Why did you dad learn Basque?

Itxaso: My dad learned Basque because after the dictator died, the revitalisation was very important, and there were a lot of jobs.

Gretchen: Ah, so just economic reasons.

Itxaso: For him, it was pure economics. Then, you know what, if I learn Basque, I’m gonna have more opportunities to have a government job, and a government job is a good job. Then after that, throughout the time, he actually became even more in love with the language, more invested in the revitalisation. He also did a lot of these – bertsolaritza is this oral poetry that we have. It has a very, very long oral tradition in the Basque Country. He read a lot of literature. He taught Basque in the school system. He was also invested in teaching Basque to immigrants as well because he felt like an immigrant himself as well.

Gretchen: And this question of who has Basque heritage, if you’re an immigrant to Basque Country, you are becoming part of that heritage as well.

Itxaso: Yes.

Gretchen: It’s an interesting example of how economic and social and cultural things can really work together for something, like, being able to get a job doing something can allow you to fall in love with it.

Itxaso: Yes, yes.

Gretchen: Or it can be hard to stay in love with something if there’s no way to support yourself while doing it.

Itxaso: Absolutely. I remember that he was always invested in these processes. I have to admit that – now I’m gonna be a little picky again because these ideologies sometimes don’t always fully go – you know, we still have these biases – my dad’s fluency and also competency became stronger and stronger, and then he started to also speak like locals, little by little.

Gretchen: Okay, you know, this standard, unified Basque – he’s like, “Well, maybe I’ll talk like the other local people.”

Itxaso: I remember that my mom was very clear, especially in the beginning – I dunno if she feels that way anymore – that the standard is the correct one. I don’t think my dad did have so many overt ideas about it. For him, in the beginning, it was instrumental, “It’s gonna give me a good job,” and then he fell in love. And then it’s like, “Now, I have to go to the richness” – sometimes he would say that – “of the dialects of the traditions.” But he didn’t have this heritage Basque. He was born in rural Spain, and his parents moved to the Basque Country for economic reasons.

Gretchen: And he sort of fell in love with it anyway. What’s it like for you – because you live in the US now – doing research with Basque and trying to stay in touch with your Basque identity despite not living in the Basque Country?

Itxaso: For me, I have to admit that, again, I came to the United States thinking that I’m going to be an English teacher when I come back. I said, “I’m gonna do my master’s, and then I’m gonna go back to the Basque Country, and I’m gonna teach English.” Uh-uh, no.

Gretchen: Okay.

Itxaso: I realised that the farther I am from home, the more I wanted to understand the processes or how I felt as a kid because I realised, “Wait a minute, I can find answers to the shame and pride that I had growing up.” I was also ashamed of my grandparents that they didn’t know Basque because when he would take me to the park, right, I knew that people would talk with him. I would just go, instead of him looking at me whether I am falling off from the swing, I was checking on him to see who was gonna talk with him because I was ready to do the translation work for him.

Gretchen: Oh, okay, if he can’t talk to the other parents or grandparents or whatever, then you’re like, “Oh, here, Grandad, let me translate for you.”

Itxaso: Yep. Then I remember that I’d think, “Hey, I’m teaching him Basque. He’s practicing, right?” Every Sunday he would come, you know, to our hometown and, before going to the park, I made him study Basque. He was so bad at it. Like, terrible at it. It was very hard for him, and he would tell me, “But Itxaso, why are you doing this to me? I didn’t even go to school.” I mean, he didn’t have much schooling even in Spanish. I said, “Don’t worry. If you’re Basque, you have to speak Basque.” Those were some of the – and I was 5 or 6. I was so happy, right. At the same time, I had this very strong attachment to him but also internalised shame that in my family intergenerational transmission was stopped. As a 5-year-old kid, you don’t understand civil war – yet. [Laughter]

Gretchen: I hope not.

Itxaso: When I went to graduate school, I realised, “Wait a minute, my teachers were correcting me all the time.” I had this internalised shame that exercised, right. I was told that sometimes I wasn’t Basque enough; sometimes I was being seen as a real Basque. So, what’s happening? This is when I realised that sociolinguistics, which is the field of study that I do, became very therapeutical to me.

Gretchen: You can work through your issues or your family issues and your language issues by giving them names and connecting them with other people who’ve had similar experiences like, “Oh, I’m not alone in having this shame and these feelings.”

Itxaso: Absolutely. And that there were many of us. There were a lot of Spanish speakers in my classroom who, maybe they didn’t have literacy in Spanish, or they had similar encounters of feelings, and I said, “Wait a minute, so we’re not that weird,” and understanding that, in fact, this is quite common. Or there were also speakers of other language revitalisation contexts that I thought, “Oh, wait a minute, I thought we were this isolate case,” and you’re thinking, “No, we have similar feelings of inadequacy, but at the same time, pride.” I used the world of linguistics in general to understand these patterns and also to heal in some way.

Gretchen: No, it’s important.

Itxaso: I almost had a little bit of a rebel attitude in some ways. For me, it was like, “Ha ha! I got you now!”

Gretchen: Like, “You don’t need to make me feel shame anymore because I have linguistics to fight you with!”

Itxaso: There we go! “And now, I’m gonna go back with my dissertation. I’m gonna make sure that you understand that YOU are the one wrong and not me, and that when you correct me, I am also judging you.”

Gretchen: Does it work very well to show people your dissertation and tell them that they’re wrong?

Itxaso: No. [Laughter] Absolutely not.

Gretchen: I was gonna say, if you said this was working, it’s like, “Wow! You’re the first person that I know who wrote a dissertation and everyone admitted that they were wrong.”

Itxaso: Yeah, but then you have this hope.

Gretchen: Yeah.

Itxaso: Then I realised, okay, well, this is my therapeutic portfolio, basically.

Gretchen: At least you know in your heart that you are valid. So, you don’t like the word “heritage speaker,” which I think “heritage speaker” does work for – we don’t wanna say, “No one is a heritage speaker” – but for you in your context, that doesn’t feel like it resonates with you. What is a term that resonates with you for your context?

Itxaso: For me, it resonates more – I consider myself a native speaker of Basque, or my first language is definitely Basque. We have a term for that in the Basque Country, “euskaldun zahar,” and it literally means – “euskal” means “Basque,” “dun” means that you have it, and “zahar” means “old.”

Gretchen: You have the “Old Basque.”

Itxaso: Yeah, you have the Old Basque, which is associated with the dialects or the regional varieties. It has nothing to do with age.

Gretchen: Okay. You’re not an old Basque speaker as in you’re a senior citizen with grey hair, you’re a speaker of Old Basque.”

Itxaso: Mm-hmm.

Gretchen: Compared to a “New Basque” speaker?

Itxaso: There we go. Mm-hmm. A New Basque speaker, right, which we also have a Basque term for that, right, it actually means that you started it in more new times, which for us is associated with the revitalisation.

Gretchen: That’s like your parents.

Itxaso: Exactly. My parents consider themselves “new” speakers of Basque, and the Basque word for that is “euskaldun berri.”

Gretchen: “euskaldun berri.” So, this is “speaker of New Basque” or – and the idea of someone being a new speaker of a revitalised language in general where you learned it in adulthood and maybe you’re trying to pass it onto your kids and give them the opportunities they didn’t have, but you have these challenges that are unique to new speakers.

Itxaso: Absolutely. And oftentimes has to do with the idea of how authentic you are. This is something that is being negotiated, right – these negotiations we’re having in our household. When my mom said, “I know the correct Basque,” and I would basically implicitly tell her, when I was telling her, “But I know the authentic one.” Because of that, those similarly wider ideologies, right, this is how my parents also, little by little, they were able to sprinkle their Standard Basque with some regional “flavour,” as we call it, right. They would change their verbs, and they would start sounding more like the regional dialects.

Gretchen: Are there different contexts in which people tend to use the Standard Basque versus the older Basque varieties, like either formal or informal contexts, writing, speaking, like, official contexts or intimate contexts? Are there some differences, sociolinguistically, in terms of how they get used?

Itxaso: Yeah. For somebody that, for instance, I consider myself also bi-dialectal in Basque in the sense that I speak the regional variety now even if my first variety was actually the standard. I use the Standard Basque to write. But that is only part of the mess or the beauty or the complexification because those people that started learning Standard Basque in the school, sometimes, they might feel that their standard is too rigid to be able to have these informal conversations. One of the things that a lot of new speakers of Basque are doing is, in fact, creating language.

Gretchen: To create an informal version of the standard. Because it’s one thing to speak it in a classroom or something, but if you’re going to go marry someone and raise children in this and you wanna be able to have arguments or tell someone you love them or this sort of stuff maybe this thing that’s very classroom associated is too fancy-feeling for that context.

Itxaso: The same way that they don’t wanna sound like the kids in the cartoons, like Doraemon, for instance. [Laughter]

Gretchen: That’s not how real people sound.

Itxaso: Knowing that a standard was necessary for our survival, for the language to survive, at least during those times, but at the same time, we need to get out of this rigidity that this standard might give us. The new speakers in many ways are the engineers of the language.

Gretchen: The original creation of Standard Basque in the 1980s was taking from all of these different regional varieties and coming up with a version that could be written, and you could have one Basque curriculum that all of the schools could use rather than each region trying to come up with its own curriculum, which is logistically challenging.

Itxaso: Absolutely. The Standard Basque was created, finally, in 1968, and little by little being introduced in the educational purposes. And the education in the ’80s, too, is when [exploding noise] bilingual schools skyrocketed, and the immersion programme became the most common one.

Gretchen: And this is immersion for kids, for adults, for everybody?

Itxaso: For kids. You start with kindergarten or, I dunno the terms here in the US, but 2- or 3-years-old, all throughout university. Of course, that went through different stages. Of course, there’s some degrees in university that might not be fully taught in Basque, but overall, little by little, I mean, in the past four years, a lot of that has been done.

Gretchen: What’s it like for you now going back to the Basque Country being like, “Wow, revitalisation is done. It’s complete. Everything is accomplished. We have nothing to worry about anymore.” Is this the case?

Itxaso: Absolutely not. There’s still debates going on. One of the big debates that have been talked – so we have sociolinguistic surveys that we wanna measure how successful is this standard, and what does that even mean. All the people who learned Basque in the schools, like my parents, are they actually using the language all the time? Or even if you grew up speaking Basque. The reality is that Basque revitalisation has been very successful in creating bilinguals. Most of the population, if you are 40 or younger – especially here I’m talking about the Basque Country in the Spanish side because the French side does not have the same governmental support that we do. The answer is that some surveys show that Basque is not as spoken as it is acquired.

Gretchen: People learn it in the schools in the immersion programmes, but then, the kids are playing on the playground, maybe they’re not using it as much, or you’re going into a store, and you’re buying some milk or something, and you’re not necessarily using Basque for these day-to-day interactions.

Itxaso: Correct. I remember when I was doing my own fieldwork and collecting data for my dissertation, I remember that I would ask people from the city because this is where the revitalisation was most impactful because this is where Basque was least spoken before the standard was implemented. That was a – oh, my goodness. There is this saying that we have that Basque is being used with children and dogs.

Gretchen: Okay. [Laughter]

Itxaso: And then I started to notice – and, you know, my sister, she uses Basque with her friends, but at home, she would use a lot of Basque with the dog that she got a few years ago. I was so surprised because then our interactions back home become more Spanish-dominant with time. I was like, “Oh, my goodness. Is this true?” I started to notice. In fact, some adults that would talk Basque to their children but also to the dogs, but later on, a lot of the adult interactions.

Gretchen: But then when you grow up, you use Spanish. You have this ideology of “Okay, well, it’s important for children to have Basque, but then you grow up and you put it away,” which doesn’t sound that great.

Itxaso: Meaning that the normalisation of Basque, it hasn’t started.

Gretchen: It has succeeded at some level, yeah.

Itxaso: Absolutely. But the work is not completely done yet. I don’t think it’s ever gonna be – I mean, when I say it’s never gonna done meaning that you always have new processes or new challenges. One thing that I did notice – so the last sociolinguistics survey showed two very interesting trends in the opposite direction. The first one was that new speakers, and especially young new speakers from the city, they’re starting to embrace Basque in their daily life interactions. They’re adopting the language and using it and engineering it and making it more informal. In fact, we have different standard Basques that are starting to emerge in one city, in Bilbao. Another one might be emerging in Vitoria-Gasteiz, which is the capital. And the other one – San Sebastián. There’s still a standard but with some flavours. People are documenting that. The other one is that in certain Basque-speaking regions or traditional speaking regions like my hometown, for instance, that the use of Basque among teenagers has actually dropped a little bit – slightly. I have noticed that, too, when I go back. I was thinking, “Why would that be? Why is it that teenagers might see” –

Gretchen: You have to think that Basque is cool as a teenager.

Itxaso: Exactly. I also noticed different kinds of trends. When I grew up in the ’90s, during my rebel times, we loved punk. We loved rock.

Gretchen: Was there Basque music in rock and punk and this sort of stuff?

Itxaso: Oh, my goodness, Berri Txarrak, which translates to “bad news.”

Gretchen: We should link to some Basque music in the shownotes so people can listen to it if they want.

Itxaso: We loved it. Little by little, more soft rock became more popular. This is still popular. But I noticed in the past five years or so that reggaetón is –

Gretchen: The young people are listening to reggaetón. Is there reggaetón in Basque?

Itxaso: That’s what we need, I think.

Gretchen: Okay. If there’re any reggaetón artists who are listening to this, and you speak Basque, this is your project.

Itxaso: I’m like – maybe there is. I’m not a big fan of reggaetón.

Gretchen: But it’s what the young people want. It’s not about you anymore.

Itxaso: Exactly. I do wanna hear some Basque – I know there is feminist reggaetón, but I haven’t heard Basque reggaetón as much.

Gretchen: Maybe someone will tell us about it.

Itxaso: Maybe it’s time to adjust to –

Gretchen: And to keep adapting because it’s not just like, “Oh, we have this one vision of what Basque culture looked like in the past, and you have to be connected to that thing specifically,” it’s that it evolves because it’s a living culture with what else is going on in the world.

Itxaso: Absolutely. This is where the making of what it means to be a speaker of a minority language also comes into play. I know that in many Indigenous language revitalisation processes hip hop music has been extremely important in the process of language revitalisation. Maybe we do need some Basque reggaetón.

Gretchen: All right. Sounds good. I’m sold. Basque is famous among linguists as being a language that’s spoken in Europe but that’s not ancestrally related to any of the other Indo-European languages. This makes it famous, but also, I dunno, how does this make you feel?

Itxaso: Aye yae yae yae yae. It makes me feel good and bad at the same time because it’s like, “Oh, you know about Basque? That’s awesome!”, but then, “Oh, we’re being told that this is what you know about Basque,” which is this “exotic” language, and I’m like, “No, no.” That’s the part that I’m like, “No, we’re normal, too.”

Gretchen: “We’re also just people who’re speaking a language trying to go about our lives.” It also has things that are in common with other language revitalisation contexts – I’m thinking of Gaelic and Irish in Scotland and Ireland and lots of Indigenous language contexts in the Americas, in Australia. There’s so many different places where there’s a language that’s been oppressed, and it’s hard to say what is Indigenous in the Spain-France context, but definitely big governments have said, “Oh, you should all be speaking Spanish,” “You should all be speaking French,” and you have to struggle to make this something that is recognised and funded and important and prestigious and all of this stuff.

Itxaso: Absolutely. And for the first time in the history of the Basque language, now we are considered a “modern” language – another stereotype that oftentimes – “Oh, you are such an old language!” And I’m thinking, “But we speak it today.”

Gretchen: It’s not only ancient speakers. There’s still modern people speaking Basque.

Itxaso: Yes, and we have a future. We can do Twitter. We can do Facebook. We can do social media.

Gretchen: You can do Reggaetón.

Itxaso: Reggaetón in Basque. We can do a lot of things in Basque. People associate us oftentimes with these ancient times from the lands of the Pyrenees and caves. I’m like, “Great.”

Gretchen: But you’re not living in caves now.

Itxaso: Exactly. And when they tell us, “Oh, you are this unique language and so weird,” and I’m like, “We’re not weird. We’re unique like any other language, but we also have similar processes.”

Gretchen: Ultimately, every language is descended from – like, languages are always created in contact with other people, so there’s this ancestral descendant from whatever people were speaking 100,000 years ago that we have no records of. Everything is ultimately connected to all of the other humans, even if we aren’t capable of currently tracing those relationships with what we have access to right now.

Itxaso: Even within among linguists, right, it has been debated – Basque has been compared to possibly every language family out there. Even Basque people, “Oh, we found a connection! Maybe we are connected to the languages of the Caucasus.” All Basque linguists just roll their eyes thinking, “Here we go again.”

Gretchen: “Here’s another one.”

Itxaso: This idea of also looking at the past has been very important to understand our existence, but also it’s important to understand that we have a future, and that one is going to form the other in many ways. When they say, “Oh, where is Basque coming from?”, I’m like, “I dunno if we’re ever gonna find that out.”

Gretchen: I dunno if that’s the most interesting question that we could be asking because it’s hard to have fossils of a language. Writing systems only go back so far, and the languages being spoken and signed much, much earlier than that, we just don’t know because they don’t leave physical traces in the air.

Itxaso: What is fascinating is that, so recently, there has been some evidence – they found some remains that, in fact, Basque was written before the standard or before when we thought. Initially, we know that the first Basque writings were names in tombs, in graveyards. Now, we actually have some evidence – or at least they found some evidence – that Basque might have been used for written purposes also and that the Iberian writing system was used for that. They’re still trying to decode.

Gretchen: Maybe we could link to a little bit of what that looks like if there’s some of that online, too.

Itxaso: It looks like a hand. The text looks like a hand, and there’re five words there. They have only been able to decode one word.

Gretchen: But they think that word is Basque?

Itxaso: Yes.

Gretchen: Cool.

Itxaso: We will see. I mean, stay tuned.

Gretchen: Further adventures in Basque archaeology, yeah.

Itxaso: Even for Basque people that is actually really exciting. That’s where the part of like, “Oh, maybe we know where we come from!” We’re like, “We actually come from maybe there,” or I dunno, does that make my dad less Basque for that?

Gretchen: And does that make the new speakers less valid? But it’s still kind of cool to find out about your history.

Itxaso: Yes, and that this history’s so complex. It’s also entrenched in our real life today. It’s still important to us in some ways.

Gretchen: You also co-wrote a paper that I think has a really great title, and I’d love you to tell me about the contents of the paper as well. It has a very interesting topic. It’s called, “Bilingualism with minority languages: Why searching for unicorn language users does not move us forward.” What do you mean by a “unicorn language user”?

Itxaso: Well, first of all, I have to admit that this title was by the first author, Evelina. I mean, amazing. What we mean by “unicorn language users” is that when we study languages, or when we think of people who speak languages, there is that stereotypical image that comes to our mind, and it oftentimes has to be, “Oh, maybe a fluent speaker or a native speaker.” But what does that even mean in a minority language context where language transmission has been stopped and then back regained in a completely different way? Then you also have these ways of thinking from the past intermingled with the modern reality. Who is a Basque speaker?

Gretchen: Right. Is it true that basically every Basque speaker at this point is bilingual?

Itxaso: Absolutely. When you do research with Basque, and with many minority languages, you have to do it in a multilingual way of thinking because if there is a minority, it’s for a reason.

Gretchen: You can’t find this unicorn Basque speaker who’s a monolingual you can compare to your unicorn Spanish monolingual – well, there are Spanish monolingual speakers – but trying to have this direct comparison is not something that’s gonna be realistic. Your co-authors of this paper are speakers of Galician and Catalan –

Itxaso: Also, Greek.

Gretchen: And also, Greek!

Itxaso: Cypriot Greek.

Gretchen: Cypriot Greek – who have had similar experiences with being – we’re not saying “heritage speakers” – but being speakers that have connected to multiple bilingual experiences.

Itxaso: Minorities, right. It all unites us because all of us had some experience that was within Spain. Either we grew up or we live in the nation state of Spain. What was interesting is that, as we were discussing this paper, all of us had slightly different experiences as users of minority languages. In Catalan or in Galician or Basque and also Cypriot Greek. I said, “How can we understand all of these complex or slightly different ways of experiencing” – and our experiences have also changed throughout our lives. How is it that we use the language – what associations we have, what the language means to us, or the languages mean to us, what kind of multi-lingual practices we actually engage in. At the same time, I remember that in the paper we also reflected a little bit on how we also engaged in our research in these unicorn searches in the beginning and how to unlearn that.

Gretchen: Because when you’re first trying to write a paper about Basque, and you’re saying, “Okay, I’m gonna interview these Basque speakers, and I’ve got to find people who are the closest to monolingual that I can,” or who embody these sort of, “They learned this language before a certain age,” because your professors or the reviewers for the paper or the journals – what you think people want or these studies that you’ve been exposed to already have this very specific idea of what a speaker is or a language user – because we wanna include signers and stuff as well – what exactly someone is to know a language compared to the reality of what’s going on on the ground which is much more complex than that.

Itxaso: Absolutely. I feel like we have to self-reflect onto how is it that we’re representing and doing research – or the issue of representation becomes really, really, really important. What is it that we’re describing, what is it that we’re explaining, how are we doing it. Sometimes, there’re power dynamics within this knowledge in the field. When you wanna publish a paper in a top journal, there’s certain practices.

Gretchen: And they wanna have a monolingual control group. “Oh, you’ve got to compare everything to English speakers or to Spanish speakers because they’re big languages we’ve heard of.” Like, “Can’t I just write about Basque because there’re lots of papers that are only about English or only about Spanish? Why can’t there be papers only about Basque?”

Itxaso: Exactly. And you are thinking, “Wait a minute, I can’t find a Basque monolingual.” Maybe they exist, but they’re not readily, either, available, or it’s not common –

Gretchen: In a cave somewhere.

Itxaso: Right. We’re like, “Okay, well” – exactly. Or maybe they do live monolingually.

Gretchen: Yeah, but they still have some exposure to Spanish even though most of their life they’re in Basque. And going and finding this 1% of speakers who managed to live this monolingual life – how well is that really representing a typical Basque experience or a breadth of experiences with the language, which, most of which have some level of multilingualism?

Itxaso: Correct. We as researchers sometimes have to pick. When we make those decisions, we sometimes do not make those decisions consciously because a lot of those questions might come from the field. But then this paper also allowed us to reflect on also thinking, “Why is it that I have to put up with this? This is not working properly and describing things that matter to us” – and matter to us as a community, not only as researchers. Why is it that my parents’ varieties do not get represented that well? Why is it that other participants do not make it to the experiment because they get excluded on the basis of just, oh, literacy, and things like that, which becomes a sticking point as well. Who is a unicorn? Well, clearly there are no unicorns. There are many unicorns.

Gretchen: Sometimes, I think that there’s an idea that being, say, a bilingual speaker is like being two monolingual speakers in a trench coat. The thing that you’re looking for, this unicorn-balanced bilingual of someone who uses their languages in all contexts and is completely “fluent” – whatever we mean by that – in all contexts when, in reality, many people who live bilingual or multilingual lives have some language they use with their family or some language they use at the workplace or in public or that they’re reading more or that they’re consuming media in more. They have different contexts in which they use different languages.

Itxaso: Compartmentalisation is very important but not full compartmentalisation either. There’s gonna be a lot of different overlaps – and so many different experiences. Another thing is that I think doing research with new speakers is important is because those experiences may change from year to year.

Gretchen: Your parents’ cohort of new speakers compared to new speakers who are teenagers now – they’re gonna have very different experiences.

Itxaso: Or maybe a new speaker when they are teenagers versus when they’re in the labour market versus when –

Gretchen: They’re having kids or they’re grandparents or something are gonna have very different experiences even throughout the course of their lives.

Itxaso: Even myself, me as a Basque speaker, my way of speaking has also changed or the way I adapt. One of the challenges in the Basque Country has been “What are the processes – or how is it that they decide, ‘I’m gonna speak the language’?” It’s a continuation. This adoption of the language, you don’t fully, suddenly adopt it.

Gretchen: You don’t adopt it and then that’s all, you’re only speaking Basque from now on. It’s a decision that you’re making every day, “Am I gonna speak Basque in this context? Am I gonna keep using it?”

Itxaso: You negotiate that because, obviously, when you speak a minority language, you’re gonna be reminded that certain challenges might come on the way. Some new speakers might like to be corrected, but some might not.

Gretchen: So, how do you negotiate “Are you gonna correct this person?” “Are you not gonna correct this person?” “Can you ask for correction?” What do you want out of that situation?

Itxaso: Some new speakers, they might want to also sound like regional dialects or older dialects, but some others might not. They create other ways to authenticate themselves and to invest in the language and to invest in the practices that come with it. Each person is unique at the individual level, but then at the collective level, things happen, too. Understanding those is very, very, very, very important.

Gretchen: The balance between the language in an individual and also a language in the community or in a collective group of people who know a language – both of those things existing. We’ve talked a lot about new speakers of Basque. Are there also heritage speakers in the Basque context?

Itxaso: There are. In fact, they do exist. The question is, “Who would these people be?” These people could actually be people that grew up speaking Basque at home but maybe, during the dictatorship, they didn’t have access to the schooling in Basque, so they might not have literacy skills in Basque – so older generations.

Gretchen: They might have things that are in common with heritage speakers. The way that I’ve heard “heritage speakers” get talked about in the Canadian or North American context is often through immigrants. Your parents immigrate from somewhere, and then the kids grow up speaking the parents’ language but also the broader community language and that parents’ language as a heritage language. That still happens in Basque; it’s just that wasn’t your experience in Basque, so you wanna have a distinction between heritage and new speakers.

Itxaso: It’s also true that sometimes if we focus too much on the new speakers, we actually also forget describing the experiences of these individuals that we might consider from the literature as heritage speakers because they don’t use this term for themselves.

Gretchen: The heritage speakers don’t use it for themselves?

Itxaso: Yeah. Or the Basque people that say, “I am just a Basque speaker” or a “traditional Basque speaker” but in a different way. They usually say, “But I don’t do the standard.”

Gretchen: “I’m not very good.”

Itxaso: Sometimes, they think that their Basque is not good enough because they don’t have that literacy.

Gretchen: Or they might be able to understand more than they can talk, sometimes happens to people.

Itxaso: Yeah, sometimes it can happen. Or they talk very fluently, but then they say, “I don’t understand the news,” because they’re in the Standard.

Gretchen: Finally, if you could leave people knowing one thing about linguistics, whether Basque-specific or not, what would that be?

Itxaso: I think that – oof, that’s a loaded question, I love it. For me, I would say linguistics is rebellion. Linguistics is therapy. Linguistics is healing. A linguist is the future. [Laughs] And minority languages have a lot to show about that. In this case, it’s Basque – or for me it’s Basque because I’m intimately related to Basque – but those are the key aspects that I would say that you can do therapy through linguistics.

Gretchen: Linguistics is therapy. Linguistics is rebellion. I love it. That’s so great.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, SoundCloud, YouTube, or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr. You can get bouba and kiki scarves, posters with our aesthetic redesign of the International Phonetic Alphabet on them, t-shirts that say, “Etymology isn’t Destiny,” and other Lingthusiasm merch at lingthusiasm.com/merch. I can be found as @GretchenAMcC on Twitter, my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com, and my book about internet language is called Because Internet. Lauren tweets and blogs as Superlinguo. Our guest, Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez, can be found at BasqueUIUC.wordpress.com. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus topics include a behind-the-scenes interview with Lingthusiasm team member, Martha Tsutsui-Billins, a recap about linguistics institutes, a.k.a., linguist summer camps, and a linguistics advice episode. Also, if you like Lingthusiasm but wish it would help put you to sleep better, we also have a very special Lingthusiasmr bonus episode [ASMR voice] where we read some linguistics stimulus sentences to you in a calm, soothing voice. [Regular voice] Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language. Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Itxaso: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#language#linguists#lingthusiasm#podcasts#episode 86#transcripts#interviews#basque#language revitalization#transcript#language acquisition#language ideology#standard language ideology

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

And the same in English:

Kalevala, the “Finnish National Epic” is a gross, racist, colonialist piece of garbage. It was written and compiled by Elias Lönnrot in the 1800s. This is the gross, racist logic he followed:

-Other countries have epics, Finland needs an epic, but all the ‘real’ Finnish culture has already died away because of modernity.

-Oh I know, the Karelian people are less advanced than Finns! Therefore whatever nonsense they believe is what Finns used to believe, and that is our ancient heritage as well!

-I will go on various trips to record songs and poems and stories by Karelians to find the ancient Finnish epic.

-Hmm, all this material I have collected is a little bit all over the place. This is not good enough. I will have to make some changes. And leave some stuff out. And also maybe make some stuff up myself. Maybe entire characters. Yes, I shall do that.

-Yes, the epic is ready! I can publish it for the whole world to see! Now Finland has an epic and we are ready to get this nationalism thing really going! Whoo! We are a real nation because we have real cultural heritage!

-

Fast forward a couple hundred years and Karelians are regularly called both “just Finnish and your language is just a dialect of Finnish” and “slur for Russians.” Finns have never even attempted to repair what they have done to the Karelians and are actively hindering any attempts at Karelian revitalisation.

And there is currently a bid to get the Kalevala on the Unesco list of intangible cultural heritage. I will be mad as hell if that passes.

Like Finland has real cultural heritage. It has national cultural heritage, it has regional cultural heritage, it has minorities with important cultural heritage. There is a lot here.

But apparently Finns want to die on this gross, racist hill instead. -_-

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … March 12

1860 – Eric, Count Stenbock, Estonian poet and author of macabre fantastic fiction, born (d.1895); Stenbock's father died suddenly while he was one year old; his properties were held in trust for him by his grandfather Magnus. Eric's maternal grandfather died while Eric was quite young, also, in 1866, leaving him another trust fund.

Stenbock attended Balliol College in Oxford but never completed his studies. While at Oxford, Eric was deeply influenced by the homosexual Pre-Raphaelite artist and illustrator Simeon Solomon. He is also said to have had a relationship with the composer and conductor Norman O'Neill and with other "young men".

Stenbock behaved eccentrically. He kept snakes, lizards, salamanders and toads in his room, and had a "zoo" in his garden containing a reindeer, a fox, and a bear. When he traveled, he invariably brought with him a dog, a monkey, and a life-sized doll. This doll he referred to as "la Petite Comte" ("the little Count") and told everyone that it was his son; he insisted it be brought to him daily, and—when it was absent—he asked about its health. (Stenbock's family believed an unscrupulous Jesuit had been given large amounts of money by the Count for the "education" of this doll.)

One never knew what one would find at this house, where he wrote his opium-induced poems and stories and where he kept a pet toad named Fatima and a lover picked up on a London bus. Visiting Stenbock one day, Oscar Wilde dared to light a cigarette at the votive lamp before the bust of Shelley that his host venerated. This sacrilege caused Stenbock, in true dandy style, to fall to the floor in a dead faint. The unperturbed Wilde, in even truer dandy form, exhaled a puff of smoke, stepped over the prostrate body, and took his leave.

Stenbock lived in England most of his life, and wrote his works in the English language. He published a number of books of verse during his lifetime, including Love, Sleep, and Dreams, 1881, and Rue, Myrtle, and Cypress (1883). In 1894, Stenbock published The Shadow of Death, his last volume of verse, and Studies of Death, a collection of short stories that were good enough to be the subject of favorable comment by H.P. Lovecraft.

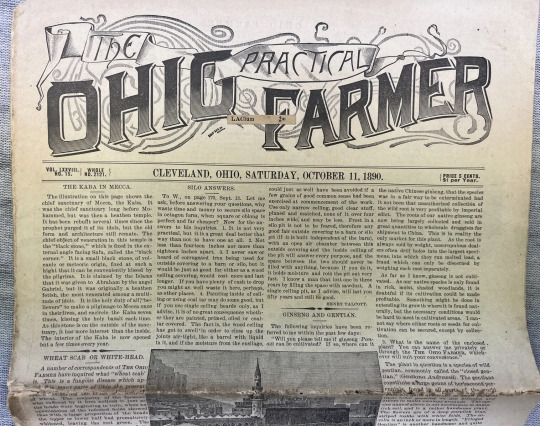

1890 – An Ohio newspaper publicizes the suicide of a married man who had taken another man he met in a bar back to his hotel room. A letter in his pocket from his wife complains that she hadn't heard from him.

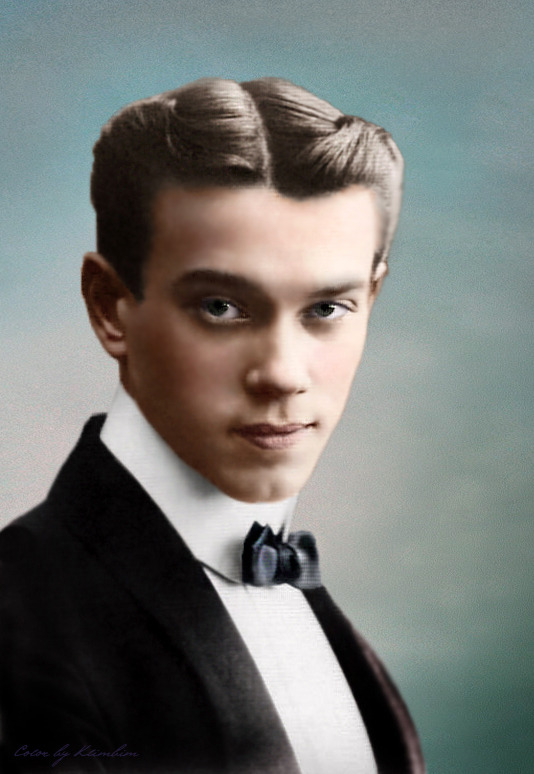

1890 – Vaslav Nijinsky (d.1950); A Russian ballet dancer and choreographer of Polish origin, Nijinsky was one of the most gifted male dancers in history, and he became celebrated for his virtuosity and for the depth and intensity of his characterizations. He could perform en pointe, a rare skill among male dancers at the time and his ability to perform seemingly gravity-defying leaps was legendary.

Probably the greatest male ballet dancer of all time, Nijinsky's two greatest achievements, assisted by his impresario lover Sergei Diaghilev, were to bring the role of the male dancer to the fore, and to revitalise a world of classical ballet which had entered a period of decline.

Born in Kiev, Ukraine to Polish dancer parents, he was admitted to the St Petersburg Imperial School of Ballet aged 10, where he received an excellent general education as well as a thorough grounding in classical ballet. He was a brillant student and on graduation joined the Imperial Ballet as a soloist in 1907.

He had two love affairs with two Russian noblemen, Prince Pavel Dmitrievitch Lvov and Count Tishkievitch but then he met Sergei Diaghilev, a member of the St Petersburg elite and wealthy patron of the arts, promoting Russian visual and musical art abroad, particularly in Paris.

Nijinsky and Diaghilev became lovers, and Diaghilev became heavily involved in directing Nijinsky's career. In 1909 Diaghilev took a company to Paris, with Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova as the leads. The show was a great success and increased the reputation of both the leads and Diaghilev throughout the artistic circles of Europe.Diaghilev created Les Ballets Russe in its wake, and with choreographer Michel Fokine, made it one of the most well-known companies of the time. His partnership with Tamara Karsavina, of the Mariinsky Theatre, was legendary.

Later, Nijinsky danced again the Mariinsky Theatre, but was dismissed for appearing on- stage wearing tights without the trunks obligatory for male dancers in the company. The Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna complained that his appearance was obscene, and he was dismissed. It is probable that the scandal was arranged by Diaghilev so Nijinsky could be free to appear with his company, in the west, where many of his projects now centered around him. He danced leading roles in Fokine's new production Le Spectre de la Rose, a role never satisfactorily danced since his retirement, and Igor Stravinsky's Petrushka, in which his impersonation of a dancing but lifeless puppet was much admired.

In 1913 he married a young Hungarian woman, Romola Pulszky, who had travelled throughout Europe in pursuit of her dieu de la danse, whilst on tour in Buenos Aires. Devastated by his betrayal, Diaghilev dismissed his star from the company leaving Nijinsky stranded with wife and child and no career - furthermore, it was the First World War and Nijinsky was a Russian citizen in Hungary, and technically a prisoner of war.

Diaghilev attempted a reconciliation with Nijinsky, inviting him to rejoin the Ballet Russes on more than one occasion, but relations between the two former lovers and Nijinsky's wife frustrated every attempt to recreate his former success.

In the later years of the First World War signs of Nijinsky's mental illness became increasingly obvious to his wife and colleagues. In 1919 he suffered a mental breakdown. Increasingly unhappy with his marriage, his ruined career, and a world in turmoil, Romola committed him to a mental institution where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia and subjected to years of drugs and experimental shock treatment. He became a broken man and spent the rest of his life drifting between institutions, even having to be rescued from one asylum when the Nazis began to inter the mentally ill. He died in London in 1950.

Nijinsky's Grave,

Montmartre Cemetary, Paris

Of the thousands of descriptions of the famous dancer, only Cocteau's suggests the "mortal god" that was Nijinsky. Cocteau alone observed

"the contrast between the Nijinsky of Le Spectre de la Rose, bowing and smiling to thunderous cheers as he took his fifty curtain calls, and the poor athlete backstage between bows, gasping and leaning against any support he could find, half fainting, clutching his side, being given his shower and massage and rubdown by his attendance and the rest of us. On one side of the curtain he was a marvel of grace, on the other, an extraordinary example of strength and weakness..."

Early pic of Sergei, Vladimir and siblings

1900 – Sergei Nabokov (d.1945), brother of Russian author Vladimir Nabokov, was born in St. Petersburg. The Nabokovs were members of imperial Russia's most exclusive social circles. The family was extraordinarily wealthy; their lineage included princes and generals and government ministers, and even their faithful dog, Box II, was descended from a pair that belonged to Anton Chekhov.

While Vladimir was the eldest and the center of attention, Sergei grew up out of the limelight, shy and unhappy and somewhat odd. Sergei was afflicted with an atrocious stutter that would only get worse as he got older. He idolized Napoleon and slept with a bronze bust of him in his bed. He also loved music, particularly Richard Wagner, and he studied the piano seriously.

Vladimir and Sergei Nabokov

When he was 15 and Vladimir 16, Vladimir found Sergei's diary open on his desk and read it. He showed it to their tutor, who showed it to the children's father. It was proof of his blossoming sexuality.

His homosexuality was behind Sergei's withdrawal from the famously progressive Tenishev school, an all-boy private school also attended by Vladimir and by poet Osip Mandelstam. Sergei left because of a series of "unhappy romances," about which his family instituted a kind of "don't ask, don't tell" policy.

When the revolution came in 1917, the Nabokov family fled Russia, barely escaping with a fraction of their fortune on a Greek cargo boat loaded with dried fruit. Neither Vladimir nor Sergei would ever return to his motherland. After brief stops in Athens and Paris, Vladimir wound up enrolled at Cambridge University; Sergei started at Oxford but joined his brother at Cambridge a semester later, where they both earned degrees.

When the brothers graduated in 1922, they joined their family in Berlin, which had become the social and cultural center of the Russian diaspora. Sergei fit easily into the growing gay community there, and he was friendly with German activist Magnus Hirschfeld, founder of the world's first gay tolerance organization. Sergei and Vladimir went to work at a bank, but the 9-to-5 routine didn't suit them: Sergei quit after a week, Vladimir in a matter of hours. Vladimir remained in Berlin, where he met and married his wife, Vira, but Sergei moved on to Paris.

In the Paris in the '20s, Sergei most likely felt at home for the first time in a city that celebrated art and music, and that took his gayness in stride.

In the winter of 1923 he met painter Pavel Tchelitchev, whose work now hangs in New York's Museum of Modern Art and who painted sets for Sergei Diaghilev. Tchelitchev was also gay and also a Russian imigri, and the two of them shared an apartment with Tchelitchev's lover, Allen Tanner.

The flat was tiny. It had no electricity and no bath — they had to wash themselves in a zinc tub using water heated on a gas stove. Sergei survived by giving lessons in English and Russian.But the cultural scene in which Sergei found himself was rich. Sergei became good friends with Jean Cocteau, and he was also connected, through Tchelitchev, and his cousin Nicolas Nabokov, to Diaghilev, to composer Virgil Thomson, to the Sitwells and even to the legendary salons conducted by Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas.