#late minoan ii

Text

~ Terracotta vase in the form of a bull's head.

Period: Late Minoan II

Date: ca. 1450–1400 B.C.

Culture: Minoan

Medium: Terracotta

#ancient#ancient art#ancient pottery#pottery#Terracotta vase#bull's head#bull#Terracotta#minoan#late minoan ii#ca. 1450 b.c.#ca. 1400 b.c#history#archeology#museum

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you make a post about the evolution of Greek art from the ancient times until now in modern age?

Because we often talk about the evolution of art but unfortunately we don't appreciate after ancient times the other art movements Greece went through the centuries.

That’s true! I am sorry for taking ages to answer this but I don't know how it could take me less anyway hahaha I made this post with summaries about all artistic eras in Greek history. I have most of it under a cut because with the addition of pictures it got super long, but if you are interested in the history of art I recommend giving it a try! I took advantage of all 30 pictures that can be possibly attached in a tumblr post and I tried to cover as many eras and art styles as possible, nearly dying in the process ngl XD I dedicated a few more pictures in modern art, a) because that was the ask and b) because there is more diversity in the styles that are used and the works that are available to us in great condition in modern times.

History of Greek Art

Greek Neolithic Art (c. 7000 - 3200 BC)

Obviously, with this term we don’t mean there were people identifying as Greeks in Neolithic times, but it defines the Neolithic art corresponding to the Greek territory. Art in this era is mostly functional, there are progressively more and more defined designs on clay pots, tools and other utility items. Clay and obsidian are the most used materials.

Clay vase with polychrome decoration, Dimini, Magnesia, Late or Final Neolithic (5300-3300 BC).

Cycladic Art (3300 - 1100 BC)

The art of the Cycladic civilisation of the Aegean Islands is characterized by the use of local marble for the creation of sculptures, idols and figurines which were often associated to womanhood and female deities. Cycladic art has a unique way of incidentally feeling very relevant, as it resembles modern minimalism.

Early Cycladic II (Keros-Syros culture, 2800–2300 BC)

Minoan Art (3000-1100 BC)

The advanced Minoan civilisation of Crete island was projecting its confidence and its vibrancy through its various arts. Minoan art was influenced by the earlier Egyptian and Near East cultures nearby and at its peak it overshadowed the rest of the contemporary cultures and their artistic movements in Greece. Colourful, with numerous scenes of everyday life and island life next to the sea, it was telling of the society’s prosperity.

The Bull-leaping fresco from Knossos, 1450 BC.

Mycenaean Art (c. 1750 - 1050 BC)

Mycenaean Art was very influenced by Minoan Art. Mycenaean art diverged and distinguished itself more in warcraft, metalwork, pottery and the use of gold. Even when similar, you can tell them apart from their themes, as Mycenaean art was significantly more war-centric.

The Mask of Agamemnon in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The mask likely was crafted around 1550 BC so it predates the time Agamemnon perhaps lived.

Geometric Art (1100 - 700 BC)

Corresponding to a period we have comparatively too little data about, the Geometric Period or the Homeric Age or the Greek Dark Ages, geometric art was characterized by the extensive use of geometric motifs in ceramics and vessels. During the late period, the art becomes narrative and starts featuring humans, animals and scenes meant to be interpreted by the viewer.

Detail from Geometric Krater from Dipylon Cemetery, Athens c. 750 BC Height 4 feet (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Archaic Art (c. 800 - 480 BC)

The art of the archaic period became more naturalistic and representational. With eastern influences, it diverged from the geometric patterns and started developing more the black-figure technique and later the red-figure technique. This is also the earliest era of monumental sculpture.

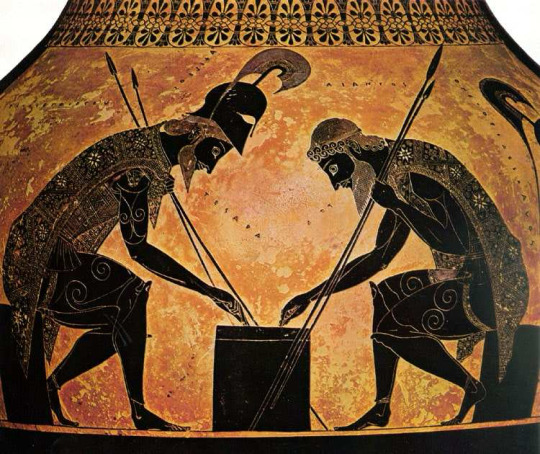

Achilles and Ajax Playing a Board Game by Exekias, black-figure, ca. 540 B.C.

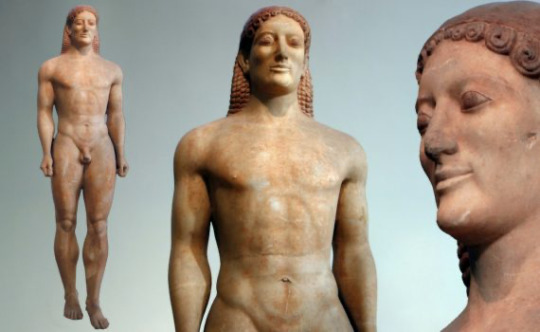

Kroisos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.

Classical Art (c. 480 - 323 BC)

Art in this era obtained a vitality and a sense of harmony. There is tremendous progress in portraying the human body. Red-figure technique definitively overshadows the use of the black-figure technique. Sculptures are notable for their naturalistic design and their grandeur.

The Diskobolos or Discus Thrower, Roman copy of a 450-440 BCE Greek bronze by Myron recovered from Emperor Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, Italy. (British Museum, London). Photo by Mary Harrsch.

Terracotta bell-krater, Orpheus among the Thracians, ca. 440 BCE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hellenistic Art (323 - 30 BCE)

Hellenistic art perfects classical art and adds more diversity and nuance to it, something that can be explained by the rapid geographical expansion of Greek influence through Alexander’s conquests. Sculpture, painting and architecture thrived whereas there is a decrease in vase painting. The Corinthian style starts getting popular. Sculpture becomes even more naturalistic and expresses emotion, suffering, old age and various other states of the human condition. Statues become more complex and extravagant. Everyday people start getting portrayed in art and sculpture without extreme beauty standards imposed. We know there was a huge rise in wall painting, landscape art, panel painting and mosaics.

Mosaic from Thmuis, Egypt, created by the Ancient Greek artist Sophilos (signature) in about 200 BC, now in the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, Egypt. The woman depicted in the mosaic is the Ptolemaic Queen Berenike II (who ruled jointly with her husband Ptolemy III) as the personification of Alexandria.

Agesander, Athenodore and Polydore: Laocoön and His Sons, 1st century BC

Greco-Roman Art (30 BC - 330 AD)

This period is characterized by the almost entire and mutually influential merging of Greek and Roman artistic expression, in light of the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world. For this era, it is hard to find sources exclusively for Greek art, as often even art crafted by Greeks of the Roman Empire is described as Roman. In general, Greco-Roman art reinforces the new elements of Hellenistic art, however towards the end of the era, with the rise of early Christianity in the Eastern aka the Greek-influenced part of the empire, there are some gradual shifts in the art style towards modesty and spirituality that will in time lead to the Byzantine art. During this era mosaics become more loved than ever.

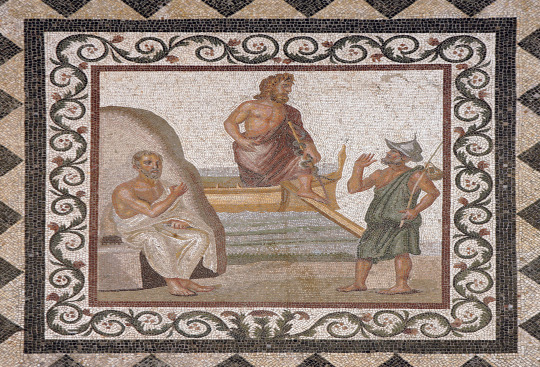

A mosaic from the island of Kos (the birthplace of Hippocrates) depicting Hippocrates (seated) and a fisherman greeting the god Asklepios (center) as he either arrives or disembarks from the island. Second or third century CE.

Introduction to Byzantine Art

Byzantine art originated and evolved from the now Christian Greek culture of the Eastern Roman Empire. Although the art produced in the Byzantine Empire was marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, it was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic defined by its salient "abstract", or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to have abandoned this attempt in favor of a more symbolic approach. The subject matter of monumental Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the two themes are often combined.

Early Byzantine Art (330 - 842 AD)

The establishment of the Christian religion results in a new artistic movement, centered around the faith. However, ancient statuary remains appreciated. Most fundamental changes happen in monumental architecture, the illustration of manuscripts, ivory carving and silverwork. Exceptional mosaics become integral in artistic expression. The last 100 years of this period are defined by the Iconoclasm, which temporarily restricts entirely the previously thriving figural religious art.

Mosaics in the Rotunda of Thessaloniki, 4th - 6th century AD.

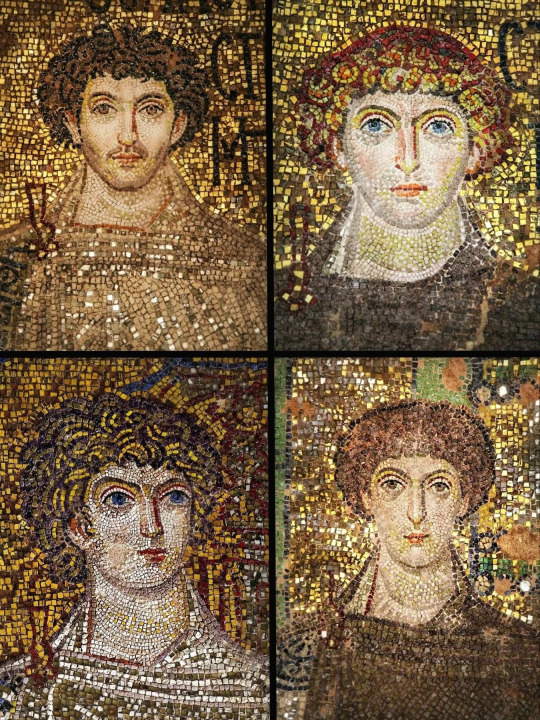

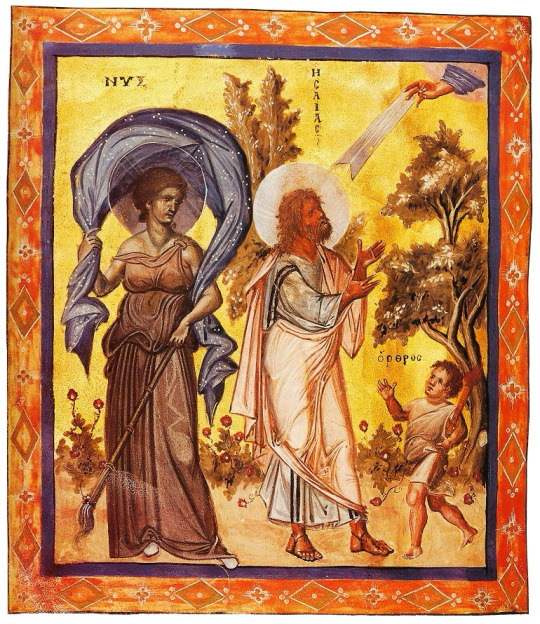

Macedonian Art & Komnenian Age (843 - 1204 AD)

These artistic periods correspond to the middle Byzantine period. After the end of the Iconoclasm, there is a revival in the arts. The art of this period is frequently called Macedonian art, because it occurred during the Macedonian imperial dynasty which generally brought a lot of prosperity in the empire. There was a revival of interest in the depiction of subjects from classical Greek mythology and in the use of Hellenistic styles to depict religious subjects. The Macedonian period also saw a revival of the late antique technique of ivory carving. The following Komnenian dynasty were great patrons of the arts, and with their support Byzantine artists continued to move in the direction of greater humanism and emotion. Ivory sculpture and other expensive mediums of art gradually gave way to frescoes and icons, which for the first time gained widespread popularity across the Empire. Apart from painted icons, there were other varieties - notably the mosaic and ceramic ones.

Paris Psalter, 10th century AD. Prophet Isaiah from the Old Testament in the company of the symbolisms for night (clear inspiration drawn from the ancient deity Nyx) and morning (Orthros, not to be confused with the mythological creature).

Palaeologan Renaissance (1261 - 1453)

The Palaeologan Renaissance is the final period in the development of Byzantine art. Coinciding with the reign of the Palaeologi, the last dynasty to rule the Byzantine Empire (1261–1453), it was an attempt to restore Byzantine self-confidence and cultural prestige after the empire had endured a long period of foreign occupation. The legacy of this era is observable both in Greek culture after the empire's fall and in the Italian Renaissance. Contemporary trends in church painting favored intricate narrative cycles, both in fresco and in sequences of icons. The word "icon" became increasingly associated with wooden panel painting, which became more frequent and diverse than fresco and mosaics. Small icons were also made in quantity, most often as private devotional objects.

Detail of Anástasis (Resurrection) fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist).

Cretan School (15th - 17th century)

Cretan School describes an important school of icon painting, under the umbrella of post-Byzantine art, which flourished while Crete was under Venetian rule during the Late Middle Ages, reaching its climax after the Fall of Constantinople, becoming the central force in Greek painting during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. By the late 15th century, Cretan artists had established a distinct icon-painting style, distinguished by "the precise outlines, the modelling of the flesh with dark brown underpaint, the bright colours in the garments, the geometrical treatment of the drapery and, finally, the balanced articulation of the composition". Contemporary documents refer to two styles in painting: the maniera greca (in line with the Byzantine idiom) and the maniera latina (in accordance with Western techniques), which artists knew and utilized according to the circumstances. Sometimes both styles could be found in the same icon. The most famous product of the school was the painter Domenikos Theotokopoulos, internationally known as El Greco, whose art evolved and diverged significantly in his later years when he moved in Spain and was involved in the Spanish Renaissance, and though it often alienated his western contemporary artists, nowadays it is viewed as an incidental early birth of Impressionism in the mid of the Renaissance’s peak.

Icon by Andreas Pavias (1440-1510), Cretan School, from Candia (Venetian Kingdom of Crete). The Latin inscription suggests the icon was meant for commercial purposes in Western Europe. National Museum, Athens. (Source: https://russianicons.wordpress.com/tag/cretan-school/)

Crucifixion (detail), El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos), ca. 1604 - 1614.

Heptanesian School (17th - 19th century)

The Heptanesian school succeeded the Cretan School as the leading school of Greek post-Byzantine painting after Crete fell to the Ottomans in 1669. Like the Cretan school, it combined Byzantine traditions with an increasing Western European artistic influence and also saw the first significant depiction of secular subjects. The center of Greek art migrated urgently to the Heptanese (Ionian) islands but countless Greek artists were influenced by the school including the ones living throughout the Greek communities in the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere in the world. Greek art was no longer limited to the traditional maniera greca dominant in the Cretan School. Furthermore, the Heptanesian school was the basis for the emergence of new artistic movements such as the Greek Rocco and Greek Neoclassicism. The movement featured a mixture of brilliant artists.

Archangel Michael, Panagiotis Doxaras, 18th century.

Greek Romanticism (19th century)

Modern Greek art, after the establishment of the Greek Kingdom, began to be developed around the time of Romanticism. Greek artists absorbed many elements from their European colleagues, resulting in the culmination of the distinctive style of Greek Romantic art, inspired by revolutionary ideals as well as the country's geography and history.

Vryzakis Theodoros, The Exodus from Missolonghi, 1853. National Gallery, Athens.

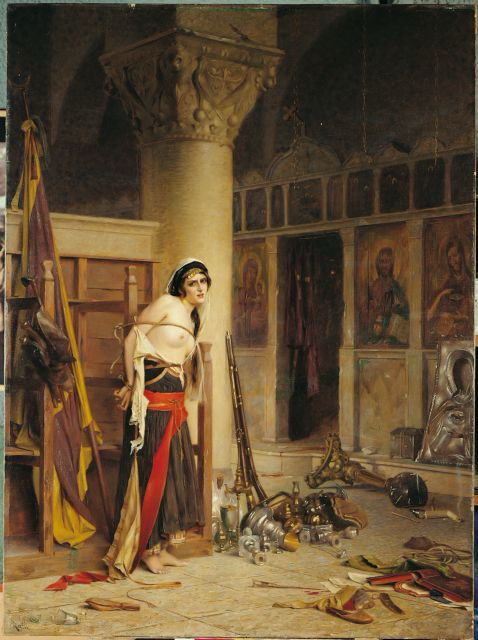

The Munich School (19th century Academic Realism)

After centuries of Ottoman rule, few opportunities for an education in the arts existed in the newly independent Greece, so studying abroad was imperative for artists. The most important artistic movement of Greek art in the 19th century was academic realism, often called in Greece "the Munich School" because of the strong influence from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Munich where many Greek artists trained. In academic realism the imperative is the ethography, the representation of urban and/or rural life with a special attention in the depiction of architectural elements, the traditional cloth and the various objects. Munich School painters were specialized on portraiture, landscape painting and still life. The Munich school is characterized by a naturalistic style and dark chiaroscuro. Meanwhile, at the time we observe the emergence of Greek neoclassicism and naturalism in sculpture.

Nikolaos Gyzis, Learning by heart, 1883.

Rallis Theodoros, The Booty, before 1906.

20th Century Modern & Contemporary Greek Art

At the beginning of the 20th century the interest of painters turned toward the study of light and color. Gradually the impressionists and other modern schools increased their influence. The interest of Greek painters, artists changes from historical representations to Greek landscapes with an emphasis on light and colours so abundant in Greece. Representatives of this artistic change introduce historical, religious and mythological elements that allow the classification of Greek painting into modern art. The era of the 1930s was a landmark for the Greek painters. The second half of the 20th century has seen a range of acclaimed Greek artists too serving the movements of surrealism, metaphysical art, kinetic art, Arte Povera, abstract excessionism and kinetic sculpture.

Yiannis Moralis, Two friends, 1946.

Art by Giannis Gaitis (1923-1984), famous for his uniformed little men.

By Yorghos Stathopoulos (1944 - )

Art (detail) by Nikos Engonopoulos (1907 - 1985)

Folk, Modern Ecclesiastical and Secular Post-Byzantine Art

Ecclesiastical art, church architecture, holy painting and hymnology follow the order of Greek Byzantine tradition intact. Byzantine influence also remained pivotal in folk and secular art and it currently seems to enjoy a rise in national and international interest about it.

A modern depiction of the legendary hero Digenes Akritas depicted in the style of a Byzantine icon by Greek artist Dimitrios Skourtelis. Credit: Dimitrios Skourtelis / Reddit

Erotokritos and Aretousa by folk artist Theophilos (1870-1934)

Example of Modern Greek Orthodox murals, Church of St. Nicholas.

Ancient Greek philosophers depicted in iconographic fashion in one of Meteora’s monasteries. Each is holding a quote from his work that seems to foreshadow Christ. Shown from left to right are: Homer, Thucydides, Aristotle, Plato and Plutarch. This is not as weird as it may initially seem: it was a recurrent belief throughout the history of Christian Greek Orthodoxy that the great philosophers of the world heralded Jesus' birth in their writings - it was part of the eras of biggest reconciliation between Greek Byzantinism and Classicism.

Prophet Elijah icon with Chariot of Fire, Handmade Greek Orthodox icon, unknown iconographer. Source

If you see this, thanks very much for reading this post. Hope you enjoyed!

#greece#art#europe#history#culture#greek art#artists#greek culture#history of art#classical art#ancient greek art#byzantine greek art#christian art#orthodox art#modern art#modern greek art#anon#ask

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

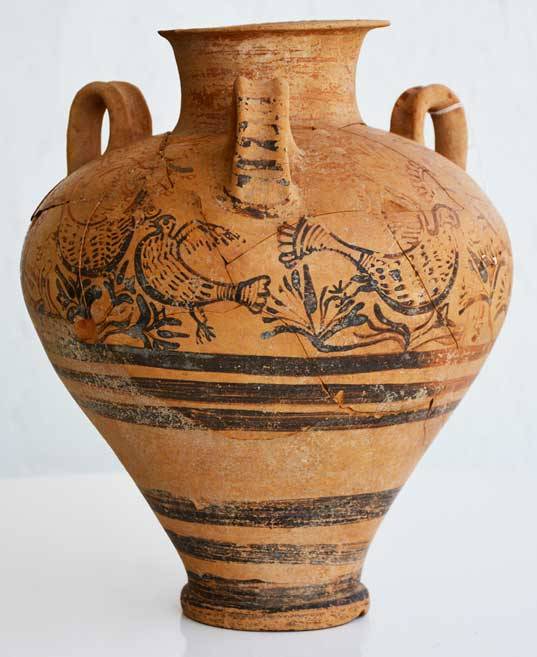

“Pottery jar from Knossos, Late Minoan II Ashmolean Museum”

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chalice made of red granite

Early Minoan II - Late Minoan III, ca. 1750-1450 BC

The Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chalcedony lentoid seal

ca. 1450–1400 B.C.

View full size image

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mycenaean period Greece (late Bronze Age).

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750–1050 BC. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland Greece with its palatial states, urban organization, works of art, and writing system. The most prominent site was Mycenae, in the Argolid, after which the culture of this era is named. Other centers of power that emerged included Pylos, Tiryns, Midea in the Peloponnese, Orchomenos, Thebes, Athens in Central Greece and Iolcos in Thessaly. Mycenaean and Mycenaean-influenced settlements also appeared in Epirus, Macedonia, on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the coast of Asia Minor, the Levant, Cyprus, and Italy.

1. Mycenaean period armor, Dendra panopy and Thebes panoply, from the Koryvantes Reenacting Group

2. Boar tusk helmet from Mycenae, and carved depictions of such helmets in ivory

3. Mycenaean gold earring, Late helladic II, ca. 13th century BCE

4. Mycenaean wealthy woman or priestess depicted as weaving in a palace (Actually, this work would have been done by slaves) Art by Serena Malyon. You can see the similarity between this outfit and earlier Minoan clothing.

5. Mycenaean warrior and panoply from late bronze age, ca. 1300-1200 BCE, from the Koryvantes Reenacting Group

6. Mycenaean gold octopus brooch

#fashion#ancient greece#ancient greek fashion#armor#jewelry#helmets#mycenaean fashion#mycenae#mycenaean greece

768 notes

·

View notes

Photo

7 Ruined Palaces Around the World, Reconstructed!

Sans Souci, Haiti,

Called the ‘Versailles of the Caribbean’, the palace’s majestic steps and terraces are an impressive monument to Haitian independence.

Qal’eh Dokhtar, Iran,

Qal’eh Dokhar was built by Ardašīr I as a “barrier fortress” during his 3rd century founding of the Sasanian Empire in Iran. The fortress’s third floor housed his royal residence but was eventually supplanted by a greater palace he built nearby. Qal’eh Dokhtar boasts perhaps the earliest example of an Iranian chartaq—a square of four arches supporting a dome—which became an important feature of traditional Iranian architecture.

Knossos Palace, Greece,

The oldest palace on this list by two millennia, Knossos, was constructed circa 1700 BC. In addition to its political function, it also was designed as an economic and religious centre for the mysterious Minoan civilization. Knossos was destroyed circa 1375 BC—surviving invasion, fire, and earthquake nearly a century longer than similar Minoan complexes.

Ruzhany Palace, Belarus,

The Sapieha family—power-brokers of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—built Ruzhany Palace in the late 1700s over the site of their earlier castle. In its heyday, Ruzhany’s famed theatre employed 100 performers. The palace also possessed a famous library and picture collection.

Dungur Palace / “Palace of the Queen of Sheba,” Ethiopia,

Dungur Palace is in the Ethiopian village of Aksum—once the bustling capital of an African empire that stretched from southern Egypt to Yemen. The 6th-century mansion contains approximately 50 rooms, including a bathing area, kitchen, and (possible) throne room.

Clarendon Palace, UK,

Despite the composition of a very significant English legal document within its halls, this 12th-century palace is nearly forgotten. The ‘Constitutions of Clarendon’ were Henry II’s attempt to gain legal authority over church clerks, but he instead exacerbated a feud with his friend Thomas à Becket. This feud eventually led to Archbishop Beckett’s martyrdom. Henry III expanded the palace, commissioning a carved fireplace and stained glass chapel. By the 1400s, Clarendon was a sprawling royal complex. It remained a favourite retreat of monarchs until the Tudor era, when the high cost of upkeep resulted in its rapid decline. Today, only a single wall remains above ground.

Husuni Kubwa, Tanzania,

The island of Kilwa Kisiwani was one of the most important sultanates in the “Swahili Coast’ trade network, linking East Africa to the Arabic world. For over 300 years, gold and ivory passed out of its ports, while Chinese silk and porcelain flowed in. The 14th-century palace at Husuni Kubwa is just one of many coral stone ruins that dot the island.

Husuni Kubwa was built by Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman. It had over 100 rooms, an octagonal swimming pool, and a staging area for loading goods onto ships. Husuni Kubwa, along with other elite Kilwa dwellings, was also equipped with indoor plumbing.

Created by: Budget Direct in collaboration with: Neomam Studios

#art#design#architecture#palace#palacegif#animated gif#tanzania#husuni kubwa#budgetdirect#neomanstudio#ruined#san souci#haiti#clarendon palace#united kingdom#luxurylifestyle#style#history#belarus#knossospalace#greece#dungur palace#ethiopia#ruzhani palace#iran#qal'eh dokhar#royal#royalpalace

485 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minoan bronze tweezers 2900–1050 BCE

"Tweezers too were used for removing hair and possibly shaping the eyebrows which, as the frescoes clearly show, were regarded as a very important facial feature - and there is no reason to suppose that Minoan men were any less concerned about the beauty of their appearance than Minoan women."

...

"This tweezer type occurred first in the Early Minoan II period and became the standard type used on Crete in the Late Bronze Age."

-taken from metmuseum & erenow

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2020/03/minoan-bronze-tweezers-29001050-bce.html

#minoan#ancient greece#greek#beauty supply#antiquities#cosmetics#ancient#history#europe#pagan#paganism#30th century bce

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Amy Fredrickson

In June 1896, Isabella Stewart Gardner acquired Titian’s The Rape of Europa from Colnaghi & Co. for 20,000 pounds. Correspondence between Bernard Berenson and Mrs. Gardner illustrates the acquisition and the foundation of her collection. Her aim was to create a museum dedicated to Italian artworks for the benefit of the American people. She passionately believed that America was a country in need of art and Americans should have the opportunity to see the beautiful art and objects she revered in Europe. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was completed in 1903 and derived inspiration from the architecture of Palazzo Barbaro in Venice, where she frequently visited.

After learning that The Rape of Europa was for sale from a British private collection, Berenson wrote to Mrs. Gardner offering her the opportunity to purchase the painting. In discussing the painting, Berenson said, 'One of the few greatest Titians in the world is Europa… I am dying to have you get [it]… Cable, please the one word YEUP= Yes Europa, or NEUP= No Europa.' Clearly, she cabled ‘YEUP’ (Hadley 1987, p. 56 ).

Regarding the painting, Berenson wrote on June 7, 1896:

‘Why can’t I be with you when Europa is unpacked! America is a land of wonders, but this sort of miracle it has not witnessed. […] I also spend time dreaming of your Museum. If my dreams make by a fair approach to realization yours shall not be the last among the kingdoms of earth (Hadley 1987, p. 56 ).’

According to Mrs. Gardner, The Rape of Europa became the crown jewel of her growing collection. This painting, in particular, aligned with Mrs. Gardner's tastes. In a letter to Berenson, dated September 19, 1896, she described the joy of her new acquisition:

‘I am breathless about the Europa, even yet! I am back here tonight (when I found your letter) after a two days’ orgy. The orgy was drinking my self-drunk with Europa and then sitting for hours in my Italian garden at Brookline, thinking and dreaming about her. Many came with ‘grave doubts’: many came to scoff; but all wallowed at her feet (Hadley 1987, p. 66 ).’

Berenson replied a few days later on October 7, 1896:

‘I rejoice for dear old Boston that it hath people who can appreciate Europa, and your own pleasure in her is like a sweet savor to my nostrils. Courage, this is not the last of its kind that I hope to help you stock [your museum] with (Hadley 1987, p. 68 ).’

The Titian painting was one of many artworks Berenson helped Mrs. Gardner procure. Her painting is the last of the seven mythological scenes the artist painted for King Philip II of Spain. Titian began painting The Rape of Europa in 1559 and sent the painting to Spain in 1562. The companion paintings to The Rape of Europa are: Danae, Venus and Adonis, Perseus and Andromeda, Diana and Callisto, and Diana and Actaeon. The Rape of Europa is a brilliant example of the Titian’s late manner.

The painting depicts an episode from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The artist portrayed the wily Jupiter after he transformed into a beautiful white bull after seeing Europa. He blended in with a herd of cattle grazing on the sea shore. Accompanied by her companions, Europa approached the tame animal with her outstretched hand. Europa played with the disguised god in the meadow and adorned his horns with flowers. Finding him tame, she climbed on his back and the tricky god whisked her to the sea. From Phoenicia, the bull carried her to Crete, where he revealed his true identity. Consequently, Europa became the queen of Crete, and their union led to the birth of Minos—king of Crete and the Minoans.

The exact moment Titian portrays is when "The god little by little edges away from the dry land, and sets his borrowed hoofs in shallow water; then he goes further out and soon is in full flight with his prize on the open ocean. She trembles with fear and looks back at the receding shore, holding fast a horn with one hand and resting the other on the creature's back. And her fluttering garments stream behind her in the wind." (From Ovid, Metamorphoses, ii. 870-75, quoted by Stone, p. 47).

What is especially striking is that Titian fixed the action of the painting in the corner of the canvas. The monumental figure of his canvas is undoubtedly Europa. Her large form dominates the painting and establishes the naturalistic mood. In one hand, Europa is holding on to the bull by one horn, and in the other she is waving a crimson scarf to attract attention. Titian turned Europa towards the shore where her distraught handmaidens are frantic. His colours blend as the sea and sky unite, and there is the contrast between the reds and blues. Titian's painting is filled with uncertainty—both horror and ecstasy. The latter is bolstered throughout the canvas between the cupids and their bows, the warmth of the sky, and the red cloth blowing in the wind. Adding tensions, a spiny, scaly, menacing sea monster breached the sea surface below Europa, and a cupid, mimicking her pose, trails Europa on a dolphin. Together these elements add to the tension.

Originally, Isabella Stewart Gardner displayed the painting above a fireplace in her Beacon Street home,before placing it its final location. Mrs. Gardner based an entire room around her Titian painting, with opulent fabrics drawing the visitors focus to The Rape of Europa. Mrs. Gardner's installations were personal. In fact, the fabric below The Rape of Europa is from one of her silk gowns from the House of Worth in Paris. Just as Titian represented Europa in a state of rumpled undress, Gardner surrenders one of her garments for the display. She made a clear choice since the bold pattern of the tassels guides the museum visitor to the tail of the bull. How she displayed her collection demonstrates the thought that went into grouping her paintings, furniture, and objects. Her aim was to establish a museum that would leave a lasting legacy in the United States, and her collection is especially remarkable because it is highly personal and unconventional.

Mrs. Gardner often moved objects to include new acquisitions, and she paid attention to little details. For example, on the table underneath Europa is a small cherub that correlates with the cupids in the paintings. She rearranged the gallery twice. Her choice to shift the sculpture's position from standing in 1903 to laying on its side in 1924 corresponds with both Europa's pose and the cupid.

The museum space is remarkable because the works are in the exact place Mrs. Gardner positioned them to be viewed. She achieved her goal to establish a museum for the benefit of the American people and committed to collecting Old Masters. In 1917, Mrs. Gardner stated:

‘Years ago I decided that the greatest need in our Country was Art... We were a very young country and had very few opportunities of seeing beautiful things, works of art... So, I determined to make it my life's work if I could.’

Indeed, she accomplished her dream.

Images

Titian Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Titian, The Rape of Europa, c. 1560-1562, oil on canvas, 178 cm × 205 cm. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

References

Hadley, Rollin van N., ed,. The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1887-1924, With Correspondence by Mary Berenson. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1987)

Pope, Arthur, Titian's Rape Of Europa. (Cambridge: Published for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum by Harvard University Press, 1960)

Stone, Jr., Donald, "The Source Of Titian's Rape Of Europa," The Art Bulletin 54, 1, 1972, pp. 47-49.

"Titian Room | Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum," 2018. Gardnermuseum.Org. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/rooms/titian-room.

#isabella stewart gardner museum#titian#Italian Renaissance#venetian renaissance#venetian painting#history of collecting

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Natalie Jones and the Golden Ship

Part 1/? - A Meeting at the Palace

Part 2/? - Curry Talk

Part 3/? - Princess Sitamun

Part 4/? - Not At Rest

Part 5/? - Dead Men Tell no Tales

Part 6/? - Sitamun Rises Again

Part 7/? - The Curse of Madame Desrosiers

Part 8/? - Sabotage at Guedelon

Part 9/? - A Miracle

Part 10/? - Desrosiers’ Elixir

Part 11/? - Athens in October

Part 12/? - The Man in Black

Part 13/? - Mr. Neustadt

Part 14/? - The Other Side of the Story

Part 15/? - A Favour

Part 16/? - A Knock on the Window

Part 17/? - Sir Stephen and Buckeye

Part 18/? - Books of Alchemy

Part 19/? - The Answers

Part 20/? - A Gift Left Behind

Part 21/? - Santorini

Part 22/? - What the Doves Found

Part 23/? - A Thief in the Night

Part 24/? - Healing

Part 25/? - Newton’s Code

Part 26/? - Montenegro

Part 27/? - The Lost Relic

Part 28/? - The Homunculinus

Part 29/? - The End is Near

Part 30/? - The Face of Evil

Part 31/? - The Morning After

Part 32/? - Next Stop

Part 33/? - A Sighting in Messina

Part 34/? - Taormina

Part 35/? - Burning

Part 36/? - Recovery

Part 37/? - Pilgrimage to Vesuvius

Where has Newton gone next? It’s a pun.

By morning, the smoke had cleared and the volcano was quiet.

This was definitely not what anyone had expected. As the group ate breakfast in the hotel’s little restaurant, the news playing on the television above the bar was all about the sudden cessation of the eruption. An anchorwoman said in Italian, with rather poorly-translated English subtitles for the tourists, that scientists were puzzled but Etna seemed to have gone back to sleep. If the volcano remained quiescent for twenty-four hours, the evacuated Sicilians would be allowed to return to their homes on the slopes. There were interviews with several people who expressed their gratitude to God that their farms were not going to be destroyed, and their eagerness to go home.

“They did something,” said Sam, pointing a fork at the TV.

Natasha had been thinking the same thing. Desrosiers must have come here because she knew Newton would go to an erupting volcano to get geothermal energy from it… maybe that was where the enormous heat in his gauntlet had come from. Somehow, he’d convinced her to help him make the philosopher’s stone, and now that they had the notebooks, they’d returned to the volcano to drain the rest of its energy.

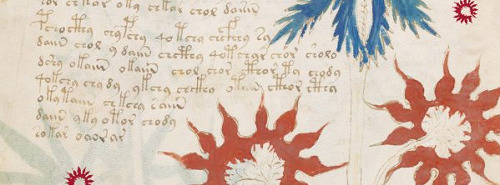

“Do they have everything they need now?” she wondered aloud. “Are they ready to just make the philosopher’s stone?” Maybe they were working on it right now, down in the bowels of the volcano… or would it still be too hot in there? “Where’s our Voynich book?”

Sharon pulled it out of Sir Stephen’s backpack. “We still can’t read it,” she said.

“Yeah, but there might be something to give us a hint,” said Nat.

That seemed pretty unlikely, even to Nat, but for the moment nobody had any better ideas. They flipped through the softcover facsimile. There were no pictures of volcanoes anywhere in the book, but Nat supposed any form of energy would do. Solar, geothermal, wind… ancient alchemists might have even tried to do it with fire. The Minoan alchemists on Santorini had used the volcanic heat of Thira. Heaven knew what Rasputin had found in the middle of Siberia, maybe one of the powerful Russian rivers. Of course, if Newton could drain energy from a volcano to store and move it, he could go anywhere he liked.

Even so, she was pretty confident now that Newton was not going to Australia. The simple fact that he’d gone out of his way to mention it seemed evidence enough of that. She glanced at the book again, as Sharon idly turned pages, and then something caught her eye.

“Wait,” said Nat, and turned back a page or two.

It was an illustration of a plant – this entire section of the book was drawings of plants. Notes in the margins said that botanists believed it might be a sunflower, which suggested that the book was about the plants of the Americas. Somebody had even offered the theory that its alphabet was an attempt to record a native American language in a way that would be intelligible to Europeans. But Natasha, thinking of volcanoes, had noticed something else.

Taormina was full of volcano-related souvenirs and merchandise right now, and as she and Jim had walked down the street yesterday, they’d seen multiple versions of an illustration showing a cross-section of the mountain. The posters, postcards, and t-shirts depicted many fissures branching off a big central well that brought lava to the surface, where it erupted from the vents and gave off steam that rose into a tower with billows at the top. Everything in alchemy was recorded in codes and metaphors. This was not botany. This was geology.

“Etna,” said Natasha. She put her finger at the top of the page, where a heading was written: five of the mysterious letters, the first and last the same. The name of the mountain in Greek was Aetna.

“No way,” said Sharon, turning the book to face her again. “Really?”

“Somebody get a pen,” Nat ordered.

A waitress was walking by. Jim snatched her notebook and pen from her. “Sorry, need this,” he said, and sat back down to copy out the four letters that were A, E, T, and N. These were fairly common letters in Greek, so they were soon able to get to work on the rest of the page. The results were disappointing: they found things that might have been words, but many more seemed like random groups of letters. Some were repeated multiple times, some appeared to be backwards or to have had the letters arranged in alphabetical order. There must be layers and layers of code and cipher here, Nat thought, and without the key they didn’t know what to look for where. Figuring it out might take years.

“If the sunflower is a diagram of the mountain,” Nat said, “maybe these labels are places to say where to best collect its energy for alchemical purposes.” Unfortunately, it was hardly a map to scale. Without being able to read the text, they couldn’t tell where to look for Newton and Desrosiers.

Sharon turned the page. There was another plant… was this one also a volcano? The second letter of its name was an E, but the rest weren’t ones they’d figured out. Nat counted them, and made some guesses. The headings were the most simply encoded parts, and letters one and five in this word were the same. If those were Greek beta, then the whole name might be…

“Vesuvius,” said Jim, before Nat could speak. “We gotta go to Mount Vesuvius.”

“Not necessarily,” said Sam. He reached over to flip a few more pages. “The Mediterranean’s full of volcanoes. What about Stromboli or Kolumbo?”

“No, he’ll go to Vesuvius,” said Jim. “I’m sure. Trust me.”

A piece suddenly fell into place. “He’s right,” said Nat. “He’s got to be.”

“You’re biased,” said Clint.

“No,” Nat insisted. “It’s a word game! Alchemy is all in puzzles, codes, and puns. Newton in German is Neustadt, and in Greek it’s Neapoli. That’s the area in Athens where his apartment was. What’s the city below Vesuvius?” she asked, and waited expectantly. One by one, she saw her companions’ expressions change as the light dawned.

“All right,” said Sam, as Sharon closed the book. “Naples.”

With the evacuees returning in droves, it was no problem to get a ferry to the mainland. In Calabria they got on a train heading north to Termini in Rome, where they transferred to one bound for Naples.

It was a hot day when they arrived, but it wasn’t like the pounding dry heat of Santorini or Athens. Naples was drowning in a thick, humid heat that sweating did nothing to help because there was no wind to make it evaporate. Locals didn’t seem to mind, but the tourists walked around fanning themselves, their faces red and glistening from exertion. Shops selling bottled water and gelato did very brisk business.

They reached Naples late in the afternoon, and as the train entered the city they could see a cruise ship in port. Nat caught Clint peering at it, trying to figure out whether it was a familiar one.

“It’s not,” she said. “Wrong company. See the logo on the superstructure?”

Clint nodded and looked back down at the screen of his phone. He’d just typed in the question would you like anything from Naples? A flashing icon suggested that Laura Francis, back home in Nottinghamshire, was typing her reply.

“What are you looking for?” asked Sam.

“I don’t know yet,” said Clint. “She hasn’t answered.”

“No,” Sam said, “I mean, why were you looking at the boat?”

“He thinks the Scorpio II is following us,” said Nat.

Clint shook his head. “Next time we are definitely doing this on a cruise ship,” he said. “If I’m going to hop from island to island around the Mediterranean without ever having time to stop and see anything, I’m gonna do it with room service.”

“Foot massages,” said Sharon.

“Wi-fi,” said Natasha.

“Cold beer,” Jim agreed.

“That’s it.” Sharon nodded. “When we get back, we’re telling Fury and the Queen that from now on we only travel by cruise ship.”

Nat grinned as she imagined that conversation. Fury would roll his eye, fully aware that they were joking and determined not to dignify it with an acknowledgement. The Queen, on the other hand, might just take them seriously. She spent her own vacations in Monte Carlo and a series of palaces, so why not?

Clint’s phone vibrated. He took a look. “Oh, great,” he groaned.

“What’s it say?” asked Nat.

He turned the phone around to show them. Laura’s reply said simply, surprise me.

Sam whistled. “You’re being tested now, my man,” he declared.

“I know,” Clint said. “And I don’t think one of those glitter-covered panda figures is going to do it.”

The moment they stepped out of Napoli Centrale, they were bombarded by vendors offering them tours and trinkets. Nat kept her head down and tried not to make eye contact, but she did have to look where she was going and the Neapolitans were happy to follow the group out into the street. Brochures, maps, hats, and sunglasses were all thrust into her face in quick succession, and it was very difficult to keep a hold on the instinct telling her to throw these people across the road.

“I have changed my mind,” Sir Stephen announced, as they shooed the last of them away.

“About what?” asked Sharon.

“About whether this is like going on pilgrimage,” he said, and turned to wave away a man offering tour tickets. “No, thank you, Sir, we do not want to visit Positano!” Returning his attention to Sharon, he went on: “this is exactly the sort of thing that greets a pilgrim in Canterbury.”

“Canterbury didn’t become a place of pilgrimage until the late twelfth century,” said Natasha, but she wasn’t going to worry about it much. Sir Stephen’s world was not one that concerned itself with historical accuracy.

From the city, there was a clear view of Mount Vesuvius. Mount Etna in Sicily was surrounded by other peaks, all of which had once been exit points for the volcano but were now extinct. Vesuvius stood alone. From this angle only one of its two cones was visible, covered with green woods all the way to the snow line. There hadn’t been a major eruption since 1944, leaving the vegetation plenty of time to recolonize the slopes.

Even so, the mountain looked almost exactly like how a child might draw a picture of a volcano: a steep conical hill with a crater in the top. Nat had to wonder how the people of Pompeii and Herculaneum had ever thought this was a good place to live. Then again, she observed, here they were nearly two thousand years later, with people still living in Naples and Sorrento. The very reason this city was called Napoli was because it was the New City, founded after an eruption had destroyed the older one.

Volcanic soil was excellent for wine grapes. Maybe in Italy, that was enough to make people stay.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

true friends don’t judge each other/ they judge other people/ together - the Blackfyre power couple & Aegor fit the bill

Ok but this is literally everything tho?

So Daemon Blackfyre was outwardly polite and charming to everyone he met, from the bastard-suspicious Peakes to the anti-Targaryen Yronwoods and Aegor Rivers. Part of charm is tact, which means not bluntly speaking your opinions of people to their/their allies' faces. Add this to the fact that Aegon IV was a narcissist (For the anti-Blackfyres reading this, please look up "narcissistic parenting" and apply the list of traits to Aegon IV's relationships with Daeron, Daemon, and Aegor. Then tell me exactly how Daemon was spoiled as a child) and Daemon's official father during his most petty and paranoid phase of life, and Daemon most certainly had a high tolerance for awful behavior. After spending time with a sadistic rapist who had his own son's family executed, Daemon must've been able to put on a courteous façade for anyone no matter how morally reprehensible he found them (and someone as personally invested in the code of chivalry as Daemon would've thought poorly of Gormon Peake framing/torturing bastards). If anyone is wondering how Daemon could've possibly been on friendly terms with such difficult men as Brynden and Aegor Rivers, it may be because he rationalized many of their harsh actions as well-intentioned or "not that bad." That's not to say he never criticized them (especially Aegor, who he didn't know as a child), but that he often kept his judgments to himself.

Contrast this permissive attitude with Aegor's bluntness. Aegor didn't grow up in King's Landing during Aegon IV's late reign, where one misspoken word could get someone banished or executed. He disagreed with two of Daemon's powerful supporters, Gormon Peake and Ambrose Butterwell, about their plan to crown Daemon II and refused to be cowed by them (I'm somewhat inclined to think that Peake's suspicion of bastards may've partially been due to Aegor's "unreliability"); instead, he kept company with the anti-Targaryen Yronwoods (who had ample reason to hate the Reachmen after Daeron I's war) and his fellow Riverlanders the Shawneys, which must've aggravated Peake to no end. In addition, one of the few things we know for sure about his grandfather and mother Barba was that they spoke their minds even when it wasn't proper or advantageous to them (Lord Bracken wanting Barba to be Queen, Barba allegedly calling Melissa flat). Given that he identified more with the Brackens who raised him, I'm inclined to think he inherited their lack of tact in social situations (which frustrated Daemon to no end), and was open about his hatred for the Targaryens, his contempt for some of Daemon's fair-weather allies, and his preference for fellow court outsiders.

Rohanne was likely somewhere in the middle when it came to openness of opinions. As an upper-class woman, she likely had training in etiquette, but was almost certainly more outspoken than the ideal Westerosi lady. Like Aegor, she didn't grow up in King's Landing with Aegon IV's flatterers, but in mercantile Tyrosh. In real life, wealth-based societies tended to give more rights to elite women than militaristic ones (for example, the ancient Egyptians and Minoans allowed women to hold their own property and sue for divorce, which the military-minded Assyrians and Romans didn't); one of the justifications for Westerosi patriarchy, that of fighting, doesn't exist in Tyrosh because most of their elite men didn't fight either. Lending some credence to Tyroshi women having more respect is that the Archon of Tyrosh fostered his own daughter at the distant Water Gardens without having betrothed her to Quentyn or having her wait on Arianne, when in Westeros this type of fostering seems to be restricted to boys; it seems she was supposed to have served Doran personally (she was a swap for Arianne, who was to be the Archon's cupbearer), indicating that girls were seen as capable of being fostered with and worthy of serving male heads of state. So Rohanne came from a society that valued their daughters more than they did in Westeros. She's also a woman who immigrated to a society incredibly suspicious of foreigners (no, not just the Dornish. Larra Rogare, Serala and Taena of Myr, Serenei of Lys, and Tyanna of Pentos were all from the Free Cities married/mistress to wealthy Westerosi noblemen/kings/princes, and justified or not were all treated with contempt and wariness by a lot of the court). So the Westerosi lords and ladies may have considered her too outspoken, too commercially-minded, and too Tyroshi to be an ideal Westerosi noblewoman. It seems she succeeded in charming a few of them (the Webbers did name their daughter Rohanne two years after her wedding), but ultimately they ignored her legacy in favor of a rumor involving Princess Daenerys; it must've been frustrating to have tried to please your adopted people only to be faulted for something you couldn't change. I'm sure she was active and opinionated for a lady, and while that won her some friends (Aegor her fellow outsider, perhaps Daemon's own financially successful aunt Elaena), she was still controversial.

So what happens when a gentle-speaking knight with a strong moral code, a blunt pugilist with iron conviction, and a headstrong lady from an outspoken culture get together for a roasting session? Comedy gold! But also important character development. Daemon learns to speak his mind about others more, which gives him the confidence to do what he feels is right rather than what'll please others. Aegor learns more about proper court behavior and customs that he'll need to navigate Daeron's echo-chamber alone. Rohanne gets to vent her frustrations about the Westerosi elite that place constant demands on her, maybe even learning how to speak courteously but still getting her point across.

So yeah, judgment time with Aegor, Rohanne, and Daemon. Good stuff!

#ask#asoiaf#Daemon Blackfyre#Rohanne of Tyrosh#Aegor Rivers#asoiaf headcanon#fanfic ideas#bittersteel

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lentoid seal with a lioness attacking a bull

Early Aegean, Minoan

Bronze Age, Late Minoan II Period

about 1470–1410 BCE

“The bull has an open mouth and protruding tongue. Careful modeling. Outlined bodies. Round drill used for eyes, joints and teats.”

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

166 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Late Minoan II/IIIA1 complete piriform jar of medium size [Credit: Dept. of Antiquities, Republic of Cyprus]

(via The Archaeology News Network)

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

Mesopotamia is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent, in modern days roughly corresponding to most of Iraq, Kuwait, the eastern parts of Syria, Southeastern Turkey, and regions along the Turkish–Syrian and Iran–Iraq borders.[1]

The Sumerians and Akkadians (including Assyrians and Babylonians) dominated Mesopotamia from the beginning of written history (c. 3100 BC) to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, when it was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire. It fell to Alexander the Great in 332 BC, and after his death, it became part of the Greek Seleucid Empire.

Around 150 BC, Mesopotamia was under the control of the Parthian Empire. Mesopotamia became a battleground between the Romans and Parthians, with western parts of Mesopotamia coming under ephemeral Roman control. In AD 226, the eastern regions of Mesopotamia fell to the Sassanid Persians. The division of Mesopotamia between Roman (Byzantine from AD 395) and Sassanid Empires lasted until the 7th century Muslim conquest of Persia of the Sasanian Empire and Muslim conquest of the Levant from Byzantines. A number of primarily neo-Assyrian and Christian native Mesopotamian states existed between the 1st century BC and 3rd century AD, including Adiabene, Osroene, and Hatra.

Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10,000 BC. It has been identified as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history, including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops and the development of cursive script, mathematics, astronomy and agriculture".[2]

Etymology

The regional toponym Mesopotamia (/ˌmɛsəpəˈteɪmiə/, Ancient Greek: Μεσοποταμία "[land] between rivers"; Arabic: بلاد الرافدين، بین النهرین bilād ar-rāfidayn; Persian: میانرودان miyān rudān; Syriac: ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪܝܢ Beth Nahrain "land of rivers") comes from the ancient Greek root words μέσος (mesos) "middle" and ποταμός (potamos) "river" and translates to "(Land) between two/the rivers". It is used throughout the Greek Septuagint (c. 250 BC) to translate the Hebrew and Aramaic equivalent Naharaim. An even earlier Greek usage of the name Mesopotamia is evident from The Anabasis of Alexander, which was written in the late 2nd century AD, but specifically refers to sources from the time of Alexander the Great. In the Anabasis, Mesopotamia was used to designate the land east of the Euphrates in north Syria.

The Aramaic term biritum/birit narim corresponded to a similar geographical concept.[3] Later, the term Mesopotamia was more generally applied to all the lands between the Euphrates and the Tigris, thereby incorporating not only parts of Syria but also almost all of Iraq and southeastern Turkey.[4] The neighbouring steppes to the west of the Euphrates and the western part of the Zagros Mountains are also often included under the wider term Mesopotamia.[5][6][7]

A further distinction is usually made between Northern or Upper Mesopotamia and Southern or Lower Mesopotamia.[8] Upper Mesopotamia, also known as the Jazira, is the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris from their sources down to Baghdad.[5] Lower Mesopotamia is the area from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf and includes Kuwait and parts of western Iran.[8]

In modern academic usage, the term Mesopotamia often also has a chronological connotation. It is usually used to designate the area until the Muslim conquests, with names like Syria, Jazira, and Iraq being used to describe the region after that date.[4][9] It has been argued that these later euphemisms are Eurocentric terms attributed to the region in the midst of various 19th-century Western encroachments.[9][10]

Geography

Main article: Geography of Mesopotamia

Known world of the Mesopotamian, Babylonian, and Assyrian cultures from documentary sources

Mesopotamia encompasses the land between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, both of which have their headwaters in the Taurus Mountains. Both rivers are fed by numerous tributaries, and the entire river system drains a vast mountainous region. Overland routes in Mesopotamia usually follow the Euphrates because the banks of the Tigris are frequently steep and difficult. The climate of the region is semi-arid with a vast desert expanse in the north which gives way to a 15,000-square-kilometre (5,800 sq mi) region of marshes, lagoons, mud flats, and reed banks in the south. In the extreme south, the Euphrates and the Tigris unite and empty into the Persian Gulf.

The arid environment which ranges from the northern areas of rain-fed agriculture to the south where irrigation of agriculture is essential if a surplus energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) is to be obtained. This irrigation is aided by a high water table and by melting snows from the high peaks of the northern Zagros Mountains and from the Armenian Highlands, the source of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that give the region its name. The usefulness of irrigation depends upon the ability to mobilize sufficient labor for the construction and maintenance of canals, and this, from the earliest period, has assisted the development of urban settlements and centralized systems of political authority.

Agriculture throughout the region has been supplemented by nomadic pastoralism, where tent-dwelling nomads herded sheep and goats (and later camels) from the river pastures in the dry summer months, out into seasonal grazing lands on the desert fringe in the wet winter season. The area is generally lacking in building stone, precious metals and timber, and so historically has relied upon long-distance trade of agricultural products to secure these items from outlying areas. In the marshlands to the south of the area, a complex water-borne fishing culture has existed since prehistoric times, and has added to the cultural mix.

Periodic breakdowns in the cultural system have occurred for a number of reasons. The demands for labor has from time to time led to population increases that push the limits of the ecological carrying capacity, and should a period of climatic instability ensue, collapsing central government and declining populations can occur. Alternatively, military vulnerability to invasion from marginal hill tribes or nomadic pastoralists has led to periods of trade collapse and neglect of irrigation systems. Equally, centripetal tendencies amongst city states has meant that central authority over the whole region, when imposed, has tended to be ephemeral, and localism has fragmented power into tribal or smaller regional units.[11] These trends have continued to the present day in Iraq.

History

Main article: History of Mesopotamia

Further information: History of Iraq, History of the Middle East, and Chronology of the ancient Near East

The pre-history of the Ancient Near East begins in the Lower Paleolithic period. Therein, writing emerged with a pictographic script in the Uruk IV period (c. 4th millennium BC), and the documented record of actual historical events — and the ancient history of lower Mesopotamia — commenced in the mid-third millennium BC with cuneiform records of early dynastic kings. This entire prehistory ends with either the arrival of the Achaemenid Empire in the late 6th century BC, or with the Muslim conquest and the establishment of the Caliphate in the late 7th century AD, from which point the region came to be known as Iraq. In the long span of this period, Mesopotamia housed some of the world's most ancient highly developed and socially complex states.

The region was one of the four riverine civilizations where writing was invented, along with the Nile valley in Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization in the Indian subcontinent, and the Yellow River in China. Mesopotamia housed historically important cities such as Uruk, Nippur, Nineveh, Assur and Babylon, as well as major territorial states such as the city of Eridu, the Akkadian kingdoms, the Third Dynasty of Ur, and the various Assyrian empires. Some of the important historical Mesopotamian leaders were Ur-Nammu (king of Ur), Sargon of Akkad (who established the Akkadian Empire), Hammurabi (who established the Old Babylonian state), Ashur-uballit II and Tiglath-Pileser I (who established the Assyrian Empire).

Scientists analysed DNA from the 8,000-year-old remains of early farmers found at an ancient graveyard in Germany. They compared the genetic signatures to those of modern populations and found similarities with the DNA of people living in today's Turkey and Iraq.[12]

Periodization

Pre- and protohistory

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (10,000–8700 BC)

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (8700–6800)

Jarmo (7500-5000 BC), Hassuna (~6000 BC–? BC), Samarra (~5700–4900 BC) and Halaf cultures(~6000–5300 BC) cultures

Ubaid period (~5900–4400 BC)

Uruk period (~4400–3100 BC)

Jemdet Nasr period (~3100–2900 BC)[13]

Early Bronze Age

Early Dynastic period (~2900–2350 BC)

Akkadian Empire (~2350–2100 BC)

Third Dynasty of Ur (2112–2004 BC)

Early Assyrian kingdom (24th to 18th century BC)

Middle Bronze Age

Early Babylonia (19th to 18th century BC)

First Babylonian dynasty (18th to 17th century BC)

Minoan eruption (c. 1620 BC)

Late Bronze Age

Old Assyrian period (16th to 11th century BC)

Middle Assyrian period (c. 1365–1076 BC)

Kassites in Babylon, (c. 1595–1155 BC)

Late Bronze Age collapse (12th to 11th century BC)

Iron Age

Syro-Hittite states (11th to 7th century BC)

Neo-Assyrian Empire (10th to 7th century BC)

Neo-Babylonian Empire (7th to 6th century BC)

Classical antiquity

Persian Babylonia, Achaemenid Assyria (6th to 4th century BC)

Seleucid Mesopotamia (4th to 3rd century BC)

Parthian Babylonia (3rd century BC to 3rd century AD)

Osroene (2nd century BC to 3rd century AD)

Adiabene (1st to 2nd century AD)

Hatra (1st to 2nd century AD)

Roman Mesopotamia (2nd to 7th centuries AD), Roman Assyria (2nd century AD)

Late Antiquity

Palmyrene Empire (3nd century AD)

Asōristān (3rd to 7th century AD)

Euphratensis (mid-4th century AD to 7th century AD)

Muslim conquest (mid-7th century AD)

Science and technology

Mathematics

Main article: Babylonian mathematics

Mesopotamian mathematics and science was based on a sexagesimal (base 60) numeral system. This is the source of the 60-minute hour, the 24-hour day, and the 360-degree circle. The Sumerian calendar was based on the seven-day week. This form of mathematics was instrumental in early map-making. The Babylonians also had theorems on how to measure the area of several shapes and solids. They measured the circumference of a circle as three times the diameter and the area as one-twelfth the square of the circumference, which would be correct if pi were fixed at 3. The volume of a cylinder was taken as the product of the area of the base and the height; however, the volume of the frustum of a cone or a square pyramid was incorrectly taken as the product of the height and half the sum of the bases. Also, there was a recent discovery in which a tablet used pi as 25/8 (3.125 instead of 3.14159~). The Babylonians are also known for the Babylonian mile, which was a measure of distance equal to about seven modern miles (11 km). This measurement for distances eventually was converted to a time-mile used for measuring the travel of the Sun, therefore, representing time.[20]

Astronomy

Main article: Babylonian astronomy

From Sumerian times, temple priesthoods had attempted to associate current events with certain positions of the planets and stars. This continued to Assyrian times, when Limmu lists were created as a year by year association of events with planetary positions, which, when they have survived to the present day, allow accurate associations of relative with absolute dating for establishing the history of Mesopotamia.

The Babylonian astronomers were very adept at mathematics and could predict eclipses and solstices. Scholars thought that everything had some purpose in astronomy. Most of these related to religion and omens. Mesopotamian astronomers worked out a 12-month calendar based on the cycles of the moon. They divided the year into two seasons: summer and winter. The origins of astronomy as well as astrology date from this time.

During the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Babylonian astronomers developed a new approach to astronomy. They began studying philosophy dealing with the ideal nature of the early universe and began employing an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. This was an important contribution to astronomy and the philosophy of science and some scholars have thus referred to this new approach as the first scientific revolution.[21] This new approach to astronomy was adopted and further developed in Greek and Hellenistic astronomy.

In Seleucid and Parthian times, the astronomical reports were thoroughly scientific; how much earlier their advanced knowledge and methods were developed is uncertain. The Babylonian development of methods for predicting the motions of the planets is considered to be a major episode in the history of astronomy.

The only Greek-Babylonian astronomer known to have supported a heliocentric model of planetary motion was Seleucus of Seleucia (b. 190 BC).[22][23][24] Seleucus is known from the writings of Plutarch. He supported Aristarchus of Samos' heliocentric theory where the Earth rotated around its own axis which in turn revolved around the Sun. According to Plutarch, Seleucus even proved the heliocentric system, but it is not known what arguments he used (except that he correctly theorized on tides as a result of Moon's attraction).

Babylonian astronomy served as the basis for much of Greek, classical Indian, Sassanian, Byzantine, Syrian, medieval Islamic, Central Asian, and Western European astronomy.[25]

Technology

Mesopotamian people invented many technologies including metal and copper-working, glass and lamp making, textile weaving, flood control, water storage, and irrigation. They were also one of the first Bronze Age societies in the world. They developed from copper, bronze, and gold on to iron. Palaces were decorated with hundreds of kilograms of these very expensive metals. Also, copper, bronze, and iron were used for armor as well as for different weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, and maces.

According to a recent hypothesis, the Archimedes' screw may have been used by Sennacherib, King of Assyria, for the water systems at the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and Nineveh in the 7th century BC, although mainstream scholarship holds it to be a Greek invention of later times.[30] Later, during the Parthian or Sasanian periods, the Baghdad Battery, which may have been the world's first battery, was created in Mesopotamia.[31]

Religion and philosophy

Main article: Ancient Mesopotamian religion

Ancient Mesopotamian religion was the first recorded. Mesopotamians believed that the world was a flat disc,[32] surrounded by a huge, holed space, and above that, heaven. They also believed that water was everywhere, the top, bottom and sides, and that the universe was born from this enormous sea. In addition, Mesopotamian religion was polytheistic. Although the beliefs described above were held in common among Mesopotamians, there were also regional variations. The Sumerian word for universe is an-ki, which refers to the god An and the goddess Ki.[33][citation needed] Their son was Enlil, the air god. They believed that Enlil was the most powerful god. He was the chief god of the pantheon. The Sumerians also posed philosophical questions, such as: Who are we?, Where are we?, How did we get here?.[citation needed] They attributed answers to these questions to explanations provided by their gods.

Philosophy

The numerous civilizations of the area influenced the Abrahamic religions, especially the Hebrew Bible; its cultural values and literary influence are especially evident in the Book of Genesis.[34]

Giorgio Buccellati believes that the origins of philosophy can be traced back to early Mesopotamian wisdom, which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ethics, in the forms of dialectic, dialogues, epic poetry, folklore, hymns, lyrics, prose works, and proverbs. Babylonian reason and rationality developed beyond empirical observation.[35]

The earliest form of logic was developed by the Babylonians, notably in the rigorous nonergodicnature of their social systems. Babylonian thought was axiomatic and is comparable to the "ordinary logic" described by John Maynard Keynes. Babylonian thought was also based on an open-systemsontology which is compatible with ergodic axioms.[36] Logic was employed to some extent in Babylonian astronomy and medicine.

Babylonian thought had a considerable influence on early Ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophy. In particular, the Babylonian text Dialogue of Pessimism contains similarities to the agonistic thought of the Sophists, the Heraclitean doctrine of dialectic, and the dialogs of Plato, as well as a precursor to the Socratic method.[37] The Ionian philosopher Thales was influenced by Babylonian cosmological ideas.

Culture

Festivals

Ancient Mesopotamians had ceremonies each month. The theme of the rituals and festivals for each month was determined by at least six important factors:

The Lunar phase (a waxing moon meant abundance and growth, while a waning moon was associated with decline, conservation, and festivals of the Underworld)

The phase of the annual agricultural cycle

Equinoxes and solstices

The local mythos and its divine Patrons

The success of the reigning Monarch

The Akitu, or New Year Festival (First full moon after spring equinox)

Commemoration of specific historical events (founding, military victories, temple holidays, etc.)

0 notes

Photo

Bull's head rhyton from the Palace of Knossos (black steatite, with horns of gilded wood, eyes of inlaid rock crystal and jasper and nostrils of mother-of-pearl). Late Minoan II period (1450 BC.). Herakleion Archeological Museum, Crete

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is a labyrinth for?

I've been reading House of Leaves for the last ~7 months. I'm interested, but not engaged: all those months of toil and I'm still only 300 pages in (it is really tempting to just read the Wikipedia summary). The book is about a house which is bigger on the inside than on the outside. People find a mysterious passage which leads to endless hallways, rooms leading to more rooms. An expedition is mounted and the group spend close to two weeks exploring the insides of the house's walls. It takes them four days to descend a staircase. They never find the outside, the house never ends. And as the story goes on the house becomes increasingly hostile and it’s driving people crazy, floors are spontaneously opening up and swallowing unsuspecting alcoholics down into bottomless pits.

Throughout the book (or, really, throughout the bit I've read so far - haha how many book reports have been authored by people who have only read a fraction of the book?) there are lots of references to labyrinths and their purpose. Such a cool word - what's the meaning of 'lab'? Labyrith = misspelt start to labia? That would be interesting. Fingers crossed that that's an upcoming twist in HoL. Okay: the etymology - Online Etymology Dictionary:

c. 1400, laberynthe (late 14c. in Latinate form laborintus) "labyrinth, maze, great building with many corridors and turns,"figuratively "bewildering arguments," from Latin labyrinthus, from Greek labyrinthos "maze, large building with intricate passages," especially the structure built by Daedelus to hold the Minotaur, near Knossos in Crete, a word of unknown origin.

A word of unknown origin... Spooky. They go on:

Apparently from a pre-Greek language; traditionally connected to Lydian labrys "double-edged axe," symbol of royal power, which fits with the theory that the original labyrinth was the royal Minoan palace on Crete. It thus would mean "palace of the double-axe." But Beekes finds this "speculative" and compares laura "narrow street, narrow passage, alley, quarter," also identified as a pre-Greek word. Used in English for "maze" early 15c., and in figurative sense of "confusing state of affairs" (1540s). As the name of a structure of the inner ear, the essential organ of hearing, from 1690s.

This is definitely irrelevant, but in Homer, Odysseus’ stock epithet is ‘cunning’ - the first lines of The Odyssey are: “Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns.” Is this twists and turns because he’s cunning and able to confound people with his ‘figuratively bewildering arguments’ - or is this twists and turns because he’s a terrible navigator and we’re about to hear all about his epic, decade-long journey home from Troy?

Anyway, kind of feels pointless to tell the story of the Minotaur and his labyrinth because you definitely already know it, but just briefly:

Tale as old as time,

True as it can be,

Blah blah blaaaah

Beauty and the beast

After some funny business between Poseidon and Minos (the king of Crete), the queen (Minos’ wife - and also the daughter of Helios, the sun) falls in love with a bull which was originally given to Minos by Poseidon under the proviso that he (Minos) would sacrifice it to honour Poseidon (sweet deal). Anyway, the queen is totally besotted with this bull and decides she wants to kick things up a gear sexually so she has Daedalus (of wax wings fame) make a hollow fake cow so she can get banged by the bull (what could go wrong?). She winds up pregnant and gives birth to the Minotaur - the queen tries to raise him right but he is savage. Because he’s a monstrosity, he had no natural food source and settles upon humans as his food of choice.

Minos commissions Daedalus to build a labyrinth (I presume the Cretan royalty had some kind of family discount plan) and they shove the Minotaur in there. Why didn’t Minos just kill the Minotaur? The oracle at Delphi said not to. Plus, I guess it might have upset his wife a bit. Why didn’t Minos just kill Daedalus? That’d be too easy. It seems like at the core of most myths there’s a kernel of morality tale:

For Daedalus: just because you can doesn’t mean you should - be more careful about the stuff you build. And don’t enable bestiality

For Minos: don’t sass Poseidon

For the queen: typical Greek stuff - all women (even the daughters of the sun god) are depraved liars with bizzareo sexual leanings. Even though it was a curse from Poseidon that gave her those impulses, her shame echoes through eternity (which is weirdly her only cosmic punishment - besides, I guess, being separated from her one true love, the bull... actually, I’m not sure what happened there. One assumes that after the Minotaur thing she decided to hit the brakes on her relationship with the bull but maybe they grew old together, lying in the sun in grassy pastures for the rest of their lives)

If you were hoping that this was the only tale of lady/bull romance from ancient Greece, you are shit out of luck. In another story from Crete, ya boy Zeus takes a fancy to a woman named Europa. Rather than woo her using any of the conventional means, Zeus transforms into a huge white bull and abducts her, taking her to the island of Crete. She becomes Crete’s first queen and has some kids with Zeus - it’s unclear whether this goes down with Zeus in bull or human form. It transpires that one of the kids born from Europa’s affair with Zeus is Minos. So Minos’ mother and wife both had unsavoury relationships with bulls.

That was a long detour - getting back to the Labyrinth: it was built in Crete to house the Minotaur. The idea was that the Minotaur would never be able to escape, and that anyone who entered the Labyrinth wouldn’t be able to escape either. Why not just lock the Minotaur in a prison? Doesn’t have the same ring to it, I guess. It’s a weird idea though, isn’t it - making a really complicated (but still solvable) puzzle and putting something you never want found or freed in it. Why not just make something actually unsolvable?

So that’s the first/most famous labyrinth. Herodotus, a Greek historian who was kicking around in the 5th century BC also wrote about one in Egypt. He wrote a book called Histories which Wikipedia bills as the founding work of history in the Western literary canon (I initially misread this sentence and thought that they were saying it was the founding work overall and I was about to be all ‘ah, beaucoup problemo, Wikipedia.’ But a quick reread saves me from from making an embarrassing mistake). ANYWAY, in the second volume of Histories, Herodotus recounts his travels around the far flung and exotic land of Egypt. According to Herodotus:

This I have actually seen, a work beyond words. For if anyone put together the buildings of the Greeks and display of their labours, they would seem lesser in both effort and expense to this labyrinth… Even the pyramids are beyond words, and each was equal to many and mighty works of the Greeks. Yet the labyrinth surpasses even the pyramids.

Ancient Origins dot net says:

It was named ‘Labyrinth’ by the Greeks after the complex maze of corridors designed by Daedalus for King Minos of Crete, where the legendary Minotaur dwelt. Yet today, nothing remains of this supposedly grand temple complex – at least not on the surface. The mighty labyrinth became lost to the pages of history.

It was actually a mortuary temple, not a labyrinth in the traditional sense of looking like a maze, but it was sprawling, complex and difficult to navigate.The only other Greek historian to see it was Strabo. He was kicking around ~500 years after Herodotus but also reported that the labyrinth was pretty crazy, calling it a “great palace composed of many palaces.” He said:

[I]n front of the entrances are crypts, as it were, which are long and numerous and have winding passages communicating with one another, so that no stranger can find his way either into any court or out of it without a guide.

Apparently the temple was lost over time - Wikipedia is blaming Ptolemy II (who apparently married his sister so that gives you a sense of his respect for preserving the integrity of things like historical sites and the integrity of blood lines) for its ‘demolition’ but he died in 246 BCE so, if he’d destroyed it, how would Strabo have been able to see it in the 1st century CE? It may not have been completely destroyed - it sounds like they perhaps just removed a bunch of limestone columns and blocks.

Fast forward to 1888: a British archaeologist named Flinders Petrie is excavating the site - of his findings he writes: there was nothing but a “vast field of chipped stone, six feet deep... All over an immense area of dozens of acres, I found evidence of a grand building. From such very scanty remains it is hard to settle anything." Petrie also apparently found a bunch of papyrus scrolls - including some which contain parts of the Illiad!

So there was definitely something there. Imagine this though: people found Herodotus’ writings ages ago and are searching around in the sand based on 2,000+ year old testimony from a man who many of his contemporaries considered at best a gullible exaggerator and at worst a liar.

There was an expedition in 2008 - they have a website talking up their geophysic surveys of the area but they might not have found much because the results page of their website was never completed.