#latin american literature

Text

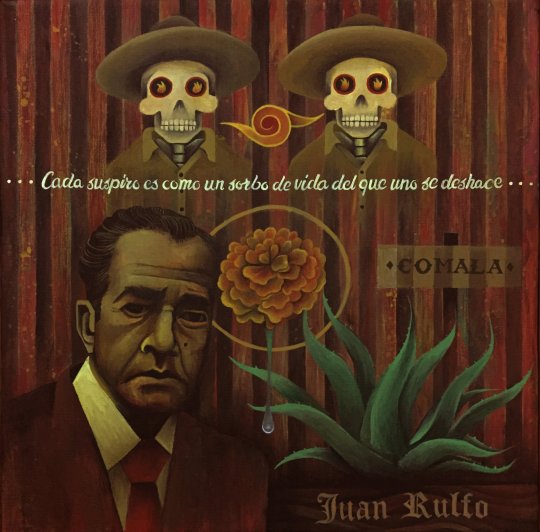

The Mexican writer Juan Rulfo (1917-86) with an Aztec skull.

A Masterpiece That Inspired Gabriel García Márquez to Write His Own

For decades, Juan Rulfo’s novel, “Pedro Páramo,” has cast an uncanny spell on writers. A new translation may bring it broader appeal.

NYT

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science Fiction From Latin America, With Zombie Dissidents and Aliens in the Amazon

A new wave of writers is making the genre its own, rooting it in local homelands and histories.

By Emily Hart

A spaceship lands near a small town in the Amazon, leaving the local government to manage an alien invasion. Dissidents who disappeared during a military dictatorship return years later as zombies. Bodies suddenly begin to fuse upon physical contact, forcing Colombians to navigate newly dangerous salsa bars and FARC guerrillas who have merged with tropical birds.

Across Latin America, shelves labeled “ciencia ficción,” or science fiction, have long been filled with translations of H.P. Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, William Gibson and H.G. Wells. Now they might have to compete with a new wave of Latin American writers who are making the genre their own, rerooting it in their homelands and histories. Shrugging off rolling cornfields and New York skylines, they set their stories against the dense Amazon, craggy Andean mountainscapes and unmistakably Latin American urban sprawl.

The avalanche of original science fiction is timely, arriving as many readers and writers in Latin America feel choked by the folksy tropes of magical realism and desensitized by realist depictions of the region’s struggles with violence.

READ MORE

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

– Isabel Allende, The House of the Spirits

#*#words#writing#typography#isabel allende#la casa de los espíritus#the house of the spirits#literature#latin american literature#annual christmas post#for the first time here on tumblr actually

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

... el alma se le cristalizó con la nostalgia de los sueños perdidos. Se sintió tan vieja, tan acabada, tan distante de las mejores horas de su vida, que inclusive añoro las que recordaba como las peores

Gabriel García Márquez, Cien años de soledad

#gabo#gabriel garcia marquez#colombia#gabriel garcía márquez#realismo magico#realismo mágico#estoy leyendo#literature blog#literatura en español#cien años de soledad#citas de libros#caribbean art#caribbean literature#latin american literature#literatura latina#blog de literatura#realismo fantastico#realismo fantástico#saudade

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh to be a spectacularly beautiful bride-to-be in 19th century South America, with nearly mermaid like features—ivory skin and green hair. To pass the days embroidering wild beasts that defy the laws of nature and aerodynamics on the longest tablecloth in the world. To turn heads as I walk down the street, to be bathed in beams of light from the stain-glassed windows in mass. Completely unaware of my beauty. Awaiting my fiancé seeking his fortune in the Atacama desert, picturing him on unrealistic adventures in steel-toed boots. Watching my younger sister, accompanied by her dog the size of a horse, communicate with the spirits of the dead and move salt cellars across the table with her mind.

#house of the spirits#the house of the spirits#la casa de los espíritus#isabel allende#Chile#historical fiction#history#9/11/73#magical realism#spiritism#aesthetic#latin american literature

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

mario vargas llosa in "writers at work: the paris review interview series (ninth edition)"

#not gonna link it but i got the pdf from zl*b if you need#in fact just dm me and i will send it to you if you need!#mario vargas llosa#literature#writing#inspiration#self discipline#creative writing#latin american literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selva Almada

youtube

Selva Almada was born in 1973 in Villa Elisa, Argentina. Almada is regarded as one of the most powerful voices in contemporary Argentine and Latin American literature. Her first novel The Wind That Lays Waste was nominated for Argentinian Book of the Year upon its publication in 2012. In 2019, when it was published in English, it won the Edinburgh International Book Festival's First Book Award. Almada has been compared to William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, and Flannery O'Connor. She has been a finalist for the Tigre Juan Award, the Rodolfo Walsh Award, shortlisted for the Vargas Llosa Prize for Novels, and longlisted for the International Booker Prize. Almada's work has been translated into several languages, including Portuguese, French, Turkish, Swedish, and Italian.

#writers#woman writers#authors#books#argentina#latin america#latin american literature#latina#hispanic#south america#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

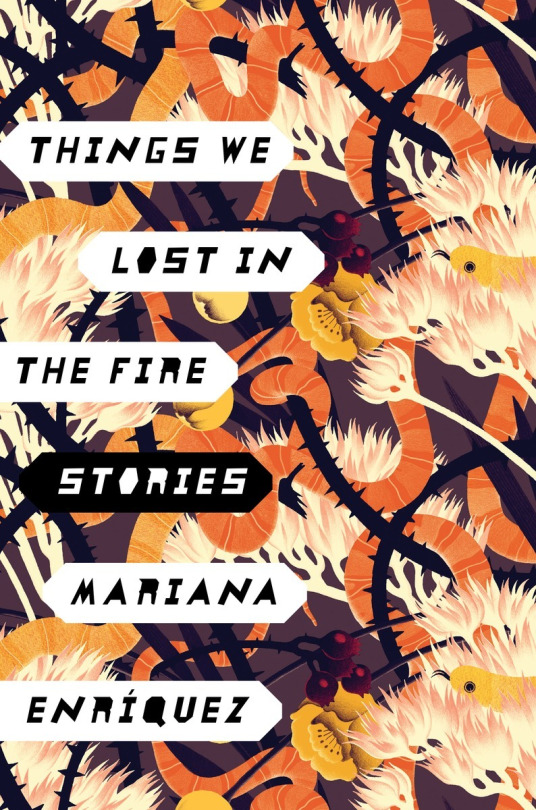

Have you read...

In these wildly imaginative, devilishly daring tales of the macabre, internationally bestselling author Mariana Enriquez brings contemporary Argentina to vibrant life as a place where shocking inequality, violence, and corruption are the law of the land, while military dictatorship and legions of desaparecidos loom large in the collective memory. In these stories, reminiscent of Shirley Jackson and Julio Cortázar, three young friends distract themselves with drugs and pain in the midst a government-enforced blackout; a girl with nothing to lose steps into an abandoned house and never comes back out; to protest a viral form of domestic violence, a group of women set themselves on fire.

But alongside the black magic and disturbing disappearances, these stories are fueled by compassion for the frightened and the lost, ultimately bringing these characters—mothers and daughters, husbands and wives—into a surprisingly familiar reality. Written in hypnotic prose that gives grace to the grotesque, Things We Lost in the Fire is a powerful exploration of what happens when our darkest desires are left to roam unchecked, and signals the arrival of an astonishing and necessary voice in contemporary fiction.

submit a horror book!

#Things We Lost in the Fire#Mariana Enríquez#horror books#horrorbookpoll#horror#bookblr#books#horror short stories#short stories#argentinian horror#argentinian literature#spanish literature#spanish horror#latin american literature#gothic horror#magical realism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

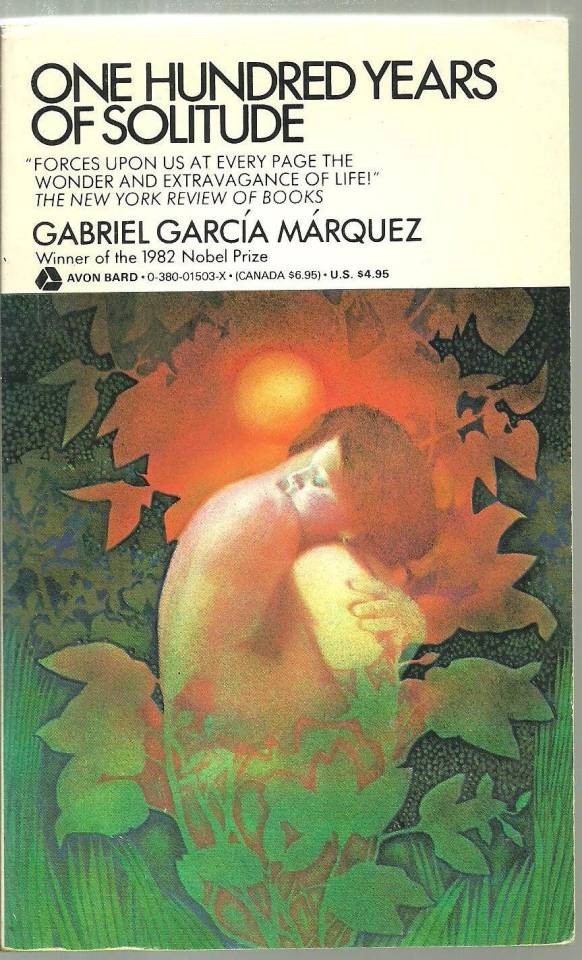

One Hundred Years of Solitude is a 1967 novel by Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez.

“Wherever they might be they always remember that the past was a lie, that memory has no return, that every spring gone by could never be recovered, and that the wildest and most tenacious love was an ephemeral truth in the end.”

Gabriel García Márquez "One Hundred Years of Solitude"

#books and reading#one hundred years of solitude#gabriel garcia marquez#colombia#latin american literature#magical realism#books#reading#quotes#booklr#bookish#booksbooksbooks#literary quotes#classic literature#literature quotes#book community#bibliophile#quote of the day#books and libraries#lit#prose#book recommendations#book recs#book list#book reccs#reading list#literature#writing#book cover

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know you're not a specialist in Latin America, but you are a specialist in literature, so: what and who would you say are the essential books and authors of Latin(/Central & South) America (& the Caribbean). Be as broad and over-inclusive as you like — or if you prefer, as specific, as creme-de-la-creme as you like. But I want the Pistelli crib sheet.

(You may have already written about this lol; if so, feel free to direct me to that).

The specialist in Latin America may be annoyed with what I'm about to say because said specialist will know the literatures of Latin America in granular detail, but the writers who have been the biggest influences on English-speaking literature are Jorge Luis Borges (read Labyrinths), Gabriel García Márquez (read One Hundred Years of Solitude), and Roberto Bolaño (read 2666). From the Lusophone quarter, the influence of Machado de Assis (read The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas) and Clarice Lispector (read The Hour of the Star) has been growing in English-language letters more recently. I've suggested that Valeria Luiselli's Mexican-American Lost Children Archive is among the best novels of the 2010s; Luiselli often alludes to Juan Rulfo's Pedro Páramo, said to be the greatest Mexican novel, also a favorite of Susan Sontag's. Everything I've written about Latin American literature, mostly focused on authors not mentioned above, can be found here. There are important authors I still need to read, especially Mario Vargas Llosa. Now when it comes to the Caribbean, I'm even less of an expert, but I can't not recommend Derek Walcott's epic Omeros, one of the great English-language poems of the 20th century.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

latino and spanish people, could you guys comment or reblog with names of authors/poets that are most popular/significant in your countries (or like, ones that you studied abt in high school) ?? im doing a slideshow abt literature for spanish class and id really appreciate it if someone would help me out !!!!

#i mean i can google. and i will but also i want to know from people who studied it in high school or collage or whatever i guess#spanish#spain#latino#latin america#spanish literature#latin american literature#spanish poetry#classic literature#literature#poetry

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pilar Quintana’s Los abismos and echinacea tea because I am sick. Los abismos is a fast reas because the language is simple and there’s not a lot of it per page, but it’s a slow read because I’m halfway through and still not that interested in what’s happening - or not happening, as the case may be. I have hope though!

#adult booklr#tomes and tea#literatura latinoamericana#pilar quintana#los abismos#latin american literature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Community of Literary Magazines and Presses offers up their Reading List for Hispanic Heritage Month 2023

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Juan Manuel Gaucher Troncoso—Juan Rulfo (acrylic on panel, 2018)

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

No entendía que hubiera necesitado tantas palabras para explicar lo que se sentía en la guerra, si con una sola bastaba: miedo.

Gabriel García Márquez, Cien años de soledad

#estoy leyendo#literature blog#literatura latina#literatura en español#gabo#gabriel garcia marquez#gabriel garcía márquez#colombia#realismo magico#realismo mágico#cien años de soledad#realismo fantastico#realismo fantástico#caribbean art#caribbean literature#latin american literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

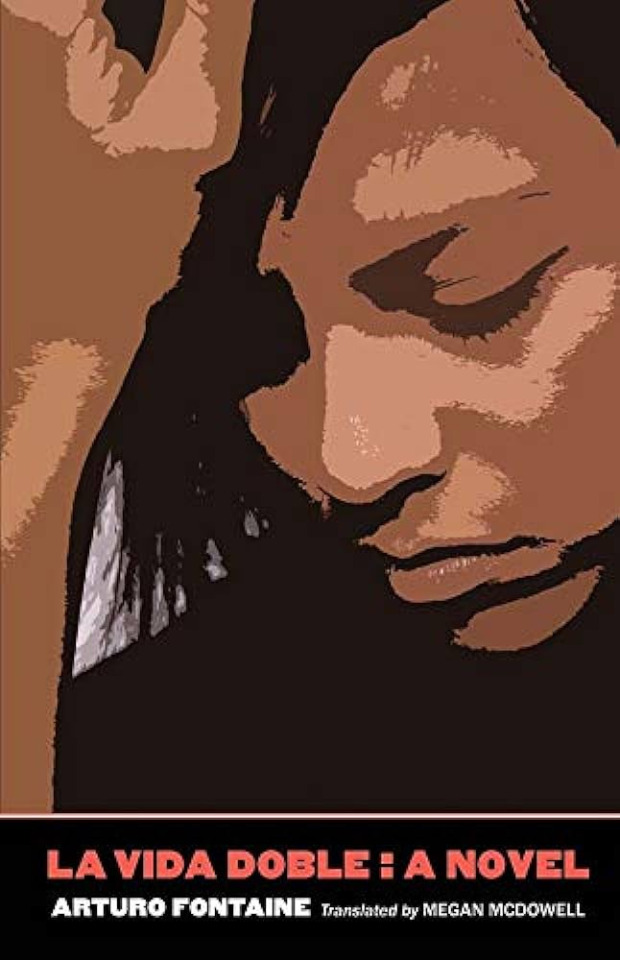

La Vida Doble p.35

Set in the darkest years of the Pinochet dictatorship, La Vida Doble is the story of Lorena, a leftist militant who arrives at a merciless turning point when every choice she confronts is impossible. Captured by agents of the Chilean repression, withstanding brutal torture to save her comrades, she must now either forsake the allegiances of motherhood or betray the political ideals to which she is deeply committed. While it is a novel it was written by the director of Chile's Museum of Memory and Human Rights and so based on extensive interviews of the real experiences of women prisoners.

This short passage captures so many of the tactics of psychological warfare that the Junta used to adjust leftist women from their lives as revolutionaries to political prisoners to sexual slaves. Simple things like underwear became something women longed for. " I just want to wear underpants; I want to put on a bra, that’s what I want." As she says to her companera she would give anything for a Triumph bra. And Junta guards fully exploited women's lack of bras, and made crude insulting comments about their breasts. This 1974 ad for Triumph bras, gives some of its connotations as a Swiss luxury brand, and why the Junta might see it as a triumph that an ex-militant now longs for one. "I’ve told her how I feel about underwear, what I would give for a Triumph bra. She doesn’t care at all about that. As long as they don’t rape her again, she doesn’t care about anything. I want a bra. I feel so skinny . . . Who could buy me a bra?"

Most disturbing is the final lines about how "some women are forced to dance and they end up naked as showgirls, dancing and crying, naked as effigies of showgirls". It was the ultimate form of degradation to turn revolutionary enemies into dancing strippers for their Fascist worst enemies. In this circumstance where underwear became a precious commodity for women prisoners, for comfort and their basic feminine needs. Women became desperate for any bra and underpants at all, and so were willing to wear the sexy, skimpy stripper bra and tangas, the Junta guards mockingly provided. "They end up naked". They started off clothed, and it was the process of undressing, stripping like showgirls that Junta guards found so amusing on revolutionary women. Despite the macabre scene of women dancing and crying, the tears of traumatized victims won them no sympathy from guards. Turning once dangerous women into entertainment was their cruel way of showing off that they were no longer a threat to Pinochet.

The translator Megan McDowell, in an interview asked the author, about how in the Chilean context, Communism had a much more inspiring idealistic background than most North Americans are familiar with, and it is a tragic contrast with what these inspiring idealistic women were reduced to.

MMcD: A related question—in the U.S., words like “Socialism,” “Communism,” and “Revolution” have a different resonance than they do in Chile. Even for people on the left, “communism” is associated with experiences of dictatorship and repression, and doesn’t have romantic or idealistic associations that it does for Lorena, or that people in Chile are more aware of, even if they don’t share them; there is little history of socialist ideas or movements in the U.S. Is there anything in particular you think your North American readers should be aware of about Chile’s history as they read your book?

AF: Not much, really. Lorena makes things understood as they need to be understood; for example, what it means to her to belong to a radical revolutionary movement that tries to win a utopia through armed struggle, one that demands from her the complete sacrifice of her life. There have been so many movements like that, and there always will be. Whether the inspiration comes from Che Guevara, or the movement’s name is this or that, or whatever the specific content of the project for a new society, these are not essential matters. The willingness to sacrifice oneself for something that feels huge, almost impossible, is always a human possibility. The Islamic fundamentalists are painful reminders of this. Furthermore, the immediate enemy is brutal dictatorship. But the use of torture to get information out of terrorist groups is something that has happened in many countries, even in some democratic ones and not too long ago . . . I would like for the novel to show, in contrast to the film Zero Dark Thirty, the victim’s perspective, the way his or her identity as a person is gradually torn to shreds.

4 notes

·

View notes