#leona florentino

Text

"Leona Cassiani was the only human being to whom Florentino Arizo was tempted to reveal all the secrets of Fermina Daza." (123)

--"Love in Time of Cholera" - Gabriel Garcia Marquez

0 notes

Text

Love in the Time of Cholera Book Summary

Love in the Time of Cholera Book Summary

Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez is a powerful novel that explores the complexities of love, passion, and the human condition. The story is set in a Caribbean town in the late 1800s, and it follows the lives of three characters – Florentino Ariza, Fermina Daza, and Dr. Juvenal Urbino.

The novel begins with Fermina rejecting Florentino's advances and marrying Dr. Juvenal Urbino, a brilliant and respected physician. Despite this, Florentino never stops loving Fermina and vows to wait for her. Meanwhile, Fermina tries to live a happy life with her husband, but she cannot escape the pull of Florentino's passion.

The story spans over fifty years, and we witness the characters' loves, losses, and struggles. Throughout the novel, we see the impact of societal norms and values, as well as the power of love to transcend boundaries and endure through time.

García Márquez's prose is both beautiful and evocative, using vivid descriptions and imagery to immerse the reader in the story's world. The novel is a masterpiece of magical realism, seamlessly blending the fantastical with the realistic.

Love in the Time of Cholera is a stunning novel that explores the depths of the human heart. It is a story of love in all its forms – romantic, familial, and platonic – and the ways in which it shapes our lives.

Character Analysis

Love in the Time of Cholera, including their personalities, motivations, and feelings. Florentino Ariza, the main character, is deeply in love with Fermina Daza but ends up waiting for her for over fifty years after she marries Dr. Juvenal Urbino. Ariza is a complex character, whose passionate love for Fermina leads him to have over six hundred love affairs. His obsession with Fermina stems from the fact that she represents pure love, and he believes that the fifty years he spent waiting for her are a form of penance for all the other affairs he had.

Fermina Daza, on the other hand, is a woman who refused to give in to societal pressures and married for love despite Dr. Juvenal Urbino's wealth and social status. Her strong-minded personality and independent spirit continue to dominate the narrative throughout the book. She is initially repulsed by Ariza's advances but eventually comes to love him after she discovers that she was never in love with her husband.

Dr. Juvenal Urbino, Fermina's husband and the love of her life, is a man who values order and discipline above all else. He is successful in his career as a doctor but fails to give his wife the emotional connection she craves. His death is a turning point in the novel, as it leads Fermina to reconsider her relationship with Ariza.

Other important characters in the novel include Leona Cassiani, who was Ariza's first lover and later becomes a successful businesswoman, and Lorenzo Daza, Fermina's father, who is a wealthy businessman that conforms to the expectations of society. The character analysis of Love in the Time of Cholera is a critical component of the novel's examination, as each character's personality and motivation plays an essential role in the development of the plot.

Analysis

Love in the Time of Cholera. One of the most prominent themes of the book is the power of love and its enduring nature. García Márquez portrays love as a force that can transcend time, societal expectations, and even death. This theme is illustrated through the relationship between Florentino and Fermina, who maintain their love for each other despite being separated for fifty years.

Another significant theme in the book is the role of societal norms and values in shaping individual lives. García Márquez depicts a society that is deeply concerned with class distinctions, reputation, and propriety. The characters in the book struggle to reconcile their desires with the expectations of their families and communities, highlighting the tension between individual freedom and societal expectations.

García Márquez's use of magical realism is also a notable literary technique throughout the book. He blends elements of the fantastic, such as the ghostly apparition of Florentino's mother, with the realistic portrayal of daily life in a Caribbean town. This technique creates a dreamlike atmosphere that adds to the book's sense of heightened emotion and passion.

Furthermore, setting plays an important role in the novel. The unnamed Caribbean town is portrayed as a place of both beauty and decay, where the passage of time is marked by natural cycles such as the changing of the seasons and the outbreak of cholera. The setting creates a sense of nostalgia and history, highlighting the enduring nature of love in the face of changing circumstances.

Love in the Time of Cholera is a poignant exploration of the complexity of human relationships, societal expectations, and the power of love. García Márquez's use of themes and literary techniques adds depth and nuance to the story, making it a timeless masterpiece of literature.

Reviews

Love in the Time of Cholera, highlighting the critical reception of the book from different sources. The novel has been widely acclaimed for its romantic themes, vivid imagery, and unique writing style. Many reviewers have praised Gabriel García Márquez's use of magical realism to convey the characters' emotions and the societal norms of the time.

Some critics have noted that the novel may not be for everyone, as it requires a certain level of patience and attention to fully appreciate. However, for those who are willing to invest the time, the book is said to be a deeply rewarding and moving experience.

One reviewer from The New York Times praised the book, saying, "The power of this book lies in García Márquez's ability to explore the depths of human emotion with incredible clarity and sensitivity." Another reviewer from The Guardian called it "a masterpiece of love and loss."

Love in the Time of Cholera has received overwhelmingly positive reviews, earning an average rating of 4.1 stars on Goodreads and ranking as one of the top 100 books of the 20th century in a poll conducted by The Guardian. Its timeless themes of love and passion continue to resonate with readers today, solidifying its place as a classic of modern literature.

Details

Love in the Time of Cholera was first published in 1985, with the original title, El Amor en los Tiempos del Cólera, in Spanish. The book was an instant success, both critically and commercially, in its native Colombia and soon garnered attention worldwide.

The novel was translated into numerous languages, including English, French, and German, and received widespread acclaim. It went on to win several prestigious awards, including the Nobel Prize in Literature for its author, Gabriel García Márquez, in 1982.

Gabriel García Márquez, or 'Gabo', as he was affectionately known, was a Colombian writer and journalist who is considered one of the most significant literary figures of the 20th century. He pioneered the literary style of magical realism and was famous for his lyrical prose, complex characters, and overarching themes of love, politics, and social justice.

Gabo's writing style was heavily influenced by his political beliefs and his experiences growing up in Colombia during a period of political upheaval. He was a devout Marxist and a vocal critic of imperialism and capitalism, which he believed led to widespread poverty and inequality in Latin America.

Love in the Time of Cholera is widely regarded as one of Gabo's most notable works, and it exemplifies his skill as a writer and his mastery of magical realism. The novel explores themes of love, desire, and the complexities of human relationships, set against the backdrop of a fictional Caribbean town.

Love in the Time of Cholera has received universal critical acclaim and has become a classic of modern literature, read and loved by millions of people around the world.

News about Love in the Time of Cholera

Love in the Time of Cholera has been adapted into multiple forms of media since its initial publication in 1985. In 2007, an adaptation of the book was released by New Line Cinema, directed by Mike Newell and starred Javier Bardem, Benjamin Bratt, and Giovanna Mezzogiorno. The film received mixed reviews from critics but was praised for its visual aesthetics and performances by the cast.

In 2019, the book was adapted into an opera by the English National Opera and premiered on November 26th, 2019, at the London Coliseum. The opera was composed by Hector Berlioz, with a libretto by Alain Altinoglu and Marcela Fuentes-Berain. The production was well-received by critics, with praise for the score and performances from the cast.

Love in the Time of Cholera has been translated into over 40 languages, making it one of Gabriel García Márquez's most widely read works. The book continues to be popular among readers and has become a staple of modern literature.

In 2014, Gabriel García Márquez passed away at the age of 87, but his legacy continues to live on through his literary works. Many fans of the book celebrate yearly events, such as Love in the Time of Cholera Day on August 15th, where they honor the book's themes of love and perseverance.

Recently, there have been discussions about the relevance of Love in the Time of Cholera in contemporary society. Some critics argue that the themes of the book, such as love, death, and the passage of time, are timeless and continue to resonate with modern readers. However, others argue that the book is dated and should be viewed in its historical context.

- Love in the Time of Cholera has also been referenced in popular culture, including in films, television shows, and music. For example, in the TV show The Office, a character mentions the book, and in the song "The Ghost of Corporate Future" by Regina Spektor, the lyrics make reference to a line from the novel.

- Love in the Time of Cholera has had a lasting impact on literature and popular culture. It remains a beloved and celebrated work, and its themes continue to resonate with readers across the world.

Ratings

Love in the Time of Cholera has generally received positive reviews from various sources such as Goodreads, Amazon, and other book review websites. On Goodreads, the book has an average rating of 3.9 out of 5 stars, with more than 350,000 ratings and over 15,000 reviews. Amazon also shows a high level of satisfaction with a rating of 4.4 out of 5 stars based on more than 3,000 customer reviews.readers praise Gabriel García Márquez's beautiful writing style, vivid descriptions, and complex character development. They also comment on the novel's exploration of love and passion, as well as the examination of societal norms and expectations.Some negative reviews criticize the book's slow pace and lengthy descriptions, or express disappointment with the ending. However, most readers agree that Love in the Time of Cholera is a timeless masterpiece and a must-read for lovers of literary fiction.With its high ratings and widespread critical acclaim, it's clear that Love in the Time of Cholera is a beloved classic that continues to capture the hearts and minds of readers around the world.

Book Notes

Love in the Time of Cholera is a complex and multi-layered book that explores the intricacies of human relationships and the nature of love. In this section, we provide a summary of the main ideas and themes of the book, including some of the key quotes and motifs that are central to the story.

- One of the central themes of the book is the transformative power of love. Throughout the novel, we see how love can change people, and how it can sustain them through difficult times. As Florentino Ariza observes, "Love is the voice under all silences, the hope which has no opposite in fear".

- The book also explores the idea of time and the ways in which it shapes our lives and relationships. Florentino Ariza waits over fifty years for Fermina Daza, and during that time, he transforms himself from a timid young man into a confident and successful business owner. As he reflects, "It was inevitable: the scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love".

- Another important motif in the book is the idea of illness and disease, particularly cholera. The outbreak of cholera in the town serves as a metaphor for the emotional contagion of love and desire.

- The novel also explores the role of social class and gender in relationships. Fermina Daza is initially attracted to Dr. Urbino because of his wealth and status, but later realizes that her feelings for Florentino Ariza are much deeper and more genuine.

Love in the Time of Cholera is a beautifully written and thought-provoking novel that explores some of the deepest and most profound human emotions. Whether you're a fan of magical realism, romance, or literary fiction, this book is sure to captivate and inspire you.

Read the full article

#LoveintheTimeofCholerabookdescription#LoveintheTimeofCholerabooknotes#LoveintheTimeofCholeracharacteranalysis#LoveintheTimeofCholerareviews

0 notes

Photo

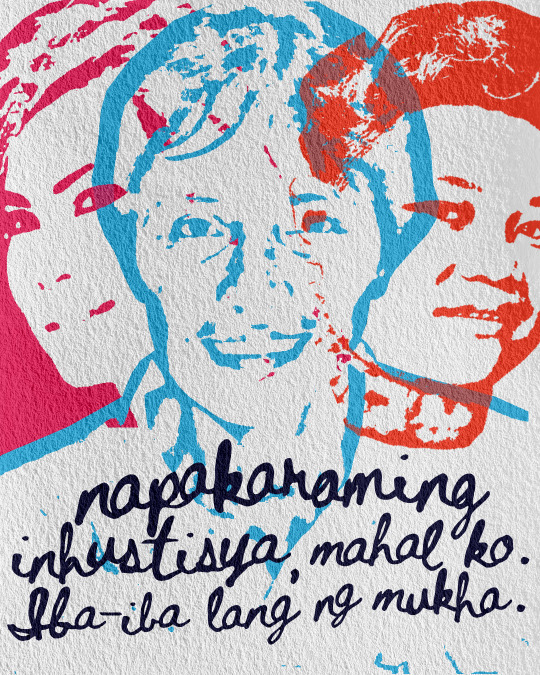

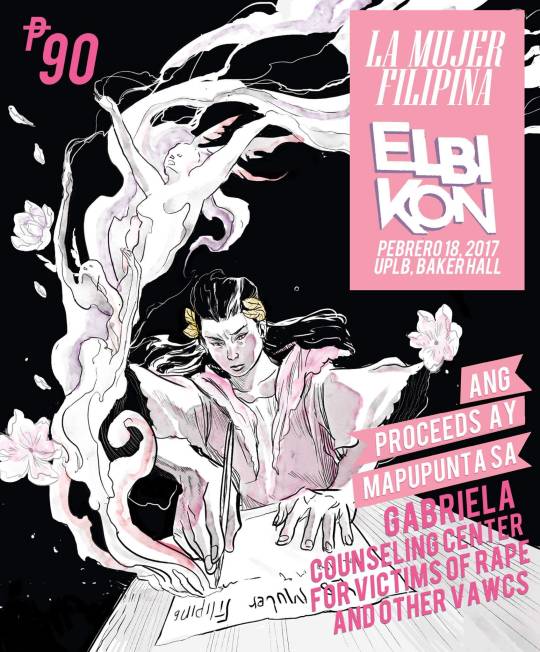

Hango mula sa Dead Balagtas Short: La Mujer Filipina (2017) ni Leona Florentino at Emiliana Kampilan; adaptasyon ng sanaysay ni Leona Florentino (1849-1884) sa parehong pamagat, La Mujer Filipina.

Hindi kailanman maihihiwalay ang danas at pakikibaka ng pagiging babae, sa pagiging parte ng LGBTQIA+, at pagiging Pilipino sa isang lipunang binubulok ng impe, pyudalismo, at burukrata-kapitalismo. Ang pagtakwil nito ay siya ring pagtatakwil sa tunay na kalayaan at dignidad ng ating bansang binuhat ng tatag, sigasig, talino, kalinga, at pagmamahal ng bawat kababaihang Pilipino.

Katarungan para kay Jennifer Laude, at ibang pang mga transwomen na pinaslang at kumakaharap ng karahasan dahil lang sa kanilang pagkakakilanlan.

Hustisya para kay Lenie Rivas, at iba pang mga Lumad na minasaker at dinadahas ng mga militar sa kanilang sariling lupang ninuno.

Panawagan sa paglitaw ni Elizabeth "Loi" Magbanua, lesbiyanang aktibista at organisador, at iba pang mga desaparecidos na buong tapang at pusong naglilingkod para sa bayan.

Ina-alala natin ang kanilang memorya tungo sa isang mundo kung saa'y malaya magdiwang ng kanilang pagkakakilanlan. Mundong may hustisya, respeto, at pagkakapantay-pantay.

--

Para sa Abante, Babae zine ng Gabriela Santa Cruz, California

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Clearly the women were not a captive audience in the war among armed men. When they moved, singularly or collectively, the revolution did not stand still.” — Camagay, Maria Luis. “Kababaihan sa Rebolusyon (Women in Revolution).” Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies 14.2 (1998).

the women of the philippine revolution, in honor of national heroes’ day

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#documentaryedit#history#philippines#gabriela silang#gregoria de jesus#teresa magbanua#agueda kahabagan#clemencia lopez#leona florentino#melchora aquino#patrocinio gamboa#kababaihan ng rebolusyon#<- that's the name of the documentary i used#lupain ng ginto't bulaklak#nadz rambles#*gifs

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

(image description: black text on a white background reading “My fate is dim, my stars so low, perhaps nothing to it can compare,”. end id)

Leona Florentino, Blasted Hopes

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kitakits sa elbikon!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature

by: Christine F. Godinez-Ortega

The diversity and richness of Philippine literature evolved side by side with the country's history. This can best be appreciated in the context of the country's pre-colonial cultural traditions and the socio-political histories of its colonial and contemporary traditions.

The average Filipino's unfamiliarity with his indigenous literature was largely due to what has been impressed upon him: that his country was "discovered" and, hence, Philippine "history" started only in 1521.

So successful were the efforts of colonialists to blot out the memory of the country's largely oral past that present-day Filipino writers, artists and journalists are trying to correct this inequity by recognizing the country's wealth of ethnic traditions and disseminating them in schools and in the mass media.

The rousings of nationalistic pride in the 1960s and 1970s also helped bring about this change of attitude among a new breed of Filipinos concerned about the "Filipino identity."

Pre-Colonial Times

Owing to the works of our own archaeologists, ethnologists and anthropologists, we are able to know more and better judge information about our pre-colonial times set against a bulk of material about early Filipinos as recorded by Spanish, Chinese, Arabic and other chroniclers of the past.

Pre-colonial inhabitants of our islands showcase a rich past through their folk speeches, folk songs, folk narratives and indigenous rituals and mimetic dances that affirm our ties with our Southeast Asian neighbors.

The most seminal of these folk speeches is the riddle which is tigmo in Cebuano, bugtong in Tagalog, paktakon in Ilongo and patototdon in Bicol. Central to the riddle is the talinghaga or metaphor because it "reveals subtle resemblances between two unlike objects" and one's power of observation and wit are put to the test. While some riddles are ingenious, others verge on the obscene or are sex-related.

The proverbs or aphorisms express norms or codes of behavior, community beliefs or they instill values by offering nuggets of wisdom in short, rhyming verse.

The extended form, tanaga, a mono-riming heptasyllabic quatrain expressing insights and lessons on life is "more emotionally charged than the terse proverb and thus has affinities with the folk lyric." Some examples are the basahanon or extended didactic sayings from Bukidnon and the daraida and daragilon from Panay.

The folk song, a form of folk lyric which expresses the hopes and aspirations, the people's lifestyles as well as their loves. These are often repetitive and sonorous, didactic and naive as in the children's songs or Ida-ida (Maguindanao), tulang pambata (Tagalog) or cansiones para abbing (Ibanag).

A few examples are the lullabyes or Ili-ili (Ilongo); love songs like the panawagon and balitao (Ilongo); harana or serenade (Cebuano); the bayok (Maranao); the seven-syllable per line poem, ambahan of the Mangyans that are about human relationships, social entertainment and also serve as a tool for teaching the young; work songs that depict the livelihood of the people often sung to go with the movement of workers such as the kalusan (Ivatan), soliranin (Tagalog rowing song) or the mambayu, a Kalinga rice-pounding song; the verbal jousts/games like the duplo popular during wakes.

Other folk songs are the drinking songs sung during carousals like the tagay (Cebuano and Waray); dirges and lamentations extolling the deeds of the dead like the kanogon (Cebuano) or the Annako (Bontoc).

A type of narrative song or kissa among the Tausug of Mindanao, the parang sabil, uses for its subject matter the exploits of historical and legendary heroes. It tells of a Muslim hero who seeks death at the hands of non-Muslims.

The folk narratives, i.e. epics and folk tales are varied, exotic and magical. They explain how the world was created, how certain animals possess certain characteristics, why some places have waterfalls, volcanoes, mountains, flora or fauna and, in the case of legends, an explanation of the origins of things. Fables are about animals and these teach moral lessons.

Our country's epics are considered ethno-epics because unlike, say, Germany's Niebelunginlied, our epics are not national for they are "histories" of varied groups that consider themselves "nations."

The epics come in various names: Guman (Subanon); Darangen (Maranao); Hudhud (Ifugao); and Ulahingan (Manobo). These epics revolve around supernatural events or heroic deeds and they embody or validate the beliefs and customs and ideals of a community. These are sung or chanted to the accompaniment of indigenous musical instruments and dancing performed during harvests, weddings or funerals by chanters. The chanters who were taught by their ancestors are considered "treasures" and/or repositories of wisdom in their communities.

Examples of these epics are the Lam-ang (Ilocano); Hinilawod (Sulod); Kudaman (Palawan); Darangen (Maranao); Ulahingan (Livunganen-Arumanen Manobo); Mangovayt Buhong na Langit (The Maiden of the Buhong Sky from Tuwaang--Manobo); Ag Tobig neg

Keboklagan (Subanon); and Tudbulol (T'boli).

The Spanish Colonial Tradition

While it is true that Spain subjugated the Philippines for more mundane reasons, this former European power contributed much in the shaping and recording of our literature. Religion and institutions that represented European civilization enriched the languages in the lowlands, introduced theater which we would come to know as komedya, the sinakulo, the sarswela, the playlets and the drama. Spain also brought to the country, though at a much later time, liberal ideas and an internationalism that influenced our own Filipino intellectuals and writers for them to understand the meanings of "liberty and freedom."

Literature in this period may be classified as religious prose and poetry and secular prose and poetry.

Religious lyrics written by ladino poets or those versed in both Spanish and Tagalog were included in early catechism and were used to teach Filipinos the Spanish language. Fernando Bagonbanta's "Salamat nang walang hanga/gracias de sin sempiternas" (Unending thanks) is a fine example that is found in the Memorial de la vida cristiana en lengua tagala (Guidelines for the Christian life in the Tagalog language) published in 1605.

Another form of religious lyrics are the meditative verses like the dalit appended to novenas and catechisms. It has no fixed meter nor rime scheme although a number are written in octosyllabic quatrains and have a solemn tone and spiritual subject matter.

But among the religious poetry of the day, it is the pasyon in octosyllabic quintillas that became entrenched in the Filipino's commemoration of Christ's agony and resurrection at Calvary. Gaspar Aquino de Belen's "Ang Mahal na Passion ni Jesu Christong Panginoon natin na tola" (Holy Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ in Verse) put out in 1704 is the country's earliest known pasyon.

Other known pasyons chanted during the Lenten season are in Ilocano, Pangasinan, Ibanag, Cebuano, Bicol, Ilongo and Waray.

Aside from religious poetry, there were various kinds of prose narratives written to prescribe proper decorum. Like the pasyon, these prose narratives were also used for proselitization. Some forms are: dialogo (dialogue), Manual de Urbanidad (conduct book); ejemplo (exemplum) and tratado (tratado). The most well-known are Modesto de Castro's "Pagsusulatan ng Dalawang Binibini na si Urbana at si Feliza" (Correspondence between the Two Maidens Urbana and Feliza) in 1864 and Joaquin Tuason's "Ang Bagong Robinson" (The New Robinson) in 1879, an adaptation of Daniel Defoe's novel.

Secular works appeared alongside historical and economic changes, the emergence of an opulent class and the middle class who could avail of a European education. This Filipino elite could now read printed works that used to be the exclusive domain of the missionaries.

The most notable of the secular lyrics followed the conventions of a romantic tradition: the languishing but loyal lover, the elusive, often heartless beloved, the rival. The leading poets were Jose Corazon de Jesus (Huseng Sisiw) and Francisco Balagtas. Some secular poets who wrote in this same tradition were Leona Florentino, Jacinto Kawili, Isabelo de los Reyes and Rafael Gandioco.

Another popular secular poetry is the metrical romance, the awit and korido in Tagalog. The awit is set in dodecasyllabic quatrains while the korido is in octosyllabic quatrains. These are colorful tales of chivalry from European sources made for singing and chanting such as Gonzalo de Cordoba (Gonzalo of Cordoba) and Ibong Adarna (Adarna Bird). There are numerous metrical romances in Tagalog, Bicol, Ilongo, Pampango, Ilocano and in Pangasinan. The awit as a popular poetic genre reached new heights in Balagtas' "Florante at Laura" (ca. 1838-1861), the most famous of the country's metrical romances.

Again, the winds of change began to blow in 19th century Philippines. Filipino intellectuals educated in Europe called ilustrados began to write about the downside of colonization. This, coupled with the simmering calls for reforms by the masses gathered a formidable force of writers like Jose Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Mariano Ponce, Emilio Jacinto and Andres Bonifacio.

This led to the formation of the Propaganda Movement where prose works such as the political essays and Rizal's two political novels, Noli Me Tangere and the El filibusterismo helped usher in the Philippine revolution resulting in the downfall of the Spanish regime, and, at the same time planted the seeds of a national consciousness among Filipinos.

But if Rizal's novels are political, the novel Ninay (1885) by Pedro Paterno is largely cultural and is considered the first Filipino novel. Although Paterno's Ninay gave impetus to other novelists like Jesus Balmori and Antonio M. Abad to continue writing in Spanish, this did not flourish.

Other Filipino writers published the essay and short fiction in Spanish in La Vanguardia, El Debate, Renacimiento Filipino, and Nueva Era. The more notable essayists and fictionists were Claro M. Recto, Teodoro M. Kalaw, Epifanio de los Reyes, Vicente Sotto, Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, Rafael Palma, Enrique Laygo (Caretas or Masks, 1925) and Balmori who mastered the prosa romantica or romantic prose.

But the introduction of English as medium of instruction in the Philippines hastened the demise of Spanish so that by the 1930s, English writing had overtaken Spanish writing. During the language's death throes, however, writing in the romantic tradition, from the awit and korido, would continue in the novels of Magdalena Jalandoni. But patriotic writing continued under the new colonialists. These appeared in the vernacular poems and modern adaptations of works during the Spanish period and which further maintained the Spanish tradition.

The American Colonial Period

A new set of colonizers brought about new changes in Philippine literature. New literary forms such as free verse [in poetry], the modern short story and the critical essay were introduced. American influence was deeply entrenched with the firm establishment of English as the medium of instruction in all schools and with literary modernism that highlighted the writer's individuality and cultivated consciousness of craft, sometimes at the expense of social consciousness.

The poet, and later, National Artist for Literature, Jose Garcia Villa used free verse and espoused the dictum, "Art for art's sake" to the chagrin of other writers more concerned with the utilitarian aspect of literature. Another maverick in poetry who used free verse and talked about illicit love in her poetry was Angela Manalang Gloria, a woman poet described as ahead of her time. Despite the threat of censorship by the new dispensation, more writers turned up "seditious works" and popular writing in the native languages bloomed through the weekly outlets like Liwayway and Bisaya.

The Balagtas tradition persisted until the poet Alejandro G. Abadilla advocated modernism in poetry. Abadilla later influenced young poets who wrote modern verses in the 1960s such as Virgilio S. Almario, Pedro I. Ricarte and Rolando S. Tinio.

While the early Filipino poets grappled with the verities of the new language, Filipinos seemed to have taken easily to the modern short story as published in the Philippines Free Press, the College Folio and Philippines Herald. Paz Marquez Benitez's "Dead Stars" published in 1925 was the first successful short story in English written by a Filipino. Later on, Arturo B. Rotor and Manuel E. Arguilla showed exceptional skills with the short story.

Alongside this development, writers in the vernaculars continued to write in the provinces. Others like Lope K. Santos, Valeriano Hernandez Peña and Patricio Mariano were writing minimal narratives similar to the early Tagalog short fiction called dali or pasingaw (sketch).

The romantic tradition was fused with American pop culture or European influences in the adaptations of Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan by F. P. Boquecosa who also penned Ang Palad ni Pepe after Charles Dicken's David Copperfield even as the realist tradition was kept alive in the novels by Lope K. Santos and Faustino Aguilar, among others.

It should be noted that if there was a dearth of the Filipino novel in English, the novel in the vernaculars continued to be written and serialized in weekly magazines like Liwayway, Bisaya, Hiligaynon and Bannawag.

The essay in English became a potent medium from the 1920's to the present. Some leading essayists were journalists like Carlos P. Romulo, Jorge Bocobo, Pura Santillan Castrence, etc. who wrote formal to humorous to informal essays for the delectation by Filipinos.

Among those who wrote criticism developed during the American period were Ignacio Manlapaz, Leopoldo Yabes and I.V. Mallari. But it was Salvador P. Lopez's criticism that grabbed attention when he won the Commonwealth Literay Award for the essay in 1940 with his "Literature and Society." This essay posited that art must have substance and that Villa's adherence to "Art for Art's Sake" is decadent.

The last throes of American colonialism saw the flourishing of Philippine literature in English at the same time, with the introduction of the New Critical aesthetics, made writers pay close attention to craft and "indirectly engendered a disparaging attitude" towards vernacular writings -- a tension that would recur in the contemporary period.

The Contemporary Period

The flowering of Philippine literature in the various languages continue especially with the appearance of new publications after the Martial Law years and the resurgence of committed literature in the 1960s and the 1970s.

Filipino writers continue to write poetry, short stories, novellas, novels and essays whether these are socially committed, gender/ethnic related or are personal in intention or not.

Of course the Filipino writer has become more conscious of his art with the proliferation of writers workshops here and abroad and the bulk of literature available to him via the mass media including the internet. The various literary awards such as the Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature, the Philippines Free Press, Philippine Graphic, Home Life and Panorama literary awards encourage him to compete with his peers and hope that his creative efforts will be rewarded in the long run.

With the new requirement by the Commission on Higher Education of teaching of Philippine Literature in all tertiary schools in the country emphasizing the teaching of the vernacular literature or literatures of the regions, the audience for Filipino writers is virtually assured. And, perhaps, a national literature finding its niche among the literatures of the world will not be far behind.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

PHILIPPINE HISTORY

♣️The first book written in the Philippines was DOCTRINA CRISTIANA.

♣️The Father of Ilocano Literature is PEDRO BUKANEG.

♣️The Father of Tagalog Poetry is FRANCISCO BALTAZAR.

♣️Lola Basyang is the pen name of SEVERINO REYES.

♣️The first and longest running komiks series in the Philippines is KENKOY(Liwayway Magasin,1929)

♣️The Father of Pampango Literature who wrote There is no God is JUAN CRISOSTOMO SOTO.

♣️The oldest existing newspaper in the Philippines since the 1900 is MANILA BULLETIN.

♣️The Father of Modern Tagalog Poetry is ALEJANDRO ABADILLA.

♣️The work of Bonifacio which tells the history of the Philippines ANG DAPAT MABATID NG MGA TAGALOG.

♣️He wrote the popular fable The Monkey and the Turtle - JOSE RIZAL

♣️This is known as Andres Bonifacio's Ten Commandments of the Katipunan - THE DECALOGUE.

♣️Rizal's model for Pilosopong Tasyo was PACIANO RIZAL.

♣️The following characters created by rizal reflect his own personality except SIMOUN (El Filibusterismo)

♣️The line 'whoever knows not how to love his native tongue is worse than any beast or even smelly fish' TO MY FELLOW CHILDREN

♣️Rizal's pen name - DIMASALANG, LAONG-LAAN

♣️Taga-ilog is JUAN LUNA's Pen name.

♣️The first filipino alphabet was called ALIBATA/BAYBAYIN

♣️the first filipino alphabet consisted of 15 LETTERS

♣️This is a song about love - TALINDAW, awit ng mga taong hindi naimbetahan sa kainan (COLADO)

♣️He was known for his `Memoria Fotografica` - JOSE MA. PANGANIBAN

♣️He is known as the `poet of the workers or laborers` - AMADO HERNANDEZ

♣️Ilocano balagtasan is called BUKANEGAN

♣️Visayan epic about good manners and right conduct - MARAGTAS

♣️The father of Filipino newspaper is PASCUAL POBLETE

♣️Lupang Tinubuan is considered to be the best story written during Japanese Period. The author is NARCISO REYES

♣️The original title of Ibong Adarna was CORIDO AT BUHAY NA PINAGDAANAN NG TATLONH PRINSIPENG ANAC NG HARING FERNANDO AT REYNA VALERIANA SA CAHARIANG BERBANIA

♣️PANDEREGLA - first filipino bread

♣️The Great Plebian: Andres Bonifacio

♣️The Father of the Katipunan: Andres Bonifacio

♣️Hero of the Tirad Pass Battle: Gregorio Del Pilar

♣️President of the First Philippine Republic: General Emilio Aguinaldo

♣️Brains of the Philippine Revolution: Apolinario Mabini

♣️Martyred Priests in 1872: GOMBURZA

♣️Brains of the Katipunan: Emilio Jacinto

♣️Co-founder of La Independencia: General Antonio Luna

♣️Mother of Balintawak: Melchora Aquino

♣️Greatest Filipino Orator of the Propaganda Movement: Graciano Lopez- Jaena

♣️First Filipino Cannon-maker: Pandar Pira

♣️Managing Editor of La Solidaridad: Mariano Ponce

♣️Lakambini of Katipunan: Gregoria de Jesus

♣️Poet of the Revolution: Fernando Ma. Guerrero

♣️Outstanding Diplomat of the First Philippine Republic: Felipe Agoncill

♣️First University of the Philippines President: Rafael Palma

♣️Greatest Filipino Painter: Juan Luna

Greatest Journalist of the Propaganda

♣️Movement: Marcelo H. del Pilar

♣️First Filipino Poetess: Leona Florentino

♣️Peace of the Revolution: Pedro Paterno

♣️Founder of Philippine Socialism: Isabelo

♣️Delos Reyes Viborra: Artemio Ricarte

♣️Author of the Spanish lyrics of the Philippine National Anthem: Jose Palma

♣️Chief of Tondo: Lakandola

♣️The Last Rajah of Manila: Rajah Soliman

♣️Fiancée of Jose Rizal: Leonor Rivera

♣️Maker of the

First Filipino Flag: Marcela Agoncillo

♣️Co-founder of Katipunan: Galicano Apacible

♣️Leader of the Ilocano Revolt: Diego Silang

♣️First Filipino Hero: Lapu-lapu

♣️Leader of the Longest Revolt in Bohol: Francisco Dagohoy

♣️The Man of Many Talents: Epifanio Delos Santos

♣️Prince of Tagalog Poets: Francisco Baltazar

♣️Visayan Joan of Arc: Teresa Magbanua

♣️Mother of Biak-na-Bato: Trinidad Tecson

♣️Wife of Artemio Ricarte: Agueda

♣️EstebanLeader of the Tarlac Revolt: Gen. Francisco Makabulos

♣️Composer of the Philippine National Anthem: Julian Felipe

♣️Spaniards born in the Philippines: Insulares

♣️Leader of Magdalo: Baldomero Aguinaldo

♣️Leader of Magdiwang: Mariano Alvarez

♣️Founder of La Liga Filipina: Jose Rizal

♣️Painter of the Spolarium: Juan Luna

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

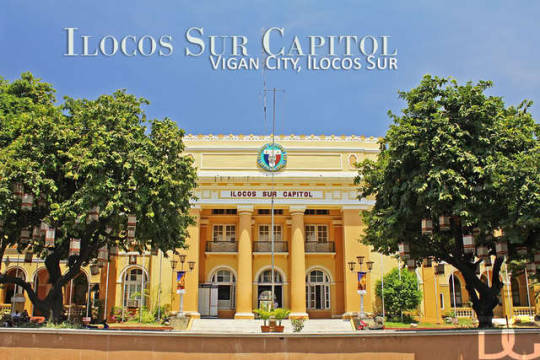

Why can you do with Calle Crisologo?

Finding activities, places, and arts in the street of Calle Crisologo? We got you!

Abel-Iloko photo courtesy by Travel Trilogy (2014).

If you appreciate art, you should take a look at the Abel-Iloko Weaving community. Abel is a traditional weaving method in Ilocos, it is also a dying culture as younger generations opted not to continue this tradition. The weave weave produces such as blankets, table napkins, placemats and more.

The making of a pot photo courtesy by Leah De Leon.

If you take an interest in poetry, visit Pagburnayan— open for 24 hours. Poetry or burnay, is also a dying culture in Vigan because no one wants to continue the making of jars.

Calle Crisologo is known for its Spanish architecture that was built in the 15th century and still continues to be preserved today. An intact representation of a perfectly planned Spanish colonial town in Asia would be in Vigan, Ilocos Sur. Most people visit Vigan to go on a late night stroll at the Vigan Heritage Village. Streets filled with horse carriages, more commonly known as kalesa.

Street of Calle Crisologo, a photo courtesy by Wikipedia.

The buildings and structures are a blend of Asian building design and European colonial architecture and planning. Even restaurants and stores have a Spanish feel to it. The river in the area used to be a trading post for the Chinese, they used to go to Vigan to trade goods in exchange for gold, beeswax, and other products and resources in the Cordillera region.

Café Leona, a photo courtesy by Buffet of Blessings.

If you’re looking for a place to try authentic Vigan Longganisa and Bagnet dishes, you should definitely stop by at Café Leona. They also serve Japanese, Thai, and Italian cuisines. Leona Café was named after Leona Florentino, a poetess. Before it was turned into a restaurant, it was actually Leona’s ancestral home.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vigan Cathedral

On a trip to Vigan, Ilocus Sur, many visitors appreciate the stunning architecture of large churches known as cathedrals. Cathedrals were far larger than castles symbolic of their huge importance to medieval society where religion dominated the lives of all. The church is predominantly in Earthquake Baroque style with large buttresses on its side. It also has Neo-Gothic, Romanesque and Chinese inspired embellishments. In its interior are silver-paneled main altar, three naves, 12 minor altars and brass communion handrails. South of the cathedral is a separate 25 metres bell tower with a weather rooster on top, which symbolizes Saint Peter. The only remaining Archbishop's Palace in the Philippines built during the Spanish colonization is located in Vigan, beside the cathedral. The church also contains remains of former bishops of the Diocese of Nueva Segovia, as well as the remains of Ilocano poet Leona Florentino.

Vigan Cathedral enjoys two kinds of seasons, the dry season from November to April and the wet season from May to October. It is recommended that travelers visit during dry season, especially from December to February when temperatures are much cooler and touring will most likely not be interrupted by rains. Another thing to consider when deciding on the date for your Vigan tour is the schedule of festivities. A visit during the Christmas holidays, New Year’s, Vigan City Festival, Holy Week and Viva Vigan celebrations are recommended. The view of the cathedral is so religious but in front of it is a Rizal statue at the middle of a wide fountain. The left side of the church has an old-fashioned hotel and the right side has a mcdonalds, watsons and other establishments that has an old-fashioned design too. I like how they preserve the old-fashion design from the Spain who was invaded us before. We travel to Vigan, Ilocos Sur to see and appreciate the beauty of the cathedral. This is my first time to travel far away from my home town and see famous establishment in other place here in the Philippines. This cathedral is near by the high way so you can arrived easily specially to the people who are traveling so they can attend church and pray before go anywhere. For your tour around Vigan, bring a foldable umbrella, a fan and a water bottle in your bags. Though information over the web will arm you well for your visit, a stop at the Tourist Center is a must if you want to make sure that you have all the information that you need. It is located at the entrance of Calle Crisologo, beside the Heritage Village. The best advice to visitors is to take a calesa ride when touring the UNESCO Heritage Village and nearby sights. The rate is Php 150 per hour. You can decide on the places you want to visit from the map you’ve secured. Inform the driver about it before the start of the calesa ride. The calesa can accommodate up to four adults. Remember that there are calesas accredited by the Department of Tourism. If you want to try the tricycle to transport you to farther tourist sites, it is recommended that the fare cost be determined before you hop in. You can haggle on the quoted price. Visitors are also advised to bring small bills and change because drivers don’t usually have enough change. You might end up paying more than the agreed price because you only have big bills. You can also arrange for tricycles to pick you up at an appointed time. Haggling is the norm when shopping in Vigan, so don’t be shy to do so. The locals can converse in english and though their manner of speaking might come on too strong, this is normally how they speak. Vigan Cathedral, canonically known as the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Conversion of St. Paul the Apostle is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Vigan, Ilocos Sur, Philippines. It serves as the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Nueva Segovia. When Juan de Salcedo came to Vigan, he renamed the town to Villa Fernandina in honor of the young son of King Philip II. Upon the orders of Salcedo in 1574, the first temporary church of Vigan was built out of wood and thatch. It became the first parish in Northern Luzon. The Franciscans then came to Ilocos with Father Sebastian de Baesa as priest of Vigan. Father Gabriel dela Cruz became the first secular priest of Vigan until 1598. When the Augustinians returned to Ilocos in 1586, they also handled Vigan alternately with the secular clergy. On February 14, 1622, Vigan was officially transferred from the Augustinians to the secular. The first church was built in 1641 and was damaged by earthquake in 1619 and 1627. A third church was burned in 1739. With the transfer of the seat of the Diocese, the church of Vigan became a cathedral on that same year. The fourth and present-day church was built from 1790 to 1800 under the Augustinians.

Complete your vacation in Vigan City, Ilocos Sur with prayers and full of blessings in Vigan Cathedral; captured every moment and treasure all the memories you have with your friends and family.

0 notes

Text

Then Florentino Ariza knew that some night, sometime in the future, in a joyous bed with Fermina Daza, he was going to tell het that he had not revealed the secret of his love, not even to the one person who had earned the right to know it. No: he would never reveal it, not even to Leona Cassiani, not because he did not want to open the chest where he had kept it so carefully hidden for half his life, but because he realisrd only then that he had lost the key.

Love in the time of cholera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Before the coming of the Spaniards, the coastal plains in northwestern Luzon, stretching from Bangui (Ilocos Norte) in the north to Namacpacan (Luna, La Union) in the south, were as a whole known as a progressive region called the Ylokos. This region lies in between the China Sea in the west and Northern Cordilleras on the east. The inhabitants built their villages near the small bays on coves called “looc” in the dialect. These coastal inhabitants were referred to as “Ylocos” which literally meant “from the lowlands”. The entire region was then called by the ancient name “Samtoy” from “sao ditoy” which in Ilokano mean “our dialect”. The region was later called by the Spaniards as “Ylocos” or “Ilocos” and its people “Ilocanos”. The Ilocos Region was already a thriving, fairly advanced cluster of towns and settlements familiar to Chinese, Japanese and Malay traders when the Spaniard explorer Don Juan de Salcedo and members of his expedition arrived in Vigan on July 1574. Forthwith, they made Cabigbigaan (Bigan), the heart of the Ylokos settlement their headquarters which Salcedo called “Villa Fernandina” and which eventually gained fame as the “Intramuros of Ilocandia”. Salcedo declared the whole Northern Luzon as an encomienda. Subsequently, he became the encomendero of Vigan and Lieutenant Governor of the Ylokos until his death in March 11, 1576. Augustinian missionaries joined the military forces in conquering the region through evangelization. They established parishes and built churches that still stand today. Three centuries later, Vigan became the seat of the Archdiocese of Nueva Segovia. A royal decree of February 2, 1818 separated Ilocos Norte from Ilocos Sur, the latter to include the northern part of La Union (as far as Namacpacan, now Luna) and all of what is now the province of Abra. The sub-provinces of Lepanto and Amburayan in Mt. Province were annexed to Ilocos Sur. The passage of Act 2683 by the Philippine Legislature in March 1917 defined the present geographical boundary of the province. The names of famous men and women of Ilocos Sur stand in bold relief in Philippine history. Pedro Bukaneg is the Father of Iluko Literature. Isabelo de los Reyes will always be remembered as the Father of the Filipino Labor Movement. His mother, Leona Florentino was the most outstanding Filipino woman writer of the Spanish era. Vicente Singson Encarnacion, an exemplary statesman, was also a noted authority on business and industry.

0 notes

Photo

Bagnet, pakbet Pakbet, bagnet Just can’t get enough of Café Leona’s bagnet and pakbet in Vigan! This ancestral house of Leona Florentino, a foremost Ilocano poetess who is a distant cousin of Dr. Jose P. Rizal has turned out to be Calle Crisologo’s must-try resto. Aside from their native delicacies, their pizza is also a bomb! It’s freshly baked in a traditional “pugon” giving it a smoky flavor. This just capped my Vigan dream that after our lunch, I told my pack that I may now leave ‘coz my trip has already been completed! 😊 #theothersideofmae #travelblog #lifestyleblog #foodblog #foodblogger #travelblogger #travelwriter #cafeleona #vigan #bagnet #philippines #pakbet #foodphotography (at Calle Crisologo Vigan, Ilocos Sur) https://www.instagram.com/maeolandesca/p/BycsVdeHxYC/?igshid=vioqr9g9ijkn

#theothersideofmae#travelblog#lifestyleblog#foodblog#foodblogger#travelblogger#travelwriter#cafeleona#vigan#bagnet#philippines#pakbet#foodphotography

0 notes

Photo

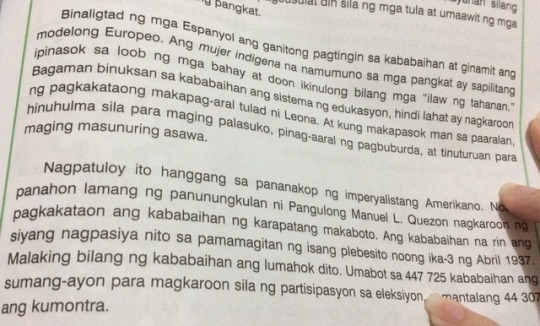

Trans: The Spaniards changed this view on women and used European [views and ways I guess]. The mujer indigena* that used to lead groups were forced to stay at home and became the "ilaw ng tahanan"*. Even though women opened up the system of education, not everyone were given a chance to learn like Leona*. And if they did, they were taught to be submissive, sew clothes and to be an obedient wife. *mujer indegena refers to the Native Pilipinas (idk how to put it) They were usually the leaders in the community, can buy properties and etc. *phrase we use to refer to mothers. *Leona Florentino. She's known as "Ina ng Panitikang Kababaihan" or "Mother of Women's Literature" She legit left her husband because he thinks she shouldn't be writing and should just be focused on being a wife. I'm glad she did. This is an article (i think?) called Pilipina: Ari-arian o May Sariling Karapatan? by Mark Angeles. It talks about the freedom of women in the past along with sexual division of labor in the Philippines. This is a direct translation and it's shit but wtv i love my Social Studies book.

#this is the first time im actually interested in a textbook#im gonna ace social studies for the first time#ignore my long ass nails

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The diversity and richness of Philippine literature evolved side by side with the country's history. This can best be appreciated in the context of the country's pre-colonial cultural traditions and the socio-political histories of its colonial and contemporary traditions.

The average Filipino's unfamiliarity with his indigenous literature was largely due to what has been impressed upon him: that his country was "discovered" and, hence, Philippine "history" started only in 1521.

So successful were the efforts of colonialists to blot out the memory of the country's largely oral past that present-day Filipino writers, artists and journalists are trying to correct this inequity by recognizing the country's wealth of ethnic traditions and disseminating them in schools and in the mass media.

The rousings of nationalistic pride in the 1960s and 1970s also helped bring about this change of attitude among a new breed of Filipinos concerned about the "Filipino identity."

Pre-Colonial Times

Owing to the works of our own archaeologists, ethnologists and anthropologists, we are able to know more and better judge information about our pre-colonial times set against a bulk of material about early Filipinos as recorded by Spanish, Chinese, Arabic and other chroniclers of the past.

Pre-colonial inhabitants of our islands showcase a rich past through their folk speeches, folk songs, folk narratives and indigenous rituals and mimetic dances that affirm our ties with our Southeast Asian neighbors.

The most seminal of these folk speeches is the riddle which is tigmo in Cebuano, bugtong in Tagalog, paktakon in Ilongo and patototdon in Bicol. Central to the riddle is the talinghaga or metaphor because it "reveals subtle resemblances between two unlike objects" and one's power of observation and wit are put to the test. While some riddles are ingenious, others verge on the obscene or are sex-related:

Gaddang:

Gongonan nu usin y amam If you pull your daddy's penis

Maggirawa pay sila y inam. Your mommy's vagina, too,

(Campana) screams. (Bell)

The proverbs or aphorisms express norms or codes of behavior, community beliefs or they instill values by offering nuggets of wisdom in short, rhyming verse.

The extended form, tanaga, a mono-riming heptasyllabic quatrain expressing insights and lessons on life is "more emotionally charged than the terse proverb and thus has affinities with the folk lyric." Some examples are the basahanon or extended didactic sayings from Bukidnon and the daraida and daragilon from Panay.

The folk song, a form of folk lyric which expresses the hopes and aspirations, the people's lifestyles as well as their loves. These are often repetitive and sonorous, didactic and naive as in the children's songs or Ida-ida (Maguindanao), tulang pambata (Tagalog) or cansiones para abbing (Ibanag).

A few examples are the lullabyes or Ili-ili (Ilongo); love songs like the panawagon and balitao (Ilongo); harana or serenade (Cebuano); the bayok (Maranao); the seven-syllable per line poem, ambahan of the Mangyans that are about human relationships, social entertainment and also serve as a tool for teaching the young; work songs that depict the livelihood of the people often sung to go with the movement of workers such as the kalusan (Ivatan), soliranin (Tagalog rowing song) or the mambayu, a Kalinga rice-pounding song; the verbal jousts/games like the duplo popular during wakes.

Other folk songs are the drinking songs sung during carousals like the tagay (Cebuano and Waray); dirges and lamentations extolling the deeds of the dead like the kanogon (Cebuano) or the Annako (Bontoc).

A type of narrative song or kissa among the Tausug of Mindanao, the parang sabil, uses for its subject matter the exploits of historical and legendary heroes. It tells of a Muslim hero who seeks death at the hands of non-Muslims.

The folk narratives, i.e. epics and folk tales are varied, exotic and magical. They explain how the world was created, how certain animals possess certain characteristics, why some places have waterfalls, volcanoes, mountains, flora or fauna and, in the case of legends, an explanation of the origins of things. Fables are about animals and these teach moral lessons.

Our country's epics are considered ethno-epics because unlike, say, Germany's Niebelunginlied, our epics are not national for they are "histories" of varied groups that consider themselves "nations."

The epics come in various names: Guman (Subanon); Darangen (Maranao); Hudhud (Ifugao); and Ulahingan (Manobo). These epics revolve around supernatural events or heroic deeds and they embody or validate the beliefs and customs and ideals of a community. These are sung or chanted to the accompaniment of indigenous musical instruments and dancing performed during harvests, weddings or funerals by chanters. The chanters who were taught by their ancestors are considered "treasures" and/or repositories of wisdom in their communities.

Examples of these epics are the Lam-ang (Ilocano); Hinilawod (Sulod); Kudaman (Palawan); Darangen (Maranao); Ulahingan (Livunganen-Arumanen Manobo); Mangovayt Buhong na Langit (The Maiden of the Buhong Sky from Tuwaang--Manobo); Ag Tobig neg Keboklagan (Subanon); and Tudbulol (T'boli).

The Spanish Colonial Tradition

While it is true that Spain subjugated the Philippines for more mundane reasons, this former European power contributed much in the shaping and recording of our literature. Religion and institutions that represented European civilization enriched the languages in the lowlands, introduced theater which we would come to know as komedya, the sinakulo, the sarswela, the playlets and the drama. Spain also brought to the country, though at a much later time, liberal ideas and an internationalism that influenced our own Filipino intellectuals and writers for them to understand the meanings of "liberty and freedom."

Literature in this period may be classified as religious prose and poetry and secular prose and poetry.

Religious lyrics written by ladino poets or those versed in both Spanish and Tagalog were included in early catechism and were used to teach Filipinos the Spanish language. Fernando Bagonbanta's "Salamat nang walang hanga/gracias de sin sempiternas" (Unending thanks) is a fine example that is found in the Memorial de la vida cristiana en lengua tagala (Guidelines for the Christian life in the Tagalog language) published in 1605.

Another form of religious lyrics are the meditative verses like the dalit appended to novenas and catechisms. It has no fixed meter nor rime scheme although a number are written in octosyllabic quatrains and have a solemn tone and spiritual subject matter.

But among the religious poetry of the day, it is the pasyon in octosyllabic quintillas that became entrenched in the Filipino's commemoration of Christ's agony and resurrection at Calvary. Gaspar Aquino de Belen's "Ang Mahal na Passion ni Jesu Christong Panginoon natin na tola" (Holy Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ in Verse) put out in 1704 is the country's earliest known pasyon.

Other known pasyons chanted during the Lenten season are in Ilocano, Pangasinan, Ibanag, Cebuano, Bicol, Ilongo and Waray.

Aside from religious poetry, there were various kinds of prose narratives written to prescribe proper decorum. Like the pasyon, these prose narratives were also used for proselitization. Some forms are: dialogo (dialogue), Manual de Urbanidad (conduct book); ejemplo (exemplum) and tratado (tratado). The most well-known are Modesto de Castro's "Pagsusulatan ng Dalawang Binibini na si Urbana at si Feliza" (Correspondence between the Two Maidens Urbana and Feliza) in 1864 and Joaquin Tuason's "Ang Bagong Robinson" (The New Robinson) in 1879, an adaptation of Daniel Defoe's novel.

Secular works appeared alongside historical and economic changes, the emergence of an opulent class and the middle class who could avail of a European education. This Filipino elite could now read printed works that used to be the exclusive domain of the missionaries.

The most notable of the secular lyrics followed the conventions of a romantic tradition: the languishing but loyal lover, the elusive, often heartless beloved, the rival. The leading poets were Jose Corazon de Jesus (Huseng Sisiw) and Francisco Balagtas. Some secular poets who wrote in this same tradition were Leona Florentino, Jacinto Kawili, Isabelo de los Reyes and Rafael Gandioco.

Another popular secular poetry is the metrical romance, the awit and korido in Tagalog. The awit is set in dodecasyllabic quatrains while the korido is in octosyllabic quatrains. These are colorful tales of chivalry from European sources made for singing and chanting such as Gonzalo de Cordoba (Gonzalo of Cordoba) and Ibong Adarna (Adarna Bird). There are numerous metrical romances in Tagalog, Bicol, Ilongo, Pampango, Ilocano and in Pangasinan. The awit as a popular poetic genre reached new heights in Balagtas' "Florante at Laura" (ca. 1838-1861), the most famous of the country's metrical romances.

Again, the winds of change began to blow in 19th century Philippines. Filipino intellectuals educated in Europe called ilustrados began to write about the downside of colonization. This, coupled with the simmering calls for reforms by the masses gathered a formidable force of writers like Jose Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Mariano Ponce, Emilio Jacinto and Andres Bonifacio.

This led to the formation of the Propaganda Movement where prose works such as the political essays and Rizal's two political novels, Noli Me Tangere and the El filibusterismo helped usher in the Philippine revolution resulting in the downfall of the Spanish regime, and, at the same time planted the seeds of a national consciousness among Filipinos.

But if Rizal's novels are political, the novel Ninay (1885) by Pedro Paterno is largely cultural and is considered the first Filipino novel. Although Paterno's Ninay gave impetus to other novelists like Jesus Balmori and Antonio M. Abad to continue writing in Spanish, this did not flourish.

Other Filipino writers published the essay and short fiction in Spanish in La Vanguardia, El Debate, Renacimiento Filipino, and Nueva Era. The more notable essayists and fictionists were Claro M. Recto, Teodoro M. Kalaw, Epifanio de los Reyes, Vicente Sotto, Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, Rafael Palma, Enrique Laygo (Caretas or Masks, 1925) and Balmori who mastered the prosa romantica or romantic prose.

But the introduction of English as medium of instruction in the Philippines hastened the demise of Spanish so that by the 1930s, English writing had overtaken Spanish writing. During the language's death throes, however, writing in the romantic tradition, from the awit and korido, would continue in the novels of Magdalena Jalandoni. But patriotic writing continued under the new colonialists. These appeared in the vernacular poems and modern adaptations of works during the Spanish period and which further maintained the Spanish tradition.

The American Colonial Period

A new set of colonizers brought about new changes in Philippine literature. New literary forms such as free verse [in poetry], the modern short story and the critical essay were introduced. American influence was deeply entrenched with the firm establishment of English as the medium of instruction in all schools and with literary modernism that highlighted the writer's individuality and cultivated consciousness of craft, sometimes at the expense of social consciousness.

The poet, and later, National Artist for Literature, Jose Garcia Villa used free verse and espoused the dictum, "Art for art's sake" to the chagrin of other writers more concerned with the utilitarian aspect of literature. Another maverick in poetry who used free verse and talked about illicit love in her poetry was Angela Manalang Gloria, a woman poet described as ahead of her time. Despite the threat of censorship by the new dispensation, more writers turned up "seditious works" and popular writing in the native languages bloomed through the weekly outlets like Liwayway and Bisaya.

The Balagtas tradition persisted until the poet Alejandro G. Abadilla advocated modernism in poetry. Abadilla later influenced young poets who wrote modern verses in the 1960s such as Virgilio S. Almario, Pedro I. Ricarte and Rolando S. Tinio.

While the early Filipino poets grappled with the verities of the new language, Filipinos seemed to have taken easily to the modern short story as published in the Philippines Free Press, the College Folio and Philippines Herald. Paz Marquez Benitez's "Dead Stars" published in 1925 was the first successful short story in English written by a Filipino. Later on, Arturo B. Rotor and Manuel E. Arguilla showed exceptional skills with the short story.

Alongside this development, writers in the vernaculars continued to write in the provinces. Others like Lope K. Santos, Valeriano Hernandez Peña and Patricio Mariano were writing minimal narratives similar to the early Tagalog short fiction called dali or pasingaw (sketch).

The romantic tradition was fused with American pop culture or European influences in the adaptations of Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan by F. P. Boquecosa who also penned Ang Palad ni Pepe after Charles Dicken's David Copperfield even as the realist tradition was kept alive in the novels by Lope K. Santos and Faustino Aguilar, among others.

It should be noted that if there was a dearth of the Filipino novel in English, the novel in the vernaculars continued to be written and serialized in weekly magazines like Liwayway, Bisaya, Hiligaynon and Bannawag.

The essay in English became a potent medium from the 1920's to the present. Some leading essayists were journalists like Carlos P. Romulo, Jorge Bocobo, Pura Santillan Castrence, etc. who wrote formal to humorous to informal essays for the delectation by Filipinos.

Among those who wrote criticism developed during the American period were Ignacio Manlapaz, Leopoldo Yabes and I.V. Mallari. But it was Salvador P. Lopez's criticism that grabbed attention when he won the Commonwealth Literay Award for the essay in 1940 with his "Literature and Society." This essay posited that art must have substance and that Villa's adherence to "Art for Art's Sake" is decadent.

The last throes of American colonialism saw the flourishing of Philippine literature in English at the same time, with the introduction of the New Critical aesthetics, made writers pay close attention to craft and "indirectly engendered a disparaging attitude" towards vernacular writings -- a tension that would recur in the contemporary period.

The Contemporary Period

The flowering of Philippine literature in the various languages continue especially with the appearance of new publications after the Martial Law years and the resurgence of committed literature in the 1960s and the 1970s.

Filipino writers continue to write poetry, short stories, novellas, novels and essays whether these are socially committed, gender/ethnic related or are personal in intention or not.

Of course the Filipino writer has become more conscious of his art with the proliferation of writers workshops here and abroad and the bulk of literature available to him via the mass media including the internet. The various literary awards such as the Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature, the Philippines Free Press, Philippine Graphic, Home Life and Panorama literary awards encourage him to compete with his peers and hope that his creative efforts will be rewarded in the long run.

With the new requirement by the Commission on Higher Education of teaching of Philippine Literature in all tertiary schools in the country emphasizing the teaching of the vernacular literature or literatures of the regions, the audience for Filipino writers is virtually assured. And, perhaps, a national literature finding its niche among the literatures of the world will not be far behind.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the Filipino Culture like?

Take it from Rachel Bloom when it comes to culture. Plus, there’s a diverse range of heritages within the Filipino Culture as well as the Native Filipino culture.

For a fact, I know that I have some sort of Spanish heritage linked with Chinese descent but I don’t take that as being pure Filipino since there’s no such thing as a pure Filipino because of much people forget to mention in History books. I recently watched a European Spanish film about the last Spanish men in the Philippines and I learned a lot of what they had to deal with in order to get by.

For example, CONSTANTINO. It’s probably a surname of one of the Spanish colonizers making his way to the Philippines. Along with Mendoza, Rosales, Cruz, Rayes, etc.

There’s a few other Filipino Cultures to look up, as well:

Filipino-Spanish

Filipino-Chinese

British-Filipino

Filipino-American

Native Filipinos - these are the people who are a descendants of the people who founded the country long before the Spanish took over.

just to name a few.

It is important to know that you would rarely find anyone living in the Philippines who are Native Filipinos because of how colonizers treated Filipina women when they first arrived in the country. Also, Filipinx Feminists are hard to find as well since not everyone is willing to change the Philippine Society for the future generation. It’s all about leaving a mark in the country and leaving a legacy for the future family members to follow.

Confession: I’m not about that. I’m actually one of the people who wants a certain change in society and how people views politics.

If you are into Feminism, there’s four Filipinas that you should look up. They’re kind of the earliest Feminist in Philippine history, but people are saying that it’s Marjorie Evasco when it’s not. She’s a Modern Filipinx Feminist.

Gabriela Silang - first documented Filipina feminist, I think.

Leona Florentino - first known Filipino feminist poet.

Aurora Quezón aka Nene

Corazon Aquino and the People Power - she practically lead it.

This is probably an essay by now, but it’s the only way that I can explain what it’s like in the Filipino Community/Culture without being straight forward and one-sided about the culture itself.

1 note

·

View note