#lerner publishing group

Text

Artie and the Wolf Moon

The cover struck me. Its use of colour is so striking. Then I opened the book and saw the chapter title page was a black and white polaroid. It is one of the most stunning pages in the whole book. And it’s so, so atmospheric. The way Stephens illustrates the night is so visceral. But in colour? Amazing. But I love that first polaroid not just because it stole my breath but because it’s Artie.…

View On WordPress

#Artie and the Wolf Moon#Book Review#Books#Fantasy#Graphic Novel#Lerner Publishing Group#Middle Grade#Olivia Stephens#queer#Review#Werewolves

1 note

·

View note

Text

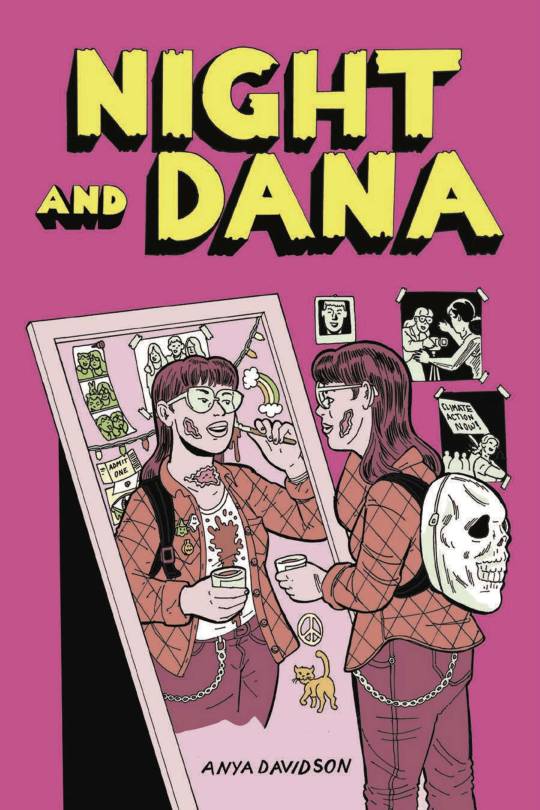

Preview: Night and Dana

Night and Dana preview. When a messy prank gets the wrong kind of attention, special-effects obsessives Dana Drucker and Lily Villaseñor must find a new creative outlet or leave high school without graduating #comics #comicbooks #graphicnovel

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Operation Pangolin: Saving the World’s Only Scaled Mammal by Suzi Eszterhas

Operation Pangolin: Saving the World’s Only Scaled Mammal by Suzi Eszterhas

Operation Pangolin: Saving the World’s Only Scaled Mammal by Suzi Eszterhas. Millbrook Press/ Lerner, 2022. 9781728442952

Rating: 1-5 (5 is an excellent or a Starred review) 5

Format: Hardcover

What did you like about the book? There are eight different species of pangolins that live in parts of Africa and Asia. They are the only scaled mammal in the world and they are endangered due to being…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Big Bear, Little Fish, Great Friends

Big Bear, Little Fish, Great Friends @barbfisch @blueslipper @CarolrhodaLab @senickel

Big Bear and Little Fish, by Sandra Nickel/Illustrated by Il Sung Na, (Sept. 2022, Carolrhoda Books), $18.99, ISBN: 9781728417172

Ages 4-8

Bear goes to a carnival hoping to win a giant teddy bear, but wins a goldfish instead. Worried that she is too big to play with, feed, or love the tiny fish, she stays as far away from it as possible, lamenting the fact that she’s saddled with this little fish…

View On WordPress

#animals#bears#Big Bear and Little Fish#Carolrhoda#friendship#goldfish#Il Sung Na#kindness#Lerner Publishing Group#pets#Sandra Nickel#social themes

0 notes

Text

Rating: 5/5

Book Blurb: At first, no one noticed when I stopped talking at school. In this moving true story, Kao Kalia Yang shares her experiences as a young Hmong refugee navigating life at home and at school. Having seen the poor treatment her parents received when making their best efforts at speaking English, she no longer speaks at school. Kalia feels as though a rock has become lodged in her throat, and it grows heavier each day. Although the narrative is somber, it is also infused with moments of beauty, love, and hope.

Review:

This is a beautiful and touching story based on the life of the author in which a young girl becomes a selective mute after the experiences her parents face as refugees in a new country. This was a really beautiful story and reading the author's notes about what she went through and why she wrote this book made this an even better read.

*Thanks Netgalley and Lerner Publishing Group, Carolrhoda Books ® for sending me an arc in exchange for an honest review*

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review - Torch by Lyn Miller-Lachmann (🇨🇿 Czech Republic)

(image: Znojmo, Czech Republic; source: wikimedia commons)

Torch

Author: Lyn Miller-Lachmann

YA World Challenge Review for 🇨🇿 Czech Republic / newly Czechia / formerly Czechoslovakia

I had Czechia already in my queue for the world challenge per the randomizer, when this book fell right into my lap. I do still want to read Daughter of Smoke and Bone, set in Prague, which was my original pick. Torch being a historical novel set in communist Czechoslovakia is something completely different, and I'm sure my read pile can have room for both. :D

Review

Warning for suicide mention

The Prague Spring in 1968 Czechoslovakia brought unprecedented freedoms and a flood of previously banned Western media to the country. It was soon quashed by Soviet invasion. Torch opens in 1969, just after these happenings and after a university student, Jan Palach, sets himself on fire in protest (a true incident), signing a letter as “Torch No. 1″.

In the book, Miller-Lachmann imagines a fictional secondary student name Pavol who follows in Palach’s footsteps, committing suicide by fire after the State takes away his dream of university. The book follows three other teenagers in Pavol’s orbit and the fallout of his decision on their lives.

Štěpán, a closeted gay hockey player, Tomáš, a geeky autistic son of Communist party elites, and Lída, Pavol’s girlfriend and life-long roamer due to her father’s alcoholism, were previously only connected by their friendship with Pavol. With Pavol’s final act of rebellion, they now find themselves under suspicion by the brutal state system that aims to crush and extinguish all dissent.

Besides, what had her father told her? This is how you survive with your soul intact. Never name anyone. You saw nothing. You heard nothing. You have nothing to say.

Like the Prague Spring’s dream for “socialism with a human face”, Miller-Lachmann gives us a tapestry of human faces amid the bleak, unforgiving world of 20th century communism. It was Pavol’s wish to reform the country from within, but In the face of failed revolution, the three teenagers must decide if love for country is worth more than their crushed dreams, under a government that views anything “different” as a crime. With Lída, pregnant with Pavol’s child, she must decide if she will allow the state to rob her child of any future, simply for the crimes of his father.

“It’s all right to be scared. We’re different. They don’t want us to be different here. They want us to be the same.”

This is an insightful look at Czechoslovakia of the time through the eyes of a cast of outcasts, with an action-filled ending and liberally sprinkled with Walt Whitman. I love the diversity of the cast, and the nuanced look at political views (for example, the characters are opposed to the harsh government censorship, while also wary of the rampant unemployment they have been taught exists in the capitalist West) at a complicated period in Czechoslovakia’s history. I highly recommend it to anyone interested in historical fiction.

It releases on November 1, 2022.

Buy it at Bookshop.org | Amazon

Genres: #friendship #activism #political #historical, 20th century

Other reps: #gay #neurodivergent (autistic) #catholic

★ ★ ★ ★ 4 stars

Content warnings at Storygraph

Thanks to Netgalley and Lerner Publishing Group for an advanced copy.

#book review#czech republic#reading#bookaddict#booklr#czechoslovakia#ya world challenge#historical fiction#gay#neurodivergent#historical 20th century#political#activism#friendship#communism#eastern europe#europe#torch#lyn miller-lachmann

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Torch review

4/5 stars

Recommended for people who like: historical fiction, Cold War, multiple POVs, friendships, grief stories, lGBTQ+ characters, austism rep

Big thanks to Netgalley, Lerner Publishing Group, and the author for an ARC of this book in exchange for an honest review!

TW: torture, alcoholism

I think, above all, this is a story of grief. Of a group of very different people being united in their shared sorrow for the death of a mutual friend. Pavol's actions leave a void behind for everyone involved. One that quickly gets filled with the State Security's scrutiny and punishments, but also by a burgeoning friendship between the three narrating characters, Lída's father, and Pavol's younger sister. While the main focus of the story is, obviously, what they choose to do now that most of their futures are destroyed, the focus is also on how grief shapes each of them.

Štěpán is one of Pavol's closest friends: star hockey player, closeted, and bully. He's a difficult character to like at first. From Pavol's brief POV, Štěpán is someone who is trying to be a better person, but from just about everyone else's he can be harsh and sometimes violent. But he does get better over the course of the book, particularly after a certain incident. Štěpán's struggles are largely with himself and how he wants to (and can) present to the world. I enjoyed the poetic side of him and think that did give him depth. I also think he generally treats Lída well despite not really knowing her and her not fully fitting into their community.

Lída is probably my favorite character of the bunch (aside from Nika, but she's a side character). She's already faced the unjust rule of the communist party and made the best of it, so she's good at adapting. Lída also has an...interesting home life. Her dad is the town drunk and they live mostly sequestered in the woods, though both work at the factory. Despite having to often be the adult in the family, Lída's got a good head on her shoulders. She gets another rough shake by the State when they start subtly punishing her for being pregnant with Pavol's kid. While Lída herself may be content to try and go with the flow (mostly), when it comes to her future child, she develops a very action-oriented attitude and becomes the catalyst for the second half of the book.

Tomáš is the last POV character and is the son of the Party leader in the town they all live in. But that comes with its own issues, mainly that his father is abusive and constantly disappointed in him, and that his father combined with his shy and literal nature reward him with few friends. He's autistic coded and struggles to navigate the unwritten waters of Party rule. Tomáš's father surprisingly isn't that upset about Pavol's actions, but he does give Tomáš an invisible clock counting down the days until he either steps into line or faces the consequences of being branded 'antisocial.' Tomáš does try his best, though he struggles with some of the person-facing elements of it. I did feel as though he got pushed around somewhat, particularly toward the end of the book. Lída is right about his relationship with his father, but at the same time I do feel like Tomáš got manipulated at least a little by her and Štěpán. I also don't know how I feel about him and Štěpán becoming somewhat friends (full friends?) considering Štěpán's previous role in tormenting him.

Nika, Pavol's younger sister, is a pretty minor character, but she proves her mettle. She knows how things in Soviet Czechoslovakia go and wants no part in it, particularly when she can read the way the wind is blowing for her family. She's pretty clever and I liked that she and Lída were able to take comfort in each other.

Ondřej, Lída's father, is drunk more often than not, with the implication that he's drinking to forget his partisan days during WWII. He's not the best influence, and there's definitely tension between him and Lída due to him drinking with Pavol, but he does clearly love his daughter and is willing to do anything for her. The arc of his story is sad, but I did enjoy his character.

I really think the escape debate is entertaining because, like...Lída is pretty determined to do it so her and her father come up with a plan. Then Štěpán ends up in more trouble and Lída is like 'well I guess we'll take him,' and then everything kind of snowballs from there. Other than Lída and Ondřej, each of the characters has to debate with themselves whether it's worth it to leave or if they can manage to continue working within the confines of the Party for the (sometimes few) benefits it provides them.

Overall I enjoyed the book and most of the character relationships. I do feel like there's a bit of a lull between everything with Pavol and the investigation and the catalyst for everyone needing to decide whether to stay or go, but the first third and last third are both pretty action-packed.

#book#bookish#bookblr#bookworm#books#bookshelf#books and reading#book recommendations#book review#booklr#bookstagram#netgalley#netgalley review#netgalley read#ya fiction#ya books#bookaholic#bookaddict#historical fiction#lgbtq characters#tw torture#czechoslovakia#multiple povs#autistic characters#tw alchoholism

1 note

·

View note

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Lotsa Matzah By Tilda Balsley (Hardcover Picture Book).

0 notes

Text

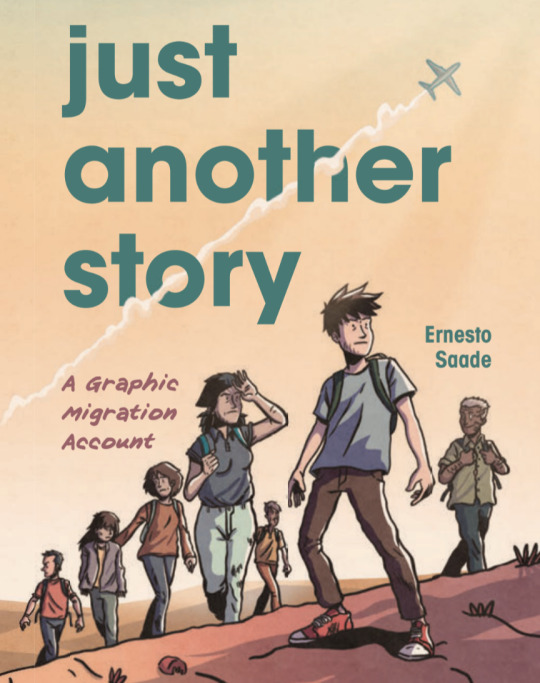

Just Another Story: A Graphic Migration Account | Comic Review

Just Another Story: A Graphic Migration Account | Comic Review #JustAnotherStory #NetGalley

I recently had the pleasure of reading Just Another Story: A Graphic Migration Account from Ernesto Saade, and I really enjoyed it. Based on true events, the book tells the story of the difficulties and dangers that come with immigrating to the United States from Central America. It’s a beautiful story, and I hope you read it.

The structure of the book follows Ernesto from El Salvador who is visiting his cousin Carlos and aunt Elena in San Diego. When Carlos picks Ernest up at LAX and they head to San Diego, Ernesto asks Carlos to tell him about their journey from El Salvador to the US. Carlos mentions that he’s never talked about what he and his mom went through with anyone before. Then, our story takes off.

Just Another Story is a grand reminder that the sacrifices and dangers faced by immigrants just to get to the USA are rarely in the “immigration debate” had in this country. Dealing with the smugglers, gangs, and crooked cops is a dangerous path that many do not survive.

At the end of the book, Elena is considering her future. While she loves her son and the life that they have been able to build in the USA over the last decade, she misses her family and El Salvador. However, until their visa situation is officially settled, they would not be able to return to the USA if they left. She has a wonderful bit of dialogue in a conversation with Ernesto while they watch Carlos surf in the ocean:

“People tell me that going back would be like admitting I made a mistake. Some kind of failure. But I don’t see it that way. My son is doing well. He has a bright future ahead of him. I believe I already accomplished something. And I’m not going to apologize nor feel shame for trying to find my own happiness.”

Just Another Story: A Graphic Migration Account – digital page 211.

I loved the way that Saade illustrated this book. It’s split into three different styles, so you always know where you are in the story. When the book is following Carlos and Ernesto, the book emphasizes the blues, greys, and greens. When we transition to Carlos and his mother Elena’s journey to the USA, the book has the full pantheon, edging darker when a dangerous situation is involved. When another character is telling a story such as Peligro, the colors are more bold. It made it easy to know who was “talking” at any given point.

Saade wrote and illustrated an excellent and moving story, and I highly recommend it.

Thank you NetGalley and Lerner Publishing Group for sending this book for review consideration. All opinions are my own.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Multicultural Children's Book Day Part 2

This year, I was also gifted The Jake Show by Joshua Levy! The book was published by Katherine Tegen Books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishing (harpercollins.com). Joshua is Jewish Florida native who has written several middle grade books.

Jake is a TV-loving kid who is being pulled between two different worlds: The devout "yiddishkeit" of living with his mother and the secular, STEM encouraging of living with his father. Shuffled from school to school and between these two worlds, Jake has mastered the art of masking, but with the guidance of some excellent friends (and a few close-calls along the way), learns that he can't be both the person his mom wants him to be and the person his dad wants him to be at the same time (let alone himself).

I really connected with Jake and the need to perform differently for different groups of people. I also remembered the feeling of starting in a new school and feeling like it would only be temporary. While adjusting to the Jewish vocabulary in the beginning was a little difficult for me (Jake did a great job at providing subtitles for things a few chapters in), this book was a great read! Jake's story will resonate with readers trying to parse out who they are/who they want to be. I'm so excited to add this book to the shelves in my library!

Multicultural Children’s Book Day 2024 (1/25/24) is in its 11th year! Valarie Budayr and Mia Wenjen founded this non-profit children’s literacy initiative; they are two diverse book-loving moms who saw a need to shine the spotlight on all of the multicultural diverse books and authors on the market while also working to get those books into the hands of young readers and educators.

Read Your World’s mission is to raise awareness of the need to include kids’ books celebrating diversity in homes and school bookshelves. Read about our Mission and history HERE.

lh7-us.googleusercontent.com

Read Your World celebrates Multicultural Children’s Book Day and is honored to be Supported by these Medallion and Ruby Sponsors!

FOUNDER’S CIRCLE: Mia Wenjen (Pragmaticmom) and Valarie Budayr (Audreypress.com)

🏅 Super Platinum Sponsor: Author Deedee Cummings and Make A Way Media

🏅 Platinum Sponsors: Publisher Spotlight, Language Lizard Bilingual Books in 50+ Languages, Lerner Publishing Group, Children’s Book Council

🏅 Gold Sponsors: Barefoot Books, Astra Books for Young Readers

🏅 Silver Sponsors: Red Comet Press, Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, Valerie Williams-Sanchez and Valorena Publishing, Lee and Low Books, Cardinal Rule Press

🏅 Bronze Sponsors: CK Malone, Tonya Duncan Ellis, Anita Crawford Clark, Star Bright Books, Blue Dot Kids Press, Brunella Costagliola, Red Fin, Fabled Films

Ruby Sponsor: Crayola

lh7-us.googleusercontent.com

Poster Artist: Rebecca Burgess

lh7-us.googleusercontent.com

Classroom Kit Poster: Barefoot Books

MCBD 2024 is honored to be Supported by these Author Sponsors!

Authors: Gwen Jackson, Josh Funk, Eugenia Chu, Sivan Hong, Marta Magellan, Kathleen Burkinshaw, Angela H. Dale, Maritza M Mejia, Authors J.C. Kato and J.C.², Charnaie Gordon, Alva Sachs, Amanda Hsiung-Blodgett, Lisa Chong, Diana Huang, Martha Seif Simpson, DARIA (WORLD MUSIC WITH DARIA) Daria Marmaluk-Hajioannou, Gea Meijering, Stephanie M. Wildman, Tracey Kyle, Afsaneh Moradian, Kim C. Lee, Rochelle Melander, Beth Ruffin, Shifa Saltagi Safadi, Alina Chau, Michael Genhart, Sally J. Pla, Ajuan Mance, Kimberly Marcus, Lindsey Rowe Parker

MCBD 2024 is Honored to be Supported by our CoHosts and Global CoHosts!

MCBD 2023 is Honored to be Supported by our Partner Organizations!

Check out MCBD's Multicultural Books for Kids Pinterest Board!

📌 FREE RESOURCES from Multicultural Children’s Book Day

MCBD 2024 Poster

Mental Health Support for Stressful Times Classroom Kit

Diversity Book Lists & Activities for Teachers and Parents

Homeschool Diverse Kidlit Booklist & Activity Kit

FREE Teacher Classroom Activism and Activists Kit

FREE Teacher Classroom Empathy Kit

FREE Teacher Classroom Kindness Kit

FREE Teacher Classroom Physical and Developmental Challenges Kit

FREE Teacher Classroom Poverty Kit

Gallery of Our Free Posters

FREE Diversity Book for Classrooms Program

📌 Register for the MCBD Read Your World Virtual Party

Join us on Thursday, January 25, 2024, at 9 pm EST celebrating more than 10 years of Multicultural Children's Book Day Read Your World Virtual Party! Register here.

This epically fun and fast-paced hour includes multicultural book discussions, addressing timely issues, diverse book recommendations, & reading ideas.

We will be giving away a 10-Book Bundle during the virtual party plus Bonus Prizes as well! *** US and Global participants welcome. **

Follow the hashtag #ReadYourWorld to join the conversation, and connect with like-minded parts, authors, publishers, educators, organizations, and librarians. We look forward to seeing you all on January 25, 2024, at our virtual party!

InLinkz - Linkups & Link Parties for Bloggers

Create link-ups, link parties and blog hops. Run challenges and engage your followers with Inlinkz.

FRESH.INLINKZ.COM

1 note

·

View note

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming

the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription,

so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction.

A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.

When Smith says that a woman “needed no bra—she was independent, even of gravity,” she is borrowing Dickens’s technique of making characters so intensely themselves that their essence saturates everything around them—as when he writes of the nouveau riche Veneerings, in Our Mutual Friend, that “their carriage was new, their harness was new, their horses were new, their pictures were new, they themselves were new.” Dickens is a guest star in The Fraud, appearing at several of William Ainsworth’s dinner parties, and the news of his death prompts Eliza Touchet to offer an apt tribute: “She knew she lived in an age of things . . . and Charles had been the poet of things.”

But Dickens, who at another point in the novel is gently disparaged for his moralizing “sermons,” is no longer the presiding genius of Smith’s fiction. (Smith wrote in a recent essay that her first principle in taking up the historical novel was “no Dickens,” and she expressed a wry disappointment that he had forced his way into the proceedings.) Her 2005 novel, On Beauty, was a reimagining of E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and while her style has continued to evolve from book to book, Forster’s influence has been clear ever since, in everything from her preference for short chapters to her belief in “keep[ing] one’s mind open.”

Smith’s affinity for Forster owes something to their analogous historical situations. An Edwardian liberal who lived into the age of fascism and communism, Forster defended his values—“tolerance, good temper and sympathy,” as he put it in the 1939 essay “What I Believe”—with something of a guilty conscience, recognizing that the militant younger generation regarded them as “bourgeois luxuries.”

At the end of The Fraud, Eliza encounters Mr. Bogle’s son Henry, who has grown disgusted with his father’s quietism and become a political radical. He reproaches her for being more interested in understanding injustice than in doing something about it, proclaiming:

By God, don’t you see that what young men hunger for today is not “improvement” or “charity” or any of the watchwords of your Ladies’ Societies. They hunger for truth! For truth itself! For justice!

This certainty and urgency is the opposite of keeping one’s mind open, and while Mrs. Touchet—and Smith—aren’t prepared to say that it is wrong, they are certain that it’s not for them: “This essential and daily battle of life he had described was one she could no more envisage living herself than she could imagine crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a hot air balloon.”

Whether they style themselves as humanists or aesthetes, realists or visionaries, the most powerful writers who were born in the Seventies share this basic aloofness. To the next generation, the millennials, their disengagement from the collective struggle may seem reprehensible. For me, as I suspect is the case for many readers my age, it is part of what makes them such reliable guides to understanding, if not the times we live in, then at least the disjunction between the times and the self that must try to negotiate them.

0 notes

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming

the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription,

so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction.

A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.

When Smith says that a woman “needed no bra—she was independent, even of gravity,” she is borrowing Dickens’s technique of making characters so intensely themselves that their essence saturates everything around them—as when he writes of the nouveau riche Veneerings, in Our Mutual Friend, that “their carriage was new, their harness was new, their horses were new, their pictures were new, they themselves were new.” Dickens is a guest star in The Fraud, appearing at several of William Ainsworth’s dinner parties, and the news of his death prompts Eliza Touchet to offer an apt tribute: “She knew she lived in an age of things . . . and Charles had been the poet of things.”

But Dickens, who at another point in the novel is gently disparaged for his moralizing “sermons,” is no longer the presiding genius of Smith’s fiction. (Smith wrote in a recent essay that her first principle in taking up the historical novel was “no Dickens,” and she expressed a wry disappointment that he had forced his way into the proceedings.) Her 2005 novel, On Beauty, was a reimagining of E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and while her style has continued to evolve from book to book, Forster’s influence has been clear ever since, in everything from her preference for short chapters to her belief in “keep[ing] one’s mind open.”

Smith’s affinity for Forster owes something to their analogous historical situations. An Edwardian liberal who lived into the age of fascism and communism, Forster defended his values—“tolerance, good temper and sympathy,” as he put it in the 1939 essay “What I Believe”—with something of a guilty conscience, recognizing that the militant younger generation regarded them as “bourgeois luxuries.”

At the end of The Fraud, Eliza encounters Mr. Bogle’s son Henry, who has grown disgusted with his father’s quietism and become a political radical. He reproaches her for being more interested in understanding injustice than in doing something about it, proclaiming:

By God, don’t you see that what young men hunger for today is not “improvement” or “charity” or any of the watchwords of your Ladies’ Societies. They hunger for truth! For truth itself! For justice!

This certainty and urgency is the opposite of keeping one’s mind open, and while Mrs. Touchet—and Smith—aren’t prepared to say that it is wrong, they are certain that it’s not for them: “This essential and daily battle of life he had described was one she could no more envisage living herself than she could imagine crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a hot air balloon.”

Whether they style themselves as humanists or aesthetes, realists or visionaries, the most powerful writers who were born in the Seventies share this basic aloofness. To the next generation, the millennials, their disengagement from the collective struggle may seem reprehensible. For me, as I suspect is the case for many readers my age, it is part of what makes them such reliable guides to understanding, if not the times we live in, then at least the disjunction between the times and the self that must try to negotiate them.

0 notes

Text

Preview: Unretouchable

Unretouchable preview. A window into the little-known, hugely influential world of fashion photography and a tribute to self-acceptance. #comics #comicbooks #graphicnovel

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nominees announced for the 2023 Ringo Awards

The nominees for the 2023 Ringo Awards have been announced, marking the seventh year for the awards program named for artist Mike Wieringo, who passed away in 2007.

Nominees were chosen by fans, along with a panel of judges. The awards presentation will take place at The Baltimore Comic-Con on Sept. 9.

And this year’s nominees are …

Best Cartoonist (Writer/Artist)

Kate Beaton

Wes Craig

Alexis Deacon

Jenny Jinya

Snailords

Stan Sakai

Zoe Thorogood

Best Writer

Ed Brubaker

Anthony Del Col

Drew Edwards

Scott Snyder

Brian K. Vaughan

Best Artist or Penciller

Fahmida Azim

Kate Flynn

Molly Mendoza

Nicola Scott

Evan “Doc” Shaner

Best Inker

Gigi Baldassini

Scott Hanna

Sandra Hope

Klaus Janson

Mark Morales

Best Letterer

Justin Birch

Jerome Gagnon

Todd Klein

Micah Myers

Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou

Stan Sakai

Best Colorist

Daniela Barisone

Jordie Bellaire

Chris O’Halloran

Jacob Phillips

Dave Stewart

Ellie Wright

Best Cover Artist

Wylie Beckert

Jason Muhr

Bryan Silverbax

Greg Smallwood

JH Williams III

Best Series

Fractured Shards, Comics2Movies

Parker Girls, Abstract Studios

Saga, Image Comics

Season of the Bruja, Oni Press

Something is Killing the Children, BOOM! Studios

Best Single Issue or Story

88 Days of Hell: One Ukrainian Man’s Experience in the Russian Filtration, Insider

A Hunter’s Tale, Elephant Eater Comics

Finding Batman, DC Comics

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters, Oni Press

Punisher #1, Marvel Comics

Thieves, Nobrow

You Were My Joker That Night, Anatola Howard

Best Original Graphic Novel

Chivalry, Dark Horse Comics

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, Drawn & Quarterly

It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth, Image Comics

Tokyo Rose—Zero Hour: A Japanese American Woman’s Persecution and Ultimate Redemption After World War II, Tuttle Publishing

Twilight Custard, Ghostpod Publishing

Best Anthology

Cthulu Invades Wonderland, Orange Cone Productions

Lower Your Sights, Mad Cave Studios

The Silver Coin, Image Comics

Voices That Count, IDW Publishing

Young Men in Love, A Wave Blue World

Best Humor Comic

Breaking Cat News, GoComics

Crash and Troy, A Wave Blue World

Grumpy Monkey: Who Threw That?, Random House Children’s Books

The Illustrated Al: The Songs of “Weird Al” Yankovic, Z2 Comics

Little Tunny’s Snail Diaries, Silver Sprocket

My Bad, AHOY Comics

Revenge of the Librarians, Drawn & Quarterly

Whatzit, Heavy Metal

Best Webcomic

88 Days of Hell: One Ukrainian Man’s Experience in the Russian Filtration, Inisder

The All-Nighter, Comixology Originals

The Guy Upstairs, WEBTOON

I Love Yoo, WEBTOON

Lore Olympus, WEBTOON

Offside: I Was a Pro Football Player. I Was Tricked into Going to Qatar to Work Construction, Insider

You Were My Joker That Night, Anatola Howard

Best Humor Webcomic

Background Noise, backgroundnoisecomic.com

Evil Inc., evil-inc.com

Finding Fiends, WEBTOON

Live with Yourself!, WEBTOON

Vampire Husband, WEBTOON

Best Non-fiction Comic Work

88 Days of Hell: One Ukrainian Man’s Experience in the Russian Filtration, Insider

A Game for Swallows Expanded Edition, Graphic Universe – Lerner Publishing Group

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, Drawn & Quarterly

I’m Still Alive, Archaia – BOOM! Studios

Just Another Meat-Eating Dirtbag, Street Noise Books

Radium Girls, Iron Circus Comics

The Third Person, Drawn & Quarterly

Best Kids Comic or Graphic Novel

The Aquanaut, Scholastic Graphix

Frizzy, First Second Books

The Ghoul Agency, Action Lab Entertainment

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters, Oni Press

Kaya, Image Comics

PAWS: Gabby Gets It Together, Razorbill Books, Penguin Random House

Punk Taco 2, Adam Wallenta Entertainment

Tin Man, Abrams ComicArts

Best Presentation in Design

Beneath an Alien Sky, Rocketship Entertainment

Best of EC Stories Artisan Edition, IDW Publishing

Richard Stark’s Parker: The Martini Edition—Last Call, IDW Publishing

Ronan and the Endless Sea of Stars, Abrams ComicArts

Sara Deluxe Hardcover, TKO Studios

0 notes

Text

New robotic arm on the Kolling Institute to drive joint alternative in Australia

A brand new robotic arm at the Kolling Institute, a three way partnership between the Northern Sydney Native Well being District and the College of Sydney, is seen to enhance hip and knee replacements in Australia.

WHAT IT DOES

Known as KOBRA (Kolling Orthopaedic Biomechanics Robotic Arm), the orthopaedic biomechanics robotic is without doubt one of the solely two robots within the nation that’s primarily based on simVitro – a {hardware} impartial joint testing system that got here out of the Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Analysis Institute.

The robotic simulates complicated human actions on joints to supply researchers with a “clearer image” of how joints will carry out in varied conditions, defined Elizabeth Clarke, affiliate professor on the College of Sydney and the director of the Kolling Institute’s Murray Maxwell Biomechanics Laboratory.

It will possibly check complicated actions and actions that contain compression and twisting like hip flexing, squatting, strolling and throwing.

KOBRA’s improvement was backed by the NSW Funding Boosting Enterprise Innovation program and the Royal North Shore Hospital Employees Specialist Belief Fund.

WHY IT MATTERS

Based mostly on a media launch, KOBRA is predicted for use to check implants, significantly for hip and knee replacements, to gauge how the implants will work. It should even be used to assist validate pc fashions that help surgeons within the placement of implants. Moreover, the robotic shall be doubtless used to help surgeons working to restore persistent shoulder instability.

Furthermore, researchers are in search of to use the knowledge and knowledge offered by KOBRA throughout disciplines, extending analysis capabilities and resulting in new surgical strategies.

MARKET SNAPSHOT

Simply final 12 months, Smith+Nephew, a British medtech firm, launched in Australia and New Zealand its handheld robotics resolution for unicompartmental and whole knee arthroplasties. The US FDA-approved CORI Surgical System is claimed to be supreme for ambulatory surgical procedure centres and outpatient surgical procedure.

ON THE RECORD

“It’s a very thrilling time for musculoskeletal analysis and surgical procedure and it’s tremendously encouraging to see this world-leading expertise coming to the Kolling Institute. It should help researchers, engineers and surgeons, and finally result in improved surgical strategies, higher bodily perform and good long-term well being outcomes for our group,” commented Invoice Walter, professor of Orthopaedics and Traumatic Surgical procedure on the College of Sydney and an orthopaedic surgeon on the Royal North Shore Hospital.

Originally published at San Jose News HQ

0 notes

Text

Picture Book Review: Be a Bridge by Irene Latham

Here's my review for The Bridge by Irene Latham! This is such a beautiful book and a great message for kids!

Title: Be a Bridge

Author: Irene Latham

Publisher: Carolrhoda Books, Lerner Publishing Group

Published: August 2, 2022

Pages: 36

Format: Netgalley e-arc. Thanks, Carolrhoda Books!

Netgalley Blurb

“In this upbeat picture book, acclaimed authors Irene Latham and Charles Waters bring key themes from their earlier collaborations (Can I Touch Your Hair? and Dictionary for a Better World) to a…

View On WordPress

#amreading#blogger#book addict#Book blog#book blogger#book bloggers#book love#book lover#Book Review#book reviewer#Book Talk#book worm#bookaholic#bookish#bookish blog#review#reviewer

0 notes