#les photos d'alix

Text

Jean Eustache ha cerrado los ojos

La prematura muerte —tenía cuarenta y tres años— de Jean Eustache, arrebata al cine francés una de sus más firmes promesas de vitalidad y renovación.

Con muy pocas películas, Eustache se había convertido en una de las secretas «cabezas buscadoras» del cine de su país, de las que apenas —o muy de tarde en tarde— se habla, pero que van abriendo caminos o desbrozando de convenciones acumuladas los olvidados senderos de la tradición. Demasiado urbano para ser descubridor o explorador, fue un buen detective y un gran deshollinador; por eso le acusaron de suciedad la única vez que fue noticia, y no —como de costumbre— sólo confidencia, contraseña entre afines, secreto bien guardado —casi atesorado— por los que lo conocían; el propio cineasta descartó la exhibición de algunos de sus films. Como Maurice Pialat —que tiene ya cincuenta y seis años y sólo ha dirigido cinco largometrajes—, Eustache ha hecho una obra original e importante, pero sin pretensiones, siempre al margen: demasiado largas (casi cuatro horas dura, irremediablemente, La maman et la putain) o cortas (Le Père Noël a les yeux bleus), de apariencia banal (La Rosière de Pessac) o perversa (Une sale histoire), pero sin complacencia, sus películas eran cosa suya, saltos al vacío, sin contar con el público ni para volverle la espalda o molestarle. Sólo una vez —por falsas, si no malas razones; por un equívoco del que fue víctima entre sus amigos— alcanzó cierto renombre, cuando se exhibió su film más audaz, conmovedor, agobiante y terrible, para ser olvidado al año siguiente, cuando estrenó otra obra maestra, Mes petites amoureuses, aún más discreta y recóndita; tan austera y apartada del sentimentalismo como la primera de Pialat, L'enfance nue, de la que podría considerarse una especie de continuación libre.

Pero —y esto es lo terrible— estoy hablando de películas que la mayor parte de los lectores conocerán, si acaso, de oídas (o de leídas), pues ninguna de las pocas que hizo ha llegado a estrenarse en España, aunque varias se proyectasen en la Filmoteca. Mientras Truffaut, Chabrol o Rohmer —con excepciones y en desorden— acaban por iluminar nuestras pantallas, gente como Rivette, Pialat o Vecchiali son casi desconocidos, y Eustache permanece inédito. Tal vez ahora —demasiado tarde para la esperanza, aunque más vale tarde que nunca— el prestigio que da la muerte a cambio de la vida y el futuro anime a algún distribuidor —aunque lo dudo— a correr el riesgo que supone poner al alcance del público obras tan desesperadas, tan humorísticas, tan duras y sobrias, tan poco llamativamente personales.

Truffaut dijo una vez —cuando se llevaba bien con Godard— que el Michel Poiccard de À bout de souffle era el hijo engendrado por Jean Dasté y Dita Parlo en L'Atalante. La maman et la putain puede considerarse legítima heredera, si no consecuencia directa, del Godard que vibró de À bout de souffle a Masculin féminin, pasando por Le mépris, Bande à part y Pierrot le fou, pero la obra de Eustache en su conjunto, como todo el nuevo cine francés que realmente cuenta, parte de la confluencia de dos grandes cineastas del pasado, el Renoir de La Bête humaine, Boudu sauvé des eaux y Toni, y el Vigo de L'Atalante y Zéro de conduite, para llegar a encrucijadas nuevas y diversas. Ya nunca sabremos a dónde conducía la trayectoria de Jean Eustache, aunque nos quedan, eso sí, las etapas quemadas: Les mauvaises fréquentations (1963), Le Père Noël a les yeux bleus (1966), La Rosière de Pessac (1968), Le cochon (1970), Numéro zéro (1971), La maman et la putain (1973), Mes petites amoureuses (1974), Une sale histoire (1977), la segunda Rosière (1979), Le jardin des délices de Jérôme Bosch y Les photos d'Alix (1980). Las cinco que he tenido ocasión de ver, todas muy diferentes entre sí, son películas sorprendentes, conmovedoras e impresionantes, que apuntan o llevan al límite las múltiples posibilidades del cine, sin descartar ninguna.

Lo último que se supo de Eustache, antes de la noticia de su muerte en noviembre, fue la publicación (en el núm. 323-324 de Cahiers du Cinéma, mayo de 1981) de un texto terrible, en primera persona, acerca de la soledad, la enfermedad y la muerte, que parece extraído de un diario, aunque se presentaba como «fragmentos de un guión abandonado» y bajo el titulo ambiguo de Peine perdue. Esperemos que la obra de Eustache no quede, dentro de unos años, como un ejemplo de «esfuerzo perdido», porque sería una «pena inútil».

Publicado en el nº 12 de Casablanca (diciembre de 1981)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

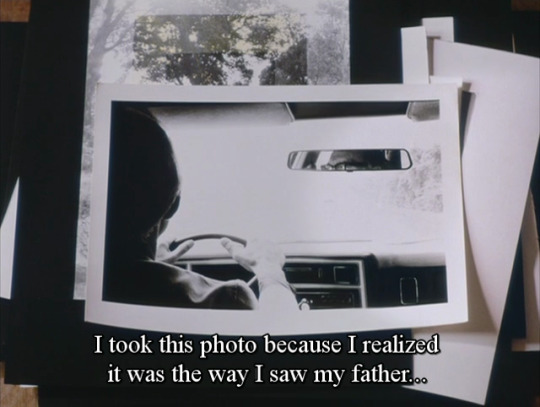

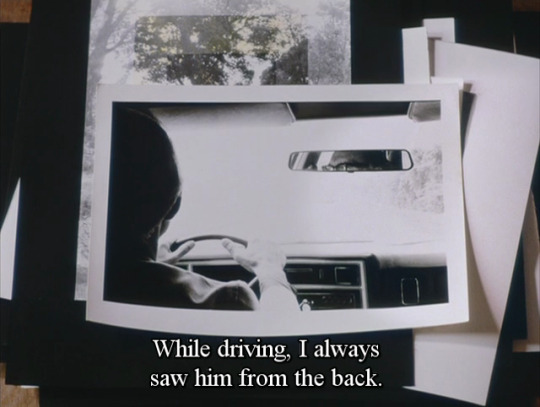

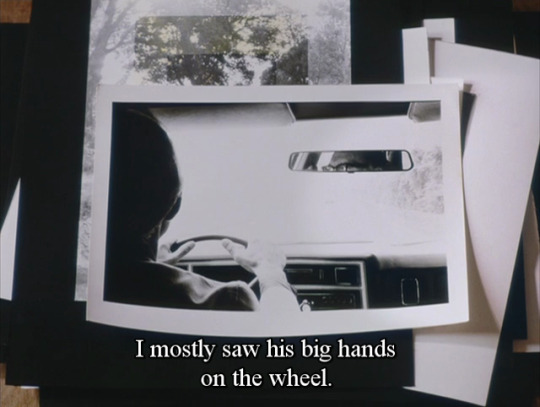

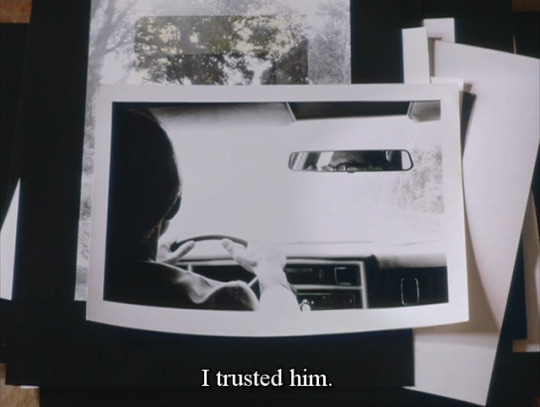

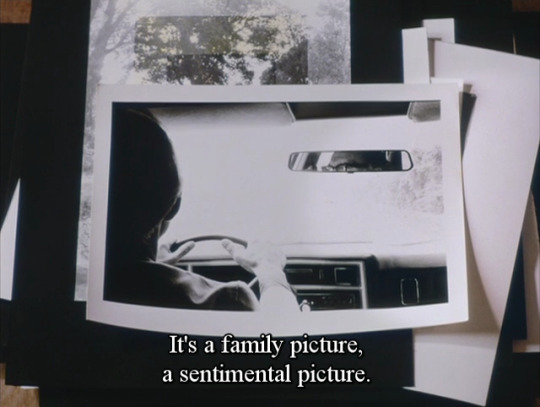

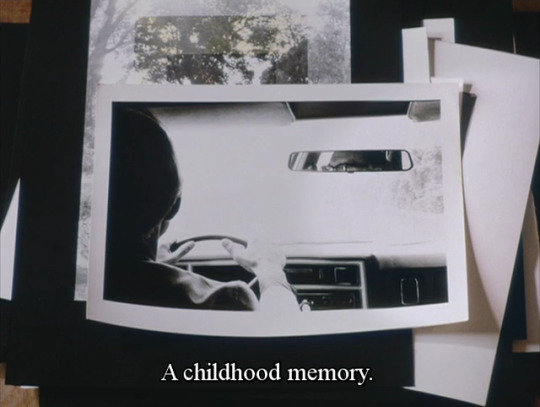

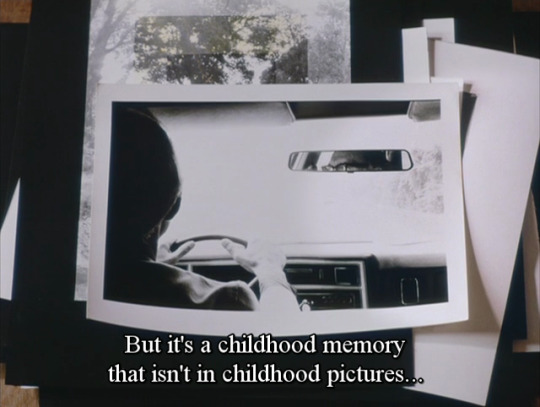

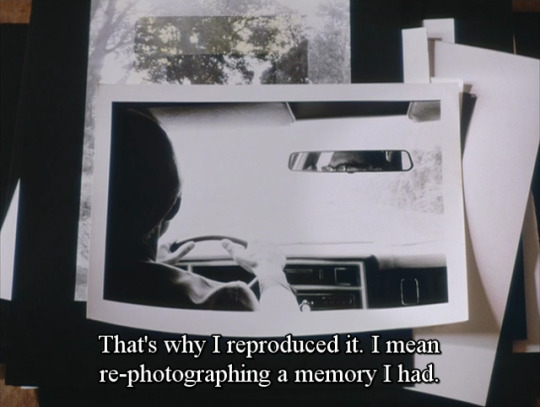

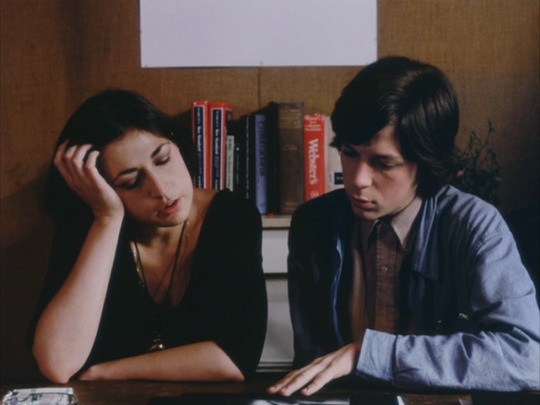

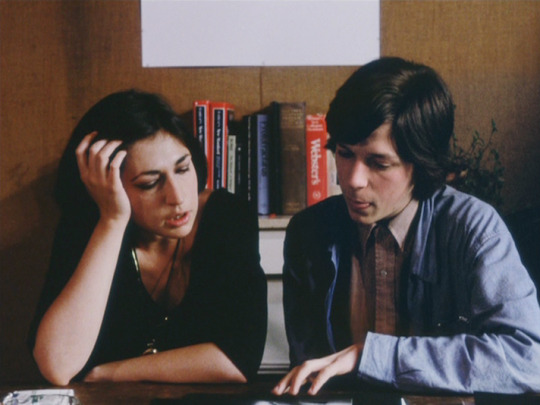

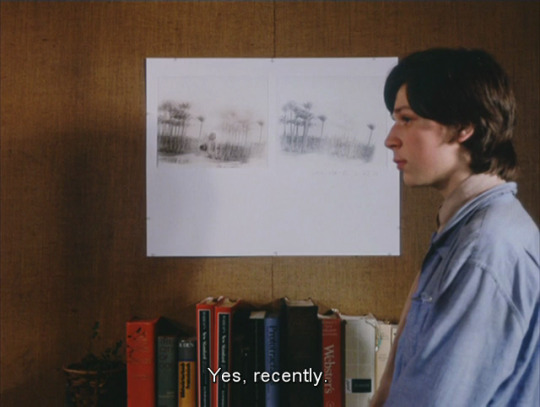

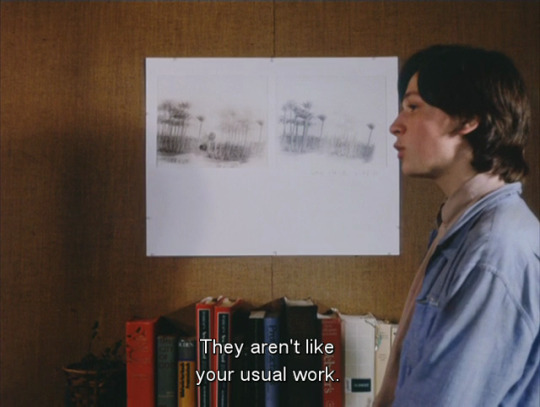

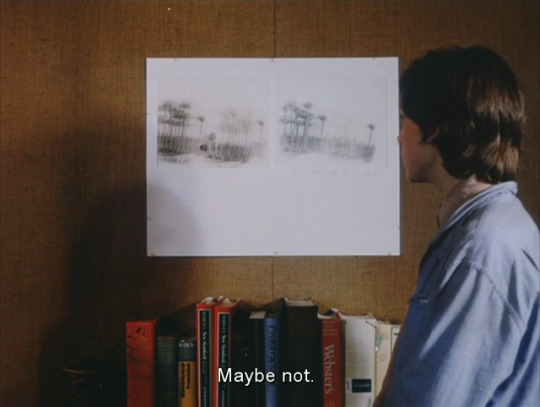

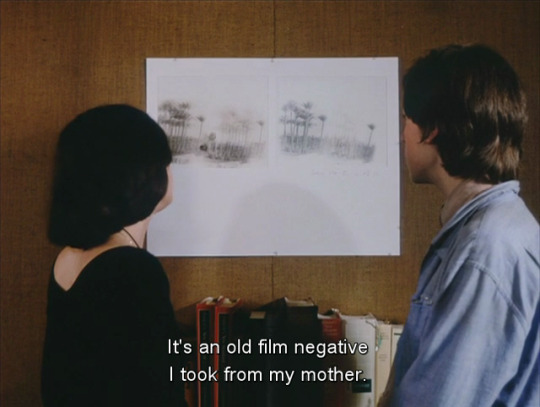

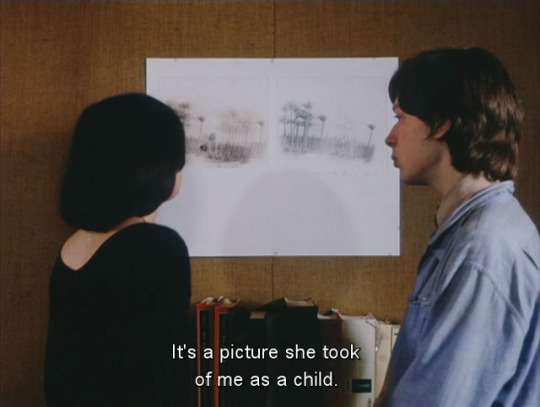

Les Photos d'Alix (Jean Eustache, 1980)

#Les Photos d'Alix#Jean Eustache#Eustache#Alix’s Pictures#quote#photography#cars#memory#childhood#art#artis#black and white#hands#father#family#1980#short film#feelings

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Les photos d’Alix (Jean Eustache, 1980)

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

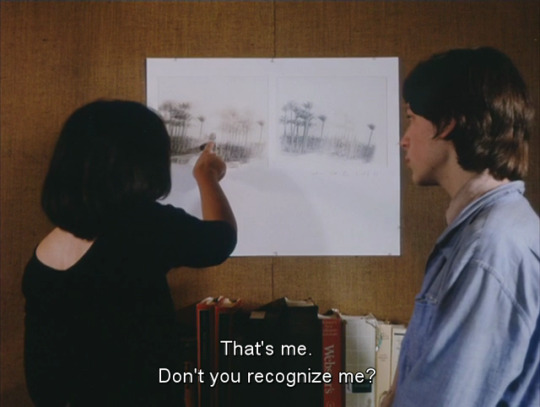

Les Photos d’Alix / Une photographe mentionne ses pinceaux lumineux.

#Cinéma#Les Photos d'Alix#Jean Eustache#Caroline Champetier#Robert Alazraki#1981#Alix Clio-Roubaud#Boris Eustache

0 notes

Text

Chroniques des Invisibles - 2.3 - Alix

Dans sa chambre d'hotel, Méline tournait en rond, fixant alternativement l'horloge et son téléphone. Il était bientôt dix heures. Pas de nouvelles des fêtards depuis le texto de Lulu. D'aucun d'entre eux. Elle avait appelé des dizaines de fois, sans la moindre réponse. Elle craignait autant une intervention du groupe qu'un accident.

- Mel?

Elle sursaute quand on frappe à sa porte. La voix d'Eloïse.

- On a trouvé la voiture. Ils sont sur le parking.

Elle sort de la chambre et se précipite sur place, suivie par le groupe. Les filles restent en arrière, de quelques pas. Elles se méfient de la réaction de Méline. Celle-ci ouvre la portière de la voiture qu'ils ont loué. A l'intérieur, Noah dort comme un bébé contre Deborah.

- La belle au bois dormant, on se réveille.

Le jeune homme grogne un instant, avant d'entrouvrir les yeux.

- Mh..? ...Ah, salut Mel.

- Salut? C'est tout ce que tu as à me dire?

Il se frotte les yeux, puis remarque enfin l'attroupement derrière elle.

- Il est dix heure Noah. T'étais sensé me laisser un message en sortant! Je savais même pas si vous alliez bien !

Il sort son téléphone. Vingt appels en absence.

- J'ai un peu forcé sur la bière, j'ai oublié...

- Tu crois que c'est un jeu?!

Il se masse le crâne, les paupières pressées pour se concentrer.

- T'énerves pas. Tu me fais mal à la tête...

- Si seulement ça pouvait te faire rentrer du plomb dans le crâne...

C'était sorti sans qu'elle s'en rende compte. Noah s'assombrit.

- On est revenu entiers. La prochaine fois, viens avec nous. ça te ferait du bien.

- Ton côté dragueur n'est pas ce qui me fait le plus décompresser.

- Ah!

Il tourne la tête, puis sourit.

- D'ailleurs, je t'ai ramené un cadeau!

Elle esquisse un sourire. Le soulagement a pris le dessus. Il est de retour.

- TADAAAAA!!!

Noah sort de la voiture, suivi par le jeune homme qu'il a rencontré hier. Ce dernier a un sourire nerveux sur le visage.

- ...bonjour?

Méline l'observe, les yeux grands ouverts, sourcils levés. Elle tourne la tête vers Noah.

- ...qui c'est?

Noah passe son bras sur les épaules d'Alix.

- Un ami! Je l'ai rencontré en boîte hier. On a passé la soirée à discuter. Je suis sûr que tu vas le trouver génial!

- C'est-à-dire?

- Y'a pas assez de mecs dans le groupe. Alors voilà Alex, qui va nous accompagner dans le road-trip !

- Je t'avais dit...

- C'est pas une fille. Et puis, ça va faire du bien d'avoir du sang frais! Et au moins, tu pourras essayer de discuter avec. Hein les filles?

Il cherche un soutien de la part des filles en retrait. Elles acquiescent, de façon plus ou moins bruyante. Elles n'avancent pas pour autant. Méline leur jette un regard, avant de revenir vers Noah.

- Je te l'ai déjà dit. J'ai pas le temps. Tu fais n'importe quoi. Faut quelqu'un pour veiller sur toi.

- J'ai plus cinq ans Mel. En plus, Alex te trouve super mignonne!

- ...c'est Alix.

- Ah, oui, désolé.

Méline s'approche un peu plus.

- Mignonne? En me voyant maintenant, et dans cet état?

- Je lui ai montré ta photo.

- QUOI?!

Alix a un bref mouvement de recul. Elle lui jette un regard désolé.

- Alix, excusez-nous quelques minutes.

- O...oui, bien...

Elle s'éloigne sans attendre la fin de sa phrase. Noah, lui, soupire avant d'enlever son bras des épaules d'Alix.

- T'en vas pas, hein? Elle est juste de mauvais poil parce qu'elle était inquiète.

- ...ok.

Il fait signe à Lulu de ne pas lâcher Alix des yeux. Il ne veut pas risquer une scène pour rien. Il s'éloigne pour rejoindre sa soeur. Elle lui tourne le dos, les bras croisés. Il sait qu'ils vont se disputer, encore.

- Qu'est-ce que tu veux Mel?

- ....t'es inconscient. Tu lui montres ma photo?! Comment je m'enlève de sa tête maintenant?! ça fait combien de temps?!

- Suffisamment pour que ça soit plus compliqué que tes petits tours habituels. Alors maintenant, tu vas devoir faire avec, même si ça te plait pas.

Cette fois, elle se retourne.

- C'est un type que tu as rencontré en boîte!

- Ana m'a aidé à trouver un candidat valide. Elle ne m'aurait pas laissé le ramener si elle avait eu le moindre doute.

- Ana n'avait pas à t'aider! Je t'ai dit que...

- T'as besoin de te trouver un meilleur hobby que de me gâcher la vie!

Méline s'arrête. Sa colère se mue en rage froide. Noah semble l'avoir vu aussi. Ils ont atteint un point critique. Il faut qu'il coupe court.

- Ecoute, t'es pas en état d'avoir une discussion calme. On va finir par se bouffer le nez encore plus. Je vais faire un tour dans l'hôtel, et toi tu fais descendre la pression.

Méline se mord les lèvres. Elle se mord la langue, réprimant ses pensées assassines, avant d'hocher la tête.

- J'ai compris.

Elle s'éloigne, sans laisser à Noah le temps de continuer. Elle ne voit pas son air coupable. Il ne voulait pas être aussi acerbe. Elle part s'installer à la petite terrasse de l���hôtel. En hors-saison, c'est assez calme. Elle se laisse tomber sur la chaise, la tête en arrière. Elle n'aurait pas cru la pique de son frère aussi assassine. Quelques minutes plus tard, un bruit. Elle se rassied normalement, pour voir Alix s'asseoir face à elle, avec un verre d'eau.

- Je ne voulais pas vous déranger. ...je ne savais pas ce que vous aimiez, alors dans le doute, je me suis dit que c'était un bon compromis.

Elle remet quelques mèches en place, puis force un sourire.

- Merci.

Elle fini par le regarder. Lui l'observe, sans pour autant qu'elle se sente mal à l'aise. Pas plus que lui, en tout cas. Elle saisit le verre et prend une gorgée, pour s'éclaircir la voix.

- La photo était fidèle à ce que vous voyez?

Soudain, il a l'air mal à l'aise. Comme s'il venait d'être pris en faute.

- Pardon. Je...en fait, je me demandais pourquoi il voulait à ce point nous présenter. Pour être tout à fait sincère, sa façon de m'aborder hier m'a un peu fait peur...

- C'est Noah. Il est comme ça. Et vous l'avez entendu. Je suis toujours sur son dos. Il veut que j'ai autre chose à faire.

Elle plonge dans le regard de l'homme.

- Il vous a rencontré en boite hier?

- Oui.

- Et ma photo, il vous l'a montré quand?

- Pas longtemps après. Vers 1h je crois...

- ...chier.

- Quoi?

- Rien. Vous portez des lentilles de contact?

- Ah. Oui, je suis myope. ça pose un soucis?

- Non. Simple curiosité.

Il se gratte la tête, un sourire timide sur le visage.

- C'est un peu bizarre comme question pour une première rencontre...

- Je suis une fille bizarre.

- ...en tout cas, ça m'a changé des filles qui m'abordaient pour le physique.

- Vous êtes du même acabit que Noah? Un dragueur?

- Non. Je pourrais plutôt dire que j'envie sa façon d'agir.

- ...tout le monde dit la même chose. Il est pas méchant vous savez. Il est juste tête en l'air et borné avec moi.

Elle se relève.

- Je ne vais pas me battre avec Noah une nouvelle fois. Tu vas rester avec nous. Je te conseille juste de rester en retrait. Si tu te mets entre mon frère et moi, tu passeras un sale moment.

Il sourit. Le tutoiement soudain est donc signe qu'elle l'accepte.

- C'est marrant, il m'a dit la même chose.

Elle s'arrête un instant, et esquisse un sourire.

- Ne t'en fais pas, on passe pas une semaine sans se prendre la tête. Tous les gens qui voyagent avec nous en ont fait les frais.

Elle se rapproche du car. Anastasia est partie ramener la voiture de location. Ludivine l'observe, inquiète.

- T'en fais pas. C'est comme d'habitude.

- Il a été un peu dur...

- J'ai déjà fait pire. Toi, tu l'aimes bien?

- Il a l'air gentil. Et il aime pas l'alcool.

Elle frotte les cheveux de Lulu.

- Merci.

Quelques minutes plus tard, elle retrouve le groupe de filles qui discute.

- Deb, faut qu'on parle.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

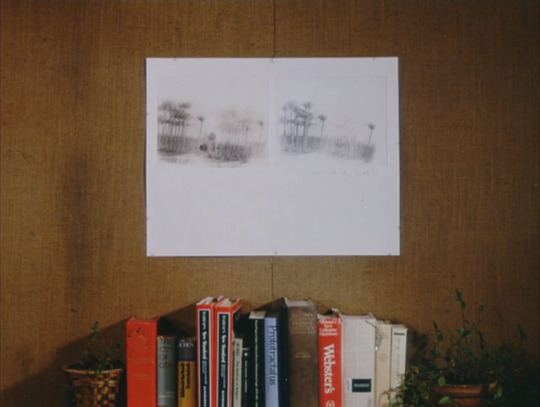

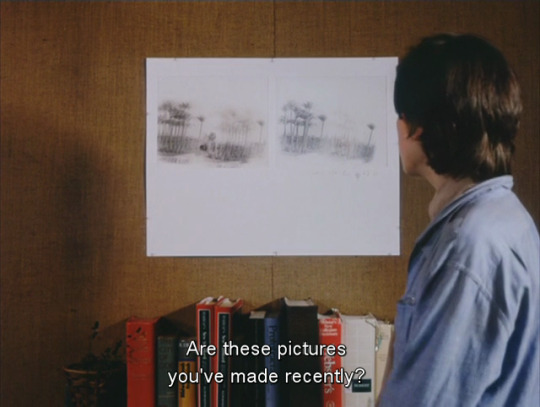

“Les Photos d'Alix“ (1980) by Jean Eustache.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

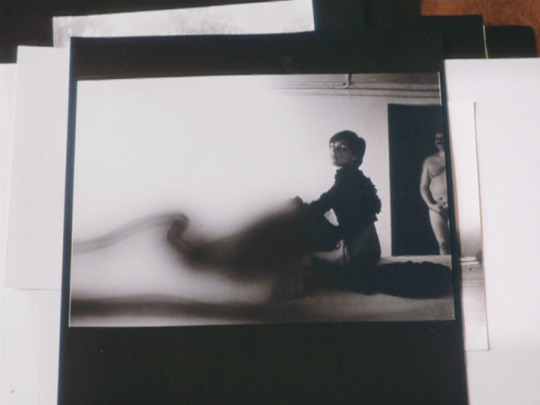

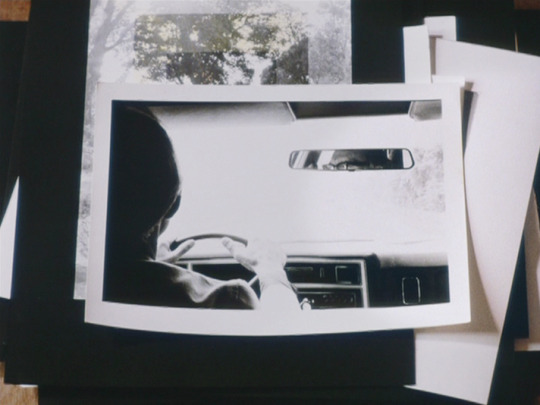

« La leçon d’Une sale histoire croise celle des Photos d’Alix : pour entendre, pour prendre son pied à entendre, il faut qu’une image manque, se présente dans toute sa dimension irreprésentable (c’est Une sale histoire), mais pour regarder une image de près, il faut qu’on la prive de commentaire. Le manque est comme le souvenir, il creuse un trou dans la toile de cinéma. »

Philippe Azoury, « Jean Eustache, Une balle à la place du cœur », Les Inrockuptibles n°576, le 12 décembre 2006, p. 31.

« Les photos d’Alix opèrent une véritable mise en crise de la croyance et d’une déstabilisation du spectateur qui se voit refuser sa part de certitude. Crise qui n’est que la part immergée d’une autre plus grave : que peut encore le cinéma ? que peut-il dire du monde s’il n’est jamais sûr de filmer le réel ? que filme t-il en filmant la parole, c’est-à-dire ce qui est sans image ? Doute radical, et radicalement assumé. Les photos d’Alix est ce genre d’expérience-limite comme il en exista quelques autre à la même époque qui tente, en niant le cinéma, d’en dire la nature. »

Stéphane Bouquet, « Le doute surexposé », Cahiers du cinéma « Spécial Jean Eustache » supplément au n°523, avril 1998, p.16.

0 notes

Photo

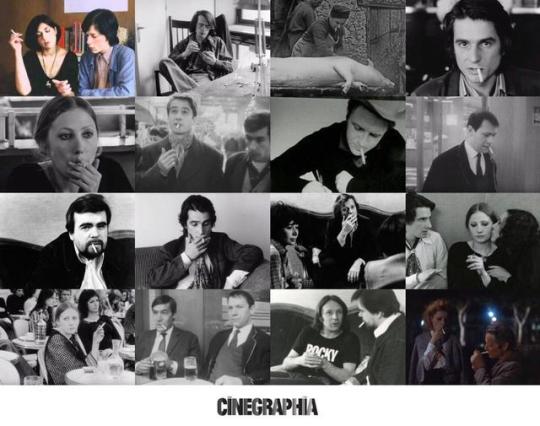

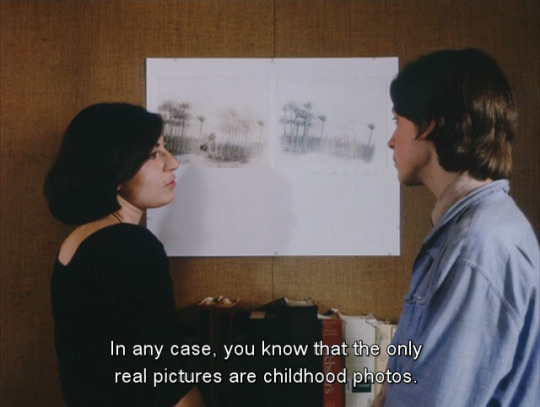

Jean Eustache’s cigarettes

Los cigarros de Jean Eustache

Films

‘Les photos d'Alix’ (1980)

‘La rosière de Pessac’ (1979)

‘Une sale histoire’ (1977)

‘Mes Petites Amoureuses’ (1974)

‘La maman et la putain’ (1973)

‘Numéro zéro’ (1971)

Le cochon (1970)

‘La rosière de Pessac’ (1969)

‘Le père Noël a les yeux bleus’ (1966)

‘Les mauvaises fréquentations’ (1963)

#jean eustache#la maman et la putain#french#cinema#french cinema#cine#cinematography#jean pierre leaud#actor#acting#film#cinephile#cigarette#cigarro#autor#auteur#movies#movie#cinefilo#peliculas#pelicula#mes petites amoureuses#pessac#noel#fotogram#cinegraphia#fotogramas

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Les Photos d'Alix (Jean Eustache, 1980)

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Les photos d'Alix” (1980)

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something Really New: Starting Over

Il faut recommencer de zéro.

- J.-L. Godard (around 1966)

In order to be clear, let me tell you three seemingly unconnected stories.

In 1983, my phone rang. A young man I had never heard of named José Luis Guerín, who was then, it turned out, aged 23, and who lived in Barcelona, was to have some sort of preview of his first feature film in Madrid, and wanted me to present it. I told him I had to see it and like it enough. Which I did (both) some days later. Once I had agreed to present it, I asked him why he had thought about me. He replied that he had read and liked some of my reviews, especially one, about 9 years before, on Bresson's Lancelot du Lac. I was doubly intrigued, because very few people (and he was only 14 at the time) had liked that particular Bresson movie, and I had detected some Bressonian attitudes in his film, Los motivos de Berta. Thus began one of our usually spaced but very long conversations, which make him always late at some appointment (I feel guilty that he once kept Marcel Hanoun waiting for a very long time). It was already then quite unusual for such a young man to talk about Flaherty, Griffith and Dovzhenko as his contemporaries, just like Godard, Eustache or Garrel, not that even the latter trio were very popular or even widely known among Spanish cinéphiles or filmmakers in the early '80s.

Guerín was, no doubt about it, one of a kind. And he not only kept but steadily surpassed the promise of his first feature. He made, in Ireland, Innisfree (1990), in English and Gaelic, about the memories left around Cong, County Mayo, by the shooting of John Ford's The Quiet Man (1952); in 1996, he shot Tren de sombras (Le Spectre de Le Thuit), practically with no dialogue, in France, which was a fascinating inquest starting from a "found footage" home movie (actually shot by Guerín); in 2000, he filmed at long last his native city of Barcelona, in the copiously awarded (including the National Cinema Award) and very personal documentary En construcción, which made of him a relatively known figure. I seem to have been the first to watch each of his movies, although I must state (since people wonder when they see your name in the acknowledgements section of the end credits) that I merely encouraged him or supported his stand against producers or other people who wanted him to shorten his pictures, a step which would have impoverished them and damaged their precious rhythm. Since En construcción, he has continued lecturing and teaching, spurring youngsters to make unconventional movies, and has been busy preparing a new film.

In a medium-sized cinema like the Spanish one, which is not really an industry but rather a mixture of small business and individual craftsmanship (not always on good terms with each other), the only truly original, ambitious, and interesting films are made by a shrinking group of independent filmmakers, devoted enough to suffer long periods of forced unemployment, frustration, and even poverty. They still believe film could be an art, and try to do something about it. The reluctant "father figure" or model of most of the younger promising filmmakers is, of course, Víctor Erice, and they incur the risk of doing almost as few pictures as he. There are better and worse seasons in such a fragile cinema as ours, depending on how many of these filmmakers succeed in making something (even a short), but 2005 has yielded, for me, a very poor harvest, despite the official, corporate, or complacent opinions voiced by most critics and filmmakers and the depressing box-office success of some of the worst. And, fittingly, the best film of the year does not exist.

Of course, it does, since I've seen it eleven times, in three different versions so far. But it has no official or administrative existence: the Ministry of Culture does not know about it, has not "reviewed" or "registered" it, and therefore, it will not appear in the catalogue of Spanish Cinema: 2005. It has never been publicly shown. At my insistence, Guerín has screened it privately to only a handful of friends, and has so far refused to allow anybody from festivals to see it. All that on the dubious ground that it is not really a film, but merely a sort of photographic blueprint for a future feature, purportedly to be shot on 35mm film stock (instead of with a small, low-definition digital-video camera and partly at least with a digital still camera), in color (the "prototype" is in black and white, since Guerín completely de-saturated it), with dialogue, noises, and music (instead of being absolutely silent, which I feel is how it should stay), without intertitles (whereas it is a film to be read, and it is a vital part of its experience to see the words appearing on the screen, as in some of Godard's later films), and with full normal movement (actually, it looks almost like a feature-length La Jetée, since most of the images are stills; there are only, occasionally, some slight, brief, rather tentative movements, a bit like in some Godard films starting with Sauve qui peut [La vie]).

But it is not at all true, as its author pretends, that this film is a blueprint, or a collection of random notes taken in order to prepare a film, or a preliminary sketch of a film to be made — which, I feel, would be wholly redundant, since Guerín has already made it, and very successfully, in a more innovative and cheaper way. Far from being a pre-production "scale model," it is a minutely edited, carefully structured and rhythmed marriage of narrative and reflection, of recollections and speculation, full of mystery and with an acute sense of unceasing, perhaps endless search, which often makes one think of Hitchcock's Vertigo only to remind you, a moment later, of Jonas Mekas's Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania, or suggest a longer, more complex development of Eustache's late short Les Photos d'Alix. I throw out all these references not in order to boost the film, but to help readers to grasp the very particular nature of a film they are unable to see, and perhaps will never have the chance of getting a glimpse of. And it is something so unique that I find it very difficult to describe.

By the way, it is provisionally titled Unas fotos... En la ciudad de Sylvia... y otras ciudades. Which could be translated as Some Photographs... In the City of Sylvia... and Other Cities. Or perhaps as Some Stills... In Sylvia's City... and Other Cities, or maybe Some Snapshots... In Sylvia's City... and Other Cities. In any case, the title is what I like least about it. It is self-derogatory (although partial, like everything in the world, the film is far from being merely "some photos") and utterly misleading as a description. Its present title does not even suggest the narrative drive that makes the film move (in every sense of the word), even though its images are mostly still and its pacing quite deliberate. It should be called, for example (to change it as little as possible), In Search of Sylvia through Her City... and Other Cities. Even if Guerín wants to conceal how personal and subjective a film it is (I wonder how, and even why? He's shy, of course, but...) and would rather pretend that Unas fotos has nothing to do with an intimate journal.

However, what is really meaningful is the personal starting point of what finally becomes a very peculiar kind of speculative fiction, which made me think of a daylight version of André Breton's Nadja, a book that, surprisingly, the filmmaker has not read. In 1980, in the city of Strasbourg, Guerín (or the unseen, nameless narrator who addresses us silently, in brief written phrases) met a girl named Sylvia, who spoke a little Spanish because she had studied nursery in Salamanca. He either never knew or forgot her family name. The only "mementoes" of their meeting are a box of matches from the café "Les Aviateurs," where they met and talked, and a beer mat with some annotations on it: the address of a local old bookstore that, twenty years later, when Guerín tried to find her, wasn't there anymore.

Considering her profession, Guerín takes a city map and locates the places where she could be: hospitals and clinics, the Faculty of Medicine and such. He roams around these places with watchful, hopeful anticipation. Looking at every girl on foot or bicycle, standing in wait for a date or a green light at a pedestrian passage, sitting in a café or a restaurant. Seemingly without realizing at first that, since twenty years have passed when the search starts, any young girl resembling Sylvia would more likely be her daughter. Looking at women, finally of all ages, without finding Sylvia, he becomes interested, intrigued or attracted by several others, many of them utterly different from Sylvia, and even follows some through the streets of the city, while recalling the love of Goethe for Charlotte (or Lotte), who was also from Strasbourg and who felt jealous when the character in "Werther," who so closely resembled her, happened to have eyes of a different color from hers.

I will not disclose more about Unas fotos, because part of the excitement it produces comes from the surprising connections and associations that Guerín spins. It would lose its almost Hitchcockian suspense, its Bressonian drôle de chemin where "the wind blows where it wills," the sense of strolling through different European cities — what the French call flâneries — which account for a large part of its most peculiar charm. It is enough to suggest that it is a truly European film in its spirit and its cultural references — Petrarca and Laura, Dante and Beatrice crossing paths in the past of cities visited once and again, and making the narrator wonder where exactly, and from what point of view, the poets first saw the women they would become obsessed with — typically a filmmaker's concern.

Only on one point can I understand Guerín's reluctance to show his new film: it is perhaps a new kind of movie, probably too far apart from the commonplace, and the times are not too open to experiences like this. As a matter of fact, I have difficulty in imagining a time when such a film as Unas fotos would be normally shown at your nearest theater, no matter where you live (even in Paris). It is perhaps too intimate an experience for people you don't know to be sitting around you. And the total, hard silence I find so necessary to look at it properly, without the rhythms of any music interfering with those of the film, without sound or dialogue or music announcing, underlining, stressing, or "poeticizing" any part of it, probably would be as dangerous in an almost empty theater as in a crowded house. Most people react quite aggressively towards prolonged silence, they would think the sound was not properly working and start yelling and guffawing, only to realize, aghast and angry, that the film is really, wholly silent. Which would cause a self-defensive reaction against a film that commanded so much attention and concentration on its images as to give no rest, no truce, no clue, no hope of distraction from the screen. Maybe a new kind of cinema calls for a new way of communication with the audience, which could be not a crowd, but individuals or small groups of friends sitting before a TV set, in the intimacy of their own homes. Perhaps it would have to be distributed on DVD or bought online.

On the other hand, I find that Guerín's new film should be seen everywhere, because it provides an exhilarating demonstration of freedom. It proves that, thanks to new, ultra-cheap technology, you can make a great, daring, personal film without money, on your own, with only (of course) a lot of talent, effort, and time, and I find that this could be extremely encouraging to aspiring filmmakers who almost despair at the difficulty of getting started, of convincing producers, and even — the film once made — of getting a fair release. Since the film really does exist, it should be seen. After all, what are films for whose goal is not merely making money? For seeing and for helping others to see.

Guerín has been collecting images for this project during almost four years, and building it up and reshaping and refining it incessantly. For that he needs no money, no funding, no producers. His main investment is his own time. Time to travel and walk, to read and think, to choose angles and frames, to look around and to edit his recollections, the traces of his search. Modern technology allows that for almost no money at all. But DV may be used — it is often — too recklessly; it is too easy. And for a true filmmaker, it should pose some questions. With digital video you can shoot as much as you want, and make very long uninterrupted takes, rather than carefully thought shots; the cameras are so small you may become easily a Peeping Tom or a voyeur, and so light you can hold them in your hand, forget about tripods and move it around all the time, with no apparent need to care about continuity or even about properly framing and composing. As a matter of fact, digital technology has no photograms, no frames, no 24-frames per second speed, no Maltese Cross, no persistence of vision, no projection, almost no shots to cut and link; that is, almost nothing of what has defined cinema for about a century. Even editing is a different issue: digital video encourages a new, quite passive conception of "montage." I'm sure Guerín has read at least some of Serge Daney's disquieting writings about freeze-frame, about stills, about the variable nature of images. I gather he's given these issues some deep thought, and I believe he has, perhaps unconsciously, found a way of avoiding the temptations and facilities and dangers of digital video filmmaking.

His instinct has made him start at the very beginning. With the new, cheap, almost cost-free equipment, and taking as his model not D.W. Griffith or Louis Feuillade, or even Louis Lumière, but rather the very earliest of pioneers, Étienne Marey and Edweard Muybridge, he has found again the true essence of cinema, its forgotten, invisible, taken-for-granted secret: that there are in fact no real images of movement, but only stills, a succession of photographs whose succession creates the illusion of movement. Between each, there is always at least a diminutive, almost unperceivable ellipse, the black blank piece of film between each frame. Godard was hinting at this very problem, I think, when he began employing videotape and started stopping the movement of images, or slowing it down, then accelerating again, so as to render visible the original isolation and the willful, deliberate linking of the frames that allows the passage from one photogram to another, which also explains Bresson's insistently calling what he did cinématographe instead of cinéma: after all, he was writing with the articulate movement of fixed, still images. That's why I consider it some sort of "poetic justice" that Guerín, reinventing cinema with digital means, has returned to the very beginnings, without any sort of sound, not even music or noise, without color, and has employed only the minimal, bare elements, those available when cinema was not yet entertainment, not even a show, but almost a scientific tool intended to look at what you cannot see with the naked eye, and to register it and keep a record, to take notes, to make annotations. But Unas fotos is not merely a remake of the early steps of cinema before Lumière: I don't recall a single silent film that used titles as some sort of inner monologue, as a kind of silent, written equivalent of voice-over commentary, as Guerín does. As the W. B. Yeats poem quoted at the beginning of Guerín's Innisfree announced, "I will rise now, and go...."

Miguel Marías

© FIPRESCI 2006

http://fipresci.hegenauer.co.uk/undercurrent/issue_0106/guerin_marias.htm

0 notes

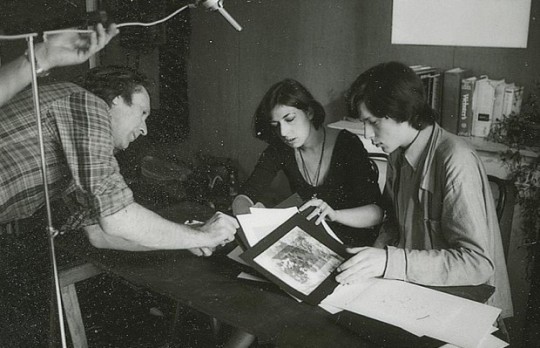

Photo

Les Photos d'Alix (Jean Eustache, 1980)

#Les Photos d'Alix#Jean Eustache#Eustache#Alix’s Pictures#quote#short film#photography#metaphor#art#artist#1980#picture

582 notes

·

View notes

Video

Les photos d'Alix, Jean Eustache France, 1980, 19 min, 35 mm

0 notes

Video

Les Photos d'Alix de Jean Eustache - 1980

0 notes

Text

Chroniques des Invisibles - 2.2 - Bières

- Je vais nous chercher des bières.

Anastasia part chercher les verres. Noah en profite pour observer l'homme, sous une lumière plus claire, pendant le changement d'ambiance. Des cheveux courts, en brosse, une barbe naissante. Il doit avoir dans les 25ans grand max. Des yeux marrons. Anastasia revient, trois grands verres dans les mains.

- Ana?

- ...oui?

- T'es toujours persuadée que c'est son style?

L'homme se braque. Anastasia le voit.

- Physiquement, oui. Après, côté humain...

Elle pose le verre devant lui.

- Désolée. On a pas l'habitude de ménager les gens. Noah est toujours comme ça. Il sait pas faire preuve de diplomatie quand il connait pas les gens.

Elle s'assied à côté de Noah.

- Ah, merci Ana. ...alors, pour faire court...ma sœur est un peu soupe au lait. Elle est très gentille, mais elle ne sait pas s'y prendre avec les gens.

- Pire que vous deux?

Noah a un petit rire.

- ...ouais, on peut dire ça...elle a eu des soucis avec les gens, et elle veut plus se lier à personne. Alors c'est moi qui le fait.

- ...vous avez des façons d'agir bizarres.

- Tu peux dire ça.

Alix regarde Noah, gêné. Ana, elle, tourne la tête vers la piste, pour jeter un œil à Lulu.

- Tu veux voir à quoi elle ressemble?

- Je...J'aimerai bien.

Noah sourit et lui tend son portable. Il voit Alix porter son attention sur la photo. Cherchant des détails.

- Elle est mignonne, hein?

- T'as l'air pressé de la caser.

C'est un reproche. Il l'entend parfaitement.

- Non! ...enfin, c'est que je voudrai qu'elle se trouve quelqu'un. Elle refuse toute rencontre par peur de ne plus être à mes côtés. Alors...si tu t'es chaud pour un road trip avec nous, ça serait super.

Cette fois, il voit Alix s'arrêter. Déborah se rapproche, pour embrasser Noah. Elle recule, en frôlant l'oreille d'Alix.

- T'as plus ton oreillette?

Anastasia jette un regard à Déborah.

- ça? Non, je les ai retiré.

Il montre une oreillette.

- Ce sont mes oreillettes bluetooth.

- Qui met ça en boite? ...t'écoutais quoi?

Il remet rapidement les oreillettes dans sa poche, avant qu'Anastasia n'ait vraiment le temps de les regarder.

- Au cas où j'aurai un coup de fil. Je sais, c'est ridicule, mais j'ai toujours peur de louper un appel.

Elle sourit et s'éloigne.

- Donc...pour être franche, à la base, j'avais dit non à Noah pour ramener une fille. Mais je suis prête à faire une exception pour toi.

- Une fille? Déborah est pas la copine de...

- Noah. Et si. Mais officiellement, ils sont pas "ensemble ensemble". Il a un troupeau de groupies.

- Arrête de les appeler comme ça.

Anastasia lui jette un regard noir.

- Te fous pas de moi Noah. Y'en a qui n'ont aucune autre qualité que leur plastique.

Il soupire.

- Si elles t'entendaient...

- Elles savent ce que je pense d'elles.

Anastasia saisit le téléphone de Noah des mains d'Alix.

- Je te presse, je suis désolée. Je voudrais savoir si tu veux qu'on essaie.

- Je...

Elle plante ses yeux dans ceux d'Alix.

- Je sais que tu pourrais avoir ta place. Je suis sûre que c'est la meilleure chose pour toi. Et que ça pourrait être une bonne chose pour eux.

Elle recule, avec un petit sourire.

- Je dis ça...enfin, je te force pas.

Elle se lève, suivi de Noah. Si ce dernier ne comprend pas la réaction d'Anastasia, Alix, lui, a l'air complètement perdu.

- ...je peux essayer.

Elle sourit et se retourne.

- Dans ce cas...ton premier test, ce sera de nous ramener !

- ...quoi?

- On te guidera. Noah! Fais péter les verres!

Ils passent le reste de la soirée à boire des bières, sauf Alix, qui reste sur les limonades.

- Désolé hein, les tests d'Ana sont...

- J'aime pas spécialement l'alcool de toute façon.

- Ah, au moins elle pourra pas te reprocher ça.

Déborah et Ludivine les rejoignent parfois. Une fois Noah enivré, Déborah prend la relève.

- Tu sais, ce qu'ils disent sur Méline...

- Oui?

- Elle est brute de décoffrage, mais ce n'est pas une mauvaise personne. J'aimerai que tu ne lui causes pas de tort. J'aimerai que tu ne voies pas à quoi je ressemble quand je suis en colère.

- Je saiiiis Deb...

Noah s'avachit un peu plus sur les canapés. Deborah, elle, a un petit sourire doux envers lui.

- Tu vas tellement te faire détruire demain...Mel va être folle de rage.

Elle s'éloigne à nouveau. Alix n'est pas sûr d'avoir compris ce qui vient d'arriver. Cette fille, qui a l'air assez "simple", vient de lui faire une menace avec une voix adorablement douce.

Deux heures plus tard, Déborah et Ludivine se rapprochent. Elles montrent l'heure.

- Ah merde, déjà? ... Alix, tu peux...?

Anastasia lui tend les clés. Il se relève et les saisit Noah, lui, les observe faire.

- ...je vais avoir besoin d'un petit peu d'aide je crois...

Alix l'aide à marcher jusqu'à la voiture, s'assurant qu'il n'a pas envie de vomir. Il rigole, titube. Derrière, les filles marchent de chaque côté d'Ana, qui a l'air malgré tout plus sobre. Elle continue de le regarder.

- Vous pourrez me diriger? Ça va aller ?

- Pas de problème.

Arrivés à la voiture, il installe Noah à l'arrière. Au moment de reculer, Noah l'attrape par le poignet.

- Hep! Tu nous fausses pas compagnie. Demain, tu rencontreras Mel. Mais si tu fais un pas de travers avec elle, je t'éclate.

Il sourit.

- ça me va. Allez, monte dans la voiture.

2 notes

·

View notes