#let's give non-western cinema more attention!

Text

Hey film enthusiasts, especially those who’d like to see more non-western movies! And hello language lovers and those learning kurdish/interested in kurdish, i have very exciting news for all of us! Today (16.04.21) is the start of the global kurdish film festival, all online and - now get this - for free!!! To take part, you only need to create a free account on https://www.globalkurdishfilmfestival.com/ (it took me 10 sec to sign up) and you get access to 106 kurdish movies and documentaries, produces by kurdish directors, ranging from 1959 to 2021 and categorized into themes. I’m very excited and hope that other people appreciate this opportunity as much as i do!

#would appreciate it a lot if you could boost this maybe :)#let's give non-western cinema more attention!#i'm like agfgdfdaafdhgfad SO excited omg. they have films i've been meaning to watch#they have old classics by the legendary kurdish director yilmaz güney! and newer releases by talented kurdish directors#i wish i could watch all of them until th 28th when the festival ends :( but i'll make sure to watch as many as possible!!#kurdish#kurd#kurdi#cinema#kurdish cinema#langblr#languages

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Why is this Ongoing American “Revolution” Bound to Fail?

Observed from outer space, the United States is in a revolutionary turmoil. Fires are burning, thousands of people are confronting police and other security forces. There are barricades, banners, posters, and there is rage.

Rage is well justified. Grievances run deep, through the veins of a confused and socially insecure population, in both cities and the countryside. Minorities feel and actually are oppressed. Indeed they have been disgracefully oppressed, since the birth of the country, over two centuries ago (see my latest report carried by this magazine).

There are some correct words uttered and written; many appropriate sentiments are expressed.

And yet, and yet… It looks like a revolution, it feels like a revolution, but it is not a revolution. It definitely is not! Why?

***

An expert on Communist China, a man who spent many years living and writing books about the most populous country on Earth, Jeff Brown, recently voiced something that immediately caught my attention. He described, accurately, on his China Rising Radio Sinoland, what has been taking place in his native country, United States:

“Protests in the USA, land of Marlboro Man will come to nothing because there is no solidarity, no vision, nor guiding ideology to unite the people in the common struggle against the 1%. Just ask the Black Panthers and Mao Zedong.”

This is precisely when ‘guiding ideology’ is desperately needed! But it is nowhere to be found.

For years and decades, the US (and European) elites and their mass media, as well as their educational plus ‘entertainment’ outlets, have been systematically de-politicizing the brains of their citizens. Pornography, consumerism, and sitcoms instead of deep, philosophical books and films. Massive – often booze and sex-oriented – travel, instead of roaming the world in search of knowledge, answers, while building bridges between different cultures (even between those of victims and victimizers).

Results are increasingly evident.

Citizens in the Western countries were told that the ideologies, particularly the left ones, became “something that belongs to the past,” “something heavy,” unattractive, and definitely not ‘cool.’ Western masses accepted it easily, without realizing that without the left-wing ideologies, there can be no change, no revolution, and no organized opposition to the regime, which has been plundering the world for several hundreds of years.

They were told that Democrats are representing left-wing, and Republicans, right-wing. Deep inside, many felt it is rubbish. There is only one right-wing political party in the US – Democrat-Republican one. But it was better for the great majority just to ignore its own instincts and swim with the flow.

***

It went so far that most of the people in North America and Europe reached the point when they were not even able to commit themselves to almost anything, anymore, from the Communist movements to marriages and relationships. I recently described this occurrence in my book “Revolutionary Optimism, Western Nihilism.”

There are many explanations for this. One of them: regime created society built on extreme individualism, selfishness, and shallow perception of the world. To organize, to commit, actually requires at least some discipline, effort, and definitely great dedicated effort to learn (about the world, a person, or a movement) and to work hard for a better world. It is not easy to become a revolutionary when one is positioned on a couch, or a gym, or while banging for hours every day into a smartphone.

The results are sad. Anarchism, consisting of countless fragmented approaches, is increasingly popular, but it will definitely not change the country.

When leaders of the ‘revolutionary commune’ in Seattle were approached by sympathetic journalists and asked about their goals, they could not answer. These were, undoubtfully, people with good intentions, outraged by racism, and by the killing of innocent people. But do they have plans, strategy, an organization to overthrow the system which is literally choking billions of lives on all continents? Definitely not!

On June 11, 2020, RT filed a report about the situation in Seattle:

“A few different organizations have different demands, and no one speaks for everyone, but everyone’s trying to get together,” Simone clarified, implying that the much-discussed list of “demands” that have circulated for the past few days don’t represent the wishes of the entire community. However, there are a few lines of commonality running through the settlement.

“Everyone’s upset. We all came here in unity, just over the fact that cops need accountability,” he said, declaring that his decision to join the demonstration was about “trying to send a message and get accountability held.”

“Now we’re here – let’s get the dialogue going,” Simone continued, unwilling to commit to taking over other precincts, expanding the Zone, or any of the ambitious demands made by others in the group.”

***

Russian Bolsheviks had it clear, and the same could be said about their followers. Before the 1917 Great October Socialist Revolution, they spent years and decades educating people all over their vast country. Some of the greatest thinkers and writers, including novelist Maxim Gorky and poet Vladimir Mayakovski, were participating in the “project.” Even simple peasants were easily grasping the reality of their dismal existence while getting inspired by some of the greatest minds of their nation. If not for the Cold War and West’s brutal interference, the Soviet Union would survive and thrive until this day.

The same could be said about the great revolutionary struggles of China, Vietnam, Laos, Cuba, Venezuela, where hundreds of millions of tremendous works of philosophy, fiction and poetry have been distributed, for free, to both peasants and workers, who easily understood and got inspired by them. In China, in the 1930s, the entire so-called “Shanghai School of Cinema” was born, a true socialist-realism movement that helped to educate the Chinese public about the state in which it was forced to exist.

Big and successful revolutions were constructed and then supported by the educated urban and rural poor, who were awaken and consequently outraged by their position in the society.

***

The rebellion in the United States is strategically shallow. There are no great leaders, no cultural figures leading it, no extraordinary educators.

Without any doubt, there are clear reasons for rage and resistance. Racism is one tremendous one.

And, there are other ones: US society, in general, is tired as it is depressed. As it is confused. The country is robbing, literally looting the entire Planet. It tortures people in various countries. Rainforests are burning in Indonesia, Brazil, and Congo to satisfy demands for more palm oil and other raw materials. US citizens are consuming as no other nation under the sun does. They entertain themselves, often living frivolous, empty lives. And yet, almost no one seems to be happy there; no one satisfied.

People know something went essentially wrong, but they are not sure precisely what it is. Or, who should really be blamed?

There is an acute lack of solidarity. And everything is happening impromptu.

Are the ‘members of the majority’ in the US truly kneeling because they are in unison with the oppressed minorities and the brutalized non-Western world? Or are they “trying to save their own skin,” and at the end, keep the status quo intact, as has happened in Australia and their basically insincere “We Are Sorry!” 2008 movement?

There’s no strong “front,” there is no revolutionary program.

It appears that the country is not ready, not prepared, for a huge job of re-defining itself.

Insecurity is due to the lack of free medical care, education, and subsidized housing. Most of the people are in debt. Depression is, at least partially, due to overconsumption of intellectual and emotional junk. There is plenty of fundamentalist religions, but almost no discussion about how to improve life in this world.

Segregated, atomized, and otherwise, fragmented society seems to be unable to give birth to a truly compassionate, egalitarian national project.

Many US citizens see themselves as “victims.” Ethnic minorities definitely are. Are the others, too? Who is the victim, and who is the perpetrator? On which side of the scales sits a regular middle-class family, compliant and, by global comparison, heavily indulged in overconsumption? So far, there is no open discussion on this topic. In fact, it is being avoided by all means.

There seems to be at least some consensus that 1% of the richest is to blame, as well as the entire corporate and political system, and also banks. But what about the majority; those individuals who keep voting the system, those who are making sure to ignore imperialism, racism, inequality?

Many questions should be asked, particularly now, but they are not. The very uncomfortable questions they are.

But without asking them, without searching for honest answers, there is no way forward, and no true revolution possible.

The neo-liberal system created entire nations that cannot think independently and creatively. US is definitely one of them. People were bombarded with propaganda slogans that they are free, enjoying liberties. But when the day to act arrived, there has been nothing substantial in terms of new, revolutionary ideas. Just one enormous void. Nothing that could inspire the nation and the world.

The outrage over the brutal police killing propelled millions of people to the streets. The mood has been truly rebellious, revolutionary, geared for big changes.

But then, nothing!

Revolution is being postponed. Postponed for how many years?

The truth is – there are no shortcuts. Those who sincerely want to change the United States will have to follow the revolutionary formula from other countries. The formula is mainly based on education, knowledge, and determined, selfless work for the country and the world, called “internationalism.”

Unless the US comes up with an absolutely new strategy, formula, but right now, frankly, it seems to be extremely far from coming up with it!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

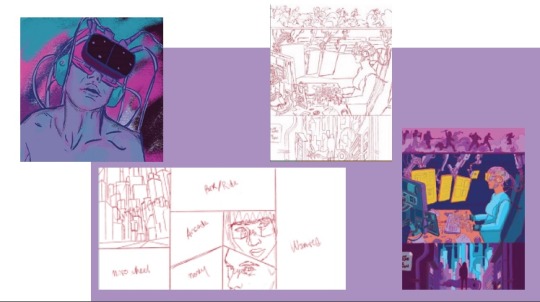

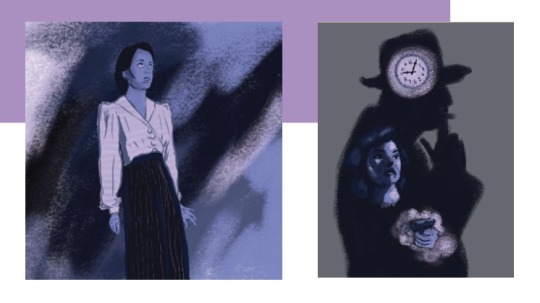

Creative Limitations.

“The media’s already polarizing enough; I guess I’m looking for things that are not polarizing and are much more nuanced about the human condition.” —Lulu Wang, writer and director of The Farewell.

One of the highest-rated films of the year, Lulu Wang’s The Farewell stars Awkwafina as Billi, a fictionalized version of Wang herself, in the story of a family in cahoots to keep their matriarch in the dark. The film is based on “a true lie”: Billi’s paternal grandmother in China, Nai Nai (played by veteran Chinese actress Zhao Shuzhen) has cancer, and the family chooses not to let her know, instead staging an elaborate fake wedding to bring the family together.

Where other independent features often develop out of a short film, Wang took her story to This American Life, a bastion of American radio storytelling. The half-hour audio version, ‘What You Don’t Know’, is what her American film producer heard; from there, the feature film came to life. It’s a quietly powerful story that has resonated with Letterboxd members for many reasons, including the authentic, hands-off way in which it comments on “the many micro-tragedies that naturally follow any family whose members—for one reason [or] another—decide to leave the family nest and search for happiness abroad”. For others, it’s even more personal: “Seeing yourself on screen probably doesn’t get better than this.”

When The Farewell opened in US cinemas in July this year, its per-theater box office average topped that of Avengers: Endgame. The film was still showing in select theaters in October, and has just been released on streaming services, including in 4K on iTunes, with a commentary track by Wang and her director of photography, Anna Franquesa Solano. “We tried to talk a lot about process, so I think that’ll be interesting,” Wang told us. (Also, “we may or may not have been drinking”.)

In time for its streaming release, we chatted with Lulu Wang about aspects of The Farewell’s production, the useful limitations of independent filmmaking, and her favorite films, from holiday movies to best soundtracks. Interview contains plot spoilers.

Lulu Wang and DP Anna Franquesa Solano on the set of ‘The Farewell’. / Photo: Casi Moss

The Farewell is standing strong in our highest rated films of 2019, and the reviews are responding to exactly the things, I imagine, that were important to you: the non-manufactured stakes, the family realness, a sense of the specific being universal, the process of grief beginning long before a person you love dies. How does it feel that your film is being so well received?

Lulu Wang: I fought really hard to tell the story in such a specific way that in some ways I think my biggest fear was that the specificity would put us into a niche, and only attract a very niche audience. So, you know, the fact that there’s so many people—Asian-Americans but also non-Asian Americans—who see themselves and their family in the story is incredible to me.

You often mention the films of Mike Leigh when talking about highly specific stories that nevertheless have a universal resonance. Can you talk about some other such films and filmmakers that do this for you?

Well, Yi-Yi [directed by] Edward Yang is one of my all-time favorites. The specificity, the tenderness of it. The patience of the filmmaking. I find Yi-Yi to be that. Also the humor, there’s so much charm and so much humor in it, it feels just so real.

Kore-eda’s films speak to me in that same way. I just really appreciate the patience in filmmaking. I think so often nowadays the flashiest things get the most attention, and we’ve also trained our brains to need that, right? That kind of stimulation. And so there’s something just so beautiful about a film that takes its time and that doesn’t lean on easy tricks to get attention, but that takes time to get to the heart of something very nuanced, that isn’t so obvious, that isn’t so black and white. The media’s already polarizing enough; I guess I’m looking for things that are not polarizing and are much more nuanced about the human condition.

Through The Farewell’s run, you’ve been generous about opening up the filmmaking process—this Vanity Fair bilingual script breakdown, for example, gives a good insight into how hard you worked on the script. Could you talk us through the ‘wedding portrait sequence’, in which Billi’s cousin and his wife have a series of photographs taken while Billi and Nai Nai carry on a long conversation? It’s entertaining, but it’s also important for what it reveals about Nai Nai and Billi’s relationship, Chinese wedding culture, and the underlying lie of the whole story. You must be so proud of this sequence.

I am. Yeah, I’m really proud of that sequence. The photo portrait was kind of inspired a little bit by Secrets and Lies, when he takes the portrait, and the falseness of what we present when we take portraits like that in the studio, right?

Nai Nai (Zhao Shuzhen) observes yet another wedding portrait set-up in ‘The Farewell’.

One of the intentions, going through it, was minimising the dialogue and trying to condense the script, and so that made me say, “Okay, what are all these moments doing?” They’re all trying to do the same thing, which is to establish the relationship between Billi and Nai Nai, so condensing it into one sequence makes sense. And then also because so much of it is dialogue-driven, how do we make this cinematic? Because at one point the wedding photography studio was separate from these conversations between Billi and Nai Nai, you know, and so this is where, in some ways, being forced to have limitations, being forced to make a shorter film, you start to think more about layering and how do you do multiple things at once.

I really appreciate the limitations of independent filmmaking. Not always; when I’m on set and I get the budget I’m complaining! But looking back on it, those limitations are how we came up with many of our visual ideas. And then also of course it was influenced by the location itself, because we were scouting wedding studios and I wasn’t aware that these studios were so large, that they have, like, different spaces built into the same building. Because if you look at a western photo studio, like in Mike Leigh, right, it’s always the same backdrop.

So that sequence was inspired because we went location scouting, and we were like “this is ridiculous! There are ten different rooms and they all have different set ups!” So then we had this idea of them basically just wandering through the whole photography studio and we’d pick four of our favorite set-ups.

And then this idea of them being silhouetted was inspired by [Woody Allen’s 1979 film] Manhattan. I wanted to capture their relationship as a romance, and I was thinking about Manhattan and their silhouette—I think they were in a planetarium—so we came up with this idea of a continuous conversation, but that was spaced out in front of different backdrops.

Woody Allen and Diane Keaton in a scene from ‘Manhattan’ (1979).

That sequence helps us learn more about who Nai Nai was before the events in The Farewell take place. At Letterboxd, we’re often compiling top ten lists, but “best grandmothers on film” is not a highly populated category, especially films where grandmas are more than just ‘kindly’. Tell us more about fleshing out Nai Nai’s life and the importance of giving respect to older female characters.

I think about that in life, too, you know. We think about a lot of people in our lives as fulfilling a particular role in relation to ourselves. That’s my mother, that’s my grandmother, that’s my teacher. Remember as a kid you don’t even think your teacher goes to the grocery store! They hide in the back of the class and then pop back up in the morning! So as a filmmaker, as a storyteller, I’m always thinking about who they are, separate from the context of their relationship to you.

That’s also part of the sadness of not being with somebody or of losing somebody is you don’t necessarily get to see them in all those different contexts and then when they’re gone, there’s so much you don’t know about them and may never know about them. And as our parents get older, your relationships to your relatives change, you know, like ‘who’s the parent?’—children often have to become the caretaker. That’s where it came from, was wanting to make sure that Nai Nai was not presented as a stereotypical grandmother. That she felt like a three-dimensional woman, a woman who was once a girl, and a young woman, someone who was once in love, or maybe in a relationship out of convenience. And also that she’s not always sweet. That’s very real.

One of the motifs in The Farewell is birds appearing at significant moments. In many cultures, a bird is a portent of something big, for example, a death in the family. Where did your bird come from?

The bird for me came from wanting to put [in] something magical, but not, like, literal, you know? Meaning, I wanted to insinuate spirituality and magic, but I wanted it also to be interactive with the audience, so based on what they believe and how they interpret that bird is the meaning they get out of it, without me saying “this is what it means”. Much of the movie is about belief systems and perspectives, so I think that if you believe the bird means something, then it does. But if you don’t, and you’re a much more literal, scientific person and you go, “Oh it’s just a bird, it’s just a coincidence,” then it doesn’t mean anything.

Awkwafina leans on Zhao Shuzhen’s shoulder during filming. / Photo: Casi Moss

That’s how it is in the movie and that’s how it is in life: what you believe, and where you find meaning, becomes your reality. With Nai Nai outliving her diagnosis, the people who believe the lie is what worked will continue to believe that the lie is what worked, and people who believe that prayer is what worked… In a way, we look for signs to validate the things we believe, because it’s how we get through life! We need signs, we need meaning, even if we’re the ones who are attaching that meaning.

This far down the track, what is your fondest memory of the production period?

Oh gosh, so much of it. I think just being in China, being in spaces that were in my real life, with a crew. Any time that that happened it was really emotional, like shooting in my grandmother’s neighborhood. Shooting at my grandfather’s real grave. I hadn’t seen my grandfather since I left China when I was six, because he died a few years later. To now be at his grave site, gathered there with producers and the crew, scouting it and then shooting there, you know, it was an integration of two different parts of my life that I always felt were really separate, which was my family and China and my background and culture, and then the other part of me, which is being an American, being a filmmaker in America.

In many ways, I always felt that my family didn’t understand what I wanted to do, and also I couldn’t bring who I actually was into Hollywood, there wasn’t a space for that. With this film I was able to fully integrate, bringing my American producers to China for the first time, having my grandmother come to set and see me directing with all the lights and camera and crew. Having my parents be part of the table read. It just felt, really, like I was creating from a place that felt true and real and grounded to me.

Awkwafina and Zhao Shuzhen in a scene from ‘The Farewell’.

Speaking of being grounded, what’s your go-to comfort film? The one you’ll always throw on on a rainy day?

Oh, I know: The Philadelphia Story. I love that story.

What’s the film you’ve probably seen the most?

The Sound of Music.

Favorite song from it?

Probably ‘Edelweiss’, honestly. I’ve been watching that film since I was a kid, it’s one of my parents’ favorite films. It’s such a family film for us, and every time the father sings ‘Edelweiss’ to all the kids, I get really emotional.

What’s the film—or films—that made you want to become a filmmaker

Secretary. The Apartment. Annie Hall. I know that’s taboo, I shouldn’t say that, but I have to. Like, Annie Hall, you know? When I first saw it, I was really inspired by that. And The Piano. I think, with both The Piano and Secretary, it was the exploration of female desire and female voice—and obviously as a trained classical pianist since the age of four, the symbol of the piano for her, for that character, and for me, was really meaningful.

Jane Campion’s ‘The Piano’ (1993).

Alex Weston’s soundtrack for The Farewell, which leans heavily on human voices, is something you worked closely with him on. What’s your all-time favorite film soundtrack?

So many, I don’t know how to choose! Well, I have a couple. In the Mood for Love. And then, because it is related, Barry [Jenkin]’s If Beale Street Could Talk is one of the most astounding soundtracks. Barry was inspired by Wong Kar-wai for Moonlight, and so yeah, thinking about In the Mood for Love reminded me that Nick Britell’s If Beale Street Could Talk soundtrack is just incredible.

Holiday season is fast approaching: what’s your favorite holiday/Christmas film?

Home Alone is a classic that we all watch. Does Fiddler on the Roof count as a Christmas film?! I don’t know. That’s my mom’s favorite. And then I have a really embarrassing one, because when we got sick of Home Alone, we had to pick a new one, and somehow we landed on Jingle All the Way. For years, we watched Jingle All the Way and just laughed our heads off.

Finally, how is Children of the New World coming along?

Very slowly. I’m working on the script. I’m writing it. It’s gonna take a while, probably after all of the press is done so I can fully focus.

‘The Farewell’ is available on streaming services now. Comments have been edited for clarity and length. With thanks to A24.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stalker Film Analysis

“I can make good work based only on three things -- blood, culture, and history”

- Tarkovsky

Bringing the audience into an alternate Russian reality, Andrei Tarkovsky, the “Poet of Apocalypse,” constructs a masterful and existential Sci-Fi world in his 1979 film Stalker (Quandt). At the start of Stalker, through a fictitious government letter, we learn of a realm called the Zone. The letter considers how it came about -- was it a meteorite? Aliens? Nevertheless, when troops were sent, they never returned. To protect the masses, the government secured the area with barbed wire, dense tunnels, and security officers. We learn of this place, then we learn of the Stalker.

A desolate, decrepit apartment. The film is a bold, impossible sepia. We hear nothing but the rumbles and rattles of a train, slowly crescendoing as it approaches the home. In bed is a family: man, wife, and child. On the bedside table rests an apple with two bites missing, tablets of morphine, a syringe in a tin, cotton, and a glass of water. This is the home of the Stalker. Aside from the train, the only noise we can hear is the Stalker getting out of bed. He is preparing for another trip to the Zone--the trade of a Stalker. He readies himself to meet the men whom he will be shepherding through the Zone, so that they may find the Room, the place where one’s deepest desires are fulfilled.

In that striking sepia, we become acquainted with the Writer. A man full of philosophies. In an unknown irony, he laments about the lack of mysticism in the world and the death of excitement. “The world is ruled by cast-iron laws,” he claims, a possible allusion to the Soviet regime which regulates Tarkovsky’s work with resolute vigor. When he speaks, all other ambient sound stops. We are forced to focus on his words, his insights, or lack thereof.

Shortly after, viewers are brought to a bar, which, much like the Stalker’s apartment, is in disrepair. Everything is covered in a layer of dirt, puddles dot the floors from roof leaks, and the minimal lighting flickers. Here we meet the Professor. The audience learns he seeks scientific discovery, as the Writer seeks inspiration. They name their desires, they assume the stakes. But, in this contemplation, we learn a central theme of the film. The Writer says, stumbling over himself in drunkenness, “...but, how is it I can put a name to… What it is I want? How am I to know?” This admission is pivotal to the film’s message, and Tarkovsky is kind enough to give us this hint before the journey into the Zone unfolds.

On brand-new Kodak 5247 stock film, Tarkovsky fills the screen with symmetrical shots, a style ubiquitous throughout the film. He plays with the depth of field by placing mundane objects, such as a wooden beam, in the foreground to pull the viewer’s eye to the background. These shots set the scene, they tell parts of the story without saying a thing.

The three--the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor, all referenced only by their professions, a possible communist allusion--embark on their journey to the Zone. Rumbling through sparse, mud filled streets in an all-terrain vehicle, they venture through abandoned buildings and railways. The City they are leaving is incredibly industrial: tight brick-lined corridors constricting the viewer, smog billowing in every direction, further suffocating you. Not a single vestige of vegetation in sight. The sound of stepping through puddles is as loud as the police officer’s engine they are trying to avoid. Sonically, the film is mastered at a consistent level. These staccato, pointed sounds add tension to the film and control the direction of the viewer’s attention, building with the visuals to the moment when the men finally reach the Zone.

After a series of long takes of the men’s faces, typical of Tarkovsky’s style, they arrive. We are greeted with a moment of silence, and color film, as we see the Zone for the first time. The color shows the full glory of the Zone and juxtaposes it to the sepia City. The Zone is a vast, natural landscape. With trees and grasses overtaking what remnants of civilization are left, abandoned cars sulking in their lonesomeness, and power lines, which have given way to the earth, linger in the front of the frame. A clear ecological statement. The Zone, arguably the central character of the film, slowly reveals itself to the Writer, the Professor, and the audience throughout the second half of the film.

Long takes paired with wide landscape views of the Zone envelope the viewers, taking them along for the journey. The scenes are truly immersive. To compound this emotion, the combination of synthetic and orchestral composition by Eduard Artmyev is subtle, and easier to feel rather than to hear. It hovers over the scene, or sinks beneath it, delicately shaping the mood. In an interview Tarkovsky revealed that “one mustn’t be aware of music, nor natural sounds.” Those natural sounds, such as wheels on rails, are synthetically produced and embedded within Western and Eastern inspired melodies, melting otherworldly tones with earthly ones. The music is sparse but effective.

It is impossible to travel directly to the Room. The Zone, echoing non-entry nuclear zones of Cold War Soviet Russia, demands respect. “The Zone is a very complex maze of traps. All of them death traps,” the Stalker warns his sheep. It is always in flux, and pathways which were once safe become impassable. The Stalker, looking to the heavens, says, “it’s as if we construct it according to our state of mind.” It lets through neither the good, nor the bad, but rather those who are hopeless. The truly desperate souls. In certain places, the land swells like waves, and in others it smokes and smolders. It bends time and space. It challenges the notion that there is no mysticism left in the world, it challenges those “cast-iron laws” that the world is fixed.

However, the Zone, and these men’s journey to the Room, reveal the existential truths we bury in ourselves. “For who knows what desires a person might have?” the Professor sighs. Why is the Room just a rumor? Is it a gift or a message or a curse to mankind? Is it secured by the government, not to protect people from death, but to protect them from what they want? From what their desires may do to society? The Soviet Union, “with its propaganda and party indoctrination sessions – went on beyond an imaginary fence,” building real fences within its citizenries mind (Guardian). The Zone is a space of personal truth, a space the government can’t penetrate, deep within the Russian psyche. Within the Zone, each of the men is granted a monologue where he can exalt his truths and speak candidly without fear. For fear is the Zone, and within it they have nothing more to fear, not even themselves. This is a space where they can discover what is potentially the most elusive of truths: What do I want?

Stalker offers a cross-section of consciousness. The city is these dull, dogmatic “truths” we tell ourselves to get through the day--particularly those true in communist Russia. God isn’t real. Neither are ghosts. Everything is fixed, and tangible if real. Everything has order and, despite the boredom of it, safety. The city is the superficiality of our own existence. The sepia might be beautiful, but is incomplete: it doesn’t reveal the full-depth and complexity of the world, or the self. However, the Zone challenges these preconceived notions, these walls we build within ourselves. Or, that government and society helps construct. For example, the Writer, overcome in a moment of honesty in the Zone, says he writes because he is unsure. He writes to prove his worth to himself and to others. He doesn’t write because he thinks he is a genius, as he earlier dotes, for if he did there would be no reason to write. The Zone forces us to face ourselves, quite literally, by constructing a world based on the minds of those within it. The Stalker mutters, half-asleep, “people don’t like to reveal their innermost thoughts.” The Zone is where those thoughts foment, without restriction, to the front of the mind.

The Stalker tells us in the Zone of his mentor, Porcupine--or as he knew him, the Teacher. He taught the Stalker everything about the Zone: how to travel through it, how to respect it. How to get out of it. Then, one day, Porcupine went into the Room. Shortly after he returned to the City he became very wealthy, wealthy beyond his wildest dreams. Then he hanged himself.

If the Room is the center of the self, the deepest desires of the self, perhaps it is best left inaccessible. Desire is dangerous; its consequences unpredictable. While the death of Porcupine is a critique of humanity’s materialism, and materialism’s inability to truly satiate humanity’s existential needs, I think this film offers a criticism of (selfish) desire more broadly. The Stalker’s desire is not to enter the Room, but to escape his existence. His pleading wife, his daughter crippled by his excursions. Their shabby home. Before the Stalker leaves for the Zone, his wife warns he may find himself back in prison, he replies that “everywhere’s a prison.” He doesn’t need to enter the Room, the Zone is all he desires, it is wild and free, while the City is captivity.

Additionally, Tarkovsky seems to be pointing at the elusive nature of desire. It’s claimed the Room knows your deepest desires, even those you hide from yourself, and then fulfills them. But, as Zizek claims, “our desires are artificial. We have to be taught to desire. Cinema is the ultimate pervert art. It doesn’t give you what you desire, it tells you how to desire.” If we acquire our desires socially, is there any desire which is independent, belonging to the self completely? Can the Room honestly fulfill someone’s deepest desires, if those desires are by nature inauthentic? Is this why Porcupine commits suicide? The ultimate horror is not the desire, it is not the longing: it is the fulfillment of that longing. Perhaps we ultimately fear fulfillment of desire because it is alien, it is a self-deception -- we don't really want it. Thus, true desire seems to move further from our understanding. Maybe it isn’t that desire is best left inaccessible, but that the Room is an illusion, and desire beyond the superficial is still inaccessible.

The dynamic nature of the Zone, their journey which challenges the time-space continuum, is an allegory for the cyclical, impossible, and inexplicable journey to discovering one’s authentic personal desires. And, ultimately, its innate inaccessibility and potential untruth.

This film catalogues, with visual and auditory brilliance, an existential woe of humanity. Stalker is a philosophical text with a three-hour visualizer and sound effects. While Tarkovsky was inspired by the psychological effects of living under the Soviet regime, and the film speaks to that reality, this film is durable regardless of time, politics, or country. Undeniably versatile, it can be enjoyed as a piece of entertainment, a piece of art, and a piece of commentary. If you’re looking to lose yourself, your conscious self, in a film, and find your unconscious self, Tarkovsky’s Stalker will siphon you into that Zone.

https://www.tiff.net/the-review/andrei-tarkovsky-the-poet-of-apocalypse/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1468-5922.12365

Gianvito, John (2006), Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews, University Press of Mississippi, pp. 50–54,

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/nov/06/soviet-union-kitchen-table-russian-revolution-centenary-togetherness

http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2017/the-25-best-mind-bending-movies-of-all-time/2/

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0079944/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

blog 04 - avatar (the one with the blue people not the last airbender)

preface

I went into this with absolutely no feelings about this movie beyond the absurdity of how many sequels it’s apparently going to get. As an artist, I find the visual effects extremely impressive even to this day, but as a storyteller, I thought this story was almost so inoffensive that it’s offensive.

However, I think that engaging with things in good faith is a good way to find ways to expand your horizons and thoughts, and I like to enjoy things despite my dad’s insistence that I like to not enjoy things. (It’s not that I like to not like things, it’s that it’s easier to entertain people when it’s a bad review. Tough crowd.) I’m a firm believer in the idea that cerebral analysis of media adds to the joy of consumption rather than takes away from it, so let’s dive right in.

I like structure, so we’re gonna layer it like a delicious theme cake.

1. the elephant in the room

Everyone has seen Pocohontas. Everyone has seen Dancing With Wolves. I’m not really here to rehash arguments, but I think getting into this movie without addressing what first comes to everyone’s mind when they think about it is pretty much impossible. The “White Savior” trope is more or less a narrative cliche in which a noble white person will take a stand against the Bad White People on the side of a sympathetic oppressed people-- Native Americans see this plotline probably the most, but black people still see it today every now and then (Green Book got nominated for a lot of Oscars, after all. The hunger is there for easily digestible feel-good race relation drama.) Wikipedia sums up the White Savior trope better than I could, so here it is:

“At the cinema, the white savior narrative occupies a psychological niche for most white people, as an expression of their latent desire for interracial goodwill and reconciliation. By presenting stories of racial redemption, involving black people and white people professing to reach across racial barriers, Hollywood is catering to a mostly white audience who believe themselves unfairly victimized by non-white ethnic groups, because they are culturally exhausted with the unfinished national discourse about race and ethnicity in the society of the United States. Hence, films featuring the narrative trope of the white savior have notably similar storylines, which present an ostensibly nobler approach to race relations, but offer psychological refuge and escapism for white Americans seeking to avoid substantive conversations about race, racism, and racial identity. In this way, the narrative trope of the white savior is an important cultural artifact, a device to realize the desire to repair the social and cultural damage wrought by the myths of white supremacy and paternalism, regardless of the inherently racist overtones of the white-savior narrative trope.“

Native Americans factor into this most significantly in the case of Avatar-- aliens in movies are hardly ever just aliens. Whether they represent an oppressed underclass (District 9), childhood innocence (E.T.), or fear of foreign invasion (War of the Worlds), aliens are an easy vessel to carry almost any idea you want them to. So if the Na’vi are more or less an ideological stand-in for Native Americans during the conquest of America, our protagonist Jake is the future space cowboy to the Cowboys and Indians In Space.

Both Jake and Grace sort of fall in and out of the White Savior space-- ultimately Grace condescends to the Na’vi a little more and she has a more complete character arc that ends with her transcending this trope, but Jake is whole hog in it. He’s like, the legendary prophecy warrior. He’s The Guy.

(Pictured above: The Guy)

James Cameron grapples pretty hard with the White Savior trope-- he never truly goes one way or another about it and the concept of Avatars-- as in the Na’vi bodies that Jake and company jump into-- significantly...well, complicates the idea of race relations in this movie. There are certainly some uncomfortable ideas about identity wrapped up in the concept of body swaps (if this idea interests you, Altered Carbon is a really good read), but re: the readings and lectures, the concept kind of works towards what is ultimately the broad takeaway of the movie.

In summary: no, we’re not doing this whole review about White Guilt in Space. Now that that’s out of the way...

2. james cameron predicted late stage capitalism

Imperialism

"The policy of extending the rule or authority of an empire or nation over foreign countries or of acquiring and holding colonies and dependencies."

Avatar is about imperialism. This is as broad and pointed a theme as you can get from a movie that draws such heavy inspiration from Native American and Aboriginal cultures. Interestingly enough, the movie’s futuristic setting goes hand in hand with the commentary about the military and Western Imperialism.

The company in Avatar, and all the almost comedically evil military men, are very brazen about their lack of ideological purpose. They are on Pandora for money. They are being paid to go to Pandora to take its resources-- the delightfully named “Unobtanium” in specific. As mentioned in the reading, Unobtanium is valuable for its properties as a superconductor, and I’m not a STEM kid, so I’ll leave it at that for simplicity’s sake.

That the mercenary force on Pandora is so open about their exploitative intentions draws an interesting parallel to the world of today that’s maybe a touch haunting, considering that Avatar came out some years ago. In politics, at least up until now, you notice the use of a few common euphemisms as smokescreens for more extreme ideas-- for example, the Right’s: “protecting American jobs”.

Protecting American jobs is a euphemism for racism against Mexicans-- it was the most common smokescreen reasoning for the border wall pre-Trumpian politics. Trump and company have since dropped the euphemism all together. The death of a euphemism usually means that the euphemism is no longer culturally or socially required-- you can just come out and say whatever horrible thing you mean. In Avatar’s universe, it’s clear that the political-economic climate has come to a point where they can just say that they’re there to steal the Na’vi’s resources whether they like it or not.

The movie and the lecture both draw specific attention to the parallels the film draws explicitly between military tactics used in the movie, and real-world events. “Shock and Awe”, a tactic coined by the Bush era, is referenced in exact terms-- it being a display of overwhelming force intended to break the fighting spirit of the enemy. The commander character whose name I just read but I can’t remember now says that he is a veteran of both Venezuela and Nigeria-- both real world locations in which the U.S. has invaded and destabilized for material interests under the guise of American ideology.

In Avatar, we see the thin veneer of “freedom and democracy” as the driving forces of U.S. intervention stripped away explicitly. The opening narration of Jake’s arrival to Pandora has him say that “on Earth, these men were soldiers fighting for freedom...but here, they’re mercenaries”, however, the line between a supposed freedom fighter and a mercenary is borderline nonexistent.

3. western scientific objectivism sucks

Another current running through Avatar is the juxtaposition of what is “real” with what is “unreal-- aka Western objectivity science versus belief systems. This is embodied in the character of Grace, a scientist and anthropologist who has been researching Na’vi culture for some time. The reading characterizes her as “the happy face of liberalism” that tries to put a nice coat of paint over the same imperialist ideas that the more blunt military types embody-- she is kinder to the Na’vi and sees their culture and planet as worth preserving, but she is ultimately dismissive of their beliefs and of Eywa (”pagan voodoo”) the same as the other mercenaries.

We’re gonna put on tinfoil hats for a little bit here to make a relation between Western culture (imperialism and colonialism) and capitalism and paganism. Are you ready?

Okay.

So you know how they burned witches at the stake at the onset of the Industrial Age in America and the pagan practices of “hedge magic” were pretty much obliterated? I don’t think that’s a coincidence. Capitalism is a system that can only operate materialistically-- people aren’t “people” but “workers”, and the concept of magic and belief exists in terms that capitalism can’t define, and more importantly, can’t exploit. So witches were burned and women were placed with great reinforcement back into domesticity, where their function in capitalism was to give birth to and rear new workers.

You can see this dichotomy between the science of objectivity (what is “real”) and belief systems (what is “unprovable”, “unobservable”) in the way Grace uses scientific terms to justify the Na’vi’s spirituality. A very powerful through-line can be seen in the way that imperialism, capitalism, materialism, and objective science intersect. Their interconnected natural collective consciousness is like the raw function of a brain to her, likened to a network. It isn’t until Grace is mortally wounded and experiences the Na’vi’s healing ceremony that she is able to transcend the capitalistic, materialistic terms for definition for Eywa to have a spiritual experience, and to become one with Eywa herself (”she’s real.”)

In a plot that hinges on the material (Unobtainium) interests of a capitalist mercenary force, the ultimate refutation of this is the Na’vi’s spiritual values.

4. avatar: endgame

So what is this all working towards? Well, the idea of an interconnected spirituality like Eywa. The idea takes root in geomantic ideas, more commonly known as “feng shui”-- it’s sort of the concept of an earthly energy, a flow that moves through and connects the Earth and its people and creatures. The strange braid cord things that allow the Na’vi to interface with certain points and other creatures is a very straightforward metaphor for that concept of feng shui and geomancy.

Here we come back around to the concept of Jake as the White Savior/chosen one/The Guy. It’s kind of obtuse, but the general theory is that Eywa chose Jake as a sign that all peoples must needs transcend their boundaries and become one with the larger concept that Eywa represents. This of course comes packaged with an urgent environmental message-- our life is that of the planet, and to exploit and sacrifice one is to sacrifice the other.

Pandora, Eywa, and the Na’vi represent the polar opposite of everything that capitalist imperialism is. Thus, James Cameron, ironically, used a huge budget Hollywood endeavor to refute everything that Hollywood is. Now he’s making Alita: Battle Angel.

Funny how that works. Oh, I made myself sad.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rose of Highgarden. On Margaery Tyrell (part 2)

This is the second part in a series of metas about Margaery Tyrell in Game of Thrones (Part 1). In the first part I wrote about Margaery’s narrative arc and her characterization in season 2 - the season where’s she first introduced. In this post I will take a closer look at her costumes in this season.

Costume design is a particular interest of mine and Game of Thrones has some of the most interesting costumes on television - especially when it comes to the female characters. The award-winning costumier Michele Clapton’s work for the show is very original and in several cases visually arresting. However, a lot of fans have complained that the costumes are not medievalist enough. While I do think that this argument has some merit, I personally have no problem with the fact that Clapton’s work isn’t very medievalist. Whilst the feudal society of Westeros is largely inspired by 15th century England, it is also a fantasy world and that means that the costumes don’t necessarily have to be period specific.

Clapton’s decision not to go medievalist is a conscious choice since she has previously worked on period pieces such as the Jane Austen adaptation Sense & Sensibility (2008) and the English Civil War drama The Devil’s Whore (2008), for which she won a BAFTA. Instead, she has chosen to take inspiration from both history and high fashion:

“I look at contemporary fashion and art,” she says. (x)

When it comes to the costumes of Game of Thrones, Clapton have taken a very eclectic approach with inspiration from a number of different sources: historical costume, contemporary couture and vintage fashion. While her costumes may not be “historically correct”, which btw is a bit of an anachronistic concept when it comes to fantasy, her eclectic approach has yielded a number of original and iconic costumes that have prompted a number of articles in various news outlets.

Whilst a number of fans have decried her costumes as ugly, they overlook the fact that in television and cinema, costume design is not just about making pretty clothes - rather it is about supporting and articulating the characterization in relation to the narrative.

Even in real life, clothes is more than just about functionality and aesthetics. It is also a form of communication, which is why there’s an entire discipline dedicated to the communicative aspects of clothing that is called fashion semiotics.

Semiotics is the study of how people understand or make sense of life events or relationships. It is the study of sign processes and meaningful communication. Likewise, fashion is a language which holds a symbolic and communicative role. It helps express one’s unique style, identity, profession, social status, and gender or group affiliation. Therefore, the semiotics of fashion is the study of fashion and how humans symbolize specific social and cultural positions through dress.

Garments are non-verbal signs that can be interpreted differently depending on the context, situation or culture. Hence, fashion significance is constructed depending on culturally accepted codes. For example, in Western cultures white color is chosen for weddings because it represents purity while in Asian cultures this color means death and is most likely used in funerals.

Dress codes identify individuals within a culture. (x)

The same thing applies to how costumes work as meaningful elements in a visual narrative - and this is exactly the approach that Michele Clapton has adopted for her work on GoT:

For her, the key is looking at costume design as a mode of storytelling. “It’s so easy to draw a pretty dress in a fun way,” Clapton told Fast Company. “But this is so much more about finding the right look and telling so much more about that character, and that’s what I really, really enjoy: the storytelling.” (x)

Therefore, when we look at the costume design in this show, we have to ask what it says about the characters.

So what does Margaery Tyrell’s costumes say about her in season 2?

BOLD AND SEDUCTIVE

Margaery has three different costumes in season 2. Two of these dresses have the same basic design and silhouette whereas the third is perhaps one of the most unique costumes in the entire show. I’m going to start with a look at the gown we see in Margaery’s last scene in season 2 - the light blue gown with the rocaille pattern on the bodice.

Unlike the red-gold costumes of the Lannisters in season 2, Margaery’s costumes don’t use the green-gold colours of House Tyrell. This is something that a number of fans objected to but this article argues that the use of light colours such a soft blue and purple serves as a subtle contrast to the power dressing of the Lannisters. The Tyrells are just as ambitious as the Lannisters but they are subtle about it and with the use of soft colours, they make themselves look non-threatening whilst they secret plot to extend their political influence.

This dress also feature a rocaille pattern on this bodice. In an art historical context, rocaille denotes an exuberant and elaborate form of ornamentation associated with the rococo style of the 18th century.

The aristocratic culture that the rococo style is associated with was in many ways a hedonistic, sophisticated and somewhat frivolous culture that put a lot of focus on the love of pleasure. In the context of this costume, the use of the rocaille pattern may serve as a hint that the culture of the Reach, which the Tyrells rule, is one associated with abundance, pleasure and cultural sophistication.

Another aspect of this costume is that it is quite revealing - as we’ll see in season 3, the costumes of Margaery Tyrell and her ladies feature a lot of cut-outs as well as plunging necklines, which hints at the warmer climate of the Reach as well as a more hedonistic culture than what we see in the North and the Crownlands. The most noticeable element of this dress is the plunging neckline, which emphasizes Margaery’s bold sexuality. However, the revealing nature of this gown also works at a metaphorical level:

Cersei hides behind her clothes, and Margaery instead chooses to expose herself. A very nice and metaphorical way of showing to the people at King's Landing that she has nothing to hide. This also allows her to expose large amounts of skin, which not only helps cement the idea that the Tyrells come from a warmer weather (as mentioned earlier) but also helps cement the idea that she uses her sexuality and femininity as a political tool in itself. Presenting herself as a young, delicate and alluring girl, she avoids being perceived as a player in the game, even though she very much is. (x)

It is thus ironic that Margaery wears this particular outfit in a scene where she is dishonest when she talks about how she’s come to Joffrey from afar. In this scene Margaery acts bashful and girlish, the role of the innocent maid, which the audience already knows is an act.

During the entire conversation between Joffrey, Loras and Margaery, she utilizes a specific kind of performative femininity, i.e. she tailors her courtly performance so it conforms to a very specific ideal of femininity: the bashful and innocent maid. Notice how she initially keeps her gaze lowered, signalling meek sub-mission. When Joffrey professes his admiration of her, she lifts her gaze and bats her eyes at him, which is a very calculated move. (x)

This is underscored by a costume where the sexy neckline stands in contrast to the softness of the light blue colour. In this context, it is interesting to compare and contrast Margaery’s costume with one of the dresses that Sansa Stark wears in season 1.

Whilst the colour is very similar, the cut and silhouettes of the two gowns couldn’t be more different. Sansa’s gown is modest and loose, hiding her body, whereas Margaery’s gown is close-fitting and very revealing. This highlights the differences between the two characters. Sansa IS an innocent young girl whereas Margaery is a sexually confident woman who simply plays the role of the bashful maid.

FASHION QUEEN

Let’s take a look at the costume Margaery wears when the audience is introduced to her character. First of all, this gown is identical in design to the light blue gown I mentioned above. However, in this scene Margaery has donned a rather unconventional cloak that stylistically sets her apart from any other female character we’ve seen so far.

Like the gown above, this outfit emphasizes Margaery’s confident sexuality. Not only does it have a deeply plunging neckline but the beaded strings that are attached to the button at the front of the cape serve to draw visual attention to her exposed cleavage.

Apart from the plunging neckline, the most visually arresting element of this costume is the structured shoulders of the billowing cloak. This gives the outfit a slightly armoured “feel”:

She dons a billowing cape with structured shoulders that give a sense of armor. It is interesting to note the armor-like aspect of most of Margaery’s season two outfits. She spends the majority of the season at Renly’s camp in Storm’s End while the Tyrell/Baratheon forces prepare for war. Without the security of castle walls for protection, perhaps this is her more feminine way of being always armed and on guard for whatever is in store. (x)

The armoured aspect is an interesting one in terms of character. However, in relation to this costume the armoured “feel” of the shoulder piece takes on a rather tongue-in-cheek aspect since it is paired with a very lightweight fabric that billows in the wind. This is play-acting, which resonates perfectly with Margaery’s presence at a tourney where knights play at war whilst a real war rages elsewhere. However, this costume also signals that Margaery is fashion-forward in a sense few other Westerosi women are. She’s the consort of a royal pretender who wants to present an alternative to the current regime - and Margaery mirrors that by setting herself up as stylistically different, as a future taste-maker.

It is interesting to note that Margaery wears a kind of scarf underneath the bodice in order to make the neckline LESS revealing. The tent scene with Renly shows EXACTLY how deep the neckline really is.

Here the revealing nature of the costume supports both the narrative and the character. In this scene Margaery tries to seduce her reluctant husband but she also reveals her pragmatic nature - as I’ve detailed in my previous post.

ARMOURED IN FASHION

The third costume that Margaery Tyrell wears in season 2 is perhaps the most avantgarde and also the most controversial costume on the show. I am, of course, speaking of the now infamous funnel dress that Clapton designed as an homage to Alexandre McQueen’s iconic Bell Dress that he made for Björk in 2004.

Margaery's funnel dress was obviously an homage to the wonderful Alexander McQueen's costume for Bjork. It just felt right that this young ambitious girl would be experimenting with shapes, honing her style skills which we now see her employing to great effect. It was a risk and divided the audience. (x)

“From the very beginning she is brave and experimental in her look, which I wanted. She was a young girl who wanted to be the queen,” Clapton explained.

Margaery is often spotted in revealing or outré outfits. One episode she wore a funnel dress that Clapton told Vogue was an homage to an Alexander McQueen dress made for Bjork. “It was ridiculous. She’s a teenage girl trying things out.” (x)

Clapton designed this dress to emphasize that Margaery is rather avantgarde in terms of style. She’s experimenting style-wise but this look is so radical in relation to the rest of the fashions of Westeros that I cannot help but think that she’s also trying to create a new paradigm. She wants to stand out, to be seen as different from everybody else.

Another aspect of the funnel dress is that it has an armoured “feel” that is even stronger than the structured shoulder piece she wears at the tourney. The dress itself is made from a much heavier fabric than her low-cut, lightweight dresses and it has a very structured silhouette - and in contrast to her two other gowns it covers her completely.

The funnel dress essentially functions as a structured coat-dress that Margaery wears over one of her more revealing dresses. If you look closely, you can see that the blue sleeves with the cut-outs over the shoulders match the seductive blue dress that she wears in the scene where she’s betrothed to Joffrey.

Once again, the costume design supports the overall narrative since Margaery wears this dress in two scenes where she is in a defensive position - Lady Sansa Stark was taught that courtsey is a lady’s armour but for Margaery, fashion can be armour as well:

We witness Margaery’s armor full-on with her infamous “cone-dress”. She wears this in two scenes, and is speaking with Littlefinger in both. She knows this is a man with whom you must always be on your guard, and this is reflected in the heavy satins and silk embroidery, but she keeps her shoulders exposed just enough to maintain a feminine air. (x)

It is noteworthy that Margaery only wears this dress in scenes where she is in a defensive position. The first time in the scene with Baelish where he’s questioning the status of her marriage to Renly and the second time after Renly’s death where Margaery is quietly scared because she knows exactly how dangerous the situation has become for both herself and her family.

TOO AVANTGARDE?

The funnel dress turned out to be a very controversial costume in terms of audience reception. It was the subject of a number of think-pieces but here I’ll just focus on article since its arguments exhibit a couple of different argumentative fallacies.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way first: this costume is ugly. It has no redeeming qualities. It isn’t fashion-forward in any sense. It isn’t interesting. It isn’t even well-made (note the seam where the pattern does not align: on the front of the damn garment!). I can’t even give credit where credit is due regarding the embroidery, which must have taken hours, because the embroidery is so ugly. (Fandomentals)

It is a perfectly valid opinion to say that this dress is ugly. It is, after all, a matter of taste. However, the quote above is followed by this little tidbit:

....the sheer and objective ugliness of this costume. (Fandomentals)

It is one thing to say I don’t like this dress, it is another thing to call it “objectively” ugly as this is just manifestly wrong. When it comes to aesthetics, beauty is always in the eyes of the beholder. Presenting a subjective opinion as an objective fact is a bad faith argument and it undermines what the author’s point.

Then they go on saying that such an avantgarde dress is unbelievable in a feaudal society based on the medieval period of European history - conveniently ignoring that there plenty of outrageous and not very functional fashions has existed throughout history.

While there are fashion trends in Westeros, there isn’t high fashion as we know it today. No one is picking bizarre pieces off the runways in Milan or opining over Vogue. There are no catwalks in the Reach, and there is no King’s Landing couture (though I wish there was!). Westeros is a world based on medieval human history, where men and women wore clothing to express their status in society. Clothing served a functional purpose and certainly did not step out of the norm to this extent. (Fandomentals)

It is also an argument that displays a lack of knowledge about the history of dress. Whilst there was no fashion industry in the middle ages and the renaissance, the concept of fashion as related to clothing styles did in fact exist as early as the 12th century:

How are we to distinguish between a culture organized around fashion, and one where the desire for novel adornment is latent, intermittent, or prohibited? How do fashion systems organize social hierarchies, individual psychology, creativity, and production? Medieval French culture offers a case study of "systematic fashion", demonstrating desire for novelty, rejection of the old in favor of the new, and criticism of outrageous display.

Texts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries describe how cleverly-cut garments or unique possessions make a character distinctive, and even offer advice on how to look attractive on a budget or gain enough spending money to shop for oneself. Such descriptions suggest fashion's presence, yet accepted notions date the birth of Western fashion to the mid-fourteenth-century revolution in men's clothing styles. A fashion system must have been present prior to this 'revolution' in styles to facilitate such changes, and abundant evidence for the existence of such a system is cogently set out in this study. Ultimately, fashion is a conceptual system expressed by words evaluating a style's ephemeral worth, and changes in visual details are symptomatic, rather than determinative. (x)

Secondly, fashion trends most certainly did exist in the past - just not in the forms we know today, i.e. supported and embedded in an industry. During the medieval age, the renaissance and the baroque the taste makers who set the fashion where individuals, royal and aristocratic men and women. There are numerous examples of aristocratic fashions that were not about function but about display. What this writer fail to understand is that all clothing is part of the semiotics of fashion. Clothing and bodily decoration have always been both about beauty as well as about signalling social standing and/or political affiliation. ALWAYS.

Thirdly, costume design is an integral part of the visual story-telling and thus the costumes serve a larger function than just world-building. The relation between story-telling and costume design is something that Clapton herself emphasizes:

...viewers should consider the bigger picture and storyline to understand costume choice–or even to look for hints about how a character is evolving. “I don’t think any costume should be looked at in isolation, rather, through the arc of the character,” Clapton says. “Each thing will tell a story. It might look like a costume is wrong, but actually it’s supposed to look like that. It’s telling you something about the character at the time.” (x)

Ultimately, the question is not whether Margaery’s funnel dress is ugly, pretty or historically correct. It serves a narrative purpose and it serves it well as I’ve argued above. Not only does this dress reflect Margaery’s bold personality but it also functions as her armour in situations where she is in a defensive position and in that context I find that this particular costume makes perfect sense.

A QUEEN WITHOUT A CROWN

There’s one final detail that I want to address. Unlike her husband, Margaery doesn’t wear a crown even though she is addressed as Your Grace, which is a title reserved for royalty. From a Watsonian perspective it would make sense for Margaery to wear a crown since she’s the consort to a man who has proclaimed himself king and who wears a crown himself.

However, in this case, Margaery not wearing a crown is connected to her narrative arc. In the scene with Baelish where she proclaims that she wants to be THE queen, Margaery has come to realize that “Calling yourself a king doesn’t make you one”. She realizes that Renly wasn’t really a king and therefore she wasn’t really a queen. Clapton pays attention to details like this and that is why she didn’t make a crown for Daenerys in season 7:

Well, she's not the queen yet. You can't have a crown until you are queen. You can have the chain, but until you get the throne you're not queen. (x)

Thus, the fact that Margaery never wears a crown during her short-lived marriage to Renly is less about world-building and more about the narrative.

Thanks to @lilbreck for the edits.

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

JOE DALLESANDRO: Body Worship

The faces and voices of movie stars past and present continue to be extensively written about and well covered, but what about the bodies on the screen? We saw most of Rudolph Valentino’s body, and enough of Clara Bow to want more. Jean Harlow iced her nipples to make them stand out and up at attention under her gowns, and Tyrone Power loved to wear the tightest possible pants to display his lower extremities. It was only in the 1950s, though, that Marilyn Monroe and Marlon Brando tested the limits of their clothes and wantonly imposed the fleshiest grabbable flesh. In the 1960s, the women in movies started getting rail-thin while one muscular and fleshy man took all of his clothes off on screen without any self-consciousness. In the area of exposing and idly flaunting on-screen flesh, this man is the all-time champion, and much more besides.

His name was and is Joe Dallesandro, a kid from the mean streets of New York who stole cars and went to reform school and acquired a scar on his knee after a gun battle with police. As a teenager, he began posing for nude photographs out in California, and he learned how to hit up gay guys for bread. “I’d come from New York where I’d seen people do the hustle,” Dallesandro said, “and I knew people could get away with anything if they just knew what to say. My hustle was about getting anything I could for nothing.” Back in New York at age eighteen in 1967, Dallesandro wandered into a Greenwich Village apartment where a movie was being shot, an underground movie made under the auspices of Andy Warhol and his Factory but controlled by Paul Morrissey, a mysterious, conservative figure who looked at Dallesandro and immediately liked what he saw.

Dallesandro went out to Arizona with the Warhol crew to make Lonesome Cowboys (1968), a queer anti-western where he does a hilariously open and polymorphously perverse little dance with sprightly Taylor Mead and is coached to do ballet pliés by another cowboy in order to build up his legs and butt (which certainly needed no building). At one point in San Diego Surf (1968), Warhol superstar Viva accidentally drops a baby and Dallesandro moves with a lightning fast reflex to catch it. At this point, it was clear that Dallesandro had a beautifully balanced and open face, with a sunburst smile that made him look innocent and childlike, and a body to make Michelangelo all hot and bothered. But he also had the pinched voice of a New York wise guy and skin that made it look like he probably ate mainly pizza. This contrast moved Morrissey, and maybe he was also moved by the knightly, responsible way that Dallesandro caught that baby before it fell to the ground.

In 1968, for very little money, Morrissey created a whole vehicle just for Dallesandro called Flesh, a film that nods to earlier Warhol experiments by opening with a two-and-a-half minute shot of Dallesandro’s sleeping face. After being rudely awakened by his demanding wife (Geraldine Smith), Dallesandro passively complains that she never does his laundry; he says a man’s job is protecting his family. He is wearing nothing but a cross around his neck.

Put-upon and beguilingly passive, standing in the street waiting for guys who might give him some money for nothing or for something a little more, Dallesandro in Flesh is as un-self-conscious as Louise Brooks in Pandora’s Box (1928), but his energy is more inward-directed. He doesn’t “act” so much as enter fully into any scenario Morrissey has given him like a little kid playing “let’s pretend” in their backyard. Every kid plays “let’s pretend,” but some kids are just more fun to play with than others, and the camera picks up on that, just as the person directing behind the camera can become entranced.

There are close-ups of Dallesandro in Flesh that stop the movie dead in its tracks. Like Marilyn Monroe and James Dean, Dallesandro knew exactly what to offer to a still camera, assuming all the attitudes from Back Off to Come Hither to Take Care Of Me. And always, essentially, he is distant and removed, which is his real trick, the thing that keeps people coming back for more. Often fully naked on screen, Dallesandro offers all of that bounty to the camera, but he keeps himself to himself.

In Lou Reed’s hit song “Walk on the Wild Side,” one section claims, “Little Joe never once gave it away/everybody had to pay and pay.” But Morrissey in Flesh is saying, even howling, yes, you can all have or stare at his body, but look at who he is! Look at all the beauty there in his face, in the way he moves, and particularly in his innate sense of masculine responsibility. He’s very funny in Flesh when he looks frankly bored and forlorn with some of his chattier clients, like a kid made to stay after school in detention who would much rather be outside, but his face is usually such a patient face, a stoic face, and always rivetingly photogenic. Maybe his screen presence is a bit of a hustle, too, but if it is, I’ll gladly pay and pay.

Morrissey’s conservatism might not come through as strongly as he thinks in his early films because he often ceded them to charismatic speakers for hedonism like Holly Woodlawn, who made a comic and tragic thing of her love for Dallesandro in Trash (1970). In that movie, Dallesandro plays an impotent drug addict who seems more dead than alive as women and men paw him and clutch at him. When Woodlawn is forced to use a beer bottle to get off sexually, Morrissey makes sure to cut to a close-up of Dallesandro holding her hand, one of the most moving images of tender disconnection in all of cinema.

Morrissey played Svengali with Dallesandro, who worked at Warhol’s Factory, trying to mold him into an ambiguous and unchanging star like John Wayne or Marlene Dietrich (at this time, Morrissey often spoke of wanting to remake The Blue Angel {1930} with Dallesandro playing Dietrich’s role of the inactive femme fatale Lola-Lola). In Morrissey’s Heat (1972), Dallesandro is cast as a washed-up child star angling for a comeback amid the hothouse improvisations of Sylvia Miles and Pat Ast. He has moved even further into a kind of waiting catatonia, but even at his most sedentary and unresponsive, Dallesandro signals that he is always on the make, occasionally throwing out a zinger when you least expect it just to prove that he can pay close attention to what’s going on around him when he wants to (but he usually doesn’t want to). Morrissey took his star to Europe to make back-to-back horror films, Flesh for Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula (both 1974), where Dallesandro has his funny, incongruous moments but mainly takes a backseat to the campy authority of Udo Kier.

Dallesandro decided to strike out on his own in the mid-1970s, and the results were rich and varied. “How’s it goin’?” he nonchalantly asks a moaning woman he is humping in Donna e Bello (1974), checking on her pleasure before sneaking a look at his wristwatch, like Jane Fonda does in Klute (1971). He made a lot of films in Italy where he was cast as psychos on crime sprees, yet those movies still captured moments of film-stopping purity in his face.

This quality he had was picked up on by Louis Malle, who made Dallesandro look princely and storybook-like in his experimental feature Black Moon (1975). Best of all in this period, Dallesandro appeared in Je t’aime moi non plus (1975), a vibrantly strange road picture directed by bad boy French songwriter Serge Gainsbourg. In that movie, Dallesandro plays Krassky, a gay truck driver who falls for Johnny (Jane Birkin), a roadside waitress. Maybe it’s because he’s dubbed in French, but in this movie something very romantic and almost Byronic emerges in Dallesandro, with elements of the goofiness that he had shown when he danced with Taylor Mead in Lonesome Cowboys.

While working in Europe, Dallesandro collaborated with a remarkable array of intriguing directors. In Walerian Borowczyk’s The Streetwalker (1976), Dallesandro himself pays for lady-of-the-night Sylvia Kristel. For the young Catherine Breillat, he was a sex object to a female director in Tapage nocturne (1979). During the making of Jacques Rivette’s Merry-Go-Round (1978, but only released in 1981), Dallesandro, his co-star Maria Schneider and Rivette himself were all in despair and trouble of some kind in their personal lives, so that the film has a very unsettling air of real desperation underneath Rivette’s suggestive, paranoid mise-en-scène. This is Dallesandro’s most touching work on screen. Even though he seems at the end of his tether in Merry-Go-Round, he still tries his very best to make sense of it all, like a kid trying to play a game when the rules of that game keep changing. Again, what comes across here is Dallesandro’s helpless sense of responsibility, the fact that he cares and wants to tidy up messes other people might make.

After beating a drinking problem, Dallesandro returned to the US and drove a limo for a while before being tapped by Francis Ford Coppola to play Lucky Luciano in The Cotton Club (1984), a film that he steals with his suave self-assurance in spite of limited screen time. In the movies he made after that, for Blake Edwards and John Waters and for many lesser talents, Dallesandro is never less than fully present and usually very inventively foul-mouthed. In Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey (1999), Dallesandro has a colorful small part as a slow henchman who manages to sink a shot on a pool table to his own much-evident and childlike delight. Let’s pretend!

In recent years, Dallesandro has managed a building in LA and he often single-handedly makes Facebook worthwhile with friendly quips, clips and all-around survivor humor. He’s cool with being a Sex God, skeptical of mythmaking, and quietly proud of his movies and his image. His Morrissey films secure him a place in film history, and his European work awaits further and more detailed investigation. He is an icon of a period and milieu when sex did not have boundaries, when pleasure was a vocation and a principle, and when a man taking off his clothes in front of a camera could not divert us from trying to find the part of himself that he would not give away.

by Dan Callahan

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata (1964, India)