#line of grór

Text

The young siblings Thrór and Grór in Ered Mithrin

#Thrór#Grór#grór of the iron hills#Thrór King of Erebor#line of thrór#line of grór#sorry that I neglect you Frór but I haven't finished your design#the hobbit#lord of the rings#tolkien#longbeards#durin's folk#line of durin#dwarves#dwarfling#young dwarves#dwarven children

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me when I think about how Thorin was the eldest of three siblings (Dís and Frerin) one of which died horrifically at a young age (Frerin, age 42). About how Thror was also the eldest of three siblings (Frór and Grór) one of which who also died horrifically at a young (Frór, age 37). About how they both had to step up to be king when they were still so young because their fathers died in battle. About how both of them lost their homes to dragons. About how the ransacking of Ered Mithrin was probably just so much worse than the ransacking of Erebor because it lasted for 20 years. Thinking about how Ered Mithrin was attacked by the cold drakes so instead of dying by dragonfire all those dwarves died by tooth and claw. About how Thrór (and Grór) both had to watch their brother and father be barbarically torn apart. About how Thrór then had to see his greatest accomplishment, Erebor, fall to dragonfire. About how Thrór and Thorin were both SO MUCH MORE than the gold sickness…

#I may not have worded this as well as I wanted too#can you tell im in a mood today?#thrór#thrór king under the mountain#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#frór#thorin oakenshield#lady dís#frerin#line of durin#sons of durin#dwarves#Tolkien dwarves

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark and nameless things

3/4 for @mrkida-art

4k words

Grór and Ixil go exploring.

“Far, far below the deepest delving of the dwarves, the world is gnawed by nameless things. Even Sauron knows them not. They are older than he.”

See Notes at the end for Khuzdul/dwarf/Jew meta if interested!

--

Ixil stilled ahead of Grór, raising his finger for silence. She heard it, too: the far-away plink of a stone falling to the cave tunnel floor. Grór swung the lantern she was carrying out above both of their heads. It was frigid amid the dense stone, and their breaths misted in front of their faces as they held still. A dwarf’s hearing was intensified underground, but even they struggled to detect anything in these deep places.

“The stone is ancient here. I sense the heaviness of the Ages.” Ixil’s voice was low and reverent as he brushed his gloved fingertips over the wall. They traced the natural curve of the cave; no chisel marks had been struck into it, nothing to guide or set its way through the mountain. The floor underfoot was slightly damp, and Grór could tell from the look of the cavern sides that it had once been a water conduit — or maybe it still was when it rained, or when ice melted on the high passes. She peered at the map that archivist Barek had given her and Ixil to follow with the known systems laid out in red ink.

“The Grey Mountains connect to Gundabad, in the west,” Grór said lightly, refreshing her memory of the way they were going to take for the next day. If Grór closed her eyes and focused, steadying her breathing and reaching out with the stonesense innate in dwarves, she could almost see the pulsating soul of Gundabad far off in the distance. It was a shadow in the back of her mind, clinging to the edges of thought like a faint childhood memory, despite the young dwarf not having seen it in person. The clouded, snow-crusted peaks loomed large in her dreams, though; in the dreams of all Longbeards for generations before her. But, although she could tell there was a kernel of sacredness there still, buried like a seed deep inside the place where Durin slept, her ancestors’ halls were a mere nest of orc filth these days. She spat on the floor as she thought of the desecration.

The rock here was untouched by any goblin or orc hand: banded, tense granite pressed around her like the embrace of an overbearing elder. The stone’s distinct personality was evident. Slow, stuffy, dense, dark. It was as ancient as the very roots of the world, and it did not speak, unlike the stone around her father’s halls; but it held a still, secretive silence, bearing witness to their journey.

“Then these mountains share in Gundabad’s khavnah — the same remnant of Amad Durin’s spirit dwells here, too,” Ixil replied. The lines of stone warped and striated across the tunnel like the brush-strokes of a painter, zig-zagged and dripping into melting patterns. Grór and Ixil marvelled together, and for a moment both dwarves were lost in their own minds.

Ixil touched Grór’s shoulder gently and she let go of her reverie. They needed both of their wits if they were going to find the fissure Barek had told them of. Their mission, sprung on them that week by the king, was to travel to the edge of the kingdom and to the site of a known split in the rockface which led to the outside. One of their drake-scouts had reported it from atop a far vantage point, seeing it widened significantly by a fresh landslide. In quieter times, this may not have been something of note, but with a recent uptick in goblin and orc activity, the hole into the mountain passageways could prove an entrance for any number of unwelcome guests. Barek, the hold’s chief archivist and historian, had fished out an old map from the days when this part of the Ered Mithrin had been first inhabited by dwarves, and worked with several of the scouts to plan a route to get there that wouldn’t take them across the open mountainside. Grór was confident enough to travel unaided with Ixil in the winding mountain paths, but it was safer to go underground, where the only trouble you would run into were the bats. She still hated the nasty, flying rats, though, and closed her eyes to slits whenever they had to pass underneath a hanging swarm of them. But now they were far away from any habitable parts — deep in the areas of caves that had been forgotten about for generations.

They walked on in silence, Grór occasionally checking the map and knowing just by the feel of the ground — the tiny indications in rock formation and slope gradient, which only a dwarf could internalise — that they were correctly headed. Ixil was unusually quiet, pausing like a hunter at every sound or to comment on the taste of the air on his tongue. Grór, on the other hand, had never felt more alive: close to the mountain’s inner parts, her body fizzed as she soaked up the energy of the abundant stone through the soles of her boots. Quartzite and granite intertwined, melded together like lovers; and as they descended into hidden pools, limestone figures reared grotesque heads and thickets of stalagmite spines marched down the sides of humongous caverns, which sparkled with cloudy crystals. Ixil stopped by the water in one of these and squatted down to study the refractions of Grór’s lantern off the surface.

“Not good,” he muttered.

“Not for drinking, then?”

“No—” the Stiffbeard pointed to some of bulbous clusters of crystals which lingered underneath the surface of the water, some of which looked almost furry to the eye. “Those are not good rocks, they taint the water.” Grór sniffed — there was definitely a whiff of something unsavoury. Not enough to kill a dwarf, but a Man, with a Man’s constitution, would have probably died within a few minutes.

They continued on — Grór’s old leg injury was beginning to ache. The bone had healed well, but the tendons in her ankle and knee now protested even after eight hours of trekking, which she could have managed with ease before. Ixil slowed down and shot her a look of concern, but she shrugged.

“I’m fine — let’s go on.”

“Your foot hurts?”

“Yes, but I can walk on for an hour more before we make camp. We should probably stop and eat soon anyway.”

Ixil nodded in agreement and matched Grór’s pace, tightening the belt which secured his own pack. Grór straightened her tired shoulder and cast the lantern light about them as they descended into a path that dropped quicker than they were expecting. A reference to the map told them that this was indeed the way — but it felt that they should be going upwards at some point. The darkness was absolute here, cloying and crushing, and Grór’s heartbeat picked up the deeper they went. She reached out with her stonesense to soothe her, but got back a silence even more profound than that which she felt earlier.

She couldn’t even name these rocks.

This horrific realisation stopped her in her tracks and she almost ran into Ixil’s back. The other dwarf was gazing like a cat into the darkness, one hand flung out to his side.

“Something’s there,” he breathed.

Grór was about to ask what he meant by that, when she heard it, too.

The noise was carried on a draught of fetid air that wafted into their faces, which came from a medium-sized cavern before them; according to the map, straight ahead was a chamber with many exits branching from it like the fingers of a hand. At first, the sound was so faint that she thought it came from somewhere high above them, but the longer she listened, the clearer she could trace it to down one of these many tunnels: an unmistakable deep, growling hiss. Rising and lowering in pitch and intensity — sometimes as low as to be inaudible, yet Grór felt it vibrating, grating, against the stone.

Animal? she signed in iglishmêk. But what animal could possibly be living down here? Nothing larger than a bat could possibly survive, unless this was something from the outside that had got trapped somehow.

Ixil didn’t reply. He jerked his head, wide eyed.

Back.

No — we need to go on — go down on the left route.

You are insane.

Grór rolled her eyes. Do you have a better idea? Return home? If it follows us, we will kill it.

She pinpointed the sound to a crooked path on their right — hopefully, their way would take them far away from whatever was down there.

Ixil shrugged begrudgingly. They both crept forwards, and Grór extinguished her lantern as they rounded the corner, their iron-shod boots making no noise against the ground as they lightened their pace. Despite Grór’s bravado, she didn’t reach out with stonesense. She didn’t want to know. Let the nameless stones and nameless creatures be nameless, as far as she was concerned. She held her breath and took the lead, beckoning with one finger for Ixil to follow. It would only take a few, quick paces. Then it would be over.

—

The Stiffbeard hadn’t fully recovered. He sat hunched over with his back to the cavern wall, staring at the entrance of the small pit as though he were trying to bore his way through. The rest of their journey had been uneventful, and after descending for a hundred feet or more, the path had slowly risen again. Even Grór, accustomed to walking in the deep ways, was grateful at the pressure equalising, and here the air felt cleaner, younger. The vibrant stone hummed and mumbled around her, coloured in dusty rose-flushed hues and flecked with brown, sparkling deposits. Before fear had frozen him to his spot, Ixil had searched the walls for the trickle of fresh water that had snaked its way down to form a small stream, and after tasting it, decided that it was ‘good enough’. The lantern had been lit again after travelling for almost an hour without it, but even its reassuring light did nothing to force the other dwarf from his torpor. He didn’t want to speak. He didn’t want to eat. Grór waved a strip of rehydrated, salted meat in front of his face, but when Ixil simply pushed her hand away, something snapped.

“What’s wrong with you?” she asked, irked at his behaviour. “Is it the — noise?”

Whatever it was, it was none of their business. They had left it well alone, and it had not followed.

Ixil looked up at her with dark eyes. His skin still had the pale pallor of horror and he peered from her face to over her shoulder.

“Why aren’t you scared?” he asked slowly, refusing to raise his voice above a guttural whisper.

Grór shrugged — she didn’t know why she wasn’t. She was concerned; intrigued, maybe. But it wasn’t an orc, she assumed that much — and there were two of them and one of it, and they were armed. Grór had with her an axe and a wide-bladed hunting knife slung about her waist, and Ixil had a mattock affixed to his back and a sharp Eastern falchion which was sheathed in a holster of mammoth tusk ivory and beaten silver. If it was about the size of an orc, they could kill it. They’d fought worse together with the Ered Mithrin scouting parties and survived — mountain goblins and orc warriors who were crossing to the Misty Mountains. If it was larger than an orc… well, they were miles from home and without help. What could they do?

“I would be scared if I knew that it was something to be frightened of. We don’t even know what it is first. Could be nothing.” It probably wasn’t, but it was the best Grór could come up with to reassure Ixil.

Not for the first time, the Stiffbeard looked at her as though she were mad.

“You mean… there are no nuruk, surgashi, or rukuz in these hills?” Ixil replied, half as though he was patronising her, and half as though he wanted to believe it.

“The what, what, or what?” asked Grór.

Ixil smiled and shook his head. “Sometimes, I forget how different the dwarves are, Clan to Clan.” He thumbed a pendant which he wore around his neck: the strap of leather held a small icon of some sort of three-headed animal wrought from iron. After a moment of consideration, he took it off and fastened it around Grór’s neck. She looked down at it, surprised at the gesture, but she was unable to tell even from up close what it was.

“And — will this save me from the Eastern Death Weevil, or whatever it is you have in those parts?” she asked. The other dwarf rolled his eyes, but he didn’t look angry.

“Far below our delvings, the world harbours many things that even the orcs and their masters do not know about. As old as the earth. We have stories about them — but they are real—”

“Have you ever seen whatever beasties you mentioned just now?” Grór replied quickly, cutting Ixil off sharply. Ixil huffed under his breath and frowned.

“Have you run into Durin’s Bane itself? And yet you know very well it existed. Our stories come from fact and the wisdom of our ancestors.”

“Well, all dwarves know about Durin’s Bane,” Grór retorted, “but I have heard none of those names uttered by any dwarf before. They must just be in the East.” She dug out a whetstone from her pack and begin idly stroking the head of her hunting knife, not wanting to press the subject any further for fear of accidentally offending Ixil. But something about the oddness of those strange sounding words peaked her interest.

“What are they?”

—

Ixil ate for the first time since they sat down, tearing chunks off the meat hungrily and washing it down with a swig from a canteen of water. The dwarf looked ruefully at the container, as though he would have liked it to be filled with something stronger. Grór grinned and pulled out a bottle she had stashed away in her pack. Taking any liquid that wasn’t water with them was not the smartest idea, but she had somehow known the time would come for drink. She handed it to Ixil — it was strong potato liqueur, and a little went a long way. She sipped, grimaced and threw the bottle across to the Stiffbeard.

“A dwarrowdam after my own heart,” he said, taking in a large mouthful, as though the astringent alcohol was a nectar.

Something odd wriggled inside Grór’s stomach at those words, but she ignored it and grabbed the bottle back.

“Don’t drink too much, I only packed one. Or two. I’m not telling.”

She wiped her mouth with the back of her hand and scooted across the floor of the cave, settling next to Ixil by the greenish glow of luminescent ghaspar chunks that overhung them high up in the eaves of the cavern.

“It is hard to explain the creatures to you, if you have never heard the old tales our grandparents tell over the fires at Bekshoz. That is when the evil that haunts the mountains is most prevalent — when the separation between living and dead is thinnest. And we have no fire here. I hope there are none that have found there way to the Grey Mountains.” Ixil shivered, casting a wary eye back up at the tunnel entrance. He then glanced down at Grór’s chest. “But you are protected.”

“What is it?” Grór asked, fingering the iron trinket. Ixil touched it briefly, then pulled his hand back, quickly looking up into Grór’s face and then away again. She felt blood rush into her cheeks, and the ‘something odd’ she had felt before resurfaced.

“It is a good-luck charm. A protection from nuruk,” Ixil said hurriedly, turning back to face the entrance and reaching for the alcohol bottle again. “The nuruk are spirits — dark ones that trick and harm people. We Stiffbeards believe that they come from deep places in the earth, and use the cavernways to travel to the lands of the living. That is why miners carry these amulets, or anyone who travels in untapped and wild passes beneath mountain halls. The nuruk are like water rising through the earth, slowly filtering through after thousands of years, and once they are in a hold, they can enter a home, or a dwarfling’s cot, or a well — and poison the whole thing!”

“Huh,” Grór said, “but — what do they look like? Like this… thing?” She looked down at her chest, turning the iron ornament this way and that. Ixil laughed.

“No — not like that. They are invisible, so we need priests to speak words of Mahal over a home to get a nuruk out, if they are suspected to be there. It is what makes them so dangerous. Some miners or tunnellers refuse to call each other by name when they are digging, as they fear that once a nuruk hears a dwarf’s name, it can latch onto the person and ride with them all the way up to the surface — or even turn them mad with fear, so that they never enter a mine again.”

Grór stifled a snort, imagining a small, wizened beast clinging with spindly arms around the neck of a burly miner like a small child. Then, she remembered something she had seen in Ixil’s home when she had first visited his family on the lower levels of Thikil-gundu. She had asked Bivrik what it was, but she hadn’t really retained its exact use until this moment.

“The bowl! The one that has the inscriptions on it — your ‘amad knocks it whenever someone enters the house, and she said it was to get the nuruk away!” Grór exclaimed.

Ixil smiled broadly. “Aye, though — even some among Stiffbeards might say she’s of the superstitious sort.”

“So,” Grór pulled at the leather thong around her neck, “what is this? The thing on it?”

“That is the spirit-form of our Eternal Mother — Ugzhar.”

Grór raised a bushy eyebrow. “I never knew your Founding Mother had three heads. Must be useful. You can drink, smoke, and eat at the same time.”

“Aye,” Ixil replied, “though I don’t think she was doing that in this form. Tales passed on before we wrote in runes say that at the end of her cycle of rebirth, Ugzhar became so enamoured with the Stiffbeard nomads — who at that time began to ride the shaggy mumak across the ice plains — her spirit form became a mumak itself, roaming with the nomads on migrations each season and keeping close to them. When the lights in the winter sky form an arc over Ugzharak, her birthplace, they take the form of a three-headed animal, and so the omen-sayers tell that her mumak form has three heads: one to look into the past of dwarven history, one keeping an eye on our present queen, and one seeing far into the future.”

On the whole, this was a far more pleasant and wondrous image than that of a nuruk. Grór hummed thoughtfully as she remembered Ixil mentioning the winter lights: green-tinted lightning that whipped across the frozen night above the high northern mountains, like the hand of a giant playing with bands of fire. Ixil’s father had been one of the nomadic dwarves, and he traced his lineage back to the first dwarves to live within the snowy tundra. She wondered if her father would allow her to leave the hold and travel to see all of this with Ixil when his homeland was rebuilt. Maybe the lights would flow once more across the sky, and Queen Ugzhar would smile upon her kingdom again.

“And what are surgashi, and ruh- ruk—”

“Surgashi are odd things. They live in abandoned cities and take over its ruins. In the dialect of the Stiffbeards, the kishki word ‘sur’ means little, and ‘gash’ is king. The king of the forgotten and tumbled-down places. All that their victims see are two yellow eyes before they attack, before their memories are wiped. Anyone stupid enough to explore without first checking for their presence wakes up miles away with their valuables stolen, and with no knowledge of how they got there.”

Ixil suddenly became serious and the light dimmed behind his eyes. “I don’t talk about the rukuz,” he muttered and looked longingly at the pendant around Grór’s neck. “But they fear iron. They fear iron, at least.”

“Rakhas — orcs, you mean?” asked Grór. Ixil exhaled sharply.

“If only they were orcs. They are the worst kinds of… sometimes, when dwarves have been sent to find the bodies of those attacked by rukuz, they don’t… well…” Ixil stopped speaking and his eyes flicked back and forth, flashing in the low light of the cave. Grór decided that this one could wait until they were outside under a bright sun, rather than ensconced in the dark of stone.

“I have heard stories of those kinds of things in Khazad-dûm,” said Grór, to break the silence. “Things that we dare not name.”

“What things?” asked Ixil urgently. Grór dragged up the hushed stories from her memories of youth. Thror used to love scaring her with them, but half the time she just thought he was deliberately making them up.

“Thror used to say,” she began, “that there were things that gnawed at the bones of the earth, hollowing out great chambers underneath Durin’s Stair. Dwarves knocked into underground rooms which had already been worked away at and fashioned into roads under Khazad-dûm.” She tried to remember what had made her so frightened of the stories, enough to run yelling into her father’s bedroom from fear. “Thror told me one story…” she shuddered, swallowed hard, and then went on, “about a mithril prospector who got lost somehow. Got turned around in one of the unmapped places with a strange stonesense to it. When a rescue team found his body, it looked like his face had been sucked straight off, and it was nothing more than a mass of raw pink flesh.”

Ixil made a disgusted face at her. “What could do such a thing?” he asked. Grór didn’t know if it was the proper name for them, but Thror had called them asmer — and his descriptions conjured up images of fat, sightless serpents, with the bodies of powerful worms and the heads of ghastly eels that contained rows upon rows of sharp teeth, and tentacles on their bellies that could turn a dwarf’s skin inside out. She told all of this to Ixil, who looked more and more nauseated.

“And — they can squish down into the tightest hole, out of sight, and the only thing a dwarf would hear is a deep, low hiss, before it devoured them.”

Grór’s eyes widened before she finished the sentence, and Ixil stopped, his hand half raised to his mouth, clutching the bottle. Their eyes met, and Grór knew he was thinking the same thing as her.

What had made those tunnels, that branched off into five, long, rounded passageways? What had they heard in the dark?

Before she could stop him, Ixil was shoving their belongings into bags with such frantic intensity that Grór had to grab his shoulders, though she herself was breathing hard.

“Calm d—”

“Let’s go,” Ixil whispered, “Grór, let’s just move on.”

Grór’s eyes were drawn towards the darkness in front of them, and to the axe at her side, which next to the hulking worm in her mind was little more than a butterknife. Had her brother’s stories been based on some fact? She didn’t want to admit it, but now she couldn’t help but imagine that beast slithering out of its hole and sniffing them out, following its nose until it reached them, asleep by the stream, and devoured them.

You’re being stupid, she chastised herself.

However — better to be prudent than to wake up in the maws of some horrible monster.

“Alright — the sooner we get a move on, the faster we return home,” she reasoned. The dwarves hoisted their packs and re-strapped their belts, fleeing down to the cave exit as swift and as quiet as their shadows flickering against the walls.

—

Somewhere, under miles and miles of twisting Grey Mountain caverns, the gargantuan outline of a beast rippled in the blackness. It lazily raised its head, the blind face moving this way and that. It thought it detected, for a moment or so, the whiff of a dwarf.

—

Notes:

Khavnah - spirit innate in all living things (including stone), taken from the Hebrew ‘kavanah’ - an intense spiritual focus and energy during prayer. Some dwarf clans believe that the Foremothers’ own spirits permeated the mountains upon their Awakening and lingers there still.

‘Amad Durin - Mother Durin. All of the Founders of the Dwarves were dwarrowdam/zhani (non-binary) dwarves in my headcanon.

Nuruk — spirits loosely inspired by dybbuk in Jewish folklore. Bivrik’s bowl is related to Jewish incantation/demon bowls found in early settlements, though these weren’t singing bowls, rather possessing scripture written on them to ward away influences of specific demons and the evil eye.

Surgashi — in Judaism, many shedim, or demons, tend to live in ruins and Prophet Elijah forbade Rav Yose to pray at a ruin (Berakhot 3b). It is interesting to think about ruins in conjunction with dwarven history. What demons might inhabit Khazad-dûm? Dwarves hold onto and venerate its sacredness in spite of the corruption of their ancestral home as we see in both The Hobbit and LOTR. Dwarf ruins are always haunted by something, be it a dragon or a Balrog… an interesting comparison to Jewish history.

Kishki — even though JRRT said there wasn’t dialectal changes in Khuzdul, I like to think so… Kishki is the northern dialect.

Iron — iron was used in Jewish rituals to ‘see’ demons. Metal and iron also have protective folklore in Jewish superstition: barzel, the Hebrew word for iron, is an acronym of the mothers of Israel (Bilhah, Zilphah, Rachel and Leah).

Rukuz — they attack prey with their bare hands, using long fingernails and crushing jaws to sever the necks of their victims.

#tolkien fanfiction#tolkien#the hobbit#The Lord of the Rings#lord of the rings fanfiction#dwarves#LOTR fandom#LOTR

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝚠𝚎𝚝𝚊 , 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 𝚌𝚑𝚛𝚘𝚗𝚒𝚌𝚕𝚎𝚜 , 𝚙𝚑𝚒𝚕𝚒𝚙𝚙𝚊 𝚋𝚘𝚢𝚎𝚗𝚜’ 𝚌𝚘𝚖𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚊𝚛𝚢 : ❝ what we wanted was to say that even with all the wealth of erebor , thorin could not rest until he had the arkenstone . this one peerless jewel was the thing that , in thorin’s estimation , bestowed kingship upon its possessor . without it he was not whole . he had invested so much meaning in the arkenstone that without it he felt his identity and legitimacy were incomplete . in the end , as impressive and otherworldly as it was , the stone was just a material object , a bauble , a trinket . its power was attributed and not innate . though he does not understand it , thorin has given that power to the stone and trapped himself . ❞

𝚠𝚎𝚝𝚊 , 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 𝚌𝚑𝚛𝚘𝚗𝚒𝚌𝚕𝚎𝚜 , 𝚛𝚒𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚛𝚍 𝚊𝚛𝚖𝚒𝚝𝚊𝚐𝚎’𝚜 𝚌𝚘𝚖𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚊𝚛𝚢 : ❝ the story already had the ring and the gold , so another talisman may have been one too many , but the right to rule , it being the king’s jewel , is where the power of the arkenstone lay . [ . . . ] ultimately , the arkenstone was just a gem and the power of loyalty was beyond a talisman . ❞

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚜𝚒𝚕𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚒𝚕𝚕𝚒𝚘𝚗 , 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚜𝚒𝚕𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚒𝚕𝚜 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚞𝚗𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚝 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚗𝚘𝚕𝚍𝚘𝚛 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟼𝟽 ) like the crystal of diamonds it appeared , and yet was more strong than adamant , so that no violence could mar it or break it within the kingdom of the arda . [ . . . ] and the inner fire of the silmarils fëanor made of the blended light of the trees of the valinor , which lives in them yet , though the trees have long withered and shine no more . therefore even in the darkness of the deepest treasury the silmarils of their own radiance shone like the stars of the varda ; and yet , as they were indeed living things , they rejoined in light and received it and gave it back in hues more marvelous than before .

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚜𝚒𝚕𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚒𝚕𝚕𝚒𝚘𝚗 , 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚜𝚒𝚕𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚒𝚕𝚜 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚞𝚗𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚝 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚗𝚘𝚕𝚍𝚘𝚛 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟼𝟿 ) for fëanor began to love the silmarils with a greedy love , and grudged the sight of them to all save to his father and his seven sons [ . . . ]

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚜𝚒𝚕𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚒𝚕𝚕𝚒𝚘𝚗 , 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚟𝚘𝚢𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝚘𝚏 𝚎ä𝚛𝚎𝚗𝚍𝚒𝚕 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟸𝟻𝟹 - 𝟸𝟻𝟺 ) but the jewel burned in the hand of maedhros in pain unbearable ; and he perceived it to be as eönwë had said , and that his right thereto had become void , and that the oath was in vain . and being in anguish and despair he cast himself into a gaping chasm filled with fire , and so ended ; and the silmaril that he bore was taken into the bosom of the earth .

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 , 𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝚝𝚠𝚎𝚕𝚟𝚎 , 𝚒𝚗𝚜𝚒𝚍𝚎 𝚒𝚗𝚏𝚘𝚛𝚖𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟸𝟹𝟷 ) ❝ the arkenstone ! the arkenstone ! ❞ murmured thorin in the dark , half dreaming with his chin upon his knees . ❝ it was like a globe with a thousand facets ; it shone like silver in the firelight , like water in the sun , like snow under the stars , like rain upon the moon ! ❞

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 , 𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚛𝚝𝚎𝚎𝚗 , 𝚗𝚘𝚝 𝚊𝚝 𝚑𝚘𝚖𝚎 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟸𝟹𝟽 ) it was the arkenstone , the heart of the mountain . so bilbo guessed from thorin’s description ; but indeed there could not be two such gems , even in so marvelous a hoard , even in all the world . [ . . . ] now as he came near , it was tinged with a flickering sparkle of many colors at the surface , reflected and splintered from the wavering light of his torch . the great jewel shone before his feet of its own inner light , and yet , cut and fashioned by the dwarrows , who had dug it from the heart of the mountain long ago , it took all light that fell upon it and changed it into ten thousand sparks of white radiance shot with glints of the rainbow .

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 , 𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝚜𝚒𝚡𝚝𝚎𝚎𝚗 , 𝚊 𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚎𝚏 𝚒𝚗 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚗𝚒𝚐𝚑𝚝 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟸𝟽𝟸 ) the elvenking himself , whose eyes were used to things of wonder and beauty , stood up in amazement . even bard gazed marveling at it in silence . it was as if the globe had been filled with moonlight and hung before them in a net woven of the glint of frosty stars .

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 , 𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝚎𝚒𝚐𝚑𝚝𝚎𝚎𝚗 , 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚛𝚎𝚝𝚞𝚛𝚗 𝚓𝚘𝚞𝚛𝚗𝚎𝚢 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟸𝟿𝟸 ) they buried thorin deep beneath the mountain , and bard laid the arkenstone upon his breast . ❝ there let it lie ‘til the mountain falls ! ❞ he said . ❝ may it bring good fortune to all his folk that dwell here after ! ❞

the arkenstone , the heart of the lonely mountain thus named erebor by the dwarrows and founded deep beneath its roots , was unearthed during the reign of king thrór and declared to be a divine show of his right to rule . thus the jewel was established to be a crowner of kings¹ , bestowing as much power as the descent of durin , for the dwarrows believed it to be a gift of mahal , put forth in the mountain as a homage to their race . in their creator’s honor did they mount it above the throne of thrór , where it glittered for all who sought audience with the king of dwarrows to behold² . inscriptions depicting the arkenstone were carved all throughout the mountain halls³ and upon great tapestries that hung in the halls of history and remembrance . so it remained ‘til the coming of the dragon , smaug , who claimed the mountain and all of its treasure , devouring the dwarrows within it . in this manner was the arkenstone lost , for thrór took it from his throne and carried it with him to the treasury , where the dragon was reveling in its hoard and causing great flying mounds of gold and gems with its wings . thrór fell , and the arkenstone fell with him , out of his grasp and into the swell of coins that mounted the steps before him . as it was to be , the arkenstone remained in smaug’s piles ‘til the company of thorin , son of thráin , son of thrór , descended upon the mountain , and with the help of the contracted burglar and hobbit , bilbo baggins , procured the arkenstone from the dragon , a creature later slain by one of the race of men . the arkenstone exchanged hands ‘til , at the death of thorin , it was placed upon his breast by bard , in a display of good will to the dwarrows , who were now to be the allies of the men of dale henceforth under the reign of king dáin , son of náin , son of grór , and king bard , descendant of girion . no longer would the arkenstone crown a dwarf on the throne , for it was decided , in honor of his great sacrifice and the mourning of the cost of his quest , that the jewel would be buried with thorin , so that he would be crowned evermore .

the arkenstone , though called by the dwarrows to be the heart of the mountain , may never have been so , and instead be a silmaril forged by fëanor and hence lost to the depths of the earth with the undoing of maedhros , son of fëanor , who flung himself into a gaping chasm .

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚒𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟼𝟻𝟷 - 𝟼���𝟹 ) the choice of arkenstone is significant , since in other writings tolkien was making at the same time he was using a variant of the same name as a term for the silmarils themselves , forging a link between the jewels of fëanor and the arkenstone of [ thrór ] in the legendarium [ . . . ] the idea that the arkenstone could be a silmaril , or was at least somehow linked to the silmarils in tolkien’s mind , has additional support from the philosophical roots of the word .

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚒𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟼𝟻𝟺 ) like the silmarils in the main branch of the legendarium , and unlike the one ring in the sequel , the arkenstone inspires greed but is not itself malicious in any way [ . . . ]

though many will point to the finality of one statement that the silmarils could not be found again unless the world was broken and re - made anew :

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚒𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟼𝟻𝟽 ) tolkien had in fact at that point changed his mind four times in the previous fifteen years about the holy jewels’ fate , all in a series of unpublished works that remained in flux and were each to be replaced by a new version of the story [ . . . ] it is thus more than possible that tolkien was playing in the hobbit with the idea of having one of fëanor’s wondrous jewels re - appear , no doubt the one that had been thrown into a fiery chasm , and lost deep within the earth ————— which is , after all , exactly where the dwarrows find the arkenstone , buried at the roots of an extinct volcano .

the silmarils may inspire greed , but they merely reflect the heart of the one who possesses them , and are no source of evil , nor do they hold magical sway beyond the manner with which all covet them for their great beauty⁴ . the silmaril named the ❝ arkenstone ❞ by the dwarrows did not encourage the madness in either thrór nor thorin⁵ . while they both desired the jewel greatly , it was because of the power that they themselves attributed to it , and not anything that the arkenstone itself was able to exact . the light of the valinor , which the arkenstone encases , is a good and beauteous light , and it is only the imperfect heart that all carry and that drives those who see the silmarils to commit treacherous deeds for them that taints the jewels⁶ . in the end , it was the corruption of the dwarf ring given to the line of durin long ago that wholly cursed them with a dark greed and a darker madness . as said by balin , the arkenstone would not have stayed thorin’s madness , nor prevented it , but exacerbated it by its presence .

𝐅𝐎𝐎𝐓𝐍𝐎𝐓𝐄𝐒 .

¹ 𝚙𝚎𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝚓𝚊𝚌𝚔𝚜𝚘𝚗 , 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 ( 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚋𝚊𝚝𝚝𝚕𝚎 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚏𝚒𝚟𝚎 𝚊𝚛𝚖𝚒𝚎𝚜 ) , 𝚋𝚊𝚕𝚒𝚗 : ❝ that stone crowns all . it’s the summit of this great wealth , bestowing power upon he who bears it . would it stay his madness ? no , laddie . i fear it would make him worse . perhaps it is best it remains lost . ❞

² fëanor , having been supposedly taught by aulë ( mahal ) , and with the dwarrows being the creation of aulë , leads to the belief that they would be able to facet the otherwise impervious silmaril , whilst any other race would not be able to do so , no matter any secrets learnt . however , this interpreation will adhere to the film portrayal of the arkenstone , which has it as smooth .

³ one such inscription can be seen in the film , read as : herein lies the seventh kingdom of durin’s folk . may the heart of the mountain unite all dwarrows in defense of this home .

⁴ in the film , smaug tells bilbo that the arkenstone shall corrupt thorin’s heart and thus destroy him and drive him mad . the dragon was , of course , lying , attempting to sway the loyalties of bilbo’s heart , as it had been trying to for most of the conversation , whether that scheme was lying about the arkenstone’s power , or that the dwarrows valued bilbo so little . in truth , as smaug’s powers of cleverness knew , thorin would be the one to drive himself mad over the stone , and not the stone itself .

⁵ nor did the arkenstone inspire any such madness or lust within bilbo baggins , who was in possession of the jewel for quite some time , and did not feel any such inclinations past how heavy it seemed to be in his hold :

𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚘𝚋𝚋𝚒𝚝 , 𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚛𝚝𝚎𝚎𝚗 , 𝚗𝚘𝚝 𝚊𝚝 𝚑𝚘𝚖𝚎 ( 𝚙𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝟸𝟹𝟽 ) his small hand would not close about it , for it was a large and heavy gem ; but he lifted it , shut his eyes , and put it in his deepest pocket .

⁶ it is true that those with evil intent ( forgoing the idea that mortals cannot touch silmarils , which shall not be considered for this , as it does not fit no matter how holy they may be, and appears to be an inconsistent particular ) cannot touch the silmarils lest they be burned . one must consider that bilbo baggins had no evil intent , and thus was able to carry the stone . neither did bard , who also held onto the stone for a period of time . evil intent , however , is a manner of perception ; was thrór truly being evil by his greed , or disagreeing on the payment of goods for the elves , should he believe himself in the right ? was thorin , up to a certain point in the delirium of the dragon - sickness , behaving evilly as he protected the mountain and what lay inside of it against the perceived threats ? 'til later deeds , he may have been able to hold the arkenstone , as thrór had , but his treatment of bilbo baggins after the hobbit’s betrayal would have rendered him unable to touch the arkenstone , for that was a bad , unfair act in regards to the feelings that they shared for each other ( should thorin have lived , he would not have been able to touch the arkenstone until he had made amends with bilbo and otherwise honored his word . it is possible that he may have never been able to ever touch the arkenstone at all ) .

#interpretation .#the legends of the mountain - son .#this is probably quite controversial considering how discussions seem#rather undecided regarding the topic ;#but this is the belief that will be adhered to for this portrayal .

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Young Thrór (And one Grór) sketchdump

#some grandpa thrór action yeeee#maybe I'll use this tag for shirtless thrór drawings lmaoo#my art#thrór the hobbit#thrór#thrór king under the mountain#the hobbit#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#durin's folk#the lord of the rings#longbeards#the royal line of durin#the line of durin#erebor#the iron hills#grór lord of the iron hills#dwarrowdam#sketch

939 notes

·

View notes

Text

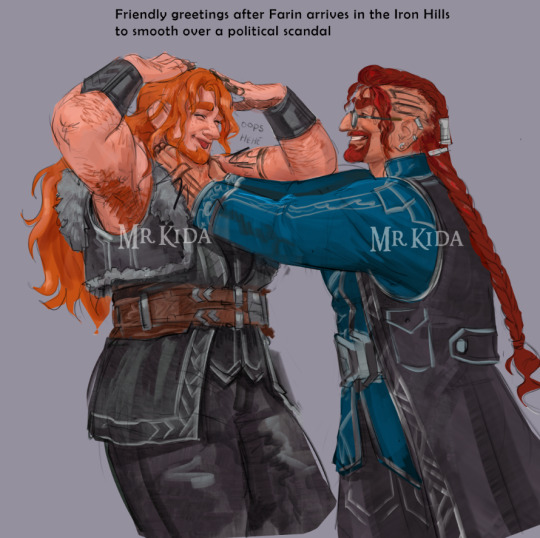

Doodles of Prince Farin, son of Borin

#my art#the hobbit#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#the lord of the rings#durin's folk#longbeards#Farin#Prince Farin#farin son of borin#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#erebor#the line of durin#the royal line of durin#also#cw strangling#i guesss hahah#tolkien dwarves#dwarves of ered mithrin#dwarves of erebor#dwarrowdam#gror

473 notes

·

View notes

Text

The children of the Dáin I, the crown prince of Durin's Folk.

The eldest, Thrór, the future king under the mountain.

The younger, Frór, destined to die.

And the youngest, Grór, the future lord of the iron Hills

#baby dwarves#dwarfling#the hobbit#my art#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#the lord of the rings#durin's folk#longbeards#the royal line of durin#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#frór#thrór#thrór king under the mountain#durin siblings#the OG sibling trio yeee#dwarves of ered mithrin#the war of dwarves and dragons#baby durins#dáin I#gror

935 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thrór and Grór

#the hobbit#my art#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#the lord of the rings#durin's folk#dwarrowdam#longbeards#thrór#thrór king under the mountain#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#gror#thror#the line of durin#the royal line of durin

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grór, Lord of The Iron Hills

#double upload today because when Im in a bad mood I draw lmao#SO HERE'S GRONKLE#my art#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#the iron hills#the hobbit#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#the lord of the rings#durin's folk#dwarrowdam#longbeards#the royal line of durin#character design#lady dwarf

498 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iron Hills drip

#the hobbit#my art#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#the lord of the rings#durin's folk#dwarrowdam#longbeards#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#gror#the iron hills#tolkien dwarves#cw blood#tw blood#the royal line of durin#the line of durin

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being employed as a servant in Grór's court is not easy

#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#the iron hills#durin's folk#the royal line of durin#sapphic#sorta#hahahaha#tolkien#my art#the hobbit#the lord of the rings#lotr#dwarrowdam#tolkien dwarves#the longbeards#tolkien fanart

537 notes

·

View notes

Text

After their home in the Grey Mountains had been lost, the newly crowned king Thrór opted to resettle Erebor.

The second in line, Grór, traveled east to found another settlement in the Iron Hills, becoming a Lord of this realm while still being a child.

#my art#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#the iron hills#durin's folk#the line of durin#the royal line of durin#dwarves of ered mithrin#reminder Grór was canonically TINY while settling the iron hills#Grór was 26 when the grey mountains fell#TINYY#I think they are the youngest dwarven lord we know about?? I might be wrong though#the hobbit#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#the lord of the rings#longbeards#the war of dwarves and dragons#dwarfling#sorta

407 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grór, youngest child of the crown prince Dáin I.

#my art#the line of durin#the royal line of durin#ered mithrin#the gray mountains#grór#grór lord of the iron hills#dwarves of ered mithrin#the war of dwarves and dragons#dwarfling#baby dwarves#baby durins#TINNYY DWORF#tolkien#lotr#middle earth#the lord of the rings#the hobbit#the rings of power#trop#the silmarillion#durin's folk#the longbeards

592 notes

·

View notes

Text

cw: blood, violence

The attempted assassination of Grór, the young Lord of the Iron Hills

#cw: blood#cw violence#tw blood#tw violence#my art#the hobbit#tolkien#lotr#dwarves#the lord of the rings#durin's folk#dwarrowdam#longbeards#the iron hills#grór lord of the iron hills#the line of durin#the royal line of durin#tolkien dwarves#grór

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iron Hills booba (featuring Náin)

#bonus#my art#náin#the iron hills#sketch#the line of grór#royal line of durin#tolkien dwarves#the hobbit#tolkien#lotr#the lord of the rings#durin's folk#longbeards#the line of durin#dáin's dad wee

474 notes

·

View notes

Text

The eldest child of king Dáin has always carried a lot of responsibility

#durin siblings#just no the one we're used to#Thrór#Frór#Grór#Thráin#the hobbit#my art#tolkien#the hobbit fanart#lotr#dwarves#durin's folk#the royal line of durin#grór lord of the iron hills#erebor#king under the mountain#Frór isn't in the timeskip one since they... you know.. got killed and all that#dwarves of ered mithrin#NAP TIME#sketch#the lord of the rings

373 notes

·

View notes