#lit crit

Photo

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

I know the average reading comprehension on this site is zero but I'm different. I'm applying wildly inappropriate analysis lenses to popcorn media. I'm doing a queer theory reading of Horus Heresy novels. Now I'm doing feminist analysis of Warhammer 40k canon. Now I'm applying Marxist analysis to The Outsiders. Time for a historical analysis of The Locked Tomb. A post-colonial reading of the entirety of Doctor Who. A psychological anlaysis of Twilight. On the horseshoe scale of reading comprehension I'm at "so much reading comprehension that it loops back around to not understanding books at all actually". You can't stop me. I'm literary analysis Georg

#I paid many thousands of dollars for this degree#and by god i will use it#literature#Literary analysis#Literature analysis#Media analysis#literary criticism#reading#reading comprehension#meta analysis#literature major#literature memes#lit crit#media literacy

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

learning to historicise, recognising shoddy scholarship, paying attention to the actors involved and their class interests, the political economy of the production of any art or media are all part of media literacy but unfortunately doing close readings of classic literature will not teach you this. the literature fandom on this website is getting engineer disease where you start thinking other fields and modes of criticism don't have any expertise bc you've surrounded yourself with other people swallowing your hype.

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

Errors, “Errors,” and Animorphs

So in a different post I ranted about how a tiny non-distracting unfixable difference between two shirts is not an error in Jurassic Park. IMHO, a continuity gap is only an error if:

It draws attention to itself and distracts the audience

It could’ve been fixed pretty easily in-story

It makes character, plot, or setting nonsensical

Animorphs has continuity gaps of its own. And I have opinions about what we readers do and do not count as “error.” First, an example that’s clearly an error:

I wondered if Tobias had heard my thought. I concentrated. Tobias, can you hear me?

«Yeah,» he said, «I hear you.»

“Did you hear my thoughts before that?” I asked.

«No, I don’t think it works that way. You have to think at me for me to hear.»

—#1: The Invasion

Tobias briefly hearing Jake thought-speak in #1 breaks the rules of the setting; several other books (#2, #23, #31, #33, #46) clearly state that it’s impossible to thought-speak if one is human and not in morph. It’s an easy fix; the re-releases and audiobooks delete this moment, and the graphic novel makes Tobias unable to hear Jake. It distracts the audience; I’ve gotten 5 or 6 separate asks over the years of people going “I was rereading #1, and the weirdest thing...” It’s an error. I can’t say what happened behind the scenes — K.A. Applegate toyed with a thread that was later dropped, or decided to introduce a limitation for plot fuel at a later time. But it’s an error.

Second, an example that I don’t think counts as an error:

I returned to my life, feeling strange and out of place. That night Jake came over. We went outside.

"I tried morphing the Tyrannosaurus," he said. "Nothing. Didn't work."

"You could ask Ax. He may know why."

Jake laughed. "Yeah, but even if he explains it, I still won't understand it."

—MM2: In the Time of the Dinosaurs [Cassie’s narration]

The kids not being able to morph dinosaurs outside of the Cretaceous Era makes a lot of sense in context. The whole book series would fundamentally change if they could use T. rex — that would become heavily a favored morph for many of them. It kicks off all kinds of plot questions that demand answers: Where do the controllers think the “andalite bandits” got dino DNA? What anti-dinosaur measures would they be forced to adopt? Would the Animorphs’ whole strategy change around having those morphs? How would Rachel feel about everyone but Tobias suddenly having a much stronger morph than her? Would they even bother with contemporary animal morphs afterward?

If the kids are morphing dinosaurs all the time after ~#18, then the series loses a lot of its uniqueness. Applegate has said that most of the inspiration for the series was about trying to help kids understand what it would really be like to be inside an animal mind, with as many animals as possible. That’s part of why so many of the plots hinge on giving the Animorphs an excuse to learn a new morph (e.g. #4, #17, #27, #47, #52) so that we can experience the coolness right along with them. That’s why the war is explicitly about fighting for Earth, nonhumans and all (#7, #23, #53). If it’s not a menagerie of six different critters — including one immigrant from space — rolling up to battle, then it’s not Animorphs. No, it makes no dang sense that sario rip morphs stop working once the rip gets unripped. But the series acknowledges it, and it allows us both to have a unique animal-based story (dinosaurs! Heckin dinosaurs!) without ruining its own premise.

Third, one that I find fascinating because it’s kind of right on the margin:

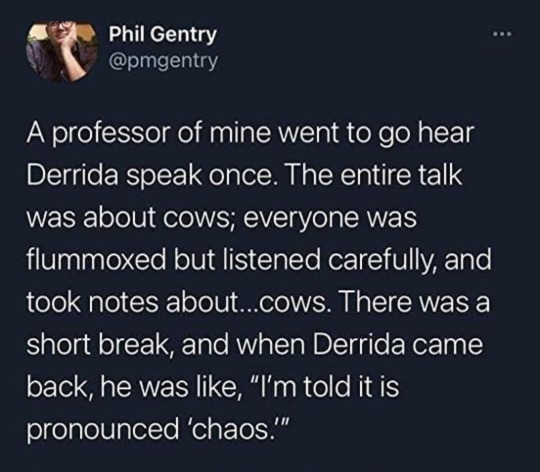

"What I don't get is why I have to be a girl wolf," Marco grumbled.

"We had one male and one female," Cassie explained for the tenth time. "If two of us morphed into the male, we'd have two males. Two male wolves might decide they had to fight for dominance."

"I could control it," Marco said.

"Marco, you and Jake already fight for dominance, and you're just ordinary guys," Rachel pointed out.

—#3: The Encounter

Later, Tobias’s narration uses the word “alpha” to describe Jake’s morphed behavior — howling and peeing to mark territory, challenging another wolf pack to protect his own.

There is scientific consensus right now, as of the 2020s, that the term “alpha” is an inaccurate descriptor of pack-lead behavior, and that dominance fights between adult males are almost nonexistent. That although wolves usually run in a phalanx-like shape with one middle-aged male and female at the point, this isn’t the result of dominance fights but rather an effort to have the physically strongest wolves absorb blows from rogue prey animals or rival predators. That the dominance fights observed in captive wolves in the 1970s were the result of an ecology error, putting wolves from rival packs into single enclosures. Fox (1972, 1973) gave a reasonably accurate description of how wolves behave if you put a bunch of adult strangers in a zoo together: the young adult males fight, the winner of that fight wins first access to food, and the mate of the winner gets the most resources for her puppies.

However, time rolls forward, and advances like hidden cameras (and the resurgence of wild wolf populations) allow us to watch wolves without needing to capture them first. Mech (1999) follows some such wolves around, and quickly realizes that dominance and submission aren’t nearly as important among wolves who chose to make a pack. Stahler et al. (2002) figure out a better way to introduce stranger wolves in captivity, and get full cooperation among young adult males. Nowadays drones and radio collars get 1000s of times the wolf data Fox had to work with, and reveal intense cooperation with little more than play-fighting among puppies.

The Encounter comes out 1997. Mech publishes the first big takedown of the alpha concept 1999.

Did an error occur anywhere in this process?

No, in that Applegate presumably doesn’t own a Time Matrix and published a book based on the scientific consensus at the time about how wolf social dynamics worked.

Yes, in that the error is pretty distracting — I get drawn up short by it every time I reread #3, and I know others have too.

No, in that the error was corrected in the graphic novel adaptation.

Yes, in that the error is still present in the audiobook, and Michael Crouch delivers the moment about Jake being backed into a dominance fight with all of Tobias’s exasperated humor.

No, in that the error allows for some character moments, both silly (Jake peeing on trees) and sweet (Jake being ready to take on an entire rival pack alone, over a rabbit he doesn’t want).

Yes, in that the error takes away from one of the series’ most fundamental purposes, to educate kids about animals.

Anyway, books are great, science is imperfect, and I think the more we all engage with amateur criticism the more we’re all going to learn about what counts as an error in fiction writing with inspiration in scientific reality.

#animorphs#animorphs meta#continuity errors#retcons#fandom#lit crit#3#1#mm2#there's a related question: if the third graphic novel is also set in 1997#then how does cassie know about the alpha wolf hypothesis being debunked in 1999?#but again#answering that question would make the book worse not better#so i don't worry about it

479 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The scribes of the Middle Ages wrote predominantly in iron gall ink, the product of an elegant four-ingredient recipe. Certain wasps implant their eggs in the leaves and smaller branches of oak trees. This process produces in the tree a gall: a lump of tannin-rich material in which the larvae grow. When ground and boiled in water with a sprinkle of iron sulfate and some gum of arabic, the mixture of insect and vegetable chemicals in the gall with the mineral of the iron forms a pigment stable enough to carry around in a little flagon and acid enough to stain parchment for a few millennia.

"It’s not hard to find the ingredients, as long as you know what to look for. To learn about oak gall, an aspiring European ink maker would consult a botanical guide called a herbal. Just as useful to a nun in her walled herb garden, a commercial pharmacist, and a parent in a medical emergency, the herbal was in high demand but, until the advent of the printing press, expensive to produce. Publishers in the earliest years of mechanical printing activated this latent market, and herbals became one of the first popular printed nonfiction genres. These pre-Linnaean textbooks established graphic design protocols that have shaped the way curious minds learn and process plant science ever since."

"Aloe, Basil, Cash Crop," Jo Livingstone

Perceptions of Medieval Manuscripts, Elaine Treharne

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

i LOVE it when comedy/horror films build up tension just to destroy it dramatically, intentionally confusing the audience with many different tones; even though they aren't alike at all, i think nerdy prudes must die (NPMD) and many radio tv solutions (RTVS) streams/bits are masterclasses at this sort of form!!!

in NPMD, i mostly see richie's 'arc' as being the center point of the tension. he announces to the audience that he's dead, but this idea is quickly eclipsed as the show goes on. richie finds friends and his place once jagerman is 'gone', and the tone begins to feel eerily comfortable. when he says he loves being alive, all this anxious positivity bursts as the audience remembers his fate, and this creates a really unique atmosphere of both comedy and despair.

i could cite many RTVS bits here, but i'll just talk about breaking bad vr (BBVRAI) since it was so recent. everything RTVS does online, on and off stream, is part of their performance (duh). all of the producers/contributors of BBVRAI pushed a very obscured narrative about what the stream would be up to and on the day of the stream. in building this hype and attracting this attention, they equally built tension, and even when the stream started, they continued to build this heightened emotion until the stream title rolled. the title screen, for lack of a better term, "popped" the tension, eliciting mixed tones of comedy, disappointment/excitement, confusion, etc.

this is an interesting choice by the production teams of both NPMD and BBVRAI in that it achieves generally the same result; the audience's emotions are built to be disrupted. this disruption is intentional, and it is meant to confuse/shock/hurt/surprise/etc. it works SO WELL in horror and comedy because those emotions i listed are critical to the genres.

if you read this far, thanks :) my tumblr is kind of turning into my springboard for all the drafty analytical thoughts my little english major brain has :)

#literary analysis#literary criticism#lit crit#short essay#writing#nerdy prudes must die#npmd#starkid#starkid npmd#starkid nerdy prudes must die#radio tv solutions#rtvs#bbvrai#breaking bad vr but the ai is self aware#richie lipschitz#long post#wayneradiotv

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

@fierceawakening -- I think wrt the Ursula K. Le Guin quote, you might be getting hung up on some of her wording and missing what she's actually trying to convey?

The thing she's trying to get across is not "people shouldn't take joy in writing things other people have written before".

The thing she's trying to say is "it's really fucking annoying to be having a literary conversation where you are saying interesting things, and then to watch someone else get lauded for saying the most basic, baby-level version of those things because they've never taken part in your conversation."

Like, the example I'd give if I was talking about the phenomenon would be The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. (A book which I read and liked.)

In 2005, when The Book Thief came out, critics were salivating over it because it was a literary novel with Death as a Major Sympathetic Character. They thought it was fascinating that Death didn't quite understand humans but told their stories anyway! ..... and like, the thing is, is that they're not wrong? But also, SF/F authors had been using the conceit of The Grim Reaper As A Major (Sympathetic) Character since bare minimum the 'late 80s at that point, and many influential sf/f authors even characterized Death in a similar way.

I know you don't like Pratchett, but he'd been writing this stuff since the late 80s. Gaiman and Piers Anthony had been doing a similar schtick for a similar amount of time. They were already having a conversation about what Death might look like as a sympathetic major character. Some folks had more to add to that conversation than others (Anthony in particular wasn't saying anything particuarly mature about it...), but they were already having a conversation. And the critics mostly ignored that conversation, because it was happening in SF/F and therefore was intellectually bankrupt, right? RIGHT????

None of those authors could have or would have written The Book Thief, and that story deserves the critical acclaim it got. It's a damn good book. Parts of it will haunt me forever. ...But it deserved to get critical acclaim for how it added to the conversation. And at the time, critics were treating it like it was the start of the literary conversation of Death As A Major Sympathetic Character. It wasn't, by a long shot.

That's what she's complaining about. That's why she compares it to restaurant critics effusively praising buttered toast. It's not that people shouldn't be able to find innocent joy in writing Babby's First SF/F; it's that authors and critics who knee-jerk rejected SF/F were treating "literary" stories that were effectively Babby's First SF/F like they were starting brand new literary conversations, with the kind of innocent glee you'd expect from someone who'd just invented an entire genre.

She's salty and tired of having her work taken less seriously by people who don't know anything about the conversation folks in her field were already having.

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heavy Lies the Crown: Rhysand, greatness, and the pressures of power

Or: the librarian’s daughter, former playwright, licensed counselor mashup of my nightmares dreams because I am vast, I contain multitudes.

No content warnings and no real HOFAS spoilers, I don't think, other than that he's in it but I feel like you know that by now. Spoilers for Breaking Bad (lol).

---

In working on my current fic (on ao3 here!) I've been thinking a lot about Rhysand and how he really goes off the rails in ACOSF and HOFAS. It's easy to chalk it up to poor writing, but I like the challenge of trying to make it make sense. What are Rhys’ motivations, truly? What would explain the vast array of heinous shit he does the text tells us is justified?

Rhys is shown over and over to be quite Machiavellian ('ends justify the means' dude, who was maybe writing satire). It's easy to list the times he shows this. The 50 year Velaris hostage situation. The bargain UTM with Feyre. The Weaver's cottage. Stealing the Book from Tarquin. CLARE BEDDOR. Infiltrating people's minds. Torture. Assassination. Allying with Kier. Concealing his wife's medical information. Being an ass to people in general. According to Mr. Machiavelli, any action is warranted if it the goal it achieves is morally important enough.

It seems like Rhys can justify anything to himself if he believes it will serve the greatest good at the end of the day. He does so many things with the air of “it’s for your own good” or “you’ll understand why one day” but that day never.. comes? Not yet anyway, which begs the question: is he that unself-aware, or is there a longer game he’s playing that all of these minor skirmishes are leading up to? What if he knows what's coming? And what kind of cause or threat would feel so great he could justify everything he does up to this point?

Okay I'm gonna talk about Aristotelean literary structure, please don't leave me.

The idea of a tragic hero is a character whose downfall is inevitable but who fights against it anyway. Hamlet is a classic example of a tragic hero, Oedipus being the de facto first, Walter White from Breaking Bad a more modern version. We see Walt learn he’s going to die in the first episode, in the middle he does a bunch of stuff to prevent his physical death (cancer) and metaphorical death (failure/obscurity), and then both his body and reputation die in the last episode as a direct result of his attempts to avoid fate. It’s blissful Aristotelean symmetry. *chef’s kiss*

Every tragic hero has hamartia, more commonly known as a ‘fatal flaw’. In Hamlet, his fatal flaw is procrastination, and his delays create space for all kinds of the fuck shit he was trying to prevent. It’s important to note that hamartia is by design a neutral term - not so much a flaw, but a trait, motivation, or decision that sets off the chain of events the character is trying to avoid. Tragedies have occurred equally from too much love as too much hate, and doing nothing is just as much a decision as doing something. The word itself comes from the Greek for ‘to miss the mark’. To try and fail, the backbone of tragedy.

One of the most common hamartia is hubris, a modern synonym for arrogance but which more specifically means an outsized belief in one’s ability to affect and control the future. Well-known tragic heroes taken down by hubris include our boy Walter White, Tony Soprano, Viktor Frankenstein, Achilles, Jay Gatsby, Kendall from Succession. It exists in real life, too: Lance Armstrong is a perfect example of a modern tragic hero brought down by hubris. And what do all these men have in common? Power, via money, fame, strength, the state, intellect, violence etc.

I’ve been enjoying looking at Rhysand through this tragic hero lens because while it doesn’t really make him more sympathetic, it does make his actions easier to understand logically, which is its own kind of humanization. If Rhysand is aware of a prophesied or fated event sometime in the future and is pulling the cosmic strings now, it must be incredibly important, like annihilation-level important, which is so much pressure.

So he grows to maturity with an understanding that he will one day have to face this intense evil that could completely destroy his world, and it plants in him a hubris. He believes that his immense power grants him a certain amount of influence automatically. And honestly, is he wrong?

And this is where it’s important to think about how power makes people weird. Power gives people a false sense of confidence in their actions and choices, because their status and privilege protect them from so many more consequences. In this way it’s easy to see how someone can get a big ego - no one is stopping me, so I must be doing well! Or: everything is going well for me, so I must be really killing it! I know I feel that way in the first tingles of hypomania, but hypomania is fundamentally a distortion of reality and I believe so is power.

Power not only gives people confidence but also access to make decisions for others. They begin to think they should share the success they’ve found by leading and guiding others to see how great it can be if you do what they say. Just look at one of those cringe 'billionaire morning routine' videos to see what I mean. It’s a very patronizing form of altruism, because the leader genuinely believes they have the people’s interest at heart. And I use the word patronizing intentionally - leaders have often referenced feeling paternal towards their people, Winston Churchill + FDR, 'God the Father'. Power and fatherhood have been linked for a long time. And direct from our girl Wikipedia, "paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy and is intended to promote their own good".

I was talking with a girlfriend of mine recently about how I think some men don’t have the experience of other people depending on them in a significant way until they get married and/or become fathers. Like, afab and femme people learn very early to be considerate of others, to think about how others feel, to act in ways that keep others happy, etc. This plants in us a sense of duty to perform in ways that please others, to smile, to create comfort and provide caretaking in every environment we enter. So by the time we get to marriage and motherhood, we already know how to put others’ needs before our own because we’ve been doing it from the jump.

For men, however, this can be a completely novel experience. And it seems like it's SO HEAVY FOR THEM. George ‘Father of his Country’ Washington just wanted to go back to Virginia the whole time he was President. So many men talk about the pressures of being a provider and their families depending on them in a way women don’t, and I think it’s because for the first time others truly depend on them and they don’t know how to handle it.

In response, they either shove down their emotions as patriarchy demands and have a midlife crisis, or they abdicate that responsibility and go completely absent physically and/or emotionally to continue living for themselves. (Obviously there are good men and dads out there, and bless you if you’re lucky enough to know, have, or be one.)

And this aspect of power feels relevant because from the text it seems like Rhysand is unraveling. Between Feyre, the baby, the Trove, Nesta and being threatened by her power, Koschei, Bryce, the whole High King shit - I think he’s starting to crack under the pressure. And honestly, I’m kind of surprised it didn’t happen before now.

According to Aristotle, the tragic hero must:

Be significant (virtuous/capable/powerful/important etc.)

Be flawed

Suffer a reversal of fortune.

Rhysie boy definitely ticks the first two. I wonder what it would look like to get to three? I don’t think Sarah has the balls, but it’s definitely enhanced my reading experience and given me a lot of interesting things to think about.

Okay that's all I've got. Love ya, see ya soon xx

#prythian university#acotar#acosf#rhys critical#sjm critical#tragic hero#lit crit#i love thinking way too deeply about things

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be honest, I feel like some people are expecting way too much out of tumblr level essays. Just because someone is a linguistics, philology, literature or cultural anthropology student in their real life, it doesn't mean they should be expected to produce academia level essays on their free time for fun.

I promise you, those students and graduates are probably brilliant and far more capable of nuance that you are giving them credit for. But, let's be honest, no one writes the 10 to 20 pages with correct citations you are expecting them to for fun, unpaid and in their spare time.

Academics already work so much without compensation. So you can either pay us to write you the 15 pages of nuanced critic you are expecting of us, or stop expecting it and let us have as much oversimplified fun as the next guy.

Also, mind you, whatever essay we write here, we can't reuse for other purposes without risking a self-plagiarism issue.

So, yes, I can write a nuanced essay on the many ways Greek mythology retellings reflect on societal change and (pop) feminism. I can. And probably someday I actually will. But here all I will say about it is:

Demeter being the villain of the story in retellings reflects more on current mother-related trauma and Christian purity culture than it does the original text. And, even though that is not by any means an incorrect way to rewrite a story (because no creative endeavor is inherently wrong), the trend is getting tiring and starting to reflect heavily on the current cultural perception of the story.

If you want nuanced ideas on how vampires reflect societal changes better than almost any other monster, you can read my BA Tesis. For nuanced takes on how horror movies are linked to inmaterial human heritage through folklore and how horror movies aimed are children are starting to occupy the space left behind by the traditional fairytale after those had their teeth filled, you can read my Master's Tesis (if you speak Spanish, because unless you work for an Academic publication, I am NOT translating it for you)

#literature#lit crit#cultural anthropology#tumblr essays#greek mythology#horror movies#linguistics#philology#for the record: i am a cultural anthropologist

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lmao imagine fundamentally misunderstanding poetry so much that you write THIS about Mary Oliver - somebody now regarded as one of the greatest poets in the American literary canon.

“Poetry shouldn’t be helpful or life-changing.” My man. Have you ever actually read a poem that you enjoyed? Are you okay???

#poetry#mary oliver#lit crit#‘poetry can’t work as self-help’ is truly an incredible line from a literary critic#uhhhh i think that’s the point of poetry#the nyt book section sucks. in other news water is wet the sky is blue

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Jane and Frankenstein

In honor of Spooky Month and the imminent arrival of Mary Jane Day, I have done the scariest thing imaginable, returned to tumblr dot com to write a meta/analysis post.

[image description: images side by side of the top of the Mary Jane poster, showing Mary looking down sewing Jacob, next to the 1831 edition front panel illustration of Frankenstein, showing Victor looking down on his creature in horror]

This is a mostly informal attempt to collect my thoughts on the fact that Neji’s little spooktacular, in addition to being a very pointed exploration, as all of his plays are, of art and theater, the school, himself and his classmates (without their permission, the menace) and just, a lot of fun, is perhaps one of the best piece of Frankenstein related media I have EVER seen in relation to the original novel.

This is pulling a lot of things from the Stage Script rather than the in game version, which summarizes a lot of the things I'm mentioning specifically. You can find the full Stage Script in the game menu, or

[ here ]

because I love this play so much that I needed a searchable version.

Caveat Emptor here is that it’s been a long time since I’ve read the novel in its entirety. If this game gets me to read it again, I may have to revamp things. But again, largely informal. But very long, somehow.

Oooops.

If you're curious about anything in here and want to expand on it more, or hear my thoughts on it, please feel free to reblog, send an ask, or message. Or ask me elsewhere if we're already connected there. There's a lot I glossed over, especially at the end of this. I have a lot to say, and if we're back to writing metas on tumblr dot com the chances of stopping at one are slim.

Mary as Frankenstein, Mary as Mother

Mary’s name is acting as several allusions at once. I mean, there are at least 3 Mary’s in the bible one could point to - Mary, Mother of Jesus is absolutely at play. But Lazarus’s sister is also a Mary. And while technically Mary Magdalene is often misrepresented and amalgamated with other characters in retellings, the idea of “purifying” her has canon precedent - having had seven demons driven out of her.

Of course, Neji’s twisting all of it, in his Neji way.

(Interestingly enough, these are the Three Marys of the Quem Quaeritis - widely considered a point of "rebirth" of theatre in Europe during the middle ages.)

But Mary is also the name of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of Frankenstein. And this, this is a Frankenstein story. It is, in fact, a beautiful inversion of so much about the book that gets left out in most far more serious attempts at a Frankenstein story.

The original book is about motherhood and its inversion. Much could be said about when during her life she wrote it, or her own mother’s death shortly after she was born, or any number of things that have been hashed and rehashed a thousand times from AP English to the ivoriest of towers. But, fan of Death of the Author that I am, I posit you don’t need any of that to see in the text.

Victor creates a person with science, rather than by ‘nature’. It is an unnatural birth. And Victor is just about the shittiest possible parent. The Creature spends a good deal of time explaining to him, when they meet up again, that Victor is his father, and that he was literally abandoned as a newborn, and maybe that was kind of the worst possible thing he could have done. It’s not a mantle Victor has any desire to take up, the role of a parent. He wanted to create life, but he didn’t want to be a parent. But that’s what it means to create life.

By gender swapping the role, you’re already inverting the inversion - but Mary’s creation is no more “natural” than Victors. But it is different. Neji, ever witch-coded himself, has Mary put one of her own hairs into every doll. It’s returning the shared body to the act of bringing these creations into being.

But even without that. Mary considers herself a mother. She considers herself a mother despite having no memory of one herself - Mary knows lots of things she shouldn’t, and doesn’t know many things she should. But she calls herself a mother. Even before any of the dolls move, she is their mother. A motherhood she wants to desperately share with others. She considers the act of selling a doll a kind of ‘adoption’. These are her children. And they know it. It’s stitched into every stitch in their doll bodies. They know Mary is their mother. And they know she loves them.

[image description: screenshot of Mary in her workshop. The text shows Mary's line saying "I'm back, dear dolls. Mommy's home."]

The Creature comes to think of Victor as a father - an absentee one at that, and craves that love, a love he is never shown. Mary averts this spectacularly. She creates out of love.

Names

Mary takes great care in naming Jacob, and ends up doing so, though she doesn’t say it, after a biblical pun (Jacob, in the bible, is explicitly named such as a pun on the word “Heel”). But names are important to Mary, and she is sure to give one to Jacob as soon as he’s fully formed, even before she sees him wake up. Victor very particularly does not name his creature. Instead, he tends to throw around insults, many of which are demonic or satanic. When they finally meet again, the Creature says to him “I should have been thy Adam.” Mary averts this mistake, among so many others, spectacularly. Being called by her name is important to her, and she extends that offer to Jacob even before he’s fully “born.” Like a good mother.

[image description: a screenshot showing Fumi and Kai dressed as Mary and Jacob, as seen from the stage with the audience in the background. Kai is saying Jacob's line "I did, Mary. You are Mary Jane. My mother."]

Not only does she give him a nice biblical pun of a first name, she shares her last name with him, again before he’s even more than a doll. That’s her boy, that’s her best friend. That’s her family.

The song here, which is only sung and dance AFTER Mary has given him a name is called "A Friend Without A Name" Almost as if specifically calling attention to this fact. Mary is as much the friend without a name as Jacob, if not more. She is the one that has never heard another voice say her name, where as Jacob is called his before he's even awakened by the Island's magic and Mary's love.

[image description: the screen from just before A Friend Without A Name showing Mary and Jacob's CG of Mary Stitching Jacob.]

Mary as a Good Mother

Some of the weirder moments in the play actually make a lot more sense when you look at them through this light. Jacob randomly saying he hates Mary in a fit of jealousy? It’s because he’s a child. He’s a baby. That’s a baby boy. Mary, herself quite childish, forgetting so much of what’s important, as the Island is known for, reacts incorrectly, but understandably. This is her first friend - and far more of one than the others she thinks she’s made, in terms of mutual respect, compassion, and small acts of kindness. But this level of connection and emotional reciprocation is still new to her. She’s hurt. She runs.

And The Order of Shadow’s duo is quick to tell her that that’s just the nature of ghosts, telling themselves a little joke about how they have been lying to her from the start, and fully intend to stab her in the back, far more than any ghost. Victor’s instinct is to consider his creature a monster, a fiend, a demon. Mary is told by characters positioned as far more knowledgeable about the world than her that he must be exactly that.

And how does Mary react? She refuses to believe it. Even hurt as she was, even with someone who just said this is their entire expertise telling her it’s in his nature to be cruel, Mary refuses to accept it. She still loves him. She makes the right choice. That’s her best friend. That’s her family. That’s a (un)life she brought into this world, and she stands by him. No matter what. She would risk her life to rescue him. She will fight for him.

This is why that scene has to be there. Because she has to be given that temptation, that trial. And she passes spectacularly in a way Victor will not, to the end.

It’s also a thematic explanation for the garbage scene, which is probably there as much to be silly as anything. I mean, it’s also there to show many other things — Mary’s eccentricity is ingenious in its own quirky way — the islanders who hated her, who she didn’t understand, give her the tools to save Jacob and the others — Mary not even considering the same level of violence — it being a moment of empathy between Mary and the islanders who never showed her even a shred of it back — she understands that they couldn’t tell which food was rotten. She sees things from their point of view. And many more besides.

But, from the point of view of Mary as a Mother, Mary succeeding brilliantly where Victor failed… Mary is literally willing to coat herself in filth to rescue Jacob. Parenthood is messy. It involves a lot of gross things. Even Victor's, sanitized of the normal processes and cloaked in science, was made of corpse parts. But the play actually brings back a part of parenthood that Mary had been able to avoid thus far - the mess. Mary, once again, doesn’t hesitate. For Jacob? She’ll do anything.

Jacob is shown love and kindness, and he responds with the same. He has the same unnatural strength as Victor’s creature, but he’s only ever shown using it to rescue himself and others. When Mary asks for a handshake, he replies that he can’t, because such would be an invitation for a duel. And that they should hug, instead. Mary didn’t even know what that was. Far from disgusted by the lack of warmth she feels from his skin, she looks beyond that, to the emotional warmth and connection.

Frankenstein’s creature, famously, lashes out in violence. While Victor views this as his responsibility only in so far as he brought a demon into the world, he doesn’t understand, even when the Creature eloquently explains it, that the Creature was a being who had only known cruelty.

Jacob knows love. He knows kindness. He knows sadness and loneliness and pain. And refuses to engage in any form of touch that could even be considered violence. They hug.

Which is not to say Mary’s creatures can’t kill. But they do only to protect their mother, and only after Mary has risked everything to protect Jacob. They are Mary’s children, not Victor’s. Even their violence is an act of love.

And in another inversion - they are the ones telling Mary to run. Something she does not want to do. She doesn't want to leave them behind. After all, they are her children. She departs from them only at Jacob's literal tug away, and with an apology and a thanks.

[Image description: screenshot of Fumi, dressed as Mary Jane, shown from stage view, with the audience behind, while a Doll's lines "Protect Mommy, let mommy run away." are shown below.]

Boats and Framing

But the parallels are not only in the most famous part of the novel - consider this - Frankenstein, the novel, is written as a series of nesting framing narratives. The bookend narrative, the one we open and close on, is a boat. Most Frankenstein adaptations cut the boat trip frame, but Mary Jane very specifically opens and closes on a boat at sea, and its ending is EXACTLY the reverse of Frankenstein’s. If for some reason you’re this far in and don’t want more spoilers for a 200 year old book, now’s the time to click away, I guess.

The boat is on a course to the Arctic. Victor is on board, telling his story, because his creature has fled there, away from humanity. Victor intends to pursue him endlessly, to kill him, fully aware that he is almost certainly going to die, frozen and alone, in the process. We don’t get to see this happen - the story ends merely with the certainty that this is what is coming. Victor, on a boat, intending to go to the ends of the earth alone to kill the Creature he brought into the world, treating it like some burden and punishment.

[image description: a screenshot from Mary Jane, with the CG of Mary and the Ghosts on the ship, with the summary text overlayed on it reading "Friends together, fun forever."]

How does Mary Jane end? With Mary, and Jacob, and a cast of playful characters — her friends — sailing off for the ends of the world, together, in pursuit of life and happiness - even in death.

Ghost Party ends the play because its a triumph. Neji throwing out Horace’s Ode to Cleopatra in there because he can’t not do silly things like that — but Frankenstein famously contains many references to classics — many made by the Creature himself, who was forced to educate himself via books, lacking a parent to help him.

Mary Jane takes a section of sheer joy out of a poem of complex mixed emotions, and says them repeatedly. This is a party. This is a triumph. Mary leaves on a boat for the ends of the world a success, a good mother, a friend. And a human.

Humanity, Connection, Isolation

The play deconstructs so wonderfully this question of humanity. Mary doesn’t find any joy in it, despite barely understanding it herself - until she is able to use it to help others. The first time in her life she’s been glad to be human - something she only really understands as “needing to eat food” - is when it gives her the ability to save her ghost friends. If that’s what humanity is, the ability to care for others, the ghosts of the chapel, the play is telling us, are far more human.

One of my favorite exchanges in the play is after Charles and Figaro explain to Mary that the corpse parts used to make Jacob were their friends. Mary is not malicious in the least. She has no concept of this act as sacrilege or desecration. She is genuinely childishly innocent in most of what she does. And she can’t understand it.

Mary says “If you can love unmoving corpses so much… How can you not feel for living ghosts...?"

[image description: Mary in front of the burning town. She's saying "How can you not feel for living ghosts...?"]

Charles responds that she must be completely off her rocker. But she’s correct. Mary sees life in front of her, even undead life, and wants to protect it. Even the Islanders, who only ever treated her with distain, who only ever made her miserable — she doesn’t want them to die, even knowing they are already dead.

Outside of Mary, her oddball eccentric self, in this play, the more human someone is, the crueler they are. Figaro and Charles are only ever here to mess with her before dragging her off to be killed. They have no willingness to even try to understand anything outside their world view. The Islanders, who think themselves human, revile Mary, and make up terrible rumors about her.

Both of these groups do so, in part, for similar reasons. Because to have empathy would force a realization on them they cannot bear. The last thing Figaro realizes, before he’s dragged into the most poetic of justices, is that the dolls have SOULS. They are ALIVE. It’s a moment of anger and madness, but it’s a last minute realization that he’s been wrong now that it’s too late. Of course it’s not a revelation he’ll remember. You tend to forget what’s important on Kakuriyo Island.

If Mary averts all of Victor’s mistakes, Charles and Figaro make many of them. Seeing the Creature as a collection of corpses, as demonic, as an abomination against God. Reacting only in anger, in cruelty, in violence. Chasing something they view, wrongly, as an abomination to the ends of the earth, until it kills them. Mary has Victor’s role, but Victor’s actions and outlook are given to the antagonists.

It’s fascinating to me, then, that there are two of them. In the version of the play that gets performed, they’re twins - doubles. Two halves of one whole, who egg each other along in their cruelty. But they also exist to show that even these two are capable of empathy and connection. They do in fact understand the thing they tease Mary with. They have the ability and understanding to extend that to Ghosts, or to Mary. They simply refuse to. Figaro really does love his brother - his grief at his death is genuine. It’s a clever way to show that.

In the book, Victor is extremely isolated, by his own choice. He withdraws from everyone in order to work on his creature, and after he runs from it, he keeps to himself just as much, now blaming the idea that he can tell no one what he’s done. Even when he’s surrounded by family, he is utterly alone. By choice. The Creature eventually lashes out and kills the woman Victor intended to marry. In Victor’s mind, he cares about this girl, but it is not in his actions. Like much else, she exists more as a creation of Victors mind than something in the world for him to interact with and care about. Until she dies. Then he’s furious. And decides to spend the rest of his life chasing down the Creature to kill him for it.

This contradiction in Victor has always read as intentional to me. The book is calling out his hypocrisy here. He doesn’t actually desire connection - the connection his Creature eloquently explains his longing for. But if it is denied him, he acts like he’s been affronted, painted with a shallow layer of sanctimoniousness or justice. Murder is bad, of course, and the Creature shouldn’t have killed an innocent young woman to get at Victor, of course. But the discrepancy between the way Victor reacts to her in death and the way he does when she’s alive is intentional.

Victor has every chance for human connection. Time and time and time again he’s given that chance and refuses it. Even to the very end, on that boat. He could stay with the crew. Sail back home. Let it go. The Creature has run away from humanity which it has come to despise as much as its absentee father disdained it. There is no need to keep chasing. But Victor cannot let it go.

The Creature longs for connection and is denied it. Victor disdains and refuses it, even when it’s available to him.

Mary as The Creature

Contrast this with Mary — It is Mary, rather than Jacob, that is in the Creature’s situation here. Mary is constantly chasing connection. Constantly trying to find something to reflect humanity (compassion, life, emotions — rather than the matter of blood and flesh that Figaro and Charles always talk about it as) back at her. And she can’t get it. She, like the Creature, hides in the bushes and watches it from afar. She, like the Creature, chases after it only for people to run away, to treat her with cruelty. Mary is Frankenstein, but she is also a reflection of the Creature. She is both in one, in this sense.

[image description: screenshot of summary text over the church and figures of the church ghosts. it reads "The friendless Mary dreamily watched the ghosts as they sang a happy song.]

Her costume specifically makes her look nearly as much the doll as the ones she makes - in the world of the story, because she's sewing both - but thematically, it ties her to them not only as their mother, but as a reflection of the Creature, herself.

Like the Creature, Mary is an odd mix of naivety and childishness, with startling gaps in her knowledge, and extreme skill and adult abilities. She knows what she knows well. Like the Creature, Mary has no memory of kindness, of family, of parents. She has only ever seen it in the way the Islanders interact with each other. She is the Creature here - raising herself, learning of the world through watching it, being reviled for every attempt she makes to reach out.

One thing the Creature explains to Victor is that he didn’t even understand, at the time, why he was being treated this way. He had no awareness of his own nature and what he looked like in the eyes of others. Only that they ran in fear and chased him away, and reacted with violence.

Mary Jane inverts this. Mary is human, but the humans around her are something she cannot understand. Like the Creature, Mary doesn’t understand why people react this way. The book expects you to come to the same conclusion as the play - the fault lies not with the Creature anymore more than it does with Mary, at this point. It is those around him, those around her, that are at fault, that are a thing neither can understand. Human’s are cruel. Ghosts who think they’re humans are cruel. It is a disconnect between themselves and the world around them they don’t understand, and desperately try to bridge over and over.

Even Mary, as quirky and childlike as she is, is on the verge of giving up, of being consumed by the Lonely Darkness. We don't know what her fate would have been if the Order of Shadows had not come. Victor's Creature, far more morose than Mary, gives up on connection, as well. He is denied the most basic of needs, and eventually, he learns the violence and hatred being directed at him, and, newborn that he is, lashes out.

But, ultimately, companionship and connection are the Creature’s goals, and it is that that he requests of Victor, who refuses to provide it himself. Make for me a mate. Mary is the Creature, and she is Frankenstein. She makes a friend for herself. Her motivation in creating Jacob is not science, it is not in defiance of death or God — very pointedly — it is out of loneliness - the same motivation that the Creature gives for his desire that Victor make him another like him. And when Mary does so, she’s a good mother, and a good friend.

Religion

Frankenstein’s full title is Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus - it is about forming people, but it is also about stealing fire from the Gods. The question of if creating life out of death the way Victor does is an affront to God is something that Victor himself thinks about, but the book is much more interested in exploring it as the way characters view it. Victor punishes himself, it is not the Divine that punishes him. The Divine acts not as a force, but as an idea. One that both Victor and the Creature end up grappling with and trying to find their place within.

So that Mary herself seemingly has no concept of it, is fascinating. She goes to watch a chapel every night, but I don’t know she knows what a chapel even is. She mentions God once herself, saying that the smell of the garbage would be enough to affect even God, but she also talks to the Moon as a companion and a friend. Her worldview is uniquely hers, in relation to all things. As I said, the idea that making the dolls the way she does, or using corpse parts to do it might be sacrilege does not even occur to her.

Rather than go the route of the novel, Mary Jane twists this around too. In the world of Mary Jane, religious objects hold not only the power of an idea but an actual force. And it is a force that is completely, within the world of the show, amoral and nonsensical. The blessed weapons and fire the Order of the Shadows use are “holy” as a property, but that gives it no moral weight within the world of the play. And the play is messing with it the whole time. Holy wood or water can destroy a ghost, but they live in a church. Something that Charles and Figaro comment on, but cannot interrogate in terms of what it means for their conviction. But they’re split on how to proceed - the fact that ghosts can live in it doesn’t shake their faith, though. Sister Ghost is there largely for this joke. A nun who is constantly evoking the divine, who would be killed by a consecrated item.

[image description: the summary text over the chapel backdrop with the text of "the chapel where Jacob and the others were left behind was being filled with the scent of holy water.]

If I could add something to Mary Jane, I would have loved for Mary or Jacob to ask Sister Ghost what “God” means (this is a conversation that happens in bonus material for Tokyo Ghoul once, actually). I would have loved to have that brought up more explicitly. But it’s also very funny that it never is.

The first definitions for a God we get are them being applied to Mary herself, with plenty of ambiguity on if the Order’s faith itself has a mother figure at its center or not. And either way it’s a fascinating play on the idea, and the themes of the novel.

Closing Thoughts, Other Connections and Ideas "Beyond the Scope of this Essay"

Anyway, all of this while playing around with everything else going on in this play, Neji’s totally, without permission, commentary on Fumi, on Tsuki’s legacy (please read the stage script, somehow the game thought it was a good idea to cut that whole specific reference even when making Kisa pick between an “erase Tsuki” option) and on Kai. On himself as an artist. ("I am the one who is strange. With my changing moods, with my hobbies. That is why everyone thinks I'm strange and avoids me.”). As with several other plays, a commentary on authority, and on creation, and on isolation and friendship and connection.

And, of course, what I’ve been holding back this whole little essay is that Mary Jane is, thematically, at its core, playing off the exact same situation as I Am Death. Like — both of these plays center around a woman pouring her emotions into an undead creature. I see you Neji. You can’t hide from me. Reading I Am Death as a Frankenstein Story remixed into an old Japanese mytho-history is a LOT of fun to do, but is, as the academics say, beyond the scope of this essay.

(and, I Am Death itself is about Neji and Chui, and the twisted, messy love-hate revenge drama they are acting out across all the routes in the game. Neji writes the plays that introduce Chui to the world. Then he runs. And spends the whole game trying to beat him (affectionate.). “Make me another like me” you say…

Literally the only thing I’ve come up with to make the “bad end” CG more compelling to me, is that this is what it’s riffing on. I like my I Am Death costumes way weirder.)

Mary Jane is a Frankenstein Story, I Am Death is a Frankenstein Story, Jack Jeanne is a Frankenstein Story.

The other, other thing I’m leaving out here is that the Order of the Shadows are OBVIOUSLY pulled from Tokyo Grand Guignol, aesthetically. And the most famous TGG play is Litchi Hikari Club, which is, say it with me, a Frankenstein Story. Also one that takes the themes of the novel (gender, love and sexuality, childhood, genius, violence, blind pursuit to the point of madness, god complexes) harder than most, but runs with it in nearly the exact opposite direction. But again, very much beyond the scope of this essay.

Also also also leaving out the fact that Tokyo Ghoul is... kind of ... not not a Frankenstein story. It certainly riffs on the motif quite a bit. Even if you've never read it, you've seen the mask design (an in universe riff on the joke.).

Even just one dimension of this play, and look how many words you've made me write Neji-senpai.

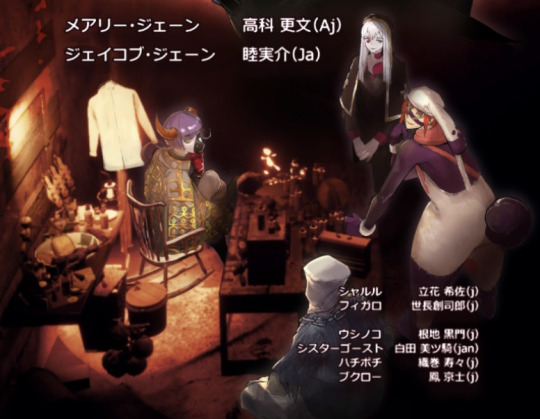

[image description: image from the bottom of the Mary Jane poster, with the cast list, showing the chapel ghosts with a focus on Ushinoko, Neji's character, looking towards the 'camera'.]

Some little Halloween Spooktacular you’ve got there. Bravo.

#jack jeanne meta#jack jeanne#Mary Jane#frankenstein#lit crit#doing lit crit of stories within stories - what a trip#meta

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the editors of Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility noted in 2017, visibility is neither the goal of liberatory political projects nor especially helpful toward achieving them. If daytime TV and commercial pornography count, trans people enjoyed plenty of representation before Time put Laverne Cox on its cover in 2014. Nor, given the popularity of trans memoir and the gender novel, did we lack for sympathetic renditions of challenging lives. Rather, what was missing was conceptual room for thinking about transition as a process that could touch on anybody’s life, rather than something that affected only some tragic, select individual. These books lacked ways of talking about the complicated, ambivalent, sometimes shitty, and constantly shifting patterns of thought and behavior that people take on when they live how we do. And they lacked the capacity to see trans people as authors of our lives and co-authors of our conditions.

In the past decade, the cultural front has shifted dramatically. The liberal hegemony that trans cultural creators challenged so forcefully has also crumbled on its right flank, as right-wing liberals in legacy publications raise doubts about whether young people should be able to access transition and far-right political actors in, for instance, the Greg Abbott and Ron DeSantis administrations criminalize trans care and work to eliminate social protections within their jurisdictions. Conditions have deteriorated, even as activists have become more adept at figuring out what to do about it. Realism does something; in the case of Nevada, whose first edition sold nearly ten thousand copies and by their own admission prompted people to transition, the work that realism does may wildly exceed simply representing the world in an inventive way. If that’s true, then who writes and what do they make possible to grasp are equally urgent questions. Displacing sentimental genres, the trans realism we’ve collectively developed—as readers, writers, and people who animate each other’s sense of the world in how we live our fuckup lives—transforms a whole way of seeing, at a moment when all kinds of people are trying to peer in.

Kay Gabriel, Whose Trans Realism?

[emphasis added]

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

kind of interesting how the land and the weather outside Gormenghast are the complete opposite of it in that they're brightly colored and changing and unpredictable, forest to desert to plains to rocks, baking heat to torrents of rain. And Gormenghast stands still and grey and unmoving, unchanging, bound in tradition more predictable than the seasons. Titus runs away to the forest again and again. The Thing lives in it and embodies it, even as she dies. Flay is banished to the forest but learns to love it and comes back gentler. Every time the rain comes in the books, it changes something important in Gormenghast. Fuchsia runs away to the forest when she's younger, but as she gets older and less free she does this less and less, and when she finally falls she hits her head on the grey stone of Gormenghast. Strange how she was looking at the water when she died, hoping it would release her even then.

I wonder if the still grey Gormenghast contrasted with the wild colorful country around it is anything like the English settlement in China where Mervyn Peake grew up. The traditions of the British Empire fading slowly in a fortress surrounded by an alien landscape with wild weather.

My small town feels a little like Gormenghast at times. I wonder if the world outside is bright and wild and dangerous, and if I could survive it.

#i lift my eyes to the hills#gormenghast#titus groan#fuchsia groan#mervyn peake#british empire#literary history#literary analysis#lit crit#literary criticism#though that seems pretentious#symbolism#man vs nature

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

After World War II, as the USA consolidated its position as the leading capitalist power in the world, so immense was the right-wing national consensus, so pathological the anti-communist phobia, that those lonely figures, such as Kenneth Burke, who continued to do serious radical work in literary and cultural theory were thoroughly marginalized.

The cumulative weight of this cultural configuration has been such that when ‘New Criticism’ appeared on the horizon – with its fetishistic notions of the utter autonomy of each single literary work, and its post-Romantic idea of ‘Literature’ as a special kind of language which yields a special kind of knowledge – its practice of reified reading proved altogether hegemonic in American literary studies for a quarter-century or more, and it proved extremely useful as a pedagogical tool in the American classroom precisely because it required of the student little knowledge of anything not strictly ‘literary’ – no history which was not predominantly literary history, no science of the social, no philosophy – except the procedures and precepts of literary formalism, which, too, it could not entirely accept in full objectivist rigour thanks to its prior commitment to squeezing a particular ideological meaning out of each literary text. The favourite New Critical text was the short lyric, precisely because the lyric could be detached with comparatively greater ease from the larger body of texts, and indeed from the world itself, to become the ground for analysis of compositional minutiae; the pedagogical advantage was, of course, that such analyses of short lyrics could fit rather neatly into one hour in the undergraduate classroom. This pedagogical advantage, and the attendant detachment of ‘Literature’ from the crises and combats of real life, served also to conceal the ideology of some of the leading lights of ‘New Criticism’ who were quaintly called ‘Agrarian Populist’ but were really bourgeois gentlemen of the New South, the cultural heirs of the old slaveowning class. What is even more significant, however, is that ‘New Criticism’reached its greatest power in the late 1940s, as the USA launched the Cold War and entered the period of McCarthyism, and that its definitive decline from hegemony began in the late 1950s as McCarthyism, in the strict sense, also receded and the Eisenhower doctrine began to give way to those more contradictory trends which eventually flowered during the Kennedy era – those golden years of US liberalism which gave us the Vietnam War. The peculiar blend of formalist detachment and deliberate distancing from forms of the prose narrative, with their inescapable locations in social life, into reified readings of short lyrics was, so to speak, the objective correlative of other kinds of distancing and reifications required by the larger culture.

Aijaz Ahmed, In Theory: Nations, Classes, Literatures

#im not sorry for turning into an aijaz ahmed blog#aijaz ahmad#cf that post by najia gothhabiba#readings#lit crit

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” – A Victorian Fairy Tale

Off and on, I’ve been thinking about Roald Dahl’s classic children’s story, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

A few years ago, it came to light that, according to Dahl’s widow, “His first Charlie that he wrote about was a little black boy.” This comes as some surprise to those who know the history of the novel, since the Oompa-Loompas were “pygmy Africans” in the first edition, and remained imported slave labor in all subsequent editions and adaptations.

The writer of the linked Guardian article seems to think that making the Oompa-Loompas orange-faced and green-haired somehow erases this fact, but come on now. Regardless of whether they’re a real people, the very premise of importing an entire population into your factory as labor is colonialist as can be, and coding them with uniform physical features is both racist and racialist.

This in itself is nothing new, but lately I’ve been reevaluating these parts of the text in light of the news that Charlie was originally black. The Guardian, predictably, only cares about Dahl’s reputation, but we should take it further. How does a black Charlie change our reading of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory itself?

Charlie was black, and the Oompa-Loompas were also black. Narratively and thematically, what do these two facts say in conjunction?

Suddenly, a lot of pieces fit together more tightly than they ever did before.

It's a story about the Faustian bargain that a person of minority status must often make with the powers that be—powers that trace their lineage back to empire.

Art by Quentin Blake, Roald Dahl’s official illustrator

Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory is a microcosm of the British Empire itself. It’s a titanic palace of industry, producing wonders never before seen in all the world—and it does so through the labor of enslaved non-white people, never seen and never spoken about. Wonka’s magical candies capture the magical feeling of going to the sweet shop as a little English child, but Dahl also heightens the dark reality of how that idyllic childhood fancy was produced, as well as the cruel and paternalistic morality that oversaw it. The rules of the English colonies govern Wonka’s workers, while the rules of the English schoolhouse and nursery govern Wonka’s visitors.

And on that note, it's worth mentioning that while the naughty children's punishments are rightly regarded as extreme by today's audiences, the morality behind them is not rejected outright. “That’s what you get! You shouldn’t be greedy or rude or undisciplined,” etc. Conventional parenting still shows its Victorian roots in countless small ways, and not just in the fact that some people today still spank their children. Moral goodness is measured in obedience, and in conformity to a very confining model of behavior. Veruca Salt might have been a spoiled little tyrant—but what did Violet Beauregard really do? She was rude and excitable, and chewed with her mouth open. You know, things that children do because they’re children. Yet these behaviors were strictly managed and punished in nineteenth and early twentieth century English society.

Anyway, I’m getting away from the main point...

Into this world enters Charlie, a poor black boy who lives in a slum with his mother and his four grandparents. He, like all the other children, sees the hidden secrets of the factory. He sees the miraculous candies, the chocolate river, the pink candy boat. He sees the Oompa-Loompas. He listens, like all the other guests, to Willy Wonka’s stories and speeches and eccentric quips.

Yet while the other children buck against the rules of Wonka’s little kingdom, Charlie obeys. Like a poor black boy does in a world run by wealthy white men, he makes himself small and polite. Yes, he’s more virtuous than the other children by consequence of how he was raised—but he’s also conforming to a social script on which his survival depends, something that the spoiled little white children have never needed to do. This is how he reaches the end of the tour unharmed.

This is also the reason why, when offered all of Wonka’s empire as inheritance, he accepts it. The choice is no choice at all. On the one hand, he can inherit a morally bankrupt system that churns out wealth on the backs of imported slaves... and on the other hand, he can refuse, and allow his family to continue starving in the slums.

And that choice carries much more weight when Charlie Bucket is black himself.

When Charlie is black, his story lays bare the moral quandary at the heart of modern capitalism. When Charlie’s skin is the same color as the Oompa-Loompas’, you can’t help but see it. The only way to make a better life for yourself is to embrace an economic system that began in an era when companies traded human beings as property, and that has still not cut ties with the wealth made from those grave moral crimes. When your very life is at stake, you have no choice but to make a compromise with these entities. And the more you stand to gain, the bigger the compromise you must make.

An extra layer of dark irony comes from that fact that Willy Wonka himself is probably the reason why Charlie’s family is poor in the first place. Not only is he part of the capitalist class, but he doesn’t even circulate money back into the economy, like other capitalists claim to do.

The Oompa-Loompas don’t get wages which they then spend out in the surrounding community. They’re paid in cacao beans, a cheap resource that Wonka has aplenty. All the business profits go directly to Wonka, and this money never leaves his factory except in the purchasing of more materials. His factory is a huge economic drain on the area, and Charlie’s family is likely impacted by it directly.

Anyway...

All of this is to say that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was conceived of as “a Victorian fairy tale,” but not as an unthinking reproduction of Victorian values. Roald Dahl was all about subverting and undercutting expectations—sometimes with an overt twist, as in the story “Genesis and Catastrophe,” and sometimes with a subtle, growing unease that never resolves. Though he clearly backed down from this in the final version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the vestiges of a dark satire remain. As it turns out, Charlie himself was the missing piece to this, turning the factory’s vague tonal undercurrent of wrongness into pointed, directed criticism.

I would love to see a black writer, someone in the vein of Jordan Peele, extract this stuff from where it has been buried under layers of editing and editorializing, and put it on the screen or the stage.

#charlie and the chocolate factory#willy wonka#willy wonka and the chocolate factory#literature#children's literature#literary criticism#lit crit#Jordan Peele#Roald Dahl#colonialism#litblr#lit blog

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

emily wilson comparing the inevitable earth-death to the truth-telling experience of the story of the iliad, where "your knowing changes nothing" but still you do know because:

"A new kind of heartbreak can be felt in The Iliad's representation of a city in its last days, of triumphs and defeats and struggles and speeches that take place in a city that will soon be burned to the ground, in a landscape that will soon be flooded by all the rivers, in a world where soon, no people will live at all, and there will be no more stories and no more names."

is in conversation with the ecocritical argument that grief and death and mourning will take us through the end, whatever it looks like, from bruno latour insisting on entering a "subjectivity" with everything else in the world now just as "subject" as us (not object) for being subjected to themselves and the othered phenomena, to donna haraway speculating about Speakers of the Dead who are humans that mutate their bodies to resemble those bodies of extinct or going-extinct creatures---

heartbreak is the only thing to be felt, in the end, they're claiming. anger and the will to fight are often object-less and externalized but they cannot change what is already written, despite their illusion of true power. no, it's the lamenters who remember and will guide the audience thru the narrative's conclusion. the vulnerability of knowing the story, a knowing that "changes nothing," but when all stories do inevitably vanish, at least they were told in the most prolonged way possible.

21 notes

·

View notes