#literary critic

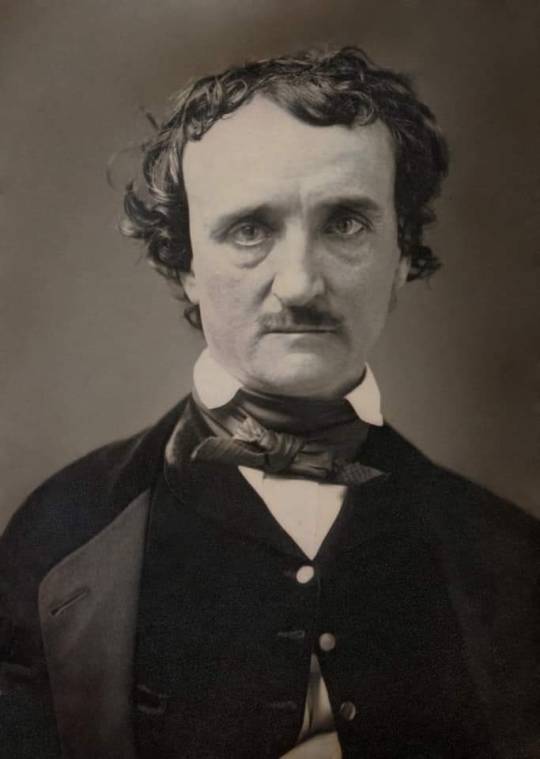

Photo

Edgar Allan Poe

#Edgar Allan Poe#poet#writer#American writer#literary critic#poetry#short stories#Romanticism#detective fiction#American literature

279 notes

·

View notes

Photo

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idea Vilariño on a sea-side rock.

Idea Vilariño Romani (1920-2009) was a Uruguayan poet, essayist and literary critic.

You Didn’t Know

My poor love

you believed

that it was so

you didn’t know.

It was richer than that

it was poorer than that

it was life and you

with your eyes closed

you saw your nightmares

and you called that

life.

#Idea Vilariño#poet#essayist#literary critic#translator#lecturer#Uruguay#poetry#poem#You Didn’t Know#words#old photo#sea side rock#sea#rocks#young

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title/Name: Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849).

Bio: American writer, poet, author, editor, and literary critic.

Country: USA

Wojak Series: Feels Guy (Variant)

Image by: Wojak Gallery Admin

Main Tag: Edgar Allan Poe Wojak

#Edgar Allan Poe#Poe#Author#Poet#Editor#literary critic#Feels Guy#Bio#Writer#Writer Author#Variant#American#USA#Wojak#Feels Guy Wojak#Edgar Allan Poe Wojak#Feels Guy Series#White#Gray#Black

0 notes

Text

The Anatomy of Ghosts - Crime Novel Review

Author: Andrew Taylor

Publisher:

Country: UK

Year: 2010

The Anatomy of Ghosts, right from the outset, finds a strangely modern line of thinking. Set at the end of the 1700s, nearly 100 years before SPR (Society for Psychical Research) was set up, we have a novel following Mr Holdsworth, who has lost his son and wife months before, and has recently published the titular Anatomy of Ghosts, a…

View On WordPress

#andrew taylor review#award winner#award winning book#book critic#book review#crime book review#crime books#crime novel review#critic#ghost book review#horror book review#literary critic#literature review#novel review#review#the anatomy of ghosts review#thriller review

0 notes

Text

A young woman at a window?

A young woman at a window?

My way of life means that I can be found walking through this city late at night, or even early in the morning, for perfectly respectable reasons.

After all, I can hardly tell the hostess and her hard pressed household staff that I have to go home to my bed when they still have two hours of tidying up to cope with before they can get to theirs. So I often arrive home in what are romantically…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

hello, i kno close reading aint the only way to analyse a text but im trying to find other ways of doin it but google is just givin me how to do close readings in your classroom things. idk im not a booksguy really tho id like to learn how to books better. do u have any like basic resources for ways to read a text an figure out whats goin on in it that isnt doing a close reading? thanks

Close readings are mostly associated with new criticism. This school of criticism, like every other, arose in a particular time and place and can be analysed as having arisen for a particular reason. Also like every school of criticism, it has its adherents and its detractors. But considering the "work" as its own whole, self-contained aesthetic object in the way that NC does is not the only way to read.

Some other approaches, off the top of my head, & the schools of criticism they're roughly associated with:

How does the work make you feel? What are your reactions to it? What emotions and associations does it conjure up? What is your spatial or temporal experience like reading the work (like, how does the work appear to you as something that unfolds over time, as you read it? When and how are you reading it)? How do your expectations about a certain work affect how you read? [Reader-response]

What is the economic and ideological history of the genre, form, and aesthetics of the work in question? What ideological function does the work seem to serve? Does it serve to convince its readers of anything, and if so, what political implications does its viewpoint have? What ideas of oppression, history, and the forms that resistance can take does the work present or seem to advocate for? What does it make visible or invisible, what does it make seem possible or impossible? [Marxist literary criticism / Marxist aesthetics]

When, where, and by whom was the work published? What else do we know about the author's opinions on aesthetics, politics, &c., and how do we know it? How are those opinions reflected by, or in tension with, what you see in the work? Were there any problems getting the work published, and, if so, do they have to do with the author's class or gender or politics, &c.? Where and how was the author living (richly or poorly, working as a maid in another household or employing servants or a wife to free up time for intellectual pursuits) while writing?

And, doubling down on when the work was published—what were the popular or dominant discourses about science, biology, human cognition, political economy, race, gender, war, &c. &c. when and where the author wrote and published? How does the work seem to mobilise, use, subvert, echo, further, or contest those discourses? How would the work's first readers have read it in light of the popular discourses they were familiar with? [contextualism; new historicism]

What materials was the book originally published in? Where did those materials come from? Was it cheaply or expensively made? How much was it sold for? Who would have been able to afford it? What does the form of the book (any illustrations? what's the typeface and size? margin size? hardcover or paperback?) imply about who is meant to read the work, and how they're meant to read it? What effect did the state of print technology at the time of the book's publishing have on its final form (e.g., it used to be impossible to have text and an image on the same page in a mass-produced book)? Where do the objects described in the book presumably come from, and by whose labour would they have been produced and transported? What does this say about the material lives of the characters? [Material culture studies]

What are the early notices and reviews of the book like, and where do they appear? Who wrote them and where did they publish them? Is the book mentioned in diaries and letters from around the time of its publication? How did the responses to the book change over time? How did audiences in different places, or of different demographics in other ways, respond to the book? What went into making the book accessible to new audiences over time? What extra-textual stuff (“paratext”: book covers, advertisements, interviews, reviews) influence how people read the work? [Reception history; translation studies; maybe fandom studies]

Who edited the work? How much control did the publishing house, and the publishing house's readers, have over the final format of the text? Who decided what the punctuation would be like, and where the chapter breaks would go? Who decided on the spelling (was it published at a time when spelling was standardized? Did the author's manuscript contain any idiosyncratic spellings? Did the publishing house have a house style)? Are there any ideological connotations to "correcting" this author's spelling? Was the author's manuscript typed or handwritten? Were there any problems reading their handwriting? How many versions of the manuscript were there, and how did the publishing house chuse which to work from? [Editorial theory]

These associations between methods of reading and schools of criticism are mostly just to give you terms to look up to read more. Scholars don't all necessarily belong firmly to a given school, and people often mix and match various modes of reading to be able to argue what they want to argue.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

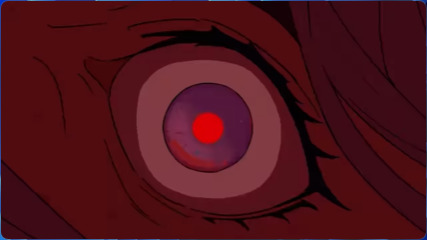

Critical Role's Cameraman

So, Critical Role (@criticalrole) just released their newest opening title sequence, an animated sequence in the same style of Your Turn To Roll and I would be remis as a film nerd to not pick apart every detail.

What fascinates me about this introduction, however, is the camera movement and shot composition. Allow me to explain.

I DONT THINK THERE ARE SPOILERS AHEAD, BUT JUST TO BE SAFE

So, we open with a hand, this is a close up, I don't think that is unobvious.

But this stops being a close up rather quickly, before it starts moving away. The shot just gives the hand context, and suddenly you aren't in an extreme close up of a hand, you are in a medium shot of a very large person. Then the camera pans backwards, and you can see villains and places spring up, although the perspective on Matt remains weird. Is he a few metres from you, or a hundred? How big is the Game Master here? There's a sense of mystery, of incomprehension. This is setting up some cosmic horror shenaniganry.

Then, we get Fearne. This is a wide camera motion, swivelling around her in a tracking shot that focuses on her face, and those eyes. It is like a reverse panorama, where Fearne is taking in the world, the world is observing Fearne.

But I want you to take note of the leaves here, because they are used to form a connection between her and Orym. The transition uses them, while it isn't a direct wipe transition (the leaf just flies close to mask an abrupt cut), it is framed as one. The name of that isn't important, though, what's important is the leaves. By being in both shots, they emphasise the relationship between the two characters. But where for Fearn they show off her sense of wonder, for Orym, they take on a very different meaning.

Notice, however, how still this shot is. There is no sense of danger here. This is a scene of a warrior with a sword and two people passing on from this world. But it's calm. Because this is a memory. Orym might not be at peace with the death, but the memory isn't a violent one, it's a memory of his family's lives.

Cut to a close up. Orym creates a gust of wind.

And cut to the next shot.

I will not lie, Bertrand is my favourite character across all of Critical Role, so this shot of him made me smile, but it isn't the point here. The point is Imogen's introduction.

Although is Bertrand not actually the point? Because take a look at how Imogen is shown here. Do you notice anything?

She's shown in the exact same way. Imogen is shown doing the exact same thing that those who have died have done. And she can see them ahead of her. The camera panning back shows a wider perspective here, showing her as she tries to run, tries to get away from the same path as Bertrand.

The wind from Orym's blade that came to this scene gets across a consistent element: Memory. This is a dream. But dreams can become nightmares.

As Imogen loses her footing, the camera gives some of its wildest movements yet. It tumbles around her, then looks up.

The camera stops moving when it sees the red moon, because now the viewer has something to orientate themselves around. There is a constant point, and we can see Imogen falling down. And getting closer, and closer, and closer, until.

These are the three frames in order, there is nothing in between.

Imogen crashes into the screen, and we get an abrupt impact frame (that's the black and white one) then Ashton. This is so cool to watch, in my opinion, but it is quite possibly the opposite of smooth in camera work. So why is it so cool? Motion.

The motion is in towards Imogen and out away from Ashton. They are both falling, just in different directions. And the impact frame both helps smooth over and accentuate the abrupt transition.

The camera around Ashton is a tracking shot. They are falling, but they remain the exact same in the screen (shrinking slightly). The rest of the world moves. And when Ashton lands, the screen cracks. The tracking shot is used to show Ashton's disassociation with their surroundings. Not in a "I feel nothing" type of way, but in a "it's me vs the world" type of way.

Then, there is an abrupt cut away. Nothing hides or smooths this at all, because Ashton's memory isn't smooth, and neither is Ashton. Remember the disassociating thing I mentioned, now it changes again to someone who gets lost in his thoughts. Medium.com calls this an "anxiety stare" and as someone who does that on the regular, I can attest to this abruptness being exactly what that feels like.

I'm not going to talk too much about the ship, but just be aware that there is a Dutch angle (the horison is diagonal) here to heighten the stress of it.

Likewise with this shot, there isn't much to talk about. The slow outward zoom and triangular composition are neat, and the tiered reactions (bottom row reacts, then middle, then Fearne) are amusing, but other than that, not much.

Then we meet Laudna, playing with Pate and giving him life. That's a neat little shot, I wonder if there's a metaphor there.

Oh.

This is a super cool visual because it establishes exactly who this character is in two seconds. But I also want to point out the symmetry of this. The hair becomes the blood which becomes the hair again, and then the tree.

Laudna is introduced as big and scary and imposing, and that is very intentionally undercut by making her look small.

Being small means you are less likely to be the focal character, so shrinking Laudna takes away her agency. Only to give it back through Imogen, and when the camera pans back outwards, Laudna is the same size, but the colours and the surroundings make her feel less alone, and as a weird result of that, less small.

And last but not least in this moment, there is the delayed drop of the hands. Laudna finally feels safe and finally breathes a sigh of relief.

That, however, imediately match cuts to this. FCG's vision. The red tinting has obvious implications that I don't need to explain, but the match cut heavily implies a connection between this group and the Bells Hells. There is a fear that this might happen again made clear by a single transition.

Here's something else. FCG doesn't move. At least, the camera doesn't treat them as moving. It's a slow panning out as if nothing is happening. It's the disassociation vibe that you get from Ashton's falling shots now repurposed to someone who isn't in control of their own actions. This is what FCG is afraid of, this is the important pieces of his character. This is FCG.

And just like Laudna, FCG finally gains agency when surrounded by their friends who hug them, and FCG finally moves.

Chetney Pock O'Pea, outlaw of the RTA, alpha of his own heart. A fundamentally chaotic character who takes rules as suggestions to be intentionally ignored. A man who's first instinct upon meeting you is to consider how you could be killed. And he is introduced whittling, with a steady camera and warm light illuminating his face. This is a peaceful side of Chetney, there is a duality to him.

Speaking of which, notice how Chetney draws back from the light as he transforms. His eyes begin to glow, but they don't illuminate him, until this:

Chetney is now backlit by the cold light of the moon itself (There's a neat reveal of Ruidus caused by the pan, but that's only tangentially relevant). Notice how much further you are from him here than in his first shot. But notice how much of him is visible, and how much of the screen he takes up. It's the same, this is still the same character. It's a true Doctor Jeckyl and Mr Hyde character. This isn't split personality, but a character who can be a different person in each form, while still remaining Chetney at all times.

There is more in this video. I encourage you to watch it, but unfortunately, Tumblr has a limit on how many images I can include, so I will leave you with this final shot. A group of heroes looking up at a threat that is so much bigger than them, a threat that is literally controlling the light. But the Bells Hells are closer to the camera, they take up more of the screen. The battle isn't lost, instead, it is just starting.

#rants#literary analysis#literature analysis#media analysis#critrole#critical role#bells hells#imogen temult#laudna#ashton greymoore#fcg#orym of the air ashari#fearne calloway#chetney pock o'pea#its Thursday night#critical role bells hells

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

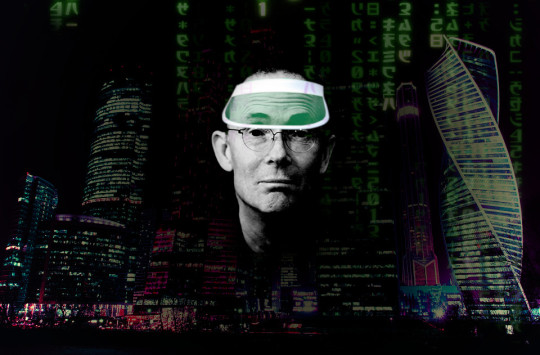

The true post-cyberpunk hero is a noir forensic accountant

I'm touring my new, nationally bestselling novel The Bezzle! Catch me in TOMORROW (Apr 17) in CHICAGO, then Torino (Apr 21) Marin County (Apr 27), Winnipeg (May 2), Calgary (May 3), Vancouver (May 4), and beyond!

I was reared on cyberpunk fiction, I ended up spending 25 years at my EFF day-job working at the weird edge of tech and human rights, even as I wrote sf that tried to fuse my love of cyberpunk with my urgent, lifelong struggle over who computers do things for and who they do them to.

That makes me an official "post-cyberpunk" writer (TM). Don't take my word for it: I'm in the canon:

https://tachyonpublications.com/product/rewired-the-post-cyberpunk-anthology-2/

One of the editors of that "post-cyberpunk" anthology was John Kessel, who is, not coincidentally, the first writer to expose me to the power of literary criticism to change the way I felt about a novel, both as a writer and a reader:

https://locusmag.com/2012/05/cory-doctorow-a-prose-by-any-other-name/

It was Kessel's 2004 Foundation essay, "Creating the Innocent Killer: Ender's Game, Intention, and Morality," that helped me understand litcrit. Kessel expertly surfaces the subtext of Card's Ender's Game and connects it to Card's politics. In so doing, he completely reframed how I felt about a book I'd read several times and had considered a favorite:

https://johnjosephkessel.wixsite.com/kessel-website/creating-the-innocent-killer

This is a head-spinning experience for a reader, but it's even wilder to experience it as a writer. Thankfully, the majority of literary criticism about my work has been positive, but even then, discovering something that's clearly present in one of my novels, but which I didn't consciously include, is a (very pleasant!) mind-fuck.

A recent example: Blair Fix's review of my 2023 novel Red Team Blues which he calls "an anti-finance finance thriller":

https://economicsfromthetopdown.com/2023/05/13/red-team-blues-cory-doctorows-anti-finance-thriller/

Fix – a radical economist – perfectly captures the correspondence between my hero, the forensic accountant Martin Hench, and the heroes of noir detective novels. Namely, that a noir detective is a kind of unlicensed policeman, going to the places the cops can't go, asking the questions the cops can't ask, and thus solving the crimes the cops can't solve. What makes this noir is what happens next: the private dick realizes that these were places the cops didn't want to go, questions the cops didn't want to ask and crimes the cops didn't want to solve ("It's Chinatown, Jake").

Marty Hench – a forensic accountant who finds the money that has been disappeared through the cells in cleverly constructed spreadsheets – is an unlicensed tax inspector. He's finding the money the IRS can't find – only to be reminded, time and again, that this is money the IRS chooses not to find.

This is how the tax authorities work, after all. Anyone who followed the coverage of the big finance leaks knows that the most shocking revelation they contain is how stupid the ruses of the ultra-wealthy are. The IRS could prevent that tax-fraud, they just choose not to. Not for nothing, I call the Martin Hench books "Panama Papers fanfic."

I've read plenty of noir fiction and I'm a long-term finance-leaks obsessive, but until I read Fix's article, it never occurred to me that a forensic accountant was actually squarely within the noir tradition. Hench's perfect noir fit is either a happy accident or the result of a subconscious intuition that I didn't know I had until Fix put his finger on it.

The second Hench novel is The Bezzle. It's been out since February, and I'm still touring with it (Chicago tonight! Then Turin, Marin County, Winnipeg, Calgary, Vancouver, etc). It's paying off – the book's a national bestseller.

Writing in his newsletter, Henry Farrell connects Fix's observation to one of his own, about the nature of "hackers" and their role in cyberpunk (and post-cyberpunk) fiction:

https://www.programmablemutter.com/p/the-accountant-as-cyberpunk-hero

Farrell cites Bruce Schneier's 2023 book, A Hacker’s Mind: How the Powerful Bend Society’s Rules and How to Bend Them Back:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/06/trickster-makes-the-world/

Schneier, a security expert, broadens the category of "hacker" to include anyone who studies systems with an eye to finding and exploiting their defects. Under this definition, the more fearsome hackers are "working for a hedge fund, finding a loophole in financial regulations that lets her siphon extra profits out of the system." Hackers work in corporate offices, or as government lobbyists.

As Henry says, hacking isn't intrinsically countercultural ("Most of the hacking you might care about is done by boring seeming people in boring seeming clothes"). Hacking reinforces – rather than undermining power asymmetries ("The rich have far more resources to figure out how to gimmick the rules"). We are mostly not the hackers – we are the hacked.

For Henry, Marty Hench is a hacker (the rare hacker that works for the good guys), even though "he doesn’t wear mirrorshades or get wasted chatting to bartenders with Soviet military-surplus mechanical arms." He's a gun for hire, that most traditional of cyberpunk heroes, and while he doesn't stand against the system, he's not for it, either.

Henry's pinning down something I've been circling around for nearly 30 years: the idea that though "the street finds its own use for things," Wall Street and Madison Avenue are among the streets that might find those uses:

https://craphound.com/nonfic/street.html

Henry also connects Martin Hench to Marcus Yallow, the hero of my YA Little Brother series. I have tried to make this connection myself, opining that while Marcus is a character who is fighting to save an internet that he loves, Marty is living in the ashes of the internet he lost:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/07/dont-curb-your-enthusiasm/

But Henry's Marty-as-hacker notion surfaces a far more interesting connection between the two characters. Marcus is a vehicle for conveying the excitement and power of hacking to young readers, while Marty is a vessel for older readers who know the stark terror of being hacked, by the sadistic wolves who're coming for all of us:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I44L1pzi4gk

Both Marcus and Marty are explainers, as am I. Some people say that exposition makes for bad narrative. Those people are wrong:

https://maryrobinettekowal.com/journal/my-favorite-bit/my-favorite-bit-cory-doctorow-talks-about-the-bezzle/

"Explaining" makes for great fiction. As Maria Farrell writes in her Crooked Timber review of The Bezzle, the secret sauce of some of the best novels is "information about how things work. Things like locks, rifles, security systems":

https://crookedtimber.org/2024/03/06/the-bezzle/

Where these things are integrated into the story's "reason and urgency," they become "specialist knowledge [that] cuts new paths to move through the world." Hacking, in other words.

This is a theme Paul Di Filippo picked up on in his review of The Bezzle for Locus:

https://locusmag.com/2024/04/paul-di-filippo-reviews-the-bezzle-by-cory-doctorow/

Heinlein was always known—and always came across in his writings—as The Man Who Knew How the World Worked. Doctorow delivers the same sense of putting yourself in the hands of a fellow who has peered behind Oz’s curtain. When he fills you in lucidly about some arcane bit of economics or computer tech or social media scam, you feel, first, that you understand it completely and, second, that you can trust Doctorow’s analysis and insights.

Knowledge is power, and so expository fiction that delivers news you can use is novel that makes you more powerful – powerful enough to resist the hackers who want to hack you.

Henry and I were both friends of Aaron Swartz, and the Little Brother books are closely connected to Aaron, who helped me with Homeland, the second volume, and wrote a great afterword for it (Schneier wrote an afterword for the first book). That book – and Aaron's afterword – has radicalized a gratifying number of principled technologists. I know, because I meet them when I tour, and because they send me emails. I like to think that these hackers are part of Aaron's legacy.

Henry argues that the Hench books are "purpose-designed to inspire a thousand Max Schrems – people who are probably past their teenage years, have some grounding in the relevant professions, and really want to see things change."

(Schrems is the Austrian privacy activist who, as a law student, set in motion the events that led to the passage of the EU's General Data Privacy Regulation:)

https://pluralistic.net/2020/05/15/out-here-everything-hurts/#noyb

Henry points out that William Gibson's Neuromancer doesn't mention the word "internet" – rather, Gibson coined the term cyberspace, which, as Henry says, is "more ‘capitalism’ than ‘computerized information'… If you really want to penetrate the system, you need to really grasp what money is and what it does."

Maria also wrote one of my all-time favorite reviews of Red Team Blues, also for Crooked Timber:

https://crookedtimber.org/2023/05/11/when-crypto-meant-cryptography/

In it, she compares Hench to Dickens' Bleak House, but for the modern tech world:

You put the book down feeling it’s not just a fascinating, enjoyable novel, but a document of how Silicon Valley’s very own 1% live and a teeming, energy-emitting snapshot of a critical moment on Earth.

All my life, I've written to find out what's going on in my own head. It's a remarkably effective technique. But it's only recently that I've come to appreciate that reading what other people write about my writing can reveal things that I can't see.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/17/panama-papers-fanfic/#the-1337est-h4x0rs

Image:

Frédéric Poirot (modified)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredarmitage/1057613629 CC BY-SA 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

#pluralistic#science fiction#cyberpunk#literary criticism#maria farrell#henry farrell#noir#martin hench#marty hench#red team blues#the bezzle#forensic accountants#hackers#bruce schneier#post-cyberpunk#blair fix

176 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Edgar Allan Poe#The Simpsons#Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Raven'#cartoon#classic cartoons#cartoons#Edgar Allan Poe was an American writer poet editor and literary critic#poet#literary critic#editor#The Raven#classic cartoon

228 notes

·

View notes

Photo

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

With the rise of booktok/booktwt, there's been this weird movement against literary criticism. It's a bizarre phenomenon, but this uptick in condemnation of criticism is so stifling. I understand that with the rise of these platforms, many people are being reintroduced into the habit of reading, which is why at the base level, I understand why many 'popular' books on booktok tend to be cozier.

The argument always falls into the 'this book means too much to me' or 'let people enjoy things,' which is rhetoric I understand -- at least fundamentally. But reading and writing have always been conduits for criticism, healthy natural criticism. We grow as writers and readers because of criticism. It's just so frustrating to see arguments like "how could you not like this character they've been the x trauma," or "why read this book if you're not going to come out liking it," and it's like...why not. That has always been the point of reading. Having a character go through copious amounts of trauma does not always translate to a character that's well-crafted. Good worldbuilding doesn't always translate to having a good story, or having beautiful prose doesn't always translate into a good plot.

There is just so much that goes into writing a story other than being able to formulate tropable (is that a word lol) characters. Good ideas don't always translate into good stories. And engaging critically with the text you read is how we figure that out, how we make sure authors are giving us a good craft. Writing is a form of entertainment too, and just like we'd do a poorly crafted show, we should always be questioning the things we read, even if we enjoy those things.

It's just werd to see people argue that we shouldn't read literature unless we know for certain we are going to like it. Or seeing people not be able to stand honest criticism of the world they've fallen in love with. I love ASOIAF -- but boy oh boy are there a lot of problems in the story: racial undertones, questionable writing decisions, weird ness overall. I also think engaging critically helps us understand how an author's biases can inform what they write. Like, HP Lovecraft wrote eerie stories, he was also a raging racist. But we can argue that his fear of PoC, his antisemitism, and all of his weird fears informed a lot of what he was writing. His writing is so eerie because a lot of that fear comes from very real, nasty places. It's not to say we have to censor his works, but he influences a lot of horror today and those fears, that racial undertone, it is still very prevalent in horror movies today. That fear of the 'unknown,'

Gone with the Wind is an incredibly racist book. It's also a well-written book. I think a lot of people also like confine criticism to just a syntax/prose/technical level -- when in reality criticism should also be applied on an ideological level. Books that are well-written, well-plotted, etc., are also -- and should also -- be up for criticism. A book can be very well-written and also propagate harmful ideologies. I often read books that I know that (on an ideological level), I might not agree with. We can learn a lot from the books we read, even the ones we hate.

I just feel like we're getting to the point where people are just telling people to 'shut up and read' and making spaces for conversation a uniform experience. I don't want to be in a space where everyone agrees with the same point. Either people won't accept criticism of their favorite book, or they think criticism shouldn't be applied to books they think are well written. Reading invokes natural criticism -- so does writing. That's literally what writing is; asking questions, interrogating the world around you. It's why we have literary devices, techniques, and elements. It's never just taking the words being printed at face value.

You can identify with a character's trauma and still understand that their badly written. You can read a story, hate everything about it, and still like a character. As I stated a while back, I'm reading Fourth Wing; the book is terrible, but I like the main character. The worldbuilding is also terrible, but the author writes her PoC characters with respect. It's not hard to acknowledge one thing about the text, and still find enough to enjoy the book. And authors grow when we're honest about what worked and what didn't work. Shadow and Bone was very formulaic and derivative at points, but Six of Crows is much more inventive and inclusive. Veronica Roth's Carve the Mark had some weird racial problems, but Chosen Ones was a much better book in terms of representation. Percy Jackson is the same way. These writers grow, not just by virtue of time, but because they were critiqued and listened to that critique. C.S. Lewis and Tolkien always publically criticized each other's work. Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes had a legendary friendship and back and forth with one another's works which provides so much insight into the conversations black authors and creatives were having.

Writing has always been about asking questions; prodding here and there, critiquing. It has always been a conversation, a dialogue. I urge people to love what they read, and read what they love, but always ask questions, always understand different perspectives, and always keep your mind open. Please stop stifling and controlling the conversations about your favorite literature, and please understand that everyone will not come out with the same reading experience as you. It doesn't make their experience any less valid than yours.

#long post#literary critique#literary criticism#booktok#books & libraries#booktwitter#but yeah it’s really hard for me to embrace booktube#and BookTok when the conversations that are most prevalent#are the ones telling people to not be critical of what they’re reading#esp the ones who desparately don’t want to understand differing opinions#‘how could you not like this’ or ‘how could you hate this character’#easily#because I can#a traumatic backstory isn’t gonna erase a bad story#it isn’t going to make a character or book compelling#more trauma doesn’t make the story more complex#see: with fourth wing.#thank you for reading this long rant#congrats if you make it to the tags💀😭

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Title/Name: Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre, popularly known as 'Jean-Paul Sartre', (1905–1980).

Bio: French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary critic.

Country: France

Wojak Series: Boomer (Variant)

Image by: Unknown

Main Tag: Sartre Wojak

#Wojak#Sartre Wojak#philosopher#novelist#political activist#biographer#literary critic#jean paul sartre#sartre#Author#France#Boomer#Writer Author#politics#Boomer Wojak#Jean-Paul Sartre Wojak#Boomer Series#White#Writer#Black

0 notes

Text

I truly do think one of the largest pitfalls among the "media consumption is my passion" crowd is the tendency to treat characters as human beings with agency rather than narrative tools manipulated by the author

#as soon as you start assigning agency to characters any criticism of the series comes under strawman fallacy arguments#about how humans make irrational choices not always understood by others etc etc etc#thus insulating the author and the work from any sort of meaningful criticism or analysis#i think current popular advice on character writing overemphasizes relatability and likability at the expense of narrative relevance#it certainly isn't hurtful to do exercises where you think about their coffee order or favourite animal or preferred toilet paper brand#but none of that matters in the end if you have no idea what purpose a character is supposed to serve in a literary sense

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know the average reading comprehension on this site is zero but I'm different. I'm applying wildly inappropriate analysis lenses to popcorn media. I'm doing a queer theory reading of Horus Heresy novels. Now I'm doing feminist analysis of Warhammer 40k canon. Now I'm applying Marxist analysis to The Outsiders. Time for a historical analysis of The Locked Tomb. A post-colonial reading of the entirety of Doctor Who. A psychological anlaysis of Twilight. On the horseshoe scale of reading comprehension I'm at "so much reading comprehension that it loops back around to not understanding books at all actually". You can't stop me. I'm literary analysis Georg

#I paid many thousands of dollars for this degree#and by god i will use it#literature#Literary analysis#Literature analysis#Media analysis#literary criticism#reading#reading comprehension#meta analysis#literature major#literature memes#lit crit#media literacy

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

GUYS, I FIGURED OUT THE BLACK TURTLES!

It's a detail of OTGW that's lowkey perplexed me since the series first aired. What's with the black turtles that appear in every episode? What role do they serve in the story, and what do they represent?

A small, seemingly inconsequential detail, but just the sort to occupy my mind every time I watch the show.

My first train of thought: Are they manifestations of The Beast's power and influence? If not, why does eating one turn Beatrice's dog into a slavering monster? But if so, why is Auntie Whispers purely benevolent despite eating one (and presumably much more)? Why aren't they themselves monstrous and malevolent? But also why aren't they, on the contrary, beautiful and benevolent? They're just ... sorta there, which suggests there's no supernatural nor moral element to them. Yet they're clearly not natural turtles, either ...

My second train of thpught: Are they representations of the Unknown's liminal nature, moving between land and water just as the Unknown is between life and death? Thus a foreshadow and a reminder of the brother's state? It would sorta make sense, given their omnipresence. Mirrored by the brother's Frog, whose amphibious nature is likewise liminal. And the weirdness of turtles specifically for this symbolic role fits the the weird aesthetic of The Unknown. Still, it didn't seem to quite fit.

BUT TONIGHT, I FIGURED OUT WHERE THEY COME FROM! THE OLD GRIST MILL!

WHERE THE WOODSMAN HAS BEEN GRINDING EDELWOOD TREES INTO A DISTINCTIVELY BLACK OIL FOR THE LANTERN!

SOME OF WHICH MUST BE WASHED OFF, LEAKING, OR EVEN SPILLED OUTRIGHT INTO THE STREAM THAT POWERS THE MILL, AND THUS CONTAMINATING THE ENVIRONMENT!

It's pollution. Industrial Revolution era pollution is the reason for the black turtles distinctive color and weird effects on some people, but not others.

#over the garden wall#otgw#turtle#pollution#environment#literary analysis#critical analysis#literary theory

354 notes

·

View notes