#london history

Text

Completed in 1209, bustling London Bridge was the longest inhabited bridge in the world.. like its own town for over 600 years.

#London Bridge#Old London#River Thames#Old England#UK#mediaeval#churches#classic architecture#artist's rendition#London history#river traffic#inhabited bridge#1209

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

London mews were built when London's property developers in the 18th and 19th century were creating mansions for the Georgian and Victorian elites. The mews were originally the stables, coach houses and accommodation for the coach driver and grooms, built to service these mansions. These days they are expensive and desirable accommodation for well-heeled Londoners.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

So not only was Jack Straw's Castle a well known gay hook up place, but actually all of Hamstead Heath was known for hookups too! The oldest evidence I found was in the 1950s, where drag balls were regularly held in Hamstead Town Hall. I couldn't find anything related to the late Victorian era either. The most well known 19th century spots for gay/bi men to hook up was more in central London, like Finsbury Park, St James Park, and Russell Square.

Soooo while there's no concrete evidence (Via quick Internet search), it's certainly a hell of a coincidence that our favorite scientific duo spent the night desecrating a tomb with sperm whale candles and avoiding the police.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collection Highlight: Handbook to London As It Is

Welcome to a new series on our blog where we highlight a book (or a number of books) from one of our lesser-known collections. In this post, we’re taking a look at Murray’s Modern London from our beloved London Collection. A collection dedicated to the past and present of all things London.

Samuel Johnson is famous for saying that to be bored of London is to be bored of life. This does not seem truer when looking at Middle Temple Library’s modest London Collection.

Every book reveals another layer of this old city making it new again. It would be entirely too much fun to talk at length about all the books in this collection, but I have chosen Murray’s Modern London, or Handbook to London As It Is (read the 1851 edition on Internet Archive).

If you happen to be thinking about journeying to London 1879, this is the guide for you. To begin with, it is a lovely little pocket-sized book. A woman of distinction can easily tuck this somewhere between her pleated ruffles, and it is a perfect fit for the pocket of a gent’s coat (you are travelling back to 1879 and therefore must dress the part).

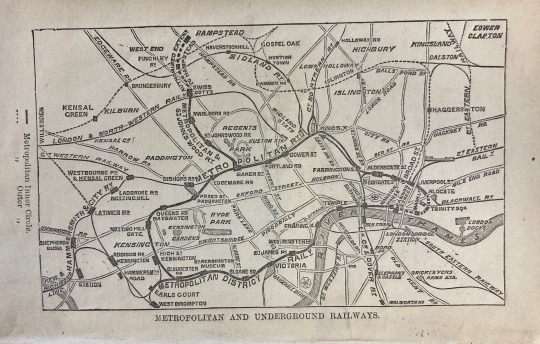

It’s yours for the tidy sum of 3/6 (if you are a UK traveller from the distant future, you are of course familiar with that denomination, which came back into circulation in the 2020s…probably). At 338 pages it packs a tight punch of information, beginning with this wonderful plan of London’s Metropolitan and Underground Railways featured on the frontispiece. It is markedly different from the Underground Map we are all familiar with, more in the shape of spaghetti than circuitry, but still valuable to those arriving in London 1879.

Before the guide proper begins, there is a handy list of subjects as introductory information.

As a librarian I am immediately interested in the list of boks about London and that is the section I turn to, enjoying a small list that includes Dickens’ Dictionary of London (read the 1882 edition on the Internet Archive.org).

Assuming that our time traveller friends are quite strange, they may wish to jump ahead to part 15, General Hints to Strangers. This part advises the best time of year to visit London 1879 are the months of May, June and July and recommends all that is available to see in the hustle and bustle of those months.

This section also includes Hints for Foreigners (come on 1879, do not disappoint me).

Murray’s Modern London tells the foreign visitor:

By the law of Great Britain all foreigners have unrestricted right of entrance and residence in this country; and while they remain in it, are equal with British subjects, under the protection of the law; nor shall they be punished except for an offence against the law, and under the sentence of the ordinary tribunals of justice, after a public trial, and on a conviction founded on evidence given in open Court.

London 1879 is unexpectedly more hospitable than one realises! Heartening! Better still is this polite advice:

Foreign money is not current in England, and an attempt to use it will expose the traveller to inconvenience.

Solid advice in any era.

The guide continues with directions on appropriate visiting hours, etiquette for lateness, dining advice and more. It ends with a very useful tip when it comes to navigating some of the streets of London:

Be on your guard about the confusion in the nomenclature of London streets; the “Post Office Directory” a few years ago recorded the existence of, in various parts of the town of 37 King-streets, 27 Queen-streets, 22 Princes-streets, and 17 Duke-streets, 35 Charles-streets, 29 John-streets, 15 James-streets, 21 George-streets.

There are of course plans and maps to help our time travellers find their way around, but there are no photographs of what awaits us in London 1879. This does not hinder one’s enjoyment of the guide one iota. It is a strangely charming little book, and one notices a distinct touch of restrained affection for the city; you can almost imagine an editorial moustache threatening to fly off a stiff upper lip from the employment of that restraint.

The guidebook is page upon page of delicious detail, be it on bridges, or markets, or churches, or parks, or breweries, water and gas companies…even sewage and drainage! There is an entire page of detail on the new drainage system of London, ending with only a small mention of the man who revamped the sewage system of London: The engineer of the Main Drainage is Sir Jos. Bazalgette.

You may think there’s simply no time to wax lyrical about Bazalgette in this guidebook which is just about the facts – there is so much to see, after all. You can think again as you turn the page and see a quote from Shakespeare’s King Richard III take up half a page in regards to the Tower of London.

Poor Bazalgette; great people really are just disregarded in their own time.

The guide moves swiftly on, taking our travellers even through the old pits of London, which have collected the bodies of the dead since plagues of old. On the topic of Bunhill (yes, as in bone hill) Fields Burial Ground, the guide mentions that 124,000 dead bodies were interred there between April 1713 and August 1852, 5000 of which were disinterred and thrown into a pit in 1874 for building purposes. A page and half is all it takes to remember that London is a city built on bones.

Speaking of which! There is an excellent portion devoted to Eminent Persons Buried In London And Its Immediate Vicinity. The usuals are there of course, kings and queens, statesmen, artists and poets. Also included are actors and actresses. Yes, lawyers too. There is also a miscellaneous section, which includes one Will Somers, Henry VIII’s jester. This modern guide is not so modern it will taint its taxonomical arrangements by suggesting a comedian might also be an actor. Also recorded are Eminent Foreigners, one of whom is Isaac Casaubon who apparently studied so hard it killed him (this may not be entirely true, but is a good excuse for not studying too hard).

There is much more to enjoy in this guide, but legal London seems like the natural place for me to realise that you get it, I really happen to like this book.

Firstly, travellers to London 1879 find themselves in the presence of the new law courts in the Strand. The courts are not quite finished and it seems there were a few obstacles to get the building started, including all masons going on strike 1877-8, forcing contractors to hire foreign workman, chiefly Germans and Italians. Mentioned also is Westminster Hall, the Old Bailey Sessions House, Clerkenwell Sessions House, and other various courts before we finally come to the Inns of Court, “the noblest nurseries of Humanity and Liberty in the kingdom.”

We are guided into the Temple area through Spenser’s words:

Those tricky brown towers

The which on Thames’ broad aged back doe ride,

Where now the studios lawyers have their bowers,

There whilom wont the Templar Knights to bide,

Till they decayed through pride.”

Beautiful! The editor’s moustache must have flown right off!

The guide mentions two places in Temple worthy of a visit; Temple Church and Temple Hall. The glowing review of Middle Temple Hall is a little bit of a bittersweet read, as we who sit in the present know of the damage suffered to the Temple area post 1879. The roof is mentioned as the best piece of Elizabethan architecture in London, and also mentioned is the renaissance style screen, which the guide vehemently denies as being made from the spoils of the Spanish Armada.

The editor’s moustache spinning out of control, the guide points out that the exterior of the hall was encased in stone in 1757, in wretched taste. Mentioned too is the very first performance of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night in Middle Temple Hall as is the use of Temple Gardens in a scene from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I.

It is also pointed out that a re-enactment of said scene in the gardens would be impossible in London 1879 for such is the smoke and foul air of London, that the commonest and hardiest kind of rose has long ceased to put forth a bud in the Temple Gardens.

To complain about London is just another way to love London, eh Editor?

London, as viewed through this guide, is a composite of many histories and many sights, set out here in fine detail. There is so much on offer, so much to see, and this guide offers an array of interesting stats and facts to entice the visitor. I cannot imagine that our time travellers did not enjoy Murray’s modern London, in spite of its foul air.

___________________________________

Harpreet Dhillon

Deputy Librarian

#london tour#london history#london#19th century#mtlibrary#libraries#librarians#middle temple library#inns of court#victorian era#victorian#rarebook#rare books#library#bookshelf#books and reading#history#london collection

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

🏴 The very first underground station Baker Street now and then.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

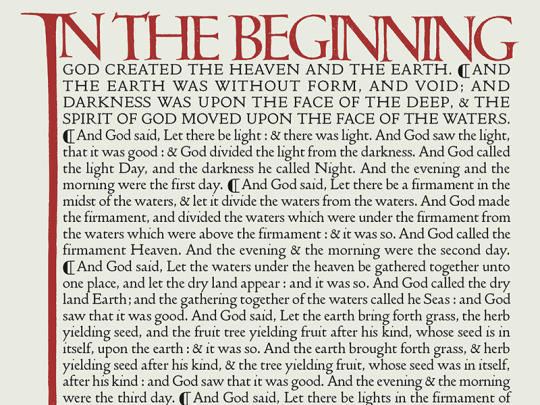

The Doves Type was a typeface created by T.J. Cobden-Sanderson and Emery Walker of The Doves Press, founded in 1900. When the partnership was eventually dissolved in 1909 after a bitter dispute, ownership of the Dove Type was appointed to Cobden-Sanderson, whereupon his death the ownership would pass to Walker.

Rather than let this happen, Cobden-Smith began to dispose of the type matrices into the River Thames off Hammersmith Bridge. Cobden-Sanderson wrote in his personal journals that he "bequeathed to the river" the type itself. Beginning in 1916, under the cloak of midnight, Cobden-Sanderson began the slow task of disposing of Doves into the river. He said that he completed the task in January 1917 after 170 trips in total to the bridge.

Over 150 pieces of the typeface were recovered from the riverbed by Robert Green in 2014, with the help of the Port of London Authority and the acquisition of a mudlarking license.

#doves type#doves font#typology#edwardian#edwardian era#edwardian london#mudlarking#mudlark#archaeology#history#london#london history#river thames#thames river#thames#british history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got bored, took a drive (pandemic edition): We drove 3.5 hours halfway across Arizona just to see this bridge. A rich guy in 1964 bought the London Bridge, from the original London, and had it reconstructed in Lake Havasu City, Arizona.

May 2020

#london bridge#arizona#travel#bridge#original photography#road trip#got bored#explore#photographers on tumblr#history#american history#london history#got bored took a drive#wanderingjana#photography

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Does Big Ben look impressive in person?

Anookie,

See I love these questions, Big Ben is the bell inside the clock tower, not the tower, that got renamed back in 2012 to Elizabeth Tower for the Jubilee.

Now the tower stands at around 319 feet tall and 40 feet from corner to corner..

It took 15 years to build it!

Endured WW2 with only a minimum amount of damage (I say that but hey, there was a lot worse done look at Saint Paul's cathedral)

But, oh boy, yes it's big and impressive almost scary in a way.

Now doesn't matter if it's called Big Ben or Elizabeth Tower it's daunting just standing there looking up marveling at the architecture of the building itself.

Now I'm not sure if it's the size or the history that makes it so imposing.

From King Charles 2nd, Queen Victoria to Guy Fawkes and it's almost scary to think so much has changed the history of such a building.

but I love visiting London whilst Travelling home to Portsmouth.. the sights, sounds, accents, and diversity are all in one city.

Here's a photo of back in 2022 when I last headed home.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ragged and Industrial School established for poor and destitute children in Victorian London. Looks fancy now.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A mini skirt is always a perfect gift for people who own Mini Coopers and Mini Coopers who have become sentient!🏴

🚙🇬🇧🚙

#history#mini skirt#fashion#mary quant#youth culture#london history#historical figures#mini cooper#king’s road#united kingdom#fashion history#coquette#girly things#barbiecore#clothing#womens history#soft girl#historical women#bimbocore#bubblegum bitch#femininity#english history#london#1960s#coquette style#dollette#clothing history#nickys facts

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

At J.Kelly, Pie & Mash, Bethnal Green

Photo, Tony Bock.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bond Street, London, 1890s. A poulterer is a poultry and game merchant.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Squalor to Sanitation & A History of London

Squalor to Sanitation

With our Squalor to Sanitation exhibition drawing to a close, it seems like a good opportunity to recap and re-share, whilst highlighting another great item from our London Collection.

This was an interesting exhibition, looking at public health disasters in terms of the responses to those disasters and the conditions that led to the disasters themselves. The overarching take from the exhibition is probably an expected one; negligent attitudes towards environmental factors play key roles in cases of public health endangerment. Where there is squalor, population density, lack of hygiene, and poverty, there you find conditions for disease and disaster to germinate.

The exhibition focused primarily on London, looking at events as far back as the plague. Again and again the main cause of disease and disaster were unattended to plainly ignored environmental factors that became perfect catalysts to spread disease, fire, or stench.

The city moved on from plague and fire in 1666, rebuilding and renewing itself. It would grow and prosper thanks to industrialisation and migration, the population exceeding 1 million by the end of the 18th century. But though London was thriving and laying down foundations to become a business capital globally, the situation for the poor only seemed to worsen.

The slums were overcrowded and disease ridden and poverty was rife. It seems not much was done for the poor in the 18th century, but effort was certainly made to adjust the city infrastructure in order to ease the path for trading and business. One such effort was the removal of the seven ancient gates of London to ease congestion in the city, allowing for better flow of traffic.

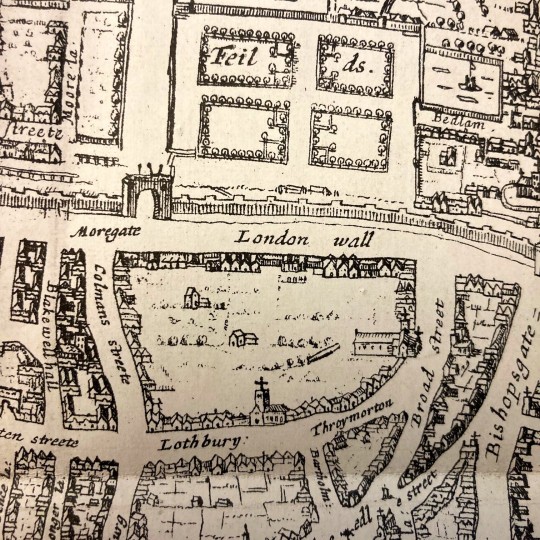

These seven gates were built into the London Wall which once surrounded the city as a defensive measure, standing since Roman times and erected to oversee safe passage into the city. They are also feature in a map entitled The Cittie of London.

A History of London by W.J. Loftie (which you can access online via HathiTrust) is a two volume set published in 1883, looking at London's history since medieval times. One of the most enjoyable features of this work is the heavy inclusion of maps and illustrations detailing the changing face of the city. Looking at the maps you really do get a sense that London really has been through it.

Unfortunately, we could not include this work in the exhibition. Sometimes works simply do not fit the narrative, or in this case, literally do not fit the case. The map itself is quite contentious too, attributed to an engraver by the name of Augustine Ryther and dated to 1604.

Ryther died in 1593, which makes his cartographical efforts all the more remarkable. Or potentially the wrong person was attributed for this map, or perhaps there’s some error too in the dating of the map. And perhaps…there may be other inaccuracies also in regards to the content.

Despite knowing that this map has some inaccuracies related to it and potentially parts of it may be imaginatively rendered, the map seems accurate enough when it comes to some details. For our purposes, this would have been a great item to display as a visual aid on some of the topics discussed in our exhibition.

One such topic is the Embankment. One of the public health disasters we looked at was The Great Stink. A change that came about as a result of the Stink was a renewed and robust sewage system (which is still in use), amongst other infrastructural changes beneath the city to accommodate the safe removal of sewage. This involved the addition of new tunnels beneath the city and in order to facilitate these new additions the Thames Embankment was widened.

Ryther’s The Cittie of London illustrates how the Thames Embankment once looked, and of interest to the curators of this exhibition was seeing how the embankment edge once came right up against the grounds of the Inn. This would have been the case right up until 1862, when the river’s waters were still close enough for the then librarians to be able to throw breadcrumbs to the ducks below (allegedly – there is also some doubt to this story). In 1604 (the date on this map, also not to be trusted), one would have been able to walk down the Temple stairs to be ferried away down the river.

As maps go, it’s an incredibly enjoyable one. Names like Aldgate, Bishopsgate, Moorgate, Cripplegate, Aldersgate, Newgate, Ludgate are not unknown words to the present Londoner. We all recognise these names, though some of us may not be aware of their history. We walk through Ludgate and Newgate. We catch trains at Moorgate and Aldgate. We have a sense of these names reaching back into the past, despite not knowing their full stories.

To see them on a map which places them in context with the gates they are derived from is thoroughly exciting. It brings the past directly in contact with the present. How ironic it is that those gates were removed to ease congestion in the city and now many of us spend time stuck in trains in tunnels beneath the city directly under those long gone gates (with varied degrees of success when it comes to that ease of access).

Loftie’s A History of London sadly did not make the cut for the exhibition, but in some regards it may have been as useful as displaying a map of Narnia (Fleet Street still isn’t as wide as it is drawn on The Cittie of London). However, at the same time it’s not completely lacking in truth and makes for a great snapshot of a city that once was.

If you would like to see A Cittie of London in closer details, Yale University Library has an online copy for perusal.

If you would like to read more about Squalor to Sanitation, please do visit the online exhibition @ https://www.juncture-digital.org/middletemplelibrary/squalor-to-sanitation/

#london#books#maps#squalor to sanitation#london collection#middle temple library#london history#embankment

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON THIS DAY:

150 years ago (23 August 1873), the Albert Bridge, which connects Chelsea to Battersea, was opened for the first time.

Here it is depicted by the Illustrated London News, 30 August 1873.

—

Albert Bridge is a road bridge over the River Thames connecting Chelsea in Central London on the north bank to Battersea on the south.

Designed and built by Rowland Mason Ordish in 1873 as an Ordish–Lefeuvre system modified cable-stayed bridge, it proved to be structurally unsound.

Between 1884 and 1887, Sir Joseph Bazalgette incorporated some of the design elements of a suspension bridge.

In 1973, the Greater London Council added two concrete piers, which transformed the central span into a simple beam bridge.

As a result, the bridge is an unusual hybrid of three different design styles. It is an English Heritage Grade II* listed building.

#Engineering History#London History#Albert Bridge#Chelsea#Battersea#Illustrated London News#Rowland Mason Ordish#Sir Joseph Bazalgette#Greater London Council

6 notes

·

View notes