#loyola jesuit center

Photo

#stations of the cross#portland#sculpture#plexiglass#photographers on tumblr#textless#amadee ricketts#loyola jesuit center#phone#reflection#some of the figures are missing their heads#which probably explains the plexiglass#spiderweb#texture#shrine#mary#tree#sign#letters#stations#green

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

[From Norton] We were in a church in Barcelona and Marin said, “Dad, this is about three of your favorite things: churches, art, and history.” Yep. I’ve tried not to overdo those three things too much on this trip, but it’s hard not to in the places we’ve been. A few highlights of sacred places we’ve visited:

1. Familia Sagrada in Barcelona: no words for how creative and beautiful and sacred this church is. It’s not like all the other cathedrals in Europe. It really is a sight to behold. Or more accurately, to experience. Every single detail tells a story about Jesus.

2. Montserrat: the mountain Benedictine monastery. I am drawn to the Benedictine tradition, so it was good to visit this famous monastery. This is also the place where, in 1522, a young Spanish soldier spent three days confessing his sins and giving his life to doing the work of Jesus. His conversion was so radical that he laid down his sword at the altar and left it there. His name was Ignatius of Loyola and after his time at Montserrat he began to form what became known as the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits).

3. Nimes Maison Carree (Roman Temple): this is the best preserved Roman temple from the ancient world. It was built in 2-5 AD (when Jesus was a little boy). It was built to honor Caesar Augustus. It included an outer court and massive altar where sacrifices were offered to the Roman gods and Caesar was declared Lord. This is what historians call the Imperial Cult. A few blocks away stands the Nimes arena which is the best preserved Roman arena and the site of gladiator games and Christian persecution. While these two places are not “sacred” in the normal sense, they are reminders of the Roman world in which early followers of Jesus declared a radically different allegiance.

4. Avignon Palace of the Popes: also not a “sacred place” but very, very important historically. Many years ago I learned about the “Babylonian captivity of the Popes” — a time in the 1300s when French popes broke with tradition and moved the papacy away from Rome to Avignon, France. It had little to do with religion or faith and was all about power and politics. Italian cardinals then elected their own popes and there were all kinds of Middle Ages controversies about the rival popes. Today, we visited the massive Palace of the Popes in Avignon. It was so impressive. Less like a palace and more like a fortress. The walls were 10 feet thick. At one level, this time of papal history is embarrassing because of its politics, corruption, etc. One another level, the artistic and architectural achievements are still breathtaking.

One final comment, for now (there are more churches we’re visiting). The church was the center of artistic creativity during this time. I wish it were still that way today. And followers of Jesus created art and architecture that would last for centuries. It sometimes took decades or centuries to complete. Sagrada Familia is still being constructed. Gaudi (its designer) gave 40 years of his life to this project and even then knew it would not be complete before he died. What a long-term investment. So different from our time and culture where we rarely invest in anything beyond a few minutes, days, or weeks.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

OPPENHEIMER: A Lesson on Presuppositions

Beware of condemning any man’s action. Consider your neighbor’s intention, which is often honest and innocent, even though his act seems bad in outward appearance. - St. Ignatius of Loyola.

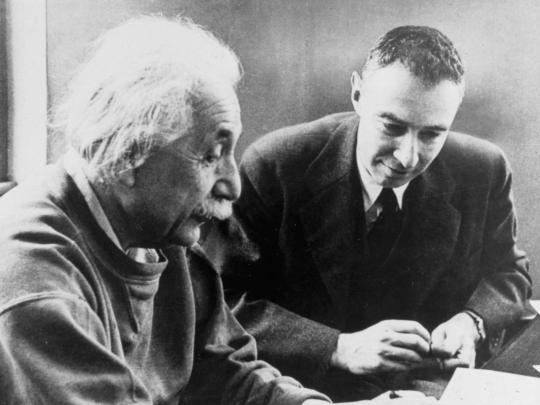

I finally saw the movie Oppenheimer and it was amazing. Director Christopher Nolan stand out as someone who can take a subject matter, in this case the historical development of the Atomic bomb and the early policy disputes regarding the Atomic Energy Program, and imbue it with a powerful ethical consideration. Throughout the movie you journey with the struggle that Oppeheimer has with Lewis Strauss and by the end you are forced to reflect and re-evaluate how we all make unfortunate judgements on others based on assumptions we place on who they are or what they say and do.

The movie was based on the way that Lewis Strauss (played by Robert Downey Jr.) went out of his way to discredit Robert Oppenheimer (played by Cillian Murphy) and to remove his influence from the world of atomic energy policy making. In the movie, Strauss’ motive is very personal and narcissistic. He was convinced that Oppenheimer had turned the scientific community against him. At the center of that assumption is a brief conversation that takes place by a lake in Princeton between Oppenheimer and Einstein. After the conversation Strauss comes by and greets Einstein who seems to snub him. From this unfortunate event Strauss begins to pursue vengence against Oppenheimer.

The black and white portion of the movie depicts the Senate hearing for the cabinet nomination of Lewis Strauss in 1959, after the events that take place with Oppenheimer. During this process it becomes clear that Strauss orchestrated the persecution of Oppenheimer and because of this he losses the cabinet nomination. This infuriates Strauss even further feeling that somehow Oppenheimer continues to influence others against him. The Senate aide (played by Alden Ehreneich), after recognizing Strauss’ anger and jealousy, suggest that he truly does not know what was said during the conversation between Einstein and Oppenheimer and that it may be possible it had nothing to do with him. This is when we hear the actual dialogue between Oppenheimer and Einstein.

The discussion was based on the fear that shared by many, while it was an important goal to get the bomb before the Nazi’s built there own, it was also feared that such a powerful weapon could not be controlled. One scientific concern was that the bomb would start a chain reaction of explosions that would not end, resulting in the destruction of Earth’s atmosphere. This fortunately did not happen. But later Oppenheimer recognized that what he had started was a political chain reaction that could also lead to a nuclear holocaust. This, he told Einstein, is what he believed he unfortunately accomplished. This would give anyone a moment of pause as they reflect on their new social reality in light of the massive destruction their science has brougt forth. This explains Einstein’s somber and contemplative mood as he walks past Strauss. Strauss however assumes a personal attack and begins to plot against Oppenheimer, to the detriment of the global community who will loose out from Oppenheimer’s caution regarding nuclear policy.

The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola warn us against making negative presuppositions on others. There is a great and practical spiritual wisdom from the Ignatian tradition. St. Ignatius knew that his missionaries would encounter new people and experience new cultural norms that could allow for the missionary community to misinterpret those they would encounter. There would be plenty of unfortunate opportunities to make personal and negative assumptions. Ignatius trained those who would be formed by Jesuit spirituality to always keep an open mind and to never assume a negative interpretation to how they experienced others. Fr. James Martin tells us:

The Presupposition steers you away from anger and so provides the other person with the emotional space needed to meet you on more peaceful territory. It may even invite him or her to change... The Presupposition also helps you stay open to change, growth, and forgiveness. (Martin, pg. 236)

The Presuppositions are a lesson we should all take some time to reflect on. The great contribution of this movie is to see how this Ignatian wisdom played out in the dynamic between Oppenheimer, Einstein and Strauss. A single event that then, unintentionally, led to an unfortunate series of events because of a false assumption based and a negative interpretation. And because of this we continue to live with the consequences of a nuclear arms race that threatens the existence of mankind.

0 notes

Text

The secret of the Vatican behind the 7 Seals. Who do all the Elites of society serve?

The Vatican is a closed mini-state with a population of about 2,000 people. Since time immemorial, it has been shrouded in legends and myths. It is known that Paul V created secret archives that are still active today. Access to the repository is strictly limited, and only officials and scientists can get there by special invitation. Every major government organization must have a secret service to ensure its security.

The Vatican, the spiritual capital of all Catholics in the world, is no exception. It is believed that its archives contain answers to all the riddles of the modern world. Agents of the Holy See actively influence world politics. There is no shortage of questions either. For example, why do the priests of the Church need a telescope called "Lucifer"? Is it true that the Vatican helped Nazi Germany, helped organize the revolution in Russia? And what is the Vatican hiding? Also, on October 28, 2019 in Colosseum, which is famous for the martyrdom of Christians, a satanic statue of Moloch, the infamous god associated with sacrifices, has been installed.

The official explanation is this: The statue of Moloch, worshiped by the Canaanites, is part of an exhibition dedicated to the once great rival city of Carthage. The large-scale exhibition "Carthage: an immortal legend" will run until March 29, 2020. To welcome visitors to the exhibition, which coincided with the closing ceremony of the Synod, a recreation of Moloch, a fearsome god associated with the Phoenician and Carthaginian religions, was installed at the entrance to the Colosseum.

The installation of the statue also coincided with Halloween on October 31 and All Saints' Day, which has its roots in the pagan holiday of Samhain. And again the question arises: the statue was made of hollow bronze as a set for the film "Caberia" in 1914.

In one of the scenes of the movie, the priests are shown using the statue. The film was directed by the Italian director Giovanni Patrone, who was interested in the purely technical aspects of the subject. However, in creating the script and texts of priestly chants, he was assisted by Count Gabriel de Anonsa, Duke of Montinevos, Duke of Gale, a 33rd degree Freemason.

One of the movie's most shocking scenes is the giant temple of Moloch, depicted with a giant three-eyed head of the manifold as the entrance to the infamous temple. In the footage of the film, hundreds of small children can be seen ready to die as victims of the evil god Moloch. And in this temple, full of occultists, we see a huge seated statue of the winged god Moloch, displayed in front of the entrance to the Colosseum on the dark side. Here we begin to understand who the Vatican really serves, and a little later we will confirm this with a few more facts.

One of the main orders of the Vatican is the Order of the Jesuits. This order is behind the falsification of world history, the destruction and concealment of authentic Vatican writings and ancient artifacts.

The Jesuits actively collaborated with the Nazi regime during World War II and managed to protect more than a third of Nazi criminals from punishment after the end of the war. Schellenberg, head of the Security Service, noted in his memoirs that Himmler had a better and larger collection of books than this vast literature.

Therefore, he organized the SS in accordance with the principles of the Jesuit order. In doing so, he used the charter of the order and the works of Ignatius Loyola. The highest law was absolute obedience, unconditional obedience to any order. Himmler himself was a General of the Order in his capacity as Reichsführer-SS. The leadership structure was similar to the hierarchical system of the Catholic Church. The Vatican was not only the center of Catholicism, but also the residence of the high priests of an incomprehensible satanic sect that worshiped Lucifer.

The Irish Jesuit Junior Martin, in particular, wrote repeatedly on this subject. Since he did not accept the decision of the Council and remained faithful to the Catholic tradition, in 1965 he left the Jesuit order and ceased his ministry. In his books, he laid out everything he knew, describing in detail the process by which Freemasonry infiltrated the Vatican and took control of the Church, which led to the decline of Christian doctrine and the perversion of morality and ethics.

As we have seen, the Vatican fell under the power of Satanists already in the 1960s, and this is precisely what the active ecumenical activity of globalists in recent decades is connected with, set out in their plan to establish a new world order that will lead to the unification of all religions in a single globalist Church of Satan. This allows you to see that the Vatican is a religious ideological center,

As self-taught as Pope was, his addiction to dark structures was so strong that he consistently followed a predetermined course. He not only gave up the crown, but also left the underworld. The pope also changed the papal cross. He was the first to use a scepter with a twisted cross and a distorted figure of Christ.

Such crosses were used by medieval black magicians to depict the mark of the biblical beast and are considered by scientists as an ancient satanic symbol. It was revived by Paul VI and passed on to successive popes, including Francis.

The Auditorium of the Vatican, known as the Auditorium of Paul VI, built for the Pope in 1964-1971 by the architect Pierre, also has sinister imagery. The monolithic reinforced concrete building with sulfur arches was intended for general audiences of the Pope and other public events.

It is interesting that the stage with the papal throne is still located on the territory of the Vatican, and the main part of the hall is on the territory of Italy. The latter, however, has an extraterritorial status. The Paul VI Hall, also known as the Papal Audience Hall is devoid of Christian symbols; the curvilinear shape of its vault resembles the snout of a snake.

As already mentioned, the ecumenical activity of the Vatican is aimed at the implementation of one of the necessary elements of the new world order - the creation of one world religion - Satanic. All this is described in detail by former British intelligence officer John Colliman in his book The Committee of 300.

A key role in the financial prosperity of Catholicism was played by the Vatican Bank - a closed financial institution that regulated the flow of money to the church. Its history began in the second quarter of the 20th century with donations from all over Europe, including Italy and Germany under Mussolini and Hitler.

A large amount of funds was placed by the Vatican in the banks of Europe. However, the outbreak of World War II could lead to the confiscation of accounts associated with one side or another. It was at this point that the idea of creating the Vatican Bank came to the papal financial advisers.

The new financial institution was named the Institute of Religious Affairs, outside Italian jurisdiction, which ensured complete anonymity for all depositors, including, according to experts, the Italian mafia. The money received by the Church from investments around the world was no exception.

This anonymity continues to this day. Once the money is invested, it is almost impossible to trace it. Many Italian Catholics with ties to Italian businessmen are keen to maintain bank secrecy.

Thus, the Institute of Religious Affairs organizes financial flows in previously unknown volumes, avoiding taxes and allowing top church leaders to calmly talk about low incomes. The disclosure of the Institute's actual financial transactions would be another blow that could directly affect the amount of donations collected from congregations around the world.

On May 14, 2014, the Pope announced that he was ready to baptize aliens if they came to the Vatican. He also said: Who are we to close our doors to anyone, even Martians?

We come to the following conclusion: the world is preparing for an alien contact, but, most likely, not with aliens, but with demons disguised as guests from outer space.

Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Lenten Prayer

By Andrew Mountin, Director of Music and Liturgy

Fairfield University Campus Ministry

Loving God,

During this Holy Season of Lent,

help us draw nearer to you and to one another.

Especially in these days of illness and distance,

remind us that we are called to love and lift each other up.

As we pray, grant us the grace to trust in you.

Walk with us on this Lenten journey

as we strive to live holy and just lives.

As we fast, instill in us the wisdom to recognize

that our fasting calls us into solidarity

with those in our community who go without.

Give us the courage to be your presence to all who we encounter,

the conviction to proclaim our faith in troubled times,

and the compassion to reach out in love to anyone in need.

As we give alms, grant us humble hearts to realize

that all we have comes from others, and ultimately from you.

Remind us to maintain a spirit of gratitude and respect

as we offer up to you all that we give to one another.

Through this Lenten season, let our actions be shaped

by our desire to live more fully the call of discipleship.

Amen.

Ash Wednesday marks the beginning of the holy season of Lent, a forty-day pilgrimage toward Easter, marked by a renewed spiritual focus and intensity. We invite you to join us as we journey in the darkness and uncertainty of our present time, toward the light of the Risen Christ.

Below are links to Fairfield University’s Campus Ministry Lenten Series, and to other spiritual resources provided by the larger Ignatian and Catholic family:

Fairfield University Campus Ministry Liturgy Schedule

Lenten Series: Thursday nights at 7:00 PM

Location – Egan Chapel, and also available on Zoom

February 25th – Prayer (Fr. John Murray, S.J.)

March 4th – Lent from a different lens (Fr. Gerry Blaszczak, S.J.)

March 11th – Almsgiving (Fr. Michael Tunney, S.J.)

March 18th – Fasting (Fr. Paul Rourke, S.J.)

March 25th – Lenten Reconciliation Service

*Zoom link for Lenten Series: https://Fairfield.zoom.us/j/94380391254

The Murphy Center for Ignatian Spirituality – Learn more about all the programs offered by the Murphy Center here!

An Ignatian Guide to Lent: 40 Days of Ignatian Spirituality – Learn more and sign up here.

Lent 2021 - Steadfast: A Call to Love - Offered by the Ignatian Solidarity Network. Learn more and sign up here.

Daily reflections, prayers, presentations and more are available from our fellow Jesuit schools, Creighton University and Xavier University, as well as Loyola Press and the Diocese of Bridgeport’s Leadership Institute.

1 note

·

View note

Text

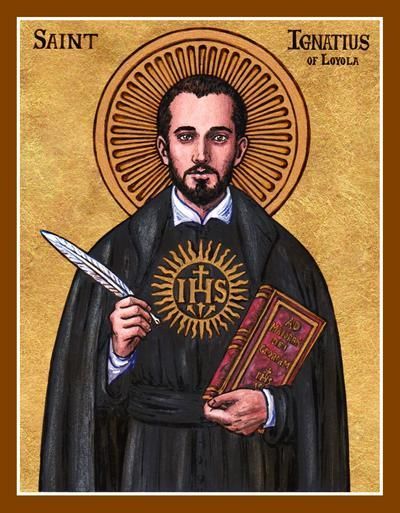

July 31 is the feast day of St. Ignatius of Loyola, priest

Source of picture: Theophilia on DeviantArt

Life of St. Ignatius of Loyola

The founder of the Jesuits was on his way to military fame and fortune when a cannon ball shattered his leg. Because there were no books of romance on hand during his convalescence, Ignatius whiled away the time reading a life of Christ and lives of the saints. His conscience was deeply touched, and a long, painful turning to Christ began. Having seen the Mother of God in a vision, he made a pilgrimage to her shrine at Montserrat near Barcelona. He remained for almost a year at nearby Manresa, sometimes with the Dominicans, sometimes in a pauper’s hospice, often in a cave in the hills praying. After a period of great peace of mind, he went through a harrowing trial of scruples. There was no comfort in anything—prayer, fasting, sacraments, penance. At length, his peace of mind returned.

It was during this year of conversion that Ignatius began to write down material that later became his greatest work, the Spiritual Exercises.

He finally achieved his purpose of going to the Holy Land, but could not remain, as he planned, because of the hostility of the Turks. Ignatius spent the next 11 years in various European universities, studying with great difficulty, beginning almost as a child. Like many others, his orthodoxy was questioned; Ignatius was twice jailed for brief periods.

Source of picture: www.ignatiusmovie.com

In 1534, at the age of 43, he and six others — one of whom was Saint Francis Xavier — vowed to live in poverty and chastity and to go to the Holy Land. If this became impossible, they vowed to offer themselves to the apostolic service of the pope. The latter became the only choice. Four years later Ignatius made the association permanent. The new Society of Jesus was approved by Pope Paul III, and Ignatius was elected to serve as the first general.

Ignatius was a true mystic. He centered his spiritual life on the essential foundations of Christianity — the Trinity, Christ, the Eucharist. His spirituality is expressed in the Jesuit motto, Ad majorem Dei gloriam — “for the greater glory of God.”

Source: https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-ignatius-of-loyola/

Quotes from St. Ignatius of Loyola

Source of picture: https://artyzm.com

"He who carries God in his heart bears Heaven with him wherever he goes."

"Speak little, listen much."

"It is dangerous to make everybody go forward by the same road: and worse to measure others by oneself."

#saints#quotes#St. Ignatius of Loyola#priest#God#Christ#Jesus#Jesus Christ#Holy Spirit#Holy Trinity#Father#Son#christian religion#faith#hope#love#who carries God in his heart bears Heaven with him wherever he goes#speak little#dangerous to make everybody go forward by the same road#worse to measure others by oneself#each day pray not for good things

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Elie, How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?, New Yorker (June 15, 2020)

She has become an icon of American letters. Now readers are reckoning with another side of her legacy.

A habit of bigotry, most apparent in her juvenilia, persisted throughout her life.

In 1943, eighteen-year-old Mary Flannery O’Connor went north on a summer trip. Growing up in Georgia—she spent her childhood in Savannah, and went to high school in Milledgeville—she saw herself as a writer and artist in the making. She created illustrated books “too old for children and too young for grown-ups” and dryly titled an assemblage of her poems “The Priceless Works of M. F. O’Connor”; she drew cartoons and submitted them to magazines, noting that her hobby was “collecting rejection slips.”

On her travels, she and two cousins visited Manhattan: Chinatown, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and Columbia University. Then they went to Massachusetts, and visited Radcliffe, where one cousin was a student. O’Connor disliked both schools, and said so in letters and postcards to her mother. (Her father had died two years earlier.) Back in Milledgeville, O’Connor studied at the state women’s college (“the institution of higher larning across the road”). In 1945, she made her next trip north, enrolling in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she dropped the Mary (it put her in mind of “an Irish washwoman”) and became Flannery O’Connor.

Less than two decades later, she died, in Milledgeville, of lupus. She was thirty-nine, the author of two novels and a book of stories. A brief obituary in the Times called her “one of the nation’s most promising writers.” Some of her readers dismissed her as a “regional writer”; many didn’t know she was a woman.

We are still learning who Flannery O’Connor was. The materials of her life story have surfaced gradually: essays in 1969, letters in 1979, an annotated Library of America volume in 1988, and a cache of personal items deposited at Emory University in 2012, which yielded the “Prayer Journal,” jottings on faith and fiction from her time at Iowa. Each phase has deepened the portrait of the artist and furthered her reputation. Southerners, women, Catholics, and M.F.A.-program instructors now approach her with devotion. We call her Flannery; we see her as a wise elder, a literary saint, poised for revelation at a typewriter set up on the ground floor of a farmhouse near Milledgeville because treatments for lupus left her unable to climb stairs.

O’Connor is now as canonical as Faulkner and Welty. More than a great writer, she’s a cultural figure: a funny lady in a straw hat, puttering among peacocks, on crutches she likened to “flying buttresses.” The farmhouse is open for tours; her visage is on a stamp. A recent book of previously unpublished correspondence, “Good Things Out of Nazareth” (Convergent), and a documentary, “Flannery: The Storied Life of the Writer from Georgia,” suggest a completed arc, situating her at the literary center where she might have been all along.

The arc is not complete, however. Those letters and postcards she sent home from the North in 1943 were made available to scholars only in 2014, and they show O’Connor as a bigoted young woman. In Massachusetts, she was disturbed by the presence of an African-American student in her cousin’s class; in Manhattan, she sat between her two cousins on the subway lest she have to sit next to people of color. The sight of white students and black students at Columbia sitting side by side and using the same rest rooms repulsed her.

It’s not fair to judge a writer by her juvenilia. But, as she developed into a keenly self-aware writer, the habit of bigotry persisted in her letters—in jokes, asides, and a steady use of the word “nigger.” For half a century, the particulars have been held close by executors, smoothed over by editors, and justified by exegetes, as if to save O’Connor from herself. Unlike, say, the struggle over Philip Larkin, whose coarse, chauvinistic letters are at odds with his lapidary poetry, it’s not about protecting the work from the author; it’s about protecting an author who is now as beloved as her stories.

The work largely deserves the love it gets. O’Connor’s fiction is full of scenarios that now have the feel of mid-century myths: an evangelist preaching the gospel of a Church Without Christ outside a movie house; a grandmother shot by an escaped convict at the roadside; a Bible salesman seducing a female “interleckshul” in a hayloft and taking her wooden leg. The late story “Parker’s Back,” from 1964, in which a tattooed ex-sailor tries to appease his puritanical wife by getting a life-size face of Christ inked onto his back, is a summa of O’Connor’s effects. There’s outlandish naming (Obadiah Elihue Parker), blunt characterization (“The skin on her face was thin and drawn as tight as the skin on an onion and her eyes were gray and sharp like the points of two icepicks”), and pungent speech (“Mr. Parker . . . You’re a walking panner-rammer!”). There’s the way the action hurtles to an end both comic and profound, and the sense, as she put it in an essay, “that something is going on here that counts.” There’s the attractive-repulsive force of religion, as Parker submits to the tattooer’s needle in the hope of making himself a holy image of Christ. And there’s a preoccupation with human skin, and skin coloring, as a locus of conflict.

O’Connor defined herself as a novelist, but many readers now come to her through her essays and letters, and the core truth to emerge from the expansion of her body of work is that the nonfiction is as strong and strange as the fiction. The 1969 book of essays, “Mystery and Manners,” is both an astute manual on the craft of writing and a statement of precepts for the religious artist; the 1979 book of letters, “The Habit of Being,” is bedside reading as wisdom literature, at once companionable and full of barbed, contrarian insights. That they are books was part of O’Connor’s design. She made carbon copies of her letters with publication in mind: fearing that lupus would cut her life short, as it had her father’s, she used the letters and essays to shape the posthumous interpretation of her fiction.

Even much of the material left out of those books is tart and epigrammatic. Here is O’Connor, fresh from Iowa, on what a writing program can do for a writer:

It can put him in the way of experienced writers and literary critics, people who are usually able to tell him after not too long a time whether he should go on writing or enroll immediately in the School of Dentistry.

Here she is on life in Milledgeville, from a 1948 letter to the director of Yaddo, the writers’ colony in upstate New York:

Lately we have been treated to some parades by the Ku Klux Klan. . . . The Grand Dragon and the Grand Cyclops were down from Atlanta and both made big speeches on the Court House square while hundreds of men stamped and hollered inside sheets. It’s too hot to burn a fiery cross, so they bring a portable one made with electric light bulbs.

On her first encounter, in 1956, with the scholar William Sessions:

He arrived promptly at 3:30, talking, talked his way across the grass and up the steps and into a chair and continued talking from that position without pause, break, breath, or gulp until 4:50. At 4:50 he departed to go to Mass (Ascension Thursday) but declared he would like to return after it so I thereupon invited him to supper with us. 5:50 brings him back, still talking, and bearing a sack of ice cream and cake to the meal. He then talked until supper but at that point he met a little head wind in the form of my mother, who is also a talker. Her stories have a non-stop quality, but every now and then she does have to refuel and every time she came down, he went up.

Reviewers of O’Connor’s fiction were vexed by her characters’ lack of interiority. Admirers of the nonfiction have reversed the charge, taking up the idea that the most vivid character in her work is Flannery O’Connor. The new film adroitly introduces the author-as-character. The directors—Mark Bosco, a Jesuit priest who teaches a course on O’Connor at Georgetown, and Elizabeth Coffman, who teaches film at Loyola University Chicago—draw on a full spread of archival material and documentary effects. The actress Mary Steenburgen reads passages from the letters; several stories are animated, with an eye to O’Connor’s adage that “to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” There’s a clip from John Huston’s 1979 film of her singular first novel, “Wise Blood,” which she wrote at Yaddo and in Connecticut before the onset of lupus forced her to return home. Erik Langkjaer, a publishing sales rep O’Connor fell in love with, describes their drives in the country. Alice Walker tells of living “across the way” from the farmhouse during her teens, not knowing that a writer lived there: “It was one of my brothers who took milk from her place to the creamery in town. When we drove into Milledgeville, the cows that we saw on the hillside going into town would have been the cows of the O’Connors.”

In May, 1955, O’Connor went to New York to promote her story collection, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” on TV. The rare footage of O’Connor lights up the documentary. She sits, very still, in a velvet-trimmed black dress; her accent is strong, her demeanor assured. “I understand you are living on a farm,” the host prompts. “Yes,” she says. “I only live on one, though. I don’t see much of it. I’m a writer, and I farm from the rocking chair.” He asks her if she is a regional writer, and she replies:

I think that to overcome regionalism, you must have a great deal of self-knowledge. I think that to know yourself is to know your region, and that it’s also to know the world, and in a sense, paradoxically, it’s also to be an exile from that world. So that you have a great deal of detachment.

That is a profound and stringent definition of the writer’s calling. It locates the writer’s art in the refinement of her character: the struggle to overcome an outlook that is an obstacle to a greater good, the letting go of the comforts of home. And it recognizes that detachment can leave the writer alone and apart.

At Iowa and in Connecticut, O’Connor had begun to read European fiction and philosophy, and her work, old-time in its particulars, is shot through with contemporary thought: Gabriel Marcel’s Christian existentialism, Martin Buber’s sense of “the eclipse of God.” She saw herself as “a Catholic peculiarly possessed of the modern consciousness” and saw the South as “Christ-haunted.”

All this can suggest points of similarity with Martin Luther King, Jr., another Georgian who was infused with Continental ideas up north and then returned south to take up a brief, urgent calling. Born four years apart, they grasped the Bible’s pertinence to current events, and saw religion as the tie that bound blacks and whites—as in her second novel, “The Violent Bear It Away,” from 1960, which opens with a black farmer giving a white preacher a Christian burial. O’Connor and King shared a gift for the convention-upending gesture, as in her story “The Enduring Chill,” in which a white man tries to affirm equality with the black workers on his mother’s farm by smoking cigarettes with them in the barn.

O’Connor lectured in a dozen states and often went to Atlanta to visit her doctors; she saw plenty of the changing South. That’s clear from her 1961 story “Everything That Rises Must Converge.” (The title alludes to a thesis advanced by the French Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who saw the world as gradually “divinized” by human activity in a kind of upward spiral.) A white man, living at home after college, takes his mother to “reducing class” on a newly integrated city bus. The sight of an African-American woman wearing the same style of hat that his mother is wearing stirs him to reflect on all that joins them. The sight of a black boy in the woman’s company prompts his mother to give the boy a gift: a penny with Lincoln’s profile on it. Things get grim after that.

The story was published in “Best American Short Stories” and won an O. Henry Prize in 1963. O’Connor declared that it was all she had to say on “That Issue.” It wasn’t. In May, 1964, she wrote to her friend Maryat Lee, a playwright who was born in Tennessee, lived in New York, and was ardent for civil rights:

About the Negroes, the kind I don’t like is the philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind, the James Baldwin kind. Very ignorant but never silent. Baldwin can tell us what it feels like to be a Negro in Harlem but he tries to tell us everything else too. M. L. King I dont think is the ages great saint but he’s at least doing what he can do & has to do. Don’t know anything about Ossie Davis except that you like him but you probably like them all. My question is usually would this person be endurable if white. If Baldwin were white nobody would stand him a minute. I prefer Cassius Clay. “If a tiger move into the room with you,” says Cassius, “and you leave, that dont mean you hate the tiger. Just means you know you and him can’t make out. Too much talk about hate.” Cassius is too good for the Moslems.

That passage, published in “The Habit of Being,” echoed a remark in a 1959 letter, also to Maryat Lee, who had suggested that Baldwin—his “Letter from the South” had just run in Partisan Review—could pay O’Connor a visit while on a subsequent reporting trip. O’Connor demurred:

No I can’t see James Baldwin in Georgia. It would cause the greatest trouble and disturbance and disunion. In New York it would be nice to meet him; here it would not. I observe the traditions of the society I feed on—it’s only fair. Might as well expect a mule to fly as me to see James Baldwin in Georgia. I have read one of his stories and it was a good one.

O’Connor-lovers have been downplaying those remarks ever since. But they are not hot-mike moments or loose talk. They were written at the same desk where O’Connor wrote her fiction and are found in the same lode of correspondence that has brought about the rise in her stature. This has put her champions in a bind—upholding her letters as eloquently expressive of her character, but carving out exceptions for the nasty parts.

Last year, Fordham University hosted a symposium on O’Connor and race, supported with a grant from the author’s estate. The organizer, Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, edits a series of books on Catholic writers funded by the estate, has compiled a book of devotions drawn from O’Connor’s work, and has written a book of poems that “channel the voice” of the author. In a new volume in the series, “Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor” (Fordham), she takes up Flannery and That Issue. Proposing that O’Connor’s work is “race-haunted,” she applies techniques from whiteness studies and critical race theory, as well as Toni Morrison’s idea of “Africanist ‘othering.’ ” O’Donnell presents a previously unpublished passage on race and engages with scholars who have offered context for the racist remarks. Although she is palpably anguished about O’Connor’s race problem, she winds up reprising those earlier arguments in current literary-critical argot, treating O’Connor as “transgressive in her writing about race” but prone to lapses and excesses that stemmed from social forces beyond her control.

The context arguments go like this. O’Connor was a writer of her place and time, and her limitations were those of “the culture that had produced her.” Forced by illness to return to Georgia, she was made captive to a “Southern code of manners” that maintained whites’ superiority over blacks, but her fiction subjects the code to scrutiny. Although she used racial epithets carelessly in her correspondence, she dealt with race courageously in the fiction, depicting white characters pitilessly and creating upstanding black characters who “retain an inviolable privacy.” And she was admirably leery of cultural appropriation. “I don’t feel capable of entering the mind of a Negro,” she told an interviewer—a reluctance that Alice Walker lauded in a 1975 essay.

All the contextualizing produces a seesaw effect, as it variously cordons off the author from history, deems her a product of racist history, and proposes that she was as oppressed by that history as anybody else was. It backdates O’Connor as a writer of her time when she was a near-contemporary of writers typically seen as writers of our time: Gabriel García Márquez (born 1927), Maya Angelou (1928), Ursula K. Le Guin (1929), Tom Wolfe (1930), and Derek Walcott (1930), among others. It suggests that white racism in Georgia was all-encompassing and brooked no dissent, even though (as O’Donnell points out) Georgia was then changing more dramatically than at any point before or since. Patronizingly, it proposes that O’Connor, a genius who prized detachment, lacked the free will to think for herself.

Another writer of that cohort is Toni Morrison, who was born in Ohio in 1931 and became a Catholic at the age of twelve. Morrison published “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination” in 1992. “The fabrication of an Africanist persona” by a white writer, she proposed, “is reflexive: an extraordinary meditation on the self; a powerful exploration of the fears and desires that reside in the writerly consciousness.” Invoking Morrison, O’Donnell argues that O’Connor’s fiction is fundamentally a working-through of her own racism, and that the offending remarks in the letters “tell us . . . that O’Connor understood evil in the form of racism from the inside, as one who has practiced it.”

The clinching evidence is “Revelation,” drafted in late 1963. This extraordinary story involves Ruby Turpin—a white Southerner in middle age, the owner of a dairy farm—and her encounter in a doctor’s waiting room with a Wellesley-educated young woman, also white, who is so repulsed by Turpin’s condescension toward people there that she cries out, “Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog.” This arouses Turpin to quarrel with God as she surveys a hog pen on her property, and calls forth a magnificent final image of the hereafter in Turpin’s eyes—the people of the rural South heading heavenward. Some say this “vision” redeems the author on That Issue. Brad Gooch, in a 2009 biography, likened it to the dream that Martin Luther King, Jr., spelled out in August, 1963; O’Donnell, drawing on a remark in the letters, depicts it as a “vision O’Connor has been wresting from God every day for much of her life.” Seeing it that way is a stretch. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech envisioned blacks and whites holding hands at the end of time; Turpin’s vision, by contrast, is a segregationist’s vision, in which people process to Heaven by race and class, equal but separate, white landowners such as Turpin preceded (the last shall be first) by “bands of black niggers in white robes, and battalions of freaks and lunatics shouting and clapping and leaping like frogs.”

After revising “Revelation” in early 1964, O’Connor wrote several letters to Maryat Lee. Many scholars maintain that their letters (often signed with nicknames) are a comic performance, with Lee playing the over-the-top liberal and O’Connor the dug-in gradualist, but O’Connor’s most significant remarks on race in her letters to Lee are plainly sincere. On May 3, 1964—as Richard Russell, Democrat of Georgia, led a filibuster in the Senate to block the Civil Rights Act—O’Connor set out her position in a passage now published for the first time: “You know, I’m an integrationist by principle & a segregationist by taste anyway. I don’t like negroes. They all give me a pain and the more of them I see, the less and less I like them. Particularly the new kind.” Two weeks after that, she told Lee of her aversion to the “philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind.” Ravaged by lupus, she wrote Lee a note to say that she was checking in to the hospital, signing it “Mrs. Turpin.” She died at home ten weeks later.

Those remarks show a view clearly maintained and growing more intense as time went on. They were objectionable when O’Connor made them. And yet—the argument goes—they’re just remarks, made in chatty letters by an author in extremis. They’re expressive but not representative. Her “public work” (as the scholar Ralph C. Wood calls it) is more complex, and its significance for us lies in its artfully mixed messages, for on race none of us is without sin and in a position to cast a stone.

That argument, however, runs counter to history and to O’Connor’s place in it. It sets up a false equivalence between the “segregationist by taste” and those brutally oppressed by segregation. And it draws a neat line between O’Connor’s fiction and her other writing where race is involved, even though the long effort to move her from the margins to the center has proceeded as if that line weren’t there. Those remarks don’t belong to the past, or to the South, or to literary ephemera. They belong to the author’s body of work; they help show us who she was.

Posterity, in literature, is a strange god—consecrating Dickinson and Melville as American divines, repositioning T. S. Eliot as a man on the run from a Missouri boyhood and a bad marriage. Posterity has favored Flannery O’Connor: the readers of her work today far outnumber those in her lifetime. After her death, the racist passages were stumbling blocks to the next generation’s encounter with her, and it made a kind of sense to sidestep them. Now the reluctance to face them squarely is itself a stumbling block, one that keeps us from approaching her with the seriousness that a great writer deserves.

There’s a way forward, rooted in the work. For twenty years, the director Karin Coonrod has staged dramatic adaptations of O’Connor’s stories. Following a stipulation of the author’s estate, she uses every word: narration, description, dialogue, imagery, and racial epithets. Members of the multiracial cast circulate the full text fluidly from actor to actor, character to character, so that the author’s words, all of them, ring out in her own voice and in other voices, too. ♦

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hope Williams, MTS ’20

“My mission in life is to understand how religion can be a vehicle for peace in the world—well, one of my two missions. My other mission in life is to ‘help out anyone that needs it.’”

Hope is a second-year master of theological studies candidate studying religion, ethics, and politics.

A Draw to Interfaith Work

I come from a family that really values belief. I was born in Texas and I was raised most of my life in St. Louis, Missouri. It's a big thing in St. Louis: if you go to Catholic grade school, you choose which Catholic high school you're going to go to. I just felt none of the Catholic high schools were really clicking with me, and so I chose to go to my local public school instead.

Upon starting high school, I started getting more involved in my own spirituality, alongside having an interfaith household, and I realized that I was really excited about interfaith work. In the meantime, I was seeing a lot of different faiths at my high school that I hadn't really interacted with. I remember going to different religious services with my friends, who were of many faiths, and really seeing the value in various traditions.

I went to college at Loyola University of Chicago, a Jesuit school, which was really eye-opening—seeing faith as a vehicle for justice. I went through an entire spiritual, personal, and political transformation while at Loyola.

As a political science and religious studies major, I was really interested in interfaith work, taking a lot of classes on the intersection of religion, politics, and lived experiences. So I was really interested in the political implications of interfaith work and how can elected officials be better at talking about faith.

My senior year of college, I studied abroad in the United Arab Emirates. When I was there, I was studying Islamic philosophy, theology, and Arabic. This solidified my passion for interfaith work because not only did I see the similarities between Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, but really recognized how the differences bring out the beautiful nature of humanity.

Religion Meets Politics

One of my mentors at Loyola Chicago told me about Harvard Divinity School (HDS). I was living in Washington D.C., working at the Federal Judicial Center, and I had interned at some interfaith organizations in Chicago. That day I logged on and I saw that there was a week left to apply for the DivEx program.

When I was at DivEx, my first exposure to HDS, I quickly realized the people I was talking to everyday were the type of people that I want to be more like and try to surround myself with. I knew that HDS was the perfect fit for me—I felt like I had to be here. Alongside my HDS courses, I've taken about half my coursework at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), which has been a huge part of experience.

One of the most formative things at Harvard for me is being a part of the Kennedy School’s Oval Office program, which is a training program for graduate students who are interested in running for and holding public office. It’s a yearlong cohort program at the Women and Public Policy Program (WAPPP) for graduate students who want the training, networking, and resources to run for office in the future. That has been an incredible, and inspiring, community.

On a Track Towards Peace and Compassion

My whole first year I worked at HDS’s Religions and the Practice of Peace. I'm really passionate about using religion as a vehicle for peace. My mission in life is to understand how religion can be a vehicle for peace in the world—well, one of my two missions. My other mission in life is to ‘help out anyone that needs it.’

Speaking of peace, my first semester I took Jocelyn Cesari's class, “Jihad, Just War, and Holy War.” In the spring, I took “Politics of Terrorism” with Professor Erica Chenoweth. I loved having those classes back to back because I felt like they gave two very different, but important views of political violence. They created two different frameworks for thinking about political violence—what does peace look like? What could peace look like? What is a holistic peace framework?

I think that that's something HDS has really made me think more about: peace isn't just the absence of violence. Peace is the active work making things better holistically for all stakeholders and trying to figure out what that means practically in different situations.

I believe faith must happen alongside justice. We need to focus on getting rid of white supremacy, Islamophobia, homophobia, and xenophobia—those are all forms of violence. Those are violences we have to work to get rid of. That work, to me, starts with interfaith conversations.

The Beginnings of a Political Leader

I feel that structural policy changes are the best way for me to make systematic changes, and I definitely feel called to public service. The two things that I personally care about the most are: first, disability activism and the rights for individuals who have disabilities. I think that it's a conversation that, as a country, we're not having enough. My brother is disabled, so I have a lot of personal feelings about this issue. I think it's critically important and extremely ignored.

The second issue I care most about are women's reproductive health and making sure women have access to reproductive care, abortions, birth control, pap smears, breast cancer screenings, and all other care.

In the end, I’m not really sure what’s next, but I know whatever it is, I want to serve as a vision for kindness, justice, peace, and literally—hope.

Interview by Kaitlin Wheeler

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dome and Cupola that Were Not There

This blog post was originally published on November 30, 2012.

This perspective tour de force dazzles the eye with the complexities of its illusionistic architecture. The story behind the work is equally compelling.

When the magnificent Church of Saint Ignatius Loyola was constructed in Rome during the late 16th-century Counter Reformation, the newly founded Jesuit order was trying to solicit the faithful to their cause. They believed that the artist’s role was instrumental in proclaiming the faith and stimulating religious fervor. To this end, they hired Giovanni Battista Gaulli, known as Baciccio, to create an illusionary ceiling fresco with painted and stucco foreshortened figures that appeared to be rising to heaven or descending to hell. The illusionary effect was remarkable.

Starting in 1674, Andrea Pozzo, a member of the Jesuit Order, applied his own considerable talents to the remainder of the church’s ceiling and walls. Pozzo’s first task was to find a solution for the unfinished Gesu dome. The Church fathers had wanted to add a cupola (as a lantern) to the dome to magnify the space but were prevented from doing so by a legal suit. Pozzo’s brilliant solution was to paint a fictive dome and cupola on a flat canvas in quadratura—an illusionistic painting technique in which the perspective lines recede toward the center so the architectural elements seem to be an extension of the structure’s existing walls. Pozzo’s painting was then set in the drum of the real dome. Pozzo published his ideas on perspective in a famous treatise Perspectivae pictorum atque architectorum (The Rules and Examples of Perspective Proper for Painters and Architects), printed in two volumes in 1693 and 1700. The treatise included an illustrated section on the Gesu dome.

Andrea Pozzo, Trompe l’Oeil Dome, Church of Saint Ignatius Loyola, Rome, 1685. (Image credit: Jean-Christophe Benoist).

The author of this drawing��follows (with some important changes) plate 91 in Pozzo’s text, which illustrates how to create an illusionistic dome and cupola in quadratura that seems to extend the space above the actual church architecture. In his treatise, Pozzo wrote that that his book illustration would undoubtedly last longer than his painting, but the canvas is still in situ today! Pozzo’s influential book on perspective was published in 19 editions over a 50-year period in all Western languages, and Japanese. This drawing demonstrates the tremendous influence Pozzo had on the architects and painters that came after him.

Gail Davidson is the retired Curator & Head of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. .

from Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum https://ift.tt/3769oZq

via IFTTT

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 5 Catholic Artist-Recommended Parishes in NYC

Now that we've been sharing weekly interviews with Catholic artists in NYC for 6 months (!), we'd like to highlight some of the resources recommended in our 20+ interviews. This week: the top 5 parishes recommended by NYC Catholic artists!

1) St. Malachy's - The Actors' Chapel

This parish was by far the most-recommended, since it has a special outreach to the professional performing arts community. Located in Times Square (across from the Eugene O'Neill Theatre, home to the Broadway show Book of Mormon), St. Malachy's holds a special post-theatre Mass on Saturdays at 11 p.m., which caters to both tourists and Broadway performers. The choir sings at the Sunday 11 a.m., and at various concerts and cabarets throughout the year. Sunday at 6 p.m. is the Young Adult Mass, often followed by a social. This parish is the first stop for many actors moving to the city, and many performers continue to travel from all parts of the city to make this parish their church home. Its Artist Shrine, featuring a specially-commissioned icon of St. Genesius (patron saint of actors) as well as icons for the patron saints of dancers, musicians, and visual artists, is a quiet and beautiful place to light a candle and sit quietly before a show. (And our blog interviewee Christopher Alles restored the Stations of the Cross!) It is also home to the St. Genesius Society, a workshop for playwrights, directors, and actors that meets on Thursday nights.

Pastor: Fr. John Fraser

www.actorschapel.org

2) Church of St. Paul the Apostle (Paulists)

This church off of Columbus Circle is the motherhouse of the Paulist Fathers, a missionary society of men dedicated to the evangelization of North America. The Paulist community is home to Openings, a visual artist collective led by blog interviewee Fr. Frank Sabatté which holds exhibits in the church, and Busted Halo, a media ministry hosted by Fr. Dave Dwyer. St. Paul's has an active Young Adults group based at the Sunday 5:15 p.m. Mass, and the choir sings Sundays at 10 a.m. The parish also hosts a number of other groups and cultural activities year-round.

Pastor: Fr. Joseph Ciccone, CSP

www.stpaultheapostle.org

3) St. Vincent Ferrer (Dominicans)

A number of artists recommended the beauty of the liturgy and the sacred space of St. Vincent Ferrer, part of a combined parish with St. Catherine of Siena that is run by the Dominican Friars. The Office of Readings and Vespers are offered weekdays at 5:30 p.m. followed by 6 p.m. Mass, which is a convenient way to pray with the church community at the end of the workday. In addition, there are multiple musical options for weekend Mass, including several Sung Masses with cantor and the Solemn Mass with the Schola Cantorum, celebrated at 12 p.m. on Sundays at St. Vincent Ferrer.

Pastor: Fr. Walter Wagner, O.P.

www.svsc.info

4) St. Francis of Assisi (Franciscans)

St. Francis of Assisi offers as many daily Masses as St. Patrick's Cathedral, and almost as many weekend Masses. It also also open several hours each day for confessions, and is known as "New York's confessional." With its proximity to several subway lines as well as Penn Station, St. Francis is the place to catch daily Mass, confession, or adoration in between freelance gigs. The parish house can connect you to spiritual direction or to the St. Francis Counseling Center, which offers counseling at an income-based scale.

Pastor: Fr. Andrew Reitz, O.F.M.

www.stfrancisnyc.org

5) St. Ignatius Loyola (Jesuits)

St. Ignatius is one of the most spectacular sanctuaries in the city, with a choir to match (Solemn Mass - Sundays at 11 a.m.). Run by the Jesuits, it is a great place to find a spiritual director. The Ignatian Young Adults group is active and large, and the parish also hosts a Christian Life Community and Centering Prayer group. It is well-known for its Sacred Music in a Sacred Space concert series, which brings major international sacred music groups to the city as well as featuring extraordinary NYC-based talent.

Pastor: Fr. Dennis Yesalonia, S.J.

www.stignatiusloyola.org

And...a bonus parish (tied for recommendations with St. Francis and St. Ignatius)!

6) The Basilica of St. Patrick's Old Cathedral

This parish is the original cathedral for the Archdiocese of New York. It is located in Soho and surrounded by a beautiful old cemetery, whose grass is trimmed by sheep every summer (ported in from upstate for a summer vacation). The cathedral is across Houston Street from the Sheen Center, and is a hub for the downtown community of Catholic artists. The pastor, Msgr. Donald Sakano, is a supporter of the arts, and is always open to artists interested in helping with the Basilica Artists' Initiative.

Pastor: Msgr. Donald Sakano

www.oldcathedral.org

Let us know if you check out any of these parishes and make one your home!

#catholic#catholic church#catholic churches#churches#nyc#catholicnyc#catholic new york#new yorker#new york city#manhattan#st. malachy's#the actor's chapel#old st. patrick's#cathedral#st. ignatius loyola#jesuits#franciscans#dominicans#St. Vincent Ferrer#St. Francis of Assisi#st. paul the apostle#Church of St. Paul the Apostle

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Star

Arthur C. Clarke (1954)

It is three thousand light-years to the Vatican. Once, I believed that space could have no power over faith, just as I believed the heavens declared the glory of God’s handwork. Now I have seen that handiwork, and my faith is sorely troubled. I stare at the crucifix that hangs on the cabin wall above the Mark VI Computer, and for the first time in my life I wonder if it is no more than an empty symbol.

I have told no one yet, but the truth cannot be concealed. The facts are there for all to read, recorded on the countless miles of magnetic tape and the thousands of photographs we are carrying back to Earth. Other scientists can interpret them as easily as I can, and I am not one who would condone that tampering with the truth which often gave my order a bad name in the olden days.

The crew were already sufficiently depressed: I wonder how they will take this ultimate irony. Few of them have any religious faith, yet they will not relish using this final weapon in their campaign against me—that private, good-natured, but fundamentally serious war which lasted all the way from Earth. It amused them to have a Jesuit as chief astrophysicist: Dr. Chandler, for instance, could never get over it. (Why are medical men such notorious atheists?) Sometimes he would meet me on the observation deck, where the lights are always low so that the stars shine with undiminished glory. He would come up to me in the gloom and stand staring out of the great oval port, while the heavens crawled slowly around us as the ship turned over and over with the residual spin we had never bothered to correct.

“Well, Father,” he would say at last, “it goes on forever and forever, and perhaps Something made it. But how you can believe that Something has a special interest in us and our miserable little world—that just beats me.” Then the argument would start, while the stars and nebulae would swing around us in silent, endless arcs beyond the flawlessly clear plastic of the observation port.

It was, I think, the apparent incongruity of my position that cause most amusement among the crew. In vain I pointed to my three papers in the Astrophysical Journal, my five in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. I would remind them that my order has long been famous for its scientific works. We may be few now, but ever since the eighteenth century we have made contributions to astronomy and geophysics out of all proportion to our numbers. Will my report on the Phoenix Nebula end our thousand years of history? It will end, I fear, much more than that.

I do not know who gave the nebula its name, which seems to me a very bad one. If it contains a prophecy, it is one that cannot be verified for several billion years. Even the word “nebula” is misleading; this is a far smaller object than those stupendous clouds of mist—the stuff of unborn stars—that are scattered throughout the length of the Milky Way. On the cosmic scale, indeed, the Phoenix Nebula is a tiny thing—a tenuous shell of gas surrounding a single star.

Or what is left of a star. . .

The Rubens engraving of Loyola seems to mock me as it hangs there above the spectrophotometer tracings. What would you, Father, have made of this knowledge that has come into my keeping, so far from the little world that was all the Universe you knew? Would your faith have risen to the challenge, as mine has failed to do?

You gaze into the distance, Father, but I have traveled a distance beyond any that you could have imagined when you founded our order a thousand years ago. No other survey ship has been so far from Earth: we are at the very frontiers of the explored Universe. We set out to reach the Phoenix Nebula, we succeeded, and we are homeward bound with our burden of knowledge. I wish I could lift that burden from my shoulders, but I call to you in vain across the centuries and the light-years that lie between us.

On the book you are holding the words are plain to read. AD MAIOREM DEI

GLORIAM, the message runs, but it is a message I can no longer believe. Would you still believe it, if you could see what we have found?

We knew, of course, what the Phoenix Nebula was. Every year, in our Galaxy alone, more than a hundred stars explode, blazing for a few hours or days with hundreds of times their normal brilliance until they sink back into death and obscurity. Such are the ordinary novas—the commonplace disasters of the Universe. I have recorded the spectrograms and light curves of dozens since I started working at the Lunar Observatory. But three or four times in every thousand years occurs something beside which even a nova pales into total insignificance.

When a star becomes a supernova, it may for a little while outshine all the massed suns of the Galaxy. The Chinese astronomers watched this happen in A.D. 1054, not knowing what it was they saw. Five centuries later, in 1572, a supernova blazed in Cassiopeia so brilliantly that it was visible in the daylight sky. There have been three more in the thousand years that have passed since then.

Our mission was to visit the remnants of such a catastrophe, to reconstruct the events that led up to it, and, if possible, to learn its cause. We came slowly in through the concentric shells of gas that had been blasted out six thousand years before, yet were expanding still. They were immensely hot, radiating even now with a fierce violet light, but were far too tenuous to do us any damage. When the star had exploded, its outer layers had been driven upward with such speed that they had escaped completely from its gravitational field. Now they formed a hollow shell large enough to engulf a thousand solar systems, and at its center burned the tiny, fantastic object which the star had now become—a White Dwarf, smaller than earth, yet weighing a million times as much. The glowing gas shells were all around us, banishing the normal night of interstellar space. We were flying into the center of the cosmic bomb that had detonated millennia ago and whose incandescent fragments were still hurtling apart. The immense scale of the explosion, and the fact that the debris already covered a volume of space many millions of miles across, robbed the scene of any visible movement. It would take decades before the unaided eye could detect any motion in these tortured wisps and eddies of gas, yet the sense of turbulent expansion was overwhelming.

We had checked our primary drive hours before, and were drifting slowly toward the fierce little star ahead. Once it had been a sun like our own, but it had squandered in a few hours the energy that should have kept it shining for a million years. Now it was a

shrunken miser, hoarding its resources as if trying to make amends for its prodigal youth.

No one seriously expected to find planets. If there had been any before the explosion, they would have been boiled into puffs of vapor, and their substance lost in the greater wreckage of the star itself. But we made the automatic search, as we always do when approaching an unknown sun, and presently we found a single small world circling the star at an immense distance. It must have been the Pluto of this vanished Solar System, orbiting on the frontiers of the night. Too far from the central sun ever to have known life, its remoteness had saved it from the fate of all its lost companions. The passing fires had seared its rocks and burned away the mantle of frozen gas that must have covered it in the days before the disaster. We landed, and we found the Vault.

Its builders had made sure that we should. The monolithic marker that stood above the entrance was now a fused stump, but even the first long-range photographs told us that here was the work of intelligence. A little later we detected the continent-wide pattern of radioactivity that had been buried in the rock. Even if the pylon above the Vault had been destroyed, this would have remained, an immovable and all-but eternal beacon calling to the stars. Our ship fell toward this gigantic bull’s eye like an arrow into its target.

The pylon must have been a mile high when it was built, but now it looked like a candle that had melted down into a puddle of wax. It took us a week to drill through the fused rock, since we did not have the proper tools for a task like this. We were astronomers, not archaeologists, but we could improvise. Our original purpose was forgotten: this lonely monument, reared with such labor at the greatest possible distance from the doomed sun, could have only one meaning. A civilization that knew it was about to die had made its last bid for immortality.

It will take us generations to examine all the treasures that were placed in the Vault. They had plenty of time to prepare, for their sun must have given its first warnings many years before the final detonation. Everything that they wished to preserve, all the fruits of their genius, they brought here to this distant world in the days before the end, hoping that some other race would find it and that they would not be utterly forgotten. Would we have done as well, or would we have been too lost in our own misery to give thought to a future we could never see or share?

If only they had had a little more time! They could travel freely enough between the planets of their own sun, but they had not yet learned to cross the interstellar gulfs, and the nearest Solar System was a hundred light-years away. Yet even had they possessed the secret of the Transfinite Drive, no more than a few millions could have been saved. Perhaps it was better thus.

Even if they had not been so disturbingly human as their sculpture shows, we could not have helped admiring them and grieving for their fate. They left thousands of visual records and the machines for projecting them, together with elaborate pictorial instructions from which it will not be difficult to learn their written language. We have examined many of these records, and brought to life for the first time in six thousand years the warmth and beauty of a civilization that in many ways must have been superior to our own. Perhaps they only showed us the best, and one can hardly blame them. But their worlds were very lovely, and their cities were built with a grace that matches anything of man’s. We have watched them at work and play, and listened to their musical speech sounding across the centuries. One scene is still before my eyes—a group of children on a beach of strange blue sand, playing in the waves as children play on Earth. Curious whiplike trees line the shore, and some very large animal is wading in the shallows, yet attracting no attention at all.

And sinking into the sea, still warm and friendly and life-giving, is the sun that will soon turn traitor and obliterate all this innocent happiness.

Perhaps if we had not been so far from home and so vulnerable to loneliness, we should not have been so deeply moved. Many of us had seen the ruins of ancient civilizations on other worlds, but they had never affected us so profoundly. This tragedy was unique. It is one thing for a race to fail and die, as nations and cultures have done on Earth. But to be destroyed so completely in the full flower of its achievement, leaving no survivors—how could that be reconciled with the mercy of God?

My colleagues have asked me that, and I have given what answers I can. Perhaps you could have done better, Father Loyola, but I have found nothing in the Exercitia Spiritualia that helps me here. They were not an evil people: I do not know what gods they worshiped, if indeed they worshiped any. But I have looked back at them across the centuries, and have watched while the loveliness they used their last strength to preserve was brought forth again into the light of their shrunken sun. They could have taught us much: why were they destroyed?

I know the answers that my colleagues will give when they get back to Earth. They will say that the Universe has no purpose and no plan, that since a hundred suns explode every year in our Galaxy, at this very moment some race is dying in the depths of space. Whether that race has done good or evil during its lifetime will make no difference in the end: there is no divine justice, for there is no God.

Yet, of course, what we have seen proves nothing of the sort. Anyone who argues thus is being swayed by emotion, not logic. God has no need to justify His actions to man. He who built the Universe can destroy it when He chooses. It is arrogance—it is perilously near blasphemy—for us to say what He may or may not do.

This I could have accepted, hard though it is to look upon whole worlds and peoples thrown into the furnace. But there comes a point when even the deepest faith must falter, and now, as I look at the calculations lying before me, I have reached that point at last.

We could not tell, before we reached the nebula, how long ago the explosion took place. Now, from the astronomical evidence and the record in the rocks of that one surviving planet, I have been able to date it very exactly. I know in what year the light of this colossal conflagration reached the Earth. I know how brilliantly the supernova whose corpse now dwindles behind our speeding ship once shone in terrestrial skies. I know how it must have blazed low in the east before sunrise, like a beacon in that oriental dawn.

There can be no reasonable doubt: the ancient mystery is solved at last. Yet, oh God, there were so many stars you could have used. What was the need to give these people to the fire, that the symbol of their passing might shine above Bethlehem?

0 notes

Text

Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts

Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts Chicago, Illinois Jesuit college prep school, USA Architectural News

Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts news

July 21, 2021

Location: Chicago Loop at 200 North State Street, Chicago, IL 60601, United States

Design: Krueck Sexton Partners

Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts designed by Krueck Sexton Partners, Breaks Ground

Flexible indoor and outdoor performance spaces will expand the student experience at the Jesuit college preparatory school.

Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts Building

CHICAGO, July 2021—A striking new performing arts center has broken ground on the campus of Loyola Academy, a private Jesuit college preparatory school in Wilmette, Ill.

Designed by Chicago-based Krueck Sexton Partners (KSP), the $25.76 million Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts will transform the northeast corner of the school’s campus with flexible indoor and outdoor performance spaces that support a vibrant arts program for all students.

The 29,000-square-foot building is strategically positioned to form a new campus quadrangle and outdoor plaza that will function as an open-air performance stage and, a social and gathering space for the entire Loyola community, which celebrates the arts as a central part of their individual and collective well-being. A 125-linear-foot undulating curved glass wall will blur the distinction between indoor and outdoor spaces.

“In our conversations with Loyola leadership, it became clear that we are working with a client who is seeking transformational change, the DNA of the Jesuit experience,” said Tom Jacobs, AIA, LEED AP, co-managing partner at Krueck Sexton Partners. “It was critical for Loyola to strengthen the fine arts on campus, and to elevate it to equal standing with academics and sports The theater acts as a connector that extends cross-campus circulation, and the new quad will function as a campus ‘town square.’

Inside, a spacious lobby and gallery space will lead to the Leemputte Family Theater, a 565-seat proscenium theater with a balcony, orchestra pit, fly tower, and state-of-the-art lighting and production technologies. Adjacent to the theater is an offstage rehearsal and staging area; a fully equipped scene shop; a green room; makeup and dressing rooms; and a flexible student lounge connecting the center to the fine arts wing on the east side of Loyola’s Wilmette campus.

Students in Loyola’s American Institute of Architecture (AIA) student chapter played an active role in the planning and design process to ensure the performing arts center will benefit the entire campus community. Parents, donors, and other community stakeholders have also been engaged throughout project development.

The Jesuit commitment of “Caring for Our Common Home”—the 2015 encyclical by Pope Francis that calls on all people of the world to take swift and unified global action considering environmental degradation and global warming—guided the project’s sustainability goals, which also align with KSP’s commitment as a signatory firm in the AIA 2030 Commitment to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

“True leadership in education considers the well-being of all far into the future. As a high-performing building that uses 58 percent less energy when compared against the local average of peer institutions, the theater is a testament to the ‘be more’ ethos that pervades Loyola Academy. It is a building that future Ramblers will look to and recognize that they are part of a group of people who literally practice what they preach,” said Sara Lundgren, AIA, LEED AP, project director and partner at Krueck Sexton Partners.

The all-electric building will further reduce carbon emissions as the Chicagoland grid continues its transition to all-renewable fuel sources by 2035. High-efficiency building systems will be installed in anticipation of a future rooftop-mounted photovoltaic array that accommodates the building’s entire energy load.

The building is predominantly precast concrete, a strategic material that performs as enclosure and structure while also providing mass for acoustic performance, a requirement given the project’s direct adjacency to the Edens Expressway. The use of fly ash in both the precast and cast-in-place concrete will reduce the carbon footprint of the concrete by 30 percent. An additional 10 percent reduction in embodied carbon will be achieved by using CO2 mineralization process in the cast-in-place concrete. The total carbon impact of these materials is equivalent to converting the 20-acre Loyola Academy Wilmette campus into an old-growth oak forest for 30 years.

“Since the first Jesuit school opened nearly five centuries ago, we have understood that the arts play an important role in the enrichment of the human spirit and the development of creative thinkers with the potential to transform society in positive ways,” said president of Loyola Academy, Rev. Patrick E. McGrath, SJ. “Our new performing arts center represents a long-anticipated expansion of resources and facilities that will benefit all Loyola students and expand access to a broader network of our community partners, neighbors, and friends.”

Construction of the Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts, home of the Leemputte Family Theater is expected to be completed in 2022.

Valenti Builders is the general contractor. Other key project consultants include Coen Partners (landscape architect), Thornton Tomasetti (structural engineer), ESD (mechanical/electrical/plumbing engineer), A10 (sustainability consultant), Schuler Shook (theater designer and lighting design), Threshold (acoustics), Terra Engineering (civil engineer), Edward Peck (glazing), and Raths, Raths & Johnson (waterproofing).

About Krueck Sexton Partners

Krueck Sexton Partners (KSP) is a Chicago-based architectural design practice with a 40-year legacy of creating environments that elevate the human experience. Grounded in the pragmatism and clarity of Chicago’s architectural heritage, KSP brings together a natural curiosity with insights from the firm’s diverse body of work. The KSP team is committed to realizing each project’s hidden potential and creating opportunities to increase its impact and value.

Loyola Academy Center for the Performing Arts building images / information received 200721 from Krueck Sexton Partners

Krueck Sexton Partners

Location: Chicago, IL, United States

Chicago Architecture

Contemporary Illinois Architecture – architectural selection below:

Chicago Architecture Designs – chronological list