#maidros

Text

Maedhros spelled as Maidros in The Histories of Middle Earth gives me a massive ick.

Also, I love his name Russandol. He's such a cutie patootie his name has the word doll in it.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quote of the day:

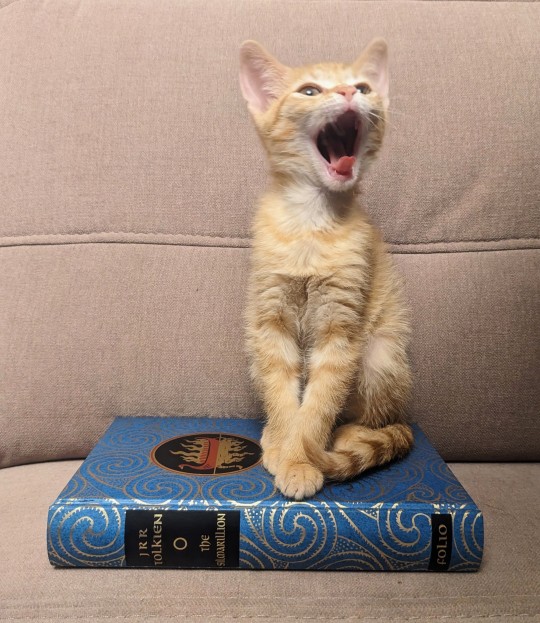

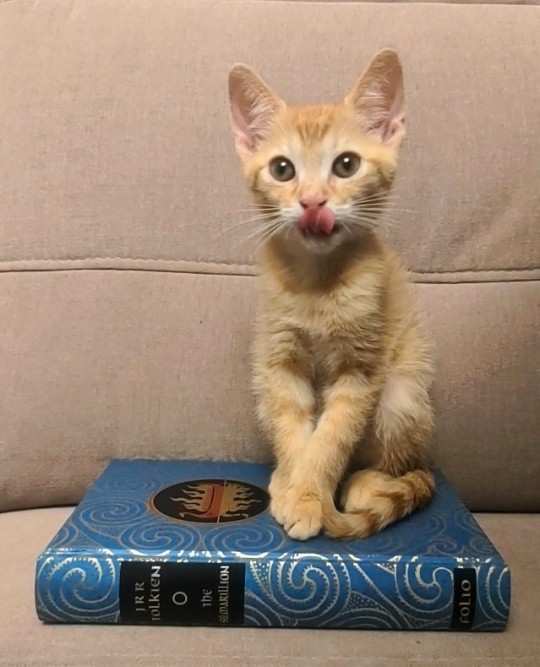

Husband: I've got to ask you why you named the cat after the Elf of war crimes and expected him not to be a nuisance.

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two Bones outfit edits I made for AoS streams! :D

#AoS SMP#AoS#Art of Survival SMP#Art of Survival#Bones#My Art#A Blaze Breathes#Maid outfit one nicknamed Maidroe

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

maedhros and his greek tragedy swag…

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! This blog is a very cool concept.

If you feel up to it, I'd like to know where the idea of Maedhros as a diplomat and scholar comes from.

In fic he's often portrayed as such in Valinor, serving at Finwë's court, sometimes being close with Fingolfin, bring into linguistics, etc.

Thank you!

Maedhros the Diplomat (with an Addendum on Maedhros the Scholar)

[~3.4k Words]

Ah, Maedhros. A treasure trove of fanon for our first excavation. As this is also our first investigation of characterisation, let’s establish a structure for talking about characters.

There are two ways that we learn what a character is like from The Silmarillion:

The narrator tells us, either:

a. with short, pithy statements (someone is “wise” or “steadfast” or “greatest”)

b. with longer descriptions

We deduce character from their actions and their relationships to others.

Using this structure, let’s look briefly as what we know about Maedhros.

1a.

Maedhros isn’t “mightiest in skill of word and hand” like his father or “the strongest, the most steadfast, and the most valiant” like Fingolfin. He isn’t even noted as being particularly good at anything like his brothers Maglor “the mighty singer,” Curufin “who inherited most if his father’s skill of hand,” or Celegorm, Amrod, and Amras who were all skilled hunters. He’s not even noteworthy for any negative traits like Caranthir, “the harshest of the brothers and the most quick to anger.”

Despite being one of the story’s protagonists, and certainly the most narratively prominent of the sons of Fëanor, all Maedhros gets in this category is “tall”[1].

1b.

In this category, Maedhros gets more fully fleshed-out:

[At Lake Mithrim] Maedhros in time was healed; for the fire of life was hot within him, and his strength was of the ancient world, such as those possessed who were nurtured in Valinor. His body recovered from his torment and became hale, but the shadow of his pain was in his heart; and he lived to wield his sword with left hand more deadly than his right had been.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Return of the Noldor”

Maedhros did deeds of surpassing valour, and the Orcs fled before his face; for since his torment upon Thangorodrim his spirit burned like a white fire within, and he was as one that returns from the dead.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Ruin of Beleriand”

Perhaps one of the most striking descriptions of Maedhros comes from an abandoned alliterative verse poem, The Flight of the Noldoli (=Noldor), published in The Lays of Beleriand and dating to 1925 — about a year before Tolkien first put the “Silmarillion” into a prose format in the annalistic-historical mode of the published text.

... and Maidros tall

(the eldest, whose ardour yet more eager burnt

than his father’s flame, than Fëanor’s wrath;

him fate awaited with fell purpose.)

Flight of the Noldoli, lines 123-126

Fire, valour, pain, deadliness, wrath, doom. Taken alone, these passages don’t exactly suggest "diplomat and scholar," yet those qualities are a cornerstone how we often see Maedhros discussed and portrayed by fans. So why?

2.

Maedhros the Diplomat, at least, seems to be based on what he does in canon.

Pausing for a moment, what does it actually mean to be "diplomatic"?

Here’s from Merriam-Webster under diplomatic:

[…]

of, relating to, or concerned with the art and practice of conducting negotiations between nations: of, relating to, or concerned with diplomacy or diplomats.

employing tact and conciliation especially in situations of stress

And for diplomacy:

the art and practice of conducting negotiations between nations

skill in handling affairs without arousing hostility: TACT

It’s worth noting that the first use of the word diplomacy dates to the 18th century (1766) and the concept itself is somewhat anachronistic to the pre-modern world of the “Silmarillion.” However, it’s not difficult to apply the spirit of an “art and practice of negotiations between nations” to First Age Beleriand. We’ll also consider the secondary definition of “tact.”

The Case for Maedhros the Diplomat

Let's look at some times that Maedhros practiced diplomacy and was diplomatic:

1. Waiving his claim to the kingship of the Noldor in favour of Fingolfin:

For Maedhros begged forgiveness for the desertion in Araman; and he waived his claim to kingship over all the Noldor, saying to Fingolfin: ‘If there lay no grievance between us, lord, still the kingship would rightly come to you, the eldest here of the house of Finwë, and not the least wise.’

The Silmarillion, “Of the Return of the Noldor”

Is this an instance of diplomacy? Yes: resolving conflict by removing one’s own claim to a title.

Is it diplomatic? The dialogue seems pretty tactful — demonstrating deference, employing flattery and logic — and is definitely an improvement on Fëanor’s approach to the contested kingship!

2. Brother-wrangling

There are two significant instances of this in the Silmarillion:

resolving conflict

After an argument breaks out between Angrod and Caranthir over Angrod’s authority to act as messenger to Thingol, “Maedhros indeed rebuked Caranthir … But Maedhros restrained his brothers, and they departed from the council…" (“Of the Return of the Noldor”)

Is this an instance of diplomacy? Yes: removing threats to peaceable relations between rulers.

Is it diplomatic? Since we don’t know exactly how Maedhros rebuked Caranthir and restrained his brothers, it’s hard to say how tactfully it was done. Maybe.

removing to the Eastern march

There Maedhros and his brothers kept watch, gathering all such people as would come to them, and they had few dealings with their kinsfolk westward, save at need. It is said indeed that Maedhros himself devised this plan, to lessen the chances of strife, and because he was very willing that the chief peril of assault should fall upon himself.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Return of the Noldor”

Is this an instance of diplomacy? Yes: again removing threats to peaceable relations between rulers. Also involves gathering followers. Notably, the strategy seems to have worked for as long as it lasted (that is, until Celegorm and Curufin found themselves in Nargothrond).

Is it diplomatic? Again, unclear how Maedhros executed this plan, but the narrator’s tone here is quite approving so it’s reasonable to assume that it was done tactfully.

3. Remaining on good terms with the other Princes of the Noldor

A few examples of this:

Continuing from the preceding passage, “he remained for his part in friendship with the houses of Fingolfin and Finarfin, and would come among them at times for common counsel.” (“Of the Noldor in Beleriand”)

Is this an instance of diplomacy? Yes.

Is it diplomatic? Yes: extra diplomacy points for taking it upon himself to go to them.

He (with Maglor) attended Mereth Aderthad, the Feast of Reuniting. (“Of the Noldor in Beleriand”)

Is this an instance of diplomacy? Yes, though showing up to the High King’s peace party seems like pretty bare minimum lordly behaviour, not exemplary diplomacy.

Is it diplomatic? We don’t know except through the absence of any evidence to the contrary. Since the Mereth Aderthad was overall a diplomatic success, it’s reasonable to assume Maedhros contributed to that success and stayed on his best behaviour.

He (with Maglor) goes hunting with Finrod. (“Of the Coming of Men into the West”)

Is this an instance of diplomacy? Sure: a leisurely hunting trip with the cousin whose kin you once killed (oops) is a good move.

Is it diplomatic? Again, lacking evidence to the contrary, reasonable to assume Maedhros behaved himself and the trip went off without conflict.

Remaining on good terms in particular with “Fingon, ever the friend of Maedhros” (“Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”). The anecdote about the history of the Dragon-helm (below), which has it pass from Maedhros to Fingon, additionally attests that these two “often exchanged tokens of friendship.”

Is this an instance of diplomacy? Yes: in particular, the exchange of tokens of friendship between rulers.

Is it diplomatic? Unless we imagine Fingon was himself tactless (which is contradicted by what we’re told about him elsewhere) and their friendship was built around being mutually despicable (see: Celegorm and Curufin), fair to assume this was all done courteously.

4. Making alliances

with the Sindar

We know that many Sindar outside Doriath joined themselves to and followed the princes of the Noldor, presumably including the sons of Fëanor. (The Grey Annals §48 in The History of Middle-earth Vol. 11: The Wars of the Jewels, and elsewhere).

with the Dwarves

In the preparations for the Nirnaeth Arnoediad:

... Maedhros had the help of the Naugrim, both in armed force and in great store of weapons; and the smithies of Nogrod and Belegost were busy in those days.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”

Also, from the Narn i hîn Húrin in Unfinished Tales:

[The Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin] was given by Azaghâl to Maedhros, as guerdon for the saving of his life and treasure, when Azaghâl was waylaid by Orcs upon the Dwarf-road in East Beleriand.

Azaghâl then sacrifices himself and his people at the Nirnaeth, making the Fëanorian retreat possible.

with the Easterlings

But Maedhros, knowing the weakness of the Noldor and the Edain, whereas the pits of Angband seemed to hold store inexhaustible and ever-renewed, made alliance with these new-come Men, and gave his friendship to the greatest of their chieftains, Bor and Ulfang. And Morgoth was well content; for this was as he had designed. The sons of Bor were Borlad, Borlach, and Borthand; and they followed Maedhros and Maglor, and cheated the hope of Morgoth, and were faithful. The sons of Ulfang the Black were Ulfast, and Ulwarth, and Uldor the accursed; and they followed Caranthir and swore allegiance to him, and proved faithless.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”

the Union of Maedhros

Perhaps Maedhros' most-cited and most famous act of "diplomacy":

Yet Morgoth would destroy them all, one by one, if they could not again unite, and make new league and common council; and he began those counsels for the raising of the fortunes of the Eldar that are called the Union of Maedhros.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”

And [Maedhros] gathered together again all his brothers and all the people who would follow them; and the Men of Bor and Ulfang were marshalled and trained for war, and they summoned yet more of their kinsfolk out of the East. Moreover in the west Fingon, ever the friend of Maedhros, took counsel with Himring, and in Hithlum the Noldor and the Men of the house of Hador prepared for war.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”

Are these instances of diplomacy? Yes: protecting neighbours, gathering followers, establishing partnerships, forming alliances with other groups of peoples, and organising a major offensive on a common enemy.

Is it diplomatic? Again, absence to the contrary and general success suggests Maedhros conducted himself tactfully in all of these dealings. One thing: I have seen a tendency in fandom to credit superior leadership and diplomacy on the part of Maedhros and Maglor for the fact that their Easterling allies remain faithful while Caranthir’s do not. Maybe; but bear in mind that’s a deduction, not something the text explicitly states.

I am sure there are other tidbits here and there to support the diplomatic ability of Maedhros, but I think we have enough here to conclude the Maedhros the Diplomat is a fanon characterisation with support it in canon.

The Case against Maedhros the Diplomat

So Maedhros was a diplomat; but was Maedhros an exemplary diplomat, as the prominence of his characterisation as such would suggest, or just an average one? Let us look at some of Maedhros’ diplomatic failings.

1. hubris, attempted deception

Look: we can’t neglect that Maedhros is behind one of the most disastrous failures of diplomacy in the First Age — his attempt to parley with Morgoth that ends up getting him captured.

Though not in the published Silmarillion, in the 1937 Quenta Silmarillion, Fëanor with his dying breath tells his sons “never to treat or parley with their foe.” (§88). (Christopher Tolkien drew from a later text, the Grey Annals (1950s), for the account of the death of Fëanor in the published Silmarillion where this command does not exist.) I cannot help but laugh at the fact that following this exhortation Maedhros immediately turns around and attempts to parley with Morgoth and outwit him.

Perhaps diplomatic relations with Morgoth are impossible, but then why accept the offer to parley at all? And what’s up with trying to beat Morgoth at his own game (deceit)? Honestly, Maedhros. Not your best moment.

We can say that he learned from this, but it does put into question the idea that Maedhros’ diplomatic training and excellence go back to his Valinorean days.

2. disdain of and aloofness towards another ruler

We saw how Maedhros restrained his brothers in the council where Angrod brought news from Thingol, but what about how Maedhros himself behaved at that council?

Cold seemed its welcome to the Noldor, and the sons of Fëanor were angered at the words; but Maedhros laughed, saying: ‘A king is he that can hold his own, or else his title is vain. Thingol does but grant us lands where his power does not run. Indeed Doriath alone would be his realm this day, but for the coming of the Noldor. Therefore in Doriath let him reign, and be glad that he has the sons of Finwë for his neighbours, not the Orcs of Morgoth that we found. Elsewhere it shall go as seems good to us.’

The Silmarillion, “Of the Return of the Noldor”

Fandom loves the line and I can’t disagree that it’s an epic mic drop. But was this really the most diplomatic thing to say? In the Grey Annals, it is said that “the sons of Fëanor were ever unwilling to accept the overlordship of Thingol, and would ask for no leave where they might dwell or might pass.” (§48). (Interestingly, there does seem to have been a point, before word of the kinslaying at Alqualondë was out, that Thingol for his part was at least neutral on them, saying, “Of his sons I hear little to my pleasure; yet they are likely to prove the deadliest foes of our foe” (“Of the Noldor in Beleriand”)). Arriving at a new place and refusing to treat with the person who claims kingship of those lands — and apparently for no other reason besides disdain of that person’s ability as a ruler — doesn’t seem particularly diplomatic.

3. not supporting a superior's initiative

We saw evidence of Maedhros cooperating with the other princes of the Noldor, but that doesn't mean he threw his support behind them at every occasion to do so. When Fingolfin — supposedly, thanks for Maedhros, High King and his superior — tries to rally the Noldor to assault Angband, almost everyone was “little disposed to hearken to Fingolfin, and the sons of Fëanor at that time least of all.” (“Of the Ruin of Beleriand”).

This statement is frustratingly vague so I won’t speculate much besides to suggest that there could be something suspect — and undiplomatic — behind failing to support the initiative of the High King to whom you so graciously ceded your claim.

4. Oath-related diplomatic failures (kinslayings)

The extent to which the oath is to blame for events is a sticky issue and not the subject of this analysis, but since fulfilling the oath is essential to Maedhros’ character, it’s impossible to avoid it entirely.

The narrator of the Silmarillion is actually quite generous towards Maedhros when discussing the role of the oath in his failings, so it’s no surprise that many fans are likewise generous.

For example:

I quoted above the passage about Maedhros taking “the chief peril of assault” upon himself and remaining “for his part in friendship with the houses of Fingolfin and Finarfin,” and it is perhaps the strongest evidence for Maedhros’ diplomatic excellence. It also ends with the ominous words: “Yet he also was bound by the oath, though it slept now for a time.” (“Of the Return of the Noldor”)

And when the concept of the Union of Maedhros is introduced, we are told: “Yet the oath of Fëanor and the evil deeds that it had wrought did injury to the design of Maedhros, and he had less aid than should have been.” (“Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”).

Both of these passages remind us that the oath — a vow to vengeance — is in the long-term at cross-purposes with cooperation and diplomacy.

This becomes especially evident when a Silmaril ends up in the hands of those who should be allies: other elves.

For Maedhros and his brothers, being constrained by their oath, had before sent to Thingol and reminded him with haughty words of their claim, summoning him to yield the Silmaril, or become their enemy.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”

The narrator pins this failure of diplomacy on the oath. But, as Maglor will point out in his final moments with Maedhros, the oath does not state how and when they must fulfill it. Is it a mark of a good diplomat to use “haughty” words in making a request? And what about what follows Thingol’s refusal?

Therefore [Thingol] sent back the messengers with scornful words. Maedhros made no answer, for he had now begun to devise the league and union of the Elves; but Celegorm and Curufin vowed openly to slay Thingol and destroy his people, if they came victorious from war, and the jewel were not surrendered of free will.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad”

What do you mean, “made no answer”? The narrator explains this away by saying essentially that Maedhros was too busy to bother, but is it the most diplomatic to just… stop communicating with the king who had the Silmaril, and whose support would really be quite nice to have in the upcoming war? And what about Celegorm and Curufin’s decidedly undiplomatic threat? Long gone are the days of effective brother-wrangling, apparently. (So far gone, in fact, that by the time Celegorm carries through on his threat and the sons of Feanor attack Doriath, Maedhros seems to have deferred to Celegorm’s leadership.)

The oath is again blamed for Maedhros’ change of course regarding the Silmaril at the Havens of Sirion. Having initially “withheld his hand”:

… the knowledge of their oath unfulfilled returned to torment [Maedhros] and his brothers, and gathering from their wandering hunting-paths they sent messages to the Havens of friendship and yet of stern demand.

The Silmarillion, “Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath”

As with the “haughty words” to Thingol, was “stern demand” the most diplomatic approach? Would better diplomacy have made a difference? Well, maybe. I don’t think the discussion between Maedhros and Maglor was inserted into the narrative without thematic purpose — and one of those purposes is, I think, to reveal the slippery space of conflict between obligation and choice; between that which must be done and how it’s done; between the morality of keeping one’s word and the morality of doing the right thing.

Does the oath itself turn an otherwise mild and affable Maedhros into someone haughty and stern? Or are those flaws he already had and which are brought to the fore by the constraint of the oath? Well, examine the evidence for yourself — and allow the imagination to roam.

Final assessment: Maedhros is a good diplomat, certainly compared to his closest kinsmen. But just like Maedhros isn’t the tallest (no, really, he’s not — but that’s another excavation), he’s perhaps also not the best diplomat on the political stage of First Age Beleriand.

[1] If we go beyond the published Silmarillion to the “Shibboleth of Fëanor” (in History of Middle-earth Vol. 12: The Peoples of Middle-earth), we learn that he was a red-head and apparently “well-shaped.” For an author who is notoriously sparse with physical description, Tolkien did seem to have a lot of ideas about what Maedhros looked liked!

Addendum: Maedhros the Scholar

“Diplomat and Scholar” do seem to go hand-in-hand in the fandom’s most popular versions of Maedhros, but I focused on the former for this Ask because there really isn’t much in canon to directly support Maedhros’ skill as a scholar.

The Noldor, as a culture, are loremasters. Fëanor, Maedhros’ father, was one of the most notable of these loremasters, even credited with founding the school of Lambengolmor, Loremasters of Tongues ( in the essay Quendi and Eldar in The History of Middle-earth Vol. 11: The War of the Jewels).

But, when Tolkien gives examples of elven loremasters, who, he says, were also “the greatest kings, princes and warriors,” he names Fëanor, Finrod, the lords of Gondolin, and Orodreth. No mention of Maedhros. And, when discussing which sons of Fëanor took an interest in language, he mentions not the eldest, but Maglor and Curufin. (Both in The Shibboleth of Fëanor.)

So there’s nothing in canon to suggest that Maedhros wasn’t a scholarly type, but it’s not something he’s noted for. His most remarkable trait remains “tall”.

#maedhros#silm meta#the silmarillion#history of middle-earth#1937 quenta silmarillion#melestasflight

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Third Kinslaying

A Silmarillion question that never ceases to trouble me, and for which I am not sure I will ever come up with an answer that satisfies me: What were Maedhros and Maglor’s justifications for taking Elrond and Elros after the sack of Sirion?

I know many people are satisfied with emotion-based reasoning, but that alone just doesn’t work for me personally. I read Maedhros and Maglor at this point in the narrative as very tormented, yes, but still capable of weighing logic and emotion at the same time. I also don't think the tone of the text supports outright villainy and ruthlessness (though that's a valid hc, especially from a non-Feanorian pov).

I’m not going to dive into my interpretation (I’m writing a fic for that), but I wanted to share the evidence and highlight what I think is the (Doylist) explanation for why the question is such a tough one to crack: None of Tolkien’s drafts covering this event* took the character of Gil-galad (or Círdan, though he was a character and not ret con'd like G-g) into consideration. He was simply not a factor in any of the versions published in HoMe.

If you’re like me and love the ‘textual archaeology’ of figuring out how the published text was derived (and since I bothered to type them all up) here are all the drafts of the third kinslaying alongside the published Silm. (There's good stuff in here for enjoyers of Elwing, Maedhros, and Maglor, too -- and haters of Amrod and Amras lol.)

*unless there are unpublished notes or notes that have evaded me somewhere

Book of Lost Tales (late 1910s/early 1920s)

In BoLT, the Havens are sacked by Melko.

Sketch of the Mythology (1926-30)

The sons of Fëanor learning of the dwelling of Elwing and the Nauglafring [=Nauglamir] had come down on the people of Gondolin. In a battle all the sons of Fëanor save Maidros [footnote: > Maidros and Maglor] were slain, but the last folk of Gondolin destroyed or forced to go away and join the people of Maidros [footnote: Written in the margin: Maglor sat and sang by the sea in repentance]. Elwing cast the Nauglafring into the sea and leapt after it [footnote: My father first wrote Elwing cast herself into the sea with the Nauglafring, but changed it to Elwing cast the Nauglafring into the sea and leapt after it in the act of writing], but was changed into a white sea-bird by Ylmir [=Ulmo], and flew to seek Eärendel, seeking about the shores of the world.

Their son (Elrond) who is half-mortal and half-elfin [footnote: This sentence was changed to read: Their son (Elrond) who is part mortal and part elfin and part of the race of the Valar], a child, was saved however by Maidros.”

The Quenta Noldorinwa (1930)

I

The dwelling of Elwing at Sirion’s mouth, where still she possessed the Nauglafring and the glorious SIlmaril, became known to the sons of Fëanor; and they gathered together from their wandering hunting-paths. But the folk of Sirion would not yield that jewel which Beren had won and Lúthien had worn, and for which fair Dior had been slain. And so befell the last and cruellest slaying of Elf by Elf, the third woe achieved by the accursed oath; for the sons of Fëanor came down upon the exiles of Gondolin and the remnant of Doriath, and though some of their folk stood aside and some few rebelled and were slain upon the other part aiding Elwing against their own lords, yet they won the day. Damrod [=Amrod] was slain and Díriel [=Amras], and Maidros and Maglor alone now remained of the Seven; but the last of the folk of Gondolin were destroyed or forced to depart and join them to the people of Maidros. And yet the sons of Fëanor gained not the Silmaril; for Elwing cast the Nauglafring into the sea, whence it shall not return until the End; and she leapt herself into the waves, and took the form of a white sea-bird, and flew away lamenting and seeking for Eärendel about all the shores of the world.

But Maidros took pity upon her child Elrond, and took him with him, and harboured and nurtured him, for his heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath.”

II

Upon the havens of Sirion new woe had fallen. The dwelling of Elwing there, where still she possessed the Nauglafring [footnote: > Nauglamir at both occurrences] and the glorious SIlmaril, became known to the remaining sons of Fëanor, Maidros and Maglor and Damrod and Díriel; and the gathered from their wandering hunting-paths, and messages of friendship and yet stern demand they sent unto Sirion. But Elwing and the folk of Sirion would not yield that jewel which Beren had won and Lúthien had worn, and for which Dior the Fair was slain; and least of all while Eärendel their lord was in the sea, for them seemed that in that jewel lay the gift of bliss and healing that had come upon their houses and their ships.

And so came in the end to pass the last and cruellest of the slayings of Elf by Elf; and that was the third of the great wrongs achieved by the accursed oath. For the sons of Fëanor came down upon the exiles of Gondolin and the remnant of Doriath and destroyed them. Though some of their folk stood aside, and some few rebelled and were slain upon the other part aiding Elwing against their own lords (for such was the sorrow and confusion in the hearts of Elfinesse in those days), yet Maidros and Maglor won the day. Alone they now remained of the sons of Fëanor, for in that battle Damrod and Díriel were slain; but the folk of Sirion perished of fled away, or departed of need to join the people of Maidros, who claimed now the lordship of all the Elves of the Outer Lands. And yet Maidros gained not the Silmaril, for Elwing seeing that all was lost and her child Elrond [footnote: > her children Elros and Elrond] taken captive, eluded the host of Maidros, and with the Nauglafring upon her breast she cast herself into the sea, and perished as folk thought.

[...] But great was the sorrow of Eärendel and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons, for whom they feared death, and yet it was not so. For Maidros took pity upon Elrond, and he cherished him, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maidros’ heart was sick and weary [footnote: This passage was rewritten thus: But great was the sorrow of Eärendel and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons; and they feared that they would be slain. But it was not so. For Maglor took pity upon Elros and Elrond, and he cherished them, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maglor’s heart was sick and weary &c.] with the burden of the dreadful oath.

Earliest Annals of Beleriand (AB 1) (1930-37, prior to AB 2)

AB I

225 Torment of Maidros and his brothers because of their oath. Damrod and Díriel resolve to win the Silmaril if Eärendel will not yield it up.

[...]

The folk of Sirion refused to give up the Silmaril in Eärendel’s absence, and they thought their joy and prosperity came of it.

229 Here Damrod and Díriel ravaged Sirion, and were slain. Maidros and Maglor gave reluctant aid. Sirion’s folk were slain or taken into the company of Maidros. Elrond was taken to nurture by Maglor. Elwing cast herself into the sea, but by Ulmo’s aid in the shape of a bird flew to Eärendel and found him returning.

AB II does not go this far.

The Later Annals of Beleriand (AB 2) (1930-37, after AB 1)

325 [525] Torment fell upon Maidros and his brethren, because of their unfulfilled oath. Damrod and Díriel resolved to win the Silmaril, if Eärendel would not give it up willingly. [...] The folk of Sirion refused to surrender the Silmaril, both because Eärendel was not there, and because they thought their bliss and prosperity came from the possession of the gem.

329 [529] Here Damrod and Díriel ravaged Sirion, and were slain. Maidros and Maglor were there, but they were sick at heart. This was the third kinslaying. The folk of Sirion were taken into the people of Maidros, such as yet remained; and Elrond was taken to nurture by Maglor. But Elwing cast herself with the Silmaril into the sea, and Ulmo bore her up, and in the shape of a bird she flew seeking Eärendel, and found him returning.

Quenta Silmarillion (1937) and The Later Quenta Silmarillion (1950s). These drafts were left incomplete and do not cover the events of the third kinslaying.

The Tale of Years (1950s)

Texts A, B

529 Third and Last Kin-slaying

Text C

532 [> 534 > 538] The Third and Last Kinslaying. The Havens of Sirion destroyed and Elros and Elrond sons of Eärendel taken captive, but are fostered with care by Maidros.

Text D2 (ends at 527)

512 Sons of Fëanor learn of the uprising of the New Havens, and that the Silmaril is there, but Maidros forswears his oath.

[...]

527 Torment fell upon Maidros and his brethren (Maglor, Damrod and Díriel) because of their unfulfilled oath.

Letter 211 (1958)

Elrond, Elros. *rondō was a prim[itive] Elvish word for 'cavern'. Cf. Nargothrond (fortified cavern by the R. Narog), Aglarond, etc. *rossē meant 'dew, spray (of fall or fountain)'. Elrond and Elros, children of Eärendil (sea-lover) and Elwing (Elf-foam), were so called, because they were carried off by the sons of Fëanor, in the last act of the feud between the high-elven houses of the Noldorin princes concerning the Silmarils; the Silmaril rescued from Morgoth by Beren and Lúthien, and given to King Thingol Lúthien's father, had descended to Elwing dtr. of Dior, son of Lúthien. The infants were not slain, but left like 'babes in the wood', in a cave with a fall of water over the entrance. There they were found: Elrond within the cave, and Elros dabbling in the water.

The Silmarillion

Now when first the tidings came to Maedhros that Elwing yet lived, and dwelt in possession of the Silmaril by the mouths of Sirion, he repenting of the deeds in Doriath withheld his hand. But in time the knowledge of their oath unfulfilled returned to torment him and his brothers, and gathering from their wandering hunting-paths they sent messages to the Havens of friendship and yet of stern demand. Then Elwing and the people of Sirion would not yield the jewel which Beren had won and Luthien had worn, and for which Dior the fair was slain; and least of all while Earendil their lord was on the sea, for it seemed to them that in the Silmaril lay the healing and the blessing that had come upon their houses and their ships. And so there came to pass the last and cruellest of the slayings of Elf by Elf; and that was the third of the great wrongs achieved by the accursed oath.

For the sons of Feanor that yet lived came down suddenly upon the exiles of Gondolin and the remnant of Doriath, and destroyed them. In that battle some of their people stood aside, and some few rebelled and were slain upon the other part aiding Elwing against their own lords (for such was the sorrow and confusion in the hearts of the Eldar in those days); but Maedhros and Maglor won the day, though they alone remained thereafter of the sons of Feanor, for both Amrod and Amras were slain. Too late the ships of Cirdan and Gil-galad the High King came hasting to the aid of the Elves of Sirion; and Elwing was gone, and her sons. Then such few of that people as did not perish in the assault joined themselves to Gil-galad, and went with him to Balar; and they told that Elros and Elrond were taken captive, but Elwing with the Silmaril upon her breast had cast herself into the sea.

Thus Maedhros and Maglor gained not the jewel; but it was not lost. For Ulmo bore up Elwing out of the waves, and he gave her the likeness of a great white bird, and upon her breast there shone as a star the Silmaril, as she flew over the water to seek Earendil her beloved. [...]

Great was the sorrow of Earendil and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons, and they feared that they would be slain; but it was not so. For Maglor took pity upon Elros and Elrond, and he cherished them, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maglor’s heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath.

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

no one ever talks about the wild ass experience that is reading ALL of great tales immediately after silm and then trying to be a functioning member of this fandom. like i don’t know what canon is anymore i don’t know what’s headcanon what’s fanon what’s earlier draft what’s silm canon and what’s something christopher tolkien said in his unfinished tales footnotes. was daeron luthien’s brother or in love w her?? melko or melkor, maidros or maedhros?? tevildo canon?? legolas of gondolin?? idek anymore bro.

#rereading silm after GT is a MUST#and i have yet to do it#great tales#silm#silmarillion#silm fandom#the fall of gondolin#Children of Hurin#beren and luthien#the silmarillion#unfinished tales#feanorians#lay of leithian

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comparing the Captures of Maedhros and of Húrin thoughout versions

Note: I did not include all volumes of HoME in this however with the exception of Volume Eleven which contains The Wanderings of Húrin there are few meaningful differences. I will make a later post for more HoME content

Second note: I also have a post comparing the fates of Morwen, Aerin post Nírnaeth and Dor-lómin generally which I also will work on to revise and republish

It is notable to me that Húrin and Maedhros are among the only named figures Morgoth successfully orders the capture of by name. I wanted to explore the similarites and differences between varying versions.

Here are the two that are probably considered most canonical, from The Silmarillion and The Children of Húrin respectively

Maedhros was ambushed and all his company were slain but he himself was taken alive by the command of Morgoth and brought to Angband (The Return of the Noldor, The Silmarillion)

...but they took him at last alive by the command of Morgoth who thought thus to do him more evil than by death (The Battle of Unnumbered Tears, The Children of Húrin)

Morgoth’s intentions for Húrin are far more clear than for Maedhros. He knows ( “by his art and his spies”) that Húrin had the friendship of the King (Turgon in this case). It’s not entirely clear yet if Morgoth has heard rumors that Húrin had been to Gondolin but he certainly knows of the brothers reunion on the battlefield with Turgon and makes some quick connections. The conversation between Húrin and Morgoth spans almost the entirety of chapter three and has some of the most dialogue for Morgoth in the entire Legendarium

@tolkien-feels once made a joke about the conversations between Túrin and Sador in chapter one being like forced to go through the Athrabeth with a child and I think The Words of Húrin and Morgoth function almost in a similar way; some of the deeper philosophical questions of the universe involving mortality and fate and the reach of the gods are raised in these horrifying circumstances.

(I won’t go into it too much here because there is so much to say about this, but I’ll link a couple of my posts on it just for my own reference and organization here and here

Morgoth certainly tried to use the capture of Maedhros to his own advantage when he sends word to his brothers claiming he’d release him if they retreated but this attempt is rather perfunctory and I don’t think he truly thought it would go anywhere. At best, the Fëanorians might be spurred or goaded into further recklessness trying to recover Maedhros. At worst, nothing would happen for some time.

A fascinating difference between the notes of Tolkien that later became this part of the published Silmarillion is that in the original notes, two more words are added to the quote above. Maidros was ambushed, and all his company was slain, but he himself was taken alive by the command of Morgoth, and brought to Angband and tortured. (HOME V, p. 274)

In the version in the Book of Lost Tales, Maedhros is captured at the gates of Angband during a siege. He is tortured for information on jewel making, no word given on the success of this interrogation, and then released alive though maimed in an eerily vague afterthought. I have more on this in my BoLT tag, I find it fascinating for the ways it mirrors Húrin’s release in later canon

In the Lays of Beleriand Maedhros is mentioned only briefly though interestingly, most of his mentions include note of his torment, the most prominent appearing in The Lay of the Children of Húrin

in league secret

with those five others, in the forests of the East

fell unflinching foes of Morgoth

Maidros whom Morgoth maimed and tortured

is lord and leader, his left wieldeth

his sweeping sword

Both the use of the name Maidros as well as the specifications of ‘maimed and tortured’ appear to take after the Book of Lost Tales version however the Lays goes further and confirms that the maiming left so vague in BoLT did indeed include the loss of Maedhros’s right hand. And of course it’s notable that Morgoth did this, not Fingon during rescue.

Húrin‘s capture and imprisonment remain fairly consistent throughout the more known versions of the story, that is, in the Silm, in the Narn, and in the unfinished tales. Even in BoLT and the Lays the general outline is similar. In the Silm and the Narn, the story is consistent though of course much is cut out in the Silm version. Unfinished Tales has no significant changes to this section of the text.

In BoLT which is not considered canon, Úrin as he’s called there is captured during battle and both threatened with torture and offered great riches to betray Turondo (Turgon). When he refuses, Melko sets him in a ‘lofty place of the mountains’ and curses him to watch the doom of Morwen and his children.

(”at least none shall pity him for this, that he had a craven for a father”). Húrin has not been to Gondolin in this version.

This version is notable in this regard for a few things:

One, Morgoth spends far less time with Húrin and no mention of physical torture apart from threats of it is noted prior to his imprisonment in the mountains and the curse.

Two, the actual dialogue between them is rather different and briefer. Morgoth tries to take advantage of the poorer views by the elves towards humans by offering employment to Húrin but without success.

The version in the Lay of the Children of Húrin is more similar to the Narn and Silm. There is more extended contact between Morgoth and Húrin (though the contents of their talk is still different). It’s also perhaps the most vivid in descriptions of torture and imprisonment and the only version where actual methods of torment are mentioned or implied (namely whips and brands).

I definitely want to go into this version more later! As always please feel free to ask more! I will also go into more versions throughout HoME of both these storylines if there’s interest!

Final notes:

No version of Húrin in Angband will be as disturbing to me as Húrin’s imprisonment by his own kin in Brethil in The Wanderings of Húrin

#the silmarillion#the children of húrin#maedhros#Húrin#in the iron hell#musing and meta#BoLT#HoME#the lays of beleriand

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Obscure Tolkien Blorbos Tournament!

@mistergandalf's incredible Ultimate Tolkien Blorbo tournament has just wrapped up with our beloved Sam Gamgee taking the final trophy. But! Earlier rounds in the tournament were filled with a lot of weeping and gnashing of teeth from Silmarillion fans as our favourites were UNFAIRLY ELIMINATED by people who DIDN'T KNOW ABOUT THEM. So, I would like to present: the ultimate obscure Tolkien blorbos tournament!

Submit as many of your dubiously canonical, little-known faves as you'd like to - with a catch: characters with the fewest submissions are most likely to qualify for the bracket! With exactly one exception who is qualifying anyway because I say so.

Rules:

The character you submit can be part of Tolkien's legendarium in any way possible - discarded characters from earlier drafts, adaptation-only characters (RoP inclusive), etc.

No OCs.

Canonically unnamed characters (for example Curufin's wife) are eligible. But don't submit fan-invented names for them, or I won't know whom you're talking about!

If they're very obscure, do consider writing a couple of lines to tell me who they are! I'm not a HoME expert and won't be familiar with everyone you send in.

I reserve the right not to include characters who I don't think really count: you can't, for example, submit "Maidros" and then argue that that's a completely different character to the more well-known Maedhros.

Actual voting will just be a straightforward "vote for whomever you like more" process, nothing to do with how obscure the blorbos are at that stage.

Let's... tentatively say the bracket will contain 64 characters? I'll keep the form open at least until Sunday 21st May and potentially longer, depending on how much interest this gets.

This is my first time running a tournament and I have no idea what else to actually say or how to do this lol. Tag will be #obscure tolkien blorbo, feel free to follow/block it as you prefer.

Let me know if you have any more questions, reblog for visibility, and happy submitting! And feel free to drop your submissions in the tags to this post so that people can avoid double-nominating their faves :)

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the versions of Celegorm and Curufin's actions during the Bragollach, for my own future reference. I mean to write a meta on them at some point, but that might morph into a broader one on the Bragollach as a whole.

Takeaway: Celegorm and Curufin always head towards the Finarfinians and never towards their brothers, even though they would have been able to (in the versions where they head south then west in particular, where they would have numerous options for further travel). In many versions, this is explicitly because of their friendship with Orodreth. (I say versions, but the actions are pretty consistent - defend Aglon till they need to retreat, head towards Orodreth and/or Nargothrond)

I think this is very interesting and has implications for various intra-Finwean and intra-Feanorian dynamics.

The textual history of the material that became the Silmarillion is... complex. I present the different versions in the order they appear in HoME, which semi-corresponds to when Tolkien probably wrote them. I omit the very earliest version, "The Earliest 'Silmarillion'" in SoME.

The Silmarillion:

For the war had gone ill with the sons of Fëanor, and well nigh all the east marches were taken by assault. The Pass of Aglon was forced, though with great cost to the hosts of Morgoth; and Celegorm and Curufin being defeated fled south and west by the marches of Doriath, and coming at last to Nargothrond sought harbour with Finrod Felagund. Thus it came to pass that their people swelled the strength of Nargothrond; but it would have been better, as was after seen, if they had remained in the east among their own kin.

Shaping of Middle-earth pg 128, the Quenta:

Then Felagund went South [after being saved by Barahir during the Bragollach], and on the banks of Narog established after the manner of Thingol a hidden and cavernous city, and a realm. Those deep places were called Nargothrond. There came Orodreth after a time of breathless flight and perilous wanderings, and with him Celegorm and Curufin, the sons of Fëanor, his friends. The people of Celegorm swelled the strength of Felagund, but it would have been better if they had gone rather to their own kin, who fortified the hill of Himling east of Doriath and filled the Gorge of Aglon with hidden arms.

SoME pg 357, the Earliest Annals of Beleriand (in this version, Orodreth holds lands in Dorthonion, right next to Celegorm and Curufin):

Here were Bregolas slain, and the greater part of the warriors of Bëor’s house. Angrod and Egnor sons of Finrod fell. Barahir and his chosen champions saved Felagund and Orodreth, and Felagund swore a great oath of friendship to his kin and seed. […] The sons of Fëanor were not slain, but Celegorm and Curufin were defeated and fled with Orodreth son of Finrod. Maidros the left-handed did deeds of great prowess, and Morgoth did not take Himling as yet, but he broke into the passes east of Himling and ravaged into East Beleriand and scattered the Gnomes of Fëanor’s house.

LR pgs 132 - Later Annals of Beleriand

The sons of Feanor were not slain, but Celegorm and Curufin were defeated, and fled unto Orodreth in the west of Taur-na-Danion.

LR pg 147 - in the footnotes, Christopher notes that his father changed the above line on pg 132 to:

Celegorm and Curufin were defeated, and fled south and west, and took harbour at last with Orodreth in Nargothrond.

LR pgs 282-283 - Quenta Silmarillion

For the war had gone ill with the sons of Feanor, and well night all the east marches were taken by assault. The pass of Aglon was forced, though with great cost to Morgoth; and Celegorm and Curufin being defeated fled south and west tby the marches of Doriath and came at last to Nargothrond, and sought harbor with their friend Orodreth. Thus it came to pass that the people of Celegorm swelled the strength of Felagund, but it would have been better, as after was seen, if they had remained in the East among their own kin.

LR pg 289-290 Christopher’s commentary on the previous paragraph where he’s comparing different manuscripts. Inglor is Finrod.

It is said in QS 117 that after the founding of Nargothrond Inglor Felagund committed the tower of Minnastirith to Orodreth; and later in the present chapter QS 143 it is recounted how Sauron came against Orodreth and took the tower by assault (the fate of the defenders is not there mentioned). The statement here that Celegorm and Curufin ‘sought harbour with their friend Orodreth’ — rather than ‘sought harbour with Felagund’ — is found also in an emendation to AB 2 (note 25); the implication is that Orodreth reached Nargothrond before them, and that their friendship with him was the motive for their going to Nargothrond. This friendship survived the change of Orodreth’s lordship from the east of Dorthonion (‘nighest to the sons of Feanor’, AB 2 annal 52 as originally written) to wardenship of the tower on Tol Sirion. The sentence ‘the people of Celegorm swelled the strength of Felagund, but it would have been better […] if they had remained in the East among their own kin’ goes back to Q ([HoME] IV 106), though in Q Celegorm and Curufin came to Nargothrond together with Orodreth.

WotJ 53, 54 - the Grey Annals (Celegorm is referred to as Celegorn throughout; Cranthir, Damrod, and Diriel are Caranthir, Amrod, and Amras. Inglor is Finrod)

Celegorn and Curufin held strong forces behind Aglon, and many horsed archers, but they were overthrown, and Celegorn hardly escaped, and passed westward along the north borders of Doriath with such mounted following as they could save, and came thus at length to the vale of Sirion. […] Morgoth […] sent a great force to attack the westward pass into the vales of Sirion; and Sauron his lieutenant (who in Beleriand was named Gorsodh) led that assault, and his hosts broke through and besieged the fortress of Inglor, Minnas-tirith upon Tolsirion. And this they took after bitter fighting, and Orodreth the brother of Inglor who held it was driven out. There he would have been slain, but Celegorn and Curufin came up with their riders, and such other force as they could gather, and they fought fiercly, and stemmed the tide for a while; and thus Orodreth escaped and came to Nargothrond. Thither also at last before the might of Sauron fled Celegorn and Curufin with small following; and they were harboured in Nargothrond gratefully, and the griefs that lay between the houses of Finrod and Feanor were for that time forgotten.

WotJ pg 239-240- the Later Quenta Silmarillion. Christopher is presenting the emendations his father made to the Quenta Silmarillion manuscript published in LR.

Celegorn and Curufin … sought harbour with their friend Orodreth > ‘… sought harbour with Inglor and Orodreth.’ > ‘sought harbour with Finrod and Orodreth.’

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s interesting how many of the mothers in Tolkien are so ... sad? I’m calling them the Sad Mums Club. There are others I could have potentially included in this list, but I chose these seven because their sadness is explicitly tied in some way to their children, whether it be exhaustion from birth, fear for their children, giving birth alone after the loss of a partner, or something else. I’m not entirely sure what to make of these parallels, but I do find them interesting.

Miriel - “In the bearing of her son Miriel was consumed in spirit and body; and after his birth she yearned for release from the labour of living.” - The Silmarillion.

Elwing - “for Elwing seeing that all was lost and her children Elros and Elrond taken captive, eluded the host of Maidros, and with the Nauglafring upon her breast she cast herself into the sea.” - Quenta Noldorinwa.

Idril - “Idril fell into a dark mood, and the light in her face was clouded, and many wondered thereat [...] she said to him how her heart misgave her for fear concerning Earendel their son, and for boding that some great evil was nigh.” - The Fall of Gondolin.

Gilraen - “Ónen i-Estel Edain, ú-chebin estel anim” - meaning “I gave hope to the Dunedain, I have kept none for myself.” - LOTR Appendices.

Mithrellas - “But when she had borne [Imrazor] a son, Galador, and a daughter, Gilmith, she slipped away by night and he saw her no more.” - Unfinished Tales.

Morwen - “Morwen gave birth to her child, and she named her Nienor, which is Mourning.” - The Children of Hurin.

Rian - “When her child Tuor was born [the Grey Elves of Mithrim] fostered him. But Rian went to the Haudh-en-Nirnaeth, and laid herself down there, and died.” - The Children of Hurin.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Maidros the cat#cat#caturday#kitten#kitty#ginger cat#ginger kitten#cute#Maedhros#Silmarillion#the Silmarillion

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maidros appreciation post. Look at those eyes ♥️

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think part of what troubles me about the opinion that Maglor and Maedhros were the “best” people to raise Elrond and Elros is that many (though not all) such interpretations often refer to fanon interpretations as if they were canon. Which there’s nothing wrong with enjoying fanon! But when popular fanon starts being treated as a definitive canon and subsequently starts being used as a lens for textual interpretation and engagement (and in some extreme cases, an excuse for bashing other characters), that’s when it gets a little eyebrow-raising.

So in this post, I’m going to examine some of the more common fanon beliefs and headcanons around Maglor and Maedhros as parental figures/guardians to Elros and Elrond. The point is not to debunk them and say that you cannot interpret the texts this way or enjoy them as a fan reading. Indeed, if there was no textual or analytical basis for these headcanons altogether, they would not exist. Neither is this meant to bash anyone. Rather, I’d like to show that many of the assumptions we hold are nowhere near as solid or definitive as they sometimes seem to be, and that there is in fact room for a plurality of different headcanons and readings to coexist without elevating one over the other.

1. Maedhros and Maglor were both involved in Elros and Elrond’s upbringing.

As the wealth of Kidnap Fam content demonstrates, this is a very common headcanon. However, let’s look at what the Silmarillion says. Bolding is mine for emphasis.

For Maglor took pity upon Elros and Elrond, and he cherished them, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maglor’s heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath. (”Of the Voyage of Eärendil”)

Nowhere is Maedhros mentioned. He is mentioned in the version of the story included in The Fall of Gondolin, where the passage instead reads:

For Maidros took pity on Elrond, and he cherished him, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maidros’ heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath. (”The Conclusion of the Quenta Nolodrinwa”)

Christopher Tolkien’s commentary directly interjects after this to observe that the passage was rewritten to be the version in the published Silmarillion, which is an interesting distinction to make when the entire version of the story it comes from is very different from the one in the Silmarillion; it is also worth noting that apart from changing which Son of Fëanor it was, Tolkien kept this passage nearly verbatim in the Silmarillion.

Maedhros is also mentioned in the preceding chapter, in Tolkien’s sketch of the mythology, with the line:

Their [Eärendel and Elwing] son Elrond who is part mortal and part elven, a child, was saved however by Maidros. (”The Conclusion of the Sketch of the Mythology”)

So yes, there was once a version of the story in which Maedhros was the one who spared Elrond (Elros did not yet exist, at least not as Elrond’s brother, at this point in Tolkien’s thinking). This version of the story differs quite significantly from the published version in the Silmarillion; as Christopher Tolkien comments, the Silmarils were of much less significance and had differing fates (Beren and Lúthien’s Silmaril was lost in the Sea after Elwing threw it in, Maglor threw another into a fiery pit, and the third was taken from Morgoth’s crown and launched into the outer darkness by Eärendil). Also notably, Eärendil does not intercede on behalf of Middle-earth before the Valar.

Of course, being a Tolkien fan pretty much entails picking and choosing which bits of the Legendarium you like. If you want to take Tolkien’s original thinking that it was Maedhros rather than Maglor who cherished Elrond and Elros, and mix that with the more common version of events in the Silmarillion, go wild. You can say that the narrator is unreliable, that it makes logical sense for Maedhros to be involved, or that it’s simply more fun to imagine domestic shenanigans with the last two Sons of Fëanor. But there’s a difference between blending versions of the story as your own personal headcanon, and asserting that headcanon as the one true fanon.

It is also interesting to observe that at no point are both brothers mentioned in relation to Elrond and Elros; it is either Maglor or Maedhros. The version in The Fall of Gondolin has Maglor sitting by the Sea and singing in regret after the Third Kinslaying while Maidros saves Elrond; in the Silmarillion, it is only Maglor who takes pity on Elrond and Elros.

2. No one else cared about Elros and Elrond; only Maedhros and Maglor did.

Very explicitly in The Silmarillion, “Great was the sorrow of Eärendil and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons, and they feared that they would be slain...” (”Of the Voyage of Eärendil”). But we also read:

Too late the ships of Círdan and Gil-galad the High King came hasting to the aid of the Elves of Sirion; and Elwing was gone, and her sons. Then such few of that people as did not perish in the assault joined themselves to Gil-galad, and went with him to Balar; and they told that Elros and Elrond were taken captive, but Elwing with the Silmaril upon her breast had cast herself into the sea. (”Of the Voyage of Eärendil”)

Again, bolding is mine for emphasis.

What we see in the Silm version of the story is that 1) when Sirion was attacked, Círdan and Gil-galad raced to help but were too late, 2) a very large percentage of the population of Sirion died in the Kinslaying, and 3) those who survived reported that Elros and Elrond had been taken captive. That’s it.

True, there is no mention of any rescue attempts or negotiations, but there also isn’t mention of anything else because at this point, the narrative returns to Eärendil. Which makes sense, because the voyage of Eärendil is the whole entire point of the chapter, and arguably the climax of the version of the narrative that’s in The Silmarillion. It’s not “Of the Captivity of Elros and Elrond,” or “Of the Third Kinslaying,” the main focal point of the story is Eärendil sailing to Aman and pleading for all the people of Middle-earth.

There’s also another version of this story in The Fall of Gondolin, where we read:

...but the folk of Sirion perished or fled away, or departed of need to join the people of Maidros, who claimed now the lordship of all the Elves of the Hither Lands. (”The Conclusion of the Quenta Noldorwa”)

In this version, the survivors do not go to Gil-Galad, but either flee or join Maedhros who now claims lordship of all the Elves. If you go by this story, then there really is very little possibility of a rescue, since 1) Maedhros is now the most powerful lord among the Elves and claims authority over all who are left, where would they even go if they got away, and 2) it would therefore be a betrayal to stand against or attack one’s lord. It also opens up the possibility that Elrond (this is the version without Elros) had other survivors of Sirion around him while he was a captive, and was therefore not alone.

What all this means though is that we can headcanon whatever we like regarding what happens in Beleriand during this time, but we really don’t have enough information to definitively say what did or did not happen. And what information we do have in The Silmarillion at least suggests that Círdan and Gil-galad cared about the people of Sirion and tried to help them, and also that the people of Sirion were not in great shape to be mounting any sort of attack on Maedhros and Maglor.

Also, just because someone who survives a horrifically traumatic mass murder which killed nearly everyone they knew does not immediately go out and fight for the well-being of other survivors, it does not therefore mean that they don’t care about them or that they care less than the perpetrators.

3. Maglor raised Elros and Elrond to adulthood.

This is another one of those instances where the absence of evidence does not make a positive. We don’t actually know for certain how long Elros and Elrond were with Maglor. In the early letter where Elros and Elrond are found in a cave, it is implied there that they were left there by the sons of Fëanor after they were taken captive, and later found by other, unspecified Elves. In another version, in The Fall of Gondolin, it reads:

Yet not all would forsake the Outer Lands where they had long suffered and long dwelt; and some lingered many an Age in the West and North, and especially in the western isles. And among these were Maglor as has been told; and with him Elrond Half-elven, who after went among mortal Men again... (”The Conclusion of the Quenta Nolodrinwa”)

This is also the version of the story where Elros does not exist and it is “from [Elrond] alone the blood of the Firstborn and the seed divine of Valinor have come among Mankind” (”The Conclusion of the Quenta Nolodrinwa”).

Then there’s also this which Elrond says in Fellowship of the Ring:

Thereupon Elrond paused a while and sighed. ‘I remember well the splendour of their banners,’ he said. ‘It recalled to me the glory of the Elder Days and the hosts of Beleriand, so many great princes and captains were assembled. And yet not so many, nor so fair, as when Thangorodrim was broken, and the Elves deemed that evil was ended for ever, and it was not so.’ (”The Council of Elrond”)

What we see is that Elrond, at least, witnessed the end of the War of Wrath, including the breaking of Thangorodrim. Then there is this passage from the Silmarillion:

Of the march of the host of the Valar to the north of Middle-earth little is said in any tale; for among them went none of those Elves who had dwelt and suffered in the Hither Lands, and who made the histories of those days that still are known; and tidings of these things they only learned long afterwards from their kinsfolk in Aman. (”Of the Voyage of Eärendil”)

In most versions of the story, the Elves who lived in Beleriand took part in the major conflicts of the War of Wrath. Men do -“And such few as were left of the three houses of the Elf-friends, Fathers of Men, fought upon the part of the Valar...” (”Of the Voyage of Eärendil”)- but very clearly no Elves. So Maedhros and Maglor did not participate in or witness the main battles of the War of Wrath, but according to Lord of the Rings (which I would argue holds the “most canonical” status over every other text in the Legendarium) Elrond was there to remember firsthand, if not take part in, major events in the War, suggesting that they were no longer together at that point (which does not preclude Elrond returning to them afterwards, though it would be a very tight timetable with the Fourth Kinslaying).

Returning to the original point, Elros and Elrond could very well have stayed with Maglor until they were grown, even up to and beyond the Choice. They could equally have left Maglor and Maedhros at any point, or Maglor could have left them with their other kin. Tolkien changed his mind a lot about the details of the end of the First Age! There are a good number of different canons, to say nothing of opportunities for different headcanons.

4. Elros and Elrond turned out to be great people which is all down to Maglor (and Maedhros)’s childrearing (and therefore they were the best possible people to raise them).

Hear the sound of that old familiar bell ringing again? Absence of evidence one way does not mean that another way is automatically true! We actually don’t have any information at all about how Maglor brought them up, only that emotionally, there was some element of mutual love in the relationship. We don’t know for certain how long Elros and Elrond were with Maglor (a few months? a few years? all the way to adulthood?) and we don’t know how or what sort of things Maglor taught them or to what degree they absorbed those lessons.

Yes, Elros and Elrond became great people. But there is simply too great a gap of information to correlate (either positively or negatively) all their future deeds and character to Maglor (and/or Maedhros)’s upbringing. Not to mention, people are not only the products of the people who raised them. So many people influence us on a daily basis, from friends to coworkers to enemies. While Maglor (and Maedhros) doubtless did have an influence on how E&E grew up and who they became, it seems a little reductive to credit them as the defining factor in Elros and Elrond’s morality or greatness, when both of them (E&E) lived very long lives for their respective fates and met many people and experienced many things.

Narrative Analysis: What’s this about themes?

Textual analysis aside, there’s one other factor which I think is missing in a lot of these discussions, which is genre. The Legendarium is full of tragedy. Good people make bad decisions, or suffer (often unjustly) the consequences of another person’s decisions. People are placed in terrible situations where there is no “good” or “right” decision, where anything they choose has tragic consequences. Sometimes people make decisions believing that it is justified or for good, only to discover that it was very much the opposite. Sometimes people know that what they are choosing will hurt them or others, but for one or many reasons, they do it anyways.

The point being that many of the characters Tolkien wrote are purposefully nuanced and tragic. Yes, there’s a Dark Lord and some very terrifying spiders who are unequivocally evil, but otherwise, nearly every character is some shade of grey. Characters make decisions with both positive and negative consequences; they exist simultaneously as figures of both heroism and antagonism. In short, they’re complex! That’s why they’re so compelling and enjoyable!

So why set up a dichotomy of “So and so is better than so and so”? Rather than pitting the sons of Fëanor as “the best” in comparison to other characters, why not embrace the complexity of the narrative?

In order to save the entire world, Eärendil and Elwing had to leave their young children forever. They could have decided to go back and try to rescue their children, and in doing so they would have also doomed the entire world. Whatever they chose, someone would suffer for it. It’s a question that we see explored a lot in fiction but which most of us will never have to confront ourselves: if you were in a position where you had to choose between your loved ones and the fate of the world, which would you choose?

Maglor, a character who has acted almost exclusively as a follower throughout most of the narrative, for once realized the consequences of his actions and, crucially, took active responsibility by caring for and cherishing the children he kidnapped. It does not absolve him of responsibility for the Kinslayings because children are not tools to redeem the adult figures in their lives, and in any case, it is a fruitless pursuit to attempt to moralize fictional characters existing in a very particular setting and narrative. However, it is a significant moment in his character arc, especially as we afterwards see him begin to openly contradict and disagree with Maedhros, multiple times within the same chapter after being a relatively silent follower throughout the narrative. Which makes it all the more tragic later when he slays the guards with Maedhros and steals the Silmarils because we know now that he did not want to, that he might have chosen differently, but ultimately he did not.

Maedhros knew that the kinslayings were wrong and repented of them, and did not attack Sirion for many years. However, he still did it in the end. *mumbles in V for Vendetta “I have not come for what you hoped to do, I have come for what you did do”* He did not kill Elrond and Elros, and in some early versions of the story, was indeed the one to save them rather than Maglor. He also continued to kill in the name of the Oath. Rather than isolating any one of these things as proof of goodness or badness, all of them work together as part of his tragic figure - a prince, once great, with good intentions, who has fallen to such a point in his life that all he can see around him anymore is death and despair.

(On a side note, Maedhros-Hamlet AU when)

Elros and Elrond were young children who survived a horrifically traumatic event. They were able to develop some sort of loving relationship with Maglor (or Maedhros), and as adults, they took pride in Eärendil and Elwing as their parents. Rather than pitting Maglor against Eärendil and Elwing, is it not more important that amidst the apocalyptic horrors of late First Age Beleriand, Elros and Elrond had adult figures in their lives who loved them and cherished them, both before and after the Kinslaying? Love is not the only important thing in the world, of course, and it is not meant to justify any of the actions taken by the aforementioned adults. But. Amidst the tragedy of the broken world they lived in, they were loved.

Summary: Headcanons are great and can co-exist with each other

Not to belabour the point, but there is really so much we do not know about the end of the First Age. Tolkien changed and developed his thoughts on his world throughout his life, and even with what he did set down in writing, there are plenty of gaps where we can only guess. That’s part of what makes the Legendarium so fun to engage with as readers!

With all that in mind, there’s nothing wrong with having a preferred version of the story or a favourite set of headcanons, so long as we acknowledge that they are not the only way to engage with the text. Furthermore, fiction and fan engagement is not meant to be about the moral high ground. Especially with the complex characters and world that Tolkien created, you don’t need to put down other characters or narratives in order to justify your preferred reading. It’s First Age Beleriand! To modify a parlance from Reddit, Everyone Sucks At Least a Little Bit Here. Characters can have good intentions with tragic consequences, make bad decisions but have some good come out of it nonetheless, or do things which have both positive and negative impacts.

Eärendil and Elwing do not need to be horrible or unfit parents in order for Maglor and/or Maedhros to genuinely pity and cherish Elros and Elrond. Those are separate relationships with no correlation. And none of them need to be perfect parental figures in order for Elros and Elrond to have real loving relationships with all of them. It’s not a competition for who can “best” raise Elros and Elrond or who loves them “the most.” You can love Maglor and Maedhros as good parents! There’s just no need to go putting anyone else down, or to treat it as the one definitive interpretation of the characters and the story.

#lotr#silmarillion#i cannot emphasize enough that this is not a personal criticism of anyone or anything#but rather meant to show how the legendarium allows for a plurality of readings and engagement#and that we don't need to Discourse over which character is better or what reading is superior#we can interpret and engage with the legendarium in different ways without putting anyone or anything else down#also; if you really dislike a character and would just like to vent about them; please tag it appropriately with an anti- tag!#it's so disheartening to go into the main tag and see an untagged post bashing a character you like

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

112 notes

·

View notes