#marathon athens greece

Text

The Athenian Messenger Pheidippides Delivers News of the Victory at Marathon

by Frank Moss Bennett

#pheidippides#art#frank moss bennett#marathon#messenger#victory#battle of marathon#athens#athenian#history#ancient greece#ancient greek#greek#greece#persian#invasion#persia#europe#european#battle#war#classical antiquity#antiquity#ancient#run#runner#race#running

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persian Fire by Tom Holland

What a terrific read! Although in truth, I actually listened to half the book as another of my freebies from Audible. I had heard of the battle of Marathon and, through one of my fave films, The 300, knew about the battle at Thermopylae and this book covers them both.

Themistocles, Xerxes, Salamis, Athens, Thebans, Argives, Pericles, Sparta and Spartans etc, the heroes, villains and locations of the piece whose names we have come across but didn’t necessarily know come to life in this non-fiction book, that reads like a novel.

Highly recommend.

#books#review#history#Persian fire#tom holland#persian empire#ancient greece#Persia#greece#Sparta#marathon#thermopylae#xerxes#athens#spartan#audible#the 300

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

a post in honor of lord byron's 200th death anniversary —

the greeks were very fond of byron, who when he died in 1824 was a military commander and notable influence in their war of independence. as one of the most (if not the most) famous members of the philhellenist movement, byron used his poetic platform to try to remind people of greece's reputation as the source of western traditions in art and culture. the greeks then honored byron by decorating his coffin with a laurel wreath (below). they also erected statues for him, like this one below in athens depicting him being crowned with a laurel wreath (a symbol of greatness, especially in poetry/music [which historically overlapped]) by a female personification of greece. to this day, some statues of byron are annually wreathed in tradition, and the names byron/vyron/vyronas are still used in greece for roads, towns, and people in his honor.

"’Tis sweet to win, no matter how, one’s laurels,

By blood or ink; ’tis sweet to put an end

To strife; ’tis sometimes sweet to have our quarrels,

Particularly with a tiresome friend:

Sweet is old wine in bottles, ale in barrels;

Dear is the helpless creature we defend

Against the world; and dear the schoolboy spot

We ne’er forget, though there we are forgot.

But sweeter still than this, than these, than all,

Is first and passionate love — it stands alone,

Like Adam’s recollection of his fall;

The tree of knowledge has been pluck’d — all ’s known —

And life yields nothing further to recall

Worthy of this ambrosial sin, so shown,

No doubt in fable, as the unforgiven

Fire which Prometheus filch’d for us from heaven."

— excerpt from Lord Byron's Don Juan, Canto the First (writ 1818, pub. 1819).

"The mountains look on Marathon –

And Marathon looks on the sea;

And musing there an hour alone,

I dreamed that Greece might still be free;

For standing on the Persians' grave,

I could not deem myself a slave."

— excerpt from Lord Byron's Don Juan, Canto the Third (writ 1819, pub 1821) — this stanza is part of a section often published on its own under the title "The Isles of Greece."

"Byron was at once a romantic dreamer, who wanted life to square up to his illusions, and a satirical realist, who saw what was before him with unusual clarity and found its contradictoriness amusing. The clash between the two Byrons is nowhere more noticeable than in his last writings, done on Cephalonia and at Missolonghi during the months before his death. There we see the Greece he dreams of, and the Greece which, in different ways, destroys him."

— excerpt from Peter Cochran's "Byron's Writings in Greece, 1823-4."

"Oh, talk not to me of a name great in story;

The days of our youth are the days of our glory;

And the myrtle and ivy of sweet two and twenty

Are worth all your laurels, though ever so plenty.

What are garlands and crowns to the brow that is wrinkled?

'Tis but as a dead-flower with May-dew besprinkled.

Then away with all such from the head that is hoary!

What care I for the wreaths that can only give glory!

Oh FAME! - if I e'er took delight in thy praises,

'Twas less for the sake of thy high-sounding phrases,

Than to see the bright eyes of the dear one discover,

She thought that I was not unworthy to love her.

There chiefly I sought thee, there only I found thee;

Her glance was the best of the rays that surround thee;

When it sparkled o'er aught that was bright in my story,

I knew it was love, and I felt it was glory."

— Lord Byron's "Stanzas Written on the Road Between Florence and Pisa" (November, 1821). What is illustrated here, and what I try to illustrate all throughout this assortment, is Byron's conflation of love and glory, and the idea that poetry and politics are both ways to deserve and achieve — not fame, but what fame seems to promise — love.

"But 'tis not thus—and 'tis not here

Such thoughts should shake my Soul, nor now,

Where Glory decks the hero's bier,

Or binds his brow.

The Sword, the Banner, and the Field,

Glory and Greece around us see!

The Spartan borne upon his shield

Was not more free.

Awake (not Greece—she is awake!)

Awake, my Spirit! Think through whom

Thy life-blood tracks its parent lake

And then strike home!"

— excerpt from Lord Byron's "On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sxith Year" (1824).

"What are to me those honours and renown

Past or to come, a new-born people's cry

Albeit for such I could despise a crown

Of aught save Laurel, or for such could die;

I am the fool of passion, and a frown

Of thine to me is as an Adder's eye

To the poor bird whose pinion fluttering down

Wafts unto death the breast it bore so high –

Such is this maddening fascination grown –

So strong thy Magic - or so weak am I."

— although the much more popular and published "On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sxith Year" is often believed to be Byron's last poem, the above is likely Byron's actual last poem. Like the former, it wasn't solely written for Greece, but for his page Lukas Chalandritsanos who he was in unrequited love (or lust) with. It is sometimes titled "Last Words on Greece" (named so by his friend and sometimes-editor Hobhouse).

#queud#literature#english literature#lord byron#romanticism#history#dark academia#poetry#aesthetic#greece#greek#greek history#poems#lit#on this day#byron#byronism#academia#greek war#war#web weaving

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corinthian helmet found with the soldier's skull still inside from the Battle of Marathon which took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece.

2,500 years ago, on the morning of September 12th, 10,000 Greek soldiers gathered on the plains of Marathon to fight the invading Persian army. The Greek soldiers were composed mostly of citizens from Athens as well as some reinforcements from Plataea. The Persian army had 25,000 infantrymen and 1,000 cavalry.

According to legend, a long-distance messenger by the name of Phidippides was sent to Athens shortly after the battle to relay the news of victory. It has been said that he ran the entire distance from Marathon to Athens, a distance of approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi), without stopping, and bursted into the assembly to declare, "We have won!", before collapsing and dying. This story differs quite a bit from Herodotus' account which mentions Phidippides as the messenger who ran from Athens to Sparta, and then back, covering a total distance of 240 km (150 mi) each way.

#history#sparta#spartan#this is sparta#persia#Greece#war#battle#lonely planet#vibes#good vibes#lifestyle#style#aes#aesthetic#aesthetics#helmet

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italian fascism was trying to defeat a nature [...] by declaring it a priority to civilize the marshes of the Pontine Plain. [...] The swampland was still the habitat of the anopheles mosquito and the dominion of the “Goddess of Fever.” [...] [A] flaw of a primal [...] nature, [...] unproductive [...]. The efforts to create “an idyllic rural area consonant with fascist ideals of productivity [...] within the state’s interests” included extensive electrification of the region, constructing thousands of kilometres of roads and canals and “large pumping and drainage plants called impianti idrovori (drainage pumping stations), in Italian literally ‘water-eating’ machinery plants,” founding an anti-malaria institute, having war veterans plant the region with water-absorbing [non-native] eucalyptus trees (these plants performed their job too well, which is why they were later torn out again at great expense [...]), stocking fish [...], establishing an anti-mosquito militia, and putting up children’s camps whose buildings were wrapped in ten layers of wire to protect them from mosquitoes. “The fascist emphasis on the technical and technological aspects of the land reclamation programme were also characteristic of a positivistic view of [technology and institutionalized knowledge] [...] aimed at controlling, rationalizing and ultimately creating an imperium over a previously unknown or ‘untamed’ area.”

Text by: Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal Issue #115. February 2021. [Bold emphasis added by me.]

---

On 24 December 1928 Italy’s fascist regime launched [...] a fourteen-year national land reclamation programme aimed at [...] Italy’s ‘death inducing’ swamps [...]. The Pontine Marshes, a marshland spreading across 75,000 hectares south of Rome was given top priority [...]. [T]he fascist regime used an extensive propaganda machinery to promote the programme [...] as a heroic quest [...]. Newsreels documented step by step the struggle [...], with Mussolini himself often featuring, overseeing the project, or even working the land. [...] This policy [...] aimed [...] [at] improving [...] existing cities by removing “unhealthy” urban areas, through the process of sventramento (disembowelment). [...] Indeed, the project exhibits many similarities in aims and scope to a number of modernising plans that were materialised across the world at around the same time: the Tuscan maremma (1928), a large scale coastal reclamation project; the Zuiderzee dyke project in Holland (1920-1932), which produced the Ijsselmeer, an enclosed area of water that would later host urban settlements [...]; Spain’s ambitious national hydrological plan that would “correct hydrologically the national geographical problem” by introducing a system of dams [...]; Switzerland’s Linth valley hydro engineering scheme that drained marshland and provided the geographical basis for a unified [nationalist] Swiss identity [...]; Greece’s Marathon dam project, that would produce Athens as a western sanitized metropolis [...]. All of these projects shared [...] the desire to link these socially constructed techno-natures to a broader project of promoting national unity and [nationalist] identity.

Text by: Federico Caprotti and Maria Kaika. “Producing the ideal fascist landscape: nature, materiality and the cinematic representation of land reclamation in the Pontine Marshes.” Social & Cultural Geography Volume 9. 2008. [Bold emphasis added by me.]

138 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Marathon: The Helmet With the Soldier’s Skull Still Inside

This remarkable Corinthian-style helmet from the Battle of Marathon was reputedly found in 1834 with a human skull still inside.

It now forms part of the Royal Ontario Museum’s collections, but originally it was discovered by George Nugent-Grenville, who was the British High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands between 1832-35.

A keen antiquarian, Nugent-Grenville carried out a number of rudimentary archaeological excavations in Greece, one of which took place on the Plains of Marathon, where the helmet was uncovered.

A pivotal moment in Ancient Greek history, the battle of Marathon saw a smaller Greek force, mainly made up of Athenian troops, defeat an invading Persian army.

There were numerous casualties, and it appears that this helmet belonged to a Greek hoplite (soldier) who died during the fighting of the fierce and bloody battle.

The Athenian army under General Miltiades consisted almost entirely of hoplites in bronze armor, using primarily spears and large bronze shields. They fought in tight formations called phalanxes and literally slaughtered the lightly-clad Persian infantry in close combat.

The hoplite style of fighting would go on to epitomize ancient Greek warfare.

Today the helmet and associated skull can be viewed at the Royal Ontario Museum’s Gallery of Greece.

Battle of Marathon saved Western Civilization

It was in September of the year 490 BC when, just 42 kilometers (26 miles) outside of Athens, a vastly outnumbered army of brave soldiers saved their city from the invading Persian army in the Battle of Marathon.

But as the course of history shows, in the Battle of Marathon, they saved more than just their own city: they saved Athenian democracy itself, and consequently, protected the course of Western civilization.

According to historian Richard Billows and his well-researched book Marathon: How One Battle Changed Western Civilization, in one single day in 490 BC, the Athenian army under General Miltiades changed the course of civilization.

It is very unlikely that world civilization would be the same today if the Persians had defeated the Athenians at Marathon. The mighty army of Darius I would have conquered Athens and established Persian rule there, putting an end to the newborn Athenian democracy of Pericles.

In effect, this would certainly have destroyed the idea of democracy as it had developed in Athens at the time.

The Battle of Marathon lasted only two hours, ending with the Persian army breaking in panic toward their ships with the Athenians continuing to slay them as they fled.

In his book, however, Billows calls the Battle of Marathon a “miraculous victory” for the Greeks. The victory was not as easy as it is often portrayed by many historians. After all, the Persian army had never before been defeated.

By Tasos Kokkinidis.

#Battle of Marathon: The Helmet With the Soldier’s Skull Still Inside#greek helmet#persian army#general miltiades#king darius i#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#long reads

87 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dr. Reames!! Oftentimes I see it mentioned that Alexander’s Persian campaign was framed at the time as a revenge against Persia for previous wars against Greece. And so, for example, the burning of Persepolis could be interpreted as payback for the burning of Athens.

But how accurate is that actually? I can only suppose that the top echelons of the Macedonian military establishment didn’t really feel that strongly about Greece as a whole (as Greece wasn’t a unified country like today), but had to frame it as such to disguise what could be seen as a shameless offensive land grab.

Even so, Alexander knew his propaganda. Was there a general feeling among the people of Greece and the rank and file troops that this campaign was a revenge for the previous wars Persia waged against Greece? Some sort of unifying spirit, ideal? And Alexander exploited this for his benefit? Or is this idea of a Greece vs Persia conflict a complete fabrication of misinterpretation?

The idea of a “Revenge against Persia” campaign was part of 4th century political discourse before Alexander, or even Philip. The question was who would lead such a campaign? Naturally, Athens thought they should, but after their defeat in the Peloponnesian War, didn’t have the military mojo. And even if Sparta had opposed the Persian invasion (alongside Athens), she owed her success in the Pel War to Persian assistance, so that was a problem. Thebes as a potential leader was even worse, as she’d Medized (went over to the Persians), so hell-to-the-no would she be appropriate.

Isokrates was probably the first to suggest it be Philip, as his star was rising. Yes, Macedon had also Medized, but Alexander I had been a clever man who played both sides against the middle and was able to burnish his rep after the war as “having no choice, and see? I helped Athens by providing her with timber for the Greek fleet”…if at, we’re sure, a substantial sum that benefited Maceon. But Macedon resented Persia too and had been a victim! It provided the plausible deniability needed to elevate Philip as leader of the Go-and-get-Persia campaign.

Of course Athens was not keen on this. She still thought SHE should be leading the vengeance war, as she won the two most significant battles of the Greco-Persian Wars (Marathon in #1 and Salamis in #2). That Philip was out-maneuvering her at every turn for the hegemony of greater Greece was additionally galling.

When Philip decided to invade Persia is a point of great contention, but I think he had it in mind by the time of his extensive Balkan campaign (c. 341/40/39. when Alexander was left in Pella as regent). Much of that was to secure the Black Sea coast and conquer Perinthos and Byzantion (Athenian allies) in order to secure a bridgehead to Asia. He may have believed that the Athenian Isokrates’s oration letter to him was indicative that Athens could be won over as an ally, in order to provide the ships he needed but didn’t have. He knew Demosthenes a problem, but may not have believed fear of/resentment against Philip himself would unite Thebes and Athens (inveterate enemies) to oppose him at Chaironeia.

But that’s how it went. Philip won anyway and created the Corinthian League, whose purpose was the invasion of Persia and vengeance for the earlier Persian invasion of Greece. Was that Philip’s primary motivation? Oh, hell no. He wanted the MONEY/loot (and glory). But a campaign of retribution put a better face on it, and justified his usurpation of the Athenian navy, which he absolutely had to have to be successful.

When Philip was assassinated, Alexander simply took up where his father left off. He literally told the Corinthian League (when he reconvened them not long after Philip’s death), “Only the name of the king has changed….”

So yes, the propaganda wasn’t invented by Alexander, or even by Philip, but they used it to very good effect, as it allowed them to demand allies (and BOATS). Alexander didn’t dissolve the alliance and release those troops until after Darius’s death. And even then, he offered good pay to stay on with the rest of his conquests (which many did).

#asks#philip ii of macedon#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#Greco-Persian Wars#Alexander's campaigns#Isokrates#Isocrates#ancient Athens#Greek revenge campaign against Persia#Classics

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The length of a marathon was originally defined as "about 40 kilometers, give or take," depending on who was administering it. That's the rough distance between the cities of Athens and Marathon in Greece which it was named after. In the early 20th century they tried to standardize it as either exactly 40 kilometers (24.85485 miles) or exactly 25 miles (40.2336 kilometers), either of which would have been perfectly sensible, but the 1908 London Olympics defined it as exactly 26 miles and 386 yards (26.21875 miles, 42.19499 kilometers) because that was the distance from the starting line at Windsor Castle to the finish line halfway up the track inside White City Stadium, but only if you entered the stadium from a specific doorway, otherwise it would have been longer. That's completely arbitrary, but it's the definition which has stuck to this day.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

If there is life after the Earth-life, will you come with me? Even then?

If we're meant to be something, why not together.

Dianthus of Oenoe (also called Dia or very rarely Dianthe) is my main sona / self insert / etc. She's basically me but if i was in Hade game's setting <3 more info below!

( Art credits: Laurel (TH) / 2nd drawing is by me )

She's physically in her 20s and about 5'4. Her father was a human merchant from somewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, and her mother was Chloris, a nymph-goddess from Etruria. Due to being half nymph Dianthus has some powers over plantlife herself, but they're very weak and mostly useless. Her hair and body will sometimes sprout flowers or even fruit, but it tends to happen randomly, and like any flower they eventually wilt overtime!

She met Theseus while still alive, and aided him in his battle against the Bull of Marathon. Afterwards Theseus returned to Athens, but he intended to return to Dia's home so that he may have her hand in marriage. Unfortunately, however, Theseus was soon sent off to Crete to deal with another bull problem overseas, and Dia had to leave her home to avoid an arranged marriage. After this and up until her death, she became a Maenad, a member of the retinue of Dionysus, and thru him became associated with the Eleusisian mysteries. When she died, her body was transformed into a carnation.

Later, in Elysium, she reunited with King Theseus, and helped him again, this time in the task of bringing Asterius to Elysium!

Within the blessed fields, she works as a librarian.

She's a rather sweet girl for the most part, and tries her best to be kind to others. However... she can also be a bit arrogant and self centered as well. She's very stubborn and headstrong when she needs to be, but also won't hesitate to give up on a task if it proves to be too much- she's very concerned for her own rest and relaxation, after all. When it comes to Theseus and Asterius, she often has to remind them to take breaks as well!

Silly funfacts:

~ She writes gay fanfiction of heroes even more ancient than those of greece. ask her about her gilgamesh/enkidu yaoi collection (don't actually ask her she'll get embarassed)

~ within a plaza of elysium, there's a board within the plaza where shades can come by and pin things they've written. one user of this board is only known as "championsgirl01" and writes some very passionate posts... most of them in defense of the king himself.

~ Her favourite flower is actually the sunflower, but she also loves pink roses and carnations, her namesake.

~ She collects merch of the champions, and is the vice president of their fanclub. She also watches every match! ...In reality, though, she really doesn't care that much about the sportmanship thing. She just likes watching sweaty buff guys battling it out.

~ Friends with Patroclus, Achilles, Dusa, and surprisingly, Alecto. Has a weird frenemies thing with Zagreus. Co-workers with Hypnos but he's always asking what Asterius is up to which makes her look at him with daggers in her eyes </3

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

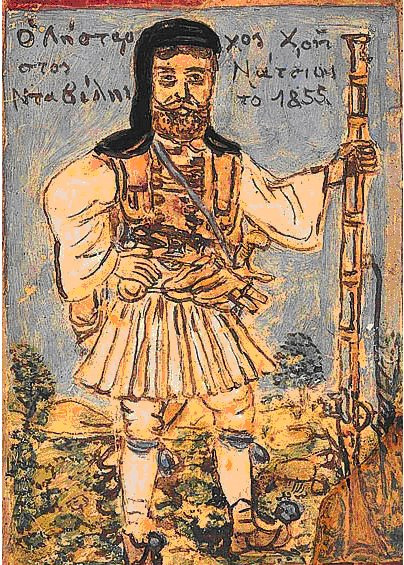

Christos Davelis

The Brigand Captain

Christos Davelis, who is mostly known as Λήσταρχος Νταβέλης (Lístarchos Davélis, Brigand Captain Davelis) in Greece, was a notorious bandit who was active in the regions of Attica and Boeotia in the mids of the 19th century. Although he died young, his life reminds of fictional literature, so much that he became a folk hero of sorts in the collective Greek memory, despite not really possessing heroic virtues.

His real name was Christos Natsios. His birthplace is not certain but it is believed he had some Arvanite-Vlach descent. Christos was initially a shepherd, just like most of his family. He took care of the flocks of a monastery in Mt Penteli. Someday, the abbot approached him and asked him to deliver a letter to a nun in Athens in full secrecy. Overcome with curiosity, Christos gave the letter to someone who could read it for him instead, as he was illiterate. Learning of the letter's contents, he decided to meet that nun himself and he became a frequent visitor of hers. The abbot found out and accused him of robbery. Christos was whipped and exiled to Euboea island.

There he fell in love with the daughter of a priest (he did appreciate the religious vibe apparently), although she was already betrothed to a prosperous shepherd. The shepherd seeked revenge and led Christos Natsios to the authorities claiming he was a deserter they were after, called Nastos. Christos failed to convince them his surname was different. He managed to flee though and he escaped to the mountains, under the alias Davelis.

There he joined the bandit gang of his uncle and soon he created his own, with which he was robbing travellers, shepherds and farmers who lived in Attica, Boeotia, Phthiotis and Euboea. One of his most notorious operations was the kidnapping of the French officer Berteau, who had come to Greece in order to convince the Greek government to not participate in the Crimean War by Russia's side (and against the Ottomans). This operation proved to be his most prolific as the Greek state paid him 30,000 drachmas in gold (an outrageous amount of money back then) to let the French man free.

His reputation grew bigger in 1855 when his gang was active near Marathon and Davelis used the Cave of Penteli as his lair. This cave is still said to have a haunting vibe about it and it is sometimes associated with stories of supernatural incidents.

The Cave of Davelis.

The most famous and decisive point in his life though was his affair with the Italian duchess Luisa Bacoli, who asked the gang's protection in order to visit Delphi safely. Davelis' right hand, Yannis Megas, fell in love with her and went mad when Bacoli responded to Davelis' advances instead. He left the gang, denounced his former lifestyle and joined the police, determined to hunt Davelis down.

This was not even the only duchess seduced by Davelis charms' who was said to have a soft and delicate face, despite his reputation and lifestyle. According to folklore, he also had an affair with the Duchess of Plaisance, Sophie de Marbois-Lebru and there was a tunnel connecting his cave all the way to her villa in Athens.

Sophie de Marbois-Lebrun, Duchess of Plaisance

Another legend was that Davelis often disguised himself and casually visited Athens, where he conversed in coffee shops with the locals.

Folk art of Davelis.

The police was humiliated often by Davelis , once being surprised by his gang in Menidi and being forced to hand him their weapons. This made the police (and Megas) even more determined to catch him. This finally happened in the summer of 1856, in a proper combat between Davelis' gang and the policemen. Seeing many of his men fall, Davelis offered to fight Megas in a one-to-one duel. Megas leaped furiously at him with a sword but Davelis managed to kill him first, using a gun. His victory didn't last. A policeman killed him with his sword, while Davelis was crying "ούτε ο Νταβέλης στα βουνά ούτε ο Μέγας στα παλάτια" (úte o Davélis sta vuná úte o Méghas sta palátia = "neither Davelis in the mountains nor Megas in the palaces"). His head was put on a stick and left in common view in Syntagma Square in Athens for several days, in the summer of 1856. The head is now kept in the Museum of Criminology in Athens but the access to it is restricted.

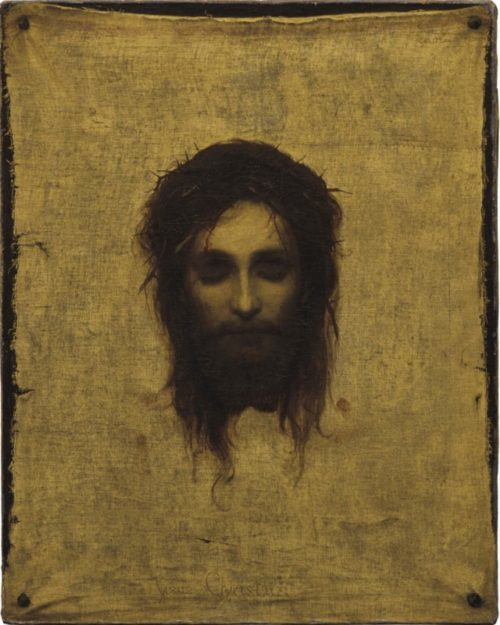

The Greek painter Nikephoros Lytras, just passing by, took a photograph of his head, and later took it to Munich where he would be working for a while. While there, he became friends with the German painter Gabriel Cornelius Von Max.

One day when the German artist was in Lytras’s studio rummaging through his files, he came across the portrait of Davelis’ head. He asked Lytras about the identity of his model: “He was the most terrible thief that Greece has ever known, a ruthless, ferocious man” – “And yet,” Von Max countered, “in this picture, I can see that this man met God at the moment of his death. You have the portrait there of a saint; a great saint.”

Lytras thought that Von Max was obviously deranged. “Since he interests you so much, the portrait is my gift to you.” Von Max took away the portrait and used it to paint his most famous work: ‘The Veil of Veronica’; reproduced millions of times.

Sources: x, x

#greece#history#christos davelis#listarchos davelis#greek history#folk history#long text#tw long text#sterea hellas#central greece#athens#attica#euboea#boeotia#cave of davelis

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

If Kassandra didn't have access to any of her superpowers, how do you think she would fare against Lara Croft in a one-on-one fight? What about Nadine from Uncharted or Abby from the Last of Us? My opinion changes depending on if normal weapons like guns or bows are allowed. If no weapons are allowed, I honestly think Abby would win, but no one else would. If normal weapons are allowed, it gets more complicated. I would be interested to hear what you think.

ooh, great question! And one that's difficult to answer—as you pointed out, it really depends on the situation.

My glib answer is that as a writer, I could show any of these characters defeating any other in a realistic way that you'd believe. That's my superpower.

So without going back to you and asking for more specifics, the best I can do is walk you through my thought process for writing a believable action scene between two characters.

(Lots of talk about writing action scenes after the jump!)

The first thing I think about is the situation and setting: Where are they fighting? When are they fighting? What universe are they in? Are they in our reality as we know it, or the mostly-realistic-with-a-dash-of-fantasy worlds of AC: Odyssey or the Tomb Raider reboot trilogy, or somewhere else entirely?

The situation and setting are crucial. Kassandra and Lara fighting in a traditional dojo would be much different than having them fight in a pine forest, or the war-torn Athens of AC:O, or a mining base on Mars. As Kassandra says to Kyra in The Breaking: "I'm surrounded by weapons." The setting determines what unconventional weapons might be at hand, if any, what cover is available, what bystanders or dangers might need to be accounted for.

Once I've established the setting of the scene, I start thinking about weapons in more detail. Do the combatants have formal training? What kinds of weapons and how much actual combat usage? How does the universe they're in treat weapons? As much as I love AC:O, that game puts all types of melee weapons on equal footing regardless of reach (length). It works within that universe because the game is consistent about its combat, but in the real world a dagger is no match for a polearm and that's fact.

Weapons tilt the table. Think of the moment in the Tomb Raider reboot where Lara gets that first gun. Her opponents could have 20 years of martial arts training and outweigh her by 50kg, but that doesn't matter a whit against a ranged firearm. The gun is the equalizer.

Setting matters. Weapons matter. Only when those parameters are sorted do I consider the physical abilities and hand-to-hand combat experience of the respective fighters. There are so many what-ifs to consider, and making everything fit together makes for a good logic puzzle. (And I haven't even gotten into the characterization aspects of writing action: not everyone has a killer instinct, and that matters!)

But let's go back to your original question and simplify things by thinking of the most basic scenario for unarmed combat: a bout taking place in the real world, in a neutral location like a dojo.

Even without superpowers, Kassandra is an impressive physical specimen. She has the strength to overpower opponents and the advantage of reach. She'd have a disadvantage in endurance, however, since all that muscle mass she's carrying is going to need energy to move it. (A good example of "strength vs endurance" affecting muscle mass can be seen in sprinters vs marathon runners.)

We'd also have to establish which Kassandra is fighting: young Kassandra (as we meet her in Kephallonia) or Kassandra at the top of her game, winner of the Olympic pankration and honed by at least five years of fighting damn near every mercenary and soldier of renown in ancient Greece.

To defeat her in unarmed combat in the real world, an opponent would have to:

outmatch her in physical ability and have just enough hand-to-hand combat experience to use it to their advantage, or

equal her in physical ability and hand-to-hand combat experience, or

have so much more experience that they could overcome all of her other advantages

That's a tough ask, and I don't really see Lara, Nadine, or Abby having enough hand-to-hand combat experience to pull it off, even against a young, less experienced Kassandra. I think Abby would come the closest, and if she went off and studied a bunch of hand-to-hand styles intensively for several years she'd make it an even fight.

So, to recap: it's definitely possible to contrive situations where one of them could defeat a non-superpowered Kassandra. I'd choose a setting and weapons that would support the challenger's strengths, and adjust Kassandra's experience accordingly.

Setting matters. Weapons matter. Experience matters.

#tldr: it depends#apologies for this novel-length non-answer 😅#i'm glad you asked#my grey faced friend#thanks for the thought-provoking question#i had a lot of fun with this one#special thanks also to#tazrider#for helping with some factual details#kassandra#ac odyssey

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

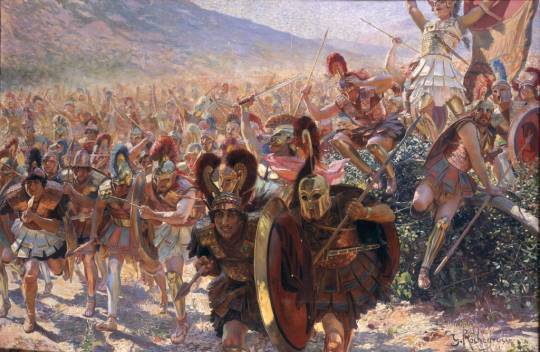

Les Héros de Marathon (The Heroes of Marathon) by Georges Rochegrosse

Greek troops rushing forward at the Battle of Marathon 490 BC

#battle of marathon#athens#plataea#art#georges rochegrosse#history#athenians#achaemenid empire#persian#invasion#antiquity#ancient greece#greece#ancient greek#ancient#greek#europe#european#heroes#troops#soldiers#battle#war#marathon#art nouveau

179 notes

·

View notes

Photo

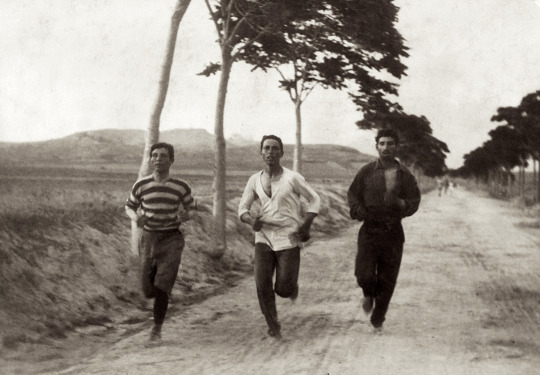

First Olympic Marathon, Athens, Greece (1896)

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

oh yea I get that , sorry 😅 I am just excitable,, like a dog lmao.. It was not my intention to overstep. you do not have to share anything you don't want to.!

i am going to politely ignore that question cause it makes me ✨ nervous ✨ to answer, but I will take the bite marks thank you 🖤

also I am very very short.. realistically you would not be looking up at me,, but height doesn't matter much when i or my partner is on their knees,,

you have done such an amazing job( ◜‿◝ )🖤 such a good princess.. (hand kiss) here is your reward.. :)

fact #1: marathons are the length they are because in ancient Greece, a messenger died after running about 25 miles between marathon and Athens, and basically is just a dunk on him cause he died from running that much and people who run marathons do not. (it changed to 26.2 miles to accommodate to royal family in England but that's a *bonus* fact)

fact #2: Dolly Parton uses her nails as an instrument, and in a lot of her older music, she has credits for playing her nails.

-🍃

No worries, nothing was overstepped 😊

Is it the question that is making you nervous or is it me darling? Hmm? ☺️

I’m actually pretty tall, I’m 5’6 or 1.67 meters. Plus I’m even taller when I’m wearing my platforms. But completely agree with you, submissiveness is a state of mind more than anything else ☺️

Hand kisses are my weakness! They make me feel like royalty 🥺 thank you, I am a good princess ✨

Hehehe I already knew that! But I didn’t knew about the bonus fact so it still a win for you.

And she’s such an icon, I love her 🥹

Thank you my little angel of knowledge 🖤🖤

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“BMCR 2020.08.24

Herodotus. Histories. Book V

P. J. Rhodes, Herodotus. Histories. Book V. Aris & Phillips classical texts. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2019. ix, 263 p.. ISBN 9781789620153 £22.99 (pb).

Review by

Charles Chiasson, The University of Texas at Arlington. [email protected]

Professor Rhodes’ edition of Book 5 is the first book of Herodotus’ Histories to appear in the Aris and Phillips series, which aims to accommodate readers with rudimentary knowledge of ancient Greek. (Rhodes plans a companion edition of Book 6 to carry the narrative of Greco-Persian conflict through the battle of Marathon in 490 BCE.) The choice of this book is a good fit for the editor’s primarily historical interests, as it includes Herodotus’ accounts of the Ionian Revolt; the end of the Peisistratid tyranny and the beginning of more democratic rule in Athens; and Spartan attempts to expand its political influence in Greece beyond the Peloponnese. The book also contains some of Herodotus’ most memorable literary creations—characters, scenes, and speeches introduced to underscore important historical moments, such as Aristagoras’ brazen attempt to secure military aid from the Spartan king Cleomenes, and the Corinthian Socles’ pivotal speech opposing the Spartan re-establishment of tyrannical rule in Athens.

This edition includes an introduction with bibliography, a Greek text with facing English translation, and a commentary of approximately 100 pages.

The introduction is suitably substantial and covers essential background to orient the novice, although even Herodotean veterans will find points of interest along the way. Rhodes lucidly covers the evidence for Herodotus’ life, the ‘publication’ of the Histories (likely to have involved public recitals before full written publication in the mid-420’s), and Herodotus’ use of (primarily oral) sources. In judging the reliability of Herodotus’ hotly debated source citations, Rhodes advocates a middle course between extreme skepticism and extreme credulity, in the belief that Herodotus probably “wrote what he honestly thought he remembered” (11), although his memory may have failed him occasionally. Rhodes makes an explicit exception of the Persian Constitutional Debate, which he considers (despite repeated Herodotean claims to the contrary) a product of 5th-century Greece rather than 6th-century Persia.

In discussing Herodotus’ language, narrative techniques, and beliefs, Rhodes rightly acknowledges the importance of Homeric precedent: his epics serve as a model for Herodotus’ long narrative, set in multiple locales and enlivened by frequent speeches and occasional epic locutions. Moreover, Rhodes finds further justification for Pseudo-Longinus’ description of Herodotus as “most Homeric” at a deeper thematic level. He endorses John Gould’s view that Herodotus’ focus on the vulnerability of human existence and prosperity, his “sympathetic engagement with human suffering” (18),[1] has distinctly Homeric roots.

Other topics addressed by Rhodes include Herodotus’ political beliefs and the extent to which the Histories acknowledge or allude to political developments in the Greek world that took place after the end of the narrative in 479. Rhodes shares the now popular view that Herodotus is neither pro-Athenian nor pro-Spartan, and in broad terms prefers free constitutional government over one-man rule (whether Oriental monarchy or Greek tyranny). As for the relationship between Herodotus’ narrative of the past and contemporary Hellenic politics (especially the polarization between imperial Athens and Sparta, with their respective allies), Rhodes defends the conservative view that Herodotus’ primary objective is the one he announces explicitly in his opening sentence—i.e., to write about great deeds of the past in Homeric fashion.

Rhodes devotes the second section of his introduction (pp. 34-43) to the history of contact and conflict between the Greeks and Persians, from the Hellenic migrations to the Aegean islands and Asian coast during the Dark Age through the invasion of Xerxes and its aftermath. The introduction concludes with an outline summary of Book 5, which helps the reader navigate the complexities of the text, with its frequent changes of place and time, and demonstrates (inter alia) Herodotus’ enthusiastic embrace of analepsis: almost half of the book consists of flashbacks into Spartan and Athenian history (chaps. 39-97), which help explain the divergent reactions of the two communities when Aristagoras comes calling in search of military aid against the Persians.

The depth and breadth of erudition that Rhodes brings to bear upon the text can be gleaned from his lists of references at pp. vii-ix (collections of inscriptions, other prose and poetic texts, and journals in various languages) and pp. 45-48 (a select bibliography of Herodotean texts, commentaries, translations, and reference works). One work that Rhodes cites often throughout his commentary is R. J. A. Talbert’s Barrington Atlas,[2] which helps to compensate for the minimal cartographic resources available in this volume: three black-and-white maps (a page each for Magna Graecia, Greece and the Aegean, and the Near East) that precede the introduction.

Rhodes describes the Greek text that he prints as his own in “all the substantial matters which seemed to call for a decision” (Preface p. v), while following N. G. Wilson’s 2015 Oxford Text with regard to the spelling of Herodotus’ eastern Ionic dialect. In terms of general editorial practice, Rhodes parts company with Wilson in his greater willingness to defend rather than emend the transmitted text. The text (like others in the Aris and Phillips series) has a minimal apparatus criticus; in his commentary Rhodes often discusses and justifies his choices, persuasively to my mind. True to his conservative textual creed, Rhodes introduces only a single conjecture of his own into the text (at 66.1).

In the Preface (p. v) Rhodes declares that the primary task of his translation is “to express the meaning accurately in good English,” which has resulted in his changing Herodotus’ sentence structure on occasion. To give readers some small sense of the result, here in Rhodes’ rendition is the opening of the speech given by the Corinthian Socles to the Spartans and their allies at 5.92:

”Indeed heaven will be below the earth and earth up in the air above the heaven, and mankind will have a life in the sea and fish the life which mankind previously had, when you, Spartans, are prepared to overthrow equalities of power and restore tyrannies to the cities, something than which nothing is more unjust among mankind or more bloodthirsty.”

For comparative purposes, here is the same passage as translated by Robin Waterfield:[3]

“Whatever next?” he said. “Will the heavens be under the earth and the earth up in the sky on top of the heavens? Will men habitually live in the sea and fish live where men did before? It’s a topsy-turvy world if you Lacedaimonians are really planning to abolish equal rights and restore tyrants to their states, when there is nothing known to man that is more unjust or bloodthirsty than tyranny.”

However brief the sample, the juxtaposition underscores both strengths and weaknesses of Rhodes’ approach. On the one hand, and despite his stated concern about infidelity to Herodotus’ text, Rhodes in this instance (and as a general rule) reproduces the sentence structure of the original almost without deviation. The result is unquestionably accurate if occasionally awkward (“something than which…”). By contrast, Waterfield’s translation is freer and livelier, turning a long single declaration into a series of indignant questions that are truer to the spirit than the letter of Herodotus’ text. Rhodes’ more conservative approach is appropriate, however, given the purpose and the audience of this edition.

In his commentary (as in his introduction) Rhodes claims to have been “particularly but not exclusively concerned with the subject-matter: the history which Herodotus narrates, and how and why he narrates it as he does” (Preface, pp. v-vi). Of course the “history” that Herodotus narrates is famously wide-ranging, which requires that an editor be well versed in a wide variety of fields: not just history in the modern sense but also “deep” history (legend or myth), ethnography, geography, prosopography, epigraphy, and religion, among others. In short, Professor Rhodes has a masterful command of this wide spectrum of knowledge, and a gift for expressing it clearly and concisely. Rhodes serves the needs of readers new to Herodotus in various ways. For example, he consistently notes how Herodotus organizes his narrative by means of ring composition and analepsis. His descriptions of the nuts and bolts of the Athenian and Spartan governmental systems are clear without being reductive. He intervenes as necessary to explain potentially mystifying aspects of Greek religious practice, like the status of the local gods Damia and Auxesia, whose theft explains the origins of the hostility between Athens and Aegina (chaps. 82-86); or the hero cult established for the decapitated Cyprian rebel Onesilaus after a swarm of bees builds a honeycomb in his head (chap. 114).

At the same time, seasoned Herodoteans will appreciate his even-handed citation and assessment of previous scholarship, including frequent references (some approving, some dissenting) to Simon Hornblower’s recent edition of book five in the Cambridge ‘green and yellow’ series.[4] A sample passage where Rhodes must entangle all manner of scholarly problems is the post-tyranny transition in Athens to Cleisthenes’ rule (chaps. 66-81), where his discussion is informed by a wide range of primary witnesses (Thucydides, Plutarch, and the Aristotelian Constitution of the Athenians for starters) and secondary scholarship from the likes of Sarah Forsdyke, Ernst Badian, and Josiah Ober. Rhodes wears his learning lightly, and seldom lets his scholarship impede intelligibility.

On occasion Rhodes’ historical focus prevents him from acknowledging points of broader narratological and literary interest. I have in mind especially one of my favorite scenes in book five, Aristagoras’ visit to Sparta and King Cleomenes in search of allies in the Ionian Revolt against Darius. In this scene (5.49-51) Herodotus gives his readers yet another reason to dislike Aristagoras: he attempts (unsuccessfully) to pass himself off as an enquirer, like Herodotus, armed with geographical and ethnographical knowledge to inform a crucial political decision. He brandishes a map (recalling Herodotus’ own cartographic interests), describes the various foreign peoples en route to Sousa in much the same way that Herodotus describes non-Greek populations, and even adapts Herodotus’ signature superlative phrase in describing the Phrygians as “the richest in flocks of all whom I know, and in crops” (49.5). And yet Aristagoras repeatedly exaggerates the ease of conquering all of Asia, and ultimately defeats his own purpose by telling Cleomenes that the trip from Sardis to Sousa would last three months. As Herodotus wryly observes, Aristagoras “slipped” in this regard: “for he ought not to have told the truth, if he wanted to lead the Spartiates to Asia” (50.2). Rhodes declines to comment, when he might have called attention to both Herodotus’ humor and the crucial difference thus drawn between Aristagoras’ misleading historiē and its truth-based Herodotean counterpart.[5]

Nonetheless, this scarcely diminishes Rhodes’ impressive achievement throughout. This edition marks an auspicious beginning for Herodotus in the Aris and Phillips series; it provides a lucid and learned introduction to an author whose boundless curiosity requires informed explication by a “wise advisor” indeed, and Professor Rhodes unquestionably fills the bill. It is difficult for me to imagine, on this scale, a more informative historical commentary on book five.

Notes

[1] J. Gould, Herodotus (New York, 1989) 132.

[2] R. J. A. Talbert, ed., Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World (Princeton 2000).

[3] R. Waterfield, Herodotus The Histories, with introduction and notes by C. Dewald (Oxford, 1998).

[4] S. Hornblower, ed., Herodotus Histories Book V (Cambridge 2013).

[5] D. Branscome, Textual Rivals: Self-Presentation in Herodotus’ Histories (Ann Arbor, 2013) 105-49.

Source: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2020/2020.08.24/

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay but wait, you went to Athens?! I’m going there for a couple days this June! Do you have any recommendations for what to see/eat while I’m there? (I’ll for sure see the Acropolis but other than that the itinerary is pretty open)

OOOOH that’s so exciting!!! I’m gonna try not to go overboard but here are a few of my favorite things:

• Monastiraki Square—depending on how you come at it, of course, it’s on the way to the Acropolis, and there’s a VERY cool open air market there. (There’s a giant sign, you can’t miss it.) Just make sure you keep a hand on your purse, it’s quite well-known for pickpocketing. Also, if you head up to the Acropolis from there, you’ll pass Hadrian’s Library, which is a really cool set of ruins where you can clearly see the different layers of where it was built over over time. But you won’t really be hard-pressed to find ruins in Athens, and the entry fees are usually pretty cheap—just make sure you always have some form of ID on you, sometimes they’ll ask for that.

• Also, if you take that way up to the Acropolis, you’ll pass Mars Hill (also called the Areopagus), which is where Paul preached to the Athenians in Acts! It’s a bit graffitied over (but that’s just kind of how Athens is), but it’s still REALLY cool, and you get a gorgeous view of the city from up there. Just be careful up there, it’s pretty much just a big rock and I almost fell many times 😂

• Bus tours are also fun if you want to see a broader swath of the city—there are a bunch that leave from Syntagma Square (and they’re double-decker!).

• Speaking of Syntagma, you could see the changing of the guards—they do it every hour, but the only time they do it in full-costume is at 11 am on Sundays. It was interesting, but honestly I think you could skip it, it’s not much to write home about.

• However, what you should NOT skip is the National Gardens—it’s fairly close to Syntagma, entry is free if I’m remembering correctly, and it’s absolutely gorgeous. They have turtles!!!!

• You could go to the Panathenaic Stadium, although they do charge entry. I would say just to go look at it if you really want to see it, but I don’t know that’s it’s worth paying to go inside—I did go inside once, but that was during the Marathon in November when everyone got in free, lol.

• In terms of food, in a strange twist, the Americanized version of Greek food is actually a lot lighter than the authentic kind—true Greek food (or at least in this area of Greece) is a lot heavier. It’s a lot of pasta and meat. I wasn’t actually the biggest fan of it, but if you want to try the staples, go for moussaka or souvlaki, which will be at almost any restaurant. What you definitely need to get though is tzatziki—oh my GOSH that stuff is wonderful.

• Also, you have to try lemon Coke and oregano Lay’s—I’m convinced that when the Ancient Greeks were imagining what ambrosia and nectar tasted like, they were dreaming of the flavors of lemon Coke and oregano Lay’s. I’ve found that no American variation (even with Freestyle machines) even compares to Greek lemon Coke.

• I found that gyros actually aren’t all that popular (or at least in this part of Greece)—I only ever had two in my four months of living there. They were really good, though.

• The coffee is great everywhere, honestly. One of the most popular drinks there is freddo, which is definitely worth trying if you’re big on espresso drinks. It is very intense, though.

• Dinner was honestly one of my biggest culture shocks while I was there. They don’t really start eating dinner until 7 at the earliest (and even that’s a little early)—so be prepared to get odd looks if you go get dinner at 5:30 (not that you can’t, of course). Also, it’s general practice to sit around and talk after your meal for hours—I saw families out with their little kids at 11 pm. Again, you don’t have to do this, but don’t be surprised when you see it, lol. Also, because of this, they consider it rude to interrupt you by bringing you your bill, so you have to ask for it by flagging down a waiter—I once got stuck for nearly an hour because I was waiting for a bill 😂.

• If you’re there on a Sunday, be warned that most stores and restaurants will be closed—there are exceptions, but it’s easy to get stuck somewhere without anything to eat.

I’m so excited for you, I hope you have fun!!

3 notes

·

View notes