#marie de medici

Text

↳ Historical Ladies Name: Mary/Marie/Maria

#mary of woodstock#mary of waltham#mary of guelders#mary of burgundy#mary tudor#mary of guise#mary i of england#mary queen of scots#marie de medici#mary princess royal#mary of modena#maria theresa of spain#mary ii of england#maria theresa#marie antoinette#mary of teck#my gifs#creations*#historicalnames*#historyedit#efoor

447 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Musketeers, ep.1x6

#the musketeers#musketeersedit#perioddramaedit#bbc musketeers#cardinal richelieu#marie de medici#aramis#captain treville#themusketeersedit#santiago cabrera#peter capaldi#hugo speer#ryan gage#king louis xiii#agnes#musketeers#the musketeers bbc#bbc the musketeers

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Virgin of the Rose – Simone Cantarini // Wedding of Marie de Medici and Henry IV of France – Jacopo da Empoli (detail) // St Catherine of Alexandria – Pietro Paolini // King - Florence + the Machine

#madonna and child#marie de medici#st catherine of alexandria#king#dance fever#florence + the machine#florence and the machine#fatm#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art#charlotte survives february

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frans Pourbus (Flemish, 1569–1622)

Portrait of King Louis XIII of France, 1611

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Pourbus inscribed the sitter’s age and the painting’s year in the composition: “The holy year 1611 at his age of 10 years.” Marie de’ Medici commissioned this work as she negotiated marriages for her two children to Philip III of Spain and Mary Marguerite of Austria, alliances that led to the European domination of the next two centuries by the Bourbon and Habsburg families.

#spanish netherlands#frans pourbus#flemish#flemish art#flanders#1500s#1600s#portait of king louis xiii of france#1611#pourbus#medici#de' medici#de medici#marie de medici#marie de' medici#philip iii of spain#mary marguerite of austria#bourbon#habsburg#art#fine art#european art#classical art#male portrait#europe#king#european#oil painting#fine arts#mediterranean

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640) • The Disembarkation of Versailles, also known as The Arrival of Marie de Medici at Marseille • Between 1622 and 1625

The Arrival of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles shows the Queen of France arriving by ship in Marseille on November 3, 1600. She is greeted by unknown characters that represent France, as they are seen with the French royalty symbol, the Fleur-de-lis. At the bottom of the painting, Neptune and the daughters of Nereus, the Sea God, are seen saluting the Queen. At the top of the painting, the character Fame is flying overhead, trumpeting the Queen’s arrival. Rubens uses these symbolic figures to transform a historical event into an allegory that reinforces Marie de' Medici's right to the throne. The various French symbols depicted greeting Marie upon her arrival are meant to establish good will and respect between her and the French people. - Wikipedia

The main reason why Marie de' Medici was never liked by the French population was because she was Italian, not French.

On a diplomatic visit to France (yes, he was a diplomat) Rubens encountered Marie de' Medici who commissioned a series of 21 paintings related to events that happened during her life, while 3 others are portraits of herself and her parents. They were intended to decorate Luxembourg Palace in Paris.

Detail of the mythological figures below the boat / Wiki Commons

The entire idea of the cycle was to glorify Marie de' Medici, and especially to try and convey to the people of France that she was a rightful ruler. Rubens therefore, according to art history speculation, depicted a warm welcome by members of the court of Henry IV. In reality, the welcome was rather lukewarm, if not chilly.

The Rubens cycle of paintings obviously didn't accomplish their intended purpose. Medici was forced out of her position as Regent of France in 1617 as the result of a coup and exiled, eventually residing in Cologne. In an interesting twist of fate, Marie de Medici died in the same house that Rubens grew up in.

Installation view of the cycle of paintings at the Louvre. They were moved there from Luxembourg Palace in 1793, when the Louvre first opened its doors.

Sources: Wikipedia, arthistoryreference.com, lelouvre.fr, artible.com, wga.hu

#art#painting#allegorical painting#peter paul rubens#fine art#art history#flemish painter#flemish baroque#baroque art#historical painting#marie de medici#medici cycle of paintings#musée du louvre#luxembourg palace#art nude#mythological painting#rubens#museum aesthetic#art lover#art blogging#art blog#french history#17th century european art#marseille

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

What were Marie de medici’s failings as a regent from your perspective as I recall reading recently this really weird take which tried to argue she was a great one but from what I have read from you and personal research she wasn’t? Sorry for the long paragraph just would love to hear your thoughts!!!

marie is such a complex character to analyze, not gonna lie. From a strictly objective point of view, if you look at her regency and only the timeframe of her regency, she did relatively well mostly because the kingdom had reached a specific point from the time Henri IV was still alive. Her best interest was to secure as much of Henri's policies, inside and outside, as possible and she did for the most part. Her regency is fundamentally different from that of Catherine de Medici because Henri IV was in his fifties and had reigned for over twenty years; there was a blueprint in place that felt somewhat cohesive and she followed it, which i'll admit is no small feat considering the amount of pressure a queen mother faces when she becomes regent for a minor.

now when all is said and done i don't necessarily agree when people complain that Marie is just completely vilified because people don't understand her (it's more or less the entire premise of the thesis written by JF Debost from a couple years ago). His work gives me 'separate the artist from the art' vibes. She was a decent enough regent, which, alright, fair, but she was an abusive and obsessive mother, and utterly unable to put the greater good above her own ambitions. Dubost says in his book that her biggest mistake was to lose against Richelieu because ultimately it made him out to be the good guy and her the bad guy, but i disagree, like it's okay you can just admit they were both just as bad and move on. She was a victim as a wife but not as a queen mother; she victimized herself a lot, which is very different, pitted her sons against each other, and at the same time harassed and morally abused her daughter-in-law who was just a teenager when she married into the family.

in terms of failings, when talking about royalty i think it's a beginner's mistake to think you can dissociate private and public life. Royals weren't on the job, they were, period. Marie's shortcomings as a queen mother impacted the diplomatic and political landscape. The Spanish marriages were a choice, the English marriage was A Choice, the Estates General were a mess and led the top nobility to gain more power and confidence which provoked a constant clash with Richelieu and eventually derailed into the Fronde rebellion about two decades later. we can argue that it wasn't strictly her fault, and probably more Richelieu's, but it's worth mentioning, just like Louis XV's failings with the Parliament is worth mentioning when talking about the 1789 Revolution. The Concinis were also a huge, huge mistake that could have ended even worse than it did.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 17, 1605.

Mamma, I want so much to see you and ray little brother of Orleans, and if you do not come soon, I shall get my white riding coat and my stockings and boots, and I shall get on my little horse and go patata, patata. Mamma, I shall start to-morrow, early in the morning, for fear of the flies. Mamma, they tell me you have something pretty for me, and I want so much to see it. Do come, dear mamma. It is such fine weather, and you will find me so good. Meantime I am, mamma, your very humble and very obedient son.

DAUPHIN.

Letter from Louis XIII to his mother Marie de Medici when he was 4 years old. Unfortunately his mother never replied to his adorable letters. Louis one day asked wistfully why his mother never wrote.

“Papa tells me,” he said, “ that she makes ever so many smudges, but if she wrote to me, even if there were smudges, I should take care of the letter.”

Sauce:

#louis xiii#the patata patata got me right in my heart#children are so innocent#then the world comes and ruins everything#I've never wanted to hug a child from centuries ago so badly#marie de medici#henry iv

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The additional ingredient to this scenario was that the Guise possessed certain notable features that most other grandee families did not, their princely and trans- regional status. Their rank permitted access to the monarch that was unparalleled in most other court families, as ladies-in-waiting and holders of the highest court offices, but also merely as princely companions. They had strong links of blood and affinity with foreign powers, primarily in Italy, but also in Spain and the Empire.Guise women shared both these princely and trans- regional qualities with their male counterparts, and they came to the fore in a female- run court such as those of Marie de Medici and Anne of Austria. During periods of female rule normal lines of power and patronage thatradiate from a king to his most prominent male courtiers shift to a pattern of female alliances, as is seen notably in the reign of Elizabeth I of England. But these periods of female rule had their differences in seventeenth-century France. Katherine Crawford puts forward in her work on regencies that Marie de Medici overstepped her bounds as a female regent by presenting herself publicly as sharing royal authority with her son the King, whereas Anne of Austria always ensured that the public face of Bourbon authority was her son’s, never her own. By focusing on one of these matriarchs, the Dowager Duchess of Guise, Henriette-Catherine de Joyeuse, and her relationship with her son, Henri II, Duke of Guise, we can shed light on their conflicting interests between the dynastic and the personal, and in particular, in his personal ‘rêve italien’ versus the reputation of the family as a whole, in France and abroad, amongst the wider European society of princes."

Source: "Mother Knows Best: The Dowager Duchess of Guise, a Son’s Ambitions, and the Regencies of Marie de Medici and Anne of Austria" by Jonathan Spangler

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#marie de medici#marie de medicis#17th century#french history#women in history#women of history#anne of austria#historical#historical figures#queen#historical women#1600s#Bourbon#medici#historyedit#histoire#Graphic#history's women#baroque#marie of medici

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis XIII and his mother

While contemporaries thought that Louis inherited his father's "spirit" and intellect, his mother may have had a greater influence on the dauphin's political outlook. Henry sensed a central component of this: the striking resemblance of Louis's stubbornness and displays of temper to the emotional makeup of Marie. He even predicted that they would clash some day. This mother-son connection has been generally overlooked by historians, who have seen Marie de' Medici as a mother in name only, lacking in affection toward her firstborn. Scholars often dismiss Marie's role in Louis's early formation with the erroneous statement that she never kissed him, or did so irregularly.

The fact is, the queen did embrace the heir with regularity, if not exuberance, during his initial years. She also showed care for him in her letters, although these always had a practical bent in contrast to Henry's letters to the royal children's governess, which expressed a sense of joy in the children's very existence. Marie's letters remind one of the adult Louis's correctly concerned letters of condolence to subjects and his properly paternalistic communications with his sisters, surviving brother, and other close relatives.

The queen meticulously held out gifts as rewards for good behavior, while advocating inexorable punishment for "stubbornness." Still, she wrote to the dauphin's governess about the need to avoid whippings during the summer heat if possible, because the temperamental child "could get agitated"; and any beating should be administered "with such caution that the anger he might feel would not cause any illness." After 1609, when Louis's governess was replaced by a governor, the marquis de Souvré, Marie wrote to her son: "I am at ease in knowing that you are well and to learn that you are very well behaved, and that you are studying and doing your exercises. Keep it up and obey what M. de Souvré tells you so he will be able to confirm me always in that good opinion."

Marie's letters to her other children, notably the girls, confirm our impressions of the sort of indoctrination she was giving her firstborn. To Henriette, Louis's youngest sister, she wrote that nothing was more pleasing than her "little exercises." To the middle girl, Christine or Chrétienne, came an admonishment to be compliant like the oldest sister, Elisabeth. The mother's displeasure with the news of Christine's illness, we read with some astonishment, "would be greater if I didn't think of the example of your older sister who has been so well-behaved and obedient in doing what the doctors ordered for her. .. . So that is what I want from you and urge you to do if you wish to be always well loved by Your very good mother Marie."

Louis continued to look for maternal affection, despite Marie's cool demeanor. He was drawn to her also by an acquired filial deference, something that he could never fully shake later on in life, even when breaking with her spectacularly as a teenage king and again as an adult. His early childhood rages and pouting against her were no different from those he displayed so often toward his father, nurse, governess, and physician. Indeed, he could be so excited at the prospect of seeing his mother that he would help make her bed, be impatient if she did not come when expected, and race to kiss her when she finally arrived.

In addition to filial obedience and spontaneous hope, Louis was bonded to his mother by their peculiar positions in the royal family. Although she was clearly queen, and he just as surely dauphin, there was always competition for both of them from the same source —Henry's love affairs. Henry had a habit of acquiring longtime liaisons, in addition to indulging in casual sexual encounters. Furthermore, he somehow always managed to get his current lady friend pregnant in tandem with his wife's regular pregnancies. And he insisted that his legitimate and natural offspring live together at St-Germain under the common care of Louis's governess! This was mortifying enough for Marie, who alternated between fighting with her husband and accepting his affection and concern for her well-being, but it was downright confusing and unnerving for a proud, young heir.

A. Lloyd Moote- Louis XIII the Just

#xvii#a. lloyd moote#louis xiii the just#louis xiii#marie de medici#henri iv#élisabeth de france#christine de france#henriette de france#parents and children#i like it when marie's relationships are shown with more nuance

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie de Médicis by Charles and Henri Beaubrun.

#royaume de france#marie de médici#marie de medici#marie de' Medici#reine de france#vive la reine#regent of france#coronation robes#maison de bourbon#italian aristocracy#casa de' medici#charles beaubrun#henri beaubrun#beaubrun

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

↳ family trees + House of Medici (14th - 16th century)

#this has been in my drafts for one year#I wanted to change the font but now cbf#house de medici#lorenzo de medici#giuliano de medici#marie de medici#catherine de medici#henry iv of france#henry ii of france#clarice orsini#contessina de bardi#lucrezia tornabuoni#historyedit#familytrees*#my gifs#creations*

635 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie de Medici, Queen of France and Navarre, child, 1600-1610(?)

Unknown author, Florence school

#dianthus#carnation#portrait#marie de medici#17th century painting#17th century art#women portrait#italian art

1 note

·

View note

Text

Novels Alive | GUEST BLOG: Henrietta Maria of France by Elena Maria Vidal

0 notes

Text

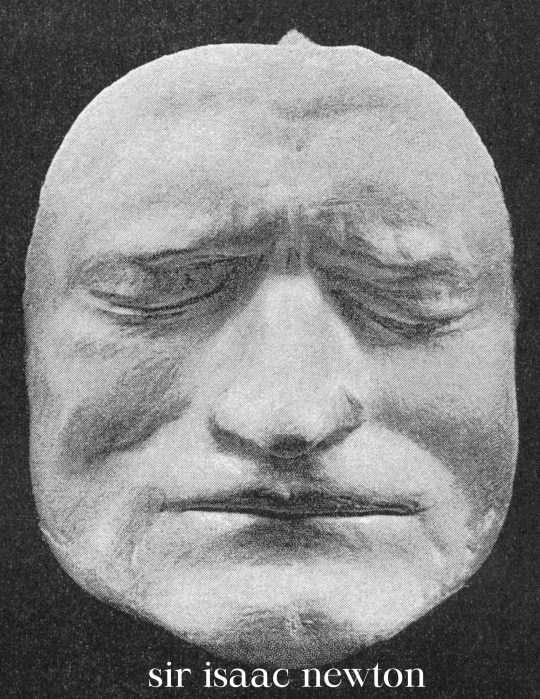

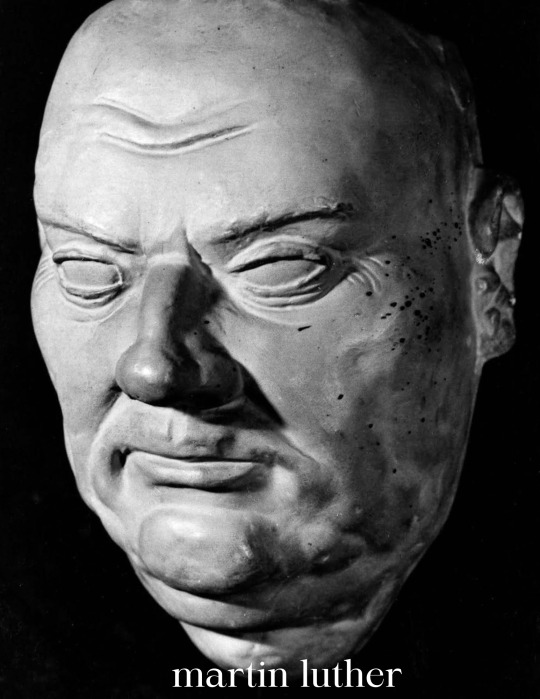

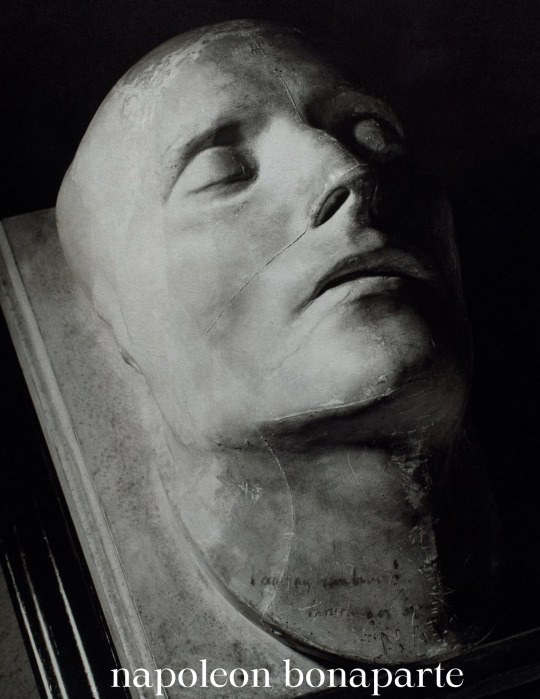

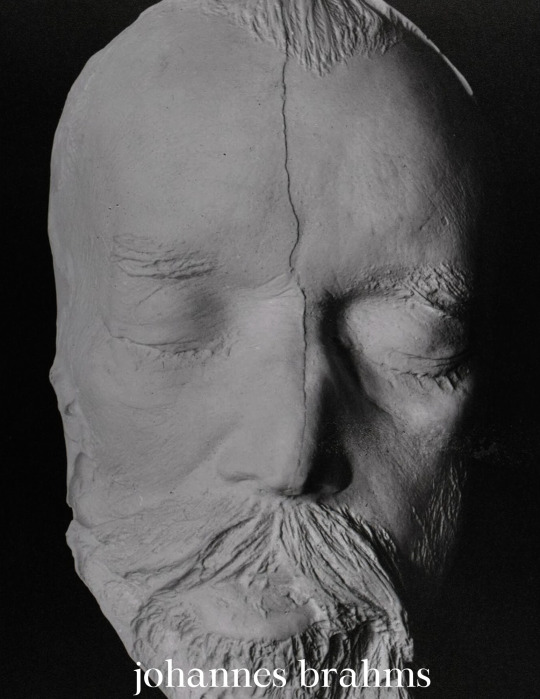

"A death mask is a likeness of a person's face after their death, usually made by taking a cast or impression from the corpse. Death masks may be mementos of the dead or be used for creation of portraits.

The main purpose of the death mask from the Middle Ages until the 19th century was to serve as a model for sculptors in creating statues and busts of the deceased person. Not until the 1800s did such masks become valued for themselves.

In other cultures a death mask may be a funeral mask, an image placed on the face of the deceased before burial rites, and normally buried with them. The best known of these are the masks used in ancient Egypt as part of the mummification process, such as the mask of Tutankhamun, and those from Mycenaean Greece such as the Mask of Agamemnon."

#death masks#history#sir isaac newton#oliver cromwell#martin luther#ludwig van beethoven#napoleon bonaparte#johannes brahms#mary queen of scots#lorenzo de medici#art history

623 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Reign" Pulling Strings (TV Episode 2017)

#reignedit#reign#perioddramaedit#periodedit#mary stuart#catherine de medici#mary x catherine#gifs#s4#by liz#weloveperioddrama#perioddramasource

231 notes

·

View notes