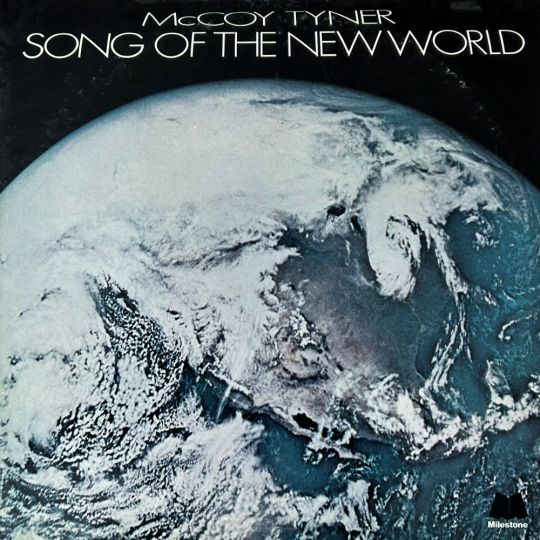

#mccoy tyner

Text

John Coltrane Quartet

Soprano Saxophone - John Coltrane

Drum - Elvin Jones

Bass - Jimmy Garrison

Piano - Mccoy Tyner

source: theguardian

📸: Jim Marshall Photography LLC

#photography#artist photography#John Coltrane Quartet#John Coltrane#Mccoy Tyner#Jimmy Garrison#Elvin Jones

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

McCoy Tyner at the first session for Stanley Turrentine’s Return of the Prodigal Son, June 1967 (photo: Francis Wolff/© Mosaic Images LLC)

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

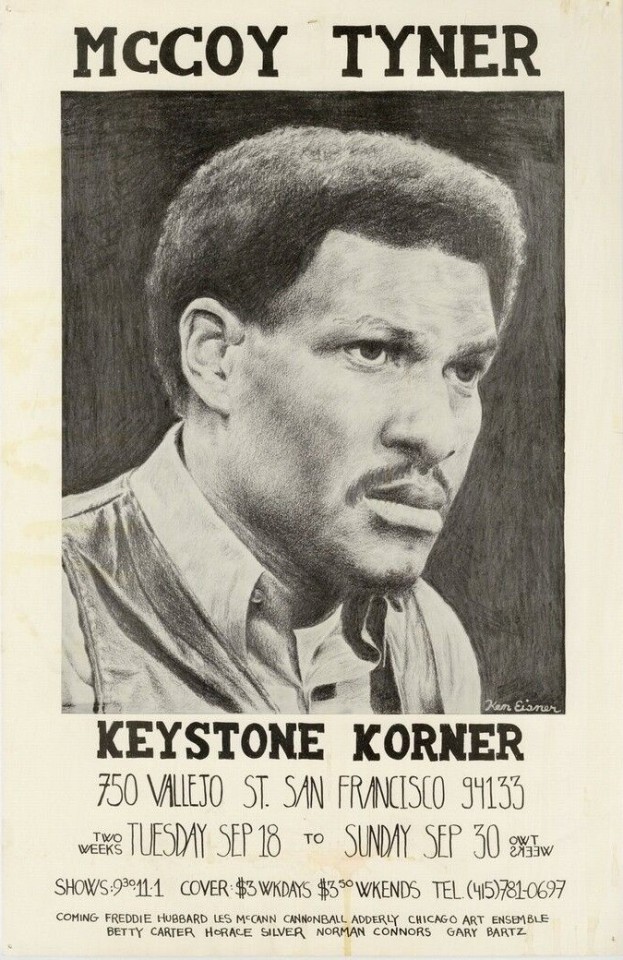

1973 - McCoy Tyner - Keystone Corner - San Francisco

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

John Coltrane Quartet with Eric Dolphy -

"Impressions"

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jimmy Garrison: The Bassist Behind the Legendary John Coltrane Quartet

Introduction:

Jimmy Garrison was an American jazz double bassist best known for his work with the legendary John Coltrane Quartet. Born ninety years ago today on March 3, 1934, in Miami, Florida, Garrison developed a unique and influential style that helped redefine the role of the bass in modern jazz. This blog post explores Garrison’s life, music, and enduring legacy.

Early Life and Musical…

View On WordPress

#A Love Supreme#Elvin Jones#Henry Grimes#Impressions#Jazz Bassists#Jazz History#Jimmy Garrison#John Coltrane#John Coltrane Quartet#Lee Morgan#Live at the Village Vanguard#McCoy Tyner#Reggie Workman

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

John Coltrane Quartet

“Lonnie's Lament"

McCoy Tyner-Great Piano Solo 2:00

Jimmy Garrison-Extended Bass Solo 6:15

Elvin Jones-Drums

#john coltrane quartet#mccoy tyner#jimmy garrison#elvin jones#john coltrane#what I'm I'm listening to#Youtube

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#top 7 albums#weekly#tristeza#the pharcyde#streetlight manifesto#slayer#the gerogerigegege#neil young#mccoy tyner

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John Coltrane – Olé Coltrane.

1961 : Atlantic.

#jazz#hard bop#modal jazz#john coltrane#1961#atlantic#reggie workman#mccoy tyner#elvin jones#1960s#1960s jazz

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening Post: John Coltrane/Eric Dolphy’s Evenings at the Village Gate

In 1961, John Coltrane was reaching a wider audience via his edited single version of the Sound of Music classic "My Favorite Things.” He was also, although it seems trite to say given the trajectory of his career, in a state of transition. Moving away from his "sheets of sound" period to exploring modality, non-western scales and polyrhythms which allowed him to improvise more deeply within the constraints of more familiar Jazz tropes.

His personal and musical relationship with Eric Dolphy was an important catalyst for the development of his sound. Dolphy was an important presence on Coltrane's other key album from 1961, Africa/Brass and here officially joins the quartet on alto, bass clarinet and flute. Evenings at the Village Gate was recorded towards the end of a month-long residency with a core band of Coltrane, Dolphy, Jones, McCoy Tyner on piano and Reggie Workman on bass. The other musician featured here, on "Africa,” is bassist Art Davis.

The recording captures the band moving towards the more incandescent sound that made Live at the Village Vanguard, recorded just a few weeks later in November 1961, such a viscerally thrilling album. The hit "My Favorite Things" and traditional English folk tune "Greensleeves" are extended into long trance-like vamps. Benny Carter's 1936 classic "When Lights Are Low" showcases Dolphy's bass clarinet and in the originals "Impressions" and particularly "Africa" the quintet hit almost ecstatic grooves. Dolphy's solos push Coltrane further into the spiritual free jazz that so divided later audiences. Dolphy's flute on "My Favorite Things" and especially his clarinet on "When Lights Are Low" are extraordinary, particularly the clarity of his upper register.

The highlight for me is the 22 minute version of "Africa" that closes the set. The two basses, bowed and plucked, Tyner's chordal work and solo, the slow build from the bass solo where the music seems to meander before Jones' explosive solo heralds the return of Dolphy and Coltrane improvising together on the theme, spiralling up the register, contrasting Coltrane's long slurries with Dolphy's staccato bursts which lead to the thunderous conclusion.

As an archivist, sudden discoveries in forgotten basement boxes never surprises and the excitement never gets old. The tapes of Evenings at the Village Gate were recently unearthed in the NY Public Library sound archive after having been lost, found and lost again. Recorded by the Village Gate's sound engineer Rich Alderson these tapes were not meant for commercial use but rather to test the room's sound and a new ribbon microphone. As Alderson says in his notes, this was the only time he made a live recording with a single mic and, yes, there have been grumblings from fans and critics about the sound quality and mix particularly the dominance of Elvin Jones' drums. For me, one the best things about this is that you hear how integral Jones is not just as a fulcrum for the other soloists but as an inventive polyrhythmic presence, playing within and around his bandmates. I know that many of the Dusted crew are Coltrane fans and would love to hear your takes on the music and whether the single mic recording affects your enjoyment in any way.

Andrew Forell

youtube

Justin Cober-Lake: There's so much to get into here, but I'll respond to your most direct question. The single-mic recording doesn't affect my enjoyment at all. I understand (sort of) the complaints, but I think they overstate the problem. More to the point, when I hear an archival release, I really want to get something new out of it. That doesn't mean I want a bad recording, but there's not too much point in digging up yet-another-nearly-the-same show (and I have nearly unlimited patience for Coltrane releases) or outtakes that give the cuts the same basic idea but just don't do it as well. I was really looking forward to hearing Coltrane and Dolphy interact, and nothing here disappoints. Having Jones so dominant just means I get to hear and think more about the role he plays in this combo. It would sound better to have the other instruments a little more to the fore, but it's not a problem (and actually Tyner's the one I wish I could hear a little better).

I think your topic suggests ideas about what these sorts of recordings — when made publicly available — are for. Is it academic material (the way we might look at a writer's journals or correspondence)? Is it to get truly new and good music out there? Is it a commercial ploy? Is it a time capsule to get us in the moment? The best curating does at least three of those with the commercial aspect a hoped-for benefit. This one probably hits all four, but I suspect the recording pushes it a little more toward that first category.

Bill Meyer: I’m playing this for the first time as I type, and I’m only to track three, so my (ahem) impressions could not be fresher.

First, I’ll say that, like Justin, I have a lot of time for Coltrane, and especially the quartet/quintet music from the Impulse years. The band’s on point, it sounds like Dolphy is sparking Coltrane, and Jones is firing up the whole band. Tyner’s low in the mix and Workman’s more felt than heard; the recording probably reflects what it was like to actually hear this band most nights, i.e. Jones and the horn(s) were overwhelming.

How essential is it? If you’re a deep student of Coltrane, there are no inessential records, and the chance to hear him with Dolphy, fairly early on, should not be passed up. But if you’re big fan, not a scholar, then you need to get The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings box and the 7-CD set, Live Trane: The European Tours, before you drop a penny on this album. And if you’re just curious, start with Impressions. This group is hardly under-documented. The sound quality, while tolerable, is compromised enough to make Evenings At The Village Gate less essential than everything I just mentioned.

I’m only just now starting to play “Africa,” so I’ll check in again after I play that.

“Africa” might be the best reason for a merely curious listener to get this album. It’s very exploratory, the bass conversation is almost casual (not a phrase I use much when discussing Coltrane), and they manage to tap into the piece’s inherent grandeur by the end.

“Africa” is a great example of this band working out what they’re doing while they’re doing it.

Andrew Forell: On Justin’s points about the function of archival releases, I’ve been going back and forth on the academic versus time capsule/good music uncovered question. There is a degree of cynicism and skepticism in these days of multidisc, anniversary box sets in arrays of tastefully colored vinyl which seemed designed for the super(liquid)fan and cater to a mix of nostalgia and fetish. Having said that specialist archival labels have done us a great service unearthing so much "lost" and under-represented music. On one hand I agree with your summation and to Bill’s point, yes this quintet has been pretty thoroughly documented and yes the Vanguard tapes would be the place to start. But purely as a fan I am more interested in live recordings than discs of out- and alternative takes. I’m thinking for example of the 1957 Monk/Coltrane at Carnegie Hall and Dolphy’s 1963 Illinois concert especially his solo rendition of “God Bless the Child," recordings that sat in archives for 48 and 36 years respectively.

youtube

By contrast, the other recent Coltrane excavation, Both Directions at Once is wonderful but I’m not listening to it as an academic exercise, taking notes and mulling over the different takes, interesting as they are. I approach Evenings as another opportunity to hear two great musicians, in a live setting, early on in their short partnership. As Justin says, this aspect doesn’t disappoint. I agree with Bill that the mix is close to what you would you hear in the room, the drums and horns to the fore. All this is a long way to a short answer. A moment in time, a band we’ll never experience in person and when all is said and done, 80 minutes of music I’d otherwise not hear.

Jonathan Shaw: As a relative newb to this music, I can't contribute cogently to discussions of this set's relative value. Most of the Coltrane I've listened to closely is from very late in his life, when he was playing wild and free--big fan of the set from Temple University in 1966 and the Live at the Village Vanguard Again! record from the same year. None of that is music I understand, but I feel it and respond to it strongly. The only Dolphy I've listened to closely is Out There. So I'll be the naif here.

I need to listen to these songs another few times before I can say anything about them as songs, but I really love the right-there-ness of the sound. I like being pushed around by the drums and squeezed between the horns (the first few minutes of "Greensleeves" are delightful in that respect). Maybe I'm lucky to come to the music with so little context. It's a thrill to hear the playing of these folks, about whom there is so much talk of collective genius. Perhaps because my ears are so raw to these sounds, I feel like that talk is being fleshed out for me.

Jim Marks: I think that this release has both academic and aesthetic (if that’s the right word) significance for Dolphy’s presence alone. I am more familiar with the original releases than the various re-releases from the period, but it’s my impression that there just isn’t that much Dolphy and Trane out there; for instance, I think Dolphy appears on just one cut of the Village Vanguard recordings (again, at least the original release). In particular, I’ve heard and loved various versions of “Favorite Things,” but this one seems unique for the six-plus-minute flute solo that opens the track. The solo is both brilliant in itself and creates a thrilling contrast with Coltrane when he comes in. This track alone is worth the price of admission for me.

Marc Medwin: I agree concerning Dolphy's importance to these performances, and while there is indeed plenty of Coltrane and Dolphy floating around (he took part in the Africa/Brass sessions that gave us both Africa and a big band version of "Greensleeves") his playing is really edgy here. Bill is right to point toward the sparks Dolphy's playing showers on the music. Yes, the flute on "My Favorite Things" is really stunning. He's all over the instrument, even more so than in those solos I've heard from the group's time in Europe.

Jon, I'd suggest that there's a strong link between the albums you mention and the Village Gate recordings we're discussing, a kind of continuum into which you're tapping when you describe the excitement generated by the playing. The musicians were as excited at the time as we are on hearing it all now! It was all new territory, the descriptors were in the process of forming, and while Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra and a small group of kindred spirits were already exploring the spaceways, they were marginalized. That may be a component of the case today, but it's tempered by a veneration unimaginable at the time. That's part of the reason Dolphy lived in apartments where the snow came through the walls. Coltrane had plenty to lose by alienating the critics, but ultimately, it did not stop his progress. These recordings mark an early stage of that halting but inexorable voyage. With the possible exception of OM, Coltrane's final work never abandoned the tonal and modal extremes at which he was grabbing in the spring and summer of 1961.

Jennifer Kelly: Like Jon, I'm not well enough versed in this stuff to put it context or even really offer an opinion. I'm enjoying it a lot, and I, also, like the roughness and liveness of the mix with the foregrounded drums. But I think mostly what I am drawn to is the idea that this show happened in 1961, the year I was born, and that these sounds were lost for decades, and now you can hear them again, not just the music but the room tone, the people applauding, the shuffling of feet etc. from people who are almost all probably dead now. It seems incredibly moving, and I am also taken by the part that the library took in this, in conserving this stuff and forgetting it had it and then rediscovering it. In this age of online everything-available-all-the-time, that seems remarkable to me, and proves that libraries are so crucial to civilization now and always, even as they're under threat.

Marc Medwin: A real time machine, isn't it? We are fortunate that we have these documents at all, and yes, the story of the tapes resurfacing is a compelling one! To your observations, audience reaction seems pretty enthusiastic to music that would eventually be dubbed anti-jazz by prominent members of the critical establishment!

Bill Meyer: I can imagine this music being more sympathetically received by audiences experiencing its intensity, whereas critics might have fretted because it represented a paradigm shift away from bebop models, so they had to decide if it was jazz or not.

It is amusing, given the knowledge we have of what Coltrane would be playing in five years, that this music is where a lot of critics drew a line in the sane and said, "this is antijazz."

Jon Shaw: Yes, Bill, that seems bonkers to me. I am particularly moved by the minutes in that 1966 set at Temple when Coltrane abandons his horn altogether and starts beating his chest and humming and grunting. Wonder what the chin-stroking jazz authorities made of that.

Given my points of reference, this set sounds so much more musically conventional. But the emotional force of the music is still immediate, viscerally present. Beautifully so.

youtube

Andrew Forell: In retrospect, all those arguments seem kind of crazy. Yesterday’s heresies become tomorrow’s orthodoxies but what we’re left with is, as Jonathan says, the visceral beauty of Coltrane’s striving for transcendence and his interplay with Dolphy’s extraordinary talent which we hear here working as a catalyst for Coltrane. As Marc and Jen note the audience is there with them..

Come Shepp, Sanders & Rashid Ali, the inquisitors’ fulminations only increased and you think what weren’t you hearing?

Marc Medwin: I was just listening to a Jaimie Branch interview where she's talking about her visual art, about throwing down a lot of material and finding the forms within it. I think that might be another throughline in Coltrane's and certainly Dolphy's work, a gradual discarding of traditional forms and poossibly structures based on what I hate to call intuition, because it diminishes the process.

Then, I was thinking again about our discussion of the critics. I see their role, or their assessment of that role, as a kind of investment without reward, and yeah, it does seem bonkers now! Bill Dixon once talked about how the writers might spend considerable time and expend commensurate energy learning to pick out "I Got Rhythm" on the piano, and they're suddenly confronted with... well, the sounds we're discussing! What would you do, or have done, in that situation? It's really easy for me, like shooting fish in the proverbial barrel, to

disparage critical efforts of the time, especially in light of the ideas and philosophies Branch and so many others are at liberty and encouraged to play and express now, but I wonder how I would have

reacted, what my biases and predilections would have involved at that pivotal moment.

Ian Mathers: The points about historical reception are really interesting, I think. There's a famous (in Canada!) bunch of Canadian painters called the Group of Seven, hugely influential on Canadian art in the 20th century and still well known today. In all the major museums, reproductions everywhere, etc. They were largely landscape painters, and while I think most of the work is beautiful, it's so culturally prominent that it runs the risk of seeming boring or staid. I literally grew up with it being around! So it was a delightful shock to read a group biography of them (Ross King's Defiant Spirits: The Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven, if anyone is hankering for some CanCon) and see from contemporary reviews that people were so shocked and appalled by the vividness of their colour palettes and other aesthetic choices that they were practically called anti-art at the time. It's not surprising to me that this music would both attract similar furore at the time and, from the vantage point of a new listener in 2022 who loves A Love Supreme and some of the other obvious works but hasn't delved particularly far into Dolphy, Coltrane live, or this era in jazz in general (that would be me), be heard and felt as great, exciting, but not exactly formally radical stuff.

I don't think I would have noticed much about the recording quality were people not talking about it. "My Favorite Things" seems to have the overall volume down a bit, but still seemed pretty clear to me (agree with the assessments above; Coltrane, Dolphy, and Jones very forward, others further back although even when less prominent I find myself 'following' Tyner's work through these tracks more often than not), and starting with "When Lights Are Low" that seems to be corrected. It actually sounds pretty great to me! Although I absolutely defer to Bill's recommendations for better starting places for serious investigations, I can also say as a casual but interested fan who tends to quail in the face of box sets and other similarly lengthy efforts this feels from my relatively ignorant vantage like a perfectly nice place to start. I like Justin's rubric for why these releases might come about (or be valuable), but if I hadn't heard any Coltrane and you just gave me this one, my unnuanced perspective would just be something like "wow, this is great!" But maybe I'm underthinking it. And having that reaction doesn't mean that others aren't right to recommend better/more edifying entry points, or that having that reaction shouldn't lead one to educate oneself.

Jonathan Shaw: Maybe it's a lucky thing for me to be so poorly versed in Coltrane's music, not just in the sense of having listened to precious little of it. I am even less familiar with the catalog of music criticism, which in jazz seems to me voluminous, archival in scale. But even with music I'm extensively engaged with — historically, critically — I try to understand it and also to feel it. I can't imagine not feeling what's exciting in this music, energizing and challenging in equal measure.

Like Marc, I don't want to recursively impugn the critical writing of folks working in very different contexts. But I don't like it when the thinking gets in the way of the music's emotional and aesthetic force, which to me feels unmistakably powerful here.

Ian Mathers: Yeah, maybe that's a good distinction to draw; I can imagine in a different time and place feeling like the music here is more radical or challenging than it sounds to us now. But I can't quite imagine not getting a visceral thrill out of it.

Marc Medwin: And doesn't this contradiction get at the essence of what we're trying to do? Those of us who've chosen to write about music are absolutely stuck grasping at the ephemeral in whatever way we're able! How do we balance the ordering of considerations and explanations in unfolding sentences with the spontaneity of action and reaction that made us pick up a pen in the first place?! We add and subtract layers of whatever that alchemical intersection of meaning and energy involves that hits so hard and compels us to write! In fact, the more time I'm spending with these snapshots of summer 1961, the more I decamp from my own philosophizing about critical relativity to sit beside Ian. The stuff is powerful and original, and the fact that so much of what we're hearing now is a direct result of those modal explorations and harmonically inventive interventions says that the dissenting voices were fundamentally, if understandably, wrong! It could be that the musician can be inclusive in a way the writer simply can't.

I'm listening to "Africa" again, which is for me the disc's biggest single revelation in that it's the only concert version we have, so far as I know. How exciting is that Jones solo, and how much does it say about his art and the group's collective art?!! He starts out in this kind

of "Latin" groove with layers of swing and syncopation over it, he

goes into a melodic/motivic thing like you'd eventually hear Ginger

Baker doing on Toad, and then eases back into the groove, all (if no

editing has occured) in about two minutes. He's got the music's

history summed up in the time it would take somebody to get through a proper hello!! Took me longer to scribble about it than for him to play it!!

Justin Cober-Lake: I'm not sure if Marc is making me want to put down or pick up a pen, but he's definitely making me want to listen to "Africa" again. (Not that I needed much encouragement.)

Andrew Forell: Africa/Brass was the first jazz album I bought. Coming from post-punk, I found it immediately the most exciting and challenging music I’d heard and it set me off on my exploration of Coltrane, Dolphy, Coleman and their contemporaries. This version of “Africa” is a highlight for me also for all the reasons Marc, Ian and Jon have talked about.

Bill Meyer: Yeah, "Africa" is quite the jam!

A thought about critical perspective — our discussion has gotten me thinking, not for the first time, about the impacts of measures upon experience, and the limits of critical thinking when I’m also an avid listener. If I’m listening for “the best” Coltrane/Dolphy, in terms of sound quality or most focused performances, this album isn’t it. But if I’m looking for excitement, this album has loads of it, and that might be enhanced by the drums-forward mix.

#listening post#dusted magazine#john coltrane#eric dolphy evenings at the village gate#jazz#reissuemmc#mccoy tyner#reggie workman#derek taylor#art davis#new york public library#andrew forell#justin cober-lake#bill meyer#africa#jonathan shaw#jim marks#mark medwin#jennifer kelly#ian mathers#Youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

John Coltrane Quartet • My Favorite Things • Live in Comblain-La-Tour, Belgium, 1965

Soprano Saxophone - John Coltrane

Piano - Mccoy Tyner

Bass - Jimmy Garrison

Drum - Elvin Jones

#1960s#John Coltrane Quartet#John Coltrane#Mccoy Tyner#Jimmy Garrison#Elvin Jones#Jazz#Free Jazz#Live Jazz#Comblain-La-Tour#Belgium#1965#Youtube

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Coltrane Quartet - The Jazz Gallery, New York City, June 27, 1960

Since we just checked out a 1960 audience tape of Miles and Coltrane, let's hang out back there for a little while longer. Another audience tape! A pretty listenable one, all things considered. Thank a taper, for heaven's sake. By June, Coltrane had left the Miles Davis group for good and quickly set about forming his own unit. This isn't quite the classic quartet yet — McCoy Tyner is firmly in place on piano, but drummer Pete LaRoca is behind the kit instead of the soon-to-join Elvin Jones. And then there's the somewhat shadowy bassist Steve Davis, who would play on some of Coltrane's classic Atlantic LPs and then more or less vanish, only appearing on a handful of other sessions. Mysterious ...

Anyway! This Jazz Gallery performance is, as far as I know, our first glimpse of Coltrane live and on his own in the 1960s. He sounds ready to go, kicking things off with a long, wild "Liberia" before sliding smoothly into a gorgeous "Every Time We Say Goodbye." The band, especially Tyner, follows their new leader fearlessly. Interestingly, if the date of this tape is right, Coltrane would go into the studio the next day — but not with this band. Instead, he'd be playing with Ornette Coleman's group: Don Cherry, Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell. The results wouldn't be released until 1966.

Coltrane says: I’ve got to keep experimenting. I feel that I’m just beginning. I have part of what I’m looking for in my grasp but not all. I’m very happy devoting all my time to music, and I’m glad to be one of the many who are striving for fuller development as musicians. Considering the great heritage in music that we have, the work of giants of the past, the present, and the promise of those who are to come, I feel that we have every reason to face the future optimistically.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Coltrane Quartet - Comblain-La-Tour (Belgique) en 1965, avec McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison et Elvin Jones

#jazz#gif#john coltrane#mccoy tyner#jimmy garrison#elvin jones#jazz festival#1965#comblain jazz festival

75 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Passion Dance (McCoy Tyner) - Connie Han

A TRIBUTE TO MCCOY TYNER: An iconic recording and composition, “Passion Dance” captures the signature style of piano giant McCoy Tyner in his modern flow and uninhibited spirit. It is difficult to put into words the tremendous impact his album The Real McCoy (1967) with Joe Henderson, Elvin Jones, and Ron Carter has had on my music and soul as a jazz musician. Though known for his pioneering take-no-prisoners approach at the piano, McCoy was supremely musical above all and was equally versed in elegant lyricism as he was in hard-driving and innovative rhythm.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael Brecker: A Jazz Saxophonist Extraordinaire

Introduction:

Michael Brecker, a renowned jazz saxophonist, was born seventy-five years ago today on March 29, 1949, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His career spanned over three decades, during which he established himself as one of the most influential and innovative saxophonists in jazz history. Brecker’s musical journey was marked by his virtuosic playing, unique improvisational style, and…

View On WordPress

#Billy Cobham#George Benson#Herbie Hancock#Horace Silver#Jazz History#Jazz Saxophonists#Joni Mitchell#McCoy Tyner#Michael Brecker#Mrs. Seamon&039;s Sound Band#Pat Metheny#Randy Brecker#Randy Sandke#The Brecker Brothers

6 notes

·

View notes