#medieval christianity

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

There was no mass cat-culling in the Middle Ages. European Medieval folks, including clerics, pretty much loved the goobers.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently read the book of Margery Kempe for a class and I found myself reflected in her wayyyy too much. The idea of the female mystic in medieval Europe and just the concept of experiencing god through a feminine lens in a deeply patriarchal society is fascinating.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went to the Morgan Library yesterday, where one of the main galleries was an expedition called Medieval Money. With banger plaques like “Will Money Damn Your Soul?” And “Your Money or Your Life?”, it featured the ethical and theological debate at the time of early capitalism on the ethics of earning and keeping large amounts of money when the Bible clearly says not to do that. It had illuminated manuscripts with illustrations of parables condemning wealth contrasted with early money, scales and bishop pardons to the wealthy who donated to churches.

One, I really wish the majority of American Christians kept the same energy they have towards gay and trans people to the wealthy who are actually condemned in the Bible.

Two, I want to meet the smug curator who decided to create that exhibit out of J.P. Morgan’s private collection and feature it in his museum. Loved the irony.

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Gentle Giant - Three Friends (Official Audio)

Gentle Giant - Three Friends (Official Audio)

https://youtu.be/7W7Jgl3hn-I?si=zNXR1Q7ZNutEU6q2 via @YouTube

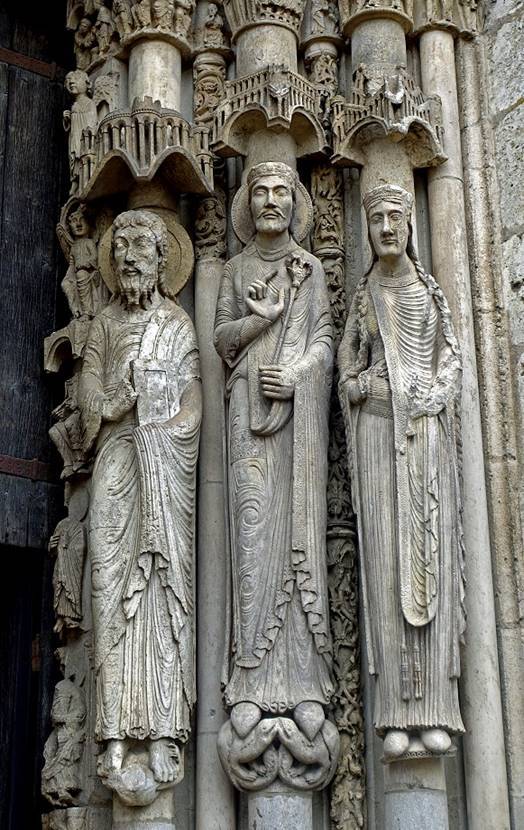

#youtube#Prog Rock#70s music#Christendom#Sacred Music#Medieval Christianity#Gothic Period#Cathedral Frieze

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I always took it for granted that things like Christmas trees were most likely Pagan in origin, so it's actually a little surprising to learn that they're most likely created by medieval Christians who were copying Paradise plays.

Also I didn't realize they were only around 500 years old, and didn't even really spread outside Germany until the 1600s.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning about Medieval Christianity in my play analysis class and how it used to be a lot more female-oriented (and erotic) than modern/post-reformation Christianity, and thinking about Andrastianism in Dragon Age and how it would’ve been so cool so see some of that reflected in the game and how we could have had that if the writers could conceive of a world where men and women are actually equal and isn’t saturated with misogyny.

#the myth of the Dark Ages is Renaissance propaganda#it was a lot less sexist than the majority of people think#women worked and could bring home half the income#they had control of their own reproduction (birth control)#they had influence in their homes and communities#medieval settings not being “realistic” without misogyny is bullshit#medieval christianity#history#dragon age#dragon age meta#andraste#andrastianism#the chantry#I think I’ll draw more medieval Christianity into my DA fanfics from now on#🧇

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“To understand the medieval situation, we must quickly sketch the broad outlines of how ecclesiastical discipline developed up to the eleventh century, which marked a decisive turning point in this area. From the origins of the church up to the beginning of the fourth century, no canon law—whether general or particular, in the East or the West—obliged married bishops or priests (and we know of many such clergy) to renounce sexual relations with their spouses. The only rule that seems to have existed regarding such matters was the injunction forbidding widowed clergy to remarry, in keeping with Paul’s comment that the person responsible for the Christian community—the episcopos, or overseer—must be “the husband of one wife” (1 Tim. 3:2).

After the end of the persecutions and the emergence of the church as a public institution, canonical legislation grew more substantial: priests and deacons were forbidden to marry after their ordination, and in the West married priests were called upon (by Pope Siricius, in particular, in 385–386) to abstain from conjugal relations with their spouse and live with her “like brother and sister.” At the end of the sixth century, Gregory the Great (who was pope from 590 to 604) even specified that a married priest should “love his wife like a sister, but distrust her like an enemy,” and so avoid cohabitation by maintaining separate bedrooms.

The Eastern churches, for their part, adopted on this point a different standard, ratified by a council held in Constantinople in 691, which they have maintained to this day: only the bishop is obliged to remain celibate; priests can marry so long as they do so before being ordained and can carry on normal marital relations. In both cases, the goal was the same: to see to it that the secular clergy—that is, the priests, bishops, and and other clergy engaged in pastoral care, whereas monks were known as the religious or regular clergy—stood out for its worthy manner of life and irreproachable conduct. But the Eastern churches thought that this could be attained within the framework of marriage, whereas the West held that a priest, whether married or not, could find safety only in sexual continence.

This choice must be seen in relation to the evolution of priestly duties, for it was then that priests began to celebrate the sacrifice of the Mass every day; they had to keep themselves pure in order to consecrate and handle the holy species of bread and wine. The fathers of the Latin church, St. Jerome and St. Augustine, had emphasized the impurity that results from sexual relations—omnis coitus immundus (all sexual relations are unclean), Jerome had written in his Against Jovinian (1.20)—and Pope Siricius voiced the same conviction in invoking Paul’s assertion that “those who are in the flesh cannot please God” (Rom. 8:8).

Since God is pure spirit, those who wish to approach him and claim to contemplate him must renounce their own bodies and abstain from all sexual relations. In this connection it is significant that clergy in minor orders—who, unlike those in major orders (priests, deacons, and subdeacons), did not take part in the consecration and distribution of the sacraments—were not subject to any limitations on their conjugal life. During the early Middle Ages, these prohibitions ran up against stiff resistance and even seemed to have been quickly forgotten.

Gregory of Tours (ca. 539–594) mentions numerous married bishops in Merovingian Gaul, whereas the church councils of that time frequently deplore the misconduct of unmarried clergy and the dubious company they kept. The church continued to ordain married men right down to the eleventh century, and the late-eighth-century collection of canon law known as the Dionysiana-Hadriana, which Charlemagne adopted to regulate clerical life and comportment in his empire, specified clearly that a married priest who returned to his wife was to be excommunicated. As late as 1010, the German bishop Burchard of Worms, in his Penitential, condemned those believers who scorned married priests and used this pretext to refuse to give them the offerings owed to the church.

This last viewpoint gives us a hint of the changes taking place in customs and outlook. Ever since the Carolingian epoch, in effect, the church had defined a favored path to salvation for each category of Christians in accordance with their place in the church and in society. In this perspective, marriage and family life had been proffered to laypeople as means of salvation at the same time that celibacy was presented to the clergy as the instrument of their sanctification. In addition, bishops tended to encourage single young men who undertook to remain continent to enter the priesthood, rather than ordaining married men.

Unfortunately, the surviving documents from this period are too few and too imprecise to allow us to trace this development in detail. Nevertheless, the statistics that the Italian historian Gabriella Rossetti has compiled from the parchments of the diocese of Lucca seem fairly convincing: between 774 and 885, sixty-six cases of legally married priests are mentioned in them, alongside fifteen concubinary priests; in the tenth century (890–1101), on the other hand, one finds in these records only seven legally married priests, as opposed to 106 with concubines.

The results of this study are confirmed by the admonitions addressed to his clergy by Atto of Vercelli (924–961), one of the rare reforming bishops of the tenth century, in which he called upon them above all to abstain from frequenting prostitutes. Thus the prospect of marriage seemed to be increasingly closed to Italian clergy, even if certain churches that were especially attached to their traditions, like that of Milan, still had substantial numbers of married priests in the middle of the eleventh century.

In the first decades of the eleventh century, the problem of the sexual lives of the clergy, which until then had barely merited a passing mention, became a burning issue and the object of numerous measures on the part of the highest church authorities. In less than a century, these measures brought about a complete reversal of the standards of clerical conduct that had prevailed until this point. In 1022, a Lombard church council, meeting in Pavia, decided that the children born to incontinent clergy would become slaves of the church that their father served and could not inherit their father’s goods; a similar measure was adopted at Bourges in 1031.

Above all, from the moment that the reforming impulse took root in Rome, with the pontificate of Leo IX (1048–1054), such measures—coupled with sanctions for those who contravened them—multiplied. In 1050, a Roman synod ordered priests to send away their wives and live henceforth in continence. In 1059, Nicholas II (who was pope from 1058 to 1061) forbade the faithful from attending Mass celebrated by priests who refused to leave their wives or concubines—a very significant decree, since (contradicting all previous canonical legislation on this point) it implied that the sacraments celebrated by those priests who did not live chastely were worthless.

Gregory VII pressed the issue further in 1074, declaring that all clergy who did not immediately abandon their female companions would ipso facto be deposed from their priestly office; he urgently called on all bishops throughout Christendom to apply these new regulations in their dioceses without delay and in their full rigor. Very few dared to do so, and those rare prelates who made the attempt, such as the archbishop Jean of Rouen or the Bavarian bishop Altmann of Passau, were nearly stoned by their subordinates. In parallel to these canonical decrees, the most ardent advocates of reform waged a campaign of polemics.

In his Liber Gomorrhianus (Book of Gomorrah), Peter Damian (1007– 1072) denounced in the harshest terms the loose conduct of the clergy and lashed out especially at their female companions, whom he condemned as “seducers of clergy, lures of the devil, scum of heaven, poison of souls,” and so on. It is noteworthy that in this literature, the legitimate wives of priests are no longer distinguished from concubines; rather, all are lumped together as “prostitutes.” From this moment on, in effect, the Roman Church rejected any form of clerical marriage and tacitly refused to acknowledge that a marriage entered into by a priest had any validity.

The culmination of this development was signaled by canons 6 and 7 of the Second Lateran Council (1139), which declared that any priest who cohabited with a woman (other than his mother, aunt, or sister, or a female servant who had reached the “canonical age” of sixty) would be deprived of his office and his ecclesiastical benefice, and above all that any marriage contracted by secular or regular clergy who held the rank of subdeacon or higher was not only illicit but invalid. The Roman Catholic Church has upheld this standard ever since, and to this day ordination remains (to use the terminology of the canon lawyers) a diriment impediment to marriage.

Even if a cleric and his companion could find a priest who was willing to marry them, the resulting union would be null and void. We should reflect on the reasons for this storm that broke so brusquely over the priesthood. Why did the problem of clerical incontinence—the famous “Nicolaite heresy”—acquire such importance that it ended by becoming, along with the struggle against simony, one of the principal concerns of the reform movement in the Western church? Could it be because clerical immorality had reached a truly unbearable level at that moment? That has long been the position held by traditional scholarship, which takes at face value the accusations hurled by the most extreme of the Gregorian reformers in their polemical works.

But despite their assertions, we have no particular reason to think that the situation had changed significantly, for better or for worse, with respect to the preceding centuries. On the contrary, it seems more exact to say that what had changed was the way people viewed behavior that until then had been commonly accepted: in certain sectors of the church—sectors that were not limited to the ecclesiastical hierarchy—the idea that persons dedicated to the ministry of the altar might engage in sexual activities had become an intolerable scandal. As often happens, the causes of this hardening of attitudes were complex.

The first (and perhaps, at the outset, the most fundamental) was interest in preventing the hereditary transmission of clerical offices and the ecclesiastical benefices attached to them. In this period, it often happened “that the rectory was full of children who, when they were old enough, helped their father at the altar while waiting to serve there themselves.” This process, which was becoming commonplace at the beginning of the eleventh century, carried a mortal peril for the church, since the creation of priestly dynasties claiming for themselves ecclesiastical functions and goods might lead in the end to a complete dissolution of the church’s patrimony, already threatened by the encroachment of lay lords.

It is thus significant that the first disciplinary measures taken to combat this slippage struck above all at priests’ children and wives. The former were declared illegitimate, even when they were the product of a legal marriage, and barred from inheriting their father’s goods, entering the priesthood (unless they obtained a dispensation), and contracting a legitimate marriage. Everything suggests that the aim in thus punishing the sons for the sins of their fathers was to discourage certain behavior on the part of the clergy. The latter were treated no better, since they could be reduced to bondage by the local lord or bishop.

Thus the former companions of Roman priests were appropriated as servants at the pontifical palace of the Lateran; elsewhere, they were thrown out on the street and fell into prostitution. A certain number of them can be found in the popular religious movements of the early twelfth century, such as the one that gathered in about 1100 in western France around Robert d’Arbrissel—himself the son and grandson of priests who had broken with his familial setting and thrown himself into the struggle for reform. It would, however, be incorrect to explain the church’s change in attitude simply in terms of social and economic interests, however important their role may have been.

We must also take into account the growing hostility of the papacy toward the patriarch of Constantinople, which reached the point of formal schism in 1054. One of the fiercest opponents of any form of clerical marriage was the monk Humbert de Moyenmoutier, from Lorraine in northeastern France; when he became a cardinal of the Roman Church, he did not hesitate to accuse the Greek Orthodox Church of having fallen into the Nicolaite heresy because it allowed the ordination of married men and did not require that they be continent. His personal role in the struggle for clerical celibacy, like that of his contemporary and colleague Peter Damian, brings out clearly the importance of monastic influence.

The program of monastic reform, promoted and exemplified by Cluny and by the Italian hermit-monks, made virginity a central concern and called all those entering the cloistered life to imitate the angels. In an age in which the prestige of the secular clergy was at its nadir and that of the monks at its zenith, it was inevitable that the monastic ideal would come to affect expectations of priests. In fact, at the same time that he issued the repressive measures already mentioned, Gregory VII called on the clergy—starting with the canons and those associated with collegial and cathedral churches—to live in common according to the model provided by the group of texts known as the Rule of St. Augustine.

By holding all their goods in common, they would avoid any private appropriation of ecclesiastical property; by observing the discipline of eating in a common refectory and sleeping in a common dormitory, they would prevent any cohabitation with women and enable themselves to live chastely. This program did not receive an enthusiastic welcome from those for whom it was intended. Certain individuals or groups of clergy who were more fervent than the rest rallied to it and founded communities and even orders of regular canons (such as that of Prémontre, founded by St. Norbert in 1121), but the vast majority of secular clergy remained deaf to this appeal.

In the final analysis, the most fundamental reason for the campaign waged by the church in favor of clerical celibacy surely lies in the redefinition of relations between clergy and laity that took concrete shape, at the beginning of the eleventh century, in the schema of the “three orders” of society, whose significance has been effectively demonstrated by Georges Duby and Jacques Le Goff. Around the year 1000, in effect, texts of clerical authorship that classified the members of Christian society into three categories or “orders”—those who pray (the clergy), those who fight (the knights), and those who work (everybody else)— began to appear throughout Western Europe.

Specialists in social history have been especially alert to the appearance, within the laity, of a distinction between lords and peasants. But it is no less interesting to note that the secular clergy (bishops, priests, deacons, and so on) found themselves grouped with the monks in a single category, defined by the practice of prayer and, in a hierarchical perspective, placed at the head of the body of society. This tripartite schema thus expressed an unmistakable assertion of the emancipation and primacy of the spiritual estate, which became established over the course of the eleventh century: the spiritual must be freed from the grasp of the temporal authorities, because the spirit is superior to the flesh.

But this preeminence of the spiritual estate was only justified, in the eyes of people of that time, if those who comprised it lived in purity, far from the carnal life—which was likened, in a perspective more Neoplatonic than Christian, to a moral blemish. The advocates of clerical celibacy emphasized the need to raise the status of clergy above that of the laity. Insofar as most of the laity lived within the bonds of marriage and procreated children, priests, who were called to be their leaders and guides, must abstain from doing the same and confirm their superiority by the evidence of their irreproachable purity, whether they were monks or parish clergy. It was only at this price that the church could regain its liberty and fulfill its mission, which consisted in leading the faithful to salvation.

This argument bore all the more weight in that it rested, in certain parts of Christendom (such as northern and central Italy), on broad popular foundations. In Milan and in Tuscany, religious movements uniting large numbers of laypeople with some reforming clergy emerged around 1050 to 1060. These groups—labeled Patarines by their enemies—boycotted religious services performed by married or concubinary priests and rejected their sacraments as ineffective and even pernicious for the salvation of the soul. It is certain that the desire to have worthy and morally uplifting priests was widely shared in this period, including among the ordinary faithful.

But serious differences emerged within Latin Christendom over how best to achieve that ideal. For the Gregorian reformers (who eventually carried the day), only celibacy, lived like a heroic struggle, could lead the clergy back to chastity. Within the clergy, however, differing opinions were voiced in a whole series of treatises—particularly numerous in Germany and in Normandy—that argued that one would have a better chance of obtaining the same result by allowing those priests who so wished to live honestly as married men, and that family life constituted a much more effective remedy for incontinence than did celibacy imposed in authoritarian fashion. But since this current of opinion was linked with circles favorable to the emperor or hostile to papal centralization, it was stifled fairly quickly and, after the victory achieved by the Roman Church in the investiture controversy, no longer managed to make its voice heard.”

- Andre Vauchez, “Clerical Celibacy and the Laity.” in Medieval Christianity

#christian#religion#medieval#early middle ages#high middle ages#history#sexuality#andre vauchez#medieval christianity

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shirley Mallmann, Dior Spring Couture 1998 by John Galliano

#shirley mallmann#dior#christian dior#john galliano#fashion#style#runway#90s#couture#medieval#armor#armour#medieval fashion#medieval armor#medieval aesthetic#dior spring#dior spring couture#high end#fashion style#jewelry

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan of Arc wearing armour and mounted upon a horse at the head of her troops

by Jules Prater

#jules prater#art#joan of arc#jeanne d'arc#engraving#history#medieval#middle ages#hundred years war#europe#european#france#french#knights#knight#armour#chivalry#christianity#christian#saint#saints#horse#horses#sword#swords#religious art#religion

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

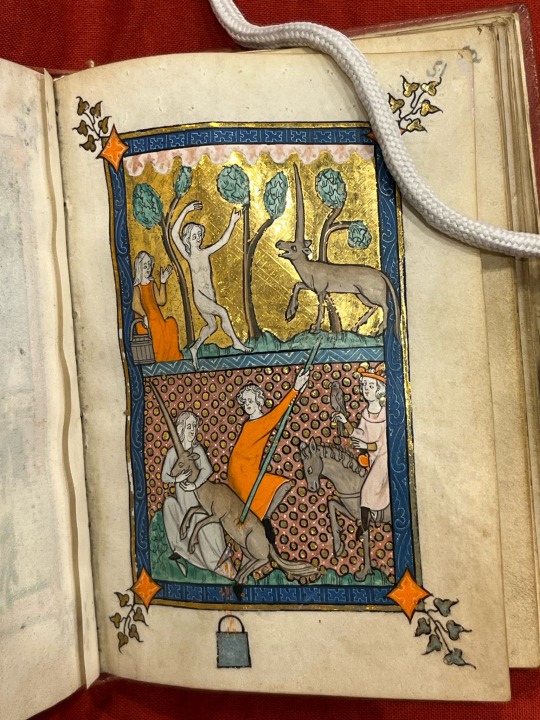

Amazing Christian mystical art from a medieval manuscript!

@cryptotheism Get a load of the colors on this one! I don’t know which one this is because I didn’t call it up myself (and I think this is one of the ones you needed special permission for, anyway), but it’s incredible.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

i don't have the words to articulate it at this moment but there's something about the way that people have specific expectations for "authenticity" and will dismiss anything that falls outside them as a mangled, anglicised version of the thing when actually that is the older and more traditional form of something, it just doesn't match their expectations. obviously in my personal experiences i'm mostly talking about medieval literature here especially medieval irish literature

sometimes this is as simple as spelling – i've had people argue that the name "finn" is anglicised and it should always be "fionn" to be Really Irish, but "finn" is an older spelling, glide vowels are later, if you wanna go real far back it'll be "find" (nd in place of nn is an older spelling pattern). or they'll hear someone say "ogam" and assume they're mispronouncing "ogham" due to lack of knowledge of irish and not consider the fact that medievalists tend to use the older form of the word. or they'll Well Actually you about "correct" terminology which wasn't standardised (and/or invented) until the 20th century

a lot of this is defensive and the result of seeing a lot of people ACTUALLY get this stuff wrong and have no respect for the language. in that regard i understand it, although it becomes very tedious after a while, particularly when people sanctimoniously declare something "inauthentic", "fake", or "anglicised" without doing enough research to realise it's not trying to be modern irish and is in fact correct for older forms of the language

more often however this search for the projected "authenticity" is ideological and has much larger flaws and more problematic implications. "this can't be the real story because it's christian" well... that's the oldest version of the story that exists and it postdates christianity in ireland by about nine hundred years, so... maybe question why you're assuming the only "real" version of irish stories can't be a christian one? this is especially true when it comes to fíanaigecht material tbh, but in general there seems to a widespread misapprehension about ireland's historical relationship with christianity (i have seen people arguing that christianity in ireland is the result of english colonialism which took their "true" faith from them... bro. they were christian before the "english" existed. half the conversion efforts went the other way. please read some early medieval history thank you)

however i also saw someone saying this about arthurian literature lately which REALLY baffled me. "we'll never have the Real arthurian stories only the christianised versions" and it was in the context of chivalric romance. buddy you are mourning something that does not exist. this "authentic" story you're looking for isn't there. that twelfth century story you're dismissing as a christian bastardisation is as "real" a part of this tradition as you're going to get

#in general if you do not want christianity in your medieval literature maybe arthuriana is not the best choice#it is. so fucking christian#as for fíanaigecht. did they think st patrick was there by accident#the arthuriana comment took me out though.#the christianised versions. of chivalric romance.#YOU MEAN THE CHRÉTIENISED VERSIONS?? IS THAT THE PROBLEM?#anyway this is not a pro christianity statement this is a pro historical accuracy statement#medieval#medieval literature

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

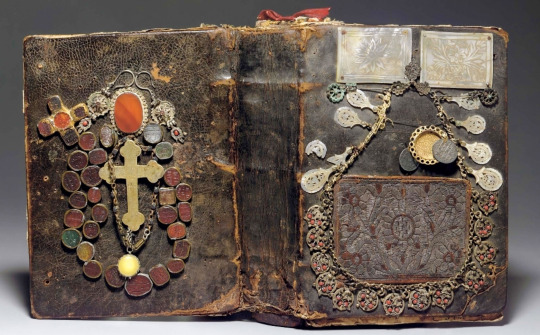

Medieval Armenian Gospel.

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#armenia#book design#book binding#gospel#christian bible#medieval

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Two Crowns, Frank Dicksee, 1900

#art#art history#Frank Dicksee#Sir Frank Dicksee#historical painting#Middle Ages#medieval#religious art#Christian art#Christianity#British art#English art#19th century art#Victorian period#Victorian art#oil on canvas#Tate Britain

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

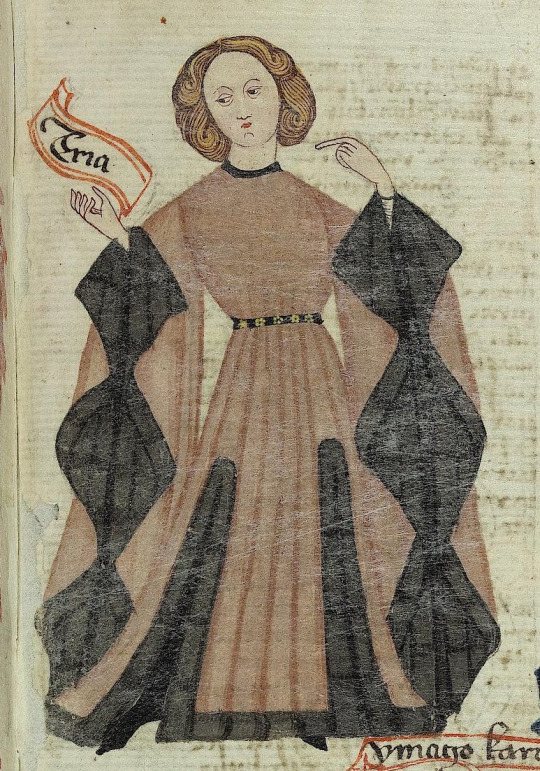

androgynous christ

in john ridewall's "fulgentius metaforalis", bavaria, c. 1424

source: Vatican, Bibl. Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 1066, fol. 243r

#the scrolls says “tria”#15th century#medieval art#fulgentius metaforalis#john ridewall#christ#androgynous christ#gender#fashion#christian iconography#androgyny

1K notes

·

View notes