#morgane

Text

Morgane le Fay / Morgane la Fée

Artist : William Henry Margetson

#william henry margetson#w. h. margetson#morgane le fay#morgane la fée#morgane#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#magic#magie

928 notes

·

View notes

Text

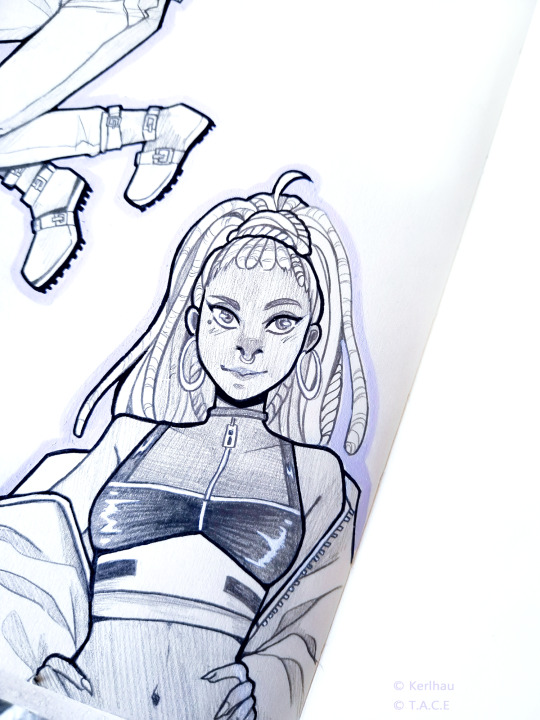

[ FR ] Ma lubie du moment : faire des dessins au crayon, avec des petites parties au feutre à pigment, et les contours et/ou motifs/fonds au posca ! ♥ ça donne un effet que j'aime beaucoup.

……………….. • 🟆 • ………………

[ ENG ] My current fad: making drawings in pencil, with small parts in pigment marker, and the contours and/or patterns/backgrounds in posca ! ♥ it gives an effect that I really like.

#dessin#drawing#illustration#draw#kerlhau#upthebaguette#wip#sketch#croquis#T.A.C.E#the alphabet city elite#oc#original character#Myriam#Morgane#artists on tumblr#the french side of tumblr#art

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthurian myth: Morgan the Fey (1)

Loosely translated from the French article "Morgane", written by Philippe Walter, for the Dictionary of Feminine Myths (Le Dictionnaire des Mythes Féminins)

MORGANE

Morgane means in Celtic language “born from the sea” (mori-genos). This character is as such, by her origins, part of the numerous sea-creatures of mythologies. A Britton word of the 9th century, “mormorain”, means “maiden of the sea/ sea-virgin”, et in old texts it is equated with the Latin “siren”. A passage of the life of saint Tugdual of Tréguiers (written in 1060) tells of ow a young man of great beauty named Guengal was taken away under the sea by “women of the sea”. The Celtic beliefs knew many various water-fairies with often deadly embraces – and Morgane was one among the many sirens, mermaids, mary morgand and “morverc’h” (sea girls/daughters of the sea).

Morgane, the fairy of Arthurian tales, is the descendant of the mythical figures of the Mother-Goddesses who, for the Celts, embodied on one side sovereignty, royalty and war, and on the other fecundity and maternity. In the Middle-Ages, they were renamed “fairies” – but through this word it tried to translate a permanent power of metamorphosis and an unbreakable link to the Otherworld, as well as a dreaded ability to influence human fate. The French word “fée” comes from the neutral plural “fata”, itself from the Latin word “fatum”, meaning “fate”.

There is not a figure more ambivalent in Celtic mythology – and especially in the Arthurian legends – than Morgane. She constantly hesitates between the character of a good fairy who offers helpful gifts to those she protects ; and a terrible, bloodthirsty goddess out for revenge, only sowing death and destruction everywhere she goes. Christianity played a key role in the demonization of this figure embodying an inescapable fate, thus contradicting the Christian view of mankind’s free will.

I/ The sovereign goddess of war

It is in the ancient mythological Irish texts that the goddess later known as Morgane appears. The adventures of the warrior Cuchulainn (the “Irish Achilles”) with the war-goddess Morrigan are a major theme of the epic cycle of Ireland. The Morrigan (a name which probably means “great queen”) is also called “Bodb Catha” (the rook of battles). It is under the shape of a rook (among many other metamorphosis) that she appears to Cuchulainn to pronounce the magical words that will cause the hero’s death.

The Irish goddesses of war were in reality three sisters: Bodb, Macha and Morrigan, but it is very likely that these three names all designated the same divinity, a triple goddess rather than three distinct characters. This maleficent goddess was known to cause an epileptic fury among the warriors she wanted to cause the death of. The name of Bodb, which ended up meaning “rook”, originally had the sense of “fury” and “violence”, and it designated a goddess represented by a rook. The Irish texts explain that her sisters, Macha and Morrigan, were also known to cause the doom of entire armies by taking the shape of birds. Every great battle and every great massacre were preceded by their sinister cries, which usually announced the death of a prominent figure.

The Celtic goddesses of war have as such a function similar to the one of the Norse Walkyries, who flew over the battlefield in the shape of swans, or the Greek Keres. The deadly nature of these goddesses resides in the fact that they doom some warriors to madness with their terrifying screams. One of the effects of this goddess-caused madness was a “mad lunacy”, the “geltacht”, which affected as much the body as the mind. During a battle in 1722 it was said that the goddess appeared above king Ferhal in the shape of a sharp-beaked, red-mouth bird, and as she croaked nine men fell prey to madness. The poem of “Cath Finntragha” also tells of the defeat of a king suffering from this illness. The place of his curse later became a place of pilgrimage for all the lunatics in hope of healing.

The link between the war-goddess and the “lunacy-madness” are found back within folklore, in which fairies, in the shape of birds, regularly attack children and inflict them nervous illnesses. These fairies could also appear as “sickness-demons”. Their appearance was sometimes tied to key dates within the Celtic calendar, such as Halloween, which corresponded to the Irish and pre-Christian celebration of Samain. Folktales also keep this particularly by placing the ritualistic appearances of witches and of fate-fairies during the Twelve Days, between Christmas and the Epiphany – another period similar to the Celtic Halloween. Morgane seems to belong to this category of “seasonal visitors”.

II) The Queen of Avalon

In Arthurian literature, Morgane rules over the island of Avalon, a name which means the Island of Apples (the apple is called “aval” in Briton, “afal” in Welsh and “Apfel” in German). Just like the golden apples of the Garden of the Hesperids, in Celtic beliefs this fruit symbolizes immortality and belongs to the Otherworld, a land of eternal youth. It is also associated with revelations, magic and science – all the attributes that Morgane has. Her kingdom of Avalon is one of the possible localizations of the Celtic paradise – it is the place that the Irish called “sid”, the “sedos” (seat) of the gods, their dwelling, but at the same time a place of peace beyond the sea. Avalon is also called the Fortunate Isle (L’Île Fortunée) because of the miraculous prosperity of its soil where everything grows at an abnormal rate. As such, agriculture does not exist there since nature produces by itself everything, without the intervention of mankind.

It is within this island that the fairy leads those she protects, especially her half-brother Arthur after the twilight of the Arthurian world. Morgane acts as such as the mediator between the world of the living and the fabulous Celtic Otherworld. Like all the fairies, she never stops going back and forth between the two worlds. Morgane is the ideal ferrywoman. The same way the Morrigan fed on corpses or the Valkyries favored warriors dead in battle, Morgane also welcomes the soul of the dead that she keeps by her side for all of eternity. Some texts gave her a home called “Montgibel”, which is confused with the Italian Etna. The Otherworld over which she rules doesn’t seem, as such, to be fully maritime.

The ”Life of Merlin” of the Welsh clerk Geoffroy of Monmouth teaches us that Morgan has eight sisters: Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Thiten, Tytonoe, and Thiton. Nine sisters in total which can be divided in three groups of three, connected by one shared first letter (M, G, T). In Adam de la Halle’s “Jeu de la feuillée”, she appears with two female companions (Arsile and Maglore), forming a female trinity. As such, she rebuilds the primitive triad of the sovereign-goddesses, these mother-goddesses that the inscriptions of Antiquity called the “Matres” or “Matronae”. In this triad, Morgane is the most prominent member. She is the effective ruler of Avalon, since it was said that she taught the art of divination to her sisters, an art she herself learned from Merlin of which she was the pupil. She knows the secret of medicinal herbs, and the art of healing, she knows how to shape-shift and how to fly in the air. Her healing abilities give her in some Arthurian works a benevolent function, for example within the various romans of Chrétien de Troyes. She usually appears right on time to heal a wounded knight: she is the one that gave a balm to Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, to heal his madness. In these works, Morgane does not embody a force of destruction, but on the contrary she protects the happy endings and good fortunes of the Round Table. She is the providential fée that saves the souls born in high society and raised in the “courtois” worship of the lady. However, her powers of healing can reverse into a nefarious power when the fée has her ego wounded.

III/ The fatal temptress

In the prose Arthurian romans of the 13th century, Morgane can be summarized by one place. After being neglected by her lover Guyomar, she creates “le Val sans retour”, the Vale of No-Return, a place which will define her as a “femme fatale”. This place transports without the “littérature courtoise” the idea of the Celtic Otherworld. Also called “Le Val des faux amants” (The Vale of False Lovers), “le Val sans retour” is a cursed place where the fée traps all those that were unfaithful to her, by using various illusions and spells. As such, she manifests both her insatiable cruelty and her extreme jealousy. Lancelot will become the prime victim of Morgane because, due to his love for Queen Guinevere, he will refuse her seduction. The feelings of Morgane towards Lancelot rely on the ambivalence of love and hate: since she cannot obtain the love of the knight by natural means, she will use all of her enchantments and magical brews to submit Lancelot’s will. In vain. Lancelot will escape from the influence of this wicked witch. In “La Mort le roi Artu”, still for revenge, Morgan will participate in her own way to the decline to the Arthurian world: she will reveal to her brother, king Arthur, the adulterous love of Guinevre and Lancelot. She will bring to him the irrefutable proof of this affair by showing her what Lancelot painted when he had been imprisoned by her. The terrible war that marks the end of the Arthurian world will be concluded by the battle between Arthur and Mordred, the incestuous son of Arthur and Morgan. As such, Morgan appears as the instigator of the disaster that will ruin the Arthurian world. She manipulates the various actors of the tragedy and pushes them towards a deadly end. It should be noted that any sexual or romantic relationship between Arthur and Morgane are absent from the French romans – they are especially present within the British compilation of Malory, La Mort d’Arthur.

Behind the possessive woman described by the Arthurian texts, hides a more complex figure, a leftover of the ancient Celtic goddess of destinies. Cruel and manipulative, Morgan is fuses with the fear-inducing figure of the witch. Despite being an enemy of men, she keeps seeking their love. All of her personal tragedy comes from the fact that she fails to be loved. Always heart-sick, she takes revenge for her romantic failure with an incredible savagery. Her brutality manifest itself through the ugliness that some text will end up giving her – the ultimate rejection by this Christian world of this “devilish and lustful temptress”. “La Suite du Roman de Merlin” will try to give its own explanation for this transformation of Morgane, from good to wicked fairy: “She was a beautiful maiden until the time she learned charms and enchantments ; but because the devil took part in these charms and because she was tormented by both lust and the devil, she completely lost her beauty and became so ugly that no one accepted to ever call her beautiful, unless they had been bewitched”. In this new roman, she is responsible for a series of murders and suicides – and as the rival of Guinevere, she tries to cause King Arthur’s doom by favorizing her own lover, Accalon. Another fée, Viviane, will oppose herself to her schemes.

The demonization of the goddess is however not complete. Morgan appears in several “chansons de gestes” of the beginning of the 13th century, and even within the Orlando Furioso of the Arisote, in the sixth canto, in which she is the sister of the sorceress Alcina. She is presented as the disciple of Merlin. Seer and wizardess, she owns (within Avalon or the land of Faerie) a land of pleasure, a little paradise in which mankind can escape its condition. At the same time the Arthurian texts discredit her, she joins a strange historico-pagan syncretism, by being presented as the wife of Julius Caesar, and as the mother of Aubéron, the little king of Féerie.

After the Middle-Ages, the fée Morgane only mostly appears within the Breton folklore (the French-Britton folklore, of the French region of Bretagne). There, old mythical themes which inspired medieval literature are maintained alive, and keep existing well after the Middles-Ages. Morgane is given several lairs, on earth or under the sea. In the Côtes-d’Armor, there is a Terte de la fée Morgan, while a hill near Ploujean is called “Tertre Morgan”. There is an entire branch of popular literature in Bretagne (such as Charles Le Bras’ 1850 “Morgân”) where the fée represents the last survivor of a legendary land and the reminder of a forgotten past. She expresses the nostalgia of a lost dream, of a fallen Golden Age. True Romantic allegory of the lands and seas of Bretagne, she most notably embodies the feeling of a Bretagne land that was in search of its own soul.

However, it is her role of “cursed lover” that stays the most dominant within the Breton folklore. The vicomte de La Villemarqué, great collector of folktales and popular legends, noted in his “Barzaz Breiz” (1839) that the “morgan”, a type of water spirits, took at the bottom of the sea or of ponds, in palaces of gold and crystal, young people that played too close to their “haunted waters”. The goal of these fairies was to kidnap them to regenerate their cursed species. This ties the link between these “morganes” (also called “mary morgand”) and the Antique “fairy of fate”. Similar names, a same love of water, and the presence of the “land below the waves”, of a malevolent seduction – these are the permanent traits of Morgane, who keeps confusing and uniting the romantic instinct for love, and the desire for death. More modern adaptations of the legend (such as Marion Zimmer Bradley’s novels) weave an entire feminist fantasy around the figure of this fairy, supposed to embody the Celtic matriarchy.

#arthuriana#arthurian myth#arthurian legend#morgane#morgan#morgan le fey#fée#french folklore#folklore of bretagne#celtic mythology#irish mythology

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morgane. From «Venezia», 2010

Photo: Mona Kuhn

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇧🇪 Morgane - Nous on veut des violons

#Morgane#Nous on veut des violons#Belgium esc#Belgium eurovision#esc 1992#eurovision 1992#cute lil' entry :)

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think abt Gramorr x Morgainne ship?

ya know, i actually unironically like it a lot. like, "Dance Craze" had some minimal interactions between the two, but even so you could tell they had history.

also the "even from another dimension, your stench is unmistakable" line from Morgane was so iconic, she's such a queen.

all i know is she knows how to put him in his place and i love her for that.

i kinda see them as old flings. like, maybe they were a thing back in the day, maybe even studied magic together, but then gramorr, being the power hungry bastard he is, slowly started to turn to the darkside, and she was just left with no choice but to watch the person she loved the most turn into a self-absorbed, bitter and cruel monster, knowing she had no power to stop it from happening.

i'd honestly love for their relationship to be explored more in season 3. honestly, i think with the whole "banes being the mastermind" thing, maybe we'll get a backstory for gramorr, and hopefully his relationship with morgane will get touched upon as well, even if just a little

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

redid designs for my OCs for the umpteenth time (. .)' might add/edit a couple things for some of them but i'm satisfied for now!! i'll get to my other OCs later <3

#oc#ocs#original character#alex#clement#cynthia#eddy#electra#ellis#elvis#jack#jayden#léane#morgane#ninou#refs#reference#oc reference#oc ref sheet#woor's art

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morgane Alvaro is a constant mood:

#morgane#morgane Alvaro#HPI#Morgane detective geniale#tv series#tv series addict#adam karadec#tf1 hpi#tf1#audrey fleurot#mehdi nebbou#morgadec#morgane x karadec#otp

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

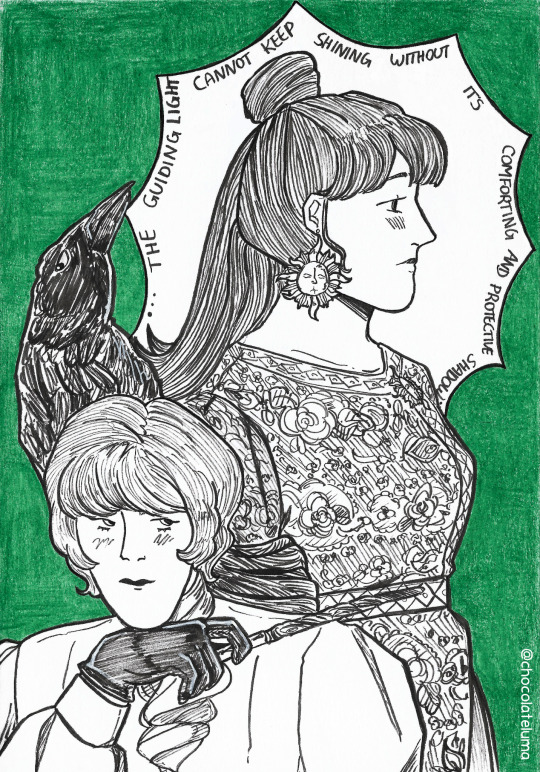

I drew Yseult a sister, her name is Morgane. First pic is around 1969/70 and the second one is 1980.

#still don't know how to draw crows !!!#traditional art#artists on tumblr#original characters#oc#chocolart24#apos#yseult#morgane#witches

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday night. Just got a VPN specifically so me and the wife can binge watch La Fleurot in HPI. See you in a month or so ...

@bourbon-ontherocks

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jour 25 • Cuir

#dessin#drawing#illustration#draw#kerlhau#upthebaguette#the french side of tumblr#the alphabet city elite#TACE#Morgane#leather#cuir#inktober#inktober2023#ink#inked#encre#encré#artists on tumblr

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fantasy in modern Arthuriana (3)

A follow-up of the previous post.

If the medieval Arthurian literature accumulates the tales of the feats of the heroes, the detail of their thoughts is mostly left in the shadows. Like the prose of Malory says for a good number of knights, “He said but little”, “He seyde but lytyll”. In other words, the Arthurian romance of the Middle-Ages is concerned with actions, not words. It is even truer when it comes to the female characters, a minority among the Arthurian adventures, and who are limited to a specific set of roles: queen and giver of goods (Guinevere), virgin and emissary of adventure (Linette), sad and dying lover (the lady of Escalot)… Such a restriction of functions invited in itself a fleshing out of the characters, not to say a remake. It is even stronger when we come to the sorceresses, another type of women largely used by modern rewrites, probably because they are precisely among the female characters the only one who, in the Middle-Ages, can freely participate to the action. [It is true that the maidens who guide the knights throughout their quests seem to also have an important area of action, but very often it is suggested that they belong to the supernatural world. In the Morte Darthur, the three ladies met by Gawain, Yvain and Marhalt embody the three ages of woman; Linette, who guides Gareth and helps him in his love, is able to “piece back together” and resurrect a dead knight].

If the revisited Arthurian literature likes to give a voice to women, these characters so often overshadowed by their male counterparts who are always in a war or on a quest, it is probably because at first it was an innovation. Since everything was already said in the past, one of the simplest ways to renew the tale is to give a voice to the mutes, here women. This innovation was very quickly assimilated to a feminist, though not always feminine, current, under the major influence of Marion Zimmer Bradley and her “Mists of Avalon”. In it the focus is placed on the enchantresses, Viviane and Morgan mainly. Given the huge success of these novels, the characters within it had a tendency to influence, consciously or not, ulterior treatments of the Arthurian fiction and its female characters. As such, when Cindy Mediavilla wrote about “The Mists of Avalon”, she said “[it] sets the standard for Arthurian fiction told from the female perspective. Heavy with images of the Goddess versus the male dominance of Christianity, this story (…) is highly recommended for all fans of the genre, especially young feminists seeking alternate renderings of the legend.” (Arthurian Fiction – An Annotated Bibliography). Outside of this “feminist” dimension, there is still a great number of recurring trends discernable within contemporary novels that have a direct influence over the idea of magic, and by extension, the genre or sub-genre to which the Arthurian novel belongs. [Maureen Fries heavily nuanced the feminism at work here: Viviane is killed by Balin, Nimue killed herself after betraying Kevin, Niniane is used then killed by Mordred, Morgan ens up admitting the universality of religious symbols even assimilated the Great Goddess to the Virgin Mary… “Indeed, real empowerment escape all of the women in the book except perhaps (and indirectly) Gwenhwyfar, whose narrow Christianity Arthur embraces.” – “Trends in the Modern Arthurian Novel”, in “King Arthur Through the Ages”]

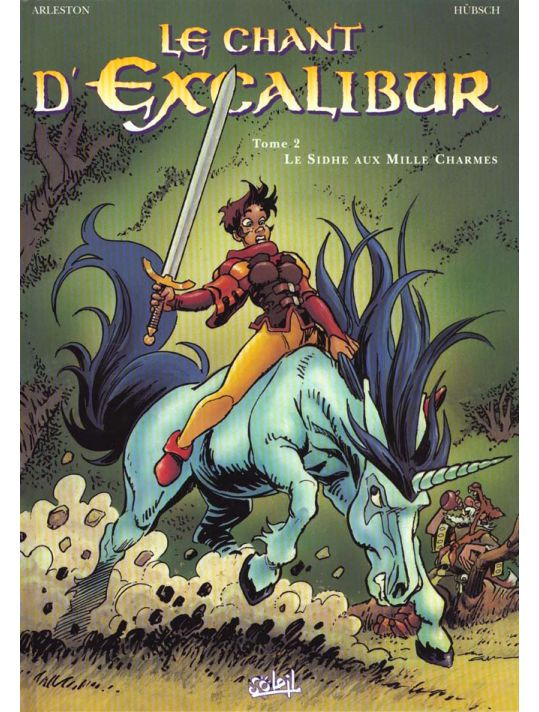

The duo Viviane/Morgan is most often treated as an antagonism. In line with the sources, Viviane appears as a kind fairy who raises Lancelot and acts to help Arthur dispel the schemes of his malevolent half-sister. [With a rare set of exceptions, including Fred T. Saberhagen’s Dominion which subverts many preconceptions by making Viviane a bloodthirsty high-priestess and Merlin a drunkard with a failing magic, closer to the buffoon that appears in the BD “Le chant d’Excalibur” by Arleston and Hübsch than to the medieval prophet] But the shadows among the medieval characters are enough to allow anyone to interpret them in various ways. Indeed, this sweet Lady of the Lake is also the woman that used Merlin to augment her own power before imprisoning him for all of eternity. And Morgan is at the same time the enemy of the Round Table and the crying sister which takes a dying Arthur in her arms to carry him away to Avalon. This ambiguity is complexified by numerous possible divisions or assimilations: Viviane is also Niniane or Nimue, except when they are all different characters. Mordred is either the son of Morgan, or of her sister Morgause. The sources vary a lot about these facts, and so do the modern authors – and the same thing applies to the love-romances that are woven between the enchantresses and their victims, between Merlin and his students. [Within the “Lancelot-Graal”, Morgan is said to have been the student of Merlin, but she is different from Viviane, another of his student who ended up imprisoning the wizard. Yet, there is a temptation to synthetize in one character the student, the mistress and the enemy. On another subject, the hatred of Morgan for the Round Table could be explained by her love for the cousin of the queen, a love that said queen managed to destroy. As early as the Middle-Ages we see the beginning of, not a rehabilitation, but at least excusing circumstances for Morgan’s criminal behavior towards her brother and his kingdom.]

The opposition of benevolent sorceresses and malevolent wizardesses is inscribed in a broader way within a specific conception of magic. If we can easily admit that there are things such as “white” or “black” magic, if we admit that there are wizards opposing witches (or necromancers), than this duality invokes the symbolism of good versus evil. In the context of the Arthurian legend, the magic that serves Arthur and his chivalrous ideal is supposed to be white, while the one of those that stand against him is black. It is the case with Stephen Lawhead or Gillian Bradshaw, where the future of the world depends on a battle between Light and Darkness. [Gillian Bradshaw created “Hawk of May” and “Kingdom of Summer”. The expression “Kingdom of Summer” is also very present within Lawhead’s work, reinforcing the link between those two authors. Lawhead prefers to name two of his characters Gwalcmai and Gwalchavad, “hawk of May” and “hawk of Summer”, rather than Gawain and Galahad. As for the opposition of the Light and the Darkness, we can be reminded of the two sides of the Force within “Star Wars”, which is filled with Arthurian references.]

But this symbolism also evokes several moral values that already prepare the question of how magic and religion coexist. Already in the Middle-Ages the limits are blurry when it comes to separating magic, religion, and science – especially medical science. (See Richard Kieckheffer’s Magic in the Middle-Ages) The knowledge of plants can be seen with suspicions, and the various invocations look very similar to each other, no matter if they are for a saint or a demon. All those contradictions coexist within the modern Arthurian literature as a whole, even though if most authors take care to establish a cohesive magic system within the setting of their tale.

As such we frequently have an opposition between magic and religion, where magic relies on nature and traditional beliefs of which women are the bearers, while religion relies on a recent importation of Christianism and is presented as repressive and misogynistic. It is the case in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s work, where the magic is natural, “sympathetic”, against fanatical Christians who only dream of absolute power. Bernard Cornwell depicts a desacralized Christianity in an even darker light, as a religion only concerned with accumulating wealth by exploiting naïve pilgrims. The prayers are emphatic but useless, and the priest Samson, a future saint, has a rat-like face, a strong dislike of Guinevere and Nimue, as well as a heavily hinted preference for very young monks. The only Christian that is acceptable to the eyes of the narrator is the bishop Bedwin, who turns out to not be a quite faithful Christian, and an emblematic example of the improbable reconciliation of the extremes within modern Arthurians – a treatment of magic an religion that prefers the opposition of forces rather than their complementary. It forms indeed an explosive situation that is able to captivate more the attention of a reader rather than an idyllic statu quo. As such, what imposed itself as an Arthurian topos is the idea of a mostly pagan Britain attacked by the hegemonic projects of Christianism – despite the historical and archeological informations contraicting this view. The historicizing of the Arthurian setting is thus sometimes independent from the story, while not negating its realism or “vraisemblance”. [Adam Roberts, in “Silk and Potatoes” pointed out that in Lawhead’s work the Briton peasants are wearing silk, which is highly improbable, and that they cook with potatoes, an obvious anachronism.]

Stephen Lawhead tries to have a pacific shift from the old religion and its beliefs (assimilated to magic) to the Christian religion of the God of love. Taliesin, then Merlin, both have a revelation of the unicity of the divine, and as such their bardic invocations are now addressed to the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, but they stay unchanged in language or effect. What was once a spell or a trick becomes a miracle. Lawhead’s tale however is flawed by an oversimplification. If all this “magic” comes from God, then where do Morgian’s wicked powers come from? The unbreakable faith of Merlin within the superiority of God over Satan is admirable in a catechism context, but it removes an essential tool of the tale: its suspense. A duel between Morgian and Merlin during which the latter won’t suffer any blow, protected as he is by the armor of his faith, is quite disappointing, not to say boring. And what about the magic of the Small Folks, which seems to need a technical learning? The tale cannot fully escape a certain number of expectations, such as the oppositions between white and black magic, or between paganism and Christianity, or the presence of another “fairy”-like people cohabiting discreetly with the Britons. As such, while the attempt at Christianizing the supernatural is interesting because quite rare today (though it was very common in the Middle-Ages), is works badly.

It is a testimony of the weight of obligatory elements within the modern Arthurian fiction, a fiction that was shaped as much by contemporary successes as by, if not more than, its relationship to the medieval sources. If the articulation between magic and religion can be done in various ways, it stays in many cases a strong opposition between white magic/women/tradition, and religion/men/change. And since, outside of Merlin, most of the wizards of the medieval romances are women, magic is thus colored by femaleness, not to say feminism. In a world where male characters kill each other with weapons, women heal wounds with herbs and words. The image of the healer-Viviane, sweet and motherly, is opposed to the brutality of a world of warriors. At another level, it seems that the sorceresses embody the “fantasy temptation” while the warriors embody the “historical temptation”. [Raymond H. Thompson notes the gendered polarity within Arthurian rewrites since WWII, between a feminine movement closer to heroic fantasy, and a male movement, bloodier and closer to sword and sorcery (“Arthurian Legend in Science-Fiction and Fantasy”, in “King Arthur Through the Ages”)] As such, the novels that focus on the female characters also focus on magic, while those concerned with men and their wars are historicizing the Arthurian era. As Thomson said: “The focus thus shifts from warfare to the political and domestic conflicts that raise Arthur to power, and then destroy him.”

But if this is the case, where do we place evil wizardesses such as Morgan? They find their place within the rewrites that use abundantly of the supernatural, which is then vast enough to include both good and evil. Moreso, if the Middle-Ages offered a complex depiction of the enchantresses, the dark side of Morgane/Morgause stays dominant. Modern rewrites thus very easily use this malevolent aspect. It is the case of T.H. White whose second book, “The Witch in the Wood” was later renamed “The Queen of Air and Darkness” to designate Morgause. Gillian Bradshaw also depicts a fully evil Morgause who tries to teach her son Gwalchmai the occult arts. But he prefers the side of Light, and he joins Arthur and his knights. We find these two influences within Lawhead’s Morgian, also qualified of “Queen of Air and Darkness”, and who serves the Devil while Merlin fights by the sides of Arthur, the champion of Light. This distribution of the magical forces intensifies the motif of the conflict on several levels. The Darkness can be historical: the one of the “Dark Ages” at the beginning of the Middle-Ages, the one of the various disasters (war, plague, famine, insecurity) brought by the Saxon invader. But in a cyclical point of view, which extends the mythical side of the Arthurian theme even in rewrites that try to be historical, the fight between Good and Evil becomes recurrent. Arthur and Morgan (or her avatars) are easily identifiable archetypes. This repetition ability highlights the non-temporality of the myth and justifies the growing number of Arthurian rewrites: the myth is eternal, and thus must be eternally retold.

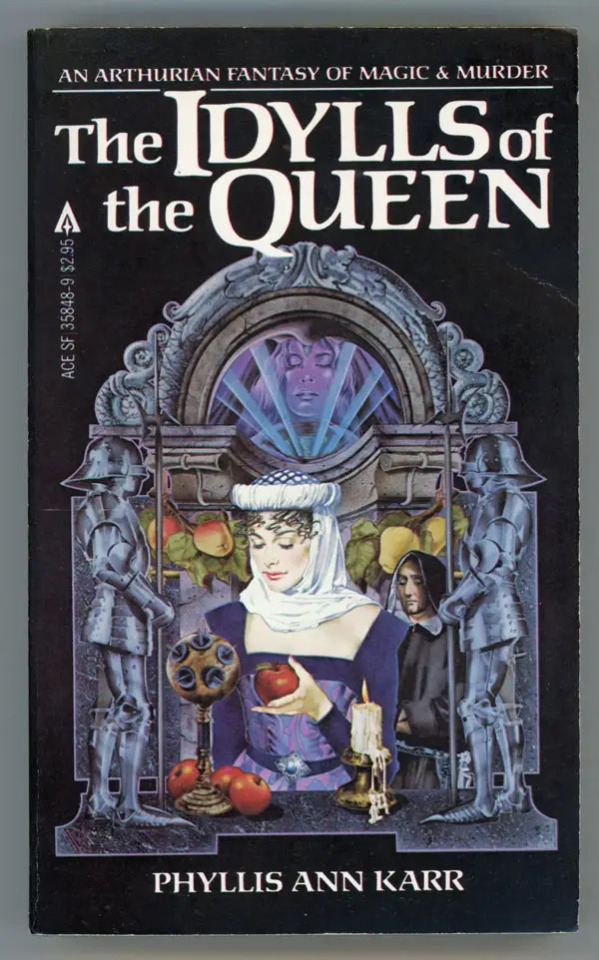

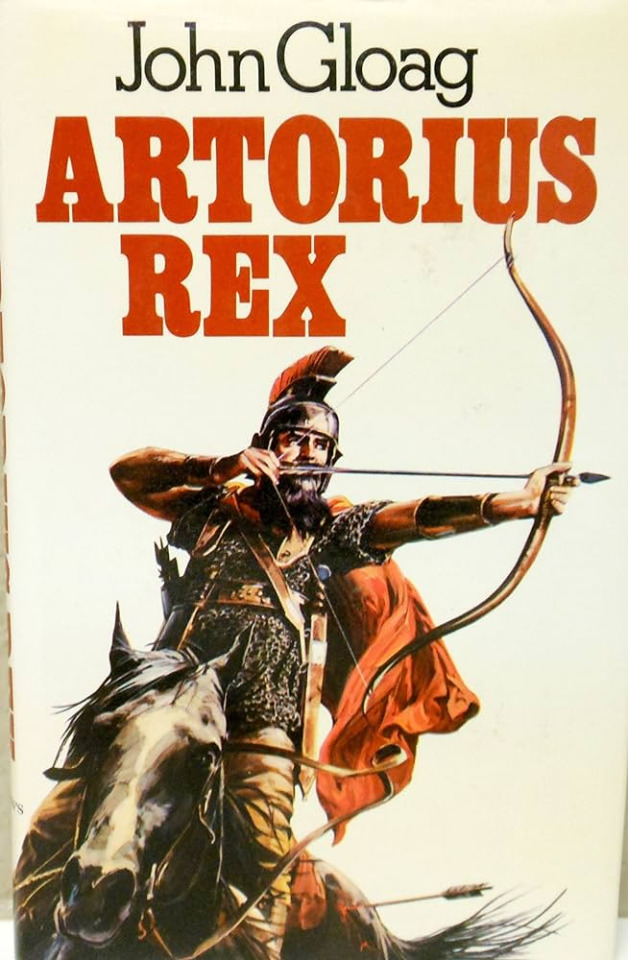

But these retellings do not simply replay the classical gigantic fight between the servants of the Light and those of the Darkness. A quite important number of modern authors chose to rehabilitate the unloved characters, mostly by giving them a voice. As such, the grudge-bearing, jealous witch of the medieval romances disappears, replaced by a loving and healing sister. Phyllis Ann Karr, within “The Idylls of the Queen”, offers a clever treatment of the character of Morgan, rehabilitated by a systematical refutation of the rumors, those that will become the “official” version of the legend later on. Morgan recognizes the facts, but offers other explanations for them, motivations misunderstood by her contemporaries and thus doomed to stay unknown (until the modern author reveals them, of course). This modern process of subverting the medieval stereotype (here the wicked witch that becomes the most faithful and loving servant of the Arthurian grandeur, pushing the devotion to a refusal to be offended by her bad reputation) can be declined in an infinite way, even on a parodic tone. Thomas Berger offers an anemic Galahad barely able to ride a horse, instead of the invulnerable knight supposed to be an “improved” version of his father Lancelot. John Gloag paints a Merlin prone to mistakes within his prophecies, and makes the entire announced and expected Arthurian glory a huge prank. T.H. White made his Lancelot ugly, where the Middle-Ages encouraged to see him as beautiful since he was “the perfect lover”.

However, as with all process, this technique has its limits. By constantly subverting the reader’s expectations, we create new demands. Morgan is constantly rehabilitated, Lancelot is constantly made darker or disgraced by modern authors, who are numerous (maybe too numerous?) in trying to set themselves apart from their predecessors. Cornwell’s Lancelot is an arrogant coward, while in other novels he simply disappears as the lover of the queen and/or the right arm of Arthur. He is replaced by characters deemed more historical (Bedwyr for Rosemary Sutcliff or Joan Wolff), or by characters invented for the plot (John Gloag’s Wencla, Victor Canning’s Borio). As if suppressing the greatest Arthurian knight was needed to surprise the modern reader. Under such a light, the rehabilitation of witches as misunderstood sorceresses is almost becoming more stereotypical than the original model of the “truly wicked”.

It seems that, for now, the only true novelty that modern authors have not dared is an Arthurian novel without Arthur. But this path seems to be under exploration: Arto, Artos, Artorius, all spellings that can establish a difference with the original character is welcome, especially if it establishes a gap between the foggy and uncertain time when the legend was born and the era of the modern rewrite. The exploitation of the Arthurian prehistory is another sign of it. The Arthurian novel without supernatural is also another facet of this quest for a renewal. But since the “pure” historical novel has already been done in the past, the “new novelty” is the reintroduction of the marvelous – not in its original form, but in a subtler one influenced by the past historicizing. We entered an era of “rationalizing” and “walling” of the “merveilleux”. Rationalizing the wonderful means exploiting events and actions that can be given the appearance of magic ; “walling” the marvelous means limiting magical abilities to a specific group of characters, usually non-humans and thus marginalized.

#fantasy#arthuriana#arthurian novels#arthurian literature#viviane#lady of the lake#morgane#morgan le fay#magic#magic system#fantasy novels#fantasy worldbuilding#magic vs religion#merlin#nimue#morgause#lancelot

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Character poster of Aran Kei as Morgane

#la legende du roi arthur#la légende du roi arthur#le roi arthur#king arthur musical#キングアーサー#japan#aran kei#morgane#photo

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

doodled two of my girls with outfits from pinterest <3

6 notes

·

View notes