#mycenaean greece

Text

Odyssey's ship leaving Ithaca (2024)

Penelope and Telemachus look at Odysseus's ship sailing away...

Illustration for Homer's Odyssey

#marysmirages#mycenaean greece#ancient greek mythology#bronze age#odysseus#odyssey#penelope#telemachus#art#homer#ship#sea#ancientgreece

687 notes

·

View notes

Text

#my art#tsoa#the iliad#the song of achilles#patrochilles#patchilles#patroclus#patroclus and achilles#achilles#madeline miller#book#💅🏽#mycenaean greece#greek mythology

795 notes

·

View notes

Text

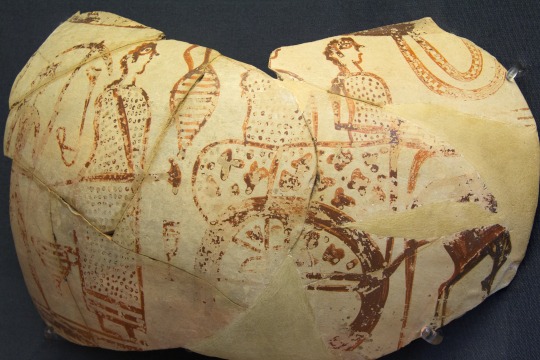

A seated goddess before a procession of seahorses. Mycenaean gold ring, artist unknown; 15th cent. BCE. From Tiryns; now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Photo credit: Zde/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Mycenaean Greece#Aegean Bronze Age#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Aegean art#Bronze Age art#Mycenaean art#ring#jewelry#jewellery#metalwork#gold#goldwork#NAM Athens

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hera

#hera#greek mythology#olympians#classics#tagamemnon#classical mythology#era#hera greek mythology#mycenaean greece

469 notes

·

View notes

Text

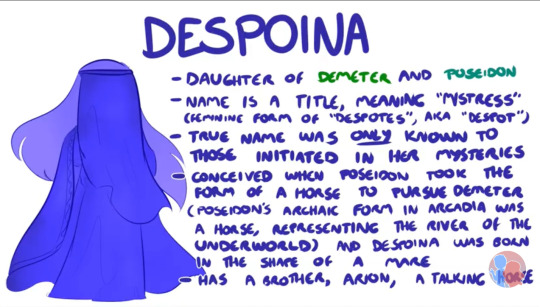

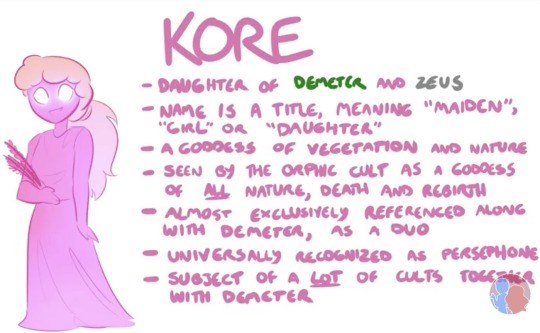

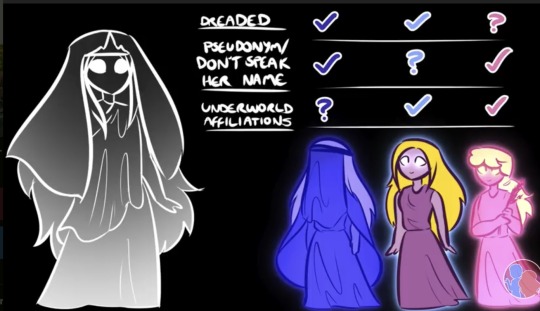

#osp#overly sarcastic productions#demeter#persephone deity#greek mythology#hades and persephone#hades x persephone#hades#despoina#kore#persephone#death aesthetic#a matter of life and death#spring#life and death#orphism#dreaded#underworld#mycenaean greece#greek goddess#greek myth#mycenae#earthshaker#oceancore#deathcore

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

52 Project #47: Nobody Believes Cassandra

This story was inspired by this thread: https://www.tumblr.com/korben600/655709048467062784/teaboot-spectrum270-lectorel

My primary research material was Emily Wilson's translation of the Odyssey, but I also heavily consulted Euripides' "Hecuba" and "The Trojan Women", several online translations of the Iliad, and lots and lots of Wikipedia and other online resources, including online maps of Odysseus' journey.

In my introduction to this story, "Song of Jane", I specifically called out @teaboot, @elidyce, and @korben600 as contributors to the thread that inspired this story, but there were many other contributors to that thread as well. My specific take on the story is my own, however, and a good bit less light and fluffy than some contributors might have preferred. And, as I was trying to say by writing an entire poem in iambic pentameter about it :-), my original, greatest inspiration, was my mother, one of the world's biggest Odysseus fangirls. I want to think she would have enjoyed this story.

The night after he’d failed to persuade the rest of the Greeks that Ajax should be put to death for defiling a Trojan princess in Athena’s temple, Odysseus dreamed that Athena appeared to him, and she was angry.

“After everything I did for you Greeks!” she snapped at him coldly, her grey eyes the color of dark stormclouds. “I have fought on your behalf in the council of the gods, spoken for you, protected you, for the ten long years of this war, and this is how you repay me?”

“Divine Athena, I agree with you. This is absolutely preposterous.” Odysseus spread his hands. “But I am only one man. I argued with all of my skill that Ajax should die for what he did in your temple, when Cassandra of Troy took refuge there and called on your protection. But Ajax has himself taken refuge in your temple, swearing on your image that he is innocent, and the men who fought beside Ajax these long ten years are loathe to believe the worst of him. We are but mortal men; unlike you and the rest of the immortal gods, we cannot see inside the minds of our fellow mortals. How can I prove the truth of Ajax’s deed to men who don’t want to see it?”

“You are Odysseus the silver-tongued, the man whose cleverness and gift with words are renowned throughout all the civilized lands. Are you telling me that you, of all men, couldn’t persuade your fellow Greeks to punish Ajax for his crime against me?”

“I’m sorry, great goddess, but yes, that’s what I must tell you, for I’d never dare tell you a lie. Even I can’t convince men who want more than anything else not to believe me. The thought that they would have to execute a man who they’ve fought alongside, for the sake of a woman whose nation we’ve conquered—”

“It is not for her sake! It’s for mine!” Athena raged. “Cassandra asked my protection, but it is the law of the Gods that we cannot do anything against the will of other gods, without negotiating and meeting in council, and Ajax was protected by my own allies among the gods, for he is a Greek, and my allies and myself have chosen to defend the Greeks. I could strike him down, if I negotiate with the other gods toward that end, but if you Greeks won’t discipline your own man for betraying me, the god who has protected you and fought for you, then all of you will suffer my wrath.”

“Then tell me how I can sway them, great Athena. Tell me what proof I can offer them. They will not take the word of the woman we have taken as a captive; they will not take the word of the seer Calchas; they will not take my word when I have nothing to offer them but dreams. What evidence can I present to them to prove that the ones who say Ajax defiled your temple are telling the truth?”

Athena shook her head. “If you won’t accept the word of the victim and you won’t accept the word of the seer who saw it, then there is no proof you will accept.”

“My goddess, I accept your word, and the words of Calchas, who has always served us well as a seer. But the rest of my comrades—”

“Then they can suffer,” Athena said. “I have sent omens, I have sent dreams and visions. They sacrificed Agamemnon’s oldest daughter Iphigenia to Artemis, ten years ago, because Calchas told them it was needed, and Artemis’ wrath was abated, and you were all able to sail to Troy. You can kill a young woman on Calchas’ word, to appease Artemis, but you cannot kill a warrior in his prime to appease me?”

Odysseus sighed. “My comrade Greeks are men, and like most men, they consider the worth of a man greater than the worth of a woman. If Agamemnon had had to sacrifice his son, I doubt we would ever have come to Troy.”

Athena laughed mockingly. “And the worth of a goddess?”

“They worship you, divine Athena. No one doubts your power. What they doubt is the word of those of us who say Ajax raped Cassandra in your temple.”

“Iphigenia did nothing wrong. It was her father’s sin against Artemis that she died for. I want Ajax to die for his own sin. Calchas was the seer who called for both. Why sacrifice the innocent girl to Artemis, but refuse to sacrifice the guilty man for my sake?”

“Great goddess, I know your question is rhetorical, for in your wisdom you must know the answer; you are testing me to see if I know. So I will tell you the answer you already know: they do not believe Cassandra, for she is a woman, and a prize of conquest. They do not want to believe Calchas, because they don’t want to have to kill their comrade. And they don’t want to believe me, for the same reason.”

“Well.” Athena raised an eyebrow. “If their love for their comrade is greater than their desire to escape my wrath, so be it. I will ask Poseidon to punish them as they leave Troy’s harbor, on my behalf.”

“I hope you will see fit to forgive me and my ships from that punishment, divine Athena,” Odysseus said. “I have done the best any mortal can do, but Ajax left no proof of what he’d done. Even if we could prove he defiled Cassandra, we cannot prove that he did it in your temple, after she asked you for sanctuary. And they would believe you, if you appeared in their dreams as you appear in mine, but in your divine wisdom you have chosen not to do that. No mortal can convince another who wants very much not to be convinced. Unless you appear to them as well, there is no more I can do.”

Athena laughed. “Oh, how very like you that is! You’re loyal to your fellow Greeks, until you hear their punishment is inevitable, and then you ask for special favor, to be spared their fate.”

“You know me, my goddess.” Odysseus spread his hands. “It has long been my curse to suffer from the stupidity of others when they refuse to heed my words. Fortunately, my reputation has saved me from that fate, most of my life, but against some forms of stupidity, even you the immortal gods contend in vain. How can I, a mortal, fight what you the mighty and deathless cannot? So yes, I do ask, for I’ve tried as hard as a mortal can to see your will be done, and if I’ve not succeeded at the task, it’s not for lack of effort. I’ve served you as best I can, all my life. Surely you can take that into account, and spare my ships.”

Athena’s gray eyes pierced into his for an uncomfortably long moment of silence, but Odysseus did not cast his eyes down, for to do so might make Athena think he was ashamed of meeting her gaze. Finally she said, “There is a way, if you are truly the clever man I think you are.”

“I will do whatever you suggest.”

“Go to the girl Ajax defiled and talk to her.”

Odysseus waited for the rest of the instructions. They didn’t come. “And that’s all I must do?”

“No, but what you must do once you talk to her? You will either figure that out when you talk to her, or you won’t. If you are as clever as I think you are, you will find the way to escape your doom.”

And then he woke.

***

“Odysseus,” the princess Cassandra of Troy said bitterly. “The man who has brought about my family’s misfortunes. Why exactly should I want to speak with you?”

Odysseus shrugged. “Perhaps you don’t. But the goddess Athena directed me to do so, in my dreams. Perhaps she wants to give you retribution against the man who violated you, and by talking to you, I will find the way to do it.”

Cassandra laughed. The bitter note never left her voice. “You won’t.”

“Why are you so sure?”

“Because I see the future.” Her eyes glittered. “I knew what doom was coming to us all long before it came, and I know what doom awaits me now. You will not persuade your fellows to kill that man, and what does it matter? Agamemnon will take me as his concubine, and that is no more my will or choice than it was to give in to your soldier’s desires. And then I will die, and Agamemnon himself, murdered by his wife and her lover, and there is no evading any of it.”

Odysseus frowned. “That’s ridiculous. Clytemnestra would never take a lover, and she most certainly wouldn’t kill her own husband.”

“And of course!” Cassandra laughed again, the high-pitched cackle of near-madness. “Of course you don’t believe me. Nobody believes me! That’s my curse!”

Odysseus decided to humor the poor girl, obviously driven mad by her family’s misfortune, since he had not yet learned anything from her he could see any way to use to avoid Athena’s wrath, and he knew the goddess wouldn’t have directed him here if there was nothing. “A curse, of course. That must be very hard for you.”

“You mock me, but you won’t mock when you meet the fate awaiting you, Odysseus of Ithaca. You will suffer for years before you see your homeland again. I will be safely in Hades’ realm, beyond all earthly suffering, while you watch everyone who trusted in your leadership die.”

“That’s not going to happen,” Odysseus snapped, needled despite himself at the words of a helpless woman throwing curses at the man who’d caused the defeat of her city. “You’ll live a long life as Agamemnon’s favored concubine and bear him sons, and I will see my wife and son again before the year is out.”

“Oh, you want to think that, but I know better. I always know better. But nobody believes me.”

“If you are such a good seer, why doesn’t anyone believe you?”

“It’s my curse!” She sat down heavily on the ground, forcing Odysseus to kneel next to her if he didn’t want to loom over her head. “I was a priestess of Apollo. I loved him, but as a woman loves a god, not as a woman loves a man. I became his priestess because then I wouldn’t have to marry. I never wanted the touch of a man, any man. Nor the comfort of a woman’s embrace, either. I thought—” She stopped for a moment, her voice choked with tears, but instead of breaking down weeping, she breathed deeply, and spoke again. “He came to me. He wanted to be my lover. He said he’d make me the greatest seer ever. I told him no. I never wanted a lover. I wanted him to be my god, my sun, not… not just another man. I thought he would understand if I told him.” She swallowed. “He didn’t. He cursed me. Gave me this gift of sight… and told me that nobody would believe me, that no matter what I saw, no matter how important, no matter how reasonable or how easy to check, nobody would believe me.”

“Isn’t it true that men cannot escape their fate anyway? Why would it matter that nobody would believe you, if it couldn’t change anyway?”

“But it can! I tested it, when it was a thing that affected me alone. I saw that I would be walking by the cliffs one day, and turn my ankle. I didn’t go to the cliffs that day… and I didn’t turn my ankle.”

“Perhaps the vision was meant for a different day.”

“I’ve been to the cliffs since then. I’ve never turned my ankle.”

“Well, perhaps that was a mere dream of ivory. They must come sometimes even to seers.”

“I don’t dream my visions… I see them. While I’m awake. My dreams are nonsense like anyone else’s. My father is a frog but still rules. I have a sister that in reality I’ve never had. I can fly through the air like a bird. None of those things come true. But when I’m awake… when I’m awake, I see what will come. I see it in full clarity as if it’s a play I’m watching on a stage, but also real life. No cranes, no chorus, no makeshift tapestry backdrops. It’s real and I am seeing it, but if I am in the vision, I’m watching myself on the stage. When I see my death, I don’t see the knives coming at me. I see Cassandra, surrounded by her killers, and I watch the blade pierce her breast. And I see things I cannot be there for. Such as Clytemnestra’s fate, after she kills me. And yours.”

“And what is my fate, then?” he asked, still humoring the madwoman.

She laughed again. “Why would I tell you? You wouldn’t believe me – nobody believes me – but even if you would, why would I help you? It was your accursed plan to gain entrance through our gates with that horrible horse statue. We should have burned it as an offering to the gods, with all of you inside.” She looked down. “I tried. I thought, if I can only smash enough of it that my father or brothers or anyone could see the Greeks inside, this time surely I could save us. They wouldn’t have to believe me, only their own eyes. So I ran at you with a heavy stone and smashed at your statue as hard as I could. But everyone thinks I’m mad. So the guards stopped me and dragged me away, and I lost my last chance to save us from our fate, because I am thought a madwoman and nobody believes me.”

And that made Odysseus’ blood run cold. Because that had happened. He’d been there. He’d heard the muffled sounds of a girl’s screaming outside the horse, felt the shocks from her unexpectedly powerful blows against the wood. Several more minutes and she might actually have broken a hole. He remembered whispering to the men, counseling patience, because the Trojans hadn’t pulled them through the gates yet. He’d wondered why a Trojan girl was attacking, when she couldn’t possibly know they lurked inside.

How could she have known, unless she was telling the truth, and she saw the future?

“Hmm.” He turned away from her for a moment, pondering.

Behind him she said, “I told my mother and father not to embrace Paris back into family, for he’d bring about our ruin. They didn’t believe me. I told Paris not to raid Sparta for Helen, regardless of what Aphrodite had promised him. He didn’t believe me. I said over and over that we must return Helen to her husband, for her being here would be our doom. Nobody believed me. That’s my curse; nobody will believe me, no matter what I say.”

Odysseus turned around, having made his decision. “Well, you’re in luck, noble lady, for that’s my name! Nobody!”

Cassandra blinked. “What?”

“Yes, I am Nobody, son of Nobody, hailing from the proud country of Noland! It’s been my honor to serve as an advisor to Odysseus, the wise king of Ithaca, and since he has heard that you are cursed such that Nobody would believe you, and none other, he’s sent me to ask your counsel!”

“This is stupid,” Cassandra said flatly. “The curse of Apollo won’t be ended by some foolish wordplay! I know well who you are, Odysseus.”

“Oh, no, many men have said I resemble Odysseus, but really I’m just Nobody,” Nobody said. “Now what was this about a doom for Odysseus?”

Cassandra laughed. “Oh no. Even if it would work, I still hate you. Or Odysseus. Whichever. I’ll tell you nothing of his fate. But I’ll tell you again of mine! Your cursed horse—”

“Not mine, my lady, but my King’s idea. Because I’m not Odysseus. I’m Nobody.”

“Odysseus’ cursed horse brought about the doom of my nation. And because of that, my sister Polyxena will be murdered, sacrificed to the dead warrior Achilles, who already claimed my brother and treated his corpse most cruelly. My nephew, Hector’s only son Astyanax, will be thrown from the ramparts and killed, because Odysseus advises that the son of a hero who opposed the Greeks cannot be allowed to grow up. And I will be given to Agamemnon as his prize of war, and when he brings me back to his halls in Mycenae, soldiers belonging to his wife’s lover will slaughter me, and him, and I will never need endure his touch again.”

Agamemnon had sacrificed his own eldest daughter Iphigenia for favorable winds so the Greeks could reach Troy, ten years ago. Clytemnestra had screamed at him, and raged, and pleaded to spare her daughter’s life, and in the end had turned from Agamemnon coldly and offered him no words of encouragement when they departed. Couldn’t a woman, enraged over the death of her daughter, stew in that rage for the years her husband wasn’t there? Couldn’t she take a lover as revenge, to betray the man who killed her child? Couldn’t that lover fan the flames of her desire for vengeance, persuade her to allow her husband to be killed?

Odysseus – and, by extension, Nobody – knew Clytemnestra well enough to know that yes. Yes, such a thing was possible. Clytemnestra was proud, and headstrong, and her anger burned slow and long. Ten years to think on the fact that instead of grandchildren frolicking at her feet, she had nothing of Iphigenia but a cold grave, because her husband had valued his promise to his brother Menelaus more than he’d valued his flesh and blood child.

“I believe you,” Nobody said slowly. “That… Odysseus would not hear it, but I, Nobody, understand that Clytemnestra was driven to rage right before we left, because Agamemnon sacrificed her daughter to appease the rage of Artemis. Yes, she might be planning to kill him.” He took a deep breath. “Does my believing you change anything?”

“Of course not. Agamemnon would also have to believe you, and he would not.”

“Then what if I arranged for Odysseus to take you instead, to be the sworn priestess of Athena at the great temple dedicated to her in Ithaca? Never to be touched again by a man? Would that change anything?”

Cassandra snorted. “If you could persuade Agamemnon to let me go, which is unlikely, I would not die, not that way, but he still would. It changes nothing of his fate.”

“And if Odysseus told him what his wife was plotting?”

“He won’t believe you—”

“Of course, not me, I’m Nobody. But if Odysseus said it—”

“He won’t believe Odysseus. He thinks his wife is his possession, cowed and in his control. He will never choose to believe she would harm him until it’s too late.”

That was unfortunately very much in character for Agamemnon, who’d also refused to believe that he had to yield his prize because she was the daughter of a priest of Apollo, and who’d refused to believe that his act in taking away Achilles’ woman instead would drive Achilles to rage and leave him to all but abandon the Greeks in battle, almost leading them to defeat. And who’d refused to believe that Ajax had raped a woman in the temple of Athena, despite that being entirely in character for Ajax, who boasted that he made his own fate and did not fear the gods.

“Well, if he cannot be swayed by Odysseus, then neither Odysseus nor any other man can save him. But you could be saved. If Odysseus did that – spared you Agamemnon’s bed and the blades that come for him, made you a priestess of Athena and ensured that none would touch you – would you be willing to tell me the doom you’ve seen for him?”

“No.”

“No?”

“I am not that selfish,” Cassandra said. “My sister Polyxena will still be murdered to appease the shade of my brother’s killer. My nephew will still have his little body broken and his life ended almost before it has begun, because Odysseus will advise thus. Why would I do anything to help him?”

Odysseus had, in fact, been planning to advise the death of Astyanax. The son of a hero that the Greeks had killed might grow to be a great warrior who sought revenge on his father’s killers, and while Achilles himself was dead, all the Greek cities had participated in the siege of Troy. It was safest for the boy to die.

But Odysseus was first and foremost loyal to his own men, the Ithacans he’d brought here to fight by his side, under his direction. They looked to him as their leader; he would sacrifice one to save the rest, if needed, but he was not willing to sacrifice them all to stop a nebulous potential threat that would probably fall on Menelaus, if it fell on anyone. And what Cassandra had said was that Odysseus would watch all the men who trusted him as their ruler die. Odysseus hadn’t believed it for a moment… but Nobody did. He needed to know how to evade that fate.

“What if. Hear me out. What if Polyxena did not die, nor Astyanax either? Nor you?”

“I hardly care for myself. But… if Odysseus would spare Astyanax, and find a way to save Polyxena… perhaps. Yes. If he did those things and I had proof he had done them, I would tell him of his doom.”

“Not him, my lady, he wouldn’t believe you. You’d have to tell me, Nobody, because Nobody believes you when you speak.”

Cassandra laughed. It was still bitter. “Oh, why not? I hardly think this trick will fool Apollo, so this won’t last, but why not? Save Polyxena and Astyanax, and I will tell you what Odysseus must do to save himself.”

“Apollo is the god of clarity and vision, as much as he is the god of the Sun; that’s why he can grant seers the ability to prophesy. When he spoke your doom, did he truly say ‘nobody will believe you’? Were those his words, exactly?”

“It’s been years… but yes. I remember it as if it happened yesterday. Those were his exact words.”

“Well. If the noble and deathless Apollo speaks using particular words, he means exactly as he says. God of clarity, remember. I think he was angered by your rejection, but part of him still loved his priestess enough to leave a loophole, if only you had the logic to see it. Which, obviously, you didn’t, and who could blame you, with all the stress of the war? But if he spoke those words – ‘nobody will believe you’ – then that is what he meant. And because I am Nobody, I believe you!” He bowed to her. “I will advise the great and noble Odysseus that he must do those things to avoid the doom you have seen.”

“Don’t tell him it came from me, Cassandra, or by the terms of the curse, he won’t believe you either.”

“I’m not sure it works that way, but I will take the precaution. And lady, if you should tell Odysseus something and he doesn’t believe you, just remind him to have his advisor Nobody talk to you. I’m sure that just asking him to ask me won’t trigger the curse.”

***

“My friends, I have had a most terrible dream,” Odysseus said to the council of the leaders of the Greek army, the same ones who had refused to act against Ajax for defiling Athena’s temple. “I am certain that it came through the gate of horn.”

Agamemnon wiped his brow with an expression of impatience. “Is this yet more agitating for Ajax’s death?”

“Not his death, necessarily, but a solution to our problem,” Odysseus said. “I dreamed of a dog, tearing a hare from its hole and savaging it. But even as it devoured the hare, a great eagle stooped and caught the dog in its talons, taking it as prey.”

“Let me guess,” Agamemnon said. “The dog is Ajax.”

“No, my lord, I fear the dog is all of us. For I also dreamed of Athena, and her grey eyes were thunderclouds, a storm in them that could tear a sailing ship apart. Her wrath will fall upon us if we do nothing… but I had another dream, more hopeful.”

“Another dream, more hopeful? That sounds promising,” Menelaus said. He sounded very, very tired. The war had aged him far more than ten years. “We could all use some hope.”

“I saw a hunter come upon a lamb. It was obvious that he intended to kill and eat it… but then he relented, and brought the lamb to a safe paddock. Then he returned to the place where he would have made camp and eaten, if he had slaughtered the lamb… and found a tree had fallen on the spot. His act of mercy spared his life.” Odysseus spread his hands. “I know, my friends, that no one here wants to execute our comrade, and we all fear that we would be earning Athena’s wrath by doing exactly what he did, since he has taken shelter in her temple. But I believe there is another way to save ourselves from Athena’s rage. Let me take Cassandra to Ithaca, to be a priestess at the shrine of Athena there, which is the most glorious and well-favored of all the temples to the gods in Ithaca. Spare her the fate of being any man’s possession, as she begged, and let her spend her days in glorifying great Athena.”

Agamemnon scowled. “The best temple in Ithaca is still a hut of mud and sticks next to the least shrine in Mycenae. I should take her to Mycenae to serve in Athena’s temple, if that is the best way to save ourselves from Athena’s wrath.”

Odysseus smiled jovially. “Oh, noble son of Atreus, we know that your love for the beautiful Cassandra would tempt you past what mortal man can bear, were it your task to bring her untouched by man to Athena’s temple in wealthy Argos. Whereas I…” He sighed. “I am heartsick with longing for faraway Ithaca, and no Trojan prize, however beautiful, can compare in my mind to the beauty of my wife Penelope. If it will calm Athena’s wrath I will gladly leave the woman untouched by the hand of any man until she is safely delivered to the temple in Ithaca. And, I will remind you, great and noble king, that the gods are as jealous as they are powerful and deathless. Athena’s temple in Mycenae is truly glorious, there is no doubt, but you gave all the gods equal due in that well-favored land. The temple of Zeus himself is greater than the temple of Athena, in the city of Argos... as is normal. But in Ithaca… well, I’ll admit, I play favorites. Athena’s temple in Ithaca is greater than any other gods’ temple there, and when I am safely home I will make it greater still, to offer thanks… and immortal Athena appreciates being honored above the other gods.”

The other men around the council fire smiled or chuckled, except for Menelaus, who seemed to have lost all ability to feel humor or happiness in his exhaustion. The fact was that this long war had been fought to recover his wife, and now that he had her back, he seemed to regret asking so many men to risk their lives, and drawing so many to their deaths, as if he no longer thought she was worth the sacrifice. He’d never said so aloud, but Odysseus could read men fairly well.

“This is the second time I have had my prize torn from me by the edict of the gods, as brought to me by the mouths of men,” Agamemnon said angrily. “If I give Cassandra over to you, Odysseus son of Laertes, what recompense will you give me? What prize worthy of a king do you offer instead?”

“Andromache,” Odysseus said promptly. “The wife of the great warrior Hector, who brought so many of our comrades to their end. I think she may even serve better than Cassandra; Cassandra, after all, is the daughter of a king, but Andromache was chosen by that king to be the wife of his beloved son and heir. Priam, who brought his city to grief by being overly indulgent to his sons… how can we imagine he would have chosen any but the best for his oldest, mother of his future heirs? Andromache should be a prize fit for a king… and better yet, is not a madwoman.” He grinned at that.

Nestor cleared his throat. “Speaking of that, have you considered my words regarding the fate of Hector’s son?”

Odysseus did not allow his irritation to show, though the words in question had not been Nestor’s. Nestor had agreed with Odysseus as to what they probably should do, but Odysseus had wanted to consult an augur first. Well, he had. “Yes, I have, but I’ve changed my mind.” He paced, talking with his hands. “I thought at first that we must kill the little boy, for the son of such a great warrior would be a fearsome foe if he grew to adulthood and sought revenge. But I considered then. If a ewe dies abirthing, and the new lamb is placed with a different ewe right away, the ewe who suckles the lamb is the one the lamb looks to as a mother. But if the mother dies a few days after birth, the lamb knows who its mother was, and cannot be convinced otherwise. The boy, Astyanax, is yet very young. If he’s taken from his mother and raised by an Achaean, he will never know who his true father was… and if he’s treated well, by a father who truly raises him as his own, he will not turn on that man even if he learns the truth in adulthood.”

“But why complicate matters so?” Nestor asked. “It seems to me that any man who takes such a child in is tempting the Fates.”

“Why? Because so many good men, the flower of our nation, have been cut down in their prime, many before they had opportunity to father sons. The son of a great warrior will grow to be a great warrior himself, but rather than fear that warrior, let us take him in and make of him one of us. If no one else wishes to do it, I’ll take the boy to be a brother and companion to my own Telemachus, who will be ten now, a good age to have a baby brother.”

“It seems risky,” Idomeneus said.

Odysseus shrugged. “We were not foes with the Trojans because they were our fated enemies, sworn to hate us for all eternity. They, like we, were naught but toys in the hands of the gods. Were there some dire fate predicted, some prophecy that this boy will kill Achaeans, I would think differently, but my only reason to fear his growth to adulthood was logic… and upon further thought, logic tells me that my original plan was a waste.”

“You can’t take both the boy and his aunt if that’s your goal,” Agamemnon complained. “She will tell him of his father’s deeds when he’s young enough that it would matter.”

“She will not,” Odysseus said mildly, “because she will be sworn to the temple of Athena, a priestess with no contact with men or boys save in the course of her duties.”

“Who then should take Polyxena?” another man asked.

“None other than Achilles’ own son, Neoptolemus,” Odysseus said. “She was used to lure his father to his death; let the son take the woman who falsely promised herself to his father. Let her give Achilles grandsons, to pour libations for him and carry his blood onward.” Cassandra had said that Polyxena would be sacrificed to Achilles, to quiet his spirit. Achilles would not, he hoped, demand the sacrifice of the woman who’d been gifted to his own son. “We will sacrifice to Achilles and honor him before we leave, that his shade will remember us as comrades in arms and think kindly of us, since in all of the chaos of the end of the siege, I believe we never actually did that.”

Most of the men looked uncomfortable or guilty. Nestor said, “I agree. I was just saying that the other day, that of all our comrades fallen in battle, it’s a shame that the greatest of them, Achilles, has not had a true funeral. We performed the rites over his body, but we sacrificed no beasts, and poured only the most meager of libations. We should do this right away.”

“What of Hecuba, Priam’s wife?” someone asked.

Odysseus had originally planned to take that woman home, to be a servant to Penelope. He had no interest in taking a woman for his bed, so he had thought the age and dignity of the old queen was better suited to his intentions than to others. But he could not possibly take her when her daughter and grandson were both coming with him. “I suppose anyone who wants an elderly woman as a slave can take her; she’s too old to be gotten with child and likely not anyone’s preference for a bedmate when there are so many young and beautiful women in Troy.”

“I will take her,” Nestor said. “I had not planned to take any of the women – I would never wish to raise the ire of my wife!” He chuckled. “Truly she is more beautiful than any of these anyway. But you are entirely right, wise Odysseus, and I had been thinking the same thing – she has run a household, so she might make an excellent slave to give to my wife, and my wife will never accuse me of bedding such an old woman, as she might if I took home a young and beautiful slave to gift to her.”

And so the council continued to talk into the night, dividing the spoils of war.

***

“What have you done?” Cassandra snarled at Odysseus.

“You’re welcome,” Odysseus said in a tone of exaggerated graciousness. “Polyxena, Astyanax and you will all live.”

“But Andromache will die!”

Odysseus shrugged. “I’m sorry for that, but I needed to offer someone to Agamemnon. And for me to save Astyanax, and it to be safe from what I feared when I thought to kill him, it’s better that he have no living parents of blood.”

“And you gave Polyxena to a man who hates her and thinks she betrayed his father to die!”

“She did do that, after all.”

“Because we were at war!”

“I am no deathless god or miracle worker, Cassandra. I am not a son of a god either, and I have no powers to command men other than those given to me by my birth position and my own quick wit. The only way to save Polyxena from being given as tribute to Achilles’s shade was to give her to his son; I cannot even be certain that will work—”

“It will,” Cassandra said sullenly.

Odysseus thought her level of certainty was absurd. “Perhaps, but perhaps not. Regardless, it was the only strategy I could think of that had any chance. And I could not pry you free from Agamemnon without offering him a woman equal in value.”

“Why?” Cassandra asked bitterly. “We women did nothing to you – Helen, yes, she betrayed her husband, and one could argue my mother had fault for letting her stay. But none of the rest of us had any power at all. Why is it the way of the world that men make war, and then take the women of the army they defeated, as if we were gems or gold? We did not kill your comrades, we did not steal Helen away. Our men did those things. Why are we punished for the acts of people we have no control over?”

“That’s… just the way of it. That’s how the gods decreed this world to be.”

“It doesn’t need to be,” Cassandra said. “I have seen… I have seen hazy visions, as if a ship coming up the horizon, that I can barely see or understand… of a world where warriors who win do not take captives of the enemy’s women. Where women are allowed to own things, and are not themselves owned. Where women fight by men’s side in war, and are considered their equals.”

“I can’t imagine how any of that could possibly come to pass,” Odysseus said shortly. “Women are weaker than men, and are burdened by child-bearing. Some women, perhaps, like the Amazons, but women in general? How could women ever be equal to men?”

“You’re not Nobody,” Cassandra said. “Of course you can’t believe in anything I see.”

“A good point,” Odysseus said. “I’ll take my leave of you then, daughter of Priam.”

He ducked out of the tent Cassandra was being held in, and came right back in. “A good day to you, Cassandra of Troy! I’m Nobody, sent by Odysseus the king of Ithaca to ask for your counsel!”

“This is still ridiculous,” Cassandra said, but there was a note in her voice that belied her words. Longing, perhaps.

“If it’s ridiculous, but it works, it’s not ridiculous,” Nobody said. “Now tell me, since you’re so concerned for the fate of your sister-in-law… how can Agamemnon escape his fate?”

“He can’t,” Cassandra said shortly.

“There is no way at all?”

“He won’t believe you if you tell him Clytemnestra will betray him. In fact it will make him trust in her the more, to spite you.”

“Ah. But what if I told him, not that Clytemnestra was unfaithful or would betray him, but that I have had word of a man taking advantage of her hospitality, who might be planning to harm him?”

“Aegisthus,” Cassandra said. “That is his name.”

Aegisthus! Well, that explained everything. Aegisthus had been Agamemnon’s rival for the throne for almost Agamemnon’s entire life. “Ah! I can tell him Aegisthus has been sniffing around and may have suborned some of his men. Then he may take the appropriate precautions!”

“It still won’t work. Agamemnon will be wary of his guards and soldiers, those who didn’t accompany him here, but he won’t suspect Clytemnestra, and she will deliver the death blow herself if she must.”

“Hmm.” Nobody pondered this.

“Why do you care? Agamemnon is arrogant and he murdered his own daughter; why try to save his life?”

Nobody sighed. “I, Nobody, don’t particularly care, but Odysseus does, for he swore an oath to support Agamemnon. And you were not there at the sacrifice of Iphigenia. You didn’t hear him weep, or beg Calchas for another way. He did not sacrifice her casually; it was only the oath he’d sworn to his brother and the oath we’d all sworn to support the husband of Helen. Should he have forsworn himself? How could a man hold any honor if he can’t keep the oaths he promised?”

“How can a father hold any honor if he kills his daughter for favorable wind? If he had been a good man, a good father, he wouldn’t have done it, and the ships would never have come, and eventually we’d have sent Helen back – she wanted to return home, but we were under siege because of her, and we knew of no safe way to return her. How many lives would have been saved had he not taken his daughter’s?”

“Most men can’t see the future. Calchas doesn’t usually see the future, in fact; he communes with the gods. He can tell which god we have offended and what they will demand as their apology, but he could not have seen that this war would last ten years, nor that Helen would have returned of her own accord eventually.” He sighed. “It doesn’t matter. You’re within your rights to hate Agamemnon, for leading the warriors that destroyed your city, but you bargained with Odysseus for the lives of your sister and your nephew, and they will live now, so you are bound to speak truthfully. What if I – or rather, Odysseus – were to privately warn some of Agamemnon’s most trusted men of the danger, and charge them to hold their tongues and say nothing to the son of Atreus, but to guard him from his own wife?”

Cassandra’s eyes grew distant. “It is… not likely that that will save him. At some point he will go to his wife’s bed, without his guards. But it is possible. If Aegisthus is captured and can be made to admit to his adultery with Clytemnestra, Agamemnon will no longer hold her in high regard, and he will imprison her. This would save Andromache, if it comes to pass that way.”

“There is more than one possible future?”

“Some things are fated by the gods and cannot be changed. Most things, though, come about from the choices of men, and those may change if different choices are made. If I try, I can see different pathways that may come to pass, and they look brighter and clearer if they are more likely. Agamemnon surviving is very dim, but it’s a possibility, if you do as you said.”

***

A word to some of Agamemnon’s most trusted men, since that was all he could do, and then Odysseus went to the tent where the rest of the women were, Cassandra having been kept separately for her madness. He told Hecuba, Polyxena and Andromache what had been decided, telling them that “a seer” – he didn’t mention that it was Cassandra – had traded information to the Achaeans in exchange for saving Polyxena and Astyanax from the fate the seer had foreseen. He didn’t care, he told himself, but Cassandra would be more tractable if she knew that her mother and sister had been allowed to know how much worse it would have been. Then he collected Astyanax from Andromache – who wept to lose him, but was grateful that he would be given a safe place to go where he would not grow up as a slave – and handed him over to a nurse they’d taken from Troy. Then he prepared to set sail. It was all in the hands of the gods now.

They set sail on a cloudless day, early in the morning, but by mid-afternoon the winds had come up, blowing in the wrong direction. It wasn’t a terrible danger or a tragedy; instead of heading straight across the sea to Ithaca, they were blown toward the island of the Cicones, people that had been allies of Troy during the war. They’d been able to give Troy only minimal assistance; they weren’t large or powerful. Odysseus smiled. An opportunity, then.

Cassandra came up onto the deck to talk to him. “My lord, son of Laertes, you must not do what you’re planning.”

“What I’m planning?” He scowled. “How would you know what I’m planning?”

“Because I can see it in your future!” she snapped at him. “You want to sack the town and take on supplies, and slaves, and prizes.”

“Anyone could have guessed that; it’s what a warship does,” Odysseus said, not quite able to not sneer at her.

“Well, you mustn’t. If you do, you will pay the price – many of your men will die.”

Odysseus snorted. “The Cicones have no army, and not much of a navy. But you’re a good daughter of Troy, aren’t you? They were your allies, so of course you want to sway me away from that course.”

Cassandra laughed, a hysteric note in it. “That’s not how it works! I must speak truth about my visions, else I’d have advised my family to do the exact opposite of what they should do, and the curse would have made them disbelieve my counsel and do what they should have anyway.”

“Of course,” Odysseus said, not even bothering to hide how much he didn’t believe her. “After what you went through and what you saw happen to others, I can guess well enough you have no stomach to see it again.”

“No!” She stomped her foot. “What would Nobody say about this?”

He was about to make a quip about how, generally, Nobody wasn’t much of a talker, when he remembered with a shock his ruse, playacting that his name was Nobody. The fact that he could have forgotten such a thing was frightening. Odysseus looked around the deck and found a hooded cloak, treated with beeswax and tar, that he or his men could use in a storm to keep the rain out of their eyes. He grabbed it and threw it on, and then bowed slightly. “You summoned me, daughter of Priam? I’m Nobody, son of Nobody, at your service!”

Cassandra took a deep breath. “This is still very strange.”

“If it’s strange, and it works, then it was wise as well as strange. What do you have to tell me, Nobody, the advisor of Odysseus?”

“You m – Odysseus mustn’t sack the Cicones. I see no glory or loot from such a venture, only blood, and much of it Odysseus’ men.”

“We have little choice about going to the Cicones’ island. The wind does as the gods will it. Tell me exactly what you see, and how this will end in blood.”

“You – Odysseus will tell his men to be quick, to loot the town, take captives, and divide the spoils fairly, but not to linger. But they’ll resist; Ithaca breeds stubborn men and many of Odysseus’ crew aren’t Ithacan at all, but were hired at some port or another. They will want to remain, to enjoy their spoils. And this will give the Cicones time to call on allies. The allies will come and attack, taking the men off guard. Most of the loot will have to be left behind, and I see the crew reduced by 1 in every 10 men, their blood watering the Cicones’ island.”

“Hmm. Time to get help, you say? What if, and I’m just sounding things out here, we killed them all, without mercy, so there was no one to raise an alarm?”

Cassandra sighed. “Is it not the greatest of hubris to make a plan that assumes that nothing will go wrong? Not one man, woman, or swift-footed child who knows how to ride will get away to call the Cicones’ allies to their side?”

“You have a point.” Nobody rubbed his beard where it itched against his chin. “But we have no choice but to go there. What if we go to trade instead of sacking the place?”

“You cannot lie to them and say you’re going to trade and then sack them anyway.”

“What would you take me for? There’s trickery and then there’s just deceit. If the Cicones gave us hospitality, thinking us traders, then what kind of people would we be if we betrayed that hospitality?”

“The kind of people who build a great gift for a city, and hide themselves within it so they can come out and sack the town?”

“We never told your people the horse was a gift, you know.” Nobody nodded slowly, a plan coming to his mind. “If they see us flying the flag we currently have, they may know our role in the war, and see us as enemies even if we claim to come in peace. All right! Thank you for your advice, my lady Cassandra.” He took off the cloak and called to his men. “Lower our flag, and raise one that says nothing of who we truly are! We will come to the Cicones as friends, seeking trade.”

“And then sack them?” one of his men, Eurylochus, asked.

Odysseus shook his head. “No, that would violate the laws of hospitality, held by gods and men. We will actually trade. The change in flag will keep them from knowing what side we fought on in the war. Let the other ships know.”

“And we are going to trade with them instead of sacking the town and taking what we want… why?”

Odysseus glared at him. “Because I, your captain and king, said so.” He saw other men listening, and thought it was best to not just leave it at that, as much as he wanted to. “I’ve had a dream of ill omens if we sack the place.”

“Not every ruler would place so much portent in a dream,” Eurylochus said. “It’s as if my lord Odysseus thinks that all dreams come through the gates of horn.”

“Oddly enough, I did have a dream that I am sure came from the gates of ivory, for in it, Eurylochus spoke wisely, and remembered his place as a sailor, not the equal of the captain.”

The other men laughed as Eurylochus scowled. “I came to be part of a band of soldiers, not a merchant ship,” he said.

“And we will be soldiers, again, if it’s needed, and when the omens are right. But to tell you the truth, I’d be just as happy if the winds took us straight to Ithaca from the Cicones’ island, and there was no need to raise a sword again before we were safely home. Did you not get your fill of war from ten long years of fighting?”

“War, yes, but if there are spoils to be had, I’d rather take them than trade for them.”

“So would we all! But we’d also like to not die pointlessly. I have intelligence that says the Cicones are better defended than we’d originally thought.”

Eurylochus grumbled, but settled down. He was Odysseus’ brother-in-law, husband to his beloved younger sister Ctimene, and he often spoke above his station as a result. Though he was a commoner, his family had enormous wealth in their lands, and had paid an extremely high price for Ctimene’s hand. This didn’t actually entitle him to the same rank as the King of Ithaca, or the captain of the fleet, but he often behaved as if he thought it did.

***

When they docked as traders, Cassandra came to Odysseus’ side again. “Don’t let all your men go ashore. Send only the calmest-tempered ones, the ones who can listen to insult and hold their tongue in response.”

Odysseus ignored her. He trusted his men, all brave soldiers who’d fought well at Troy, and he didn’t need a Trojan princess, a spoil of war really, telling him who he could send ashore and who he couldn’t. The men he chose to go ashore from the various ships were men who could handle themselves well in a fight, who wouldn’t be taken advantage of in a trade, and who he wanted to reward with some shore time for their bravery during the war.

He never found out exactly what happened. He was on the dock, chatting with the dockmaster and negotiating docking fees, when he saw smoke, and heard the sounds of fighting men’s shouting in the distance. While his first inclination was to run toward the problem and find out what was going on, as a captain his first action had to be to make sure the ships were ready to depart in a hurry, or fight back if that turned out to be necessary. So he turned and ran up the gangplank onto his main ship, to give orders, and ended up running straight into Cassandra.

“Odysseus, you have to leave now!” she said. “The men you sent out into the town got into a fight, and it’s spreading. If you don’t leave now, hundreds will die, far more than I first advised you about!”

“I don’t have time for this,” Odysseus said. “I have to –”

She interrupted him. He’d beaten people for less. “I need to talk to Nobody, now!”

He really didn’t have time for this. But every time he’d taken on the persona of Nobody, the things she said seemed wise and prescient. “Quickly,” he snapped. “Here I am, Nobody! You’ve got something to tell me?”

“You have to leave now. Save the men still aboard the ships. You’ll only lose the handful you sent into the town.”

“I can’t abandon m –” He coughed. “I mean, King Odysseus certainly can’t abandon his men so easily!”

“If you don’t, hundreds will die. You have sixty times twelve men on your twelve ships. Do you want to lose three ships’ worth of men? Or more? Take off now, and leave the ten men you sent to town behind, or wait, and lose far more.”

It went against everything he believed in to abandon his men… but Cassandra had foreseen the Trojan Horse trick. And Athena had sent him to her. And she’d advised Odysseus to send his calmest-tempered men, and he hadn’t listened, and now the men he’d sent had started something and imperiled the entire fleet.

“I’ll leave one ship to help them get out of here, and bring them back to join the rest of the fleet when they’re free.”

“It won’t help—”

“I have to try,” Odysseus said, and gave the orders.

Eleven ships left the harbor of the Cicones. The twelfth never reappeared, nor did the men on it, nor did the men left behind on shore.

Seventy men lost. If he hadn’t taken any of Cassandra’s advice, she claimed it would have been seventy-two. How many if he had listened to her and sent only his most level headed men? How many if he hadn’t listened to her at all and had stayed behind to save his men?

It was maddening, thinking about it, and he had no proof of any of it. But Athena had sent him to this woman, and the goddess had never played him false.

***

They set off on a heading toward Ithaca and were immediately blown off course again by a storm.

Nobody consulted Cassandra this time. “Row for the shore and we will eventually come through the storm,” she said. “We will come to an island, eventually, but the people are harmless. No one will be hurt as long as you aren’t violent toward them.” She looked up at him.

That was good enough for Nobody, who took off his cloak, resumed being Odysseus, and gave orders to pull the sails down and row for the nearest land.

They came within sight distance of Cythera, but were blown off course again. It took nine days before they reached the island Cassandra had spoken of. On the shore, they gathered fresh water and cooked some of the supplies, serving a meal to all the people on all the ships. It was the first time Cassandra had an opportunity to see her nephew.

When Odysseus picked three men to scout, Cassandra went to him. “Can I go with them?”

He scowled at her. “Why would you want that?”

“I know it’s safe,” Cassandra said, “and with your men escorting me, I could hardly run away. I haven’t been off the ships since we left Troy, and I am no natural-born sailor. I’d like to feel solid ground for a change.”

She wasn’t wrong; she was technically a slave, and his men wouldn’t allow her to escape. Odysseus sent a fourth man along with the group, to serve as Cassandra’s escort without interfering with the mission. “Don’t tarry with the people of the island, even if they’re friendly,” Odysseus said. “Especially if they’re friendly. If they offer us hospitality and want to trade, come back right away to let the rest of us know.”

And then he waited.

And waited.

Cassandra had said the island was safe, and had put her own life in danger if it was not. But was she really a seer? Maybe she was just a madwoman, as everyone thought, and she’d guessed at the role of the Trojan Horse because she was paranoid, like many madwomen. Maybe she’d warned him to trade with the Cicones because they’d been allies of Troy, like he’d originally thought, and warning him to send only his most even-tempered of men to go amongst former enemies? Now that he thought about it, that had been wise advice, and he’d have done well to follow it… but anyone could have had the wisdom to guess at such a thing. He himself might have chosen that if a slave woman telling him what to do hadn’t stung his pride. And then she’d told him to keep sailing on and that no one would die before they reached land, but false seers always told their hosts what they wanted to believe; it might have just been luck that it came true.

Could he really be sure his men were safe? Why were they taking so long, if the people here were as friendly as Cassandra had claimed?

He gathered a party of trusted men and went deeper into the island.

It was true, the people were friendly. And harmless. Perhaps too harmless. Most of them were lying around on the ground, or sitting leaning up against walls of stone huts in poor repair. They were barely dressed, both the men and the women, and much of what they were wearing were ragged. Some few were standing and walking, as far as a well to draw water, and then sat back down again. And they were all munching some sort of fruit, or flowers, or sometimes breathing in the air from burning stems.

“Come, friend!” one of the standing men said – slowly, drawlingly. “Have some lotus fruit!” He offered Odysseus a half-eaten fruit.

“No, thank you. We’re looking for my men. Did strangers come this way?”

“Maybe,” the man said. “That might have happened. I’m not sure.”

Eurylochus raised a hand as if to hit the man, but Odysseus held up his own hand. “Is there a leader among your people? A mayor, or a king, or a priest?”

The man seemed to think about it… and then never answered, wandering off with his lotus root as if he’d already forgotten the question.

There was a man cooking a fish on a brazier, on top of a fire that seemed to be made up of lotus stems. The smoke was sweet and dizzying, and Odysseus guided his companions away from it. The fish itself was the size of a child’s finger, and was already badly burnt. A nearly naked woman lay on the ground next to an anthill. She’d poked a stem into the anthill. The ants were busily climbing the stem, and she was lazily plucking them off the stem and eating them. Everyone else was either sleeping, breathing burning smoke, or chewing lotus fruits and flowers.

“Sir, I don’t like this place,” one of the men murmured to Odysseus.

“We’re only staying here long enough to find our men and my Trojan slave, and then we’ll get out of here. Don’t eat the food.”

“Eat what?” Eurylochus snorted. “The burned fish the size of my young son’s finger? The ants?”

“I meant the lotus fruits, but don’t eat those things either.” The men all chuckled.

A woman sitting on the ground offered them flowers. “Strangers! Come eat with us!” she said… slowly. This seemed to be a common thread.

“No, thank you. Did any strangers come this way?”

“Probably,” the woman said, and lost interest in them.

“What’s wrong with these people?” one of Odysseus’ men whispered.

“Those lotus plants.” He looked around, seeing the lotus plants everywhere. “They’re eating the flowers and fruits, and smoking the stems. And it looks as if almost nobody has done anything else in a long time.”

“This looks like it used to be a stone path,” Eurylochus said. “But it’s completely overgrown.”

“I think these lotus plants are like the grapes of Dionysius, but without the excitation that wine can sometimes bring. Only the slowing of the body, and the sleep it can bring.”

“Strangers! Friends!” a man leaning against a nearly ruined wooden building called. Slowly. “Have a lotus fruit!”

“The men of your country seem very eager to give us these fruits,” Odysseus said. “I am sure they’re delicious, but why so desperate to give them to us?”

“Because nothing is as sweet as this fruit,” the man said, swaying where he sat. “All of your cares and troubles will leave you if you take only a bite!”

“Maybe later,” Odysseus said. “Did you see any other strangers come this way? Four men and a woman?”

“Hmm… I think maybe,” the man said. “I might have seen them go past me. I thought it happened earlier in the day, but it’s hard to remember.”

“Well, if they came this way, which way would they have gone?”

“Probably that way,” the man said, pointing down the remains of the only street leading away from here.

Odysseus and his men walked along the street as it turned into nothing but a grass-covered path, and stopped at a well. Cassandra and the four men from the ship were sitting on the ground, eating lotus fruits, along with three women and two men of the island’s people. They weren’t barbarians; they spoke Greek and their clothing, what was left of it, used the same sort of textiles the Trojans and the Greeks both used.

“Captain!” one of the men said, slowly. “Try this. It’s wonderful!” He offered Odysseus a lotus fruit.

Cassandra smiled beatifically. “I don’t know what will happen. I don’t know. I don’t care either.” She giggled like a girl-child.

“Get up,” Odysseus ordered her.

The male slave laughed. “Get up, he says! Why?” All of the group on the ground laughed, including Cassandra.

Odysseus grabbed the nearest man’s arm and dragged him to his feet. The man didn’t resist, but he didn’t help either; he was deadweight. The others on the ground chuckled.

He turned to the men who’d come with him. “Pick them up and carry them,” he ordered.

The men who’d been eating the lotus wailed like babies and tried to get free as soon as they realized they were being carried away from their precious fruits. Cassandra screamed and kicked. “I won’t go back, I won’t go back to it!” she howled, like a Maenad, trying to claw at Odysseus’ eyes. Her screams mingled with the lotus-eating men’s cries of “No!” and “Leave us, we want to stay!” and “Let me go back!”

Eventually, with great effort, Odysseus and his companions managed to wrestle the four men and the woman onto the ship, and they heaved off. Cassandra had by now stopped screaming, and had gone completely silent. The slave man was quieter also, weeping softly to himself. But the three sailors who had gone to the lotus-eaters’ island were still shrieking and begging to be allowed to return as the ship sailed away from the island. Odysseus gave orders to have them confined below decks, along with the male slave, and to have Cassandra locked into the hold, where they kept the riches they’d looted from Troy and their supplies.

***

He opened the door to the hold, thinking to himself, I’m Nobody.

“So tell me, my lady,” he said as sarcastically as he could manage. “There’s no danger, you said? How is it you didn’t foresee the dangers of eating the fruits of the lotus?”

“Was anyone hurt or killed?”

“Answer me!” he snapped.

“Who am I speaking to?”

He sighed. “I am Nobody, son of Nobody, advisor to King Odysseus,” he said.

“I knew what would happen if we went to the island of the lotus eaters,” she said. “And I knew we would all safely return from there, and no one would be harmed. Aside from the pain of having to live in the world again, when for a while there we were able to forget.”

“So you did this on purpose? Because you wanted to eat the lotus fruit?”

“Is that so hard to imagine, Nobody son of Nobody? My father and brothers are all dead. My city has fallen. My sister in law is doomed to die in my place. I am an exile traveling to an unknown future. Can you blame me for wanting to forget, for a little while?”

“I suppose I do,” he said tiredly. “But it’s the wrong answer, to try to forget. The gods have given us this life to live. They say the dead don’t remember their lives, as they exist in the land of shades. Forgetting our cares and woes for a short time… that’s a gift given to mankind by Dionysus, or it’s the peace of sleep. But the people on that island had nearly given up their humanity and become animals. That kind of forgetting is very much like death.”

“Perhaps sometimes it might be better to be dead,” Cassandra said softly.

“That was an option and you rejected it. According to you, anyway.”

“I suppose I did.”

“You understand that your nephew travels with us, correct? That he is hostage for your behavior?”

“I wasn’t trying to run away,” she said, looking down. “I knew you would take me back. I just… wanted to forget for a little while.”

He sighed. “Don’t tell me that nothing bad will happen if something bad will happen, even if you’re sure it will all work out in the end.”

“How will I know if you consider it to be something bad? The lotus was so beautiful.”

“I think you know perfectly well that Odysseus would never have considered the loss of his men a good thing, and that ‘but we got them back just fine’ does not make it better.”

“It won’t happen again,” she said.

“Good,” he said, and turned on his heel.

Before he could reach the door, she said, “But I know that Odysseus is too wise to give up an advantage. Now that he’s considered the merits of taking Hector’s son as a younger brother to his own son, and adding the blood of such a great warrior to Ithaca, I know he won’t give up his plan for whatever I do. It is only my own life I risk when I defy him.”

“Odysseus is too wise to give up such an advantage,” he said. “But I’m Nobody. So give me good counsel, that I may take to Odysseus, or perhaps you will not be the only one that suffers for it.”

***

They hadn’t really had a chance to re-supply at the island of the lotus eaters; Odysseus hadn’t been willing to take the risk of losing additional men to the lotus fruit. It was still necessary to get supplies.

They came near a pair of islands. Cassandra gave a warning. “This is where your true suffering begins, Odysseus of Ithaca. If you love your life and the lives of your men, you won’t go near these islands.”

As condescendingly as he could, Odysseus said, “Pray tell, do your visions tell you where the men are supposed to be getting food and fresh water from, then? Because the last time I checked, we mortal humans need such things to live, and we’re running out.”

“At least do not go to the larger island,” Cassandra pleaded.

“I would think there would be more likely to be men with trade goods, willing to barter with us, there.”

“Can I please speak to Nobody?”

Odysseus sighed. “This charade is getting ridiculous,” he said, but with bad grace, “Fine. I’m Nobody. What do you have to tell me?”

“These islands are the beginning of yo – I mean, Odysseus’ doom,” she said. “You can go to the smaller island to resupply if you must, but as you love life, do not go to the larger island, or let any of your men go there. On that island lives a monster, and he will devour men who go to that island, with no respect for the laws of the gods or any rules of hospitality.”

“What’s on the smaller island?”

“Goats.” When he asked her to elaborate, she replied, “That’s all. Goats.”

“Well, goats can’t live off salt water, so there must be fresh water on that island as well. And if there are goats to eat, and fresh water, we can restock our supplies well. If there is nothing on that island but goats, then there are no monsters, or men who may war with us. So it sounds as if the smaller island will do perfectly well for our needs, and we have no reason to go to the larger island.”

Cassandra sighed. “Thank you, King Odysseus.”

“Oh, no, did you forget? I’m not Odysseus, I’m just Nobody.”

***

The land was good, and rich. Tall trees abounded, and there was no evidence of man’s activities, yet the underbrush was well-trimmed enough by the goats that it was not difficult to move about there. It occurred to Odysseus to wonder why such an abundant land was untilled, untouched by man. In the distance he could see the smoke from cook-fires on the island Cassandra had said was the home of a monster. Would a monster have cook-fires? On the other hand, men with cook-fires would definitely build boats and come across the strait to this land, to develop it, whereas perhaps monsters would not. Prometheus had gifted fire to man, not monsters, but that was no reason to assume monsters couldn’t copy the practice.

The gods gave them good hunting. Ten of his eleven ships got nine goats each, and his ship hunted ten. There were rivers inland, just deep enough to get all of the water restocked. Unfortunately they were running very low on wine; he’d planned to stock up at the Cicones’ island. Fresh water from a running river was generally wholesome enough, unless it was running through a city; Odysseus had learned that well while camping and exploring in Ithaca during his boyhood. But no one wanted to drink water if wine was available.

His crew’s spirits were raised by the delicious goats, spitted and cooked slowly over fires, seasoned with wild-growing greens they found and figs they could climb to reach. Surprising that the goats hadn’t gotten those treetop-dwelling figs, but then, there was so much for goats to eat on the ground that perhaps none had been driven to such measures. Goats could climb trees, but probably preferred not to. They’d certainly taken all the lower-hanging figs.

But everyone was palpably disappointed when he told them they must drink fresh water from the river at their feast, not wine. “Our supplies of wine are still exceedingly low, and there’s no sign of men living on this island who might grow and press grapes. Wine doesn’t make itself without man’s help. So we can dry meat for our stores and collect greens and figs and whatever else we can find, but until we find men to trade with, we must save our stores of wine for our voyage, and drink only water now.”

Eurylochus snorted. “We can plainly see the smoke of cookfires across the strait. Why don’t we sail over there and trade with the men of that island? They must have wine.”

“No men live there, only monsters.”

“How do you know that? Your wisdom is well known, Odysseus, but you have never been to that island any more than any of us have.”

“I have intelligence from a source I trust.”

Eurylochus threw the goat leg bone he was gnawing on to the ground, hard. “A source you trust? We know what that source is! Your bed-slave, the princess of Troy, speaks sweet nonsense into your ears, and you take her for an authority!”

“Firstly, Eurylochus, mind your tongue. You may be my brother-in-law, but that does not give you leave to speak to your captain in such a way. Secondly, she’s not my bed-slave. We’re bringing her to be a priestess at Athena’s temple, to calm noble Athena’s wrath at how Ajax treated this woman inside Athena’s own shrine. If I or any other man touched her, it would bring Athena’s wrath down upon us all.”

“I respectfully point out, my Captain and King, that you have not denied that you take that woman’s advice.”

“No. I don’t deny it.” Odysseus tossed his own goat legbone into the fire, having gotten all the edible meat off of it.

“What great ships has she sailed on? What fabled journeys has she undertaken, to know so much about the lands so far from her home?”

“I was advised by Athena herself to take this woman’s counsel. Perhaps you think it wise to disregard the direct advice of one of the immortal gods, but I do not. She tells me that that island is full of monsters, not men, and that if we go there, we bring a doom upon us.”

“But you have no evidence of this. Meanwhile, we see cooking fires! Tell me, which monsters cook their food upon fires, just like men?”

“The kind that are men, but have no respect for the gods,” Odysseus said. “If a man should fall upon his guest and murder him, without regard to any rules of hospitality, we could call that man a monster whether or not he cooks his meat on a fire. And that man is one we don’t want to trade with, no matter how much wine he has.”

“You don’t actually have proof of that either,” Eurylochus said. “Only the word of a slave girl.”

It hardly had the same impact, to throw down his goblet on the ground, when it was full of water rather than wine, but it was the symbol that counted. Odysseus stood up quickly. “Eurylochus! I have spoken, and I am both your king and your captain. Regardless of whether you approve of my decision or not, you will obey me. No one is traveling to the island across the strait, do you understand me?”

“I understand,” Eurylochus said after entirely too long a hesitation for Odysseus’ liking.

By the gods, he’d have that man flogged if he wasn’t Ctimene’s husband.

***

Odysseus woke to the rosy fingers of Dawn touching his face, as he and his men had bedded down on the island’s eastern shore rather than spend another night on the ship if they didn’t have to. He performed his morning ablutions, grabbed a charred goat thigh from the pile where he and his men had left the less delicious pieces, and tore the meat from it with his teeth, for breakfast. And then, as he walked among his men making sure they were all rising, he realized that he was missing some.

“Where is Eurylochus?” he asked, dreading the answer.

No one knew. But one of the eleven ships was missing, and enough men to crew it.

“Gods take that lout!” he shouted. “How dare he not only defy my command, but take one of my ships and its crew to do it?”

He immediately sought out Cassandra. “Eurylochus, my brother in law, took one of my ships across the strait, to the island you said would be our doom.”

“He is dead,” Cassandra said. “They are all dead.”

Odysseus glared at her. “They are dead now, or they’re dead in some future doom you claim to see for them?”

“I cannot see the past. The fact that I can still see their death means it’s ahead of them. But it must be. There is no path where you can save them and still avoid the doom that will destroy us all.”

“That can’t be true,” Odysseus snapped. “There must be some way.”

“Not for Odysseus, King of Ithaca. If you set foot on that island, you will bring about your doom.”

“I don’t believe that!”

“Of course you don’t. Nobody believes me.”

That brought him up short. “All right, then.” He turned away from her, and then back. “Well then, my lady, I’m Nobody. What can you tell me?”

“Only the same I told Odysseus. Those men are doomed. Any effort Odysseus makes to save them will kill us all. The moment Odysseus sets foot on that island, our destruction is set in motion.”

“Can anything be done?”

“There is – it’s so hard to see, it’s so unlikely – but. There is one path, maybe.”

“What do we need to do?”

“Nobody can save them.”

He opened his mouth to protest that she’d just said there was one path, and then remembered who he was, and stopped. “How?”

Cassandra stared him in the face. “I shouldn’t tell you,” she said. “I don’t trust Odysseus. His pride will be our downfall. I don’t overly care about my own life, anymore, but I don’t want my nephew to die for Odysseus’ pride. You should sail away and leave those men behind. Lose a ship, lose some men… better that than to lose all of them.”

“I give my word that your instructions will be followed to the letter. Despite Odysseus’ pride.”

“Odysseus cannot set foot on that island. Nor can anyone say he ever has, until he once more sets foot on his homeland of Ithaca. Do you understand? Nobody can save those men, most of them at least, but Odysseus cannot. And cannot ever be said to have.”

Nobody nodded, slowly. “I think I understand.”

***

“We don’t know what we will be getting into,” Odysseus told the crew of his own ship. “We’re told there are monsters over there, and that some of our men may already be dead. But we won’t abandon any man of Ithaca as long as there is some chance of his survival. So we will sail over there, and then I want only volunteers to come with me onto the shore to try to find our men, and rescue them if need be. Only the strongest, cleverest and bravest should volunteer.” He knew perfectly well that would leave him with no shortage of volunteers, despite the men’s natural fear of an unknown monster.

It didn’t take long. They saw the missing ship tied up right at the edge of the land, near a clearly visible cave high up on a cliff. Someone had built a fence of deep-set stones, and pine and oak trees, around the cave, to box in several herds of sheep and goats. The cave itself was blocked with a gigantic stone.

When Odysseus climbed from his ship onto the missing ship, they told him that Eurylochus had taken a party of six men, with wineskins of olive oil and some of the gold from sacking Troy, up to the cave just before dawn. They fell all over themselves with apologies for believing Eurylochus when he’d told them it was Odysseus’ orders to sail over to the larger island. Odysseus believed them; everyone knew Eurylochus was his brother-in-law and a trusted second. Well, maybe less trusted after today.

Odysseus took a skin of what was left of the wine stores aboard his ship, thinking he might need to use it to negotiate for the release of captives. Hopefully there were captives. Hopefully they weren’t already all dead. The wine he chose had come from King Priam’s stores, and was of the finest quality; he hadn’t let anyone drink from it yet, so there was still plenty of this particular vintage. He hated giving up any of what were already low stores of wine, especially not the wine of this quality, but the lives of men were more valuable than wine, however sweet.

He took six men himself, all volunteers, and gave orders to the two ships: the one Eurylochus had sailed over on should return to the smaller island, immediately. Odysseus’ flagship, which he had come over on, should tie up out of sight of the cave, and if they saw a monster coming their way, they should push off, and come back for Odysseus and the rest of the men later.

To his men, he said, as they were about to leave the ship, “From this point onward, you must never refer to me by name until we are far, far away from this island. Call me Captain, or Nobody.”

“Nobody?” one of the men asked. “What kind of a name is that?”

“Not much of one,” Nobody said, “but in this I’m following the guidance of the goddess Athena.” Technically he was not. Athena had told him to go to Cassandra, but the Nobody maneuver was his own idea. He didn’t want to explain to the men the entire logic behind being Nobody, though. “If you call me by the name of Ithaca’s king while we are on this island, we may all be doomed. So the goddess has warned me.”

Then he and his men climbed the rocky hillside and made their way through the pine trees, to reach the grazing meadows they had seen from the ground, the ones near the cave.

The herds weren’t wild, like the goats on the other island. The sheep had obviously been shorn relatively recently, and the goats’ fur was much cleaner than anyone would expect from goats. There was no shepherd around. The rock in front of the cave was of a different mineral than the outside of the cave, or most of the rock face they’d climbed up on. “That rock does not look like it should naturally be there,” Nobody said, “but it’s also much too large for even a number of men to move.”

“So an entire tribe’s worth of men decided to roll the rock in front of the cave?” Perimedes, one of his more trusted men, said. “Perhaps the monster is trapped in there.”

“Perhaps,” Nobody said. “But there’s another possibility. We should look for our men, but be very, very careful. Stick to the trees. Don’t go anywhere that you can be clearly seen from the grazing meadow.”

His intuition told him that the monster wasn’t trapped by men; the men, Odysseus’ men, were trapped by the monster.

***

They found no evidence of their crewmen by sunset, but then a monstrous man, easily three times the height and breadth of a normal man if not more, came to the cave, followed by sheep and goats. He had one round eye in the center of his head. “Cyclops,” Nobody whispered. Such creatures appeared in lore and travelers’ wild tales, but he had never actually thought they existed.

The Cyclops rolled aside the rock at the mouth of the cave, easily, and called within, “Choose two of the fattest and healthiest of your men to be my dinner tonight!”, laughing as he did. Even in the dim light of the setting sun, Nobody could see the blood drain from his men’s faces. He heard the distant sound of men screaming and wailing in fear. Nanny goats and ewes, kids and lambs, streamed past the Cyclops into the cave, unbothered by the sounds from within. The rams and billy goats stayed outside, continuing to nibble at grass, bushes, and the leaves of the poplar trees.

“They’re in there,” Nobody whispered. “And that creature is a man-eater.”

“Sir, we should leave this place!” one of his crewmen, a man named Amphialos, whispered. “We cannot fight such a monster! How many of our men can even be left alive in there, in the lair of a man-eater?”