#national american woman suffrage association

Text

No written law has ever been more binding than unwritten custom supported by popular opinion.

Carrie Chapman Catt

#Carrie Chapman Catt#quote#women's suffrage leader#National American Woman Suffrage Association#popular opinion

0 notes

Text

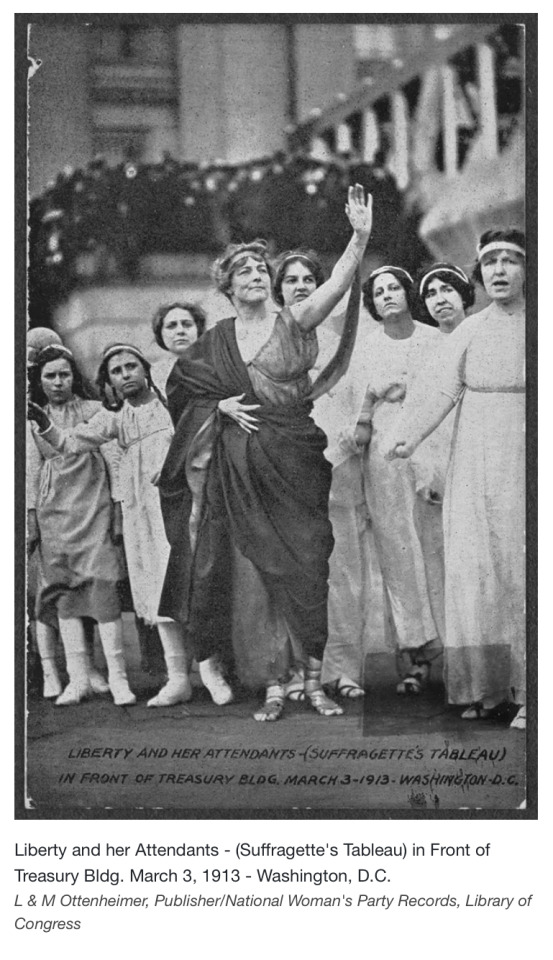

For Women’s History Month an article about the National American Woman Suffrage Association procession that includes the different women who marched.

"Miles of Fluttering Femininity Present Entrancing Suffrage Appeal"

Washington Post

On March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson's presidential inauguration, thousands of women marched along Pennsylvania Avenue--the same route that the inaugural parade would take the next day--in a procession organized by the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Designed to illustrate women's exclusion from the democratic process, the procession was carefully choreographed by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, the newly-appointed chairs of NAWSA's Congressional Committee. The committee was tasked with winning passage of the Susan B. Anthony amendment to the U.S. Constitution which was first proposed in 1878. The amendment reads:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

In the 35 years since the amendment was first proposed, it had only come up for a vote in Congress once and had failed. Paul and Burns were determined to bring new energy to the campaign for women's suffrage and to push for passage of the amendment.

The New Woman

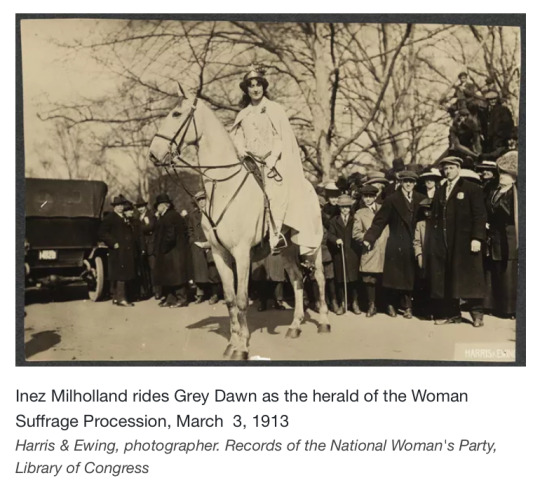

Inez Milholland rode a white horse named Grey Dawn at the front of the procession. Astride the horse rather than sidesaddle, she wore a white dress, a cape, and a golden tiara with the star of hope on top. Inez was famous as an activist, speaker, and lawyer. She was also very photogenic and was known as "the most beautiful suffragist." She rode as the herald of the future, an example of the New Woman of the twentieth century. This was the generation of suffragists who challenged society's expectations of what it meant to be a woman and the restrictions those ideas placed on the way women dressed and behaved. They called themselves feminists and were fighting not just for the vote but for full equality.

The Great Demand

Behind Inez in the procession was the first of over twenty floats. This float displayed a banner with the slogan that would become known as "The Great Demand."

"We demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of this country."

Alice Paul and the other organizers were declaring a new strategy. No longer content with incremental progress, with accepting limited voting rights won in bits and pieces one state or jurisdiction at a time, this new generation of suffragists were on a mission to secure their rights to the ballot across the country under the same terms as men. They chose their language deliberately to be somewhat shocking. In the past, American women advocating for suffrage tended to do so while remaining respectable and gracious. But to demand their rights was to step out of the expectations of women as demure and gentle. The Great Demand was meant to be provocative.

“

We march today to give evidence to the world of our determination, that this simple act of justice shall be done."

Woman Suffrage March program

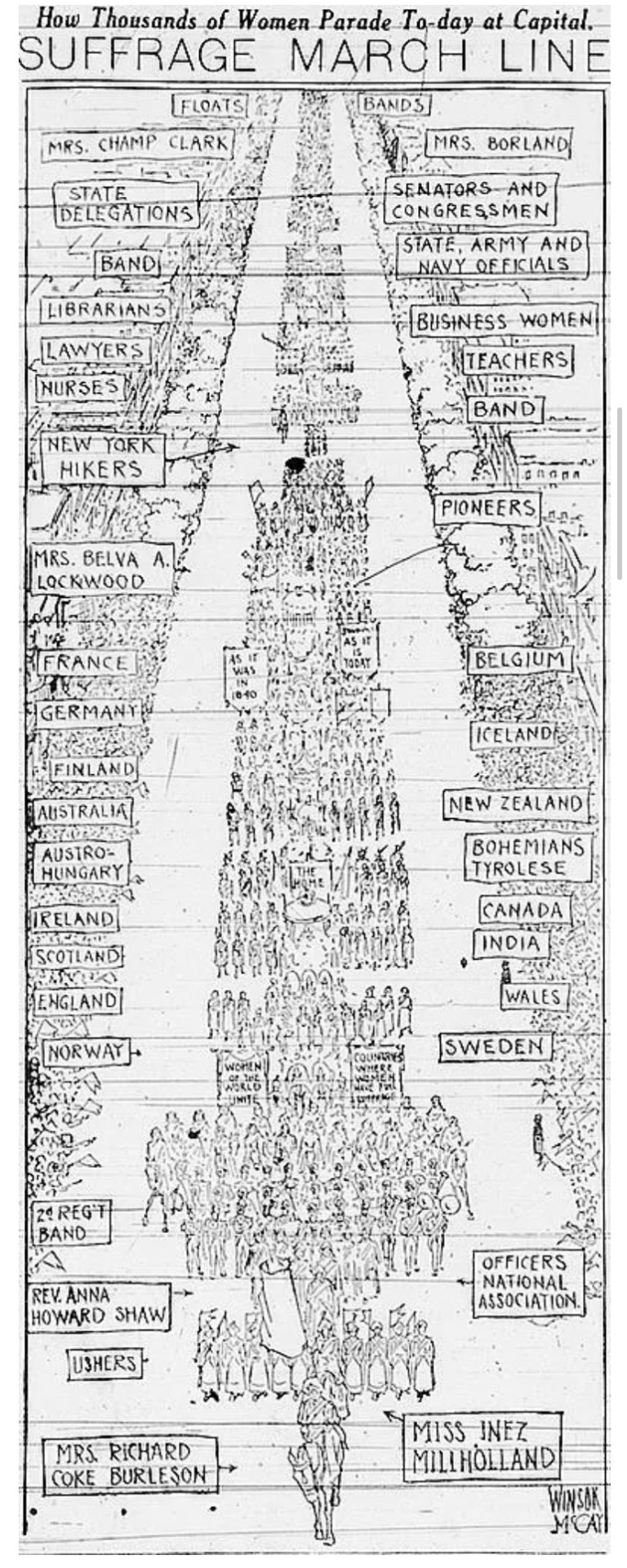

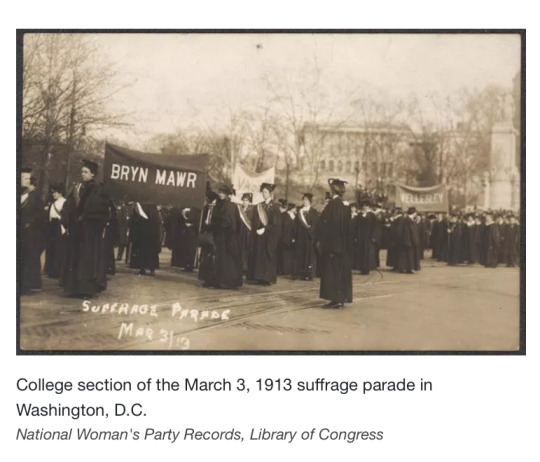

The procession was designed present an argument, section by section, about the accomplishments of women in the nation and around the world. Women marched in delegations from their states, or with others from their professions, or in their academic regalia from the universities they attended. It demonstrated that women's participation in the public sphere was dignified and in keeping with America's moral values. Behind the marchers, bands played patriotic songs and elaborate floats illustrated the beauty and competence of women.

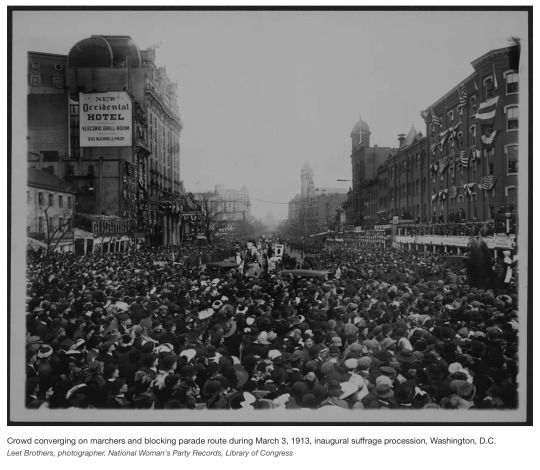

But very few of the spectators got to see the full demonstration as Paul had envisioned it. The crowd of at least 250,000 people did not stay on the sidewalk but began to stream into the streets and block the parade route. Police stationed along Pennsylvania Avenue were unable or unwilling to control the crowds. The marchers tried their best to continue. Those in cars or on horseback tried to drive the throng of people back and clear the street, but the crowd would simply fill back in behind them. Progress slowed and then stopped.

The marchers found themselves trapped in a sea of hostile, jeering men who yelled vile insults and sexual propositions at them. They were manhandled and spat upon. The women reported that they received no assistance from nearby police officers, who looked on bemusedly or admonished the women that they wouldn't be in this predicament if they had stayed home. Although a few women fled the terrifying scene, most were determined to continue. They locked arms and faced the ambush, some through tears. When they could, they ignored the taunts. Some brandished banner poles, flags, and hatpins to ward off attack. They held their ground until the U.S. Army troops arrived about an hour later to clear the street so that the procession could continue.

African American Women in the Procession

Black women felt like they were under attack long before the crowds descended upon the marchers. They had to fight just to be included in the procession. As described in the NAACP's newspaper:

“The women’s suffrage party had a hard time settling the status of Negroes in the Washington parade. At first, Negro callers were received coolly at headquarters. Then they were told to register, but found that the registry clerks were usually out. Finally, an order went out to segregate them in the parade, but telegrams and protests poured in and eventually the colored women marched according to their State and occupation without let or hindrance.” The Crisis, vol 5, no. 6, April 1913, page 267.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett traveled to Washington, D.C. with the Illinois delegation and fully expected to march with them. As the group was lining up to begin the procession, the white suffrage leaders suddenly asked Wells-Barnett not to march with her fellow suffragists from Illinois and instead assume a place in the back of the procession. Wells-Barnett refused and left the area. Instead, she waited along the side of Pennsylvania Avenue until the Illinois group marched by. Then she and two white allies stepped in front of the Illinois delegation and continued in the procession.

Although it is sometimes reported that African American women marched in the back of the procession, The Crisis reported that more than forty Black women processed in their state delegations or with their respective professions. Two were reported to have carried the lead banners for their sections. Twenty-five students from Delta Sigma Theta sorority from Howard University marched in cap and gown with the university women, as did six graduates of universities, including Mary Church Terrell.

"In spite of the apparent reluctance of the local suffrage committee to encourage the colored women to participate," reported The Crisis, "and in spite of the conflicting rumors that were circulated and which disheartened many of the colored women from taking part, they are to be congratulated that so many of them had the courage of their convictions and that they made such an admirable showing in the first great national parade.”

"Dawn Mist" and Native American Women

Before the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession, newspapers announced that one of the marchers would be “Dawn Mist, the beautiful daughter of Chief Three Bears of the Glacier National ParkIndians.” The papers reported that Dawn Mist and her friends would ride their Indian ponies in their buckskin dresses in the parade, and camp on the National Mall in their teepees. They would “represent the wildest type of American womanhood” side by side with white women like Inez Milholland, who represented “the highest type of cultured womanhood.”

But Dawn Mist wasn’t a real person.

She was a character created by the public relations department of the Great Northern Railroad. The railroad hired Native American women to perform as Dawn Mist – at least three of them. They used images of the women posing as Dawn Mist in advertising and on postcards. In 1913, Daisy Norris, a Blackfoot woman, was working in the role of Dawn Mist for the Railroad. But she wasn’t in D.C. for the Suffrage Procession. It was all a publicity stunt.

There was, however, at least one native woman in the 1913 parade. Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwinmarched with the lawyers contingent in the procession. Of French and Ojibwe heritage, she was the first native woman to become a lawyer. She had moved to D.C. with her father to fight for tribal sovereignty and became a federal civil servant, working for the Federal Indian Bureau. She later advocated for Native American suffrage in her work with the Society for American Indians.

The Suffrage Movement Re-energized

The procession ended, a hour or so later than planned, with a dramatic tableau on the steps of the Treasury Building. The next day, headlines in newspapers around the country proclaimed the drama of the Woman Suffrage Procession. The coverage of the march was often more prominent on the front pages than news of Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. Congress began an investigation to determine why crowd control by the police had been so ineffective. The hearings kept the procession in the news even longer. Although the Washington, D.C demonstration was not the first suffrage march or the largest, the publicity it received brought new attention and energy to the movement, energy that would eventually push the 19th Amendment through Congress.

Sources:

Cahill, Cathleen. Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement. UNC Press, 2020.

Rabinovitz-Fox, Einav. "New Women in Early Twentieth-Century America." Oxford Research Encyclopedias, August 2017.

Ware, Susan. Why They Marched: Untold STories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2019.

Zahniser, J. D. and Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. Oxford University Press, 2014.

#March 3 1913#National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA)#Woman Suffrage Procession#The Great Demand

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

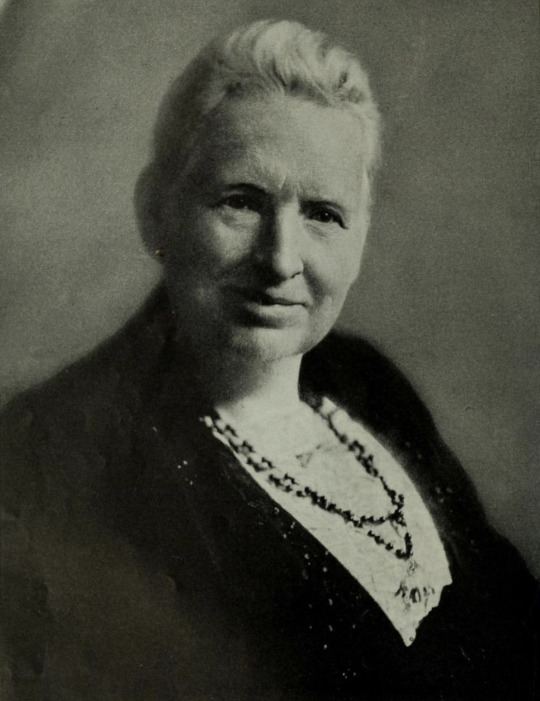

Mary Church Terrell

As we celebrate Black History Month, it’s a perfect time to honor the legacy of Mary Church Terrell, a pioneering civil rights and women’s rights activist. Born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1863, Terrell was among the first African American women to earn a college degree, graduating from Oberlin College. She dedicated her life to fighting for equality and justice, making significant contributions to the suffrage movement and the fight against racial discrimination.

Terell’s commitment to civil rights and women’s suffrage was deeply intertwined with her work in the Black Women’s Club Movement. She served as the first president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which advocated for voting rights and equal rights under the motto “lifting as we climb.” Terrell also played a crucial role in the founding of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) and the National Association for the Advancment of Colored People (NAACP).

One of Terrell’s most notable achievements was her involvement in a successful lawsuit in 1950 that led to the desegregation of restaurants in the Washington, DC, area. Terrell’s writings, including “A Colored Woman in a White World,” and “What it means to be Colored in the Capital of the United States,” have left a lasting impact on the struggle for racial and gender equality.

To explore more about Mary Church Terrell’s remarkable life and contributions, the National Archives offers additional resources here:

A Portrait of Mary Church Terrell: A glimpse into the grace and determination of the iconic figure https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/individuals/mary-church-terrell

Blogs related to Mary Church Terrell: Delve into detailed articles that explore various aspects of her life and legacy Rediscovering Black History Blog.

https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/

Unceasing Militant: The Life of Mary Church Terrell with Alison M. Parker: A recorded event that sheds light on Terrell’s multifaceted activism, held on December 17, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQYQRKKBr0A&embeds_referring_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.archives.gov%2Fresearch%2Fafrican-americans%2Findividuals%2Fmary-church-terrell&embeds_referring_origin=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.archives.gov&feature=emb_title

External: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/labor-love-restoration-ledroit-parks-mary-church-ee8xe/?trackingId=V7zIYQZE9YI5JgfRfOS4xg%3D%3D

#national archives#history#nationalarchives#black history month#bhm#african american history#mary church terrell

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

The single most impressive fact about the attempt by American women to obtain the right to vote is how long it took. From its earliest beginnings in the public speaking of Fanny Wright in the 1820s and the Grimké sisters in the 1830s, through the complex history of equal rights suffrage associations led by such woman's-rights pioneers as Lucy Stone, Susan Anthony, and Elizabeth Stanton, it was indeed a "century of struggle" (Flexner 1959) before the suffrage amendment to the Constitution was ratified and women could first participate in a national election. Of the first generation pioneers, only Antoinette Brown Blackwell lived to cast her ballot in that first election in 1920.

-Alice S. Rossi, The Feminist Papers: From Adams to de Beauvoir

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

Former NY Governor Alfred E. Smith welcomes Carrie Chapman Catt, women's suffrage leader, on her triumphal return from Tennessee, August 27, 1920. Tennessee was the last state to ratify the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. Miss Catt carries a bouquet of blue and yellow flowers, colors of the National American Woman's Suffrage Association.

Photo: Associated Press

#vintage New York#1920s#Carrie Chapman Catt#women's suffrage#19th Amendment#suffrage#suffragist#August 27#27 August#Al Smith#27 Aug.#Aug. 27#triumph#Constitutional amendment#right to vote

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

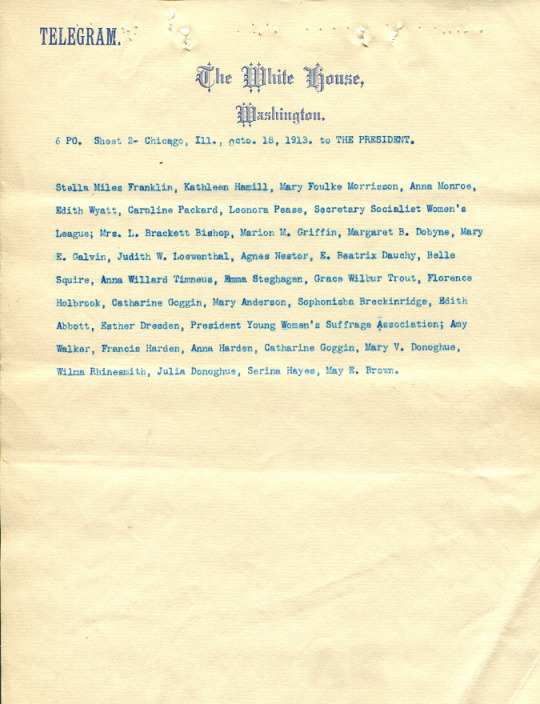

Telegram to President Woodrow Wilson from Jane Addams and Other Women Regarding the Deportation of Emmeline Pankhurst

Record Group 85: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service Series: Subject and Policy Files File Unit: Appeal of Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst for admittance for visit, English Suffragette

This telegram petitioned the Department of Labor and their decision to deport Emmeline Pankhurst, a British suffragette. The authors wanted the board to reconsider and maintain "America's devotion to liberty."

Telegram The White House, Washington 6 PO.FD. 283 139 extra 10:25 p.m. Sa, Chicago, Ill., October 18, 1913. The President. Whereas, the Associated Press reports to the American public that Mrs. Pankhurst's deportation has been ordered by the board of inquiry at Ellis Island and, Whereas, such action is in direct violation of the traditions and customs of the United States which has always been hospitable to the political offenders and revolutionists of all nations, and, Whereas, our sister republic, France, is at the present moment sheltering Christabel Pankhurst, Now, therefore, be it resolved: That we, the undersigned women of Chicago, protest against this flagrant violation of our long established public policy, and, Be it further resolved: That we respectively petition the Department of Labor in reviewing the case of this distinguished English woman to reconsider the decision of the Board of Inquiry and to admit Mrs. Pankhurst; thus maintaining the high traditions of America's devotion to liberty and right of free speech. (Signed) Jane Addams, Louise DeKoven Bowen, Mary Rozette Smith, Mary McDowell, Margaret Dreier Robins, Harriet Taylor Treadwell, President Chicago Political Equality League; Margaret A. Haley, Business Representative Chicago Teachers' Federation; Ida L. M. Furstman, President Chicago Teachers' Federation; Mrs. Harriet S. Thompson, Director Chicago Political Equality League; Edith A. Phelps, Anna Nichols, Laura Dainty Pelham,

Telegram The White House, Washington 6 PO. Sheet 2- Chicago, Ill., Octo. 18, 1913. to the President. Stella Miles Franklin, Kathleen Hamill, Mary Foulke Morrisson, Anna Monroe, Edith Wyatt, Caroline Packard, Leonora Pease, Secretary Socialist Women's League; Mrs. L. Brackett Bishop, Marion M. Griffin, Margaret B. Dobyne, Mary E. Galvin, Judith W. Loewenthal, Agnes Nestor, E. Beatrix Dauchy, Belle Squire, Anna Willard Timneus, Emma Steghagen, Grace Wilbur Trout, Florence Holbrook, Catharine Goggin, Mary Anderson, Sophonisba Breckinridge, Edith Abbott, Esther Dresden, President Young Women's Suffrage Association; Amy Walker, Francis Harden, Anna Harden, Catharine Goggin, Mary V. Donoghue, Wilma Rhinesmith, Julia Donoghue, Serina Hayes, May E. Brown.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

The social reaction to feminism includes a hatred of feminism, but as well, idealisations, which produce associations and attachments that shift and surge around a received identity of women and women’s causes as progressive. The problem of identity and identity-thinking - something no one can plausibly claim to be above - maintains because these identifications aren't stable, they were historically produced, and in the case of feminism, no authentic version exists.

Debates around the rights and wrongs of episodes in feminist history are therefore important because they are complex and wrought. Historians of suffrage help to challenge essentialism because it is clear that womanhood had no stable identity. The role of state power in splitting movement alliances becomes far clearer when an idealised story of national women’s rights struggle is troubled. And as Ellen Carol Dubois states, the paths taken by its leaders are hard to disconnect from their social backgrounds: “Woman suffrage leaders were rarely from the ranks of wage-earners. Some, like [Lucy] Stone and Anthony, were the daughters of small farmers. Others, most notably Stanton, were the children of considerable wealth.”27 After the word “male” entered into the Constitution for the first time, Stanton wrote in 1866: “if that word ‘male’ be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out.” In fact, once Reconstruction was overthrown and white supremacy reasserted, it was a century before Black Americans finally had some civil rights enforced by the federal government. Meanwhile, white women secured voting rights with the 20th Amendment in 1920.28

For Stanton and Anthony, the betrayal of "womanhood" by Black male suffrage could only be reduced to a conspiracy of male supremacy, Black and white. The lesson Stanton took: woman “must not put her trust in man.”29 Whilst shared patriarchy was an element, Black male enfranchisement came about in larger part due to Republican Party strategy and the Northern bourgeoisie’s attempt to secure postwar Reconstruction. That is, a calculation was made: Black men would vote Republican, white women would return the white supremacist Democrats to power.

...

-”Fascism and the Women's Cause: Gender Critical Feminism, Suffragettes and the Women's KKK”

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

[South Korean] Women, denied opportunities for formal education and careers outside the home for centuries, were no exception. In September of 1898, more than three hundred wives of Seoul aristocrats published the country's first women's-rights declaration in a local newspaper, stating that they no longer wanted to remain "deaf and blind." In the Yeo Gwon Tong Moon ("Women's-Rights Joint Statement"), released eight years after the National American Woman Suffrage Association had been formed in America, its authors took note of the fight "for gender equality" emerging around the world and demanded similar rights to formal education, work, and political participation.

That same month, hundreds of women formed the country's first women's-rights group, which, within a year, created a school for girls— the first founded by Korean women. While the school closed a few years later, as the state funding it had pleaded for never arrived, better funded schools created by Western missionaries continued to offer education for girls. Some of those young women went on to have careers, most typically as teachers;' many others also campaigned against child marriage and concubinage that were the norms in Korea at the time.

The beginning of South Korea’s feminist movement. From “Flowers of fire.”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[women protesting SCOTUS overturning Roe v. Wade]

* * * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

AUG 26, 2023

On this date in 1920, the U.S. Secretary of State received the official notification from the governor of Tennessee that his state had ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Tennessee was the 36th state to ratify the amendment, and the last one necessary to make the amendment the law of the land once the secretary of state certified it. He did that as soon as he received the notification, making this date the anniversary of the day the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified.

The new amendment was patterned on the Fifteenth Amendment protecting the right of Black men to vote, and it read:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

“Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Like the momentum for the Fifteenth Amendment, the push for rights for women had taken root during the Civil War as women backed the United States armies with their money, buying bonds and paying taxes; with their loved ones, sending sons and husbands and fathers to the war front; with their labor, working in factories and fields and taking over from men in the nursing and teaching professions; and even with their lives, spying and fighting for the Union. In the aftermath of the war, as the divided nation was rebuilt, many of them expected they would have a say in how it was reconstructed.

But to their dismay, the Fourteenth Amendment explicitly tied the right to vote to “male” citizens, inserting the word “male” into the Constitution for the first time.

Boston abolitionist Julia Ward Howe, the author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, was outraged. The laws of the age gave control of her property and her children to her abusive husband, and while far from a rabble-rouser, she wanted the right to adjust those laws so they were fair. In this moment, it seemed the right the Founders had articulated in the Declaration of Independence—the right to consent to the government under which one lived—was to be denied to the very women who had helped preserve the country, while white male Confederates and now Black men both enjoyed that right.

“The Civil War came to an end, leaving the slave not only emancipated, but endowed with the full dignity of citizenship. The women of the North had greatly helped to open the door which admitted him to freedom and its safeguard, the ballot. Was this door to be shut in their face?” Howe wondered.

The next year, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association, and six months later, Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe founded the American Woman Suffrage Association.

The National Woman Suffrage Association wanted a larger reworking of gender roles in American society, drawing from the Seneca Falls Convention that Stanton had organized in 1848.

That convention’s Declaration of Sentiments, patterned explicitly on the Declaration of Independence, asserted that “all men and women are created equal” and that “the history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her,” listing the many ways in which men had “fraudulently deprived [women] of their most sacred rights” and insisting that women receive “immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.”

While the National Woman Suffrage Association excluded men from its membership, the American Woman Suffrage Association made a point of including men equally, as well as Black woman suffragists, to indicate that they were interested in the universal right to vote and only in that right, believing the rest of the rights their rivals demanded would come through voting.

The women’s suffrage movement had initial success in the western territories, both because lawmakers there were hoping to attract women for their male-heavy communities and because the same lawmakers were furious at the growing noise about Black voting. Wyoming Territory granted women the vote in 1869, and lawmakers in Utah Territory followed suit in 1870, expecting that women would vote against polygamy there. When women in fact supported polygamy, Utah lawmakers tried unsuccessfully to take their vote away, and the movement for women’s suffrage in the West slowed dramatically.

Suffragists had hopes of being included in the Fifteenth Amendment, but when they were not, they decided to test their right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment in the 1872 election. According to its statement that anyone born in the U.S. was a citizen, they were certainly citizens and thus should be able to vote. In New York state, Susan B. Anthony voted successfully but was later tried and convicted—in an all-male courtroom in which she did not have the right to testify—for the crime of voting.

In Missouri a voting registrar named Reese Happersett refused to permit suffragist Virginia Minor to register. Minor sued Happersett, and the case went all the way to the Supreme Court. The justices handed down a unanimous decision in 1875, deciding that women were indeed citizens but that citizenship did not necessarily convey the right to vote.

This decision meant the fat was in the fire for Black Americans in the South, as it paved the way for white supremacists to keep them from the polls in 1876. But it was also a blow to suffragists, who recast their claims to voting by moving away from the idea that they had a human right to consent to their government, and toward the idea that they would be better and more principled voters than the Black men and immigrants who, under the law anyway, had the right to vote.

For the next two decades, the women’s suffrage movement drew its power from the many women’s organizations put together across the country by women of all races and backgrounds who came together to stop excessive drinking, clean up the sewage in city streets, protect children, stop lynching, and promote civil rights.

Black women like educator Mary Church Terrell and journalist Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, publisher of the Woman’s Era, brought a broad lens to the movement from their work for civil rights, but they could not miss that Black women stood in between the movements for Black rights and women’s rights, a position scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw would identify In the twentieth century as “intersectionality.”

In 1890 the two major suffrage associations merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association and worked to change voting laws at the state level. Gradually, western states and territories permitted women to vote in certain elections until by 1920, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, California, Oregon, Arizona, Kansas, Alaska Territory, Montana, and Nevada recognized women’s right to vote in at least some elections.

Suffragists recognized that action at the federal level would be more effective than a state-by-state strategy. The day before Democratic president Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated in 1913, they organized a suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., that grabbed media attention. They continued civil disobedience to pressure Wilson into supporting their movement.

Still, it took another war effort, that of World War I, which the U.S. entered in 1917, to light a fire under the lawmakers whose votes would be necessary to get a suffrage amendment through Congress and send it off to the states for ratification. Wilson, finally on board as he faced a difficult midterm election in 1918, backed a constitutional amendment, asking congressmen: “Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

Congress passed the measure in a special session on June 4, 1919, and Tennessee’s ratification on August 18, 1920, made it the law of the land as soon as the official notice was in the hands of the secretary of state. Twenty-six million American women had the right to vote in the 1920 presidential election.

Crucially, as the Black suffragists had known all too well when they found themselves caught between the drives for Black male voting and women’s suffrage, Jim Crow and Juan Crow laws meant that most Black women and women of color would remain unable to vote for another 45 years. And yet they never stopped fighting for that right. For all that the speakers at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Equality were men, in fact women like Fannie Lou Hamer, Amelia Boynton, Rosa Parks, Viola Liuzzo, and Constance Baker Motley were key organizers of voting rights initiatives, spreading information, arranging marches, sparking key protests, and preparing legal cases.

And now women are the crucial demographic going into the 2024 elections. Democratic strategist Simon Rosenberg noted in June that there was a huge spike of women registering to vote after the Supreme Court in June 2022 overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision recognizing the constitutional right to abortion, and that Democratic turnout has exceeded expectations ever since.

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#women's rights#human rights#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#the right to vote#National Women#Suffrage Assn.#history#14th amendment

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Susan B. Anthony (1820 - 1906) was a social reformer and suffragist who dedicated her life to the fight for women's suffrage and civil rights.

Susan was the second of seven children born to a Quaker father and Methodist mother. She formed a close partnership with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was married with seven children. Together, they became leaders in several organizations dedicated to the cause of abolition and civil rights, including the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Susan gave speeches and organized events in order to raise awareness and gain support for their causes. Her impact on the fight for women's suffrage and civil rights will always be remembered on AncientFaces.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

When an Anti-Suffragette was Elected to Congress

The first woman elected to Congress was suffragist and feminist Jeannette Pickering Rankin of Montana, but the second woman elected to Congress was anti-suffragist and anti-feminist Alice Mary Robertson of Oklahoma.

Robertson began her career as a clerk for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1873, when she was only 19 years old. For her, this position might have come easy, considering her family had worked to assist displaced Native Americans and translated works into the Creek language. She had also grown up in Creek Nation, Arkansas. After her time at the Bureau, she went home to work as a teacher, later moving around the country to teach at Indian boarding schools. Later, she was appointed by the Bureau as the first government supervisor of Creek schools and then was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as the postmaster of Muskogee, Oklahoma, making her the first woman postmaster of a class A post office. Roosevelt called her “one of the great women of America.” In 1916, she was nominated by the GOP to run for county superintendent of public instruction, though she lost.

While Oklahoma was never a state that had a strong anti-suffrage presence, as it had voted firmly against woman suffrage in the past, the push for a national suffrage amendment spurred antis into action. In 1918, the Oklahoma Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was formed, with Robertson as their Vice President. After their loss in 1920, Robertson ran to be a Representative of the 2nd District of Oklahoma and won (though by a narrow margin). She was a Republican.

Today it looks hypocritical for a woman like Robertson to take part in government when she was against women having the vote, but, according to her, she argued that she had been “drafted” into her position. Quite simply, anti-suffrage women were going to be forced to vote. If they didn’t, then the women who did vote, suffragists and feminists, would be speaking for them and a number of other unwanted motions would be forced on them as well. This also applied to representation in government: there had to be women who went to state and federal governments to accurately represent these conservative women. Antis struggled to find representation, as the majority of women like them were too busy with other affairs, like child rearing, social work, and charitable affairs, to devote themselves to government. Robertson was able to do this, however, and so she did. She was not going to let feminists and suffragists speak for her.

She became known for her anti-feminist stance while in Congress. She opposed the Sheppard-Towner Maternity Bill, which feminists supported, saying “Let the women look to their own selves if they want to change conditions. I don’t believe much for the home can be done by national legislation.” She also stood against feminist organizations, like the League of Woman Voters, and other organizations like this “that will be used as a club against men”, as she put it. The rest of her voting record is rather conservative: tough on immigration and for small government, while pushing for federal appropriations to reimburse the Cherokee who had been removed from their original home to Oklahoma in the 19th century. She was the lone woman politician in Congress at the time.

Unfortunately for her, she would not be re-elected in 1922. She had only won by a little over 200 votes in 1920, so her chances were slim in the first place. She went back to running her cafe, “Sawokla”, after her time in Congress, though she was ousted by the WWI veterans of her community for her lack of support for the Bonus Bill, which would have provided them early payment on their military service pensions. She would pass away in 1931.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

NPS Photos of Fay Fuller (left) and Alma Wagon (right).

This year for International Mountain Day, we are recognizing that “women move mountains” and play a key role in mountain communities around the world. Women like Fay Fuller, the first woman to summit Mount Rainier, and Alma Wagon, the park’s first female climbing guide, paved the way for generations of women to challenge themselves– and the conventions of their time– on the slopes of Mount Rainier. Suffragists attending the 41st Annual American Woman Suffrage Association convention joined members of The Mountaineers to summit Mount Rainier in July, 1909. Dr. Cora Smith Eaton carried a "Votes for Women" pennant on the climb to fly at Mount Rainier's snowy crater. Inspired in part by this climb, Washington State passed a law to allow women to vote in 1910, which helped revitalize the national suffragist movement. How have mountains like Mount Rainier inspired you?

Asahel Curtis/Washington State History Museum photo of the “Votes for Women” pennant on the summit of Mount Rainier.

Learn more about mountains throughout the National Park Service at https://go.nps.gov/mountains.

~kl

#Mountains Matter#International Mountain Day#mount rainier national park#women's history#mountain climbing

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

More women in big corporations mean a better chance of the publics learning of any wrong doings

A number of high-profile whistleblowers in the technology industry have stepped into the spotlight in the past few years. For the most part, they have been revealing corporate practices that thwart the public interest: Frances Haugen exposed personal data exploitation at Meta, Timnit Gebru and Rebecca Rivers challenged Google on ethics and AI issues, and Janneke Parrish raised concerns about a discriminatory work culture at Apple, among others.

Many of these whistleblowers are women – far more, it appears, than the proportion of women working in the tech industry. This raises the question of whether women are more likely to be whistleblowers in the tech field. The short answer is: “It’s complicated.”

For many, whistleblowing is a last resort to get society to address problems that can’t be resolved within an organization, or at least by the whistleblower. It speaks to the organizational status, power and resources of the whistleblower; the openness, communication and values of the organization in which they work; and to their passion, frustration and commitment to the issue they want to see addressed. Are whistleblowers more focused on the public interest? More virtuous? Less influential in their organizations? Are these possible explanations for why so many women are blowing the whistle on big tech?

To investigate these questions, we, a computer scientist and a sociologist, explored the nature of big tech whistleblowing, the influence of gender, and the implications for technology’s role in society. What we found was both complex and intriguing.

Narrative of virtue

Whistleblowing is a difficult phenomenon to study because its public manifestation is only the tip of the iceberg. Most whistleblowing is confidential or anonymous. On the surface, the notion of female whistleblowers fits with the prevailing narrativethat women are somehow more altruistic, focused on the public interest or morally virtuous than men.

Consider an argument made by the New York State Woman Suffrage Association around giving U.S. women the right to votein the 1920s: “Women are, by nature and training, housekeepers. Let them have a hand in the city’s housekeeping, even if they introduce an occasional house-cleaning.” In other words, giving women the power of the vote would help “clean up” the mess that men had made.

More recently, a similar argument was used in the move to all-women traffic enforcement in some Latin American cities under the assumption that female police officers are more impervious to bribes. Indeed, the United Nations has recently identified women’s global empowerment as key to reducing corruption and inequality in its world development goals.

There is data showing that women, more so than men, are associated with lower levels of corruption in government and business. For example, studies show that the higher the share of female elected officials in governments around the world, the lower the corruption. While this trend in part reflects the tendency of less corrupt governments to more often elect women, additional studies show a direct causal effect of electing female leaders and, in turn, reducing corruption.

Experimental studies and attitudinal surveys also show that women are more ethical in business dealings than their male counterparts, and one study using data on actual firm-level dealings confirms that businesses led by women are directly associated with a lower incidence of bribery. Much of this likely comes down to the socialization of men and women into different gender roles in society.

Hints, but no hard data

Although women may be acculturated to behave more ethically, this leaves open the question of whether they really are more likely to be whistleblowers. The full data on who reports wrongdoing is elusive, but scholars try to address the question by asking people about their whistleblowing orientation in surveys and in vignettes. In these studies, the gender effect is inconclusive.

However, women appear more willing than men to report wrongdoing when they can do so confidentially. This may be related to the fact that female whistleblowers may face higher rates of reprisal than male whistleblowers.

In the technology field, there is an additional factor at play. Women are under-represented both in numbers and in organizational power. The “Big Five” in tech – Google, Meta, Apple, Amazon and Microsoft – are still largely white and male.

Women currently represent about 25% of their technology workforce and about 30% of their executive leadership. Women are prevalent enough now to avoid being tokens but often don’t have the insider status and resources to effect change. They also lack the power that sometimes corrupts, referred to as the corruption opportunity gap.

In the public interest

Marginalized people often lack a sense of belonging and inclusion in organizations. The silver lining to this exclusion is that those people may feel less obligated to toe the line when they see wrongdoing. Given all of this, it is likely that some combination of gender socialization and female outsider status in big tech creates a situation where women appear to be the prevalent whistleblowers.

It may be that whistleblowing in tech is the result of a perfect storm between the field’s gender and public interest problems. Clear and conclusive data does not exist, and without concrete evidence the jury is out. But the prevalence of female whistleblowers in big tech is emblematic of both of these deficiencies, and the efforts of these whistleblowers are often aimed at boosting diversity and reducing the harm big tech causes society.

More so than any other corporate sector, tech pervades people’s lives. Big tech creates the tools people use every day, defines the information the public consumes, collects data on its users’ thoughts and behavior, and plays a major role in determining whether privacy, safety, security and welfare are supported or undermined.

And yet, the complexity, proprietary intellectual property protections and ubiquity of digital technologies make it hard for the public to gauge the personal risks and societal impact of technology. Today’s corporate cultural firewalls make it difficult to understand the choices that go into developing the products and services that so dominate people’s lives.

Of all areas within society in need of transparency and a greater focus on the public interest, we believe the most urgent priority is big tech. This makes the courage and the commitment of today’s whistleblowers all the more important.

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The ballot, wisely used, will bring to her the respect and protection that she needs. It is her weapon of moral defense. Under present conditions, when she appears in court in defence of her virtue, she is looked upon with amused contempt. She needs the ballot to reckon with men who place no value upon her virtue, and to mould healthy public sentiment in favor of her own protection."

Say hello to D.C.'s own Nannie Helen Burroughs: teacher, suffragist, union advocate, and civil rights pioneer. Born in 1879/1880 Virginia to formerly enslaved parents, Burroughs later moved to D.C., graduating from M Street High School and making the acquaintance of comtemporaries like Mary Church Terrell (Lesson #29 in this series). Burroughs became deeply involved in the dual causes of womens' suffrage and civil rights, mentored by Walter Henderson Brooks (look for a future lesson in this Series about him), who was then a pastor at the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church.

Later Burroughs founded the Womens' Convention of the National Baptist Convention and served as its director for 13 years. Burroughs and her fellow D.C. resident Mary McLeod Bethune (Lesson #49 in this series), also organized and formed the National Association of Wage Earners. Burroughs rose to prominence as an outspoken voice for Black women; arguing that they should have the same opportunities for education and for job training. Such was her gift for writing and for oration that she was appointed by President Herbert Hoover to chair a special committee on housing for African Americans.

Perhaps Burroughs' greatest accomplishment (certainly the one of which she was the proudest), was the funding and eventual founding of the National Training School for Women And Girls in 1909. Encouraged and advocated by key Washington figures such as historian Carter G. Woodson (look for a future lesson in this Series about him, as well), the school was notable for never having solicited money from white donors. Burroughs wanted each student to become "the fiber of a sturdy moral, industrious and intellectual woman," and over the course of the next 20 years, the school grew into a rigorous curriculum of academic and vocational courses; offering a unique combination of educational opportunities for Black young women and girls. At the time the school offered academic training equivalent to the upper grades of high school and community college, religious instruction, and training in domestic arts and vocations; and perhaps most importantly, the very first American institution to offer all of these opportunities within a single educational space.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By 1850 the husband-killing woman—the household fiend—was no longer a joke. She had become a social problem, and for every husband, potentially a personal one. The question was how to spot her in advance. By the end of the century the new "science" of criminology would confirm that sensual women were likely to be criminals, thus reassuring men—as these mid-century fictions did—that the murderer and the true woman (appearances notwithstanding) were completely different kinds of people. Even, some said, different species: fiends and angels.

The early feminists didn't think so. In a sophisticated attack on marriage, divorce, and property laws, they argued all along that the institution of marriage bound women in desperate circumstances. Even after the Civil War, when the more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association campaigned exclusively for the ballot, the radical Stanton-Anthony wing of the movement continued to attack marriage. In 1868 The Revolution, the official publication of their National Woman Suffrage Association, editorialized:

The ballot is not even half the loaf; it is only a crust—a crumb. The ballot touches only those interests, either of women or men, which take their root in political questions. But woman's chief discontent is not with her political, but with her social, and particularly her marital bondage. The solemn and profound question of marriage . . . is of more vital consequence to woman's welfare, reaches down to a deeper depth in woman's heart, and more thoroughly constitutes the core of the woman's movement, than any such superficial and fragmentary question as woman's suffrage.

Their analysis of marriage led the radicals to conclude that the very structure of the institution might make the people within it murderous.

The institution of marriage is either the greatest curse or the greatest blessing known to society. It brings two people into the closest of all possible relations; it puts them into the same house; it seats them at the same table; it thrusts them into the same sleeping apartment, in short, it forces upon them an intimate and constant companionship from which there is no escape. More than this, it makes any attempt at escape disreputable: the man or woman who seeks to loosen or break the tie which he or she finds intolerable, is frowned upon by society. The fracture of the galling chain must be made at the expense of the reputation of one or both of the parties bound together. There is no hope for two people shackled in the manacles of an unhappy marriage, but a release by death; and no wonder that each desires deliverance, and longs for the death of the other.

Yet what can be more horrible or more degrading to human nature than such a situation. Can anything be more demoralizing than this position of two people living under the same roof, forced into daily and almost hourly companionship, each of whom secretly desires the death of the other.

That the number of people who find marriage intolerable is not small, the annals of crime prove. Wife murders are so common that one can scarcely take up a newspaper without finding one or more instances of this worst of all sins; and none but God can know how many men and women are murderers at heart.

They predicted that as long as "men and women marry in the same old hap-hazard way, learning nothing from each other's experience" the result would be "what one might expect, confusion, misery and crime."

Conservatives counterattacked, turning the argument upside down and using it against all claims to any women's rights, including suffrage. Marriage, they said, was instituted by God, not man; and "woman was created to be a wife and a mother" and "to make home cheerful, bright, and happy." Therefore, any woman who tried to alter woman's sphere or to step out of it in any way—whether by voting or by poisoning her husband—must be "unnatural." A woman living "an independent existence, free to follow her own fancies and vague longings, her own ambition and natural love of power, without masculine direction or control, . . . is out of her element, and a social anomaly, sometimes a hideous monster, which men seldom are, excepting through a woman's influence." In short, it was woman as monster who threatened the institution of marriage and not the other way around.

This conservative argument, backed by the full force of religion and masculine "reason" and soon bolstered by the sciences of criminology and psychology, overwhelmed the tentative and sometimes inconsistent insights of the radical feminists. And when social anthropologists proclaimed the patriarchal nuclear family the most highly evolved and "civilized" form of social organization, feminists seem reactionary and barbaric indeed. So, by the end of the nineteenth century, almost everyone had been converted to the "domestic mythology", and even once-radical feminists campaigned for woman suffrage on the grounds that it would strengthen the American family.

-Ann Jones, Women Who Kill

#ann jones#amerika#american history#womens history#womens suffrage#female killers#love and marriage#patriarchy#nuclear family

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating the Legacy of Alice Dunbar-Nelson on her birthday 📚 🗞️ Today, we're shining a light on the incredible Alice Dunbar-Nelson, a trailblazing writer, poet, educator, and activist whose impact continues to resonate through the ages. Let's dive into some fascinating facts about this remarkable woman: ✍️ Alice Dunbar-Nelson was born on July 19, 1875, in New Orleans, Louisiana. She emerged as a prominent figure during the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement that celebrated African American art, literature, and intellectualism. 📖 As an accomplished writer, Dunbar-Nelson published numerous poems, short stories, and essays that explored themes of race, gender, and social justice. Her work often confronted the intersectionality of identity and addressed the struggles faced by African Americans and women in society. 🎓 Education played a crucial role in Dunbar-Nelson's life. She earned a teaching degree from Straight University (now Dillard University) in New Orleans and later pursued further studies at Cornell University. Throughout her career, she advocated for education as a means of empowerment and social progress. 🌍 Dunbar-Nelson was also a passionate activist, fighting for civil rights, women's suffrage, and racial equality. She actively participated in organizations like the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and worked alongside prominent activists of her time. 💡 In addition to her literary achievements, Alice Dunbar-Nelson broke barriers as one of the first African American women to gain recognition as a journalist. She contributed articles to various newspapers, using her platform to advocate for social change and challenge prevailing stereotypes. 📚 Beyond her own creative endeavors, Dunbar-Nelson played a pivotal role in promoting the work of other writers and artists. She was known for organizing literary salons, fostering a vibrant intellectual and artistic community that nurtured and celebrated African American talent. 🌟 Alice Dunbar-Nelson's legacy serves as a beacon of inspiration, reminding us of the power of words, activism, and the pursuit of equality. Her fearless voice and unwavering dedication continue to pave the way for future generations.

3 notes

·

View notes