#naturalisation of a subject before the law

Text

Difference Between British Citizen And A British Overseas Citizen

British citizens and British overseas citizens are two different categories of British nationality. A British national is free to reside and work in the UK without having to adhere to immigration laws. On the other hand, a British national living abroad has little rights in the UK.

British Nationality Types

One of the rare nations with dual citizenships is the United Kingdom. There are six different categories of British nationality. For each citizenship right, they each have different rules. The many British nationalities are briefly covered by the best immigration lawyer in Ireland.

British nationals

People who have the status of Citizen of the UK & Colonies (CUKC) and the right to abode in the United Kingdom and Isles are considered to be British Citizens. By virtue of naturalisation or birth in the United Kingdom and Isles, they get British citizenship.

British nationals abroad

People who retained their British citizenship after gaining independence from Britain are typically given this citizenship. In other terms, a legacy citizenship deriving from connections to a former British colony is known as a British Overseas Citizenship.

British citizens

Those who were neither CUKCs nor citizens of another Commonwealth nation at the time of their birth are known as British subjects. Due to their residence in British India or the Republic of Ireland up to 1949, the majority were British nationals.

BNO, or British National Overseas

The British Nationality (Hong Kong) Order of 1986 and the Hong Kong Act of 1985 created the BNO status.

Residents of Hong Kong who sought for registration as BNOs before Hong Kong was ceded to the People's Republic of China are the BNO holders.

BPP, British Protected Person

The position of a British Protected Person is a legacy of parts of the British Empire that were client states or protected states with seemingly independent leaders under the protection of the Crown but were not formally a part of the empires of the Crown.

Because they are neither Commonwealth citizens nor British nationals, nor are they foreigners, BPPs have a special status.

Citizens of British Overseas Territories (BOTC)

According to the best immigration lawyer in Ireland, people who have British nationality as a result of their connection to a British Overseas Territory are referred to as British Overseas Territories citizens. On January 1, 1983, you acquired citizenship of the British overseas territories if both of the following criteria were satisfied:

If you were a citizen of the CUKC on December 31, 1982, and you were related to a British overseas territory because your ancestor was born there or was naturalised there.

If you were married to a guy who acquired citizenship in one of the British overseas territories on January 1, 1983.

Note that on June 30, 1997, when China reclaimed sovereignty, anyone who possessed British Overseas Territories citizenship due to their connection to Hong Kong lost it. However, if any of the following requirements are satisfied, a person may become a British overseas citizen:

If they were born after July 1, 1997, they were stateless, not citizens of any nation.

if they were born to parents who were British nationals (abroad) or BOC.

A person is considered a British citizen if they were born in the UK and at least one of their parents is or was a British citizen or if they were residents of England, Wales, Scotland, or Northern Ireland at the time of their birth.

A person acquired British citizenship in 1983 if they were a resident of the United Kingdom or one of its territories or if they had the "right of abode" there. People who have the right to abode are exempt from immigration control and don't need a visa or other authorization to enter the UK. These individuals are unrestricted in their ability to live and work anywhere in the nation.

0 notes

Photo

“COST THIS SETTLER JUST $41.25 TO VOTE,” North Bay Nugget. January 9, 1932. Page 6.

----

Percy Andrews Is Fined In Court at Haileybury for Assaulting His Son-In-Law

----

Haileybury, Jan.9 — It cost Percy Andrews $41.25, plus his own expenses and his lawyer's fee, to cast his vote for the school trustee he favored at the annual school meeting in Henwood township, 25 miles northwest of here, and held on December 30 last. Andrews, a settler of that district was charged before Magistrate Atkinson in police court here yesterday with assaulting his son-in-law, Peter Beneke, who was a scrutineer at the meeting, and when he admitted a technical assault sentence was suspended on payment of the costs, which were quite high owing to the distance to be traveled.

According to the evidence, Beneke required his 52-year-old father-in-law to take the oath before he could vote and when Charles Robinson, the returning officer, started to administer it, Andrews would not swear he is on the assessment roll but would swear he was entered on the voters' lists for federal and provincial elections. The property on which he lives us assessed in his wife's name, Andrews said. Beneke said that for some reason Andrews did not want to repeat the oath and both agreed that after voting, the older man pushed Beneke in the face tripped him up and threw him on the floor.

Beneke himself said he had not been hurt, while Andrews, in his evidence, told of committing what he termed "aggravated assault,” of pushing Beneke over and of going out immediately. Defendant was told by the court he was charged only with common assault. Andrews is an Englishman living in that section and the complainant, Beneke, is a German by birth but is naturalised as a British subject. To W. C. Inch, appearing for Andrews, Beneke said he had been appointed scrutineer by the meeting and that his father-in-law mounted the platform to assault him.

#haileybury#aggravated assault#returning officers#police court#school trustee#school board#swearing an oath#german canadians#german immigration to canada#naturalized canadian#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#northern ontario

0 notes

Link

On 18 May 2021, the National Unity Government (NUG) of Myanmar announced they are now in the process of drafting a new federal union constitution, which as promised by the NUG, will “guarantee democracy, national equality and self-determination based on freedom, equality and justice.”

Later in June, the shadow government, formed by lawmakers and politicians ousted in the February coup, issued a ground-breaking statement suggesting that the Rohingya people would be “entitled to citizenship by laws that will accord with fundamental human rights norms and democratic federal principles,” and once the new constitution has been drafted, Myanmar’s citizenship laws, which have been blamed for reducing the Rohingya to statelessness, could be repealed.

This promise was made over seventy years ago, when Myanmar (formerly Burma) achieved independence from Britain, and the government of the Union of Burma enacted its first constitution in 1947.

Providing a general description in terms of the classification and definition of a Myanmar citizen, the 1947 constitution effectively allowed Rohingyas to qualify for citizenship, as Myanmar citizens were defined as persons who belong to an indigenous race, have at least one grandparent from an indigenous race, are children of citizens, or lived in British Burma prior to 1942.

Unfortunately, after the coup led by Ne Win in 1962, the 1947 constitution was suspended. Ne Win’s military government enacted a new constitution in 1974 which withdrew many provisions of the 1947 constitution, and a large number of Rohingya residents in Arakan were thereafter disqualified for citizenship.

Not much has changed since then. The current constitution, enacted in 2008, requires Rohingyas to qualify for citizenship by providing proof that their parents are citizens or that they are already citizens. This is difficult, since most Rohingya people do not hold valid documents to substantiate their claim for citizenship. Thus, the 2008 Constitution continues to refuse them the possibility of becoming legitimate citizens in Myanmar.

Supplementing constitutional changes, immigration and citizenship laws have played a key role in gradually depriving Rohingyas of their citizenship in Myanmar. Some examples of such laws include the Burma Immigration (Emergency Provisions) Act of 1947, the Union Citizenship Act of 1948, and the Burma Citizenship Law of 1982.

The Burma Immigration (Emergency Provisions) Act of 1947 was originally intended to be an emergency measure regulating the entry of foreigners into Myanmar prior to its independence. Any person suspected of contravening the Act can be arrested without warrant. Myanmar’s immigration authority has the sole power to judge if a person deemed to be “foreigner” had contravened the Act, whether such a “foreigner” should be deported, and how long the “foreigner” should be detained pending deportation. A “foreigner” can also be punished with imprisonment for several years. Given its broad coverage and sweeping powers, a large number of Rohingya people have been persecuted under the Act.

The Union Citizenship Act of 1948 (UCA) was enacted to clarify the issue of citizenship in the 1947 Constitution. Narrowing the scope, article 3(1) of the Act stipulates that “indigenous races of Burma,” for the purpose of the Constitution, refers to the seven racial groups of Arakanese, Burmese (Burman), Chin, Kachin, Karen, Kayah, Mon, Shan, or racial groups that have settled in Myanmar as their permanent home before 1823. Although the Act could be subject to more expansive interpretation, the Rohingya, as a separate ethnic group, were generally not recognised as an “indigenous race.”

In 1982, Myanmar’s government repealed the UCA and enacted the Burma Citizenship Law, which formally refuted the legality of citizenship of almost all Rohingyas. Access to “naturalized citizenship” applies only to those who have entered and resided in Myanmar before 1948 and their offspring born within Myanmar, provided that “conclusive evidence” is furnished. As many Rohingyas settled in Arakan generations ago, and few of them can provide proof of residence because of low literacy and lack of record keeping, they were effectively stripped of their citizenship after enactment of this Law.

Myanmar’s constitution and states laws may be the cause of the plight of Rohingya people. However, such legal developments are tied to two larger phenomena, which both contribute to the persistent exclusion and persecution suffered by the Rohingya.

The first is nativism rooted in Myanmar’s nationalism. This Buddhism-based nationalist ideology, developed during the colonial era by the ethnic majority Burmans to oppose British rule, became the primary means for Myanmar’s political and religious leaders to pursue national stability in post-independence Myanmar. As Myanmar national identity is closely connected with Buddhism, nationalistic sentiments drive many Myanmar people to fear the invasion of “foreign” cultures that threaten Myanmar’s Buddhist culture. Muslim Rohingyas, consequently, are seen by many as “illegal immigrants” posing significant threat to the Myanmar national identity.

With notable support from the population, the Myanmar government has, throughout the years, especially the military junta, has capitalised on the widespread, long-standing public resentment of the Rohingya to consolidate support. Together with local authorities, Buddhist nationalists in Rakhine have persecuted the Rohingyas by ousting them from their jobs, shutting down mosques, confiscating property, and imprisoning or exiling community leaders.

Importantly, they have also exerted great influence in the formulation of laws restricting interfaith marriage, religious conversion, and polygamy. While constitutional reforms and the immigration and citizenship laws laid the foundation for persecution, religiously discriminatory laws, known as the “race and religion protection laws,” systematised and further intensified the pervasive discrimination against the Rohingya people.

The second phenomena is the law and order obsession. From British colonial era to the present, different governments of Myanmar have continued to pursue a governance model prioritising regime stability and efficiency. Rule of law in Myanmar essentially exists in the thin, narrow, and procedural conception, deprived of values such as equality, fairness, and protection of individual rights as in substantive justice.

There might have been some elements of substantive rule of law in the earlier post-independence years, but most of them were swept away following decades of military rule. The maintenance of law and order, through suppressing dissent and delimiting fundamental rights, was in line with the juntas’ goal of containing ethnic conflict and promoting national unity. Even today, this obsession with law and order remains strong in Myanmar’s politics.

To achieve justice for the Rohingya, drafting a new constitution and repealing discriminatory state laws is a good start. The NUG needs to develop clear vision for a more equal and inclusive Myanmar. Reforms should be proposed to improve the Rohingya’s legal status and abolish practices that violate fundamental rights. Considering the strong sentiments of Myanmar’s nationalism, instead of recognising the Rohingya as indigenous race, it may be more feasible to recognize them as naturalised citizens, thus granting them the rights to freedom of movement, communal representation, and dignified living conditions.

However, to truly put an end to the persecution of Rohingyas and promote trust between ethnic groups, it is also necessary for the people of Myanmar to rethink their understanding of nationalism. It is only with a more inclusive form of nationalism adhering to the values of equality, tolerance, and diversity, that the discriminatory attitudes toward Rohingyas can change, and effective long-term measures can be implemented to secure justice and dignity for the Rohingya people.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Fayette - an American Citizen?

As promised, @msrandonstuff :-)

The question weather La Fayette was an American citizen had for quite a time been the subject of debates - both during La Fayette’s lifetime as well as long after his death. Not only La Fayette’s own status was up for debate but also the legal status of his descendants.

We start off with the fairly simple, La Fayette had been made an honorary American citizen on August 06, 2002 (that is the date where President George W. Bush signed the resolution, the bill however had been first introduced on April 24, 2001, you can find the timeline of the bill here.)

The Congress of the United States has a very detailed (and research-friendly) free online archive. You can read the wording of the original bill here and here you can see the amendments that were made. The speeches and procedures that accompany the bill the day it was passed in the House of Representatives are to be found here.

Here is the text of the resolution for everybody who has no interest or time to go through my jungle of links :-)

Joint Resolution

Conferring honorary citizenship of the United States posthumously on Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Whereas the United States has conferred honorary citizenship on four other occasions in more than 200 years of its independence, and honorary citizenship is and should remain an extraordinary honor not lightly conferred nor frequently granted;

Whereas Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette or General Lafayette, voluntarily put forth his own money and risked his life for the freedom of Americans;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette, by an Act of Congress, was voted to the rank of Major General;

Whereas, during the Revolutionary War, General Lafayette was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine, demonstrating bravery that forever endeared him to the American soldiers;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette secured the help of France to aid the United States' colonists against Great Britain;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette was conferred the honor of honorary citizenship by the Commonwealth of Virginia and the State of Maryland;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette was the first foreign dignitary to address Congress, an honor which was accorded to him upon his return to the United States in 1824;

Whereas, upon his death, both the House of Representatives and the Senate draped their chambers in black as a demonstration of respect and gratitude for his contribution to the independence of the United States;

Whereas an American flag has flown over his grave in France since his death and has not been removed, even while France was occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II; and

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette gave aid to the United States in her time of need and is forever a symbol of freedom: Now, therefore, be it

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, is proclaimed posthumously to be an honorary citizen of the United States of America.

Now, this honorary citizenship does only involve La Fayette himself. His heirs have nothing to do with this act. It does however acknowledge that La Fayette had already been made a citizen by the state of Maryland and the Commonwealth of Virginia (they left out the, somewhat questionable, declarations by the State of Connecticut and the State of Massachusetts.) Let us therefor go back to the 18th century and have a look at both of these resolutions. First is Maryland:

The General Assembly of the state of Maryland passed the following resolution on December 28, 1784.

CHAP. XII.

An ACT to naturalize major-general the marquis de la Fayette and his heirs male for ever.

WHEREAS the general assembly of Maryland, anxious to perpetuate a name dear to the state, and to recognize the marquis de la Fayette for one of its citizens, who, at the age of nineteen, left his native country, and risked his life in the late revolution; who, on his joining the American army, after being appointed by congress to the rank of major-general, disinterestedly refused the usual rewards of command, and sought only to deserve what he attained, the character of patriot and soldier; who, when appointed to conduct an incursion into Canada, called forth by his prudence and extraordinary discretion the approbation of congress; who, at the head of an army in Virginia, baffled the manœuvres of a distinguished general, and excited the admiration of the oldest commanders; who early attracted the notice and obtained the friendship of the illustrious general Washington; and who laboured and succeeded in raising the honour and the name of the United States of America: Therefore,

II. Be it enacted, by the general assembly of Maryland, That the marquis de la Fayette, and his heirs male for ever, shall be, and they and each of them are hereby deemed, adjudged, and taken to be, natural born citizens of this state, and shall henceforth be entitled to all the immunities, rights and privileges, of natural born citizens thereof, they and every of them conforming to the constitution and laws of this state, in the enjoyment and exercise of such immunities, rights and privileges.

Interesting piece of legislature, we are now not only talking about La Fayette but also about “his male heirs forever” - keep that in mind for later. On to Virginia:

The Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, yr. 1781-1786 states for Thursday, December 16, 1784:

Ordered, That leave be given to bring in a bill “for the naturalisation of the Marquis De la Fayette;” and that Messr. Henry Lee, and Turberville, do prepare and bring in the same.

We can read for Monday, October 31, 1785:

Mr. Henry Lee presented, according to order, a bill, “for the naturalisation of the Marquis De la Fayette;” and the same was received and read a first time, and ordered to be read a second time.

We can further read on that day that:

A bill, "for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette;" was read the second time, and ordered to be com- mitted to a committee of the whole House immediately. The House, accordingly, resolved itself into a committee of the whole House, on the said bill ; and after some time spent therein, Mr. Speaker resumed the chair, and Mr. Braxton reported, that the committee had, according to order, had the said bill under their consideration, and had gone through the same, and made several amendments thereto, which he read in his place, and afterwards delivered in at the clerk's table, where the same were again twice read, and agreed to by the House.

The next day, on Tuesday, November 1, 1785, we can read in the Journal:

An engrossed bill. “for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette;" was read the third time.

Resolved, That the bill do pass; and that the title be, "an act, for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette.'”

Ordered, That Mr. Henry Lee do carry the bill to the Senate, and desire their concurrence.

On Friday, November 11, 1785 we can read:

A message from the Senate by Mr. Harrison

Mr. Speaker, — The Senate have agreed to the bill (…) “for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette;" (…) And then he withdrew

And finally on Saturday, January 7, 1786 we can read:

The Speaker signed the following enrolled bills: (…) “An act, for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette."

At this point now we have two citizenships, one of them including his male heirs - so why was there any need for the honorary citizenship of 2002? I let Mr. Sensenbrenner, from the Committee on the Judiciary, who also submitted the amendments to the 2002 bill, explain it:

The Marquis de Lafayette was granted citizenship by the States of Maryland and Virginia before the Constitution was adopted. In 1935, a State Department letter addressed the question of whether the citizenship conferred by these States could be interpreted to have ultimately resulted in the Marquis de Lafayette being a United States citizen. Their determination was that it did not. The State Department provided an excerpt from the Journals of the Continental Congress in 1784 which stated in the Congress' farewell to the Marquis that ``as his uniform and unceasing attachment to this country has resembled that of a patriotic citizen of the United States . . . [emphasis added]'' as proof that the citizenship was not considered to have translated to a Federal level.

Simply speaking, a “state citizenship” does not equal a “real American citizenship”. Nevertheless, two decadents of La Fayette tried to obtain an American citizenship by using the Maryland resolution. Count René de Chambrun in 1932 and Count Edward Perrone di San Martino a few years later – I think the years was 1935 and he was the reason the State Department wrote their letter. As you all can very well imagine, both men were denied. Beside the rather obvious reason for their denial, the descendants were faced with even more legal obstacles. They had to rely solely on the Maryland resolution. That resolution was passed in 1784 under the Articles of Confederation. This set of laws was replaced on March 4, 1789 by the United States Constitution. Some people argue that La Fayette and all his male heirs born up until March 4, 1784 were made US citizens by the Maryland resolution but new citizenships could not be granted to any male heirs born after the Constitution became effective, because the Maryland resolution was passed under the Articles of Confederation and not under the Constitution. Some people argue however, that the Constitution still provides the same legal margin for a citizenships according to the Maryland resolution.

It furthermore has to be taken into consideration, that the term “and his heirs male forever” generally implies that there has to be an uninterrupted line of male decadents and heirs. From father to son to grand-son, great-grandson and so on and so forth. The problem is, that the male line of the La Fayette’s died out quite some time ago. La Fayette himself had one son, Georges Washington Louis Gilbert de La Fayette. He in turn had two sons of his own. Oscar Gilbert Lafayette and Edmond de La Fayette. None of them had any surviving male children of their own.

But these two incidents were not the only times that trouble and uncertainty arose from the States grant of citizenship - far from it. When La Fayette was arrested during the French Revolution by the Austrian troops, he tried to avoid imprisonment by declaring himself an American citizen. Neither the Austrians nor the Prussians bought into that and the Americans were also a bit uneasy about La Fayette’s claim. Later, when Adrienne send her son Georges Washington de La Fayette over to America, she wrote a very “subtle” letter, reminding the American people that her son was included in the resolution from Maryland. Meanwhile, James Monroe, the American ambassador to France at the time, had obtained passports for Adrienne and her two daughters to travel to America as well. The papers were for “Mrs. Motier of Hartford, Connecticut”. Here is the catch; the town of Hartford in Connecticut (not the state itself, only that single town) had declared La Fayette and his entire family as citizen. The passports were made on a very shaky legal ground and Monroe was fully aware of that - but he simple did not care, nor did anybody else. They wanted to help the family and if questionable passports were the way to go, so be it.

So there you have it. La Fayette was made a citizen of the United States only once, but he was made twice the citizen of different States.

#lafayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#general lafayette#historical lafayette#france#america#2002#1782#1785#1786#1824#1789#american revolution#american history#french history#history#house of representatives#united states senate#congress#george w bush#honorary citizenship#legal#articles of confederation#united states constitution#georges washington de lafayette#oscar gilbert de lafayette#edmond de la fayette#maryland#virginia

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Maria de Salinas was lady-in-waiting to Katherine of Aragon, and one of her closest confidantes. Although we know little of her origins, she was the daughter of Juan de Salinas, secretary to Katherine’s eldest sister, Isabella, and Josepha Gonzales de Salas. Despite the fact that she was not on the original list of ladies, drawn up in 1500, chosen to accompany Katherine of Aragon to England for her marriage to Prince Arthur, it seems likely that she, and her sister Inez, did come to England with the Spanish princess. She may have been added to the princess’s staff when her mother, Isabella of Castile, increased the size of Katherine’s entourage in March 1501.

Maria was one of the ladies who stayed with Katherine after her household was reduced and many returned to Spain, following the death of Katherine’s young husband, Arthur, Prince of Wales, in 1502. She stayed with the Spanish princess throughout the years of penury and uncertainty, when Katherine was used as a pawn by both her father, Ferdinand, and father-in-law, Henry VII, in negotiations for her marriage to Prince Henry, the future Henry VIII; a marriage which was one of Henry’s first acts on his accession to the throne. Maria is included in the list of Katherine’s attendants who were given an allowance of black cloth for mantles and kerchiefs, following the death of Henry VII in 1509; she was then given a new gown for Katherine’s coronation, which was held jointly with King Henry in June of the same year.

In 1511 Maria stood as godmother to Mary Brandon, daughter of Charles Brandon – one of the new king, Henry VIII’s closest companions and her future son-in-law – and his first wife, Ann Browne. Katherine of Aragon and Maria were very close; in fact, by 1514 Ambassador Caroz de Villagarut, appointed by Katherine’s father, Ferdinand of Aragon, was complaining of Maria’s influence over the queen. He accused Maria of conspiring with her kinsman, Juan Adursa – a merchant in Flanders with hopes of becoming treasurer to Philip, prince of Castile – to persuade Katherine not to cooperate with the ambassador. The ambassador complained: ‘The few Spaniards who are still in her household prefer to be friends of the English, and neglect their duties as subjects of the King of Spain. The worst influence on the queen is exercised by Dona Maria de Salinas, whom she loves more than any other mortal.’¹

Maria was naturalised on 29th May, 1516, and just a week later, on 5th June she married the largest landowner in Lincolnshire, William Willoughby, 11th Baron Willoughby de Eresby. William Willoughby was the son of Sir Christopher Willoughby, who had died c.1498, and Margaret, or Marjery, Jenney of Knodishall in Suffolk. He had been married previously, to Mary Hussey, daughter of Sir William Hussey, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench. The King and Queen paid for the wedding, which took place at Greenwich, the Queen even provided Maria with a dowry of 1100 marks. They were given Grimsthorpe Castle, and other Lincolnshire manors which had formerly belonged to Francis Lovel (friend of Richard III), as a wedding gift. Henry VIII even named one of his new ships the Mary Willoughby in Maria’s honour.

Maria remained at court for some years after her wedding, and attended Katherine at the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520. Henry VIII was godfather to Maria and William’s oldest son, Henry, who died in infancy. Another son, Francis, also died young and their daughter Katherine, born in 1519, would be the only surviving child of the marriage. Lord Willoughby died in 1526, and for several years afterwards Maria was embroiled in a legal dispute with her brother-in-law, Sir Christopher Willoughby, over the inheritance of the Willoughby lands. Sir Christopher claimed that William had settled some lands on Maria which were entailed to Sir Christopher. The dispute went to the Star Chamber and caused Sir Thomas More, the king’s chancellor and a prominent lawyer, to make an initial redistribution of some of the disputed lands.

This must have been a hard fight for the newly widowed Maria, and the dispute threatened the stability of Lincolnshire itself, given the extensive lands involved. However, Maria attracted a powerful ally in Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk and brother-in-law of the King, who called on the assistance of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Henry’s first minister at the time, in the hope of resolving the situation. Suffolk had managed to obtain the wardship of Katherine Willoughby in 1528, intending her to marry his eldest son and heir Henry, Earl of Lincoln, and so had a vested interest in a favourable settlement for Maria. This interest became even greater following the death of Mary Tudor, Suffolk’s wife, in September 1533, when only three months later the fifty-year-old Duke of Suffolk married fourteen-year-old Katherine, himself.

Although Suffolk pursued the legal case with more vigour after the wedding, a final settlement was not reached until the reign of Elizabeth I. Suffolk eventually became the greatest landowner in Lincolnshire and, despite the age difference, the marriage does appear to have been successful. Katherine served at court, in the household of Henry VIII’s sixth and last queen, Katherine Parr. She was widowed in 1545 and lost her two sons – and heirs – by the Duke, Henry and Charles, to the sweating sickness, within hours of each other in 1551. Katherine was a stalwart of the Protestant learning and even invited Hugh Latimer to preach at Grimsthorpe Castle. It was she and Sir William Cecil who persuaded Katherine Parr to publish her book, The Lamentacion of a Sinner in 1547, demonstrating her continuing links with the court despite her first husband’s death. Following the death of her sons by Suffolk, Katherine no longer had a financial interest in the Suffolk estates, and in order to safeguard her Willoughby estates, Katherine married her gentleman usher, Richard Bertie.

The couple had a difficult time navigating the religious tensions of the age and even went into exile on the Continent during the reign of the Catholic Queen, Mary I, only returning on Elizabeth’s accession. Katherine resumed her position in Tudor society; her relations with the court, however, were strained by her tendency towards Puritan learning. The records of Katherine’s Lincolnshire household show that she employed Miles Coverdale – a prominent critic of the Elizabethan church – as tutor to her two children by Bertie, Susan and Peregrine. Unfortunately, Katherine died after a long illness, on 19th September 1580 and was buried in her native Lincolnshire, in Spilsby Church.

A widow since 1526, Maria de Salinas, Lady Willoughby, kept a tight rein on the Willoughby lands,proving to be an efficient landlady. Unfortunately, the fact she took advantage of the dissolution of the monasteries in order to lease monastic land; a business arrangement, rather than political or religious, but it still made her a target of discontent during the Lincolnshire Rising.

Maria had remained as a Lady-in-Waiting to Katherine. She was known to dislike Anne Boleyn and, as Henry’s attitude towards Katherine hardened during his attempts to divorce her, in 1532 Maria was ordered to leave Katehrine’s household and not contact her again. By 1534, as Emperor Charles V’s ambassador, Chapuys, described it; Katherine was ‘more a prisoner than before, for not only is she deprived of her goods, but even a Spanish lady who has remained with her all her life, and has served her at her own expense, is forbidden to see her.’²

When Katherine was reported to be dying at Kimbolton Castle, in December 1535, Maria applied for a license to visit her ailing mistress. She wrote to Sir Thomas Cromwell, the King’s chief minister at the time, saying ‘for I heard that my mistress is very sore sick again. I pray you remember me, for you promised to labour with the king to get me licence to go to her before God send for her, as there is no other likelihood.’² Permission was refused, but despite this setback, Maria set out from London to visit Katherine at Kimbolton Castle, arriving on the evening of New Years’ Day, 1536 and contrived to get herself admitted by Sir Edmund Bedingfield by claiming a fall from her horse meant she could travel no further. According to Sarah Morris and Nathalie Grueninger, Katherine and Maria spent hours talking in their native Castilian; the former queen died in Maria’s arms on 7th January 1536.³ Katherine of Aragon was buried in Peterborough Cathedral on 29th January, with Maria and her daughter, Katherine, in attendance.

Maria herself died in May 1539, keeping control of her estates to the very last. She signed a copy of the court roll around 7th May, but was dead by the 20th, when Suffolk was negotiating for livery of her lands. Her extensive Lincolnshire estates, including Grimsthorpe and Eresby, passed to her only surviving child, Katherine and her husband, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. Maria’s burial-place is unknown, though there is a legend that she was buried in Peterborough Cathedral, close to her beloved Queen Katherine.”

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The discriminatory legislation against foreigners had as its main target the recent Jewish immigrants, symbolic embodiments of economic liberalism and political tolerance. The governments of the 1930s, and into 1940, succumbed to pressure from the professional groups who were worried about that liberalism and economic competition. Not surprisingly, members of those groups and occupations that had sought protection from foreigners rather than face competition were the same people to be given advisory or executive roles by the Vichy regime on the issues of work permits and naturalisations.

Politicians arguing a policy of appeasement and concessions to Hitler, such as Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet, who on 6 December 1938 signed a declaration with his German counterpart, Joachim von Ribbentrop in Paris, that ‘peaceful and good neighbourly relations between France and Germany constituted one of the essential elements for general peace’, thought that Jews were a danger to that peace. French governments in the 1930s, especially in the two years before the war, fluctuated in their attitudes and policies on refugees. Policies of exclusion and discrimination, especially towards Jewish refugees, adopted in the last years of the Third Republic anticipated the more severe ones of the Vichy regime. 5Naturalised and foreign individuals were carefully identified and subjected to surveillance, and a central service of identity cards was set up. Already in 1933–4, Prime Minister Daladier spoke of refugees as the ‘Trojan horse of spies and subversives’. They could be sent to ‘assigned residences’. Five years later, in 1938, his government restricted entry of immigrants and increased police surveillance over those already in France. French police in May 1938 were given power to fine and even imprison illegal immigrants and instructed to send back Jews trying to escape from Germany. Special border police were given this task. Undesirable foreigners without residence or work permits could be expelled. More internment camps were set up. The Minister of the Interior, Albert Sarraut, in May 1938 ordered the police not to renew identity cards of foreign merchants and artisans wanting to remain in France. A month later, on 17 June 1938, another decree regulated the number of foreigners who could engage in commerce and industry. To start a business, foreigners needed a carte de commerçant from the police, and this required consultation with local Chambers of Commerce, which were able to set quotas on the number of foreigners to be allowed into a specific commercial area. A law of 5 April 1935 had obliged foreign garment workers to get an artisan’s card, which had to be approved by local craftsmen’s associations. In November 1938, naturalised foreigners were forbidden to vote until they had been citizens for five years. Prefects in certain départements of France were given power to expel foreigners with improper papers. Foreigners who had been naturalised could be deprived of French nationality if they were ‘unworthy of the title of French citizen’. Foreigners lacking residence or work permits could also be expelled or confined to detention centres. At first those confined in detention centres in 1938 were mostly Italian anti-fascists, Spanish republicans, fighters of the International Brigades in Spain, and later German Jews. For its own reasons the Communist Party was hostile to the refugees; its daily, L’Humanité, used the slogan ‘France for the French’. As a consequence, communist Jews in 1938 formed their own organisation, the Union des Sociétés Juives.”

- Michael Curtis, Verdict on Vichy

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Perhaps the subject, as well as the invocation of a temporal 'before', is constituted by the law as the fictive foundation of its own claim to legitimacy. The prevailing assumption of the ontological integrity of the subject before the law might be understood as the contemporary trace of the state of nature hypothesis, that foundationalist fable constitutive of the juridical structures of classical liberalism The performative invocation of a nonhistorical 'before' becomes the foundational premise that guarantees a presocial ontology of persons who freely consent to be governed and, thereby, constitute the legitimacy of the social contract.”

– Judith Butler, Gender Trouble

#storing this here so that i can come and wrap my head around it later#naturalisation of a subject before the law#thesis stuff#judith butler#butler#gender trouble#subject

0 notes

Photo

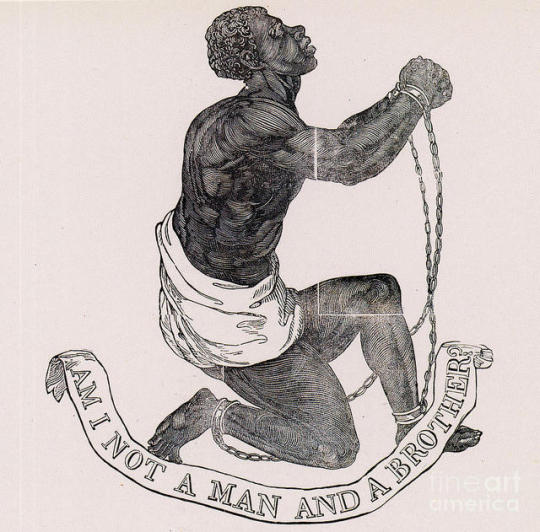

Speech by David Lammy, Labour MP

I am here, because you were there.

We are here, because you were there.

My ancestors were British subjects. But they were not British subjects because they came to Britain. They were British subjects because Britain came to them, took them across the Atlantic, colonised them, sold them into slavery, profited from their labour and made them British subjects. That is why I am here. That is why the Windrush generation are here.

I quote Martin Luther King, who himself quoted St Augustine, when he said that an unjust law is no law at all. So I say to the Minister: warm words mean nothing. Guarantee these rights and enshrine them in law.

And 230 years after the Abolitionist movement wore their medallions, I stand here as a Caribbean, Black, British citizen and I ask the Minister on behalf of thousands of Windrush citizens:

Am I Not a Man and a Brother?

My speech from the debate on the Windrush petition today:

I am proud to stand here on behalf of the 178,000 people who signed this petition.

I am proud to stand here on behalf of the 492 British citizens who arrived on HMT Empire Windrush from Jamaica 70 years ago.

I am proud to stand here on behalf of the 172,000 British citizens who arrived on these shores between the passage of the 1948 Nationality Act and the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, including my own father who arrived from Guyana in 1956.

But it is a very dark episode in our nation’s history that this petition was even required.

It is a very dark day indeed that we are here in Parliament having to stand up for the rights for people who have always given so much to this country and expected so little in return.

We need to remember our history. In Britain when we talk about slavery we tend to just talk about its abolition.

The Windrush story does not begin in 1948. The Windrush story begins in the 17th century, when British slave traders stole 12 millions Africans from their homes, took them to the Caribbean, sold them into slavery to work on plantations.

The wealth of this country was built on the backs of the Windrush generation’s ancestors.

We are here, because you were there.

My ancestors were British subjects. But they were not British subjects because they came to Britain. They were British subjects because Britain came to them, took them across the Atlantic, colonised them, sold them into slavery, profited from their labour and made them British subjects. That is why I am here. That is why the Windrush generation are here.

There is no British history without the history of the Empire.

As Stuart Hall put it: “I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea.”

And then 70 years ago as Britain lay in ruins after the Second World War the call went out to the colonies from the Mother Country. Britain asked the Windrush generation to come and rebuild the country. Work in our National Health Service. Work on the buses and the trains and as cleaners and security guards. So once again, labour was used.

They faced down the No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish signs. They did the jobs nobody else would do. They got spat on in the street. Assaulted by the Teddy Boys, the skinheads, the National Front. Spat at in the street. Lived 5 to a room in Rachmanite squalor. They were called and they served but my God did they suffer for the privilege of coming to Britain.

And yet my God they triumphed too. Sir Trevor McDonald. Frank Bruno. Sir Lenny Henry. Jessica-Ennis Hill. National treasures.

Knights of the realm. Heavyweight champions of the world and Olympic champions wrapped in the British flag. Sons and daughters of the Windrush generation, as British as they come.

And after all of this the Government wants to send us back across the ocean. They want to make life “hostile” for the Windrush children. They strip them of their rights, they deny them healthcare, they kick them out of jobs, they make them homeless, they stop their benefits.

And they are imprisoned in their own country. Centuries after their ancestors were shackled and taken across the ocean in slave ships, pensioners are imprisoned in their own country.

It is a disgrace. And it happened here because we don’t remember our history.

Last week the Prime Minister at Prime Minister’s Questions the Prime Minister said: “We owe it to them and the British people”.

The Home Secretary said that the Windrush generation should be considered British. That they should be able to get their British citizenship if they so choose.

This is the point the Government simply still do not understand. The Windrush generation ARE the British people. They ARE British citizens. They came here as citizens. That is the precise reason why this is such an injustice. Their British citizenship is, and has always been, theirs by right. It is not something that the Government is now choosing to grant them.

Can I remind the Government of Chapter 56 of the 1948 British Nationality Act.

Every person who under this Act is a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies shall by virtue of that citizenship have the status of a British subject.

The Bill uses the term British nationality by virtue of citizenship.

I read this Bill again last week when reading over the case notes of my constituents caught up in the Windrush crisis.

Patrick Henry. A British citizen. Arrived in Britain in 1959. A teaching assistant who told me “I feel like a prisoner who has committed no crime” because he is being denied citizenship.

Clive Smith. A British citizen. Arrived here in 1964, showed the Home Office his school reports and still threatened with deportation.

Rosario Wilson. A British citizen. No right to be here because St Lucia became independent in 1979.

Wilberforce Sullivan. A British citizen. Paid taxes for 40 years. He was told in 2011 he was no longer able to work.

Dennis Laidley. A British citizen. Tax records going back to the 1960s. Denied a passport and unable to visit his sick mother.

Jeffrey Greaves. A British citizen. Arrived here in 1964. Threatened with deportation by the Home Office.

Cecile Laurencin. A British citizen. 44 years of National Insurance contribution letters, payslips and bank account details. Application for naturalisation rejected.

Huthley Sealey. A British citizen. Unable to claim benefits or access healthcare.

Mark Balfourth. A British citizen. Arrived here in 1962 aged 7. Refused access to benefits.

The Windrush generation have waited for too long for the rights that are theirs. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over. There comes a time when the burden of living like a criminal in your own country becomes too heavy to bear any longer. That is what we have seen in the last few weeks – an outpouring of pain and grief built up over many years.

And yet Government Ministers have tried to conflate this issue with illegal immigration.

On Thursday the Home Secretary said “I am personally committed to tackling illegal migration”, “making it difficult for illegal migrants to live here and removing people who are here illegally”.

Indeed, during her statement last Thursday the Home Secretary said “illegal” 23 times but did not even once say the word “citizen”.

This is not about illegal immigration. This is about British citizens. And frankly it is deeply offensive to conflate the Windrush generation with illegal immigrants to try to distract from the Windrush crisis.

This is about a hostile environment policy that blurs the lines between illegal immigrants and people who are here legally and even British citizens. This is about a hostile environment not just for illegal immigrants that but for anybody who looks like they could be an immigrant.

This is about a hostile environment that has turned employers, doctors, landlords and social workers into border guards.

The hostile environment is not about illegal immigration.

Increasing Leave to Remain fees by 238% in 4 years is not about illegal immigration.

The Home Office making profits of 800% on standard applicants is not about illegal immigration.

The Home Office sending back documents unrecorded in second class post so passports, birth certificates and education certificates get lost is not about illegal immigration.

Charging teenagers £2,033 for limited leave to remain every 30 months is not about illegal immigration.

Charging someone £10,521 in limited leave to remain fees before they can even apply for indefinite leave to remain is not about illegal immigration.

Banning refugees and asylum seekers from working and preventing them from accessing public funds is not about illegal immigration.

Sending 9 immigration enforcement staff to arrest my constituent because the Home Office lost his documents is not about illegal immigration.

Locking my constituent up in Yarl’s Wood so she missed her Midwifery exams is not about illegal immigration.

Denying legal aid to migrants who are here legally is not about illegal immigration.

Changing the terms of young asylum seekers’ “immigration bail” so they cannot study is not about illegal immigration.

Sending immigration enforcement staff to a church in my constituency serving soup to refugees is not about illegal immigration.

The Home Secretary and the Prime Minister have promised compensation. They have promised that no enforcement action will be taken. They have promised that the “burden of proof” will be lowered when the taskforce is assessing Windrush cases.

The Windrush citizens don’t trust the Home Office and I don’t blame them. After so much injustice they need justice.

I quote Martin Luther King, who himself quoted St Augustine, when he said that an unjust law is no law at all. So I say to the Minister: warm words mean nothing. Guarantee these rights and enshrine them in law.

And 230 years after the Abolitionist movement wore their medallions, I stand here as a Caribbean, Black, British citizen and I ask the Minister on behalf of thousands of Windrush citizens:

Am I Not a Man and a Brother?

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apply for British Citizenship by Naturalisation

Get British citizenship

Get British citizenship. In the UK Naturalization is the legal process by which a person changes their nationality.

For decade upon decade foreign nationals living in the UK, and sometimes living abroad, have been able to attain British citizenship through naturalization.

From 1949, people in the British Commonwealth could register their British citizenship to remain British citizens – whether or not they actually moved to the UK. Up until 1949 citizens of any colony or dominion in the British Empire were automatically considered British subjects but this changed with the British Nationality Act 1948.People born in Ireland before 1949 were, likewise, considered British subjects and after the 1948 Act could also register British nationality; however, anyone born in the Republic of Ireland after 1948, seeking British citizenship, would need to apply to Naturalization.

Registrations ended in 1981 and from then on all foreign nationals, whether from the Commonwealth, former British colonies or any other country in the world, have had to apply for naturalization to become British citizens.

Get British citizenship as per UK laws individuals ought to be at least 18 years old and have been granted indefinite leave to remain or have acquired a right of permanent residence in the UK, you may be eligible to apply for British Citizenship by Naturalization.

What are the requirements for an application for Naturalisation as a British citizen?

Before Naturalization certificate is granted individuals must be able to meet the following requirements

In order to qualify for Naturalization as a British Citizen you must satisfy the Home Office that:

If married or in a civil partnership with a British citizen:

You were in the UK on the day 3 years before the date you submit your application;

You have not been absent from the UK for more than 270 days during the previous 3 year period;

You are not subject to any time limit on the period for which you may remain in the UK at the date of your application;

If not married or in a civil partnership with a British citizen:

You were in the UK on the day 5 years before the date you submit your application;

You have not been absent from the UK for more than 450 days during the previous 5 year period;

You are not subject to any limit on the period for which you may remain in the UK and have not been subject to any such time limit at any time during the 12 month period immediately preceding the date of your application;

You have not been in the UK in breach of the immigration laws at any time during that previous 3 or 5 years;

You have not been absent from the UK for more than 90 days during the previous 12 month period ;

You are not subject to any time limit on the period for which you may remain in the UK at the date of your application;

You are a person of good character;

You have sufficient knowledge of language and life in the UK;

You have suitable two referees for your British citizenship application.

Do I need to prove my knowledge of the English language if I am a fluent English speaker?

Yes. You can satisfy the knowledge of language requirement if you:

Are a national of a majority English speaking countries (Antigua and Barbuda; Australia; the Bahamas; Barbados; Belize; Canada; Dominica; Grenada; Guyana; Jamaica; New Zealand; St Kitts and Nevis; St Lucia; St Vincent and the Grenadines; Trinidad and Tobago; United States of America.);

Have a valid speaking and listening qualification in English at B1 CEFR or higher, that is on the Home Office’s list of recognised tests and was taken at an approved test centre ;

Have a degree obtained in the UK;

Have a degree certificate that was taught or researched in a majority English speaking country and an Academic Qualification Level Statement (AQUALS) from UK NARIC confirming the qualification is equivalent to a UK qualification;

Have a degree certificate that was taught or researched in a non majority English speaking country and: an Academic Qualification Level Statement (AQUALS) from UK NARIC confirming the qualification is equivalent to a UK qualification and o an English Language Proficiency Statement (ELPS) from UK NARIC showing that your degree was taught in English.

When will I receive a British passport?

You will not automatically receive British passport if your application for naturalization is successful. A naturalization application to become a British citizen is not the same as applying for a British passport, in fact it is the first step to eligibility for the issue of a British passport. You must submit your naturalization application to become British and, if successful, your naturalization certificate will then be used to apply for a British passport..

Check if you can become a British citizen

Dual citizenship

Citizenship ceremonies

Organise your citizenship ceremony with your council

British passport eligibility

Replace or correct a UK citizenship certificate

1 note

·

View note

Text

UK Citizenship - Important Guide

Introduction to UK Citizenship

"A person with Indefinite leave to remain or EU settled status can become British Citizens through a process widely known and recognised as Naturalisation. Naturalisation allows such person to acquire UK citizenship upon fulfilling the conditions laid down in the Immigration law

rules. In this article, we will explore the process of acquiring British citizenship through naturalisation".

What is on this page?

Introduction to UK Citizenship

Discretion, or Right for UK Citizenship

Naturalisation requirements for a married person

Life in the UK test

Criminal convictions

Naturalisation requirements for a non-married person

Withdrawal of UK Citizenship

Serious crime

Misleading information

Apply for naturalization

Fee for Naturalization

Frequently Asked Questions

Discretion, or Right for UK Citizenship

The grant of UK citizenship is discretionary which means that the Home Office is under no obligation to grant someone UK Citizenship. However, if the applicant fulfils the general requirement and is of a good character, he is likely to be granted with UK Citizenship. The important points to note are following;

The Home Secretary has the discretion to grant UK citizenship to a person who is not a British National.

The grant of British Citizenship is not fundamental Human right; however, every applicant has a right to have his application considered fairly. The Home Office generally provides the reasons for refusal as a good practice and to avoid unnecessary litigation including Appeals and Judicial Reviews.

The requirements to obtain British Citizenship are slightly different for a foreign national who is married to a British citizen or person with settled status (ILR).

Naturalisation requirements for a married person

Where the applicant is married to or in a civil partnership with a British citizen then he has to fulfil the following criteria;

The applicant must be settled at the time of the naturalisation application.

Must have been living in the UK for 3 years continuously before the application.

Must also be physically present in the UK on the exact date of the application but three years ago.

Must not be absent for more than 270 days in total during these qualifying three years and the applicant should not have spent more than 90 days outside from the UK in the year immediately before the application.

The Home Office may disregard 30 extra days when counting 270 days and 10 extra days when counting for 90 days in the preceding year.

The applicant must also have sufficient knowledge of the English language and must have passed the Life in the UK test

The applicant must also be of a good character. The applicant must disclose all criminal convictions both inside and outside the United Kingdom including Motoring or Road Traffic Offences, CCJs, Cautions, and Criminal Convictions.

English Language Requirement

The applicant can demonstrate the English language requirements by

Possessing the Home Office approved qualification or by passing a specific language test from the Home Office approved test centre/college.

Possessing a degree which is in line with the guidance of the Home office; or

by satisfying that the applicant belonged to a majority English speaking country; or

the applicant has already met the requirement when he/she has made an earlier, successful application for the indefinite leave to remain.

Life in the UK test

The Applicant must have a valid Life in the UK Test passed certificate in order to apply for UK Citizenship.

Naturalisation requirements for a non-married person

Where the applicant is neither married to nor in a civil partnership with a British citizen or person with an ILR, for such applicant the requirements

are following.

The applicant must be settled in the UK for at least one year before applying for naturalisation.

Must have been living in the UK legally for 5 continuous years at the time of the application.

Must also be physically present in the UK on the exact date of the application but 5 years ago.

Must not be absent for more than 450 days in total during these qualifying 5 years and applicant should also not have spent more than 90 days in the year immediately before the application.

The applicant must also have sufficient knowledge of the English language and knowledge of life in the UK.

The applicant must also be of a good character. The applicant must disclose all criminal convictions both inside and outside the United Kingdom including Motoring or Road Traffic Offences.

Must also have an intention to live in the United Kingdom.

Withdrawal of Citizenship

Home Secretary has the power to cancel or withdraw the citizenship of a person who has acquired British Citizenship through naturalisation or by registration, provided such a person is involved in the prohibited activities.

Serious crime

Where a person has committed a serious crime,including cases which involve national security, terrorism, serious organised crime, war crimes, etc. Home Office will likely withdraw the citizenship.

Misleading Information

Where a person has been naturalized due to misleading information or withheld necessary information at the time of application, it is likely that upon the discovery of such information the person will be deprived of British Citizenship and he will subject to deportation unless some extenuating circumstances exist.

Apply for Naturalisation

Online

You can apply online, click here

.

Paper Application

You can also apply through a paper application. The links to paper applications are given below.

Adult Naturalisation Application.

Child Naturalisation Application.

0 notes

Text

“In every democratic nation there are fascist political parties. Sometimes, they don’t have a lot of impact for a long time, but they do exist nevertheless. Fascists are people who are politically organised on the common ground that they see their own nation sold out by their own government. Sold out, because that very government allegedly governed their people in a wrong way, meaning they would admit “the wrong” people and would govern “our own” too laxly, which would undermine motivation and decency. Wherever governments strengthen the dependency on other countries by making trade agreements or forming political alliances because they count on a positive outcome for their nation, it’s the fascists who smell a sellout of the homeland.

This standpoint of fascists is kept alive and even strengthened by democratic parties. Every democratic party finds it reasonable to be sceptical about „foreigners“. Even where some might aim for a liberalisation of immigration law or for making naturalisation easier, it would still be stressed that this process should definitely depend on successful “integration” of these foreigners. It is taken for granted that foreigners always lack real patriotism – the one natives know before they are out of diapers. Every democratic party finds a lack of morale in the people, no matter if the occasion is a debate over fiscal evasion or on benefit scroungers. Every democratic party stresses that it only acts for the national common good when it, for example, signs an international treaty. Stressing that also means to hint at the other side of the medal: in any international business one's own national interests are at risk of being undermined by other nation-states. This is a prime subject of debate in parliamentary democracy: each party blames the others to have failed with regard to furthering the national interest or to even have thrown back the whole country by misgovernment. All those standpoints exist in every democracy. Fascists seize and radicalise them.

The EU and the Eurozone are associations of states each of which wants to advance its own power by joining together. Germany, for example, wanted to expand its already strong power in the world. Other nations, especially those in the south of Europe, wanted to get away from their agrarian economies and turn them into real capitalist ones. Both calculations seemed to have worked – until 2007.

The financial and sovereign debt crisis thwarted all of their plans. The countries in the European South had to subject themselves to a national scrappage programme simply for continued access to credit in Euro and without any perspective for further development. Germany does not want to pay a lot for those nation-states struck hardest by the crisis as they do not contribute to the German project of becoming a world power within and through a successful Europe.

In the public sphere it is the democratic parties which, at first, cast doubt whether everything worked according to plan in the past – in particular when they say: “carry on” regardless of the crisis. In contrast, fascist parties radicalised this doubt to the certainty that the whole EU and the Eurozone are one big sellout of the national interest.

The political elites have arrived at the conclusion that central political strategies have failed so far. This is one foundation of fascist success.

Secondly, for fascists parties to be successful it needs the people. Most people have no idea what the point of the Euro and its financial markets has been and continues to be. For the population it is patriotically obvious that painful cuts are required in the interest of the success of the nation when they think it is plausible that their own restrictions help the nation to achieve the greatness promised by politicians. For the same reason some countries saw mass protests because people do not accept that structural adjustment programmes lead the nation to greatness – as in their view those are merely imposed on them from abroad.

When large parts of the population now find it plausible to vote for fascist parties then this is not because they realised that nationally organised capitalism only means trouble for the satisfaction of needs and desires. But what they consider an inalienable right is the success of the nation itself. If that is threatened then they – as loyal subjects – become demanding and put their trust in parties which promise to stand for ruthless moralistic terror and systematic tightening of the figurative belt – without any concessions to foreign powers.

Antifascist activists remain helpless if they attempt to work with bourgeois parties and if they ignore their “arguments” (e.g. “foreigners and the EU are useful for the nation”) in coalitions – or even support these arguments. This bourgeois “invitation” not to follow the fascists contains the whole breeding ground for exactly these fascists. Instead what is needed is critique of those who judge the world around them – in good and bad times – as to how successful the nation is, instead of asking: what is my place, if others rule over me.”

- “Thesis on the swing to the right in Europe,” Gruppen Gegen Kapital und Nation.

#swing to the right#europe#european politics#fascism#european union#the nation#nationalism#capitalism#eurozone#far right#antifascism#crisis of 2008#financial crisis#eurozone crisis

1 note

·

View note

Text

NEW EEA REGULATIONS CHANGES FROM JULY 24, 2018

New EEA Regulations Changes from July 24, 2018

The most recent, and apparently last, changes to the EEA Regulations were laid before Parliament on 3 July 2018. The Immigration (European Economic Area) (Amendment) Regulations 2018 (SI 2018 No. 801) will come into constrain on 24 July 2018. Executing various cases chose by the Court of Justice of the European Union, the revisions roll out the accompanying improvements to the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016 (SI 2016 No. 1052).

Dual nationals

Since 2012, the Secretary of State has interpreted the case of C-434/09 McCarthy to mean that British citizens who also hold the nationality of another EU country cannot rely on the EEA Regulations when sponsoring their family members. Unless they could use the so-called Surinder Singh route, dual British/EU citizens had to rely on (more restrictive) British domestic rules to sponsor their family members.

In the case of C-165/16 Lounes, the Court of Justice found instead that EU citizens who move to the UK and later naturalise as British retain their free movement rights under EU law, even though they have become British.

Colin wrote about the case here:

The Regulations are amended to reflect the judgment in Lounes. Dual nationals can rely on EU law so long as they exercised treaty rights before naturalising as British citizens. Ideally this category of dual nationals would still be able to rely on this more generous rule after Brexit, such that they may have their family members joining them under the EU Settlement Scheme. I am not overly optimistic retaining self-employed status.

This change comes following the Court of Justice decision in C-442/16 Gusa, discussed by Tom here. The conditions where an EEA citizen can retain self-employed status are brought into line with the conditions under which an EEA citizen can retain worker status. The advantage of being able to keep self-employed status is that the person is considered to be “exercising treaty rights”.

That means they continue to live lawfully in the UK, have access to certain benefits, are able to have family members join them in the UK, and can count time towards the five years’ residence needed to acquire permanent residence.

Self-employed EEA citizens can now retain that status where:

They are temporarily unable to work as self-employed as the result of an illness or accident

They are in “duly recorded involuntary unemployment” after having been self-employed persons, provided that they:

Registered as jobseekers

Entered the UK as self-employed or to seek self-employed work, or were in the UK seeking employment or self-employment immediately after having enjoyed a right to reside as self-employed, self-sufficient or student

Provide evidence of seeking employment or self-employment and having a genuine chance of being engaged

They are involuntarily no longer self-employed and are doing vocational training, or

They voluntarily stopped being self-employed in order to do vocational training related to their previous occupation

Those seeking employment who have already worked for a year as self-employed can retain status for longer than six months where they provide compelling evidence of continuing to seek employment and having a genuine chance of being engaged. Those who worked for less than one year can only retain their status for a maximum of six months.

Of course, if the reassurances given by the British government materialise, EU nationals will not be asked to prove that they have exercised treaty rights in the UK to be able to remain living here after Brexit. So if all goes well, this change will have a very small impact, and for a very short amount of time only.

These changes are somewhat late, in that they give effect to the 2014 case of C-456/12 O and B. This was about the “Surinder Singh route”.

That allows non-EU family members of British citizens to rely on the more generous EU rules on coming to join their loved one in the UK where:

The British citizen was exercising treaty rights in another EEA country or acquired the right to permanent residence there

The applicant and the British citizen resided together in that other EEA country

Their residence in the EEA country was genuine

The Regulations are amended such that, in addition to the above, an applicant relying on this route must show that they were the family member of the British citizen in the other EEA country, and genuine family life was created or strengthened during their joint residence there.

Exclusion and deportation orders

Changes are made to the Regulations such that a person who is subject to an exclusion or a deportation order under the EEA Regulations does not have:

A right of admission

An initial right of residence

An extended right of residence, or

A permanent right of residence

Someone who is subject to such an order and applies for a family permit or residence document will have their application deemed invalid. These changes should only apply to people who have an exclusion or deportation order under EU law, rather than under British domestic rules.

In fact, in the case of C-82/16 K.A. & Others v Belgium, discussed by Bilaal here, the Court of Justice found that applicants who are subject to an entry ban under national law cannot be precluded from applying for a right to reside under EU law.

Primary carers of EEA nationals

The EEA Regulations provide for some primary carers of EEA nationals to obtain rights to reside in the UK. Under the EEA Regulations 2016, one of the criteria to be considered a primary carer was to be the sole carer or to share the care equally with someone who was not an “exempt person”.

An exempt person is someone with the right to reside under the EEA Regulations, the right of abode or indefinite leave to remain in the UK. In other words, if Laura, an Argentinian national, was sharing the responsibility to care for Judith, a British national, with Judith’s father, a French national exercising treaty rights, then Laura could not be considered a primary carer under European law.

Following the case of C-133/15 Chavez-Vilchez and others (discussed by Colin here), the definition of primary carer is widened. It now includes those who share responsibility equally with someone else, even if that someone is an “exempt person”.

Deportation and permanent residence

I recently wrote about the case of C-424/16 Vomero. The Court of Justice found that where an EEA national has resided in the UK for ten years, they must have acquired the right to permanent residence before being entitled to the enhanced protection against expulsion. The Regulations are amended to make that clear.

Other amendments

Other minor amendments to the Regulations include that:

When a family member applies for an EEA family permit or residence document, they must also submit the EEA national’s identity card and passport. I am unclear how this constitutes a change as this has in fact been the case for a while in guidance and applications were rejected when the identity document of the EEA national was not submitted.

EEA family permits can be issued in an electronic format. There is an illumination in the matter of when a man must be outside the UK to bring an EEA offer. Obviously, to what extent those progressions will stay significant is yet to be seen. We can dare to dream that the positive changes, including for essential carers and double nationals, will re-show up in the residential principles on EEA nationals and their relatives after Brexit.

See Related Articles:

UK DEPORTATION: HOW TO CHALLENGE IT?

UK VISIT VISA: AN OUTLINE

TOP 10 FACTS POST-BREXIT IMMIGRATION SYSTEM

UK NEW VISA FEE 8 OCTOBER 2018

IMMIGRATION BAIL: WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

0 notes

Quote

This standpoint of fascists is kept alive and even strengthened by democratic parties. Every democratic party finds it reasonable to be sceptical about „foreigners“. Even where some might aim for a liberalisation of immigration law or for making naturalisation easier, it would still be stressed that this process should definitely depend on successful “integration” of these foreigners. It is taken for granted that foreigners always lack real patriotism – the one natives know before they are out of diapers. Every democratic party finds a lack of morale in the people, no matter if the occasion is a debate over fiscal evasion or on benefit scroungers. Every democratic party stresses that it only acts for the national common good when it, for example, signs an international treaty. Stressing that also means to hint at the other side of the medal: in any international business one's own national interests are at risk of being undermined by other nation-states. This is a prime subject of debate in parliamentary democracy: each party blames the others to have failed with regard to furthering the national interest or to even have thrown back the whole country by misgovernment. All those standpoints exist in every democracy. Fascists seize and radicalise them.

Thesis on the swing to the right in Europe

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hurt at being labelled Pakistanis, Shaheen Bagh protesters tell SC - india news