#new left

Text

all-campus joint struggle committee (zenkyoto 全共闘) action

in KIDS ON THE SLOPE (2012) dir. shinichiro watanabe, MAPPA/tezuka productions

in their eyes, i'm a traitor. they may never forgive me. but all i can do is search in my own way from now on, using a different method from them.

#doesn't everyone's nearly-BL josei briefly become a nagisa oshima movie#sakamichigif#kids on the slope#sakamichi no apollon#mappa#shinichiro watanabe#♅#anigif#zenkyoto#japanese new left#shin-sayoku#fyanimegifs#fyeahanimegifs#dailyanime#animeedit#anisource#dailyanimatedgifs#animangahive#new left#queue attack my heart

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Covers of Internationale Situationniste journal, 1958-1963

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

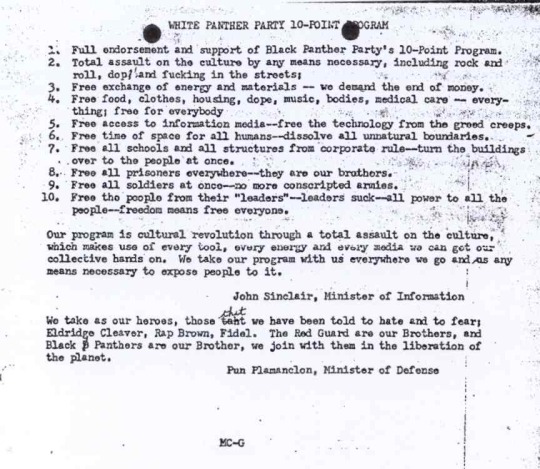

#White Panther Party#WPP#White Panthers#Rainbow Coalition#MC5#John Sinclair#Black Panther Party#Fred Hampton#outlaws and partisans#New Left#60s#1960s#Communist#Communism#Marxist#Marxism

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It is Time to Return to the Future of The Red Years for Our Time.

The Red Years: Theory, Politics and Aesthetics of the Japanese ’68, edited by Gavin Walker, is a book that reconstructs three fundamental aspects of the Japanese ’68 revolution for us today:

Marxist and revolutionary theory, which was caught in a certain mode of crisis, but also in a mode of new possibilities for revolution and rebellion in the present;

Revolutionary politics of the Japanese ’68, i.e., the intersectional diversity of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist revolutionary practice in Japan led by student proletarians;

Radical aesthetics of, and for, revolutionary and emancipatory politics, which changed human perception in the fields of writing, painting, music, dance and theatre.

In what follows, I will focus on the first two points, but if there is an overarching and basic lesson of the book, it is this: “There is no guilt in revolution—to rebel is correct”. (235) Comrade Walker’s timely declaration repeats—and psychoanalytically grounds— Mao’s declaration to The Shanghai Workers’ Revolutionary Rebel General Headquarters in 1967. As the Chairman declared then: “In the last analysis, all the truths of Marxism can be summed up in one sentence: To rebel is justified.”

2.

Marxist theory occupied a central place in the Japanese ’68, and The Red Years discusses how it combined the inheritances of three, inter-related discourses of Marxist theory:

Japan’s interwar discourses of Marxist theory, epitomized by the Debate on Capitalism (“the Debate”), which spanned from 1927 to 1937;

The political economic theories, method and research of Uno Kōzō (1897-1977);

Marxist theory in the Soviet Union from 1919 to 1956, the latter year representing the critique of Stalin and the Hungarian rebellion.

Again, for the sake of brevity, I will focus on the first two points.

To recapitulate a familiar but still repressed story of the splitting of the Marxist Left in the interwar period in Japan: the split was expressed in the form of a Debate that distinguished two Marxists factions, which took opposing sides in relation to the Comintern Thesis of 1932 on the situation in Japan. The 1932 thesis called for overthrowing the feudal Emperor system in Japan as a precondition for a subsequent proletariat revolution, and also concluded that the Meiji Restoration of 1868 was not a bourgeois revolution, only an incomplete one. (Walker, 2016, Chapter 2).

Supporting the Comintern line was the Japanese Communist Party (JCP, founded in 1922), itself supported by the “Lectures faction” or Kōza faction (講座派) of Marxist scholars and researchers. Opposing the Comintern line, the JCP and the Kōza faction was the Rōnō faction (労農派). The Rōnō faction argued that the Meiji Restoration was effectively a bourgeois revolution and that the capitalist mode of production—especially in terms of the development of the commodity (and market) economy, or 商品経済— had been fully developed in Japan by the 1930s. They thus argued for a direct communist revolution and an immediate dictatorship of the proletariat, but also tended to ignore the idea of overthrowing the Japanese Emperor system.

As The Red Years clarifies, many of the theoretical and political positions from the interwar Debate were transplanted and transferred to the ’68 revolutionaries, and to their new historical conjuncture in the shadows of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaties, which placed Japan in the position of a ‘client state’ under U.S. imperialism. In the ’68 conjuncture, the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) and its youth league (Minsei) adopted the Kōza faction position; the Japanese Socialist Party (JSP) adopted the Rōnō faction position and was deeply influenced by the theories and research of the Japanese Marxist, Uno Kōzō. Finally, many of the New Left sects of the Zenkyōtō movement, who commonly opposed both the JCP and the JSP, were also influenced by Uno. But instead of taking Uno’s theories to parliament like the JSP, the New Left took Uno’s theories to the streets.

In The Red Years, Suga Hidemi gives a concise description of the discursive constellation of the Rōnō faction, Uno Kozo’s economic theories, and the New Left:

In the postwar years, the Rōnō faction’s argument became the position of the left wing of the Socialist Party (now known as the Social Democractic Party), which was to the Communist Party’s right. Insofar as it did not advocate the abolition of the emperor system, the Socialist Party could be considered a moderate social democratic party. Broadly speaking, Uno Kōzō’s economic theories…could be placed within the Rōnō faction ideology. Starting with the Bund, the question of how to interpret Uno’s economics was an important topic for the Japanese New Left. (102)

Further corroborating the impact of Uno Kōzō’s thought on the New Left, Hiroshi Nagasaki, author of the Theory of Rebellion, writes:

The influence of Uno’s political economy on the thought of the New Left was immense. On the one hand, as a method of political economy for disclosing the objective crises of capitalism anew, it provided powerful and independent thematics of economic analysis. It emphasized the need to write a new theory of imperialism. On the other hand, Uno’s theory of principle, by locating the motor-force of revolution outside the text of Capital, provided a conception of ‘freedom’ to practice. It was the opportunity in thought that allowed for the liberation of ‘rebellion’ from the Marxist theory of revolution. (Nagasaki, The Red Years, 37)

In this quotation, Nagasaki emphasizes three points of Uno’s method for political economy that were so meaningful for the New Left’s radical vision and practice in ‘68:

(1) Uno’s theory of the fundamental principles of political economy (i.e., Marx’s Capital)

(2) Uno’s theory of (the inevitability of) crisis

(3) Uno’s theory of imperialism (i.e., Lenin’s Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism)

Regarding the world of principles and its relation to practice, in Theory of Crisis (1953), Uno wrote:

What is clarified as a social principle is something that is expressed as if it can make society move and develop eternally. This means that what becomes a principle is something that is repeated, inevitably and necessarily. The historicity of a society’s birth, growth, and decline becomes hidden in the background, so to speak. Thus, when we provide the exposition of the principles of political economy, as a system that begins with the ‘commodity’ and ends with ‘all classes’, questions such as the birth of ‘commodities’ or the end of ‘classes’ cannot be answered by the systematic principles itself. Now, in Capital, when Marx on occasion explains the necessity of capitalism to transform into another kind of society, I do not believe that this problem can be solved by the systematic principles themselves. This, at least, is how I understand it. There is no reason and no way that the principles, in and of themselves, can provide an exposition of a society’s birth and death. (Uno, 1953, my translation)

For Uno, the question of theory and practice has three aspects. First, the question of theory is never assumed to be automatically unified with practice (politics), as in the phrase “the unity of theory and practice.” Uno instead separated theory from politics, and vice versa (and in a way that resonates with Althusser’s theoretical struggles within the French Communist Party in the 1960s-70s.)

Secondly, practice/politics is ultimately a question of overturning the world of capital’s principles from a position that represents the outside of capital, i.e., the position and movement of labor-power (Marx, 1990, Chapter 6; Kawashima, 2009; Walker, 2016, Chapter 4; Kawashima-Walker, 2019). This is Uno’s famous question of the commodification of labor power, its ‘im/possibility’, as well as its ‘negation’ or ‘sublation’, or 労働力商品化の「無理」•「止揚」. (Uno, 1953, 1958)

Thirdly, the autonomous place of politics is something that can be reached only by passing through three, distinct levels of political economic research and their attendant forms of knowledge (abstract-theoretical; historical; and concrete-empirical):

the theory of the purely abstract, fundamental economic principles of the capitalist mode of production, as theorized by Marx in Capital, also known as Uno’s 経済原理論;

the theory of the historical stages of capitalist development, or 段階論 and 経済政策論, which are based on the differences between the state economic policies of mercantilism (重商主義), liberalism (自由主義), and imperialism (帝国主義);

the concrete, historical analysis of capitalism after 1917, or the analysis of contemporary capitalism in its historical conjunctures, or 現状分析.

These are the three levels of Uno’s method for political economy. As such, they are the ‘precursors’, so to speak, of the emergence of the autonomy of politics. In the context of the Japanese ’68, Uno’s theoretical exposition of the world of capital’s principles had the dialectical effect of liberating thought and politics away from the purely economic principles of capital, and towards the invention of alternative modes of subjectivation, community, and political practice that were totally antithetical to the world of capital and its commodifying and oedipalizing principles of capitalist and imperialist sociality. In short, the political praxis of the Japanese ’68 began where Uno’s theoreticism ended. As Hiroshi Nagasaki writes in his On Rebellion:

We departed from the point where Uno consciously [i.e., logically] stopped. In other words, the radical theoreticism of Uno, which absolutely lacks actual relations with practice, in turn influenced our [political] practices [their autonomy]. (The Red Years, 209)

Echoing this line of thought, Yutaka Nagahara writes:

It is exactly the distinct, autonomous field of politics that must be questioned for its possibility, as Badiou did. This paradoxically resonates with Boltanski and Chiapello, who argue that ‘the history of the years after 1968 offers further evidence that the relations between the economic and the social…are not reducible to the domination of the second by the first.’ It is this ‘inversion’, so to speak, that ’68 made happen on the structured streets.” (The Red Years, 209)

3.

What happened to the Japanese ’68 after the event of ’68? The problem, as Nagahara quotes Badiou, is that, “We are commemorating May ’68 because the real outcome and the real hero of ’68 is unfettered neo-liberal capitalism.” (The Red Years, 207) Moreover, compounding the problem of neoliberalism, the defeats of the ’68 revolution have created a Left with a strong tendency to “overvalue the negative capability of remaining in doubt, skepticism and uncertainties”, which, according to Mark Fisher, has become a “political vice” of the Left that the New Right is more than happy to take neoliberal advantage of. (The Red Years, 231)

How can the Left today overcome this insecure doubt, skepticism, uncertainty, as well as its sad passions? The Red Years, it seems to me, alerts us of two important tasks that can, and must, be done to begin resolving these problems on the Left.

First Task: to develop further the open secret of the Japanese ’68 rebellions: that capitalism ‘works’ and ‘operates’ in the way that it does only because there is something intrinsic about capitalism that is fundamentally inoperable and broken. Any appearance of rationality in capitalism is only an illusory appearance (Schein) of capital’s exchange process based on the commodity-form, which itself is nothing but a salto mortale, or an irrational and speculative “leap of faith” from the relative form of value (‘20 yards of linen’) to the equivalent form of value (‘1 coat’). (Marx, 1990; Karatani, 2020) It is thus a mistake to think that the essence of capital can be explained as if it is a purely rational substance.

Therefore, it is never the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist rebels who are the mad ones. The anti-capitalist rebels are the normal and sane ones; it is capital, its representatives, agents, sycophants, saboteurs and spies—especially in the stage of imperialism—who are the stark and raving mad lunatics, hell-bent on deploying whatever irrational means of violence to realize absolute and relative surplus value for the dictatorship of capital. (Deleuze-Guattari, 1968)

Therefore, to believe that one can describe capital as if it is rationally structured will fail to realize the many ir/rational reasons why everyday people—who think—will repeatedly revolt against the dictatorship of capital, even in vain, if only to taste a little bit of real freedom. As Yutaka Nagahara writes:

Rational Marxian economics could demonstrate the structure of our reiterated defeats scientifically only because of the way in which it describes capital itself as rationally structured; but for that very reason, it can never imagine and therefore realize the (ir)rational reasons people revolt repeatedly in vain. (The Red Years, 182)

Second Task: To develop the revolutionary inheritances of the Japanese ‘68 in today’s depoliticized dead-end of neoliberal thought, it is necessary to re-articulate the critique of contemporary forms of eclecticism. This critique is necessary (once again, as it was for Lenin in the 1890s in Russia) because eclecticism prevents all of us from coming together as a unified combination of forces to overthrow capitalism.

Eclecticism today is a neoliberal way of thinking and living that makes everyone too timid to even dare to revolt against the existing conditions of capitalism. Eclecticism today is a sophisticated and pompous discourse of allowing the existing conditions of capitalism to be analyzed interminably, and thus to remain in place indefinitely and unchallenged. Today, eclecticism also commonly combines with Essentialism and Esotericism to produce a generalized depoliticization. For example, in today’s University discourse, “Latourian Object Analysis + Identity Politics + Neo-Heideggerian fundamental ontology = Eclecticism + Essentialism + Esotericism = Radical Depoliticization”.

Marxism and the Left today must smash such senseless, neoliberal eclecticism in order to begin to actualize the possibilities of socialist revolution that the Japanese ’68, for a brief moment, forced into existence.

As Lenin wrote in the 1890s: “The eclectic is too timid to dare to revolt… Let anyone name even one eclectic in the republic of thought who has proved worthy of the name rebel!” (quoted in The Red Years, 233)

Finally, to stamp out eclecticism amidst the crisis of neoliberal capitalism today requires, more than ever, nothing short of a renewed theory of the dictatorship of the proletariat. (Marx, 1875; Lenin, 1917; W.E.B. Dubois, 1935; Balibar, 1977).

Walker’s The Red Years identifies these important tasks (and more) as critical elements for the revolution to be accomplished for our time, daring us to renew a revolutionary and rebellious movement on the Left against the dictatorship of capital.

To rebel is correct and justified!

Smash Capitalism and its Neoliberal Eclecticism!

Labor-Power for the Dictatorship of the Proletariat!

Ken Kawashima

University of Toronto

- review of The Red Years: Theory, Politics, and Aesthetic in Japan’s ’68 in Praxis, February 24, 2021.

Image is Tseng Kwong Chi, New York, New York, 1979. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 16 inches. (For some reason Praxis or Prof. Kawashima tagged this review with Tseng’s work, so let’s go for it.)

#japanese marxism#marxism#marxist theory#may 1968#revolutionary theory#revolutionary politics#japanese communist party#japanese socialist party#uno kōzō#zenkyōtō#new left#communists#communism#capitalism#capitalist crisis#political economy

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passionate Patriots: 1968 DNC Nightmare in Chicago

.

Source:FRS FreeState

The Democratic Party cost themselves the presidential election of 1968 and a chance to win the White House for a third straight time and 8-10 presidential elections, going back to 1932 with FDR. To go along with another Democratic Congress because of how divided they were on the Vietnam War. A lot of that can be blamed on President Johnson’s handling of the Vietnam War, but…

View On WordPress

#1968#1968 Democratic National Convention#1968 Presidential Election#America#Anarchists#Anti-War Movement#Chicago#Communists#Counter-Culture#Democratic Party#Far Left#Hubert Humphrey#Illinois#Lyndon Johnson#New Left#Occupy Wall Street#Richard Daley#Socialists#Students For a Democratic Society#The 1960s#United States#Vietnam War

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do institutions and "the State" permit a tolerable degree of dissent because it allows them to self-correct, ensure self-continuity, and avert collapse?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

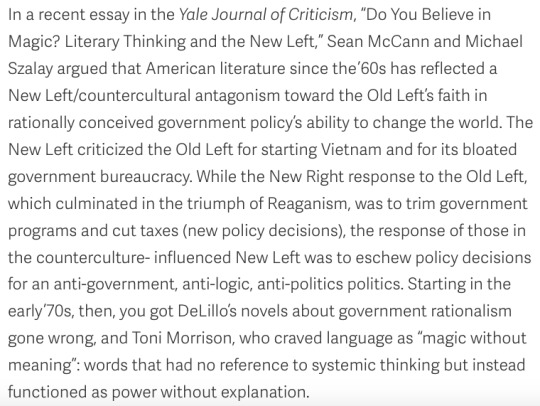

—Benjamin Nugent, "Why Don't Republicans Write Fiction?"

I found the above 2007 essay from n+1 by a circuitous route—I was essentially trying to decide if I should put Mark Helprin's Winter's Tale even on the long-range reading list—and admire the above paragraphs for articulating something I myself have been trying to say over the years about the inapplicability of the left-right distinction to the greatest works of modernist-postmodernist literature, about how if we can't appreciate the radical nature of T. S. Eliot and the reactionary nature of Toni Morrison, we're not going to understanding anything.

2007 was a long time ago. The Democratic Party is now the institutional heir to the neoconservatism of the Bush-era Republicans (for now), above all in its prostration toward the techno-security state or "deep state" that was such a major object of critique in New Left fiction from Dick to Pynchon to DeLillo. It's no surprise, therefore, that interesting fiction and culture in general, even in the teeth of current hegemonic left-liberalism's censorious turn as foreshadowed by McCann and Szalay's essay demanding political legibility and rationality from writers, has tended to come from those skeptical of this liberalism and aesthetically attracted to a populist right many of whose at least superficially anarchic convictions echo the now old New Left. This pendulum may swing again soon, however, with the rise of political figures like RFK Jr. (an actual throwback to New Left anti-authoritarianism on the left) and Ron DeSantis (a Bush-style neocon in unconvincing populist costume signalling the end of the Trumpian carnivalesque on the right).

P. S. Despite the progressive Nugent's magnanimity toward Helprin, Winter's Tale doesn't sound from the essay much like my type of novel. Please let me know, though, if I must read it.

#benjamin nugent#modernism#postmodernism#liberalism#leftism#conservatism#new left#mark helprin#t.s. eliot#toni morrison#literary criticism#american politics

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

there is a strong correlation between the radical consciousness and the regalia of the New Left — beards, long hair and clothing in disarray. By adopting its regalia, the follower of the New Left subjects himself to social ostracism that reinforces his notion that the system is oppressive, which stimulates his appreciation of the urgency for radical social change. It is therefore not coincidental that so many social reformers exhibit the regalia of social deviants.

Robert Griss ‘67, Daily Princetonian, March 7, 1967

#1960s#Students for a Democratic Society#SDS#Princeton#PrincetonU#Princeton University#New Left#fashion#Princetonfashion#quote#Princetonquote

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Bakunin’s central conflict with Marx was related precisely to the former’s conviction that an authoritarian revolutionary movement, as Marx espoused, would inevitably initiate an authoritarian society after the revolution. For Bakunin, if the new society is to be nonauthoritarian then it can only be founded upon the experience of nonauthoritarian social relations.

Jeff Shantz, Anarchist Futures in the Present

#dictatorship of the proleteriat#soviet#ssr#late stage capitalism#jeff shantz#shantz#shantz 2008#2008#anarchist futures in the present#bakunin#marx#anarchy#anarchism#anarchofeminism#new left

1 note

·

View note

Text

Source

Source

53K notes

·

View notes

Text

"ukraine invasion" vs "israel-hamas war" hm. something something wording and western media bias and propaganda

#this is the gaurdian btw#generally regarded as a reliable and relatively left news source. so#anyway other people have said it longer and better and you all know exactly what i mean#palestine#save palestine#free palestine#gaza#israel#ukraine#russia#mine

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas ’23, 1

Isaiah 7:14 (New International Version): Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel.

Isaiah 9:6-7 (New International Version)

6 For to us a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders.And he will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

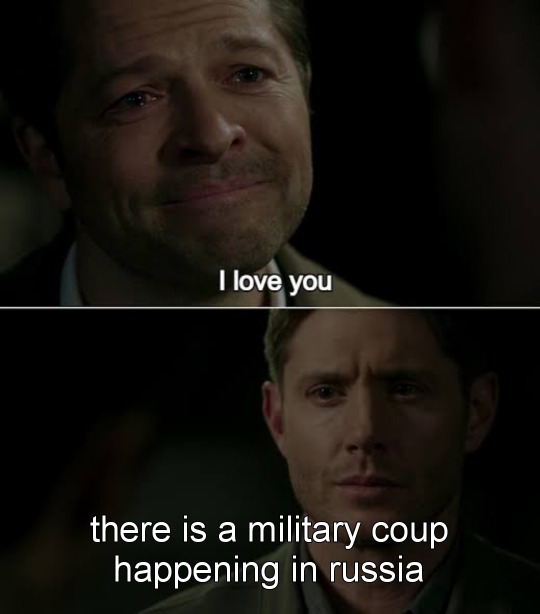

i didnt saw one of these so here is the news

#if russia is involved destiel cant be left outside#spn#supernatural#destiel#russia#russian politics#russia military coup#destiel news

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

"The ideology of the Canadian Farmworkers Union (CFU) stemmed from two related places. First, the CFU’s organizers were active members of the Indian People’s Association in North America (IPANA), formed in 1975 to promote social justice causes and to oppose imperialism around the world. IPANA was fundamentally a left-wing social organization that saw the support of the Canadian working class as necessary to overcoming the larger issue of racism. IPANA Vancouver members, such as Harinder Mahil and Charan Gill, would later join forces with Raj Chouhan to organize the CFU’s predecessor, the Farmworkers Organizing Committee (FWOC), in late 1978.

The tactics (demonstrations, meetings, and the production of educational material) and orientation (claiming to have won “the support of every progressive force and working class organization in North America, and of all Third World peoples’ organizations”) of IPANA has similarities to the larger New Left movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Historian Craig Heron characterizes the New Left as a different style of politics, one that uses direct action – what he terms “participatory democracy” – instead of electoral politics. This “participatory democracy” meant public demonstrations, marches, and other forms of what Heron terms “extraparliamentary confrontation” that engaged with social issues more directly than did the ballot box. Even though demonstrations were not new forms of protest, the issues and concerns of the New Left that were reminiscent of the Industrial Workers of the World from the early twentieth century marked a different path from that of their old left counterparts. While capital elites hailed mass production and the role of technology in a growing consumerist society, the New Left grew from a counterculture that identified this so-called progress as the origin of society’s woes. Further, the New Left sought for renewed militancy and radicalism within the contemporary labour movement, something that it felt was missing. This counterculture was particularly appealing to young workers and activists who were disenchanted by some of the bureaucratic ways of the old left.

The CFU then, should be considered a late product of New Left activism in British Columbia and in Canada more broadly. Many CFU organizers, such as Harinder Mahil, Charan Gill, and Raj Chouhan, would have been exposed to this counterculture in the Lower Mainland, with connections to university campuses and other unions during the 1970s. For the New Left and the leaders of the CFU, a focus on social issues was the cornerstone of their new style of unionism. Social movement unionism was one method of simultaneously combating racism and labour exploitation. As is evident in the affiliation debates at the CFU’s first national convention, the organizers wanted a more progressive union model to suit the unique social needs of its members."

- Nicholas Fast, "“WE WERE A SOCIAL MOVEMENT AS WELL”: The Canadian Farmworkers Union in British Columbia, 1979–1983," BC Studies. no. 217, Spring 2023. p. 38-40.

#canadian farmworkers union#indian people’s association in north america#new left#participatory democracy#union organizing#farm workers#agricultural workers#indian immigration to canada#immigrant workers#racialized workers#farming in canada#working class struggle#academic quote

0 notes

Text

Mitch: Video: Chicago 1968: The Democratic Convention

.

FreeState MD

1968 is when the Democratic Party changed and no longer became a Northeastern progressive party with a Southern coalition. Made up of people who basically make up the Religious-Right and Neoconservative wing of the Republican Party today. With Liberal Democrats spread out all over the country. By 1968 the Democratic Party was moving away from the South and becoming the party of the…

View On WordPress

#1968#1968 Chicago Convention#1968 Democratic National Convention#1968 Presidential Election#Anti-War Movement#Chicago#Chicago 1968#Counter-Culture#Democratic Party#Far Left#Green Party#Hubert Humphrey#Lyndon Johnson#New Left#Occupy Wall Street#Students For a Democratic Society#The 1960s#Vietnam War

3 notes

·

View notes