#nickel odeon

Text

Strangers When We Meet (Richard Quine, 1960)

Pocas veces ha contado la filmografía de un cineasta, de forma tan implícita como evidente, una historia en principio feliz pero de tan triste final como la de Richard Quine entre 1954 y 1962, es decir, desde que conoce y dirige por primera vez a la starlet de la Columbia Pictures Kim Novak, en Pushover (La casa nº 322), trágico thriller en blanco y negro inspirado en Double Indemnity (Perdición, 1944), de Billy Wilder, y con uno de sus principales intérpretes, Fred MacMurray, hasta que, ocho años más tarde, se despide de ella —en la pantalla—, de nuevo en blanco y negro tras un interludio de amor en color, pero esta vez en el marco algo amargo de una comedia negra policíaca y británica nada feliz y no del todo lograda, The Notorious Landlady (La misteriosa dama de negro), con Jack Lemmon, Fred Astaire y varias viejecitas tan estrafalarias como siniestras.

En medio hay dos verdaderas declaraciones de amor sobre celuloide y a todo color, la primera esperanzada, la comedia de misterio y fantasía, pero típicamente neoyorquina y realista al mismo tiempo, titulada Bell, Book and Candle (Me enamoré de una bruja, 1958), en la que Quine se anticipa unos meses a Vértigo (De entre los muertos), de Hitchcock, al emparejar a Kim Novak con el larguirucho James Stewart; la segunda, muy desesperanzada, es un pesimista melodrama de amargo final, coprotagonizado por Kirk Douglas, Strangers When We Meet (Un extraño en mi vida, 1960), muy minnelliano de paleta cromática y planteamiento, pero probablemente muy autobiográfico (sustitúyase al arquitecto que trabaja por encargo por el director bajo contrato con la Columbia).

No es esta crónica de un amor muy larga ni detallada, pues, sino elíptica y zigzagueante, como suelen serlo las mejores películas de este sensible y poco apreciado director —menos llamativo que su amigo Blake Edwards, menos brillante que Stanley Donen, que era el veterano del trío, aunque Quine fuera el mayor—, pero desde el primer plano de Kim Novak en Pushover, aunque nada sepamos de la relación que hubo entre ella y Quine, intuimos que no es que la actriz sea de una notable —y más bien pasiva— fotogenia, ni posea esa enigmática capacidad de fascinar a la cámara que tienen algunas mujeres, y de las que otras, incluso mejores intérpretes y hasta mucho más guapas, carecen, a veces por completo, sino que el director estaba ya prendado de ella. Hay algo en la manera de iluminarla y encuadrarla, de seguirla y hasta acariciarla con la cámara, que va más allá de cualquier hábil estrategia dramática de Quine para hacer que los espectadores comprendamos el hechizo que siente por ella el policía encarnado por MacMurray. A medida que avanza la historia, y se comprende que Kim es una de esas mujeres débiles que, casi sin proponérselo, resultan fatales para los hombres que se enamoran de ellas y están dispuestos a dejarse engañar por su aparente inocencia, queda de manifiesto que no se trata de eso, que el director, arrebatado, se está dejando llevar por su pasión, y que filma a la actriz más, más de cerca y durante más tiempo que el exigido por la economía narrativa de la película.

Cuatro años después, la comedia de John Van Druten adaptada por Daniel Taradash hace de Kim Novak una bruja actual e inocente, que fascina a Stewart y que, por amor hacia un hombre corriente y bastante mayor que ella, renuncia a sus poderes y se convierte en una simple humana, librándole así de su ominosa e insoportable prometida. Pocas veces una película ha mimado tanto a su protagonista, descubriéndole encantos recónditos, no evidentes a primera vista, revelando como timidez y miedo a hacer daño su aparente frialdad, insinuando que bajo su falta de expresividad habitual se esconden un fuerte sentido del humor y una obstinada fuerza de voluntad, complaciéndose en contemplar y proclamar su belleza, comparando —en un plano memorable— sus ojos con los de su gato Paywacket. A Quine no le basta ya con admirar en privado a su amada, necesita compartir su hallazgo, divulgar las excelencias de Kim Novak, sentirse ratificado en su buen gusto y, por tanto, envidiado por los restantes espectadores.

Me enamoré de una bruja es, sin duda, su película más extática y feliz, la más armoniosa, la única que da la sensación de que ese amor deducible de la puesta en escena era correspondido por el objeto de sus entusiastas atenciones.

Un extraño en mi vida es otra canción, mucho más conmovedora y melancólica, una de las películas que más me emocionan cada vez que la veo, y van unas veinticinco. Nunca estuvo Kim Novak tan realmente humana, tan física y al mismo tiempo tan frágil, ni tan guapa, ni siquiera en Vértigo, donde aparecía siempre excesivamente alienada y distante, salvo quizá en la escena de la bata, en casa de Scottie (James Stewart), después de sacarla de la bahía de San Francisco. Hay pasión y despecho, violencia y sufrimiento en cada plano. Y, para colmo, es evidente que Quine no puede renunciar a Kim, que se le va la mirada detrás de ella, que trata esta vez no ya de darla a conocer, sino de indagar en sus razones, de comprender qué ha pasado, por qué ha fracasado en la empresa que más le importaba.

Es una película verdaderamente romántica, febril y angustiada, triste y patética, sin mucho humor —y el que queda está teñido de amargura, como el personaje del escritor insatisfecho y alcohólico que encarna espléndidamente Ernie Kovacs— y derrotada, pero apasionada, enamorada todavía. Y no sólo, eso es evidente, por la muy desconsolada y desconsoladora historia que relata manifiestamente, en su anchísima pantalla de Cinemascope, sino, sobre todo, por la que cabe seguir leyendo entre líneas, entre plano y plano, en las miradas temerosas o culpables y evasivas de la actriz a la cámara o, mejor, un poco a un lado y más allá del objetivo, hacia el director, y más aún que en el rostro de Kirk Douglas en la imagen que Quine nos transmite de Kim Novak a través de cada encuadre, cada leve panorámica de acercamiento, o esa rendida e impúdica dolly vertical que recorre su cuerpo a una cierta distancia, como si fuese ya inalcanzable pero siguiese siendo deseable y querido: es la apoteosis de Kim Novak, casi el último beso, ya desesperado y suicida, del director.

Publicado en el nº 2 de Nickel Odeon (primavera de 1996)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#josé luis garci#1998#1990s#benito pérez galdós#tve#nickel odeon#spain#drama#old age / elderly#family

0 notes

Text

can you freaking imagine if the twewy fandom said you couldnt ship neku with shiki/josh/beat bc making a partner pact biologically connected them and thus it was "inc*st" like how ppl in the rise fandom say karai possessing april made her biologically related to the boys

#WITH WHAT?? GHOST DNA???#GHOSTS DONT HAVE CELLS#ITS JUST. AN ESSENCE.#anyway megan and i just watched donnie vs witchtown again and i got activated#donnie treats april better than his own literal brothers but yknow. theyre siblings.#'for you? anything.' just siblings#NICKEL-FREAKING-ODEON RELEASES A CANON APRITELLO EDIT IN A PROMOTIONAL TRAILER#WITH HEARTS OVERLAID OVER THE 'FOR YOU? ANYTHING' SCENE#FOLLOWED IMMEDIATELY BY APRILS VA VISIBLY EXCITED AT THE MENTION OF ROMANCE BETWEEN THE CHARACTERS#FOLLOWED IMMEDIATELY BY HER SCREAMING FOR DONNIES VA#but yknow. siblings! theyre just brother/sister. :^)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

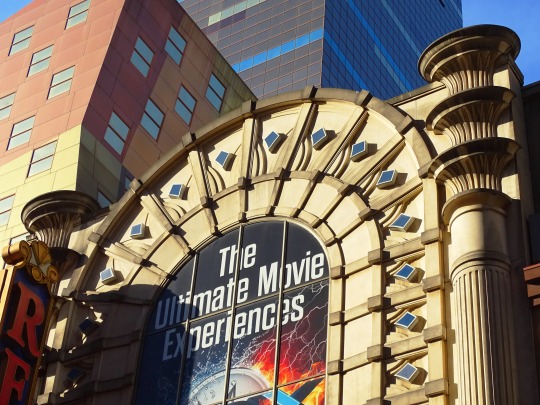

Movie Theatre Day

Movie Theatre Day is celebrated on April 23 each year. This holiday celebrates movie theaters and the thrills they bring into our lives. Today, movie theaters are more than relaxation centers, they also offer a great avenue to have romantic dates, meet new faces, and hang out with friends or family members after a hard day’s work. Much more, some movies now premiere first at the theaters before they are released to other channels for sales and streaming. This underlines the influence and importance of movie theaters today. Sadly, with the advent of the internet and the proliferation of streaming networks, movie theaters now face extinction and low patronage.

History of Movie Theatre Day

A movie theater (also sometimes called a cinema) describes a place where people go to see movies on a big screen. For over a century, movie theaters have served as a favorite spot to unwind, meet new people, and enjoy quality entertainment. On June 19, 1905, the first common type of public motion picture theater in the U.S. opened in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Harry Davis and John Harris — owners of the movie theater — named their cinema Nickelodeon. The name was derived from the words ‘nickel,’ the price of admission into the movie theater, and ‘θέατρο’ or ‘odeon,’ the Greek word for ‘theater.’ Previously, there had been several attempts by different individuals, groups, and companies to bring relaxing entertainment to people in the form of motion pictures in a film theater. Due to the limited technology available in those days, Nickelodeon’s first films were short films (only about 15 to 20 minutes long) shown as flickering shadows displayed on white sheets. While they may appear ridiculous today, they were a scientific breakthrough back then, and the films were largely successful. As they grew in popularity, more theaters multiplied across the country, heralding what became the cinematic industry.

Subsequently, color and sound films arrived in the 1920s. As the technologies improved, so did the size, architecture, clientele, location, ownership, and the types of amenities movie patrons enjoyed. Such were picture palaces, drive-in theaters, optimized movie formats, and large multiplexes and megaplexes (theaters with more than 10 screens). With these innovations came popcorn — a favorite cinema snack — and other concessions like candy and soft drinks. Today, cinemas have facilities like air conditioning, comfy cinema chairs, restaurants, arcades, and exquisitely decorated interiors to attract customers and enhance the viewing experience.

Movie Theatre Day timeline

1905 The Birth of Nickelodeon

Harry Davis and John Harris establish the Nickelodeon theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

1925 Popcorn Arrives in Theaters

Movie theater owners introduce the electric popcorn machine to cinema patrons.

1937 Adding Colors to Films

Walt Disney produces the first animated full-length color film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

1950s The Era of the C.G.I. and V.F.X.

Producers employ computer-generated imagery (C.G.I.) techniques and visual effects (V.F.X.) to create fantastical settings, impossible creatures, and jaw-dropping effects in movies.

Movie Theatre Day FAQs

What is World Theatre Day?

World Theatre Day is sponsored by the International Theatre Institute (ITI) each year. The day is celebrated by ITI Centers, ITI Cooperating Members, theater professionals, theater organizations, theater schools, and theater lovers across the world on March 27 every year.

What is the oldest movie theater?

The oldest continuously operating cinema theater is the Washington Iowa State Theatre in Washington, Iowa which opened on May 14, 1897, and has been in continuous operation for over 125 years!

What was the first movie in a theater?

As of 1905, the Nickelodeon theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was the first to show short films like “Poor but Honest” and “The Baffled Burglar” all day long.

Movie Theatre Day Activities

Visit a movie theater

Go on a movie date

Involve your family

Celebrate this day by visiting a cinema closest to you to see a movie or two. This is a great way to support local movie theaters and keep them in business.

If you’re not the outdoorsy type, you could go out with a friend or romantic interest. Buy some snacks and drinks along for a better movie date experience!

Find out if your local cinema is showing a family movie. Go out with your family and have a fun night out at the cinema!

5 Interesting Facts About Movie Theaters

Americans’ daily spending at the movies

Half a dollar for a movie ticket

No smelly feet in the theater, please

A movie theater in the White House

The world's first drive-in movie theater

Americans spend about $26.6million a day at movie theaters and they spend even more before and after a movie.

A movie theater ticket cost 50 cents in 1956.

It was once illegal to remove your shoes if you had smelly feet while in a theater in Winnetka, Illinois.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was the President who got permission to build a movie theater and swimming pool in the White House.

The world’s first drive-in movie theater was built on June 6, 1933, near Camden, New Jersey.

Why We Love Movie Theatre Day

Celebrating history

A day to relax

Supporting local businesses

The movie theater industry has come a long way, evolving and adjusting to meet the needs and demands of its customers. This day is an amazing opportunity to celebrate the cinema industry and its historic innovations.

Cinemas offer a relaxing and thrilling experience like no other. On this day, we can kick our feet up and enjoy a true cinema experience, guilt-free!

Today, the cinema industry is under threat by streaming services. Movie Theatre Day offers a great opportunity to support the threatened industry and its dedicated employees.

Source

#Paramount Theatre#Art Deco#Boston#Denver#Wyoming Theatre Two#Torringotn#New York City#66 Drive-In Theatre#Carthage#travel#vacation#Grauman's Chinese Theatre#Dolby Theatre#The Grove Theaters#Los Angeles#Movie Theatre Day#23 April#MovieTheatreDay#architecture#USA#cityscape#tourist attraction#landmark#original photography

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

My katamari sculpt collection!

I plan on making all the the cousins along with the king, and so on, but this project is mostly meant to improve my sculpting skills and learn nomad sculpt! I also might 3D Print all of my sculpt later on so I can paint them as well :)

The prince

First cousins

Ace

Colombo

Dipp

Foomin

Fujio

Havana

Honey

Ichigo

Johnson

June

Jungle

Kuro

Lalala

Marcy

Marny

Miso

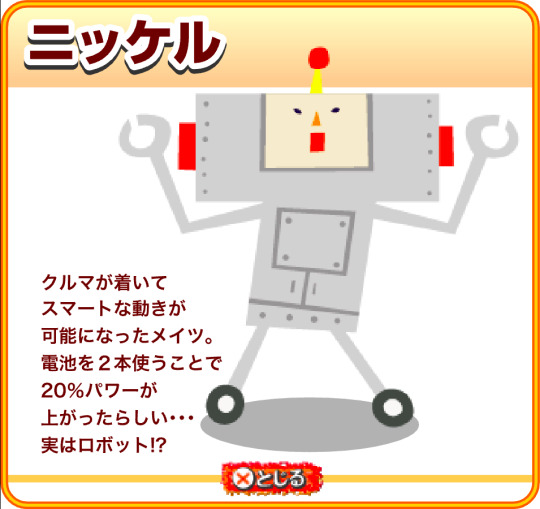

Nickel

Nik

Odeko

Opeo

Peso

Shikako

Velvet

Second cousins

Beyond

Can-can

Daisy

Droopy

Huey

Kinoko

L’Amour

Lucha

Macho

Miki

Nutsuo

Odeon

Shy

Signolo

Slip

Twinkle

Rookies

Ban-ban

Hans

Kenta

Mu

Nai-nai

Norn

Paula

Pokkle

Half cousins

Harvest

Kunihiro

Kyun

Mag

Princess

Pu

Ryu

Sherman

Katamari forever cousins

Dangle

Drive

Other Cousins

Namco High

Bandaideo

Crif

Toothy

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

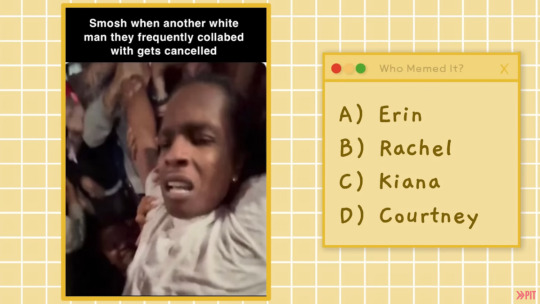

just thinking about this meme from Who Meme'd It today, for no reason in particular related to a livestream by cast members from a nickel/odeon show making fun of abuse survivors

I mean they were only on one video that I remember (TNTL) but still, smosh just cannot catch a break lol

0 notes

Text

Mr chopsaw and mr monroe from ned declassified school survival guide are gay lovers. This is canon trust me i know mr nickel odeon

0 notes

Photo

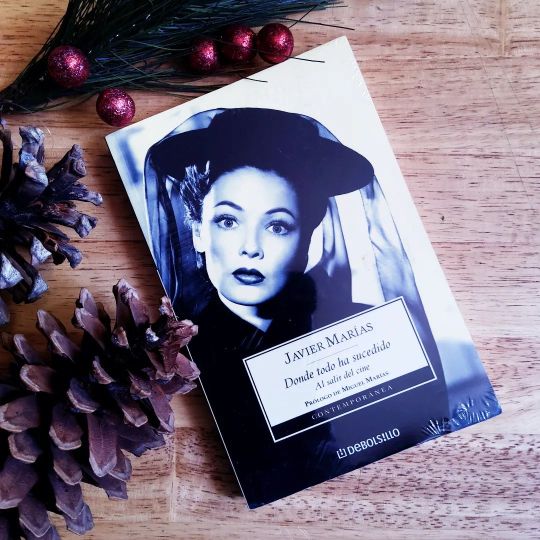

DONDE TODO HA SUCEDIDO: AL SALIR DEL CINE Autor: Javier Marías En este volumen se recogen los principales artículos sobre cine de Javier Marías, aparecidos en Nosferatu, Nickel Odeon, el semanal, el país y otras publicaciones, de 1992 a 2004. Centauros del desierto, de John Ford, campanadas a medianoche, de Orson Welles, el fantasma y la señora Muir, de Mankiewicz, el río, de Jean Renoir, con la muerte en los talones, de Alfred Hitchcock o Ed Wood, De Tim Burton son algunos de los clásicos inolvidables del celuloide que, a través de la hondura y fina percepción del escritor-cinéfilo, nos llegan con una nueva mirada🍃🍃🪴🪴🪴🐈🐈🐈🐈🪴🪴🪴🪴🐈⬛🐈⬛🐈⬛🐈⬛🍃🍃🍃🍃 ENVÍOS Y FORMA DE ENTREGA 📦🚇🐈🪴 Te invitamos a visitar nuestra tienda en línea https://linktr.ee/Loslibrosdepolifema Entregas personales todos los martes, miércoles y sábados en estación revolución línea 2 del STCM #escritores #lecturas #megustaleer #escritor #bookstagram #libreria #instalibros #librosymaslibros #poema #librosjuveniles #instabooks #lecturasrecomendadas #librosenventa #dondetodohasucedido de #javiermarias (en Mexico City, Mexico) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cmc3DMcOyXN/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#escritores#lecturas#megustaleer#escritor#bookstagram#libreria#instalibros#librosymaslibros#poema#librosjuveniles#instabooks#lecturasrecomendadas#librosenventa#dondetodohasucedido#javiermarias

0 notes

Text

Katamari cards 21-30, from the Beautiful Katamari card game (Katamaridamacy.jp, 2009)

#Katamari Damacy#Beautiful Katamari#miso#Marcy#Dipp#nickel#Twinkle#Nutsuo#Kinoko#L'amour#Lucha#Odeon

189 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We <3 Katamari - Presents - Bunny ears (part 4)

[part 1] [part 2] [part 3]

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isn't Him Romantic?

Billy Wilder

No es casualidad, y sí una clave, que la célebre y maravillosa canción de Richard Rodgers y Lorenz Hart Isn't It Romantic? [¿No es romántico?] sea el insistente leitmotiv de Sabrina, probablemente la primera de las películas de Billy Wilder como director en que revela, para sorpresa de muchos y apenas disimulada decepción de algunos, su lado profundamente romántico, que hasta entonces había ocultado en lo más hondo de obras de apariencia dura y seca, y de tonalidad escéptica, irónica e incluso pesimista y misantrópica, que le han labrado una persistente reputación de cineasta cáustico y amargo, cuando no cínico, fama críticamente rentable, ya que a mucha gente le divierten las actitudes cínicas.

Lo que sucede, creo yo, es que Wilder, como buena parte de los románticos de corazón, y muy particularmente los más tardíos, los que han nacido a destiempo (en general, demasiado tarde, muy raramente antes de lo debido) y han tenido que sobrevivir este siglo, no tiene nada de optimista, ni encuentra motivo alguno para serlo, sino que sabe muy bien, por experiencia propia y ajena, lo difícil que resulta que las cosas acaben como uno querría, y lo peligroso que resulta soñar y confiarse a la suerte y a la bondad de los demás, sin olvidar el riesgo de que, encima, se rían de uno en su desdicha. Como dice otra gran canción, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, "Ahora, los amigos se ríen, burlándose de las lágrimas que no puedes ocultar". Así que, prudentemente, el romántico actual suele pasarse a la clandestinidad, y procura disimular, además de protegerse de sí mismo con buenas provisiones de escepticismo, porque, sospecha, más le vale no hacerse demasiadas ilusiones. Lo que le hace, en realidad, desesperadamente romántico, es decir, doblemente romántico, porque su esperanza se basa no en la experiencia sino en los principios; podría decir, como otra estupenda canción, "I'm incurably romantic" [Soy incurablemente romántico], porque considera que es una enfermedad y que no tiene remedio.

Que Sabrina sea una película considerada menor por muchos de los fanáticos de Wilder, lo mismo que otra de sus obras menos vistas y más confesionalmente románticas, Ariane, no deja de ser revelador: prueba que Wilder no andaba descaminado al estimar que en los cincuenta, después de los horrores de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el romanticismo no se llevaba y llegar a la conclusión de que enseñar demasiado su intimidad equivalía a poner en peligro su independencia. La situación no iba a mejorar, ciertamente, en las décadas siguientes, así que Wilder siguió disimulando, una y otra vez, para que no se advirtiese, por lo menos a simple vista, cuán románticas, idealistas, morales, melancólicas y sentimentales son, en el fondo, comedias alocadas o ferozmente sarcásticas como Con faldas a lo loco, El apartamento, Irma la Dulce, Bésame, tonto, En bandeja de plata... Sólo al final de su carrera, cuando se creyó invulnerable (tras varios grandes éxitos seguidos de público y crítica) o pensó que ya nada tenía que perder (tras varios estrepitosos fracasos sucesivos), se ha permitido Wilder mostrar su romanticismo a cara descubierta: La vida privada de Sherlock Holmes, Avanti! (no usaré el largo trabalenguas irrecordable que le impusieron en España) y Fedora; que tampoco se contaron, por cierto, entre sus grandes éxitos, ni de crítica en general ni, y eso fue lo más grave, de taquilla.

Retrospectivamente, no es difícil ver lo que hay de romanticismo en algunos de sus guiones para Mitchell Leisen (como Si no amaneciera), por supuesto; pero también en Perdición, en Días sin huella, en El vals del emperador, en Berlín-Occidente, en El crepúsculo de los dioses, en El gran carnaval, en La tentación vive arriba y hasta en Testigo de cargo. Es decir, en casi toda su filmografía, con muy contadas excepciones absolutas (como Traidor en el infierno). Su caso, por cierto, no tiene nada de único: piénsese en otro cuarteto de supuestos cínicos ilustres del cine, Josef von Sternberg, Alfred Hitchcock, Max Ophuls y Joseph L. Mankiewicz, cada uno a su manera. Mal que les pese a los que sólo quieren ver la cara visible de Wilder, que les resulta más cómoda y les parece más vigente o más fácil de tratar de remedar, y que niegan incluso, en algunos casos, la mera existencia —no digamos la importancia y la sinceridad— de la oculta, creo demostrable que el verdadero Wilder es, en el fondo, el más grave, serio e idealista, y que los restantes rasgos aparentes de su carácter como cineasta no son sino caretas o barreras protectoras frente al doloroso desengaño que puede producir todo aquello sobre lo que uno, si se descuida, llega a hacerse ilusiones, sea el amor, la familia, los amigos, los ideales, la política, la vida de sociedad o el mismísimo ser humano.

No está bien visto, en casi cualquier sociedad de este siglo, por ejemplo, ser honrado, que no es —ciertamente— una tentación frecuente entre los personajes wilderianos; menos todavía la figura del habitualmente ridiculizado buen samaritano, que es, a su pesar, la que acaba encarnando el inicialmente más bien interesado, codicioso, egoísta y poco o nada escrupuloso ejecutivo C. C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) de El apartamento, y que se convierte, para mí, en la parte final de esta conmovedora obra maestra, en uno de los seres cinematográficos más admirables como persona de toda la historia del cine, frente al cual, de hecho, encuentro mezquinos y fatuos a casi todos los protagonistas —próceres, santos, artistas, héroes, mártires— de las películas hagiográficas. Romántica encuentro, y como pocas, la fantasmal relación que brota entre Pamela Piggott (Juliet Mills) y el muy reticente, convenientemente puritano y vulgar Wendell Ambruster Jr. (Lemmon de nuevo) en Ischia, en esa comedia de ambiente y tono totalmente funerario que es Avanti! Románticas en grado sumo me parecen la amargura y la postración casi suicida de Sherlock Holmes (Robert Stephens), que nos revela póstumamente sus recuerdos guardados durante cincuenta años en La vida privada de Sherlock Holmes, y que iluminan verosímilmente algunos aspectos controvertidos y enigmáticos de esta figura literaria tan resistente a la muerte y al olvido, pese a la incesante sucesión de generación tras generación de lectores. Románticas son, creo yo, las verdaderas razones de lo que sucede bajo el aparente vodevil picante y de mal gusto que cuenta Bésame, tonto, de superficie áspera y basta y corazón elegante y sensible, y en especial las dos entrañables figuras femeninas que componen la siempre exquisita y discreta Felicia Farr y esta vez la vulgar y llamativa Kim Novak, más carnal aquí que nunca, pero en el fondo tan soñadora y sensible como en Vértigo.

Es más, quizá lo más extraordinario del romanticismo de Wilder es que carece de su aureola artificial más ostentosa y evidente, lo mismo que algunos de los grandes poetas logran prescindir por completo tanto de las palabras (ruiseñor, alba, ocaso, etcétera) como de los giros gramaticales considerados poéticos. En Wilder surge el romanticismo —el amor, la pasión, la fidelidad, el sacrificio, la locura— donde menos se espera, entre las personas más prosaicas o mediocres a primera vista, en el terreno menos propicio y más baldío en apariencia, y se permite, para colmo, no presentarse como algo heroico, sino simplemente como un sentimiento irremediable. Ya dijo René Char: "Ante el infortunio, el poeta responde con salvas de felicidad", y creo que Wilder no hace otra cosa.

Publicado en el nº 10, dedicado a Billy Wilder, de Nickel Odeon (primavera de 1998)

1 note

·

View note

Note

I don’t date people prettier than me was also taken from big time rush the nickoleodoen show mixkoloead Nickelodeon? Nickel odeon- 💜🐸

Ahh, I’ve never actually seen BTR 😂

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movie Theatre Day

Movie Theatre Day is celebrated on April 23 each year. This holiday celebrates movie theaters and the thrills they bring into our lives. Today, movie theaters are more than relaxation centers, they also offer a great avenue to have romantic dates, meet new faces, and hang out with friends or family members after a hard day’s work. Much more, some movies now premiere first at the theaters before they are released to other channels for sales and streaming. This underlines the influence and importance of movie theaters today. Sadly, with the advent of the internet and the proliferation of streaming networks, movie theaters now face extinction and low patronage.

History of Movie Theatre Day

A movie theater (also sometimes called a cinema) describes a place where people go to see movies on a big screen. For over a century, movie theaters have served as a favorite spot to unwind, meet new people, and enjoy quality entertainment. On June 19, 1905, the first common type of public motion picture theater in the U.S. opened in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Harry Davis and John Harris — owners of the movie theater — named their cinema Nickelodeon. The name was derived from the words ‘nickel,’ the price of admission into the movie theater, and ‘θέατρο’ or ‘odeon,’ the Greek word for ‘theater.’ Previously, there had been several attempts by different individuals, groups, and companies to bring relaxing entertainment to people in the form of motion pictures in a film theater. Due to the limited technology available in those days, Nickelodeon’s first films were short films (only about 15 to 20 minutes long) shown as flickering shadows displayed on white sheets. While they may appear ridiculous today, they were a scientific breakthrough back then, and the films were largely successful. As they grew in popularity, more theaters multiplied across the country, heralding what became the cinematic industry.

Subsequently, color and sound films arrived in the 1920s. As the technologies improved, so did the size, architecture, clientele, location, ownership, and the types of amenities movie patrons enjoyed. Such were picture palaces, drive-in theaters, optimized movie formats, and large multiplexes and megaplexes (theaters with more than 10 screens). With these innovations came popcorn — a favorite cinema snack — and other concessions like candy and soft drinks. Today, cinemas have facilities like air conditioning, comfy cinema chairs, restaurants, arcades, and exquisitely decorated interiors to attract customers and enhance the viewing experience.

Movie Theatre Day timeline

1905 The Birth of Nickelodeon

Harry Davis and John Harris establish the Nickelodeon theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

1925 Popcorn Arrives in Theaters

Movie theater owners introduce the electric popcorn machine to cinema patrons.

1937 Adding Colors to Films

Walt Disney produces the first animated full-length color film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

1950s The Era of the C.G.I. and V.F.X.

Producers employ computer-generated imagery (C.G.I.) techniques and visual effects (V.F.X.) to create fantastical settings, impossible creatures, and jaw-dropping effects in movies.

Movie Theatre Day FAQs

What is World Theatre Day?

World Theatre Day is sponsored by the International Theatre Institute (ITI) each year. The day is celebrated by ITI Centers, ITI Cooperating Members, theater professionals, theater organizations, theater schools, and theater lovers across the world on March 27 every year.

What is the oldest movie theater?

The oldest continuously operating cinema theater is the Washington Iowa State Theatre in Washington, Iowa which opened on May 14, 1897, and has been in continuous operation for over 125 years!

What was the first movie in a theater?

As of 1905, the Nickelodeon theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was the first to show short films like “Poor but Honest” and “The Baffled Burglar” all day long.

Movie Theatre Day Activities

Visit a movie theater

Go on a movie date

Involve your family

Celebrate this day by visiting a cinema closest to you to see a movie or two. This is a great way to support local movie theaters and keep them in business.

If you’re not the outdoorsy type, you could go out with a friend or romantic interest. Buy some snacks and drinks along for a better movie date experience!

Find out if your local cinema is showing a family movie. Go out with your family and have a fun night out at the cinema!

5 Interesting Facts About Movie Theaters

Americans’ daily spending at the movies

Half a dollar for a movie ticket

No smelly feet in the theater, please

A movie theater in the White House

The world's first drive-in movie theater

Americans spend about $26.6million a day at movie theaters and they spend even more before and after a movie.

A movie theater ticket cost 50 cents in 1956.

It was once illegal to remove your shoes if you had smelly feet while in a theater in Winnetka, Illinois.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was the President who got permission to build a movie theater and swimming pool in the White House.

The world’s first drive-in movie theater was built on June 6, 1933, near Camden, New Jersey.

Why We Love Movie Theatre Day

Celebrating history

A day to relax

Supporting local businesses

The movie theater industry has come a long way, evolving and adjusting to meet the needs and demands of its customers. This day is an amazing opportunity to celebrate the cinema industry and its historic innovations.

Cinemas offer a relaxing and thrilling experience like no other. On this day, we can kick our feet up and enjoy a true cinema experience, guilt-free!

Today, the cinema industry is under threat by streaming services. Movie Theatre Day offers a great opportunity to support the threatened industry and its dedicated employees.

Source

#Paramount Theatre#Art Deco#Boston#Denver#Wyoming Theatre Two#Torringotn#New York City#66 Drive-In Theatre#Carthage#travel#vacation#Grauman's Chinese Theatre#Dolby Theatre#The Grove Theaters#Los Angeles#Movie Theatre Day#23 April#MovieTheatreDay#architecture#USA#cityscape#tourist attraction#landmark#original photography

1 note

·

View note

Text

I gotta talk about something because otherwise I’ll send an email to my professor and he won’t care because it wasn’t the point of the lecture

OKAY SO LISTEN UP THIS IS A MILE LONG BUT IF I DON’T SAY SOMETHING I WILL EXPLODE

I’m in a college-level history of film class, and as such we’re going through and watching lots of old movies and reading about the historical contexts for various cinematic movements, right? And for a long time, there wasn’t any sound in movies. We as a whole started making movies in the 1890s and premiered synchronized sound in the film The Jazz Singer in 1927 (it’s a terrible movie, but hey, it had sound!), but sound wasn’t really utilized until the 1930s. So when people went to watch movies prior to the 1930s, they didn’t just sit in silence like a bunch of weirdos. The theaters (often called Nickelodeons because it was a nickel to go watch a movie (the -odeons comes from the Greek word for film)) would employ either a phonograph or a live musician to provide musical accompaniment to the day’s films.

An interesting little tidbit, it’s believed that around 95% of the early silent films have been lost, either due to irresponsible caretaking of the film reels or intentional destruction for various reasons (see: Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922) and A Trip to the Moon (Georges Méliès, 1902)). So in reality, we’re very lucky to see any of the silent films we do get to see. Along with that, there weren’t many musical scores for these silent films that survived, either. So it’s up to us in today’s modern age to make up for the lost musical score and accompaniment.

This is where I start to get upset.

There are many versions of silent film scores that fit very well with the film and the time period they come from.

My film teacher chose none of these to show the class.

At first, I thought I could take it. Early on, we watched A Trip to the Moon for our recitation, and it was a lovely film! A true classic, and very fun to watch. It was the precursor for the science fiction genre that we all know and love today, which is pretty rad! However, the accompanied score was made in 2010. And the group that made this particular score saw the phrase “science fiction” and took it way too far. There was all sort of electronic beeps and blips and boops to accentuate the scenes of the moon, and it was very out of place. People in 1902 had no context in which to know what these modern sounds were, and it was rather jarring to hear them in this film.

I just sighed and said “fuck it, whatever,” and went along with it because it was in the name of ‘science fiction.’ They’re on the moon, after all!

But this week, my professor took it too far.

This week, we delved into the world of Soviet Montage filmmaking. Basically, this style comes from an art style called Constructivism and was very popular in 1920s Soviet Russia. They thought that the film should serve a purpose, and that the filmmaker was like the engineer putting the film together. The whole movement came out of their trauma of World War I, and it’s a super neat genre. It really focused on the editing of a film rather than individual shots, and something called the Kuleshov Effect came out of the era. The effect strives to show how meaning of a sequence can be drastically changed based on which shots are included and the order that the particular shots are in.

To accompany this discussion, my professor had us watch a film called Man With a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929). It’s a really interesting film that doesn’t focus on specific characters, but instead the life of a modern 1920s Soviet city throughout a day. It uses a lot of different shots and editing patterns, and it’s a really great watch if you get the chance!

But the score is just atrocious. This particular version’s score was made in 2003, and it shows. Musically, 2003 was a time when jarring electronic noises were very popular, both in songs and in musical scores. The people who wrote the score for this 1929 film decided to include sounds very obviously from 2003, and it physically hurt to sit through. I did my best to give the score the benefit of the doubt during this film, but I literally had to mute the sound halfway through because it was just so horrible to listen to. This particular score made me so angry that I legitimately couldn’t sleep, and it was the only thing I could think about during recitation.

There are multiple points throughout this film that give musical and thematic cues, and the composers flat out ignore all of them. I understand that the film is rather old and can be hard to comprehend, I don’t fully understand it myself, but if you’re going to be the composer for it, then you better take the time to understand what’s going on. The score takes its own trip throughout the film and disregards the visuals of the film entirely. There’s a sequence in the film where there’s music being played (the viewer can’t hear it because it’s a silent film), and if a composer were to slow the film down, they could figure out what was being played and incorporate it into the score. But no, these composers wrote their own tune and slapped it over the scene, and it takes the viewer completely out of the viewing experience. The score takes the viewer out of the viewing experience throughout the entire film, but it’s very prominent in this particular sequence.

And another thing. If you’re going to write a score for an older film, it would make sense to put the score through a filter that made it sound like it was coming from the older generation. To elaborate, when you hear sound that was recorded in the 1900s, there’s always an auditory static grain around it, and the sound is rarely crisp like we hear recorded sound to be today. There are filters that we can use to make the films we shoot today look ‘vintage,’ and I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s also filters we can put over audio tracks to make them sound ‘vintage.’ Matching the auditory grain of the score with the visual grain of the film should be an integral part of fitting newer scores with older films. Sadly, many composers don’t do that which makes the score, regardless of how well it fits with the film thematically, feel very out of place. However, other filmmakers do achieve this, and it blends the score into the film beautifully and makes for a very engaging experience.

Of course, the composers for Man With a Movie Camera didn’t do this, and just slapped their crisp, modern sounding drums and electronic garbage over the grainy silent film, making the experience abhorrent to sit through.

If the composers for this film had just sat down and really thought about the film they were making this score for, they could have been very successful. In an experimental film like Man With a Movie Camera, it’s not out of the realm of possibility to get experimental with the scoring. However, when you score a film that is 92 years old, you have to take into consideration the context of the time during which the film was created, and compose the score around that context. It doesn’t make sense to put 2003 electronic sounds in a 1929 film because director Dziga Vertov most likely never heard those kinds of sounds in his entire life, or at least when he was making his film. It also doesn’t make sense to put crisp audio tracks into an older film because older film’s audio tracks were grainy and sometimes hard to understand (see: The Jazz Singer (its audio track was very garbled and you couldn’t understand what the characters were saying)). Instead, composers should create their scores to cater to the film and the time during which it was made, instead of what new cool technology we have at our fingers in the 21st century.

To conclude, Man With a Movie Camera is a great visual film that you should definitely watch if you have the moment to spare, but just make sure that you don’t pick the version of it my professor gave to me. You’ll save many brain cells and you’ll have a grand old time too. I apologize for this post being so long, but if I sent this to my professor he either wouldn’t care or would fight me on this because he liked the score and I would like to pass that class without having to fight my professor on why he’s wrong, thank you very much.

#i shit you not i was literally so angry that i didn't sleep last night#it was bad#man with a movie camera#film#silent film#soviet montage#constructivism#film history#dziga vertov

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@Nickelodeon

Because I know so many people are doing rants about, rise of the turtles. I wanted to make this post. I want to say I'm sorry that so many people are harassing you about the show, You can't help what sells and doesn't sell.

It was raided a 4 out of 10 while 2012 was rated 7 out of 10.

I don't care what anyone says you can't compare the 2 shows. I mean they literally made the characters dumb in the rise of the turtles. The like had no brains they were not concentrating at all it was more slapstick humor like South Park.

Some people want intelligence in a show they want plot they want good character structure. There was none of that in the show.

And this is just my personal view. I fully understand that you have to do what's best for your TV show and your TV channel.

It just didn't get a lot of readings like he can't blame Nickelodeon for that just because a lot of people didn't like it.

I mean granite there was some good parts in it and I tried watching it but I literally I felt my brain just it wasn't good Lake it just not only that. A show like that with so much flashing could cause epilepsy I felt like those going to have a seizure in the final.

There should have been at least a warning for flashing lights.

All I'm saying nickel odeon is I don't blame you for canceling the show if that's what you did. People have to understand that they're gonna do what's best for your channel and it's not your fault that it didnt sell well.

I fully support whatever you do.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peep Shows and Palaces

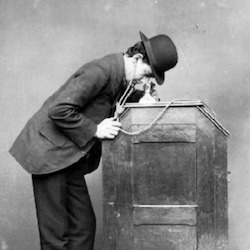

For all their immense impact on popular culture, movies began humbly, and for a while it looked like they might never be more than a minor amusement. The first movies shown to the American public, Edison's Kinetographs, appeared in the early 1890s. Because neither Edison nor anyone else had yet invented viable projectors, the first short film loops weren't shown on screens. One viewer at a time dropped a penny in the Kinetoscope peep show machine, turned the crank and watched the one-minute loop through the eyepiece. The peep show's appeal was as limited as its technology, and it never caught on outside of penny arcades.

Projectors came along soon enough anyway. Interestingly, given film's later impact on live performance, the first commercial screening of a projected movie in the U.S. was in a vaudeville theater: Koster and Bial's Music Hall on Thirty-Fourth Street, where Macy's is now, in 1896. Other vaudeville theaters followed suit. At first they screened films as what were called "chasers" -- acts at the end of the bill that were so bad or boring they cleared the house, making way for the next paying customers and the next cycle of performers. Because the films often just showed vaudeville acts recreated in silent pantomime, audiences shrugged and walked out on them.

As soon as projectors were developed, small-time showmen were traveling the country with them. They'd come into a town, identify a willing merchant, and set up a "store show" after regular business hours, screening their short films to the accompaniment of a local pianist, with maybe some local live acts as well.

The sea change came when store shows evolved into the nickelodeon (nickel Odeon), a permanent venue for screening short films. When a smal nickelodeon opened in Pittsburgh in 1905, its debut offering was Edwin S. Porter's twelve-minute Western (shot in Jersey and Delaware), The Great Train Robbery. Porter, the visionary head of Edison's movie production studios, pioneered directorial techniques still used in movies today. Both Porter's film and the nickelodeon concept were instant sensations and spread with amazing speed to other cities. In three years there were some ten thousand nickelodeons and small movie houses around the country.

There were around a hundred and twenty-five nickelodeons and movie houses in New York City by then, not counting the vaudeville theaters that also showed films. A third of them were on the Lower East Side. Many were in storefronts strung along the Bowery and other main avenues from Union Square down. Several were crowded around Union Square itself. The neighborhood's new immigrants flocked to movies, which, being simple melodramas and comedies enacted in silent pantomime, presented no language barrier. Nickelodeons and movie houses spread quickly to other immigrant neighborhoods in Manhattan, like the German Yorkville, Jewish Harlem and the Italian East Harlem. As they'd done for decades at live theater, working-class audiences participated fully in the movie, yelling advice to the actors, screaming, crying, leaping into the aisles, throwing things at the screen. Into the twenty-first century movie theater managers would struggle to impose order and quiet.

Although many of the venues on the Lower East Side were the cramped, dingy little nickelodeons of movie lore, some were much grander. In 1908 Tammany Hall's Big Tim Sullivan and his partner George Krause leased the Dewey Theater, their thousand-seat vaudeville house on Fourteenth Street (which they'd named for Admiral Dewey, hero of the Spanish-American War), to William Fox. Born Wilhelm Fried, Fox was a German Jewish immigrant from Hungary. He started a two-hour program combining short films and vaudeville acts, and charged a ten-cent admission. The Dewey was an early avatar of the plush movie palaces to come, with nice seats and uniformed ushers, and it was a huge success. The Dewey made movie-going safe and attractive for the middle class who had stayed away from the rowdy, smelly nickelodeons. Fox next rented the Academy of Music across the street, an 1854 opera house that had converted to vaudeville in the 1880s, and enjoyed similar success there. He went on to found the Fox Film Corporation, ancestor of Twentieth Century-Fox.

By 1915 studios in both New York and Hollywood were making feature-length films. The nickelodeon faded into history, more vaudeville houses were converted into cinemas, and soon the grand movie palaces, built solely and lavishly to screen films, began to appear. By the time sound was added in the late 1920s, movies were indisputably the dominant form of mass entertainment and starting to kill off vaudeville.

Marcus Loew rose up from the Lower East Side to help drive those developments. He was born in 1870 at Avenue B and East Fifth Street, in what was then known as Kleindeutschland, Little Germany or Dutchtown. His father, recently emigrated from Vienna, worked as a waiter. Marcus began hawking newspapers on the street at age six to help the family make ends meet; by nine he'd quit school to work six days a week at a printing plant. He earned thirty-five cents a ten-hour day, making his weekly paycheck about fifty dollars in today's dollars. Soon he and a young partner were running their own small printing business and putting out a weekly shopper, the East Side Advertiser. By the mid-1890s he was a partner in a fur company, Baer & Loew, operating from a loft on Union Square.

In 1903 Adolph Zukor, who'd come up through the fur business in Chicago, opened a penny arcade, Automatic Vaudeville, around the corner from Baer & Loew on Fourteenth Street. Loew and Zukor became lifelong friends even after Loew decided to go into the arcade business for himself. He called his operation People's Vaudeville and opened his first one in a storefront on East Twenty-Third Street in 1905. He was on his way to building a chain of arcades in New York and other cities when he visited a newfangled nickelodeon in the Midwest and saw the future. Returning to New York, he converted People's Vaudeville to a nickelodeon. He also experimented with another type of amusement using film, called the scenic tour. A storefront was made up to look like the inside of a rail car. Films of passing scenery played outside the windows, while clackety-clack sounds and swaying seats added to the illusion. Amusement parks have rides today that are not significantly different in concept, just higher-tech.

Pretty soon Loew was building a chain of combination film-and-vaudeville houses, mostly on the East Coast. Loew's State Theatre in Times Square, opened in 1921, was one of the most popular movie-and-vaudeville palaces in the city. New Yorkers decided that Loew's should be pronounced low-eez, and you still meet some older ones who do. The State survived through various incarnations -- films from Some Like It Hot and Ben-Hur to The Godfather had their world premieres there -- until it was torn down for a Virgin Megastore in the 1990s.

Needing product to put in his theaters, Loew had bought William Morris' booking agency for live acts in the 1910s. He then acquired the film production houses Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures and Mayer Pictures to create MGM. By the time of his death in 1927, Loew's movie theaters, showing primarily or exclusively MGM films, had spread around the country and across the Atlantic to England. Meanwhile, what his friend Zukor started as an arcade with peep shows on Fourteenth Street grew up to be Paramount Pictures.

by John Strausbaugh

6 notes

·

View notes