#noblewomen

Text

Rose's lunch outfit (Titanic, 1997)

#titanic#filmedit#james cameron#kate winslet#perioddramaedit#edwardian fashion#titanic 1997#james cameron titanic#costumedit#edwardian era#1900s fashion#noblewomen#rose dewitt bukater#moviegifs#filmgifs#tvfilmcentral#tvfilmgifs#filmtvcentral#filmtvgifs#my edit#period drama#historical drama

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary de Bohun, Countess of Derby

Mary de Bohun was probably born around 22 December 1370 to Humphrey de Bohun and Joan Fitzalan, Earl and Countess of Hereford. As her father had no son, she and her elder sister, Eleanor, became the heiresses of his wealthy earldom. Eleanor married Thomas of Woodstock, the youngest son of Edward III, and according to Froissart, Woodstock intended Mary to enter a nunnery so he would inherit the entire earldom. This was not to be. In late 1380 or early 1381, Mary married John of Gaunt's son and heir, Henry Bolingbroke, the future Henry IV. The marriage appears to have happy as they shared similar interests and often spent time together. The story that Mary gave birth to a short-lived son in 1382, when she would have been only 11, is now believed to be a myth brought into being by a mistranslated text referring to her sister giving birth to a son. Mary's first child was the future Henry V, born 16 September 1386. Four more children soon followed: Thomas, Duke of Clarence (29 September 1387), John, Duke of Bedford (20 June 1389), Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (3 October 1390) and Blanche, Electress Palatine (25 February 1392). Mary died either giving birth to her sixth and final child, Philippa, Queen of Norway, Denmark and Sweden, or from complications afterwards, on 1 July 1394, when she was only 23 years old. Mary was buried on 6 July 1394 in the Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke in Leicester. The church and her tomb was destroyed in the Reformation.

A little of her personality can be reconstructed. She was interested in music, playing the harp or cithara, and she bought a ruler to line parchment for musical notation, suggesting she may have also composed music.Such an interest was shared by both her husband and eldest son, one or both of whom were the 'Roy Henry' who composed two mass movements. She maintained a close contacts with other noblewomen, not only her mother and sister, but Constanza of Castile, Katherine Swynford and Margaret Bagot, suggesting that she may well have been more politically aware and involved than what is generally believed. She may have also continued the de Bohun of patronising manuscript illuminators. A number of illuminated manuscripts believed to belong to her or her sister are some of the most celebrated late medieval English manuscripts.

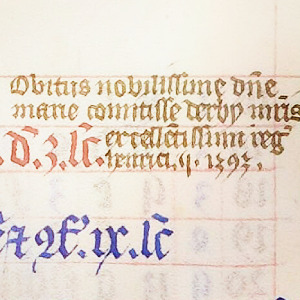

Mary never became Duchess of Lancaster, let alone Queen of England, but it was her family's badge of the swan that became associated with the Lancastrian kings, most famously borne by her eldest son, Henry V. One of Henry V's first acts as king was to order a copper effigy for her tomb, while in the charter of his Syon foundation, he required that the soul of "Mary … our most dear mother", among others, be prayed for in a daily divine service. Her third son, John, recorded her anniversary into his personal breviary, while her daughters may have each carried manuscripts belonging to her with them when they left England to be married. Despite the brevity of her life, Mary was remembered long after her death.

Sources: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS Lat. 17294, Chris Given-Wilson, Henry IV (Yale University Press 2017), Ian Mortimer, The Fears of Henry IV (Vintage 2008), John Matusiak, Henry V (Routledge 2012), Calendar of the Patent Rolls: Henry IV. Vol. I. A. D. 1399-1401, Calendar of Close Rolls 1381-1385, Rebecca Holdorph, 'My Well-Beloved Companion': Men, Women, Marriage and Power in the Earldom and Duchy of Lancaster, 1265-1399, University of Southampton, PhD Thesis, Marina Vidas, The Cophenhagen Bohun Hours: Women, Representation and Reception in Fourteenth Century England (Museum Tusculanum Press 2019)

79 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why was queens pardoning prisoners seen as good? Like murders and sexual assaulter ect? Wouldn’t the public be against that? Especially if they’re not sending money or justice to the victims or their families?

It was seen as good because interceding on behalf of others, demonstrating mercy and compassion, appealing to a spouse's better nature, etc. were all actions that fell within the feminine sphere of influence. That said, I don't think queens were pardoning or interceding on behalf of rapists and murderers. More likely, they would have appealed on behalf of disgraced nobles or cities (as happened, for example, with Queen Philippa, wife of Edward III of England, and the six burghers of Calais during the Hundred Years War).

Thanks for the question, anon

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Noblewomen appear in twelfth-century texts as both active subjects and passive objects, in complex ways, pursuing political ambition, as religious, pious wives, mothers and daughters. Such views of women depend very much on genre, date of composition and context of entry of a female character into the narrative. It is important to recognise that medieval writers wrote within convention. When Étienne de Fougères wrote his Le Livre des Manières in 1160–70, he described good and bad women, and used the countess of Hereford as his model of female courtly, aristocratic and ‘good behaviour’.

In the early twelfth century, Baudri de Bourgeuil wrote of the beauty of his subjects within a convention which dated from the poetry of Maximillian; therefore he wrote of eyes that shine like stars or teeth like ivory. Orderis Vitalis’s view of women’s power in the context of their political and warlike activity, like his view of men, is ambiguous, and by no means monolithic. For example, Orderic described women actively engaged in the military campaigns of their husbands. Isabel of Conches rode out to war ‘armed as a knight among the knights, and she showed no less courage among the knights in hauberks than did the maid Camilla’.

His story focuses on the disagreements between Helewise, the wife of William, count of Evreux, and Isabel of Conches, wife of Ralph of Tosny, who caused their husbands to take up arms against each other. Although the female warrior may well be no more than a ‘well-worn literary motif ’, it is striking that Orderic ascribes different personal qualities to each woman. Isabel is praised as a generous, daring and gay character who was well loved. Her opponent Helewise is by contrast ‘clever and persuasive, cruel and grasping’. He later commented on Isabel’s retirement to a nunnery, where she ‘worthily reformed her life’ and repented of her ‘mortal sin of luxury’.

On the presence of women at the battle of Ascalon, he states that women remained off the battlefield with the noncombatants and that they are ‘unwarlike by nature’. The emotional weakness of women is made gender-specific in Orderic’s discussion of the expedition and aftermath of the defeat and capture of Mark Bohemond when campaigning against the Turks. He states that Tancred, the commander in chief, ‘did not give way like a woman to vain tears and laments’ but mustered an army and governed the lands.

This assertion that women’s emotional weakness affects their judgement is a recurring theme in twelfth-century chroniclers. Powerful women who pursued their own political objectives in contexts that Orderic disapproved of, like their male counterparts, usually meet an ignominious end. The image of a powerful widow such as Adelais, the widow of Roger I count of Sicily, could be mutable. Orderic portrays her in a relatively sympathetic light when she ruled with counsellors for her son.

However, he turns her into a murderous poisoner who, after marrying for a third time, is repudiated by her husband and dies ‘an object of general contempt’ and ‘stained with many crimes’. Orderic approves a context for legitimate action which is thus as a widow in the stead of a legitimate heir. Aubrée, the wife of Ralph of Ivry, had built an ‘almost impregnable castle’. Yet this achievement is tempered with the tale that she was killed by her own husband for attempting to expel him from it.

Orderic’s portrayal of such powerful women is complex. Mabel of Bellême is depicted as a cruel woman who deserved to meet a miserable end, murdered in her bed by a vassal whom she had deprived of his lands. Chibnall believes that the detail of a murder of a warrior in a bath lies within the epic tradition. Thus she implies that the story is a fabrication. The historicity of the detail is not as important here as the significance of the way in which Mabel’s death is described.

Orderic depicts Mabel using conventions of the epic genre; such a portrayal adds a certain dignity to her reputation whilst paradoxically seeking to destroy it, and thus he inverts the topos. In recompense for this Orderic records her obituary, as it was inscribed upon her tomb, but he states this was ‘more through the partiality of friends than any just deserts of hers’. The obituary states that she gave good counsel, provided patronage and largesse, protected her patrimony, was intelligent, energetic in action and possessed honestas – honour, dignity.

Orderic’s sharp comment, however, is reflective of the nature of contemporary politics in early twelfth-century Normandy as much as of his distrust of women. The Bellême family were the hereditary enemies of the Giroie family, who were the founders of Orderic’s monastery of St Evroul. Orderic’s portrayal of Mabel of Bellême is therefore reflective of both contemporary clerical distrust of women in power and the nature of contemporary politics in Normandy. Orderic’s attention to human frailty leads him to praise both men and women or condemn them for lapses in behaviour.

Orderic records women’s obituaries on several occasions, for example, Countess Sibyl, who allegedly died from poisoning, is praised for her birth, beauty, wealth, chastity, largesse and prudence. Women are usually praised for their beauty, fertility and religiosity: traits which Orderic admired in women. Other clerics in the twelfth century likewise wrote obituaries for women, including Baudri of Bourgeuil and Robert Partes, a monk, of Reading, who in the mid-twelfth century wrote nine obituaries for his mother which he sent to his twin brother.

Orderic voices most approval for women who act within the context of religious patronage, and who are often depicted as acting with their sons and husbands to ensure the security of their gifts to his monastery. In this respect women are portrayed as having a beneficial influence. Avice, the daughter of Herbrand, who married Walter of Heugleville, is praised for her ‘advice and wise counsel’, her care for ��widows, waifs and the sick’, as well as her beauty. She was ‘most fair of face’, ‘well spoken and full of wisdom’; he praised her prudence and her ‘golden tongue’.

She acted as a civilising influence on her husband and ‘restrained him from his earlier folly’. Indeed, Orderic copied her epitaph, which was composed for her by ‘Vitalis the Englishman’. Her praiseworthy traits are her nobility, fair face, wisdom, modesty, sound morality, her fertility (she had twelve children ‘most of whom died prematurely in infancy’), her generosity to the church, and her constancy and chastity.

Stephen Jaeger believes that women played a civilising role in society, and that romance literature created chivalric values, values adapted from a social code of courtliness. Orderic thus apparently articulated the civilising influence of women upon their husbands prior to the emergence of romance literature. Indeed, this beneficial role of a wife in directing the morality of her husband is clear in Orderic’s tale of a Breton whose wife persuaded him to give up a life of crime by obeying her wise counsels.

Orderic’s portrayal of women, laced with his perception of the appropriate behaviour of women at different stages of their life cycle, confirms the validity of Stafford’s general approach. Thus a good wife encourages her husband in religious patronage, will offer advice and be obedient to her husband’s wishes. A wife will give good counsel. Orderic’s ambiguous view of women’s influence extends to his view of sexual power.

He describes how Adela, the wife of William duke of Poitou, used the marital bed to persuade her husband to go on crusade: ‘between conjugal caresses’ she urged him to go for the sake of Christendom, and to protect his honour. Orderic calls her mulier sagax et animosa. The importance of the female life cycle underpins Orderic’s portrayal of Windesmoth, the wife of Peter lord of Maule. She is praised for her modesty, chastity, piety, fecundity and her respect for her stepmother.

He approves of the fact that she was young and newly married, since she was ‘unformed’ and thus more open to her husband’s influence. Once widowed, she lived as a virtuous and ‘happy matron’, and remained chaste and unmarried for fifteen years, ‘dutifully supported by her son in her husband’s chamber up to old age!’ This theme of the obedient compliant wife and chaste widow is evident in the portrayal of Windesmoth’s daughter-in-law.

Her son Ansold, when on his deathbed, urged his wife, Odeline, to live chastely in widowhood, and to continue to guide their children morally until adulthood, and he implored her to release him from the marital bond so that he could become a monk. She ‘wept copiously’ and obediently consented to his wishes, since ‘she had never been in the habit of opposing his will’. Orderic praises the obedience of women to their husband and sons, and approves of chastity in widowhood.

The articulation of such values confirms the importance of the female life cycle and gender roles upon the portrayal of the power of wives and widows. The vulnerability of women, and their dependence on their husband or kin, are a recurring theme in Orderic’s history of the great Norman families. It also confirms that wives had important roles to play in lordship. For example, Radegund, the wife of Robert of Giroie, deputised for her husband whilst he was on campaign, but she lost control of the household knights when news of his death reached her.

This example is suggestive of the vulnerability of wives to the vagaries of their husband’s political fortunes, but also their supportive and martial roles. Such vulnerability is reflected in the exile of Agnes, daughter of Robert de Grandmesnil, after her husband, Robert of Giroie, had disregarded King Henry’s will and attacked Enguerrand l’Oison. The difficult position of noblewomen because of contemporary political volatilities and the importance of familial connections is evident in the example of Matilda de L’Aigle.

Orderic states that she shared her husband’s bed ‘fearfully, for three months only, amid the clash of arms’ and ‘for many years led an unhappy life in great distress’ after the imprisonment of her husband. Her second marriage was no greater success: she was repudiated by her second husband, Nigel d’Aubigny, after the death of her brother. The impact that war and political misfortune could have on family members is often depicted.

Orderic’s story of the resolution of a dispute between Henry I and Eustace of Breteuil, a powerful Norman lord who had control of the strategic castle of Ivry, shows how women used kin networks to their advantage. Eustace was married to Juliana, an illegitimate daughter of Henry by a concubine. The marriage was of course a political alliance, but Orderic illuminates the difficulties this could cause women.

Henry had control of Eustace’s castle at Ivry, and agreed to return the castle at a later date. In order to show faith between Henry I and Eustace hostages were exchanged, but on malicious advice Eustace put out the eyes of the boy that he received. As a result Henry I handed over his two granddaughters to the father of the blinded boy, who then had them blinded and the tips of their noses cut off.

This drove Eustace and Juliana to rebel. Juliana was sent to her husband’s castle of Breteuil ‘with the knights necessary to defend the fortress’, whilst Eustace fortified his castles of Lire, Glos, Pont-Saint-Pierre and Pacy. Juliana’s defence of the town of Breteuil was undone by the betrayal of the burgesses of the town. Henry besieged Juliana in the castle and, Orderic states, ‘However, as Solomon says there is nothing so bad as a bad woman’ – because she plotted to kill her father with a crossbow bolt, having requested a meeting with him.

Her bolt missed and she was forced to surrender the castle to her father, who refused to let her leave with dignity. ‘By the king’s command she was forced to leap down from the walls’ into the icy moat ‘shamefully with bare buttocks’; Orderic calls her an ‘unlucky amazon’. Her defeat and loss of the castle were not enough in Orderic’s narrative. The historicity of the tale is less important than the fact that Orderic uses voyeuristic detail to portray her in a demeaning and humiliating way.

Juliana was in a difficult political situation where conflicting family ties made her position as wife and daughter of protagonists difficult: her loyalty to her husband is, however, predominant. The allegation of her intention to commit patricide is indicative of Orderic’s awareness of her pain, rage and anger at the mutilation of her children. The image of women supporting their husbands runs through many contemporary sources.

Three key narrative sources, Orderic Vitalis, William of Newburgh and William of Malmesbury, confirm that powerful women played important roles in the decisive political campaigns of 1141. Orderic Vitalis states that Matilda countess of Chester and Hawise countess of Lincoln acted as decoys in a ruse by which earl Ranulf managed to capture Lincoln castle. They were ‘laughing and talking with the wife of the knight who ought to have been defending the castle’ when Ranulf went as though to escort his wife home.

Ranulf overpowered the king’s guards and seized the castle. This event was a turning point in the civil war and the catalyst of the further events which led to uneasy peace negotiations between the empress and King Stephen. William of Malmesbury in his Historia Novella likewise illustrates the role of wives in supporting their husbands in 1141. He shows that after the battle of Lincoln, which resulted in the capture of Earl Robert of Gloucester and King Stephen, Earl Robert knew he that he could rely on his wife, the countess Mabel, to support his political strategy.

When cajoled and then threatened by Stephen’s supporters to abandon the empress, he remained steadfast in his opposition, able to do so since he knew that his wife would send Stephen to Ireland should anything happen to him. William of Malmesbury also shows Mabel’s concern at the capture and imprisonment of her husband. He states that she was willing to accept a proposal detailing the exchange of the earl for less than his true ransom value, driven as she was by ‘a wife’s affection too eager for his release’.

Malmesbury then adds that Robert earl of Gloucester ‘with deeper judgement refused [the offer]’. Malmesbury is careful to stress Mabel’s reliance on her husband’s decisions even when he was imprisoned. Mabel’s political judgement is thus portrayed as affected by her emotions and weaker than that of her husband. Countess Mabel was an important linchpin in continuing the political strategy of the Angevin cause whilst Earl Robert was imprisoned, having a central role in securing the release of Earl Robert.

John of Worcester portrays both the countess Mabel and Stephen’s queen Matilda as proactively involved in the negotiating process. Both the queen and Mabel are portrayed as supporting their husbands, negotiating with each other through messengers. It is striking that there is no disparaging comment, only recognition of their actions as peacemakers, and indeed power brokers, involved in careful diplomacy.”

- Susan M. Johns, “Power and Portrayal.” in Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the Twelfth-Century Anglo-Norman Realm

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An unfinished portrait of Frances Stewart, Duchess of Richmond (1647-1702)

She was memorably depicted by Samuel Cooper in one of the sought-after sketches which remained in his studio on his death and which were eventually acquired by Charles II. Although the source here is apparently by Cooper, the image varies in detail from the sketch, and an unknown, but completed miniature by Cooper can be supposed to have been the basis for this enamel portrait.

#frances stewart#n: frances stewart#frances stewart duchess of richmond#house of stewart#noblewomen#17th century#artwork#*artwork#ours

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

They grow up so fast

#digital art#art#illustration#artists on tumblr#oc#douradart#oc: matilde#half orc#half giant#orc lady#noblewomen#fantasy character#ttrpg#dnd#akriata worldbuilding

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want this show back so bad or at least for them to resolve the cliffhanger. I have not forgiven ABC in almost five years.

#lashana lynch#still star crossed#rosaline capulet#abc#show#renaissance#black woman#black princess#black lady#noblewomen#castle#beautiful#black nobility#black royalty

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The meaning behind my username. 😊

#milady#english#word definition#dictionary#wordsnquotes#words#definitions#education#understanding#noblewomen#my name#name meanings#amethyst#gemstone#quartz

1 note

·

View note

Note

Thoughts on the Alysanne is Maegor's daughter AU? I feel like it has some interesting potential, and it vastly recontextualizes different parts of Jaehaehae (I do not like him sjsjsjs) and Alysanne's relationship (such as Jaehaehae's treatment of their daughters) but I wanna hear what you think about it!

I’ve touched on this a bit before but since you actually want to hear my thoughts, allow me to present to you my Jaehaerys Is The Goddamn Worst, And Alysanne Annoys Me Too: An Essay lmao but my answer is basically “yeah all of what you just said.”

I think it makes Alysanne much more palatable (to me) as a character because as she stands, she just fixates on forcing her daughters through these fucked up marriages at too young an age bc it traumatized her to be married and pregnant at 15 too but she’d never admit that being a willing participant in her own kidnapping by her brother-husband was the single worst thing that ever happened to her, and because Alysanne doesn’t want to admit it (and Jaehaerys would never see it as wrong or a mistake) F&B really shies away from delving into the fact that Alysanne is as deranged of a mother as Cersei is. So as she stands, she’s very flat to me because she’s presented very flatly and inconsistently. She’s so in love with Jaehaerys, she’s maritally raped by Jaehaerys, she’s a loving and doting mother, she forces her daughters into marriages when they’re the same too young age she was, she accuses her teenage girls of being scheming whores then gets angry when her husband accuses their teenage girls of being scheming whores, and worst of all we are just told “Maegelle tells them to make up so they do” so we don’t know why Alysanne gets over all of this. What is the point of riding a dragon when you never use that dragon to protect your daughters from unwanted teen marriages? We’re just not given a good enough justification for why her behavior is so weird and frustrating towards her daughters.

Make her Maegor’s daughter though…most of her behavior as an adult makes more sense. Like a worse version of Rhaenyra’s childhood almost - a father desperate for a son, but lowkey obsessed with his daughter, who makes all his hang ups about his parents the problems of every woman around him, except Maegor is out here blood sacrificing and torturing and starting wars and forcing babies on wives he discards quickly and brutally. Then here comes Jaehaerys on a white horse green dragon to save her from the horror her life has become, and he loves her so much he runs away with her even though Alyssa says they shouldn’t marry because people won’t like it. And they have beautiful children, and a beautiful marriage, and build a beautiful kingdom.

Then her pregnancies start getting dangerous. Gaemon, then Valerion, die. Alysanne thinks of the shriveled up mutants she called brothers, if Maegor’s taint has passed to her. Her perfect husband ignores her no, and forces Gael on her. Alysanne remembers that he said nothing to Rogar when Alyssa died, merely wept. Then her daughters start to die. Daella, Alyssa, Viserra, all within a few years. Then Jaehaerys makes Saera watch as he murders her boyfriend, calls her a whore, and says Alysanne cannot follow Saera to Lys. Alysanne thinks of Maegor torturing the Harroways over Alys’ presumed infidelity. Jaehaerys says he’s sorry, and her daughter badgers her into forgiving him, and she remembers how she helped Jaehaerys badger Alyssa into forgiving Rogar. Not two years later, Jaehaerys passes over Rhaenys. Alysanne thinks of how she was never enough for her father, how she felt so superior to Rhaena banished to Dragonstone and resented by Aerea, yet there she is dragging Gael away from court because she can’t stand to be with Jaehaerys. How her father was surrounded by dead women and dead babies and how Jaehaerys is surrounded by his own dead daughters, but surely she did the right thing, surely Maegor was worse, surely the realm is better off? Is he right to pass over Rhaenys? Is she enabling a man just as monstrous as her father? She will never decide, because Maegelle will guilt her about keeping Gael isolated at Dragonstone, and Alysanne will do as she’s told, just like Rhaena, and Alyssa, and Jeyne, Elinor, Ceryse, Alys, and Tyanna, just like every one of her daughters.

I do get why Alysanne is Alyssa & Aenys’ and not Maegor’s. The weird Targ babies, the line not descending from Visenya, Jaehaerys and Alysanne being held up as the perfect Targaryen couple specifically because they are brother and sister and dragon riders. I do even think canon Alysanne is likely traumatized by her time as a hostage on Dragonstone, and the ensuing war, and the trauma bond that caused with Jaehaerys, and it makes her idolize Jaehaerys, and then he isolates her at Dragonstone so he can swiftly and safely marry, groom, and knock her up. It’s not like,,,, a fun time, and it’s enough to make anyone crazy and weird about their daughters, but I think having her father be Maegor makes Alysanne herself much deeper because it gives her, as the most beloved Targaryen queen, a blood tie to the most hated Targaryen king, and a marriage to the most beloved Targaryen king. It fits better with a lot of the themes of the main series (again, imo) - forcing the spotlight on the outsiders to see how the affect the story from behind the scenes. The fall of Aegon’s sons, and The Long Reign, not told from the PoV or to serve the PoV of any of the kings or princes, but of the queen that tied them all together.

#anti jaehaerys i targaryen#f&b critical#fire and blood critical#asks#thesadboy#like he kind of does this with aenys & maegor by focusing on alyssa and rhaena and the wives and visenya.#but the Moment jaehaerys enters the scene he completely dominates it. the same way daemon and aemond do actually.#but this is not. it should not!! be their story. that’s not how the main series is told anyway!!#if f&b isn’t told by a dornish maester than it should have been written by a septa!!!#nuns wrote books!!!!!#rich noblewomen wrote novels and poetry!!!!!!!#GEORGE DO YOU READ WOMEN. I AM NO LONGER ASKING POLITELY.#i went to look for her mother and apparently this was just a mistake elio made and i’m even more depressed. i can’t believe i’m saying this#but elio damn your mind.#i bet he saw that and went ‘wait which one is her fucjing mother’ and george was like what in the goddamn hell are you talking about.#idk who would be her mother in this au. if we want to keep her within 3 ish years of jaehaerys it Has to be alys or ceryse. ceryse hightowe#is the hilarious and obvious choice. but don’t count out alys harroway second wife here either.#then there’s rhaena as her mother which with the canon timeline makes him 12 years older and isn’t THAT horrible let’s stop here actually.

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie Antoinette (2006)

#marie antoinette#sofia coppola#marie antoniette 2006#filmedit#perioddramaedit#kirsten dunst#moviegifs#filmgifs#costumedit#cinematv#hats#period drama#period costume#luxury#nobility#noblewomen#versailles#france#french queen#monarchy#french monarchy#aesthetic#queens#my edit

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Underrated artful dodger bit Belle saying "if you mean my house it's an estate"

#because it's hilarious but also! because I love you historical noblewomen who are fully aware of the power and implications of their status!#I LOVE YOU!!!!#she KNOWS her position in the colony!!!! SO refreshing so important to meeeee#the artful dodger#tad

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s a way a lady paramount could make her mark with the nobility? (Assuming her husband is encouraging of it) would it be lots of lady in waiting, granting people stuff, hosting them with her husband for feasts and provosts meals, beautifying her castle, and stuff like that? Or is there better ways of using soft and hard power to win over the nobility of the kingdom she married into?

I've answered a similar question before: https://beyondmistland.tumblr.com/post/692087065299533824/how-can-a-forgein-lady-win-the-smallfolk-over

Also, here is @warsofasoiaf's answer to the same question:

https://warsofasoiaf.tumblr.com/post/703355713987231744/whats-a-way-a-lady-paramount-could-make-her-mark

Thanks for the question, anon

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

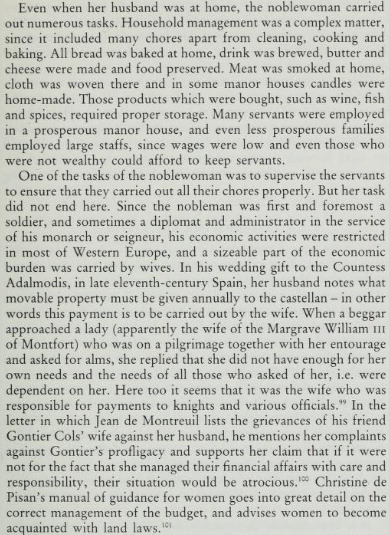

Women in the Middle Ages: Women in the Nobility

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"[Elizabeth Woodville's] piety as queen seems to have been broadly conventional for a fifteenth-century royal, encompassing pilgrimages, membership of various fraternities, a particular devotion to her name saint, notable generosity to the Carthusians, and the foundation of a chantry at Westminster after her son was born there. ['On other occasions she supported planned religious foundations in London, […] made generous gifts to Eton College, and petitioned the pope to extend the circumstances in which indulgences could be acquired by observing the feast of the Visitation']. One possible indicator of a more personal, and more sophisticated, thread in her piety is a book of Hours of the Guardian Angel which Sutton and Visser-Fuchs have argued was commissioned for her, very possibly at her request."

-J.L. Laynesmith, "Elizabeth Woodville: The Knight's Widow", "Later Plantagenet and Wars of the Roses Consorts: Power, Influence, Dynasty"

#historicwomendaily#elizabeth woodville#my post#friendly reminder that there's nothing indicating that Elizabeth was exceptionally pious or that her piety was 'beyond purely conventional'#(something first claimed by Anne Crawford who simultaneously claimed that Elizabeth was 'grasping and totally lacking in scruple' so...)#EW's piety as queen may have stood out compared to former 15th century predecessors and definitely stood out compared to her husband#but her actions in themselves were not especially novel or 'beyond normal' and by themselves don't indicate unusual piety on her part#As Laynesmith's more recent research observes they seem to have been 'broadly conventional'#A conclusion arrived at Derek Neal as well who also points out that in general queens and elite noblewomen simply had wider means#of 'visible material expression of [their] personal devotion' - and also emphasizes how we should look at their wider circumstances#to understand their actions (eg: the death of Elizabeth's son George in 1479 as a motivating factor)#It's nice that we know a bit about Elizabeth's more personal piety - for eg she seems to have developed an attachment to Westminster Abbey#It's possible her (outward) piety increased across her queenship - she undertook most of her religious projects in later years#But again - none of them indicate the *level* of her piety (ie: they don't indicate that she was beyond conventionally pious)#By 1475 it seems that contemporaries identified Cecily Neville as the most personally devout from the Yorkist family#(though Elizabeth and even Cecily's sons were far greater patrons)#I think people also assume this because of her retirement to Westminster post 1485#which doesn't work because 1) we don't actually know when she retired? as Laynesmith says there is no actual evidence for the traditional#date of 12 February 1487#2) she had very secular reasons for retiring (grief over the death of her children? her lack of dower lands or estates which most other#widows had? her options were very limited; choosing to reside in the abbey is not particularly surprising. it's a massive and unneeded jump#to claim that it was motivated solely by piety (especially because it wasn't a complete 'retirement' in the way people assume it was)#I think historians have a habit of using her piety as a GOTCHA!' point against her vilification - which is a flawed and stupid argument#Elizabeth could be the most pious individual in the world and still be the pantomime villain Ricardians/Yorkists claim she was#They're not mutually exclusive; this line of thinking is useless#I think this also stems from the fact that we simply know very little about Elizabeth as an individual (ie: her hobbies/interests)#certainly far less than we do for other prominent women Margaret of Anjou; Elizabeth of York;; Cecily Neville or Margaret Beaufort#and I think rather than emphasizing that gap of knowledge her historians merely try to fill it up with 'she was pious!'#which is ... an incredibly lackluster take. I think it's better to just acknowledge that we don't know much about this historical figure#ie: I do wish that her piety and patronage was emphasized more yes. but it shouldn't flip too far to the other side either.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a DM running two different CoS games, I'm so curious about yours. How did Things happen with Lydia? Is Victor around? It all sounds very very different from how I portray both her and Wachter.

Sorry for letting this sit so long! Finally had time to write stuff down. All the infos about our game's Lydia, the Vallakovich and Wachter family under the cut. Spoilers!

[CW for emotional (spousal) abuse, miscarriages, birth trauma]

So here's some general infos about Lydia and Fiona's backstories. We got to know Lydia as we were welcomed in the Vallakovich home by the oh so happy couple. In the middle of the night, no less, after just having been hunted through the woods by Morganta. My cleric PC spent a lot of time in the St. Andral church Lydia frequented, as he helped out Lucian.

Through his time with the Vallakovichs, who took a liking to him, he learned more about how deeply unhappy and sadly, emotionally abused Lydia was in her marriage.

What started out in a mutually loving relationship ended tragically onesided, as Vargas lost himself to his madness and paranoia over the years, while Lydia held onto hope that tomorrow, maybe another chance for them will come.

Viktor was almost a miracle to the couple. With miscarriages and stillbirths, Lydia grew more strained and anxious to provide an heir. When Viktor was finally born then, and survived, it was supposed to be a joyous occasion — but Lydia fell into postpartum depression and Vargas, already tilting towards his ideology, was no support to her.

Or Viktor, as Vargas was afraid to repeat the mistakes of his own abusive father's past. Viktor was practically raised by his nanny, who ended up as his first victim in his teleportation experiments. Lydia and Vargas never knew.

Fiona Wachter staged a coup, assassinated Vargas and almost Lydia and Viktor as well. So Lydia was there on the stage when everything escalated. She was saved, and Viktor teleported away — now caught in a teleportation loop after aiming for magic too powerful.

Lydia was completely broken after this, but embraced a second chance and a new chapter in life.

Fiona's storyline is similar as to the one in canon I believe, though some things were toned down. Ties to Ravenloft, cultist, though one centered around a prophecy of the sun coming back to Barovia. Our DM linked Lydia's and Fiona's stories, so that they grew up as childhood friends, though the relationship strained more and more during Vargas' reign. Viktor drove Stella insane, Lydia, due to the All Will Be Well! ideology was a terrible friend during Fiona's time of grief. Stella's madness was Fiona's breaking point, and she aimed to eradicate all of the Vallakovichs.

#asks#replies#lydia petrovna#fiona wachter#curse of strahd#thx for coming to my noblewomen of vallaki ted talk#hope this answered the question

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

young leandra and malcolm doodle but you can hear maurevar carver in the background going “malcolm. malcolm. please focus on the open flame in your hand. MALCOLM. the OPEN FLAME”

#malcolm hawke#leandra amell#doodle tag#im committing to kirkwall noblewomen wearing french hoods if they wont give me anything to work with#wait orlesian hoods

149 notes

·

View notes