#olympias

Text

~ Medallion with Olympias.

Date: ca. A.D. 215-243

Period: Imperial Roman

Medium: Gold

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient history#roman#archaeology#Roman Empire#Medallion with Olympias#olympias#gold#imperial Period#ca. A.D. 215#ca. A.D. 243

932 notes

·

View notes

Text

Details from the room of Cupid and Psyche in Palazzo Te, Giulio Romano, 1526-28

#art history#art#italian art#aesthethic#greek mythology#ancient greece#roman mythology#giulio romano#frescoes#palazzo te#mantua#mantova#cupid#psyche#cupid and psyche#zeus#olympias#banquet#bacchanalia#faun#16th century#rinascimento

429 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Old and new

Olympias is a reconstruction of an ancient Athenian trireme and a great example of experimental archaeology. It is also a commissioned ship in the Greek Navy.

999 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeologists claim to have cracked the code within the Great Tumulus of Vergina, claiming to confirm the identities of Alexander the Great's father, son and other family, with the evidence found there.

The treasures unearthed, including armor and personal artifacts, as well as tell-tale bone wear and tear, which they put together with historic evidence to that not only adds a new chapter to ancient history but also shed light on the legendary conqueror's familial ties. This revelation comes with a shocking twist that played a pivotal role in shaping Alexander the Great's ascension to the throne.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

new dnd party art >:3

left to right:

tulin: she/they

cyra: she/her (@juniperrrrrrr)

olympias: she/her

bev: she/they/any (me)

mal: they/them

winika: she/her (@doeeyes-art)

#dnd#dungeons and dragons#ocs#other people's ocs#half elf#cleric#fire genasi#paladin#rogue#rat#tiefling#barbarian#warlock#tulin#cyra#olympias#bed#mal#winika#my art

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

I found your blog recently and I can't stop reading it! it's amazing really :) also sorry if i have any mistake, english is not my first language.

I wanted to ask something: Were Alexander's generals jealous of Hephaestion because of his relationship with Alexander? I imagine that in some way they did feel something like that, but is there any conclusive evidence that says how they feel about it?

Macedonian officers were a bunch of sharks, with Alexander as the Great White

My header is the tl;dr version.

We know at least Krateros was jealous of Hephaistion; the sources tell us as much. Alexander even invented a cute little way of dealing with it, calling Hephaistion Philalexandros (Alexander loving or friend-of-Alexander) while Krateros was Philobasileus (king loving or friend-of-the-king). Hephaistion also appears to have tangled with Eumenes, although Eumenes tangled with a lot of people, from what I can tell. And, at least earlier in the campaign, Hephaistion and Krateros might have been, if not friends, at least friendly. But once Hephaistion rose in importance, he was in Krateros’s way.

Basically, all the fellows in Alexander’s orbit were in competition for Alexander’s affection, just as they’d later be in competition for Alexander’s empire after he died (the Era of the Successors or Diadochi).

Remember, in the ancient (pre-Christian) world, humility was not a virtue, and a GOOD person helped his friends and hurt his enemies. None of this “turn the other cheek” business, or “When they go low, we go high.” When they went low, you were expected to cut their throat as they bent.

That said, Curtius (Rufus) at least paints a picture of Hephaistion as someone careful in how he exercised his influence. In Curtius’s introduction of him in his history, he says Hephaistion had more freedom to upbraid the king than anybody else, but exercised it as if given by Alexander, not taken by himself. Elsewhere, Curtius calls him charming. In contrast, Plutarch (or at least Plutarch’s sources) paint a less flattering picture. I think which view modern historians accept depends on which primary source we trust more (or read first). 😉

Only in Plutarch do we find the episode of him pulling swords with Krateros. Curtius doesn’t mention it, nor does Diodoros or Arrian (Justin is too brief). But Diodoros does give the Philalexandros/Philobasileus line (when he recounts H.’s death). Diodoros also records a probably spurious letter Hephaistion supposedly wrote to Olympias, telling her to stop quarreling with him in her correspondence with Alexander. This is not a real letter and may owe to another incident where Alexander was reading a letter from her while sitting next to Hephaistion—who apparently leaned in to read with him. Alexander didn’t stop him but put his seal ring on his lips. I suspect Hephaistion regularly read his mail, but this time people happened to be watching.

Most of the quarrels related about Hephaistion appear to occur later—once his importance at the court had risen. And whatever you read in other historians (Green, Heckel, Anson, Cartledge, Worthington), he doesn’t appear to have been any more quarrelsome than anybody else—and maybe less, if Curtius can be trusted.

But basically, yes, sure, the person loved best by Alexander would be the natural target of others’ envy.

#asks#hephaistion#hephaestion#krateros#craterus#eumenes#alexander the great#alexander of macedon#olympias#curtius#plutarch#Classics#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#tagamemnon

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Based on this post from @suburbanbeatnik. There are some others that unfortunately I couldn't mention due to limited space, so I picked the most famous/the ones I liked the most.

#greece#ancient greece#greek history#history#history couples#alexander the great#hephaistion#seleucus#seleucis i nikator#apama#stratonice#antiochus i#pericles#aspasia#pelopidas#epaminondas#gorgo#leonidas#olympias#philip#socrates#xanthippe#phryne#praxiteles#harmodius#aristogeiton#cleopatra#perdiccas#it's pretty clear which couple is gonna win#ah well let's see who is gonna end up second place

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine:

Olympias sneaking into your room at night as you two are secret lovers.

——————————————————————————-

(NOT MY GIF!)

(Olympias X Reader)

——————————————————————————-

(TAGS)

#old hollywood#oldhollywoodedit#Olympias#angelina jolie#gif imagine#moviegifs#images#imagine#fame dr#x reader#fluff#y/n#romeo and juliet#secret lovers#the love witch#285 bc

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Ancient authors, while generally hostile to Olympias, are not uniformly so. Plutarch, for instance, although he provides an extremely negative picture of Olympias in his life of Alexander (e.g., 2.9, 9.5, 10.1, 4, 68.5), offers a different and much more positive picture of her in the Moralia (141b-c, 243d, 799e). Even Justin, notorious for his implausible account of Olympias' supposed outrageous behavior after the death of Philip (9.7.10-14), gives Olympias a long and heroic death scene (14.6.6- 13). Diodorus, although generally critical of Olympias, also grants her a noble death (19.51.5). Indeed, female bravery, especially in the face of death, and often characterized as man-like, is admired by many ancient authors.

Whereas the current historiographical trend in scholarship about the reign of Alexander disdains biography and resists speculation about the motivation of the great conqueror, most of those who deal with Olympias confidently assign motives to her actions, motives which are usually negative and almost always personal rather than political. The ancient sources, biased or not, are not always the basis for this assignment of motivation. Indeed, unpleasant motivation attributed to Olympias, while similar in ancient sources and modern scholarship, is not identical. Ancient sources tend to depict Olympias as motivated primarily by her difficult personality (they often imply that she liked to make trouble for trouble's sake) and by her natural nastiness, whereas modern scholarship tends to stress vengeance and something very close to madness, despite the fact that no ancient source characterizes Olympias' actions as mad and that very little stress is put on vengeance as her motivation. The actions of male contemporaries of Olympias, however brutal, are narrated in neutral fashion and their motivation is not usually perused, although apparently it is assumed to be rational if ruthless, whereas the actions of Olympias are described with a host of negative adjectives and adverbs and are assumed (although rarely argued) to be emotionally motivated.

Moreover, perhaps because of this unwarranted confidence in ascribing motivation to Olympias, modern scholarship sometimes supplements the already subjective judgments of antiquity. Scenarios and assumptions about Olympias have emerged that have little or no foundation in the ancient evidence. Many, for instance, assume that Olympias and her daughter Cleopatra did not get on and base their explanations for various political events on that assumption, yet no ancient source offers a shred of proof for this assumption. In fact, several sources describe mother and daughter as acting in concert for shared political goals and several more imply further concerted action. Similarly, many modern authorities assert that Olympias was universally unpopular in Macedonia after she brought about the deaths of Philip Arrhidaeus and his wife Adea Eurydice, whereas the narratives of Diodorus and Justin provide a more complex and nuanced picture in which Olympias emerges as a controversial figure, loathed by some and loyally supported by others.

This unfortunate state of scholarly affairs has had several consequences, none of them good. If we assume that scholars owe their subjects, groups or individuals, mass phenomena or personalities, some sort of fairness and balanced judgment, then clearly Olympias has not received it. Moreover, because of our unbalanced reading of this particular historical figure, our interpretation of Macedonian political events has been distorted. Distortion is especially a problem with the treatment of the period after the death of Alexander, and with the analysis of the reasons for the collapse of the dynasty which had ruled Macedonia from its historical beginnings. Problems with the treatment of Olympias' career have also affected our understanding of the most central of Macedonian institutions, the monarchy, and particularly the relationship of female members of the royal family to that institution.

Those who have recognized the hostile treatment of Olympias in the sources have attributed it, following Tarn, to propaganda created by Cassander to justify his elimination of her. While Cassander's efforts did doubtless play a part in the attitude of some of the surviving sources, it would be wrong to assume that he was the sole source of the hostility against Olympias.

The image of Olympias created by our sources results from the accumulation of many layers of prejudice. Greek unease with monarchy came partly from the role women played in succession politics; that Macedonian monarchy was polygamous only made for greater unease. A well-known but often carelessly read passage in Plutarch (Alex. 9.5) makes clear Greek distrust of Macedonian court politics: "The troubles in Philip's household produced many grounds for quarrels and differences because his marriages and love-affairs contaminated the basileia [kingdom or perhaps monarchy] with the customs of the women's quarters." (He follows this remark with an attack on Olympias' ill-nature to which we shall shortly turn.) It is a classic statement of Greek views about women and men and the association of the former with private life and the latter with public life: any mixing of the two worlds will lead to trouble. Hornblower has suggested that the emergence of Macedon as a great power and the consequent appearance for the first time of women like Olympias with political power in the Hellenic as opposed to the non-Hellenic world presented Greek historians with the problem of dealing with a new phenomenon, one they could not ignore.

Naturally, most Greeks disliked the role royal women played in Macedonian public life. In Athens, respectable women were, if possible, not even named in public, yet Athenian politicians refer to Olympias by name in the assembly, without even a patronymic (Hyp. Eux. 25; Aeschines 3.233). Shopping trips done for her sake (Aeschines 3.233) and acts of piety she performed (Hyp. Eux. 19) became matters of public discussion. She had a long public relationship with the Athenian assembly (Diod. 17.108.7, 18.65.1-7; Hyp. Eux. 25). Alexander sometimes liked to play the civilized Greek who did not indulge in backward Macedonian ways (e.g., Plut. Alex. 51.2). This pose may help to explain anecdotes about him and Olympias in which he takes the role of the conventional Greek male, reproving her for inappropriate behavior, and in one case implying that her actions were more typical of Epirus than Macedon (Plut. Alex. 39.12, 68.5; Diod. 18.49.4). All anecdotal material about the early life of Alexander should be treated with great distrust, but, true or not, if these anecdotes were actually generated by Alexander himself, they should be viewed in the context of his desire to be seen as Greek.

Much hostility is specific to Olympias herself: she is treated in a way that neither her daughter nor her rivals are. Some of this difference arises from the sources saying so much more about Olympias than about the others. Her career spanned three reigns and as the mother of Alexander the Great, she became a character in the vast body of anecdote his exploits generated. One wonders whether a lengthy Greek treatment of Cynnane, for instance, might not have demonstrated hostility to her aggressive militarism.

Clearly, though, some of the hostility of the sources to Olympias results from factors more essential than length or breadth of coverage. The sources object to her personality, as they interpret it. Consider the rest of the Plutarch passage just discussed: "the extremely difficult nature of Olympias, a jealous and indignant woman, exaggerated these difficulties because she provoked her son." Numerous anecdotes survive that have made her difficultness proverbial. Alexander jokes that she exacts a high price for his ten-month stay (Arr. 7.12.4). Her quarrels with Hephaestion and with Antipater remain vague, but the idea seems to be that she demonstrates her "difficultness” by involving herself in public affairs, often by unsuccessfully attempting to influence her son.

Since so many scholars have accepted the view of Olympias presented in these stories about her quarrels, it is important to note something at once simple and yet usually ignored: these stories do have a point of view and it is not that of citizens of governments with universal suffrage. The sources assume first that Olympias should not be active in public matters and therefore characterize such activity as interference. In fact we do not know that she was not acting within her role as king's mother; Hammond has suggested that she had a formal constitutional role during Alexander's reign. Even if we reject that suggestion, we might still conclude that her activity was well within Macedonian political patterns, how- ever much Antipater may not have liked it. They assume further that a woman who acts in such a fashion is difficult (xakeni), yet the great majority of modern scholars are unlikely to share such an assumption. Moreover, few scholars waste time wondering whether Alexander or Antipater or Attalus was "difficult"; we take it for granted that they were, that competitiveness and assertiveness were norms in the Macedonian court. Without realizing it, we have simply mirrored the cultural judgments of our source.”

A glance at the etymology of the word "virago" in Latin as well as in English will make my point clearer. In both languages, a virago is a person whose actions conform to cultural expectations of males ... So Olympias is a genuine virago, a woman who violated every expectation the Greeks had about women, but the antipathy her unconventionality inspired in the Greek world is a cultural assessment, not an eternal truth. Since all the surviving sources for the reign of Alexander date from Roman times and two of them were written in Latin, we should remember that Roman dislike of political women was also intense.

Not all the problems with hostility toward Olympias lie in the sources, nor does the nature of the sources explain why they have so frequently been read uncritically. We must recognize the fact that the image of the virago remains an extremely potent one in our own culture and it is very hard to give up a figure we so love to hate. The likes of the traditional figure of Olympias can be found virtually any night on television soap operas, wearing shoulder-pads, scheming, and making the plot go. In the past women so depicted were often royal-Eleanor of Aquitaine for instance - because royal women were often the only prominent women and certainly the only ones with a modicum of political power. What we have here is a kind of topos, which like many topoi continues to have powerful appeal. I shall refrain from considering exactly why we continue to be troubled by the association of women with power and why stereotypes associated with such women persist, but it is essential that we recognize and resist this fatal attraction.

- Elizabeth Carney, “Olympias and the Image of the Virago”

#historicwomendaily#history#olympias#alexander the great#macedonian history#ancient greece#mine#queue

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phillip and Olympias would be one of those disastrous co-parents that would say yes to their kid ONLY because the other parent said no.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2004 Alexander Olympias

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Olympias a replica of an ancient Athenian trireme of 480 B.C.

#tall ship#olympias#greek war triremes#archeological experiment#ancient greek#480 bc#ancient seafaring

791 notes

·

View notes

Text

#damn#ancient greece#women#history#the more you know#nice#artemisia I of caria#olympias#cynane#wow#female war leaders#tiktok#tiktoks#@taniberlo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

亚历山大的身世之谜

(这一段故事是典型的绯闻野史。历史大环境是真的,狗血的剧情细节则有些值得怀疑。)

话说古埃及文明,那真是个灿烂辉煌,雄霸一方。但兴盛了近三千年,从第一王朝(First Dynasty,3100 BC)发展到了第三十王朝(Thirtieth Dynasty,340 BC),终于如残阳西下,日渐式微。

王朝衰落的原因之一,是东方日益强大的古波斯帝国。时间往前退一百多年,上一代的波斯君主一心一意的想吞并希腊,而且差一点儿就成功了:要不是 马拉松战役,温泉关战役(电影300),萨拉米斯战役,普拉提亚战役 中希腊人的卓越表现,希腊估摸着就要姓“波”而不姓“希”了。

波斯强攻未果,修生养息了一段时间,不再去啃希腊这块硬骨头,而是把目光指向了西南方的古埃及帝国。

此时的埃及法老,正是本文的主角,最后一位埃及本土君主,内克塔内布二世(Nectanebo II)。

(detail)…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

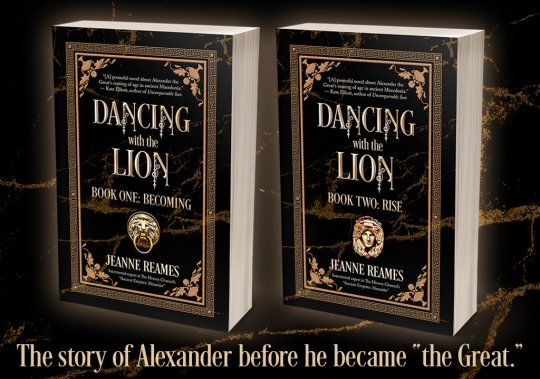

Dancing with the Lion

Dancing with the Lion is now off Kindle Unlimited, which means it is BACK on a variety of other sites for normal purchase. (Amazon demands an exclusive for KU, so it's only available on Amazon during the KU stretch.)

So, for anyone waiting who didn't want to pay Amazon, you can now find the novels at B&N, Kobo, etc.

But if you want an ebook, and it doesn't matter to you, please get it directly from Riptide Pub. The price is no different, and I get a tad more of the Royalties (in pennies, but hey): Book 1 Becoming and Book 2 Rise. Or both novels as a pair for a little less each, if you know in advance that you want them both.

You can also purchase a physical copy, but the publisher told me they no longer handle print-on-demand because Amazon, B&N, etc., owned the machines anyway, and they're no longer "renting" them to publishers. So basically, all boutique publishers now have to go through Amazon. Classic monopoly. If you would like a print copy and don't want to put money in Amazon's pocket, you can buy it directly from Indiebound: Book 1. (They don't seem to have book 2 for whatever reason. May just not be up yet.)

#alexander the great#historical novels#historical fiction#dancing with the lion#dwtl#ancient greece#ancient macedonia#hephaistion#alexander x hephaestion#alexander x hephaistion#philip ii#olympias

8 notes

·

View notes