#overreach

Photo

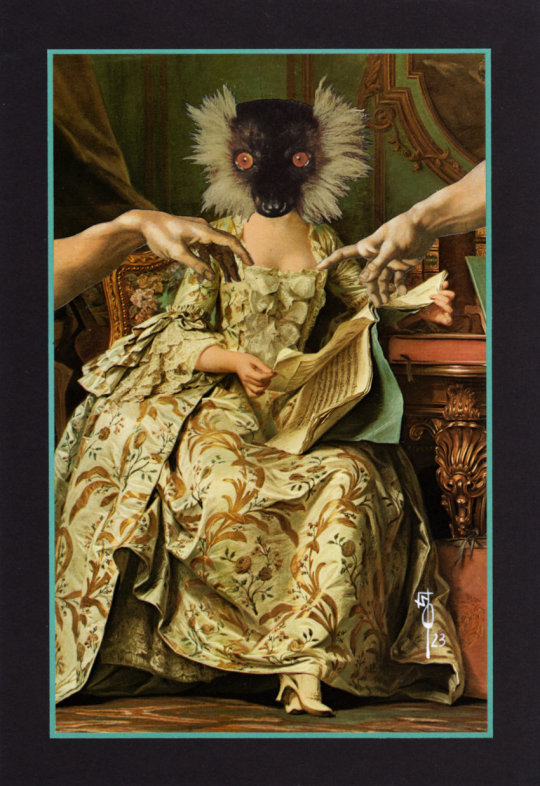

Wallace Polsom, Life During Wartime: Like Father, Like Son (2023), paper collage, 20.4 x 29.6 cm.

#wallace polsom#life during wartime#a bridge too far#paper collage#collage#collage art#art#artists on tumblr#analog collage#contemporary art#handmade collage#handcut collage#21st century#wallacepolsom2023#surreal#surrealism#fantasy#art history#creation#overreach#satire#dominion

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2005, Putin famously lamented the collapse of the Soviet Union as the “great geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century. It would be ironic if his war completes the Soviet dissolution.

– Thomas E. Ricks, military and national security journalist, writing at the New York Times.

Putin is no time lord, he can't turn back the clock no matter how much he wishes to be Stalin. The Soviet Union is DEAD DEAD DEAD and nobody can bring it back.

Nobody has done more in this century to strengthen NATO, make former parts of the USSR more distrustful of Russia, and damage the Russian economy than Vladimir Putin. The invasion of Ukraine was an overreach of Shakespearean magnitude.

Putin is Russia's self-inflicted catastrophe of the 21st century. And it may take much of the rest of this century to sort out the mess he's created.

#invasion of ukraine#russia#vladimir putin#thomas e. ricks#collapse of ussr#soviet union#overreach#putin's poor judgement#russia is losing the war#stand with ukraine#россия#владимир путин#путин хуйло#путин - военный преступник#бывший ссср#экономическая отсталость россии#союз постсоветских клептократических ватников#россия проигрывает войну#руки прочь от украины!#геть з україни#україна переможе#зеленський виявився крутішим за путіна#слава україні!#героям слава!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

We live in a culture where companies are too quick to fulfill police requests for personal data on users–and it’s a situation ripe for abuse.

#eff#electronic frontier foundation#privacy#invasion of privacy#all cops are bastards#all cops are bad#law enforcement#data analytics#datascience#industry data#data#abuse#government overreach#overreach#class war#cybersecurity#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#internet#cybercore#software#telecommunications

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

NY mayor tries to have NBC reporter arrested after questions about official duties

youtube

this is a very ugly confrontation and rarely do you see white men act like this towards white women. that's what makes this so interesting

he has lost his mind. quite frankly he should lose his seat

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your local sheriff can now sign up to become a fascist warlord--or perhaps already has...

#right-wing#CSPOA#sheriffs determining what is and is not Constitutional#sheriff as final authority#overreach#undermining democracy#undermining the rule of law

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

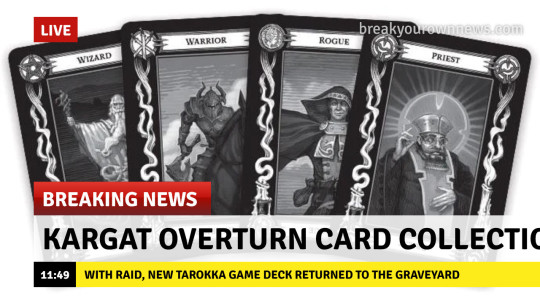

Yesterday, Kargat leadership sicked a squad of enforcers upon a noted collector of tarokka decks. Apparently fearing the loss of the most important state secrets (e.g.- Azalin Rex is a furry) through divination with an experimental deck, the goon squad confiscated the merchandise and respectfully left the collector tied up and hanging upside down from the rafters like an apprehended supervillain. It was also later revealed the Kargat had performed one of their famously delicate interviews on some of the neighbors on the collector’s whereabouts while he was away. Nice to see that the goon squad left a reminder that they stopped by.

#kargat#overreach#overreactions#card decks#goon squads#raids#confiscations#tarokka decks#demiplanar news#demiplanar demagogue#tabletop satire

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Tell me that you know nothing about American history, without telling me you know nothing about American history.

To compare the horror of Jim Crow laws to transgenderism is to diminish what life under apartheid was like for African-Americans and completely dismiss the serious violations of civil and human rights carried out by bitter conservatives who were smarting after having their collective asses kicked by the Union army and their economy based on chattel slavery demolished forever.

It also completely mischaracterizes and demonizes the experiences and existence of transfolk. One has nothing whatsoever to do with the other. This is a true “apples to armadillos” comparison.

It is at these moments we need to pause and consider seriously the minuscule number of transfolk in our population. To hear conservatives talk about it, they must believe that there are thousands of times more transfolk than there possibly could be.

In other words, conservatives are whipping themselves into a frenzy over a complete non-issue. Again. For the thousandth time.

How about we let people decide for themselves, along with the advice and counsel of their doctors? How about we allow the people who have studied gender dysphoria, who are up-to-date on the latest research, etc. help parents determine a medical plan for their children who think that they may be trans?

If you truly care about children, conservatives, and if you truly believe that parents should have the final say on what their children are taught, etc. then how can you dare impose onto parents your own uninformed and bigoted stance against transfolk?

Let the people who are best qualified to make such decisions. That would be the parents of the child and their doctor. Can you at least pretend to be ideologically consistent?

#candace owens#gop#maga#conservative#trans#transgender#transfolk#bigotry#republican#discrimination#jim crow#apartheid#segregation#trans rights are human rights#trans rights#gender dysphoria#psychology#psychiatry#overreach#lgbt+

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#pandemic amnesty#medical tyranny#medical rights#plandemic#pandemic#covid#lockdowns#overreach#cdc#hospitals#doctors#nurses#medical industry

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

In a letter to the president, 26 Republican attorneys general demanded the Biden administration withdraw its Department of Agriculture’s Title IX interpretation, which will take billions of dollars in National School Lunch Program funding away from schools that don’t let biological males use the girls' bathroom or compete in girls’ sports. The department's interpretation violated the Administrative Procedures Act, since it was issued as a memorandum rather than a proposed rule for the public to comment on, the attorneys general wrote.

The Biden administration has a history of going around the public when issuing policies, Matt Bowman, a senior counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom, told the Washington Free Beacon. Before the Supreme Court blocked it in January, a mandate without public comment from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration required that workers at businesses with 100 or more employees get vaccinated or submit a negative COVID test weekly.

With the exception of New Hampshire attorney general John Formella, every Republican attorney general joined the coalition, which is led by Tennessee attorney general Herbert Slatery.

#Washington Free Beacon#Elizabeth Troutman#school lunches#state attorneys#Biden administration#funding#homosexuality#Title IX#Department of Agriculture#National School Lunch Program#Administrative Procedures Act#Republicans#OSHA#covid vaccines#emphasis added#overreach

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#constitution#founding fathers#limit power#overreach#SCOTUS#Article V#Convention of States#Power to the people#Youtube

0 notes

Link

Musk’s reign of terror at Twitter continues. He is now banning prominent journalists who report on the chaos Musk has created at Twitter.

Musk is acting like the Putin of tech. He is overreaching and should expect to get his butt kicked in the near future.

The European Union is now exploring sanctions against Musk’s Twitter.

The EU has threatened Twitter owner Elon Musk with sanctions after several journalists covering the company had their accounts abruptly suspended.

Reporters for the New York Times, CNN and the Washington Post were among those locked out of their accounts.

EU commissioner Vera Jourova warned that the EU's Digital Services Act requires respect of media freedom.

"Elon Musk should be aware of that. There are red lines. And sanctions, soon," she tweeted.

Yes, Commissioner Jourová mentioned that on Twitter. Maybe Musk will ban her too.

The list of banned journalists also includes The Intercept's Micha Lee, Mashable's Matt Binder, and independent reporters Aaron Rupar and Tony Webster.

A spokesman for the New York Times called the suspensions "questionable and unfortunate", and said neither the paper nor reporter Ryan Mac received any explanation for the action.

CNN said the "impulsive and unjustified suspension of a number of reporters... is concerning but not surprising". It has asked Twitter for an explanation and will "re-evaluate our relationship based on that response".

CNN's Donie O'Sullivan, whose account was among those suspended, said the move was significant for "the potential chilling impact" it could have for journalists, particularly those who cover Mr Musk's other companies.

Musk is unintentionally promoting Mastodon by banning Mastodon accounts at Twitter.

Twitter also suspended the official account of Mastodon, which has emerged as an alternative to Twitter since Mr Musk bought it for $44bn in October.

It came after Mastodon used Twitter to promote Mr Sweeney's new account on Thursday, according to the New York Times.

Links to individual Mastodon accounts also appeared to be banned. An error message notified users that links to Mastodon had been "identified" as "potentially harmful" by Twitter or its partners.

Musk will just keep on banning people he doesn’t like. It will eventually become Truth Social – but with Teslas.

If Musk’s true intention is to kill Twitter, he’s been quite successful at that so far.

In the words of MIT Technology Review...

We’re witnessing the brain death of Twitter

The state of Twitter since Elon Musk’s takeover feels like a brain death: the processes that keep it online are somehow still beating, but what Twitter was before Musk is never coming back.

People who have invested a lot of time and effort into Twitter may be in denial about its fate. But those pretending that things will miraculously return to the good old days of pre-Musk are fooling themselves. The smart people are looking for alternatives.

#twitter#elon musk#musk the mad#overreach#european union#eu#sanctions#věra jourová#banning of journalists#censorship#the brain death of twitter#mastadon#the bird is enslaved#truth social with teslas#the pre-musk twitter isn't coming back#alternatives to twitter

45 notes

·

View notes

Link

Crappy politics

#Canada#education#politics#BC#NDP#overreach#Zionism#hasbara#Palestine solidarity#repression#Selina Robinson

0 notes

Text

So I help warn others , I was in Urban Planet in my city YESTERDAY, today I got this Chinese phishing scam , blocked now , just so you all know if I have to go into urban planet maybe take cash only - no cards as they may send phishing scams and or to your phone .

0 notes

Link

Doc's Thought of the Day is up. Today Doc discuss the growing corruption of the United States government and other elements of the culture war.

Website - https://www.thatsonpoint.info

Merch - https://teespring.com/stores/thats-on-point-merch

Follow Us On;

Bitchute-https://www.bitchute.com/channel/8SXcz1rqDyu7/

YouTube-https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRNHroldv9kuaatarS7uclA

Minds-https://www.minds.com/thatsonpoint/

Top Clips: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCn_fZ4JhHN05YLijsdmkYSQ/

Paler:https://parler.com/profile/DocComeau

Support Us On;

Subscribe Star-https://www.subscribestar.com/that-s-on-point

Patreon-https://www.patreon.com/ThatsOnPoint?fan_landing=tru

#democrats#dnc#doccomeau#entertainment#fbi#gop#government#news#overreach#podcast#podcasts#politics#republicans#thatsonpoint#thoughtoftheday#top#unconstitutional

0 notes

Link

By Serhii Plokhy

In December 2021 I accepted an invitation from the former prime minister of Ukraine, Oleksiy Honcharuk, to attend a conference that he had co-organized at Stanford. I wanted to hear first-hand what Honcharuk, who had headed Volodymyr Zelensky’s first government, thought about the chances of a major war between Russia and Ukraine – a subject that had been dominating the media for weeks.

Honcharuk assured me that there would be no war, at least not in the next few months. With Joe Biden focusing the world’s attention on Vladimir Putin’s preparations to strike, he explained, the timing was not good for Moscow. In 2014 Russia’s annexation of Crimea had come as a surprise. This time everyone was ready – the Ukrainians with their new army and the West solidly committed to punishing Russia with heavy economic penalties. Putin would have to wait it out.

Honcharuk’s argument seemed plausible. But common sense is not necessarily a reliable guide to predicting the future. On February 21, 2022, three days before the invasion, Putin formally recognized the independence of the two puppet states that Russia had created in 2014 when it occupied part of Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region. He also laid claim to Ukraine as a whole. “Since time immemorial, the people living in the southwest of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians and Orthodox Christians”, he asserted in his speech, going on to argue that Ukraine was an artificial creation of Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

Putin was determined to turn the clock of history all the way back to the Russian Empire, whose rulers had posited the existence of a tripartite nation consisting of Great Russians, Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belarusians). This would be his principal contribution to a project that had in effect begun immediately following the collapse of the USSR in December 1991, with Moscow moving swiftly to re-establish control of the post-Soviet space.

In the wake of 1991, the Kremlin had set about modernizing the remains of the Soviet army in order to achieve its foreign and domestic political objectives. The First Chechen War, launched by Boris Yeltsin in 1994 to crush the Chechen drive for independence, inaugurated this new era of post-Soviet warfare. The Second Chechen War, which began in 1999, opened the door to Putin’s election as president and launched what Mark Galeotti, in Putin’s Wars: From Chechnya to Ukraine, calls the “Wars of Russian Assertion”. Packing his narrative with detail and analysis, Galeotti argues that in Russia, more than in many other countries, the armed forces became “a symbol of national pride and power”. For Putin Russia’s military is “not just a guarantee of its security”. It is also the means of making Russia “a credible international power again”.

The Chechen wars were followed by the use of military force outside the borders of the Russian Federation, in the form of the invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the seizure of Crimea in spring 2014, which immediately revealed itself as a prelude to the hybrid warfare launched in Donbas a few weeks later. Putin’s goal in Georgia and Ukraine was to stop those countries’ drift towards the West, but in both cases his actions had the opposite effect. When Ukraine sought closer integration with the western democracies, Putin abandoned what Galeotti calls “his usual cautious approach” and attempted an all-out invasion and partial occupation of the country.

Galeotti advances a number of reasons for Putin’s decision, including his Covid isolation and possible illness, which may have made him feel as if his “personal clock was ticking faster than he had once assumed”. In the author’s view Putin did not have to invade in order to win his “political war” against Ukraine: the credible threat of invasion sufficed to drive away western investors, making Ukraine’s European aspirations all but moot. But the master of the Kremlin miscalculated. Galeotti rightly suggests that Putin planned a “police action”, not a war, which he then tried to fight his own way by dismissing the opinions of the military brass. The invasion, Galeotti says, was “not the generals’ war”. One can almost feel Putin’s disappointment when Galeotti observes that “arguably, 20 years of high-spending military reform was wasted in 20 days”.

In Overreach: The inside story of Putin’s war against Ukraine, Owen Matthews explains how Russia’s attempts to reform its military were destroyed by the political hubris of the man who initiated and promoted that reform. Based on the author’s intimate knowledge of Russia and its political life, this is the best available account of the country’s road to war. The list of prominent Russians interviewed in the years leading to all-out conflict includes Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov, who is thanked for “chats in his Kremlin office and over dinner that have been tours de force of adamantine defiance of reality”, and Sergei Kiriyenko, who is not only first deputy chief of staff of the presidential administration, but also responsible for running the occupied territories in Ukraine.

Matthews is convinced, and claims repeatedly, that the Kremlin’s war on Ukraine is first and foremost a war against the West. He argues that the underlying motive for the invasion is the same as the one behind the poisoning and then imprisonment of Putin’s main political opponent, Alexei Navalny: to protect Putin’s regime from what the president and his circle of former KGB operatives regard as western encroachments. Thus, for Matthews, the most productive question is not why Putin unleashed an all-out war against Ukraine, but why he did not do so earlier. His answer is that, given the botched American withdrawal from Afghanistan and Angela Merkel’s departure from the political scene, Putin considered the moment opportune for curbing western influence in Ukraine. Indeed, Russia had a war chest of $650 billion – oil and gas money stashed away by Putin for just such an offensive – and now was the time to strike.

Matthews begins the countdown to invasion with the one and only meeting between Putin and Zelensky, arranged and attended by the leaders of France and Germany in Paris in December 2019. Zelensky made no concessions to Putin, despite earlier promises by Ukrainian representatives. Under pressure from his domestic opposition, the Ukrainian president refused to remove his troops from the frontline in Donbas, to allow elections in Donbas before Russian soldiers had left the region or to change the constitution in such a way as to give Donbas veto power over Ukrainian foreign policy.

Soon after the failed summit Putin fired Vladislav Surkov, his point man in Donbas affairs. It was then, argues Matthews, that the Kremlin began its slide towards military confrontation. Isolated by the Covid epidemic, Putin had time to study Russian imperial history and write his own disquisition on Russo-Ukrainian relations. The role of security officials such as Nikolai Patrushev, who retained direct access to the president, increased tremendously.

In the spring of 2021 Putin moved his troops to the borders of Ukraine in an effort to blackmail Zelensky and the West into allowing the Trojan horse of the Donbas puppet states to enter the Ukrainian constitutional fortress. The threat failed, but with American policy in disarray after the retreat from Kabul, the Kremlin decided to achieve its goals in Ukraine by military means. Matthews designates Putin’s security men as the main hawks – Patrushev, the secretary of the security council, and Alexander Bortnikov, the head of the FSB, or internal counterintelligence and secret police. By early December the defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, and the military brass had sped up their planning for the war.

When Putin called a meeting of the security council on February 21, 2022, in order to discuss the alleged “independence” of the Donbas puppet republics, Patrushev, Bortnikov and Shoigu were probably the only members who knew that his real plan was to go to war. The rest suspected what was going on and simply hoped for the best. Describing the atmosphere at the meeting, Matthews quotes Galeotti: “King Lear meets James Bond’s Ernst Stavro Blofeld”. The invasion began three days later.

If Matthews presents the best current analysis of the countdown to war, Luke Harding provides unparalleled coverage of the invasion as experienced on the Ukrainian side. Harding was in Kyiv when the attack began and has visited Ukraine repeatedly since then. He vividly describes the atmosphere on the streets in the early hours of the war and tracks changes in the public mood as the Russians withdrew from Kyiv while battles continued in eastern and southern Ukraine. His account covers developments up to September 2022.

No figure better reflected, embodied and articulated the transformation of Ukrainian society by the war than the country’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, whose patriotic credentials were unclear and often challenged by the opposition during his first two and a half years in office. A few weeks before the Russian attack he gave a joint press conference with the then British prime minister, Boris Johnson. Harding, who was invited as a member of the press, finds the Ukrainian president to have been “somewhat behind the curve of history – struggling to respond to developments, and to the mighty storm bearing down upon him”. While Johnson spoke of “imminent” Russian aggression, Zelensky called it “possible”. That was the line he took with both visiting foreign dignitaries and his own people.

Despite the talk of imminent invasion in Washington and London, Kyiv did not mobilize its army reserves until Russian tanks crossed the border and Russian missiles awakened Zelensky and his family at the presidential quarters outside Kyiv on February 24. But having publicly downplayed the possibility of war, he quickly became an inspirational symbol of Ukrainian resistance once the invasion began. The new Zelensky was born with the sound of those first explosions. He had shown courage earlier, but now it took on added purpose and significance. If his talent as an actor had allowed him to gauge the mood of his audience to attain the presidency, he could now draw on it not just to provoke laughter or calm frayed nerves, but to make Ukrainians discover their inner strength. He became what Harding, quoting the Guardian columnist Jonathan Freedland, calls “Churchill with an iPhone”.

In effect, Zelensky’s story reflects that of the Ukrainian people, who dreamt of peace, but were forced into war by Russian aggression. Their resolve to fight back was not crushed but solidified by the invaders’ atrocities, such as the cold-blooded killing of Volodymyr, a young resident of Bucha. His apparent mistake was to give three Russian soldiers his phone when they demanded one. It is not clear what the Russians found there, but they took Volodymyr away, tortured him, broke his arm and demanded that he tell them where the Nazis were. Their actions were gruesome evidence of the effectiveness of Putin’s propaganda about waging war against Nazis – this in a country with the only Jewish head of state outside Israel, and one of the few post-Soviet nations with a working democracy.

There were no Nazis in Bucha, and Volodymyr kept telling his captors that he knew nothing. They took him for further interrogation. His aunt, Natasha, got a glimpse of him after he was tortured, but then lost track of him. She would find his body in a nearby cellar after Ukrainian forces liberated Bucha. Harding, who interviewed Natasha soon after, quotes her: “They made him kneel and shot him in the side of the head, through the ear”.

The Ukrainians have been fighting and dying not only to save their lives, but also to defend their democratic ideals. “Freedom is our religion” was the message on a poster that covered a burnt building on Kyiv’s Maidan Square after the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. Harding’s interviews show that the phrase was no mere slogan. “A leitmotif of Ukrainian literature, historiography, and philosophy is opposition to the centralized idea of state and universe”, Harding quotes Volodymyr Yermolenko, a leading public intellectual in Kyiv, as saying. Olena Chebeliuk, a history teacher from Lviv, tells the author: “We don’t like dictators here … If he tries to make a dictatorship in Ukraine, he will fail”.

The war destroyed whatever sense of East Slavic unity and national brotherhood still existed in Ukraine. It also turned the most pro-Russian of Ukrainians into the Kremlin’s sworn enemies. Before the war Oleksandr Vilkul, the military governor of Zelensky’s home town, Kryvyi Rih, was one of the leaders of what many considered a pro-Russian opposition to the president. Yet, despite being offered a prominent position in a Russian-backed government, he refused appeals to support the invasion. Instead he led his fellow citizens in their fight against the invaders. “They believe in Lenin, victory in the Second World War, and the nuclear arsenal”, he says of the Russians, adding that he always knew Russia to have been dangerous, but did not expect it to become a “crazy monster”. Asked about the outcome of the war, Vilkul is confident of Ukraine’s victory. He tells Harding: “Like Hitler, Putin will destroy his own country”.

Galeotti, Matthews and Harding give their own answers to the question of how the war is likely to end. Galeotti divides Putin’s long incumbency into two parts – the successful decade of the 2000s and the disastrous period after 2010, characterized by the squandering of what he achieved during his previous two terms in office. He acknowledges the damage that the war has done to Russia, but hopes that its new generation of leaders will be more pragmatic, if no less nationalistic, than the current one. Matthews seems less optimistic, suggesting that the war “opened a Pandora’s box of alternative futures for Russia that were much more scary than Putin’s regime had ever been”. He envisions two scenarios for Ukraine: a negotiated settlement or endless warfare. Harding, taking a historical perspective, sounds the most optimistic. “Ukraine had not won the war – or not yet”, he writes, adding that, in the words of the country’s national anthem, it “had not yet perished” either. According to Harding, Ukraine has become a “proven state”.

Through the current war, Ukraine has indeed established its right to existence and shown that it is here to stay, regardless of how much longer the current regime survives in the Kremlin and what kind of rulers succeed it. What this means in historical perspective is that a war fuelled by the Kremlin’s misreading of the Russian and Ukrainian past, and its own desire to regain the great-power status of Soviet times, is destined to end in victory for Ukraine as an independent state and the defeat of Russia as an imperial one. This is not just the best-case outcome of the war, but also its most realistic one.

The main question is when that will happen and at what cost. To hasten the outcome and minimize the damage means staying the course and helping Ukraine

to prevail. This in turn will help Russia to free itself from the hubris of the empire that it once owned, but is now a chimera that holds it in its thrall.

0 notes

Link

By Serhii Plokhy

In December 2021 I accepted an invitation from the former prime minister of Ukraine, Oleksiy Honcharuk, to attend a conference that he had co-organized at Stanford. I wanted to hear first-hand what Honcharuk, who had headed Volodymyr Zelensky’s first government, thought about the chances of a major war between Russia and Ukraine – a subject that had been dominating the media for weeks.

Honcharuk assured me that there would be no war, at least not in the next few months. With Joe Biden focusing the world’s attention on Vladimir Putin’s preparations to strike, he explained, the timing was not good for Moscow. In 2014 Russia’s annexation of Crimea had come as a surprise. This time everyone was ready – the Ukrainians with their new army and the West solidly committed to punishing Russia with heavy economic penalties. Putin would have to wait it out.

Honcharuk’s argument seemed plausible. But common sense is not necessarily a reliable guide to predicting the future. On February 21, 2022, three days before the invasion, Putin formally recognized the independence of the two puppet states that Russia had created in 2014 when it occupied part of Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region. He also laid claim to Ukraine as a whole. “Since time immemorial, the people living in the southwest of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians and Orthodox Christians”, he asserted in his speech, going on to argue that Ukraine was an artificial creation of Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

Putin was determined to turn the clock of history all the way back to the Russian Empire, whose rulers had posited the existence of a tripartite nation consisting of Great Russians, Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belarusians). This would be his principal contribution to a project that had in effect begun immediately following the collapse of the USSR in December 1991, with Moscow moving swiftly to re-establish control of the post-Soviet space.

In the wake of 1991, the Kremlin had set about modernizing the remains of the Soviet army in order to achieve its foreign and domestic political objectives. The First Chechen War, launched by Boris Yeltsin in 1994 to crush the Chechen drive for independence, inaugurated this new era of post-Soviet warfare. The Second Chechen War, which began in 1999, opened the door to Putin’s election as president and launched what Mark Galeotti, in Putin’s Wars: From Chechnya to Ukraine, calls the “Wars of Russian Assertion”. Packing his narrative with detail and analysis, Galeotti argues that in Russia, more than in many other countries, the armed forces became “a symbol of national pride and power”. For Putin Russia’s military is “not just a guarantee of its security”. It is also the means of making Russia “a credible international power again”.

The Chechen wars were followed by the use of military force outside the borders of the Russian Federation, in the form of the invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the seizure of Crimea in spring 2014, which immediately revealed itself as a prelude to the hybrid warfare launched in Donbas a few weeks later. Putin’s goal in Georgia and Ukraine was to stop those countries’ drift towards the West, but in both cases his actions had the opposite effect. When Ukraine sought closer integration with the western democracies, Putin abandoned what Galeotti calls “his usual cautious approach” and attempted an all-out invasion and partial occupation of the country.

Galeotti advances a number of reasons for Putin’s decision, including his Covid isolation and possible illness, which may have made him feel as if his “personal clock was ticking faster than he had once assumed”. In the author’s view Putin did not have to invade in order to win his “political war” against Ukraine: the credible threat of invasion sufficed to drive away western investors, making Ukraine’s European aspirations all but moot. But the master of the Kremlin miscalculated. Galeotti rightly suggests that Putin planned a “police action”, not a war, which he then tried to fight his own way by dismissing the opinions of the military brass. The invasion, Galeotti says, was “not the generals’ war”. One can almost feel Putin’s disappointment when Galeotti observes that “arguably, 20 years of high-spending military reform was wasted in 20 days”.

In Overreach: The inside story of Putin’s war against Ukraine, Owen Matthews explains how Russia’s attempts to reform its military were destroyed by the political hubris of the man who initiated and promoted that reform. Based on the author’s intimate knowledge of Russia and its political life, this is the best available account of the country’s road to war. The list of prominent Russians interviewed in the years leading to all-out conflict includes Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov, who is thanked for “chats in his Kremlin office and over dinner that have been tours de force of adamantine defiance of reality”, and Sergei Kiriyenko, who is not only first deputy chief of staff of the presidential administration, but also responsible for running the occupied territories in Ukraine.

Matthews is convinced, and claims repeatedly, that the Kremlin’s war on Ukraine is first and foremost a war against the West. He argues that the underlying motive for the invasion is the same as the one behind the poisoning and then imprisonment of Putin’s main political opponent, Alexei Navalny: to protect Putin’s regime from what the president and his circle of former KGB operatives regard as western encroachments. Thus, for Matthews, the most productive question is not why Putin unleashed an all-out war against Ukraine, but why he did not do so earlier. His answer is that, given the botched American withdrawal from Afghanistan and Angela Merkel’s departure from the political scene, Putin considered the moment opportune for curbing western influence in Ukraine. Indeed, Russia had a war chest of $650 billion – oil and gas money stashed away by Putin for just such an offensive – and now was the time to strike.

Matthews begins the countdown to invasion with the one and only meeting between Putin and Zelensky, arranged and attended by the leaders of France and Germany in Paris in December 2019. Zelensky made no concessions to Putin, despite earlier promises by Ukrainian representatives. Under pressure from his domestic opposition, the Ukrainian president refused to remove his troops from the frontline in Donbas, to allow elections in Donbas before Russian soldiers had left the region or to change the constitution in such a way as to give Donbas veto power over Ukrainian foreign policy.

Soon after the failed summit Putin fired Vladislav Surkov, his point man in Donbas affairs. It was then, argues Matthews, that the Kremlin began its slide towards military confrontation. Isolated by the Covid epidemic, Putin had time to study Russian imperial history and write his own disquisition on Russo-Ukrainian relations. The role of security officials such as Nikolai Patrushev, who retained direct access to the president, increased tremendously.

In the spring of 2021 Putin moved his troops to the borders of Ukraine in an effort to blackmail Zelensky and the West into allowing the Trojan horse of the Donbas puppet states to enter the Ukrainian constitutional fortress. The threat failed, but with American policy in disarray after the retreat from Kabul, the Kremlin decided to achieve its goals in Ukraine by military means. Matthews designates Putin’s security men as the main hawks – Patrushev, the secretary of the security council, and Alexander Bortnikov, the head of the FSB, or internal counterintelligence and secret police. By early December the defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, and the military brass had sped up their planning for the war.

When Putin called a meeting of the security council on February 21, 2022, in order to discuss the alleged “independence” of the Donbas puppet republics, Patrushev, Bortnikov and Shoigu were probably the only members who knew that his real plan was to go to war. The rest suspected what was going on and simply hoped for the best. Describing the atmosphere at the meeting, Matthews quotes Galeotti: “King Lear meets James Bond’s Ernst Stavro Blofeld”. The invasion began three days later.

If Matthews presents the best current analysis of the countdown to war, Luke Harding provides unparalleled coverage of the invasion as experienced on the Ukrainian side. Harding was in Kyiv when the attack began and has visited Ukraine repeatedly since then. He vividly describes the atmosphere on the streets in the early hours of the war and tracks changes in the public mood as the Russians withdrew from Kyiv while battles continued in eastern and southern Ukraine. His account covers developments up to September 2022.

No figure better reflected, embodied and articulated the transformation of Ukrainian society by the war than the country’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, whose patriotic credentials were unclear and often challenged by the opposition during his first two and a half years in office. A few weeks before the Russian attack he gave a joint press conference with the then British prime minister, Boris Johnson. Harding, who was invited as a member of the press, finds the Ukrainian president to have been “somewhat behind the curve of history – struggling to respond to developments, and to the mighty storm bearing down upon him”. While Johnson spoke of “imminent” Russian aggression, Zelensky called it “possible”. That was the line he took with both visiting foreign dignitaries and his own people.

Despite the talk of imminent invasion in Washington and London, Kyiv did not mobilize its army reserves until Russian tanks crossed the border and Russian missiles awakened Zelensky and his family at the presidential quarters outside Kyiv on February 24. But having publicly downplayed the possibility of war, he quickly became an inspirational symbol of Ukrainian resistance once the invasion began. The new Zelensky was born with the sound of those first explosions. He had shown courage earlier, but now it took on added purpose and significance. If his talent as an actor had allowed him to gauge the mood of his audience to attain the presidency, he could now draw on it not just to provoke laughter or calm frayed nerves, but to make Ukrainians discover their inner strength. He became what Harding, quoting the Guardian columnist Jonathan Freedland, calls “Churchill with an iPhone”.

In effect, Zelensky’s story reflects that of the Ukrainian people, who dreamt of peace, but were forced into war by Russian aggression. Their resolve to fight back was not crushed but solidified by the invaders’ atrocities, such as the cold-blooded killing of Volodymyr, a young resident of Bucha. His apparent mistake was to give three Russian soldiers his phone when they demanded one. It is not clear what the Russians found there, but they took Volodymyr away, tortured him, broke his arm and demanded that he tell them where the Nazis were. Their actions were gruesome evidence of the effectiveness of Putin’s propaganda about waging war against Nazis – this in a country with the only Jewish head of state outside Israel, and one of the few post-Soviet nations with a working democracy.

There were no Nazis in Bucha, and Volodymyr kept telling his captors that he knew nothing. They took him for further interrogation. His aunt, Natasha, got a glimpse of him after he was tortured, but then lost track of him. She would find his body in a nearby cellar after Ukrainian forces liberated Bucha. Harding, who interviewed Natasha soon after, quotes her: “They made him kneel and shot him in the side of the head, through the ear”.

The Ukrainians have been fighting and dying not only to save their lives, but also to defend their democratic ideals. “Freedom is our religion” was the message on a poster that covered a burnt building on Kyiv’s Maidan Square after the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. Harding’s interviews show that the phrase was no mere slogan. “A leitmotif of Ukrainian literature, historiography, and philosophy is opposition to the centralized idea of state and universe”, Harding quotes Volodymyr Yermolenko, a leading public intellectual in Kyiv, as saying. Olena Chebeliuk, a history teacher from Lviv, tells the author: “We don’t like dictators here … If he tries to make a dictatorship in Ukraine, he will fail”.

The war destroyed whatever sense of East Slavic unity and national brotherhood still existed in Ukraine. It also turned the most pro-Russian of Ukrainians into the Kremlin’s sworn enemies. Before the war Oleksandr Vilkul, the military governor of Zelensky’s home town, Kryvyi Rih, was one of the leaders of what many considered a pro-Russian opposition to the president. Yet, despite being offered a prominent position in a Russian-backed government, he refused appeals to support the invasion. Instead he led his fellow citizens in their fight against the invaders. “They believe in Lenin, victory in the Second World War, and the nuclear arsenal”, he says of the Russians, adding that he always knew Russia to have been dangerous, but did not expect it to become a “crazy monster”. Asked about the outcome of the war, Vilkul is confident of Ukraine’s victory. He tells Harding: “Like Hitler, Putin will destroy his own country”.

Galeotti, Matthews and Harding give their own answers to the question of how the war is likely to end. Galeotti divides Putin’s long incumbency into two parts – the successful decade of the 2000s and the disastrous period after 2010, characterized by the squandering of what he achieved during his previous two terms in office. He acknowledges the damage that the war has done to Russia, but hopes that its new generation of leaders will be more pragmatic, if no less nationalistic, than the current one. Matthews seems less optimistic, suggesting that the war “opened a Pandora’s box of alternative futures for Russia that were much more scary than Putin’s regime had ever been”. He envisions two scenarios for Ukraine: a negotiated settlement or endless warfare. Harding, taking a historical perspective, sounds the most optimistic. “Ukraine had not won the war – or not yet”, he writes, adding that, in the words of the country’s national anthem, it “had not yet perished” either. According to Harding, Ukraine has become a “proven state”.

Through the current war, Ukraine has indeed established its right to existence and shown that it is here to stay, regardless of how much longer the current regime survives in the Kremlin and what kind of rulers succeed it. What this means in historical perspective is that a war fuelled by the Kremlin’s misreading of the Russian and Ukrainian past, and its own desire to regain the great-power status of Soviet times, is destined to end in victory for Ukraine as an independent state and the defeat of Russia as an imperial one. This is not just the best-case outcome of the war, but also its most realistic one.

The main question is when that will happen and at what cost. To hasten the outcome and minimize the damage means staying the course and helping Ukraine

to prevail. This in turn will help Russia to free itself from the hubris of the empire that it once owned, but is now a chimera that holds it in its thrall.

0 notes