#perfect memento in strict sense

Photo

There are a lot of fanon explanations for why Mokou’s Perfect Memento is so blatantly misinformative, but I think an underappreciated possibility is that Mokou just showed up to the Hieda manor and went “Hey, it would be totally badass if you made people think I was some kind of ninja!” and Akyuu, being the good(?) parent(?) that she is(?) said “Sure, dear” and wrote that in even though it made no sense.

#touhou#touhou project#fujiwara no mokou#hieda no akyuu#perfect memento in strict sense#the ''parent(?)'' bit is in reference to the Hieda no Are = Fujiwara no Fuhito hypothesis#which as far as I know is really poorly supported and not seriously considered by actual academics#but it is an interesting potential character dynamic and I like the motif of immortal daughter - reincarnating parent#so I will simply ignore the ahistoricalness in favour of Drama

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hieda no Akyuu

#Hieda no Akyuu#touhou#touhou project#touhou Perfect Memento in Strict Sense#touhou PMiSS#Perfect Memento in Strict Sense#Akyuu Hieda#touhou fanart#touhou kitties#touhou kitties project#touhou kitties 2023#art#my art#digital art#cat#cat au

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Akyuu: (detailed description of a hypothetical future event, which it would be pointless for ZUN to put that much detail into unless it was actually relevant somehow)

Akyuu: But that'll never happen, right? Yeah no that's definitely not gonna happen

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was reading through some of perfect memento in strict sense and I like this part

and this one kinda hit...

#touhou#hieda no akyuu#perfect memento in strict sense#ahi's ramblings#existential stuff#'but ahi' you say 'didnt this book originally come out over 15 years ago why did you wait until now to read this'#well you see there was this meeting at work and it was supposed to be two hours but it ended up going over a bit and#:P

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

I forgot I didn't post about it on here, but I finally finished this big project. It's all the playable L1 Touhou LostWord characters that were available in 2023.

("L1" basically means "classic non-alternate universe versions of the main cast". No AU versions, they're meant to be the originals.)

This is everyone from Touhou 6 to Touhou 18, including the spinoffs. Most of the print work characters are here too, but some notable absences include Rinnosuke (NPC only), Miyoi (they did "beach AU Miyoi" but classic Miyoi is NPC only), Tokiko (NPC only, treated more like a special enemy than an actual character) and Mizuchi (not in the game at all).

I didn't include Maribel/Mima and Renko/Shinki, mostly because they're treated as alternate universe versions, but also because I don't have both units.

I recommend using the timestamps in the description (blame YouTube for not turning my timestamps into proper chapters)

#touhou project#touhou lostword#touhou fangames#embodiment of scarlet devil#perfect cherry blossom#immaterial and missing power#imperishable night#phantasmagoria of flower view#mountain of faith#scarlet weather rhapsody#touhou sangetsusei#perfect memento in strict sense#forbidden scrollery#silent sinner in blue#subterranean animism#undefined fantastic object#double spoiler#ten desires#double dealing character#urban legend in limbo#hopeless masquerade#legacy of lunatic kingdom#antinomy of common flowers#hidden star in four seasons#unconnected marketeers#wily beast and weakest creature#sunken fossil world#wild and horned hermit#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

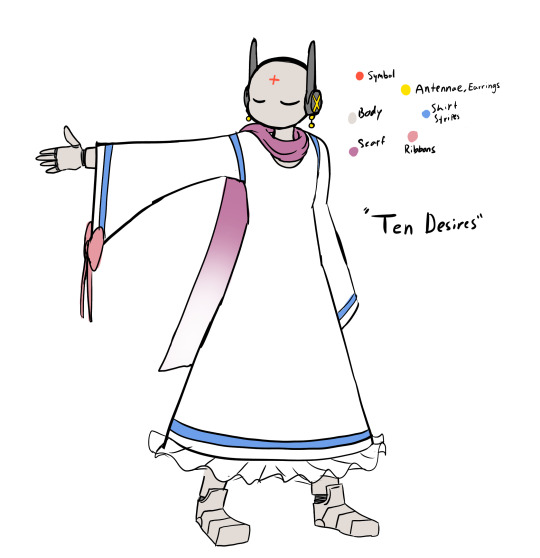

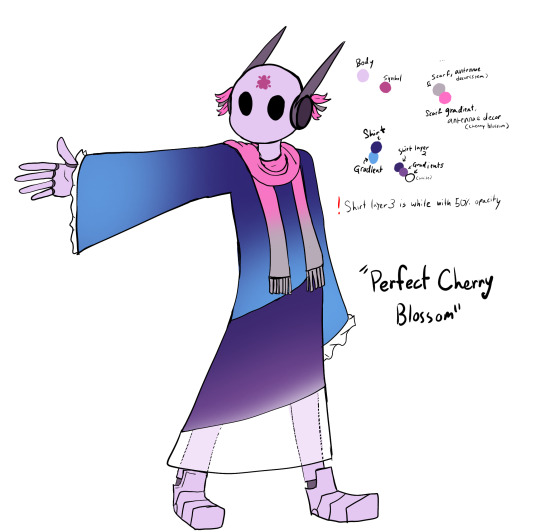

iterator ocs i made based on touhou media names except one (len'en jumpscare)

this is Hidden Star in Four Seasons (star for short).

they're the youngest out of the group (younger than pebbles), very childlike and the shortest at 5'6". #1 slugcat lover. if you wanna imagine their structure then imagine pebbles but no cancer i guess

this is Perfect Memento in Strict Sense (memento for short).

she is the oldest out of the group (younger than moon, still has the blocky cramped and exposed design like moon's structure but slightly less maybe lol) and is the senior. she stores information in books she makes and is decent at art due to illustrating them on her own (she doesnt dislike data pearls). to pass time, she likes reading her books to star to whom she is a guardian figure to.

this is Silent Sinner in Blue (silent for short).

he rejects karma, does not work on the problem at all because he thinks its stupid. tries to break every karma level. is also the troublemaker of the group and has probably sent the iterator equivalent to a zip bomb to every local iterator at least once (he'd call it a prank). his trolling is his fucked up way of making friends.

this is Ten Desires (desires for short)

they believe highly in karma and try to abide by the levels (besides breaks they cant avoid) and dislikes silent bc theyre who he likes to pester the most. theyre kinda chill about their religious stuff and are on good terms with everyone ...except silent ofc. they have positive opinions on the ancients.

this is Subterranean Animism (Subterranean for short)

has a fascination with general wildlife and watches it when passing time, also loves talking about it. loves slugcats and centipedes. when he sees a slugcat in combat he tends to root for the slugcat. dislikes worm grass, is only Really unsettled by the large patches but still ehhhh about the small patches. highly extroverted and talks to others frequently, friendly guy.

this is Gathering Reverie (reverie for short).

she likes to spread misinformation, silent's buddy and is overall a prankster like him (just doesnt nearly kill her victims...). genuinely is into astronomy and likes watching the sky around her structure when it turns night.

this is Perfect Cherry Blossom (Cherry for short)

shy and nervous guy, more comfortable around iterators who are friendly (aka not silent and reverie lol but subterranean might be a little exhausting sometimes). wants an unmodified slugcat as a pet and dislikes insect creatures like dropwigs and centipedes.

this is Evanescent Existence (evanescent for short). the len'en jumpscare!!!!!

my most recent iterator oc as of this post and is the tallest at 6'3". very logical guy and likes debating n all that jazz. supercomputer but emphasis on the "computer" basically.

thats it lol. i hope yall enjoyed me being a good artist but a mediocre character writer bye

#rain world#iterator oc#minu's iterator oc hidden star in four seasons#minu's iterator oc perfect memento in strict sense#minu's iterator oc silent sinner in blue#minu's iterator oc ten desires#minu's iterator oc subterranean animism#minu's iterator oc gathering reverie#minu's iterator oc perfect cherry blossom#minu's iterator oc evanescent existence#rain world oc#i have too many of them what do i do.......#art#minu's art

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

i actually quite like the little whirring sound my cd drive makes heheh

#i already ripped all my music cds so im just installing my games now#i mean like. i have them on steam already. except perfect cherry blossom which isnt. on steam yet. guess im finally gonna own it legally LOL#but having extra backups never hurts!#i dont think im gonna start super-publicly sharing around my cd rips but if anyone happens to want some cute little wav files of zun's music#im happy to throw them up on google drive for ya if you shoot me a dm#currently i have bohemian archive in japanese red + perfect memento in strict sense + grimoire of marisa's cds#as well as all 5 akyu's untouched score cds#and ghostly field club + changeability of strange dream + retrospective 53 minutes#aaaand finally gouyoku ibun/sunken fossil world's ost#planning on going shopping for more soon tho hehehehheheheh

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

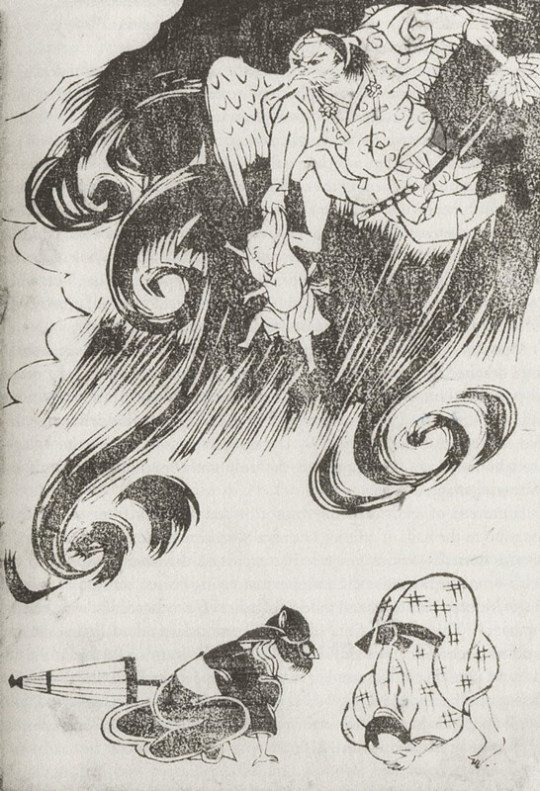

"Tenma, boss of the tengu". Exploring the "heavenly demon(s)"

The identity of Tenma, the leader of tengu in Touhou, remains a mystery. I think only ZUN can solve it - if he ever chooses to, obviously. Therefore, this is not quite an article meant to prove I figured out who Tenma is. Instead, it presents the origin of this name, and introduces a handful of figures in various contexts portrayed as leaders of the tengu who I think would be interesting candidates for the position of Tenma.

My additional goal is to show that even though popculture tends to portray all tengu as basically interchangeable, there is actually a fair share of unique tales about specific named members of this category. Corrupt monks! Vengeful spirits! Visitors from far off lands! There’s even a sea monster converted to Buddhism! Obviously, this isn’t supposed to be a list of every single named tengu and every single story. It’s not even a list of all of my favorite tengu. It’s simply an attempt at convincing you that digging deeper into tengu background is worth it - and in particular that there is still a lot to speculate about when it comes to their leader in Touhou. It’s some of the best oc free real estate in the series, really.

Due to technical difficulties, the bibliography is included as a Google Docs link rather than a part of the article. I'm sorry.

From Mara to tengu: the development of the concept of tenma

Silhouette of a tengu negotiating with Kanako in WaHH 38, sometimes labeled as Tenma on fan sites through debatable exegesis.

As we originally learned in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, Gensokyo’s tengu are ruled by an individual named Tenma (天魔). Akyuu simply describes them as the “tengu’s boss” and provides no further information. While some additional tidbits have since surfaced here and there, they largely remain a mystery. Next to Chang’e, the unseen fourth deva of the mountain and the fourth Beast Realm figurehead they’re easily the highest profile unseen character in the entire series.

While in absence of information on the contrary we cannot necessarily assume that Tenma isn’t a given name in Touhou, ZUN did not actually come up with this term. It has been a significant part of tengu background at least since the Kamakura period. It can be translated as “heavenly demon”, and it’s a shortened form of Dairokuten Maō (第六天魔王), “Demon King of Sixth Heaven”, the Japanese name of Mara. Tenma is explained as a synonym of Mara’s “personal name” Hajun (波旬; Sanskrit Pāpīyas) for instance in the treatise Makashikan (摩訶止観; translation of Chinese Móhē Zhǐguān, “Great Cessation and Insight”).

Is that all there is to the mystery of Tenma? For what it’s worth, a possible reference to the full form of Mara’s name can be found in a description of Okina’s ability card in Unconnected Marketeers, which mentions “Tenma living in paradise”. I don’t think this is very strong evidence, though.

Touhou aside, it is hard to deny tengu are fundamentally tied to Mara. They are directly described as his subjects in Buddhist works such as Soseki Musō’s (1275–1351) Muchū mondō (夢中問答集; “Questions and Answers in Dreams”) and Unshō’s (運敞; 1614–1693) Jakushōdō Kokkyōshū (寂照堂谷響集). However, it needs to be stressed that a being referred to as Tenma does not necessarily have to be Mara himself.

A plurality of Maras theoretically became possible as soon as the belief this name didn’t designate an individual, but rather a position which could be held by various individuals or a category of beings developed in Buddhism. The former idea already appears in the Māratajjanīya, a part of the Theravada Buddhist Majjhima Nikāya, dated to the late first millennium BCE or early first millennium CE. Maudgalyāyana, one of the disciples of the historical Buddha, reveals in it that he was (a) Mara in a past life, and thus can easily notice the presence of the present Mara. The shift from a singular Mara (魔, mo) to an assortment of “demon kings” (魔王, mowang) is also well documented in early Buddhist sources from China.

As a curiosity it’s worth noting that even though the terms mo and mowang originally referred to strictly Buddhist demons, they were also incorporated into Daoist traditions, especially Lingbao and Shangqing. For example the former school's central text Duren Jing (度人經; “Scripture for Universal Salvation”) maintains that multiple mowang exist.

While some of these “demon kings” are tempters not too dissimilar from their Buddhist forerunner (though what they obstruct is attaining the distinctly Daoist form of transcendence - in other words, immortality), others are portrayed as judges responsible for determining the fates of people in the afterlife. In later sources the term mo sometimes also refers to supernatural pathogens (generally 邪, xie or 邪氣, xiequi).

Sun Wukong and his fellow pilgrims battling the Bull Demon King on a mural from the Summer Palace in Beijing (wikimedia commons)

You don’t really need to look for any particularly obscure sources to see this transformation of Mara into a generic moniker, though - even the Bull Demon King from Journey to the West has the compound 魔王 in his name. Same goes for numerous other antagonists from this work.

When it comes to Japanese sources, it also doesn’t require looking for anything particularly obscure to find evidence in the belief in multiplicity of ma or tenma.

In the historical epic Heike Monogatari, emperor Go-Shirakawa implores Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin to explain the nature of tenma to him. He reveals that this term refers to monks and scholars who, despite nominally following Buddhism, lacked the mindset needed to attain enlightenment. He compares them to birds of prey, but also states they belong to the “dog species”. All of these are nods to well established beliefs about tengu, which I discussed in my previous article, with a reference to the writing of their name on top of that.

It comes as no surprise that right after that Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin specifies that “the wise men of the eight sects who become tenma are called tengu”. He also makes it clear the tenma are quite numerous: “nine out of ten will definitely become tenma and try to destroy the Law of Buddha,” he warns.

A plurality of tenma can also be found in assorted biographies of pious Buddhist reborn in a pure land, so-called ōjōden (往生伝). The Tendai treatise Asabashō (阿娑縛抄) attributes the ability to “subdue all tenma” - evidently a class of beings, not an individual - to Fudō Myōō.

Through the rest of the article, I will introduce some of these tenma - the most famous tengu. My goal is not to convince you that any of them is a uniquely plausible candidate for the role of the unseen Touhou Tenma - I merely would like to point out there are multiple interesting options.

The oneness of vice and virtue: Ryōgen, the ruler of Makai

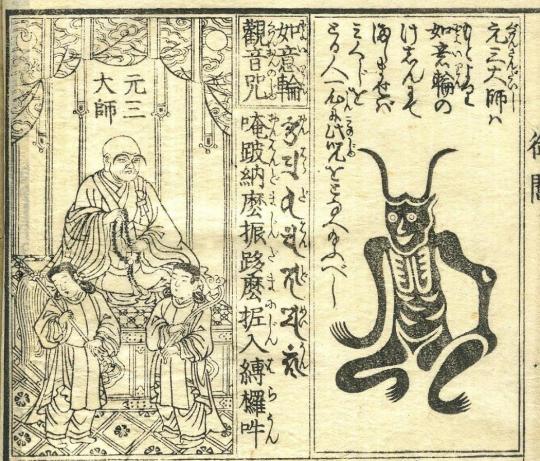

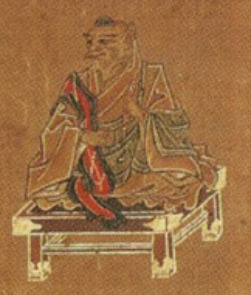

The historical Ryōgen (left) and his deomic alter ego Tsuno Daishi (wikimedia commons)

Before Ryōgen (912–985) came to be seen as a tengu, he was one of the most influential members of the Tendai school of Buddhism to ever live. He reformed the Enryaku-ji complex on Mt. Hiei, took part in numerous theological debates, and gained the favor of the imperial court by supposedly enabling the birth of an heir of emperor Murakami with his prayers. He was also renowned as a master of esoteric protective rituals.

The proponents of the Tendai establishment understood him as a fearsome protector of this tradition. As early as 50 years after his death, in the 1030s, he came to be identified as the reincarnation of Tendai’s founder Saichō. He was also considered a manifestation of one of the eight dragon kings, Uhatsura (優鉢羅; from Sanskrit Utpalaka). Ōe no Masafusa states that in this form he continued to protect Mt. Hiei, instead of being reborn in a pure land. This idea continued to spread, and by the end of the Kamakura period he came to be commonly revered as a protective figure by all strata of society. Haruko Wakabayashi notes that only Kūkai developed a similar cult in Japan as far as patriarchs of the esoteric Buddhist schools go.

It was not Ryōgen’s ability to navigate complex doctrinal debates about the interpretation of sutras that resulted in his popularity, but rather his esoteric skills. He was supposedly uniquely accomplished when it came to subduing anything which could be described as ma. In a Konjaku Monogatari tale I’ll discuss in more detail later, he effortlessly overcomes a tengu, for instance.

However, in addition to spiritual obstacles and demons, the ma he was supposed to conquer also included political opponents, rebels or brigands, as the Buddhist law and the interests of the state were understood as identical. Ryōgen’s efficiency was so great he came to be viewed as a manifestation of Fudo Myōō, one of the wisdom kings and the conqueror of ma par excellence.

Not everyone viewed Ryōgen positively, though. The earliest criticism came from his contemporaries. It was argued that he favored monks from aristocratic families, and that he lived in luxury unbefitting for a monk. Furthermore, numerous conflicts between monks erupted during his tenure as Enryakuji’s abbot, including the split between the Sanmon and Jimon lineages. Since in some cases this led to armed confrontations, later on he was blamed for essentially enabling the rise of militarized monks who commonly caused disturbances on Mt. Hiei.

The real breakthroughs were not these tangible “political” criticisms. Rather, it was the identification of Ryōgen as ma, which arose due to conflict between various schools of Buddhism in the early middle ages. Most commonly this meant portraying him as a tengu - as I explained in my previous article, the form arrogant or corrupt monks were believed to take. A variant tradition described him as an oni, though according to Bernard Faure this likely simply reflects a degree of interchangeability between them and tengu.

Ryōgen is arguably the most famous historical monk to be furnished with such a literary afterlife. An early example can be found in the Hōbutsushū from the twelfth century, which states that this was a result of his attachment to Enryaku-ji. In Jimon Kōsōki (寺門高僧記) it is instead his investment in doctrinal debates that made him unable to attain rebirth in a pure land.

A gathering of tengu leaders from Tengu Zōshi (wikimedia commons)

Since Ryōgen was no ordinary monk, his tengu self also had to be special. In the Tengu Zōshi (天狗草紙), he is described as the ruler of all tengu and the realm they inhabit, Makai (“world of ma”; also referred to as Tengudō). It's worth pointing out the notion of Makai being a place where monks turn into specific classes of supernatural beings is basically a core part of UFO’s plot, and in SoPM Miko even wonders if Byakuren shouldn’t be considered a tengu.

As a ruler of Makai, Ryōgen came to be referred to as a “demon king”, maō (魔王). An example can be found in the historical epic Taiheiki, where he is described as one of the “great demon kings” (大魔王, daimaō) who debate how to cause chaos in Japan. He is assisted by vengeful spirits of the emperors Sutoku (more on him later), Go-Toba and Go-Daigo; two members of the Minamoto clan who sided with Sutoku, Tameyoshi and Tametomo; and the monks Genbō, Shinzei (真済, 800-860; obscure today, but apparently well known as a monk turned tengu in the middle ages) and Raigō (who supposedly turned into the infamous “iron rat”).

In Hirasan Kojin Reitaku (比良山古人霊託; “The Spiritual Oracle of the Old Man of Mount Hira”) this is only a temporary fate, though: supposed by the time this work was compiled, he already managed to leave Tengudō. As I discussed last month, this reflects a fairly standard belief too: to become a tengu, one had to actually be a Buddhist, and while it made striving for enlightenment more difficult, it did not mean eternal damnation or anything of that sort. A tengu could still choose to pursue rebirth in a pure land - it was just more difficult than for a human.

The evolution of Ryōgen’s image didn’t end with the establishment of his new role as a king of tengu, or even with the arguments that he might have nonetheless subsequently attained enlightenment. By the end of the Kamakura period, he came to be worshiped explicitly in the form of a “demon king”. While initially polemical, this image of him came to be subverted by Tendai monks to their own ends. They asserted that Ryōgen did not enter the realm of ma because of his arrogance, but rather consciously chose to do so in order to protect Buddhist principles. By becoming the ruler of its inhabitants, he also became their ultimate conqueror.

The notion of a being who is simultaneously essentially Mara-like and a protector of Buddhism seems contradictory. That’s actually the intent here. Through the middle ages, the esoteric schools of Buddhism developed the notion of hongaku, or “original enlightenment”. In its light, opposites were in fact identical. Buddha was the same as Mara (魔仏一如, mabutsu ichinyo). As it was argued, to attain Buddha nature one had to understand and experience delusion as well. Thus virtuous individuals could become demon kings in order to freely control evil beings.

In addition to its deep philosophical implications, the hongaku theory was also used to reject criticisms of the Buddhist establishment. Enjoying luxuries was but a way to better understand delusion, and thus to advance along the path to enlightenment. Its proponents embraced some criticisms of Ryōgen: he did favor nobles, accumulate wealth and live arrogantly. He did become a powerful tengu. But all of this was in fact part of a noble goal. And on top of that, as a demon king he was an even more fearsome protector of Tendai than he would be otherwise.

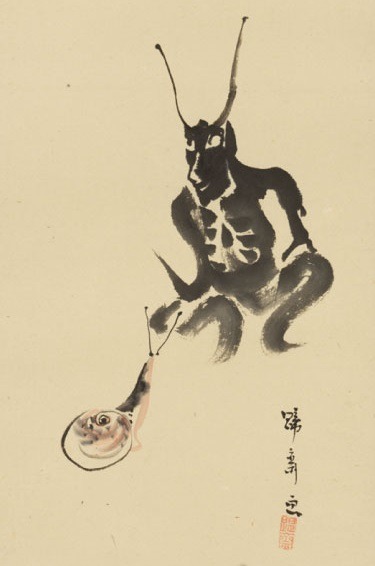

"Tsuno Daishi and a snail" by Teisai Hokuba (Sumida Hokusai Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The new role of Ryōgen warranted new iconography. While formerly portrayed simply as a monk holding the expected priestly attributes, in the Kamakura period he came to be depicted as Tsuno Daishi (角大師), the “Horned Master”. This image spread far and wide due to the development of a belief that hanging depictions of Ryōgen would guarantee the same protection Tendai institutions received from him. He came to be seen as particularly efficient in warding off disease.

Many temples still distribute talismans depicting Tsuno Daishi today. This custom received a lot of press coverage in the early months of the COVID pandemic, and you might have seen some examples on social media.

From vengeful spirit to tengu: the case of emperor Sutoku

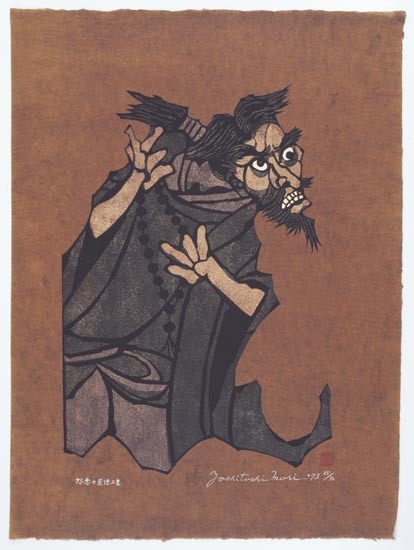

Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Mori (Tokyo's National Museum of Modern Art; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Sutoku has much in common with Ryōgen - he was also a historical figure who purportedly became a tengu. However, he was not a monk, but rather an emperor. He reigned from 1123 to 1142, when he was forced to abdicate in favor of his half brother Konoe.

Konoe passed away in 1155, but Sutoku was not allowed to return to the throne. It was instead claimed by another half brother, Go-Shirakawa. Sutoku decided that’s enough half brothers seizing a position he believed was still rightfully his, and plotted an uprising. This culminated in the Hōgen Disturbance of 1156. Alas, planning seemingly wasn’t his strong suit, since the conflict was essentially resolved before it even started. Go-Shirakawa’s forces defeated Sutoku’s before they even left their encampment.

Sutoku as a vengeful spirit, as depicted by Kuniyoshi Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

In the aftermath of his failed rebellion, Sutoku was exiled to Sanuki, where he eventually passed away in 1164. However, his memory lingered on. He most likely came to be widely perceived as a vengeful spirit after the great fire of Angen broke out in Kyoto in 1177. Other subsequent disasters, including the Genpei war (1180-1185) and the 1181 famine, strengthened the belief that he was punishing his enemies from behind the grave. However, he didn’t become just any vengeful ghost, but one of the three greatest members of this category ever, next to Sugawara no Michizane and Taira no Masakado.

Sutoku was, in a way, the sum of many of the greatest fears of medieval Japan. The belief in his rebirth as a vengeful ghost coexisted with a tradition presenting him as a tengu - arguably one of the greatest tengu ever. This status is firmly ingrained into his image in later sources. Today he is frequently included in modern groupings of “three great youkai” alongside Shuten Dōji and Tamamo no Mae. It seems sometimes he’s replaced by Ōtakemaru, but honestly I think he is more worthy of this spot, and also even though this is ultimately a synthetic modern group, it’s much more representative of medieval culture to have a tengu alongside an oni and a fox.

A strikingly tengu-like vengeful Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

While peculiar, Sutoku’s dual role as a tengu and a vengeful spirit is not entirely unique. Initially these two categories were pretty firmly separate. Tengu obstructed attaining enlightenment and rebirth in a pure land; vengeful ghosts, as their name indicates, were focused on personal vengeance. However, in popular imagination they overlapped, as evident for example in members of both groups scheming together in the Taiheiki. This most likely reflects the overlap between the perception of enemies of Buddhism and enemies of the state. Vengeful ghosts were typically members of factions who lost one political struggle or another, and their vengeance was aimed at the establishment.

Regardless of Sutoku’s supernatural taxonomic position, his post-mortem fate is tied to the fact he was a devout Buddhist. All accounts of his exile stress that he spent much of his time copying sutras. According to a rumor first attested in 1183, he also wrote a curse on their backs using his own blood, vowing to become a “demon king” - (a) Mara - due to perceived injustice he faced. There is no evidence it’s based on a historical event, even though it’s not impossible Go-Shirakawa did believe in it. At the very least, he definitely saw the deceased Sutoku as a supernatural threat, as he had various ceremonies performed in hopes of pacifying him.

Hōgen Monogatari, composed in the early fourteenth century, asserts that he became a tengu while he was still alive. When his request to deposit the completed manuscripts in a temple in Kyoto was denied by Go-Shirakawa, he vowed to remain his enemy in future lives, and stopped cutting his nails and hair. This symbolically marked his transformation. However, a former emperor couldn’t just become any tengu. Therefore, for instance in the Taiheiki he is described as a leader of the tengu, and his bird form is that of a golden kite.

Up to 2022, the Touhou wiki used to claim that “among Touhou fans, it is almost a general idea that the Tenma is inspired by Grand Emperor Sutoku” (not sure what is the “grand” doing here, there’s no such a title as daitennō as far as I am aware, but I digress), as you can see here. I will admit I’ve never encountered this headcanon - you will generally be hard pressed to find Touhou headcanons relying on actual mythology that aren’t just some variety of power level wank or otherwise all around awkward - so I think removing it was the right move (I don’t think the replacement is any better considering Mara is not a “Hindi god” - Hindi is a language, not a religion - but that’s another problem).

I’m also not aware of any Sutoku fan characters save for Tenmu Sutokuin from the fangame Mystical Power Plant who isn’t even supposed to be a take on the canon Tenma. Design-wise she clearly leans more into the vengeful spirit side of things (to the point the design would work better as Michizane than Sutoku, really, though I don’t dislike it). The filename on the wiki misspells her name as Tenma, but I have no clue whether this has anything to do with the strange headcanon assertion from the Tenma article. The closest thing to a Tenma reference she gets is a spell card referencing the sixth heaven, but the game refers to her merely as a “great tengu”.

Kōgyo Tsukioka's illustration of a performance of Matsuyama Tengu, with actors playing Saigyō, Sutoku and another tengu (wikimedia commons)

MPP aside, there's a lot of room for Sutoku in Touhou. The poet-monk Saigyō, whose life and works served as a loose inspiration for the plot of Perfect Cherry Blossom and Yuyuko’s character, went on a journey through locations associated with the late ex-emperor four years after his death, in 1168. He felt a personal connection to him because before being ordained he served as a guard of the imperial palace during his reign. This unconventional pilgrimage to at the time peripheral, sparsely inhabited areas was both a form of paying respect to his former superior, and possibly a way to pacify his vengeful spirit.

Saigyō obviously did not meet the deceased Sutoku, and ultimately only two of his poems deal with his downfall. However, later legends kept expanding upon their connection. This eventually culminated in the development of a tale according to which the monk in fact encountered Sutoku in the form of either a vengeful spirit or a tengu. The noh play Matsuyama Tengu is based on it. Its title is derived from the name Sutoku’s first residence after his exile. As a curiosity it’s worth pointing out the play singles out Sagamibō (相模坊), the tengu of Mt. Shiramine, as an ally of Sutoku - an ideal candidate for a stage 5 sidekick, if you ask me.

Some further interesting developments regarding Sutoku’s tengu identity took place in the Edo period, but I’ll discuss them in a separate section later.

The other tengu emperor: Go-Shirakawa

A portrait of Go-Shirakawa (wikimedia commons)

While Sutoku’s opposition to Go-Shirakawa essentially was the first step to the development of the belief he was a tengu, the latter also came to be viewed as a member of this category. While still alive, no less. One of the first sources to identify him as a tengu is a letter of his contemporary Minamoto no Yoritomo. He refers to the emperor as the “greatest tengu of all Japan” because of his notoriously fickle political positions. He at one point approved Minamoto no Yoshitsune’s plan to suppress Yoritomo, just to reverse this decision and declare Yoshitsune is acting on behalf of a tenma.

The notion of Go-Shirakawa being a tengu is present in the Heike Monogatari as well. In the scene I already mentioned, Sumiyoshi informs Go-Shirakawa that extensively studying Buddhist texts made him arrogant, and that he’s already attracting the attention of tengu. It is just a matter of time until he will be reborn as one of them himself. Stressing his religiosity is meant to show how it is possible for him to become a tengu in the same manner as monks.

Go-Shirakawa’s tengu career arguably peaked with his portrayal in Hirasan Kojin Reitaku. It states that both him and Sutoku became tengu, but it is the former whose “power is beyond comparison”. However, he plays no bigger role in the narrative, and he’s not described as a leader of the tengu, or even as the most powerful of them. In the absence of Ryōgen, it is apparently his contemporary Yokei (余慶; 919-991) who became the most powerful tengu. Go-Shirakawa doesn’t even get to be the second most powerful - that’s apparently Zōyo (増誉; 1032–1116). As far as I am aware, no distinct legends about these monks becoming tengu exist, so much like the elevated position of Go-Shirakawa this seems like a peculiarity of Hirasan Kojin Reitaku.

Early twentienth centiury depiction of a typical shirabyōshi costume (wikimedia commons)

While Go-Shirakawa doesn’t appear in any particularly significant pieces of tengu literature otherwise, his personal quirks are responsible for a somewhat obscure aspect of tengu background. A further detail revealed in the Hirasan Kojin Reitaku is that tengu are connoisseurs of all sorts of performances, but enjoy the dances of shirabyōshi in particular. know, I brought this up already in the previous article, but I think it’s a fun detail. Think of the sheer potential of a tengu shirabyōshi character (whether in Touhou context or elsewhere), also.

From celebrated saint to reviled tengu and back again: Ippen

A statue of Ippen from Hōgon-ji, apparently destroyed in a fire in 2013 (wikimedia commons)

Ippen is here more as a curiosity than anything, since he isn’t really a mainstay of tengu literature. Like Ryōgen and the two emperors-turned-tengu, he was a historical figure. He lived from 1238 to 1289 and founded the Jishū school of Pure Land Buddhism. He spent much of his life as a wandering preacher, advocating a unique form of nenbutsu (chanting the name of Amida), the self-explanatory nenbutsu dance (念仏踊り, nenbutsu-odori).

Legends assert that various miracles occurred thanks to Ippen’s devotion. For instance, at one point the nenbutsu dance he initiated made flowers fall from the sky. On another occasion, purple clouds appeared above him. Stories of his various miraculous deeds were retold in the form of picture scrolls, such as Ippen Hijiri-e (一遍 聖 絵; “The Illustrated Biography of Ippen”).

Ippen’s activity, in particular the dance he promoted, was evidently controversial among his contemporaries. Tengu Zōshi refers to him as the “chief tengu”, and portrays the practices he spread negatively. An entire explanatory paragraph is devoted to stressing the disruptive character of nenbutsu he promoted. Alongside other unorthodox behaviors it is blamed for various social ills including the fall of the Song dynasty in China (sic).

The opposition of other Buddhist schools to certain early currents within the Pure Land movement was often rooted in the rejection of the worship of deities and even Buddhas other than Amida. Of course, today it’s not hard to find people incorrectly convinced Buddhism is a “religion without gods” (this is a phenomenon so widespread it was actually considered a major obstacle by researchers of the history of Buddhism). However, through the middle ages devas, kami, Onmyōdō calendar deities and various figures like Dakiniten or Matarajin who defy classification altogether were anything but marginal in most schools of Buddhism in Japan. Oaths were sworn by Taishakuten and his entourage, Enmaten and Taizan Fukun were invoked in popular rites meant to guarantee good fortune, and so on.

Interestingly, Tengu Zōshi does not deny that miracles attributed to Ippen really happened. In fact, they are even depicted in the illustrations. However, the reader is expected to realize they are implicitly not a genuine display of Buddhist holiness, but merely a tengu trick meant to lead people astray. This is essentially a twist on stories already common in the Heian period, something like the tengu pretending to be a Buddha in a famous story from the Konjaku Monogatari adapted to reflect the anxieties of the Kamakura period tied to new religious movements.

The condemnation of Ippen goes further than merely implying his miracles were trickery, though. While in the final section of the scroll it is revealed that with enough effort even a tengu can attain buddhahood, Ippen is singled out as incapable of that. He is destined to fall even further from grace and to be reborn in the realm of beasts.

Despite the circulation of such negative opinions about Ippen among his contemporaries, Jishū school ultimately survived past the Kamakura period, and it still exists today.

Tengu caught between history and fiction: Tarōbō

Tarōbō in a mandala from Mt. Atago (via Patricia Yamada's Bodhisattva as Warrior God; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Tarōbō (太郎坊) is the tengu of Mount Atago. This location’s association with the tengu is well attested, and for instance in Hirasan Kojin Reitaku multiple of them are said to reside there, including Yokei, Zōyo and Jien.

However, Tarōbō is not identical with any of these historical monks. He’s an interesting case because it would appear he stands exactly on the border between historical figures and literary characters. One of the first attestations of him, if not the first one outright, has been identified in the Tengu Zōshi. On an illustration showing a gathering of tengu leaders, who are mostly identified by the names of schools of Buddhism they represent, one is instead given a specific name, Atago Tarōbō (愛石護太郎房). His notoriety continued to grow in later sources: Taiheiki presents him as a well known tengu, while Heike Monogatari outright labels him the “greatest tengu in all of Japan”.

While Tengu Zōshi and other early sources don’t provide any information about Tarōbō’s origin, in later tradition he came to be identified with the legendary Korean monk Nichira (日羅). His name would be read as Illa following the Hanja sign values, and at least some authors prefer using this reading or list both. I’m sticking to Nichira here, to maintain consistency with a name sometimes used to refer to his tengu form, Nichirabō (日羅坊; “the monk Nichira”).

A statue of Nichira (amagasaki-daikakuji.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Nichira is mentioned for the first time in the Nihon Shoki, in the section dedicated to the reign of emperor Bidatsu (late sixth century). He is described as an inhabitant of Baekje, one of the three Korean kingdoms which existed at the time. However, his father came there from Japan. The emperor seeks his help with navigating foreign policy. After some tribulations - apparently the king of Baekje didn’t want to let him go - he finally arrived in Japan in 583, armed and on horseback. He starts acting as an advisor to the emperor.

After a few months, Nichira is assassinated by other Baekje envoys present in the court since he wants the emperor to pursue rather aggressive foreign policy (most notably, he suggests ruthlessly slaughtering any potential settlers from Baekje who would try to establish settlements in Japan). The assassination has to be delayed, because he emits supernatural light at night. That’s not where his apparent supernatural powers end - after being killed he resurrects for a moment in order to make it clear his assassination was not a plot of Silla (another Korean kingdom). He is later buried, and no further mention is made of him.

While some elements of the Nihon Shoki account were retained in later legends about Nichira, especially his arrival from Korea and his ability to emit a supernatural glow, he was otherwise essentially entirely reinvented. Instead of an advisor of emperor Bidatsu, he came to be portrayed as a Buddhist monk and as an ally of prince Shotoku.

An early example of such a legend is preserved in Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki (日本往生極楽記; “Japanese records of rebirth in a Pure Land”) from the late tenth century. It states that Nichira met with Shotoku when the latter was still a child, and declared he was a manifestation of Kannon. The prince in response recognized him as the reincarnation of one of his disciples from an unspecified past life. We also learn that he is capable of emitting light because of his devotion to Surya, the personification of the sun. There’s no real chronological issue here: while Nihon Shoki doesn’t mention Shotoku (or Buddhism, for that matter; it first comes up a year after Nichira’s death there) in any passages dealing with Nichira, the prince would indeed be a kid at the time of his arrival.

Things get more complicated later on. True to his portrayal as a ruthless enthusiast of military operations, Nichira came to be described as aiding Shotoku in quelling Mononobe no Moriya and his allies. Following the conventional chronology this would have happened long after Nichira’s death, though. A possible attempt at reconciling obviously contradictory traditions can be found in Ōe no Masafusa’s Honchō Shinsenden (本朝神仙伝), as you might remember from the Ten Desires post from last year.

In contrast with virtually every other source dealing with Shotoku’s genealogy, Masafusa claims the prince was a son of Bidatsu, which would make him considerably older at the time of Nichira’s arrival. The meeting between them is fairly similar to the Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki version: Nichira recognizes Shotoku as a manifestation of Kannon, and both of them then emit supernatural light. No mention is made of any military help, though.

The portrayal of Nichira as a military ally of Shotoku is present in legends which link him with tengu. After the defeat of Moriya, he supposedly left to take over Mt. Atago. According to a guide to famous places (名所記, meishoki) from 1686, Kyōwarabe (京童; “Children in Kyoto”) by Kiun Nakagawa (中川喜雲; 1636-1705) he did so in the form of a tengu.

Atago Gongen (wikimedia commons)

Bernard Faure notes there is a similar legend in which Nichira is a separate figure from Tarōbō. The former, portrayed as a military official in the service of prince Shotoku, sets on a journey to pacify the tengu of Mt. Atago. He accomplishes this by revealing he is a manifestation of Shōgun Jizō (勝軍地蔵), a Kamakura period reinterpretation of this normally peaceful bodhisattva as a fearsome warrior, historically worshiped on Mt. Atago as Atago Gongen. Nichira then becomes the leader of the tengu, while Tarōbō provides him with information about the mountain.

Something that surprised me is that there is a single Korean source which mentions the tradition presenting Nichira as a monk who became a tengu. During the Imjin war, a failed Japanese invasion of Korea, the Korean Neo-Confucian philosopher Kang Hang was captured and subsequently spent three years (from 1597 to 1600) in Japan as a prisoner of war before escaping (possibly with the help of Seika Fujiwara, a fellow Neo-Confucian scholar he befriended). He wrote a memoir dealing with this experience, Kanyangnok (“The record of a shepherd”) in which he mentions Nichira in passing. He states that he was known as Tarōbō, and that he was enshrined and worshiped as Atago Gongen.

Something that’s worth pointing out is that despite living centuries apart, Ōe no Masafusa and Kang Hang both make the same mistake, stating that Illa arrived in Japan from Silla, as opposed to Baekje. I thought this might represent an alternative tradition, but in both cases translators pretty firmly conclude we’re dealing with a mistake. My best bet would be that this has something to do with the Japanese name of Silla, 新羅, sharing a kanji with Nichira’s own name; the name of Baekje, 百済, does not. It doesn’t seem any later legend brings up his post-mortem effort to clear the name of Silla envoys from the Nihon Shoki, so I don’t think that was necessarily a factor.

I’m actually shocked I haven’t seen a Touhou take on Nichira, considering his association with Shotoku. In particular, it’s worth pointing out that his transformation into a tengu is essentially how people tend to mistakenly assume the connection between Matarajin and Hata no Kawakatsu works (in reality, it’s very limited in scope and indirect, but that’s a topic for another time). Plus there’s a lot of storytelling potential in having a tengu - or even Tenma - be yet another character from Miko’s past. ZUN isn’t very interested in building upon prince Shotoku legends involving Kawakatsu or Kurokoma, but it’s hard to deny they’re a popular topic in fanart.

Yet another tradition about the identity of Tarobō, as far as I can tell entirely independent from his connection to Nichira, is preserved in the Engyōbon, the oldest version of Heike Monogatari. A gloss states that he is the tengu form of the monk Shinzei (真済; 800-860), who in a tale from Konjaku Monogatari and a variety of other sources menaced empress Somedono (染殿后; Fujiwara no Akirakeiko), the wife of emperor Seiwa.

Tarōbō also plays a role in a tale unrelated to speculation about his origin, Kuruma-zō Sōshi (車僧草紙; “Tale of the handcart priest”). It was originally composed in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. The eponymous protagonist is a Zen practitioner who, as his name indicates, travels with his handcart in tow. Tarōbō attempts to convince him to abandon this lifestyle. They engage in a Zen dialogue (mondō), in which the monk triumphs over the tengu. He also manages to overcome Tarōbō’s subordinates who attempt to make him stray away from his practice by showing him gruesome images of battles in the realm of the asuras.

Finally, under the name Nichirabō Tarōbō appears in the tale of Zegaibō. Initially I planned to only dedicate a single paragraph to it, but I figured Zegaibō is such a fun figure that a separate section is warranted.

Not a tiangou: Zegaibō, the Chinese tengu

Zegaibō taking a bath (wikimedia commons)

The history of Zegaibō (是害坊) starts before he even got this name. In the anthology Konjaku Monogatari, there are a handful of stories about tengu arriving in Japan from overseas - specifically from India or China. These are obviously literary fiction, as there is nothing quite analogous to tengu in Indian literature, and while their name is borrowed from Chinese tiangou, this term also doesn’t have all that much to do with tengu, ultimately.

One of the aforementioned stories focuses on a Chinese tengu named Chira Yōju (智羅永寿; I was unable to establish whether there’s any connection with 智羅天狐, the alternate name of Iizuna Gongen, Chira Tenko) He arrives in Japan to challenge local Buddhist monks. He reveals that he has previously bested these in his homeland successfully, and that he would like to check how their Japanese peers compare. Local tengu take him to Mt. Hiei, where he unsuccessfully tries to bait major Tendai monks, including Ryōgen, into battling him. He is eventually beaten up by Ryōgen’s attendants, and after his defeat the Japanese tengu take him to a hot spring so that he can recover. In the end he decides to return home.

It was possible to establish that Chira Yōju was the basis for the tale of Zegaibō because the colophon of an illustrated scroll known simply as Zegaibō Emaki (是害坊絵巻) states that the story draws inspiration from a similar tale from the lost collection Uji Dainagon Monogatari. Based on other sources it is assumed it was most likely identical with the Konjaku Monogatari account of the misadventures of Chira Yōju. Save for the change of the main character’s name, the stories do not differ much. More time is dedicated to the meeting between Zegaibō and the Japanese tengu, though. They are led by Nichirabō from Mt. Atago.

Zegaibō meeting with his Japanese peers (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Zegaibō evidently became a popular, recognizable character later on. This might reflect a sense of patriotism (or nationalism) the story possibly could have inspired in the readers: the Japanese monks are portrayed as more resistant to the schemes of demons than their continental peers, after all. However, it’s also possible that Zegaibō’s defeat was interpreted as a take on tensions between Buddhist monks and shugenja, considering the latter were commonly compared with tengu.

Regardless of which interpretation is correct, Zegaibō’s undeniable popularity allowed him to reappear in a variety of other tales. There is a noh play which simply adapts the tale about him, Zegai. The events are largely the same, though the name Tarōbō is used instead of Nichirabō to refer to the tengu of Mt. Atago. Bernard Faure mentions that in one version of the legend about Nichira’s arrival on Mt. Atago, he defeats Zegaibō, here portrayed as the leader of the local tengu. The tengu subsequently reveals the “sacred geography” of Japan to him. Finally, Zegaibō plays a major role in the Edo period puppet play Shuten Dōji Wakazakari (酒呑童子若壮; “Shuten Dōji in the Prime of Youth”).

In this work, Zegaibō is indirectly responsible for the transformation of the eponymous character into an oni. After a rampage which left 160 monks dead and various other heinous acts, the young Shuten Dōji, known simply as Akudōmaru (悪童丸; “evil child”), proclaims that there has never been anyone more mighty than him in Japan, China or India. This display of arrogance alerts Zegaibō, who appears in the guise of a young monk and offers to wrestle with him so that he can prove his strength. However, as soon as the fight starts, he reveals his true form and takes Shuten Dōji into the air.

Zegaibō presents Akudōmaru to Maheśvara (via Keller Kimbrough's Battling Tengu, Battling Conceit; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Zegaibō then brings his opponent to Maheśvara (摩醯首羅王, Makeishuraō; a phonetic transcription is used in place of the most common Japanese form 大自在天, Daijizaiten). The latter is unexpectedly described as a maō. Zegaibō seemingly presumes that his boss will punish the unruly human by turning him into a tengu, but Maheśvara is so impressed by his bravery that he chooses to turn him into an oni to let him cause even more chaos. This is rather obviously distinct from the more widespread versions I discussed in the not so distant past.

From makara to tengu: Konpira

A typical depiction of Konpira as one of the heavenly generals (via Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While Zegaibō according to tales focused on him arrived from China, there is technically a tengu whose origins were believed to lie even further away - Konpira (金比羅). However, he is a special case because despite being arguably one of the most famous tengu, he actually wasn’t viewed as a member of this category for most of his history.

Konpira is a Japanese transliteration of Sanskrit Kumbhīra. This name can be literally translated as “crocodile”. His origin is poorly understood, though it is possible he was originally essentially a divine representation of reptilian inhabitants of the Ganges. As you can read here, the gharial, the mugger crocodile and the saltwater crocodile all can be found in this river in some capacity.

Fittingly, Kumbhīra is sometimes described as a makara who converted to Buddhism. This term refers to a type of partially crocodilian mythical hybrid, most notably depicted as the steed of Hindu deities such as Ganga and Varuna. Bernard Faure suggests that in Japan he might have been analogously understood as a wani at first. However, Kumbhīra could also be portrayed as a yaksha, for example in the Golden Light Sutra. What remained consistent is the idea that he was a fierce being converted to Buddhism.

Kumbhīra is well known as the foremost of the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō). It is possible that the crocodilian Kumbhīra and the homonymous heavenly general were initially separate deities, though in Japanese context they are effectively the same. Konpira and his peers are regarded as the protectors of the Buddha Yakushi but historically were simultaneously perceived as a type of shikigami. I will only discuss this role more in my next article, though, as it is not very relevant here. All you need to know is that it made him a commonly invoked protective deity in apotropaic rituals.

An interesting legend pertaining to this aspect of Konpira’s character is preserved in the Taiheiki. When Fujiwara no Yasutada (藤原保忠; 890-936) fell ill, a Buddhist priest arrived to perform a ritual focused on Yakushi and his heavenly generals to heal him. However, as soon as he started to invoke Konpira, Yasutada got so horrified that he died. The ritual has apparently been hijacked through supernatural means, and what he heard was not the name “Konpira” but rather the phrase kubi kiran - “I’ll cut off your head”. This was an act of vengeance of the spirit of Sugawara no Michizane - Yasutada was one of the courtiers who conspired to exile him earlier. Evidently after he became a vengeful spirit he was able to essentially turn Konpira to his cause and reverse the effects of invoking him.

While the heavenly generals are associated with the Chinese zodiac, the correspondences between the individual deities and zodiacal animals aren’t really consistent. Konpira can variously be linked with the tiger, the rat or the boar, and accordingly with the northeast, north or northwest. The northeastern link is particularly significant, as in some cases it led to conflation between him and Matarajin, who as a subduer of demons was strongly associated with this direction.

A variant of the legend in which Saichō, the founder of Tendai, meets Matarajin during his journey to China identifies the latter with Konpira. Supposedly Konpira slash Matarajin was originally the protector of the Vulture Peak in India, then moved to Mount Tiantai in China, and finally reached Mount Hiei in Japan with Saichō.

The two were also equated with each other by the Tendai priest Jōin (乗因; 1682–1739) in the Edo period. However, his attempt was actually met with criticism from his contemporaries. A certain Sōji Mitsuan (密庵僧慈) wrote in 1806 that Jōin was evidently confused because Matarajin and Konpira are clearly separate deities. He concludes he evidently didn’t even read the Mahāvairocana Sutra. I’m honestly surprised ZUN didn’t reference this conflict over syncretism in any of Okina’s spell cards, it would fit right in.

Konpira Daigongen (wikimedia commons)

Despite Matarajin’s tengu credentials, which I discussed last month, the association between him and Konpira actually isn’t why the latter came to be seen as a tengu. This phenomenon instead began as an aspect of his role as the protective deity of Matsuo-ji on Mt. Zōzu (象頭山) in Shikoku. Here he came to be worshiped under the name Konpira Daigongen (金毘羅大権現). His enshrinement apparently only occurred in 1573, though according to a legend from the seventeenth century he arrived there much earlier, and already resided on Mt. Zōzu in the times of En no Gyōja. However, there is no reference to him in the few earlier sources dealing with this location. Since its name can be translated as “Mt. Elephant Head”, it has been suggested that it might have been associated with Shōten, the Japanese form of Ganesha, in earlier periods, though this remains speculative.

Despite Konpira’s new role as a mountain god, his early aquatic connections were not entirely lost. In the eighteenth century he came to be seen as a protector of maritime routes through the Seto Inland Sea and tutelary god of navigation. This reflected the growth of importance of inland maritime trade which was a result of the shogunate's ban on most foreign trade.

Interestingly, while most donations were made to Konpira by local sailors and merchants, his new role made him so famous that Chinese traders residing in Nagasaki prayed to him too, and a small shrine was even erected in that city at one point. Donations made by travelers from the Ryukyu Kingdom are recorded too. Both of these phenomena were highlighted in Edo travel books in order to stress the prestige of Konpira.

Kongōbō (Universität Wien's Religion in Japan: Ein digitales Handbuch)

Konpira didn’t become a tengu right away. The oldest recorded tradition associating Mt. Zōzu with a specific tengu refers to him as Kongōbō (金剛坊; “diamond priest”). He was not (yet) a form of Konpira, but rather a deified seventeenth century Shingon monk, Yūsei (宥盛), who between 1600 and 1613 served as the abbot of Matsuo-ji.

It seems Yūsei actually created the image of himself as a tengu on his own - in 1606 he commissioned a statue depicting him as a tengu manifestation of Fudo Myōō. The inscription explicitly states that he “entered the way of tengu” in order to bring fame to the mountain. This was a part of a bigger project of portraying himself as a master of various esoteric arts in order to gain the patronage of local nobles. After he passed away, his disciples and relatives continued spreading the image of his tengu form, now renamed Kongōbō. He eventually came to be seen as a manifestation of Konpira.

In popular imagination the new tengu-like image of Konpira eventually came to be detached from its actual origin. He was instead identified as emperor Sutoku simply because both were associated with roughly the same area - the historical Sanuki province. This idea was popularized by the 1756 play Konpira Gohonji Sutokuin Sanuki Denki (“The Sanuki Legend of the Retired Emperor Sutoku, the Original Source of Konpira”) by Izumo Takeda II. Various other authors followed in his footsteps, including Akinari Ueda and Bakin Takazawa, strengthening this equation.

While I focused on the early portrayal of Konpira and on his eventual transformations into a tengu, the traditions of Mt. Zōzu continued to evolve in subsequent centuries. After the separation of Buddhism and Shinto, Konpira came to be viewed as a kami. Due to the influence of Atsutane Hirata and his disciples he received a new name, Kotohira (金刀比羅) after the Meiji reforms. However, many lay people continued to refer to the protector of the mountain as Konpira. Today both forms of the name are in use.

Bibliography

Tumblr doesn't let me post the bibliography as a part of the article for some reason. You can find it here in the form of a google doc.

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have two questions.

1. What is the Youkai Expansion Project?

2. What does Reimu think about it?

in perfect memento in strict sense, our favourite unreliable narrator hieda no akyuu talks about the formation of gensokyo in yukari's article. it's worth noting that it's actually pretty obvious when akyuu is lying, because akyuu lies either as speculation (which she does other times, in obvious ways, in yukari's article) or to keep villagers from knowing how gensokyo works - whereas the explanation provided for the formation of gensokyo in pmiss aligns pretty accurately to others we've seen before and since, and explicitly states that gensokyo was created for youkai. in other words, knowing about the formation of gensokyo isn't something that would threaten the youkai's dominance of gensokyo - bear in mind that pmiss is part of the chronicle, which is (ostensibly) written as a reference for humans.

and the plan to create gensokyo is given a name here, and it's a really interesting one - "妖怪拡張計画", the Youkai Expansion Project. kind of an odd name for a plan to create an isolated little refuge, don't you think?

there's one other time where akyuu really talks about gensokyo and that's in the monologue. she talks about how peaceful gensokyo is, how nice it is that humans (by which she means villagers, because that same chronicle also notes that outsiders absolutely die regularly) don't have their lives threatened by youkai anymore - and then notes something a bit odd.

in the same paragraph, akyuu notes that gensokyo is too small for its youkai population, then basically goes "well, it's probably not worth worrying about, they have the zen nature" in regards to creatures who go out of their way to attack every human unfortunate enough to end up in their path. she simply just... doesn't worry about it. gensokyo will remain as it is, a humble little refuge, forever!

yakumo yukari, foremost of the sages, girl from a dying future, the youkai who invaded the moon, a woman who loves the sounds of the city and hates the tranquillity of a static world, created gensokyo as a place to gather youkai, and she called the plan to do so the Youkai Expansion Project.

the youkai expansion project is pretty simple, and i've talked about the process in specifics before, but basically the idea is that as the population of the outside declines, gensokyo is going to get bigger. the bigger it gets, the more things can't be explained by science, the more people are drawn into gensokyo, and it becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. eventually it's big enough that it takes over all of japan, and from there the entire world. it's literally just Yukari Yakumo's Plan For World Domination

SORRY. THAT WAS A BIG EXPLANATION i kinda wanted to have it all in one place, y'know?

anyway reimu is entirely in favour of it. she has to be, she's the hakurei shrine maiden. she's a core component of the entire thing. she dislikes youkai because it's her role to dislike youkai, kills villagers who become youkai because it's her role to ensure that villagers never strive for anything beyond their meagre humanity - she is all in on the gensokyo con

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

the art in perfect memento in strict sense is still so cute ❤️

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

another question about touhou lore- what would you say is like. Required Reading 4 Getting Touhou?

Oh man.

In terms of, just, understanding the basics of the setting without coming away with really really insane misconceptions: Forbidden Scrollery, Wild and Horned Hermit, the fairies manga (Strange and Bright Nature Deity through Visionary Fairies in Shrine), Perfect Memento in Strict Sense (and Memorizable Gensokyo), Symposium of Post-Mysticism.

In terms of really getting what's going on, all of the above, but add (in descending order of importance): All of ZUN's music CDs (Dolls in Pseudo Paradise through Dateless Bar Old Adam), Curiosities of Lotus Asia, Silent Sinner in Blue and Cage in Lunatic Runagate, A Beautiful Flower Blooming Violet Every Sixty Years, Scarlet Weather Rhapsody, Urban Legend in Limbo, Antinomy of Common Flowers, Phantasmagoria of Dim. Dream, Grimoire of Usami, Grimoire of Marisa, Alternative Facts in Eastern Utopia, Shoot the Bullet, Double Spoiler, Impossible Spell Card, Violet Detector (these last four you can just read the spellcard comments if you wish, no need to Play It All unless you like pain), Perfect Cherry Blossom, Imperishable Night, Hidden Star in Four Seasons, Lotus Eaters' Sobering. Also: Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things by Lafcadio Hearn. (That last one's on Project Gutenberg.)

All other games and print works can be consumed mostly at your leisure.

But basically, there is a LOT of Touhou. It hides itself well because it's not all one big work like Umineko or whatever, but there really is a lot of text to get through (and it's dense!) You're not required to read all of this to call yourself a "Touhou fan" or whatever, but if you want to have productive discussions (and some idea of what ZUN's putting down, so you can predict what'll happen next without going wildly off base) these are generally what you need.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was tempted to make a smartass comment on @sukimas 's excellent posting about Meira being the PC-98 character who'd fit best into modern Gensokyo, saying, "better than Yuuka?", but, 1) Yuuka's been a cameo even in print works since Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, 2) Kazami Yuuka is effectively a different character than the Yuuka with no family name that appeared in Lotus Land Story and Mystic Square- they have similar outfits, they share the basic personality trait of saying menacing things in a pleasant tone which is probably what "Youkai moe" means, and Kazami Yuuka had some kind of encounter with Reimu and Marisa which is presumably meant to be Lotus Land Story's plot.

But Kazami Yuuka is a resident of Gensokyo, with a plot functionality in PoFV of being one of two characters apart from Komachi and Eiki who knows about the sexagenary cycle, the other being Tewi. Her theme is even called "Gensokyo Past and Present".

PC-98 Yuuka is from a different world than Reimu or Marisa, and they have to go there to fight her. You can reconcile this quite doably and easily, but in terms of texts, PC-98 Yuuka had to be reinvented even for the early Windows games before ZUN began to consider Gensokyo as a context in itself. Fascinating to look at that creative process.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wish other people were as interested in the history of the development of touhou because it's got such great stories within it.

The fact ZUN approached writing Perfect Memento in Strict Sense with his typical "I'll just give it a shot and see what happens, lol" mindset until he met a publisher at a Cafe to discuss the book and they asked "So what do the people in your world eat, where do they get it, how is it made? What do they wear, where do they get the clothes how are those made? Where do they live, who built the homes, what are they made of? If you cannot answer these questions you cannot write this book."

The fact he took that to heart and starting with touhou 10 (the first made after PMiSS) there's clearly more thought put into the where and why of everything, characters having more distinct goals and wants and homes, more distinct mythological and folkloric origins, a place within the world that they fiil their way, an impact on that world that makes them known. They're not a prop in a game, the necessary target for you to shoot at, they're a person in a world who was doing something before this fight and will go do other things after.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just wanna say I don't know much at all about Touhou but my friend shows me your art sometimes and I think the way you draw flandre is very good she's so small and so kiddy and it's nice to not see her drawn like a murder-crazy monster keep up the great work

Ohoho! then if you're new around these parts i am absolutely DELIGHTED to inform you that the "murder crazy monster" flandre is one hundred percent a fanon fabrication! (which by the way i loathe with every fiber of my being) now i'll rant to you a little bc i never miss a chance to show Flandre's good character charms sorry its my autistic brain going supercharged, critical mass even, whenever flan is mentioned, shes been a character ive held very dear to me since i was barely 13 (almost twelve years ago!) so you have to imagine my brain sizzling like soda with mentos as i'm typing this

Y'see, this uh. portrayal dates back from when our only source of flandres character was her introduction in touhou 6: EoSD (2002). Now. she DID flex about being strong and scary and threatening etc etc but what people dont get is that it was just for show! yknow! like a kid in their ebony dementia raven way phase. You cant tell me you'd see a kid in their edgy mary sue phase who blasts nightcore evanescence from the shared family computer all day and take them seriously.

after you defeat her you find out that the child is absolutely clueless on what shes doing, knows ABSOLUTELY nothing about socialization 101 and thought scaring the hell out of you was how you make pals, but if you play the reimu route she offers to give you a cake to thank you for playing with her (which has blood as an ingredient so reimu refuses but flan doesnt KNOW that humans dont drink their own blood. also she doesnt hunt her own food like remi does so thats actually sakuya's cooking)

so she DOES try to be your friend. basically the kids confused to an absurd degree but shes absolutely got the spirit

My second point: there are little character sheets written from the PoV of Akyuu which serve as official references (called Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, 2007! I always recommend this as a must-read for new fans!), and it was the first clue, a little nudge, a little trail of breadcrumbs leading to the fact that Maybe the rumors that remilia locked up her sister are actually just rumors.

But then it got confirmed in Cheating Detective Satori (2019-ongoing official manga written by ZUN w guest artists for each chapter) which portrays flan and not only is she super excited about showing off her collection of dolls and stuffed animals to sakuya but also she says this.

Flan is actually very introverted and CHOOSES to stay in the basement. None of that "remilia locked her up" bs, it's officially debunked!

(and the day i stop showing this panel of CDS to defend her characterization, you can assume that i am deceased)

ALSO. LITTLE RASCAL SAVED GENSOKYO T W I C E.

First, she used her destruction powers to disintegrate a METEOR that was headed for the scarlet devil mansion and would have an impact radius that would reach all the way to youkai mountain. She made it explode and went back to her basement to take a nap (and Remilia tried to take the credit for that but failed horribly)

AND THEN theres touhou 17.5 where she's the ONLY playable character that actually solves the incident. Again, her power to destroy anything made her the ONLY gensokyo resident able to face Yuuma without her eating Flan's bullet for lunch.

So yeah! her reputation is atrocious but the gal's not even closely as bad as people make her seem.

Thank you for coming to my TED talk i am here every day same hour and i will talk your hear off about Flandre Scarlet and i will defend her portrayal until my last breath.

PS: little headcanon moment yeah woo yeah but uhh in my head i always pictured her voiced by Ikue Otani, best known as the voice of pikachu, but specifically >her role as Hana from Ojamajo Doremi<

PPS: if you're new around here; despite everything, flandre is not actually my favorite touhou. no, nononono she is only second. Nah, the honor of the gold medal goes to ✨Her✨. do NOT get me started. I will talk for days without taking a breath between sentences.

#flandre scarlet#touhou#touhou project#character essay#character analysis#embodiment of scarlet devil

131 notes

·

View notes

Note

vibe check my little touhou hijacks (and 1 len'en) blorbos

Hidden Star in Four Seasons

Perfect Memento in Strict Sense

Silent Sinner in Blue

Ten Desires

Subterranean Animism

Gathering Reverie

Perfect Cherry Blossom

Evanescent Existence

Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost

❗️ Almost all of the above are valid Iterator names. (first, second, and last seem more like ancient names)

boosted to the top of the queue because the queue is pretty long and i saw you were worried in a more recent ask

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Yuyuko’s article in perfect memento in strict sense (as seen on en touhou wiki). Don’t like this because I sometimes don’t remember what I ate on that same day either 😑😑😑

7 notes

·

View notes