#persian vocabulary

Text

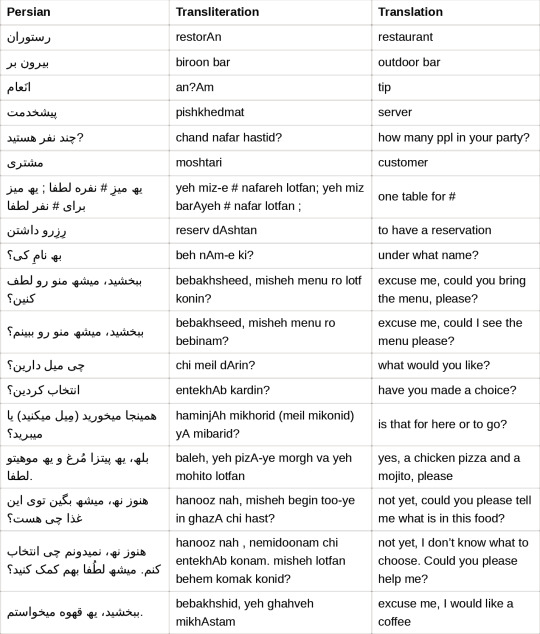

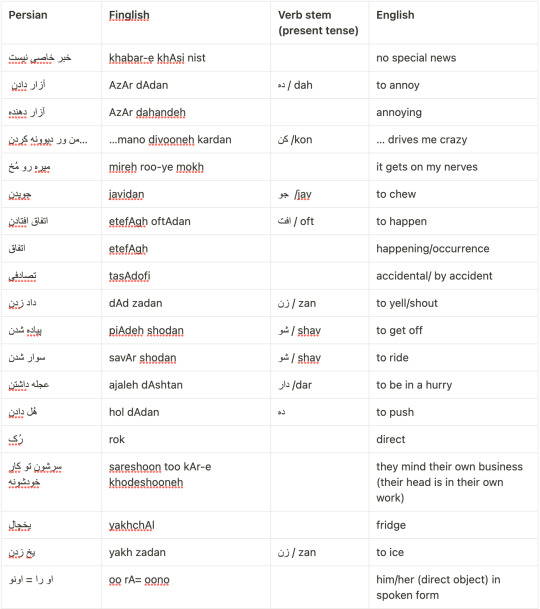

Restaurant Vocabulary

*sorry about the ه , the font did not change it

#persian#persian vocabulary#restaurant vocabulary#farsi#farsi vocabulary#persian langblr#langblr#language blr#language blog#langblog#farsi langblr#language#language learning#languages

25 notes

·

View notes

Link

Are you looking for an online Persian language school to learn Farsi efficiently? These days, you don't necessarily need to participate in face-to-face or

0 notes

Text

So uh guess who's finally properly learning Farsi (I should've learned this when I was like 4 but I was an idiot child who knew nothing of the importance of my culture-)

And has decided to memorize words by translating cookie run character names

uh-

From top to bottom, left to right:

Angel Cookie = فرشته کوکی (fereshteh cookie)

Devil Cookie = شیطان کوکی (shaytaan cookie)

Pastry Cookie = شیرینی کوکی (shirini cookie)

Pomegranate Cookie = انار کوکی (anaar cookie)

Herb Cookie = سبزی کوکی (sabzi cookie)

Olive Cookie = زیتون کوکی (zeytoon cookie)

(I also am learning how to write in Farsi so my writing is. Very bad and it only looks passable here because I traced over the words typed-out in ibis paint x :'3)

I may decide to post more of these in case anyone else may be interested in learning miscellaneous Farsi words. I don't know if anyone would be, but maybe-

(I sent these to my baba to see what he thinks and he hasn't texted back yet and I'm nervous about if I even translated or wrote these right-)

#Cookie run#angel cookie#devil cookie#pastry cookie#pomegranate cookie#herb cookie#olive cookie#language#farsi#persian language#My vocabulary is going to be so weird by the end of this#I've been translating character names into a Google document for the past two days in my free time#And somehow it's actually been working at both making me remember said words and teaching me how to read#Don't mind me cookie run community just being silly right now again (it's about 11:30 and I'm tired)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

watching a turkish drama now and its just the right touch of fucking insane

#its called duy beni btw#and first I like watching it cause I speak persian and I never realized how similar persian and Turkish are#like so much of the same vocabulary#second the plot is so crazy 😭#its a bit dramatic#honestly watching so many foreign dramas im starting to realize american media is not nearly as dramatic as these other shows#nor are they as long THESE TURKISH DRAMAS ARE 2 HOURS LONG PER EPISODE#like is it that serious do we really need this many scenes#anyways let me break down the plot cause it kinda reminds me of elite#its basically about this girl named ekim who is best friends with this girl leila#and one day while ekim and leila are walking to school leila is hit by a car#and the person that hit Leila was wearing a clown mask and then drove off into the parking lot of a nearby school#where only rich kids attend#and so people are able to conclude that whoever hit leila was someone that went to that school#but the school covers up the whole thing and then to make amends offers a scholarship to three students from the neighborhood#and ekim wanting to be the avenger attends the rich school along with her two friends bekir and ayse#and boy does this school have its problems. like crazy ass bullying#and its all about how ekim’s trying to figure out who hit leila while also trying to survive the very intense bullying culture at the school#and you know after watching so many foreign dramas and seeing how bullying seems to be a very common issue in all of them#its starting to make me see how the us is a little bit different in that regard#don’t get me wrong we have some very sick and twisted bullying happening here#but a lot of is cyber and relational bullying#so not necessarily as physical or even verbal but mostly done through rumors and gossip and exclusion#and then with the added fact of being jerks on the internet#and although relational bullying is terrible the stuff ive seen in these kdramas and turkish dramas seems... like REALLY bad?#Ive seen a lot of Koreans talk about how bullying is a really severe problem in their schools but I wonder how bad it actually is in turkey#cause I assume duy beni is not the 100% accurate portrayal of turkish schools#anyways

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The relationship of textiles to writing is especially significant, not only for the cuneiform-like qualities of many patterns (preserved in a Hungarian term irásos, meaning 'written'), but also for the parallels between ink on papyrus and pigment on bark cloth. There is, in fact, little difference between the two. Such connections are implied in many textile terms. For example, the Indian full-colour painted and printed 'kalamkari' are so named from the Persian for pen, kalam; the wax for Indonesian batiks is delivered by a copper-bowled tulis, also meaning pen. The European term for hand-colouring of details on cloth is 'pencilling'. The Islamic term tiraz, originally denoting embroideries, came to encompass all textiles within this culture that carried inscriptions. And the patterns woven into the silks of Madagascar are acknowledged as a language: the Malagasy vocabulary for writing and preparing the loom are synonymous, while the finest stripes are zanatsoratra, literally children of the writing, or vowels. The study of textiles is, in fact, a branch of palaeography, in which deciphering and dating reveals the stories encapsulated in cloth 'handwriting'.

With or without inscriptions, textiles convey all kinds of 'texts': allegiances are expressed, promises are made (as in today's bank notes, whose value is purely conceptual), memories are preserved, new ideas are proposed. Records were kept in quipu (khipu) a method of knotting string used by the Incas and other ancient Andean cultures to keep accounts and communicate information, the oldest of which is some 4,600 years old. Many anthropological and ethnographical studies of textiles aim at teaching us how to read these cloth languages anew. The 'plot' is provided by the socially meaningful elements; the 'syntax' is the construction, often only revealed by the application of archaeological and conservation analyses. Equally, the most creative textiles of today exploit a vocabulary of fibres, dyes and techniques. Textiles can be prose or poetry, instructive or the most demanding of texts. The ways in which they are used - and reused - add more layers of meaning, all significant indicators of sensitivities that can be traced back to the Stone Age."

— Mary Schoeser, World Textiles

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indoeuropean languages in Europe

Historical Roots: The Indo-European language family is believed to have originated in the Eurasian Steppe around 4000-2500 BCE. From there, groups of speakers migrated to various parts of Europe, contributing to the linguistic diversity of the continent.

by hunmapper

Language Diversification: Indo-European languages in Europe have evolved into numerous branches and sub-branches. Some of the major branches include:

Romance Languages: Descendants of Latin, including French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, and Romanian.

Germanic Languages: Including English, German, Dutch, Swedish, and others.

Slavic Languages: Such as Russian, Polish, Czech, and Bulgarian.

Celtic Languages: Including Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Welsh.

Hellenic Languages: Mainly Greek.

Baltic Languages: Such as Lithuanian and Latvian.

Indo-Iranian Languages: Including Hindi, Bengali, and Persian.

Cultural Significance: Indo-European languages have played a pivotal role in shaping European culture, history, and literature. Greek and Latin, for instance, have had a profound influence on science, philosophy, and the development of the Roman Empire.

Language Revival: Some Indo-European languages in Europe, such as Irish and Welsh, have experienced language revival efforts in recent decades. These efforts aim to preserve and revitalize languages that were declining in usage.

Language Contact: Due to centuries of contact and migration, many Indo-European languages have borrowed words and phrases from each other. This phenomenon, known as linguistic borrowing, has enriched the vocabulary and expressions of these languages.

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

LANGBLR INTRO!!!

A little about me:

Call me Azara c:

Middle Eastern - Persian origins (not ir*nian please ;-;)

26 - isfp - sagittarius

lesbian - she/her

Got my BA in English Language and Literature with a minor in French

Preparing for an MA in Teaching English as a Foreign Language and self-studying and researching theoretical+applied+interdisciplinary linguistics

Languages I speak:

Arabic (native - standard and a dialect of the gulf)

Farsi (native but I don't speak the standard)

English C1

French (standard) B1/B2

Korean B1/B2

Languages Goals - short and long term:

IELTS BAND 9

Arabic (build my vocabulary for translation)

Advancing in Korean C1

Advancing in French C1

Learning Standard Farsi

Consistently learn Japanese for 60 days

Consistently learn Chinese for 60 days

Could post about other languages that interest me at one point!

How I learn languages

tv shows mostly as I rely a lot on pronunciation and sentence structures in speech

music - I mostly listen to English, Persian, Korean, Japanese and French songs but I am open to anything as long as it's good

used to take classes before covid and then I enrolled in online classes and hated them - they were bland.

textbooks that I spent a fortune on ;-;

Let's be friends !! ♡

#langblr intro#language learning#language#langblr#french langblr#japanese langblr#korean langblr#farsi langblr#arabic langblr#chinese langblr#mandarin langblr#academia#languages

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Note: this is all totally non-rigorous free association)

Famously, the King James Version of the Bible translates Exodus 22:18 as "thou shalt not suffer a witch to live." This is one of those translations, though, that has suffered for passing through multiple different cultural lenses over the textual history of Exodus. Alternate modern translations say things like "put to death any woman who does evil magic," "*wizards* thou shalt not suffer to live," or even "whoever has sexual relations with an animal must be put to death."

In the Septuagint, the underlying word is translated φάρμακος; despite the connotation of the English word, a masculine noun; the word is associated with magical arts in general, but is *especially* associated with poison. It's from φάρμακον, a word which can mean either "poison" or "drug," and is the origin of "pharmacy." Greek had a rich vocabulary for the supernatural: an older and more general word seems to be γοητεία, "charm, jugglery, sorcery," from γόης, "sorcerer, wizard, juggler, cheat." That it includes in its semantic field the concept of sleight-of-hand shows that mundane deception is countenanced as a possible explanation for claims of magical power, which no doubt contributes to the dim social reception of magic, but also shows a neat symmetry with the modern concept of the stage magician, whom we publicly acknowledge as really being just a particular kind of illusionist and entertainer. Another Greek word for magic is, well, μάγος, the source of the English word, ultimately a borrowing from Old Persian maguš. A maguš was simply a priest of Mazda in the old Zoroastrian religion; the word is of uncertain etymology, but its connotations in Greek arise from crediting a Greek mythical version of Zoroaster with the invention of magic and astrology, showing us that perhaps orientalism of one sort or another has long been part of European traditions of the occult. There is also θαυματουργία, "wonder-working, doing miracles, wizardry."

But the Septuagint word choice is an odd one; as I understand it, the actual underlying lexical item is מְכַשֵּׁפָה/mekhashefah, the feminine form of מְכַשֵּׁף/mekhashef. The root of this word seems to be כשף/KH-SH-F, which has been glossed various ways. One gloss I find particularly interesting is "cut." Kenneth Kitchen links this etymology to the cutting of herbs; thus, a mekhashef is a kind of herbalist, and the context, as with pharmakos, is the fear of poisons--the feminine form might also make sense here, as it seems plausible that just as in our modern society, poisoning was a more reliable tool for killing for women than for men, for whom the possibility of physically overpowering their enemies was less likely.

But I think it's interesting to note other ways in which magic is about division and breaking. Though in modern fantasy a "warlock" is either just a generic wicked sorcerer, or a summoner of demons, the word comes from Old English wǣrloga ("promise-deceiver"), a deceiver, a breaker of oaths. A warlock is thus someone who dissolves social ties, or even betrays their baptismal vows by making an unholy vow, an un-promise, to Satan himself. The English "witch" comes from the Old English wiċċa or wiċċe (masculine and feminine forms respectively), from Proto-Germanic *wikkô, "sorcerer, necromancer," from the verb *wikkōną, "to practice sorcery." One likely derivation of *wikkōną is the Proto-Indo-European stem *weyk-, "to separate, to divide, to choose." This may be a reference to cleromancy, the casting of lots; many ancient words for magic link together fortunetelling of various kinds (the second element in words like "necromancy" and "cleromancy" is ancient Greek μᾰντείᾱ, "divination, prophecy, fortune-telling), but here again the concept of separation appears in a way that is difficult to ignore.

The Romans, like the Greeks, looked east for their wisdom, and were also obsessed with divination in particular, so their words for magic are often borrowed from Greek, or concern forms of fortune-telling in particular: haruspicina, the inspection of entrails; the genius or numen, language of spiritual presence and will (the latter not dissimilar to the mana of Polynesia); auspicium, the interpretation of omens, especially the flights of birds. Perhaps other kinds of magic invoked skepticism: Pliny argues that, except possibly in the making of potions (the Romans, no less than the Greeks and the Hebrews, knew that the right herbs could kill!), most claims of magic were simply lies--though there was little harm in apotropaic wards to set the mind at ease. Apuleius granted the existence of spirits and demons, and both Augustus and Constantine worried enough about magic to try to suppress its practice.

In Sanskrit, magic was apparently sometimes called इन्द्रजाल/indrajala, "Indra's net," a metaphor for emptiness, a word that foregrounds the idea of fraud and illusion. Similarly, the word माया/maya means "magic," but also "illusion," being in that way akin to the English notion of glamour found in fairy-stories. There is also possibly semantic overlap with German Zauber, whose meaning is "magic," but which is etymologically connected to Old English tēafor, "to paint [a picture]," and Icelandic töfrar, "enchantment." (Icelandic also has galdur, "sorcery," but also "[conjuring] trick.") Chinese offers the root 魔/mo2, which according to Wiktionary is from Sanskrit मार/mara, "death, pestilence;" in Chinese it takes on theurgic qualities: "devil, demon, magic, the unnatural, crazy," depending on the context it's found in: 魔羅, a kind of Buddhist demon; 魔術, "magic," as in an illusion imitating the supernatural; 瘋魔, "to be insane, to be fascinated by, to be enchanted by," a concept of obsessive madness shared in other cultures, including our own.

A full cross-cultural, historical comparison of words pertaining to magic is far beyond my capabilities, of course; but exploring current in the vocabulary and historical development of words around magic is interesting so far as it peels back the thick systematizing, empirical layer within our culture and helps us glimpse how these ideas functioned in the past. Nowadays, magic is often prototypically the magic of high fantasy: it is systematic, little more than a flashy kind of science, even if it is one accessed through mental discipline rather than mechanical instruments. Magic is patterned, stable, fundamentally knowable, because we are so thoroughly grounded in systems of knowledge that understand the whole world as patterned and knowable that we cannot imagine anything else. We redefine magic in ways that simplify it down to nothing: to be little more than abstract spiritual practice, moral therapeutic deism with countercultural window-dressing, or to mean nothing more than simply acting on the world. But is that really in keeping with the spirit of the thing, as it is has been imagined for most of history?

Magic is about many things. It is about division: discrimination, separation, cutting. Cutting the body of the sacrifice, to prod at its bloody insides; cutting breath from a living victim; cutting off the sacred from the unholy, and vice-versa. It is about speaking, chanting, singing, the form and the performance of words. It is about writing (itself a word which means to cut or carve into something). It is about deception: lies in pursuit of status or money, lies to avoid culpability for murder, lies about secret knowledge. It is about feeling oneself inhabiting a world filled with intentional beings, beings with a will and nature unknown and perhaps unknowable to you. Spirits of the dead, of the air, and of the wild world; the genius loci, the demon, the hungry ghost. It of a world when the night could claim real darkness, when the stars were forever an inscrutable mystery, and when the terrifying unknown could intrude into your life at a moment's notice. Even modern occultism feels like a nonsensical imitation of the past, with emphasis on benign enlightenment or spiritual growth, when ancient magic was rife with murder, curses, treachery, and simple human greed. The huckster fortune-teller, who cynically defrauds their customrs, is closer to the spirit of magic than the observant neo-pagan.

We are mostly too sure of ourselves, and too confident in our ability to understand even that which is at first horrifying and inexplicable, to really replicate the feeling of that kind of magic. A world in which that kind of magic is possible is a world in which the last few centuries of philosophy and epistemology and science are shown to be so profoundly wrong that we are left with nothing but naive superstition and fear. Or else, it is a world where all these basic forms of inquiry that we take for granted simply do not work--because if they did work, we would be back in our own comforting, familiar world, a world of rationalism and enlightenment, albeit perhaps with a few of the phenomenological incidentals changed. I wonder if it is really possibly anymore for us to tell stories in the mode of that older world. With the exception of certain kinds of horror, I don't really know of anything that comes close.

560 notes

·

View notes

Text

no matter what anybody else tells you, when you are learning a new language the first and most important skill is listening. the only time when this may not be the first thing is if you want to learn an alphabet first, but for languages that don't use alphabets or their variants (e.g. mandarin is logographic and script doesn't correspond to sounds), listening is still king. and after you learn that arabic or persian or korean alphabet, listening is still king. too many people learn a language for years, familiarise themselves with the vocabulary and grammar, and can't understand a word of what anyone is saying to them. it's useless if you can't comprehend.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will unfollow/mute/block/otherwise ignore people who use ableist or saneist terms about others and those who mock, joke about, or otherwise minimize the severity of COVID. Thousands of people like me are dying a week because of ableism driving the pandemic and I have zero fucking tolerance for it. If you're in any way complicit with the fascist Big Lie of "back to normal," I'm probably gonna block you. Wear a fucking mask the entire time you're in public and give up COVID-spreading activities because your personal pleasure does not trump the need for communal safety and fighting the eugenics and fascism that has been normalized through mandated COVID spread.

It's not lost on me how many so-called radicals and leftists are openly accepting of the eugenics of ableism as they claim to oppose the various mechanisms of genocide. If you're still using things like "crazy," "stupid," "dumb," "insane," or other ableist terms to describe other people or things, do better. Fix your heart and your vocabulary.

I've been in complete isolation for going on 5 years now due to COVID and the fall of society into completely open, unabashed, unmitigated, unashamed eugenics.

I'm an elder millenial Persian anarchist in so-called PNW who posts about how fucked it is that people still reproduce systems of harm while ostensibly fighting oppression.

I'm significantly disabled, heavily traumatized, food insecure, medically neglected, queer as hell, AuDHD.

Sometimes I post about media from this lens, mostly I feel like I'm screaming.

From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free

None of us is free til we're all free

Jin, jiyan, azadi

Wear a mask

TERFs, SWERFs, Tankies, Zionists, Radlibs can all be composted

If you want to help me survive, v/m/o is mordantivore

#free palestine#genocide#anticapitalism#anarchism#eugenics#wear a mask#covid#ableism#death to america#anarchotahdigism#death to the west#death to all states#queer cripple

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i think i'm gonna start posting vocab lists again#both from my sessions and also thematic lists#persian langblr#persian vocabulary#vocabulary list#random vocabulary#language#language learning#language learner#langblr#language blr#language tumblr#langspo#lang spo#lang blr#persianblr#foreign language#lmk if there are any typos/errors

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Are you searching for the best way to learn Farsi quickly and effectively? Have you been told that learning Farsi is difficult? Well, first of all, we should

0 notes

Text

/r/ is usually flapped or trilled.[30] In intervocalic position, it may have a single contact and be described as a flap [ɾ],[31] but it may also be a clear trill, especially in word-initial and syllable-final positions, and geminate /rː/ is always a trill in Arabic and Persian loanwords, e.g. zarā [zəɾaː] (ज़रा – ذرا 'little') versus well-trilled zarrā [zəraː] (ज़र्रा – ذرّہ 'particle'). [...]

Loanwords from Persian (including some words which Persian itself borrowed from Arabic or Turkish) introduced six consonants, /f, z, ʒ, q, x, ɣ/. Being Persian in origin, these are seen as a defining feature of Urdu, although these sounds officially exist in Hindi and modified Devanagari characters are available to represent them.[35][36] Among these, /f, z/, also found in English and Portuguese loanwords, are now considered well-established in Hindi; indeed, /f/ appears to be encroaching upon and replacing /pʰ/ even in native (non-Persian, non-English, non-Portuguese) Hindi words as well as many other Indian languages such as Bengali, Gujarati and Marathi, as happened in Greek with phi.[21] This /pʰ/ to /f/ shift also occasionally occurs in Urdu.[37] While [z] is a foreign sound, it is also natively found as an allophone of /s/ beside voiced consonants.

The other three Persian loans, /q, x, ɣ/, are still considered to fall under the domain of Urdu, and are also used by some Hindi speakers; however, other Hindi speakers may assimilate these sounds to /k, kʰ, g/ respectively.[25][35][38] The sibilant /ʃ/ is found in loanwords from all sources (Arabic, English, Portuguese, Persian, Sanskrit) and is well-established.[10] Some Hindi speakers (especially those from rural areas) pronounce the /f, z, ʃ/ sounds as /pʰ, dʒ, s/), though these same speakers, having a Sanskritic education, may hyperformally uphold /ɳ/ and [ʂ].[39][24] In contrast, for native speakers of Urdu, the maintenance of /f, z, ʃ/ is not commensurate with education and sophistication, but is characteristic of all social levels.[38] The sibilant /ʒ/ is very rare and is found in loanwords from Persian, Portuguese, and English and is considered to fall under the domain of Urdu and although it is officially present in Hindi, many speakers of Hindi assimilate it to /z/ or /dʒ/.[27][24]

Being the main sources from which Hindustani draws its higher, learned terms– English, Sanskrit, Arabic, and to a lesser extent Persian provide loanwords with a rich array of consonant clusters. The introduction of these clusters into the language contravenes a historical tendency within its native core vocabulary to eliminate clusters through processes such as cluster reduction and epenthesis.

what fascinates me about linguistics is that i have known all of this, intuitively, i know which sounds are urdu sounds, which are the upper and lower registers in hindi, i have also heard the complaints of elders about the loss of the proper /ph/ and i have never ever systematised this knowledge but continue retain it through sheer practice.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! sorry to bother and if you've answered this before. of course, you dont have to answer this. you mentioned in one post that you were still learning Darija and also your posts on scolarship are very interesting. ive been trying for a while to learn my dad's language since i didn't grew up speaking it, but have always been interested in persian literature and the evolution of the language so this has been a difficulty for me. i was wondering if you have any tips on improving the way a language is learned, since you're amazing at explaining things and making even complicated subjects clear.

Thank you and have a nice weekend!

Thanks for the compliment!

I don't think that I have anything like my own original foolproof method for learning languages; this is the first language I've self-taught for which there aren't a lot of materials, and everyone learns differently. Here's what I've been doing & what I can broadly recommend when learning a language for which there isn't an enormous amount of teaching material:

Be specific about what it is that you want to do in the language. Chop this up into small sections. So, instead of "I want to learn [language]" (an enormous, vague, impossible task—even native speakers do not know 100% of their languages), think "I want to be able to understand recipes," or "go to the market or a restaurant," or "make small talk and general conversation," or "text friends and family," or "read literature," or "read theory" (and for those last two goals you might have a waypoint goal of "read storybooks" or "read materials intended for language-learners or children").

I began by learning the Arabic script (resources for this abound, and the abjads used for Persian and Darija only add a few characters), and I always write Darija in this script (even though most people write it in the Latin script) to get practice.

I also learned the standard phonology at this point. But the phonology for Persian and Darija are different and involve fewer consonants than Arabic, since some of them have merged, so you won't need to worry about the Standard or Classic pronunciaton of some of the letters. The Wikipedia page for Persian phonology should be a good resource; the IPA symbols for various sounds are noted, and they have explanations of how the sounds are produced and playback that you can listen to. Note that there are obviously regional variations in phonology, but this is a good start. This is a script with a pretty standard orthography, so at this point you can theoretically pronounce any word you read (with diacritics).

cut for length:

I took inspiration from how I had been taught French and divided information up into "units" (first greetings and introductions; then numbers and colours; then telling time; then time including days of the week and months of the year, words for "today" and "yesterday" &c.; the weather; family; then personal pronouns "I" "you" "me" &c. and the verb "to have" to begin forming simple sentences such as "I have three sisters" or whatever—you'd also want to learn "to be" at this point, but Darija doesn't often use it—then I decided that my first priority after very basic conversation was cooking, so I learned terms for food items and cooking verbs).

If you can find online resources or textbooks that will teach you things in units of this type, all the better (I got started on speakmoroccan.com). If you can't, try following an online course or textbook for learning another common language (such as French, German, Spanish, English) but substitute out the vocabulary terms by using a dictionary (for Darija I used tajinequiparle).

You may be able to find some materials (at least greetings, introductions, numbers and the like) on YouTube—I recommend using these even if you can find these same terms elsewhere, to get practice listening to the language.

I feel that I learn best from textbooks and by understanding the syntax and grammar of sentences in depth. However, the materials I've consulted for Darija (and there aren't too many materials in existence) tend to give lists of words but no grammar, or example sentences that are translated in full with no explanation. Even materials that do go into the grammar (such as the Lonely Planet phrasebook) are targeted at tourists and do so with an ethos of "good enough" that may fudge the details to make them more similar to French (which is the language the book is in). So I write down and compile example sentences that I come across (there's an English/Darija dataset already in existence to help with this kind of thing) and compare them to each other to determine which word means what, which affix might be the marker for past tense or infinitive or the object pronoun or whatever, and write down my guesses to test as I go. This may be more difficult without an education in linguistics, but probably not impossible.

I separate my studying into two phases, which I go back and forth between: creating study materials, and learning from those materials. Creating study materials means finding words and writing them down in my little book, figuring out grammar and writing out the rules, writing down example sentences, and making flashcards to learn vocabulary terms (with one or more example sentences on each one).

Studying from those materials involves running through the flashcards and coming up with new example sentences for each term (so I see the side of the flashcard with the English "banana" and come up with a sentence in Darija that's something like "they have eight yellow bananas"). You could also have flashcards separated by category (pronouns / numbers / verbs / nouns / adjectives) and pick a flashcard at random from a few categories (the selection "I" / "sixteen" / "want" / "new" / "oranges" prompts you to construct and speak the sentence "I want sixteen new oranges" in your target language); this is basically analogue duolingo.

As you go about your day, name objects and colours you see and talk to yourself about actions you undertake; try to 'translate' as many thoughts as you can into your target language.

You can also construct dialogues or short compositions at the end of each "unit" you finish. Write a dialogue between two friends greeting each other after not having seen each other for a while. Write a composition about your family members; explain how they're related to you, what they look like, &c. Look up any vocabulary that you notice you're missing.

Once you have a decent vocabulary base, you'll be able to start reading. If you can find writing that's intended for children or language learners, that's great! There may also be fora or message boards online devoted to conversation in your target language. If you can find a dictionary from the target language to a language you understand, this becomes a lot easier—unfortunately I haven't found one for Darija (the lack of a standardised orthography would probably make one difficult to make). Persian has a history of being written that Darija doesn't, so you may have more luck on this score than I did.

I have an "index" in the back of my little book with abbreviations for each of the sources that I get vocabulary from, and I use these abbreviations to take note of where I got sentences, phrases, and vocabulary terms from (whether dictionaries, textbooks, youtube, online courses, online fora, reddit, academic / linguistic articles, &c.). This is so that I can return to these sources and verify what I've written down, just in case; and also because different vocabulary terms are used in different regions, so it's a good idea to have a way to look up who uses which terms.

If I come across anything by serendipity (whether in an academic article about some sociological aspect of Darija, or in the dictionary I've been using, since there's no complete words list that I can find so serendipity is the only way to discover some of the words that are in it), I write it down then and there regardless of how useful I think it will be to me immediately. This is because I have no way of knowing whether I'll ever come across it again! I don't need to memorise it right away, but maybe I'll want to learn it later.

I don't think this will help you, but for some minority languages or dialects there may be a colonial language other than English in which materials for that language are easier to access (for example, I tend to search for Darija resources in French, not English).

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

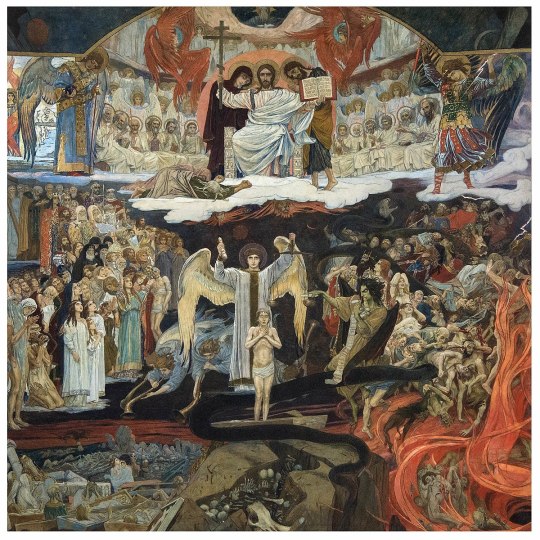

Angeology - Michael trough the eyes of artists

The second most common motif is Michael on Judgement Day, holding scales in one hand and a scroll - the book of life in the other, where souls of the damned depart at the right hand of God to the kingdom of heaven, the damned descend at his left hand to hell, where the second death awaits them after suffering doomsday. The Judgement Day was also depicted as sunset, night is born at the end of the path of the sun. Some cultures and religions believed that death reigned in the west because the sun went there to die. Michael, more precisely, is the angel of resurrection, he gives every soul the opportunity to redeem themselves from evil before death, turn their souls into gold in alchemical allegory. (some cultures uses it as an idiom - golden hands or heart of gold)

In the role of the guide of the souls, Michael follows the pre-Christian cult of the sun, the Greek Hermes, the Celtic god of sun - Lug, the Roman Mercury etc..

According to Bonaventure , Michael was a seraph and an angel who guards the gate of paradise with a flaming sword. Which council does Michael belong to? Not even theologians are sure. Author categorizes Michael to eighth angel choir.

(OP note: I attended one of Authors lectures - When I write "the reference/book/bible author chose" - it wasn't his uninformed choice. Author was and is deliberately discussing the discrepancies with theological authorities, but unfortunately they couldn't give him a direct answer either - nor commit to one notion! In order to not postpone his study, Author decided to go along one particular notion/bible/reference and followed it throughout the books. Do not be concerned about theological vocabulary, it all started by statistics, but as statistic is full of numbers only and no pictures, it is very boring. Also, as I am reading trough this tomb as we go along, I cant say now if Author devoted full chapter to the statistic alone. This is the third book, there is the first one, which, probably, explains the math thing, but oh yeah, I have to start somewhere so why not at contemporary archangel. Return to Authors words-)

Michael displaces the God of Sun so perfectly, that the caves of the sun gods have turned into places of pilgrimage.

The author also talks about many civilizations that associated the sun with the figure of the judge, as the embodiment of law and justice. Michael was often depicted as a fighter against the Evil.

(Not a wonder, that when you google Michael and Dragon, you'll get something over 680.000 hits. Some of them are actually titled Michael and the Serpent. That Michael was deemed a protector, it is confirmed in the bible, where most of the artists drew inspiration from. It is important to mention that in these times only the gentry and the church had money to patron the art, or at least was not ashamed to show the plenty of it.)

For Good Omens fanbase: Author once connects Michael with Metatron and uses Persian painting as an example. Not under my watch.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review - 100 Poets: A Little Anthology by John Carey

Thank you to Netgalley for the arc! I apologise for taking so long to review this title.

I'm one of those people who hated poetry in school because we were forced to recite poems by heart or analyse them for weeks without end in sight. Now, as an adult, I've fallen in love with poetry and spent the last years catching up on reading it and even starting to translate it.

I have mixed feelings about this anthology.

I discovered some new poems or poets or re-read some familiar favourites. I really enjoyed the short but informative insights into biographies, meaning and vocabulary (mostly for the Middle English poems). I also deeply appreciate that translators were mentioned whenever applicable. Translators are way too often invisible. Some of the picks were interesting: sometimes Carey picked exactly the poem I wanted to revisit, sometimes he picked a more unknown poem for a well-known poet or provided multiple short poems/extracts or further recommendations.

On the other hand, I feel like this anthology did not offer anything new. The author was upfront about mostly focusing on anglophone poetry and I assume that is his area of expertise, but it felt very similar to a lot of other anthologies I've read. A handful of ancient poets, two Germans, one Persian, otherwise English, American and one or two Irish or Australian. I think the author should have either committed to focusing on 100 anglophone poets or included just a few more international voices (a handful would have been enough).

Also, I understand Ezra Pound is still quite popular to read and study, but there was no mention of his fascism (while for other authors the biography was more careful to at least point out certain beliefs or themes). I'd have preferred to either not mention him at all (and instead feature a non-anglophone poet) or at least included one sentence to point out the scandal surrounding him (which had been quite a big deal at the time).

8 notes

·

View notes