#person: Melvyn Douglas

Text

Three Cary Grant movies in a row!

Script below the break

Hello and welcome back to The Rewatch Rewind! My name is Jane, and this is the podcast where I count down my top 40 most rewatched movies. Today I will be discussing number 28 on my list: RKO’s 1948 comedy Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, directed by H.C. Potter, written by Norman Panama and Melvin Frank, based on the novel by Eric Hodgins, and starring Cary Grant, Myrna Loy, and Melvyn Douglas.

Yes, I’m talking about yet another Cary Grant movie – I warned you there would be a lot of them. In this one, he plays Jim Blandings, an advertising executive who lives in a Manhattan apartment with his wife Muriel (Myrna Loy) and their two children. Tired of feeling crowded, and taken in by an advertisement, they decide to purchase an old house on a large property in Connecticut. They initially resist the idea that the house must be torn down, but ultimately get excited about being able to build one to their own specifications. However, this is not nearly as simple, or as affordable, as they anticipate.

The first time I watched this movie, it was late at night and I was very tired, so I remember almost falling asleep without really getting into it. But I enjoyed it a lot more the second time, and it’s grown on me over the years. I watched it for the first time in 2003, then twice in 2004, and then once each in 2006, 2008 through 2013, 2015, 2016, 2018 through 2021, and then twice in 2022. And while I could barely keep my eyes open the first time I watched it, now I find it difficult to tear them from the screen when the movie is on.

As I’ve said several times in previous episodes, Cary Grant was a brilliant comedic actor, and once again, he is very funny in this movie. Just watching his morning routine in the apartment at the beginning is hilarious. Jim Blandings is very sure of himself, even and especially when he shouldn’t be, and Cary plays that very convincingly and humorously. Myrna Loy is probably best known for playing Nora Charles in the comedy-mystery Thin Man movies, so it should come as no surprise that she is also very funny here. Muriel occasionally tries to rein in some of Jim’s recklessness, but also gets caught up in the dream of the house, and Loy portrays that flawlessly. Apparently critics thought these stars were too old for these roles (they were both in their mid-40s at the time), and that it would have made more sense to show a naïve young couple not knowing how to build a house, but personally I think it works better to show a middle aged couple who have every reason to believe they know what they’re doing find out that they have no clue. The movie also makes it clear that it’s only because Jim is older and more established in his career that he’s able to do this. At one point when he’s venting about how everything’s costing way more than they were anticipating, Jim points out that if he can barely afford it, there’s no way a young couple ever could. And looking at this movie from a modern lens is kind of surreal because like, imagine a single-income family of four being able to afford a house! To put things in perspective, Jim Blandings was making $15,000 a year in 1948, which is the equivalent of approximately $190,000 in 2023, and the final cost of his dream house was $38,000, or approximately $480,000 now. It certainly costs a lot more than he initially thinks it will, but it’s still doable for him – although he does nearly lose his job at one point – whereas it would not have been for a young couple just starting out. And again, Cary Grant and Myrna Loy are so delightful to watch that I cannot comprehend wanting to replace them.

The acting and the writing encourage the audience to laugh at both Jim and Muriel while still finding them sympathetic. There’s a rather beautiful poetic justice in the story of an advertising executive, who spends all day figuring out how to convince people to buy things they don’t need and can’t afford, getting convinced by an ad to build a house he doesn’t need and can’t afford. And yet, we still want him to succeed, and share his frustration when things go wrong. Muriel’s extremely specific demands for the house can be ridiculous, but we still want her to get the dream house she desires. Perhaps her greatest moment in the film is when she spends several minutes describing in detail the exact shade she wants each room painted: one should exactly match the color of fresh butter, one needs to be white – not a cold, antiseptic hospital white, but not to suggest any other color but white; another should be practically an apple red, somewhere between a healthy Winesap and an unripened Jonathan, etc. When she finally gets distracted and walks away, one of the painters says to the other, “You got all that?” and the other replies, “Red, green, blue, yellow, white.” It’s very funny, but also maybe a little bit sexist, in a “These silly women and their ridiculous obsession with detail” way, but at least the movie makes fun of Jim too. He’s constantly taking charge of things he doesn’t understand and making them worse – from illegally authorizing the old house to be torn down to inadvertently instructing builders to rip out their work. So rather than making fun of Jim and Muriel specifically, the movie is really making fun of the gender roles they feel obligated to fulfill, and the way society has made basic needs like shelter immensely complicated to obtain. And while some of that is rather painful to face, this movie manages to make the overall experience mostly enjoyable. It’s thought-provoking without becoming too upsetting.

While a lot of what I love about this movie comes from Grant and Loy, I also love Melvyn Douglas’s performance, and his character, Bill Cole, is probably my favorite. Bill narrates portions of the movie, and introduces himself to the audience as “Jim’s lawyer and quote best friend unquote.” He’s kind of the voice of doom regarding the dream house project, pointing out all the ways Jim gets taken advantage of along the way and repeatedly advising him to give up, but far from being a stick in the mud, he has an excellent sense of humor, and goes along for the ride only slightly reluctantly. There’s a trope that’s especially common in movies from this era of a married couple having a male “friend of the family” who is interested in the wife and kind of waiting for her to either leave her husband for him, or at least have an affair with him. The character of Hank Entwistle in Monkey Business is like this, and there’s a character in the movie I’m going to talk about next week like this. Bill Cole is almost like this, and Jim certainly sees him like this for a good chunk of the movie, but the way I see him, he’s not actually interested in Muriel that way, and is, in fact, if not canonically queer, certainly queer-coded. We do know that he dated Muriel in college. At one point when Jim asks Muriel why Bill’s always hanging around them instead of getting married, Muriel says it’s because he could never find another girl like her, but this doesn’t seem like it’s meant to be particularly serious. When Jim objects to the fact that Bill always takes his leave by shaking Jim’s hand and kissing Muriel on the cheek, Muriel dryly inquires if Jim would prefer it the other way around. There is also a running joke about Jim and Bill getting stuck in a closet, so modern audiences might interpret that to mean that they’re secretly gay, although I’m pretty sure the closet metaphor wasn’t commonly used in 1948. Bill doesn’t seem to really show any attraction toward either Jim or Muriel, so of course I’m inclined to headcanon him as aroace. We do find out that Muriel somehow ended up with both Bill’s and Jim’s fraternity pins – which the Blandings daughters find along with her old diary in the process of moving into the new house. When Jim then confronts Muriel about her having been in love with Bill, she laughs and responds with, “Of course I was in love with Bill! In those days I was in love with a new man every week!” She considers her time dating Bill to be relatively meaningless, and currently sees him as a good friend. Most of Jim’s bouts of jealousy in the movie seem to be misplaced frustration with the way things are going with the house and/or his job, rather than in response to any of Muriel or Bill’s behavior, which is part of the film’s effective commentary on how gender roles leave men feeling like they can’t express their emotions honestly.

Anyway, one evening, when Jim is working late because a slogan he’s been struggling to come up with for months is due the following morning, Bill stops by the new house to visit Muriel, and there’s a major rainstorm. A neighbor informs Muriel that her phone isn’t working and a nearby bridge is out, so her children can’t get home from school, but they’re staying with a different neighbor on the other side of the bridge. This also means that Bill can’t get home, so he’ll have to spend the night in the house alone with Muriel. When he half-jokingly gasps, “Think of my reputation!” Muriel responds with, “Don’t worry, Snow White, you’ll be just as pure and unsullied in the morning as you were the night before,” and he says, “That’s the story of my life.” Now, I feel like there are a couple different ways to interpret this. One way – the allo-heteronormative way – is that they would like to sleep together, but she’s happily married, and he respects that, so they resist. I’m not saying that’s an invalid interpretation, but something about the way they deliver those lines, and the way they interact in the rest of the movie, doesn’t quite feel like that to me. Another interpretation is that they don’t want to sleep together, and they just want to make sure they’re on the same page about that. Think about how much better it makes the scene if Bill is asexual, and his “Think of my reputation!” is his way of making a joke out of not feeling comfortable with the situation, and her response is reassuring him that she understands and doesn’t see him that way either, and his “That’s the story of my life” is him trying to pretend to be disappointed because an allonormative world tells him he should be, but he’s actually relieved. This could also be because Bill is gay, or straight or bi and just not attracted to Muriel, but even then, the point about defying social expectations still stands. Since long before I knew the terms “aromantic” or “asexual,” I have been drawn to stories about people who are expected to fall in love and/or sleep together and then don’t. It has always felt so encouraging to see adults maintaining close platonic relationships, even when society tells them they shouldn’t be platonic. So I love that Bill and Muriel are friends who can spend the night in the same house without becoming overwhelmed by passion or whatever seems to usually happen in situations like that.

Of course, in this particular case, due to production codes there was basically no chance that they would commit adultery anyway, and all of this is probably definitely me reading way too much into something that’s barely there. The following morning, when Jim makes it back home – after giving up on the slogan even though he knows he’ll be fired – and finds out that Bill spent the night, there’s a bunch of other stuff going on with the contractor telling them about more expenses they’ve incurred, but Jim is particularly upset about Bill being there. Then one of the workers shows up at the house and declares, “There’s a matter of twelve dollars and 36 cents” and Jim loses it, going off on a whole rant saying things like, “Why stop there? Just take everything I have!” until the worker clarifies, “No, I owe you $12.36.” Suddenly Jim’s anger melts away, and he also loses every trace of jealousy and suspicion. This certainly supports what I said earlier about Jim’s jealousy really being misplaced frustration, which I also think supports the idea that Bill is asexual, and that even if people didn’t use that term at that time, at least on some level both Jim and Muriel understand that Bill is not a threat to their marriage. Jim is only jealous because he feels like he should be, and it’s a convenient and socially acceptable outlet for his real feelings. The last shot of the movie is of the Blandings family enjoying their front yard, with Jim reading the book the movie is based on. He looks up and says to the audience, “Drop in and see us sometime” and then Bill moves into frame and adds, “Yeah, do that, won’t you?” implying that he has been accepted as practically part of the family, and that if he is aroace, he’s certainly not alone, and I absolutely love that.

I’ve mentioned before that part of why there are so many Cary Grant movies in my top 40 is because I have a multi-day marathon around his birthday every year, and Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House is almost always part of that. I tend to watch this one on his actual birthday because the only specifically Cary Grant-related item of clothing I own is a long-sleeved t-shirt I got for Christmas in 2007 with a quote from this movie on it, which I will probably wear every January 18 for the rest of my life, even though I kind of have mixed feelings about the context of the quote in the movie. The slogan that Jim gives up on during that fateful stormy night is for a product called Wham, which is a brand of ham. He spends all night trying to come up with an acceptable slogan, but they’re all terrible. I would like to point out that he’s working on this with his female secretary, which means he has even less reason to be jealous of Muriel spending all night with Bill, but that’s not really important. I also feel the need to tell you about my favorite bad slogan he comes up with: “This little piggy went to market, as meek and as mild as a lamb. He smiled in his tracks when they slipped him the axe; he KNEW he’d turn out to be Wham!” The extremely concerned look on his secretary (played by Lurene Tuttle)’s face when she hears that is so perfect. But anyway, he finally gives up and goes home, and after all the drama of finding Bill there and owing more money but also getting a refund, the maid Gussie (played by Louise Beavers) is serving breakfast, and when the girls ask if there’s ham, she replies with, “Not just ham; Wham! If you ain’t eatin’ Wham, then you ain’t eatin’ ham!” And Jim does a double take and then exclaims, “Give Gussie a $10 raise!” and then we see a magazine ad featuring Gussie’s face and this slogan, and I have some questions. What exactly did he mean by a $10 raise? Ten dollars per hour? Per week? Per year? Also did he actually give her credit for coming up with the slogan, or did they just use her words and likeness without her really getting anything out of it, apart from this ambiguous raise? Part of me likes to think that she got hired by Jim’s advertising agency after this, but I feel like the more likely explanation is that a white man took credit for a black woman’s work. So again, I have some mixed feelings about my shirt that has a picture of a ham on it with the words “If you ain’t eatin’ Wham, then you ain’t eatin’ ham!” But despite its weirdness and its flaws, I mostly have positive feelings toward this movie. And I will never forget the joy I felt the one and only time someone who hadn’t watched this movie with me recognized the quote from that shirt, so shout out to my 12th grade history teacher.

Thank you for listening to me discuss yet another Cary Grant movie. I do apologize if you’re getting tired of hearing about him, but at least each of the four Cary Grant movies I’ve talked about so far has been from a different decade, so hopefully that has added enough variety to keep things interesting. Next up is another 1940s movie, although Cary Grant was not in it, so you’ll get a break from hearing about him, for now. In previous episodes I’ve ended with a single line from the next movie, but for this one I have to quote a three-line exchange between two people, because it’s my favorite part of the movie and I can’t help myself. “And then I heard a noise, and then I saw-” “What kind of a noise?” “…Like a sound.”

#mr blandings#mr blandings builds his dream house#cary grant#myrna loy#melvyn douglas#aroace headcanons#rewatch rewind

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

have you seen theodora goes wild?? i keep rewatching it, its so delightful to me!!! i really love the divorce of lady x too and it really reminds me of it!!!

i have!!! i loved the concept of the good girl in a small town secretly being the one to write a salacious novel, especially when she had to agree with everyone that it was deviant and reprehensible, like thats very delicious to me. irene dunne is also absolutely adorable in it, like when she's trying to posture as a big society women and wears all those outrageous outfits but she's actually still very sweet inside... i feel like thats one of the reasons i like screwball comedies so much is that the women are often written in such intriguing ways, like they have so much personality, which a lot of modern movies fail to achieve... plus i love farces

^ very cute even though melvyn douglas' character is being a little bit of an ass at this point in the movie

loved this big feather outfit she wore. so many good promo images for this movie

#u should watch 'bluebeard's eighth wife' i found it to be VERY divorce of lady x#MIDNIGHT ALSO WATCH MIDNIGHT 1939 A GIF OF IT IS PINNED TO MY BLOG. IT'S SOOO

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CLAUDETTE COLBERT & MELVYN DOUGLAS

as Kay Denham & George Potter in

I MET HIM IN PARIS (1937) dir. Wesley Ruggles

#filmedit#oldhollywoodedit#classicfilmedit#I Met Him in Paris#Claudette Colbert#Melvyn Douglas#category: I Met Him in Paris#person: Claudette Colbert#person: Melvyn Douglas#*mygifs#*imhipedit#the funniest part about this movie is that less than half of it takes place in paris#i guess it's called 'i MET him in paris'#not 'i became steadily more fixated on his sarcastic best friend in paris'

345 notes

·

View notes

Text

JULIE DOING “STUFF” WITH FAMOUS PEOPLE (7th post)

Julie and columnist, Hedda Hopper famous for her big hats and big flapping gossip.

“The biggest liar in the world is They Say.” —poet, Douglas Malloch

In a publicity photo for FLOWING GOLD, Julie poses with his costar, Frances Farmer. She struggled personally, was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and institutionalized several times.

Frances and Julie were also cast mates in the GROUP THEATRE production of GOLDEN BOY in 1937, and she had an affair with Julie’s friend, writer Clifford Odets. It is said that Julie later campaigned for her to get the film role in FLOWING GOLD to help her.

Hanging with Lee J. Cobb in the actor’s dressing room while appearing together in a Broadway revival of GOLDEN BOY in 1952.

Hedy Lamarr and not sure who on the right chill In Julie’s dressing room between filming scenes for TORTILLA FLAT. Maybe Julie was getting guitar lessons😃.

John Garfield sitting at table strumming ukulele surrounded by (left to right) Kermit Bloomgarden, Robert Lewis, Aline MacMahon, Harry Carey, and Will Lee (with Philip Loeb standing in back) during rehearsals for the stage production HEAVENLY EXPRESS. (NYPL DIGITAL FILE COLLECTION)

Julie training with professional boxer, Johnny Indristano for his role in BODY AND SOUL.

In 1940 Julie, Anne Shirley, producer Hal Wallis, and "Miss Finland," Aune Franks, discuss plans for the great Motion Picture Finnish Relief benefit at Grauman's Chinese Theater. Anne was his costar in SATURDAY’S CHILDREN.

Although the picture is a bit fuzzy, it’s fun to see Julie and Edward G. Robinson sharing a laugh. They starred in THE SEA WOLF and were contract players at Warner Bros. They only starred together once, but it seems they crossed paths a lot.

Well, here’s Julie with former U. S. President Ronald Reagan back in his film days. Pictured from left: Kay Eldridge, Charlie Ruggles, Jane Wyman, Ronald Reagan, Alice Talton, Edward G. Robinson and Julie. They were in Sonoma for 1941 for the premiere of THE SEA WOLF. The two men on the right starred along with Ida Lupino, who wasn’t in the photo.

If you want to see photos of the celebrities from Old Hollywood then check this one out! Julie is peeking in the back middle in this group of some of the most famous film stars of their time. They are gathered to sign a petition to urge an economic break with Nazi Germany in 1938.

Pictured: Claude Rains, Paul Muni, Edward G. Robinson, Mr.Hornblow (Myrna Loy's husband), Mrs. Melvyn Douglas, Gloria Stuart, James Cagney, Groucho Marx, Aline McMahon, Henry Fonda, Gale Sondergaard, Myrna Loy, Melvyn Douglas, and Carl Laemmle. (Laemmle was a German-American film producer and the co-founder and, until 1934, owner of Universal Pictures.)

#john garfield#old Hollywood#Julie doing stuff with famous people#edward g robinson#hedda hopper#Frances farmer#ronald reagan#hedy lamarr#anne shirley#Bette Davis#James Cagney#Paul Muni#lee j. cobb#Julie doing “stuff” with famous people

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

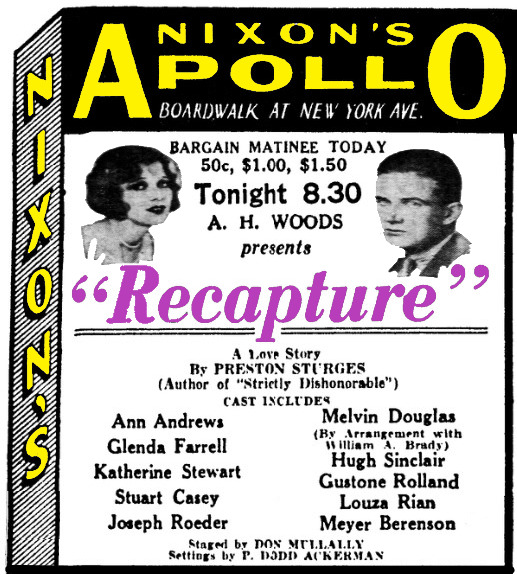

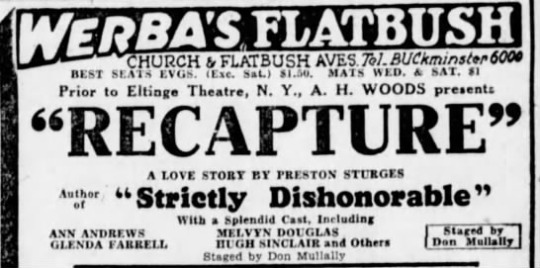

RECAPTURE

1930

Recapture is a play by Preston Sturges. It was originally produced by A.H. Woods and staged by Don Mullally. It starred Ann Andrews and Melvin (Melvyn) Douglas.

The Harry Martins, five years divorced, meet at a hotel in Vichy, France, where she arrives with a new admirer and he comes a-week-ending with a girl named Bunny. Immediately at sight of the wife who had left him, Mr. Martin's love is rekindled, and the former Mrs. Martin is stirred to something resembling a divine curiosity. They agree to elude their respective companions and try to recapture the love that once was. Mr. Martin is convinced that life is wonderful again, but his ex remains miserably unhappy. She concludes that she does not, cannot love Harry Martin and, tragedy though it may be, that's that.

This was Sturges' third play on Broadway. His second, the hit Strictly Dishonorable, was still running at the Avon Theatre, just three blocks away. It attracted interest from Hollywood, and Sturges was writing for Paramount by the time Recapture premiered.

Melvyn Douglas began acting on Broadway in 1928 at the age of 27. In 1960, he received a Tony Award for his work in The Best Man, his penultimate Broadway play. His career also soared in Hollywood, where he won two Oscars: in 1964 for Hud, and in 1980 for Being There. Along with his Tony, his 1968 Emmy made him a ‘triple crown’ winner of all three of acting’s top honors. For Recapture, Douglas was ‘loaned out’ by his manager William Brady to producer Woods.

The play had its world premiere in Atlantic City at Nixon’s Apollo Theatre on January 13, 1930.

After a week on the Boardwalk, it went to Werba’s in Flatbush.

Recapture opened on Broadway at the Eltinge 42nd Street Theatre (later the Empire) on January 29, 1930.

In the play, the leading lady dies when an elevator gets stuck between floors and crashes to the ground.

“The elevator is mechanically a good job. It works. It carries one, two, three persons up one, two, three floors. And when it falls it falls grandly. But it is merely a built up stage effect, and while it carries a moment's thrill, it is so artificially approached and so unsatisfactorily motivated a conclusion that the play crashes with it.” ~ BURNS MANTLE

“If Mr. Sturges entertains with jokes manufactured from incredible misunderstandings of English and American slang, jokes hardly worthy of him, he makes up for it partly from time to time with a spontaneous bit of humor of the sort so common in the first act of ‘Strictly Dishonorable.’ Throughout the play, however, he is a young dramatist attempting a kind of play he is not equipped to write.” ~ ARTHUR POLLACK

“Many of Preston's friends advised against his permitting ‘Recapture’ to be produced as written. His current manager A.H. Woods begged him to rewrite his last act before he put the play to the Broadway test. But be would have none of this advice. He wanted to discover what his own judgment amounted to. The discovery, I suspect, has proved slightly jarring to his vanity.”

The overall feeling was that Sturges had set a high bar with Dishonorable, and Recapture paled (and failed) by comparison. The play shuttered after just 24 performances at the Eltinge. Producer Woods’ contract stipulated that he must keep the play in production for three weeks before being able to negotiate film rights. After the 24th performance of three 8-performance weeks, it promptly closed - on a Tuesday! Sturges licked his wounds in Palm Beach, collecting royalties from the recently published book of Strictly Dishonorable, the film of which was in cinemas by December 1931. Ten years later, he won an Oscar.

#Preston Sturges#Recapture#Eltinge 42nd Street Theatre#Nixon's Apollo Theatre#Atlantic City#Melvyn Douglas#A.H. Woods#Broadway#Broadway Play#Broadway Theatre#Stage#Burns Mantle

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madame Sul-Te-Wan

Madame Sul-Te-Wan (born Nellie Crawford; March 7, 1873 – February 1, 1959) was an American stage, film and television actress for over 50 years. The daughter of former slaves, she began her career in entertainment touring the East Coast with various theatrical companies and moved to California to become a member of the fledgling film community. She became known as a character actress, appeared in high-profile films such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916), and easily navigated the transition to the sound films.

Nellie Crawford was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to former slaves Cleon De Londa and Silas Crawford. Her father left the family early in her life, and her mother became a laundress for Louisville stage actresses. Young Nellie became enchanted by watching the young actresses rehearse when she delivered laundry for her mother. When she was older she moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, joined a theatrical company called Three Black Cloaks, and began billing herself as Creole Nell. She also formed her own theatrical companies and toured the East Coast. After moving to California, Madame Sul-Te-Wan began her film career in uncredited roles in director D. W. Griffith's controversial 1915 drama Birth of a Nation. Sul-Te-Wan had allegedly written Griffith a letter of introduction after hearing that Griffith was shooting a film in her Kentucky hometown. Griffith had intended that he would play a rich landowner who spits in the face of a woman who slights him. The scene was cut by the censors but Madame Sul-Te-Wan was hired at $3 a day and this became the first contract for a black woman when she was hired at $25 a week. Sul-Te-Wan had managed to get the role by her extravagant dress which caught Griffith's attention.

In the early 1900s, Sul-Te-Wan married Robert Reed Conley. They had three sons, but Conley abandoned his family when the third boy was only three weeks old. Two of her sons, Odel and Onest Conley, became actors and appeared in several films. Some of these film featured their mother.

Following her roles for Griffith, Madame Sul-Te-Wan followed up in 1916 with a role in the Anita Loos-penned drama The Children Pay with Lillian Gish and in 1917 with Gish's sister Dorothy in the Edward Morrissey-directed drama Stage Struck.

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, Madame Sul-Te-Wan would establish herself as a publicly recognizable character actress. In 1918 she appeared (uncredited) in Tarzan of the Apes as Jane's maid, Esmerelda. Most often appearing in "Mammy" roles alongside such popular actors of the silent film era as Tom Mix, Leatrice Joy, Matt Moore, Mildred Harris, Harry Carey, Robert Harron, and Mae Marsh. She appeared in the 1927 James W. Horne-directed Buster Keaton comedy College, and in the 1929 Erich von Stroheim-directed drama Queen Kelly, starring Gloria Swanson.

Madame Sul-Te-Wan transitioned into the talkie era with relative ease and continued to appear in high-profile films alongside such prominent film actors as Conrad Nagel, Barbara Stanwyck, Fay Wray, Richard Barthelmess, Jane Wyman, Luise Rainer, Melvyn Douglas, Lucille Ball, Veronica Lake and Claudette Colbert. However, as a black woman in the era of segregation, she was consistently limited to appearing in roles as minor characters who were usually convicts, "native women", or domestic servants, such as her role as a "Native Handmaiden" in the 1933 box-office hit King Kong. Despite the motion picture industry's limitations for African-American performers, Sul-Te-Wan worked consistently throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

In 1937, Sul-Te-Wan was cast in the memorable role of Tituba in the film Maid of Salem, a dramatic retelling of the events surrounding of the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. The film starred Claudette Colbert, Fred MacMurray, Gale Sondergaard, Pedro de Cordoba, and Louise Dresser and was rather financially successful. Sul-Te-Wan's performance garnered critical praise.

On September 12, 1953, a banquet was held at the Hollywood Playground Auditorium to honor Madame Sul-Te-Wan by motion picture actors and film personalities. Amongst the 200 guests who attended the event were Louise Beavers, Rex Ingram, Mae Marsh, Eugene Pallette and Maude Eburne.

In 1954, Sul-Te-Wan appeared in the Otto Preminger directed and almost entirely African-American cast musical drama Carmen Jones opposite Dorothy Dandridge, Harry Belafonte, Diahann Carroll, and Pearl Bailey as Dandridge's grandmother. The film marked a departure for Sul-Te-Wan, who after appearing onscreen for over four decades, was finally able to act in a role that was atypical of her "Mammy" roles. The pairing of Dandridge and Sul-Te-Wan in Carmen Jones spawned a still widely believed but erroneous rumor – that Sul-Te-Wan was Dandridge's actual grandmother (some allege that she is Dandridge's great-grandmother). However, there is no merit to the claim and the two women are unrelated.

At age 77, Sul-Te-Wan married for the second time, to German immigrant Anton Ebentheuer. The marriage lasted three years. During the 1950s, while in her 80s, she continued to appear onscreen in a number of well-received films, albeit now mostly in smaller bit parts and often uncredited. Her last screen appearance came in the 1958 Anthony Quinn-directed adventure film The Buccaneer, starring Yul Brynner and Charlton Heston.

On February 1, 1959, Madame Sul-Te-Wan died after suffering a stroke at the age of 85 at the Motion Picture Actors' Home in Woodland Hills, California.[10] She was interred at the Pierce Brothers' Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood, Los Angeles County, California.

In 1986, she was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. Sul-Te-Wan was the first black actor, male or female, to sign a film contract and be a featured performer.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madame_Sul-Te-Wan

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Authoritarianism?...

I watch a lot of classic films. I also dabble in a decent amount of literature. The goal which I set in Apple Books some time ago is 10 pages a day. Not a shockingly large amount, I know, but consistently taking in a little something to think about and come back to the following day. Sometimes I go far over and read 40 pages. Other times I get five pages into a thing and fall asleep or my attention is taken elsewhere. Tangentially, I love that it counts when I’ve listened to x-amount of pages worth of an audiobook that's being read to me. I find it funny when someone mentions reading a particular book and then, always at the end of this discussion, mentions it was an audiobook. Deciding whether or not this constitutes actual reading is subjective I suppose. It's also an extremely modern, iPhone Age phenomenon. On the other hand, you didn't look at anything! Isn't looking at letters a stipulation for reading? From everything I know and all that I've forgotten from my schooling, it would seem to me that seeing letters on a page, or nowadays on a screen, is fundamental to the task. On the other-other hand, when you read to yourself you do speak to yourself (even if it's in your own mind) in the same way that the reader reading the audiobook speaks to you, right?!

As you can see I'm not going to be able to pin down an opinion on this one without careening recklessly into a 1930's/1940's slapstick comedy routine so I'll just move on...

Watching old movies and reading isn't all I do, but it’s a decent portion of my weekly consumption of art, culture, media, technology, and so on.

In that vein, I’d like to celebrate a quirky set of intersections I've recently run into on this front by looking at two rather lovely films. Each with a literary bend. Each investigates the dynamics of being a writer and ideas of authorship. The differences between how a person relates to what they create when the creation moves from out of the privacy of the shadows and becomes public. These films involve writers who for one reason or another would like to remain undiscovered as the authors of their works. Both have shrouded themselves from recognition as authors of their titles by using pseudonyms. The spark that sets each story into motion is the threat of being unmasked; push out away from the comfort of anonymity. The fear for them is that others, the people they are closest to, the people they love, and yet have been lying to, will find out the truth.

The first film is---

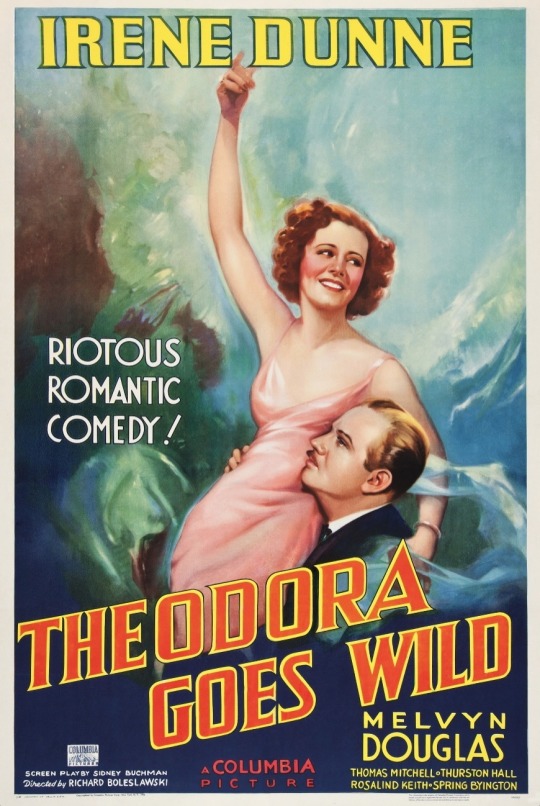

Theodora Goes Wild (1936)

In Theodora Goes Wild, Irene Dunne plays the title character, Theodora Lynn. She is secretly the author of a salacious novel written under the pen name, Caroline Adams. She must hide her identity from the residents of her small, conservative Connecticut town. Their disapproval of the material in the book is fierce. When Theodora goes to New York to visit her publisher, she meets the book's cover artist, Michael Grant, played by Melvyn Douglas, who tries to convince her to reveal herself as the real author. When Theodora falls for Michael, she soon finds that he has secrets of his own.

The film is a raucous, slap-stickesque comedy that is never dull. I say "esque," because it doesn't too far into the ridiculous. It stays grounded. It has some real heart to it. Especially in the relationship between the two leads, but also with every family member, friend, and townsperson along the way. Some of those living in this small town though cast aspersions on this mystery writer unnecessarily. Their actions cause a lot of tension and grief and in the end, they must come face to face with their own hypocritical natures.

And, the second film is---

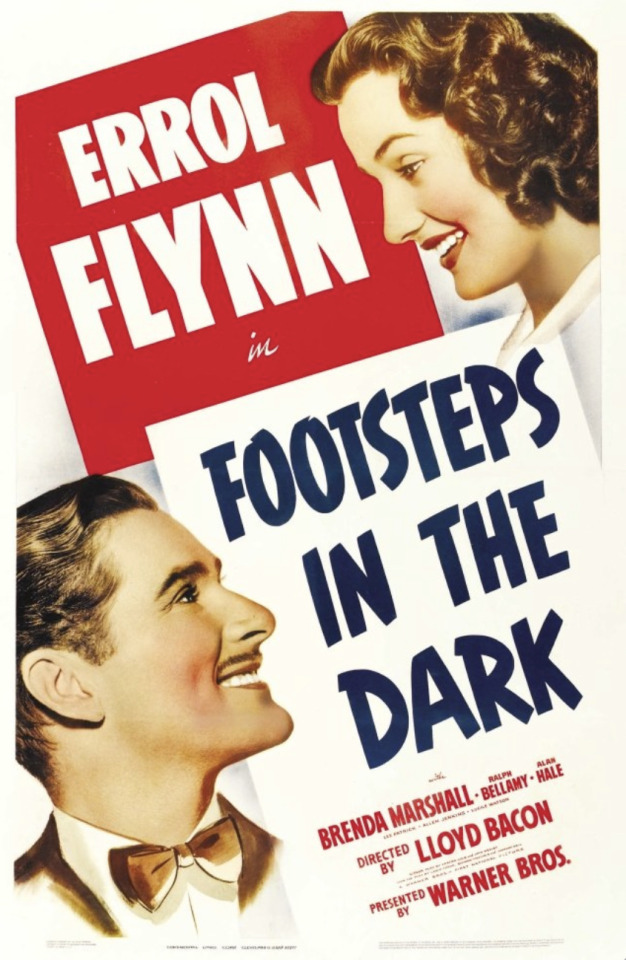

Footsteps in the Dark (1941)

In Footsteps In The Dark, Errol Flynn plays Francis Warren, an investment adviser who moonlights secretly as the author of detective novels. He writes under the pseudonym, F.X. Pettijohn. When a client who wants to cash in a stash of jewels is murdered, Francis believes that -- with his insight into the criminal world -- he can solve the case. His first suspect, however, meets a mysterious end. As the investigation grows more complicated than Francis imagined, he is unexpectedly accused of infidelity by his wife, Rita played by Brenda Marshall, and also suspected by the police.

This film is light, but not without its serious moments. Flynn is his usual suave, debonair self, with flourishes of boyish innocence and witty charm. It’s a whodunnit where the gifted amateur who shouldn't be the one trying to figure out this case is just as confused as we are throughout most of the investigation.

---

For ages writers, musicians, actors and performers of all kinds have used pen names. Did you know that Michael Caine’s real name is Maurice Joseph Micklewhite Jr.?...

Okay, okay Michael Caine it is! Gosh!

Sometimes for artists, it is a decision due to “the times,” like in the case of George Eliot, author of the 19th-century novel Middlemarch, better known to her friends as Mary Ann Evans. Other times, the name just sounds cool and who says you can't, right?! Whether it be to conceal a true identity for consideration of one's own reputation as the characters in these films do, or just to spice life up a bit, the truth is we cast judgments (positive or negative; fairly or unfairly) on the thing which represents a creative works existence. The name of the entity which penned the letters. That can be a very scary thing that every creative person must wrestle with in their work. The burden of ownership. But, that's what makes putting your name on it or giving a name to it so very interesting.

I myself find it quite exciting and I like to think up names from time to time in the hopes of just such an occasion coming along.

How about you?! What would your pen name be?

All and all these two films are splendid. They feature old Hollywood stars who I completely adore. They hit on themes that I am always interested in seeing onscreen and they cover topics that enrich my life. I can't recommend these films more highly. You won't regret a second you spend enjoying them. So what are you waiting for?! Go!

#errol flynn#irene dunne#michael caine#pennames#authors#classicfilm#writing#reading#pseudonym#george eliot#film history#co#comedy#1930s movies#1930s#1940s movies#1940s

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gregory Peck and Ava Gardner Meet in The Great Sinner by Jill Blake

Long before his most popular and Academy Award-winning role as the stoic and honorable single father and small Southern town lawyer Atticus Finch in TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD (‘62), Gregory Peck had established himself as a versatile leading man. It all goes back to 1944, when Peck made his feature-film debut in Jacques Tourneur’s Days of Glory, which outside of Peck being quite young and handsome, is an otherwise forgettable film and performance. But despite a rather unimpressive start, Peck rebounded, and by 1950 had earned four Academy Award nominations for performances in THE KEYS OF THE KINGDOM (‘44), THE YEARLING (‘46), GENTLEMAN’S AGREEMENT (‘47) and TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH (‘49). While he often joked throughout his career that it always seemed like he was only offered movies passed on by his good friend Cary Grant, by the end of the 1940s Gregory Peck was considered one of Hollywood’s best and most popular leading men.

Meanwhile, Ava Gardner was also finally finding her stride in her career, just three years after her breakout performance in the film noir THE KILLERS (‘46), directed by Robert Siodmak. Prior to that role, Ava had been featured mainly in shorts and uncredited roles in feature-length films, but was unfortunately better known for her personal and romantic life, which included a brief marriage to Mickey Rooney, which was exploited for publicity by MGM and served as fodder for the tabloids. However, by the end of the 1940s, Gardner was well on her way to securing a spot amongst the top leading ladies of the day.

In 1949, the same year as his Oscar-nominated performance in Henry King’s TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH, Peck was cast in THE GREAT SINNER, directed by Robert Siodmak and featuring an all-star cast, including Gardner, Melvyn Douglas, Ethel Barrymore, Walter Huston, Frank Morgan and Agnes Moorehead. Peck is Fedja, a writer who is interested in studying and writing about the culture of gambling and gamblers in the German city of Wiesbaden. It is there where Fedja meets the beautiful Pauline Ostrovsky, who is engaged to Armand de Glasse (Melvyn Douglas), the owner of a casino. Their engagement is not one of love, but out of desperation: Pauline’s father owes a considerable amount in gambling debts to De Glasse and her arranged marriage will serve as payment. During his research of the gamblers in the casino, Fedja remains an outsider, merely observing patterns and behaviors. But once Fedja learns of Pauline’s fate, he intervenes, and begins gambling with the sole purpose of winning enough to buy her freedom from De Glasse. Of course, gambling has a stronger pull than Fedja had anticipated, and he finds himself falling victim to the thrill and desperation that often accompanies it.

Based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Gambler, published in 1866, and with an adapted screenplay by Christopher Isherwood, THE GREAT SINNER fell short of capturing the essence of Dostoevsky’s original story. Originally a project for Warner Brothers several years prior, MGM obtained the rights to the story and hired Robert Siodmak to direct. The production was long and difficult, with the first cut of the film being three hours long. Siodmak was under immense pressure by the studio to make sure the film was high quality and prestigious—no doubt to entice Oscar voters come time for awards season. After a first round of edits that significantly reduced the runtime, MGM ordered Siodmak to helm a series of reshoots emphasizing the love story between Gregory Peck’s Fedja and Ava Gardner’s Pauline. Siodmak wanted no part of it, forcing the studio to go with another director, Mervyn LeRoy.

Many of LeRoy’s reshot scenes made it into the final movie, but he remained uncredited for his work. Ten years after the film’s release, in 1959, journalist John Russell Taylor spoke with Siodmak for Sight and Sound magazine. The director spoke about his experience making THE GREAT SINNER and expressed frustrations with the finished product saying, “When I eventually saw the finished film, I don’t believe that a single scene was left as I had made it.” THE GREAT SINNER failed to be the prestige picture MGM had hoped it would be, resulting in both a critical and commercial misfire.

While THE GREAT SINNER was a box-office failure at the time of its release, it’s not a terrible film, especially given the incredible talent involved. Actually, it’s quite a solid, second-tier studio picture. Not exactly what MGM had originally envisioned, but it’s fair to say that it has benefitted a bit from the passage of time and a reassessment by modern audiences seeking out the work of Siodmak and the all-star cast. It’s always a joy to see the likes of Peck, Gardner, Huston, Douglas, Barrymore, Morgan and Moorehead at work. While the film has largely been forgotten, even amongst those in the classic film community, it was a significant film for both Gregory Peck and Ava Gardner, and fans of both actors should definitely watch their performances in this film. Why?

While not particularly influential for Peck and Gardner’s careers individually, it kicked-off an on-screen partnership between the two that resulted in them starring together twice more in THE SNOWS OF KILIMANJARO (‘52) and ON THE BEACH (‘59). It was also the beginning of a close friendship between them that lasted until Gardner’s death in 1990. Of all his many leading ladies, which included Sophia Loren, Audrey Hepburn, Ingrid Bergman, Deborah Kerr and Lauren Bacall, Peck always said that Ava Gardner was his favorite. Peck recalled his professional relationship and friendship with Gardner saying, “She was much better than she thought she was. She had no vanity about her talent, but she will stay in the minds of millions. ... She did nothing that lowered her standards as an actress or as a lady. ″

THE GREAT SINNER might have not been the film that director Robert Siodmak or MGM had originally envisioned, but it brought together two beautiful and talented actors for the first time. And while it would be of interest to see Siodmak’s uncut version of the film, one must be grateful for Mervyn LeRoy’s reshoots, incorporating more “romantic” elements, as it brought us a few steamy moments between Peck and Gardner—GIF’d for your enjoyment—Dostoevsky’s story be damned.

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stolen Faces

Cinema is an art of faces, almost a religion of faces: on screen they loom above us, vast as a mother’s face must appear to an infant. We can get lost in them. The deepest thrill the movies offer may be the opportunity to gaze at human faces longer and with more unabashed, lover-like intimacy than real life regularly allows. Most often, of course, we gaze at beautiful faces, though cinema has its share of beloved gargoyles, mugs with “character” rather than symmetry. But the uncanny power of faces onscreen also anchors films about disfigurement and facial transformations, about masks and scars and plastic surgery. These stories summon all the fears and taboos, desires and unresolved questions swirling around the human face. Do faces reveal or conceal a person’s true nature? Can changing someone’s face change their soul?

Deformity is a staple of horror films, of course, from classics such as Phantom of the Opera and The Raven (in which the hideously afflicted man played by Boris Karloff muses, “Maybe if a man looks ugly, he does ugly things”) to surgical shockers such as Eyes Without a Face. But plot twists involving faces that are damaged or corrected, masked or changed, turn up with surprising frequency in film noir as well, where they are related to themes of identity theft, amnesia, desperate attempts to shed the past or recover the past. One of the grim proverbs of noir is that you can’t escape yourself. There are no fresh starts, no second chances. But noir also demonstrates the instability of identity, the way character can be corrupted, and stories about facial transformations harbor a nebulous fear that there is in the end no fixed self. If noir is pessimistic about the possibility of change, it is at the same time haunted by fear of change—fear of looking in the mirror and seeing a stranger.

The Truth of Masks

Two films about men who literally lose their faces take the full measure of the resulting ostracism and crushing isolation—and what men will do to escape it. Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Face of Another (Tanin no Kao, 1966) is based on a Kobo Abe novel about a scientist named Okuyama who has been literally defaced by a chemical accident. We never see what he used to look like; he spends half the film swaddled in bandages like Claude Rains in The Invisible Man, ferocious black eyes glinting through slits. Obsessed with people’s reactions to his appearance, he lashes out bitterly, insisting that all his social ties have been severed, including his conjugal ties with his wife. She tries to convince him that it’s all in his head and that her feelings haven’t changed, but her revulsion when he makes an abrupt sexual advance convinces him that she’s lying.

Okuyama believes that a life-like mask will restore his relationship with his wife and his connection to society. He has evidently not seen The Face Behind the Mask (1941), a terrific B noir in which Peter Lorre stars as Johnny Szabo, who is hideously scarred in a fire. This tragedy and the ensuing cruelty of strangers transform him from a sweet, Chaplin-esque immigrant to a bitter criminal mastermind, even after he dons a powder-white mask that gives him a sad, creepy ghost of his former face—more Lorre than Lorre. The mask is merely a flimsy patch on the horrible visage that spiritually scars Johnny, and though it enables him to marry a sweet and loving (and perhaps near-sighted) woman, it can’t reverse the corrosion of his character.

The doctor who makes a far more sophisticated mask for Okuyama does so because the project fascinates him as a psychological and philosophical experiment. He speculates about what the world would be like if everyone wore a mask: morality would not exist, he argues, since people would feel no responsibility for the actions of their alternate identities. (His theory seems to be borne out by the consequences of internet anonymity.) Unlike the one Johnny Szabo wears, here the mask bears no resemblance to Okuyama’s original looks, and the doctor believes the new face will change his patient’s personality, turning him into someone else.

When the mask is fitted, it turns out to be the face of Tatsuya Nakadai, one of the most striking and plastic pans in cinema history. With only a little help from a fake mole, dark glasses, and a bizarre fringe of beard, Nakadai succeeds in making his own features look eerily synthetic, as though they don’t belong to him. Sitting in a crowded beer hall on his first masked outing in public, he creates a palpable sense of unease, keeping his features unnaturally still as though unsure of their mobility, touching his skin gingerly to explore its alien surface. As he gradually grows more comfortable and revels in the freedom of his new face, the doctor tells him, “It’s not the beer that’s made you drunk, it’s the mask.”

Abe’s novel contains a scene in which the protagonist goes to an exhibit of Noh masks, highly stylized crystallizations of stock characters and emotions. In Noh, as in other traditional forms of theater that use masks, the actor is present on stage but vanishes into another physical being—men play women, young men play old men, gods, and ghosts. In cinema, actors impersonate other characters using their own faces—usually without even the heavy layer of makeup worn on western stages. Movie actors are pretending to be people they’re not, yet if we judge their performances good it means we believe what we see in their faces. When an actor’s real face plays the part of a mask, like Lorre’s or Nakadai’s, this strange inversion—the real impersonating the artificial—has a uniquely disconcerting effect.

At the heart of this disturbing film lurks a horror that changing the skin can indeed change the soul. Okuyama tries to hold onto his identity, insisting, “I am who I am, I can’t change,” but the doctor insists he is “a new man,” with “no records, no past.” In covering his scar tissue with a smooth, artificial skin he eradicates his own experience, and with it his humanity. The doctor turns out to be right when he predicts that the mask will have a mind of its own. Suddenly endowed with sleek good looks, Okuyama buys flashy suits and sets out to seduce his own wife. When he succeeds easily, he is outraged, only to have her reveal that she knew who he was all along. After she leaves him in disgust he descends into madness and random violence. He has become the opposite of the Invisible Man: a visible shell with nothing inside

Okuyama’s story is interwoven with a subplot about a radiation-scarred girl from Nagasaki, whose social isolation drives her to incest and suicide. Lovely from one side, repellent from the other, she looks very much like the protagonist of A Woman’s Face. Ingrid Bergman starred in the Swedish original, but Joan Crawford is ideally cast in the 1941 Hollywood remake directed by George Cukor. Half beautiful and half grotesque, half hard-boiled and half vulnerable, Anna Holm spells out what was usually inchoate in Crawford’s paradoxical presence. A childhood fire has left her with a gnarled scar on one side of her face, like a black diseased root growing across her cheek and distorting her eye and mouth. Crawford makes us feel Anna’s agonizing humiliation when people look at her, which spurs her compulsive mannerisms of turning her head aside, lifting her hand to her cheek, or pulling her hair down.

Also perfectly cast is Conrad Veidt as the elegant, sinister Torsten Baring. Veidt went from German Expressionist horror—playing the goth heartthrob Cesar in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and the grotesquely disfigured yet weirdly alluring hero of The Man Who Laughs—to an unexpected late-career run as a sexy leading man in cloak-and-dagger films such as The Spy in Black and Contraband. When Anna turns her head defiantly to reveal her scar, Torsten gazes at her with a gleam of excitement, even of perverse attraction. She is confused and touched by his kindness and gallantry, helplessly trying to hide her sensitivity beneath a tough façade. Her broken-up, uncertain expressions when he gives her flowers or kisses her hand count as some of the most delicate acting Crawford ever did. Anna assumes that Torsten, the penniless scion of a rich family, must want her to do some dirty work, and she turns out to be right, but he also genuinely appreciates the proud, bitter, lonely woman who faces down her miserable lot through sheer strength of will.

People are horrible to Anna, nastily mocking her wounded vanity and her attempts to look nice. “The world was against me,” she says, “All right, I’d be against it.” She has found the perfect outlet, blackmailing pretty women who commit adultery. In one of the film’s best scenes, the spoiled and kittenish wife she is threatening retaliates by shining a lamp in Anna’s face and laughing at her. Anna leaps at the woman and starts hitting her over and over, forehand and backhand, in an ecstasy of hatred. This savagely satisfying moment is derailed by the film’s first grossly contrived plot twist, as the encounter is interrupted by the woman’s husband, who happens to be a plastic surgeon specializing in correcting facial scars. He offers to operate on Anna, and once the bandages are removed, in a scene orchestrated for maximum suspense, an absurdly flawless face is revealed.

The doctor (Melvyn Douglas) calls her both his Galatea and his Frankenstein: he views her as his creation, but isn’t sure if she’s an ideal woman or an unholy monster, “a beautiful face with no heart.” Her dilemma is ultimately which man to please, whose approval to seek: the doctor who believes her character should be corrected now that her face is, or Torsten, who wants her to kill the young nephew who stands between him and the family estate. This overwrought turn is never plausible; it is always obvious that Anna is no child murderer. What is believable is her erotic thrall to Torsten, the first man who has ever shown an interest in her. Crawford is at her most unguarded in these moments of trembling desire; Cukor remarked on how “the nearer the camera, the more tender and yielding she became.” He speculated that the camera was her true lover.

Anna undergoes months of pain and uncertainty for the chance of being beautiful for Torsten, and there is a marvelous shot of her gazing at herself in a mirror as she prepares to surprise him with her new face, brimming with hard proud joy. But he winds up lamenting the surgery that has turned her into “a mere woman, soft and warm and full of love,” he sneers. “I thought you were something different—strong, exciting, not dull, mediocre, safe.” In this same speech, Torsten reveals himself as a cartoonish fascist megalomaniac, which fits in with the film’s slide into silly, flimsily scripted melodrama, but sadly obscures the radical spark of what he’s saying. Anna’s character is shaped by the way she looks, or rather by the way she is looked at by men; the disappointingly conventional ending sides with the man who equates flawless beauty with moral goodness, and against the one man who was able to see something fine—a “hard, shining brightness,” in a woman’s damaged and imperfect face.

A Stolen Face (1952) follows a similar premise, much less effectively, and reaches the opposite conclusion. Paul Henreid plays a plastic surgeon who operates on female criminals with disfiguring scars, convinced that once they look normal they will become contented law-abiding citizens. He gets carried away, however, sculpting one patient into a dead ringer for his lost love (Lizabeth Scott plays both the original and the copy) and marrying her. His attempt to play Pygmalion backfires, since the vulgar, mean-spirited and untrustworthy ex-con is unchanged by her new appearance: she is indeed “a beautiful face without a heart.” That is a succinct definition of the femme fatale, a type Lizabeth Scott often played and one that embodies a fascination with the deceptiveness of feminine beauty. In The Big Heat (1953), it is only when Debbie (Glora Grahame) has her pretty face rearranged by a pot of scalding coffee that she abandons her cynical self-interest to become an avenging angel, fearlessly punishing the corrupt who hide their greed behind a genteel façade. She has nothing left to lose; pulling a gun from her mink coat and plugging the woman she recognizes as her evil “sister,” the disfigured Debbie asserts her freedom: “I never felt better in my life.”

Blessings in Disguise

Sometimes, people are only too happy to lose their faces. Dr. Richard Talbot (Kent Smith), the protagonist of the superb, underappreciated drama Nora Prentiss (1947), sees the bright side when his face is horribly burned in a car crash. He has already faked his own death, sending another man’s corpse over a cliff in a burning car. In a neat bit of poetic irony, by crashing his own car he has completed the process of destroying his identity, and no longer needs to fear he’ll be recognized. Losing his face is a blessing in disguise—or rather, a blessing of disguise. But the disfigurement is also a visual representation of the corruption of his character: his face changes to reflect his downward metamorphosis with almost Dorian Gray-like precision.

Car crashes are a kind of refrain in the film. The doctor’s routine existence veers off course when a taxi knocks down a nightclub singer, Nora Prentiss (Anne Sheridan), across the street from his San Francisco office. Talk about a happy accident: the nice guy trapped in an ice-cold marriage to a rigid, nagging martinet suddenly has a gorgeous, good-humored young woman stretched out on his examining table. Nora may sing for a living, but her real vocation is dishing out wisecracks (her first words on coming to are, “There must be an easier way to get a taxi.”) When the doctor mentions a paper he’s writing on “ailments of the heart,” the canary, her eyelids dropping under the weight of knowingness, quips, “A paper? I could write a book.”

It’s hard to imagine a more sympathetic pair of adulterers, but the doctor is so daunted by the prospect of asking his wife for a divorce that it seems simpler to use the convenient death of a patient in his office to stage his own demise and flee to New York with Nora. It’s soon clear, though, that some part of him did die in San Francisco. Cooped up in a New York hotel room, terrified of going out lest someone spot him, the formerly gentle man becomes an irascible, rude, nervous wreck. When the faithful and incredibly patient Nora goes back to singing for Phil Dinardo (Robert Alda), the handsome nightclub owner who loves her, Talbot becomes hysterically jealous. Unshaven and hollow-eyed, he slaps Nora and almost kills Dinardo before fleeing the police and heading into that fiery crash. He becomes, as the film’s evocative French title has it, L’Amant sans Visage, “the lover without a face.”

When his bandages are removed, he is unrecognizable, wizened and scarred, his face a creased and calloused mask. His own wife doesn’t know him, and when Nora visits him in prison his damaged face, shot through a tight wire mesh, looks like something decaying, dissolving. He’s in prison because, in an even neater bit of irony, he has been charged with his own murder. He decides to take the rap, recognizing the justice of the mistake: he did kill Richard Talbot.

This same ironic plot twist appears in Strange Impersonation (1946), albeit less convincingly. This deliriously far-fetched tale, directed at a breakneck pace by Anthony Mann, stars Brenda Marshall as Nora Goodrich, a pretty scientist whose glasses signal that she is both brainy and emotionally myopic. She is harshly punished for caring more about work than marriage: her female lab assistant, who wants to steal Nora’s fiancé, tampers with an experiment so that it explodes, burning Nora’s face to a crisp. Embittered, she retreats from the world, and when another woman, who is trying to blackmail her over a car accident, falls from the window and is mistakenly identified as Nora, she seizes the opportunity to disappear, have plastic surgery that miraculously eliminates her scars, and return posing as the blackmailer, to seek revenge. She goes to work for her former fiancé, who strangely fails to recognize her voice or her striking resemblance to his lost love.

The plot plays out as, and turns out to be, a fever dream, but this last credibility stretcher is too common to dismiss as merely the flaw of one potboiler. Plots involving impersonation and identity theft rely not only on unrealistic visions of what plastic surgery can achieve, but on the assumption that people are deeply unobservant and tone-deaf in recognizing loved ones. A film that underlines this blindness with droll irony is The Scar (a.k.a. Hollow Triumph and The Man Who Murdered Himself, 1948), a convoluted but hugely entertaining little B noir in which Paul Henreid plays dual roles as a crook on the run and a psychologist who happens to look just like him. John Muller, pursued by hit men sent by a casino owner he robbed, stumbles across his doppelganger and decides to kill him and take his place. All he needs to do is give himself a facial scar to match the doctor’s. Only as he is dumping the body does he notice that he has put the scar on the wrong cheek—the consequence of an accidentally reversed photograph. But the irony quickly doubles back: Muller decides to brazen it out, and in fact no one notices that the doctor’s scar has apparently moved from one side of his face to the other—not even his lover. (Joan Bennett glides through this awkward part in a world-weary trance, giving a dry-martini reading to the script’s most famous lines: “It’s a bitter little world, full of sad surprises.”) The assumption that people pay little attention to the way others look or sound seems directly at odds with the power that faces and voices wield on film, and the intimate specificity with which we experience them. But noir stories often turn on how easily people are deceived, and how poorly they really know one another—or even themselves.

In The Long Wait (1954), perhaps the most extreme case of confused identity, a man with amnesia searches for a woman who has had plastic surgery. Not only does he not know what she looks like now, he can’t even remember what she used to look like. Since the movie is based on a Mickey Spillane story, he proceeds methodically by grabbing every woman he sees, in hopes that something will jog his memory. The film is fun in its pulpy, trashy way, provided you enjoy watching Anthony Quinn kiss women as though his aim were to throttle the life out of them. Quinn plays a man badly injured in a car wreck that erases both his memory and his fingerprints. This is lucky when he wanders into his old town and discovers he is wanted for a bank robbery—without fingerprints, they can’t arrest him. Figuring he must be innocent, he goes in search of the girlfriend who may or may not have grabbed the money and gone under the knife. It’s an intriguing premise, but the ultimate revelation of the right woman feels arbitrary, and the implications of all this confusion of identities are left resolutely unexamined. Nonetheless, there is something in the film’s searing, inarticulate desperation that glints like a shattered mirror.

Under the Knife

The promise of plastic surgery is a new and better self, the erasure of years and the traces of life. Taken to extremes, it is the opportunity to become a different person. Probably the best known plastic surgery noir is Dark Passage (1947), in which Humphrey Bogart plays Vincent Parry, who visits a back alley doctor after escaping from San Quentin. Parry was framed for killing his wife, so the face plastered across newspapers with the label of murderer has become a false face that betrays him. A friendly cabby who spots him recommends a surgeon who is he promises is “no quack.” Houseley Stevenson’s gleeful turn as the back-alley doctor is unforgettable, as he sharpens a straight razor while philosophizing about how all human life is rooted in fear of pain and death. He can’t resist scaring Parry, chortling over what he could do to a patient he didn’t like: make him look like a bulldog, or a monkey. But he reassures Parry that he’ll make him look good: “I’ll make you look as if you’ve lived.”

During the operation, Parry’s drugged consciousness becomes a kaleidoscope of faces, all the people who have threatened or helped him swirling around. His face is being re-shaped, as his life has already been shaped by others: the bad woman who framed him and the good woman who rescues and protects him, the small-time crook who menaces him and the kind cabby who helps him. Faceless for much of the movie, mute for part of it (he spends a long time in constraining bandages), Vincent Parry is among the most passive and cipher-like of noir protagonists. When the bandages finally come off after surgery, he looks like Humphrey Bogart, and the idea that this famously beat-up, lived-in face could be the creation of plastic surgery is perhaps the film’s biggest joke. But Vincent Parry remains an oddly blank, undefined character, and he seems unchanged by his new face and name. In a sense the doctor is right: he only looks as though he’s lived.

The fullest cinematic exploration of the problems inherent in trying to make a new life through plastic surgery is Seconds (1966), John Frankenheimer’s flesh-creeping sci-fi drama about a mysterious company that offers clients second lives. For a substantial fee, they will fake your death, make you over completely—including new fingerprints, teeth, and vocal cords—and create an entirely new identity for you. There is never a moment in the movie when this seems like a good idea. The Saul Bass credits, in which human features are stretched and distorted in extreme close-up, instills a horror of plasticity, and disorienting camera-work creates an immediate feeling of unease and dislocation, a physical discomfort at being in the wrong place.

Arthur, a businessman from Scarsdale, is the personification of disappointed middle age, afflicted by profound anomie that goes beyond a dull routine and a tired marriage. When the Company finishes its work—the process is shown in gruesome detail, to the extent that Frankenheimer’s cameraman fainted while shooting a real rhinoplasty—the formerly nondescript and greying Arthur looks like Rock Hudson, and has a new life as a playboy painter in Malibu. He’s told that he is free, “alone in the world, absolved of all responsibility.” He has “what every middle-aged man in America wants: freedom.”

At first, however, his life proves as empty and meaningless in this new setting as it was in the old; even when the Frankenstein scars have healed, he remains nervous and joyless as before. After he meets and falls for a beautiful blonde neighbor, who introduces him to a very 1960s California lifestyle, he begins to revel in youth and sensual freedom. Yet something is still not right; at a cocktail party he gets drunk and starts talking about his former existence—a taboo. He discovers that his lover, indeed almost everyone he knows, is an employee of the company or a fellow “reborn,” hired to create a fake life for him, and to keep him under surveillance. His “freedom” is a construct, tightly controlled.

Arthur rebels, making a forbidden trip to visit his wife, who of course does not recognize him. Talking to her about her supposedly deceased husband, for the first time he begins to understand himself: the depth of his alienation and confusion, the fact that he never really knew what he wanted, and so wanted the things he had been told he should want. Seconds is a scathing attack on the American ideal of a successful life, a portrait of how corporations sell fantasies of youth, beauty, happiness, love; buying into these commercial dreams, no one is really free to know what they want, or even who they are. Will Geer, as the folksy, sinister founder of the Company, talks wistfully about how he simply wanted to make people happy.

There is a deep sadness in the scenes where Arthur revisits his old home and confronts the failure of his attempt at rebirth—beautifully embodied by Rock Hudson in a performance suffused with the melancholy of a man who has spent his life hiding his real identity behind a mask. Yet Arthur still imagines that if he can have another new start, a third face and identity, he will get it right. Instead, he learns the macabre secret of how the Company goes about swapping out people’s identities. Seconds contrasts the surgical precision with which faces, bodies, and the trappings of life can be remade, and the impossibility of determining or predicting how or if the inner self will be changed. For that there are no charts or diagrams, and no knife that can cut deep enough.

by Imogen Sara Smith

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(OC) Cube The Mini Imposter

My Very First Among Us OC

Bio: Cube Mini Imposter

Name: Cube

Gender: Male

Birthday: June 4th

Sexuality: Straight

Species: Mini Imposter

Relationship/Girlfriend: None Yet

Family Members:

Cole (Mother)

Micole (Mother)

James (Grandpa)

Victoria (Grandma)

Midnight (Grandpa)

Nivian (Grandma)

Noora (Sister)

Maxwell (Brother)

Marlin (Brother)

Noel (Sister)

Manfried (Brother)

Marlyssa (Brother)

Moses (Brother)

Nerissa (Sister)

Nuna (Sister)

Nea (Sister)

Mickey (Brother)

Cloris (Youngest Sister)

Madea (Youngest Sister)

Olivia (Youngest Sister)

Hailee (Youngest Sister)

Cube (Youngest Brother)

Starr (Youngest Sister)

Micola (Niece)

Sander (Niece)

Sandro (Nephew)

Sammy (Nephew)

Micolette (Niece)

Suzette (Niece)

Sandriana (Niece)

Michelette (Niece)

Michela (Niece)

Sanderson (Nephew)

Michel (Nephew)

Michele (Nephew))

Delora (Niece)

Dallan (Nephew)

Dallin (Nephew)

Nova (Niece)

Nikolas (Nephew)

Danae (Niece)

Danni (Niece)

Danna (Niece)

Nooriel (Nephew)

Darry (Nephew)

Dooley (Nephew)

Marlo (Nephew)

Audey (Nephew)

Adya (Nephew)

Audley (Nephew)

Adney (Nephew)

Marrin (Niece)

Marry (Niece)

Morris (Nephew)

Audric (Nephew)

Auden (Nephew)

Austen (Nephew)

Marten (Nephew)

Moselle (Niece)

Aryan (Nephew)

Aryeh (Nephew)

Marabella (Niece)

Marabelle (Niece)

Arysta (Niece)

Marcelo (Nephew)

Marcel (Nephew)

Malin (Nephew)

Ariella (Niece)

Arielle (Niece)

Mellisa (Niece)

Mick (Nephew)

Melissza (Niece)

Melisha (Niece)

Mel (Nephew)

Micki (Niece)

Mickie (Niece)

Mike (Nephew)

Mikko (Nephew)

Melvyn (Nephew)

Nollan (Nephew)

Rylan (Nephew)

Ryland (Nephew)

Renae (Niece)

Noeletta (Niece)

Ryden (Nephew)

Nohl (Nephew)

Noella (Niece)

Ryenne (Niece)

Noely (Niece)

Evans (Nephew)

Maxima (Niece)

Margolette (Niece)

Margo (Nephew)

Evanam (Nephew)

Maxon (Nephew)

Maxton (Nephew)

Evanne (Niece)

Evander (Nephew)

Evanna (Niece)

Katie (Cousin)

Kylar (Cousin)

Coal Jr (Cousin)

Aleiza (Cousin)

Zeke (Cousin)

Tabarious (Cousin)

Tavio (Cousin)

Adalley (Cousin)

Tamburlaine (Cousin)

Fuzzy (Cousin)

Sabrina (Younger Cousin)

Ayden (Younger Cousin)

Nikole (Younger Cousin)

Koal (Younger Cousin)

Cortney (Youngest Cousin)

Nicoletta (Youngest Cousin)

Nicola (Youngest Cousin)

Nicco (Youngest Cousin)

Nicole (Aunt)

King Coal (Uncle)

Nikson (Uncle)

Nirvana (Aunt)

Audrina (Sister in law)

Arilyn (Sister in law)

Melissa (Sister in law)

Marcos (Brother in law)

Clover (Sister in law)

Sunset (Sister in law)

Elaine (Sister in law)

Candace (Sister in law)

Danny (Brother in law)

Ryder (Brother in law)

Evan (Brother in law)

Karl (Brother in law)

Personality: Expert Imposter, Gamer, Cool, Friendly, And Prankster

Friends:

Pinky ( My bestie's oc and Best Friend)

Winkle (2nd best friend)

Phiney

Boston

Forest

Snowden (3rd Best Friend)

Myron (My bestie's oc and 4th best friend)

Pez (My bestie's oc and 5th best friend)

Freddy (My bestie's oc and 6th best friend)

Honey (My bestie's oc)

Braxton (My bestie's oc and 7th best friend)

Sparkie (Our oc and 8th best friend)

Stein (Our oc)

Andreas (Our oc)

Shauni (Our oc)

Philon (Our oc and 9th best friend)

Faris (My bestie's oc and 10th best friend)

Douglas

Xavier (My bestie's oc and 11th best friend)

Finn

Woody (Our oc and 12th best friend)

Favorite Color: Lime

Favorite Season: Summer

Favorite Holiday: Memorial Day

Fun Fact: Cube is named after a villager from ACNH, name Cube. Cube is an expert mini imposter. He doesn't get caught not even once when he kill a Crewmate. Because he is an expert at not getting caught. When he isn't out killing. He plays video games. He love playing video games with his mother Cole most of all. He also likes to kill her the most. Because she's he's mother. In Mario games and Among us. He can be cool at times. He may be an expert imposter. But he likes to be cool for he's friends. He is also a huge mama's boy. Because he spends more time with his mother Cole then he's other mother Micole. He is very friendly, he may be an expert impster. But he can be friendly. And he is also a prankster. He love pulling pranks on his sister Starr and his mother Micole a lot. Because he's a prankster. He sometimes pranks his mother Cole when she isn't paying attaching. Because he love pranking her.

Cube belong to me

Credit to my number one bestie yoshilover1000 on FA for he's design

Among Us: Belong to Inner Sloth

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trivia: 2018 Oscar Winners

Green Book is the worst movie to win Best Picture since Crash in 2005! Exciting times!

With Roma’s all-but-guaranteed win in Foreign Language Film, it marks Mexico’s first ever win in that category. It is the fourth win in the category for a Latin American country (the third was last year, for Chile’s A Fantastic Woman).

Also for Roma -- director/cinematographer/writer Alfonso Cuarón became the first ever winner of the Best Cinematography category to also serve as director for his film. It is also the first black-and-white film to win this category since Schindler’s List in 1993. Similarly, Cuarón is the first person to win Best Director for a film he acted as cinematographer on.

Similarly, Roma is the first foreign language film to win Best Director.

In decades past, there would be a split between the Best Picture winner and the Best Director winner approximately once every ten years. However, since the implementing of the preferential ballot system for Best Picture, the Green Book/Roma split is the fifth one since 2010. In all situations, the Best Director winner was tech-heavy (Life of Pi, Gravity, The Revenant, La La Land, Roma) while the Best Picture winner was decidedly more a showcase for acting and writing (Argo, 12 Years a Slave, Spotlight, Moonlight, Green Book). It’s important to note all of the Best Director winners won at least tech award and all of the Best Picture winners won for screenplay.

Another Roma stat! Cuarón’s victory in Director is the fifth win for a Mexican director since 2013 (when Cuarón won his first Oscar for Gravity). Alejandro G. Iñárritu won in back-to-back years (2014′s Birdman and 2015′s The Revenant) while Guillermo del Toro won last year for The Shape of Water.

And final Roma stat, I promise: Alfonso Cuarón is now the fourth person to win two Best Director Oscars for two Best Picture losers. He joins Ang Lee (Brokeback Mountain, 2005, and Life of Pi, 2012), George Stevens (A Place in the Sun, 1951, and Giant, 1956), and Frank Borzage (Seventh Heaven, 1928, and Bad Girl, 1932).

The 21st Century Deborah Kerr and Thelma Ritter: Glenn Close and Amy Adams keep their records as the living actors with most nominations and no wins. Close has seven; Adams has six. Both lost to first-time nominees this year.

Olivia Colman’s somewhat surprising win for The Favourite marks the second time someone won in the Best Actress category for playing a queen. The first was Helen Mirren as Queen Elizabeth II in The Queen in 2006.

Every Best Picture nominee left the ceremony with at least one win.

Green Book is Universal’s first Best Picture winner since 1993′s Schindler’s List. It’s the first time one of the old major Hollywood studios has won Best Picture since Warner Bros.’s Argo in 2012.

Mahershala Ali is the 4th person to win two acting Oscars in two different Best Picture winners. His win for Green Book was his second after he won for Moonlight in 2016. He joins Marlon Brando (Best Actor 1954 for On the Waterfront and Best Actor 1972 for The Godfather), Gene Hackman (Best Actor 1971 for The French Connection and Best Supporting Actor 1992 for Unforgiven), Dustin Hoffman (Best Actor 1979 for Kramer vs. Kramer and Best Actor 1988 for Rain Man), and Jack Nicholson (Best Actor 1975 for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Best Supporting Actor 1983 for Terms of Endearment -- he would also later win Best Actor 1997 for Best Picture nominee As Good As It Gets). He is the first actor of color with this distinction. Only men have achieved this distinction so far.

Mahershala Ali joins Michael Caine, Melvyn Douglas, Anthony Quinn, Jason Robards, Peter Ustinov, and Christoph Waltz as two-time Supporting Actor winners. He is the first black actor to achieve this. Walter Brennan still holds the record in the category with three wins.

Two for two: Mahershala Ali also joins Vivien Leigh, Luise Rainer, Hilary Swank, Christoph Waltz, and Kevin Spacey as two-time acting winners for only two nominations.

Rami Malek is the first non-black person of color to win Best Actor since Ben Kingsley (Gandhi, 1982).

Wakanda, indeed, forever: Hannah Beachler and Ruth Carter (both for Black Panther) made history as the first black women to win Production Design and Costume Design, respectfully.

Black Panther’s three wins mark the first wins ever for a Marvel movie.

Bohemian Rhapsody is the first music-themed film to win Sound Editing. The award has traditionally gone to action or war films.

Domee Shi (Bao) is the first Asian woman to win Animated Short.

Peter Ramsey (Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse) is the first black director to win an Oscar as a director. The category for Best Director has still never had a black winner.

Of all 91 Best Picture winners, the color green is still the only color to be featured in the title of a Best Picture winner: How Green Was My Valley (1941) and Green Book (2018).

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse is the first non-Disney/Pixar winner in Animated Feature since Rango in 2011. Unlike Spider-Verse, Rango had no Disney/Pixar competitors.