#pope calixtus III

Text

Book 46: The Borgias and Their Enemies

The all mighty RNG brought 945 History:Europe:Italy. So I chose Christopher Hibbert's The Borgias and Their Enemies: 1431–1519. It essentially covers Rodrigo Borja's ascent to power to Lucretia Borgia's death with some context before and after.

The first chapter describes how Rome was a shithole even for the middle ages before popes returned to it (they had abandoned it for France for a while) and then there were three goddamned popes even, and finally things settled down and popes returned to Rome and they wanted a strong leader over a pious one necessarily, so they elected Rodrigo Borja, made a cardinal at a precipitously young age by his uncle Pope Calixtus III (Not uncommon, about every Pope of that age - even the more "honest" ones- promoted relatives and friends left and right). And let's be frank, Rodriogo- AKA Pope Alexander VI, was not one of the more "honest" ones.

He was the first Pope to admit to his children being his and not "nephews" as the phrase "nepotism" comes from. And I think that reflects his biggest downfall. His son, Cesare was a bastard in every sense of the word. He killed his brother and brother-in-law and a lot of other people and his dad still supported him and used simony increasingly heavily to fund his wars.

The Borgias (Italian for the Spanish Borja) are quite well known for poison so it was very disappointing to find out historically it seems only to be mentioned in Alexander VI's death, rumored as a poisoning attempt gone wrong, but quite possibly just some pedantic disease. Lucrezia Borgia in particular, aside from having an asshole dad and brother seems to be made out as all right if not a little into secular humor for the time. So, big whoop.

SHOULD YOU READ THIS BOOK: Sure, if you want a rundown of Italian history in the 1400s-to early 1500s I'd give it a go. There's a who's who of that period of Italian history including Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, Titian, the guy who broke Michelangelo's nose (Pietro Torrigiano), Nicholo Machiavelli, etc. The only thing I'd suggest is getting a map of Italy of the time to figure out what the sam hill is so important about Naples, etc.

ART PROJECT:

In a family known for its licentiousness the Feast of the Chestnuts stands out as a particularly bawdy episode in which they gave an orgy in which courtesans groped naked on their hands and knees in cadlelight searching for roasted chestnuts. Sorry for the poor scale in this, as I had an artistic vision in mind and stuck to it.

#the borgias#chestnuts#banquet of the chestnuts#52books#52booksproject#dewey decimal system#rng#christopher hibbert#rodrigo borgia#cesare x lucrezia#pope alexander vi

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

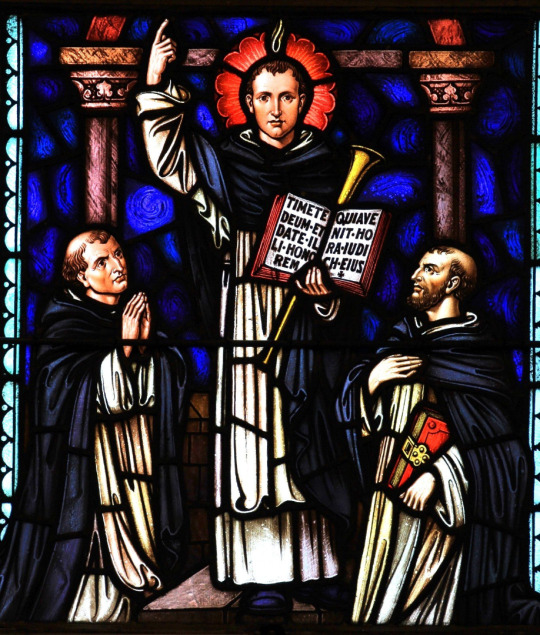

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT VINCENT FERRER

The Patron of Builders and Construction Workers

Feast Day: April 5

"If you truly want to help the soul of your neighbor, you should approach God first with all your heart. Ask him simply to fill you with charity, the greatest of all virtues; with it you can accomplish what you desire."

One of the greatest preachers of the Dominican order and dubbed the 'Angel of the Last Judgment', Vincent Ferrer was born on January 23, 1350 in Valencia.

From his parents (Guillem Ferrer and Constanca Miquel), he learned to love the poor, to fast on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and to have intense devotion to Jesus and Mary. Legends surround Vincent's birth. It was said that his father was told in a dream by a Dominican friar that his son would be famous throughout the world. His mother is said never to have experienced pain when she gave birth to him. He was named after Vincent Martyr, the patron saint of Valencia.

After joining the Order of Preachers (Dominicans) at the age of 18, he soon became a famous preacher, and everywhere, his lectures and sermons met with extraordinary success.

Vincent said to his fellow priests: 'In your sermons, use simple language and precise examples. Each sinner in your congregation should feel moved as though you were preaching to him alone. An abstract discourse hardly inspires those who listen.'

Vincent traveled throughout Europe, preaching mainly on sin, death, hell, eternity and the speedy approach of the day of judgement. He spoke with such energy that most of the listeners confessed their sins and repented from their sinful life. Several priests traveled with him, helping the saint in his ministry.

He instructed them in this fashion: 'When hearing confession, you should always radiate the warmest charity. Whether you are gently encouraging the fainthearted or putting the fear of God into the hardheaded, the penitent should feel that you are motivated only by pure love.'

On April 5, 1419 in Vannes, while delivering his last sermon, Vincent died at the age of 69. He was buried in Vannes Cathedral and was canonized as a saint by Pope Calixtus III in 1455.

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#dominicans#order of preachers#vincent ferrer#vicente ferrer#builders#prisoners#construction workers#plumbers#fishermen#spanish orphanages

0 notes

Photo

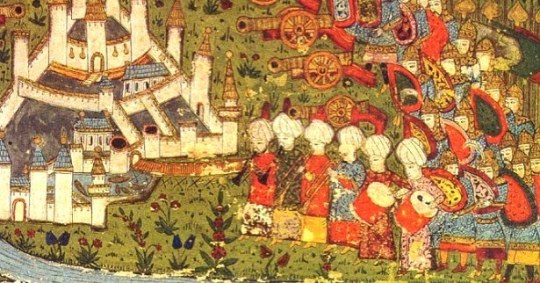

Pope Callisto III reaffirmed the idea of resuming the Crusade of the Church and of Christian principles for the conquest of Constantinople against "the anger of the Turks" from the point where Niccolò V had to suspend it for the coming of death. But he, like his predecessor, despite the preaching and the many ambassadors sent everywhere, had to deal with the shameful indifference of the european rulers against a new venture against infidels. Those rulers were solely committed to defending their interests, and did not consider the Turks threatening their own Western civilization. Charles VII of France long forbade the publication of the Crusade Bull issued in his kingdom on May 15, 1455, as well as forbidding the collecting of the tithes. The same thing happened in other countries. There were those who, like the Duke of Burgundy, collected them but put them in their pockets. In short, no one felt the urgency of a new holy war. Callisto continued to preach and prepare reconciliation with the spirit of a Spanish whose country had for centuries suffer the invasion of Muslims. He was building a fleet of sixteen triremes in Rome, on the Tiber. Ripa Grande became a real shipyard among the amazement of the population. And he, with tears in his eyes for emotion, looked away in the distance from the windows of his palace, the ships coming up from day to day. If Niccolò, his pale predecessor, had been a humanist among humanists, Callisto showed more interest in opposing Ottoman danger than in the diffusion of culture, so much to sell away a large number of precious volumes of the Vatican Library along with many objects of St. Peter's treasure to arm the fleet and drive out the infidels from Europe. Or he deprived those books of their gold-plated ornaments, causing the wrath of the curial letterati. He tore from an ancient, marble sarcophagus, discovered by accident near St. Peter's, all valuable objects, without worrying that the tomb probably contained the remains of Emperor Constantine and one of his sons. He melted the gold and silver found in the grave. From his canteen he banished the silverware saying, "I'm fine with terracotta dishes". The money was never enough, and then the pontiff, with a bull, imposed tithes and promised indulgences to anyone who had somehow helped the anti-Turks enterprise under the exhortation of talented preachers.

Source: Antonio Spinosa - La saga dei Borgia

#i borgia#the borgias#pope calixtus iii#papa callisto III#alonso de borja#alfonso borgia#christian zeal#crusade#church#ottoman empire#maometto ii#constantinople#clement v

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Unlike the majority of sixteenth-century women who worked as silk-weavers, butter-makers, or house servants, Vannozza Cattanei (1452 [?]–1518) was exceptional, as she owned a business in Renaissance Rome, a category of work that, according to Alice Clark in Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century, was the least open to women. Thus, Cattanei, better known as the lover or mistress of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, later Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503), achieved what few women of her time could: she acquired, sold, rented, and administered more than a handful of locande (inns or hotels) in the center of Rome. This essay explores the personal and professional life of Vannozza Cattanei in order to chart her successes as a businesswoman in hotel proprietorship and management, work that allowed her to create a public identity through architecture.

Cattanei was not the typical “invisible” mistress, a term coined by Helen Ettlinger, for her life, her relationships, and her importance as the mother of the Borgia offspring kept her visible throughout history. Historians, art historians, and writers of fiction usually emphasize her roles as the mistress of the powerful Cardinal and as the mother of his children: Juan, Duke of Gandia; the notorious Cesare; Lucrezia, Duchess of Ferrara; and Joffre. Certainly, Cattanei’s life was scandalous by many standards. While married to one man, she lived and slept with, and bore children to another. Her accumulated wealth was not only based on her husbands’ assets, but on her close relationship to Alexander VI. Cattanei’s role as proprietor of successful locande was dependent on three factors coming together in her favor at the right time: money, opportunity, and location.

It was through her marriages and relationship with Alexander VI that Vannozza acquired the needed funds to purchase or rent the buildings that she converted into her hotels. Although little historical evidence remains that illuminates Cattanei’s early life, her adult life, during which she married three times and outlived all of her husbands, is quite well documented. She first wed Domenico da Rignano in 1469, most likely at the age of 27, and widowed for the first time in 1474. Together with Domenico, she purchased a house on the Via del Pellegrino, near Campo dei Fiori, for 500 ducats, of which 310 were from her dowry. Umberto Gnoli believes that this house might have been a gift from Cardinal Borgia as a sort of recompense for Domenico, although he offers no evidence to support this statement.

Cardinal Borgia, while holding the high-ranking office of Vice Cancelliere della Chiesa, an appointment that he received from his uncle, Pope Calixtus III Borgia, built a magnificent palace near the Tiber River, for many years the locus of the relationship between him and Cattanei. However, Cattanei, and eventually the Borgia children, would have claimed their legal domicile to be the house in which she lived with her husband. In 1474, while married to Domenico, Cattanei bore Borgia a son, Juan; a year later, Cesare Borgia was born. Domenico’s death in 1475 left her a widow for the first time. Although no known documents reveal the wealth she possessed at this time, she certainly owned the house on the Pellegrino and she inherited a house whose present-day address is Via di S. Maria in Monticelli. Demolished in the nineteenth century, it once displayed the Rignano family coat of arms.

While a widow, Cattanei gave birth in 1480 to a third Borgia child, a girl named Lucrezia; she then married again. Cattanei’s second husband, Giorgio della Croce, was an educated man from Milan. Why she decided to wed Giorgio is not known, but it might have been a legal agreement so that she could publicly continue her living arrangements with the powerful Cardinal Borgia. Giorgio undoubtedly benefitted from the arrangement; he received a papal appointment in the same year as his wedding. A year later, Cattanei gave birth to a fourth Borgia child, her third son, Joffre. Shortly after Joffre’s birth, Cattanei and the cardinal terminated their cohabitation. By 1486 Cattanei was living with her husband Giorgio; he fathered her next child, Ottaviano, who died after only two months.

At Giorgio’s death that same year, his inventory revealed that he and his wife owned two houses on the Pellegrino and one on the Piazza di Pizzo Merlo because the couple’s only son had died. Widowed again, Cattanei now had legal ownership of all properties. With her relationship as mistress to Cardinal Borgia now over, the widow married again, on June 8, 1486, with a 1000-ducat dowry. Her third husband, the Milanese Carlo Canale, was in the service of Cardinal Giovanni Giacomo Sclafenato of Parma. Both Cardinal Sclafenato and Carlo moved to Rome, where Carlo’s career prospered. Over the next few years, Canale and Cattanei bought vigne and houses in the Rione Monti, not far from the church of San Martino.

Many years later when Cattanei donated considerable sums to charitable organizations, she asked that prayers be said by the priests of San Salvatore for herself and her husbands—save for Domenico whom she excluded. According to Ettlinger, it was often financially advantageous for a man to allow his wife to conduct a carnal relationship with another, usually more powerful man (“Visibilis,” 771). Cattanei and her husbands bought and sold a variety of properties. She also received, as gifts, many items of expensive jewelry. After her relationship with the cardinal had ended and all three husbands had died, she was left a wealthy widow and continued to live in Rome. During her third marriage, she and her husband had started renting and buying locande in the center of Rome, which most probably brought in considerable sums of money.

Cattanei managed at least six of these small hotels, thus making her an accomplished businesswoman. Gnoli wrote that the terms ospizio, locanda, taverna and osteria all meant rented rooms, usually with food service. He estimated a total of sixty establishments in the center of Rome in the second half of the fifteenth century, the period when Cattanei’s business was flourishing. This figure indicates that she controlled about 10% of the hotel business in the central area around Campo dei Fiori, the major outdoor market where most of the small hotels in this period could be found. The circumstances of Cattanei’s career as an owner of small hotels and their locations can be recovered through documentation of sales, rents, and some lawsuits.

She operated at least six hotels, whose exact locations are known, though there remain no records concerning their day-to-day operations. Along the Tiber River was the locanda or osteria named the Biscione, very close to the so-called Tor di Nona, a medieval stronghold of the Orsini; from the early fifteenth century, it was used as a pontifical prison. Not far from the Biscione was the Hosteria della Fontana, the Leone Grande, and the Leone Piccolo. The most famous of her hotels was the Locanda della Vacca, a building still standing on its original corner of the Via dei Cappellari and the Via del Gallo at the edge of the Campo dei Fiori, the site of Rome’s famous market place. On November 10, 1500, Cattanei, under the name Vannozza di Carlo Canale, bought half of the Vacca building from Leonardo Capocci, a priest and canon of St. Peter’s, for 1370 ducats.

Her husband had died by 1500, so she was acting on her own and was in complete control of her own finances during these negotiations. Apparently owning just half of this centrally-located building did not satisfy her, but not until after 1503 was she able to purchase the other half, for the death of Pope Alexander VI and the turmoil that followed likely interfered with the transactions. Documents dated April 1, 1504 refer to her as Vannozza Cataneis de Borgia and verify as false the previous transaction of buying the Vacca and a house on the Via Pellegrino (vendita era stata finta). After the Pope’s death she probably needed to have her claims legalized or at least recognized as valid. She finally acquired the other half of the Vacca building for 1500 ducats from the brothers Pietro, Antonio, and Ciriaco Mattei.

The exact number of rentable rooms in the Locanda della Vacca is uncertain. However, a rough drawing of the ground plan of the building from 1563 exists in the Archivio di Stato, Rome. The three-story building sat at the busy intersection of the Via dei Cappellari and Vicolo del Gallo. The main doorway, on the Cappellari side, functioned as the main entrance. Once inside, corridors led to the many rooms and a courtyard on the ground level, while there were as many as five staircases leading to the rooms on the two superior floors. Along the front of the building were rentable spaces for four shops which at one time were occupied by a wine shop, a meat shop, a shoe shop, and a hair salon, which provided goods and services needed by tourists and visitors.

Cattanei understood the importance of timing and location in real estate. She acquired the first half of the Vacca in 1500—the year when her former lover, now Pope Alexander VI, called a Jubilee Year—so that she profited from renting rooms to the increased number of visitors to Rome. According to a recent article by Ivana Ait, Cattanei’s career as a female proprietor of several small hotels coincides with a surge in the economic life of Rome, largely due to the return of the papacy from Avignon in 1420 that brought a continuous supply of cardinals, ambassadors, and many others to the city. Records indicate that during the Jubilee of 1450 called by Pope Nicholas V, there was a scarcity of food and beds for the many pilgrims to Rome.

… Cattanei’s position as former mistress to the Pope and mother of the Borgia children would have helped ensure a solid standing with the Apostolic Camera during the early years of the sixteenth century. Whereas her beauty and personal charms may have brought her money and opportunity, it was her sharp business acumen, like Agnelucci’s, that helped her establish herself as one of the most successful female proprietors in Rome. Although the number of hotels run by men was certainly greater than those owned by women, Cattanei, Agnelucci, and de’ Calvi bring to light the successful careers of some women, who managed their own businesses in Renaissance Rome. In her later years Cattanei, as a pious widow, bestowed many large charitable gifts on her favorite institutions: she even donated her Locanda della Vacca to the Hospital of S. Salvatore near St. John Lateran.

Her generosity to the Ospedale di S. Salvatore can be documented by quite a large file of original documents clearly dated 1502, which print her name in large letters as Vannozza Borgia de Catanei. In another document, a notary identifies her as Vannozza Cattanei detta anche Borgia, and yet another as Vannozza Borgia dei Cattanei. She was clearly using the Borgia name to fashion her own identity despite the fact that she was never the legal wife of the cardinal. In fact, during her own life Cattanei chose to assume public visibility of her connection to the Borgia family by commissioning Sebastiano Pellegrini da Como to renovate the Locanda della Vacca and display her coat of arms prominently on the façade.

The coat of arms included heraldic symbols of the Cattanei, the Canale, and the Borgia, constructing a public identity that linked her to her father’s line, her husband’s line, and the line of her lover and children. Despite her successes in business and her charitable works, Venetian Senator and historian Marino Sanudo provided the following description of her funeral, dated December 4, 1518: “With the Company of the Gonfalone, [Vannozza Cattanei] was buried in Santa Maria del Popolo. She was buried with pomp almost comparable to a cardinal. [She] was 66 years old and had left all of her goods, which were not negligible, to St John Lateran [location of the Hospital of S. Salvatore]. The funerals of the cubiculari/servants of the Pope’s bedrooms are not solemn occasions to some.”

The report indicates that her generosity to San Salvatore was well known, although her relationship with a cardinal who became pope was equally well known, and overshadowed her accomplishments. I have tried to make the case that Vannozza Cattanei was much more than the whore of a cardinal who later became Pope. She was a wife, a widow, a successful businesswoman, and a pious woman with a long record of charitable activity. Instead of being known solely as the mistress of Alexander VI, or the mother of the Duke of Gandia, she should also be remembered for her business acumen and her piety: for this, she was celebrated in the records of her charitable gifts as La Magnifica Vannozza, a noble and generous benefactress.”

- Cynthia Stollhans, “Vannozza Cattanei: A Hotel Proprietress in Renaissance Rome.” in Early Modern Women

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I’ve been tasked with researching Richard Plantagenet for a paper and thus far found extremely negative accounts of the king, his religious bigotry being a reoccurring theme (his treatment of Jewish dignitaries attending his coronation and his reasoning to join the third crusade etc)

I stumbled across your wonderful tag for Richard at the weekend and wondered if you wouldn’t mind sharing your informed opinion of Richard and his views on religions ? Your writing seems very well balanced regarding his attributes and flaws. Thanks :)

Oof. Okay. So, a short and simple question, then?

Quick note: when I was first reading your ask and saw "Richard Plantagenet," I briefly assumed that you meant Richard Plantagenet, father of Edward IV, or perhaps Richard III, both from the Wars of the Roses in the fifteenth century, before seeing from context that you meant Richard I. While "Plantagenet" was first used as an informal appellation by Richard I's grandfather, Geoffrey of Anjou, it wasn't until several centuries later that the English royal house started to use it consistently as a surname. So it's not something that Richard I would have been really called or known by, even if historians tend to use it as a convenient labeling conceit. (See: the one thousand popular histories on "The Plantagenets" that have been published recently.)

As for Richard I, he is obviously an extremely complex and controversial figure for many reasons, though one of the first things that you have to understand is that he has been mythologized and reinvented and reinterpreted down the centuries for many reasons, especially his crusade participation and involvement in the Robin Hood legends. When you're researching about Richard, you're often reading reactions/interpretations of that material more than anything specifically rooted in the primary sources. And while I am glad that you asked me about this and want to encourage you to do so, I will gently enquire to start off: when you say "research," what kind of materials are you looking at, exactly? Are these actual published books/papers/academic material, or unsourced stuff on the internet written from various amateur/ideological perspectives and by people who have particular agendas for depicting Richard as the best (or as is more often the case, worst) ever? Because history, to nobody's surprise, is complicated. Richard did good things and he also did quite bad things, and it's difficult to reduce him to one or the other.

Briefly (ha): I'll say just that if a student handed me a paper stating that Richard was a religious bigot because a) there were anti-Jewish riots during his coronation and b) he signed up for the Third Crusade, I would seriously question it. Medieval violence against the Jews was an unfortunately endemic part of crusade preparations, and all we know about Richard's own reaction is that he fined the perpetrators harshly (repeated after a similar March 1190 incident in York) and ordered for them to be punished. Therefore, while there famously was significant anti-Semitic violence at his coronation, Richard himself was not the one who instigated it, and he ordered for the Londoners who did take part in it to be punished for breaking the king's peace.

This, however, also doesn't mean that Richard was a great person or that he was personally religiously tolerant. We don't know that and we often can't know that, whether for him or anyone else. This is the difficulty of inferring private thoughts or beliefs from formal records. This is why historians, at least good historians, mostly refrain from speculating on how a premodern private individual actually thought or felt or identified. We do know that Richard likewise also made a law in 1194 to protect the Jews residing in his domains, known as Capitula Judaeis. This followed in the realpolitik tradition of Pope Calixtus II, who had issued Sicut Judaeis in c. 1120 ordering European Christians not to harass Jews or forcibly convert them. This doesn't mean that either Calixtus or Richard thought Jews were great, but they did choose a different and more pragmatic/economic way of dealing with them than their peers. This does not prove "religious bigotry" and would need a lot more attention as an analytical concept.

As for saying that the crusades were motivated sheerly by medieval religious bigotry, I'm gonna have to say, hmm, no. Speaking as someone with a PhD in medieval history who specialised in crusade studies, there is an enormous literature around the question of why the crusades happened and why they continue to hold such troubling attraction as a pattern of behavior for the modern world. Yes, Richard went on crusade (as did the entire Western Latin world, pretty much, since 1187 and the fall of Jerusalem was the twelfth century's 9/11). But there also exists material around him that doesn't exist around any other crusade leader, including his extensive diplomatic relations with the Muslims, their personal admiration for him, his friendship with Saladin and Saladin's brother Saif al-Din, the fact that Arabic and Islamic sources can be more complimentary about Richard than the Christian records of his supposed allies, and so forth. I think Frederick II of Sicily, also famous for his friendly relationships with Muslims, is the only other crusade leader who has this kind of material. So however he did act on crusade, and for whatever reasons he went, Richard likewise chose the pragmatic path in his interactions with Muslims, or at least the Muslim military elite, than just considering them all as religious barbarians unworthy of his time or attention.

The question of how the crusades functioned as a pattern of expected behavior for the European Christian male aristocrat, sometimes entirely divorced from any notion of his private religious beliefs, is much longer and technical than we can possibly get into. (As again, I am roughly summarising a vast and contentious field of academic work for you here, so... yes.) Saying that the crusades happened only because medieval people were all religious zealots is a wild oversimplification of the type that my colleague @oldshrewsburyian and I have to deal with in our classrooms, and likewise obscures the dangerous ways in which the modern world is, in some ways, more devoted to replicating this pattern than ever. It puts it beyond the remit of analysis and into the foggy "Dark Ages hurr durr bad" stereotype that drives me batty.

Weighted against this is the fact that Richard obviously killed many Muslims while on crusade, and that this was motivated by religious and ideological convictions that were fairly standard for his day but less admirable in ours. The question of how that violence has been glorified by the alt-right people who think there was nothing wrong with it at all and he should have done more must also be taken into account. Richard's rise to prominence as a quintessentially English chivalrous hero in the nineteenth century, right when Britain was building its empire and needed to present the crusades as humane and civilizing missions abroad rather than violent and generally failed attempts at forced conversion and conquest, also problematized this. As noted, Richard was many things, but... not that, and when the crusades fell out of fashion again in the twentieth century, he was accordingly drastically villainized. Neither the superhero or the supervillain images of him are accurate, even if they're cheap and easy.

The English nationalists have a complicated relationship with Richard: he represents the ideal they aspire to, aesthetically speaking, and the kind of anti-immigrant sentiment they like to put in his mouth, which is far more than the historical Richard actually displayed toward his Muslim counterparts. (At least, again, so far as we can know anything about his private beliefs, but this is what we can infer from his actions in regard to Saladin, who he deeply respected, and Saladin's brother.) But he was also thoroughly a French knight raised and trained in the twelfth-century martial tradition, his concern for England was only as a minor part of the sprawling 'Angevin empire' he inherited from his father Henry II (which is heresy for the Brexit types who think England should always be the center of the world), and his likely inability to speak English became painted as a huge character flaw. (Notwithstanding that after the Norman Conquest in 1066, England did not have a king who spoke English natively until Henry IV in 1399, but somehow all those others don't get blamed as much as Richard.)

Anyway. I feel as if it's best to stop here. Hopefully this points you toward the complexity of the subject and gives you some guidelines in doing your own research from here. :)

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today the Church remembers St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Monk.

Ora pro nobis.

St. Bernard de Clairvaux, (born 1090 AD, probably Fontaine-les-Dijon, near Dijon, Burgundy [France]—died August 20, 1153 AD, Clairvaux, Champagne; canonized January 18, 1174; feast day August 20), was a Cistercian monk and mystic, the founder and abbot of the abbey of Clairvaux, and one of the most influential churchmen of his time.

Born of Burgundian landowning aristocracy, Bernard grew up in a family of five brothers and one sister. The familial atmosphere engendered in him a deep respect for mercy, justice, and loyal affection for others. Faith and morals were taken seriously, but without priggishness. Both his parents were exceptional models of virtue. It is said that his mother, Aleth, exerted a virtuous influence upon Bernard only second to what Monica had done for Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century. Her death, in 1107, so affected Bernard that he claimed that this is when his “long path to complete conversion” began.

He turned away from his literary education, begun at the school at Châtillon-sur-Seine, and from ecclesiastical advancement, toward a life of renunciation and solitude. Bernard sought the counsel of the abbot of Cîteaux, Stephen Harding, and decided to enter this struggling, small, new community that had been established by Robert of Molesmes in 1098 as an effort to restore Benedictinism to a more primitive and austere pattern of life. Bernard took his time in terminating his domestic affairs and in persuading his brothers and some 25 companions to join him. He entered the Cîteaux community in 1112, and from then until 1115 he cultivated his spiritual and theological studies.

Bernard’s struggles with the flesh during this period may account for his early and rather consistent penchant for physical austerities. He was plagued most of his life by impaired health, which took the form of anemia, migraine, gastritis, hypertension, and an atrophied sense of taste.

Founder And Abbot Of Clairvaux

In 1115 Stephen Harding appointed him to lead a small group of monks to establish a monastery at Clairvaux, on the borders of Burgundy and Champagne. Four brothers, an uncle, two cousins, an architect, and two seasoned monks under the leadership of Bernard endured extreme deprivations for well over a decade before Clairvaux was self-sufficient. Meanwhile, as Bernard’s health worsened, his spirituality deepened. Under pressure from his ecclesiastical superiors and his friends, notably the bishop and scholar William of Champeaux, he retired to a hut near the monastery and to the discipline of a quack physician. It was here that his first writings evolved. They are characterized by repetition of references to the Church Fathers and by the use of analogues, etymologies, alliterations, and biblical symbols, and they are imbued with resonance and poetic genius. It was here, also, that he produced a small but complete treatise on Mariology (study of doctrines and dogmas concerning the Virgin Mary), “Praises of the Virgin Mother.” Bernard was to become a major champion of a moderate cult of the Virgin, though he did not support the notion of Mary’s immaculate conception.

By 1119 the Cistercians had a charter approved by Pope Calixtus II for nine abbeys under the primacy of the abbot of Cîteaux. Bernard struggled and learned to live with the inevitable tension created by his desire to serve others in charity through obedience and his desire to cultivate his inner life by remaining in his monastic enclosure. His more than 300 letters and sermons manifest his quest to combine a mystical life of absorption in God with his friendship for those in misery and his concern for the faithful execution of responsibilities as a guardian of the life of the church.

It was a time when Bernard was experiencing what he apprehended as the divine in a mystical and intuitive manner. He could claim a form of higher knowledge that is the complement and fruition of faith and that reaches completion in prayer and contemplation. He could also commune with nature and say:

Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.

After writing a eulogy for the new military order of the Knights Templar he would write about the fundamentals of the Christian’s spiritual life, namely, the contemplation and imitation of Christ, which he expressed in his sermons “The Steps of Humility” and “The Love of God.”

Pillar Of The Church

The mature and most active phase of Bernard’s career occurred between 1130 and 1145. In these years both Clairvaux and Rome, the centre of gravity of medieval Christendom, focussed upon Bernard. Mediator and counsellor for several civil and ecclesiastical councils and for theological debates during seven years of papal disunity, he nevertheless found time to produce an extensive number of sermons on the Song of Solomon. As the confidant of five popes, he considered it his role to assist in healing the church of wounds inflicted by the antipopes (those elected pope contrary to prevailing clerical procedures), to oppose the rationalistic influence of the greatest and most popular dialectician of the age, Peter Abelard, and to cultivate the friendship of the greatest churchmen of the time. He could also rebuke a pope, as he did in his letter to Innocent II:

There is but one opinion among all the faithful shepherds among us, namely, that justice is vanishing in the Church, that the power of the keys is gone, that episcopal authority is altogether turning rotten while not a bishop is able to avenge the wrongs done to God, nor is allowed to punish any misdeeds whatever, not even in his own diocese (parochia). And the cause of this they put down to you and the Roman Court.

Bernard’s confrontations with Abelard ended in inevitable opposition because of their significant differences of temperament and attitudes. In contrast with the tradition of “silent opposition” by those of the school of monastic spirituality, Bernard vigorously denounced dialectical Scholasticism as degrading God’s mysteries, as one technique among others, though tending to exalt itself above the alleged limits of faith. One seeks God by learning to live in a school of charity and not through “scandalous curiosity,” he held. “We search in a worthier manner, we discover with greater facility through prayer than through disputation.” Possession of love is the first condition of the knowledge of God. However, Bernard finally claimed a victory over Abelard, not because of skill or cogency in argument but because of his homiletical denunciation and his favoured position with the bishops and the papacy.

Pope Eugenius III and King Louis VII of France induced Bernard to promote the cause of a Second Crusade (1147–49) to quell the prospect of a great Muslim surge engulfing both Latin and Greek Orthodox Christians. The Crusade ended in failure because of Bernard’s inability to account for the quarrelsome nature of politics, peoples, dynasties, and adventurers. He was an idealist with the ascetic ideals of Cîteaux grafted upon those of his father’s knightly tradition and his mother’s piety, who read into the hearts of the Crusaders—many of whom were bloodthirsty fanatics—his own integrity of motive.

In his remaining years he participated in the condemnation of Gilbert de La Porrée—a scholarly dialectician and bishop of Poitiers who held that Christ’s divine nature was only a human concept. He exhorted Pope Eugenius to stress his role as spiritual leader of the church over his role as leader of a great temporal power, and he was a major figure in church councils. His greatest literary endeavour, “Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles,” was written during this active time. It revealed his teaching, often described as “sweet as honey,” as in his later title doctor mellifluus. It was a love song supreme: “The Father is never fully known if He is not loved perfectly.” Add to this one of Bernard’s favourite prayers, “Whence arises the love of God? From God. And what is the measure of this love? To love without measure,” and one has a key to his doctrine.

St. Bernard was declared a doctor of the church in 1830 and was extolled in 1953 as doctor mellifluus in an encyclical of Pius XII.

O God, by whose grace your servant Bernard, kindled with the flame of your love, became a burning and a shining light in your Church: Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline, and walk before you as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

#christianity#jesus#saints#monasticism#god#father troy beecham#troy beecham episcopal#father troy beecham episcopal

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is The Angelus?

Designed to commemorate the mystery of the Incarnation and pay homage to Mary’s role in salvation history, it has long been part of Catholic life. Around the world, three times every day, the faithful stop whatever they are doing and with the words “The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary” begin this simple yet beautiful prayer. But why do we say the Angelus at all, much less three times a day?

Most Church historians agree that the Angelus can be traced back to 11th-century Italy, where Franciscan monks said three Hail Marys during night prayers, at the last bell of the day. Over time, pastors encouraged their Catholic flocks to end each day in a similar fashion by saying three Hail Marys. In the villages, as in the monasteries, a bell was rung at the close of the day reminding the laity of this special prayer time. The evening devotional practice soon spread to other parts of Christendom, including England.

Toward the end of the 11th century, the Normans invaded and occupied England. In order to ensure control of the populace, the Normans rang a curfew bell at the end of each day reminding the locals to extinguish all fires, get off the streets and retire to their homes. While not intended to encourage prayer, this bell became associated nevertheless with evening prayer time, which included saying the Hail Mary. Once the curfew requirement ended, a bell continued to be rung at the close of each day and the term curfew bell was widely popular, although in some areas it was known as the “Ave” or the “Gabriel” bell.

Around 1323, the Bishop of Winchester, England, and future Archbishop of Canterbury, Bishop John de Stratford, encouraged those of his diocese to pray the Hail Mary in the evening, writing, “We exhort you every day, when you hear three short interrupted peals of the bell, at the beginning of the curfew (or, in places where you do not hear it, at vesper time or nightfall) you say with all possible devotion, kneeling wherever you may be, the Angelic Salutation three times at each peal, so as to say it nine times in all” (Publication of the Catholic Truth Society, 1895).

Meanwhile, around 1318 in Italy, Catholics began saying the Hail Mary upon rising in the morning. Likely this habit again came from the monks, who included the Hail Mary in the prayers they said before their workday began. The morning devotion spread, and evidence is found in England that in 1399 Archbishop Thomas Arundel ordered church bells be rung at sunrise throughout the country, and he asked the laity to recite five Our Fathers and seven Hail Marys every morning.

The noontime Angelus devotion seems to have derived from the long-standing practice of praying and meditating on Our Lord’s passion at midday each Friday. In 1456, Pope Calixtus III directed the ringing of church bells every day at noon and that Catholics pray three Hail Marys. The pope solicited the faithful to use the noonday prayers to pray for peace in the face of the 15th-century invasion of Europe by the Turks. The bell rung at noontime became known as the “Peace” bell or “Turkish” bell. In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV was petitioned by Queen Elizabeth of England, wife of King Henry VII, to grant indulgences for those who said at least one Hail Mary at 6 a.m., noon and 6 p.m. There is evidence that a bell was rung at those times.

The Angelus Today

By the end of the 16th century, the Angelus had become the prayer that we know today: three Hail Marys, with short verses in between (called versicles), ending with a prayer. It was first published in modern form in a catechism around 1560 in Venice. This devotion reminds us of the Angel Gabriel’s annunciation to Mary, Mary’s fiat, the Incarnation and Our Lord’s passion and resurrection. It is repeated as a holy invitation, calling us to prayer and meditation. For centuries the Angelus was always said while kneeling, but Pope Benedict XIV (r. 1740-1758) directed that the Angelus should be recited while standing on Saturday evening and all day on Sunday. He also directed that the Regina Coeli (Queen of Heaven) be said instead of the Angelus during the Easter season. Over the years many of the faithful have focused the morning Angelus on the Resurrection, the noon Angelus on the Passion and the evening Angelus on the Incarnation.

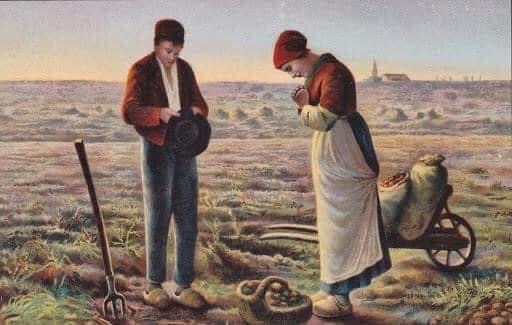

It is said that over the centuries workers in the fields halted their labors and prayed when they heard the Angelus bell. This pious practice is depicted by Jean-François Millet’s famous 1857 painting that shows two workers in a potato field stopping to say the Angelus. There are also stories that animals would automatically stop plowing and stand quietly at the bell.

Like a heavenly messenger, the Angelus calls us to interrupt his daily, earthly routines and turn to thoughts of God, of the Blessed Mother, and of eternity. As Pope Benedict XVI taught last year on the feast of the Annunciation: “The Angel’s proclamation was addressed to her; she accepted it, and when she responded from the depths of her heart … at that moment the eternal Word began to exist as a human being in time. From generation to generation the wonder evoked by this ineffable mystery never ceases.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

John Hunyadi’s great victory at Belgrade in 1456 breathed new life into the anti-Ottoman struggle. It effectively halted the Islamic advance into Europe for the next seventy years. News of the Ottoman defeat was hailed throughout the capitals of Europe. Pope Calixtus III, the first Borgia pope, praised the Hungarian leader, declaring Hunyadi an “Athlete of Christ,” comparing him to the great commanders of antiquity. #Hunyadi #Belgrade John Hunyadi and the Defense of Belgrade, 1456 draculachronicle.com/2018/08/20/joh… via @draculachron #Hunyadi #Belgrade #Hungary #1456 https://www.instagram.com/p/BnNyfcOAe5j/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=81rbx10ptsjs

1 note

·

View note

Quote

We see here the first clear manifestation of Alexander’s defining weakness as a man and as pontiff: his growing and soon all but unrestrained willingness to subordinate everything else to his favorites. No doubt he remembered how Calixtus III had turned to him and his brother under similar circumstances and had increased his effectiveness as pope by doing so. If the increasing extremes to which he carried his nepotism might to any extent be rationally explained, the explanation must surely have to do with the perception that Juan and his siblings, if empowered, could become Alexander’s most effective tools in the pursuit of his policy objectives.

G.J. Meyer - The Borgias

#rodrigo borgia#house borgia#auth: g.j. meyer#book: the borgias#one of the brief moments meyer actually concedes rodrigo had flaws??!#lmaoo#i have never seen anyone stan so much for rodrigo#istg#his love for him surpasses even mine and machiavelli (hehe) for cesare#tenfolds ok#it's funny

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Blessed Memorial of St Vincent Ferrer O.P. (1530-1419 aged 69) Religious Priest, Miracle-worker, Logician, Preacher, Missionary, Confessor, Teacher, Philosopher, Theologian known as the “Angel of the Apocalypse” and the “Mouthpiece of God” – Patron of brick makers, builders, Calamonaci, Italy, Casteltermini, Agrigento, Italy, construction workers, Leganes, Philippines, Orihuela-Alicante, Spain, diocese of, pavement workers, plumbers, . tile makers. Representation: Bible, cardinal’s hat, Dominican preacher with a flame on his hand, Dominican preacher with a flame on his head, Dominican holding an open book while preaching, Dominican with a cardinal’s hat, Dominican with a crucifix, Dominican with a trumpet nearby, often coming down from heaven, referring to his vision, Dominican with wings, referring to his vision as being an ‘angel of the apocalypse’, pulpit, representing his life as a preacher, flame, referring to his gifts from the Holy Spirit.

Vincent was the fourth child of the nobleman Guillem Ferrer, a notary who came from Palamós and wife, Constança Miquel, apparently from Valencia itself or Girona. Legends surround his birth. It was said that his father was told in a dream by a Dominican friar that his son would be famous throughout the world. His mother is said never to have experienced pain when she gave birth to him. He was named after St. Vincent Martyr, the patron saint of Valencia. He would fast on Wednesdays and Fridays and he loved the Passion of Christ very much. He would help the poor and distribute alms to them. He began his classical studies at the age of eight, his study of theology and philosophy at fourteen.

Four years later, at the age of nineteen, Ferrer entered the Order of Preachers, commonly called the Dominican Order, in England also known as Blackfriars. As soon as he had entered the novitiate of the Order, though, he experienced temptations urging him to leave. Even his parents pleaded with him to do so and become a secular priest. He prayed and practiced penance to overcome these trials. Thus he succeeded in completing the year of probation and advancing to his profession.

For a period of three years, he read solely Sacred Scripture and eventually committed it to memory. He published a treatise on Dialectic Suppositions after his solemn profession, and in 1379 was ordained a Catholic priest at Barcelona. He eventually became a Master of Sacred Theology and was commissioned by the Order to deliver lectures on philosophy. He was then sent to Barcelona and eventually to the University of Lleida, where he earned his doctorate in theology.

Vincent Ferrer is described as a man of medium height, with a lofty forehead and very distinct features. His hair was fair in colour and tonsured. His eyes were very dark and expressive; his manner gentle. Pale was his ordinary colour. His voice was strong and powerful, at times gentle, resonant and vibrant.

Three men claimed to be pope in the 1300s and 1400s. Kings, princes, priests, and laypeople fought one another to support the different claimants for the Chair of Peter. This chaos led to the Western Schism, and God raised up Vincent Ferrer.

When Vincent joined the Dominicans, he zealously practiced penance, study and prayer. He was a teacher of philosophy and a naturally gifted preacher called the “mouthpiece of God.” His saintly life was what made his preaching so effective. Vincent’s subjects were judgment, heaven, hell and the need for repentance.

Even the holiest people can be misled. Pope Urban VI was the real pope and lived in Rome but Vincent and many others thought that Clement VII and his successor Benedict XIII, who lived in Avignon, France, were the true popes. Vincent convinced kings, princes, clergy and almost all of Spain to give loyalty to them. After Clement VII died, Vincent tried to get both Benedict and the pope in Rome to abdicate so that a new election could be held. It hurt Vincent when Benedict refused.

Vincent came to see the error in Benedict’s claim to the papacy. Discouraged and ill, Vincent begged Christ to show him the truth. In a vision, he saw Jesus with Saint Dominic and Saint Francis, commanding him to “go through the world preaching Christ.” For the next 20 years, Vincent spread the Good News throughout Europe. He fasted, preached, worked miracles and drew many people to become faithful Christians. Vincent returned to Benedict in Avignon and asked him to resign. Benedict refused. One day while Benedict was presiding over an enormous assembly, Vincent, though close to death, mounted the pulpit and denounced him as the false pope. He encouraged everyone to be faithful to the one, true Catholic Church in Rome. Benedict fled, knowing his supporters had deserted him. Later, the Council of Constance met to end the Western Schism.

St Vincent always slept on the floor, he had the gift of tongues (he spoke only Spanish but all listeners understood him, he lived in an endless fast, celebrated Mass daily and known as a miracle worker; he is reported to have brought a murdered man back to life to prove the power of Christianity to the onlookers and he would heal people throughout a hospital just by praying in front of it. He worked so hard to build up the Church that he became the patron of people in building trades.

Because of the Spanish’s harsh methods of converting Jews at the time, the means which Vincent had at his disposal were either baptism or spoliation. He won them over by his preaching, estimated at 25,000. Vincent also attended the Disputation of Tortosa (1413–14), called by Avignon Pope Benedict XIII in an effort to convert Jews to Catholicism after a debate among scholars of both faiths.

Vincent died on 5 April 1419 at Vannes in Brittany, at the age of sixty-nine and was buried in Vannes Cathedral. He was canonised by Pope Calixtus III on 3 June 1455. His feast day is celebrated on 5 April. The Fraternity of Saint Vincent Ferrer, a pontifical religious institute founded in 1979, is named for him.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Duclos, The History of Lewis XI King of France, 1746

To understand well the different interest which Lewis XI and the pope took in this quarrel, it is necessary to recollect, that Alphonsus of Aragon had usurped the kingdom of Naples from Reignier of Anjou. After the death of Alphonsus, his natural son Ferdinand demanded the investiture of it from people Calixtus III, which his holiness refused, either with the view of restoring it to the house of Anjou, or of conferring it upon Peter Lewis Borgia his nephew, who was then prefect of Rome. He only declared by a bull, that the kingdom of Naples, which the popes had disposed of as sovereign lords, was devolved to the church by the death of Alphonsus. Callouts II dying within six weeks after Alphonsus, Pius II gave the investiture of the kingdom of Naples to Ferdinand, whose daughter was married to Anthony Piccolomini, this pope’s nephew. The house of Anjou, however, had a powerful party in Naples. John duke of Calabria, the son of King Reignier, and cousin-German to Lewis XI, judging the circumstance favorable, set out from Genoa, where he had commanded for three years on the part of France, advanced towards Naples, and gained the battle of Sarno. Ferdinand was reduced to the last extremity, and the duke of Calabria was upon the point of being master of Naples, when the pope implored the assistance of Scanderberg, king of Albania, in favor of Ferdinand.

0 notes

Quote

As a native of Spain, Pope Calixtus carried with him the ancestral Iberian obsession with the Muslim threat, something that had been part of the peninsula’s culture since 711. He had been deeply disturbed by the fall of Constantinople in 1453, two years before his election, and he avidly listened to reports of subsequent events in eastern Europe. “He ascended the Papal throne,” Fusero writes, “with one great and all devouring project in mind—to free Christian Europe from the Turkish scimitar which, more especially since the occupation of Constantinople, had been pointed at her throat. All his efforts, all his thoughts, all his political activities converged on this one end.” Very few European Christian rulers shared his intense concern. Preoccupied with their own territorial rivalries, the Europeans had done little to prevent the conquest of Constantinople, and their subsequent efforts against the Muslims were halfhearted and ineffectual. This state of affairs made the cities of Europe seem easy pickings to the Turks; their wealth and women seemed available to anyone with the pluck and determination to take them. In the 1450s, in the wake of his victory, Mehmed II began calling himself Caesar and styling himself the emperor of Rome, leading an army three hundred thousand strong and preparing once more for attack. Pope Calixtus issued a clarion call for funds and troops to fight the Turks, but the response was tepid. The threat seemed too distant, too ephemeral, particularly for northern Europeans and for the warring northern Italian city-states. Pope Calixtus resolved to defend Christianity on his own. To raise money, he introduced an austerity program at the Vatican, a reversal of course after the free-spending ways of Pope Nicholas. Calixtus ordered gold and silver plate from the papal treasury to be melted to raise money for armaments. When a marble tomb was unearthed and found to contain two mummified corpses dressed in robes of gold-woven study them, but to sell them for the value of the gold they contained. Calixtus also drummed up support by encouraging public admiration for religious warriors. He was the prelate who had pressed for the reexamination of Joan of Arc’s life, which recast her as a God-fearing soldier of liberation against an invading force. Her legend grew as that taint of heresy dropped away. As a result of this review of her case, which happened when Isabella was six, Joan of Arc was declared innocent, rehabilitated, and placed on the path toward sainthood. “Only on the battlefield does the palm of glory grow,” Pope Calixtus once said. His preoccupation with Christian self-defense intensified as reports from eastern Europe grew more alarming. Turkish troops were headed for Hungary and up the Danube River. In 1456 Turkish troops engulfed Athens; recognizing that no assistance was at hand, its residents opted to survived and were allowed to follow their own religious traditions. But the people who had coined the term democracy were labeled rayah or slaves by the Ottomans. During Calixtus’s pontificate, and using the funds he had stockpiled, the pope engaged in the strongest counterattack organized by the Christian world to that time. the Greek Isles. Elsewhere the city of Belgrade, besieged by the Ottomans, succeeded in holding them off. But Calixtus was eighty years old, and he had been selected for the papacy because of his declining health. In the summer of 1458, when Isabella was seven, he grew ill and was reported to be dying.

Isabella: The Warrior Queen by Kirstin Downey

0 notes

Text

The Search for Prester John

Visit Now - http://zeroviral.com/the-search-for-prester-john/

The Search for Prester John

The history of Prester John is the history of a man who never existed. Medieval legend called him into being when it was felt that his presence would be of help in the struggle between Christian Europe and the Islamic world. His name was first recorded in 1145 and continued to appear from time to time up to the beginning of the 17th century. Each reference to Prester John – John the Priest – was compounded of two elements; on one side the European wish for the existence of a strong Christian power beyond the confines of Medieval Christendom; on the other, some historical event or process in a far corner of the earth, on the distorted news of which was based a concrete shape for this wish.

Originally the Priest King was heard of in Asia; later it became generally accepted that his kingdom lay in Africa. With the growth of geographical knowledge and the discovery of places in which Prester John was not to be found, the location of the Priest King moved to lesser known regions. The development of the legend makes a fascinating study; not only for the sake of its wealth of fabulous detail, but also because the belief in the existence of Prester John had a profound effect on the history of European exploration and discovery in Asia and Africa.

*

Many elements in the corpus of medieval mythology played their part in paving the way for the appearance of the Priest King. The legends of the exploits in Asia of Alexander the Great contained many details of the wonders which could be expected in the Orient. The associated story of Gog and Magog and of the wall which Alexander built to prevent these malevolent people from devastating the civilised world gave strength to the idea that the safety of Christendom might depend upon some force outside its borders.

The story of the Magi, the three wise Kings of the East who brought gifts to the infant Jesus, suggested that there might be as yet undiscovered Eastern rulers who were true friends to the Christian faith. The Jewish belief in the existence of the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel in some part of furthest Asia, perhaps beyond the wall of Gog and Magog, strengthened this concept of salvation from without by its implication that the long-awaited Jewish Messiah might arise from among these excluded tribes. Finally, there was the fact of the early spread of Christianity to remote corners of Asia which had given rise to legends concerning the missions of the Apostle St. Thomas to India and China.

The Christian communities of the Far East, though generally schismatic or heretical, never lost touch with the Christians of Europe. The Holy Land provided a meeting place for Christians from all over the world. On occasions representatives of remote churches found their way to Rome. It is probable that such a visit, that of the Patriarch John of the Indian Church of St. Thomas to Rome in about 1122, might have provided the immediate basis of the legend of Prester John, the Christian Priest King in the East.

Patriarch John did his best to impress his Roman brothers in Christ. He told such fabulous tales that Pope Calixtus II is said to have asked him to keep silent, and only permitted him to continue his account when the good Patriarch took an oath on the Gospels that all he said was true. He told of his wonderful capital, Ulna, so vast in area that it took four days to walk round its walls. He described the Phison, one of the rivers of Paradise, which watered his land. He gave an account of the miraculous body of St. Thomas which lay preserved at Ulna and was the chief glory of his see. He gave the impression that he was the temporal as well as the spiritual ruler of this Indian state. He might well have suggested that he could be a most valuable ally to Christendom in time of need.

In 1145, when the Prester first appears, need for such an ally was all too apparent. The capture of Edessa by the Seljuk general Zengi in 1144 marked the turning-point in the history of the Crusades. The conquests of the First Crusade were gravely endangered by a revival of Islamic power. The news of the fall of Edessa was brought to Pope Eugenius III from the Levant by Hugh, Bishop of Jabala in Syria. The meeting between Bishop and Pope, at Viterbo in the autumn of 1145, was attended by the German chronicler Otto of Freisingen, who took down what was said.

To the Bishop the gloomy news of the fall of Edessa was balanced by the prospect of help for the Crusaders from an unsuspected direction. The Bishop had heard that not long ago ‘one John, king and priest, who dwells in the extreme Orient beyond Persia and Armenia, and is with his people a Christian, but a Nestorian,’ had defeated the Persians and captured their capital. After this victory John set out with his army to come to the aid of the Crusaders, but was unable to get his troops across the Tigris.

He marched north up the river in hopes of finding a place where the water froze over in winter. In this he was disappointed and after waiting some time for a frost which never came, and losing many of his men owing to the unfavourable climate, he was obliged to turn homewards.

This Prester John, the Bishop concluded,

was said to be of the ancient race of those Magi who were mentioned in the Gospel, and to rule the same nations as they did, and to have such glory and wealth that he used only an emerald sceptre. It was from his being fired by the example of his fathers, who came to adore Christ in his cradle, that he was proposing to go to Jerusalem when he was prevented by the cause already alleged.

There is a certain basis of contemporary fact behind this odd story. In 1141 the Seljuk Sultan Sinjar, in one of the decisive battles in the history of Central Asia, was defeated at Katwan near Samarkand by a Mongol people, the Kara Kitai, who had recently migrated to Central Asia from their previous home in north China. The Kara, or ‘black’ Kitai were a branch of the Kitans who had ruled over north China from 936 until 1122, when they had been dispossessed by another Mongolian group, the Kin.

One branch remained under Kin domination; another branch set out on a migration which, in a few years, brought it to the borders of the Seljuk empire. It is from the name of these people, the Kitai, that the name which Marco Polo gave to China, Cathay, is derived. Their defeat of Sinjar marked the end of Seljuk expansion and, in the Levant, paved the way for the rise of Saladin. To the Crusaders of the time, however, it must have seemed as if some unknown ally was fighting on their side against their chief enemy, the Seljuks.

The Prester John of this story is the Emperor of the Kara Kitai, the Gurkhan, Yeliu Tashi by name. Yeliu Tashi was certainly no Christian; if anything, he was Buddhist. Attempts have been made to derive the name John from the title Gurkhan; but there is no need for this. To the Bishop it sufficed that the victor over the Seljuks was no Muslim. The name John probably came from a memory of the visit of the Patriarch John of India to Rome in 1122.

*

The victories of Prester John failed to relieve the position of the Crusaders. His armies did not appear. Without him the Second Crusade ended miserably. But the Priest King’s failure to bring succour to his co-religionists did not weaken their faith in his existence. Any lingering doubts, moreover, must have been dispelled in 1165, when the Byzantine Emperor Manuel Comnenos, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and the Pope all received a letter from the fabulous Prester John.

The letter was a forgery. It may have been intended as a tract on the benefits of priestly government and hence as a useful support to the Papacy in relation to the Empire. It may have been devised as propaganda for a Third Crusade. It enjoyed a very wide circulation and its popularity was such that it continued to be copied, with frequent topical interpolations, throughout the rest of the Middle Ages. More than one hundred manuscript copies of the letter, in several languages, are known to exist.

The bulk of the letter was devoted to describing the magnificence of the Kingdom of Prester John, with a wealth of detail derived from such diverse sources as the various Alexander legends and the story of the city of the Apostle Thomas which Patriarch John told the Pope in 1122. The location of the Prester’s kingdom was in India. He worshipped at the Church of St. Thomas. He informed the leaders of Europe that ‘We have determined to visit the sepulchre of our Lord with a very large army, in accordance with the glory of our majesty, to humble and chastise the enemies of the cross of Christ and to exalt His blessed name.’

In 1177 Pope Alexander III replied with a long letter to Prester John. The immediate occasion for this was a meeting by the Pope’s doctor, one Philip, with some representative of the Priest King while on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. According to Philip, Prester John, a Nestorian, wished to embrace the Roman faith and to build a church in Rome and an altar in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. When the Pope heard this, he promptly sent Philip as bearer of a friendly letter to the Prester. Where Philip went, and what became of the letter, is not recorded. It is possible that Philip had met in Jerusalem pilgrims from one of the remoter Christian communities of Central Asia and interpreted what they told him in the light of his preconceptions about Prester John.

Doubtless, the Pope, who had just emerged victorious from a long struggle with Frederick Barbarossa, saw no harm in letting it be known that he had established relations with this fabulous Christian power of the East. The episode certainly received much publicity; various versions of the Pope’s letter are given in several English chronicles of the 13th century.

*

When news of Prester John next emerged from the East, in about 1221, the need for outside assistance for the Crusaders was even greater than it had been in 1145. In 1187 Jerusalem fell to Saladin. The Third Crusade, in which Richard Coeur de Lion won such fame, failed to recapture the Holy City.

The Fourth Crusade, instead of bringing help to Palestine, sacked the Christian city of Constantinople and seriously weakened the remaining vigour of the Byzantine Empire. The Children’s Crusade of 1212 ended in tragedy. The army of the Fifth Crusade, which landed in Egypt in 1218, sorely needed some deus ex machina to bring to it greater success than that met with by its predecessors. Hope for such help was suggested in the letter which Jacques de Vitry, Bishop of Ptolemais, wrote to Pope Honorius III in 1221. He reported that David, King of India and descendant of Prester John, had attacked the infidel with three armies, and that one of these armies was at that moment within fifteen days march of Antioch. Here at last, he wrote, was the long-awaited ‘Hammer of the Infidel.’

There is little difficulty in detecting the Central Asian origin of this story. In 1218 the Mongols, under Chinggis Khan, overthrew the Kara Kitai Empire which had in about 1211 passed under the control of an adventurer of the Naiman tribe of Mongols. By 1220 Chinggis Khan had gone on to destroy the Empire of Kwarezm, a powerful Islamic state which had been founded towards the end of the 12th century in the land between the Rivers Oxus and Jaxartes, and which extended its influence over much of Persia. In 1221 a flying column of Mongol troops dashed into Persia, nearly captured Baghdad, and penetrated far into the Caucasus. David, of the line of Prester John, could only be Chinggis Khan.

Today, the picture of Chinggis Khan in the role of saviour of Christendom seems absurd. In the early 13th century it seemed reasonable enough. It was well known that several nomadic tribes in Central Asia had embraced Christianity. Even if the Mongol Khans were not of the faith, this was no reason why they should not be converted into genuine Prester Johns.

Pope Innocent IV, who was elected in 1243, certainly thought along these lines. He had been told that ‘the Mongols worship one God, and were not without some religious beliefs.’ The Mongols, moreover, ‘say they have Saint John the Baptist for Chief.’ So reported a Russian Bishop who had fled to France to escape the advancing Mongol hordes. Innocent resolved to try to establish some sort of relations with the Mongols.

In 1245 Friar John of Plano Carpini was sent by the Pope to carry letters to the Mongol Khan, and there can be little doubt that among his instructions was a request to clear up the mystery of Prester John. His conclusion was that the Mongols were not the people of the Priest King; but his information about who Prester John was is not so definite and varies according to different versions of the narrative which he wrote on his return from his mission.

Carpini made a passing reference to the Black Cathayans, who, he claimed, were Christian in all but name. They had recently been conquered by the Mongols. But the Prester was not among these people; he had moved to the adjacent land of India Major, if one is permitted to interpret ‘the black Saracens who are also called Ethiopians’ as a reference to the Black, or Kara, Kitai. In the 13th century, it is worth noting, the term Ethiopia was so imprecise as not to justify its location in Africa without supporting evidence which, in this case, is not present.

Prester John, Carpini wrote, lived beside these ‘black Saracens.’ Chinggis Khan tried to invade his land but was repelled by the Prester, who sent against the invading troops what sounds very much like explosive charges fastened to the backs of horses and set off at the right moment by suicide soldiers. But another version of Carpini’s account told a different story.

Prester John and his son David were described as kings of India to whom the Mongols used to pay tribute. Chinggis Khan, however, put an end to this practice by invading the land of Prester John and defeating King David. The victorious Prester is in the tradition of the stories of 1145 and 1221; the defeated Prester fits in with the travellers’ tales of the second half of the 13th century.

*

Just as the Pope was interested in finding Christian allies in the East, so was the Crusading French King, Louis IX. Louis had met Carpini after his return, and had talked with other envoys whom the Pope had sent to various Mongol Khans.

In 1253, after his unfortunate Egyptian Crusade, Louis sent his own envoy to the Mongols, Friar William of Rubruck, and once more it is most probable that the ambassador to the Mongols was instructed to keep on the look-out for traces of Prester John. These Rubruck had no difficulty in finding, but they were hardly of the type which Louis would have hoped for.

This was Rubruck’s story: in about 1098 there lived in Central Asia a certain Con Khan, chief of the Black Cathayans. When Con died the Black Cathayans came under the rule of a certain Naiman chief, a Nestorian Christian known as John. John had a brother, Unc, who ruled over the Kerait people in the neighbourhood of Karakorum, the Mongol capital.

The Keraits were also Nestorians, but Unc abandoned the religion of his people and became an idolater. When King John died, Unc combined the rule of the Black Cathayans with that of the Kerait. With this increase in power Unc’s ambition became boundless and soon he attacked the neighbouring tribe of the Mongols and defeated it.

Aroused by this disaster, the Mongols made Chinggis Khan their leader, and under his guidance soon avenged their defeat by overwhelming in battle the forces of Unc and forcing him to take refuge in Cathay. As in the other Prester John stories to this date, Rubruck’s story is not without historical foundation. Con Khan is clearly the Gurkhan of the Kara Kitai. In about 1211 this position was usurped by the Naiman adventurer Kutchluk, who is clearly the model for Rubruck’s King John, though there is no evidence that Kutchluk or the Naiman were Christians at the time.

Unc is as easily identified. He is Toghrul, chief of the Kerait tribe. Toghrul had at one time been the patron of the young Chinggis, and had later become his enemy. The defeat of Toghrul by Chinggis in 1203 marked the virtual completion of Chinggis’ unification of the tribes of Mongolia.

A close examination of the Kara Kitai, such as Rubruck was in a position to make, showed that neither were they any longer a power worthy of notice nor had they ever been Christians. The Keraits, while their political importance had greatly declined after the defeat of Toghrul, were still the most important Christian tribe in Central Asia.

The conversion of the Keraits took place in about 1009 in miraculous circumstances which were widely reported at the time. The King of the Keraits, so the story went, lost his way when out hunting. A blizzard overtook him and he was convinced his hour had come, when a Saint came to him in a vision and said: ‘If you believe in Christ, I will lead you in the right direction and you will not die here.’

The King got home safely. He remembered the vision and embraced the Christian faith along with his tribe, some 200,000 souls. The Keraits were clearly well suited for the role of the people of Prester John. It is probable that the story of their conversion played its part in the development of the legend. Rubruck’s narrative paves the way for the transfer of the title of Prester John from the Kara Kitai to the Keraits.

*

By the time Marco Polo set out on his travels the identification of Prester John with the ruler of the Keraits had become generally accepted. Polo’s account of the Prester, while similar to that of Rubruck, makes no further mention of the Kara Kitai. Like Rubruck, Marco Polo is not greatly impressed with the Prester’s sanctity. He attributes the defeat of Prester John by Chinggis in great part to the Priest King’s pride and lack of tact in dealing with the Mongols.

When Chinggis sends ambassadors to John to seek the Prester’s daughter as a wife for the Mongol ruler, he receives an insulting reply. War follows in which Prester John is defeated and killed. On the eve of the battle Christian astrologers prophesy that Chinggis will win and Genghis is so pleased with this correct prediction that from that day he always treats Christians ‘with great respect’ and considers them to be ‘men of truth for ever after.’

The general trend of the Prester John legend in the 13th century was towards a discrediting of the Priest King in favour of the Mongols, his conquerors, on whose shoulders, it seemed, had fallen the mantle of the saviours of Christendom. There was some basis to this concept. Several important Mongol officials were Christian; and several of the clans which had united under the banner of Chinggis Khan were of this faith.

When, in the years after 1239, it seemed as if the Mongols, who had conquered Russia, Persia, parts of Asia Minor and the Levant, and had penetrated for a brief moment into Poland and Hungary, were destined to play a dominant part in European politics, the idea of a Christian Mongol Empire became most attractive. The value of a Mongol alliance was evident. A Byzantine Emperor did not shrink from giving his daughter in marriage to a Khan of the Mongol Golden Horde in Russia. Frankish princes in the Levant gladly allied themselves to Hulagu.

This Mongol satrap, grandson of Chinggis Khan, destroyer of the Abbasid Caliphate, and founder of the Khan dynasty of Persia, played a part in the Levant in the second half of the 13th century not unlike that which it had been hoped at one time Prester John would play. For a while it seemed as if Hulagu would crush the power of Egypt, whose leader, Baibars, was then the mainstay of Islamic power in the Levant. It even seemed possible that Hulagu would become a Christian; his wife was already of that faith.

In these circumstances Prester John dwindled in importance. Marco Polo found a person whom he considered to be descended from Prester John, George, who still ruled in the province of Tenduc, in the great loop of the Yellow River, where Polo had located the Priest’s realm. George’s family married into that of the Great Khan. He still held land, but only as a Mongol feudatory, and he did not hold ‘anything like the whole of what Prester John once possessed.’ It was clear that the Asiatic Prester John had had his day.

*

By the beginning of the 14th century the idea of help for Christendom from the Orient had suffered rude disillusionment. The followers of Hulagu, of whom so much had once been hoped, embraced Islam as did the Mongols in Russia. The centre of Crusading interest, moreover, had been shifting from the Levant to Egypt and North Africa. It became fixed when Acre, the last Frankish stronghold on the Levant mainland, fell to the Saracens in 1291. The next phase of the Crusade was to be the preparation for Portuguese expansion on to the coast of North Africa.

It was inevitable that the search for Prester John should be shifted to Africa. By the early 14th century his kingdom was being located in Abyssinia, where a Christian community had been in existence since the fourth century. Contact between Abyssinia and Europe had been severed by the Islamic conquests of the seventh century; but at the very moment when the Asiatic Prester John was being discredited by travellers like Friar Odoric, Abyssinian embassies began to reach the Courts of Europe and Dominican missionaries were able to penetrate into Central Africa. By the end of the 14th century few writers in Europe would have denied that Prester John was the ruler of Abyssinia.

Here, it was argued, he had retired when the Mongols had defeated him in Central Asia. And here he was still able to render valuable assistance to Christendom against the power of Islam in the Mediterranean. In his kingdom lay the source of the River Nile upon which the life of the most formidable Muslim power, Egypt, depended, and he had but to divert the course of this river to starve the Egyptians into submission.

That Prester John had not already done so, some writers argued, was solely because the Priest King did not wish to have on his conscience the lives of the many Christians who lived in the Nile Delta. Other observers, less charitably, wrote that the Prester was dissuaded by a large Egyptian subsidy.