#postsurgery taylor

Text

If post-surgery Taylor saw that, she would get MAD

@taylorswift @taylornation

#postsurgery taylor#banana#taylor nation#taylorswift#taylor swift#taylornation#taylor needs to see this#taylor notice this#taylor notice me#taylor edit#edit#taylor swift edit#edits#my edits#taylor edits

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Post-surgery Taylor Swift freaks out over a banana Pup sensation Taylor Swift was in for a surprise when after the operation she showed a video of herself in The Tonight Show with the show Jimmy Fallon.

0 notes

Text

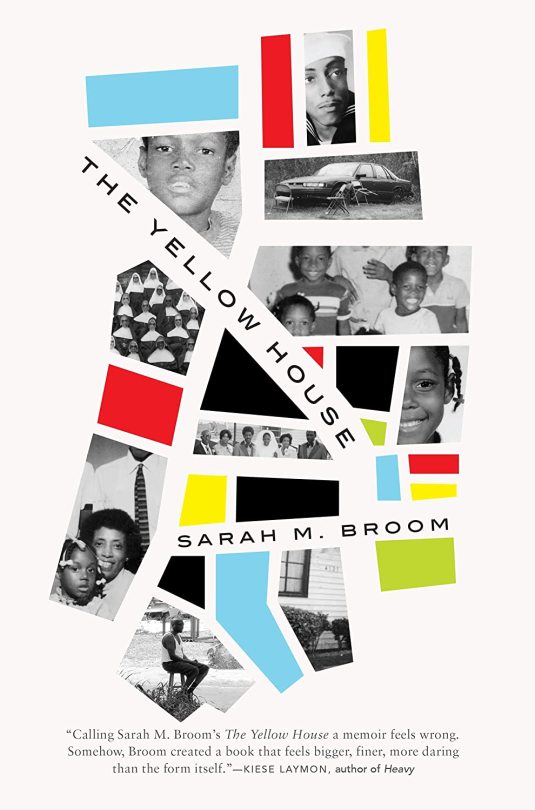

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom

Lolo always told us we could be whatever we wanted to be. When we were growing up, we never thought of white people as superior to us. We always thought we were equal to them or better.

But Joseph, Elaine, and Ivory had only to walk to the curb outside their Roman Street house to see Taylor Park and its sign: NO NIGGERS, NO CHINESE AND NO DOGS. It was a strange sight, the mostly empty, fenced-in park in a black neighborhood. If the neighborhood children wanted a park to run around in or a pool for swimming, they had to travel to Freret Street’s Shakespeare Park, several miles away. “It seemed most of the black people in New Orleans had to go over there,” Uncle Joe said. Getting to Shakespeare Park required a ride on segregated buses.

But there was an added complication in New Orleans, a city fixated on and obsessed with gradations of skin color. My mother, Ivory Mae, understood from a young age the value in her light skin and freckles and in the texture of her wavy hair, which she called good. The favoritism came through in the double-standard ways of all prejudice, in the way people lit up when they saw Ivory but did not come alive so much for Elaine, who wondered why she was a few shades darker than Joseph and Ivory and with thicker hair that she herself described as “a pain to comb.”

As a child, my mother internalized this colorism, the effects of which sometimes showed in shocking ways.

One day Ivory, Elaine, and Grandmother’s sister Lillie Mae were sitting together on the Roman Street stoop watching people. Mom was eight years old. A schoolmate, whom Mom called Black Andrew, walked by. He was headed to Johnny’s Grocery store. This was not unusual. Andrew passed two, three, sometimes four times a day, whenever he raised a nickel or a couple of pennies for candy. When he went by he stared, sometimes winking at Ivory Mae, who glared back from the porch. She was always taunting: Black Andrew, hey lil black boy. The neighborhood children on their respective porches urged her on without needing to. That lil black boy ain’t none of my boyfriend she remembers telling them.

He never did look like he was clean. I mean he was really a little black boy, nappy and everything. She meant that he was dark skinned, the color of her own mother, the color of her mother’s sister Lillie Mae, who was sitting right beside her.

“You have cheeks to call that boy black?” said Lillie Mae. “Look at your ma. What color is she?”

My mama not black, small Ivory Mae had said then.

She wasn’t black to me. She was my mama and my mama wasn’t black. Looked to me like they was trying to make my mama like the black people I didn’t like.

“I guess we saw it sort of like the white men saw it,” says Uncle Joe now, trying to explain his baby sister. “As people being lower than us.” (pp. 28-29)

***

Remembering is a chair that it is hard to sit still in. (p. 223)

***

My mother, Ivory Mae, called me one day in Harlem and told me the story in three lines:

Carl said those people then came and tore our house down.

That land clean as a whistle now.

Look like nothing was ever there.

The letter from the city announcing the intended demolition, the planned removal of 4121 Wilson, had been sent to the mailbox in front of the exact same house set to be torn down, its pieces deconstructed and carted away.

The Yellow House was deemed in “imminent danger of collapse,” one of 1,975 houses to appear on the Red Danger List, houses bearing bright-red stickers no larger than a small hand.

The notice in the mailbox in front of our doomed house read in part: Dear Ms. Bloom: The City of New Orleans intends to demolish and remove the home/property and/or remnants of the home/property located at 4121 Wilson ... THIS IS THE ONLY NOTIFICATION YOU WILL RECEIVE. Sincerely, Law Department-Demolition Task Force.

Not one of us twelve children who belonged to the house—not Eddie, Michael, or Darryl; nor Simon, Valeria, or Deborah; nor Karen, Carl, Troy, Byron, Lynette, or myself—was there to see it go.

Look like nothing was ever there.

Before our house was knocked down, Carl had overseen its ruins, driving by almost daily, except for the day when he suddenly fell sick in the driveway of Grandmother’s house where he was living. One minute he was revving his engine for the drive to NASA in New Orleans East, the next, his head lay down on the steering wheel. A neighbor saw this, a busy man’s head down, and became alarmed. Carl was rushed to the hospital for surgery. “Crooked intestines,” was how Carl interpreted the doctor's diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. “They had to chop a large section of me out. I was all twisted inside from all that bad water I was swimming in,” Carl was convinced.

He stayed in the hospital an additional thirty days postsurgery after incurring an infection from the hospitalization itself. This was how it came to be that he missed the letter in the mailbox and the house was demolished without our knowing it.

Everyone else was still displaced. The only one to see our house go was Rachelle—Herman and Alvin's sister, Ms. Octavia's granddaughter who we called Ray. She was the inheritor of the last remaining house standing on the street. Ray snapped Polaroid images of the Yellow House's demise, instant evidence that she misplaced and could not find when we came back around, months after the fact, asking, “Did you see it? Did you see the house go down, Ray? Did you see?”

Perhaps there is a trick of logic that fails me now, but to deliver such notification to the doomed structure itself seems too easy a metaphor for much of what New Orleans represents: blatant backwardness about the things that count. For what can an abandoned house receive, by way of notification? And when basic services like sanitation and clean water were still lacking, why was there still mail delivery? But we were not the only ones. Lawsuits were filed against the city on behalf of houses that unlike ours stood in perfect condition when they were knocked down. There were sanctuaries, actual churches that deacons prepared to move back into, only to discover them gone. A newspaper article headlined NEW ORLEANS' WRECKING BALL LEVELS HEALTHY HOMES asked the simplest and thus most profound questions, such as: “How do you not inquire before you knock a place down? How do you not knock on the door first?”

During a later trip to New Orleans, I retrieved the file from city hall that told the story of the demolition. I carried it around in my purse and wrote “Autopsy of the House” in large letters on the front page. The cover letter held the following disclaimer: “The subject property was not historical in nature.” The report tells this story: The house was displaced from its foundation. Structural displacement was moderate as opposed to severe, which would have required that the house float down the block and settle in another locale entirely. City inspectors deemed the house “unsafe to enter.” There was asbestos everywhere, in the living room walls, in the trowel-and-drag ceilings that Uncle Joe had painted, in the asphalt shingles, in the vinyl sheeting on the floor. City inspectors noted that the left wall framing was severely "racked."

I called on an engineer friend and described the house, told her I was trying to learn from reading the autopsy which of the structural problems were waterborne and which were just the dilapidated house. An engineer would not use the word “dilapidated” to describe the house in its post-Water state, she told me. Dilapidated is a judgment. From an engineering perspective, she explained, the house was stable after the hurricane. It just wasn't contained. All the cracks happened so that the house could resolve internally all its pressures and stresses.

Water entered New Orleans East before anyplace else. On August 29, 2005, around four in the morning, water rose in the Industrial Canal, seeped through structurally compromised gates, flowed into neighborhoods on both sides of the High Rise. But that was minor compared with what would come two hours later when a surge developed in the Intracoastal Waterway, creating a funnel, the pressure of which overtopped eastern levees, destroying them like molehills. Water rushed in from in the direction of Almonaster Avenue, over the train tracks, over the Old Road where I learned to drive, through the junkyard that used to be Oak Haven trailer park, and into the alleyway behind the Yellow House, which may have served as a speed bump. The water pushed out the walls that faced the yard between our house and Ms. Octavia’s. The standing water that remained inside caused the sheetrock to swell. Water will find a way into anything, even into a stone if you give it enough time. In our case, the water found a way out through the split in the girls’ room.

“Water has a perfect memory,” Toni Morrison has said, “and is forever trying to get back to where it was.”

The foundation of the Yellow House was sill on piers, beams supported by freestanding brick piles. Not an uncommon way of building in Louisiana, this foundation did not stand a chance against serious winds and serious flooding. The autopsy report testifies that our sill plate was severely damaged, that the connection was “pried or rotated.” It could be said, too, my engineer friend told me, speaking more metaphorically than she was comfortable with, that the house was not tethered to its foundation, that what held the house to its foundation of sill on piers, wood on bricks, was the weight of us all in the house, the weight of the house itself, the weight of our things in the house. This is the only explanation I want to accept.

The only structure that was stable at the time of demolition was the incomplete add-on that my father had built.The house contained all of my frustrations and many of my aspirations, the hopes that it would one day shine again like it did in the world before me. The house’s disappearance from the landscape was not different from my father’s absence. His was a sudden erasure for my mother and siblings, a prolonged and present absence for me, an intriguing story with an ever-expanding middle that never drew to a close. The house held my father inside of it, preserved; it bore his traces. As long as the house stood, containing these remnants, my father was not yet gone. And then suddenly, he was.

I had no home. Mine had fallen all the way down. I understood, then, that the place I never wanted to claim had, in fact, been containing me. We own what belongs to us whether we claim it or not. When the house fell down, it can be said, something in me opened up. Cracks help a house resolve internally its pressures and stresses, my engineer friend had said. Houses provide a frame that bears us up. Without that physical structure, we are the house that bears itself up. I was now the house. (pp. 228-32)

3 notes

·

View notes