#prairie ecology

Photo

Kansas Research Shows Reintroducing Bison on Tallgrass Prairie Doubles Plant Diversity

Findings from decades of data also point to resistance to extreme drought.

Decades of research led by scientists at Kansas State University offered evidence reintroducing bison to roam the tallgrass prairie gradually doubled plant diversity and improved resilience to extreme drought.

Gains documented in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science were among the largest recorded globally in terms of species richness on grazing grasslands. The research involved more than 30 years of data collected at the Konza Prairie Biological Station near Manhattan.

Zak Ratajczak, lead researcher and assistant professor of biology at Kansas State, said removal of nearly all bison from the prairie occurred before establishment of quantitative records. That meant effects of removing the dominant grazer were largely unknown, he said.

“Bison were an integral part of North American grasslands before they were abruptly removed from over 99% of the Great Plains,” Ratajczak said...

Read more: https://www.agriculture.com/news/business/kansas-research-shows-reintroducing-bison-on-tallgrass-prairie-doubles-plant-diversity

#bison#prairie#ecology#prairie ecology#grasslands#nature#science#ungulate#grazing#animals#north america#biodiversity#environment#conservation#restoration ecology#range ecology

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#poll#great lakes#ecosystems#ecology#marsh#lake#lakeposting#freshwater#wetlands#fen#bog#cattail#wild rice#forest#boreal#boreal forest#prairie#dune#dunes#dune and swale#estuary#delta#wet meadow#swamp

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The greater sage grouse, which once numbered in the thousands in Western Canada, is coming perilously close to vanishing from the Prairies, new government research shows.

Known for its unusual mating dance, the species — found in areas where sagebrush grows — has been endangered for decades.

The round-bodied bird is among the species most at risk in Canada. The latest data from government conservationists provides little hope for their future.

Continue Reading.

#Science#Animals#Enviroment#Biology#Ecology#Conservation#Birds#Greater Sage Grouse#Canada#Canadian Prairies

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

#grasslands#prairie#savannna#ecology meme#funny#haha#science#ecology#biomes#environment#earth#planet earth#boreal forest#god i fucking LOVE grasslands they're so good

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I am still decompressing from four days of driving, but I am intensely pleased that I got to spend a few hours walking the full six-mile loop at Konza Prairie Biological Station in the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas. I've been to plenty of old-growth forests, but this was my first time getting to explore an old-growth tallgrass prairie, and the oak groves that often form in low-lying areas. It was saved from being plowed under by all the dolomite stone just under the soil which made agriculture too difficult, other than cattle grazing. After driving for hours through cornfields and pastures full of non-native pasture grasses, it was such a relief to be able to immerse myself in a place that looks much like this entire landscape did for thousands of years. I know they're still doing restoration work there, since fire suppression has caused some imbalances, and of course the extermination of bison, but it's one of the best examples of North American tallgrass prairie still available today.

I have a lot more thoughts ruminating about this experience, but for now, enjoy a few pictures.

#Konza Prairie#tallgrass prairie#tallgrass#native ecosystems#old growth#prairie#grasslands#ecology#restoration ecology#Kansas#Midwest#North America#grass#grasses#nature#nature photography#travel

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

American bison (Bison bison)

#can you guys tell bison are my fave animal#mine#bison#hoofstock#animals#wildlife#prairie#buffalo#american bison#nature#naturalist#nature photography#photography#mammals#ecology#north america#north american wildlife#conservation#ecologist#biologist#wildlife biology#wildlife biologist#biology#national parks#badlands#badlands national park#national park

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It is simply impossible to overstate both the importance of the buffalo to the Indian people and the damage that was done when the buffalo were nearly wiped out,” ITBC President Ervin Carlson said in a statement. “By helping tribes reestablish buffalo herds on our reservation lands, the Congress will help us reconnect with a keystone of our historic culture as well as create jobs and an important source of protein that our people truly need.”

#bison#buffalo#short grass prairie#conservation#sustainability#economic development#traditional ecological knowledge#ecological restoration#species conservation

213 notes

·

View notes

Link

When bison were allowed to graze through patches of tallgrass prairie, they boosted native plant species richness by a whopping 86 percent over the past three decades, according to a study published August 29 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Areas grazed by cattle also benefited native species, though they increased by just 30 percent. American bison, also called buffalo, provided nearly three times the environmental benefit as cows, and researchers aren’t yet sure why.

“We’re still kind of surprised at just how large of an effect bison had,” says study leader Zak Ratajczak, an ecologist at Kansas State University. “I don’t think anyone would have predicted this ahead of time.”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer 2023 on a wet prairie in the Ozarks.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 October 2023 - Friday Field Notes

Fall is here. The days are getting shorter and the nights are getting colder. Got to spend some time at one of the other offices this week. All the leaves are starting to change and I haven't seen this little lady in a while.

This bullsnake is an education animal, not a pet. I know they're cute, but wildlife needs to stay wild and should not be kept as pets.

These tansy asters are some of the late blooms you'll find on the prairie. Many native flowering plants have staggered bloom cycles, some flowering plants bloom as early as Apri, if conditions are favorable, while others species bloom as late as October or November. In biodiverse rich ecosystems, you should be able to see flowers throughout the season at different times. They take turns sharing the stage. This not only reduces competition between plant species, but also allows wildlife species to utilize resources throughout the growing season. Healthy ecosystems are good at supporting all the things in it. Can you spot the bee?

Most plants out here have gone to seed though, like the sunflowers, showy milkweed, and the false boneset.

And it also means time to harvest and eat stuff. Strawbaby from the garden, a cultivated plant, and common ground cherry, found growing out on the prairie.

(@irrigone finally found some ground cherries that were ripe enough to eat! They have the consistency of a tiny grape and they kinda taste like sweet tarts candy. Not bad. Ate a couple and didn't die 👍 Would recommend as a light snack.)

Exoskeleton of a plains lubber and some fringe sage. One of my fav plants out here, smells delightful.

And one of my not so favorite plants (at least out here, totally cool if found in its native home range) Mullein is a biennial plant, meaning it has a two year life cycle, and it's an invasive weed in my neck of the prairie, and arguably, the rest of the Great Plains and grassland habitats in N. America.

The first year it grows as a basal rosette, close to the ground. Basal plants grow from the root base as opposed to forming new tissue towards the top. Most grasses grow this way too, which is why you can mow it without killing the whole plant. Same thing with mullein. In order to make sure the plant does grow back during manual removal you have to pull up the tap root as well.

The second year they'll flower, and produce these massive flower stalks that produce hundreds of seeds. And they're all tiny. Some stalks can get up to 3-4 feet tall and produce thousands of seeds that stay viable in the ground for years. It's no wonder they get everywhere and are so hard to manage.

Invasive species can take over ecosystems if left unchecked and reduce the biodiversity and overall health of native habitats.

Weed management strategies and good land stewardship practices help support wildlife. Like these pronghorn. Wildlife will stick around in habitat if they can get the resources they need to survive and thrive.

Pronghorn, often referred to as antelope, are actually more related to giraffes than antelope. They're also the second fastest land animal in the world and can reach sustained running speeds of 55mph. They prefer wide open grassland habitat.

Fall is rutting season, so all the boys have been extra feisty lately and chasing everyone around. Been getting a lot more stare downs from them lately.

#friday field notes#nature#biology#ecology#nature conservation#little ghost on the prairie#lot of shots of my hands this week#me picking strange things off the ground#eating strange things off the ground#forgot to post this yesterday lol#shortgrass prairie#prairie#grasslands#pronghorn#plants#bullsnake

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conserving and Restoring North American Prairie

Home to hundreds of species of birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and pollinators, grasslands are unsung heroes. Alongside providing a haven for wildlife, this iconic landscape sequesters carbon, reduces soil erosion, ensures clean water, protects biodiversity, and more.

You might be asking yourself how we could live without the countless benefits grasslands provide us and wildlife, and the answer is - we probably wouldn’t be able to for very long.

We have lost more than 50 million acres of the landscape in the last 10 years due to climate change, agricultural conversion, invasive species, and other threats. This map can help guide voluntary conservation in this critical landscape - help us help each other keep the green areas green and restore the yellow and purple areas.

Learn more: http://ow.ly/nHQ550M4GJL

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fort Belknap Indian Community celebrates reintroduction of locally extinct swift fox.

Aaniiih and Nakoda communities have organized the restoration of local native prairie ecosystems in this landscape of the northern Great Plains just north of the Missouri River. In 1997, Fort Belknap Indian Community organized the first-ever reintroduction of locally extinct black-footed ferrets to occur on tribal land. Fort Belknap has also organized the reintroduction of bison. Since 2020, the reservation has also organized the Fort Belknap Grassland Restoration Project, a program designed for Native youth to collect native grass seeds, practice plant identification, and learn about ecology, traditional stories, and Indigenous place names. Swift fox, an indicator species closely tied to the Great Plains, had been eliminated and driven extinct across the northern Great Plains due to US-government-supported wolf- and coyote-killing programs in the twentieth century. Beginning in autumn 2020, Fort Belknap released 27 swift foxes on tribal lands. Now, as of September 2022, there are over 100 swift foxes in this prairie landscape. Between September 2020 and September 2022, Fort Belknap has observed the swift foxes pairing and breeding at 4 den sites, and the birth of 20 swift fox kits. In the next few days, Fort Belknap will release another 28 swift foxes.

From a press release, September 2022.

Excerpt:

Today the Fort Belknap Indian Community commemorated three years of its swift fox recovery program with the release of three swift foxes on Tribal lands, bringing the total to 103 recovered back to these prairie grasslands. Based on post-release monitoring efforts, the native species is reproducing in the wild, which is a critical measure of success for a self-sustaining population.

“After being absent for more than 50 years, the swift fox has returned to the grasslands of Fort Belknap and our people could not be prouder,” said Harold “Jiggs” Main, director of the Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife Department.

Over the last four years, the Nakoda (Assiniboine) and Aaniiih (Gros Ventre) Tribes of Fort Belknap have worked in collaboration with the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, Aaniiih Nakoda College, Defenders of Wildlife, American Prairie, World Wildlife Fund and Wilder Institute/Calgary Zoo on this five-year reintroduction effort.

This week, three of 28 foxes trapped in Wyoming will be released during a special ceremony held by the Fort Belknap Indian Community. The remaining 25 foxes will be released later this week. [...]

Monitoring efforts via GPS collar tracking show some foxes traveled long distances, including one documented over 200 miles away, while most have settled on Fort Belknap and the surrounding areas in Phillips and Blaine counties in Montana. At least four females and males (four dens) have been documented pairing up or “denning” and 20 kits have been born in the wild since the original reintroduction of 27 foxes in fall 2020. [...]

“It has been an honor for Defenders to play a role in the Aaniiih and Nakoda effort to bring back swift fox to their lands, and also as a long-term partner to recover buffalo and endangered black-footed ferrets back to their lands,” said Chamois Andersen, Rockies and Plains senior representative at Defenders of Wildlife. “Fort Belknap is truly a model in native plains wildlife conservation.”

The swift fox is the latest extirpated species to return to Fort Belknap, joining other iconic prairie species successfully reintroduced to Indigenous lands under the leadership of the Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife Department. Historically, swift foxes lived across much of North America’s Great Plains.

“The vast grasslands on Fort Belknap provide a home to a variety of avian and terrestrial wildlife [...]. With support from numerous partners [...], the Aaniiih and Nakoda people have been bringing Indigenous wildlife back to these native grasslands for over three decades,” said Tim Vosburgh, wildlife biologist with Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife Department. [...]

“Since its inception, American Prairie has taken inspiration from the land stewardship and rewilding efforts of the Fort Belknap Community. We are proud to stand with our neighbors and support the repatriation of swift fox to their home in Montana's Great Plains,” said Beth Saboe, senior public relations manager for American Prairie.

Swift fox numbers declined precipitously in the late 1800s, mainly due to poisoning intended for coyotes and wolves and the loss of grassland habitat. During this same time, they were also eliminated from the northern portion of their range. Swift foxes made a comeback after successful reintroduction efforts began in 1983 in Canada and on the Blackfeet and Fort Peck Indian communities in Montana. However, these reintroduced populations have yet to reconnect with populations in the southern portion of their historic range. Establishing a population of swift foxes on Fort Belknap’s lands will expand the species’ occupied range in the north and help bridge the distribution gap between existing populations to the north and south.

---

Headline, photos, captions, and text published by: Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. “Tribes Successful with Swift Fox Reintroduction Program at Fort Belknap.” 28 September 2022.

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

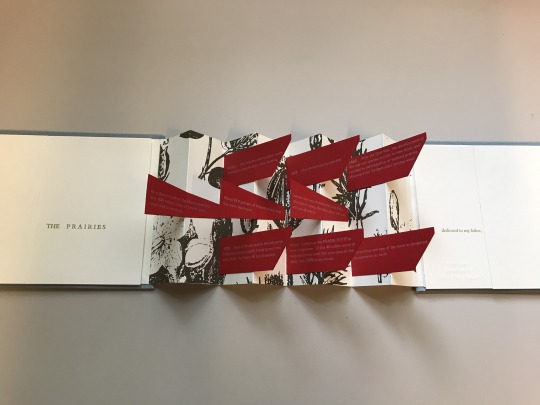

This artists’ book entitled “The prairies” by Dawn Hachenski combines a timeline of historical facts on ecological degradation on the prairies. When you learn these facts, you come to realize that the prairies are a rumination of the past. The Great Plains, as we hold in our imagination, no longer exists. Read some of these facts below:

“About 99.9 percent of tallgrass prairie land has been destroyed.”

“1990 - Most of Illinois’ prairie already gone. Tallgrass prairies rapidly being turned into corn fields, the bison all but disappear.”

“Illinois’ moniker as the PRAIRIE STATE is now a misnomer. Of the 40 million acres of tallgrass prairie land that once graced the state, only 3500 acres remain.”

“Species that once thrived in the Great Plains – the bighorn sheep, the plains grizzly and wolf are now all extinct.”

The book also combines stanzas from the poem “The Prairies” by William Cullen Bryant celebrating the plains.

The prairies

Hachenski, Dawn

Rosendale, NY : Women's Studio Workshop, 2007.

2 folded sheets ([6] pages each), 1 accordion-folded sheet with 9 red flags glued on : illustrations ; 14 x 23 cm

English

HOLLIS number: 990152988660203941

#ArtistsBook#Prairie#Ecology#DawnHachenski#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#WomensStudioWorkshop#ArtistsBooks

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Instead of starting a whole new speculative biology project like I tend to do, I decided to continue one I already have. The one I selected is my Pangea Ultima project which speculates life on Earth 250 million years from now when all the continents have reformed into a super continent like they did 250 million years ago. Where I left off on this project I was exploring the grasslands/plains on Pangea Ultima and in this post I'll showcase the (comparatively) smaller herbivores of this environment.

Plains Loper: Large descendants of crickets reaching 17 in in total body length, the Plains Lopers evolved elongated heads for reaching grasses as the wildebeest and antelope of the distant past have. Their exoskeletons have become beetle-like to provide some protection from predators but will use their powerful hind legs to escape danger.

Grass Roach: Rivaling the largest roaches of today (at 4 in.), the Grass Roach evolved extra long legs positioned below there bodies to achieve great speeds and coloration that helps them blend in with the grasses that they feed on.

Armadillopod: Giant descendants of isopods (aka pill bugs/roly-polies), these heavily armored scavengers feed on decaying plant matter, roots, and even carcases left behind by predators. If they feel threatened they will partially submerge themselves in the ground using their hook-like legs and barbed rim of their shells to hold themselves in place leaving only their remarkably durable shells exposed.

Prairie Ashbreather: Filling the ecological niche once filled by long extinct gophers and prairie dogs, the Prairie Ashbreathers dig elaborate tunnels below the grasslands with powerful claws feeding primarily on root systems though they will occasionally snag a Grass Roach if it's able to catch one.

As always, comments and critiques are welcome.

#speculative biology#speculative evolution#speculative zoology#ecology#creature design#insect#arthropods#isopods#roach#cockroach#mammals#mammal#rodent#pangea ultima#my art#digital color#digital illustration#digital art#grasslands#prairie#plains#grass#future evolution

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prairie Days

Originally posted on my website at https://rebeccalexa.com/prairie-days/.

I’m in the middle of my fall peregrinations, currently staying with family in the Missouri Ozarks as my base of operations while I do some exploring of the area, and get up to my preferred flavor of trouble. Which, of course, includes volunteering.

Ozark Rivers Audubon Nature Center

I actually got to do a little back home at Willapa National Wildlife Refuge right before I left town. They’re doing some coast meadow habitat restoration at the South Bay Unit, and so a whole pile of us showed up Wednesday before last to spend a few hours digging up invasive plants cropping up in some patches that had been intentionally planted with natives like early blue violet (Viola adunca), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), and pearly everlasting (Anaphalis margaritacea). I confess I didn’t get any pictures because I was A) pretty preoccupied with the upcoming trip, and B) nothing makes me zone out more than sitting with a trowel digging up weeds for hours at a time. By the time I get back the “nice” weather (aka warm and sunny) will likely be done for the year, but I’m hoping for more opportunities to get back out there.

But that certainly wasn’t the end of my habitat restoration efforts for the month.

For the past couple of years, every time I come into Rolla, MO I stop at the Ozark Rivers Audubon Nature Center to see if they have any upcoming stewardship activities. They’ve done a beautiful job of restoring the remnant tallgrass prairie and oak savanna there and protecting the oak-hickory forest and that surrounds them, but invasive plants being what they are there are always more to be removed as the seed bank keeps new generations popping up.

This time around we were out in the prairie/savanna area with a bunch of folks from the officer training program down at Ft. Leonard Wood just down the highway. The objective was to remove as much of the autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) as possible; this invasive shrub with a silvery underside to its green leaves can quickly shade out native prairie plants, and doesn’t offer local wildlife nearly as much food. Prescribed burns help knock it back, but some more resilient specimens manage to resprout, and of course there’s that pernicious seed bank in the soil.

Autumn olive

Most of these were much too large to simply pull up, so the most effective way to get rid of them was to go out in teams of two. One person uses loppers to cut the plant down as close to the ground as possible, and the other immediately dabs herbicide on the fresh stump, which then kills the roots and keeps the plant from regenerating. It’s a minimal use of the product when compared to spraying wide areas of foliage, and only treating the stump with a quick, targeted dab minimizes the chance of accidentally affecting surrounding native species. And since it doesn’t cause disturbance to the soil like digging would it’s less likely to stir up seeds that would then be even more likely to sprout.

I know herbicides are super controversial–they’re not my favorite thing either. But as I wrote in my chapbook Habitat Restoration: What It Is, Why It’s Important, and How to Get Started, judicious and careful use in habitat restoration is one of the few times I’m okay with it, and it’s about the only way to reliably get rid of some invasive plants permanently. Given that invasive species removal is one of THE best ways to make an ecosystem more resilient in the face of climate change, habitat restoration has to be a big priority now and going forward. While I am not ignorant of the environmental impact of routine overuse of herbicides in agriculture and yards alike, the targeted use of them in habitat restoration is definitely a “lesser of two evils” situation that deserves more nuance.

While autumn olive was the main target, we also managed to remove a few other pernicious invasives. Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana) was easy to spot with its leaves still bright green amid the various browns, golds, and reds of native vegetation. We also got rid of some privet (Ligustrum spp.), and a little Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) winding its way through the meadow. While there’s still plenty to go around for the next volunteer crew, we did make a big dent in that area.

New England aster

It wasn’t just the invasive species in evidence, though; there were plenty of native plants to enjoy along the way. One of the most prominent was field goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis nemoralis), and while some had gone to seed others still had a touch of yellow. There was a splash of purple here and there from New England aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae), and delicate white snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) edged the treeline. Amid inland oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) and other native grasses, young northern red oaks (Quercus rubra) and white oak (Quercus alba) added splashes of scarlet. It was incredibly peaceful to be immersed in these beautiful species and more.

At a time when it’s all too easy to feel overwhelmed by the enormity of environmental devastation on multiple fronts, there is something empowering about getting my hands in the dirt, so to speak. No, removing some invasive shrubs from one remnant prairie won’t save the whole world. But it helps that ecosystem become more resilient, and gives the native species there a better chance. It also makes that place a better illustration of the grasslands that were much more common in this portion of the Midwest, and is an important reminder that it wasn’t always cornfields and cattle pastures.

Yarrow

On a microcosmic level, I just feel better after spending a few hours doing a little something good in the world. I felt better walking away knowing that native plants like this young yarrow I found beneath an autumn olive we removed will be more likely to thrive in the years ahead. I’ve absorbed some of the beneficial effects of being outside, too, and gotten a good bit of exercise at my own pace. And it’s good social time, too, in a setting that feels pretty darn comfortable, and we’re all united by a common interest in that moment. This is likely my last outdoor volunteer time of the year, but it was a great note to wrap things up on.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#habitat restoration#invasive plants#invasive species#gardening#restoration ecology#ecology#herbicides#nature#environment#conservation#Missouri#Ozarks#prairie#tallgrass prairie#oak trees#oak#forest#wildflowers

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunset on the prairie. This site was one of the highest quality restored prairies I've seen, it was a privilege to survey it. 80+ native plant species!

#nature#prairie#prairies#sunset#landscape#photography#landscape photography#nature photography#north america#mine#ecology#flowers#plants#ecologist#biologist

159 notes

·

View notes