#prehistoric beakers

Text

Prehistoric Pottery Photoset 1, The National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh

#ice age#stone age#bronze age#copper age#iron age#neolithic#mesolithic#calcholithic#paleolithic#prehistoric#prehistory#prehistoric pottery#pottery fragments#pottery#urn#prehistoric beakers#beaker burial#archaeology#Scotland#relic#ancient design#artefact#ancient culture#ancient living

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

reconstruction of a male burial from the bell beaker culture

Museo Arqueológico Nacional

ph. Miguel Hermoso Cuesta

#archaeology#bell beaker culture#neolithic#prehistory#prehistoric europe#funerary rites#burial#my upl#museum

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonk's Adventure (Turbo Duo)

#bonk#r ed beaker#bonk's adventure#turbo duo#game#games#video game#video games#desert#prehistoric#caveman#cave boy#gaming#turbografx

0 notes

Photo

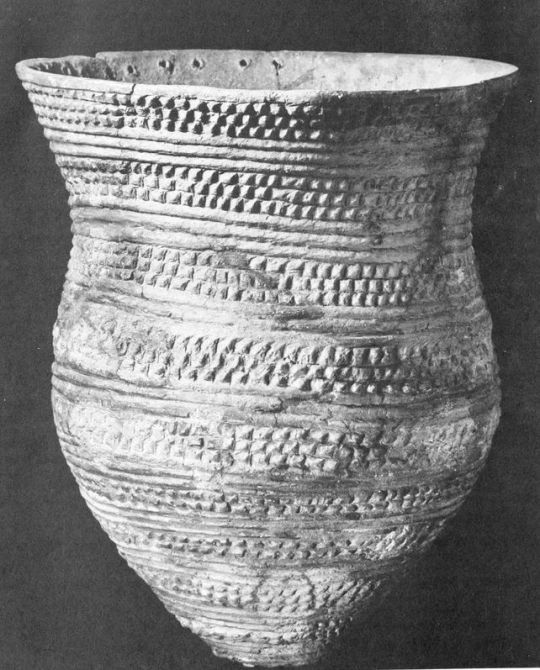

This magnificent large beaker, over a foot tall, was found near Stroe in the Veluwe region. It dates from 2000 B.C. and was made by an artist who possessed not only the skill to build up such a large pot from rolls of clay and a well developed sense of shape (see the ten sion in the silhouette line) but also desire, patience, dedication, and feeling for decoration. Alternating bands around the body of the vase, sometimes three lines, sometimes plastic squares with a rounded-off surface, make it a master piece of prehistoric work. Photo by Dienst Rijksoudheidkundig Bodemon derzoek. From "Signs, symbols and ornaments" by René Smeets, 1982. https://www.instagram.com/p/CfW_NwzNWUD/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

5. Beaker with ibex motifs

Found in present-day Susa, Iran

Neolithic Middle Eastern

Created 4200-3500 BCE

Painted terra cotta

Visual: There is a simplistic ibex that has been placed in the center. Its horns circle all the way around to its back. There is a ring of long-necked birds surrounding the top of the beaker. Below the birds are elongated dogs. These dogs accentuate the shape of the beaker. In the center of the beaker is the ibex; its long horns go around a circular object in the center and reach the ibex’s back. The horns are very large in comparison to the ibex, which is simply made of triangles and rectangles.

Context: Around this time, agriculture and permanent settlements became more common, so it is likely that the ibex, dogs, and birds would represent agriculture and domestication. Also, these people would have lived around types of mountainous species, since Susa is located in the lower Zagros mountains. Its use is unknown, but the most likely function was in burial rituals: it was found in a prehistoric burial site in Susa. Susa was also one of the first instances of urbanization in the ancient world. It was the ancient epicenter of trade for a while, so it could be considered a cultural mixing pot.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Uppåkra beaker close-up

#Archeaology#history#prehistoric#ironage#hold#beaker#Uppåkra#Scandinavia#Scania#sweden#Sverige#photography#Lund#karolinajacobsen#historiska#museum

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of the fishermen's customs still in vogue date back to prehistoric times. A rite of those who live by the sea was practised on our western shores till lately. The people by the ocean depended on the great waters not only for fish but for manure for their fields of grain, so on Hallowmas, and some say on St. Columba's Eve, they offered libations of ale and gruel to the god of the sea. A man at midnight between Wednesday night and the eve of Maunday Thursday walked waist deep into the tide and chanted the following prayer, while those on land took up the refrain:

"O God of the sea,

Put weed in the drawing wave,

To enrich the ground.

To shower on us food."

So we see along our coast there lingers the ritual of fire and oblations, and the fisher who pleads from the sea sustenance looks from his boat at the monoliths which, looming through the mist, look "like a company of stolid carlines met in council." The sea god to whom toll was paid was in some parts called Shoney. It was a chill period in which to walk into his territory and pay tribute. The people were wretchedly poor on the land side of his sovereignty, but they combined to brew ale for the ceremony. They held a prayerful service in a church by the shore first, then proceeded to watch the beaker of their home-brewed ale being poured on the waves while they chanted the lines with their chosen agent, after which they returned to the church, where a candle burned, and at a signal its feeble light was extinguished. Then, armed with provisions not wasted on Shoney, they adjourned to some field, where they ate and drank and sang till dawn. The church, like most since Columba's time, when he, the pioneer missionary, first lit the eternal light of Christianity on his lone islet on the western fringe of Scotland, had evidently decided to pander to the god of the sea and allow his worship.

-Folklore in the Lowland Scotland. Eve Blantyre Simpson. 1908.

In the Island of Lewis a sacrifice to a sea-god known as Shoney, to secure good fishing and plenty of sea-ware, was celebrated at Hallow-tide or Hallowe'en, and was discontinued only about the year 1660. At nightfall the fisher-folk went down to the sea, and having knelt and repeated the Paternoster at a spot some four miles distant from the chapel of St. Malvey, a representative of the community carrying a vessel brimming with ale, waded waist-high into the water, crying: "Shoney, I give you this cup of ale, hoping that you'll be so kind as to send us plenty of sea-ware for enriching our ground the ensuing year." He then poured the ale as a libation into the sea, after which the company repaired to the chapel for a space, whence, after a brief season of silence, they finally betook themselves to the fields, where they spent the rest of the night drinking and dancing. These folk, it may be remarked, were almost exclusively Protestants. Shoney of the Lews is almost certainly the same as the "Davy Jones" of maritime proverb - that is "the old John", or fiend, of the sea, in whose "locker" drowned seamen are retained - a memory of the belief that the drowned mariner was once regarded as a sacrifice to the demon or deity of the sea."

-The Magic Arts in Celtic Britain, Lewis Spence. Page 91.

#traditional witchcraft#folk magic#witchcraft#deity veneration#magic#quotes#scottish folklore#tradcraft

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sprawling 5,000-year-old cemetery and fortress discovered in Poland

A gigantic, 5,000-year-old complex of long barrows and stone-lined tombs has been unearthed in Poland, after archaeologists investigated lines in crops in a field that they'd seen in a satellite photograph.

Archaeologists began to excavate the rural site near the town of Dębiany, about 30 miles (50 kilometers) northeast of Kraków, more than two years ago. They've now unearthed seven Neolithic tombs, as well as the remains of an early medieval fortress and a Bronze Age burial of two horses. But the full extent of the ancient cemetery isn't yet known.

The archaeologists now think it consists of a dozen barrow mounds, each between 130 feet and 160 feet (40 meters and 50 meters) long, made from earthworks, stones and palisades of wooden poles that have now rotted away. They think it's a relic of the prehistoric settlement of the area by the Neolithic Funnel Beaker people, who are named after the distinctive pottery vessels they made and are thought to have been the first farmers in Europe. Read more.

341 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cairnpapple Hill.

Cairnpapple has been on my radar for some time, since I made a visit to nearby Torphichen Preceptory just over three years ago, thanks to Frank Stewart for taking me here last week.

This area covers many different eras, starting with the henge that dates from about 3800 BC. Centuries later the landscape was chosen for a number of Bronze Age burials. Much later still, it was used for early Christian graves, if you bring it right up to todays tourist attraction that's around 6 thousand years, that's older than the likes of Stonehenge and the Pyramids.

Cairnpapple Hill is one of the best-known prehistoric sites in mainland Scotland. Its prominence in the landscape and the fine views from its summit are at least partly why this particular location developed into such a special place.

Professor Piggott of the University of Edinburgh excavated the site in 1947–8, uncovering the henge monument and later burials across the summit of the hill. Cairnpapple had been the focus of communal activity for more than 200 generations of local farmers, and the landscape is still peppered with farms, and indeed a new "henge" as seen in my pics from yesterday, built by another local farmer.

Finds on the site include two stone-axe fragments from axe "factories" in Wales and Cumbria. Clearly the early Neolithic farmers of West Lothian didn’t lead isolated lives. The hearths are no longer visible, as they were covered by the henge monument – a great oval earthwork enclosure – built in the later Neolithic period, unfortunately it was closed last week, but Frank says he will take me back some day and hopefully get a look inside the mound.

The henge at Cairnpapple had a bank 60m across, surrounded by a broad ditch, which enclosed a ring of 24 upright timber posts. The timber hasn’t survived, but the post holes are clearly visible. There were two entrances to the henge, almost directly opposite each other.

The henge ceased to be used for ceremonial purposes about 4,000 years ago, during the early Bronze Age. But the local people clearly still revered it, as they buried an important member of the community there.

This first burial place was marked by an oval setting of stones, with a single large standing stone at its head. The body had been buried with a wooden mask covering the face. Two Beaker pots left alongside had probably been filled with food and drink to sustain the dead person on the journey to the afterlife.

Two burial cists were added later. These were stone-lined pits with a single massive capstone on top. A food vessel was found in one and a single human cremation in the other. One cist bore three cup-marks pecked into the surface. These burials were covered by a stone cairn, which was neatly edged with 21 kerb stones.

A skeleton and artefacts found at Cairnpapple can be found in the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prehistoric Pottery, The Salisbury Museum, Salisbury, Wiltshire

#ice age#stone age#bronze age#copper age#iron age#neolithic#mesolithic#calcholithic#paleolithic#prehistoric#prehistory#prehistoric pottery#pots#pottery fragments#prehistoric urns#prehistoric beakers#archaeology#relic#artefact#ancient culture#ancient craft#Salisbury

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A 1,700-year-old Skeleton of a Roman Mercenary Buried with his Sword Discovered

The 1,700-year-old skeleton of a Roman mercenary has been unearthed next to a newly-built road in the Welsh countryside.

Archaeologists discovered the mercenary buried with his sword alongside Iron Age farming tools, ancient burial sites, and the remnants of roundhouses.

A total of 456 skeletons have been recovered from the site on Five Mile Lane near Barry, South Wales, including five likely to date to the Roman period.

Among them were the mercenary and his military regalia, along with the remains of one man who had been decapitated and his head placed at his feet.

Improvement work on Five Mile Lane led to the 'significant' and 'surprising' finds, with three sites being excavated.

The earliest features found were several Bronze Age burnt pits, along with a Late Bronze Age crouch burial and artefacts from the period, including a flint arrowhead.

An Early Bronze Age beaker was also discovered to the north of the burial mound.

After the mid-to-late Bronze Age activity the next known settlement on the site occurred during the late Iron Age to early Roman transition period.

Roman pottery decorated with a leaping animal – possibly a lion or panther – was also unearthed.

Council officials brought in specialist archaeology firm Rubicon Heritage Services to manage the digs on the road leading to Cardiff Airport.

'From a ceremonial and funerary landscape in the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods, through to farming in the Iron Age and being part of a wealthy Roman farmstead, to a Medieval burial ground which reused the earlier burial mound, and finally to the post-medieval agricultural landscape we see today, the archaeologists were able to trace the development of this swathe of land, uncovering many surprises along the way,' the company said.

Mark Collard, of Rubicon Heritage Services, added: 'It was a privilege for our team to have delivered a project which added so many new discoveries about the archaeology and history of the Vale of Glamorgan.

'We're very pleased to be able now to share the results in such an accessible format with the communities of the area.'

In the 1960s, a prehistoric settlement that developed into a Roman villa was excavated following the discovery of cropmarks visible from the air.

Whitton Lodge is thought to have been occupied from about 50 BC to the 4th century AD, at the close of the Roman period.

Throughout its lifetime the settlement was characterised by changing layouts made up of from three to five buildings, archaeologists have said, but during the Roman period it formed the focus of a farmstead.

The archaeologists were assisted by the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff University, Cadw and the Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust.

Emma Reed, of Vale of Glamorgan Council, said: 'It's great to learn that the archaeological study at Five Mile Lane has uncovered such a detailed history of the area.

'The scheme has uncovered fascinating and at times surprising remains, that help us to understand the shaping of the agricultural landscape that we see today.'

After they are analysed and documented, the artefacts will be given to the National Museum of Wales.

An academic report on the finds is also due to be published later this year.

#A 1700-year-old Skeleton of a Roman Mercenary Buried with his Sword Discovered#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient grave#ancient tomb#roman history#roman expire

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think the British museum has all those looted goods in part because they know how lame their own culture is. Those rocks are nice enough on their own, but absolutely pathetic compared to just about any poc art

That’s a very interesting take. It’s difficult to assign a worth to different forms of art.

Fundamentally the people of the British Isles were too busy fighting for their life on a very shitty very cold island. While people in warmer climates like mesoamerica and Northern Africa enveloped advanced civilizations, animal and plant domestication practices, calendric and written languages, the people of the British Isles were minutes away from death at any time. They lived damp thatch houses, struggled to hunt and gather enough food to sustain themselves. Farming was introduced from mainland Europe around 4000 BC. After that they did begin to develop a complex culture and style of art. However, most of Great Britain was invaded by the Romans and forced to culturally assimilate around 43 BC. The Romans stuck around for the next 4 centuries. Independent cultural development was halted in England and most of southern Britain. Ireland and Scotland managed to beat the Roman Empire down but they still traded with them. I’m assuming you’re talking about English culture so that’s what I’m going to focus on here. If I made a post of Irish and Scottish artifacts, it would go on forever.

We know very little about the culture of prehistoric England because they didn’t write shit down and they often cremated their dead. Several different cultures existed within southern Britain, some we don’t have names for. They did create beautiful art, as well as jewelry and pottery and tools.

Here are just a few British Isles artifacts from the pre-Roman period:

Torc (necklace/choker) from around 1400 to 1100 BCE. This one is from Ireland.

Shale object, bowl or a bangle. From about 2500 BCE. Found around Stonehenge.

Gold objects from 1900 to 1700 BCE. Found around Stonehenge. Nobody is sure what they are because again, no written language. They were likely adornments for chieftains.

Here are some additional artifacts from around England:

Beaker from Yorkshire, from around 2300-1900 BCE. Part of the Bell Beaker culture.

Shield fished out of the Thames, dating around 350 to 50 BCE.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fic teaser:

John Smith and Rose Tyler both work at the Natural History Museum in London, he’s a scientist at the Ancient DNA laboratory, and she’s a salesgirl in the gift shop. They are only friends, but the upcoming staff Christmas party promises developments they’ve both been longing for.

However, before they can leave the lab to attend the party, an ancient pathogen from a prehistoric reindeer causes a lockdown.

John, Rose, Martha, Donna and Jack all get stuck together in the laboratory. Shenanigans ensue: decontamination showers, cocktails in beakers, a game of truth-or-dare and a Secret Santa rigged by meddling friends.

ETA: Complete fic on Ao3

#ficandchips#Ten x Rose#Christmas#fluff#mutual pining#friends to lovers#I plan on posting it starting this week(end?)#note the lack of title#lol#It's pretty much all written but still needs some tweaking#mine#mine: DW

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Summer Sunset, Mojácar (No. 5)

The Paleolithic Age of Almería was characterized by small nomadic and hunter-gatherer groups. The oldest Paleolithic site is Zájara Cave I (Cueva de Zájara I) in the Caves of the Almanzora (Cuevas del Almanzora).

The first villages and spaces dedicated exclusively to burials appear by the Neolithic Age, and even before the Upper Paleolithic Age. The cave paintings of the Cave of the Signs (Cueva de los Letreros) and twenty other caves and shelters of Los Vélez are dated to this era, and were designated a World Heritage site by Unesco in 1989.

In one of the shelters of the first settlers of the peninsula, the Coat of the Beehives (Abrigo de las Colmenas), there remains a human figure with arms outstretched holding an arc above its head. According to legend, this picture represents a covenant made by prehistoric man with the gods to prevent future floods. It is the earliest depiction of the Almerían Indalo, which was named in memory of Saint Indaletius, and means Indal Eccius ("messenger of the gods") in the Iberian language.

Over the years, the Indalo has become the best known symbol of Almería. Some see this figure as a man holding a rainbow, but it might also be an archer pointing a bow towards the sky. The Indalo lent its name to the artistic and intellectual movement of the Indalianos led by Jesús de Perceval and Eugenio d'Ors which was a movement of nostalgic attraction by the people of Mojácar. The people of Mojácar painted Indalos with chalk on the walls of their houses to guard against storms and the Evil Eye.

It was Luis Siret y Cels, an eminent Belgian archaeologist, who described the rich prehistoric wealth of Almería, particularly that of the Metal Age. Siret said that Almería was like "an open-air museum". Indeed, Almería is home to two of the most important cultures of the Metal Age in the peninsula: Los Millares and El Argar.

The earliest known city, Los Millares, dates to the Copper Age and is strategically located on a spur of rock between the Andarax River and the Huéchar Ravine (rambla de Huéchar), in the southern part of the province. It was a town of more than a thousand inhabitants, protected by three lines of walls and towers, and had an economy based on copper metallurgy, agriculture, animal husbandry, and hunting on a moderate scale. Furthermore, they constructed a large necropolis and exported metal figures and pottery to a large part of the peninsula.

The equally influential culture of El Argar appeared later, during the Bronze Age. They developed a characteristic form of pottery, the vaso campaniforme ("beaker") that spread throughout all of Northern Spain. Their cemeteries were more advanced with respect to the culture of Los Millares and they had diverse agricultural production and animal husbandry.

The rich customs and Fiestas of the denizens retain links deep into the past, unto the Moors, the Romans, the Greeks, and the Phoenicians.

During the taifa era, it was ruled by the Moor Banu al-Amiri from 1012 to 1038, briefly annexed by Valencia (1038–1041), then given by Zaragoza to the Banu Sumadih dynasty until its conquest by the Almoravids in 1091. Some centuries later, it became part of the kingdom of Granada.

Source: Wikipedia

#Mojácar#Andalusia#Province of Almería#Levante Almeriense#Spain#travel#España#Sierra Cabrera#moon#mountains#silhouette#sky#clouds#sunset#sundown#original photography#summer 2021#Southern Europe#southern Spain#landscape#countryside#view#orange#Iberia#colors#sky in fire#tourist attraction#landmark

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Germanic Burial styles

The Germanic people had several ways on how to deal with the dead. The style of burial changed throughout the centuries from prehistoric times to the Roman era and eventually the Christian era.

The first form of burial was practiced by the earliest permanent settlers of Western and Northern Europe, burial. Early cultures like the Ertebølle, corded ware, funnelbeaker and bell beaker culture buried their dead with the bodies often in specific positions. During Ertebølle culture, people were buried flat in a straight position. Men were buried with flint tools and women often had jewelry in their graves. Of course there are some exceptions to this.

The corded ware burials were slightly different. Males were placed on their right side in a flexed position and females on their left side with the faces of both genders oriented to the south. With the only exception being Sweden, there they did it exactly the other way around. The graves were often positioned in a line, maybe there was a wooden construction on top of these graves, a sort of a hall for the dead. In Denmark however, small burial mounds were made. The Netherlands has burial mounds as well dating back to the corded ware culture and Elp culture. The beaker culture had similar burial customs.

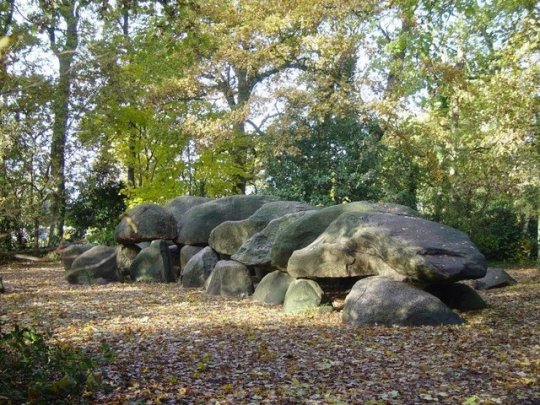

The funnelbeaker culture liked to bury their dead in chambers made of either stone, hunebedden (Dolmen in English) or they were made of wood with ground covering it, a passage grave. The dead were given burial gifts like flint tools, ceramics, jewelry and food. This culture built the homes of the living around these monumental graves indicating that ancestor worship was central to these people.

With the rise of the first true Germanic culture after the invasion of the Yamnaya people, the style of burial changed to cremation. Until the Roman era, Western Germanics burned their bodies depending on the social status of the dead person. A chief per example was given a big pile to burn the body, afterwards he was placed in a grave below stones surrounded with burial gifts like weapons, horses and jewelry. The Eastern Germanic people burned their dead as well until the Christian era.

The urns of the dead after cremation were placed in burial mounds by western Germanic people. Burial gifts were given as well, often broken objects but that all depends on the social status. Eastern Germanic people placed their urns in houses oriented towards the East. Some urns had faces carved on them, perhaps a visual representation of the dead.

When the Roman empire expanded and came into contact with Germanic people, burial customs started to change. Germanics began to adopt many Roman traditions including architecture, money, language, Gods and the way of burials. Bodies were no longer cremated but now buried in burial mounds with even more grave gifts like cups, unique weapons and bowls. Of course the amount of gifts depends on the social status. Criminals were sometimes sacrificed in bogs or otherwise their bodies were just dumped in ditches.

With the rise of Christianity the cremation-style burial was quickly banned. According to Christians, your body can not enter heaven if you destroy it. Charlemange banned cremation and it was punished by death if you did burn a body. Burial styles changed again, now bodies were buried on fields next to a church in graves often with little to no gifts. This style of burial is still practiced in the Western world until this day.

What do you think is the best way of burial?

I hope this article provides some basic knowledge about burial customs of the ancient people of western Europe.

Pictures of Corded Ware burial, burial of cremated people in urns, picture of an Anglo-Saxon urn, a passage grave, classic burial mounds and a dolmen

109 notes

·

View notes