#reign: henry vii

Text

Any judgement on (Richard III)’s reign has to be seen as provisional. The critic of the reign only has to consider how the Tudors would now be regarded if Henry VII lost at Stoke, to realize the dangers of too many assumptions about the intractability of Richard’s problems. But it would be equally unrealistic to ignore Richard’s unpopularity altogether. The fact that he generated opposition among men with little material reason for dissent, and that the disaffection then continued to spread among his own associates, says something about what contemporaries regarded as the acceptable parameters of political behaviour. There is no doubt that Richard’s deposition of his nephews was profoundly shocking. To anyone who did not accept the pre-contract story, which was probably the majority of observers, the usurpation was an act of disloyalty. Gloucester, both as uncle and protector, was bound to uphold his nephew’s interests and his failure to do so was dishonourable. Of all medieval depositions, it was the only one which, with whatever justification, could most easily be seen as an act of naked self-aggrandizement.

It was also the first pre-emptive deposition in English history. This raised enormous problems. Deposition was always a last resort, even when it could be justified by the manifest failings of a corrupt or ineffective regime. How could one sanction its use as a first resort, to remove a king who had not only not done anything wrong but had not yet done anything at all?

-Rosemary Horrox, "Richard III: A Study of Service"

#r*chard iii#my post#english history#Imo this is what really stands out to me the most about Richard's usurpation#By all accounts and precedents he really shouldn't have had a problem establishing himself as King#He was the de-facto King from the beginning (the king he usurped was done away with and in any case hadn't even ruled);#He was already well-known and respected in the Yorkist establishment (ie: he wasn't an 'outsider' or 'rival' or from another family branch)#and there was no question of 'ins VS outs' in the beginning of his reign because he initially offered to preserve the offices and positions#for almost all his brother's servants and councilors - merely with himself as their King instead#Richard himself doesn't seem to have actually expected any opposition to his rule and he was probably right in this expectation#Generally speaking the nobility and gentry were prepared to accept the de-facto king out of pragmatism and stability if nothing else#You see it pretty clearly in Henry VII's reign and Edward IV's reign (especially his second reign once the king he usurped was finally#done away with and he finally became the de-facto king in his own right)#I'm sure there were people who disliked both Edward and Henry for usurpations but that hardly matters -#their acceptance was pragmatic not personal#That's what makes the level of opposition to Richard so striking and startling#It came from the very people who should have by all accounts accepted his rule however resigned or hateful that acceptance was#But they instead turned decisively against him and were so opposed to his rule that they were prepared to support an exiled and obscure*#Lancastrian claimant who could offer them no manifest advantage rather than give up opposition when they believed the Princes were dead#It's like Horrox says -#The real question isn't why Richard lost at Bosworth; its why Richard had to face an army at all - an army that was *Yorkist* in motivation#He divided his own dynasty and that is THE defining aspect of his usurpation and his reign. Discussions on him are worthless without it#It really puts a question on what would have happened had he won Bosworth. I think he had a decent chance of success but at the same time#Pretenders would've turned up and they would have been far more dangerous with far more internal support than they had been for Henry#Again - this is what makes his usurpation so fascinating to me. I genuinely do find him interesting as a historical figure in some ways#But his fans instead fixate on a fictional version of him they've constructed in their heads instead#(*obscure from a practical perspective not a dynastic one)#queue

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Throughout Henry’s exile, Margaret (Beaufort) seems to have been a faithful correspondent, keeping her son abreast of affairs in England. Though none of their letters from this period have survived, it is highly probable that they contained sentiments similar to those she expressed in her later letters to him: she often gave him her blessing, and on one occasion, in a reflection of her affection towards him, she assured Henry that ‘I trust you shall well perceive I shall deal towards you as a kind, loving mother’. At this time, however, Margaret was clearly considering the possibility of bringing about his return, though she also recognised that this would take time. As her standing with Edward IV improved, so too did her confidence to effect a reconciliation. If she could continue to win the king’s trust, Henry’s foreign exile could potentially be brought to an end.

By the beginning of June 1482, her efforts appear to have produced some results when Edward agreed that Henry could receive a share of his grandmother the dowager Duchess of Somerset’s lands to the value of £400 (£276,500) if he were to return ‘to be in the grace and favour of the king’s highness’. Edward signed the agreement on 3 June, attaching his official seal. A draft still survives and can be found among Margaret’s papers. The groundwork for Henry to return home had been laid. Edward’s grip on the reins of power was unchallenged, and with two surviving sons, his dynasty appeared to be assured—Margaret’s son was no longer a threat. Thus it was that, on an unknown date, Edward—curiously, using the same piece of paper on which Margaret’s second husband had been created Earl of Richmond—drafted a pardon for her son. Margaret began to hope that she and Henry would soon be reunited.”

- Nicola Tallis, “The Uncrowned Queen: The Fateful Life of Margaret Beaufort, Tudor Matriarch”

#historicwomendaily#history#margaret beaufort#henry vii#edward iv#kinda#this is SO interesting - I wish more people knew of it because it really changed my perception of Margaret AND henry AND edward#at the end of his reign#also since I'm quoting from her book I just wanted to point out: Nicola Tallis was beyond horrendous towards Elizabeth Woodville#and uncritically repeated a bunch of misogynistic tudor propaganda against margaret of york#AND was very weird about elizabeth of york's alleged 'feelings' for the uncle who bastardized her and murdered her brothers#even claiming that elizabeth felt 'spurned' by him (lmao)#i know that lots of historians have major issues writing about historical women who aren't their Special Favs#and that every historian is guilty of it to some extent#but to write about THREE women like this in 2019? that definitely takes things to a whole new shitty level lol

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

AU House of Tudors: Children Henry VII and Elizabeth of York

Arthur(1486 - 1540). King of England. Husband Catherine of Aragon and father of 8 children: Edward VI, Elizabeth, Henry, George, Isabella, Margaret, Cecilia, John. The married life of Catherine and Arthur was a happy one. Prince Arthur from childhood enjoyed great popularity in his kingdom. He was loved not only by representatives of the nobility, but also by ordinary people. He was considered the most educated prince of his time. He was the pride of his parents. The period of his reign went down in history as the Golden Age of England.

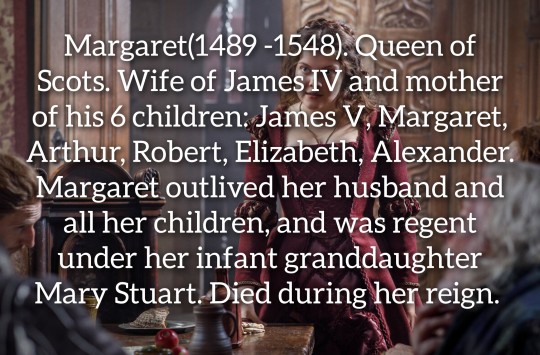

Margaret (1489 -1548). Queen of Scots. Wife of James IV and mother his 6 children: James V, Margaret, Arthur, Robert, Elizabeth, Alexander. Margaret outlived her husband and all her children, and was regent under her infant granddaughter Mary Stuart. Died during her reign.

Henry(1491 - 1547). Duke of York. Husband of Eleanor of Austria. Father of 5 children: Elizabeth, Henry, Joanna, Charles and Philip. Their marriage was an ordinary political union and although the couple had no affection for each other, there was a friendly relationship between them.

Elizabeth(1492 - 1552). Queen of France. Wife of Francis I. Between Francis and Elizabeth were warm relations. They had 10 children: Louise, Francis II, Charles, Henry, Elizabeth, Margaret, Antoine, Magdalena, Gaspard, Louis. Elizabeth influenced her husband's policies for the benefit of her country, which the king's mother disliked. Elizabeth and her mother-in-law constantly competed for Francis' influence and attention.

AU: Дети Генриха VII и Елизаветы Йоркской.

Артур(1486 - 1540). Король Англии. Муж Екатерины Арагонской и отец 8 детей: Эдуард VI, Елизавета, Генрих, Джордж, Изабелла, Маргарита, Сесилия, Джон. Супружеская жизнь Екатерины и Артура была счастливой. Принц Артур с детства пользовался большой пополярностью в своём королевстве. Его любили не только представители дворянского сословия, но и обычные люди. Считался самым образованным принцем своего времени. Был гордостью своих родителей. Период его правления вошёл в историю как Золотой Век Англии.

Маргарита(1489 -1548). Королева Шотландии. Жена Якова IV и мать его 6 детей: Яков V, Маргарита, Артур, Роберт, Елизавета, Александр. Маргарита пережила мужа и всех своих детей, была регентом при своей малолетней внучке Марии Стюарт. Умерла при её правлении.

Генрих(1491 - 1547). Герцог Йоркский. Муж Элеоноры Австрийской. Отец 5 детей: Елизавета, Генрих, Джоана, Чарльз и Филипп. Их брак был обычным политическим союзом и хотя супруги не питали к друг другу нежных чувств, но между ними были дружеские отношения.

Елизавета(1492 - 1552). Королева Франции. Жена Франциска I. Между Франциском и Елизаветой были тёплые отношения. У них родилось 10 детей: Луиза, Франциск II, Шарль, Генрих, Елизавета, Маргарита, Антуан, Магдалена, Гаспар, Людовик. Елизавета влияла на политику своего мужа на пользу своей стране, что не нравилось матери короля. Елизавета и её свекровь постоянно соперничали за влияние и внимание Франциска.

Part 1.

#history#history au#royal family#royalty#isabella#history of england#british royal family#british royalty#the tudors#the white princess#the white queen#the spanish princess#henryviii#catherine of aragon#mary tudor#au#reign#england#henry vii of england#elizabeth of york#house of york#house of tudor#english royalty#Royal#Royals#Roy

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think the funniest way to do the "modern person in historical dress becomes a ghost" joke would be to have the modern ghost be an avid fan of a relatively obscure or otherwise unpopular time period. everyone assumes they're from a different time period to the one they're actually imitating because it's not very well known.

#bbc ghosts#e.g. they're really interested in the reign of henry vii#and almost everyone assumes they died during henry viii's reign

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

Henry vii fined the Earl of Oxford 70,000?

No, it's a false story invented by Francis Bacon a century after his reign. Henry VII isn't going to overfine one of his best supporters that is John de Vere, Earl of Oxford who was his main military lieutenant as Constable and a key player in East Anglia.

However, Henry VII did fine lord Abergavenny £100, 000 for having too much retainers in 1500. I think the story stems from that.

#war of the roses#Henry VII#John de Vere#Really it shows how Bacon don't get Henry's reign#Because he kinda picked the worst magnate to make this story believable

1 note

·

View note

Text

Just want to talk about "The White Princess" because I'm rewatching it. It's not that great of a show but Idk I find King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York so handsome and I guess I like the chemistry even though I felt the romance was...rushed? Suddenly she's loyal to him..what? I think the explanation is due to baby Prince Arthur but when did she fall in love with him or did she feel like she had no choice. I kinda like the dynamic precisely because of how ambiguous it is because it is a weird situation she's in I imagine. Having to marry a man who's her enemy...

I will not give Philipa's fanfiction about Richard and Elizabeth of York any mind here.

Speaking of, one of the reasons I keep coming back is due to my biggest complaint about this series. King Henry VII is way too handsome here lol but I love it.

What I hate...is that he's portrayed as a whiny brat who apparently after a, what?, decade of rule, seems to comprehend that nobles plotting behind his back comes with the job? It annoys me because idk I feel like the real King Henry VII was more politically astute, and while I have no complaints about Margaret Beaufort's role in politics, though idk how much she was involved in history, I don't understand why Elizabeth of York is given so much credit in this series but I guess it's because it's a feminist series where women are always plotting against each other and men are idiots?

I have only myself to blame for getting into this trash series lol

#The White Princess#also the guy who plays King Henry VII is hot#did I mention that?#I just wish he wasn't portrayed as a whiny incompetent baby#who according to Gregory#his reign is owed to the women in his life#which i could believe his women did influence#by that I mean his mother and wife#I'm okay with that#but goddamn this guy was training to get the thrown and defeated King Richard in Bosworth#and then managed to keep his crown afterwards#give him some fucking credit man

0 notes

Text

KINGS & QUEENS REGNANT OF ENGLAND ACCORDING TO STARZ

Henry VI (1 September 1422 - 4 March 1461, 3 October 1470 - 11 April 1471 second reign) as portrayed by David Shelley in The White Queen

Edward IV (4 March 1461 - 3 October 1470, 11 April 1471 - 9 April 1483 second reign) as portrayed by Max Irons in The White Queen

Edward V (9 April 1483 - 25 June 1483) as portrayed by Sonny Ashbourne Serkis in The White Queen

Richard III (26 June 1483 - 22 August 1485) as portrayed by Aneurin Barnard in The White Queen

Henry VII ( 22 August 1485 - 21 April 1509) as portrayed by Jacob Collins-Levy in The White Princess

Henry VIII (22 April 1509 - 28 January 1547) as portrayed by Ruairi O'Connor in The Spanish Princess

Edward VI (28 January 1547 - 6 July 1553) as portrayed by Oliver Zetterstrom in Becoming Elizabeth

Jane Grey (10 July 1553 - 19 July 1553) as portrayed by Bella Ramsey in Becoming Elizabeth

Mary I (19 July 1553 - 17 November 1558) as portrayed by Romola Garai in Becoming Elizabeth

Elizabeth I (17 November 1558 - 24 March 1603) as portrayed by Alicia Von Rittberg in Becoming Elizabeth

James I and VI of Scotland (24 March 1603 - 27 March 1625) as portrayed by Tony Curran in Mary & George

Charles I (27 March 1625 - 30 January 1649) as portrayed by Samuel Blenkin in Mary & George

#perioddramaedit#the white queen#the white princess#the spanish princess#becoming elizabeth#mary and george#my edits#twqedit#twpedit#thespanishprincessedit#becomingelizabethedit#maryandgeorgeedit#david shelley#max irons#sonny ashbourne serkis#aneurin barnard#jacob collins levy#ruairi o'connor#oliver zetterstrom#bella ramsey#romola garai#alicia von rittberg#tony curran#samuel blenkin#henry vi#edward iv#edward v#richard iii#henry vii#henry viii

170 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Rhaenyra would have killed her siblings or it was mere paranoia on Alicent's side? The book doesn't provide a solid answer for this, and in the show it's clear that Rhaenyra would never harm her siblings.

Hi anon, I kind of went into it in this post, and although that ask was about Jace vs. Aegon III, I think the principle remains the same. In short, no, I don't think it was paranoia, but to understand why, we have to understand why Rhaenyra's brothers pose a particular threat to the stability of Rhaenyra (of Jace's) rule. Keep in mind, this isn't a moral failing specific to Rhaenyra, but simply a byproduct of the conditions of her inheritance.

I don't think Rhaenyra would have wanted to kill her siblings (or their kids), or even have planned to kill her siblings, but I also think that ultimately what she wanted wouldn't matter very much. All it would take would be someone wishing to rise in her esteem claiming that Aegon was fermenting rebellion, perhaps producing a forged letter as evidence, or an eyewitness who would swear that he had been secretly meeting with former greens. Could she risk it? Her brothers are weapons that can always be used against her. And at some point, it would be out of her control. Rhaenyra won't live forever, nor will Daemon, and when Jace attempts to take the throne, with no less than 7 legitimate male claimants alive who would have a claim ahead of him, there are bound to be challengers. The Blackfyre rebellion began with much flimsier pretexts.

We have real life examples of this. Henry VII intended to keep the remaining Plantagenets alive when he took the throne, as long as they stayed loyal. After all, they were his wife's family members, and killing them off would not be a good look. But the remaining Plantagenets would always be a threat to the Tudors. Ten year old Edward Plantagenet, the son of George of Clarence, was imprisoned in the Tower of London for 14 years before he was executed in 1499 for a supposed connection to Perkin Warbeck's scheme. Henry VII finally took action at least in part because he was negotiating a betrothal between his heir and the daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. The Spanish monarchs did not want their daughter marrying a man whose succession could be challenged, and so Edward, the strongest claimant at that point, had to go. Henry VII's son, Henry VIII, increasingly worried about the stability of his own succession, became vulnerable to the whisperings of opportunists looking to rise in the king's esteem and eliminate their own political enemies. At this point, the remaining Plantagenet claimants became a source of paranoia, justified or not. The arrest and execution of Margaret Pole, the niece of Edward IV and Richard III, was based upon a tunic found in her home that supposedly represented her support for her son's claim to the throne and the restoration of the Catholic church in England. The tunic was almost certainly planted by Henry VIII's chief minister, the protestant Thomas Cromwell, the same man who orchestrated Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon (yes, the same princess whose hand Edward Plantagenet had died to secure). And Henry VIII liked Margaret, she'd been the governess to his daughter, and though they had their ups and downs, he certainly didn't hate her. Still, when her son was put forward as a rival claimant and she was accused of supporting him, she had to go too. And of course, going backwards a bit, there are famously the princes in the tower, Edward and Richard, sons of King Edward IV, who despite having been officially declared bastards (a law, you see, was not enough), were still enough of a threat to the throne that they were (most likely) murdered, whether by Richard III or one of his associates. Mere rumors that those boys still lived sparked rebellions during the reign of Henry VII.

And you can say well, there's a difference, surely, in that Rhaenyra is the rightful queen, and these other people were not? But "rightful" is not some inherent state of being, it's dependent upon who is in power. Every person who sits the throne believes themself to be the rightful king or queen. But Rhaenyra in particular gained her position because her father exercised his power and declared her heir in defiance of the expected order of inheritance, contradicting the very decision that made him king in the first place. After Viserys dies though, for all intents and purposes his wishes cease to matter. He is no longer king, and lacks any mechanism by which to enforce his wishes from beyond the grave. At that point, people will choose to support one claimant or another, based upon their own concerns (dragon math, precedent, oaths, promises made by one or the other, existing family bond) and to consider Rhaenyra or Aegon (or any other claimant down the road) the rightful king/queen. Rhaenyra's security upon the throne, like the position of Henry VII or Richard III, is inherently weaker because she comes to the throne through unconventional means. All it takes is a plague year, a famine, or a foreign invasion for any random group of lords to decide that the true king Aegon/Aemond/Jaehaerys/Maelor should be on the throne and that they should start a rebellion in his name. If Rhaenyra feels insecure in her rule, or in Jace's ability to peacefully inherit after her, it only makes sense to eliminate any potential rivals, and her brothers and their children will always be a threat, no matter her original intentions. Even if Rhaenyra keeps her word and does not harm her family, her brothers and their line pose a threat to Jace and his line as long as both lines exist.

So Alicent is not being paranoid at all, she's being realistic. If Viserys were to disinherit Rhaenyra, or were Rhaenyra to accept the peace terms and give up her claim, she would become simply another sister, but Aegon can never be just another brother to Queen Rhaenyra because in the eyes of some, he will always be a potential rallying point for dissenters, and if not him then his brothers, or his children, whether they want to be or not. That's the point Alicent is making. It's not a reflection on Rhaenyra's character, it's just that if it came down to a choice between securing her reign/Jace's succession, and the lives of her potential political rivals, it's not difficult to guess what Rhaenyra would choose.

174 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi I recently discovered your account and I’m obsessed your writing is amazing and I don’t know if you’re still doing Tudor!reader Fics but if you are I have a request.

So reader is Anne Boleyn’s eldest daughter and had to watch her mothers execution (for the storyline reader was 12 or so years old) and never forgave her farther so when she’s like 15 (maybe the day after Catherine Howard’s execution) she overthrows him as revenge.

I hope you understand what I’m trying to say total understand if you don’t want to right it. Have a good day/night❤️

A/N: I love how kooky the timeline would have to be warped for this to be possible but I absolutely love the idea of this! So sorry for taking so long to write this, real life does enjoy getting in my way :(

Revenge

Someone had to stop King Henry VII, your father, from his increasingly brutal reign. Lady Mary, your half-sister, seemed unable to do anything without the counsel of her precious Ambassador Chapuys. Elizabeth was of course just a child, too young to rule. Edward was a mere baby. It seemed to you that the responsibility of saving the realm fell solely on your shoulders. It was a burden you were glad to take.

You were grateful that you’d had enough time being raised by your mother Anne Boleyn, that you had learnt how to be as cunning and manipulative as she had once been. Of course, having Mary as an older sister helped solidify those ideals, as Mary was able to inspire a great deal of loyalty in others when she wanted to.

It had been a long, arduous task to slowly turn the King’s courtiers against him. An entire year had passed before the perfect opportunity had finally arisen. Only two days had passed since poor Queen Catherine Howard had been executed on your father’s orders. Though you hadn’t been the greatest fan of the silly child, she was just like you… an innocent girl. Too many young women’s lives had been destroyed on the whims of an undeserving King, and the unrest among the populace seemed at its highest. It was the perfect time to strike.

The foundations you had laid throughout the year, telling little white lies here and there, promising things that you’d never do in order to gain the loyalty of the courtiers, would serve you well. The King had noticed some changes but could never trace them back to you. Often you would have agents loyal to you do the work that needed to be done while you were at home with Elizabeth in the country, creating a wonderful alibi.

Knowing that the King seemed to be favouring Catherine, the Lady Latimer, as his potential sixth wife, you realised that she would be the perfect distraction for your coup. You knew she wanted to be with Thomas Seymour so she would be likely to help you, especially as you had always had a good relationship with her growing up. Elizabeth, of course, was easy to manipulate into playing the part that you needed her to.

You dressed in your most regal black dress, deliberately picking out jewels and a French hood that made you look like a true ruler. You took a deep breath in and out to try to calm your nerves and your trembling hands before you went into the court. You gave a subtle nod to Catherine Parr who, along with Elizabeth, went up to the King to talk to him and distract him.

As soon as the King had begun discussing something with them both, you gave the signal to your loyal people who captured his guards and those you knew were still loyal to him, discreetly dragging them away.

You gave a sly, satisfied smile as you secretly prepared your weapon behind your back. You knew that your father’s greatest fear was getting sick, so you poured a poison on your blade before walking up to him, curtsying, and then holding the blade tightly against his throat. “Y/N! What is this?!” King Henry asks incredulously, clearly not believing one of his daughters could pull this off, his face grew white as he saw all the people loyal to you with their weapons drawn.

“I am now your Queen. You will take orders from me, and no one else.” You call out to the people in the court, who begin to cheer. You smile smugly to yourself as you see your father’s world crashing down around him.

“Why, Y/N? Just… why?” You give an incredulous laugh, sneering at him. “Why, father? For my mother.” You lean forwards, your breath touching his face as you snarl your words.

You turn to your guards, and give a sweet smile. “Throw him in the tower.” You command, pushing your father towards them. You sit on the throne, looking around at your successful coup. Allowing yourself a few moments to gloat in your glory, you immediately turn to your advisors. The Queen had work to do.

#platonic reader insert#the tudors reader insert#the tudors x reader#the tudors imagine#henry vii x reader#catherine parr x reader#anne boleyn x reader#elizabeth tudor x reader

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grimsthorpe Castle

Hi guys!!

I'm sharing another grand english state!

House History: The building was originally a small castle on the crest of a ridge on the road inland from the Lincolnshire fen edge towards the Great North Road. It is said to have been begun by Gilbert de Gant, Earl of Lincoln in the early 13th century. However, he was the first and last in this creation of the Earldom of Lincoln and he died in 1156. Gilbert's heyday was the peak time of castle building in England, during the Anarchy. It is quite possible that the castle was built around 1140. However, the tower at the south-east corner of the present building is usually said to have been part of the original castle and it is known as King John's Tower. The naming of King John's tower seems to have led to a misattribution of the castle's origin to his time.

Gilbert de Gant spent much of his life in the power of the Earl of Chester and Grimsthorpe is likely to have fallen into his hands in 1156 when Gilbert died, though the title 'Earl of Lincoln' reverted to the crown. In the next creation of the earldom, in 1217, it was Ranulph de Blondeville, 4th Earl of Chester (1172–1232) who was ennobled with it. It seems that the title, if not the property was in the hands of King John during his reign; hence perhaps, the name of the tower.

During the last years of the Plantagenet kings of England, it was in the hands of Lord Lovell. He was a prominent supporter of Richard III. After Henry VII came to the throne, Lovell supported a rebellion to restore the earlier royal dynasty. The rebellion failed and Lovell's property was taken confiscated and given to a supporter of the Tudor Dynasty.[2]

The Tudor period

This grant by Henry VIII, Henry Tudor's son, to the 11th Baron Willoughby de Eresby was made in 1516, together with the hand in marriage of Maria de Salinas, a Spanish lady-in-waiting to Queen Catherine of Aragon. Their daughter Katherine inherited the title and estate on the death of her father in 1526, when she was aged just seven. In 1533, she became the fourth wife of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, a close ally of Henry VIII. In 1539, Henry VIII granted Charles Suffolk the lands of the nearby suppressed Vaudey Abbey, founded in 1147, and he used its stone as building material for his new house. Suffolk set about extending and rebuilding his wife's house, and in only eighteen months it was ready for a visit in 1541 by King Henry, on his way to York to meet his nephew, James V of Scotland. In 1551, James's widow Mary of Guise also stayed at Grimsthorpe. The house stands on glacial till and it seems that the additions were hastily constructed. Substantial repairs were required later owing to the poor state of the foundations, but much of this Tudor house can still be seen today.

During Mary's reign the castle's owners, Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk (née Willoughby) and her second husband, Richard Bertie, were forced to leave it owing to their Anglican views. On Elizabeth's succeeding to the throne, they returned with their daughter, Susan, later Countess of Kent and their new son Peregrine, later the 13th Baron. He became a soldier and spent much of his time away from Grimsthorpe.

The Vanbrugh building

By 1707, when Grimsthorpe was illustrated in Britannia Illustrata, the 15th Baron Willoughby de Eresby and 3rd Earl Lindsey had rebuilt the north front of Grimsthorpe in the classical style. However, in 1715, Robert Bertie, the 16th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, employed Sir John Vanbrugh to design a Baroque front to the house to celebrate his ennoblement as the first Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven. It is Vanbrugh's last masterpiece. He also prepared designs for the reconstruction of the other three ranges of the house, but they were not carried out. His proposed elevation for the south front was in the Palladian style, which was just coming into fashion, and is quite different from all of his built designs.

The North Front of Grimsthorpe as rebuilt by Vanbrugh, drawn in 1819. Vanbrugh's Stone Hall occupies the space between the columns on both floors.

Inside, the Vanbrugh hall is monumental with stone arcades all around at two levels. Arcaded screens at each end of the hall separate the hall from staircases, much like those at Audley End House and Castle Howard. The staircase is behind the hall screen and leads to the staterooms on the first floor. The State Dining Room occupies Vanbrugh's north-east tower, with its painted ceiling lit by a Venetian window. It contains the throne used by George IV at his Coronation Banquet, and a Regency giltwood throne and footstool used by Queen Victoria in the old House of Lords. There is also a walnut and parcel gilt chair and footstool made for the use of George III at Westminster. The King James and State Drawing Rooms have been redecorated over the centuries, and contain portraits by Reynolds and Van Dyck, European furniture, and yellow Soho Tapestries woven by Joshua Morris around 1730. The South Corridor contains thrones used by Prince Albert and Edward VII, as well as the desk on which Queen Victoria signed her coronation oath. A series of rooms follows in the Tudor east range, with recessed oriel windows and ornate ceilings. The Chinese drawing room has a splendidly rich ceiling and an 18th-century fan-vaulted oriel window. The walls are hung with Chinese wallpaper depicting birds amidst bamboo. The chapel is magnificent with superb 17th-century plasterwork.

More history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimsthorpe_Castle

This house fits a 64x64 lot and features several impressive rooms, more than 29 bedrooms, a servants hall and several state rooms!

I only decored some of the main rooms, for you to have a glimpse of the distribution. The rest is up to you, as I have stated that I do not like interiors :P

Be warned: I did not have the floor plan for the tudor rooms, thus, the distribution is based on my own decision and can not fit the real house :P.

You will need the usual CC I use: all of Felixandre, The Jim, SYB, Anachrosims, Regal Sims, TGS, The Golden Sanctuary, Dndr recolors, etc.

Please enjoy, comment if you like it and share pictures with me if you use my creations!

DOWNLOAD (Early acces: June 30) https://www.patreon.com/posts/grimsthorpe-101891128

#sims 4 architecture#sims 4 build#sims4#sims4play#sims 4 screenshots#sims 4 historical#sims4building#sims4palace#sims 4 royalty#ts4 download#ts4#ts4 gameplay#ts4 simblr#ts4cc#ts4 legacy#sims 4 gameplay#sims 4 legacy#sims 4 cc#thesims4#sims 4#the sims 4#sims 4 aesthetic#ts4 cc#english manor

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite History Books || Triumph and Illusion: The Hundred Years War Volume 5 by Jonathan Sumption ★★★★☆

The wheel of fortune is one of the most ancient symbols of mankind, an image of capricious fate and the transience of human affairs. In the late middle ages it was everywhere, in illuminated manuscripts, in wall paintings and stained glass, in sermons and homilies, in poetry and prose. ‘The wheel of fortune turneth as a ball, sudden climbing axeth a sudden fall,’ wrote John Lydgate in The Fall of Princes, a work commissioned by one of the dominant figures in this history, Cardinal Henry Beaufort. The present volume traces the remarkable recovery of France in barely two decades from the lowest point of its fortunes to the dominant position in Europe which it had enjoyed before the wars with England. Sudden climbing axeth a sudden fall. These years saw the collapse of the English dream of conquest in France from the opening years of the reign of Henry VI, when the battles of Cravant and Verneuil consolidated their control of most of northern France, until the loss of all their continental dominions except Calais. This sudden reversal of fortune, inexplicable to many contemporary Englishmen, was a seminal event in the history of the two principal nation-states of western Europe. It brought an end to four centuries of the English dynasty’s presence in France, separating two countries whose fortunes had once been closely intertwined. It created a new sense of identity in both of them. In large measure, the divergent fortunes of the French and English states over the following centuries flowed from these events.

The passions generated by ancient wars eventually fade, but those provoked by the wars of the English in fifteenth-century France have proved to be surprisingly durable. The foundations of scholarship on the period were laid by patriotic French historians of the nineteenth century, writing under the shadow of Waterloo and Sedan. The passage of the centuries did nothing nothing to soften their indignation about the fate of their country in the time of Henry VI and the Duke of Bedford. The extraordinary life and death of Joan of Arc defied historical objectivity until quite recently. Joan’s story became the focus of disparate but powerful political passions: nationalism, Catholicism, royalism and intermittent anglophobia. Much of what has been written falsifies history by attributing to medieval men and women the notions of another age. But myths are powerful agents of national identity. The great French historian Marc Bloch once wrote that no Frenchman could truly understand his country’s history unless he thrilled at the story of Charles VII’s coronation at Reims. Writing in the summer of 1940 in the aftermath of a terrible defeat, Bloch looked to an earlier recovery from the edge of disaster for reassurance about the survival of France.

If there is a corresponding English myth, it is in the history plays of Shakespeare. The great speeches which he gave to John of Gaunt and Henry V belong to the classic canon of English patriotism. His three plays about Henry VI, a truncated story of discord at home and defeat abroad, never reach the same heights. Yet they serve to remind us that behind the clash of arms and principles were men and women of flesh and blood. I have tried at every page to remember that they were not cardboard cut-outs. They endured hunger, saddle-sores and toothache. They experienced fear and elation, joy and disappointment, shame and pride, ambition and exhaustion. At the level of government, they were trapped by the logic of war, lacking the resources to conquer or even to defend what they had, and yet unable to make peace. It was the tragedy of the English that, after an initial surge of optimism in the 1420s, they realised that the war could not be won, but were forced to fight on by the memory of Henry V’s triumphs and the incapacity of his son, until disaster finally engulfed them.

#litedit#historyedit#hundred years' war#medieval#history books#french history#english history#european history#history#nanshe's graphics

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas Penn writes about 500 year old dead historical figures like they're celebrities in a gossip column

#it's funny to an extent but after a point it gets very grating#he has a wealth of information but he's far too sensationalistic and florid#and tends to choose the most unsympathetic and/or colorful interpretation of every situation and historical figure#he also has a habit of ... narrativizing history which doesn't really work for me#also his fatphobia re Edward IV was absolutely revolting#I was planning on ordering the Winter King but after looking at the synopsis and first 2 chapters that were available online - no thanks#I'm definitely not interested in reading about Henry VII supposedly being 'sinister' and 'Machiavellian' because he...ruled successfully?#because he did what kings (unfortunately) did all the time? How was he any different from the others?#also imagine calling *Henry VII* ruthless & unscrupulous when his predecessor murdered his own kid-nephews and his successor was Henry VIII#like please be serious#I had the same issue with the way he described Edward IV's reign. His descriptions were so theatrical and emphatic but#at the end of the day the things he was describing were very normal lol#or they would be normal if Penn didn't choose the most critical (and mocking tbh) perspective for every single thing#the way he described Henry VI's reign was also annoying but it thankfully had far less pagetime and was not the focus of his work#so it was comparatively more tolerable#i'm glad that he acknowledged the propaganda against Margaret tho. I didn't like how he described her but at the very least he acknowledged#that she was being slandered#also calling Warwick 'the regime's biggest headache' lmfao#and ig some of his analyses on Richard III were interesting. It helps that R3 had a very short and very dramatic reign from start to finish#so Penn's flourishing tone doesn't really feel out of place for it

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

tudor what ifs i think about somewhat regularly

elizabeth of york survives well into her son’s reign

edmund tudor (henry vii’s youngest son) survives into adulthood, gets married and has issue (i think this is actually the THING that would have made both henry vii and henry viii’s lives a lot happier)

anne boleyn’s pregnancies all result in healthy children but all three are girls

anne of cleves and henry do consumate their marriage once and anne gets pregnant

edward vi marries elisabeth of valois

elizabeth i marries robert dudley in 1561

jasper tudor and catherine woodville have children

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

@une-sanz-pluis I read the bit where you wrote:

And I immediately remembered this hilarious piece of trivia from Henry VII’s reign:

Absolutely the most buffoonish looney tunes-ish goofy aah way to murder a king.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looks like Philippa Langley might've done it again as she's written a new book about new evidence she and other historians have found that Edward V and Prince Richard of York actually escaped and were never murdered. Her book is out now in the UK and this is one of the many articles coming out ahead of the documentary that's getting ready to air in the UK this weekend and here in the US on PBS the 22nd, and from what I'm reading these new pieces of evidence does seem to point to the boys actually making it to Europe and that both those pretenders actually were them. One of new evidence found in the Netherlands is a written confession supposedly by Richard of York in Rome detailing how he and his brother escaped. The new evidence is coming from both Italy and France and has been authenticated to the correct time period during Henry VII's reign.

They're saying the new evidence has already changed some minds about this and I'll judge for myself when I watch the doc next week (as either the book doesn't have a US release date yet or my library isn't getting it) but Philippa already was able to find Richard III's remains and get him reburied, and this has been a long thing to clear up just like they did with proving that Shakespeare and others made him more monstrous than he was. My belief was that Richard III might've ordered the princes deaths (as that was common with monarchs and who they deem as threats to the throne) and then regretted it, but maybe so many of us have been wrong this whole time. Again this proves why the whole Wars of the Roses is one of my favorite historical time periods and things are still playing out.

#richard iii#philippa langley#the princes in the tower#edward v#richard of york#history#royal family

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wives and Daughters of Holy Roman Emperors: Age at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

This list does not include women who died before their husbands were crowned Emperor. It spans between the beginning of the reign of Otto I (962 CE) and the end of the reign of Francis II (1806 CE).

The average age at first marriage among these women was 17. The sample size was 91 women. The youngest bride, Bianca Maria Sforza, was just 2 years old when she wed her first husband, who was himself 9. The oldest bride, Constance of Sicily, was 32 years old.

Adelaide of Italy, wife of Otto I, HRE: age 15 when she married Lothair II, King of Italy, in 947 CE

Liutgarde of Saxony, daughter of Otto I, HRE: age 15 when she married Conrad the Red, Duke of Lorraine, in 947 CE

Theophanu, wife of Otto II, HRE: age 17 when she married Otto in 972 CE

Cunigunde of Luxembourg, wife of Henry II, HRE: age 24 when she married Henry in 999 CE

Gisela of Swabia, wife of Conrad II, HRE: age 12 when she married Brun I of Brunswick in 1002 CE

Agnes of Poitou, wife of Henry III, HRE: age 18 when she married Henry in 1043 CE

Matilda of Germany, daughter of Henry III, HRE: age 11 when she married Rudolf of Rheinfelden in 1059 CE

Judith of Swabia, daughter of Henry III, HRE: age 9 when she married Solomon, King of Hungary in 1063 CE

Bertha of Savoy, wife of Henry IV, HRE: age 15 when she married Henry in 1066 CE

Agnes of Waiblingen, daughter of Henry IV, HRE: age 14 when she married Frederick I, Duke of Swabia in 1086 CE

Empress Matilda, wife of Henry V, HRE: age 12 when she married Henry in 1114 CE

Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy, wife of Frederick I, HRE: age 13 when she married Frederick in 1156 CE

Beatrice, daughter of Frederick I, HRE: age 10 when she married Guillaume II, Count of Chalon in 1173 CE

Constance, Queen of Sicily, wife of Henry IV, HRE: age 32 when she married Henry IV in 1186 CE

Beatrice of Swabia, first wife of Otto IV, HRE: age 14 when she married Otto in 1212 CE

Maria of Brabant, second wife of Otto IV, HRE: age 24 when she married Otto in 1214 CE

Constance of Aragon, first wife of Frederick II, HRE: age 19 when she married Emeric of Hungary in 1198 CE

Isabella II of Jerusalem, second wife of Frederick II, HRE: age 13 when she married Frederick in 1225 CE

Isabella of England, third wife of Frederick II, HRE: age 21 when she married Frederick in 1235 CE

Margaret of Sicily, daughter of Frederick II, HRE: age 14 when she married Albert II, Margrave of Meissen in 1255 CE

Anna of Hohenstaufen, daughter of Frederick II, HRE: age 14 when she married John III Doukas Vatatzes in 1244 CE

Marie of Luxembourg, daughter of Henry VII, HRE: age 18 when she married Charles IV of France in 1322 CE

Beatrice of Luxembourg, daughter of Henry VII, HRE: age 13 when she married Charles I of Hungary in 1318 CE

Margaret II, Countess of Hainaut, wife of Louis IV, HRE: age 13 when she married Louis in 1324 CE

Matilda of Bavaria, daughter of Louis IV, HRE: age 10 when she married Frederick II, Margrave of Meissen in 1323 CE

Beatrice of Bavaria, daughter of Louis IV, HRE: age 12 when she married Eric XII of Sweden in 1356 CE

Anna von Schweidnitz, wife of Charles IV, HRE: age 14 when she married Charles in 1353 CE

Elizabeth of Pomerania, wife of Charles IV, HRE: age 16 when she married Charles in 1378 CE

Margaret of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV, HRE: age 7 when she married Louis I of Hungary in 1342 CE

Catherine of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV, HRE: age 14 when she married Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria in 1356 CE

Elisabeth of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV, HRE: age 8 when she married Albert III, Duke of Austria in 1366 CE

Anne of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV, HRE: age 16 when she married Richard II of England in 1382 CE

Margaret of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV, HRE: age 8 when she married John III, Burgrave of Nuremburg in 1381 CE

Barbara of Cilli, wife of Sigismund, HRE: age 13 when she married Sigismund in 1405 CE

Elizabeth of Luxembourg, daughter of Sigismund, HRE: age 13 when she married Albert II of Germany in 1422 CE

Eleanor of Portugal, wife of Frederick III, HRE: age 18 when she married Frederick in 1452 CE

Kunigunde of Austria, daughter of Frederick III, HRE: age 22 when she married Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria in 1487 CE

Bianca Maria Sforza, wife of Maximilian I, HRE: age 2 when she married Philibert I, Duke of Savoy in 1474 CE

Margaret of Austria, daughter of Maximilian I, HRE: age 17 when she married John, Prince of Asturias in 1497 CE

Barbara von Rattal, daughter of Maximilian I, HRE: age 15 when she married Siegmund von Dietrichstein in 1515 CE

Dorothea of Austria, daughter of Maximilian I, HRE: age 22 when she married Johan I of East Frisia in 1538 CE

Isabella of Portugal, wife of Charles V, HRE: age 23 when she married Charles in 1526 CE

Maria of Austria, daughter of Charles V, HRE: age 20 when she married Maximilian II, HRE in 1548 CE

Joanna of Austria, daughter of Charles V, HRE: age 17 when she married John Manuel, Prince of Portugal in 1552 CE

Margaret of Parma, daughter of Charles V, HRE: age 14 when she married Alessandro de’ Medici, Duke of Florence, in 1536 CE

Elizabeth of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand I, HRE: age 16 when she married Sigismund II Augustus of Poland in 1543 CE

Anna of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand I, HRE: age 17 when she married Albert V, Duke of Bavaria in 1546 CE

Maria of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand I, HRE: age 15 when she married William of Julich-Cleves-Berg in 1546 CE

Catherine of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand I, HRE: age 16 when she married Francesco III Gonzaga in 1559 CE

Eleanor of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand I, HRE: age 27 when she married William I, Duke of Mantua in 1561 CE

Barbara of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand I, HRE: age 26 when she married Alfonso II d’Este in 1565 CE

Joanna of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand I, HRE: age 18 when she married Francesco I de’ Medici in 1565 CE

Anna of Austria, daughter of Maximilian II, HRE: age 21 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1570 CE

Elisabeth of Austria, daughter of Maximilian II, HRE: age 16 when she married Charles IX of France in 1570 CE

Anna of Tyrol, wife of Matthias, HRE: age 26 when she married Matthias in 1611 CE

Eleonora Gonzaga the Elder, wife of Ferdinand II, HRE: age 24 when she married Ferdinand in 1622 CE

Maria Anna of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand II, HRE: age 25 when she married Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria in 1635 CE

Cecilia Renata of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand II, HRE: age 26 when she married Władysław IV of Poland in 1637 CE

Maria Anna of Spain, wife of Ferdinand III, HRE: age 25 when she married Ferdinand in 1631 CE

Maria Leopoldine of Austria, wife of Ferdinand III, HRE: age 16 when she married Ferdinand in 1648 CE

Eleonora Gonzaga the Younger, wife of Ferdinand III, HRE: age 21 when she married Ferdinand in 1651 CE

Mariana of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand III, HRE: age 15 when she married Philip IV of Spain in 1649 CE

Eleonore of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand III, HRE: age 17 when she married Michael I of Poland in 1670 CE

Maria Anna Josepha of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand III, HRE: age 24 when she married Johann Wilhelm II, Elector Palatine in 1678 CE

Margaret Theresa of Spain, wife of Leopold I, HRE: age 15 when she married Leopold in 1666 CE

Claudia Felicitas of Spain, wife of Leopold I, HRE: age 20 when she married Leopold in 1673 CE

Eleonore Magdalene of Neuberg, wife of Leopold I, HRE: age 21 when she married Leopold in 1676 CE

Maria Antonia of Austria, daughter of Leopold I, HRE: age 16 when she married Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria in 1685 CE

Maria Anna of Austria, daughter of Leopold I, HRE: age 25 when she married John V of Portugal in 1708 CE

Wilhelmine Amalie of Brunswick, wife of Joseph I, HRE: age 26 when she married Joseph in 1699 CE

Maria Josepha of Austria, daughter of Joseph I, HRE: age 20 when she married Augustus III of Poland in 1719 CE

Maria Amalia of Austria, daughter of Joseph I, HRE: age 21 when she married Charles VII, HRE in 1722 CE

Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick, wife of Charles VI, HRE: age 17 when she married Charles in 1708 CE

Maria Theresa of Austria, daughter of Charles VI, HRE: age 19 when she married Francis I, HRE in 1736 CE

Maria Anna of Austria, daughter of Charles VI, HRE: age 26 when she married Charles Alexander of Lorraine in 1744 CE

Maria Antonia of Bavaria, daughter of Charles VII, HRE: age 23 when she married Frederick Christian, Elector of Saxony in 1747 CE

Maria Anna Josepha of Bavaria, daughter of Charles VII, HRE: age 20 when she married Louis George of Baden-Baden in 1755 CE

Maria Josepha of Bavaria, daughter of Charles VII, HRE: age 26 when she married Joseph II, HRE in 1765 CE

Maria Christina, daughter of Francis I, HRE: age 24 when she married Albert Casimir, Duke of Teschen in 1766 CE

Maria Amalia, daughter of Francis I, HRE: age 23 when she married Ferdinand I, Duke of Parma in 1769 CE

Maria Carolina, daughter of Francis I, HRE: age 16 when she married Ferdinand IV & III of Sicily in 1768 CE

Maria Antonia, daughter of Francis I, HRE: age 14 when she married Louis XVI of France in 1770 CE

Maria Josepha of Bavaria, wife of Joseph II, HRE: age 26 when she married Joseph in 1765 CE

Maria Luisa of Spain, wife of Leopold II, HRE: age 19 when she married Leopold in 1764 CE

Maria Theresa of Austria, daughter of Leopold II, HRE: age 20 when she married Anthony of Saxony in 1787 CE

Maria Clementina of Austria, daughter of Leopold II, HRE: age 20 when she married Francis I of Sicily in 1797 CE

Maria Theresa of Naples, wife of Francis II, HRE: age 18 when she married Francis in 1790 CE

Marie Louise, daughter of Francis II, HRE: age 19 when she married Napoleon I of France in 1810 CE

Maria Leopoldina, daughter of Francis II, HRE: age 20 when she married Pedro I of Brazil and IV of Portugal in 1817 CE

Clementina, daughter of Francis II, HRE: age 18 when she married Leopold of Salerno in 1816 CE

Marie Caroline, daughter of Francis II, HRE: age 18 when she married Frederick Augustus of Saxony in 1819 CE

34 notes

·

View notes