#rené lefèvre

Photo

René Lefèvre in Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (Jean Renoir, 1936)

Cast: René Lefèvre, Florelle, Jules Berry, Marcel Lévesque, Odette Talazac, Henri Guisol, Maurice Baquet, Sylvia Bataille, Nadia Sibirskaia. Screenplay: Jean Castanier, Jacques Prévert, Jean Renoir. Cinematography: Jean Bachelet.

M. Lange's crime is murder, and he gets away with it. This droll dark comedy is a vehicle for Jean Renoir's anti-fascist politics, and to enjoy it to the fullest you probably have to have been there -- "there" being Europe in 1936. But it still resonates 80-plus years later with its story of a little guy exploited by a venal fat cat. Lange (René Lefèvre), who writes adventure stories about "Arizona Jim" in the wild West, works for a greedy, corrupt publisher named Batala (Jules Berry), who not only stiffs him on a contract to publish the stories, but also inserts advertising plugs into the story itself, making Arizona Jim pause to pop one of the sponsor's pills before launching into action. Batala is also a shameless womanizer who impregnates Estelle (Nadia Sibirskaia), the girlfriend of Charles (Maurice Baquet), the bicycle messenger who works for him. (In a rather cold-hearted twist you probably won't see in movies today, everyone rejoices when the baby dies.) Fleeing from his creditors, Batala reportedly dies in a train wreck, and to salvage their jobs, his employees, encouraged by Meunier (Henri Guisol), the son of Batala's chief creditor, form a cooperative to run the publishing company. It's a huge success, with Lange's stories becoming incredibly popular -- so much so that a film company wants to buy the rights to make an Arizona Jim movie. Unfortunately, Lange doesn't own the rights, as Batala reveals when he turns up very much alive, disguised as a priest who happened to be standing by him during the crash. When Batala begins demonstrating his old ways, including making a play for all the available women in the company as well as asserting his rights to Arizona Jim and the profits it has made, Lange shoots him, then flees with his girlfriend Valentine (Florelle). Aided by Meunier, they reach an inn near the border -- which one isn't specified -- where, while Lange rests up, Valentine tells his story and leaves it up to the people at the inn whether they will turn him in. There's some famously show-offy camerawork from cinematographer Jean Bachelet, but the real energy of the film comes from Renoir's company of vivid, talkative characters, whose chatter and whose relationships unfold so rapidly that you may want to see the film twice to appreciate them. Le Crime de Monsieur Lange is second-tier Renoir but, with its genuine affection for human beings, it's better than most directors' top-tier work.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LE DOULOS - Jean-Pierre Melville (1962)

À sa sortie de prison, Maurice rentre chez lui, blanc comme un linge, les mâchoires serrées. Il y retrouve son patron, un receleur de bijoux qu’il soupçonne d’être responsable de la mort de sa femme, et l’abat d’un coup de revolver. Il se réfugie chez sa poule et prépare un cambriolage avec Silien. Lequel porte un chapeau mou et dans le jargon des caïds, le doulos, c’est l’indic… Melville tourna…

View On WordPress

#film noir#jean desailly#jean paul belmondo#jean pierre melville#michel piccoli#rené lefèvre#serge reggiani

0 notes

Photo

Cais, Praça XV - Rio de Janeiro - Renée Lefèvre

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

90 Movies for 90 Days: Le Million (1931)

Every day until March 31, 2024 I will be watching and reviewing a movie that is 90 minutes or less.

Title: Le Million

Release Date: April 15, 1931

Director: René Clair

Production Company: Tobis Sound Company

Summary/Review:

A cash-strapped artist, Michel (René Lefèvre) is mobbed by his creditors when he learns that his number was selected in a lottery that will make him a millionaire. …

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

Mémoires d'outre-tombe. Tome 3 by François-René de Chateaubriand Part 3/...

Nel gennaio 2014 lo Stato francese ha acquisito l'unica copia originale integrale della prima edizione delle Mémoires. Datato 1847, l'esemplare reca le correzioni autografe, le cancellature e le sottolineature di Chateaubriand. Il volume, di 3000 pagine, apparteneva allo studio Beaussant-Lefevre di Parigi; ora è custodito alla Bibliothéque nationale de France. Chateaubriand usava dettare sistematicamente ad una segretaria i suoi libri prima di bruciare il brogliaccio dopo la stampa. Infatti, non esiste alcun manoscritto di questo capolavoro letterario.

En janvier 2014, l'État français a acquis le seul exemplaire original complet de la première édition des Mémoires. Daté de 1847, l'exemplaire porte les corrections autographes, ratures et traits de soulignement de Chateaubriand. Le volume, de 3000 pages, appartenait à l'atelier Beaussant-Lefèvre à Paris; il est aujourd'hui conservé à la Bibliothèque nationale de France. Chateaubriand dictait systématiquement à une secrétaire ses livres avant de brûler la fraude après l'impression. En fait, il n'existe aucun manuscrit de ce chef-d'œuvre littéraire.

0 notes

Photo

Gueule d'Amour (1937) dir. Jean Grémillon

#gueule d'amour#anthonyasquith#bergmaningrid#usermichi#filmedit#classicfilmblr#jean gabin#rené lefèvre#gifs#mine

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lady Killer / Gueule d’amour (1937) dir. Jean Grémillon

Lan Yu / 藍宇 (2001) dir. Stanley Kwan

#............................. HMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM#lan yu#gueule d'amour#jean grémillon#stanley kwan#parallels*#m*#jean gabin#rené lefèvre#hu jun#liu ye

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

jean gabin and rené lefèvre in gueule d’amour (1937)

#filmedit#classicfilmblr#motionpicturesource#doyouevenfilm#jean gabin#rené lefèvre#gueule d'amour#1937#1930s#jean grémillon#french cinema#m: gueule d'amour (1937)#*#**#bw#important moments in cinema™

121 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le crime de Monsieur Lange (Jean Renoir, 1936)

#Le crime de Monsieur Lange#Jean Renoir#quote#art#dreams#Renoir#black and white#1936#René Lefèvre#Jules Berry

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

René Lefèvre

Le Crime de monsieur Lange, Jean Renoir (1936).

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lady Killer ‘Gueule d'amour’ (1937)

Directed by Jean Grémillon

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

René Lefèvre and Annabella in Le Million (René Clair, 1931)

Cast: Annabella, René Lefèvre, Jean-Louis Allibert, Paul Ollivier, Constantin Siroesco, Vanda Gréville, Odette Talazac, Pedro Elviro, Jane Pierson, André Michaud, Eugène Stuber, Pierre Alcover, Armand Bernard. Screenplay: René Clair, based on a play by Georges Berr and Marcel Guillemaud. Cinematography: Georges Périnal. Art direction: Lazare Meerson. Music: Armand Bernard, Philippe Parès, Georges Van Parys.

The French do wonderful things with air. They invented the soufflé and Champagne, and the Montgolfier brothers mastered the art of ballooning. And no French director had a greater gift for buoyancy than René Clair, whose mastery of pacing keeps even the most cockamamie of stories from collapsing, going flat, or crashing to Earth. Le Million is the quintessential Clair film, a musical farce that inspired countless movies, some of which don't always stay aloft. You can see the lineaments of the Marx Brothers' A Night at the Opera (Sam Wood, 1935) in it as well as Jacques Demy's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967). The story is much ado about a lottery ticket left in an old jacket owned by a young artist (René Lefèvre) with a mountain of debts, and it carries us from his studio to the jail to backstage at the opera and back again, sometimes journeying over the rooftops of Paris, all of which are embodied not by the real things but by Lazare Meerson's evocative sets. The music is pretty but forgettable, which is really all you need it to be.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jean Renoir considered LE CRIME DE MONSIEUR LANGE (’36) to be a turning point in his career, a film that opened “the door to some projects that are more completely personal.” He would go on to make A DAY IN THE COUNTRY (’36) and THE LOWER DEPTHS (’36) immediately after (I have written about both in previous weeks), on which he had significantly more control. LANGE was originally proposed and conceived by Jacques Becker, and its script was later revised by Jacques Prévert. Renoir invited Prévert on set to collaborate in its production. The film is a provocative blend of performance styles, with the radical Popular Front aligned October Group (Florelle, Maurice Baquet, Sylvia Bataille, Jacques-Bernard Brunius) meeting the old-fashioned theatrical boulevardiers, the latter exemplified by Jules Berry’s craven, charismatic depiction of the womanizer Batala, owner and operator of a struggling publishing house. His incompetence and greed take advantage of mild-mannered Western writer Lange (René Lefèvre) until Batala disappears and the company is run cooperatively by its employees. It is a both a joyous vision of a worker-run business and finely tuned character study of what could drive a man to murder.

Justifiable Homicide: LE CRIME DE MONSIEUR LANGE (’36)

#Le Crime De Monsieur Lange#Jean Renoir#Jacques Prévert#Jules Berry#René Lefèvre#FilmStruck#StreamLine Blog

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

le crime de monsieur lange (1936)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

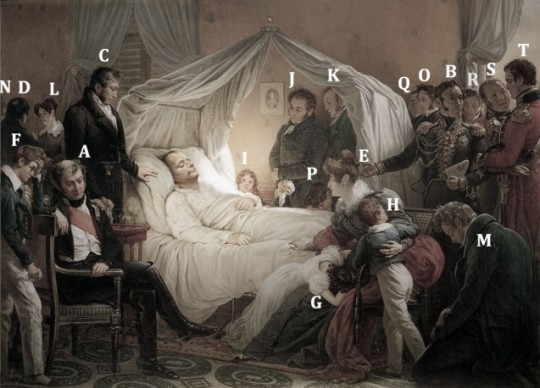

Vivant, il a manqué le monde ; mort, il le possède.

- François René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848), Vie de Napoléon, livres XIX à XXIV des Mémoires d’outre-tombe (posthume)

Of course we don’t have any photograph or film of Napoleon’s death on 5 May 1821 on Saint Hélène. But we do have the next best thing: a painting. Charles de Steuben depiction of Napoleon's deathbed and his faithful entourage that served as witnesses to his dying moments became the one of the most important paintings of the post-Napoleonic era but then faded from modern memory.

I first came across it by accident when I was in my teens at my Swiss boarding school. There were times I found myself with school friends going away on hiking trips around the high Alpine chain of the Allgäu Alps and we would drive through Lake Constance to get there, or we would hike around the Lake itself through the Bodensee-Rundwanderweg.

Perched high above Lake Constance and nestled in large parklands, stood Schloss Arenenberg which overlooks the lower part of Lake Constance. At first, it appears a relatively modest country house. But this was no usual pretty looking house. Arenenberg was owned by well-heeled families before it was sold to Hortense de Beauharnais, the adopted daughter and sister-in-law of the French Emperor himself, Napoleon Bonaparte. She had it rebuilt in the French Empire style and lived there from 1817 with her son Louis Napoleon, later Emperor Napoleon III, who is said to have spoken the Thurgau dialect in addition to French. This elegantly furnished castle then was once the residence of the last emperor of France.

The alterations made first by Queen Hortense and later by Empress Eugénie have been carefully preserved and the house still bears the marks of both women. Queen Hortense's drawing room is perfectly preserved and visitors can still admire her magnificent library (all marked with the Empress' cipher) containing over one thousand books. Likewise, in the room where the queen died, every object has been maintained in its original condition: pieces of furniture and personal belongings are gathered here to evoke her memory in a very touching manner. As for Empress Eugénie's rooms, they too have been very carefully preserved. Her private drawing room is a perfect illustration of the Second Empire style with sculptures by Carpeaux and portraits of the imperial family by Winterhalter.

After 1873, the Empress and the Imperial Prince brought the palace back to life by making regular summer visits, which they continued until 1878. However, on the tragic death of her son in 1879, Eugénie found it difficult to return to a place so full of painful memories. And so in 1906 she donated the estate to the canton of Thurgovie as a testimony of her gratitude for the region's faithful hospitality towards the Napoleon family. And in accordance with the Empress' wishes, the residence was turned into a museum devoted to Napoleon.

In what is now the Napoleonic Museum, the original furnishings have been preserved, and the palace gardens had been fully restored. This in itself might be worth a visit for the view over Lake Constance which is stunning. For Napoleonic era buffs though its the incredible art collection which is its real treasure. It houses an important art collection including works by the First-Empire artists Chinard Canova, Gros, Robert Lefèvre, Gérard, Isabey and Girodet-Trioson, and by the Second-Empire painters and sculptors Alfred de Dreux, Winterhalter, Carpeaux, Meissonier, Hébert, Flandrin, Detaille, Nieuwerkerke and Giraud.

But what caught my eye was this painting, ‘La Mort de Napoléon’ by Charles de Steuben. I didn’t know anything about it or the artist for that matter, but one of my more erudite school friends who, being French, was into Napoleonic stuff in a huge way, and she explained it all to me. Of course I knew a fair bit about Napoleon growing up because my grandfather and father, being military men themselves, were Napoleonic warfare buffs and it rubbed off onto me. I just knew about Napoleon the military genius. I never thought about him once he was beaten at Waterloo in 1815. So I never really engaged with Napoleon the man. And yet here I was staring at his last breath of mortality caught forever in time through art. Not for the first time I had mixed feelings about Napoleon Bonaparte, both the man and the myth (built up around him since his death).

On 5 May, 1821, at 5.49pm in Longwood House on the remote island of St Helena, in the words of the famed French man of letters, François-René de Chateaubriand, ‘the mightiest breath of life which ever animated human clay’ came no more. To the British, Dutch, and Prussian coalition who had exiled Naopleon Bonaparte there in 1815, he was a despot, but to France, he was seen as a devotee of the Enlightenment.

In the decade following his demise, Napoleon’s image underwent a transformation in France. The monarchy had been restored, but by the late 1820s, it was growing unpopular. King Charles X was seen as a threat to the civil liberties established during the Napoleonic era. This mistrust revived Napoleon’s reputation and put him in a more heroic light.

Fascination with the French leader’s death led Charles de Steuben, a German-born Romantic painter living in Paris, to immortalise the momentous event. Steuben’s painting depicts the moment of Napoleon’s death and seeks to capture the sense of awe in the room at the death of a man whose legendary career had begun in the French Revolution. It was this, ultimate moment that Steuben wished to immortalise in a painting which has since become what could almost be described as the official version of the scene.

There is no question that Steuben’s painting became the most famous and most iconic depiction of Napoleon’s death in art history. In another painting, executed during the years 1825-1830, Steuben was to give a realistic view of the emperor dictating his memoirs to general Gourgaud. This same realism also pervades his version of Napoleon’s death, and it is totally unlike Horace Vernet’s, Le songe de Bertrand ou L’Apothéose de Napoléon (Bertrand’s Dream or the apotheosis of Napoleon) which, although painted in the same year, is an allegorical celebration of the emperor’s martyrdom and as such the first stone in the edifice of the Napoleonic legend.

And what a legend Napoleon’s life was turned into for time immemorial. Napoleon declared himself France’s First Consul in 1799 and then emperor in 1804. For the next decade, he led France against a series of European coalitions during the Napoleonic Wars and expanded his empire throughout much of continental Europe before his defeat in 1814. He was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba, but he escaped and briefly reasserted control over France before a crushing final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Napoleon’s military prowess earned him the fear of his enemies, but his civil reforms in France brought him the respect of his people. The Napoleonic Code, introduced in 1804, replaced the existing patchwork of French laws with a unified national system built on the principles of the Enlightenment: universal male suffrage, property rights, equality (for men), and religious freedom. Even in his final exile on St. Helena, Napoleon proved a magnetic presence. Passengers of ships docked to resupply would hurry to meet the great general. He developed strong personal bonds with the coterie who had accompanied him into exile. Although some speculate that he was murdered, most agree that Napoleon’s death in 1821, at the age of 51, was the result of stomach cancer.

By contrast, Charles de Steuben was born in 1788, his youth and artistic training coinciding with Napoleon’s rise to power. He was the son of the Duke of Württemberg officer Carl Hans Ernst von Steuben. At the age of twelve he moved with his father, who entered Russian service as a captain, to Saint Petersburg, where he studied drawing at the Art Academy classes as a guest student. Thanks his father's social contacts in the court of the Tsar, in the summer of 1802 he accompanied the young Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia (1786–1859) and granddaughter of Frederick II Eugene, Duke of Württemberg, to the Thuringian cultural city of Weimar, where the Tsar's daughter two years later married Charles Frederick, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (1783–1853). Steuben, then fourteen years old, was a Page at the ducal court, a position for which the career prospects would be in the military or administration. The poet Friedrich Schiller was a family friend who at once recognised De Steuben's artistic talent and instilled in him his political ideal of free self-determination regardless of courtly constraints.

At the behest of Pierre Fontaine in 1828 de Steuben painted La Clémence de Henri IV après la Bataille d'Ivry, depicting a victorious Henry IV of France at the Battle of Ivry. De Steuben's Bataille de Poitiers, en octobre 732, painted between 1834 and 1837, shows the triumphant Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours, also known as the Battle of Poitiers. He painted Jeanne la folle around the same time and he was commissioned by Louis Philippe to paint a series of portraits of past Kings of France.

Life in the French capital was a repeated source of internal conflict for Steuben. The allure of bohemian Paris and his military-dominated upbringing made him a wanderer between worlds. As an official commitment to his adopted country he became a French citizen in 1823. However, the irregularity of his income as a freelance artist was in contrast to his sense of duty and social responsibility. To secure his family financially, he took a job as an art teacher at École Polytechnique, where he briefly trained Gustave Courbet. In 1840 he was awarded a gold medal at the Salon de Paris for his highly acclaimed paintings.

The love of classical painting was a lifelong passion of Steuben. He was a close friend to Eugène Delacroix, the leader of the French Romantic school of painting, whom he portrayed several times. Steuben was also part of this artistic movement, which replaced classicism in French painting. "The painter of the Revolution," as Jacques-Louis David was called by his students, joined art with politics in his works. The subjects of his historical paintings supported historical change. He painted mainly in sharp colour contrasts, heavy solid contours and clear outlines. The severity of this style led many contemporary artists - including Prud'hon - to a romanticised counter movement. They preferred the shadowy softness and gentle colour gradations of Italian Renaissance painters such as Leonardo da Vinci and Antonio da Correggio, whose works they studied intensively. Steuben, who had begun his training with David, felt the school was becoming increasingly rigid and dogmatic. Critics praised his deliberate compositions, excellent brush stroke and impressive colour effects. But some of his critics felt that his pursuit of dramatic design of rich people also showed, at times, a pronounced tendency toward the histrionic.

The portrayal of key moments in Napoleon’s dramatic military career would feature among some of Steuben’s best known works. But it is this death scene that Steuben is most remembered for.

Using his high-level contacts among figures in Napoleon’s circle, Steuben interviewed and sketched many of the people who had been present when Napoleon died at Longwood House on St. Helena. He wanted to attempt o give the most accurate representation of the scene possible. Indeed, the painter interviewed the companions of Napoleon’s captivity on their return to France and had them pose for their portraits. Only the Abbé Vignali, captain Crokat and the doctor Arnott were painted from memory. The Grand maréchal Bertrand made sketches of the plan of the room, noting the positions of the different pieces of furniture and people in the room. All the protagonists within the painting brought together some of their souvenirs and in posing for the painter, each person can be seen contributing to a work of collective memory, very much with posterity in mind.

Painstakingly researched, Steuben painted a carefully composed scene of hushed grief. Notable among the figures are Gen. Henri Bertrand, who loyally followed Napoleon into exile; Bertrand’s wife, Fanny; and their children, of whom Napoleon had become very fond.

The best known version of “La Mort de Napoléon” was completed in 1828. French writer Stendhal considered it “a masterpiece of expression.” In 1830 the installation of a more liberal monarchy in France further boosted admiration of Napoleon, who suddenly became a wildly popular figure in theatre, art, and music. This fervour led to the diffusion of Steuben’s deathbed scene in the form of engravings throughout Europe in the 1830s. As Napoleon’s stock arose within French culture and arts, so did Steuben’s depiction of Napoleon’s death. It became a grandeur of vision that permeated Steuben’s masterpiece of historical reconstruction.

Initially forming part of the collection of the Colonel de Chambrure, the painting was put up for auction in Paris, on 9 March 1830, with other Napoleonic works, notably Horace Vernet’s Les Adieux de Fontainebleau (The Fontainebleau adieux) and Steuben’s Retour de l’île d’Elbe (The return from the island of Elba). The catalogue noted that the painting had already been viewed in the colonel’s collection by “three thousand connoisseurs” – which alone would have made it a success -, but its renown was to be further amplified by the production of the famous engraving. The diffusion of this engraving by Jean-Pierre-Marie Jazet (1830-1831, held at the Musée de Malmaison), reprinted and copied countless times throughout the 19th century, made the scene a classic in popular imagery, on a level of popularity with paintings such as Millet’s Angelus.

A / Grand Marshal Henri-Gatien Bertrand. Utterly loyal servant of Napoleon’s to the last. His memoirs of the exile on St Helena were not published until 1849. Only the year 1821 has ever been translated into English.

B / General Charles Tristan de Montholon. Courtier and companion of Napoleon’s exile. Montholon managed to ease Bertrand out and become Napoleon’s closest companion at the end, highly rewarded in Napoleon’s will, which Montholon helped write. Montholon’s untrustworthy memoirs were published in 1846/47.

C / Doctor Francesco Antommarchi. Corsican anatomy specialist. Sent by Napoleon’s mother from Rome to St Helena to be Napoleon’s personal physician on the expulsion of Barry O’Meara. Napoleon disliked and distrusted Antommarchi. Antommarchi’s untrustworthy memoirs were very influential and published in 1825.

D / Angelo Paolo Vignali, Abbé. Corsican assistant-chaplain, sent by Madame Mère from Rome to St Helena in 1819.

E / Countess Françoise Elisabeth “Fanny” Bertrand and her children: Napoléon (F), who carried the censer at Napoleon’s funeral; Hortense (G); Henry (H); and Arthur (I), youngest by six years of all the Bertrand children and born on the island. She was wife of the Grand Marshal, very unwilling participant in the exile on St Helena. Her relations with Napoleon were difficult since she refused to live at Longwood. She spoke fluent English. Was however very loyal to Napoleon.

J / Louis Marchand. Napoleon’s valet from 1814 on and one of his closest servants. As Napoleon noted in his will, “The service he [Marchand] rendered were those of a friend”.

K / “Ali”, Louis Étienne Saint-Denis. Known as “the Mamluk Ali”, one of Napoleon’s longest-serving and intimate servants; He became Librarian at Longwood and was an indefatigable copyist of imperial manuscripts.

L / Ali’s English (Catholic) wife, Mary ‘Betsy’ Hall. She was sent out from England by UK relatives of the Countess Bertrand to be governess/nursemaid to the Bertrand children. Married Ali aged 23 in October 1819.

M / Jean Abra(ha)m Noverraz. From the Vaud region in Switzerland. Very tall and imposing figure that Napoleon called his “Helvetic bear”. He was himself ill during Napoleon’s illness.

N / Noverraz’s wife, Joséphine née Brulé. They married in married in July 1819, and she was the Countess Montholon’s lady’s maid. Noverraz and Saint-Denis had a fist fight for the hand of Joséphine.

O / Jean Baptiste Alexandre Pierron. The cook, dessert specialist, long in Napoleon’s service and who had accompanied Napoleon to Elba.

P /Jacques Chandelier. Iincorrectly identified on the picture as Santini who had left the island in 1817. A cook, from the service of Pauline Bonaparte, Napoleon’s sister, who arrived on St Helena with the group from Rome in 1819.

Q /Jacques Coursot. Butler, from the service of Madame Mère, Napoleon’s mother, he arrived on St Helena with the group from Rome in 1819.

R / Doctor Francis Burton. Irish surgeon in the 66th regiment who had arrived on St Helena only on 31st March 1821. He is renowned for having made Napoleon’s death mask (with ensign John Ward and Antommarchi).

S/ Doctor Archibald Arnott. Surgeon in the 20th regiment. Brought in to tend to Napoleon in extremis on 1 April 1821.

T/ Captain William Crokat. A Scot, orderly officer at Longwood for less than a month, having replaced Engelbert Lutyens on 15 April. He received the honour of carrying the news of Napoleon’s death back to London and also the reward, namely, a promotion and £500, privileges of which Lutyens was deliberately deprived by the governor.

#charles de steuben#art#painting#napoleon#bonaparte#st helena#life#death#chateaubriand#french#france#emperor#artist#aesthetics#war#politics#society#culture#arts#personal

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Savary, Duke of Rovigo.

Anne Jean Marie René Savary, Duc de Rovigo, by Robert Lefèvre, 1814.

Anne Marie Jean René Savary was born on April 26, 1774, in Marcq (Ardennes), son of an officer who had managed, thanks to his service, to become a Knight of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Louis and at the end of his career, major of the Place of Sedan. That’s where the young boy grew.

He had two older brothers, and the eldest, Ponce, was a classmate of Napoléon Bonaparte in Brienne and in the Régiment de La Fère. Savary himself enlisted in 1790, aged 16, in a cavalry regiment, the Royal-Normandie (1674-1962).

As many officers emigrated, Savary was promoted sous-lieutenant in September 1791. His career was only beginning. He fought with Général Custine, then Pichegru, Moreau, Férino, and finally Desaix.

With Desaix, he was in the Armée du Rhin and then in Egypt. He participated to the Battle of the Pyramids, and to the Second Italian Campaign, till Marengo, where he was the one to find and recognize Desaix’ s body. Savary, who liked Desaix and admired his skills and humanity, brought his body back to the closest town to be buried, and broke the news to Bonaparte.

Trusting Desaix’ judgment and impressed by his loyalty and his energy Bonaparte took him as his aide-de-camp.

Savary then became Napoléon’s right-hand man. Bonaparte gave him several police operations to lead. He even became close to the family by marrying a distant relative of Joséphine, Félicité de Faudoas.

In 1803, Savary, now a Général de Brigade, discovered the Plot of Cadoudal, which incriminated generals Pichegru and Moreau. Pichegru was arrested and killed himself, Moreau was exiled. Cadoudal himself refused to ask for mercy and was beheaded.The conspirers seemed to have been waiting for a prince of the royal blood to come back to France.

In 1804, Bonaparte decided to have the Duke of Enghien, of the House of Condé, princes of the royal blood, emigrated to Germany, arrested, for supposedly being part of the Cadoudal Plot. Many reasons have been offered regarding his real motives, but the Duke was kidnapped in Germany, brought to Strasbourg and then Vincennes, judged without witnesses and Savary was present. He was close to the First Consul, led the elite gendarmerie troops of Vincennes, and his presence undoubtedly weighed on the verdict.

The Duke denied any participation to any plot, but bravely stated his opposition to the Republic, for which he was condemned to death. He was shot in the moats of the Castle of Vincennes, by these gendarmerie troops, in front of Savary. Later, writing his memoirs, Savary would minimize his own part in the execution.

General Savary then found himself back to the battlefields, participating to the Campaign of Austerlitz, and then the Campaign of Prussia and Poland (Fourth Coalition). He excelled in Iena where, chasing the routed Prussians, he managed to capture a whole regiment of Hussars. In early 1807, he had to replace an ill Marshall Lannes at the head of the Vth Corps, covering Varwaw after the Battle of Eylau, and on February 16, he won his major victory, defeating the Russians in the battle of Ostrolenka. The Emperor rewarded him with a pension of 20000 francs and the Great Eagle of the Légion d’Honneur.

After a short term as a governor in Eastern Prussia, he was sent as an ambassador to Saint Petersburg. He was charged in particular to make sure the continental blocus would be respected. In spite of the Tsar’s affected amiability, the Russian aristocraty saw him as the muderer of a prince; plus, his bluntness and taste for action did not fit the diplomatic profile; the Emperor replaced him with Caulaincourt.

In 1808 he was created Duc de Rovigo and sent to Spain.

Savary was sent to bring Napoleon’s orders to Murat. At this time many things were kept secret and informations and orders were contradictory. When Murat fell ill, Savary had to take his place; his orders had to be countersigned by Murat’s chief of staff, Général Belliard, who obeyed him unwillingly.

Savary found another opponent in the French Ambassador La Forest, who objected to Savary’s preference for repression. He also had to come to terms with Napoleon’s orders and the fact that they did not often take into account the information he had sent the Emperor. For example, he was ordered by him to send all available back up to Marshal Bessières, ignoring General Dupont in Bailen. Bessières won in Medina de Rioseco, but Dupont finally capitulated in Bailen, which was the first serious defeat for Napoleon.

That’s when rumors of a plot let by Talleyrand and Fouché reached Savary and Napoléon - to replace the Emperor with another member of the family (supposedly Murat). Fouché fell then in disgrace, and Napoléon replaced him with Savary.

After a friendly interview with Savary, Fouché systematically and methodically burned all of his police archives, leaving his unpopular successor blind. The whole network had to be rebuilt.

Savary slowly managed to ingratiate himself and do some efficient work; his wife’s receptions helped, as well as his own efforts on his harsh temper. Even the royalist milieux somewhat relented.

But the Minister of Police took many unpopular decisions (placing on files, recordings, bans, censorship ), making his own prefects uncomfortable. Madame de Staël was the most famous victim of this censorship.

For as much as Napoleon relied on him, he often favored his opponents whenever he had a dispute with the other ministries (Decrès, Maret). And finally the Imperial Police was humiliated when Général Malet, detained for conspiracy, escaped, went to the nearest barracks with a fake senatus-consult in hand, claiming that the Emperor was dead in Russia and that the Republic had been proclaimed. The attempted Coup d’Etat eventually failed, but the Police was discredited and Savary especially ridiculed (as the conspirers had surprised him in bed and sent him to the prison of La Force).

Napoléon, displeased, had other major problems to consider first. Savary was loyal to him to the end, in spite of his doubts. When Marie-Louise and Joseph Bonaparte left Paris with the King of Rome, it was against Savary’s advice. But he made a mistake himself, allowing Talleyrand to stay in Paris, and to finally negotiate with Marmont.

Savary did join Napoléon during the Hundred Days, and was greeted without enthusiasm. Fouché was again the Minister of Police.

After Waterloo, Savary did not join Napoléon in Saint Helena (excluded by the British for his role in the execution of the Duke of Enghien). And Fouché had him on a prosciption list. Sentenced in absentia, Savary went to Smyrne (today, Izmir), but had soon to leave the Ottoman Empire, and moved between Trieste, Gratz, Smyrne again, London, and back to France.

His second trial began in December 1819, and his lawyer, André Dupin, was the one who a few years ago had defended Marshal Ney. This time, Savary was unanimously acquitted. He kept his titles and dignities, but no responsibility - what could he hope for, as he was considered the Duke ‘s murderer.

This was a blemish he tried to reject onto others; in 1823, he published his Memoirs regarding the catastrophe of the Duke of Enghien and proved the fault was on Talleyrand- who retaliated with a skillfull press campaign. Talleyrand won, and the Duke of Rovigo was retired at age 49.

In 1828, Savary published his Memoirs to serve the History of Emperor Napoleon; it was a success. The next year, he left France for Rome and Italy.

His wife being friendly with Louis-Philippe’s Minister of Foreign Affairs,Savary went back to France. He participated to the conquest of Algeria, and his repression stunned even the Army.

He died in Paris the 2 June 1833, and his politics in Algeria were condemned by a Commission d’Enquête Parlementaire the next month.

He was undoubtedly devoted to the Emperor, but the d’Enghien Affair was always a millstone around his neck; he never recovered from how ridiculed he had been by Malet’s attempted Coup d’Etat; and finally, the brutality of his policies, making Fouché look good, ensured his unpopularity.

12 notes

·

View notes