#rhodesian civil war

Text

Making movies about real tragedies is always a difficult undertaking. No matter the pains you take to be as sensitive as possible, it's inevitable that such a touchy subject is going to anger SOMEONE. This doesn't even take into account the times that you, as a hypothetical filmmaker, will actually mess up for real. Nevertheless, director Paul Greengrass set out to tackle the Irish Troubles-- by no means an uncomplicated subject --in his film Bloody Sunday, a piece of cinema that tackles tasteful portrayal of the Bloody Sunday massacre by putting you in the crowd.

When we talk about how using cameras to communicate affect in cinema, handheld is one of the simplest mechanics for getting the audience to feel present in a film. It's why the crowd shots in Pi or the Goodfellas club scene or even the Evil Dead DemonCam work so well. This is essentially first person POV, and even when it isn't directly so, we feel like we're there with the characters, protesting on the streets of Derry against internment at the hands of the British. Greengrass uses handheld camera effectively, eschewing the newsreel perspective in favor of camerawork that felt more like the handheld camcorder footage used to film the 9/11 attacks on the twin towers just a year before the release of this film. He pulls you directly into the narrative. You're as much of a witness to the violence as the reporters documenting the Derry protests or the commanding officers giving the order to send in the Paras.

This brings us to the way Greengrass edits the film. The footage in Bloody Sunday rarely cuts, instead fading to black and then fading in the next shot. It feels almost like archival footage, the fades cutting off characters mid-sentence before taking us to the next segment of the film. This technique isolates the shots, but it heightens our awareness of how these discrete places and people (The British Paratrooper squad, Irish Nationalist politician Ivan Cooper, Major General Patrick MacLellan) all led up to the massacre.

It reminds me of working on my own films and logging footage. Each clip stringing together in a vacuum, telling a story without the invisible hand of narrative shaping perception through crossfades and transitions. Until the shooting starts, and Greengrass organically moves into a seamless, breathless sequence in which the Paras start shooting and the crowd scatters. It feels like you're there, and I noticed my blood pressure raise at the injustice unfolding onscreen. Incredibly effective filmmaking here, and the intentional camerawork does an impressive job at bringing the audience into the events of Bloody Sunday without the feelings of voyeurism often present in cinema about human suffering.

Bloody Sunday is, in my opinion, an elegant portrayal of a tragic landmark in the Irish Troubles. It's a film that impacted me emotionally, elevating my heartrate at the injustice unfolding onscreen. The British Government still shields David Cleary from prosecution for the mass killing, with legal repercussions for anyone who refers to him by his real name instead of "Soldier F," making clear the need for us to remember these atrocities perpetrated in the name of imperialism.

#filmposting#bloody sunday#paul greengrass#film#cinema#really liked this one#greengrass still got flack for it btw#people said he focused too much on civil rights leaders and military command instead of the people in the crowd#which I get but also thats a lot of territory to cover for a film that's only so long#the camera in the crowd bits can only go so far and its definitely easier to focus on public figures who have more documentation about them#good movie though#definitely should be on your list#also the paras wear Denison smocks which I realize were a connection to the rhodesian brushstroke#the rhodeys were big paratroopers during WWII and would've had access to these smocks#if you look at rhodey brushstroke its basically portuguese lizard mixed with the Denison smock pattern#fascinating really how the cultural influences mix#also made the paras seem that much more evil as they seemed to be wearing the uniform of a colonial ethnostate while doing a colonial war#I think at least one of the para smocks was taken from rhodesia bc it looked too crisp to be pat59 denison#but maybe it was just a repro

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wikipedia's article for the Zimbabwean War of Independence is really bad. For starters, it insists on being titled "The Rhodesian Bush War", which is like if the article for the American Civil War was titled "The War of Northern Aggression". It is an explicitly partisan name, and one partisan in favour of the white supremacist faction.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

This series is shaping up to be about covert attempts by institutional power structures to undermine the health and safety of the international working class. The previous part, Part 4, is here. You can find a cool easter egg by seeing who the magazine in the bottom right image was delivered to.

The above is a dossier compiled by a right wing business intelligence group and purchased by the CIA not long after the events I’m about to share occurred. It is hosted on the CIA’s website for declassified files, the Reading Room. It was prepared by Fulton Lewis III, an outspoken supporter of the Rhodesian government and the son of a Hearst-sponsored anti-communist radio broadcaster, sort of the Tucker Carlson of the 40s and 50s. We don’t have the CIA’s own assessments because those are still classified.

When we last left the crew of the spaceship Ramparts, they were dealing with infiltration, incompetence, hedonism, an inability to secure funding, and the heady addiction of fame. Things were about to get worse as their own interpersonal disputes had come to the fore. Keating had seen his power at the magazine get whittled away as incentives in the form of shares for other backers became necessary. At the time, Hinckle counted among his friends Howard Gossage, an advertising whiz kid who helped popularize Marshall McLuhan and did the Sierra Club's first campaign. He frequently went to Gossage for advice. The two came up with a plan to push Keating into the 1966 Democratic primaries for the 11th district of California (later held by Leo Ryan, a CIA critic killed at Jonestown, and now held by Nancy Pelosi) as a way of reducing his influence on the day to day operations of Ramparts. In the midst of a meeting, they had two staff members slip away and come back with signs that said "Keating for Congress" and "Keating the people's choice".

By the start of 1966, however, the election bug had spread through the offices, both because it allowed Ramparts to make the news it reported on as salacious as possible, and because the Democratic Party had largely denied ballot access to anybody who was anti-Vietnam War. Bob Scheer, the foreign editor, ran in Oakland, and Stanley Sheinbaum, the Michigan State University professor who'd exposed the CIA's role on campus, ran in Santa Barbara. All gained 40-45% of the vote, mainly by cohering those opposed to the war. One thing in particular all three did was bring together the black vote (for instance, Julian Bond, mentioned previously in the series, campaigned for Scheer). Their campaigns were run by a coterie of Ramparts staffers, namely CPUSA member Carl Bloice as well as Berekeley lecturer Peter Collier, and were endorsed by a combination of black and Hollywood luminaries, for instance Dick Gregory, the civil rights activist and stand-up comedian, and Robert Vaughan, Napoleon Solo on the Man from Uncle and both a murderer and a victim on Columbo (see him argue about Vietnam on Firing Line with William Buckley here). Some of the opposition research on the three came directly from CIA files and was given to the establishment candidates by LBJ's press secretary Bill Moyers.

youtube

With the elections lost, Ramparts needed a new spin on things to bring back all the anti-electoral politics radicals. Fortunately, in nearby Oakland, a new group had just been founded called the Black Panther Party. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale like to portray their group as their own innovation, two upwardly mobile college kids shooting the shit late at night. The group they'd been part of prior to the BPP, the Maoist Revolutionary Action Movement, described them as "adventurists" for their desire to put theory to practice and finally organize in the community instead of just talking about it. Whatever the case, Newton learned from Robert Williams' Negroes with Guns that California law, influenced by white supremacist vigilanteism, allowed anyone to openly carry a weapon even in the presence of police. He went to Chinatown, bought copies of Mao's Little Red Book for cents, and sold them for dollars in Oakland as part of a course in organized self-defence, then used the money to buy shotguns and M-16s for use by graduates of the course. By February 1967, Ramparts staff writer Eldridge Cleaver had made contact at a speaking event for Malcolm X's widow Betty Shabazz, where the Black Panther Party founders and their cohort were the only ones armed. Cleaver invited them to the Ramparts offices for a sit down.

Remember the bit from the last part about Shabazz' bodyguards? That was Seale, Newton, and Co. Their arrival caused Hinckle's police buddies to get worried, and they put out an APB and surrounded the building, much to Newton's consternation. Hinckle suggested they go out for a drink, but nobody was buying it. Newton stared down a cop, who undid his holster. Seale put his hand on Newton, who told him off. "Don't hold my hand, brother." Seale released it, because that was his shooting hand. Newton taunted the officer. "You got an itchy trigger finger?... OK, you big, fat, racist pig, draw your gun!" All the Ramparts' staffers who'd come to watch as well as the officers' backup got the hell out of Dodge. Eventually, even the officer backed down. It was the first time the BPP had ever gotten the police to back down. It brought admiration from the entire Ramparts staff, who soon made the magazine the semi-official outlet of the BPP. And it brought Cleaver into their fold. They appointed him spokesman/Minister of Information within weeks. The following is the only news footage from that day shot after the incident, the rest having been lost, with Scheer in the background at one point:

youtube

And that wasn't even the most shocking thing going on at Ramparts. This series has previously mentioned the National Student Association as a bunch of debate nerds who essentially trained to have public speaking and organizing on their resume for future employers. The thing about the NSA was, it was a CIA front, and generally suspected as such. In 1947, there was an implosion of student politics' international facing groups. Those who had seen the Soviets fight in the Second World War generally accepted their claims to want world peace on their face, while the groups aligned with the Catholic Church teamed up with disparate right wing WASPs and Jews to fight back. The CIA had taken these students (to note, these were largely men in their late 20s or early 30s, grad rather than undergrad) under their wing and organized them into a front group that could report back on invitational events held in Eastern Europe. In turn, the top echelons of the NSA had to be sworn into legal secrecy as a prerequisite of participation, with the reward being entry into the old boys network of politicians and bureaucrats which virtually guaranteed a job.

The CIA fucked up. In 1965, the elected president of the NSA was Philip Sherburne. He was sworn into secrecy on the source of funding for their new HQ and general operations, as was normal for the group. But he disliked that they had only one source of funding, and he wanted the NSA to be independent. At the time, the grassroots in the organization who followed international politics and hewed to the left had managed to get some of their membership into power, but they had felt straitjacketed by the CIA's complete control of NSA finances. Many wanted to join in on the anti-war marches. Sherburne and others, spurred on by abrogation of Juan Bosch's regime in the Dominican Republic and the electoral fraud that brought the American-backed opposition to power, worked to find alternative sources of funding. They sent one an NSA man as part of the operation, but he got cold feet and worked with Sherburne to expose it. In response, the CIA had a number of top NSA men declared eligible for the draft in Vietnam. Bureaucratic fights ensued, involving the lives of students in America, Spain, Vietnam, and elsewhere. Finally, Sherburne went above the CIA's head to vice president Hubert Humprhey. In response, the CIA went and cut all of Sherburne's independent lines of funding. Unbenkownst to them, Sherburne had made a relatively radical student named Michael Wood his outside line to donors. He'd told Wood not to approach certain groups because they were backed by "certain government agencies". Wood had surmised that this meant the CIA and gone and picked up the only book out on the Agency: The Invisible Government, by David Wise and Thomas Ross. When he saw that the NSA's funding for 1966 had the same donor groups backed by the CIA, he realized Sherburne had lost and stole the files.

Twice the New York Times had published articles critical of the CIA in some form. In 1965, Texas congressman Wright Patman, initially elected on his support of the Bonus Army and ever a thorn in the establishment's side, had investigated 8 charitable foundations and found them to be CIA cutouts. The NYT had written an article on this as well as replies from the funded orgs (Encounter Magazine and the Congress for Cultural Freedom). In 1966, spurred by Ramparts' articles on MSU, NYT reporter Tom Wicker wrote of the allegations and added details of other botched operations around the world he'd heard from sources over the years. This brought the ire of the agency. In 1961, in response to details of the Bay of Pigs invasion being published in The Nation before it occurred, President Kennedy told his aides to bother him when details showed up in the New York Times because it otherwise did not matter. The CIA had actually worked hard to kill the very same story before the NYT could publish it so by the time the invasion failed, Kennedy apparently exclaimed that he wished more details had been published in the NYT so that the invasion would have been stopped. CIA agent Cord Meyer made the postscript of Part 3 of this series as the handler of much of the CIA's work through cutouts and allied groups like AFL-CIO, especially in in regards to the effort to influence the media known as Operation Mockingbird. Meyer and his wife, Mary Pinchot, were next door neighbours to the Kennedy's before JFK became president. Pinchot divorced Meyer after their child was killed in a car accident in 1957. She moved in with her brother-in-law, Ben Bradlee, later of Pentagon Papers and Watergate fame and played by Tom Hanks in the Steven Spielberg film The Post. In 1961, James Jesus Angleton, head of counterintelligence at the CIA, tapped her phone and discovered she was in a sexual relationship with JFK, including visits at the White House. When Pinchot was murdered in October 1964 in what was termed a robbery (a black man was arrested but acquitted), a friend of the family heard (he said) about the murder on the radio and phoned Bradlee first and Meyer second. Bradlee went to go find her diary and found Angleton sitting in her house (his garage) reading it. They later destroyed it. After that, Meyer became an alcoholic and compiled an enemies list of the CIA that included the Vice President. He was already fearful of a leak and told his subordinates to go after NSA staff but did not determine who Sherburne had told until his wiretaps of Ramparts phone lines informed him.

Ramparts, of course, knew that they had been tapped and kept phone calls brief. Scheer phoned Judith Coburn of the Village Voice and asked for her discretion. Wanting to break into a field dominated by men, Coburn felt like she was being called by a rock star, but nonetheless found it absurd that Scheer believed his calls to be tapped. She knew the CIA to be involved in assassinations like Lumumba's and thought their dealings with a minor org like the NSA were absurd. Ultimately, she helped by confronting a number of figures on their work. Eventually, a young WASP Harvard undergraduate who was on retainer from Ramparts named Michael Ansara got the call. His blog about it is excellent reading, located here. I quote:

One evening in the cold months of early 1967, my phone rang. A strange voice, obviously from New York asked, “Is this Michael Ansara?”

“Yes.”

“This is Sol Stern from Ramparts. Bob Scheer says you are our man in Boston.”

“Well . . . OK.”

“Listen I need you to do some work for us right away. I cannot tell you what it is about. I am calling you from a phone booth. Will you do it?”

“Well, what kind of work and are you willing to pay me for it?”

“It is research into two Boston based foundations. We will pay you $500.” 500 dollars was a lot of money. I had no idea how to research foundations, but I thought, what the hell. I could really use the money.

“Sure. What exactly do you want me to do?”

“I can’t tell you anything more than to find everything you can on the Sidney & Esther Rabb Foundation and Independence Foundation. They are based in Boston. I will call you in several days. You cannot call me. You cannot tell anyone what you are doing. You cannot mention the name Ramparts. Can I count on you?”

“I guess so. Sure. Yes.”

Ansara knew a much older man, an economist and lawyer who had sway in the Democratic Party named George Sommaripa. Sommaripa suggested Ansara go to a guy he knew at the IRS. Ansara did, and was told that under no circumstances could he have access to the files on two CIA cutout foundations. Chastened, Ansara complained to Sommaripa, who'd gotten the IRS clerk his job. A few days later, Ansara went back. The IRS clerk told him he could have any box he wanted, provided he did not go past the 990 form on the cover. He went past for the first two foundations and found that money came from an anonymous donor and in equal amounts went right out to the NSA. Ultimately, he pulled the files for 110 foundations, every single known group that the CIA used. He would look at the incorporation files for the foundations, see a lawyers' name, and look him up. Every time, the lawyer was an OSS operative during WW2, the predecessor org of the CIA. One of the lawyers had founded a firm with Sommaripa, a man named David Bird. Ansara confronted Bird, and Bird did not even stop to hang up on Ansara before phoning a contact at the CIA.

Left to right: Hinckle, Stern, Scheer.

A major corroboration of the story came from three students in New York who were disgusted by American foreign policy in Latin America. One in particular, Fred Goff, had been sent to the Dominican Republic with Allard Lowenstein (part 3) to observe the election of the pro-American candidate over the anti-American one. Goff had discovered that a man that Lowenstein had said he trusted on the country was actually a CIA agent, Sacha Volman. Another, Michael Locker, had done a paper about the CIA based on the NYT articles. Together, they walked in the doors of the AFL-CIO's American Institute for Free Labor Development and asked directly about the CIA, prompting a crashing sound and the institute's director, Thomas Kahn, planner of the 1963 March on Washington and the long-term romantic partner of Bayard Rustin, to scream at them.

The problem was when it came time to do the story. Sometimes, the researchers were paid by Ramparts. Other times, they received cheques from the Interchurch Center, a strange agency that serves as a front for charitable giving from the Episcopal, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Reformed, Methodist, and United Churches in America. James Forman, mentioned in previous parts, once led a picket in favour of reparations from them. Ramparts staff demanded they talk to them by picking up pay phones that would ring at designated times, a dismal failure. Other times, Hinckle, Scheer, and Sol Stern would fly in, book rooms at the Algonquin, and order massive amounts of takeout and booze. 15 to 20 people would be in a hotel room trying to negotiate who would be writing the story by continent, or by year, or by foundation. At one point, Coburn broke into the NSA HQ and unwittingly stole the original deed to their land, where it remained undiscovered in Ramparts' files till the 2010s.

On New Year's Eve, 1966, Lowenstein was hanging out with the new members of the NSA leadership when he informed them that Ramparts was writing about their relationship with the CIA. "The usual sloppy Ramparts piece, lots of flash, little substance," he said. The CIA had known since at least Thanksgiving. A lower level NSA official who'd just been sworn in went to meet with Hinckle and Scheer. The duo, while nonchalantly throwing darts, offered the Ramparts donor list as an incentive to tell all, but he refused. Sherburne attempted to find counsel in a lawyer who'd once opposed the CIA's new Langley HQ on NIMBY grounds. Meyer had threatened the lawyer's brother, working in Bogota with USAID, but the lawyer persisted. Undaunted, Meyer got word to Douglass Cater, the first president of the NSA and now an advisor to LBJ. LBJ bumped it to Lowenstein and the CIA to develop a response, which was to hold a press conference with an article in Henry Luce's (the man, not the monkey) Time Magazine that this was all well known since the 1965 congressional hearings, that the money was not that impressive, that the Soviets had done much more, etc.

This could have killed Ramparts. The IRS was already looking for any sign of foreign influence as an excuse to shut down the magazine. It needed some sort of relationship with the establishment press in a way that would let it gain influence without keeping it from the areas it wanted to report on. At the very same time, both Time and the NYT were reporting on the survival of Ramparts: Keating had attempted a coup and lost a board vote 13-1, with Mitford and other backers providing anonymous quotes that while they disliked the "Animal Farm-ish" nature of the issue, they needed Ramparts to stave off a fascist dictatorship in America. Hinckle followed by setting up an astounding agreement with the New York Times and Washington Post: they would get full access to Ramparts' files on the CIA right now, before the White House could set up a press conference, in exchange for letting them run full page ads for days for their next issue.

The day the Times went to press, February 13, 1963, was termed by former CIA director Richard Helms in his memoirs as "one of my darkest days". The press pushed, smelling blood. President Johnson ordered a suspension and review of CIA funding for outside orgs. The CIA initially tried to find a way to blame a dead president, Truman, but realized that its own documentation on the program, written by Cord Meyer, claimed that then-director Allen Dulles did not have any responsibility to inform the president of what he had ordered. Switching tactics, they turned on their press weapon, known as the Mighty Wurlitzer, and claimed that the CIA would have been remiss to not conduct these operations. "I'm glad the CIA is immoral" was the headline of an article by Meyer's boss, Thomas Braden. He described $250 million a year the CIA believed to be spent by the Soviet Union on cultural subversion, to which a mere handful of dollars from the CIA could not compare. No evidence for the accusations was provided, of course. Finally, Helms pulled in a favour from Robert Kennedy and had him testify to the press that his brother had authorized the funding, carried over from the days of Eisenhower. 12 former NSA presidents (including Lowenstein) came out and said the relationship was above board. All had worked for the CIA at least once after they'd left the NSA, but that was not revealed in their letter.

The strategy was a half-success. All the foundations funded by the CIA fell apart and students around the world became suspicious of CIA infiltration. Much of what Ramparts found was investigated by Congress repeatedly over the next decade, culminating in the reforms that came out of the Church Committee, which Helms claimed in his memoirs was sparked by Ramparts and Watergate. Certainly press readership was high, and many stories were published in the NYT and WaPo confirming and furthering the work done. At the same time, the CIA escaped with only a few new rules on its behaviour. President Johnson was a paranoic and was more concerned about using the CIA as a tool against his domestic enemies. He authorized a much larger role for MHCHAOS in punishing his enemies (remember the cryptonyms? MH was the most illegal, as it meant the USA). Many of those fingered were considered liberals in good standing and were part of the labour movement, particularly AFL-CIO higher-ups. They fell in line with the rhetoric about communist subversion because they knew they'd be the ones punished if things went further.

Interestingly, a few months later, the NSA held a vote on integrating an anti-Vietnam War and anti-draft stance into its platform. Traditionally, the CIA had worked from the shadows to suppress these votes. This time, Allard Lowenstein whipped in favour of the anti- stance and it won. Lowenstein soon became a fixture in the anti-LBJ movement, leading the call to bring Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy into the Democratic presidential primaries. To a large extent, the organizations that were closed to the CIA had been products of decades-old relationships and worked in ways that nobody had bothered to improve. Within the CIA, a tension had always existed between bureaucrats with their own fiefdoms and up and comers with new ways of doing things. To a large extent, this scandal simply pushed the former out and made room for the latter, who would not do things like create financial records with the exact same dollar amounts going in and out, or act so bluntly when it came to manipulating staff. While the CIA may have suffered a little in the short term, it was an act of "creative destruction" that improved how the CIA did business. For Ramparts, on the other hand, things were going to get much worse now that they had drawn the ire of the intelligence community. While the magazine reached its peak distribution of 250,000 copies a month, it still did not bring in enough money to cover its expenses, and it was about to be faced with a much larger funding crisis: the Six Day War.

AFTER ALLEN DULLES RETIRED, the director bragged about the NSA operation. “We got everything we wanted. I think what we did was worth every penny. If we turned back the communists and made them milder and easier to live with, it was because we stopped them in certain areas, and the student area was one of them.”... Edward Garvey, who also worked at CIA headquarters, puts it more dramatically: “My God, did we finger people for the Shah?”... Stephen Robbins, despite his limited CIA involvement during his year as president, echoes Garvey’s concern: “It’s South Africa that keeps me up at night.”

#i am finding that i am including way too much information yet the details haunt me enough to make me put it in#i guess ramparts gets yet another part

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Africa" a song by Toto

This song performed by the American rock band Toto, was released in 1982 as part of the album Toto IV and became an immediate success reaching the first position on the Billboard Hot 100. The song was written by keyboardist David Paich and the drummer Jeff Porcaro. There are different interpretations of it: there are those who say that it is about a missionary waiting for his beloved who flies to the African continent, others say that it is about a social activist who loves Africa, others relate it with a more introspective meaning and personal connection, etc., whatever the interpretation that each person gives it, there is no doubt that this song penetrates the depths of our being provoking strong feelings. Its singular melody conveys the sensation of magic, happiness, nostalgia, a comfort that transports those of us who listen to it to a beautiful place, imagining a free landscape full of exotic flora and fauna, but which, after all, we do not know; it's a far away place. The music video shows a researcher in a library who, searching for the image of a shield, finds a book titled Africa, in that moment a native throws a spear (the shield the native carries is the same as the one in the image) knocking down stacks of books and starting a fire. The depiction of the song in the video gives the sense of a reference to the Rhodesian civil war, from the perspective of a Rhodesian Security Forces soldier. Whatever was the message that it wanted to convey, "Africa" has managed to position itself as a hit in musical history, still sounding strong in the new generations, which is demonstrated in the recent use of the song in series or programs such as Stranger Things, South Park and The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, as well as new interpretations such as the cover made by Weezer in 2018. Without a doubt, "Africa" has become a milestone in popular culture, transcending time and our hearts.

-Leslie Canales Quiroz

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Rhodesian Air Training Group

Motto: Tica Simba Nezana- "Strength will come to us through our fledgelings."

The Rhodesian Air Training Group was a Royal Air Force (RAF) training unit and base for Allied and commonwealth pilots to train in africa in Rhodesia, (modern day Zimbabwe).

Before WWII even started the British Air Ministry had begun planning to set up air training centres outside Britain; away from where there was air activity over the country and where the weather could be relied upon to be consistently good. Canada was the first country to be first chosen, the scheme being called the Empire Air Training Scheme. Ultimately the countries involved in training aircrew comprising pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, air gunners, wireless operators and flight engineers included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Southern Rhodesia and the United States. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, the facilities in Rhodesia for air training were too small to be of any assistance to the Royal Air Force (RAF) Major D. Cloete, M.C., A.F.C. had been charge of a small air training scheme from 1937 of two RAF Officers and twelve other ranks who were seconded to Rhodesia with four Audax and six Hart aircraft and based at Hillside (later renamed Cranborne) but they only trained local Rhodesian territorial forces and personnel from the Rhodesia Regiment. In 1938 the unit was separated from territorial force and on May 12th, 1938 the Governor, Sir Herbert Stanley, presented the first seven Rhodesian flying badges at a parade at Hillside. There was an agreement that, in the event of war, Rhodesia would send an air unit to Kenya for service with the RAF and accordingly three Audax and three Hart aircraft were despatched on August 28th, 1939, six days before the actual declaration of war.

Lieut.-Col. C.W. Meredith arrived in Rhodesia in June 1939 as Staff Officer Air Services and Director of Civil Aviation. The British Air Ministry were very interested in expanding the air training into a much larger program as they wanted most, if not all, air training out of England and to involve the training of other allied personnel as well as Rhodesians. It was decided to start off in Rhodesia with one initial training wing through which pupils would pass on to three Elementary Flying Training Schools (EFTS) and matching them, three Service Flying Training Schools (SFTS) The establishment of six new Air Stations required a considerable amount of building, all of which had to be done using local resources. In Salisbury (now Harare) the EFTS was at Belvedere, with the SFTS at Cranborne; the second pair of schools would be established at Bulawayo (Induna and Kumalo) with the third pair at Gwelo (Guinea Fowl and Thornhill). At this early stage in January 1940, Meredith’s staff consisted of two territorial officers who had joined at the outbreak of war for administrative duties, and a typist. Initially RATG headquarters were based in the Salisbury suburb of Belvedere and with a heavy building program ahead, the immediate need was for staff to cope with layouts, design and construction of airfields and hangers, supplies of building materials and finance and accounting. At Cranborne total strength of the air station was 137 officers and other ranks with 16 aircraft available for training. These comprised four serviceable Harts, one Audax waiting rebuilding, eight serviceable Tiger Moths and one being repaired, and two Hornet Moths.

Major C. W. Glass MC, an architect by profession, was released from his civilian employment with the Public Works Department and agreed to transfer with the rank of Squadron Leader, later Wing Commander, with the title of Director of Works and Buildings. His Section was wholly responsible for the layout of Air Stations and the design and construction of buildings for whatever purpose. Later after building had been completed additional sections were added included air staff, air training, signals, armament, administration, equipment, engineering, personnel, medical and legal. In April 1940 the Rhodesian Air Force Training Scheme and the Empire Air Force training Scheme really began; but was known locally as the Rhodesian Air Training Group. In the same month the first draft of pupil pilots arrived at Belvedere and the air station was declared officially opened by Air Chief Marshall Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, in the presence of the Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins, E.L. Guest and C.W. Meredith. The first group graduated from elementary air school in July and by November 2nd, 1940 the first pilots to be trained by the RATG passed out at Cranborne air station, five of whom were Rhodesians. When war broke out in 1939 the Air Ministry employed the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) as the principal source of aircrew into the RAF and this continued into the 1950’s. In fact the programme was such a success that it soon was realised that the Rhodesian Air Training Group could become vital to the war effort for training aircraft personnel and although the bulk of the trainees were British, they also received Greeks, Yugoslavs, Australians and South Africans. Ezer Weisman, later to be President of Israel, trained as a pilot in Rhodesia. RAF training units would still be based in this country until a decade after WWII had finished.

The war time Elementary Flying training School (EFTS) gave a recruit 50 hours of basic aviation instruction on a simple trainer, such as the de Havilland Tiger Moth. Pilot cadets who showed promise went onto training at a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where they were awarded their “wings.” The SFTS provided intermediate and advanced training for pilots, including fighter and twin-engined aircraft, on the North American Harvard and Airspeed Oxford aeroplanes. Other trainees went onto different specialities, such as wireless, navigation, or bombing and air gunnery. The next air station to come into operation was at Guinea Fowl, Gwelo (now Gweru) in twelve weeks from bare veld to the commencement of flying training. Its construction included provision of water supplies, water-borne sewerage and building a rail siding for the special trains bringing aircrew from Cape Town. To relieve congestion at the air stations, six relief landing grounds for landing and take-off instruction were established. Two aircraft and engine repair and overhaul depots were set up and a central maintenance unit to deal with bulk stores of aircraft. In late 1940 it was decided that Cranborne and Thornhill would be used to train single-engined pilots, or fighter-pilots, and Kumalo and Heany air stations would train twin-engined pilots.

At its peak there were about 12,000 adult male white personnel and about 5,000 adult male Africans employed. There were also about 200 white women in the Women's Auxiliary Air Service who were employed in post offices and on clerical duties at various stations. A Rhodesian Air Askari Corps was formed under Wing Commander T. E. Price to provide armed guards and non-armed labour. From the May 1940 until the March 1954 the Royal Air Force (RAF) had a presence in Rhodesia in the form of the RATG which trained aircrew for the RAF, from many different countries, including Great Britain but also from Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, USA, Yugoslavia, Greece, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Fiji and Malta as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme. On November 27th, 1947 after the wat the Southern Rhodesian Air Force (SRAF) was re-established as a separate unit and from that date until RATG closed, both the RAF and the SRAF took to the skies above Rhodesia. The beginning of the Cold War brought a renewed need for aircrew training; the RAF re-vitalised the Rhodesian Air Training Group (in May 1948) which continued to grow with the Korean War, although nothing like its WWII level.

Today there are almost no memorials monuments and plaques within Zimbabwe to mark the great efforts and personal sacrifices that were made by African and European servicemen and women and civilians to the Allied cause during the World War. However the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) does an outstanding job in commemorating those who lost their lives for their country and are buried within Zimbabwe.

#second world war#world war 2#ww2#wwii#rhodesia#zimbabwe#aircraft#air force history#royal air force#african history#military history#aviation#British Commonwealth#allies

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pioneers may be picturesque figures, but they are often rather lonely ones.

- Nancy Astor, the Viscountess Astor

Nancy Astor was an American-born British politician who was the first female MP to take her seat in the House of Common. Viscountess Astor had won the constituency of Plymouth Sutton in 1919, and after Irish Sinn Féin’s Constance Markievicz had refused to take her seat the previous year, became the first woman to sit in the House. So in effect Astor became the second female Member of Parliament but the first to take her seat, serving from 1919 to 1945.

Nancy Witcher Langhorne was born in 1879 in Virginia to a prosperous railroad businessmen.

Following the American Civil War, prosperous Southerners who had relied on slavery fell on hard times. Such was the fate of her father, Chiswell Dabney Langhorne, who had been a successful railroad businessman before the war. So when Nancy, his eighth child was born on May 19th, 1879 he was still struggling to recover. However by the time that daughter, who had been christened Nancy, was thirteen, he had re-established his fortune.

Nancy Langhorne had four sisters and three brothers who survived childhood. All of the sisters were known for their beauty; Nancy and her sister Irene both attended a finishing school in New York City. She finished successfully and in 1897.

In New York Nancy met her first husband, a wealthy socialite Robert Gould Shaw II, a first cousin of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who commanded the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the first unit in the Union Army to be composed of African Americans. They married in New York City on 27 October 1897, when she was 18.

The marriage was an unhappy one. For Nancy it was not such a success, since she left her husband for the first time during their honeymoon and after a turbulent and troubled four years and a son, they separated permanently.

Nancy Shaw took a tour of England and fell in love with the country. Since she had been so happy there, her father suggested that she move to England. Seeing she was reluctant, her father said this was also her mother's wish; he suggested she take her younger sister Phyllis. Nancy and Phyllis moved together to England in 1905. Their older sister Irene had married the artist Charles Dana Gibson and became a model for his Gibson Girls.

Nancy Shaw had already become known in English society as an interesting and witty American, at a time when numerous wealthy young American women had married into the British aristocracy. Her tendency to be saucy in conversation, yet religiously devout and almost prudish in behavior, confused many of the English men but pleased some of the older socialites.

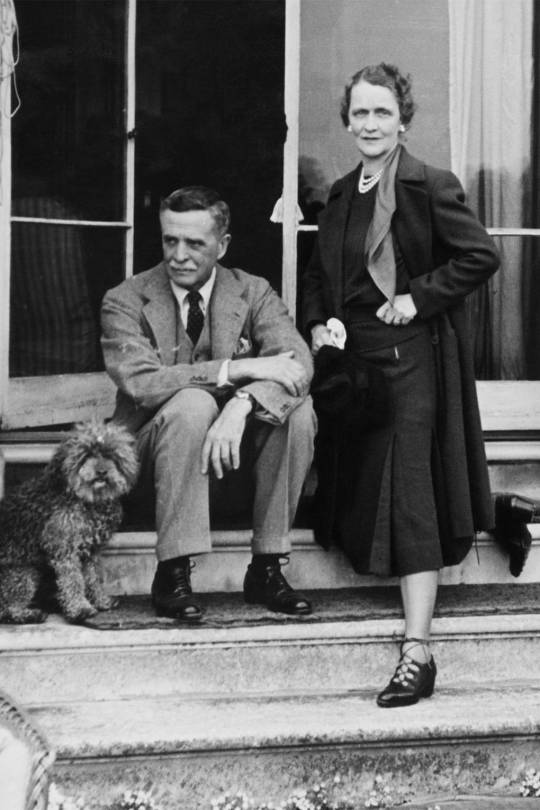

She did marry an Englishman, albeit one born in the United States, Waldorf Astor - 2nd Viscount Astor, an American-born English politician and newspaper proprietor.

While crossing the Atlantic to Britain, Nancy had met Waldorf Astor, the son of the American magnate William Waldorf Astor. Waldorf had been born in New York on the same day as Nancy, but when he was ten years old his father had moved the family to Britain to raise his children as English aristocrats. Waldorf had been educated at Eton College and Oxford University. In May of 1906 Nancy and Waldorf were married and moved into their wedding gift – the 375 acre Cliveden Estate and its 400-foot-long mansion in Buckinghamshire, which Nancy modernised and had electrified.

The Astors moved into Cliveden, a lavish estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames that was a wedding gift from Astor's father. Nancy Astor developed as a prominent hostess for the British social elite.

The Astors also owned a grand London house, No. 4 St. James's Square, now the premises of the Naval & Military Club. A blue plaque unveiled in 1987 commemorates Astor at St. James's Square. Through her many social connections, Lady Astor became involved in a political circle called 'Milner's Kindergarten’. Considered liberal in their age (but in reality very conservative), the group advocated unity and equality among English-speaking people and a continuance or expansion of the British Empire inspired by the vision of Cecil Rhodes.

Nancy encouraged Waldorf to enter politics and he became a Member of Parliament in 1910 for the Conservative Party, although he broke ranks with his party and tended to vote for social reforms. When his Liberal friend David Lloyd George became Prime Minister of the wartime Coalition government in 1916, Waldorf became his parliamentary private secretary and part of his circle of advisors. In 1916 his father William was made a peer - Viscount Astor. When William died in 1919, Waldorf tried unsuccessfully to avoid taking the title, but was forced to surrender his seat in Parliament and enter the House of Lords as the 2nd Viscount Astor.

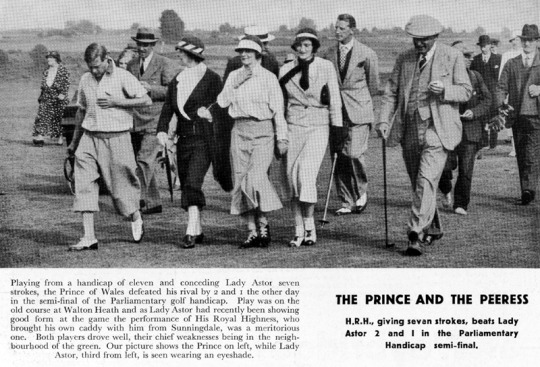

This triggered a by-election for his Plymouth seat, which Nancy contested and won. Women had only recent been granted the right to vote. Her American informal style was new to the British and seems to have charmed them in an age where campaigning was very much about personality.

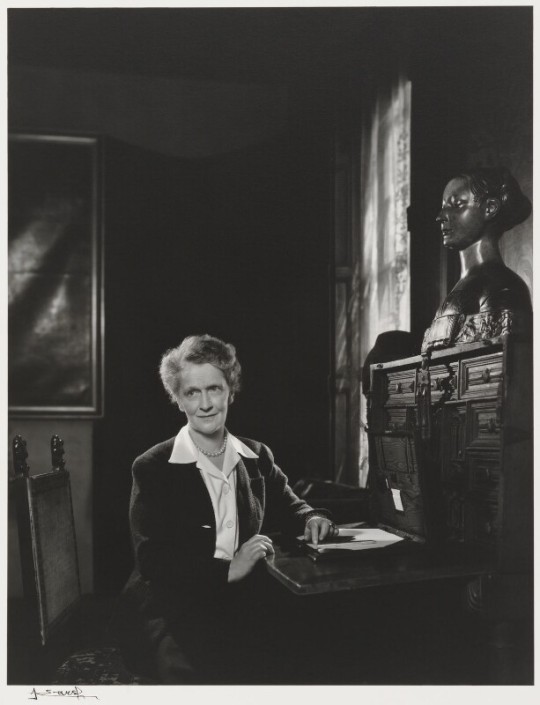

Nancy Astor was a very remarkable woman: determined, witty and accomplished. She was also the beneficiary of considerable privilege, through birth and marriage - none of which is generally looked on with forgiveness in our age.

Her sharp wit hid a cold, aggressive, paranoid and illiberal personality.

She also clashed with her contemporary, Sir Winston Churchill and there’s a famous exchange between the two that goes along these lines “Winston, if I were married to you I’d put poison in your coffee”….”Nancy, if I were married to you I’d drink it.” This supposedly occurred during a weekend house party at Blenheim Palace in the early 1930s.

Nancy Astor's accomplishments in the House of Commons were relatively minor. She never held a position with much influence, and never any post of ministerial rank, although her time in Commons saw four Conservative Prime Ministers in office. The Duchess of Atholl (elected to Parliament in 1923, four years after Lady Astor) rose to higher levels in the Conservative Party before Astor did. Astor felt if she had more position in the party, she would be less free to criticise her party's government. She did gain passage of a bill to increase the legal drinking age to eighteen unless the minor has parental approval.

During this period Nancy Astor continued to be active outside government, supporting the development and expansion of nursery schools for children's education. She was introduced to the issue by socialist Margaret McMillan, who believed that her late sister helped guide her in life. Lady Astor was initially skeptical of this aspect, but later the two women became close; Astor used her wealth to aid their social efforts.

Left out of the boy’s club within the all male atmosphere of Parliament, She worked hard instead to use her wealth and influence to recruit women into the civil service, the police force, education reform, and the House of Lords.

Lady Astor chaired the first ever International Conference of Women In Science, Industry and Commerce, a three-day event held London in July 1925, organised by Caroline Haslett for the Women's Engineering Society in co-operation with other leading women's groups. Astor hosted a large gathering at her home in St James's to enable networking amongst the international delegates, and spoke strongly of her support of and the need for women to work in the fields of science, engineering and technology.

Her legacy though remains very controversial as she was intimately bound to the upper-class appeasement movement of the 1930s. She was a fierce anti-Communist and like many others saw the rise of Germany as a bulwark to thwart the Bolshevik menace.

Astor was critical of the Nazis for devaluing the position of women and opposed the idea of another war. But as Harold Nicholson (among others) noted in his diaries, she was perfectly willing to indulge in the kind of ugly, reflexive anti-Semitism that was thought to be “clever” in aristocratic circles in those days. She exchanged anti-Semitic letters with the then American ambassador to Britain, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. and entertained prominent members of the Nazi government. She herself asserted she was not an anti-Semite; she said in 1947, "I'm not anti-Jewish but gangsterism isn't going to solve the Palestine problem".

When World War Two did break-out Nancy Astor admitted that she had made mistakes and supported the war effort, although still causing controversy by, for example, opposing the entry into Britain of Communist refugees at a time when Russia was an ally in the war.

As her views became more extreme and eccentric she became an embarrassment to the Conservative Party and with them facing defeat by the Labour Party in the 1945 election, Waldorf Astor was persuaded to force her to step down. She did, but with anger and bitterness which she continued to express for many years.

She and Waldorf drifted apart and his movement to the political left did not help their marriage. They began to live separate lives and travel apart, although there was a reconciliation before his death in 1952.

During the 1950’s she added racism to her other views and became notorious for, among other statements, proudly announcing to the white minority Rhodesian government that she was the daughter of a slave owner and telling a group of Afro-American students that they should be more like the servants of her southern childhood. As her brothers and sisters died and she became estranged from her children, loneliness took over.

Nancy Astor died in 1964.

A statue commemorating her life was unveiled in Plymouth in November 2019 by Prime Minister Theresa May - and her future successor Boris Johnson also posed by the statue of the former Tory MP. The unveiling was one way to commemorate the centenary of women being involved in Parliamentary politics in the UK.

Theresa May said at the unveiling: “For two years Nancy Astor was the only woman in a House which was not designed for women. A place of Honourable Gentlemen, somking rooms and no ladies’ loos. She ignored the jeering, the patronising and the bawdy jokes, and began to make the Commons an easier place for the many –but all to few – women who have followed her.”

The statue was the culmination of a popular public campaign started by Labour MP for Plymouth and Sutton and Devonport, Mr Luke Pollard. The campaign enjoyed cross political party support. All of Plymouth’s living former MPs were present at the unveiling - Alison Seabeck (now Raynsford), Linda Gilroy, Baroness Janet Fookes and Liberal peer Lord David Owen.

Prime Minister Theresa May said the whole country should be “proud of the great strides Nancy Astor made for equality and representation”. The inscription on the statue’s plinth reads: “Real education should educate us out of self into something far finer - into a selflessness which links us all with humanity.

In June 2020, her statue was placed on a target list of Black Lives Matter movement and other activist groups to campaign for its removal.

#nancy astor#lady astor#quote#aristocracy#britain#politics#statue#blm#protests#mixed legacy#femme#icon#churchill

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

swedebeast replied to your post “You do also have to remember this is a guy who refuses to admit that...”

-wakes up from a coma- hnnnrgh is sapper back again?

Yeah, pretty much. Claiming that the Rhodesian government was Apartheid so we shouldn’t think that an ex-South African soldier turned mercenary pilot who almost single-handled helped stop the advance of the RUF in the Sierra Leone civil war was a cool guy.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

Sudan Railways - Beyer-Garratt steam locomotive Nr. 259 being delivered new to Sudan in 1937 by Historical Railway Images

Via Flickr:

The Sudan Railways 250 class consisted of ten 4-6-4+4-6-4 Garratt locomotives. It was one of only two classes of "Double Baltic" Garratts, the other class being the Rhodesia Railways 15th class. The ten locomotives were built in two batches by Beyer, Peacock and Company in 1936–1937. They were the only class of Garratts on the Sudan Railways and were numbered 250–259. They were used on Port Sudan to Atbara and Atbara to Wad Madani routes, until they were made redundant by diesel locomotives. In 1949, they were sold to the Rhodesia Railways where they were numbered 271 to 280 and classified as 17th class. On the RR they were used alongside the 15th and 15A classes. In 1964 all ten locomotive were sold to the Caminhos de Ferro de Moçambique who numbered them 921 to 930. They were then used on the Beira railway from the port city of Beira to the Rhodesian (now Zimbabwean) border at Umtali (now Mutare). They were still in use into the 1980s, but post-civil war, their fate is unclear; they are presumed all scrapped.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Vietnam War had a further pernicious effect: it helped make possible the paramilitary expression of racist sentiment. In the first half of the 20th century the American far right had conducted a campaign of violence against blacks and others, especially in the South. But while they could rely on the support of large sections of society for their cause, their main aim was to instil fear rather than to try to realise fantasies of extermination or separatism. The capacity for more directed violence among white power groups that became evident in the 1980s would not have been possible without their Vietnam training and access to weapons stolen from military bases. Faced with an economic recession exacerbated by the war’s vast expenditures, many veterans believed they would never find ordinary employment, which led some to gravitate toward the fringes of American society both left and right.

John Rambo, for his part, did both. In First Blood (1982), Sylvester Stallone’s character is a ‘half-German, half-Indian’ veteran, traumatised by the war, who arrives in a small town to pay his respects to a black comrade killed by exposure to Agent Orange. Mistaken for a hippie grafter, he is hounded by the local police and struggles to find work: ‘There [in Vietnam] I flew helicopters, drove tanks, had equipment worth millions. Here I can’t even work parking!’ But in Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985), Rambo turns right, fighting the Vietnam War all over again single-handed. ‘Sir,’ he asks, ‘do we get to win this time?’

‘Bring the war home’: what began as an anti-war slogan on the American left was appropriated by the extreme right as a proclamation of intent. Louis Beam – one of the major strategists of the paramilitary right and a central figure in Belew’s book – was a decorated veteran who had logged more than a thousand hours as a door-gunner on Huey choppers. Back home he promptly joined the Louisiana chapter of the KKK, beginning a career that seamlessly combined white power fanaticism with anti-communism. In 1977, Beam received a grant from the state of Texas to build a simulated Vietnamese rice paddy in swampland near Houston: here, he trained recruits as young as 13 to kill an imaginary enemy. Four years later a promising opportunity presented itself. A number of South Vietnamese refugees had been resettled on the other side of Galveston Bay, and local shrimp farmers didn’t want the competition. Beam seized on these fears and gave a speech to a crowd of 250 white farmers. Shortly afterwards a group of them set out and burned two Vietnamese boats, torched crosses on their lawns, and patrolled the bay on a ship equipped with a small cannon and a mannequin hanging from a noose. The campaign of intimidation was ended by the Southern Poverty Law Centre, which won a court order to disband Beam’s group and close his training camps.

Crucially, as Belew shows, most American paramilitary groups in the years after Vietnam considered themselves vigilantes. They were taking up the fight themselves because they believed the state was too cowardly or too paralysed to defend itself against Judeo-communist usurpers: the liberal establishment was infiltrated, or naive, or merely weak, unable to contend with a communist agenda that sought to destroy white nativist values and identity. In this conspiracy, blacks often featured as unwitting pawns, but that did not spare them from being targeted. In 1979, nine vehicles carrying Klansmen and neo-Nazis – most of them veterans – drove to the site of a march in Greensboro, North Carolina, where members of the Communist Workers’ Party were protesting against the Klan’s attempt to sabotage their organising of black textile workers. Five of the protesters were killed in a shoot-out; 12 were wounded. The trial that followed resulted in acquittals for all of the accused, including the local police informants who had guided the assailants to the march.

Then, in 1980, Ronald Reagan arrived. Here was a president who quoted Rambo, referred to the Vietnam War as ‘the noble cause’ and told veterans that they had been ‘denied permission to win’. Reagan not only made it clear that he intended to open new fronts in the Cold War, he even appeared to some on the far right to be paying tribute to their tactics. In 1981 a motley group of a dozen mercenaries in Louisiana – Klansmen, neo-Nazis, arms smugglers – were caught by the FBI hatching a hare-brained scheme to topple the government of the Caribbean island of Dominica and restore a puppet dictator through whom they would launder funds to the KKK and prepare a staging ground to conquer Grenada. The press mocked their failure as ‘the Bayou of Pigs’ (the plan to collaborate with a splinter group of local Rastafarians to take down what was already a right-wing government strained credulity). But as Belew notes, the US invaded Grenada two years later and justified its coup with language remarkably similar to that of the Dominican plotters, who, like Reagan, referred to the island as a ‘Soviet-Cuban colony’.

The paramilitary right had a tense but ultimately productive relationship with Reagan. In 1979 the anti-communist Georgia congressman Larry McDonald established the Western Goals Foundation, a privately funded version of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which had been wound up four years earlier. Like HUAC, McDonald’s database stored files on thousands of Americans deemed ‘subversives’, especially those who – it was imagined – might be agitating on behalf of communist movements in Central America. The information the foundation gathered was shared with the FBI and other state agencies, along with the recommendation that the government outsource the work of counter-insurgency to the very same private security firms that were helping to fund the foundation. The increased privatisation of US state violence under the Reagan administration fitted neatly with the president’s more general anti-statist rhetoric.

Kyle Burke provides a guide to this dark underground territory of the Cold War. Just as the civil rights movement spanned the globe, so too did the reaction against it. In some regions it was the reaction that proved more enduring. Burke devotes space to the largely neglected World Anti-Communist League, founded in Taiwan in 1966. The league was remarkable for its fusion of Eastern and Western anti-communist funding and expertise. The US branch was organised by a gay ex-socialist from Brooklyn, Marvin Liebman, who had converted to anti-communism after reading Elinor Lipper’s Gulag memoir. Having recruited the US congressman Donald Judd and the Catholic priest Daniel Lyons, Liebman travelled to Taipei and helped draft the league’s agenda; at the league’s 1974 conference William F. Buckley gave the keynote address. And then there was John Singlaub, a retired general and another of the league’s main organisers, who thought the US government had fumbled the urban counter-insurgency against the Black Panthers and other radical groups, and that lessons should be learned from the admirable ruthlessness with which Latin American and East Asian authoritarians had crushed their leftist opponents.

In its early years the league stirred with impossible ambitions, such as winning back China for the Kuomintang. By the early 1970s, however, it had narrowed its focus. League affiliates in Chile and Argentina were considered to have helped score major successes – including Pinochet’s coup and the Dirty War. But as Burke shows, the league and its offshoots’ activities gradually became too radical for most of its American members: too many of those involved, such as the Ukrainian nationalist Yaroslav Stetsko, openly flaunted their fascist pedigrees, while groups such as Tecos in Mexico, which had once been recruited by the Nazis to fight on the US-Mexico border, waged an open campaign of terror against Castro-inspired rebels that included bombings, assassinations and kidnappings, all barely countered by the Mexican security forces.

One of the league’s main purposes was to serve as a headhunting and staffing agency for anti-communist operations. Liebman and Singlaub – whom Reagan commended for giving him ‘more material for my speeches than anybody else’ – became middlemen for right-wing networks that channelled millions of dollars from respectable sources (the beer magnate Joseph Coors was a major donor) to anti-communist causes and counter-insurgency operations around the world. Their largesse was spread wide. Liebman founded the Friends of Rhodesian Independence, which led tours for US government officials and professors, while Singlaub helped fund arms shipments to groups like the Contras in Nicaragua. Special interests sometimes clashed. In Angola, Chevron managed to forge an oil exploration agreement with the communist MPLA guerrillas, just as Singlaub and others – including a young consultant called Paul Manafort – successfully lobbied to get the Reagan administration to back their client, Jonas Savimbi. That the US government would hinder American companies from operating in South Africa, an anti-communist ally, but allow them to work with a communist regime in Angola outraged Singlaub and his colleagues. They soon called for a boycott of Chevron and encouraged Savimbi to attack the company’s Angolan properties.

In Rhodesia, the interests of American white power internationalism and American anti-communism dramatically converged. In 1965, Ian Smith’s white supremacist regime unilaterally declared Rhodesian independence from Britain, emboldened by support from across the US political establishment, from Dean Acheson to Bob Dole. When Reagan, as a presidential candidate, began flirting with the idea of backing white Rhodesians against Robert Mugabe’s growing insurgency, several hundred American mercenaries were already fighting there. Congressional attempts to establish the exact number – let alone stop them – made little progress. Not-so-covert action in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) continued even after Mugabe came to power in 1980. As late as 1999, three Americans from a right-wing church in Indiana were arrested at Harare airport while apparently engaged in a plot to assassinate Mugabe. (His paranoia wasn’t always unjustified.)

One lingering puzzle in the history of the paramilitary American right is why, in the early 1980s, a small but significant part of the movement began to rebel against the US state itself. During Reagan’s first term a few thousand members of the KKK and various ersatz militias started down a path that would eventually lead to serious clashes with federal authorities. In 1984, the white nationalist Robert Jay Mathews founded Brüder Schweigen, also known as The Order, a group that sought to bring down the US government. After robbing a series of banks to secure funds for the cause, Mathews was killed in a shoot-out with federal agents on Whidbey Island in Washington State, though his co-conspirators were acquitted of sedition by an all-white jury. Even if we grant Belew’s point that members of the American right had periodically risen up against the US government, Reagan’s election was in part an expression – and a vindication – of an explicitly anti-government creed. So why did elements of the paramilitary right turn against the government during his first term?

Part of the answer seems to be that Reagan was simply too little, too late. The most extreme wing of the radical right was already strongly critical of some of his appointments, especially of ‘internationalists’ such as George H.W. Bush, James Baker and Caspar Weinberger. Weinberger was one of the few figures in the administration to show concern about white extremism. Reagan only made matters worse by allying himself with Jewish neoconservatives, who his far-right critics believed controlled the ‘Zionist Occupation Government’. The spectre of the ZOG had emerged in mid-1970s American neo-Nazi literature, which updated the Protocols of the Elders of Zion for a new generation. It was a case of badly dashed expectations: Reagan was surrounding himself with neoconservatives who purported to share the paramilitaries’ anti-communist passion while secretly they were scheming to divert American power to their own cabalistic hyper-capitalism. By elevating the identity-erasing power of the purely rational marketplace they were really instituting a form of communism under a different name.

So from the vantage point of white power, the Reagan ‘revolution’ was anything but. ‘We spent fifty years trying to elect a conservative and what have we got?’ Robert Weems, a former KKK chaplain, asked at a rally of paramilitaries in 1984. The Reagan administration, Weems declared, doesn’t ‘take on the international bankers and the Federal Reserve; they think that’s part of our glorious capitalist heritage … They don’t take on the Zionists at all because they are the Chosen and our Number One ally in the Middle East … [and they won’t] take any stand for the white race and its preservation either.’ The extremism of Weems’s anti-capitalism marks the point where antisemitic white power and the wider anti-communist movement parted ways on questions of principle. But this should not lead us to dismiss the wide areas of common cause between white power fellow-travellers – whom Belew estimates at around 450,000 Americans – and today’s most prominent inheritors of the anti-communist tradition: free-market internationalists, or ‘globalists’, as their enemies call them. The current US president’s appeal to white nativists – the manna raining daily from Twitter – is in this sense hardly contradicted by the fact that he surrounds himself with veterans of Wall Street.

How, then, could white nationalism further its aims in the post-Vietnam era? One possible avenue was through the democratic system. In 1984, the racialist lobbyist Willis Carto founded the Populist Party, which bundled together ideas of racial purity, anti-Jewish conspiracy thinking and concerns about the money supply – in particular any kind of inflationary monetary policy that might benefit the wrong kind of poor people. The party appeared on ballot papers in 14 states, yet Carto’s efforts amounted to little more than a publicity vehicle for figures such as the Klansman David Duke and Green Beret vigilante Bo Gritz. In a bout of white power infighting, the neo-Nazi factions of the white power movement hounded Carto as a swindler of right-wing funds, and a ‘swarthy’ man of questionable racial make-up.

The second seriously considered option was what became known as the Northwest Territorial Imperative, the aim being to consolidate the white race in the already very white Pacific Northwest, where an ‘Aryan homeland’ would be established. The ‘imperative’ appears today merely like an extreme form of gerrymandering. After years of infighting and lost lawsuits, its latter-day incarnation is the Northwest Front, which operates an innocuous-looking website that displays real-estate advice for white patriots and sells the Front’s tricolour flags: ‘The sky is the blue, and the land is the green. The white is for the people in between.’2

There was, however, a third option for white power activists, originating with Louis Beam and William Pierce, a.k.a. Andrew Macdonald, the movement’s bard. Together they concocted the most influential and enduring of the white power projects. In Essays of a Klansman, published in 1983, Beam advocated an all-out race war. The civil rights battles, he argued, had already been lost. But the best response was not to make a bid for a return to segregation: that was far too moderate an ambition. What was called for instead was white national liberation of the entire US mainland. The real culprit was ‘communist-inspired racial mixing’ and the real enemies were the ‘white racial traitors’ who had allowed it to happen. Beam wanted to redirect the energies of white power against those elements of the federal government which he believed had betrayed its original constitutional mandate to protect the white race.

Beam’s most inspired innovation was his blueprint for ‘leaderless resistance’, a model of guerrilla warfare, borrowed from communist and anti-colonial partisans, in which small cells operate in concert but without knowing the leaders of the other cells, removing any chance of their informing on one another. The move away from bands of local vigilante groups to anonymous, spread-out terror cells marked a major shift in the white power movement – reflecting an understanding that it was no longer operating merely in local contexts. Beam himself, Belew stresses, was an early and ardent adopter of the internet, making use of codeword-accessible message boards, pen pal programs and online advertising to spread the word of white power.

If Beam was known as the ‘general’ of the white power movement, Pierce – who had taught physics at Oregon State – was the ‘strategist’. In 1978 he published The Turner Diaries, a novel that went on to sell half a million copies. The book purports to be the diary of a bygone racist revolutionary who helped to overthrow the US government; the civil war begins when Congress passes the ‘Cohen Act’, banning the use of all firearms. But a small patriotic ‘organisation’ eventually prevails against this tyranny. Blacks in the South are bombed into oblivion with nuclear weapons, the Jews experience another Holocaust and women become a servant class. The US dollar is abolished, the calendar is set back to zero and the federal government goes down in flames when a biplane with a sixty-kiloton warhead flies into the Pentagon.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 presented more favourable conditions for Beam and Pierce’s fantasies to be put into action. Their views were now echoed in mainstream culture. Pat Robertson’s bestselling The New World Order (1991) claimed to unveil a vast Jewish-capitalist conspiracy, while Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein’s pseudoscience blockbuster, The Bell Curve (1994), laboured to justify America’s racial hierarchy. In 1989, Beam had already put the question to his brethren: ‘Now that the threat of communist takeover in the United States is non-existent, who will be the enemy we all agree to hate?’ Highly publicised stand-offs in the 1990s seemed to confirm that his faction had been right to double down on the federal government as their enemy.3 At Ruby Ridge, Idaho in 1992, the Vietnam veteran Randy Weaver and his family exchanged fire with federal forces; Weaver’s wife and son were killed in paradigmatic displays of white martyrdom. During the Waco siege of 1993, federal agents stormed the compound of the Branch Davidian religious sect and 76 people were killed. Despite the sect’s lack of connection to the white power movement, the siege became a rallying cause for paramilitary groups that feared state overreach.

One television viewer galvanised by the Waco raid was Timothy McVeigh, then 24 years old. A Gulf War veteran who had seen sustained combat and been exposed in training to the same cyanocarbon tear gas used by ATF agents at Waco, McVeigh was an ideal candidate for Beam’s ‘leaderless resistance’. In 1995, after he bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City – until 9/11 the deadliest terrorist attack in US history – he was tried as a ‘lone wolf’ killer, despite his connections with wider paramilitary networks, such as the Michigan Militia and the ‘Viper’ militia of Arizona, and his stash of white power literature (he was a steady consumer of right-wing ‘zines’). In his case, the tactics of leaderless resistance paid off. Instead of hunting down the co-conspirators and publicising the networks, information and material that McVeigh had relied on, the media in general presented him as an isolated psychopath.

But McVeigh should interest us perhaps more for the person he became in prison. By the time of his execution, in 2001, he had begun to sound like a contributor to Counterpunch. Here he was, cogently, in 1998:

If Saddam is such a demon, and people are calling for war crimes charges and trials against him and his nation, why do we not hear the same cry for blood directed at those responsible for even greater amounts of ‘mass destruction’ – like those responsible and involved in dropping bombs on [Iraqi] cities. The truth is, the US has set the standard when it comes to the stockpiling and use of weapons of mass destruction.

The connections between American violence abroad and American violence at home seemed self-evident to McVeigh, but for the majority of Americans even to hint at such connections remains taboo.

Donald Trump has been the most significant beneficiary of the hypocrisy of American foreign policy as described by McVeigh. Before the last presidential election, no other candidate, Bernie Sanders included, was so savage in his reckoning of America’s recent foreign ventures. ‘A complete waste,’ he called the country’s longest war. ‘Our troops are being killed by the Afghanis we train and we waste billions there.’ Nor has any other president in recent memory capitalised more on the humiliation of those who fight in, or traditionally support, America’s wars. Winning for the president pertains to more than trade. Whatever the ultimate fortunes of the combined forces of American reaction, the ‘leaderless resistance’ is likely to continue. It has rarely been clearer that those who cheer on American interventions abroad should be prepared for more ferocious nativist terror at home.

#if you don't know all the people places and things mentioned here#then you've got a lot of reading to do

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Increasingly determined and bold separatists seeking the international recognition of the self-proclaimed “Federal Republic of Ambazonia” (Southern Cameroons) have created a crypto-currency which they claim is the first to be fully nation-backed. Known as AmbaCoin, 20,082 of the Ambazonian crypto bond had already been bought, out of 100,000,000 on pre-sale as of Nov. 10. One AmbaCoin sells for 25 cents (circa 140 CFA franc) and the main initial coin offering of the crypto-currency is scheduled for Dec. 24. It is said to be backed by the “rich natural resources” of the breakaway region. The AmbaCoin was conceived and built by a group of anonymous Anglophone separatist scholars, technocrats and developers. But it has gained the support of frontline secessionists and separatist movements. When news of the crypto-currency was made public last month, Chris Anu, who has the title secretary of state for communications & IT for the “Federal Republic of Ambazonia”, posted a sample of the crypto-currency bond on his Facebook page and said: “We are getting there folks.” In the last five decades in Africa, especially in areas where people want to create a country of their own out of another, people have been opting to put their faith in a form of exchange other than a currency which is globally accepted. During the Nigerian civil war (1966-1970), the then self-declared Republic of Biafra adopted the Biafran pound as legal tender, abandoning the Nigerian pound it had been using before ‘independence’. There is also a plethora of unrecognized countries in the past which came up with currencies in their efforts to be independent. The Katangas in DR Congo came up with their own franc currency in the 1960s, while the Rhodesian pound was the currency of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1970. https://www.instagram.com/p/BrXwW1jnP3l/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=aneu917tndht

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

So why the fascination with Vikings? Like I am fascinated with all Warrior Classes. Just curious

Well for starters they aren’t my only interest. I also enjoy high middle ages knights and men at arms, the pike and shot era, American Civil War, Rhodesian Bush War shenanigans, and about a dozen other things.

Vikings are probably my biggest and most consistent historical interest though and to be honest I’m not sure why they specifically grabbed my interest. I just like them; cool axes, cool boats, cool armor, cool mythology. I also really enjoy the mystery they present, they were a huge driving force for the early middle ages and we have barely any actual artifacts of theirs and all the written history about them was either done by the cultures they were actively raiding (heavily biased) or by Icelanders several centuries after the end of the Viking period.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

JACOBIN MAGAZINE

In the late 1970s, about four hundred white American men, mostly Vietnam veterans, traveled to Rhodesia and Angola to fight as mercenaries. Convinced that the US government was too weak to counter the spread of communism in southern Africa, they took matters into their own hands. By picking up arms, these men hoped to continue their wartime crusade against America’s enemies abroad while reclaiming the economic and social power they believed they had lost to African Americans, women, and other groups at home.

The rise of the Right is usually told as a domestic tale. But the story of US mercenaries in Africa shows that right-wing Americans were also part of a larger international anticommunist mobilization that spanned the Cold War era. Drawing upon arguments pressed by US conservative leaders, they enacted a shadow foreign policy that linked overseas conflicts to domestic struggles, leaving legacies that resonate today.

Although most US mercenaries had a marginal impact on the wars in Rhodesia and Angola, the circulation of violence — both real and imagined — between the United States and southern Africa helped radicalize domestic paramilitary groups in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And the ideas and impulses that animated these American mercenaries helped generate new forms of privatized warfare.

“We Can’t Afford to Lose Any Other Countries”

The Americans who took up arms in Africa in the 1970s looked out on the world and saw the Soviet Union and its allies on the march, making great strides towards world domination. In the former Portuguese colony of Angola, which gained independence in 1975, the Cuban- and Soviet-supported Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) had seized power from rival nationalist guerrillas, igniting civil war. In Rhodesia, a white-supremacist state that broke from the British Empire in 1965, two guerrilla armies, supported by the Soviet Union and China, were pushing the government to the brink of collapse.

Rhodesia’s war was especially concerning. Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith famously called his country the “ultimate bastion against communism on the African continent,” and many leading US conservatives agreed. William F. Buckley had even helped organize a propaganda campaign known as the Friends of Rhodesian Independence, which worked hand in hand with the Rhodesian government to popularize Rhodesia’s cause in the United States. But nothing seemed to work. The growing war — coupled with US, British, and UN sanctions — imperiled Rhodesia’s future. If it fell, then communists would take over, as in Angola.

That alone troubled right-wing Americans. But perhaps even more disconcerting was the response of the US government, especially the CIA, which had been hamstrung by a series of scandals and investigations that rocked the intelligence community in the mid-1970s. The state appeared both unable and unwilling to reverse the spread of communism in Africa. When the CIA had mounted a covert action against Angola’s Marxists in late 1975, Democrats in Congress shut it down within a few months. “The West isn’t doing its job,” one American mercenary lamented. “The US especially isn’t doing its duty. If they’re too scared to fight the Communists, then people like me have to act independently. I consider it my duty to fight in Rhodesia. After Vietnam and Angola, we can’t afford to lose any other countries.”